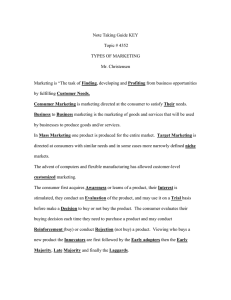

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/1355-5855.htm APJML 32,1 188 The effects of personality, culture and store stimuli on impulsive buying behavior Evidence from emerging market of Pakistan Miao Miao Received 19 September 2018 Revised 3 January 2019 15 April 2019 15 May 2019 Accepted 20 May 2019 School of Economics and Management, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China Tariq Jalees and Sahar Qabool College of Management Sciences, Karachi Institute of Economics and Technology, Karachi, Pakistan, and Syed Imran Zaman School of Economics and Management, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China and Department of Business Administration, Jinnah University for Women, Karachi, Pakistan Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to examine the relationship between personality factors (i.e. neuroticism, agreeableness, extroversion, conscientiousness and openness), cultural factors (individualism and collectivism) and store stimuli (window display and sales promotion) on impulsive buying behavior. Design/methodology/approach – The sample size for the study was 350 with a response rate of 96 percent. The questionnaire was adapted from the established scale and measures. SmartPLS was used for statistical analysis. After reliability and validity analysis, the structural model was tested, and it fitted very well. Findings – Of the nine hypotheses, five were accepted, and the other four were rejected. The results suggest that neuroticism, openness, individualism, collectivism and sales promotion significantly affect impulsive buying behavior. Marketers can use these results in developing appropriate marketing strategies. Research limitations/implications – Implications for managers were drawn from the results. In this study, only two cultural factors were considered. Future studies could use all the cultural factors in their model. Additionally, the developed model can be extended for comparative studies. Originality/value – Impulsive buying behavior, on the one hand, is problematic for consumers, but, on the other hand, is used as a tool by retailers for increasing sales. Comparatively, this study examined the effects of personality factors, cultural factors and store stimuli on impulsive buying behavior. These three factors have rarely been used together in one study. Keywords Collectivism, Agreeableness, Extroversion, Sales promotion, Neuroticism, Conscientiousness, Individualism, Impulsive buying behaviour, Store stimuli, Window displays Paper type Research paper Introduction Impulsive buying is seen as problematic from the consumers’ perspective, but from a retailer’s perspective, it is an imperative strategy for increasing sales volume (Xiao and Nicholson, 2011; Akram et al., 2018). In view of its significance, researchers have been Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics Vol. 32 No. 1, 2020 pp. 188-204 © Emerald Publishing Limited 1355-5855 DOI 10.1108/APJML-09-2018-0377 This study was supported by grants of National Natural Science Foundation (71572156), Sichuan Wine Development Research Center (CJZB18-02), Sichuan Circular Economy Research Center (XHJJ-1815), and the Humanity and Social Science Youth foundation of Ministry of Education of China (19YJC630060, 19YJC860033), Southwest Jiao Tong University “One Belt and One Road” research task project (268YDYLZ01). examining impulsive buying behavior for decades from different perspectives (Xiao and Nicholson, 2011). Past studies show that 39 percent of the total sales at department stores depend on impulsive buying. Additionally, they have found that 80 percent of consumers buy on impulse at least occasionally (Lin and Chuang, 2005). Grocery shopping has become a recreational activity for families all over the world. Families also spend more time in the pleasant environment of department stores, where they are exposed to different stimuli that encourage impulsive buying behavior (Lee and Kacen, 2008). Impulsive buying is a complicated process, and it is consistent with rational-choice models of traditional economics due to which researchers interest in impulsive buying behavior has not decreased (Amos et al., 2014; Xiao and Nicholson, 2011). Moreover, it has been documented that consumers’ recreational spending has declined while impulsive buying is still growing, even though their disposable income is not (Gültekin and Özer, 2012; Pradhan et al., 2018). It has also been argued that consumers’ buying behavior is inconsistent, varying from one product category to another (Xiao and Nicholson, 2011). For example, studies have found that many consumers, while searching for an inexpensive product such as a pen, look for the cheapest options. At the same time, consumers buying a product of higher value, such as apparel, do not make an extra effort to search for cheaper options (Amos et al., 2014). Researchers have examined impulsive buying from different perspectives for decades, and inconsistencies remain in understanding this concept. Retail outlets the world over are anxious to attract customers by using external and internal stimuli to create differentiation and value proposition. About 70 percent of sales in retail outlets depend on impulsive buying, so retailers make their internal and external ambiance attractive to motivate consumers to stay on their premises for an extended period, thus stimulating impulsive behavior (Amos et al., 2014). Based on a historical review of the literature (discussed in a subsequent section), it appears that most of the recent studies have not examined the effect of personality on impulsive buying behavior (Hendrawan and Nugroho, 2018; Sofi, 2018). A few researchers have examined the association between culture and impulsive buying behavior. Moreover, some researchers have examined the effect of store stimuli on impulsive buying behavior (Thomas et al., 2018; Boonchoo and Thoumrungroje, 2017; Merugu and Vaddadi, 2017). But it appears that none of the earlier studies have used all three factors – personality, culture and store stimuli – in one impulsive buying behavior study. In view of its significance, this study aims to examine the relationship of personality factors (neuroticism, agreeableness, extroversion, conscientiousness and openness), cultural factors (individualism and collectivism) and store stimuli (window display and sales promotion) on impulsive buying behavior. Literature review Impulsive buying is not a new phenomenon. It has been extensively researched for decades. However, there are many inconsistencies in its conceptualization. The literature in the early 1950s shows that the association between impulsive buying varies from one product category to another. Therefore, the bulk of the research in that era focused on examining the relationship between different product categories and impulsive buying behavior (Clover, 1950; Singh and Nayak, 2016). This trend continued for a decade. Then, in the early 1960s, the concept of differentiating planned impulsive buying and unplanned, impulsive buying was introduced. It was also documented in this era that some product categories stimulate planned impulsive behavior, while others stimulate unplanned impulsive behavior (Stern, 1962). In that era, most of the studies examined the association between demographic characteristics and impulsive buying behavior (Kollat and Willett, 1967), a research trend that continued for another ten years. In the early 1980s, many studies examined the five critical elements of impulsive buying: “desire to act, a state of psychological disequilibrium, the onset of psychological conflict and Impulsive buying behavior 189 APJML 32,1 190 struggle, a reduction in cognitive evaluation, and a lack of regard for the consequences of impulsive buying” (Rook, 1987, p. 190). Rook and Hoch (1985) suggested that a pleasant environment in a retail outlet stimulates positive moods, which entice consumers to buy on impulse. Thus, the academicians in this era extended the concept by adding “consumer compulsion,” which was synonymous with lifestyle traits that include “materialism,” “sensational seeking” and “variety” seeking (Rook, 1987). Additionally, the researchers in this period examined four aspects of impulsive buying which are “unplanned, decided on the spot, result from a reaction to stimulus, and cognitive reaction or emotional reaction” (Piron et al., 1991; Ozen and Engizek, 2014). In the late 1990s, many researchers suggested that certain personality traits and impulsiveness have a positive association. It was also documented that impulsive buying is a complex process in which consumers make an immediate purchase decision without considering the consequences (Rook and Fisher, 1995; Imran et al, 2018). Additionally, Beatty and Ferrell (1998) added that impulsive consumers make purchases quickly even though they originally had no intention of buying them. In early 2000, many researchers examined the association between culture and feelings on impulsive buying behavior (Youn and Faber, 2000), and many also examined the effect of personality traits on impulsive buying behavior (Farid and Ali, 2018; Cakanlar and Nguyen, 2019). In early and late 2000, researchers also examined the relationship between store internal/external stimuli and impulsive buying behavior (Crawford and Melewar, 2003). Based on a historical review of the literature, it appears that most of the recent studies have not examined the effect of personality on impulsive buying behavior (Farid and Ali, 2018; Hendrawan and Nugroho, 2018; Sofi, 2018); examined the association between culture and impulsive buying behavior (Cakanlar and Nguyen, 2019; Ali and Sudan, 2018); and examined the effect of store stimuli on impulsive buying behavior (Thomas et al., 2018; Boonchoo and Thoumrungroje, 2017; Merugu and Vaddadi, 2017). Because personality factors, cultural factors and store stimuli are highly interrelated, examining their association separately and independently with buying behavior will not help in understanding this complex concept. Consequently, this study examined the relationship between personality factors (i.e. neuroticism, agreeableness, extroversion, conscientiousness and openness), cultural factors (i.e. individualism and collectivism) and store stimuli (i.e. window display and sales promotion) on impulsive buying behavior. Conceptual framework A conceptual framework is presented in Figure 1. The discussions on the literature support for the developed hypotheses are presented in the following sections. Personality traits In this study, five personality traits and their association with impulsive buying behavior are examined and discussed in the following sections. Neuroticism and impulsive buying behavior. Neuroticism, also known as emotional instability, refers to the adverse effects of sadness, depression, and anxiety (Schiffman and Kanuk, 2008). The literature suggests that highly unstable people are emotionally stressed and vulnerable to insecurity (Shahjehan et al., 2012). All healthy individuals possess some neurotic traits, as they help in absorbing the damaging effects of embarrassment, humiliation, stress and anxiety. However, individuals with a high neuroticism score possess negative emotions and are short-tempered and overstressed ( John et al., 2008). They come up with unreasonable ideas that might have negative consequences, while, on the contrary, individuals who score low on neuroticism are emotionally stable and have a built-in capability to face and absorb damaging effects of anxiety and stress (Hough et al., 1990). Emotionally stable persons are more relaxed, so they are less vulnerable to distress and Extraversion Contentiousness Individualism Neuroticism Impulsive buying behavior 191 Collectivism Impulsive_buying_behavior Window_display Agreeableness Sales_promotion Openness impulsive behavior (McCrae and Costa, 2008). Impulsive buying behavior and emotional instability are positively correlated (Shahjehan et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2019). Individuals with a high level of emotional instability suffer from anxiety and irritability, which makes them more vulnerable to impulsive buying behavior (Silvera et al., 2008). It has been argued that highly neurotic persons have a depressive nature; they are more self-conscious and impulsive (McCrae and Costa, 2008). Past studies have concluded that neuroticism and impulsive buying behavior have a positive relationship – that neurotic individuals relive their emotional distress by indulging in impulsive buying (Shahjehan et al., 2012; Silvera et al., 2008): H1. Neuroticism has a positive association with impulsive buying behavior. Agreeableness and impulsive buying behavior. Individuals with a high level of agreeableness are socially active, maintaining positive relationships with friends and coworkers. They are more cooperative and sympathetic than neurotic persons and less antagonistic and suspicious of others (McCrae and Costa, 2008). The relationship between agreeableness and impulsive buying behavior has not been examined amply. Verplanken and Herabadi (2001) suggested that impulsive buying behavior and a high level of agreeableness are negatively associated. Based on this assumption, Badgaiyan and Verma (2014) hypothesized that agreeableness and impulsive buying behavior have a negative association. However, when they empirically tested this relationship, they found the relationship was insignificant. Agreeableness as a personality trait helps individuals to develop and maintain long-term relationships with others. Moreover, highly agreeable persons are concerned about the well-being of others, so they help others wholeheartedly and expect the same from them. These individuals are not reactive; they think before they react. In view of this trait, they are less vulnerable to impulsive buying behavior (McCrae and Costa, 2008; Verplanken and Herabadi, 2001): H2. Agreeableness has a negative association with impulsive buying behavior. Figure 1. Conceptual framework APJML 32,1 192 Extroversion and impulsive buying behavior. Extroverts are energetic and socially interactive. They are materialistic and possess positive emotions ( John and Srivastava, 1999; McCrae and Costa, 2008). Because they like to socialize, they are talkative and energized while interacting with others (Mooradian and Swan, 2006; John et al., 2008). They like their independence and are not very tolerant of interference from others ( John et al., 2008). Besides socializing with family, friends and peers, extroverts love to talk with strangers, including salespersons at retail outlets. However, individuals with a low score in this trait are not very social and are less impulsive (Eysenck et al., 1993). Extroverts are highly confident and self-dependent (Watson and Clark, 1991; John and Srivastava, 1999). The individuals scoring high on this trait love to explore new ideas and consequently have less self-control and more vulnerability to impulsive buying (Eysenck et al., 1993; Judge et al., 2014). Their sociability leads extroverts to interact and spend more time with salespersons, and, as a consequence, they are vulnerable to impulsive buying (Chen, 2011; Eysenck et al., 1993). In a contrary finding, Simons et al. (2014) found a negative association between extroverts and impulsive buying behavior: H3. Extroversion has a positive association with impulsive buying behavior. Conscientiousness and impulsive buying behavior. Conscientiousness is a built-in mechanism that is goal directed and controls impulsive behavior. The level of conscientiousness varies from one individual to another in terms of self-control, sense of responsibility and hard work (McCrae and Costa, 2008; Roberts et al., 2014). Individuals who are highly conscientiousness are well organized, goal oriented and highly responsible in carrying out their personal and official tasks (Barrick et al., 2013). These traits make them less vulnerable to impulsive buying behavior. Individuals with low level of conscientiousness are less thoughtful about their lives, are not goal oriented and get distracted easily, so are more vulnerable to impulsive buying (Roberts et al., 2014): H4. Conscientiousness has a negative association with impulsive buying behavior. Openness and impulsive buying behavior. Individuals with a high level of openness are very imaginative and have diversified interests. They do not have high expectations of others and are open to listening and adopting the viewpoints of others (McCrae and Costa, 2008). It is also reported that highly open individuals frequently explore and adopt new ideas and experiences. Consequently, they are more vulnerable to impulsive behavior (Verplanken and Herabadi, 2001). On the contrary, individuals with low levels of openness are conservative and traditionalist and less vulnerable to impulsive behavior (Verplanken and Herabadi, 2001): H5. Openness has a positive association with impulsive buying behavior. Culture Culture plays an essential role in consumer buying behavior. Since the 1960s, many studies have examined the impact of culture on impulsive buying behavior (Kacen and Lee, 2002). This study examined the effect of individualism and collectivism on impulsive buying behavior, discussed in the following sections. Individualism and impulsive buying behavior. Individualism is a social pattern in which individuals in a society are not socially and emotionally linked to family members and groups. They are more focused on emotional and physical freedom. Individualists are more concerned about networking and are goal oriented. They are not concerned about the norms and values of the society and are reluctant to sacrifice their personal social needs and goals to cultural and societal demands (Hagger et al., 2014). Individuals in an individualist culture are concerned about their social needs and preferences; therefore, they often ignore the negative consequences of impulsive buying and are more inclined to engage in impulsive buying (Kacen and Lee, 2002). Marm and Kongsompong (2007) concluded that because their peers and friends do not influence individualists, they generally have a positive attitude toward impulsive buying behavior. Mai (2003) also reported that impulsive buying and individualism are positively related. Additionally, in a comparative study, it was found that individuals in the USA (an individualist society) have a more negative attitude toward impulsive buying than Indian (collective society) individuals toward impulsive buying (Verma and Triandis, 1999): H6. Individualism has a positive association with impulsive buying behavior. Collectivism and impulsive buying Behavior. Collectivism is a social pattern in which most members of a society see themselves as a member of a close-knit family, group, or nation (Toffoli and Laroche, 2015; Jiang et al., 2018). Past studies have shown that a collectivist is more emotionally mature and therefore is less vulnerable to impulsive buying however (Thompson and Prendergast, 2015) found no significant association between collectivism and impulsive buying behavior. A study by Marm and Kongsompong (2007) found that because individuals in a collective society are influenced by their family members and peers, they are more vulnerable to buying behavior in comparison with individuals in an individualist society. Verma and Triandis (1999) concluded in a comparative study that Indians (collective society) are more vulnerable to impulsive buying behavior than are individuals in an individualist society such as the USA: H7. Collectivism has a positive association with impulsive buying behavior. Store external and internal stimuli Store external and internal stimuli visually communicate brand messages to customers. This study examined the effects of window display and sales promotion on impulsive buying behavior, discussed in the following section. Window display and impulsive buying behavior. Window display visually communicates the value proposition to the target audience and stimulates buying behavior (Chang et al., 2011). The window display is not restricted to external décor but also includes the point of sale, ambiance, merchandising and sales staff (Zhou and Wong, 2004). A pleasant window display not only attracts the customers to retail outlets but also makes them stay longer. As a consequence, they are exposed to different stimuli and resort to impulsive buying (Tendai and Crispen, 2009). Past studies have documented a positive association between window displays and consumer impulsive buying behavior (Merugu and Vaddadi, 2017; Tendai and Crispen, 2009). The association between window displays and impulsive buying behavior varies from customer to customer and from one product category to another (Badgaiyan and Verma, 2015). Prashar et al. (2015) suggest that retailers change window displays continually to stimulate impulsive buying. Gandhi et al. (2015) argue that exciting and innovative display strategies help to change the moods of the customers, making them more vulnerable to impulsive buying behavior. Past studies have documented that a display of product-related advertisement near the point of sale and that broadcasting videos about the products stimulates impulsive buying (Gandhi et al., 2015; Sun and Yazdanifard, 2015). Consumers pay more attention to an attractive, pleasant display, and, as a consequence, they become vulnerable to buying (Muruganantham and Bhakat, 2013): H8. Window displays are positively associated with impulsive buying behavior. Sales promotion and impulsive buying behavior. Sales promotion is used extensively by retailers to increase their sales and reduce inventory (Xu and Huang, 2014). A sales promotion Impulsive buying behavior 193 APJML 32,1 194 targets consumers who want to pay less than the original price. Some of the techniques commonly used in sales promotion, besides lowering prices, are a sample, a premium, a contest or a rebate (Liao et al., 2009). Sales promotion and impulsive buying behavior have a positive association (Xu and Huang, 2014). Consumers are price conscious; therefore, they prefer to purchase goods sold through sales promotions (Liao et al., 2009). Impulsive buyers, compared to others, are more vulnerable to sales promotion (Xu and Huang, 2014). Sales promotion does not have a linear effect on impulsive buying; it varies according to customers’ personality traits and the product categories (Badgaiyan and Verma, 2015). Although sales promotion helps to increase buying at retail outlets, if they are continued over an extended period, they will lose their effectiveness and may dilute the brand image (Liao et al., 2009). Many studies found a positive association between sales promotion and impulsive buying behavior (Xu and Huang, 2014). However, it has also been found that sales promotion has a direct link to desire and not to actual buying behavior (Xu and Huang, 2014): H9. Sales promotion is positively related to impulsive buying behavior. Methodology Participants and procedure The study aimed to measure the effect of five personality factors, two cultural factors and three internal store stimuli on impulsive buying behavior. The questionnaire was adapted from the earlier developed scales and measures. Five enumerators of a private business school were recruited to conduct the survey of the target audience. Initially, a pretest of the questionnaire was carried out to check the wording and flow of the questions and the social desirability, which is an important aspect in the Asian context and, if not pretested, could affect the study results. Based on the inputs received, the required corrections were made. The survey was conducted at the leading malls in Islamabad, Lahore, Karachi, Faisalabad and Quetta. The respondents were informed that the survey was for academic purposes only and that their participation was voluntary. They were allowed to discontinue responding at any time if they felt uncomfortable or had any apprehension. They were also told that the research was for academic purposes and would not be used for commercial purposes. Additionally, their real identity was not recorded. The statistical analysis is based on SmartPLS. The respondents visited the target shopping malls during the day, evenings, and weekends. The sample size was 350, with a response rate of 96 percent. The respondents were representative of people who regularly visit shopping malls. Of the 350 respondents, 55 percent were males, and 45 percent were females; 43 percent of the respondents were married, and the rest, 57 percent, were single. Their ages were between 18 and 55; 30 percent of the respondents were between 18 and 30, 35 percent from 30 to 40, and another 35 percent from 45 to 55. Most of the respondents (55 percent) had at least an intermediate (Higher Secondary) education, 45 percent had Bachelor’s degrees, and the rest, 10 percent, had Master’s degrees. Constructs Ten constructs were used in the study. Five were related to personality, two were related to culture, two were related to store stimuli and one was the dependent variable. The constructs used in the study are discussed in the following sections. Neuroticism scale Neuroticism is a state of emotional instability that leads to depression and anxiety. Highly unstable individuals are emotionally stressed and insecure (Shahjehan et al., 2012). In this study, the neuroticism scale has four items, all adapted from the scales and measures developed by Rook and Fisher (1995). Agreeableness scale. Agreeableness is a social trait allowing individuals to develop a sustainable relationship with peers, family, and others. They are more cooperative and sympathetic, rather than antagonistic toward and suspicious of others (McCrae and Costa, 2008). The agreeableness scale was adapted from the Rook and Fisher (1995) scale, and the measure has four items, all based on the five-point Likert scale. Extroversion scale. Highly extroverted individuals are incredibly energetic, socially interactive, and materialistic and possess positive emotions ( John and Srivastava, 1999; McCrae and Costa, 2008). This scale has four items, all based on the scales and measures of Rook and Fisher (1995). Conscientiousness scale. Individuals with a high level of conscientiousness are generally more responsible, are hard-working and have more self-control than others. In view of these traits, highly conscientious individuals are goal oriented (McCrae and Costa, 2008). The conscientiousness scale also has four items adapted from the scales and measures developed by Rook and Fisher (1995). Openness scale. Highly imaginative persons with an interest in diverse fields are the social traits of openness McCrae and Costa (2008). Individuals who have a high level of openness listen to other points of view and do not reject them outright even if they are contrary to their own perceptions. The scale openness in the study is based on the scale of Rook and Fisher (1995). There were four items in this part of the questionnaire, all based on a five-point Likert scale. Collectivism scale. Collectivists in a society consider themselves closely associated with their family, group and nation (Toffoli and Laroche, 2015). The collectivism scale in the study has four items adapted from Singelis et al. (1995). Individualism scale. Individualists in a society do not have a sustained emotional and social link with their family members. They enjoy their emotional and physical freedom (Hagger et al., 2014). The individualism scale in the study has four items and has been adapted from the scale and measures of Singelis et al. (1995). Sales promotion. Sales promotion is an important strategy used by retailers for increasing sales volume and depleting inventory (Xu and Huang, 2014). Customers are generally more attracted to sales promotion as they feel as if they are paying less than the actual price. Some of the techniques commonly used in sales promotion are a sample, premium and contest rebate (Liao et al., 2009). The scale sales promotion was adapted from the scales and measures of Karbasivar and Yarahmadi (2011), and it has four items. Window display. The window display is a tool used by retailers for communicating value proposition and stimulating impulsive buying behavior (Chang et al., 2011). The window display is not restricted to external décor but includes the point of sale, ambience and merchandising, and sales staff (Zhou and Wong, 2004). The window display scale in the study has four items, all adapted from Karbasivar and Yarahmadi (2011). Results Descriptive analysis Descriptive analysis was carried out to measure the internal consistency and univariate normality. The results are presented in Table I. The results show that the adapted constructs’ Cronbach’s alpha values are higher than 0.70, indicating acceptable internal consistency (Leech et al., 2014). Additionally, all skewness and kurtosis values were between ±1.5, indicating that adopted constructs fulfill the requirements of univariate normality (Looney, 1995). Moreover, the VIF values are also less than 5.0, indicating there is no issue of multicollinearity. Impulsive buying behavior 195 APJML 32,1 Convergent validity Convergent validity was ascertained through composite reliability and average variance extracted. The results are presented in Table II. The results show that all the composite reliability values are higher than 0.70, and the values of average variance extracted are higher than 0.40, confirming that the constructs fulfill the requirements of convergent validity. 196 Discriminant validity Discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) was used to examine uniqueness of the variables. The results are presented in Table III. Table I. Descriptive results Table II. Convergent validity Table III. Discriminant validity Reliability Cronbach’s α Mean SD Skewness Kurtosis VIF 0.60 0.71 0.69 0.64 0.62 0.75 0.82 0.60 0.81 0.80 4.63 4.15 5.00 4.65 4.43 4.18 4.74 3.85 3.92 4.15 1.22 1.15 0.97 1.03 1.06 0.97 1.03 1.05 1.15 1.12 −0.89 −0.87 −0.46 −0.17 −0.50 −0.89 −0.19 −0.49 −0.57 1.05 −0.78 −0.50 −0.82 −1.05 0.87 −0.89 −0.91 0.69 −0.83 −0.98 1.32 1.62 1.17 1.31 1.53 1.36 1.49 1.50 – Neuroticism Agreeableness Extroversion Conscientiousness Openness Individualism Collectivism Window displays Sales promotion Impulsive buying Composite reliability Average variance extracted 0.61 0.81 0.81 0.77 0.79 0.83 0.88 0.74 0.76 0.83 0.44 0.52 0.52 0.57 0.51 0.49 0.65 0.44 3.92 0.55 Neuroticism Agreeableness Extroversion Conscientiousness Openness Individualism Collectivism Window displays Sales promotion Impulsive buying Openness_ Agreeableness_ Collectivism_ Conscientiousness_ Extroversion_ Impulsive buying Individualism_ Neuroticism_ Window displays_ Sales promotion_ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0.71 0.34 0.19 0.10 0.33 0.31 0.37 0.20 0.29 0.29 0.72 0.35 0.18 0.35 0.26 0.33 0.20 0.21 0.31 0.81 0.16 0.38 0.13 0.41 0.24 0.21 0.33 0.68 0.21 0.15 0.24 0.28 0.29 0.19 0.72 0.30 0.47 0.30 0.39 0.44 0.75 0.31 0.32 0.35 0.33 0.70 0.23 0.29 0.31 0.67 0.34 0.18 0.65 0.46 0.66 The results show that the square root of average variance extracted values depicted diagonally are more significant than the rest of the values, which are the square of each pair of correlation. This confirms that all the constructs used in the study are unique and distinctive (Fornell and Larker, 1981). Structural model output Structural model outputs were obtained through bootstrapping of 5,000 subsamples at 95 percent and a one-tailed test. The results are presented in Table IV, and the structural model in Figure 2. H1 states that neuroticism has a positive association with impulsive buying behavior. The results support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.180, t ¼ 3.142, p ¼ 0.001o0.05). H2 states that Path coefficient t-statistics p-values 0.180 0.067 0.044 0.000 0.159 0.053 0.168 ‒0.094 0.152 3.142 1.050 0.605 0.006 2.911 0.941 2.479 1.627 2.478 0.001 0.147 0.273 0.498 0.002 0.174 0.007 0.052 0.007 Neuroticism_→impulsive buying (H1) Agreeableness_→impulsive buying (H2) Extroversion_→impulsive buying (H3) Conscientiousness_→impulsive buying (H4) Openness_→impulsive buying (H5) Individualism_→impulsive buying (H6) Collectivism_→impulsive buying (H7) Window displays_→impulsive buying (H8) Sales promotion_→impulsive buying (H9) Notes: R2 ¼ 0.26, adjusted R2 ¼ 0.23 H1 B10 B7 B8 H2 H3 H4 C2 C1 J1 7.415 8.088 10.684 13.639 16.733 Neuroticism 8.464 B9 Contentiousness Extraversion Table IV. Path coefficient C4 C3 8.393 7.460 197 Results Accepted Rejected Rejected Rejected Accepted Rejected Accepted Rejected Accepted 5.376 3.734 2.141 3.924 11.372 16.670 16.381 9.225 Impulsive buying behavior J2 J3 Individualism J5 3.142 G1 0.006 0.605 0.941 AT1 8.476 G2 G3 6.535 25.133 9.771 2.479 7.552 23.286 Collectivism 17.428 G4 L4 AT4 Impulsive buying behavior 2.911 1.627 L3 AT3 25.874 L1 L2 AT2 5.741 I1 18.488 2.478 22.862 6.885 1.050 7.397 21.531 5.087 Openness I2 I3 1.949 I4 Window display K1 K2 K3 13.287 Sales promotion 14.810 5.286 6.031 8.360 10.743 5.217 4.768 Agreeableness K4 F1 F2 F3 F4 Figure 2. Structured model APJML 32,1 198 agreeableness and impulsive buying behavior have a negative relationship. The results do not support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.067, t ¼ 1.050, p ¼ 0.147W0.05). H3 states that extroversion and impulsive buying behavior have a positive relationship. The results do not support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.044, t ¼ 0.605, p ¼ 0.273W0.05). H4 states that conscientiousness and impulsive buying behavior have a negative relationship. The results do not support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.000, t ¼ 0.006, p ¼ 0.498W0.05). H5 states that openness and impulsive buying behavior have a positive relationship. The results support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.159, t ¼ 2.911, p ¼ 0.002o0.05). H6 states that individualism has a postive association with impulsive buying behavior. The results do not support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.053, t ¼ 0.941, p ¼ 0.174W0.05). H7 states that collectivism and impulsive buying behavior have a negative association. The results support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.168, t ¼ 2.479, p ¼ 0.007o0.05). H8 states that window displays and impulsive buying behavior are positively related. The results do not support this hypothesis (β ¼ −0.094, t ¼ 1.627, p ¼ 0.052W0.05). H9 states that sales promotion and impulsive buying behavior are positively related. The results support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.152, t ¼ 2.578, p ¼ 0.007W0.05). Discussion and conclusion The results and their relevance to earlier studies are discussed in the following section. Discussion Neuroticism and impulsive buying behavior. H1 states that neuroticism has a positive association with impulsive buying behavior. The results support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.180, t ¼ 3.142, p ¼ 0.001 o 0.05). McCrae and Costa (2008) suggest that individuals who are high in a neuroticism tendency are depressive, self-confused, and impulsive, making them more vulnerable to impulsive buying. Other studies, while validating the positive association between neuroticism and impulsive buying, conclude that impulsive buying helps neurotic individuals to relieve their emotional stress (Shahjehan et al., 2012; Silvera et al., 2008). Furthermore, neuroticism traits up to a certain point are necessary, as they help in coping with stress and anxiety. However, when they surpass a certain limit, they stimulate negative emotions and stress, which leads to negative consequences, including impulsive buying ( John et al., 2008). Agreeableness and impulsive buying behavior. H2 states that agreeableness and impulsive buying behavior have a negative relationship. The results do not support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.067, t ¼ 1.050, p ¼ 0.147 W0.05). McCrae and Costa (2008) find that individuals with a high score on agreeableness have a compassionate nature and generally trust others. Moreover, they are socially active and tend to maintain a positive and sustainable relationship with their peers. Only a few studies have examined the association between agreeableness and impulsive buying. For example, Verplanken Herabadi (2001) suggest that agreeableness and impulsive buying behavior are negatively associated. On the contrary, Badgaiyan and Verma (2014) find an insignificant association between impulsive buying and agreeableness. Individuals with a high level of agreeableness have an understanding attitude toward others. Moreover, they go out of their way to help their friends and peers and expect that peers and friends will reciprocate. Furthermore, McCrae and Costa (2008) find that agreeable people are less vulnerable to impulsive buying, as they are not reactive and think rationally. Extroversion and impulsive buying behavior. H3 states that extroversion and impulsive buying behavior have a positive relationship. The results do not support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.044, t ¼ 0.605, p ¼ 0.273W0.05). Extroverted individuals are highly energetic and materialistic and have positive emotions ( John and Srivastava, 1999; McCrae and Costa, 2008). Extroverts love to socialize and interact with friends as well as with strangers, including salespersons at a retail outlet (Eysenck et al., 1993). Due to these traits, they are vulnerable to impulsive buying ( John et al., 2008). On the other hand, introverts are not very social and are less impulsive (McCrae and Costa, 2008). Furthermore, extroverts are self-confident and love to explore and experience new ideas, so they tend to be more vulnerable to impulsive buying (Eysenck et al., 1993; Judge et al., 2014). Conscientiousness and impulsive buying behavior. H4 states that conscientiousness and impulsive buying behavior have a negative relationship. The results do not support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.000, t ¼ 0.006, p ¼ 0.498W0.05). Conscientiousness is a built-in mechanism that helps individuals to monitor their level of responsiveness to surrounding stimuli. It is goal directed and varies from one individual to another – individuals do not all have the same self-control and sense of responsibility (Roberts et al., 2014). A high level of conscientiousness makes individual’s goal directed and more responsible in personal and official tasks. Consequently, their inclination toward impulsive buying is low (Barrick et al., 2013). On the contrary, low conscientiousness makes individuals less serious about life, and they get distracted, so are more vulnerable to impulsive buying (Roberts et al., 2014). Openness and impulsive buying behavior. H5 states that openness and impulsive buying behavior have a positive relationship. The results support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.159, t ¼ 2.911, p ¼ 0.002 o0.05). Individuals with a high level of openness have diversified interests, are open to new ideas, and are willing to adopt new and innovative products. They fall into the category of early adopters and are more vulnerable to impulsive buying behavior (McCrae and Costa, 2008). On the other hand, individuals who have a low level of openness are traditionalist, conservative, not open to new ideas, not willing to take a risk and have a low vulnerability to impulsive buying behavior (Verplanken and Herabadi, 2001). Thus retailers tend to target individuals who have a high level of openness. Individualism and impulsive buying behavior. H6 states that individualism has a positive association with impulsive buying behavior. The results support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.053, t ¼ 0.941, p ¼ 0.174 W0.05). Individuals in an individualist society are not socially and emotionally attached to their families and groups. They are more concerned about their physical and emotional freedom and do not follow social norms and values. Moreover, in comparison to collectivists, individualists have a low tendency to sacrifice emotional, personal, and social needs (Hagger et al., 2014). Kacen and Lee (2002) found that because individualists are more concerned about their social needs, they often ignore the negative consequences of impulsive buying and so adopt impulsive buying behavior. Similarly, Marm and Kongsompong (2007) conclude that individualists are not concerned about impressing their peers and friends with their behavior. Therefore they have no problem about adopting impulsive buying behavior. Furthermore, Mai (2003) also document that impulsive buying behavior and individualism are positively related. Moreover, Verma and Triandis (1999), in a comparative study, found that individuals in an individualist society (e.g. the USA) have a lower inclination to impulsive buying behavior than individuals in a collectivist society such as India. Collectivism and impulsive buying behavior. H7 states that collectivism and impulsive buying behavior have a positive association. The results support this hypothesis (β ¼ 0.168, t ¼ 2.479, p ¼ 0.007o0.05). In a collectivist society, individuals consider themselves close-knit members of a family, group or nation (Toffoli and Laroche, 2015). Past studies have documented that individuals in a collective society since childhood learn to sacrifice their personal and social needs to remain connected to their family. Therefore they are more mature than individuals in an individualist society. Consequently, they have a negative attitude toward impulsive buying behavior (Badgaiyan and Verma, 2015; Thompson and Prendergast, 2015). Other studies find that collectivism and impulsive buying behavior have an insignificant association (Badgaiyan and Verma, 2015; Thompson and Prendergast, 2015). On the contrary, Impulsive buying behavior 199 APJML 32,1 200 Marm and Kongsompong (2007) document that a collectivist society and impulsive buying behavior have a positive association. Window display and impulsive buying behavior. H8 states that window display and impulsive buying behavior are positively related. The results do not support this hypothesis (β ¼ −0.094, t ¼ 1.627, p ¼ 0.052W0.05). Retailers use window displays to attract customers to their premises and to create differentiation between their store and others. Moreover, window displays are also considered a strategy for communicating value proposition and stimulating impulsive buying behavior (Chang et al., 2011). Past studies have documented that window displays are not only restricted to external décor, but also include the point of sale, ambiance, merchandising, and sales staff (Zhou and Wong, 2004). Tendai and Crispen (2009) conclude that consumers prefer retail outlets with an aesthetically pleasing appearance. Consequently, customers remain longer in such outlets and buy impulsively (Tendai and Crispen, 2009). Merugu and Vaddadi (2017) and Tendai and Crispen (2009) also conclude that window displays and impulsive buying behavior are positively associated. But it has also been argued that the relationship between impulsive buying and window displays is not universal, and that it varies from customer to customer and from one product category to another (Badgaiyan and Verma, 2015). Given these varying relationships, retailers frequently change the window display to stimulate impulsive buying behavior (Prashar et al., 2015). Moreover, it has also been found that exciting and innovative window display strategies stimulate customers’ positive mood and impulsive buying behavior (Gandhi et al., 2015). Sun and Yazdanifard (2015) find that many retailers display product-related materials and advertisements near the point of sale to stimulate impulsive behavior (Gandhi et al., 2015; Sun and Yazdanifard, 2015). Similarly, Muruganantham and Bhakat (2013) also find that pleasant and attractive window displays stimulate impulsive buying behavior. Sales promotion. H9 states that sales promotion and impulsive buying behavior are positively related. The results support this hypothesis ( β ¼ 0.152, t ¼ 2.578, p ¼ 0.007 W0.05). Many retailers use a sales promotion strategy to attract consumers and deplete inventory (Xu and Huang, 2014). Sales promotion strategies are attractive to customers as they perceive that they are paying less than the original price of goods and services. Some of the techniques commonly used in sales promotion are sample, premiums and contest rebates (Liao et al., 2009). Many studies have found a positive association between sales promotion and impulsive buying behavior (Xu and Huang, 2014; Liao et al., 2009). Moreover, it has also been found that impulsive buyer justifies their behavior as having resulted in considerable savings (Liao et al., 2009). Xu and Huang (2014) also find a positive association between sales promotion and impulsive buying behavior. However, they conclude that the relationship between sales promotion and impulsive buying is not linear; it diminishes over a period of time. On the other hand, they found that sales promotion stimulates impulsive buying desire but not actual buying behavior. Conclusion Impulsive buying is a complex behavior. On the one hand, it is considered problematic for consumers, and, on the other hand, it is an essential tool for retailers to increase their sales. In view of impulsive behavior’s importance, it is important to examine the factors that influence it. Thus this study has examined the relationship between personality factors (i.e. neuroticism, agreeableness, extroversion, conscientiousness and openness), cultural factors (individualism and collectivism), and store stimuli (window displays and sales promotion) with impulsive buying behavior. The results suggest that neuroticism, openness, collectivism, and sales promotion have a positive effect on impulsive buying behavior. On the other hand, the results suggest that agreeableness, extroversion, conscientiousness, individualism and window displays have an insignificant association with impulsive buying behavior. Retailers could use the results of the study in developing strategies for increasing sales. Moreover, it could also be used by policy makers to reduce the incidence of impulsive buying, as, in the long run, it leads to compulsive buying, which is harmful to individuals and society. Future research This study has measured the association between personality factors, cultural factors and store stimuli with impulsive buying behavior. In cultural factors, only two variables, i.e. individualism and collectivism, were examined. Future studies may add other cultural variables, such as power distance, masculinity, femininity, uncertainty avoidance and demographic factors. The model in this study could be extended for comparative studies. References Akram, U., Hui, P., Kaleem Khan, M., Tanveer, Y., Mehmood, K. and Ahmad, W. (2018), “How website quality affects online impulse buying: moderating effects of sales promotion and credit card use”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 30 No. 1, pp. 235-256. Ali, S.W. and Sudan, S. (2018), “Influence of cultural factors on impulse buying tendency: a study of Indian consumers”, Vision, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 68-77. Amos, C., Holmes, G.R. and Keneson, W.C. (2014), “A meta-analysis of consumer impulse buying”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 86-97. Badgaiyan, A.J. and Verma, A. (2014), “Intrinsic factors affecting impulsive buying behaviour – evidence from India”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 537-549. Badgaiyan, A.J. and Verma, A. (2015), “Does urge to buy impulsively differ from impulsive buying behaviour? Assessing the impact of situational factors”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 145-157. Barrick, M.R., Mount, M.K. and Li, N. (2013), “The theory of purposeful work behavior: the role of personality, higher-order goals, and job characteristics”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 38 No. 1, pp. 132-153. Beatty, S.E. and Ferrell, M.E. (1998), “Impulse buying: modeling its precursors”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 74 No. 2, pp. 169-191. Boonchoo, P. and Thoumrungroje, A. (2017), “A cross-cultural examination of the impact of transformation expectations on impulse buying and conspicuous consumption”, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 29 No. 3, pp. 194-205. Cakanlar, A. and Nguyen, T. (2019), “The influence of culture on impulse buying”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 12-23. Chang, H.-J., Eckman, M. and Yan, R.-N. (2011), “Application of the stimulus-organism-response model to the retail environment: the role of hedonic motivation in impulse buying behavior”, The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, Vol. 21 No. 3, pp. 233-249. Chen, T. (2011), “Personality traits hierarchy of online shoppers”, International Journal of Marketing Studies, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 23-33. Clover, V.T. (1950), “Relative importance of impulse-buying in retail stores”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 66-70. Crawford, G. and Melewar, T. (2003), “The importance of impulse purchasing behaviour in the international airport environment”, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 85-98. Eysenck, S.B., Barrett, P.T. and Barnes, G.E. (1993), “A cross-cultural study of personality: Canada and England”, Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 1-9. Farid, D.S. and Ali, M. (2018), “Effects of personality on impulsive buying behavior: evidence from a developing country”, Marketing and Branding Research, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 31-43. Impulsive buying behavior 201 APJML 32,1 202 Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50. Gandhi, A., Vajpayee, A. and Gautam, D. (2015), “A study of impulse buying behavior and factors influencing it with reference to beverage products in retail stores”, SAMVAD International Journal of Management, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 1-17. Gültekin, B. and Özer, L. (2012), “The influence of hedonic motives and browsing on impulse buying”, Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 180-189. Hagger, M.S., Rentzelas, P. and Koch, S. (2014), “Evaluating group member behaviour under individualist and collectivist norms: a cross-cultural comparison”, Small Group Research, Vol. 45 No. 2, pp. 217-228. Hendrawan, D. and Nugroho, D.A. (2018), “Influence of personality on impulsive buying behaviour among Indonesian young consumers”, International Journal of Trade and Global Markets, Vol. 11 Nos 1-2, pp. 31-39. Hough, L.M., Eaton, N.K., Dunnette, M.D., Kamp, J.D. and McCloy, R.A. (1990), “Criterion related validities of personality constructs and the effect of response distortion on those validities”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 75 No. 5, pp. 581-595. Imran, Z.S., Jalees, T., Jiang, Y. and Alam, K.S.H. (2018), “Testing and incorporating additional determinants of ethics in counterfeiting luxury research according to the theory of planned behavior”, Psihologija, Vol. 51 No. 2, pp. 163-196. Jiang, Y., Miao, M., Jalees, T. and Zaman, S.I. (2019), “Analysis of the moral mechanism to purchase counterfeit luxury goods: evidence from China”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 647-669. Jiang, Y., Xiao, L., Jalees, T., Naqvi, M.H. and Zaman, S.I. (2018), “Moral and ethical antecedents of attitude toward counterfeit luxury products: evidence from Pakistan”, Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, Vol. 54 No. 15, pp. 3519-3538. John, O.P. and Srivastava, S. (1999), “The big five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives”, in Pervin, L.A. and John, O.P. (Eds), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, Vol. 2, Guilford Press, New York, NY, pp. 102-138. John, O.P., Naumann, L.P. and Soto, C.J. (2008), “Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy”, in John, O.P., Robins, R.W. and Pervin, L.A. (Eds), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, Vol. 3, Guilford Press, New York, NY, pp. 114-158. Judge, T.A., Simon, L.S., Hurst, C. and Kelley, K. (2014), “What I experienced yesterday is who I am today: relationship of work motivations and behaviors to within-individual variation in the fivefactor model of personality”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 99 No. 2, pp. 199-221. Kacen, J.J. and Lee, J.A. (2002), “ ‘The influence of culture on consumer impulsive buying behavior”, Journal of Consumer Psychology, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 163-176. Karbasivar, A. and Yarahmadi, H. (2011), “Evaluating effective factors on consumer impulse buying behavior”, Asian Journal of Business Management Studies, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 174-181. Kollat, D.T. and Willett, R.P. (1967), “Customer purchasing behavior”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 4 No. 1, pp. 21-31. Lee, J.A. and Kacen, J.J. (2008), “Cultural influences on consumer satisfaction with impulse and planned purchase decisions”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 61 No. 3, pp. 265-272. Leech, N.L., Karen, C.B. and Morgan, G.A. (2014), IBM SPSS for Intermediate Statistics: Use and Interpretation, Routledge, New York, NY. Liao, S.L., Shen, Y.C. and Chu, C.H. (2009), “The effects of sales promotion strategy, product appeal and consumer traits on reminder impulse buying behaviour”, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Vol. 33 No. 3, pp. 274-284. Lin, C.H. and Chuang, S.C. (2005), “The effect of individual differences on adolescence impulsive buying behavior”, Adolescence, Vol. 40 No. 159, pp. 551-558. Looney, S.W. (1995), “How to use tests for univariate normality to assess multivariate normality”, The American Statistician, Vol. 49 No. 1, pp. 64-70. McCrae, R.R. and Costa, P.T. (2008), “Empirical and theoretical status of the five-factor model of personality traits”, in Boyle, G.J., Matthews, G. and Saklofske, D.H. (Eds), Sage Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment, Vol. 1, Sage Publications, Los Angeles, CA, pp. 273-294. Mai, N.T.T. (2003), “Initial findings about impulsive behavior of Vietnamese consumers during the process of the economic transition”, Economics & Development Review, January, pp. 30-33. Marm, H.K. and Kongsompong, K. (2007), “The power of social influence: east-west comparison on purchasing behavior”, paper presented at International Marketing Conference on Marketing Society, Institute of Indian Management, Kozhikode, April 8–10. Merugu, P. and Vaddadi, K.M. (2017), “Visual merchandising: a study on consumer impulsive buying behavior in greater Visakhapatnam city”, International Journal of Engineering Technology Science and Research, Vol. 4 No. 7, pp. 2394-3386. Mooradian, T.A. and Swan, K.S. (2006), “Personality-and-culture: the case of national extraversion and word-of-mouth”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 59 No. 6, pp. 778-785. Muruganantham, G. and Bhakat, R.S. (2013), “A review of impulse buying behavior”, International Journal of Marketing Studies, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 149-160. Ozen, H. and Engizek, N. (2014), “Shopping online without thinking: being emotional or rational?”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 26 No. 1, pp. 78-93. Piron, F (1991), “Defining impulse purchasing”, in Holman, R.H. and Solomon, M.R. (Eds), NA – Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 18, Association for Consumer Research, Provo, UT, pp. 509-514. Pradhan, D., Israel, D. and Jena, A.K. (2018), “Materialism and compulsive buying behaviour: the role of consumer credit card use and impulse buying”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 30 No. 5, pp. 1239-1258. Prashar, S., Parsad, C., Tata, S.V. and Sahay, V. (2015), “Impulsive buying structure in retailing: an interpretive Structural modeling approach”, Journal of Marketing Analytics, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 215-233. Roberts, B.W., Lejuez, C., Krueger, R.F., Richards, J.M. and Hill, P.L. (2014), “What is conscientiousness and how can it be assessed?”, Developmental Psychology, Vol. 50 No. 5, pp. 1315-1331. Rook, D.W. (1987), “The buying impulse”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 189-199. Rook, D.W. and Fisher, R.J. (1995), “Normative influences on impulsive buying behavior”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 305-313. Rook, D.W. and Hoch, S.J. (1985), “Consuming impulses”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 12 No. 1, pp. 23-27. Schiffman, L. and Kanuk, L.L. (2008), Consumer Behaviour (Perilaku Konsumen), 7th ed., PT Indeks, Jakarta. Shahjehan, A., Zeb, F. and Saifullah, K. (2012), “The effect of personality on impulsive and compulsive buying behaviors”, African Journal of Business Management, Vol. 6 No. 6, pp. 2187-2194. Silvera, D.H., Lavack, A.M. and Kropp, F. (2008), “Impulse buying: the role of affect, social influence, and subjective wellbeing”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 23-33. Simons, L.E., Elman, I. and Borsook, D. (2014), “Psychological processing in chronic pain: a neural systems approach”, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Vol. 39 No. 2, pp. 61-78. Singh, R. and Nayak, J.K. (2016), “Effect of family environment on adolescent compulsive buying: mediating role of self-esteem”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 28 No. 3, pp. 396-419. Singelis, T.M., Triandis, H.C., Bhawuk, D.P. and Gelfand, M.J. (1995), “Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: a theoretical and measurement refinement”, Cross-Cultural Research, Vol. 29 No. 3, pp. 240-275. Sofi, S.A. (2018), “Personality as an antecedent of impulsive buying behaviour: evidence from young Indian consumers”, Global Business Review, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 1-19. Impulsive buying behavior 203 APJML 32,1 204 Stern, H. (1962), “The significance of impulse buying today”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 26 No. 2, pp. 59-62. Sun, T.R. and Yazdanifard, R. (2015), “The review of physical store factors that influence impulsive buying behavior”, Economics, Vol. 2 No. 9, pp. 1048-1054. Tendai, M. and Crispen, C. (2009), “In-store shopping environment and impulsive buying”, Africa Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 1 No. 4, pp. 102-108. Thomas, A.K., Louise, R. and Vipinkumar, V.P. (2018), “Impact of visual merchandising, on impulse buying behavior of retail customers”, International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 474-491. Thompson, E.R. and Prendergast, G.P. (2015), “The influence of trait affect and the five-factor personality model on impulse buying”, Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 76, pp. 216-221. Toffoli, R. and Laroche, M. (2015), “Cultural and language effects on the perception of source honesty and forcefulness in advertising: a comparison of Hong Kong Chinese bilinguals and Anglo Canadians”, Proceedings of the 1998 Multicultural Marketing Conference, Springer, Cham, pp. 206-206. Verma, J. and Triandis, H.C. (1999), “The measurement of collectivism in India”, in Walter, L.J., Dale, D.L., Deborah, F.K. and Sussana, H.A. (Eds), Merging Past, Present and Future in Cross-Cultural Psychology: Selected Papers from the Fourteenth International Congress of the International Association of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers, Lisse, pp. 256-265. Verplanken, B. and Herabadi, A. (2001), “Individual differences in impulse buying tendency: feeling and no thinking”, European Journal of Personality, Vol. 15 No. S1, pp. 71-83. Watson, D. and Clark, L.A. (1991), “Self- versus peer ratings of specific emotional traits: evidence of convergent and discriminant validity”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 60 No. 6, pp. 927-940. Xiao, S.H. and Nicholson, M. (2011), “Mapping impulse buying: a behaviour analysis framework for services marketing and consumer research”, The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 31 No. 15, pp. 2515-2528. Xu, Y. and Huang, J.S. (2014), “Effects of price discounts and bonus packs on online impulse buying”, Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, Vol. 42 No. 8, pp. 1293-1302. Youn, S. and Faber, R.J. (2000), “Impulse buying: its relation to personality traits and cues”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 179-185. Zhou, L. and Wong, A. (2004), “Consumer impulse buying and in-store stimuli in Chinese supermarkets”, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 37-53. Further reading Liau, A.K., Neo, E.C., Gentile, D.A., Choo, H., Sim, T., Li, D. and Khoo, A. (2015), “Impulsivity, selfregulation, and pathological video gaming among youth testing a mediation model”, Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 1-9. Verplanken, B., Herabadi, A.G., Perry, J.A. and Silvera, D.H. (2005), “Consumer style and health: the role of impulsive buying in unhealthy eating”, Psychology & Health, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 429-441. Corresponding author Syed Imran Zaman can be contacted at: s.imranzaman@gmail.com For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com Reproduced with permission of copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.