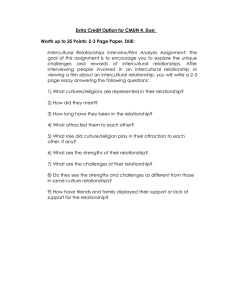

CRITICAL INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF CONTEXT I

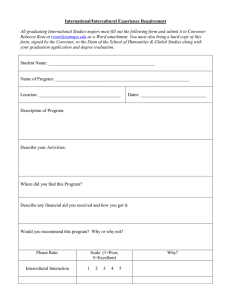

advertisement