08. Leadership Handbook author Helena Kovač, Martina Širol, Marinela Šumanjski

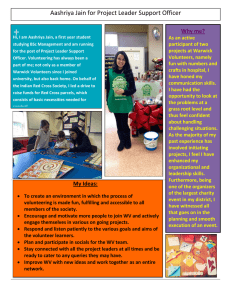

advertisement