Lithuania CPT Report: Torture Prevention & Detention Conditions

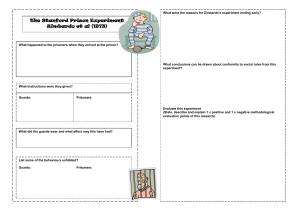

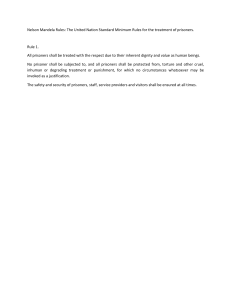

advertisement