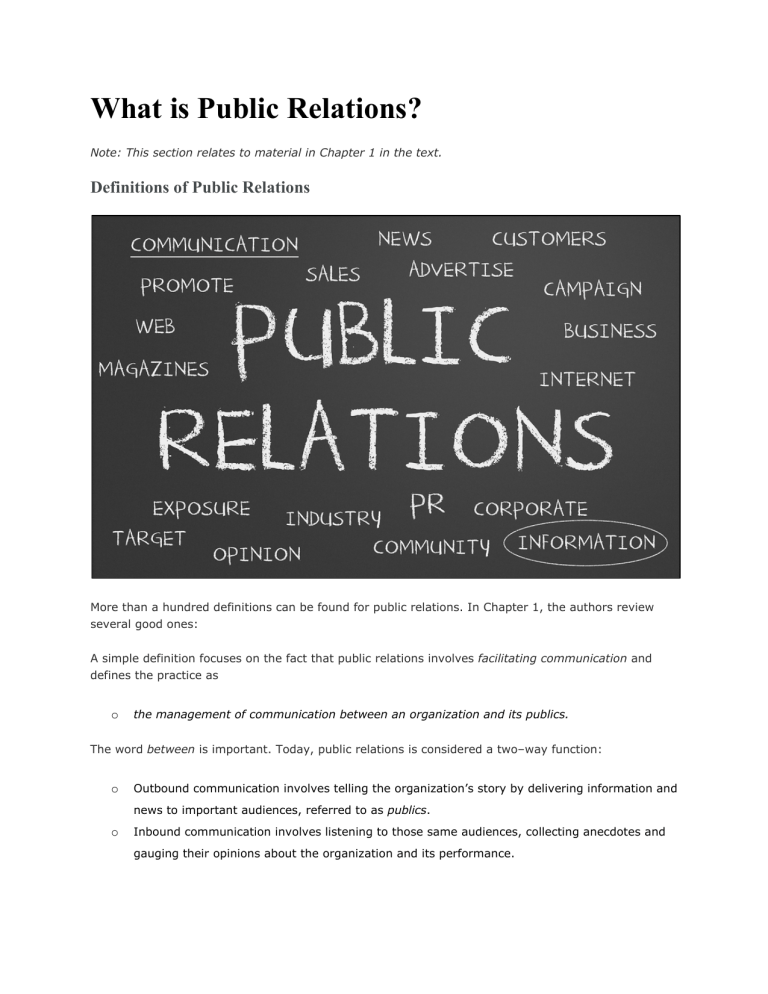

What is Public Relations? Note: This section relates to material in Chapter 1 in the text. Definitions of Public Relations More than a hundred definitions can be found for public relations. In Chapter 1, the authors review several good ones: A simple definition focuses on the fact that public relations involves facilitating communication and defines the practice as o the management of communication between an organization and its publics. The word between is important. Today, public relations is considered a two–way function: o Outbound communication involves telling the organization’s story by delivering information and news to important audiences, referred to as publics. o Inbound communication involves listening to those same audiences, collecting anecdotes and gauging their opinions about the organization and its performance. This is a modern approach to public relations and lays the foundation for two more advanced definitions found in the book: Long and Hazelton define public relations as: o a communication function of management through which organizations adapt to, alter or maintain their environment [for] achieving organizational goals. Cutlip, Center and Broom provide a four-part definition that suggests public relations is: o a management function o that identifies, establishes and maintains mutually beneficial relationships o between an organization o and the publics upon whom its success or failure depends. These definitions suggest that public relations serves an important function in most organizations. Yet these definitions can be somewhat abstract. Different organizations might define public relations in different ways. As you read Chapter 1 and the first several chapters of the book, consider different ways you might define public relations. Components of Public Relations Ideas represented in this wordcloud comprise the lexicon of public relations today. One reason public relations is difficult to define is that the field often subsumes a large number of activities. These are outlined in the text. Activities commonly associated with public relations include: o Media relations o Publicity o Community Relations o Government relations/lobbying o Investor relations o Development/fundraising o Special events management o Promotions o Marketing communication In addition, public relations people: o often advise clients on policies and practices that will make it possible to establish or maintain good relationships with key constituencies, and o conduct research to support their counseling activities and to help organizations develop a better understanding about people and their opinions. Public Relations Versus Other Functions A useful way to better understand public relations is to know what public relations is not. Indeed, public relations can be differentiated from several other functions commonly found in organizations. Public relations also differs from journalism, although it draws heavily upon journalistic skills to create communications directed to key audiences. These differences are examined in the second half of Chapter 1. Public relations is not marketing. Public relations is often confused with the marketing function because public relations people frequently help to promote an organization, its products, services or cause. Going back to the definition of public relations as the management of communication, public relations can be thought of as a narrower field of endeavor that focuses on the exchange of information and news between an organization and key publics. Marketers are involved in an array of activities that extend far beyond public relations. They often describe their function as the identification and fulfillment of customer wants and needs, usually for products or services. Marketing thus involves 4Ps: product, price, place and promotion. o Product includes activities related to the development and design of products, including their packaging. o Pricing involves determining how much to charge, including the possible use of discounts. o Place involves deciding where to make a product available, such as retail stores versus the web, and all the logistics involved in distributing the product, including warehousing and the management of retail outlets. o Promotion involves creating incentives and enticing a potential customer to purchase a product. Here, marketers often think about public relations and publicity as part of the promotion mix. Public relations is not sales. Public relations is sometimes confused with the sales function in organizations. Sales involves the person-to-person presentation of a product or service to a customer. Sales people often have sales goals, and sometimes are compensated based on the quantity of sales they handle. Sales people also are involved in negotiating terms of a sale, or in collecting funds from customers for services rendered. Public relations people, as facilitators of communication, handle none of these duties. The confusion between public relations and sales is evident because many sales people are told their duties include "public relations," or establishing and maintaining personal relationships with customers. They are encouraged to ingratiate themselves with customers, so that they personally (and the organization) will be liked. However, individual sales people do not have organization–wide duties; their communications activities are usually limited to one–on–one communications, such as personal meetings, telephone calls or correspondence with particular customers. Public relations is not advertising. Although the two functions are often considered similar, advertising involves the purchase of space (in print media) or time (in broadcast media) to promote products and services. Advertising, as an industry, operates separately from public relations and generally earns its income from commissions paid by media outlets, rather than merely fees paid by clients to produce messages. Advertising agencies specialize in producing paid messages, such as TV commercials, to promote products and services; public relations can be used to promote products but relies on free or "earned" media exposure, such as features on TV news and entertainment shows and newspaper and magazine feature stories. Advertising can be a tool used in many public relations campaigns, particularly when it's important to control the timing and content of messages. However, public relations techniques often focus on approaches other than advertising that often cost significantly less. People are often skeptical about the motives behind advertising, but generally less resistant to public relations messages. Public relations is not publicity. One of the most commonly used tools in public relations is publicity. For purposes of this course, we’ll define publicity as the dissemination of news and information about an organization, usually through mass media (newspapers, magazines, radio or television). Sales people, for example, do not have as one of their primary responsibilities gaining media visibility for an organization. The confusion between public relations and publicity is not surprising. After all, public relations evolved out of the need of organizations to use the news media to communicate with key audiences. However, modern public relations is much more than publicity. For example, public relations activities might be carried out without using the press. Examples include using the internet, printed publications, group events and one–on–one communications. While many clients look to public relations to optimize exposure in the press, public relations involves far more than publicity. Public relations is not journalism. Finally, it might be useful to differentiate between a public relations practitioner and a journalist. PR people who are responsible for publicity and media relations often employ journalistic skills, such as the ability to write an interesting, hard–hitting news story, to tell their client’s story. Yet public relations practitioners and journalists have different responsibilities. Although they often employ journalistic skills, public relations representatives typically serve as advocates for clients, whereas as journalists seek out information they believe their audiences need or want to know. A public relations practitioner serves as a representative for a particular organization, product or service, candidate or cause. As such, the practitioner’s allegiance is to the client. The practitioner's job is to articulate an organization's story forcefully and clearly. In this sense, PR people are advocates who use journalistic skills. By contrast, a journalist is a communicator who works for a third–party organization that is in the business of providing news and information that people want and need. Journalists serve as an important function in society by sifting through available information, summarizing it, and then reporting it to their audiences. In screening information, journalists serve as gatekeepers, who make judgments about the relevance and veracity of all of the information available. In turn, their audiences expect journalists to supply information that is informative, balanced and objective (provides alternative perspectives as a matter of fairness). As a result, PR practitioners and journalists are sometimes at odds. Why Public Relations? Note: This section provides an overview for Chapter 2 in the text. Consider this: In a perfect world, there would be no need for public relations. People would be fully informed about what was happening in society. All public policy decisions would be made for us to everyone's satisfaction. All our human wants and needs would be met. There would no conflicts. Unfortunately, we don't live in a utopian world. This makes the need for public relations essential. As Chapter 2 details, modern public relations is mostly a creation of the 20th century. Although its antecedents can be traced to ancient times, the ideas of publicity and public relations, as we know them, evolved in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Three broad trends contributed to PR’s evolution. Increased Complexity of Society A variety of factors converged in the 1800s that made society more complex than in previous times. Many people converged on cities in the 1880s and 1890s in search of employment and a better life. Classical sociologists refer to this shift as one from community to society. This was a period in which societies in Western Europe and America changed from being primarily agricultural to industrial. People moved from the country to the cities. Immigration contributed to this urbanization, which was made possible by the creation of jobs by large industrial organizations. What were the consequences of all these changes? Many people felt disconnected, or lacked a sense of community. The psychological effect was anomie, or a sense of alienation. Bringing together so many diverse peoples—with different values and beliefs—created the potential for differences of opinion. The period was a classic test of American democratic pluralism, or the notion that people with differing viewpoints should be able to co–exist and that we should maintain respect for people holding different opinions or values. Rise of Large Organizations, Mass Media and Big Government Along with the increased complexity of society came the rise of large industrial concerns. Companies devoted to manufacturing and transportation became important economic forces. In their earliest years, these concerns were able to produce and market products however they wanted. In 1882, railroad baron William Vanderbilt summarized the attitude of business with his now famous quote, "The public be damned." However, the public soon became alarmed about actual and potential abuses. Companies learned that they had to be more sensitive to public sentiment in order to be successful. One of the most important changes that occurred was the rise of large–scale newspapers and magazines. In the United States, for example, during the 1890s, newspapers and magazines became increasingly influential with their audiences. This was the period of “yellow” (sensationalized) journalism, which was quickly followed by the “Muckraking” period, where major magazine writers started to challenge the practices of Big Business. A sympathetic government responded by passing various laws to reform business abuses during the Progressive Era. For–profit businesses recognized that they had to do a better job to communicate with the public. At the same time, not–for–profit organizations started to realize that they could use the media to help advance their causes. The mass media had become a force to be reckoned with. Interdependency A final factor that led to the rise of modern public relations was the interdependency of people on organizations, and the need for information. People became increasingly dependent on news and information from others, some of which they obtained through new media, such as radio. PR people helped supply information people needed. As organizations became more complex, it became incumbent upon them to supply information to employees as well as people who used their products or services. Moreover, it became a necessity as people started to ask them for timely and accurate information. Following the Stock Market Crash of 1929, new laws made it a requirement for public companies to furnish accurate and timely information to stockholders. The demand for information led organizations to appoint staff members whose responsibilities were to interface with people both outside and inside the organization. Information became an important commodity that would facilitate the management of the organization, and improve its effectiveness and efficiency. People Historical Highlights Note: This section relates to material in Chapter 2 in the text. Chapter 2 examines the development of public relations through the years. Read the text to gain an understanding of how public relations evolved in the context of major events taking place in society. Don't try to memorize every name, date or accomplishment. Focus on developments that might be of special interest to you. To understand the milestone contributions of practitioners of the PR practice, it’s valuable to focus on three key people of the 20th century—even though many other people helped shape modern public relations. Ivy Lee: A Focus on Truth and Service Many people consider the "father of modern public relations" to be a former newspaperman with the unusual name of Ivy Ledbetter Lee. Lee worked from about 1904 to 1934 for a wide range of notable clients, including the wealthy Rockefeller family. Ivy Lee Lee was notable as the first PR counsel to stress the importance of truth and openness when business organizations dealt with the press. Prior to Lee, much publicity work involved puffery or hype with little regard to accuracy. Many publicists would say anything to get their client's name in the newspaper. Similarly, organizations were notorious for not cooperating with the press. They were frequently not available or simply refused to answer questions. Lee advised clients that in order to deal effectively with the press, it was necessary to help reporters get stories and to make sure that information was factual or verifiable. His philosophy, which provided the foundation for modern practice, was contained in his Declaration of Principles, which was distributed widely to the press in 1906. In part, it reads: This is not a secret press bureau. All our work is done in the open. We aim to supply news. This is not an advertising agency; if you think our matter ought properly to go to your business office [advertising department], please do not use it. Our matter is accurate. Further details on any subject treated will be supplied promptly, and any editor will be assisted most cheerfully in verifying directly any statement of fact. … Lee represented a markedly different approach from the way most publicists of his day worked. The text reviews Lee's accomplishments and his legacy. Edward L. Bernays: Applying Social Science Concepts Lee began his career before World War I, and never used the term "public relations" until much later in his career. At the end of war, a second major figure emerged in the field as a counselor to major organizations: Edward L. Bernays. Bernays was the first practitioner to describe himself as a "public relations counselor" and wrote one of the first books on the field, Crystallizing Public Opinion in 1923. Note: Various books on modern publicity were written at the same time. Bernays was also the first person to teach a course in public relations, offered at New York University. Edward L. Bernays After working as a theatrical press agent before the war, and later on the staff of the Office of War Information during World War I, Bernays began a counseling firm that was heavily involved in product promotion in the early 1920s. His client roster came to match Lee's in terms of the prominence of clients served. Among the clients he served were the American Tobacco Company and the General Electric Company. For American Tobacco, he helped popularize the Lucky Strike brand and made it more socially acceptable for women to smoke in public. Although the encouragement of smoking might be considered questionable today, Bernays' work in 1927 for American Tobacco led to a major change in public attitudes. Two years later, he orchestrated for General Electric a worldwide celebration for the 50th anniversary of the invention of the electric light bulb, the "Golden Jubilee of Light." Although his client was hardly even mentioned, GE benefited from the effort to recognize the contribution of Thomas Alva Edison (who was still alive) and the contributions that the light bulb made to progress. Using a worldwide radio broadcast, the Jubilee included the simultaneous switching on of lights by people around the world. Bernay's major contribution to public relations was his focus on understanding and modifying human behavior through the application of social science. Bernays had an advantage because he was the nephew of Sigmund Freud. Bernays applied many of his uncle’s ideas involving psychoanalysis to human behavior. Easter Parade In the case of women smoking cigarettes, for example, Bernays embraced and promoted the psychoanalytic argument that cigarettes represented "torches of freedom" for repressed women. In 1927, he convinced a group of New York debutants and their escorts to walk down Fifth Avenue in the Easter Parade while smoking cigarettes. Their women's action caused a sensation and was widely covered in the newspapers. Within six weeks, New York theaters opened their smoking lounges to women. Bernays argued that public relations was an applied social science and that successful PR involved understanding psychology, sociology and anthropology. See the text for additional details on Bernays and his wife and professional partner, Doris Fleischman. Arthur W. Page: Integrating Public Relations into Corporate Management Arthur W. Page The third important figure in the early development of PR was the first vice president of public relations at American Telephone and Telegraph Company. The company had historically demonstrated enlightened views about dealing with the public. This focus was necessitated by the fact that ATT was an amalgamation of local, independently owned telephone companies that were brought together beginning at the turn of the 19th century. Every acquisition involved carefully addressing local concerns about the loss of control over the local telephone system. In 1927, Arthur W. Page was editor of Working World and a principal in the magazine's New York– based publishing company, Doubleday & Page. When Page was asked to join ATT, he said he would only do so on his terms. He insisted that he have a role in formulating corporate policy and that public relations serve in a major advisory capacity, not merely perform publicity activities. For the next two decades, Page was a trend–setter in the field. He was one of the first to recognize the importance of good internal communications. By informing employees about what the company was doing, Page thought that employees could do a better job in representing the firm. He also was one of the first corporate executives to embrace the new technique of survey research, which was made possible through the discovery of statistical sampling theory. Surveys allowed ATT and other organizations to measure public opinion quantitatively. Page was also an early advocate of corporate social responsibility. Page's enlightened views are well summarized in this now–famous statement about the responsibility of business. It serves as a useful credo for any organization today: All business in a democratic society begins with public permission and exists by public approval. If that be true, it follows that business be cheerfully willing to tell the public what its policies are, what it is doing, and what it hopes to do. This seems practically a duty. Major Trends Important to Public Relations Note: This section relates to material in Chapter 2 in the text. Chapter 2 concludes by outlining a dozen trends in contemporary society that have important consequences for organizations and that are also shaping the need for public relations in the 21st century. These trends are not materially different from what was happening a hundred years ago when public relations emerged as a professional discipline and as a set of activities in society. The complex society in which we live continues to influence public relations through the increased attention being devoted to issues management, and the proliferation of publics with different priorities. The potential for conflict is readily seen in protests about foreign political involvements and environmental concerns. The rise of the mass media has been succeeded by the advent of even more challenging forms of communication, including satellite broadcasting and the Internet. These new technologies have collapsed our notions of time and space. Organizations today must be able to communicate rapidly, in real time, and not merely produce a news release for tomorrow morning's newspaper. The interdependence between people and organizations is evident in the globalization of the economy and of media relations. The rise of the multinational organization has created new challenges for how organization managers relate to ever–divergent populations around the world. These trends make public relations a challenging—and rewarding—field for everyone involved in the practice.