On Statutory Rape Strict Liability and the Public Welfare Offen

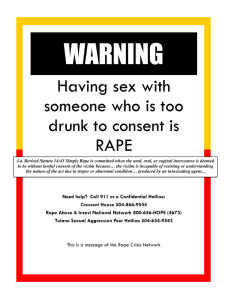

advertisement