Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society

http://journals.cambridge.org/PPR

Additional services for Proceedings

of the Prehistoric Society:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

The Invention of Words for the Idea of ‘Prehistory’.

Christopher Chippindale

Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society / Volume 54 / January 1988, pp 303 - 314

DOI: 10.1017/S0079497X00005867, Published online: 18 February 2014

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0079497X00005867

How to cite this article:

Christopher Chippindale (1988). The Invention of Words for the Idea of ‘Prehistory’. . Proceedings of the Prehistoric

Society, 54, pp 303-314 doi:10.1017/S0079497X00005867

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/PPR, IP address: 61.129.42.30 on 04 May 2015

Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 54,1988, pp. 303-314

The Invention of Words for the Idea of 'Prehistory'

By CHRISTOPHER CHIPPINDALE1

The standard recent authorities on the history of

archaeology date the invention of a specific word for

prehistory to 1833, saying that Paul Tournal of

Narbonne used the adjective prehistorique ('prehistoric' in the English translation in Heizer 1969, 91; and

in Daniel 1967, 25, following Heizer 1962) or the noun

prehistoire (Daniel 1981,48) in an article about French

bone-caves.

This is not true. The word Tournal used was antehistorique (Tournal 1833, 175), and the mistake has

arisen from working with an idiomatic translation into

English, which rendered 'ante-historique' as 'prehistoric' (Tournal [1959]) instead of the original

French. (Grayson 1983, 102., however, quotes

Tournal's original French correctly.) The earliest use of

'prehistoric' seems to be Daniel Wilson's of 1851 in

The Archaeology and Prehistoric Annals of Scotland

(1851), as the older histories of archaeology say (eg

Daniel 1950, 86 (reprinted in Daniel 1975, 86); Daniel

1962, 9), before the error about Tournal began to

circulate.

In English and in French, the easy forms for the new

concept of a time before any written history began are

the ones which add 'ante-' or 'pre-' to the word history,

by analogy with other neologisms. (They are not the

only ones: a case could also be made for 'palaeohistory', which no one seems ever to have used; for

palaeoethnology, see below.) Ante-historique and prehistoric seem to have the same intellectual parents, of

course, but we should really have a correct idea of the

exact conception and birth of the word which gives a

major part of archaeology — and our Society — its title:

mistakes in the name, the nationality and the date on the

birth certificate are not a wholly trivial matter.

Furthermore, Tournal was not the first to use antehistorique in French; 'antehistoric' was used in English

in the 1830s with much the same meaning as 'prehistoric' came to have twenty and more years later; and the

first uses in both languages came, not from scientists

influenced by the new geology and its accumulating

evidence for the antiquity of man, but from scholars of a

more literary tradition.

In this note, I set out as clear an account of the birth of

prehistorical words and their relatives in French and in

English as is offered by a reasonably thorough excavation of primary and secondary sources, and some

relevant information about cognates in other

languages, especially Danish, which have a special

aspect.

In view of the earlier confusion, I have been

particularly careful to see all original sources available

to me, and to indicate which later editions or secondary

authorities I have depended on. Ante is sometimes set

without the accent on the e, eg Tournal (1833);

hyphenation is variable in both languages, and not

always clear in a printed text, since a printer may

choose to break and hyphenate a single, otherwiseunhyphenated word like 'prehistory' if it falls at a linebreak. I look here at the substantive issue only, and do

not concern myself with accents and hyphenations or

with spellings, another minor question arising with the

prefixes palaeo/palaso/paleo- and prae/pra;/pre-.

ANTEDILUVIAN AND ANTE-/PRE-HISTORIC

Grayson (1983) succinctly identifies the special

character of Tournal's thinking, as set out in papers of

1827 to 1833 about the Bize caverns near Narbonne in

Languedoc, southern France. Paul Tournal (1805—72)

1

Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cam- was a pharmacist in Narbonne, later a founder of the

museum there and conservator of antiquities for the

bridge, Cambridge.

303

THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY

departement of Aude. His early papers (1827; 1828;

1829) explored whether there was evidence for antediluvian human occupation of the caves, using the same

distinction between ante- and post-diluvian events in

relation to the biblical Deluge as was attempted by, for

example, MacEnery in his work at Kent's Cavern,

Torquay, between 1825 and 1829 (Vivian 1859).

Grayson describes this pattern of thinking in geological

and archaeological research in early nineteenth-century

Britain (1983, 55-86) and continental Europe (1983,

87—138). In a paper of 1830, Tournal showed that the

diluvium in the sites known to him was of a nature

which could not have resulted from a universal flood,

although he still used the term antediluvien: 'I'existence

des ossemens humains et des poteries ante-diluviennes

ne pent egalement etre contestee' (Tournal 1830, 199).

His last paper, of 1833, took the final step in escaping

from the Biblical frame of thinking, avoided antediluvien, and talked instead of a periode antehistorique.

In view of the confusion caused by the previous

translation of Tournal's paper, the relevant text is given

here in French and in its original layout.

After discussing the etymological difficulties of the

word fossile and neologisms like quasi fossile, Tournal

sets out 'la seule division que I'on pourrait adopter, et

qui a ete je crois de'ja proposee', 'the only division one

could accept, one which I believe has already been put

forward'. I have not traced any such earlier proposal,

which may well exist in the French geological literature.

The text runs as follows:

Periode geologique ancienne.

Elle renferme I'espace immense de temps qui a precede I'apparition de I'homme a la surface du globe, et pendant laquelle se sont

succedees une infinite de generations.

Periode geologique moderne ou periode autropaiienne caracterisee par la presence de I'homme. Cette periode peut-etre

divisee en

Periode historique.

Periode ante-historique

Elle a commence avec I'apparition de I'homme a la surface

du globe, et s'etend jusqu'au commencement des traditions

les plus anciennes. 11 est probable que pendant cette periode

la mer a ete elevee de 150 pieds au-dessus de son niveau

actuel. M. Reboul doit publier a ce sujet un travail fort

important qui levera bien des doutes et fixera beaucoup

d'irresolutions.

Elle ne remonte guere au-deld de sept mille ans, c'est-d-dire

a I'epoque de la construction de Thebes, pendant la iye

dynastie egyptienne (Josephe cite mois par mois et jour par

jour les rois de cette dynastie).

Cette periode pourra reculer davantage par suite des

nouvelles observations historiques.

Cette division offre comme on le voit I'avantage de n'etre basee que sur des observations positives, et d'ecarter la solution de la

question relative a la limite des fossiles, question qui, comme je Vai deja dit, ne me semble pas pouvoir etre resolue dans I'etat

actuel de la science.

This can be translated as follows, in the same format:

Early geological period

This embraces the enormous tract of time which came before the appearance of man on the earth's surface, and during which an

infinity of generations followed one another.

The recent geological period, or 'autropaeian' period, [is] characterized by man's presence. This period could be divided into:

ante-historic period

historic period

This began with the appearance of man on the surface of the

earth, and went on until the beginning of the earliest

traditions. It is probable that during this period the sea-level

rose T 50 feet above its present height. M. Reboul is to

publish a major work on this subject, which will remove

many doubts and resolve much uncertainty.

This goes back barely more than 7000 years, that is to say, as

far as the period of the building of Thebes during the 19th

Egyptian dynasty (Joseph cites the kings of this dynasty

month by month and day by day). This period could be

pushed further back after fresh historical observations.

As one can see, this division offers the advantage of being based only on positive observations, and of setting aside the

resolution of the question relating to the limit of fossils — a question which, as I have already said, does not seem able to be

resolved in the present state of the science.

304

15. C. Chippindale.

INVENTION OF WORDS FOR THE IDEA OF 'PREHISTORY'

The M. Reboul mentioned is surely Henri Reboul,

author of Ge'ologie de la Periode Quaternaire, et

Introduction a I'Histoire Ancienne (1833) and Essaide

Geologie Descriptive et Historique: Prolegomenes et

Periode Primaire (1835).

Tournal's scheme precisely defines an ante-historical

period extending from the first appearance of man on

the globe to the time about 7000 years ago when

written historical records begin. It is the clearest early

statement of the existence of such a period in the

science-directed literature, and quite startlingly similar

in its logic and structure to the classic treatises of some

thirty years later, such as Lyell's Geological Evidences

of the Antiquity of Man (1863). The 'idea of prehistory', as Daniel's book of that name underlines, was

not a single invention, but an idea, variously formulated and usually vague, in which one element, the idea

of some primeval age of stone before those of metal,

goes right back to Greek philosophers and historians

(Daniel 1967,90).

Tournal's vital leap, as Grayson (1983, 102—03)

underlines, was to break the habit of relating ancient

cave deposits of 'diluvium' to the specifics of a biblical

flood, and to begin to deal with an ante-historic rather

than an antediluvian period. This conceptual change

from antediluvian to ante-/ pre-historic is so important

that it is useful first to set out the history of

antediluvian words in English and in French.

The implications are not always plain, since a

reference in the early literature to the evidence of a

flood and the characteristic deposits it leaves behind

need not imply that this is the Flood of Genesis. And

events in France and Britain took different paths. The

attempt to reconcile geological events with the Floodnarrative of Scripture, which had ceased to be of much

consequence in European circles by the first years of

the nineteenth century, continued as an active concern

in England for many years — and Jameson's English

traditions of Cuvier's work were edited to force them

into a Flood way of thinking (Rudwick 1972., no—11,

133-34; Gillespiei95i).

ANTEDILUVIAN AND RELATED TERMS IN

ENGLISH AND FRENCH

In English, 'antediluvian' is first known to have been

used in 1646 by Sir Thomas Browne (1605—82), the

writer and antiquarian collector of rarities (Piggott

1976, 106); his Hydrotaphia, Urn Burial of 1658, is a

meditation on the transitoriness of life inspired by

a discovery of — as he thought — Roman (but in

fact Saxon) cremation urns (Piggott 1976, 13). He

used antediluvian in his Pseudodoxia Epidemica: or,

Enquiries into Very Many Received Tenents and

Commonly Presumed Truths, which explored and

exploded 'those encroachments, which junior compliance and popular credulity have admitted' (Browne

1646, prefatory note 'To the reader'). One of these was

the immense ages of Methuselah and other Old

Testament patriarchs who lived out their spans by the

century. Accounting for omissions from the Biblical

account, Browne showed the text intended 'onely the

masculine line of Seth, conduceable unto the Genealogy of our Saviour, and the antediluvian Chronology'

(Browne 1646, book 7, chapter 3, 344; 1650, 294;

1658,424).

Thomas Burnet's Theory of the Earth of 1684

confirmed the use of the word as an adjective, as

distinguishing the 'Ante-Diluvian' and 'Post-Diluvian'

fathers, following a similar usage by Thomas Lawson:

'The Ante-Diluvian and Post-Diluvian patriarchs, that

is, the Fathers that lived before and after the Flood'

(Lawson 1680, 9). Burnet (1684, 220) extended its use

to a noun for the men of antediluvian times: 'the

Scripture-History of the long lives of the Antediluvians'.

'Diluvian' is a little later, first recorded in John

Evelyn's diary entry for 28 August 1655: 'From the

calculation of coincidence with the diluvian period' (de

Beer 1955); and so is the alternative of diluvial, listed

in a dictionary of 1656 (Blount 1656). Curiously, its

twin of antediluvial was not invented until William

Buckland's Reliquiae Diluvianiae (Buckland, 1823, 2).

The equivalent words in French are a century later,

with antediluvien preceding diluvien in the same

manner as it does in English. The first certain use of

antediluvien is in a French dictionary of 1750 (Prevost

1750, 299), and it is thought to have been borrowed

from the English (Embs 1974, 104). Browne's Pseudodoxia was published in two French editions in 1733

(Souchay 1733; Keynes 1924,61-64); diluvien appears

in 1781 (Barruel 1781, tome 1, lettre 18). Golin's

history of the French language records of diluvien

'1787. F-Ac. 1798' (Golin 1903, 276).

In both languages, the major use of ante- and

post-diluvian was in terms of Biblical chronology,

though the terms gathered a wider meaning of primitive

backwardness, whether threatening or quaint, as in

Victor Hugo's Notre-Dame de Paris: 'II y avait dans ce

mariage a la couche cassee quelque chose de naif et

305

THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY

d'antediluvien qui me plaisait' (1832, 123). With the mid-seventeenth century. Both were available as a way

growth of geological knowledge, the terms increasingly of expressing 'ante-historical' ideas, when the new

came into use in technical senses: Barruel's, the first use geology brought their possibilities to light towards the

of diluvien in French, for example, is a questioning of end of the eighteenth century.

whether shells from low-lying water could have been

Pre-adamitic — which embodies the theologically

carried up to mountain summits, where they are now more radical proposal — was invented, as has just been

found, by the action of I'eaux diluviennes: 'On nous a noted, for hypothetical arguments about the early

objecte que les coquillages, vivant pour la plupart a la peopling of the world, but these were in the narrow

mime place que les a vu naitre, seroient restes sur tradition of theological theory. So the substantive

I'ancien rivage, tandis que I'eaux diluviennes s'elevoientdebate about an existence for early man was conducted

au sommet des montagnes' (Barruel 1812., 183). It was almost exclusively during the early years of the

this aspect of the diluvial idea, of course, which nineteenth century, in the frame of diluvial words,

crumbled under the evidence of Tournal's cave sedi- surely because the empirical evidence was often

ments.

material in, or related to, sediments with clear signs of

water action; the pressing issue, as the quotation above

from Barruel indicates, was what manner of flood or

PRE-ADAMITIC AND RELATED TERMS IN ENGLISH

floods had brought them about, and the impossibility of

AND FRENCH

a single, rather recent biblical deluge as universal

Another word, and concept, of early biblical chronol- explanation. From a first use in 1817 onwards (Keating

ogy must also be mentioned, that of 'pre- Adamitic' men 1817, vol. 1, 85), 'diluvial' was particularly applied to

— the predecessors of Adam. Theologically, pre- the theory that geological phenomena were to be

Adamitic was a much more radical proposition than explained by the universal deluge, or by periods of

antediluvian since it contradicted the Creation story by catastrophic action by water — a variant of the specific

its own inconsistency. After the Fall, for example, Deluge of Noah which was beginning to reflect the

Adam and Eve are clothed with coats of skins (Genesis variety of proofs the new geology was bringing to light.

4:21), a fact which indicates that needles existed in

Eden, and — necessarily — that there existed at some

earlier time needle-makers. The Pre-Adamites were

named in Isaac de la Peyrere's original Latin treatise of LATER USES OF DILUVIAN, CELTIC AND PRE-ADAMITIC

WORDS WITH CHRONOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS

1655 (de la Peyrere 1655), and came into English in its

translation of the following year (de la Peyrere 1656), A particular and striking context for antediluvian

which sets out a theory of a two-stage peopling of the words later in the nineteenth century is in the distinction

earth, the pre-Adamitic gentiles, and the later, Adamitic between antediluvian antiquities and Celtic antiquities

Jews and cognate races. The concept goes back into the (Chippindale 1985), as these are used, for example, in

previous century, for Thomas Nashe (d. 1601) refers to the title of Boucher de Perthes's Memoire sur I'lndustrie

'mathematicians abroad who will prove men before Primitive et les Arts a leur Origine whose first volume,

Adam' (Judith Rodden, pers. comm.). There were some Antiquites Celtiques et Antediluviennes appeared in

attempts in the eighteenth century to distinguish pre- 1847. In this distinction, Celtic meant the antiquities of

Adamitic and Adamitic races in relation to the known a seemingly recent time, the sepultures celtiques

ethnography of the world: James Adair, for example, in (Boucher de Perthes 1847, 'Avant-propos de l'editeur',

1775 (Adair 1775, 11) dismisses 'the wild notion that p. i) and especially the megalithic monuments which

some have espoused of the North American Indians were the 'Celtic, or Druidic monuments of the world'

being Prae-Adamites, or a separate race of men'. Other (Britton 1849, 7). These less old things, clearly

pre-adamitic works followed (eg Harris 1846), and a belonging with the Celts of earliest European history,

professor of geology at the University of Michigan were to be contrasted with the rude stone implements

wrote a pre-adamitic geology as late as 1880 titled Pre- from the 'terrains diluviens1 (Boucher de Perthes 1847,

Adamites: or a Demonstration of the Existence of Men i). The Revue Celtique, which had these matters as one

Before Adam ... (Winchell 1880).

of its concerns, was founded as late as 1870.

A different and later use of 'pre-adamitic' must also

So both antediluvian and pre-adamitic were in the

vocabulary from almost exactly the same years, in the be noted. Once the great antiquity of geological time

306

15. C. Chippindale. INVENTION OF WORDS FOR THE IDEA OF 'PREHISTORY'

had been accepted, and the comparatively late appearance of human fossils and artefacts within that

geological sequence, it became useful to have separate

words for the first and longer period of geological time

which lacked a human element, and for the second and

shorter period when there was a human existence. The

first of these was made 'pre-adamitic' or 'pre-adamite'

(eg 'terrestrial giants of the pre-Adamite earth'

(Richardson 1851)), as distinct from the second

which was 'pre-historic', and that again as distinct from

the third historic period of written record. Cataloguing

the collections of the Royal Irish Academy in the 1850s,

William Wilde divided the zoological items between

'Unmanufactured animal remains' and 'Antiquities of

animal materials', explaining in the introduction to the

latter section, 'With those animals that may be

considered pre-Adamite, we do not profess to deal, —

they belong rather to the province of the geologist and

palaeontologist than to that of the antiquary' (Wilde

[ 1860-61 ], 2.47-48)• Addressing the Geological Society

of London as its president in 1860, John Phillips set out

the pre-adamitic/prehistoric/historic scheme plainly.

After describing a section which ran from Oxford clay

up through strata with Elephas primigenius to old

British pottery and, at the top, the very soil where King

Charles I had walked, he remarked: 'What a succession

of periods is here offered to the mind in one opening 16

feet in depth! What errors might not be perpetrated in

our books by a mere indiscriminate gathering of the

spoils of one pit — spoils of historic, pre-historic,

and pre-Adamitic time, always truly distinguished

by Nature, though confused by heedless collectors'

(Phillips i860).

'Pre-adamitic' did not establish itself in this sense,

leaving no distinct word in the modern English

language for the geological eras preceding any human

existence — a lack which has made possible all those

cartoons of brontosauri and cave-men running around

together in an undistinguished prehistoric age.

ANTE-HISTORIQUE IN FRENCH AND ENGLISH

The first use of the French ante-historique in the

archaeological literature is due to Tournal (1833); the

context makes absolutely plain his conceiving of a

prehistory of human people in a geological era. So far as

I have been able to judge, the coining was not taken up

in the scientific literature.

But it was not only geologists who had cause to think

of a period beyond the reach of written sources. An

earlier use of ante-historique is due to M. Guizot,

professor of history in Paris, whose lecture-course on

the history of European civilization from Rome to the

Revolution was published in 1828. His history is a

largely chauvinist affair, intended to prove, 7/ nest

presque aucune grande idee, aucun grand principe de

civilisation qui, pour se re'pandre partout, n'ait passe

d'abord par la France' (Guizot 1828, lec,on 1, 5).

Talking of caste struggles between warriors and priests

as a persistent feature of early Egyptian and Etruscan

civilizations, Guizot looks to a yet earlier background,

saying, 'Mais c'est a des e'poques ante-historiques que se

sont passes, en general, de telles luttes; il n'en est reste

qu'un vague souvenir' (Guizot 1828, lec,on 2, 4; 1837,

33). The context required no confrontation between the

facts of geology and of scripture, but the meaning of his

word is exactly that of prehistorique, as is shown by the

correctness of the sense if prehistorique is substituted

for it. (The English edition of 1837 avoids a direct

translation, and renders the section as, 'These struggles,

however, mostly took place in periods beyond the reach

of history, and no evidence is left of them beyond a

vague tradition' (Guizot 1837, 33)).

Antehistorique came into general use as a rare but

respectable French word of non-technical meaning (eg

Fromentin 1857, 59), and occurs, for example, twice in

Proust's A la Recherche du Temps Perdu (1920; 1922).

The first English use of an antehistorical word is in

H. N. Coleridge's textbook of classical Greek

poetry, published in 18 3 4. Discussing whether Homer's

epics could have been composed by memory alone,

or required the use of writing, Coleridge remarks:

'According to the apparent inclination of Herodotus,

the earliest authority for the common opinion, the

Greeks had no written forms of letters before the arrival

of the Phoenician Cadmus. This specific event, as well as

the existence of Cadmus himself, is involved in the same

thick mist of ante-historic antiquity, which conceals or

disguises almost every thing or person, Greek or

concerning Greece, antecedently to the Homeric era'

(Coleridge 1834, 99—100). (This passage was added

after the first edition (Coleridge, 1830).) Again the

context requires no confronting of biblical and scientific

authority, but the sense is exactly that of prehistoric.

Much the same use at much the same time is: 'It is only

lately that the darkness, which has hung over the antehistorical period of these two universal nations, has

been penetrated' (Winning 1838, 74).

Another fairly early use is due to the philologist

Frederic Farrar (i860). Discussing puzzling languages

307

THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY

like Berber which present grammars proper to one

language family and vocabulary proper to another,

Farrar remarked, 'Perhaps the only way to account for

these strange appearances is to suppose that language

had a period of primitive fusibility, during which they

were susceptible of great modification from contact

with other languages also in an ante-historical and

embryonary state' (i860, 213-14).

The idea of a period before written history, and the

coining of a word for it, arose, as these French and

English examples show, in four quite different disciplines:

or bronze', and 'teutonic or iron'. It is curious,

nevertheless, that he uses 'prehistoric' as an adjective to

go with the noun 'annals'; annals, by the OED

definition, are 'a narrative of events written year by

year', which is exactly what prehistory would not

directly offer.

The word's use in the title of John Lubbock's

successful general book, Pre-historic Times of 1865,

sometimes taken as the benchmark, follows at least one

other use, in the title and text of Wilson's own general

book, Prehistoric Man of 1862, for example 'prehistoric researches are slow to commend themselves to the

conservative Briton' (1862., 5). By then, of course, the

a. in geological studies by the evidence of bones and struggle over the antiquity of man had been resolved,

stones in early strata;

and the word prehistoric had its unambiguous modern

b. in historical studies by the evidence of early social meaning. Derivatives followed.

structures;

First, came 'prehistorical' with the same meaning as

prehistoric in 1862: 'From a "prehistorical" period

c. in literature by the evidence of early texts;

d. in philosophy by the evidence of common elements down to the Conquest of Tamerlane' in the Parthenon

(26 July 1862, 393) and then in Lyell's Antiquity of

across divers language groups.

Man the following year (1863).

Then, came 'prehistory' in Tylor's Primitive Culture

In each field there is an early invention of an

antehistorical word, each independent so far as one can of 1871, as in the phrase 'history and pre-history of

judge from context and the absence of direct or indirect man' (1871, vol. 2,401). Later, the alternative name for

the subject appeared, 'prehistorics', as in 'Chinese

reference from onefieldto another.

In 1951, Christopher Hawkes attempted a new order prehistorics have not as yet been sufficiently studied'

for that difficult period on the edge of historic sources (Science, 4 July 1884, 212), and parallel to the noun

which the French call protohistoire; the first of his five economics from the adjective economic.

periods was termed an antehistoric period, meaning

Finally, 'prehistorian' in 1892: 'the new school of

'before all history' (Hawkes 1951). This re-creation of prehistorians' in American Catholic Quarterly Review

the idea of antehistory was not taken up.

(October 1892, 728). Where antediluvian meant the

people of antediluvian times, prehistorian was applied

to the modern people who study prehistory — an

PRE-HISTORIC IN ENGLISH AND FRENCH

unfortunate diversion which leaves us still with no

simple

word for a person who lived in prehistoric times.

Thefirstuse of prehistoric in either language really does

The French prehistorique seems to derive directly

seem to be Daniel Wilson's of 1851, as the OED and

older authorities say, in the title of The Archaeology from the English. A first use is in a French review of

and Prehistoric Annals of Scotland, and in its text (eg Lubbock's Pre-historic Times appearing in 1865, the

p. ix: 'prehistoric races of Northern Europe'). In the year of itsfirst,English publication (Tre'sor de la Langue

preface to the second edition of 1863, more simply Franqaise, unpublished archive records). It was used in

entitled Prehistoric Annals of Scotland (1863, xiv), the title of the 1867 meeting of the congress of

Wilson mentions 'the application of the term Prehis- prehistoric archaeology, the body previously named

toric — introduced, if I mistake not, for the first time in with the term palaeoethnology (see below). It is given in

this work'. His book, Wilson explains, attempted 'to Littre's dictionary of 1869 (p. 1277; the dictionary

arrange the elements of a system of Scottish Archaeo- gives no specific quotations or indications of date of first

logy, as a means towards the elucidation of prehistoric use), and the Larousseof 1875; a specific early example

annals' (1851, xxi). No formal definition or explana- quoted is in 1876 (Lecuyer 1876, 82; as cited by Littre

tion of the word is given. The book takes the 1958, 303). The word was admitted by the Academie

Scandinavian three-age system, with prehistoric eras in Franchise in 1878 (Hartzfeld and Darmesteter 1897,

Scotland that Wilson called 'primeval or stone', 'archaic 1797), a formal acceptance of a neologism which has no

308

15. C. Chippindale.

INVENTION OF WORDS FOR THE IDEA OF 'PREHISTORY'

equivalent in the less organized anglophone world. The bibliography lists the 1871 edition as being prehisr

Times may be the best substitute, and the OED has a torique also {Bibliographie nationale, 1886, 628).

use in The Times of 3 October 1888, p. 8, column i,but

this is of prehistory rather than prehistoric, and may not

OTHER EQUIVALENT WORDS IN THESE

in any case be the first.

AND OTHER LANGUAGES

Prehistoire is dated to 1872 by Littre's dictionary

The

placing

of

a conventional prefix before the word

(1958), and a representative early use is a book title of

history

or

histoire

gives three possibilities: ante-history

1874, De I'Anciennete de I'Homme, Resume Populaire

and

pre-history,

as

discussed; and palaeo-history, an

de la Prehistoire (Zaborowski-Moindron 1874). Preanalogue

to

palaeontology,

whose first recorded use is

historien is also listed in the 1875 Larousse, almost

by

Charles

Lyell:

'Palaeontology

is the science which

twenty years before a recorded English use.

treats

of

fossil

remains,

both

animal

and vegetable'

De Mortillet provides, in 1883, a discussion of

(1838,

vol.

2,

281,

note)

and

to

Lubbock's

invention of

nomenclature at a usefully early date. He explains the

palaeolithic

(1865,2).!

have

not

traced

such

a coining in

early hesitation between the words antehistorique and

either

language.

pre'historique, with pre- preferred because it was ''plus

simple etplus net', while ante- had the irrelevant double

Another alternative is palaeo-ethnology, a formula

sense, lanterieur ou oppose" (de Mortillet 1883, 2). which has prevailed in Italian, where a professor of

Daniel (1962,10) makes the same point, and notes that prehistory is still professore di paletnologia and reads

Lubbock considered using the word antehistory. I have the Bulletino di Paletnologia Italiana. The programma

not myself yet been able tofindthis point in Lubbock's of the first number of this journal, founded in 1875 by

writings. De Mortillet's 1883 book, in a series of Chierici, Pigorini and Strobel, talks of preistorica and

summaries of contemporary sciences, was entitled he preistoriche, as well as paletnologia and paletnologiche

Prehistorique, turning into a noun the adjectival half of (pp. 1-2). Afirstuse in English, of 1868, is conveniently

the over-long phrase, I'archeologie prehistorique: but it in a paper written jointly by Pigorini and Lubbock,

was la prehistoire, which established itself in French underlining both the Italian context and its acceptabilover le prehistorique or la paleoethnologie. That this ity to the leading English prehistorian: 'students of

use of prehistorique as a noun was a deliberate use Italian paleoethnology and archaeology' (Pigorini and

rather than a slip is clear; the preceding volume in this Lubbock 1868,103). The proposal for an international

series, Bibliotheque des Sciences Contemporaines, is congress of prehistoric archaeology was first made in

entitled La Science Iiconomique, not L'Economique.

Italy at the meeting in 1865 of the Italian naturalThree examples show how 'prehistoric' became sciences society at La Spezia; it followed the Italian

the standard word, to the exclusion of alternatives. manner in adopting the French title of Congres

Wilson's first, 1851, edition of The Archaeology and pale'oethnologique for its first meeting at Neuchatel in

Prehistoric Annals of Scotland uses also the word 1866. At its second, in Paris the following year, it

'antehistorical': 'Of this comprehensive system of became the Congres International d'Anthropologie et

antehistorical research the Archaeology of Scotland d'Archeologie Prehistoriques, the title which endured in

forms the merest fractional item' (18 51, 700). The French and English forms (International Congress of

French translation of Pre-historic Times, published Prehistoric Archaeology 1869).

So far as I have been able to trace them in historical

in 1867, was entitled L'Homme Avant I'Histoire

(Lubbock 1867); in the second edition of 1876 it dictionaries and early textbooks, the broad equivalents

became L'Homme Prehistorique. The German edition of prehistory and prehistoire — prahistorisch in

of 1874 and the Italian of 1875 a r e prehistoric in their German (though the German vocabulary does not

titles from the beginning. M. E. Dupont, director of the match exactly the French or English), prehistorico in

Belgian natural-history museum, subtitled a study of Spanish, and so on — are all later.

early man Les Temps Antehistoriques en Belgique in its

first edi tion of 18 71, but immediately changed it to Les

THE DANISH CASE — 'FORHISTORISK'

Temps Prehistoriques en Belgique for the second

edition of 18 7 2, or even before. There is a copy with this One European language, Danish, offers a particular

antehistorique wording in the American Philosophical point of interest, as the language in which the three-age

Society library in Philadelphia, but the Belgian national system of prehistoric chronology was worked out and

309

THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY

that of the most progressive body of archaeological

work of the period. Although modern translations of

nineteenth-century Danish publications into English

often and confusingly use the word 'prehistoric'

(eg Klindt-Jensen 1975), there was no simple word

meaning 'prehistoric' in the early Danish archaeological

literature. A variety of words for early periods, none of

them explicitly prehistoric, is used in Scandinavian

studies of the three-age order, such as Thomsen's

Ledetraad til Nordisk 0ldkyndighed (1836, in English

1848), Nilsson's Skandinaviska Nordens Urinvdnare

(1838-43), and Worsaae's Danmarks Oldtid (1843, in

English 1849); the early English translations follow

suit, talking of 'northern' or 'primeval' antiquities. It

is only with the English translation of Nilsson's

The Primitive Inhabitants of Scandinavia, edited by

Lubbock himself and published in 1868 (from the third

edition of Skandinaviska Nordens Urinvdnare), that

'prehistoric' comes into a plentiful use in the English

text (but not in the title) of a major work of the

Scandinavian school.

In the Danish a common word is oldtid, literally 'old

times' and best expressed in English as 'antiquity'.

Oldtid is a medieval word, established in the modern

language at least by 1764 (von Aphelen 1764), and in

use by poets and literary writers as well as antiquaries.

(For a series of early uses of oldtid and its derivative

words, see Ordbog over det Danske Sprog, vol. 15

(Kobenhavn: Gyldendalske Boghandel, 1934),

cols 420—21.)

The Danish word for prehistoric, forhistorisk, has a

use as early as 1837, in a work of Danish history: ldet

ligger bag ved al Sikker Kundskab, eller langt tilbage i

den forhistoriske Tid' (Molbech 1837-38, vol. 1, 80).

Keiberg (1842-44, vol. 3, 259) has another early use.

But forhistorisk did not enter into the technical

language of archaeological scholarship for many years

and — critically — after the example of French and

English, rather than by the advances of the Scandinavian scholars. In 1873 the Swede Hans Hildbrand (who

strongly influenced the young Sophus Miiller) published De Forhistoriska Folkene i Europa [The Prehistoric Peoples of Europe] (Hildbrand 1873); he had

visited, with J. J. A. Worsaae, the archaeological

congress in Bologna in 1871, entitled the Congres

International d'Anthropologie et d'Archeologie Prehistoriques. In 1874 the Danish translation of

Lubbock's Pre-historic Times was entitled Mennesket i

den Forhistoriske Tid, subtitled with oldtid in the older

manner—Populaere Skildringer afOldtidens Kulturliv

(Lubbock 1874b). The Swedish translation of 1869 had

already been prehistoric: Menniskans Utillstdnd, el den

Forhist. Tiden Belyst gu Fomlenningarne o. Seder o.

Bruk hos Nutidens Vildar (Lubbock 1869). Sophus

Miiller and Worsaae took up the word. Miiller's first

article in Aarbeger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed og

Historie (1876) was called Bronzealderens Perioder: en

undersagelse i forhistorisk arkceologi. And during the

following years, while Miiller worked on the professionalization of archaeology in Denmark, he named the

new discipline forhistorisk ark&ologi, for example in

his reviews of archaeological literature in Nordisk

Tidskrift (Miiller 1879) and his important methodological article, Mindre Bidrag til den forhistoriske

arkceologi (Miiller 1884). And Worsaae published in

1884 his book Nordens Forhistorie efter Samtidige

Mindemcerker.

The older and newer traditions were again combined

when Sophus Miiller's Vor Oldtid of 1897 was subtitled Danmarks Forhistoriske Archaeologi. Forhistoriske is used often in its text.

The same lag appears to occur with the noun

forhistorie, used by the literary critic Georg Brandes in

1873; however, in Danish the word can be used in a

rather loose way as an equivalent of 'background of or

'the story behind', so Brandes's use may not have

anything to do with a concept of an ante-history.

This is a striking pattern in the language in which so

much that is fundamental to the ideas of prehistoric

archaeology was invented. Although Danish was ready

to accept a distinct concept of prehistory when the

example of other European languages in the end offered

one, Danish scholarship did not of itself invent the

concept in three decades following the acceptance of the

three-age system in the 1830s. An explanation of this

delay may be found in two aspects of the particular

character of material and literary sources for earliest

times in Denmark, as contrasted with those for Britain

and France.

Firstly, there is no abrupt break in the written

materials; lying beyond the scope of the Roman

authors, the written sources for Danish history fade

gradually from the secure empirical descriptions of later

medieval documents back into the mistier world of

heroes and legends recorded in the Norse sagas.

Contrast this with the sharp division in British and

Gallic history, from an unknown prehistoric world to

the clear accounts, complete with names, dates and even

maps, and in a thoroughly modern manner which are

offered by the classical historians.

310

15. C. Chippindale.

INVENTION OF WORDS FOR THE IDEA OF 'PREHISTORY'

Secondly, there were no deposits of the first stone

(palaeolithic) age known from Denmark (Sir John

Lubbock remarks on this in his editor's preface to

Nilsson, 1868), no axes from the drift, no bone caves,

no collections of bones or implements sealed under

ancient stalagmite — none of those compelling signs of

a very early human existence which pressed Tournal to

his remarkable statement of an ante-historic age and

which drove Buckland to such troubles in maintaining a

diluvial habit of thinking.

The word and concept oldtid is entirely suited to

Danish circumstances, in which recorded history drifts

gradually away into an undocumented past of no

immense antiquity. Indeed, Thomsen and Worsaae's

three-age system did not necessarily place these stages

of technological development into a prehistoric past;

rather they might be identifiable, if vaguely, within the

named tribes and peoples of earliest history (Hermansen 1934). I have emphasized above that it was the

geomorphology of the bone-caverns which forced

Tournal to state a form of chronology which pushed a

human existence beyond biblical limits; no such

compulsion existed in the north, where a three-age

system might sit alongside a short chronology of

recorded history and even form a part of it.

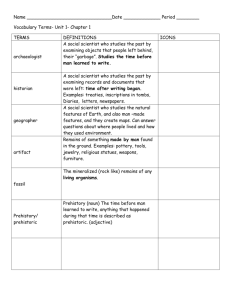

TABLE i : FIRST TRACED USES OF ANTEHISTORICAL WORDS IN

ENGLISH AND FRENCH

English

French

antediluvian

1646

before 1750

(from English)

pre-adamitic

1656 (from Latin) ?

antehistoric

1834

1818

prehistoric

•1851

*i86s

(from English)

palaeoethnology

*i868

*i866

(from Italian)

prehistory

•1871

(from Italian)

•18710^1874

(from English)

palaeolithic

•1865

•1867

(from English)

An asterisk indicates a first use in the antiquarian or

archaeological literature. (The date of 1874 for prehistory in

French is uncertain. The word appears in an 1872 dictionary,

but I have not seen an actual use before 1874 (see p. 309)).

are quite separate. A three-age system could, and did,

operate as an organizing and explanatory principle

without forcing the issue of the time-span it might

THE KEY DATES SUMMARIZED

represent.

A word is not an idea. Nevertheless, the coining of a

Although this paper revises specifics of the story, it is

word and the passing of the word into general clear that the large pattern is as Glyn Daniel saw it in his

circulation are important markers of an idea's intel- several books. Neither the three-age system, invented in

lectual progress, especially useful in the case of the Nordic region in the 1820s and 1830s, nor the

prehistory (table 1), since there exist several veiled or antiquity of man, demonstrated in France and England

plain statements, from early times in the growth of at the same time, sufficed alone to create an empirical

archaeology, of a three-age ordering or a period before prehistoric science: it was the combination of the two,

recorded or biblical history.

thirty years later and in the evolutionary fashion of the

Credit for making a word of the idea of prehistory 1860s, which constituted the invention of a real

must be shared between several authors, as the table prehistory and forced the lasting creation of a word by

indicates. Three are crucial: Guizot for the first use of an which to call it.

antehistorical word; Tournal for the first use within a

Within that intellectual context, shared by Britain

context of the antiquity of man; Wilson for the and France, one can see the words which endured

prehistoric word that finally became established.

arising in English, not just 'prehistoric' but also for

The sequence of events in Scandinavia, as shown by example, palaeolithic. This, with its corresponding

the progression of prehistoric words in Danish, points partner 'neolithic', was invented by Lubbock in Preto an aspect of the history of nineteenth-century historic Times for the period 'when men shared the

archaeology that has not been much taken note of possession of Europe with the Mammoth, the Cave

before. The new archaeology of the 1860s had two bear, and other extinct animals' (Lubbock 1865, 2);

major elements, the technological progression of the and it went into French as pale'olithique in the 1867

three-age system and the documented evidence of the translation into French (confirmed by Tresor de la

antiquity of man. They were complementary but they Langue Franqaise, unpublished entry on paleothique).

THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY

Acknowledgements. My starting-points have been the

historical dictionaries, the histories of archaeology,

and my own knowledge of some of the literature. I am

grateful to J. A. Thompson and the Oxford English

Dictionary for material from its unpublished sourcefiles, and to Anni Becquer and the Institut National de

la Langue Franchise for unpublished material prepared

for future volumes of the Tresor de la Langue

Franqaise. Judith Rodden's knowledge of pre-adamites

has been an especial help. My remarks about the Danish

depend much on the kind help of Peter Rowley-Conwy

and of Jargen Jensen of Det Humanistike Forskingscenter, Kobenhavns Universitet.

Daniel, G. E. (ed.), 1967. The Origins and Growth of

Archaeology. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Daniel, G. E., 1975. A Hundred and Fifty Years of Archaeology. London: Duckworth.

Daniel, G. E., 1981.A Short History of Archaeology. London:

Thames and Hudson,

de Beer, E. S. (ed.), 1955. The Diary ofJohn Evelyn. Oxford:

Clarendon,

de la Peyrere, I., 1655. Praeadamitae: sive exercitatio super

versibus 12-14 capitis quinti Epistolae D. Pauli ad

Romanos: quibus indicuntur primi homines ante Adamum

conditi. Amsterdam,

de la Peyrere, I., 1656. Men before Adam, or, a Discourse

upon Romans V. 11, 13, 14, by which are prov'd, that the

First Men were Created before Adam. London,

de Mortillet, G., 1883. Le Prehistorique: Antiquite de

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I'Homme. Paris: C. Reinwald.

Adair, J., 1775. The History of the American Indians. Dupont, M. E., 1871. L'Homme pendant les Ages de la Pierre

dans les Environs de Dinant-sur-Meuse: les Temps AnteLondon.

Barruel, M. Abbe, 1781. Les Helvetiennes, ou Lettres Provin- historiques en Belgique. Bruxelles: Mucquardt; Paris: J.-B.

Bailliere.

ciates Philosophiques. Paris.

Bibliographie Nationale, 1830—1880, 1886. vol. 1. Dupont, M. E., 1872. L'Homme pendant les Ages de la Pierre

Bruxelles: P. Weissenbuch.

dans les Environs de Dinant-sur-Meuse: les Temps PreBoucher de Perthes, M., 1847. Antiquites Celtiques et

historiques en Belgique 2nd edition. Bruxelles: Mucquardt;

Antediluviennes: Memoires sur Vlndustrie Primitive et les Paris: J.-B. Bailliere.

Arts a leur Origine, vol. 1. Paris: Treuttel and Wurtz.

Embs, P., 1974. Tresor de la Langue Franqaise, vol. 3. Paris:

Britton, J., 1849. The Autobiography of John Britton, F.S.A.

Editions du CNRS.

London.

Farrar, F. W., i860. An Essay on the Origin of Language,

Browne, T., 1646. Pseudodoxia Epidemica: or, Enquiries into Based on Modern Researches, and Especially on the Works

Very Many Received Tenents and Commonly Presumed

ofM. Renan. London: John Murray.

Truths. London: Edward Dod; 1650, 2nd edition, London: Fromentin, E., 1857. Un £,te dans le Sahara. 9th edn; Paris:

Dod & Ekins; 1658, 4th edition, London: Dod.

Plon, 1888.

Buckland, W., 1823. Reliquiae Diluvianiae, or, Observations Gillespie, C, 1951. Genesis and Geology: a Study in the

on the Organic Remains Contained in Caves, Fissures, and Relations of Scientific Thought, Natural Theology, and

Diluvial Gravel, and on Other Geological Phenomena,

Social Opinion in Great Britain, 1790-1850. Cambridge

Attesting the Action of a Universal Deluge. London: John

(MA): Harvard University Press.

Murray.

Golin, F., 1903. Les Transformations de la Langue Franqaise

Burnet, T., 1681. Telluris Theoria Sacra. Amsterdam.

Pendant la Deuxieme Moitie du XVIII" Siecle (17401789). Paris. (Reprinted, 1970, Geneva: Slatkine Reprints.)

Burnet, T., 1684 (Trans, of Burnet 1681). The Theory of the

Earth: Containing an Account of the Origin of the Earth, Grayson, D. K., 1983. The Establishment of Human

Antiquity. New York: Academic Press.

and of all the General Changes which it hath already

undergone, or is to undergo, till the Consummation of all Guizot, M., 1828. Moeurs d'Histoire Moderne: Histoire

Generate de la Civilisation en Europe depuis la Chute de

Things. London: Walter Kettilby.

I'Empire Romain jusqu'a la Revolution Franqaise. Paris:

Chierici, G., Pigorini, L. and Strobel, P., 1875. Programma.

Pichon and Didier.

Bullettino di Paletnologia Italiana 1,1-2.

Chippindale, C, 1985. John Britton's 'Celtic Cabinet' in Guizot, M., 1837. General History of Civilisation in Europe,

from the Fall of the Roman Empire to the French

Devizes museum and its context. Antiquaries Journal 65,

Revolution. Oxford: D. A. Talboys.

121-38.

Coleridge, H. N., 1830. Introduction to the Study of the Harris, J., 1846. The Pre-Adamitic Earth: Contributions to

Greek Classic Poets, Designed Principally for the Use of Theological Science. London.

Young Persons at School and College. London: John Hartzfeld, A. and Darmesteter, A., 1897. Dictionnaire

Generate de la Langue Franqaise du Commencement du

Murray.

XVII" Siecle a nos Jours, vol. 2. Ch. Paris: Delagrave.

Coleridge, H. N., 1834. Introduction to the Study of the

Greek Classic Poets, Designed Principally for the Use of Hawkes, C. F. C, 1951. British prehistory half-way through

the century. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 17, 1Young Persons at School and College. London: John

Murray (2nd edn).

15Daniel, G. E., 1950. A Hundred Years of Archaeology. Heizer, R. F. (ed.), 1962. Man's discovery of his Past: a

Sourcebook of Original Articles. Palo Alto: Peek.

London: Duckworth.

Daniel, G. E., 1962. The Idea of Prehistory. London: C. A. Heizer, R. F. (ed.), 1969. Man's Discovery of his Past: a

Sourcebook of Original Articles. Palo Alto: Peek (2nd edn).

Watts.

312.

15. C. Chippindale.

INVENTION OF WORDS FOR THE IDEA OF 'PREHISTORY'

and with an introduction by Sir John Lubbock.) London:

Hermansen, V., 1934. C. J. Thomsens ferste museumsordLongmans, Green.

ning; et bidrag ti tredelingens historic Aarbager for

Phillips, J., i860. Anniversary address of the President.

Nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie, 99-160.

Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 16,

Hildbrand, H., 1873. De Forhistoriska Folkene i Europe.

xxvii—lv.

Stockholm.

Piggott, S., 1976. Ruins in a Landscape. Edinburgh: EdinHugo, V., 1832. Notre Dame de Paris. Paris.

burgh University Press.

International Congress of Prehistoric Archaeology, 1869.

International Congress of Prehistoric Archaeology: origin Pigorini, L. and Lubbock, J., 1868. Notes on the hut-urns and

other objects discovered in an ancient cemetery in the

and designation of the Congress. Transactions of the third

commune of Marino (province of Rome), read to the

session which opened in Norwich on the 20th August and

Society of Antiquaries 2 April 1868. Archaeologia 42.

closed in London on the 28th August 1868. London:

Prevost, Abbe, 1750. Manuel Lexique. Paris.

Longmans, Green.

Keating, M., 1817. Travels through France and Spain to Proust, M., 1920. Le Cote de Guermantes. Paris.

Proust, M., 1922. Sodome et Gomorrhe. Paris.

Morocco 1816. London.

Keiberg, J. L., 1842—44. Intelligensblade.

Reboul, H., 1833. Geologie de la Periode Quaternaire, et

Keynes, G., 1924. A Bibliography of Sir Thomas Browne, Kt, Introduction a I'Histoire Ancienne. Paris: F.-G. Levrault.

Reboul, H., 1835. Essai de Geologie Descriptive et HistorMD. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klindt-Jensen, O., 1975. A History of Scandinavian Archaeo- ique: Prolegomenes et Periode Primaire. Paris: F.-G.

Levrault.

logy. London: Thames and Hudson.

Larousse,P., 1875. GrandDictionnaire Universel,vo\. 13. Paris. Richardson, G. F., 1851. An Introduction to Geology.

London.

Lawson, T., 1680. A Mite into the Treasury. London.

Lecuyer, L., 1876. La Philosophie Positive, janvier-fevrier. Rudwick, M. J. S., 1972. The Meaning of Fossils: Episodes in

Littre, E., 1869. Dictionnaire de la Langue Franqaise, vol. 2. the History of Palaeontology. London: Macdonald.

Souchay, J. B., 1733. Essais sur les Erreours Populaires, ou

Paris: Hachette.

Littre, E., 1958. Dictionnaire de la Langue Franqaise, vol. 6. Examen de Plusieurs Opinions Recues comme Vrayes, qui

sont Fausses ou Douteuses. Amsterdam and Paris.

Paris: Jean-Jacques Pament.

Lubbock, J., 1865. Pre-historic Times, as Illustrated by Thomsen, C. J., 1836. Ledetraad til Nordisk Oldkyndighed.

Ancient Remains and the Manners and Customs of Modern Kobenhavn.

Savages. London: Wiliams and Norgate.

Thomsen, C. J., 1848 (Thomsen 1836, trans. Earl of

Lubbock, J., 1867 (Ed. Barbier, trans.). L'Homme avant

Ellesemere). Guide to Northern Antiquities. London.

I'Histoire, etudie d'apres les Monuments et les Costumes Tournal, P., 1827. Note sur deux cavernes a ossemens,

decouvertes a Bire fsic], dans les environs de Narbonne.

Retrouves dans les Pays d'Europe. Paris: G. Bailliere; 2nd

Annales des Sciences Naturelles 12, 78—82.

edition 1876.

Lubbock, J., 1869 (C. W. Paijkull, trans.). Menniskans Tournal, P., 1828. Note sur la caverne de Bize pres Narbonne.

utillstdnd, el den forhist. tiden belystgu fomlenningarne o. Annales des Sciences Naturelles 15, 348—51.

seder o. bruk hos nutidens vildar. Stockholm: Bonnier.

Tournal, P., 1829. Considerations theoriques sur les cavernes

Lubbock, J. 1874a (A. Passow, trans.). Die vorgeschichtliche a ossemens de Bize, pres Narbonne (Aude), et sur les

ossemens humains confondus avec des restes d'animaux

Zeit.jena.

appartenant a des especes perdues. Annales des Sciences

Lubbock, J. 1874b (F. Winkel Horn, trans.). Mennesket i den

Naturelles 18, 242-58.

Forhistoriske Tid. Kobenhavn.

Lubbock, J., 1875 (M. Lessona, trans.). / Tempi Preistorici e Tournal, P., 1830. Observations sur les ossemens humains et

I'Origine dell' Incivilimento. Torino.

les objets de fabrication humaine confondus avec des

Lyell, C, 1838. The Elements of Geology. London: John

ossemens de mammiferes appartenant a des especes

Murray.

perdues. Bulletin de la Socie'te Ge'ologique de France 1.

Lyell, C , 1863. The Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Tournal, P., 18 3 3. Considerations generates sur le phenomene

Man with Remarks on the Origin of Species by Variation. des cavernes a ossemens. Annales de Chimie et de Physique

London: John Murray.

52, 161-81.

Molbech, C , 1837—38. Fortaellinger og Skildringer af den Tournal, P. [incorrectly given as M.], [1959I (ed. and trans,

Danske Historie. Kabenhavn.

by A. B. Elsasser from Tournal 1833). General consideraMiiller, S., 1879. Nordens forhistoriske arkjeologi i 1878.

tions on the phenomenon of bone caverns. Kroeber

Anthropological Society Papers 2.1, 6-16.

Nordisk Tidskrift.

Miiller, S., 1884. Mindre Bidrag til den for historiske Tylor, E. B., 1871. Primitive Culture: Researches into

the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion,

arkseologi. Aarbager for Nordisk Oldkyndighed og

Language, Art and Custom. London: John Murray.

Historie.

Miiller, S., 1897. Vor oldtid: Danmarks Forhistoriske Vivian, E. (ed.), 1859. Cavern Researches, or, Discoveries of

Organic Remains, and of British and Roman Reliques, in

Archaeologi. Kobenhavn: Nordiske Forlag.

the Caves of Kent's Hole, Anstis Cave, Chudleigh, and

Nilsson, S., 1838—43. Skandinaviska Nordens Urinvdnare.

Berry Head: by the late Rev. J. MacEnery, F.G.S. London:

Stockholm.

Simpkin, Marshall.

Nilsson, S., 1868 (trans, from the third edition of Nilsson

1838-43). The Primitive Inhabitants of Scandinavia. (Ed. von Aphelen, H., 1764. Kgl. Danske Ord-Bog. Kobenhavn.

3*3

THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY

Wilde, W. R., 1860-61 (1st edn, 1855). ^ Descriptive

Catalogue of the Antiquities in the Museum of the Royal

Irish Academy. Dublin: Hodges, Smith.

Wilson, D., 18 51. The Archaeology and Prehistoric Annals of

Scotland. Edinburgh: Sutherland and Knox.

Wilson, D., 1862. Prehistoric Man: Researches into the

Origin of Civilisation in the Old and the New World.

Cambridge: Macmillan.

Wilson, D., 1863. Prehistoric Annals of Scotland. London:

Macmillan.

Winchell, A., 1880. Pre- Adamites: or a Demonstration of the

Existence of Men before Adam ... Chicago: S. Griggs.

Winning, W. B., 1838. Manual of Comparative Philology.

London.

Worsaae, J. J. A., 1843. Danmarks Oldtid Oplyst ved

Oldsager og Gravheye. Kebenhavn.

Worsaae, J. J. A., 1849. (trans, of Worsaae 1843). The

Primeval Antiquities of Denmark. London.

Worsaae, J. J. A., 1884. Nordens Forhistorie efter Samtidige

Mindemcerker. Kobenhavn.

Zaborowski-Moindron, W., 1874. De I'Anciennete de

I'Homme, Resume Populaire de la Prehistoire. Paris.