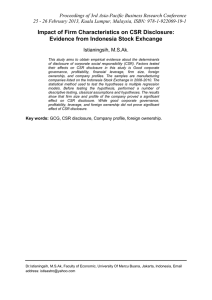

Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/csr.1428 Corporate Social Responsibility and Governance: Information Disclosure in Multinational Corporations Turhan Kaymak1* and Eralp Bektas2 1 Department of Business, Faculty of Business and Economics, Eastern Mediterranean University Famagusta, North Cyprus, Via Mersin 10Turkey 2 Department of Banking and Finance, Faculty of Business and Economics, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, North Cyprus, Via Mersin 10Turkey ABSTRACT Multinational corporations (MNCs) are facing increasing pressure on two fronts – the demand for more transparency and disclosure and the need to implement good corporate governance practices. This paper develops several testable hypotheses that address these issues based on agency theory and stakeholder management approach arguments. As such, the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs and firm-level governance structures are discussed. CSR is measured using Transparency International’s study on the disclosure practices of the world’s largest MNCs. Links between board size, board independence, and duality are explored. The results indicate that board independence and board size are strongly and positively related to several CSR practices. In addition, extractive industries have a significant and positive impact on the level of CSR activities. Policy and managerial implications related to these findings are also discussed. Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Received 12 October 2016; revised 27 March 2017; accepted 11 April 2017 Keywords: governance; corporate social responsibility; board structure; stakeholder engagement; disclosure; MNCs Introduction A LTHOUGH THEY HAVE ORIGINATED FROM DISTINCT ACADEMIC STRAINS OF THOUGHT, THE CONCERNS AND PROBLEMS ADDRESSED BY corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate governance (CG) are converging, as issues related to ethics, accountability, transparency, and disclosure now regularly influence business decisions. CSR is usually analyzed through the lens of the stakeholder management approach (Freeman, 1984), which stresses the importance of identifying and satisfying different groups that place divergent and sometimes contradictory demands on a firm. Hence, managers should not simply focus on maximizing the gains of one important group – the shareholder – at the expense of other stakeholders. On the other hand, CG issues are often *Correspondence to: Turhan Kaymak, Department of Business, Faculty of Business and Economics, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, North Cyprus, Via Mersin 10, Turkey. E-mail: turhan.kaymak@emu.edu.tr Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment T. Kaymak and E. Bektas tackled with the agency theory approach (Jensen & Meckling, 1976) which stipulates that to protect shareholders’ interests, a firm must establish several viable internal (e.g. board composition, independence, and size) and external mechanisms (e.g. takeover threats, vibrant labor markets) to oversee managerial decisions and align their interests with those of shareholders. As such, CG deals greatly with internal board structure issues in an ongoing effort to monitor managerial behavior to maximize shareholder gains, while CSR adopts more of an overarching public policy approach. Despite these differences, there are several trends leading to a convergence between CSR and CG. CG was founded on a legal basis that stressed the importance of managerial fiduciary duty towards shareholders, while CSR has its roots more in fluid socioeconomic and cultural processes. With the advent of numerous corporate scandals, the growing awareness of the impact firms have on the environment, and with the rise of pressure groups such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society groups, we are witnessing a profound change in CG practices. Now CG encompasses not just the rules and regulations that are used for monitoring managerial behavior, but also considers issues related to ethics, accountability, and disclosure (Lerach, 2002). In short, this new CG regime places greater emphasis on transparency and a commitment to fairness, and hence leads to greater disclosure of internal and external company practices. Thus, we see that the CSR approach, which balances the needs of disparate groups with the goals of shareholders, has been incorporated into a CG framework that now addresses the concerns of the social, environmental, and public arena (McBarnet 2007).Today, many large firms have developed several self-regulatory devices on a voluntary basis which include corporate codes of conduct, non-financial reporting practices, and the creation of institutional channels to establish a dialogue with stakeholders. We now observe interactions between institutional investors and NGOs with firms, as these organizations assist the firms in improving their self-regulation efforts. This is leading to CG practices that address many of the issues traditionally found within the realm of CSR (Rahim & Alam, 2013). Indeed, alongside CG issues, CSR is increasingly being linked to business strategy as managers realize that competitive advantages can be obtained by engaging with different groups while making important decisions and appreciating that performance is a multifaceted concept. A growing body of CSR research looks at strategic issues that range from environmental sustainability to firm-level competitiveness, and from supply chain management to corporate reputation. The environmental sustainability perspective is perhaps the most well researched as it argues that sound environmental management, besides having an ethical and legal component, also can help build firm value (Eccles et al., 2014). Several findings indicate a positive relationship between environmental management and superior performance (Florida & Davison, 2001; Nollet et al., 2016). Likewise, from a competitiveness perspective, CSR has been analyzed in both large (Melé et al., 2006) and small firms (Baumann-Pauly et al., 2013), and in different sectors (Alcaraz & Rodenas, 2013) such as in technology firms (Bernal-Conesa et al., 2017). CSR has been found to be associated with competitiveness in firms that follow a proactive approach in engaging with stakeholders (Marín et al., 2012). In addition, supply chain management activities have recently received more attention from CSR scholars, as the sophistication and global reach of the modern supply chain offers firms many areas to reduce waste and meet customer expectations in offering a green product (Carter et al., 2000; Harms et al., 2013; Lintukangas et al., 2015). Last, from a corporate reputation perspective, we see that higher quality sustainability reporting is associated with relevant stakeholders having a higher opinion of a firm (Clarke & Gibson-Sweet, 1999; Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017) leading to enhanced legitimacy and easier acquisition of resources. In this broad field of research, we decided to analyze CSR through the theoretical lenses of the agency model and stakeholder management approach. As such, this study attempts to further unravel the growing interconnectedness between CG practices and CSR efforts. Several board characteristics – board size, board independence, and duality – are considered when exploring CG’s relationship with CSR practices. As CSR covers many dimensions, ranging from employee rights to customer service to paying taxes, large firms need a formal approach to respond to these different and sometimes conflicting demands. The rise of the Internet, social media, and international pressure groups has placed the actions of companies firmly in the spotlight, and negative publicity may lead to enhanced government scrutiny and regulations. Transparency International (TI), a Berlin-based NGO, is a leading force that measures national levels of corruption. However, it has recently focused its efforts on multinational corporations (MNCs) to establish a dialogue with these global players and enhance their accountability toward society. As such, TI has developed a scale that measures the level of company efforts in anti-corruption efforts, organizational practices, and degree of transparency in identifying sources of revenue. This is an effort to entice MNCs to enhance their disclosure Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr CSR, governance, and disclosure in MNCs practices and can be considered to be a measure of CSR for these firms. MNCs are believed to be one of the main beneficiaries of globalization and are mostly enjoying expanding sales and growing profits. While pursuing profits these firms may be gaining undue influence over regulators and government officials through corrupt practices (e.g. bribery, tax evasion, environmental degradation). This conduct is mostly to the detriment of stakeholders outside of shareholders (Adeyeye, 2012). Growing scrutiny from the media and international organizations like the United Nations Convention against Corruption and labor groups such as the International Trade Union Federation has compelled many MNCs to upgrade their CSR efforts. CSR can be reflected in sustainability reporting programs that cover social, environmental, and economic activities (Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012). In this paper, CSR is measured by the degree of voluntary disclosure exhibited by MNCs – namely the level of transparency on corporation shows on issues related to society, the legal environment, and revenue generation. We maintain that transparency and disclosure can be considered as a measure of CSR, as the latter is a fluid concept embracing activities that satisfy different interest groups. As such, we examine the relationship of board characteristics (which is an indicator of CG) with CSR, by controlling for performance, company size, and the national origin of the firms. Basically, do MNCs that exhibit high levels of CSR have different board profiles than firms that have low levels of CSR? MNCs are important international actors and each faces unique institutional and regulatory pressures that emanate from their country of origin or sectors of operation. We look at the world’s largest 105 firms as measured by market capitalization that have been identified by TI to uncover issues connected to transparency and corporate disclosure. The paper is structured as follows. We first review the literature on board structure from the agency theory and stakeholder management approaches to uncover any associations between CG and CSR. The TI disclosure system is also discussed. Next, we present our data and methodology, to be followed by a presentation of the empirical results. The last section provides our discussion and conclusion. Stakeholder Management Theory, Agency Theory, and Hypotheses Development CSR and the Stakeholder Management Approach CSR is based on the theoretical foundation laid by the stakeholder management approach. Stakeholder management theory has recently witnessed a convergence with CG as now in many organizations CG procedures also require managers to consider their stakeholders (Spitzeck, 2009). As such, an effective CG approach can also support CSR efforts by promoting sound business practices that meet enhance accountability, transparency, and disclosure expectations of all interested parties. In this light, Freeman (1984) maintains that managers should facilitate the establishment of links with participants in the social and political process, and focus on building coalitions with external stakeholders. Freeman (1984) also puts forward that managers must be cognizant of the organization’s mission, and play an active role in maintaining the organizational processes and the set of transactions that occur among the organizations and their stakeholders. Thus, a firm’s stakeholders include the government, the community, customers, competitors, NGOs, the media, besides others. This can lead to a delicate balancing act, as myriad stakeholders place divergent and conflicting demands on the firm. Wood (1991) builds on this, and maintains that managers have a moral duty to pursue socially beneficial actions. Similarly, Donaldson and Preston (1995) develop a model to assist managers in balancing the need for profitability with the demands of stakeholders. In sum, stakeholder management theory posits that managers develop CSR programs to simultaneously fulfill their moral, ethical, and social duties, while also addressing shareholder expectations regarding financial goals. CG and Agency Theory Agency theory is at the heart of many discussions on CG issues. It addresses the problems that occur when one party (the principal or shareholder) delegates work to another party (the agent or manager). If the principals and agents have divergent goals and different risk preferences, conflict may arise. Thus, the principal must devise a structure to monitor the actions of the agent since the agents may benefit from information asymmetries that accrue Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr T. Kaymak and E. Bektas due to their intricate knowledge of running the firm. Hence, the principal must either have a system that provides for active monitoring of the managers and/or a mechanism that aligns the interests of the managers with those of shareholders. One solution to the agency problem resulting from managerial opportunism is through the effective use of board of directors (Fama & Jensen, 1983). The board of directors is the main decision-making group in an organization. The board’s composition and structure reflects the level of good governance practices in a corporation. The board develops the company mission and oversees company strategy and investments. The board also has a fiduciary duty to protect shareholder investments, and accordingly must fire/hire managers and monitor executive behavior vigilantly. As such, the board sits at the crux of CG, as it sets broad company policy, including how to deal with stakeholders and subsequently decides on the levels of corporate transparency and disclosure. Hence the board, along with top management, is at the forefront of CSR issues. There is an extensive body of research that looks at board structure and composition (board independence, board size, duality, internal committees) and how it relates to performance. Here, as we search for links between CSR and CG, we assume that a firm following prescribed CG practices regarding its board structure will be associated with higher levels of CSR by displaying greater transparency and disclosure. Board Structure Issues: Independent Boards, Board Size, and Duality A copious amount of research has been conducted on the relationship between board independence and corporate performance (Daily & Dalton, 1993; Rhoades et al., 2000; Nicholson & Kiel, 2007). In its simplest form, we have two groups of directors – insiders and outsiders. Insiders are current or former employees of the firm who may have privileged access to special information. Outsiders are directors with no known direct links to the firm and thus may be more objective and benefit from a divergent viewpoint. Agency theory points to the benefits of having outsider board members who can question managerial decisions and conduct more thorough monitoring activities (Dalton et al., 1998). However, these outsiders should have the knowledge, the background, and the capacity to monitor effectively. An opposing view states that an insider dominated board is preferred due to its more cohesive nature, better access to information, and quicker decision-making potential (Fama & Jensen, 1983). Agency theory posits that information asymmetries that inherently reside in organizations due to managers having more information than the shareholders can be mitigated by an active board which guards against managerial concealment and distortion. One would expect an independent board to question management more rigorously and promote the disclosure of information. Regarding studies conducted on the relationship between board independence and transparency there are conflicting findings. For instance, Donnelly and Mulcahy (2008), Lim et al. (2007), and Cheng and Courtenay (2006) uncover a positive association between board independence and voluntary disclosure. Likewise, Ferrero-Ferrero et al. (2015) uncover that board diversity is associated with CSR management and quality in listed European firms. On the other hand, Eng and Mak (2003), Barako et al. (2006), and Gul and Leung (2004) find voluntary disclosure to have a significant negative relationship with the number of outside directors sitting on the board. Stakeholder management theory posits that independent members (outsiders) will be in a better position to represent stakeholders and not be beholden to dominant groups and vested interests in the organization. Outsiders will have a better dialogue with groups outside the organization, and this should reflect in greater transparency and disclosure (Carroll, 2000). Stakeholder management is built on the premise that firms should reach out to their different constituencies to address their demands (Freeman, 1984). Having outsiders allows a firm to engage in more boundary spanning activities (Thompson, 1967) and this may be reflected in greater transparency and disclosure, and thus represent a higher degree of CSR. The diverse institutional environments that MNCs occupy, and the increased media scrutiny that they face should compel these firms to seek better linkages with their stakeholders and enhance their CSR efforts. As such, we have developed the following hypothesis: H1: An independent board (a higher outsider/insider ratio) is associated with higher levels of CSR in MNCs. Agency theory presents two diverging views on the presence and efficacy of large boards. On a positive stance, greater membership may increase the board’s monitoring capabilities, but this may be offset by the slower communication needs and less efficient decision-making process associated with large groups. A lack of a cohesive Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr CSR, governance, and disclosure in MNCs framework may actually cause conflict in the group, and thus diminish the board’s monitoring capacity. Research by Lipton and Lorsch (1992) and Jensen (1993) have uncovered such problems. Likewise, Yermack’s (1996) study found firm valuation to be negatively related to board size. However, there is a dearth of studies conducted on the relationship between board size and transparency. In Irish companies, Donnelly and Mulcahy (2008) found a positive relationship between board size and the level of voluntary disclosure, while Cheng and Courtenay (2006) failed to find a relationship in Singapore. In contrast, Byard et al. (2006) uncovered a negative relationship between board size and the accuracy of voluntary earnings forecasts in US corporations. Stakeholder management theory implies that a greater board size will indicate an organization’s need to link itself to the outside environment (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). More members on a board representing different groups will potentially enable the firm to reach out to its different stakeholders. Indeed, in their study on publicly traded US firms Luoma and Goodstein (1999) uncovered that larger firms placed a greater number of stakeholders on their boards. Similarly, when looking at the dissemination of corporate social reporting in numerous countries Frias-Aceituno et al. (2013) find that board size is positively related to the spreading of information. These findings support the position that firms try to accommodate divergent claims by expanding board membership and may hence promote transparency and disclosure. However, the issue of the relationship between transparency and board size has not been fully resolved and it in need of further empirical investigation. Additionally, board size is related to industry (financial firms tend to have large boards) and a firm’s national origin (some government dictate the minimum and maximum board size and the number of outsiders on the board). Again, this paper assumes that higher levels of transparency and disclosure to be indicative of greater CSR. Hence, we state the following hypothesis: H2: There is a positive association between board size and levels of CSR in MNCs. Duality is a situation where the Chairperson of the Board is also the CEO, leading to a consolidation of power in one individual. Here we have a peculiar situation where the agent (the CEO) is being monitored by themself (the Chairperson). Also, this arrangement is believed to lead to less adaptability and flexibility in responding to organizational challenges. Despite the potential negative ramifications of duality there is little empirical evidence regarding its effect on financial performance. Proponents of this unitary leadership system point to its benefits – more decisive action, quicker decision making, and greater responsiveness to changing market conditions. Also, this structure may help retain individuals with unique talents and ability who are attracted to such a demanding position (Donaldson & Davis, 1991). On the other hand, duality goes against the prescriptions provided by agency theory. A dominant figure may emerge, leading to opportunistic behavior. The possibility of collusion between top management and board members may arise, and generally the monitoring and disciplining capacity of the board may be degraded. Numerous studies have uncovered the negative relationship between duality and performance (Yermack, 1996; Fosberg, 2004; Lakhal, 2005). Indeed, in a cross-national study of stakeholder-centric governance, Shahzad et al. (2016) found a positive relationship between lack of duality and corporate social performance. Likewise, in a study conducted on the relationship between duality and financial transparency and disclosure as Forker (1992) reports a positive relationship between duality and transparency. However, the findings on duality are equivocal, as Donnelly and Mulcahy (2008), Cheng and Courtenay (2006), and Barako et al. (2006) fail to find a relationship between duality and voluntary disclosure. Stakeholder management theory supports the separation of these roles in the corporation. An individual holding these two key positions can lead to an excessive consolidation of power and shut out diverging views that represent different groups and their interests. A submissive board that does not question managerial behavior adequately would lead to diminished transparency and disclosure as the concerns of different stakeholders would not be considered in depth, resulting in diminished CSR efforts. In MNCs, which have an even wider group of stakeholders than their domestic counterparts, this situation would be exasperated. Hence, we have our final hypothesis: H3: Duality is associated with lower levels of CSR in MNCs. Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr T. Kaymak and E. Bektas Data and Methodology In this section, we present the employed variables in the study and discuss the multivariate ordinary least squares (OLS) model used to examine the relationship between CSR and the explanatory variables. Transparency and Corporate Disclosure: A CSR Framework The extensive media coverage of corporate scandals and the advent of more intrusive government regulation have placed the issue of transparency and voluntary disclosure near the top of the agenda for large firms, especially MNCs. However, this topic has been closely examined by scholars for decades. Cerf’s (1961) seminal work provides us with an early effort to analyze firm disclosure by analyzing quantitative and qualitative information released in annual reports, and seeking to uncover any relationship with corporate specific attributes. Most information released by firms generally targets the investment community, which includes financial analysts, creditors, investors, and government regulators. The information released is generally mandatory, which is imposed by regulatory bodies. We have two types of disclosure – mandatory and voluntary. The information released under mandatory disclosure is set and governed by regulatory agencies, while voluntary disclosure happens when firms provide more information than required as they believe there are benefits from doing so. These benefits associated with reducing information asymmetry include an enhanced reputation, less government regulation, and easier access to capital (Entwistle, 1997). This study considers both types of disclosure efforts. Studies on the relationship between corporate disclosure and CSR have used myriad sources. Li et al. (2013) utilize the Blue Book of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting by A-Share Listed Firms, while Willis (2003) uses The Global Reporting Initiative Sustainable Disclosure Database, and Hoje and Harjoto (2011) employ the Investor Responsibility Research Center, Inc., and Kinder, Lydendenberg, and Domini’s Stats Database to measure the degree of CSR. To the best of our knowledge there are no studies that utilize TI’s project on corporate disclosure. The TI project Transparency in Reporting on Anti-corruption and Promoting Revenue Transparency covers both voluntary and mandatory disclosure to assess the prevalence of corruption-relevant measures in 105 of the world’s largest publicly traded firms based on their market value at the end of 2010. This study does not include financial firms in the analysis as they tend to have much larger board sizes, face more restrictive regulatory environments, and were facing an industry-wide crisis during this period. Hence, the final sample size included a total of 80 firms. Data on these firms were collected from publicly available information sources and company websites, and was complemented with consultations with the firms under study, civil society, and TI’s network of national chapters. There are three dimensions examined – reporting on anti-corruption programs (ACPs), organizational transparency (OT), and country-by-country (CBC) reporting – which have been measured with 26 questions that can be found in Table 1. Each firm also receives an overall score ranging from 0 to 10 on this index based on an aggregate measure of the three dimensions, with higher marks indicating superior disclosure. For further details, refer to www. transparency.org. This study uses this index and its components as a proxy for CSR since transparency and disclosure on issues related to corruption in society influence numerous stakeholders. As corruption leads to lower economic growth, inequality in society, environmental degradation, and poor government services (Aidt, 2009), MNCs that acknowledge the importance of transparency are acting as good global citizens. On the corporate governance front, we measure board size, board independence, and duality by using information provided by Bloomberg’s businessweek.com for the 80 non-financial MNCs that were included in the TI study. For each company, the names of board members were identified and members have been subsequently classified as being ‘insiders’ or ‘other’. Here, we assume that members of the ‘other’ group are ‘outsiders’. Board size is measured with the logarithm of a simple head count, while board independence is measured by dividing the number of outsiders with the total board size. Also, board members who also hold executive positions are identified, enabling us to determine cases of duality. In cases where there were missing data, we utilized the Financial Times Market Watch database as it provides similar information. Several control measures are also included in the analysis that in prior research have been found to be associated with CSR (Eng & Mak, 2003). Specifically, we control for firm size, profitability, industry, and the institutional Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr CSR, governance, and disclosure in MNCs I. Disclosed anti-corruption programs 1. Does the company have a publicly stated commitment to anti-corruption? 2. Does the company publicly commit to be in compliance with all relevant laws, including anti-corruption laws? 3. Does the company leadership demonstrate support for anti-corruption, e.g. is there a statement in a corporate citizenship report or in public pronouncements on integrity? 4. Does the company’s code of conduct/anti-corruption policy explicitly apply to all employees? 5. Does the company’s code of conduct/anti-corruption policy explicitly apply to all agents and other intermediaries? 6. Does the company’s code of conduct/anti-corruption policy explicitly apply to contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers? 7. Does the company have an anti-corruption training program for its employees in place? 8. Does the company have a policy defining appropriate/inappropriate gifts, hospitality and travel expenses? 9. Is there a policy that explicitly forbids facilitation payments? 10. Does the company prohibit retaliation for reporting the violation of a policy? 11. Does the company provide channels through which employees can report potential violations of policy or seek advice (e.g. whistleblowing) in confidence? 12. Does the company carry out regular monitoring of its anti-corruption program? 13. Does the company have a policy prohibiting political contributions or if it does make such contributions, are they fully disclosed? II. Organisational transparency (disclosure of subsidiaries) 14. Does the company disclose the full list of its fully consolidated material subsidiaries? 15. Does the company disclose percentages owned in its fully consolidated material subsidiaries? 16. Does the company disclose countries of incorporation of its fully consolidated material subsidiaries? 17. Does the company disclose countries of operations of its fully consolidated material subsidiaries? 18. Does the company disclose the full list of its non-fully consolidated material subsidiaries? 19. Does the company disclose percentages owned in its non-fully consolidated material subsidiaries? 20. Does the company disclose countries of incorporation of its non-fully consolidated material subsidiaries? 21. Does the company disclose countries of operations of its non-fully consolidated material subsidiaries III. Country -by-country disclosure In our study, ‘countries of operations’ are those countries in which a company is present either directly or through one of its consolidated subsidiaries. The relevant list of countries of operations is based on the company’s own reporting. For each country of the company’s operations the following set of questions has been asked: 22. Does the company disclose its revenues/sales in country X? 23. Does the company disclose its capital expenditure in country X? 24. Does the company disclose its pre-tax income in country X? 25. Does the company disclose its income tax in country X? 26. Does the company disclose its community contribution in country X? Table 1. Questionnaire on transparency in reporting on anti-corruption and promoting revenue transparency environment. Size is measured using the logarithm of total revenue, and profitability with return on assets (ROA). This information was provided by either the businessweek.com or Market Watch databases. The TI index identifies the national origin and industry where each firm operates. The institutional environment is a multidimensional construct that we account for with two measures that may affect both CSR practices and governance structures (North, 1991). First, the legal environment is measured with a dummy variable, with MNCs hailing from either a common-law system or civil code legal system. Second, the national level of corruption prevailing in the MNCs’ home country is measured by a logarithm of TI’s Corruption Perceptions Index and it is included as a control variable Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr T. Kaymak and E. Bektas in the model. Finally, to uncover any industry effects on CSR, another dummy variable is used to separate firms that operate in extractive (materials, oil and gas, and industrials) and non-extractive (technology and consumer goods and services) industries. The Model The OLS technique is employed to test the hypotheses for the cross-section data after specifying the following model: CSR ¼ α þ β1 INDP þ β2 LBS þ β3 DUAL þ β4 LREV þ β5 ROA þ β6 LAW þ β7 LNCOR þ β8 INDUSTRY þ Though our main motivation is to examine the effect of firm and country-level governance factors on CSR, as documented in previous literature (Husted & Allen, 2006), industry differences can also affect CSR. Therefore, we also employ an industry dummy variable, and subsequently run four separate regression models on the dependent variable CSR as the TI index has three components (ACP, OT, and CBC) and an overall index score (INDEX). The model variables are defined as follows: ACP: anti-corruption programs OT: organizational transparency CBC: country-by-country reporting INDEX: overall composite score for CSR INDP: proportion of independent directors on the board LBS: logarithm of the board size DUAL: dummy variable equal to 1 if CEO is also the chairman, 0 if otherwise LREV: logarithm of total annual revenue ROA: return on assets LAW: dummy variable equal to 1 if company is based in a common-law country, 0 if otherwise LNCOR: logarithm of the national corruption score INDUSTRY: dummy variable equal to 1 if company is operating in technology and consumer goods and services, 0 if it is in materials, oil and gas Empirical Results Descriptive Statistics We calculated the descriptive statistics and conducted a bivariate correlation analysis on the independent and dependent variables employed in the study (Tables 2 and 3). By analyzing the descriptive statistics, we can see that the mean CSR INDEX score is 4.97 out of a possible 10. The ACP and OT mean scores are similar respectively, 72% Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr CSR, governance, and disclosure in MNCs Variable Obs Mean Std. Dev. Min ACP OT CBC INDEX INDP LBS DUAL LREV ROA LAW LNCOR INDUSTRY 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 80 .717875 .730625 .0403875 .49675 .8121595 1.129098 .5375 1.85662 .0723958 .55 1.833967 .6375 .214887 .2753793 .0810459 .1344541 .1363285 .104703 .5017375 .3311217 .0394686 .5006325 .1003953 .4837551 0 .25 0 .19 .4210526 .90309 0 1.260071 .00846 0 1.447158 0 Max 1 1 .5 .83 1 1.39794 1 2.677881 .2278 1 1.934498 1 Table 2. Descriptive statistics (number of observations, mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum) of the dependent and explanatory variables. The dependent variables ACP, OT, CBC, and INDEX represent anti-corruption programs, organizational transparency, and country-by-country reporting and index, respectively. The explanatory variables are the board independence (INDP), logarithm of the board size (LBS), duality of the general manager (DUAL), logarithm of revenue (LREV), return on assets (ROA), legal origin of the corporation (LAW), logarithm of national corruption score (LNCOR), and type of INDUSTRY (INDUSTRY) ACP OT CBC INDEX INDP LBS DUAL LREV ROA LAW LTICOR INDUSTRY ACP OT CBC 1 0.1139 0.1182 0.6338* 0.4751* -0.0543 0.0213 -0.0936 0.0954 0.2463* 0.4737* -0.1037 1 0.3790* 0.8178* 0.0266 0.3327* 0.1555 0.1995 0.2658* 0.3377* 0.0804 0.2102 1 0.5211* 0.1083 0.137 0.0678 0.0578 0.0715 0.0106 0.0535 0.2427* INDEX INDP LBS DUAL LREV ROA LAW LTICOR INDUSTRY 1 0.2143 1 0.1729 0.2002 1 0.1126 0.1299 0.0453 1 0.1042 0.1291 0.1016 0.1218 1 0.1486 0.0485 0.3728* 0.059 0.2737* 1 0.1029 0.1454 0.3695* 0.2192 0.2095 0.3124* 1 0.2068 0.2546* 0.015 0.0333 0.1045 0.0588 0.2201* 1 0.2460* 0.0603 0.0464 0.1258 0.1836 0.1624 0.1019 0.2666* 1 Table 3. Correlation matrix *indicates p < 0.05 significance level. The dependent variables ACP, OT, CBC, and INDEX represent Anti-Corruption Programs, Organizational Transparency, and Country by Country Reporting and Index respectively. The explanatory variables are the board independence (INDP), logarithm of the board size (LBS), duality of the general manager (DUAL), logarithm of revenue (LREV), return on assets (ROA), legal origin of the corporation (LAW), logarithm of national corruption score (LNCOR), and type of industry (INDUSTRY). and 73% out of a possible 100%, while the CBC mean score is only 4%. The last result indicates that most firms in the sample do not engage in onerous CBC reporting practices as requested by TI and this casts doubt on whether this measure should be considered in future studies. We also see that 54% of the firms exhibit duality, while 56% hail from countries which use a common-law system. From Table 3, we can see that several variables exhibit significant correlations with one another. ACP is significantly related to INDP and common law countries (LAW) at the 5% significance level. However, OT is negatively related to common law countries (i.e., it is positively associated with the use of a civil code system) but is negatively related to ROA at the 5% significance level. On the other hand, we see that BS is negatively related to INDP, LAW, and ROA. Not surprisingly, the independent variables of ACP, OT, and CBC are significantly related to the composite corporate responsibility measure, INDEX. Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr T. Kaymak and E. Bektas Multivariate Analysis Table 4 provides the results for the multivariate regression models which are robust for possible heteroscedasticity problem. To check for multicollinearity a variance inflation factor test was also conducted and the result (1.55) indicates that this is not a problem in the data. In sum, to segregate the industry factor from the firm base and country base institutional factors, four regression equations are estimated to test our hypotheses. In the first model (ACP), both firm- and country-specific governance variables together with industry dummy and control variables are regressed on the anti-corruption program variable. Among the firm specific governance variables, INDP takes on a positive and statistically significant value (p < .01). The positive and high coefficient value of this variable suggests that, as boards become more independent, firms increase their CSR efforts. Hence, when countries demand that MNCs design a more independent board we witness less corrupt and more socially responsible multinationals. This finding also supports the stakeholder management view where outsiders play a vigilant role to the benefit of other stakeholders. The significance of INDP also supports the new CG regime that delegates substantial role to CSR (Lerach, 2002; McBarnet, 2007; Rahim & Alam, 2013). Corruption variables that represent the institutional environment in the country are also significant and positive (p < .01). These findings show that in addition to firm specific governance, aspects of the institutional environment are also important. As such, if countries improve their institutional environments these conditions will entice MNCs to behave in a more VARIABLES Constant INDP LBS DUAL LREV ROA LAW LNCOR INDUSTRY R-squared F-test (Prob.) No. obs. ACP 1.610*** (0.557) 0.624*** (0.236) 0.249 (0.241) -0.0469 (0.0407) -0.0141 (0.0485) 0.434 (0.609) 0.0720* (0.0420) 0.873*** (0.283) -0.129*** (0.0405) 0.454 6.01 (0.00) 80 OT 0.0928 (0.647) 0.187 (0.262) 0.675** (0.333) 0.0772 (0.0584) 0.0626 (0.0923) 0.544 (0.897) 0.0905 (0.0678) 0.00191 (0.284) 0.115* (0.0586) 0.239 3.22 (0.00) 80 CBC 0.0995 (0.197) 0.0962 (0.0677) 0.159 (0.146) 0.0171 (0.0183) 0.00436 (0.0226) 0.245 (0.250) 0.000489 (0.0295) 0.143 (0.150) 0.0449* (0.0265) 0.135 1.08 (0.38) 80 INDEX 0.536* (0.294) 0.242 (0.166) 0.255 (0.172) 0.0478 (0.0292) 0.0169 (0.0439) 0.124 (0.442) 0.00706 (0.0345) 0.336** (0.158) 0.0954*** (0.0320) 0.256 4.40 (0.00) 80 Table 4. Empirical results for each CSR measure The dependent variables ACP, OT, CBC, and INDEX represent Anti-Corruption Programs, Organizational Transparency, and Country-byCountry Reporting and Index, respectively. The explanatory variables are the board independence (INDP), logarithm of the board size (LBS), duality of the general manager (DUAL), logarithm of revenue (LREV), return on assets (ROA), legal origin of the corporation (LAW), logarithm of national corruption score (LNCOR), and type of industry (INDUSTRY). The values of R2 and F statistics and their respective pvalues, as well as number of observations are presented in the table. Standard error in parentheses. *, **and ***represent significance levels at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively. Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr CSR, governance, and disclosure in MNCs socially responsible manner. In addition, the industry variable reveals that extractive industries are more inclined to have and disclose their anti-corruption programs compared to technology and consumer services oriented corporations. This can be explained by stakeholder theory (Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Waddock & Graves, 1997) or the demand-driven (Lyon & Maxwell, 2008) behavior approach which posit that outside pressure compels corporations to be more informative towards society. According to this view, stakeholders play crucial role in determination of CSR by exerting pressures from various aspects on firms (Swanson, 1995). Lastly, the results reveal that ACP is significantly related to LAW (p < .10). This latter finding implies that leading MNCs originating from common law countries display higher levels of anti-corruption practices. Henceforth, pertinent regulatory changes can contribute to CSR developments. Organizational transparency is very crucial for the stakeholders in a sense that it provides access to corporate information. As Firth (1979) asserts, the public care more about this in large corporations. This motive encourages stakeholders to demand more information and improve the control mechanism over the corporation from the CSR perspective. In the second model (OT), though the explanatory power is lower relative to ACP models, the industry variable and board size variable (LBS) take on statistically significant values (p < .10 and p < .05), respectively. Nevertheless, the lower coefficient value and significance of the industry variable, suggest a weaker role for it in the determination of organizational transparency among industries. On the other hand, a positive and high coefficient of LBS suggests that board size is important in determining organizational transparency. In other words, larger boards make multinational corporations more transparent as they represent a more diverse set of stakeholders. As such, our findings suggest that larger boards are better for CSR activities. As it can be seen from Table 1, the CBC disclosure section (section III), is composed of accounting disclosure type questions. As such, the third model (CBC) can be used to understand and evaluate the determinants of accounting disclosure and accountability behavior of MNCs. Though the role of accountability and accounting is shifting from ownership to a stakeholder approach due to greater accountability demands by stakeholders (Gray et al., 1987; Bushman & Smith, 2001), our CBC model fails to support this policy. Also, it has been documented in the literature that managers may have various motives, such as impeding the market’s monitoring mechanism (Karamanou & Vafeas, 2005) and maintaining managerial benefits (Owen et al., 2000), to not disclose corporate information to the public. And these may be among the reasons leading to an insignificant model. As Table 1 indicates, the fact that only a few companies in the sample engage in CBC disclosure (a 4-point average score out of a possible 100) makes the findings here tenuous at best. The fourth model, the overall INDEX model, investigates the relationships between the level of CSR displayed by the firms and the variables of interest, namely ACP, OT, and CBC. The model reaches significance (F test = 4.40, p < 0.00; R2 = 0.256). Pertaining to the variables studied it appears that industry and national corruption levels have an influence on CSR at a statistically significant level. The negative coefficient of the industry variable suggests that greener industries (technology, consumer, and services) are less socially responsible than the extractive businesses. The national corruption variable, which is statistically significant at the 5% level, supports the idea that in a less corrupt environment CSR activities are enhanced. Concerning the firm based governance variables (LBS, DUAL, and INDP), none of them reach significance in the model, unlike in models 1 and 2. This is mostly due to the CBC variable that is included in the INDEX model. Last, as in the other models the control variables (ROA and LREV) also fail to reach significance, and do not exhibit any relationship with CSRs. In sum, our findings show that different aspects of corporate social responsibility are determined by different factors. Nevertheless, the industry type is the most prominent variable in all models. Our findings also produce statistically significant values for INDP, LNCOR, LBS and provide some support for the hypotheses developed in this study. Concerning the explanatory power of the models, the anti-corruption program (model 1) stands out. Conclusion and Discussion This study utilizes TI’s data to examine the level of transparency and disclosure that leading MNCs exhibit on three different dimensions, making it a suitable proxy for a measurement of CSR. Our findings point to several major issues as we seek to uncover the relationship between CSR and governance practices. First, we uncover the Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr T. Kaymak and E. Bektas important role played by independent boards. As theory and good management practices suggest, CSR (in the form of having anti-corruption programs) is associated with boards that have a higher proportion of external members, which boosts board independence and decision-making capacity. This result is in line with agency theory and the stakeholder management approach. Agency theory focuses on the deleterious effect of information asymmetries and postulates that this problem can partially be mitigated using objective and unbiased external board members (Dalton et al., 1998). Likewise, the stakeholder management approach maintains that the representation of diverse groups on the board will enhance firm performance in the long run, as it leads to sustainable strategies (Freeman, 1984). Here, we find evidence supporting the above as MNCs with more external members serving on their boards exhibit higher levels of CSR reporting. We also find that larger boards are associated with more CSR (in the forms of enhanced organizational transparency) in MNCs. The presence of a greater number of board members allows for the presence of a more diverse group who represent different sets of stakeholders. This leads multinational firms to become more transparent in an effort to communicate with these groups and attempt to satisfy their demands. Divergence surfaced between firms based in civil code versus common law legal systems – namely that firms originating from common law systems are associated with greater reporting of accountability and anticorruption practices. This different orientation may stem from the more litigious environment found in common law systems, which compels firms to engage in such activities to preclude lawsuits. Mio and Venturelli (2013) found similar results when comparing the use of sustainability programs in a common law (UK) and civil code system country (Italy). However, these very tentative findings are open to further debate and investigation. The incorporation of industry effects and the level of national corruption existing in home countries also produced significant results. In line with Alberici and Querci (2016), we see that ‘suspect’ industries (e.g. extractive industries) engage in greater levels of CSR – this can be to ward off attention and scrutiny from action groups and governmental regulators. Thus, MNCs operating in extractive industries tend to develop CSR programs based on ‘image management’ that signals that firms are engaging in socially desirable activities. The presence of NGOs like Publish What You Pay and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative which demand more accountability in the extractive industry may contribute to this increased level of transparency uncovered here. Although we excluded financial firms from the analysis, in the USA the Dodd-Frank Act compels financial firms to disclosure more information as banks’ risky behavior and questionable practices. Similar to the extractive sector, the financial sector has a negative reputation regarding its treatment of some stakeholders although it exhibits high disclosure levels. On the other hand, we see that home country features also influence CSR. Here we uncover that lower national corruption scores are associated with greater CSR activity, as such societies tend to have a benefit from robust legal systems, stronger democratic traditions, and a more participating civil society that makes MNCs more accountable for their behavior. These conditions all facilitate the development of CSR programs in multinational firms. We proposed that CEO duality would hinder CSR efforts. However, no relationship was found between duality and CSR reporting in the MNCs. Over the decades, a copious amount of research has been conducted on the advantages and drawbacks of this system, with little consensus emerging. Possibly, scholars should omit studying the duality condition, as it seems to have limited impact on governance-related issues. Governance practices can be improved with wider stakeholder participation (Donaldson, 2002). As such, input from a tripartite partnership consisting of public, private, and non-profit actors should be considered when developing policy recommendations. Accordingly, it is advisable for MNCs to develop a platform that incorporates the views of advocacy non-governmental organizations such as TI and the Institute for Global Labor and Human Rights, as this would help bridge some of the trust issues that bedevil these international entities (Kolk & Lenfart, 2013). Enhanced and relevant information disclosure policies that are jointly developed could lead to greater legitimacy and help these firms address relevant issues related to their CSR activities. More generally, today MNCs are facing challenges and expectations that are commensurate with their status and visibility. Recent public debates about their extensive use of tax loopholes points to an issue that is closely connected to transparency and disclosure. One might surmise that the 14 billion USD tax bill imposed on (and contested by) Apple by the European Commission for diverting its European sales to Ireland could have been avoided had a more stakeholder-oriented approach been employed. Alongside better cooperation at the national government level, an approach that also incorporates and includes transnational organizations would help in the dissemination of good practices. For instance, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on CSR can be enhanced and strengthened regarding Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr CSR, governance, and disclosure in MNCs identifying elements to be included in effective corporate governance codes. Similarly, the UN Global Compact strategic policy initiative for businesses can be expanded to include specific recommendations on how MNCs respond to stakeholder needs. More specifically, these prescriptions should identify stakeholders and subsequently address the board structure and composition findings uncovered in this study. Finally, fully incorporating the CBC reporting aspect of TI’s survey is especially promising as it offers an opportunity for MNCs to provide transparency levels that go far and beyond legal financial disclosure requirements. Thus, from a managerial and policy perspective, regulators should continue with the trend to force publicly traded companies to include more external members on their boards and encourage the formation of larger boards. Our findings suggest that independent boards enhance transparency and disclosure. Firms that display such board compositions will contribute in fighting corruption, a problem that leads to considerable social, environmental, and economic losses. MNCs are at the forefront of globalization and should be encouraged to take an unequivocal public stance on issues related to graft. We also advocate that larger boards should be formed to promote stakeholder participation and lead to greater levels of organizational transparency. This study does have several weaknesses. First, we rely on the secondary measures developed by TI, whose survey includes a limited sample of MNCs covering only a single point in time. TI does not provide us with a theoretical underpinning behind the inclusion and development of the items included in the survey, raising reliability and validity issues. Second, after removing financial firms we have included only 80 MNCs in our analysis, and this may not be representative of the total population of leading firms. Third, a regression analysis does not measure for causality, and thus we cannot address the ultimate question – Do board structure variables lead directly to greater CSR efforts? In this light, the low explanatory of some of our models suggests that other environmental factors besides corporate governance issues are related to CSR. However, there are areas of opportunity for future research, especially by expanding the variables in the models tested here and incorporating additional national and international institutional factors (North, 1991) and cultural norms that may more fully explain CSR activity in MNCs. Another area worthy of further investigation is a comparative analysis between these leading MNCs and MNCs from emerging markets on board structure and transparency and disclosure activities. Globalization and the unhindered spread of information are placing additional demands and expectations on the world’s largest commercial entities. As such, the importance of following a business model that both incorporates diverse issues and interest groups, and which also more readily accounts for company behavior is becoming a topic of consequence in the confines of the boardroom. This study adds to this growing realization that CSR issues will demand more attention from managers and board members in the years to come. References Alberici A, Querci F. 2016. The quality of disclosures on environmental policy: The profile of financial intermediaries. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 23: 283–296. Alcaraz AS, Rodenas SP. 2013. The Spanish banks in face of the corporate social responsibility standards: previous analysis of the financial crisis. Review of Business Management 15: 562–581. Aidt TS. 2009. Corruption, institutions, and economic development. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 25(2): 271–291. Barako DG, Hancock P, Izan HY. 2006. Relationship between corporate governance attributes and voluntary disclosures in annual reports: The Kenyan experience. Financial Reporting, Regulation, and Governance 5: 1–25. Baumann-Pauly D, Wickert C, Spence LJ, Scherer AG. 2013. Organizing corporate social responsibility in small and large firms: size matters. Journal of Business Ethics 115: 693–705. Bernal-Conesa JA, Nieto NC, Briones-Penalver AJ. 2017. CSR strategy in technology companies: Its influence on performance, competitiveness, and sustainability. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 24: 96–107. Byard D, Li Y, Weintrop J. 2006. Corporate governance and the quality of financial analyst’s information. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 25: 609–625. Bushman RM, Smith AJ. 2001. Financial accounting information and corporate governance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 32: 237–333. Carroll AB. 2000. Conceptual and consulting aspects of stakeholder theory, thinking and management. Handbook of Organizational Consultation 2: 169–181. Carter CR, Kale R, Grimm CM. 2000. Environmental purchasing and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Transportation Research Part E 36: 219–228. Cerf AR. 1961. Corporate Reporting and Investment Decisions. The University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA. Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr T. Kaymak and E. Bektas Cheng ECM, Courtenay SM. 2006. Board composition, regulatory regime, and voluntary disclosure. The International Journal of Accounting 41: 262–289. Clarke J, Gibson-Sweet M. 1999. The use of corporate social disclosures in the management of reputation and legitimacy: a cross sectoral analysis of UK Top 100 Companies. Business Ethics 8: 5–13. Daily C, Dalton D. 1993. Boards of directors’ leadership and structure: Control and performance implications. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 17: 65–81. Dalton DR, Daily CM, Ellstrad AE, Johnson JL. 1998. Meta-analytic reviews of board composition, leadership structure, and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal 19: 269–290. Donaldson T. 2002. The stakeholder revolution and the Clarkson principles. Business Ethics Quarterly 12: 107–111. Donaldson L, Davis JH. 1991. Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management 16: 49–64. Donaldson L, Preston LE. 1995. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: concepts, evidence, and implications. The Academy of Management Review 20: 65–91. Donnelly R, Mulcahy M. 2008. Board structure, ownership, and voluntary disclosure in Ireland. Corporate Governance: An International Review 16: 416–429. Eccles RG, Ioannou I, Serafeim G. 2014. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science 60: 2835–2857. Entwistle GM. 1997. Managing disclosure: The case of research and development in knowledge-based firms. PhD Thesis. The University of Western Ontario: Canada. Eng LL, Mak YT. 2003. Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 2: 325–346. Fama EF, Jensen MC. 1983. Separation of Ownership and Control. Journal of Law and Economics 26: 301–325. Ferrero-Ferrero I, Fernandez-Izquiwerdo MA, Munoz-Torres MJ. 2015. Integrating sustainability into corporate governance: An empirical study on board diversity. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 22: 193–207. Firth MA. 1979. The effect of size, stock market listings, and auditors on voluntary disclosure in corporate annual reports. Accounting and Business Research 9: 273–280. Florida R, Davison D. 2001. Gaining from green management: Environmental management systems inside and outside the factory. California Management Review 43: 64–84. Forker JJ. 1992. Corporate governance and disclosure quality. Accounting and Business Research 22: 111–124. Fosberg RH. 2004. Agency problems and debt financing: Leadership structure effects. Corporate Governance: International Journal of Business in Society 4: 31–38. Freeman E. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA. Frias-Aceituno JV, Rodriguez-Ariza L, Garcia-Sanchez IM. 2013. The role of the board in the dissemination of integrated corporate social reporting. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20: 219–233. Gray R, Owen D, Maunders K. 1987. Corporate Social Reporting: Accounting and Accountability. Prentice-Hall: London, UK. Gul FA, Leung S. 2004. Board leadership, outside directors. expertise and voluntary corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 23: 351–379. Harms D, Hansen EG, Schaltegger S. 2013. Strategies in sustainable supply chain management: An empirical investigation of large German companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20: 205–218. Hoje J, Harjoto MA. 2011. Corporate governance and firm value: the impact of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 103: 351–383. Husted B, Allen D. 2006. Corporate social responsibility in the multinational enterprise: Strategic and institutional approaches. Journal of International Business Studies 37: 838–849. Jensen MC. 1993. The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems. Journal of Finance 48: 831–880. Jensen MC, Meckling WH. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–360. Karamanou I, Vafeas N. 2005. The association between corporate boards, audit committees, and management earnings forecasts: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting Research 43: 453–486. Kolk A, Lenfart F. 2013. Multinationals, CSR, and partnerships in Central African conflict countries. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20: 43–54. Lakhal F. 2005. Voluntary earnings disclosures and corporate governance: Evidence from France. Review of Accounting and Finance 4: 64–85. Lerach WS. 2002. Plundering America: How American investors got taken for trillions by corporate insiders – The rise of the new corporate kleptocracy. Stanford Journal of Law, Business, and Finance 69: 69–126. Li Q, Luo W, Wang Y, Wu L. 2013. Firm performance, corporate ownership, and corporate social responsibility disclosure in China. Business Ethics: A European Review 22: 159–173. Lim S, Matolcsy Z, Chow D. 2007. The association between board composition and different types of voluntary disclosure. European Accounting Review 16: 555–583. Lintukangas K, Hallikas J, Kähkönen A. 2015. The role of green supply management in the development of sustainable supply chain. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 22: 321–333. Lipton M, Lorsch J. 1992. A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. Business Lawyer 59: 59–77. Lyon T, Maxwell J. 2008. Corporate social responsibility and environment: A theoretical perspective. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 2: 240–260. Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr CSR, governance, and disclosure in MNCs Luoma P, Goodstein J. 1999. Stakeholders and corporate boards: institutional influences on board composition and structure. Academy of Management Journal 42: 553–563. Odriozola MD, Baraibar-Diez E. 2017. Is corporate reputation associated with quality of CSR reporting? Evidence from Spain. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 24: 121–132. Marín L, Rubio A, Ruiz de Maya S. 2012. Competitiveness as a strategic outcome of corporate social responsibility. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 19: 364–376. McBarnet D (Ed). 2007. The New Corporate Accountability: Corporate Social Responsibility and the Law. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK. Melé D, Debeljuh P, Arruda MC. 2006. Corporate ethical policies in large corporations in Argentina, Brazil, and Spain. Journal of Business Ethics 63: 21–38. Michelon G, Parbonetti A. 2012. The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. Journal of Management Governance 16: 477–509. Mio C, Venturelli A. 2013. Non-financial information about sustainable development and environmental policy in the annual reports of listed companies: Evidence from Italy and the UK. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20: 340–358. Nicholson GJ, Kiel GC. 2007. Can directors impact performance? A case-based test of three theories of corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review 15: 585–608. Nollet J, Fillis G, Mitrokosta E. 2016. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A non-linear and disaggregated approach. Economic Modelling 52: 400–407. North DC. 1991. Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives 5: 97–112. Owen D, Swift TA, Humphrey C, Bowerman M. 2000. The new social audits: accountability, managerial capture or the agenda of social champions? The European Accounting Review 9: 81–98. Pfeffer J, Salancik GR. 1978. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Harper and Row: New York, USA. Rahim M, Alam S. 2013. Convergence of corporate social responsibility and corporate governance in weak economies: The case of Bangladesh. Journal of Business Ethics 121: 607–620. Rhoades D, Rechner P, Sundaramurthy C. 2000. Board composition and financial performance: a meta-analysis of the influence of outside directors. Journal of Managerial Issues 12: 76–91. Shahzad AM, Rutherford MA, Sharfman MP. 2016. Stakeholder-centric governance and corporate social performance: A cross-national study. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 23: 100–112. Spitzeck H. 2009. The development of governance structures for corporate responsibility. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 9: 495–505. Swanson D. 1995. Addressing the theoretical problem by reorienting the corporate social performance model. Academy of Management Review 20: 43–64. Thompson JD. 1967. Organizations in Action: Social Science Bases of Administrative Theory. McGraw-Hill: New York, USA. Waddock SA, Graves SB. 1997. The corporate social performance – financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal 18: 303–319. Willis A. 2003. The role of the global reporting initiative’s sustainability reporting guidelines in the social screening of investments. Journal of Business Ethics 43: 233–237. Wood DJ. 1991. Social corporate performance revisited. The Academy of Management Review 16: 691–718. Yermack D. 1996. Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors. Journal of Financial Economics 40: 185–211. Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2017 DOI: 10.1002/csr