Sustainable Packaging Design & Consumer Purchase Intention Thesis

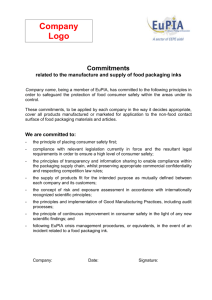

advertisement