Fintech Literature Review: Evolution, Definitions, and Models

advertisement

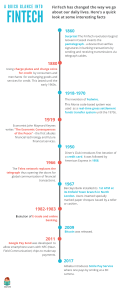

European Research Studies Journal Volume XXIV, Issue 2B, 2021 pp. 600-627 Fintech: A Literature Review Submitted 11/03/21, 1st revision 14/04/21, 2nd revision 17/05/21, accepted 15/06/21 Ferdinando Giglio1 Abstract: Purpose: This article analyzes the Fintech evolution. After describing the process of this phenomenon, some of the main definitions are provided both nationally and internationally. Finally, six main models of Fintech are analyzed. Design/Methodology/Approach: Through a systematic literature, 14 articles have been selected that deal with the phenomenon of Fintech. Findings: Six Fintech business models implemented by the ever growing number of Fintech startups have been identified, payment, wealth management, crowdfunding, loan, capital market and insurance services. Internationally, Fintech has already been defined by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank Group (WBG), the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). On a national level, on the other hand, Fintech has been analyzed by various countries, USA, United Kingdom, Singapore, China, Switzerland, China, Australia and the European Union. Practical Implications: Fintech refers to a broad set of innovations - observable in the financial field in a broad sense - which are made possible by the use of new technologies both in the offer of services to end users and in the internal production processes of financial operators as well as in the design of market enterprises, without thereby compromising new possible configurations of intersectoral activities. Originality/Value: Fintech appears to be representative of innovative methods - based on technology - of carrying out activities directly or indirectly connected to financial services rather than being a pre-defined industrial sector. Following the logic of the digital economy, Fintech contributes to designing an open and continuous network of modular services for businesses, individuals and banking, financial and insurance intermediaries, becoming a powerful acceleration force for the integration policies of the financial services markets in the EU. Keywords: Fintech, finance, banking. JEL: O31. Paper type: Literature review. Ph.D., Candidate at the University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” Capua (CE), e-mail: ferdinando.giglio@unicampania.it 1 Ferdinando Giglio 601 1. Introduction With the advent of the world wide web, concepts such as e-government, egovernance, information systems and/or Web2.0/3.0 or e-Health were born (Alshaikh, Razzaque, and Alalawi, 2017; Razzaque, Eldabi and Jalal - Karim, 2013; Razzaque, Eldabi and Jalal-Karim, 2013; Razzaque and Karolak, 2010). In business and management research, concepts such as knowledge management have received broad consideration, supported by various social science theories such as social capital theory (Razzaque and Hamdan, 2020; Razzaque and Hamdan, 2020; Razzaque and Eldabi, 2018). It is therefore not surprising that even in the financial sector it has contributed decisively, bringing it to the fore for its relevance in society, as well as in the daily life of people, all over the world, even if this sector has encountered transformations over the years due to changes in geographical regimes, political changes and legalization. Although the financial technology known as FinTech is not a new concept (Berger, 2003; Mareev, 2016; Shim and Shin, 2016; Razzaque and Hamdan, 2020) it is stated that, due to the rise and latest evolution of FinTech, a new era is dawning; FinTech is a link between the financial industry, information technology (IT), and innovation. The term "Fin-Tech" derives from the union of the words finance and technology and represents what the acronym actually means, includes the development of technology and innovation to support banking and financial skills with the latest technologies. Fin-Tech also describes the relationship between technologies such as cloud computing and mobile internet, with financial services businesses such as loans, payments, money transfer and other banking. Many scholars have investigated the FinTech phenomenon and its history, evolution, and concepts, however most researchers have focused on the FinTech revolution and its impact within the banking sector. The document is set up as follows: after having illustrated the evolution of Fintech, some of the main definitions of this term are provided at a national and international level and finally the main models of this phenomenon are examined. 2. Fintech 1.0 (1866-1967): From Analogue to Digital From the earliest stages of development, finance and technology have been interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Finance arises in the state administrative systems that were necessary for the transition from hunter-gatherer groups to stable agricultural states. For example, in Mesopotamia, written records, the earliest form of information technology, helped manage administrative and economic systems, including through financial transactions (Rowlinson, 2010). Fintech: A Literature Review 602 Therefore, the development process of finance and written documentation reinforce each other, as one of the earliest forms of information technology, highlights the link between finance and technology. Similarly, the development of money itself initially and finance are clearly intertwined. According to Mervyn King, former Governor of the Bank of England (2003-2013): “The story of money is… the story of how we evolved as social animals, trading with each other. It begins with the use of commodities as money, grain and livestock in Egypt and Mesopotamia as early as 9000 BC. ... The cost and inconvenience of using such commodities led to the emergence of precious metals as the dominant form of money. Metals were first used in transactions in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, with metal coins originating in China and the Middle East and were in use as late as the 4th century BC. The first banknotes appeared in China in the 7th century AD " (King, 2016). Money is a technology that denotes transferable values (McGroarty and Farai Mutsaka, 2011) and is one of the typical characteristics of a modern economy. Furthermore, the emergence of early computing technologies such as Abacus has greatly facilitated financial transactions. This evolutionary development can also be seen in the context of trade, with finance evolving from an early stage to both sustain trade and sustain the production of commodities for that trade. Double-entry bookkeeping (Spoke, 2015), another form of information technology important to a modern economy, emerged from the intertwined evolution of finance and commerce in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Many historians today approve the view that the financial revolution took place in Europe in the late 1600s and involved joint-stock companies, insurance and banking, all fundamentally based on double-entry bookkeeping (More, 2000). In this context, finance and access to capital supported the development of technologies and, therefore, industrial development. Therefore, the relationship between finance and technology is long-standing, with a development trajectory that sets the stage for the modern period. The increasing speed of development over the past hundred years or so is surprising compared to previous periods. The following subsections now proceed to briefly outline the developments in financial technology between the late 19th and 20th centuries, which paved the way for today's foundations of FinTech. 2.1 The First Age of Financial Globalization At the end of the 19th century, finance and technology came together to usher in the first period of financial globalization, which lasted until the beginning of the First World War. During this period, technologies such as the telegraph, railways, canals and steamships have supported financial interconnections across borders, enabling rapid transmission of financial information, transactions and payments around the world. At the same time, the financial sector has provided the necessary resources to develop these technologies (Roth and Dinhobl, 2008), Keynes’s writing in 1920, provided a clear picture of the interconnectedness of finance and technology in this first era of financial globalization: “The Londoner could order by phone, sipping his Ferdinando Giglio 603 morning tea in bed, have the various products of the whole earth in the quantity he saw fit, and reasonably expect early delivery on his doorstep; he could at the same time and with the same means venture into his wealth of natural resources and new enterprises anywhere in the world, and share, without effort or even difficulty” (Keynes, 1920). From this description it is clear that today's globalization is not new. However, the speed of technological development has changed. 2.2 The Early Post-War Period During the post-World War I period, while financial globalization was limited for several decades, technological developments, particularly in communications and information technology used in warfare, proceeded rapidly. In the context of information technology, companies such as International Business Machines (IBM) transferred codebreaking tools to early computers and Texas Instruments first produced the portable financial calculator in 1967 (Thibodeau, 2007). The 1950s were also the time when credit cards were first introduced, Diners' Club in 1950, Bank of America and American Express in 1958 (Markham, 2002). The development of what would later become a global consumer payment revolution was further supported by the creation of the Interbank Card Association (now MasterCard) in the United States in 1966 (Ben Woolsey and Emily Starbuck Gerson, 2009). By 1966, a global telex network was in place, providing the fundamental communication foundation upon which the next phase of FinTech could be developed. Xerox Corporation introduced the first commercial version of the telex successor, the fax, in 1964 under the name of Long Distance Xerography (LDX) (Auth, 2016). As noted earlier, in 1967 in the UK, Barclays implemented the world's first ATM. In our characterization, the combination of these developments marked the beginning of the FinTech 2.0 era. 3. Fintech 2.0 (1967-2008): Development of Traditional Digital Financial Services The launch of the calculator and ATM in 1967 ushered in the modern era of FinTech 2.0. From 1967 to 1987, financial services moved from an analogue industry to a digital industry. Key developments set the stage for the second period of financial globalization, which was highlighted by the global reaction to the 1987 US stock market crash. 3.1 The Modern Foundations: Digitalization and Globalization of Finance In the late 1960s and 1970s, electronic payment systems, the basis of today's mobile payment systems and the Internet, advanced rapidly, supporting both major domestic and international payments and financial flows. The Inter-Computer Bureau was established in the United Kingdom in 1968, forming the basis of today's Bankers' Fintech: A Literature Review 604 Automated Clearing Services (BACS), (Welch, 1999) and the United States Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS) was established in 1970 (Federal Reserve Bank of N.Y., 2002). Fedwire, originally founded in 1918, became an electronic system in the early 1970s (Federal Reserve Bank of N.Y., 2015). Reflecting the need to interconnect domestic payment systems across borders, the Society of Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT) was established in 1973 (Society of Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecomm, 2016) followed soon after by the collapse of Herstatt Bank in 1974 (The Economist, 2001) which clearly highlighted the risks of an increase in interconnections, particularly through the new payment system technology. This crisis triggered the first major regulatory focus on FinTech matters, with the establishment of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in 1975. This established the regulatory basis (Bank for International Settlements, 2015). The BIS Payments and Settlement Committee was established in 1990, based on a previous group established in 1980 and renamed the Payments and Market Infrastructure Committee in 2016. The combination of finance, technology and adequate regulatory attention is the basis of the current $5.4 trillion a day Global Foreign Exchange Market, the largest, most globalized and most digitized component of the global economy (Mortimer, 2013). In the securities industry, the establishment of the NASDAQ (Acronym for National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations) in the United States in 1971, the end of fixed securities fees and the eventual development of the National Market System marked the transition from physical trading of titles dating back to the end of 1600 to today's one. In the consumer banking sector, online banking was first introduced in the United States in 1980 and in the United Kingdom in 1983 by the Nottingham Building Society (NBS) (Choron and Choron, 2011). Throughout this period, financial institutions have increasingly used each new IT development in their internal operations, gradually replacing most forms of paper-based mechanisms by the 1980s, as computerization and risk management technology progressed developed to manage internal risks. One such FinTech innovation is very familiar to financial professionals today, the Bloomberg terminals. Michael Bloomberg started Innovation Market Solutions (IMS) in 1981 after leaving Solomon Brothers, where he had designed internal computer systems (Bloomberg, 2014). In 1984, Bloomberg terminals were increasingly used by financial institutions. Bloomberg is therefore one of the earliest FinTech startups and the most successful to date. Traditional financial services firms are therefore a central aspect of FinTech. As Yang Kaisheng, CEO of Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), the world's largest bank by asset size recently noted: "There is a perception that when banks develop Internet technology, it is not regarded as FinTech. People say this is a new idea, a new ideology that will eliminate agents and intermediaries and that banks cannot adapt ” (DiBiasio, 2015). Ferdinando Giglio 605 In 1987 a new period of regulatory attention began to the risks of cross-border financial interconnections and their intersection with technology. That same year, the stock market collapsed on "Black Monday". The effects of the 1987 crash on markets around the world have been the clearest indicator since the crash of 1929 that global markets were interconnected through technology. Indeed, Hollywood's vision of the financial services industry of this era in Oliver Stone's 1987 film “Wall Street” has produced one of the most iconic and popular images of this period, an investment banker wielding an early mobile phone, a IT innovation first introduced in the United States in 1983. Although almost thirty years later there is still no clear consensus on what caused the collapse, at that time a lot of attention was paid to its use by institutions. Financial systems of computerized trading systems that bought and sold automatically based on predetermined price levels (Bookstaber, 2007). The reaction has led to the introduction by exchanges and regulators of a variety of mechanisms, particularly in electronic markets, to control the speed of price changes ("circuit breakers") (Guzman, 2016). It has also led securities regulators around the world to work on mechanisms to support cooperation on cross-border interconnected securities markets, both from the perspective of volatility and market manipulation (Steinberg, 1999) in the way where the 1974 Herstatt crisis and the developing country debt crisis in 1982 triggered greater cooperation between banking regulators (Norton, 1995). Furthermore, the Single European Act of 1986 established the framework for what would become the single financial market in the European Union. That law, in addition to the Big Bang financial liberalization process in the UK in 1986, the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 and an ever-increasing number of financial services directives and regulations since the late 1980s, established the basis for the possible full interconnection. Certainly, by the late 1980s, financial services had largely become a digital industry, based on electronic transactions between financial institutions, financial market participants and clients around the world. By 1998, this process had completed its course with financial services becoming, for all practical purposes, a digital industry. This period also showed the initial limitations and risks in complex computerized risk management systems (e.g. Value at Risk (VaR)), with the collapse of Long-term Capital Management (LTCM) in the wake of the Asian and Russian financial crisis of the 1997- 1998 (Jorion, 2000). Advances in the mid-1990s certainly propelled FinTech forward. However, the emergence of the internet really set the stage for the next level of development, starting in 1995, when Wells Fargo began using the World Wide Web (WWW) to provide consumer online banking services (Riggs, 2015). In 2001, eight banks in the United States had at least one million online customers, with other major jurisdictions around the world rapidly developing similar systems and related regulatory frameworks to address risk (Cronin et al., 2001). By 2005, the first direct banks with no physical branches had emerged and had gained wider public acceptance (ING Direct, HSBC Direct) in the UK. At the turn of the 21st century, Fintech: A Literature Review 606 banks' internal processes, interactions with outsiders, and an ever-increasing number of their interactions with retail customers were completely digitized. And as digitization has become ubiquitous, IT spending from the financial services industry has increased accordingly. Furthermore, regulators began to use new technology, particularly in the context of stock exchanges, and by the late 1990s, computerized trading systems and records had become the most common source of information on market manipulation. 3.2 Regulatory Approaches to Traditional DFS in Fintech 2.0 As technology has changed, the regulatory structure and strategies have also changed. As noted above, the internationalization of finance since the late 1960s, supported by new technologies such as electronic payment systems and stock exchanges, has supported important developments in cross-border regulatory cooperation, notably through the Basel Committee and IOSCO. In addition, particularly in the United States and Europe, major efforts have focused on regulating the new emerging risks in payment systems and electronic exchanges in the 1980s and 1990s. As an example of the regulatory interest in FinTech developments, David Carse, then Deputy Director General of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), gave a keynote speech in 1999 in which he considered the new regulatory framework needed for e-banking (Carse, 1999). It is important to note that this speech was made in 1999, while e-banking has existed since 1980. This time frame highlights the delay in the regulatory reaction to technological changes. This delay is predictable and often welcomed, as it is consistent with effective market regulation. Regulating all new innovations applicable to the financial sector has a limited advantage (Chan, 2016). Preventive regulation would not only increase the workload of regulatory agencies and would tend to severely stifle innovation, but would also have limited benefits (Menon, 2016). By providing direct and virtually unlimited access to their accounts, the technology eliminated the need for depositors to be physically present in a branch to withdraw funds. Indirectly, the development of e-banking could facilitate electronic bank runs, as the lack of physical interaction eliminates the friction that comes with a withdrawal. In turn, the instant ability to withdraw funds can increase the stress on a financial institution that has liquidity problems during a banking crisis (Carse, 2016). Regulators also found that online banking creates new credit risks. By removing the physical link between the consumer and the bank, competition was expected to increase. On a large scale, although initially positive for consumers, this competitive pressure can be problematic for the financial stability of the system. The deregulation of the US banking market in the 1980s provided an example of the systemic risks that arise from deregulation (Barberis, 2012). Second, on a smaller individual scale, the constraints of being personally known by a loan officer would be lost as the loan establishment decision can be replaced by an automated system. Ferdinando Giglio 607 The benefits of online banking have, to date, outweighed the risks. Better data organization can lead to a better understanding of borrowers' true credit risk and thus enable financial institutions to offer products that are better aligned with the individual consumer's risk profile. This insight precedes the emergence of big data analytics, which provides more granular insights into consumer profiles (Douglas Arrier and Jarios Barberis, 2015). However, the comparison between the risk created by online banks and FinTech startups stops there because Carse's speech (1987) was built on the premise that these technological innovations would only be used by authorized financial insights. This distinction is the key to understanding the tipping point between FinTech 2.0 and FinTech 3.0. 4. Fintech 3.0 (2008-present): Democratizing Digital Financial Services? There has been a shift in mindset from the retail client's point of view about who has the resources and legitimacy to provide financial services. While it is difficult to pinpoint how and where this trend began, the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) could represent a turning point and may have catalyzed the growth of the FinTech 3.0 era. In parallel, the twenty-first century has so far been characterized by technological development and change from any previous period, highlighting the second characteristic of speed. The remainder of this section will show that an alignment of market conditions after 2008 has supported the emergence of innovative market players and new applications of new technology for the financial services industry. Among these factors were, public perception, regulatory control, political demand, and economic conditions. Each of these points will now be explored within a narrative that illustrates how 2008 acted as a turning point and created a new group of actors applying technology to financial services. Indeed, since 2008, banks' brand image and perceived stability has been shaken to the core. A 2015 survey reported that American levels of trust in tech companies managing their finances are not only increasing, but outstripping their trust in banks. For example, the level of trust Americans have in CitiBank is 37%, while the trust in Amazon and Google is seventy-one percent and sixty-four percent, respectively. In addition to established companies like Amazon and Google, there is a growing number of unlisted companies and young start-ups that manage customer money and financial data. China provides a clear example of this phenomenon (Weihuan Zhou, Douglas W. Arner, and Ross P. Buckley, 2015) with over 2000 P2P lending platforms operating outside a clear regulatory framework (Alois, 2015). This does not discourage millions of lenders and borrowers, who are willing to place or borrow billions on these platforms due to the lower cost, seemingly better potential return and greater affordability. Likewise, the "reputation" factors that mean that only banks can offer banking services are not relevant to a large percentage of people in developing countries. For 2 billion bankless individuals, this Fintech: A Literature Review 608 factor is weak, because for them banking can be a commodity that can be supplied by any institution, regulated or not (Ash Demirguc et al., 2015). In other words, there may be a lack of "legacy behavior" in developing markets such that the public does not expect only banks to provide financial services. As effectively described more than two decades ago, "banking is necessary, the banks are not” (McLean, 1998). 4.1 Fintech and the Global Financial Crisis: Evolution or Revolution? The financial crisis impacted the public perception of banks and the people who ran the financial services industry. First, as its origins became more widely understood, the public perception of banks deteriorated. For example, predatory lending methods directed at civil rights-free communities have not only breached banks' consumer protection obligations, but also damaged their position (Sumit Agarwal et al., 2014). Second, two groups of individuals have been hit by the financial crisis. As the financial crisis turned into an economic crisis, it is estimated that 8.7 million American workers have lost their jobs (Kell, 2014). Combining the decline in employment prospects with the public's growing distrust of the traditional banking system, many financial professionals have found a new sector, FinTech 3.0, in which to apply their skills (Mark Esposito and Terence Tse, 2014). In addition to traditional financial professionals, a new generation of highly educated recent graduates have faced entry into a difficult traditional job market (Fottrell, 2014). Their educational background has at times equipped them with the tools to understand the financial markets and their skills have found a fruitful outlet in FinTech 3.0. Post-financial crisis regulation has increased banks' compliance obligations and changed their business incentives and business structures. In particular, the universal banking model has been tested with separation obligations and regulatory capital increases, modifying the incentive or ability of banks to grant low-value loans (Ferrari, 2016). Furthermore, the not always appropriate use of some financial innovations, such as debt bond guarantees (CDOs), was considered a contribution to the crisis by separating the credit risk of the underlying loan from the originator of the loan (Segoviano et al., 2013). Finally, the need to ensure the orderly bankruptcy of banks drove the implementation of the resolution regimes of financial institutions in all jurisdictions, which required banks to prepare recovery and resolution plans (RRPs) and conduct stress tests to assess their feasibility (Barberis, 2012). Consequently, since 2008, the business models and structures of banks have been reformulated. 4.2 From Post-Crisis Regulation to Fintech 3.0 These regulatory responses to the GFC (e.g., Dodd Frank Act, Basel III) were clearly necessary in light of the social and economic impact of the financial crisis and could make it less likely that the next financial crisis will be triggered by the same causes (Buckley, 2015). However, these post-crisis reforms have had the unintended Ferdinando Giglio 609 consequence of spurring the rise of new technology players and limiting banks' ability to compete. For example, Basel III resulted in an upward revision of capital adequacy requirements for banks (Release, 2013). While this has increased market stability and risk-absorbing capacity, it has also diverted capital away from small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and individuals. Many individuals have therefore turned to P2P lending platforms or other innovations to meet their credit needs. During the FinTech 2.0 period, the expectation was that e-banking solution providers would be supervised financial institutions. Indeed, the use of the term "bank" in most jurisdictions is limited to companies duly authorized or regulated as financial institutions (UK Companies House, Companies Act, 2006). However, the FinTech 3.0 era has shown that the provision of financial services is no longer the sole responsibility of regulated financial institutions. The provision of financial services by non-banks can also mean that there are no effective national regulators to act on the concerns of host regulators, and therefore whether the provider is regulated or not can make little difference. This means that the last safeguard could come from consumer education and a distrust of placing funds with an offshore non-bank. Public demand for greater access to credit was met by the approval of the Jump Start Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act in the United States in 2012. The JOBS Act addresses these issues of unemployment and credit supply in two ways. Regarding employment, the JOBS Act aims to promote the creation of start-ups by providing alternative ways to finance their businesses. The preamble of the law states: "One act: Increase American job creation and economic growth by improving access to public capital markets for emerging growth companies" (Jump Start Our Business Startups Act, 2012). From a political point of view, the promotion of entrepreneurship has few disadvantages, as it has a direct impact on job creation. On financing, the JOBS Act has helped start-ups bypass the credit crunch caused by rising bank costs and limited lending capacity. The JOBS Act has allowed start-ups to directly access the capital needed to support their business by raising funds to replace equity on P2P platforms. The JOBS Act was not specifically intended to support FinTech 3.0 because it applied to start-ups in general. But it bolstered FinTech 3.0 as these alternative funding sources became available at a time that coincided with increasing regulatory pressures limiting banks' ability to innovate, a heightened public perception of traditional banks, and the outflow of human talent. which provided the market and knowledge needed for new FinTech start-ups to emerge. In summary, the financial services industry has been hit by a "perfect storm" financial, political and public at its source - since 2008, enabling a new generation of market participants to establish a new paradigm known today as FinTech. Fintech: A Literature Review 610 4.3 The Fintech Industry Today: A Topology Based on this evolutionary analysis, it is possible to develop a complete topology of the FinTech sector. FinTech today encompasses five main areas: (1) finance and investments, (2) internal operations and risk management, (3) payments and infrastructure, (4) data security and monetization, and (5) customer interface. Finance and investment: Much of the attention of the public, investors and regulations today is focused on alternative financing mechanisms, especially crowdfunding and P2P lending. However, FinTech clearly extends beyond this narrow scope to include the financing of the technology itself (e.g., through crowdfunding, venture capital, private equity, private placements, public offerings, quotes, etc.). From an evolutionary perspective, the tech bubble of the 1990s is a clear example of the intersection of finance and technology, just as NASDAQ is the dematerialization of the securities sector that followed in the following decades and the advent of program trading, high frequency trading and dark pools. Looking ahead, in addition to the continuous development of alternative financing mechanisms, FinTech is increasingly involved in sectors such as robo advisory services (Halder, 2015). Internal financial operations and risk management: These have been a key driver of financial institutions' IT spending, especially since 2008, as financial institutions have sought to create better compliance systems to address the massive volume of post-crisis regulatory changes. For example, about a third of Goldman Sachs' 33,000 employees are engineers, more than LinkedIn, Twitter or Facebook (Marino, 2015). Paul Walker, Goldman Sachs global co-head of technology, said they "were competing for talent with start-ups and tech companies." From an evolutionary perspective, the development of financial theory and quantitative techniques of finance and their translation into financial institution operations and risk management was a key feature particularly in the 1990s and 2000s, as the financial industry built VaR-based systems and other systems to manage risk and maximize profits (Lowenstein, 2000). Payments and infrastructure: Internet payments and mobile communications are a central focus of FinTech and have been a driving force particularly in developing countries. Payments have been an area of great regulatory attention since the 1970s, resulting in the development of domestic and cross-border electronic payment systems that now support $5.4 trillion a day in global currency markets. Similarly, infrastructure for securities trading and settlement and OTC derivatives trading continues to be an important aspect of the FinTech landscape and are areas where IT and telecom companies seek opportunities to disintermediate traditional financial institutions. Data security and monetization: These are key themes in FinTech today, especially as both FinTech 2.0 and FinTech 3.0 begin to leverage the monetary value of data. Ferdinando Giglio 611 Following the GCF, it became clear that the stability of the financial system is a matter of national security. The digitized nature of the financial sector means that it is particularly vulnerable to cybercrime and espionage, both of which are increasingly important in geopolitics. This digitization and consequent vulnerability are the result of decades of development, highlighted in previous sections and, in the future, will remain a major concern for governments, policy makers, regulators and industry players, as well as customers (Moody, 2015). However, FinTech innovation is clearly present in the uses to which "big data" can be applied to increase the efficiency and availability of financial services. Interface for consumers, especially online and mobile financial services - this will continue to be a major focus of traditional financial services and non-traditional FinTech developments. This is another area where established and new IT and telecom companies are looking to compete directly with traditional financial services firms. Interestingly, it may be in developing countries where factors increasingly combine to support the next era of FinTech development. The consumer interface offers the greatest opportunities for competition with the traditional financial sector, as these technology companies can leverage their large existing customer bases to launch new financial products and services (Osawa, 2015). 5. Definitions of FinTech Fintech is a term that derives from the combination of the words finance and technology and is defined as an interdisciplinary field that combines finance, technology management and innovation, describes the connection of internet-related technology with commercial service activities of the financial sector such as banking transactions and money lending. Financial technology terminology emerged when Citicorp launched a project called the Financial Services Technology Consortium that facilitates technology collaboration in the financial services industry. It was only in the year 2014 when the new Fintech attracted public attention and has since then been used to describe the development of technology, ecosystems and platforms, which allows and facilitates access to services and processes within of the financial sector, making it more efficient and convenient for more people. Imran (2014) revealed that throughout the history of the financial sector it has been the largest user of technology in the service sector after the telecommunications industry. Fintech offers a promising change to the banking and financial services industry by significantly reducing costs, increasing diversified services and providing more stable industrial and market scenarios (Iman, 2019). There is a wide variety of definitions of the concept in academic practice and in business journals. Meanwhile, while stakeholders agree on the core elements of the term, its scope has not been clearly defined. Opinions vary that only new emerging technology-based financial companies can be called fintech and even operators can only be called fintech if they innovate a new technology-based product or service. Table 1 shows some of the main definitions of the term Fintech. Fintech: A Literature Review 612 Table 1. Definitions of FinTech Definitions “Financial technology” or “FinTech” refers to technology-enabled financial solutions. The term FinTech is not confined to specific sectors (e.g. financing) or business models (e.g. peer-to-peer (P2P) lending), but instead covers the entire scope of services and products traditionally provided by the financial services industry. Financial innovation can be defined as the act of creating and then popularizing new financial instruments as well as new financial technologies, institutions and markets. It includes institutional, product and process innovation. An economic industry composed of companies that use technology to make financial systems more efficient. Source Arner, DW; Barberis, JN; Buckley, RP Year 2015 Farha Hussain 2015 McAuley, D. 2015 Fintech is a service sector, which uses mobilecentered IT technology to enhance the efficiency of the financial system. Fintech is a portmanteau of financial technology that describes an emerging financial services sector in the 21st century. Kim, Y., Park, Y. J., & Choi, J. 2016 Investopedia 2016 FinTech describes a business that aims at providing financial services by making use of software and modern technology. Fintech weekly 2016 Organizations combining innovative business models and technology to enable, enhance and disrupt financial services Ernst & Young 2016 6. The International Definitions of Fintech There have been requests for more international cooperation on how to deal with the fast growing FinTech market and several international financial organizations such as IMF, WBG, FSB and others have taken an active part in preparing the political agendas. 6.1 International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank Group (WBG) In 2018 IMF and WBG launched the Bali FinTech Agenda (BFA), with the fundamental objective of considering how technological innovation is changing the provision of financial services with consequences for efficiency and economic growth, financial stability, inclusion and integrity. BFA describes FinTech as "advances in technology that have the potential to transform the provision of financial services by stimulating the development of new business models, Ferdinando Giglio 613 applications, processes and products" (IMF, 2018). The BFA is a response to requests from IMF and WBG members to expand international cooperation and provide recommendations on creating a favorable global regulatory environment for FinTech. The Agenda has an informative nature to support awareness, further training and ongoing work. The main conclusion of the policy paper of the IMF and the World Bank group "Fintech: the Experience so far" (IMF, 2019) is that, although there are important regional and national differences, countries make extensive use of FinTech capabilities to accelerate economic growth and integration. 6.2 Financial Stability Board (FSB) The FSB was established in 2009 after the G20 meeting and has played a key role in making it easier to reform international financial regulation and supervision. The FSB defines FinTech as "the technology that has enabled innovation in financial services and could lead to new business models, applications, processes or products with a material effect associated with the provision of financial services" (Financial Stability Board, 2019). In 2017, the FSB published "Financial Stability Implications from FinTech", classifying FinTech activities focused on the services provided, rather than the suppliers or technologies used as: ➢ payments, clearing and settlement; ➢ deposits, loans and capital raising; ➢ insurance; ➢ investment management; ➢ market support. (The Financial Stability Board, 2017) This classification arises from the work of the FSB Financial Innovation Network (FIN), is based on the classification of the World Economic Forum (2015). In 2015, the World Economic Forum released "The Future of Financial Services" report which explores the transformational potential of new entrants and innovations on business models in financial services. This project offers answers to the question "Which new innovations are most effective and relevant to the financial services industry?" As a result, 11 key clusters of innovations were identified based on how they impact core functions of financial services: 1) cashless world; 2) emerging payment rails; 3) insurance unbundling; 4) related insurance; 5) alternative loans; 6) shift of customer preferences; 7) crowdfunding; 8) authorized investors; 9) outsourcing of processes; Fintech: A Literature Review 614 10) smarter and faster machines; 11) new market platforms. The WEF approach to defining FinTech is based on financial market functions that meet customer needs. Solutions and technology tools are changing, while the needs of major customers remain relatively unchanged. 6.3 The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Furthermore, the OECD has been actively involved in determining the nature of the FinTech phenomenon. In the document "Financial Markets, Insurance and Private Pensions: Digitization and Finance", the OECD attempts to overcome the limitations in the definitions and categories developed so far. Defines FinTech as "innovative applications of digital technology for financial services" (OECD, 2018). Criticizing the definitions provided by the WEF, the US National Economic Council, the FSB, the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), the EU and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), have stated that "fintech is not only about the application of digital technologies to financial services but also the development of business models and products based on these technologies and more generally on digital platforms and processes" (OECD, 2018) ranks new technologies and digital processing in financial services and major financial activities and services: 1) distributed ledger technology; 2) big data; 3) the internet of things; 4) cloud computing; 5) artificial intelligence; 6) biometric technologies; 7) augmented / virtual reality. 6.4 The International Organization of Securities Commission (IOSCO) In partnership with the G20 and the FSB, IOSCO develops, implements and supports compliance with internationally recognized standards for securities regulation. IOSCO defines FinTech as "a variety of innovative business models and emerging technologies that have the potential to transform the financial services industry". FinTech's innovative business models usually automatically offer one or more specific financial products or services using the Internet. Emerging technologies such as cognitive computing, machine learning, artificial intelligence and distributed ledger technologies (DLT) can be used for both new and traditional members, they can also significantly change the financial services industry (International Organization of Securities Commissions, 2017). Ferdinando Giglio 615 Eight categories of FinTech are described in the IOSCO Research Report on Financial Technologies (FinTech): ➢ Payments; ➢ Insurance; ➢ Planning; ➢ Loan and crowdfunding; ➢ Blockchain; ➢ Trading and investments; ➢ Data and analysis; ➢ Security (International Organization of Securities Commissions, 2017). These FinTech categories meet basic client demands and focus on the functions of the financial markets. 6.5 The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) takes advantage of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) FinTech definition (BIS, 2018). According to BCBS, regulators in many countries have not officially defined FinTech, partly due to definitions already available, for example, such as the FSB, or also because it is too early to give a definition for a rapidly evolving phenomenon. Those who define FinTech see them as a company that provides innovative services, a business model or a start-up of new technologies in the financial sector. BCBS believes that jurisdictions may need to identify specific products and services in order to establish a well-defined approach for possible regulation. 7. The National Definitions of Fintech 7.1 National Economic Council, White House, USA In the United States, there is no specific regulatory framework for FinTechs subject to a single federal or state regulation. Depending on the FinTech assets provided, the company may be subject to laws and regulations, both at the federal and state level. Fintech will be regulated like any other company if it provides services that are regulated activities, for example, state-level consumer lending, money transmission and virtual currency licensing, at the federal level of consumer loan laws, and antidiscrimination laws. The National Economic Council (NEC) defines FinTech as "innovations in financial technology", but in general "a broad spectrum of technological innovations that impact a wide range of financial assets, including payments, investment management, raising capital, deposits, loans and insurance, regulatory compliance and other activities in the financial services sector" (National Economic Council, 2017). The NEC advises its policy makers and regulators to study best practices Fintech: A Literature Review 616 abroad, although each practice is not suitable for each jurisdiction, exchanging ideas and best practices can help to agree policies, regulations and promote innovation around the world. US regulation of financial markets is fragmented due to the different legal frameworks at the federal and state levels, making it very difficult to create a unified sandbox for the country. The first sandbox was established in Arizona in 2018, allowing starups, entrepreneurs and established companies to test their innovative financial products or services in a regulatory friendly environment in the state of Arizona. An innovative financial product or service is a financial product or service that includes an innovation (State of Arizona, 2018). The legal explanation for innovation is "with respect to the provision of a financial product or service or a substantial component of a financial product or service, the use or incorporation of new or emerging technology; the reimagining of uses for existing technology to address a problem, provide an advantage, or otherwise offer a product, service, business model or delivery mechanism that is not known to the Attorney General to have a comparable widespread offer in this state" (section ARS 41-5601, 2019). According to the Arizona Revised Statutes (A.R.S.) "anyone can apply to join the regulatory sandbox to test an innovation" (section A.R.S. 41-5603, 2019), including existing Arizona licensees and unlicensed companies. Although the term FinTech is used on the Arizona Attorney General's home page, in the context of the FinTech sandbox, the term "FinTech" is not used in the A.R.S. In July 2018, the United States Treasury released Executive Order 13772 on Core Principles for Regulating the United States Financial System: “A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunity.” Although this report is aimed at FinTech and emphasizes that services are significantly impacted by rapid technological advances, rapid digitization of the economy and capital surplus to facilitate innovation, the term FinTech is not defined. In this report FinTech is explained as "financial technology" and FinTech companies as "technology-based" (United States Department of the Treasury, 2018). The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) in its document "Considering Charter Applications From Financial Technology Companies" defines FinTech companies as "companies offering products and innovative technology-based services" and may be eligible for a Nazi bank card onale (The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, 2018). In late 2018, following the UK's lead, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) launched a unified regulatory sandbox to drive FinTech development. The Bureau's Office of Innovation has issued a "No Action" letter to Upstart Network, a consumer lending platform that leverages artificial intelligence, machine learning and alternative data sources to assess consumer credit and automate the loan. Two sandboxes have been created, the Compliance Assistance Sandbox and the Trial Disclosure Sandbox, however the official documents framing the activities of the sandbox (CFPB, 2018a; 2018b) do not use the term "FinTech". Ferdinando Giglio 617 7.2 The United Kingdom In the UK, there is no specific regulatory framework for FinTech firms subject to financial regulation. FinTech will be regulated like any other company if it provides services that are regulated activities, such as "traditional" financial services, for example, payments or loans, or "alternative" financial services such as crowdfunding. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) does not define FinTech other than "financial technology" but provides structures / guidelines by its nature. First, FinTech must be innovative. The FCA says innovation should have "real potential to improve the lives of consumers coming to market in all areas of financial services" (Financial Conduct Authority, 2019). In 2019, the FCA defines the following areas of financial service providers: ➢ Banks, construction companies and credit unions; ➢ Claims management company; ➢ Consumer credit company; ➢ Electronic money and payment institutions; ➢ Financial advisors; ➢ Fintech and innovative companies; ➢ Insurance and general protection; ➢ Investment managers; ➢ life insurers and social security institutions; ➢ Lenders and mortgage brokers; ➢ Mutual companies; ➢ Sole consultants; ➢ Wealth managers (FCA, 2019). Improvement is seen through products that are better suited to customer needs, better access or lower prices. Furthermore, FCA states that innovation must be offered by different actors, both in terms of the type of company and the people behind the development. In the report on "UK FinTech" Treasury of the UK in partnership with E&Y defines FinTech "as high-growth organizations that combine innovative business models and technology to enable, improve and discontinue financial services" (Treasury of the United Kingdom and Ernst & Young, 2016). This report also identifies the key characteristics and emerging areas of FinTech innovation. In particular, the UK has developed an innovative policy strategy to improve the country's competitiveness as a global destination for FinTech. In 2014, FCA launched the “Project Innovate” with the aim of encouraging innovation in financial services for consumers by supporting innovative companies through a range of services. One of the activities is the regulatory sandbox that allows businesses to test innovative offers on the market with real consumers. The sandbox is open to licensed and unauthorized companies requesting membership and to technology Fintech: A Literature Review 618 companies seeking to provide innovation in the UK financial services market (FCA, 2019). According to the FCA, any company can be considered a FinTech if it is interested in providing innovation on the condition that it is a regulated business or that it supports regulated business in the UK financial services market. In 2019, with the active support of FCA, the Global Financial Innovation Network (GFIN) was launched, an international network of regulators working together to share knowledge and create an environment in which companies can experiment with cross-border solutions. Of the 12 founding members, GFIN has grown rapidly to cover a network of 35 organizations. 7.3 Singapore Singapore is the leading FinTech economy in the ASEAN region and is recognized around the world as a good example of the balance between FinTech support and restrictive rules. As in other countries, even in Singapore there is no detailed regulatory framework for FinTech companies. FinTech companies need to acquire the right licenses that match their business models, while some FinTech business models may require multiple licenses based on the services they offer. FinTech companies are primarily financial institutions, regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), but the latest trends include the rise of non-financial technology players in the FinTech area. One of the tasks of the MAS is to promote FinTech innovation and make Singapore an international hub for FinTech. Singapore's ambition is to be a smart nation and the financial sector is seen as one of its integral parts. In 2016 MAS launched the FinTech regulatory sandbox. According to the guidelines, the applicant can be a financial institution, a FinTech firm, a professional services firm that collaborates or provides support to such activities or any interested company that can experiment with innovative financial services in a production environment, but at the interior of a clearly defined space and duration. The emphasis is on the use of innovative technologies to provide financial services that are regulated or may be regulated by MAS (MAS, 2016). Additionally, the express sandbox was launched in 2019 to complement the current regulatory sandbox. The sandbox express, in the first phase, covers the following activities regulated by the MAS: ➢ carry out activities as an insurance intermediary; ➢ establishment or management of an organized market; ➢ remittance activities (MAS, 2019b). Under the Proof of Concept (POC) scheme of MAS Financial Sector Technology and Innovation (FSTI), which provides financial support for the experimentation, Ferdinando Giglio 619 development and dissemination of nascent innovative technologies in the financial services sector, two types of companies are eligible for the application: ➢ a financial institution with MAS license in banking, capital market, financial advice, insurance and money exchange and remittances; ➢ a technology or solution provider (artificial intelligence, API, blockchain / distributed ledger technology (DLT), cloud, cybersecurity, digital ID and e-KYC and regtech) with at least one licensed financial institution as a partner (MAS, 2019a). This program supports two activities: ➢ Projects aimed at giving life to a new concept to solve problems at the sector level using technologies or business processes; ➢ Tests aimed at the final response to the regulatory uncertainty on the risks and benefits of replacing obsolete processes with innovative ones. The government of Singapore is actively cooperating internationally with the authorities and regulatory bodies of other countries, both globally as a member of GFIN, and regionally as a member of the ASEAN Financial Innovation Network (AFIN). 7.4 China There is no specific legislative framework for FinTech companies in China. In 2015, China's central and industry regulators jointly published Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Development of Internet Finance (Guiding Opinions). This is the first global government regulation on internet finance in China. The concept of Internet Finance was born thanks to China's interest in promoting the “Internet Plus” strategy in all sectors and, therefore, has unique characteristics. However, the concept of Internet Finance is the same as the concept of FinTech and both can be used to describe new technologies in financial services. In accordance with the guiding opinions, Internet finance consists of: ➢ payment via the Internet; ➢ Online loan; ➢ equity crowdfunding; ➢ sale of funds on the Internet; ➢ Online insurance services; ➢ Internet Consumer Finance (PBOC, 2015). The Chinese government provides a supportive legislative framework for FinTech firms, for example, by assisting financial institutions, internet firms and e-commerce firms in building innovative internet platforms, selling financial products and effectively expanding supply chain operations of e-commerce businesses for the Fintech: A Literature Review 620 above categories. In addition, China's policy includes preferential tax policies for FinTech businesses, for example, the reduction of corporate income tax from 25% to 15% or even exemption from it and state subsidies. In general, China's legislative environment has been quite flexible compared to other countries, but disruptions and failure in the FinTech industry are leading the government to enforce stricter requirements for regulating the industry. New types of FinTech businesses have also sprung up in China, such as the provision of risk management services driven by big data and artificial intelligence, as well as blockchain technology and business services. FinTech business in China is governed by various administrative measures and guidelines, with leading supervisory authorities such as China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission and People's Bank of China. 7.5 Australia Furthermore, in Australia, there is no specific legislative framework for FinTech companies. FinTech companies must acquire licenses that match their business models. Generally, it includes financial services and consumer credit licensing, registration and disclosure obligations, consumer law requirements, and requirements for combating money laundering and terrorist financing. In general, a company must obtain an Australian Financial Services License (AFS) or an Australian Credit License (Credit License) from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) before it can release a new financial product or service or undertake a credit activity. According to the Australian government, FinTtech is concerned with "stimulating technological innovation so that markets and financial systems can become more efficient and be more consumer-focused" (The Australian Government, 2016). The government launched the National Agenda for Innovation and Science (NISA) in 2015 in order to provide the right policy parameters to improve the economic and financial environment. Additionally, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) Innovation Hub provides practical support to FinTech and RegTech firms. According to the ASIC, FinTechs are new and innovative companies. For example, in the Australian regulatory sandbox, it is possible to test products and services without owning a license, if the company can rely on the ASIC FinTech license exemption, provided by the ASIC Corporations (Concept Validation Licensing Exemption) 2016/1175 tool (ASIC, 2017) and ASIC Credit (Concept Validation Licensing Exemption) Tool 2016/1176 (ASIC, 2016a). The FinTech license exemption, which facilitates experimentation with new FinTech services to provide advice and deal or distribute products, applies in relation to: ➢ listed or listed Australian securities; Ferdinando Giglio 621 ➢ bonds, shares or bonds issued or proposed to be issued by the Australian government; ➢ simple managed investments; ➢ deposit products; ➢ some types of general insurance products; ➢ payment products issued by ADI (an authorized institution for the collection of deposits, a company authorized under the Banking Act 1959, including, banks, construction companies and credit unions (ASIC, 2016b). Anyone has the right to seek exemption from a FinTech license to provide financial services if they are not prohibited from providing financial services and are not licensed for Australian Financial Services. 7.6 Switzerland In Switzerland, the legal framework refers to FinTech according to the principle of technological neutrality, applying the same legislation to companies that use traditional or innovative technologies. FinTech can be regulated by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) or by self-regulatory bodies, depending on the business activity: ➢ the company that accepts public deposits will be governed by the banking law (Die Bundesversammlung der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft, 1934); ➢ financial intermediary, which involves payments, individual portfolio management or lending activities under the Money Laundering Act (Federal Assembly of the Swiss Confederation, 1997); ➢ management of investment funds by the law on collective investments (Federal Assembly of the Swiss Confederation, 2006); ➢ securities from the stock exchange law (Die Bundesversammlung der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft, 1995); ➢ insurance under the Insurance Supervision Act (Die Bundesversammlung der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft, 2004); ➢ other acts may be applied such as consumer credit law or data protection law etc. In July 2019, the Swiss parliament introduced a new category of licenses. FinTech companies, which apply to all business models that accept public deposits up to CHF 100 million, without participating in any loan operation, i.e., without investing or pay interest on deposits. Additional requirement is that an institution with a FinTech license must be a joint stock company, a company with unlimited partners or limited liability and, in addition, it must have its registered office and conduct its business activities in Switzerland (FINMA, 2018). The purpose of the new license is to incentivize innovative business models, so the licensing approach should not be based on a specific type of static business model. FinTech companies, depending on Fintech: A Literature Review 622 the business model structure, can act as payment service providers or as cryptocurrency custodians or as crowdlender etc. In 2019, the Swiss government and parliament continue to work on the regulatory sandbox, amending the provisions regarding the sandbox, allowing non-banks to invest deposits received up to CHF 1 million in the sandbox. But operating in the socalled interest rate differential business is prohibited and remains a privilege of banks (FINMA, 2019). 7.7 The European Union Until now, the EU, apart from the UK, has lagged far behind major FinTech economies such as the US, China, Singapore and Switzerland. Furthermore, according to the hub ranking of the Institute for Financial Services Zug FinTech in 2018, only Amsterdam (5th place) and Stockholm (7th place) were present in the global top 10 of FinTech hubs (IFZ, 2019). The European Parliament's FinTech report reveals that more than half of the top 10 FinTech companies are located in the US, China and Israel and that Europe needs rapid innovation to stay competitive (European Parliament, 2017). This is one of the reasons why the EU is trying to be proactive and the European Commission in 2018 adopted the FinTech Action Plan for the development of a more competitive and innovative financial sector in Europe. The main aim of the plan is to increase supervisory convergence towards technological innovation and prepare the EU financial sector to benefit from new technologies. The definition provided by the European Commission in the FinTech action plan is the following: "FinTech - Technology-enabled innovation in financial services" (European Commission, 2018). The EC uses the definition provided by the international financial organization, the Financial Stability Board, to explain more specifically what FinTech is, to paraphrase it slightly. "FinTech is a term used to describe technology-enabled innovation in financial services that could lead to new business models, applications, processes or products and that could have an associated material effect on financial markets and institutions and how financial services are provided" (European Commission, 2018). According to the definition of the European Parliament, FinTech should be understood "as financing enabled or provided through new technologies, covering the whole range of financial services, products and infrastructures" (European Parliament, 2017). It also includes InsurTech and RegTech. EU institutions are working to create a more future-oriented and innovation-friendly regulatory framework that covers digitization and creates an environment in which innovative FinTech products and solutions can rapidly spread across the EU to benefit from the huge European single market. The idea behind this is to reduce regulatory requirements for the FinTech industry without compromising financial stability or protecting consumers and investors. For example, the Payment Services Directive Ferdinando Giglio 623 (PSD2), which entered into force in 2018, is a step forward in a more favorable legal environment. All new EU legislation should focus on the "innovation principle". The EP stresses that, in order to prevent regulatory arbitrage in Member States and legal states, legislation and supervision should be based on the following principles: ➢ Same services and same risks: the same rules should apply, regardless of the type of legal entity concerned or its location in the Union; ➢ technological neutrality; ➢ A risk-based approach, which takes into account the proportionality of legislative and supervisory actions to the risks and the significance of the risks (European Parliament, 2017). Positive results are already visible, according to the CBI Global FinTech report for the second quarter of 2019, Europe surpasses Asia as the second market for FinTech transactions and financing in the first half of 2019 (CB Insights, 2019). 8. Fintech Business Models According to a recent Accenture report (2016a), more than $50 billion has been capitalized in nearly 2,500 companies since 2010, as these Fintechs redefine the ways people store, save, borrow, invest, spend and protect money. Six Fintech business models activated by the growing number of Fintech startups have been identified, payment, wealth management, crowdfunding, loan, capital market and insurance services. The value propositions, operating mechanisms and key Fintech companies in each model are outlined below. 8.1 Payment Business Model Payments are fairly straight forward compared to other financial products and services. Fintech companies that focus on payments are able to acquire customers quickly at lower costs and are among the fastest in terms of innovation and adoption of new payment features. The two markets for payment fintechs are: (1) consumer and retail payments and (2) wholesale payments. Payments are one of the most widely used retail financial services on a daily basis, and also one of the least regulated financial services. According to BNY Mellon (2015), consumer and retail payment fintechs include mobile wallets, peer-to-peer (P2P) mobile payments, foreign currency, real-time payments, and digital currency solutions. for customers looking for simplified payment in terms of speed, convenience and multi-channel accessibility. Mobile payment services that can be conveniently and securely deployed on mobile devices are a popular business model. The approaches to mobile payments are not Fintech: A Literature Review 624 limited to telephone billing, Near Field Communication (NFC), barcode or QR code, a credit card on mobile websites, a card reader for mobile phones and direct mobile payment without using a card credit companies (Li, 2016). The most popular NFC-based mobile payment applications are Google Wallet, Apple Pay and Samsung Pay. Another popular payment business model is P2P payment services. Users can pay each other back with apps like PayPal and Venmo for free. 8.2 Wealth Management Business Model One of the best-known wealth management fintech business models are automated wealth managers (robo-advisors) who provide advice. These robo-advisors employ algorithms to suggest a mix of assets to invest in based on the client's preferences and investment characteristics (Ask the Algorithm, 2015). This business model benefits from demographic changes and consumer behavior that favor automated and passive investment strategies, a simple and transparent pricing structure and an attractive unitary economy that allows for low or no investment minimums (Holland FinTech, 2015). A survey by the CFA Institute in April 2016 found that most survey respondents are more concerned about the disruptive characteristics these fintech companies would have in the wealth management industry (Sanicola, 2016). Wealth management fintechs include Betterment, Wealthfront, Motif and Folio. 8.3 Crowdfunding Business Model Crowdfunding fintechs allow networks of people to examine the creation of new products, media and ideas and are raising funds for charity or venture capital (International Trade Administration, n.d.). Crowdfunding involves three parties, the project promoter or entrepreneur in need of funding, contributors who may be interested in supporting the cause or project, and the moderating organization that facilitates engagement between the contributors and the promoter. The moderating organization allows contributors to access information on various initiatives and funding opportunities for product / service development. Reward-based, donation-based and share-based crowdfunding are the best-known crowdfunding business models. Reward-based crowdfunding has been an attractive fundraising option for thousands of small businesses and creative projects. In the event that there is interest to be charged on the premium-based crowdfunding amount, the borrower sets the interest rate he is comfortable with and can guarantee a repayment within the defined time period (Mollick, 2014). In exchange for a fund from the backers of a project, the company usually offers a reward. Donation-based crowdfunding is a way to raise money for a charity project by asking donors to contribute money to it. In a donation-based crowdfunding, the lender receives nothing more than some form of Ferdinando Giglio 625 non-monetary rewards. Share-based crowdfunding is an attractive option for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as higher capital ratio requirements for traditional banks make lending to SMEs less essential than traditional banks. Sharebased crowdfunding allows entrepreneurs to reach investors interested in having shares in their startup or other small private business. The key difference between stock-based crowdfunding and other types of crowdfunding is that in stock-based crowdfunding, entrepreneurs looking for funds grant a portion of the ownership in exchange for the funds. Examples of rewardsbased crowdfunding companies include Kickstarter, Indiegogo, CrowdFunder, and RocketHub. Donation-based crowdfunding companies aimed at raising funds for charitable causes include GoFundMe, GiveForward, and FirstGiving. Stock-based crowdfunding companies include AngelList, Early Shares, and Crowdcube. 8.4 Lending Business Model P2P consumer lending and P2P commercial lending are another major trend in fintech. P2P lending fintechs allow individuals and businesses to lend and borrow with each other. Through their efficient structure, P2P lending fintechs are able to offer low interest rates and an improved lending process for lenders and borrowers. A subtle but significant difference from a bank is that these fintechs aren't technically employed in the loan itself, as they are matching lenders to borrowers and collecting fees from users. Due to this distinction, P2P lending fintechs nowadays do not need to meet the capital requirements that affect the total loan amount, while banks have become increasingly limited in the loans they engage in (Williams-Grut, 2016). Fintech innovation in lending is found in the use of alternative credit models, online data sources, price risk data analysis, fast lending processes and lower operating costs. However, the success or failure of this business model generally depends on how interest rates behave, something that companies have no control over. P2P lending and crowdfunding serve a different purpose. While the basic purpose of crowdfunding is project financing, the primary purpose of P2P lending is debt consolidation and credit card refinancing (Zhu, Dholakia, Chen, and Algesheimer, 2012). Lending fintechs include Lending Club, Prosper, SoFi, Zopa, and RateSetter. 8.5 Capital Market Business Model New fintech business models take inspiration from a full range of capital market areas such as investing, foreign exchange, trading, risk management and research. An encouraging fintech area of the capital market is trade. Trading fintechs allow investors and traders to connect with each other to debate and share knowledge, place orders to buy and sell commodities and stocks, and monitor risks in real time. Another area of capital market fintech business models is foreign exchange transactions. Fintech: A Literature Review 626 Foreign exchange transactions have been a service dominated by financial institutions. Fintechs reduce barriers and costs for individuals and SMEs transacting in foreign currencies around the world. Users can see prices in real time and send / receive funds in various currencies securely in real time, all via their mobile device. The fintechs that offer this service are able to do so at a much lower cost, through payment methods that are much more familiar to individual customers or businesses. Capital market fintechs include Robinhood, eToro, Magna, Estimize and Xoom. 8.6 Insurance Services Business Model In insurance fintech business models, fintechs work to enable a more direct relationship between the insurer and the customer. They employ data analytics to calculate and match risk, and as the pool of potential customers increases, customers are offered products to meet their needs. They also simplify healthcare billing processes. The insurance fintech business model appears to be the most well embraced by traditional insurance providers. The technology allows insurers to expand their data collection to non-traditional sources to complement their traditional models, improving their risk analysis. Insurance services fintechs that are revolutionizing the insurance industry include Censio, CoverFox, The Zebra, Sureify Labs and Ladder. 9. Conclusions This article has illustrated the evolution of fintech through three major areas, culminating in today's FinTech 3.0 which is characterized by new competition and diversity, thus highlighting the need to consider both opportunities and risks. In developed markets, this shift to FinTech 3.0 emerged in 2008 and was driven by public expectations and demands, the movement of technology companies in the financial world, and political demands for a more diversified banking system. After talking about the evolution, some of the main definitions of this phenomenon have been provided both nationally and internationally. Finally, six main fintech models were analyzed, payment, wealth management, crowdfunding, loan, capital market and insurance services. References: Agarwal, S., Zhang, J. 2020. FinTech, Lending and Payment Innovation: A Review. AsiaPacific Journal of Financial Studies, 49(7), 353-367. Arner, D., Buckley, R., Barberis, J. 2016. The Evolution of Fintech: A New Post-Crisis Paradigm? SSRN Electronic Journal, 47(4), 1271-1319. Bollaert, H., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Schwienbacher, A. 2021. Fintech and access to finance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 68(2), 1-14. Goldstein, I., Jiang, W., Andrew Karolyi, G. 2019. To FinTech and Beyond. Review of Financial Studies, 32(5), 1647-1661. Ferdinando Giglio 627 Haitian, L., Bingzhong, W., Qing, W., Jing, Y. 2020. Fintech and the Future of Financial Service: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. China Accounting and Finance Review, 22(3), 107-136. Hasan, R., Kabir Hassan, M., Aliyu, S. 2020. Fintech and Islamic Finance: Literature Review and Research Agenda. International Journal of Islamic Economics and Finance, 1(2), 75-94. Keke, G., Meikang, Q., Xiaotong, S. 2018. A survey on FinTech. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 103, 262-273. Lee, I., Jae Shin, Y. 2018. Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Business Horizons, 61(1), 35-46. Mohamed, H., Hamdan, A., Karolak, M., Razzaque, A., Alareeni, B. 2021. FinTech in Bahrain: The Role of FinTech in Empowering Women. In book: The Importance of New Technologies and Entrepreneurship in Business Development: In The Context of Economic Diversity in Developing Countries. Puschmann, T. 2017. Fintech. Bus Inf Syst Eng, 59(1), 69-76. Randy Suryono, R., Budi, I., Purwandari, B. 2020. Challenges and Trends of Financial Technology (Fintech): A Systematic Literature Review. Information, 11(12), 1-20. Rupeika-Apoga, R., Thalassinos, E. 2020. Ideas for a Regulatory Definition of FinTech. International Journal of Economics and Business Administration, 8(2), 136-154 Schueffel, P. 2016. Taming the Beast: A Scientific Definition of Fintech. Journal of Innovation Management, 4(4), 32-54. Varga, D. 2017. Fintech, the new era of financial services. Budapest Management Review, 48(11), 22-32.