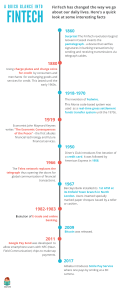

The discussion of the Basel disintermediated bank scenario is a discourse that encapsulates a plethora of concepts which need to be dissected meticulously for enhanced understanding and comprehension of the subject matter. This write up seeks to ultra-carefully scrutinize the subject matter of the Basel disintermediated bank scenario, it’s impact on incumbent banks’ business models and areas of existing product risk associated with the scenario. Key to this discussion are exhaustive definitions of financial technology and innovation (Fintech); and the concept of disintermediation. The Basel’s disintermediated bank scenario is an offspring of an expose on the impacts of financial technology and innovation by the Basel Committee on Bank Supervision. In accordance to the Financial Stability Board (FSB), “Financial technology (Fintech) refers to technologically-enabled financial innovation that could result in new business models, applications, processes, or products with an associated material effect on financial markets and institutions and the provision of financial services” (Davila et. al 2007). Financial technology (Fintech) is used to describe new tech that seeks to improve and automate the delivery and use of financial services, (www.investopedia.com). The term financial technology has not yet been exhaustively defined by most scholars as it is an emerging topic and a broad cross-disciplinary subject that combines Finance, Technology Management and Innovation Management. One of the enthralling definitions is by K Leong (2018) which says, “Fintech is any innovative idea that improves financial service processes by proposing technology solutions according to different business situations, while the ideas could also lead to new business models or even new businesses”. Interlinked to Fintech is the concept of disintermediation which is defined as a move from the intermediated provision of financial services via banks to direct financial relations between borrowers and lenders thereby eliminating the need for financial intermediaries (Chetty 2011). Bank disintermediation does not necessarily imply an overall decrease in financial intermediation however can imply that the role of banks shifts to the provision of financial services on a fee basis rather than the traditional interest earning basis (Pati and Shome, 2006). In a bid to assess the impact of financial technology and innovation on banking the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision proposed a multi-thronged scenario approach composed of five scenarios namely the new bank scenario, the better bank scenario, the distributed bank scenario, the relegated bank scenario and the disintermediated scenario. Of interest in this particular assignment is the Disintermediated Bank Scenario (Dean & Giglierano 2018) N. According to Leong (2018) the disintermediated bank scenario entails that incumbent or existing banks are no longer a significant player in the financial system because the need for balance sheet intermediation or for a trusted third party is removed. Banks are displaced from customer financial transactions by more agile platforms and technologies, which ensure a direct matching of final consumers depending on their financial needs (borrowing, making a payment, raising capital etc). In this scenario, customers may have a more direct say in choosing the services and the provider, rather than sourcing such services via an intermediary bank (Chishti and Barberis, 2016). However, they also may assume more direct responsibility in transactions, increasing the risks they are exposed to. In the realm of peer-to-peer (P2P) lending for instance, the individual customers could be deemed to be the lenders (who potentially take on credit risk) and the borrowers (who may face increased conduct risk from potentially unregulated lenders and may lack financial advice or support in case of financial distress); (Ernst and Young, 2014). An example of this scenario is the emergence of crypto-currencies such as Bitcoin which use public Distributed Ledger Transactions (DLT) such as blockchain technologies without the involvement of incumbent banks. For a successful detailed analysis of the impact of the disintermediated bank scenario two questions are crucial which are (i) which player leads the customer relationship, that is the user experience and interface, and (ii) which player eventually provides the services and bears the risk. Further question to take into consideration relates to potential changes in banks’ business models and the various roles traditional banks and other fintech companies may play in either owning the customer relationship or supporting banking activities as service providers. The latter question instead, involves who will ultimately be responsible for the tradtional core banking services, such as lending, managing risk and offering payment and investment services (Famma & French 2019). Fintech developments could lead to more competition for incumbent banks from non-traditional players in an already challenging market environment, which could impact the sustainability of banks’ earnings (BCBS, 2018). The emergence of Fintech under the disintermediated bank scenario could also put pressure on banks to improve digital interfaces to better meet customer expectations. Incumbent banks may find it increasingly difficult to respond quickly and competitively to emerging technologies so as to keep control of customer relationships. The proliferation of innovative products and services may increase operational complexity and risks. Disintermediation is often associated with an increased burden on the company using the strategy. Since it removes an intermediary from the process, the company may have to dedicate more internal resources to cover the services that were previously handled elsewhere. When associated with issuing bonds, the company will have to dedicate more time and personnel to the management of the funds (The Economist 2015). In regard to wholesaling, this could include shipping products directly to consumers instead of just supplying retail outlets. In terms of investing, disintermediation puts a heavier burden on investors, as they are personally responsible for all actions and decisions. This can lead to higher levels of research being necessary on their part, as well as additional time and dedication to complete any transactions. Some investors may find these aspects more challenging, depending on the nature of their investments and personal strategy. Key risks associated with the emergence of fintech include strategic risk, operational risk, cyberrisk and compliance risk. These risks were identified for both incumbent banks and new fintech entrants into the financial industry (PwC 2016). Strategic risk has to do with the decisions and plans banks would make in reponse the emergence of fintech especially in line with organisational goals. Spurred by competitive and peer pressures, banks may seek to introduce or expand financial technology and innovation without thorough and adequate cost-benefit analysis leading to losses or decrease in profitability. The organization structure and resources may not have the skills to manage financial technology and innovation. Moreover the profitability of individual banks is put at risk by the swift transition of bank services to fintech companies; if new players are capable of applying innovations efficiently and provide customers with cheaper and more tailored services, then incumbent financial institutions could lose a considerable slice of their market share along with part of their profit margin (Sorkin 2016; Wood & Buchanen 2015). Poor financial technology planning and investment decisions can increase a financial institution’s strategic risk. Early adopters of new fintech services can establish themselves as innovators who anticipate the needs of their customers, but may do so by incurring higher costs and increased complexity in their operations (Blitz et. al 2016). Conversely, late adopters may be able to avoid the higher expense and added complexity, but do so at the risk of not meeting customer demand for additional products and services. In managing the strategic risk associated with fintech services, financial institutions could develop clearly defined fintech objectives by which the institution can evaluate the success of its fintech strategy. The emergence of financial technology and innovation is on its own accompanied with a new set of regulations which may be steep for incumbent banks to meet. The increasing interaction between banks and fintech companies through the exchange of products and services may result in a lack of transparency in the transactions processing and who holds compliance responsibilities (Kauffman et. Al 2015). Such situation could lead to an increased conduct risk for incumbent players, since they could be held liable for the fintech partners misconducts if consumers encounter losses or regulatory requirements are not reached. The surging use of big data to provide better financial services and products could lead to compliance risk concerning data privacy rules, as the fierce contention for owning the customer relationship may lead to inappropriate exploitation of personal data (Juengerkes 2016). As more parties are included in the supplying of financial services and products, ambiguities related to the accountability of the players involved could spread out, increasing the probability of operational mishaps. Therefore, financial institutions will face the challenge of monitoring and managing outsourced activities conducted by third parties. Moreover, incumbents will have to adjust their operational control processes in order to assure the safety of both the bank and its customers (Afuah and Utterback 1997). The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision defines operational risk “as the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events (Benner 2007). This definition includes legal risk, but excludes strategic and reputational risk.” The emergence of fintech is usually fueled by people risk which is incompetency or wrong posting of personnel as well as misuse of power, information technology risk which is the failure of the information technology system, the hacking of the computer network by outsiders, and the programming errors that can take place any time and can cause loss to the bank and processrelated risks which are the possibilities of errors in information processing, data transmission, data retrieval, and inaccuracy of result or output (Acker & Keller 1990). The growth of fintech heighten operational risk both on a systemic and idiosyncratic level; as the financial market players become more interdependent on an IT level, a failure of the information technologies infrastructures could easily lead to a systemic crisis. Moreover, the increasing presence of fintech companies in the banking industry results in a more complex system composed of novel actors which may have little expertise in IT risks management. As for the idiosyncratic dimension, IT systems inherited by traditional banks may not be adjustable enough, or simply obsolete with respect to the ones owned by fintech firms (Dunkley 2015). Thus, incumbents would increase their use of third parties to provide up-to-date services, which may lead to higher risks related to data protection, money laundering, cyber-crime, privacy issues and customer tutelage (Christensen 1997). Additionally, banks may have to sustain fintech partners in financial distress due to their common involvement in the supply chain of financial services. The wide adoption of technologies to ease interconnection between different players and sectors require the banking system to increase controls and innovate its regulatory system, as it may be more exposed to cyber-threats, putting to risk huge quantities of sensitive data. Such threats highlight the urgency for financial institutions, fintech companies and supervisors to update their monitoring processes and stress the importance of withstanding cyber-risk (Buchack et al 2017). Liquidity and volatility risk: Customers are facilitated in changing saving accounts for the sake of greater returns thanks to new technologies and neo-banks, which are rapidly lowering fees with the objective of enlarging their customer base. While the increased competitiveness could improve efficiency, it could also worsen customer loyalty and raise deposits’ volatility, resulting in notable liquidity risk for banks. Reference List Aaker, D. & Keller, K. (1990) Consumer Evaluations of Brand Extensions. Journal of Marketing: 27–41 Afuah A, Utterback J (1997) Responding to Structural Industry Changes: A Technological Evolution Perspective. Industrial and Corporate Change: 183–202 Benner M (2007) The incumbent discount: Stock market categories and response to radical technological change. Academy of Management Review:703–720 Blitz, D., Hanauer, M., & van Vliet, P. (2016). Five conerns with the five-factor model. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2862317 Buchack, G., Matvos, G., Piskorski, T., and Seru, A., 2017. Fintech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks. NBER Working Paper 23288. Cannon S, Summers L (2014, October 13) How Uber and the Sharing Economy Can Win Over Regulators, Harvard Business Review Chishti S, Barberis J (2016) The FinTech Book. Wiley, New York Google Scholar Christensen C (1997) The innovator's dilemma: when new technologies cause great firms to fail. Harvard Business Review Press, Boston Google Scholar Davila A, Foster G, Gupta M (2003) Venture capital financing and the growth of startup firms. Journal of Business Venturing:689–708 Davis JL, Fama EF, French KR (2000) Characteristics, Covariances, and Average Returns: 1929 to 1997. The Journal of Finance:389–406 Dunkley, E. (2015, December 8). Lending services revolution piles pressure on banks as fintech sector grows. Retrieved March 6, 2016, from Financial Times: http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/653d64b2-77ce-11e5-a95a-27d368e1ddf7.html#axzz41waAnOyv Ernst, Young (2014) Landscaping UK Fintech. Ernst and Young LLP, London Google Scholar Fama EF, French KR (1993) Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics:3–56 Fama EF, French KR (2004) The Capital Asset Pricing Model: Theory and Evidence. The Journal of Economic Perspectives:25–46 Fama EF, French KR (2015) A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics:1–22 Juengerkes BE (2016) FinTechs and Banks – Collaboration is Key. In: Chishti S, Barberis J (eds) The FinTech Book: The Financial Technology Handbook for Investors, Entrepreneurs and Visionaries. Wiley, London, pp 179–182 Google Scholar Kauffman, R., Liu, J., & Ma, D. (2015). Competition, Cooperation and Regulation: Understanding the Evolution of the Mobile Payments Technology Ecosystem. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 372–391. KPMG (2016) The Pulse of Fintech, 2015 in Review. KPMG, London Google Scholar Laven M, Bruggink D (2016) How FinTech is transforming the way money moves around the world: An interview with Mike Laven. Journal of Payments Strategy & Systems:6–12 Peters, G. W., & Panayi, E. (2015, November 18). Understanding Modern Banking Ledgers Through Blockchain Technologies: Future of Transaction Processing and Smart Contracts on the Internet of Money. Retrieved from Social Science Research Network: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2692487 PwC (2016) Blurred lines: How FinTech is shaping Financial Services. PwC, London Google Scholar Sharpe WF (1964) Capital asset prices: a theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. The Journal of Finance:425–442 Sood A, Tellis G (2009) Do Innovations Really Pay Off? Total Stock Market Returns to Innovation. Marketing Science:442–456 Sorkin, A. (2016, April 6). Fintech Firms Are Taking On the Big Banks, but Can They Win? The New York Times. The Economist. (2015a, May 9). The Fintech Revolution. The Economist. The Economist. (2015b, June 16). Why fintech won't kill banks. The Economist. Wang P, Zheng H, Chen D, Ding L (2015b) Exploring the critical factors influencing online lending intentions. Financial Innovation 1(8) Wood G, Buchanen A (2015) Advancing Egalitarianism. In: Lee Kuo D (ed) Chuen, Handbook of Digital Currency: Bitcoin, Innovation, Financial Instruments, and Big Data. Elsevier, London, pp 385–401 Google Scholar