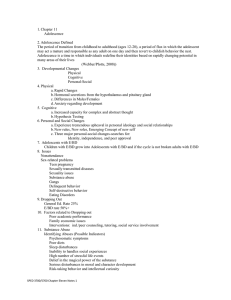

Social and Emotional Development in Adolescence Diana Lang; Nick Cone; Alisa Beyer; Julie Lazzara; Martha Lally; Suzanne Valentine-French; and OpenStax College Caregivers and Teens: Autonomy and Attachment One of the key changes during adolescence involves a renegotiation of parent-child relationships. As adolescents strive for more independence and autonomy during this time, different aspects of parenting become more common. For example, parents’ distal supervision and monitoring become more important as adolescents spend more time away from parents and in the presence of peers. Parental monitoring encompasses a wide range of behaviors such as parents’ attempts to set rules and know their adolescents’ friends, activities, and whereabouts, in addition to adolescents’ willingness to disclose information to their parents.[1] Interestingly, the association between the CHRM2genotype and adolescent externalizing behavior (aggression and delinquency) has been found in adolescents whose caregivers engage in low monitoring behaviors.[2] While most adolescents tend to get along with their parents or primary caregivers, many tend to spend less time with them.[3] This decrease in the time spent with families may be a reflection of a teenager’s greater desire for independence or autonomy. It can be difficult for many parents to deal with this desire for autonomy. However, it is likely adaptive for teenagers to increasingly distance themselves and establish relationships outside of their families in preparation for adulthood. This means that both parents and teenagers need to strike a balance between autonomy, while still maintaining close and supportive familial relationships. Children in middle and late childhood are increasingly granted greater freedom regarding moment-to-moment decision making. This continues in adolescence, as teens are demanding greater control in decisions that affect their daily lives. This can increase conflict between parents and their teenagers. For many adolescents, this conflict centers on chores, homework, curfew, dating, and personal appearance. These are all things many teens believe they should manage that parents previously had considerable control over. Not surprisingly, culture and ethnicity can play a role in how restrictive parents/caregivers are with the daily lives of their children. [4] Research shows that teens whose caregivers use effective monitoring practices are less likely to make poor decisions, such as engaging in sexual intercourse at an early age, smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, being physically aggressive, or skipping school.[5][6][7][8][9] Clear communication about expectations is especially important. Research shows that teens who believe their parents/caregivers disapprove of risky behaviors are less likely to choose those behaviors[10] Having supportive, less conflict-ridden relationships with primary caregivers also benefits teenagers. Research on attachment in adolescence find that teens who are still securely attached to their parents/caregivers have less emotional problems,[11] are less likely to engage in drug abuse and other criminal behaviors,[12] and have more positive peer relationships.[13] Peers Peer relationships are a big part of adolescent development. The influence of peers can be both positive and negative as adolescents’ experiment together with identity formation and new experiences. As children become adolescents, they usually begin spending more time with their peers and less time with their families, and these peer interactions are typically increasingly unsupervised by adults. Children’s notions of friendship often focus on shared activities, whereas adolescents’ notions of friendship increasingly focus on intimate exchanges of thoughts and feelings. Adolescents within a peer group tend to be similar to one another in behavior and attitudes, which has been explained as being a function of homophily (adolescents who are similar to one another choose to spend time together in a “birds of a feather flock together” way) and influence (adolescents who spend time together shape each others’ behavior and attitudes). One of the most widely studied aspects of adolescent peer influence is known as deviant peer contagion,[14] which is the process by which peers reinforce problem behavior by laughing or showing other signs of approval that then increase the likelihood of future problem behavior. Peers can serve both positive and negative functions during adolescence. Negative peer pressure can lead adolescents to make riskier decisions or engage in more problematic behavior than they would alone or in the presence of their family. For example, adolescents are much more likely to drink alcohol, use drugs, and commit crimes when they are with their friends than when they are alone or with their family. However, peers also serve as an important source of social support and companionship during adolescence, and adolescents with positive peer relationships are happier and better adjusted than those who are socially isolated or have conflictual peer relationships. Crowds are an emerging level of peer relationships in adolescence. In contrast to friendships (which are reciprocal dyadic relationships) and cliques (which refer to groups of individuals who interact frequently), crowds are characterized more by shared reputations or images than actual interactions.[15] These crowds reflect different prototypic identities (such as jocks or brains) and are often linked with adolescents’ social status and peers’ perceptions of their values or behaviors. Romantic Relationships Adolescence is the developmental period during which romantic relationships typically first emerge. Although romantic relationships during adolescence are often short-lived rather than long-term committed partnerships, their importance should not be minimized. Many adolescents spend a great deal of time focused on romantic relationships, and their positive and negative emotions are more tied to romantic relationships (or lack thereof) than to friendships, family relationships, or school.[16] Romantic relationships contribute to adolescents’ identity formation, changes in family and peer relationships, and adolescents’ emotional and behavioral adjustment. Furthermore, romantic relationships are centrally connected to adolescents’ emerging sexuality. Parents, policymakers, and researchers have devoted a great deal of attention to adolescents’ sexuality, in large part because of concerns related to sexual intercourse, contraception, and preventing teen pregnancies. However, sexuality involves more than this narrow focus. For example, adolescence is often when individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, etc., come to perceive themselves as such.[17] Thus, romantic relationships are a domain in which adolescents’ experiment with new behaviors and identities. Social and Emotional Changes in Adolescence Self-concept and Self-esteem In adolescence, teens continue to develop their self-concept. Their ability to think of the possibilities and to reason more abstractly may explain the further differentiation of the self during adolescence. However, the teen’s understanding of self is often full of contradictions. Young teens may see themselves as outgoing but also withdrawn, happy yet often moody, and both smart and completely clueless (Harter, 2012). These contradictions, along with the teen’s growing recognition that their personality and behavior seems to change depending on who they are with or where they are, can lead the young teen to feel like a fraud. With their parents they may seem angrier and sullen, with their friends they are more outgoing and goofier, and at work they are quiet and cautious. “Which one is really me?” may be the refrain of the young teenager. Harter[18] found that adolescents emphasize traits such as being friendly and considerate more than do children, highlighting their increasing concern about how others may see them Harter also found that older teens add values and moral standards to their self-descriptions. As self-concept differentiates, so too does self-esteem. In addition to the academic, social, appearance, and physical/athletic dimensions of selfesteem in middle and late childhood, teens also add perceptions of their competency in romantic relationships, on the job, and in close friendships.[19] Self-esteem often drops when children transition from one school setting to another, such as shifting from elementary to middle school, or junior high to high school.[20] These drops are usually temporary unless there are additional stressors such as parental conflict, or other family disruptions.[21] Self-esteem tends to increase from mid to late adolescence for most teenagers, especially if they feel competent in their peer relationships, their appearance, athletic, and other abilities.[22] Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory: Identity vs. Role Confusion Erikson believed that the primary psychosocial task of adolescence was establishing an identity. Many teens may struggle with the question, “Who am I?” This includes questions regarding their appearance, vocational choices and career aspirations, education, relationships, sexuality, political and social views, personality, and interests. Erikson saw this as a period of confusion and experimentation regarding identity and one’s life path. During adolescence, we tend to experience psychological moratorium, where teens put on hold commitment to an identity while exploring options. The culmination of this exploration is a more coherent view of oneself. Those who are unsuccessful at resolving this stage may either withdraw further into social isolation or become lost in the crowd. However, more recent research suggests that few leave this age period with identity achievement, and that most identity formation occurs during young adulthood.[23] Identity formation also occurs as adolescents explore and commit to different roles and ideological positions. Nationality, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religious background, sexual orientation, and genetic factors shape how adolescents behave and how others respond to them and are sources of diversity in adolescence. Despite these generalizations, factors such as country of residence, gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation shape development in ways that lead to a diversity of experiences across adolescence. During high school and the college years, teens and young adults move from identity diffusion and foreclosure toward the biggest gains in the development of identity are after high school. Those who attend college tend to be exposed to a greater variety of career choices, lifestyles, and beliefs. This is likely to spur on questions regarding identity. A great deal of the identity work we do in adolescence and young adulthood is about values and goals, as we strive to articulate a personal vision or dream for what we hope to accomplish in the future.[24] Gender identity A person’s sex, as determined by one’s biology, does not always correspond with one’s gender. Sex refers to the biological differences such as genitalia and genetic differences. Gender refers to the socially constructed characteristics of people, such as norms, roles, and relationships. Many adolescents use their analytic, hypothetical thinking to question traditional gender roles and expression. If their genetically assigned sex does not line up with their gender identity, they may refer to themselves as transgender, non-binary, or gender-nonconforming. Gender identity refers to a person’s self-perception as male, female, both, genderqueer, or neither (Figure 1). Cisgender is an umbrella term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex, while transgender is a term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity does not correspond with their birth sex. Gender expression, or how one demonstrates gender (based on traditional gender role norms related to clothing, behavior, and interactions) can be feminine, masculine, androgynous, or somewhere along a spectrum. Fluidity and uncertainty regarding sex and gender tend to appear during early adolescence, when hormones increase and fluctuate creating difficulty of selfacceptance and identity achievement.[25] Gender identity, like vocational identity, is becoming an increasingly prolonged task as attitudes and norms regarding gender keep changing. The roles appropriate for people are evolving and some adolescents may foreclose on a gender identity as a way of dealing with this uncertainty by adopting more stereotypic roles.[26] The next section, emerging adulthood, will outline additional information about identity development and intimacy. Aggression and Antisocial Behavior Bullying According to the CDC,[27] bullying is any unwanted, repeated aggressive behavior(s) by another person or group (who are not siblings or dating partners) that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance. A person can be a perpetrator, a victim, or both (also known as “bully/victim”). Bullying can elicit physical, psychological, social, and educational harm on the victim.[28] Common types of bullying include: Physical (hitting, kicking, tripping, etc.), Verbal (name-calling, teasing, etc.), Relational/social (spreading rumors, failing to include, etc.), Damage to the victim’s property, and Electronic bullying or cyberbullying. Anxiety and Depression Developmental models of anxiety and depression also treat adolescence as an important period, especially in terms of the emergence of gender differences in prevalence rates that persist through adulthood.[29] Although the rates vary across specific anxiety and depression diagnoses, rates for some disorders are markedly higher in adolescence than in childhood or adulthood. Anxiety and depression are particularly concerning because suicide is one of the leading causes of death during adolescence. Family adversity, such as abuse and parental psychopathology, during childhood, can set the stage for social and behavioral problems during adolescence. Adolescents with such problems tend to generate stress in their relationships (e.g., by resolving conflict poorly and excessively seeking reassurance) and select more maladaptive social contexts (e.g., “misery loves company” scenarios in which depressed youths select other depressed youths as friends and then frequently co-ruminate as they discuss their problems, exacerbating negative affect and stress). Adolescents who have more relationship-oriented goals related to intimacy and social approval are more vulnerable to disruption in these relationships. Anxiety and depression can then exacerbate problems in social relationships, which can also contribute to the stability of anxiety and depression over time. Academic achievement Academic achievement during adolescence is predicted by interpersonal (e.g., parental engagement in adolescents’ education), intrapersonal (e.g., intrinsic motivation), and institutional (e.g., school quality) factors. Academic achievement is important in its own right as a marker of positive adjustment during adolescence but also because academic achievement sets the stage for future educational and occupational opportunities. The most serious consequence of school failure, particularly dropping out of school, is the high risk of unemployment or underemployment in adulthood that tends to follow. High achievement can set the stage for college or future vocational training and opportunities. REFERENCES 1. Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71, 1072–1085. ↵ 2. Dick, D. M., Meyers, J. L., Latendresse, S. J., Creemers, H. E., Lansford, J. E., … Huizink, A. C. (2011). CHRM2, parental monitoring, and adolescent externalizing behavior: Evidence for gene-environment interaction. Psychological Science, 22, 481– 489. ↵ 3. Smetana, J. G. (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. ↵ 4. Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Soensens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2013). Autonomy in family decision making for Chinese adolescents: Disentangling the dual meaning of autonomy. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 1184- 1209. ↵ 5. Brendgen, M., Vitaro, R., Tremblay, R. E., & Lavoie, F. (2001). Reactive and proactive aggression: predictions to physical violence in different contexts and moderating effects of parental monitoring and caregiving behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29(4), 293–304. ↵ 6. Choquet, M., Hassler, C., Morin, D., Falissard, B., & Chau, N. (2008). Perceived parenting styles and tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use among French adolescents: gender and family structure differentials. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), 43(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agm060 ↵ 7. Cota-Robles, S., & Gamble, W. (2006). Parent-adolescent processes and reduced risk for delinquency: The effect of gender for Mexican American adolescents. Youth & Society, 37(4), 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118x05282362 ↵ 8. Li, X., Feigelman, S., & Stanton, B. (2000). Perceived parental monitoring and health risk behaviors among urban low-income African-American children and adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 27(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00077-4 ↵ 9. Markham, C. M., Lormand, D., Gloppen, K. M., Peskin, M. F., Flores, B., Low, B., & House, L. D. (2010). Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 46(3 Suppl), S23-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.214 ↵ 10. Guilamo-Ramos, V., Jaccard, J., & Dittus, P. (Eds.). (2010). Parental monitoring of adolescents: Current perspectives for researchers and practitioners. Columbia University Press. ↵ 11. Rawatlal, N., Kliewer, W., & Pillay, B. J. (2015). Adolescent attachment, family functioning and depressive symptoms. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 21(3), 80-85. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJP.8252 ↵ 12. Meeus, W., Branje, S., & Overbeek, G. J. (2004). Parents and partners in crime: a sixyear longitudinal study on changes in supportive relationships and delinquency in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 45(7), 1288-1298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00312.x ↵ 13. Shomaker, L. B., & Furman, W. (2009). Parent-adolescent relationship qualities, internal working models, and attachment styles as predictors of adolescents’ interactions with friends. Journal or Social and Personal Relationships, 2, 579-603. ↵ 14. Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214. ↵ 15. Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley. ↵ 16. Furman, W., & Shaffer, L. (2003). The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 3–22). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. ↵ 17. Russell, S. T., Clarke, T. J., & Clary, J. (2009). Are teens “post-gay”? Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 884–890. ↵ 18. Harter, S. (2012). Emerging self-processes during childhood and adolescence. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney, (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 680-715). New York: Guilford. ↵ 19. Harter, S. (2006). The self. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3 Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 505-570). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ↵ 20. Ryan, A. M., Shim,S. S., & Makara, K. A. (2013). Changes in academic adjustment and relational self-worth across the transition to middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1372-1384. ↵ 21. De Wit, D. J., Karioja, K., Rye, B. J., & Shain, M. (2011). Perceptions of declining classmate and teacher support following the transition to high school: Potential correlates of increasing student mental health difficulties. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 556-572. ↵ 22. Birkeland, M. S., Melkivik, O., Holsen, I., & Wold, B. (2012). Trajectories of global selfesteem during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 43-54. ↵ 23. Côtè, J. E. (2006). Emerging adulthood as an institutionalized moratorium: Risks and benefits to identity formation. In J. J. Arnett & J. T. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century, (pp. 85-116). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association Press. ↵ 24. McAdams, D. P. (2013). Self and Identity. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. http://www.nobaproject.com. ↵ 25. Reisner, S. L., Katz-Wise, S. L., Gordon, A. R., Corliss, H. L., & Austin, S. B. (2016). Social epidemiology of depression and anxiety by gender identity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(2), 203-208. ↵ 26. Sinclair, S. & Carlsson, R. (2013). What will I be when I grow up? The impact of gender identity threat on adolescents' occupational preferences. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 465-474. ↵ 27. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2021). Preventing Bullying. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/yv/Bullying-factsheet_508_1.pdf ↵ 28. Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E., & Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying surveillance among youths: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/bullying-definitions-final-a.pdf ↵ 29. Rudolph, K. D. (2009). The interpersonal context of adolescent depression. In S. NolenHoeksema & L. M. Hilt (Eds.), Handbook of depression in adolescents (pp. 377–418). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis. ↵