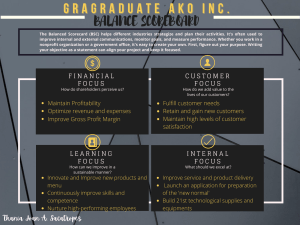

Faculty of Commerce Department of Accounting and Finance Analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to faith-based health institutions in Zimbabwe: The case of Adventist Dental Practice A dissertation by: Dumisani S. Dlodlo L018 0446K Supervised by: Dr. S. Makurumidze Submitted In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Master of Science Degree in Accounting and Finance © June 2020 Lupane, Zimbabwe Release Form Student Name: Dumisani Sipho Dlodlo Student Number: L0180446K Title of Dissertation: Analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to faithbased health institutions in Zimbabwe: The case of Adventist Dental Practice Program: Master of Science Degree in Accounting and Finance Year of Award: 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permission is hereby given to the Lupane State University to produce single copies of this dissertation and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly, or scientific research purpose only. Signed: Permanent Address: 1895 Mahatshula North, Bulawayo Date: 26/06/2020 2 Approved Form The undersigned certify that they have supervised the student Dumisani Sipho Dlodlo. Dissertation entitled ‘Analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to faithbased health institutions in Zimbabwe: The case of Adventist Dental Practice’ submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MSc. Accounting and Finance with the Lupane State University …………………………… ……………......................... SUPERVISOR DATE …………………………… ……………......................... CHAIRPERSON DATE …………………………… ……………......................... EXTERNAL EXAMINER DATE 3 Declaration I, Dumisani Sipho Dlodlo do hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of my own investigation and research, except to the extent indicated in the Acknowledgements and References and by acknowledged sources in the body of the report, and that it has not been submitted in part or full for any other degree to any other University or College. ______________ ___________ Student signature Date 4 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. S. Makurumidze for his guidance and direction during the carrying out of this research. Secondly I would like to thank the staff and administrators of Adventist Dental Practice for their cooperation and support. Thirdly I would like to acknowledge the support and care of my wife, Precious. Through thick and thin, through the sunshine and the rain, you have stood by me and supported me. Dear mother, MaMkwananzi, thank you for the encouragement, prayers and financial support. Lastly and most importantly, I would like to acknowledge my forever-friend, Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ, who enables us to do all things. 5 Dedication Dedicated to my daughter Gabriella Iminathi Dlodlo. 6 Abstract Dental service provision in Zimbabwe and Africa is relatively scarce when compared with the extent of provision in Europe and America. Faith based institutions are also playing their part, together with the government and the private sector to cater for society’s health and dental needs. The purpose of this study is to carry out an analysis in order to provide the necessary information to ascertain whether and how a model Balance Scorecard can be developed for Adventist Dental Practice in Suburbs, Bulawayo in Zimbabwe, as well as design such a Balanced Scorecard. The study setting is a faith-based dental practice in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. A systematic review of electronic databases explored the experience of BSC in high- income countries (HICs), and its feasibility in the context of low- income countries (LICs). observation, content analysis and indepth interviews where used to gather information, using the modified Delphi technique, an expert panel of clinicians and clinic managers reduced a long list of indicators to a manageable size. It was concluded that despite contextual challenges, BSC application can be undertaken in selected LICs. Committed leadership, conducive culture, quality information systems, viable strategic plans, and optimum resources are required Using modified Delphi, an expert panel of clinicians and clinic managers selected 20 indicators for the four BSC quadrants with consensus. Indicators were rated on a scale of 1–9 using a predefined criteria and median scores assigned. Feasibility of BSC in LICs is dependent on certain criteria being fulfilled. The role of the multidisciplinary teams is important in selecting indicators for BSC with consensus. Existing hospital data in LICs can be used to choose indicators for the BSC despite issues with data quality. Findings have implications for hospital management in both HIC and LIC settings. 7 Key Words Balanced Scorecard, Low-Income countries, Hospital, Systematic Review, Organizational Culture, Leadership, Modified Delphi, Indicators, Context, Pettigrew’s Framework, Case Study, Implementation, Barriers, Strategic Processes. 8 Contents List of Figures ................................................................................... 13 List of Tables .................................................................................... 14 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms ................................................. 15 Chapter 1: Introduction.................................................................... 16 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 16 1.2 Background of the study ........................................................................................................ 16 1.3 Statement of the problem ....................................................................................................... 19 1.4 Purpose of the study ............................................................................................................... 20 1.5 Objective of the study ............................................................................................................ 20 1.6 Research Questions ................................................................................................................ 21 1.7 Definition of Terms................................................................................................................ 22 1.8 Scope of the Study ................................................................................................................. 23 1.9 Limitations and Delimitations................................................................................................ 23 1.10 Assumptions of the study ..................................................................................................... 24 1.11 Organization of the study ..................................................................................................... 24 1.12 Chapter Summary ................................................................................................................ 24 Chapter 2: Literature Review ........................................................... 25 2.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 25 2.2 Performance Evaluation ......................................................................................................... 25 2.2.1 The concept of performance evaluation ................................................................................ 26 2.2.2 Comparison of the principles of traditional and modern performance evaluation methods . 27 2.2.3 Comparison of modern company performance evaluation methods ..................................... 28 9 2.3 Theoretical Framework .......................................................................................................... 32 2.4 The Balanced Scorecard Concept .......................................................................................... 34 2.4.1 Customer Perspective .............................................................................................................. 37 2.4.2 Financial perspective ............................................................................................................... 39 2.4.3 Internal processes.................................................................................................................... 42 2.4.4 Learning and Innovation Perspective ...................................................................................... 44 2.4.5 Performance ............................................................................................................................ 47 2.5 The Balanced Scorecard in Health Care ................................................................................ 47 2.6 The Five Perspectives of the BSC ......................................................................................... 49 2.7 Problems with the Balanced Scorecard.................................................................................. 49 2.8 The generations of BSC ......................................................................................................... 50 2.9 The Conceptual Framework ................................................................................................... 52 2.10 Empirical Literature Review ................................................................................................ 55 2.10.1 Zambian Case Study............................................................................................................... 55 2.10.2 Ethiopian Case Study ............................................................................................................. 56 2.10.3 Swedish Case Study ............................................................................................................... 57 2.10.4 Hawaiian Case Study.............................................................................................................. 58 2.11 Chapter Summary ................................................................................................................ 59 Chapter 3: Methodology .................................................................. 60 3.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 60 3.2 Research Philosophy .............................................................................................................. 61 3.3 Research Design..................................................................................................................... 62 3.3.1 Research Approach and Strategy............................................................................................. 62 3.4 Study Population and Sample ................................................................................................ 64 3.4.1 Study population ..................................................................................................................... 64 3.4.2 Study sample ........................................................................................................................... 64 10 3.4.3 Sampling Techniques ............................................................................................................... 67 3.5 Data Collection Techniques ................................................................................................... 68 3.5.1 Semi-structured interviews ..................................................................................................... 68 3.5.2 Content Analysis ...................................................................................................................... 69 3.5.3 Observation ............................................................................................................................. 69 3.6 Data reliability and validity ................................................................................................... 70 3.6.1 Reliabilty .................................................................................................................................. 70 3.6.2 Validity ..................................................................................................................................... 70 3.6.3 Generalizability ........................................................................................................................ 72 3.7 Data analysis techniques and presentation ............................................................................. 73 3.8 Ethical considerations ............................................................................................................ 74 3.9 Chapter summary ................................................................................................................... 75 Chapter 4: Data Presentation and Analysis ....................................... 76 4.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 76 4.2 Feasibility of BSC Implementation In LICs ........................................................................... 76 4.3 Use of existing data in designing BSC ................................................................................... 79 4.4 Depth Interview Feedback ..................................................................................................... 80 4.5 Designing the BSC Using Formal Consensus Technique ....................................................... 82 4.6 Summary of Results ............................................................................................................... 84 Chapter 5: Conclusion and Recommendations ................................. 85 5.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 85 5.2 Summary of Findings............................................................................................................. 85 5.2.1 Feasibility of BSC in the HICs .................................................................................................... 85 5.2.2 Feasibility of BSC in LIC settings................................................................................................ 85 5.2.3 Paucity of Analytical Studies On BSC in Health Care................................................................... 87 5.2.4 Indicator Selection and Measurement Issues ............................................................................ 88 11 5.3 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................ 90 5.4 Recommendations of the Study ............................................................................................. 91 5.5 Limitations of the study ......................................................................................................... 91 5.5.1 Challenges of doing research in one’s own organization ........................................................... 91 5.5.2 Limitation of Study Questionnaire ............................................................................................. 93 5.5.3 Generalizability ......................................................................................................................... 93 5.6 Recommendation for further studies ......................................................................................... 94 References ....................................................................................... 95 Appendices .................................................................................... 103 APPENDIX 1: DATA EXTRACTION FORM FOR SYSTEMATIC REVIEW .................................................. 104 APPENDIX 2: KEY INFORMANT GUIDE .............................................................................................. 106 APPENDIX 3: AUTHORIZATION TO CARRY OUT THE RESEARCH............................................................ 108 12 List of Figures Figure 2.1: Comparison of modern and traditional company evaluation methods…..……..30 Figure 2.2: The Conceptual Framework…………………………………………..………..54 13 List of Tables Table 2.1: Comparison of Modern and Traditional Company Evaluation Methods………..31 Table 3.1: Target Sample Statistics ………………………………………………………...65 Table 4.1: Analytical Framework for translating BSc experience from HI to LI settings….78 Table 4.2: Demographic Analysis of Respondents…………………………………………80 Table 4.3: Analysis of interview feedback………………………………………………….80 Table 4.4: Shortlisted List of Indicators for the ADP Balanced Scorecard…………………83 14 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms BSC: The Balanced Scorecard is a strategic planning and management tool that was designed by Kaplan & Norton. Its intent is to tie all aspects of an organisation together using details other than traditional financial measures (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). ADP: Adventist Dental Practice is a dental clinic located in Suburbs, Bulawayo. It is run and owned by the Seventh Day Adventist Church and had 8 employees at the time of carrying out this research. PM: Performance Management is an on-going communication process of creating relationships that is taken on by the employee and the supervisor. It is structured ways of letting your employees know what is expected of them, with the goal of achieving a more successful operating organization (Bacal, 2004). 15 Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Introduction The success of any business enterprise, whether large or small, depends, to a great degree, on the manner in which it is managed. Organisational management is concerned with planning, organising, leading and controlling, and in order for executives to effectively carry out their mandate, they need to carry out regular and systematic performance evaluations. This research, in the area of Strategic Management Accounting and Performance Evaluation, seeks to develop a view on the performance of Zimbabwean health institutions, and how such performance can be improved. Such an analysis would also have a telling effect on the quality of health services provided, highlight possible areas of improvement and give indications on the sustainability of the operations of these health facilities, which are critical to the health and well-being of the citizens of any nation. This chapter will focus on the background of the study, statement and purpose of the study, objectives of the study, research questions, significance of the study, limitations and delimitations as well as assumptions of the study, as well as describing how the study is going to be organised. 1.2 Background of the study Health-care is a multifaceted, multi-trillion dollar business. According to Deloitte (2019), combined health spending worldwide is projected to increase at an annual rate of 5.4 percent in 2017–2022, from USD $7.724 trillion to USD $10.059 trillion. This increase is likely to be driven by aging and growing populations, developing market expansion, clinical and technology advances, and rising labor costs. Healthcare is broad and covers many disciplines like nutrition and dietetics, physiology and dentistry. 16 According the World Health Organisation (2020), the dentist to population ratio in Africa is approximately 1:150000 against about 1:2000 in most industrialized countries. According to the Medical and Dental Practitioner’s Council of Zimbabwe (2020), Zimbabwe currently has the following numbers of registered personnel; 214 dental practitioners, 25 Dental technicians and 159 dental therapists. Dental institutions provide much needed dental health services, provide employment, and contribute to the fiscus directly and indirectly. As such, they are a necessary cog in the wheel of the Zimbabwean economy. Faith based institutions also play a key role in providing health care to the Zimbabwean population. The Zimbabwe Association of Church-related Hospitals (2020), currently has a membership of 130 hospitals and clinics. Adventist Dental Practice is a Seventh-day Adventist owned dental practice in Bulawayo. It had 8 employees at the time this study was carried out; that is 3 dentists, an accountant, a receptionist, 2 dental assistants, and a janitor. Adventist Dental Practice is run by a Board, which is under the auspices of the Zimbabwe West Union Conference of the Seventh Day Adventist Church, one of the three equal administrative units covering the nation. According to Siddiqui et al (2017), patients expect appropriate quality treatment including, but not limited to, being served by a presentable dentist, who will welcome them, listen patiently to their problem, explain treatment options and the treatment procedure. Evaluation is an important component of strategic management accounting, and in order for institutions to discern their performance, administrators need to continuously assess if they are proceeding as planned. This needs to be buttressed by clearly communicating the entity’s strategy, goals and objectives to all employees. Such activities will allow continual evaluation of corporate 17 alignment with strategic goals, as well as increase the probability and pace at which progressive change occurs in the organisation (Kim et. al., 2003) 20th Century organizational performance has been mainly anchored on the short term objective of maximizing and generating value for the shareholder as the principal stakeholder (Zingales, 2000). As a result, managers and executives have often maximized short and medium term profits at the expense of long-term sustainability (Kotler & Caslione, 2009), while relying predominantly on financial indicators (Kaplan, 2010). This approach often led to resource misallocation and was one of the factors that led to the world financial crisis at the turn of the last decade (Bair, 2011). According to Wongrassamee et. al. (2003), other limitations of traditional performance measures include exclusion of performance from strategy, measures being inflexible and fragmented, and measures hindering progressive innovation and thinking. Consequently, a more balanced approach is needed in order to effectively assess organizational performance while seeking to achieve all of the afore-mentioned goals. A number of performance management tools are available for the purpose of this study, including the Total Quality Management (Feigenbaum, 1991; Juran, 2004), Performance Pyramid (Mcnair, Lynch and Cross, 1990), the Balanced Scorecard (Kaplan & Norton 1992, 1996, 1996a) and Integrated Thinking (Topazio, 2014). The Balanced Scorecard has been selected for the purpose of this dissertation, because of its balanced focus on financial and non-financial measures. 18 1.3 Statement of the problem The Balanced Scorecard is a strategic management tool that aims to solve the inefficiencies of traditional performance evaluation based on lagging financial indicators like return on equity or earnings per share. This inefficient form of evaluation fails to capture the value of operational measures that include dealer relationships, customer loyalty and employee skills, resulting in a lack of customer orientation, as well as a neglect of product innovation, employee improvement and process engineering. These often overlooked factors are essential components for the success any business enterprise. The Balanced Scorecard was developed in a bid to make up for these inefficiencies, and provide a more comprehensive framework to the measurement of the goals and successes of any business entity. According to Gustafsson, Schold, Sihvo and Summitt (2009), employing these methods enables business enterprises to move away from dependence on historical information and focus on future performance. As a former employee of Adventist Dental Practice, I am aware of a number of strategic and performance evaluation deficiencies within the entity. Being a faith-based institution with a few employees may have resulted in a detachment from corporate best practice, and an inclination to traditional performance evaluation based on historical financial indicators, as a way of minimising the workload on the burdened employees. I envisage a situation where Adventist Dental Practice is using the Balanced Scorecard and other strategic management best practice concepts, to maximise value to all stakeholders, and achieve all organisational goals and objectives. This is the ideal, and this study is a means to that end. 19 1.4 Purpose of the study The purpose of this study is to carry out an analysis in order to provide the necessary information to ascertain how a model Balance Scorecard can be developed from continuous improvement and performance measurement monitoring at Adventist Dental Practice in Suburbs, Bulawayo in Zimbabwe. Such a model can be used as a basis for strategic management tools to be developed for other dental practices and health institutions at large, whether faith-based or not. It is desired that this study will also benefit the administrators of Adventist Dental Practice to look at their operations and make improvements from a strategic-management accounting and evaluation perspective. 1.5 Objective of the study The objectives of this dissertation are to: • analyse performance measures at Adventist Dental Practice and • evaluate if they fit into the Balanced Scorecard Model. This will be done in order to ascertain how the Balanced Scorecard Model can be implemented at Adventist Dental Practice, and provide management with information and advice on how they can improve their strategic management accounting and evaluation framework. 20 1.6 Research Questions The primary research question is “How can the Balanced Scorecard be implemented at Adventist Dental Practice?” Supportive research questions will be: 1. What would you describe as the critical success factors for ADP? 2. In what way is performance measurement carried out at ADP? 3. How is the BSC different from what performance measurement systems already existed in your clinical clinic? 4. What resources if any, can be allocated for BSC implementation 5. How do you expect the implementation of the BSC to affect the clinic’s staff and operations? 6. What might helped or hinder the BSC implementation activities in your clinic? 21 1.7 Definition of Terms Below the reader can find definitions of the terminology that we have used in this study. BSC: The Balanced Scorecard is a strategic planning and management tool that was designed by Kaplan & Norton. Its intent is to tie all aspects of an organisation together using details other than traditional financial measures (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). ADP: Adventist Dental Practice is a dental clinic located in Suburbs, Bulawayo. It is run and owned by the Seventh Day Adventist Church and had 8 employees at the time of carrying out this research. PM: Performance Management is an on-going communication process of creating relationships that is taken on by the employee and the supervisor. It is structured ways of letting your employees know what is expected of them, with the goal of achieving a more successful operating organization (Bacal, 2004). 22 1.8 Scope of the Study This dissertation contains a complete review of measures of performance and business processes in place at Adventist Dental Practice. This study is also intended to familiarise the reader with the basic components of the Balanced Scorecard Concept, as well as provide the management with recommendations to improve performance evaluation and strategic management through the Balanced Scorecard. It is assumed that the reader has a basic knowledge of the general organizational structure of a commercial enterprise as a well as a good knowledge of business, management and accounting terminology. The study seeks to assess the applicability of the balanced scorecard to Adventist Dental Practice in the period June 2019 – June 2020, considering that organisations are very dynamic and susceptible to change. 1.9 Limitations and Delimitations The main limitations in carrying out this research are the time and financial resource constraints. However, these are not expected to affect the outcome of the study. Further to this, the researcher does not have any control over the degree of honesty of the respondents. Due to the large number of potential participants, this study will focus on a sample of Adventist Dental Practice administrators, employees and patients. 23 1.10 Assumptions of the study It is assumed that: 1. Respondents’ feedback will not be affected by gender, denomination or other demographic characteristics. 2. The researcher will be granted permission by Adventist Dental Practice administrators to carry out the research and collect data. 1.11 Organization of the study The study will move from the current Chapter One (Introduction) to Chapter Two, the Literature Review, then on to the Methodology (Chapter Three), Findings and Discussions (Chapter Four) and will end with the Recommendations (Chapter Six). 1.12 Chapter Summary Having looked at the preliminary and background issues of the study, statement and purpose of the study, objectives of the study, research questions, significance of the study, limitations and delimitations as well as assumptions of the study, as well as describing how the study is going to be organised, I will now go on to review the literature on the subject matter under consideration. 24 Chapter 2: Literature Review 2.1 Introduction In order to improve the author’s and reader’s knowledge, as well as to improve insight into issues of the Balanced Scorecard, a literature search was carried out. In this section of the dissertation, this study will give a comprehensive review of the literature related to the problem under investigation. The chapter will be divided into sections, including performance evaluation, the concept of the Balanced Scorecard and its applicability to dental clinics, the four aspects of the Balanced Scorecard, performance aspects and concludes with the conceptual framework. 2.2 Performance Evaluation Performance evaluation is defined ambiguously in the research literature, with a number of authors giving various definitions for the concept. Some of these definitions are similar, while other are quite different. Neely, Gregory, Platts (1995) say performance evaluation is the process of quantifying the effectiveness and the efficiency of actions with a set of metrics. Marshall, Wray, Epstein, Grifel (1999) define it as the development of indicators and collection of data to describe, report on and analyse performance. Najmi, Kehoe (2001) posit that performance evaluation is Monitoring, management and improvement of measurable criteria that tell how the tasks were fulfilled and motivate to perform in order to achieve the goals of the company. On the other hand, Choong (2013) says performance evaluation is concerned with improvement in which its implementation requires targets or goals, so that measurement and evaluation can be made against appropriate benchmarks, while Peleckis (2013) defines it as a clock showing the current business situation and trends in its development, helping the company to decide where to go. By way of summary and analysis, some authors (Neely, Gregory, Platts (1995), Marshall, Wray, Epstein, Grifel (1999), Najmi, Kehoe (2001)) perceive performance evaluation as a process, 25 where company’s results are evaluated quantitatively by analysing certain indicators. On the other hand, the authors of the latter decade (Moullin (2007), Klovienė (2012), Choong (2013), Peleckis (2013)) note that performance evaluation should not necessary be quantitative. Managing quality evaluation, defining customer value and value created for other interested parties, disclosure of common business situation, and raising further goals for improvement are significant. Out of a list of definitions in research literature, the most plausible and exact perception of performance evaluation is provided by Klovienė (2012): it is a broad and multifunctional process that combines the key performance indicators which help evaluating performance, guarantees company management process, value creation, adjustment, speedy reaction, and enables improvement and growth of a company. 2.2.1 The concept of performance evaluation Under dynamic business environment, performance control plays an especially significant role, thanks to which one can observe ongoing changes and timely react to them. For a long time, performance evaluation has been conducted based on financial activity information by analysing indicators of profitability, liquidity, solvency and other financial ones. Such an evaluation has formed a traditional view that is as well followed by businesses nowadays. On the other hand, under modern economic environment, it is more and more often that the traditional performance evaluation methods receive criticism. Christauskas and Kazlauskienė (2009) state that the traditional performance evaluation systems do not help solving managerial problems that arise under the context of dynamic business conditions; these systems are not capable to evaluate real factors that create a value. For this reason, the modern performance evaluation methods have a higher and higher demand in business performance evaluation. 26 2.2.2 Comparison of the principles of traditional and modern performance evaluation methods Like many other business concepts, performance evaluation has evolved over time, from the traditional view and methods, to more modern and comprehensive ones. De Toni and Toncia (2001) distinguished the essential differences between traditional and modern performance evaluation systems. According to these authors, the traditional performance evaluation systems are oriented to profit and based on performance cost and efficiency analysis. With these systems, one strives to evaluate the results of the period in the past by calculating individual financial indicators and comparing them to the defined standard values. Differently from the traditional systems, the modern performance evaluation systems are oriented to consumers and satisfaction of their needs and are based on company’s created value. With these systems, one has an intention not only to evaluate results of the period in the past, but also to define reasons that led to these results and to foresee steps to improve the future results. For this purpose, not individual indicators, but sets of key indicators that include various crosscuts of performance are evaluated. According to De Toni and Toncia (2001), traditional performance measures are based on cost/efficiency, evaluate the results are profit and short term oriented, predominantly use individual and functional measures, compare with a standard and aim at evaluating. On the other hand, modern performance evaluation is value-based, evaluates results and causes, is customer and long term oriented, uses a prevalence of transversal and team measures, focuses on improvement monitoring and aims at evaluating and involving. According to Wongrassamee et. al. (2003), other limitations of traditional performance measures include exclusion of performance from strategy, measures being inflexible and fragmented, and measures hindering progressive innovation and thinking. Hence modern evaluation methods are to be preferred. 27 2.2.3 Comparison of modern company performance evaluation methods Narkunienė and Ulbinaitė (2018) after conducting research literature analysis on the topic of business evaluation systems suggest the classification scheme of performance evaluation methods (see Figure 1), where the methods are classified into smaller groups according to method contents and performance evaluation purpose. According to this scheme, performance evaluation methods are first of all classified into traditional and modern ones. Traditional performance evaluation methods, as it was mentioned earlier, include analysis of financial performance results and their relative values. Narkunienė and Ulbinaitė (2018) go on to split modern evaluation methods into 6 categories that is; Performance record (accounting) methods - that is accounting data-based performance evaluation methods that calculate the financial value created by performance. Quality management concept methods - that is performance evaluation methods that are based on the conception of total quality management. The purpose of these methods is to evaluate how the companies keep up with the requirements, what progress they do when improving their performance, and similar. Causal relationship theory models - that is performance evaluation models that distinguish the main factors which affect the successful performance. Business process evaluation models - that is models that emphasize processes during performance evaluation. The purpose of these models is to evaluate economy of performance and efficacy during the separate steps of the process. Balanced system models are overall models of performance evaluation that are closely related to company’s vision and strategy. They involve both financial and non-financial performance evaluation indicators and reflect the results in different performance perspectives. And finally, Multi-criteria methods which are complex performance evaluation methods that join many relevant performance indicators into a single summarising performance estimator. 28 Narkunienė and Ulbinaitė (2018), observed that out of all performance evaluation methods that are distinguished in the classification scheme, the most popular and most widely employed are the following ones: economic value added (EVA), balanced scorecard (BSC), performance prism, performance pyramid, six sigma, and multi-criteria performance measurement. They provided the following diagrammatic analysis. 29 Comparison of modern company performance evaluation methods Fig 2.1: Comparison of Modern and Traditional Company Evaluation Methods 30 Comparison of modern company performance evaluation methods Table 2.1: Comparison of Modern and Traditional Company Evaluation Methods On the basis of the above strength and weaknesses, the Balanced Scorecard was chosen as the basis for this study, seeing as it has the highest rates of criteria satisfaction, together with the Performance Pyramid, and the Performance Prism. The balanced scorecard (BSC) is one of the most influential theoretical frameworks in the fields of management accounting and strategic management (Modell, 2012). In addition, BSC has been successfully implemented by numerous organizations and has been regularly listed among the top ten management tools used throughout the world (Rigby and Bilodeau, 2011). According to Kryslov (2016) the BSC is considered to be one of the essential instruments of the organization management system (enterprise, firm, company, and business-unit) and hence it has been chosen above the other performance evaluation concepts that ranked at the same level. 31 2.3 Theoretical Framework During the past two decades of its existence, BSC has evolved, from a high profile performance measurement system (Kaplan and Norton, 1992), to a strategic management system (Kaplan and Norton, 1996a, 1996b), a tool for comprehensive strategy maps (Kaplan and Norton, 2000, 2001a, 2004a) and a vehicle of corporate-wide strategic alignment (Kaplan and Norton, 2006a). By noticing this evolution, Modell (2012, p. 476) argues that BSC has evolved “in tandem with increasing concerns with the need to render management accounting practices strategically relevant”. As a result, much of what scholars in management accounting, regarding its early performance management manifestations, and in strategic management, relating to its contemporary strategic implications, study, write about and teach has been greatly influenced by the fundamental arguments of the balanced scorecard theoretical framework. Therefore, BSC has become a dominant interdisciplinary theory in management accounting and strategic management. Given that all theories must survive repeated attempts at empirical falsification before they can be accepted as ‘true’ (Godfrey and Hill, 1995), one might assume that the BSC owes its influence to well-documented assessments of the empirical support for its theoretical underpinnings. Surprisingly, this is not the case. The theoretical underpinnings of BSC emanate from the central tenet of the balanced scorecard theoretical framework relating to the four distinct perspectives, i.e. financial, customer, internal-business-processes and learning and growth (Kaplan and Norton, 1992). In summary, the balanced scorecard theoretical framework hypothesizes that the four aforementioned perspectives are the cornerstones of a multidimensional performance measurement system that balances financial and non-financial performance indicators (Kaplan and Norton, 1996a). Thus, all performance indicators measuring the same perspectives are theoretically grouped into four categories, equal in number to BSC’s four distinct perspectives. 32 For that reason, all performance indicators should converge with the performance indicators measuring the same perspective and should discriminate from generic performance indicators measuring the other perspectives. According to Sagalis (2015), the above proposition can be articulated as the theoretical underpinnings of BSC. 33 2.4 The Balanced Scorecard Concept The BSC was first developed by Robert Kaplan, and Professor David Norton in 1992. BSC was first mentioned by Johnson and Kaplan (1987) in their book “Relevance Loss”. The roots of BSC were further documented in 1990, when the Nolan Norton Institute, the research arm of KPMG auditing company, sponsored a one-year, multi-company study, called “Measuring Performance in the Organisations of the Future” (Kaplan and Norton, 1996). The study, according to Kaplan and Norton (1996), was motivated by a belief that existing performance measurement tools, mainly focusing on financial accounting measures, were becoming out-dated. The term “balanced” means that each indicator or measure has its own weight that shows its relative importance. These weights help companies know which goals, indicators, and tasks are most important to their strategy. In addition, the term also leads firms to have a balanced view of business activities as whole. This includes internal processes, customer relationships, learning and growth, as well as finance. In this view and according to Kaplan and Norton (1996), companies should balance financial and non-financial perspectives. Consequently, this balanced view provides an objective benchmarking indicator for evaluating the progress in achieving an organisation’s strategic objectives. The balanced also means that companies should balance their objectives. Furthermore, BSC enables companies to develop a more comprehensive view of their strategic and operations management. Kaplan and Norton (1992) proposed a new concept to overcome the limitations of traditional performance measures, which over-emphasised the financial perspective of an enterprise. The Balanced Scorecard Concept as proposed by Kaplan and Norton (1992) is hinged on the idea that management should not be limited, in their view, to the financial aspects of a business, but should also focus on the customer, internal, learning and innovation aspects. In their view, this would 34 encourage management to have a comprehensive and holistic view of the organisation. The Balanced Scorecard concept also allows administrators and those charged with governance to focus on the critical aspects of the dental practice in order to drive strategy forward. The Balanced Scorecard helps to communicate and implement an organisation’s strategy. The Balanced Scorecard is an essential technique for assessing performance of a business enterprise. It builds on the Critical Success Factor (CSF) concept of a few performance measures, and reports four different aspects with equal weights. These four perspectives are the: customer, financial, internal and learning perspectives. The financial perspective measures the enterprises’ ability to meet the shareholders expectations (Samir, 2006). The customer perspective deals with the firm’s ability to meet customer demands (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). The internal perspective seeks to assess the appropriateness of the businesses selected policies and processes in meeting customer and shareholders’ expectations (Samir, 2006). Finally, the learning perspective measures if the institution is dynamic enough to sustain its ability to change (Kaplan & Norton, 2005). The aim of the Balanced Scorecard is to add leading measures that represent indicators of future financial performance, to traditional, historical financial measures. The Balanced Scorecard emphasizes the need for an evaluation model that covers all relevant areas of relevant corporate performance management systems. Asiedu (2015) posits that the model encompasses a balance of all four perspectives necessary to ensure that improvements are not made in one area, at the detriment of another facet. Therefore, the Balanced Scorecard is a very efficient tool for developing and communicating strategy by enabling the organisational model to be portrayed as a strategy map, forcing those charged with governance to think from cause-to-effect (Kaplan & Norton, 2005). Organizational performance is the sustained strategic and integrated success of an organization that is attained by 35 improving the contribution of the people who work in it and developing the capabilities of teams and individuals (Nordberg, 2008). The Balanced Scorecard helps organisations in the management process, by helping entities to translate their mission and strategy into concrete goals and measures. The Balanced Scorecard also balances the external and internal aspects by considering the financial (for shareholders and customers) and non-financial (internal processes, innovation and learning) measures respectively (Kim et. al., 2003). In addition, the Balanced Scorecard balances results measures (financial outcome) and driver measures (for future improvements i.e. customer, internal processes, learning and innovation) (Wongrassamee et. al., 2003). The Balanced Scorecard is ranked as an excellent evaluation tool because it ties the performance matrix very closely to an enterprise’s strategy and long term vision. If properly implemented and driven internally, the Balanced Scorecard can aid in the creation of a new corporate culture which is strategically aligned (Gibbons and Kaplan, 2015). The main disadvantage of the Balanced Scorecard concept is that it may not bring about the intended results if not modified in accordance with the mission, strategy, culture and technology of the enterprise in which it is to be used (Kim et. al., 2003, Khamba et. al., 2012). Not-withstanding these drawbacks, the Balanced Scorecard has been adapted to suit and cater for a number of different scenarios, including sustainability (ethics, social issues and the environment) where it is known as Sustainability Balanced Scorecard (SBSC)(Hansen and Schalleger, 2012). These researchers posit that the SBSC can be a promising framework for integrating strategy and sustainability in business. 36 2.4.1 Customer Perspective In the customer perspective of the BSC, companies identify the customer and market segments in which they have chosen to compete. This perspective enables the firm to position their key customer measurements with the market segments with which they have chosen to compete. The organization of the decisive customer satisfaction indicators lets management form a more coherent strategy concerning the goals of the customer perspective. The key customer outcome measurements are: satisfaction, loyalty, retention, acquisition, and profitability (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). Of these measurements only satisfaction is applicable to ADP. Retention and acquisition of patients would conflict with their goals of minimizing patient appointments and treatment duration. If private companies fail to recognize their customer’s needs they inevitably lose their customers to competitors who offer higher quality goods and better customer service. Kaplan and Norton (1996) state that when implementing the BSC managers must translate their mission and strategy statements into specific market and customer based objectives. When formatting their organizational goals to that of the BSC, the firm will apply the five core measures of; market share, customer acquisition, customer retention, customer satisfaction, and customer profitability. These outcome measures represent the targets for companies’ marketing, operational, logistics, and product and service development processes. Once an organization has completed the initial step of identifying their market segment, they can address the issue of objectives and measures to deliver satisfaction to their customers, which in the future will create retention, acquisition and market share (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). The above measures do have their disadvantages. “These outcome measures are lagging indicators, meaning that employees will not know how well they are doing with customer satisfaction or customer retention until it is too late to affect the outcome” (Kaplan & Norton, 1996, pg. 85). Kaplan and Norton (1996) also state that the measures do not communicate what 37 the employees should be doing in their day-to-day activities, and that managers must also identify what their targeted customer’s value and deliver to these customers. Contrary to these limitations the BSC gives managers the ability to concentrate on delivering superior quality goods to their targeted customer segments. Ruekert (1992) defined customer orientation that Lee (2006) quotes as the degree to which an entity obtains and uses information from customers, develops a strategy that will meet customer needs and implement that strategy in response to customers desires. Adventist Dental Practice customers include all its stakeholders including patients, patients family members, medical aid societies, suppliers, employees, board members and the sponsoring organisation. Customer orientation would positively contribute to the performance of any enterprise in the sense that customers will continue to be satisfied as their needs and wants continue to be met. This would positively impact the institution as resultant higher treatments would result in higher revenue and higher profits that could be used to improve the internal processes of the institutions as well as improve its learning and innovation processes (Lee, 2006). This view is supported by Pelham and Wilson (1996). On the other hand, failure to meet customer needs and wants would result in the dental practice’s patient base becoming eroded, as patients would end up patronizing other dental clinics. A significant reduction in the production and sales revenue of an institution would result in a depletion funds to improve the other key aspects of internal processes, innovation and learning. Researchers have opted to assess customer orientation from different perspectives. For example, Chen et al. (2006) evaluate customer orientation in two dimensions: namely customer satisfaction 38 and institutional promotion. They measure satisfaction by looking at treatment finality and the number of patient complaints. They suggest that the dental clinic’s image can be measured by looking at the number of applicants seeking treatment, institutional reputation and the institution’s participation in charity activities. Whilst some measures like reputation can be difficult to measure objectively, they describe the type of relationship that exists between the entity and its stakeholders. Consequently, this research will employ them as a of Adventist Dental Practice’s customer orientation. 2.4.2 Financial perspective Financial measures historically have been the only tool, which a manager of a company could use to navigate themselves through the unclear waters of performance measures. Financial measures, though a good provider of information concerning quarterly and financial reports is mired in an accounting model that was developed centuries ago. This antiquated model is still being used by informational age companies, and is failing to account for vast sums of intangible assets (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). “During the industrial age financial measures were an adequate tool for valuing the success of a firm, which was not reliant on customer loyalty and motivated employees as critical for success” (Kaplan & Norton, 1996, pg.7). In today’s dynamic and new age marketplace it is necessary to account for a company’s intangible and intellectual assets, such as the quality of products and services, skilled and motivated team members, a satisfied and loyal customer base as well as brand name value and intellectual patents (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). Although Adventist Dental Practice does not have shareholders they do have financial concerns and goals that must be accounted for, and that require delineation. Cost effectiveness and the quality of patient care are both concerns for the organization. 39 During the initial phase of the scorecard design and construction an organization should ask themselves what their goals are and how they plan on measuring them. The following is a list of some of the goals (and measurements) the management of ADP use when the investigating into their organization’s goals and strategies; maximizing value at least cost (cost-to-spend ratio); LOF minimization (number of claims to the LOF); lowest cost per capita (average of all medical costs divided by the number of inhabitants) and lowest cost per patient (cost per patient relative to the number of patiens). Identifying the goals and the ways in which they should be measured are the foundational stages of building a successful BSC (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). According to Kaplan and Norton (1996), when an organization are building their BSC they should promote all of its business units to link their financial objectives to the corporate strategy and in doing this use their financial goals as the pinnacle for development of the other areas of their scorecard. A mistake commonly made by management is applying the same financial standards and measurement to all of their business units. This unilateral approach fails to recognize that individual business units may use completely different strategies and approaches in achieving goals and it may not be appropriate to apply a single financial metric to all of the companies units. Thus, in the early stages of a company’s BSC development it is crucial that the business unit executives determine the strategy and financial goals for each individual unit and establish the relevant method of application while maintaining a prevalent and clear picture of the entire company’s goals (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). According to Kaplan and Norton (1996), financial objectives represent the long-term goal of the organization: to provide superior returns based on the capital invested in the unit. The BSC does not conflict with this vital goal. They also stated that the implementation of the BSC could make the financial objectives explicit while customizing financial objectives 40 to business units in different stages of their growth and life cycle. The drivers of the financial measurements should be modified for each business unit’s competitive environment and strategic goals. Ultimately, all of the objectives within the BSC should be linked with the financial objectives to recognize the long-run goals of the business (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). Amaratunga et al. (2001) posit that the financial perspective shows the results of strategic choices made in the other three perspectives; that is, internal processes, the customer perspective, and innovation and learning. The financial perspective also indicates whether the organisations strategy, implementation and execution have contributed to the bottom line. In other words, it is used as a barometer to measure how well the enterprise has performed (Wongrassamee et al., 2003). Lee (2006) alleges that prudent financial management helps to achieve better results, economically, that is at minimum cost. The financial perspective is important because it gives the results of all the other perspectives of the Balanced Scorecard. In addition, the other perspectives may not be realised, without the resources and funding provided by the financial perspective (Niven, 2002). However, the traditional approach of using the financial perspective as the only performance management tool has been criticised by many researchers. Amaratunga et al. (2001) claim that this arrangement encourages short-termism, furnishes misleading information for decision making, fails to consider requirements of today’s organisation and strategy, provides misleading information for cost allocation and control of investments, and furnishes abstract information to employees. Love and Holt (2000) maintain that over reliance on financial measures is retrogressive and out of date. In their analysis, Kaplan and Norton (1992) concluded that assessing 41 companies based on financial aspects only do not accurately reflect the interest of the shareholders. The measures that can be used to measure financial performance of a dental institution include good financial management, fund raising capabilities and external relationships (Dorweiler and Yakhou, 2005), dental income, reduced human resource cost and increased asset usage (Chen et al., 2006). 2.4.3 Internal processes After the objectives of the customer perspective and financial perspective have been put into effect, the organization will then begin to address the other two perspectives, the internal business perspective and the learning and growth perspective (Kaplan & Norton, 2004). “The Internal Perspectives accomplish two vital components of an organization’s strategy: (1) they produce and deliver the value proposition for customers, and (2) they improve processes and reduce costs for the productivity component in the financial perspective” (Kaplan & Norton, 2004, pg. 98). “The internal measures for the BSC should stem from the business processes that have the greatest impact are; cycle time, quality, employee skills, and productivity” (Kaplan & Norton 1992, pg. 132). “It is also necessary that companies try to identify their core competencies as well as the critical technologies that are required to safeguard their market share” (Kaplan & Norton 1992, pg. 132). For the BSC, Kaplan and Norton (1996) recommend that the managers define a complete internal process value chain that starts with the innovation process. The innovation process begins with 42 identifying current and future customers’ needs and creating and forming new resolutions, and applying new formulas to solve these needs. According to Baker et. al.(2008), Satisfaction of such customer needs include the focus on timelines (length of waiting for appointments); quality (quality of patient care – defined by the patient) and service (responsiveness – as defined by the patient). Customers’ needs, in the context of ADP, pertain to the needs of patients within the healthcare system. The final process in the value chain could be the post-sale service that offers services after the sale, follow-up, letters and thank you notes. This final process would help strengthen customer loyalty, and perhaps achieve a higher rate of customer retention and acquisition if the customers’ needs were meet. When a high level of customer satisfaction is achieved the organization will be rewarded with references and recommendations (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). “The process of deriving objectives and measures for the internal-business process perspective represents one of the sharpest distinctions between the BSC and traditional performance measurement systems” (Kaplan & Norton, 1996, pg. 92). The more traditional measures of performance relied heavily on controlling and relied almost exclusively on the financial aspect. These more complex, flexible and complete methods of performance measurement appear to be an improvement over the old reliance on financial reports (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). This may be especially true for a healthcare organization such as ADP, which is attempting to remain within budget while providing superior medical care to its residents. Financial measures alone would be an insufficient evaluation of failure or success when accounting for the quality of an individual’s life. 43 Papenhausen and Einstein (2006) define internal processes as critical internal functions that drive the customers (stakeholders) satisfaction, and consequently, the financial outcome of the business enterprise. Amaratunga et al. (2001) share the same perspective; they view internal processes as mechanisms through which performance expectations are achieved. Following an assessment of its customers’ requirements (needs and wants), an entity needs to implement processes that will convert customer wishes and desires into realities (Lee, 2006). This would require dental practices workers at all levels to have the necessary technical skills and knowledge to be able to deliver the desired customer outcomes. These skills and knowledge would need to be complimented by modern facilities and technology, as well as appropriate procedures and regulations (Punniyamoorthy and Murali, 2008). Internal processes play a big role in organisational performance. Dorweiler and Yakhou (2005) claimed that good internal processes in an institution lead to, among other things, quality of services and efficiency. Chen et al. (2006) measured internal processes from two perspectives, namely quality service process and complete facilities. On quality service process they look at administration efficiency and patient-to-staff ratio. 2.4.4 Learning and Innovation Perspective Innovation and learning can be defined as the identification of the sets of skills, and processes that drive the dental practice to continuously improve its critical internal processes (Papenhausen and Einstein, 2006). According to Edwards (2006), learning and innovation encompass steps and activities that focus on an enterprise’s development and learning ability. These may include the number of qualified employees or the total number of hours spent on staff training. This perspective includes staff training and attitudes to organisational culture related to the selfimprovement of individual employees and the institution as a whole. This aspect recognises that in a knowledge-worker organisation, like a dental clinic, human capital is the greatest resource. 44 Kaplan and Norton emphasise the fact that 'learning' denotes more than ‘training', in the sense that one may carry out a training exercise that does not better the trainees in any way. The final perspective develops the objectives and measures necessary to motivate learning and growth with the organization. The objectives established in the financial, customer, and internal business process perspectives identify the key areas that are indispensable when it comes to accomplishing superior quality products and performance. The goals of the learning and growth method perspective are to create successful strategies that serve as a road map for achieving the targets of the first three perspectives. For an organization to maintain competitiveness and growth, it is essential that they make continual investments back into their firm. The BSC stresses the importance of investing in not only traditional areas of investment, such as, equipment and research & development but also advocates investment in their infrastructure (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). Through Kaplan and Norton’s (1996) experience building BSCs they have been able to identify three principal categories for the learning and growth perspective; employee capabilities, information systems capabilities and motivation, empowerment, and alignment. These three principal categories help to clarify the objectives and stress the importance of the learning and growth perspective. Innovation processes can be the most important processes performed by a company to increase productivity, sustain a competitive advantage and promote growth from within. Often management overlooks the importance of learning and innovation (Kaplan & Norton, 2004). Within an organization, like ADP, it is imperative that a strong emphasis be put on the learning and continual growth perspective. If there is no decoupling between the strategy and the ability to promote and teach this strategy, then there is a much greater chance for success. 45 “The learning and growth perspective identifies the intangible assets that are most important to the strategy, and the objectives within this perspective identify which jobs (the human capital), which systems (the information capital), and what kind of climate (the organizational capital) are required to support the value creating internal process” (Kaplan & Norton, 2004, pg. 32). The four perspectives link to create a chain of relationships that strengthen and unite the intangible assets and the tangible assets within an organization. This unification leads to improved process performance, customer satisfaction and financial performance (Kaplan & Norton, 2004). Businesses entities need to identify customer needs, and once these have been identified, institutions need to convert these requirements into activities that can process them into tangible output that customers can use. At times, it is found that there is a gap between the internal processes requirements in terms of skills, information systems and the organisation climate, and that which is available, (Lee 2006). For instance, the institution might be lacking some skills that are necessary for the provision of a need to the customer. It is the duty of the innovation and learning to consider what it must do to maintain and/or develop the know-how required for understanding and satisfying customer needs (Amaratunga et al., 2001). In addition to meeting the gaps that might be there, Amaratunga et al. (2001) also emphasise that the purpose of this perspective is to consider how it can sustain the necessary efficiency and productivity of processes which are presently created for customers. 46 2.4.5 Performance Performance is a multifaceted concept, and in analysing it, Kaplan and Norton (1996) considered time, quality, flexibility, financial efficiency, customer satisfaction and human resource as some of its key tenets. However, Lee (2006) viewed these dimensions into common factors of efficiency, quality, responsiveness, cost and overall effectiveness. In the commercial world, customers use their knowledge and expectations to measure the quality of the services being offered (Parasuraman et al., 1986). However, unlike products that are manufactured, it is not easy to measure the quality and effectiveness of services in service industry like dental services because of the intangibility of the outcome. Despite this challenge, Soutar and McNeil (1996) recommend the use of a service-marketing instrument called SERVQUAL (Service quality) to measure intangibles. This instruments prescribe that service be viewed from five dimensions. The dimensions include: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness; assurance and empathy. 2.5 The Balanced Scorecard in Health Care According to Schaeffers (2007), the medical fraternity is undergoing a paradigm shift, where patients are now being called customers and medical institutions are now regarded as ‘industries’ charged with producing more and better goods (health care) within available budgets. Innovative management methods and regular collection and reporting of financial information (linking clinical, volume and financial data by product line) are being advocated in health care settings (Travis, Bennet, Heinnes, Pang, Bhutta, Hyder, Pielemeier, Mills, Evans, 2004). The emphasis on performance measurement in the 1990s led to the development of dashboard metrics and report cards emerged as viable options for evaluation of health-care programmes and management practices (Woodward, Manuel, Goel, 2004). The first refereed article on BSC in healthcare appeared in 1994 and discussed the need for ‘continuous quality improvements’ in the healthcare setting (Griffith, 1994). 47 About a decade after Kaplan and Norton developed the Balanced Scorecard, a number of healthcare institutions in high-income countries began to adapt and implement the BSC framework for their organisations. Examples of BSC use in healthcare are scarce. However, performance measurement strategies similar to the BSC have been studied in Ethiopia (Hartwig et. al, 2008) and Sri Lanka (Ministry of Health Sri Lanka and Japanese International Cooperation Agency, 2003). Recently BSC was used in Afghanistan at a national level to show how provinces and the nation are doing in the delivery of the basic package of health services in Afghanistan (Peters et. al. 2007). It is therefore evident that healthcare systems are looking for empirical evidence to demonstrate excellence in performance (Axelsson, 2000) and with these recent examples of the use of PM systems in lower income countries there is increasing scope of applying BSC in the lower income country context. Applicability of the Balanced Score Card to Health Delivery Systems, developing country While Kaplan & Norton (1996) state that the Balanced Score Card has been used mainly by large and complex business organisations, Ten Asbroek ,Arah ,Geelhoed, Custers, Delnoij & Klazinga (2004) developed a national performance indicator framework for the Netherland’s health system based on the Balanced Score Card. Further to this, Peters, Noor, Singh, Kakar, Hansen & Burnham (2007) also developed a BSC framework to monitor the progress of the Afghani public health system, which they state as the first study of this kind for a developing nation. This BSC was designed to assist the Afghani government to monitor their health facilities and partnerships with NGOs providing health services after their public health system had been decimated by decades of war and conflict under the Taliban. The researchers in the Afghani study faced obstacles in developing a BSC based on surveys, including the lack of a sampling frame, insecurity, bad roads and poor communications. 48 At the design workshops for the Afghani study by Ten Asbroek et. al (2004) , six domains were identified for incorporation into the BSC: patient perspectives, staff perspectives capacity for service provision (structural inputs), service provision (technical quality) financial systems as well as overall vision for the health sector. 2.6 The Five Perspectives of the BSC One key tenets of successful BSC implementation is adapting the framework to the context in which it is to be applied. In a study of the BSC implementation at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSH-RC),Thunaian (2013) posits that the BSC has been amended to include five main perspectives: quality of care; medical care; employee; financial; and the education and research perspective (learning and growth). In the study, the researcher outlines that the medical care perspective focuses on medical and clinical services. The quality care perspective concentrates on increasing service capacity, through effective facility planning, and expansion of projects. The employees’ perspectives include strengthening staff selection, recruitment and retention strategies, incorporating human resources (HR) and recruitment programs, and the provision of an employee friendly environment and education programs. These are achievable through the approach of change management, skill projection and effective organizational roles. The financial perspective focuses on improving the efficiency and effectiveness of financial decision making processes. In addition, it focuses on cost and billing actions with operational linkages. The educational and research perspective provides improvement in systems, advanced IT training, data reporting skills, employee educational programs, skill development programs, role playing programs and research integration initiatives. 2.7 Problems with the Balanced Scorecard Schneiderman (1999), the former Vice President of Quality and Productivity at Analog Inc. (USA), after observing the use and misuse of the Balanced Scorecard over many years, offered 49 the following six reasons as to why it may fail as a strategic management tool. Non-financial measures are incorrectly identified as the primary drivers of future stakeholder satisfaction, the metrics are poorly designed, improvement goals are negotiated rather than based on objective analysis, lack of simplification of high level goals to the process level where actual improvement resides, absence of state of the art improvement systems as well as absence of a quantitative linkage between non-financial measures and expected financial results. Other pitfalls of the BSC are described in the table below. 2.8 The generations of BSC Kaplan and Norton upgrade BSC through three generations. Speckbacher et al. (2003) present these three generations in detail. In the first generation, companies use specific multi-dimensional perspectives for strategic performance measurement that combines financial and non-financial strategic measures. The second generation is similar to the first generation and additionally applies 50 the strategy by using cause-and-effect relationships. The third generation implements a strategy by defining objectives, action plans, outcomes and linking incentives with BSC. Molleman (2006) asserts that 50%, 21%, and 29% of companies applied the first, the second and the third generation, respectively. Molleman (2006) reported that companies using the third generation benefit more from the full services of BSC. The third generation fills the gap between theoretical strategic plans and real business activities. However, Kaplan and Norton (1996) suggest that when applying the third generation, companies should be careful to link the reward system to BSC. There is a risk in applying the reward system due to the unreliability of the selected measures, lack of knowledge in linking the four perspectives; and firms’ satisfaction with their BSC compared to firms with less developed BSC. Malina and Selto (2001) suggest that BSC can be worked if organisations reward managers on the basis of the achievements of BSC measures. Speckbacher et al. (2003) found that companies implementing higher generations, such as the third, are less subject to strategic difficulties. The study also showed that the majority of companies associated with less developed BSC suffered from difficulties in implementing BSC. In addition, half of the companies failed to obtain causeand-effect relationships as they had only recently started the implementation process. 51 2.9 The Conceptual Framework The understanding of BSC perspectives is determined by several factors, including the version/generation applied, the level of communication, the weighting, the management information system, the organisational culture and the linkage between perspectives and the business strategy. The conceptual framework considers that efficient application of these factors may improve business performance, and in turn, the business strategy is achieved. Kaplan and Norton (2001a) explain that for organisations to achieve their business strategy, whether they are a manufacturer or providing service, private or public, for profit or not-for-profit, all organisational participants need to be aligned to the strategy. The challenge for organisations is how to enlist the hearts and minds of their employees. According to Huang (2009) the BSC model depends on activities that develop by learning and growth perspective. This perspective captures the ability of employees, information systems, and organisational alignment to manage a business and adapt to change. Process success depends on skilled and motivated employees, as well as accurate and timely information. The BSC literature suggests that the implementation process should start with education by creating strategy awareness. Then, the understanding of employees should be tested to ensure that they have received the right message. This should involve the use of tools to check that employees’ understanding and day-to-day behaviour is conducive to achieving the organisation strategy. Organisations should always know how many of the employees understand the process and how many do not. A precise budget should be set for the employee communication and education process. 52 Kaplan and Norton (2001b) have reported that the more employees understand the strategy, the higher their individual performance is. In their study, they discovered that 67% of the employees deliver high performance when they know and understand the entities strategic direction, whereas 26% deliver higher performance with senior managers using more efective communication. These statistics above show that when employees understand the strategy of their organisation, their performance becomes higher. In formulating the conceptual framework, the researcher builds on the work of Thunaian (2013) who developed a BSC conceptual framework for a hospital. Thunaian’s (2013) framework summarises the determinants of BSC understanding. Basing on the reviewed literature in his study, he said the understanding of the five perspectives of BSC in the hospitals are determined by many factors including the level of communication; the generation of BSC applied; weighting; management information systems; the culture; and the linkage of perspectives. Efficient and effective implementation of these perspectives may improve the business performance, and meet the business strategy as a result. 53 The Conceptual Framework BSC Perspective BSC Determinant Medical Care Communication Quality Care Generation Employees Finance Education and Research Weighting Management Information System Performance Strategy Vision Performance Management Mission Objectives Culture Linkage BSC Improves Performance BSC is linked with Business Strategy Figure 2.2: The Conceptual Framework 54 2.10 Empirical Literature Review 2.10.1 Zambian Case Study Mutale, Stringer, Chintu, Chilengi, Mwanamwenge (2014) proffer that in many low income countries, the delivery of quality health services is hampered by health system-wide barriers which are often interlinked, however empirical evidence on how to assess the level and scope of these barriers is scarce. A balanced scorecard is a tool that allows for wider analysis of domains that are deemed important in achieving the overall vision of the health system. In the study, the researchers present the quantitative results of the 12 months follow-up study applying the balanced scorecard approach in the Better Health Outcomes through Mentorship and Assessments intervention (BHOMA) with the aim of demonstrating the utility of the balanced scorecard in evaluating multiple building blocks in a trial setting. The BHOMA is a cluster randomised trial that aims to strengthen the health system in three rural districts in Zambia. The intervention aims to improve clinical care quality by implementing practical tools that establish clear clinical care standards through intensive clinic implementations. This paper reports the findings of the follow-up health facility survey that was conducted after 12 months of intervention implementation. Comparisons were made between those facilities in the intervention and control sites. STATA version 12 was used for analysis. The study found significant mean differences between intervention(I) and control (C) sites in the following domains: Training domain (Mean I:C; 87.5.vs 61.1, mean difference 23.3, p = 0.031), adult clinical observation domain (mean I:C; 73.3 vs.58.0, mean difference 10.9, p = 0.02 ) and health information domain (mean I:C; 63.6 vs.56.1, mean difference 6.8, p = 0.01. There was no gender differences in adult service satisfaction. Governance and motivation scores did not differ between control and intervention sites. The study demonstrates the utility of the balanced 55 scorecard in assessing multiple elements of the health system. Using system wide approaches and triangulating data collection methods seems to be key to successful evaluation of such complex health intervention. 2.10.2 Ethiopian Case Study According to Teklehaimanot, Teklehaimanot, Tedella, and Abdella (2016), in 2004, Ethiopia introduced a community-based Health Extension Program to deliver basic and essential health services. The researchers developed a comprehensive performance scoring methodology to assess the performance of the program. A balanced scorecard with six domains and 32 indicators was developed. Data collected from 1,014 service providers, 433 health facilities, and 10,068 community members sampled from 298 villages were used to generate weighted national, regional, and agro-ecological zone scores for each indicator. The national median indicator scores ranged from 37% to 98% with poor performance in commodity availability, workforce motivation, referral linkage, infection prevention, and quality of care. Indicator scores showed significant difference by region (P < 0.001). Regional performance varied across indicators suggesting that each region had specific areas of strength and deficiency, with Tigray and the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region being the best performers while the mainly pastoral regions of Gambela, Afar, and Benishangul-Gumuz were the worst. The findings of the study suggest the need for strategies aimed at improving specific elements of the program and its performance in specific regions to achieve quality and equitable health services. 56 2.10.3 Swedish Case Study According to Gustaffson et. al. (2009) the BSC framework gives management the opportunity to better understand how the organization is functioning. They emphasize communication as the vital factor for success with the Balanced Scorecard and the organization. Nowadays, in a world of rapid change and competition the organizations face an untold quantity of leadership challenges, and by applying the Balanced Scorecard the management will get the chance to achieve results by putting their strategies into action. The Jonkoping County Council is responsible for the healthcare within its area, and is one of numerous organizations that have implemented the Balanced Scorecard. The purpose of the study was to investigate the reasons the healthcare department within Jonkoping County Council applied the Balanced Scorecard, how they use it, and to understand from their perspective how it benefits them. In addition to this, the researchers presented advice from employees to the management that is considering implementing the tool. The study was qualitative with an abductive approach, where both primary and secondary data were used in the research paper. The primary data was gathered through interviews with different departments at Jonkoping County Council, which contributed to different views on the use of the Balanced Scorecard. Theories about the Balanced Scorecard were gathered through secondary data. The results of the study showed that generally, the management at Jonkoping County Council were pleased and satisfied with the Balanced Scorecard. In addition to this they are all motivated and engaged in using the framework. However, they believe that the main drawbacks with the Balanced Scorecard are to make employees understand and connect the daily work to the framework, as well as finding the “correct” numerical values that reflects the organization. 57 The benefits according to the management are the multidimensional view of the organization through the four perspectives in the Balanced Scorecard, and also the fact that they now have a framework which encourage the staff to strive to achieve a unison vision through action plans. The nursing-staff were not aware of the term ‘Balanced Scorecard’ or the four perspectives, and therefore wanted to get more information about it from their executives, since they are expected to work in accordance with the framework. Through interviews with the upper- and middle management and the nursing staff the researchers drew the conclusion that the Jonkoping County Council implemented the Balanced Scorecard since they wanted to have a system that could be used at all levels within the organization, this to get an overview and a better control of what is happening within the business. 2.10.4 Hawaiian Case Study Fryzlewicz (2000) carried out a research whose objective was to examine the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to governmental organisations as a potential strategic management tool. The chosen institution as a basis for this study was the Naval Dental Centre in Pearl Harbour (NDCPH) because it had recently been recognised in 1998 for its organizational excellence by receiving the Hawaii State Award of Excellence. The study centred on analysing NDCPH’s mission, vision, key-success factors (KSFs) and performance metrics, for use in developing a proposed Balanced Scorecard framework. This was done by equating the KSFs with Kaplan and Norton’s perspectives and then matching appropriate performance metrics to the KSFs. A Balanced Scorecard framework that followed Kaplan and 58 Norton’s concept was recommended. The potential for adapting this framework to other Naval Dental Centres was also demonstrated. 2.11 Chapter Summary Having reviewed past writings and publications related to the core concepts, applicability and different perspectives of the Balanced Scorecard, as well as literature related tp performance and the conceptual framework, the researcher will now move on to the Methodology. 59 Chapter 3: Methodology 3.1 Introduction This chapter discusses the research methodology and design used to carry out and complete the study. Fisher (2010) defines research methodology as the studying of methods which involves numerous questions, philosophical in nature, concerning possibilities to the researchers in an attempt to ascertain how valid curtained hypothesis are in the process adding to the body of knowledge. The methodology covers the conceptual framework of the research, the research design and techniques used in the analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to ADP as well as to meet the research objectives. The chapter goes on to define the population and sampling method used; the research methods used to collect, present and analyse data are also discussed together with the motivations and justifications for adopting such methods. The research limitations encountered are also explained. The minimal time available for the research (6 months) and the associated limitation of the researcher not being a full time researcher led to the choice of a case study. There are no known studies on the analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to any health institutions in Zimbabwe. This led the researcher to adopt an exploratory research purpose. The research adopted a survey strategy and employed an inductive approach. Interviews eliciting work and service related factors were conducted on a sample of the dental practice’s stakeholders. Participants were selected using a non-random purposive technique. 60 3.2 Research Philosophy The researcher used the interpretivist or phenomonological philosophy, which is based on the belief that reality is socially constructed and that the goal of social science is to understand what meaning people give to that reality (Edwards and Skinner, 2009). This qualitative research paradigm attempts to probe lived experiences of individuals who are being investigated (Saunders, 1982). Saunders et al.(2008) argue that an interpretivist perspective is highly appropriate in the case of business and management research ,particularly in such fields as organizational behavior, marketing and human resources management . Saunders et al. (2008) further argue that the phenomenological research philosophy is useable where the subject is new and when previous studies in the area are limited, as is the case with the current study. The study was carried out from a subjectivist point of view, as the researcher holds the view that management perceptions and decisions will affect strategy and performance. According to Saunders et. al (2009) the subjectivist aspect of ontology “holds that social phenomena are created from the perceptions and consequent actions of those social actors concerned with their existence.” 61 3.3 Research Design The research design provides the glue that holds the research processes together and enables the researcher to address the research questions in ways that are appropriate, efficient and effective, (MANCOSA, 2014). Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2009) proffer that research design is the general plan of how the researcher will go about answering the research questions. The researcher used exploratory research in this study. Saunders, et al., (2009) define exploratory study as a valuable means of finding out “what is happening; to seek new insights; to ask questions and assess phenomena in a new light”. The researcher utilised the exploratory research technique as there is no documented research on the analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard to health institutions in Zimbabwe. 3.3.1 Research Approach and Strategy Owing to the exploratory nature of this research (Robson 2002), the data collection, organisation and analysis will be guided primarily by an inductive approach. The collection, examination and process of continual re-examination of data will determine the research findings. The researcher sought to draw generalizations from data collected. Gray (2009) proffers that the inductive approach starts with the collection of data; the collected data are then analysed to see if any patterns emerge that suggest relationships between variables. The results are then used to formulate generalizations, relationships and even theories. The research was carried out based on a holistic single case study strategy. Robson (2002) defines case study as ‘a strategy for doing research which involves an empirical investigation of a particular contemporary phenomenon within its real life context using multiple sources of evidence’. Yin (2003) also highlights the importance of context, adding that, within a case study, the boundaries between the phenomenon being studied and the context within which it is being studied are not clearly evident. 62 Saunders et. al. (2009) argue that the case study strategy will be of particular interest to the researcher who wishes. to gain a rich understanding of the context of the research and the processes being enacted (Morris and Wood 1991). The case study strategy also has considerable ability to generate answers to the question ‘why?’ as well as the ‘what?’ and ‘how?’ questions. This makes the case study strategy suitable for this exploratory type of study. Cresswell (2014) proffers that case study research is defined as a qualitative approach in which the researcher investigates and explores a real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case) or multiple bound systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information, and reports on it. The unit of analysis in the case study might be multiple cases (a multisite study) or a single case (a within-site case study). It involves extensive research, including documented evidence of a particular issue or situation - symptoms, reactions, effects of certain stimuli, and the conclusion reached following the study. A case study focuses on a particular group of people having something in common. In the case of this research, the people in question all work for the same institution of higher learning. Strengths of the case study strategy • Case study is detailed and richer in bringing out information; and • Involvement of the researcher is intensive. 63 3.4 Study Population and Sample 3.4.1 Study population According to Kothari (2004) all items in any field of inquiry constitute a ‘Universe’ or ‘Population.’ A complete enumeration of all items in the ‘population’ is known as a census inquiry. It can be presumed that in such an inquiry, when all items are covered, no element of chance is left and highest accuracy is obtained. But in practice this may not be true. Even the slightest element of bias in such an inquiry will get larger and larger as the number of observation increases. This type of inquiry involves a great deal of time, money and energy. Therefore, when the field of inquiry is large, this method becomes difficult to adopt because of the resources involved. In this study, the population is all the faith-based health institutions in Zimbabwe, which according to the Zimbabwe Association of Church-related Hospitals (2020), currently stands at 130 hospitals and clinics. 3.4.2 Study sample Many a time it is not possible to examine every item in the population due to constraints of time, money and access (Saunders, 2009). Kothari (2014) proffers that it is usually possible to obtain sufficiently accurate results by studying only a part of the total population. In such cases there would be no utility of census surveys. However, it needs to be emphasised that there is no use in resorting to a sample survey when the universe is a small. In practical life, considerations of time, cost and access when conducting field studies almost invariably lead to a selection of a sub-set of respondents. The respondents selected should be as representative of the total population as possible in order to produce a miniature cross-section (Kothari, 2004). 64 Henry (1990) argues that using sampling makes possible a higher overall accuracy than carrying out a census. This is according to him is because the smaller number of cases for which one would need to collect data would allow more time for other critical activities such as designing and piloting the means of data collection, checking and testing data for accuracy prior to analysis, as well as more resources to higher for example higher qualified research staff or assistants. ADP currently has the following employees and patients listed below. For the purposes of this case study, the researcher opted to approach more than 50% of the possible respondents, to economize on limited time whilst getting an accurate cross-sectional view of ADP. The target sample is also enumerated below. Demographic Classification Current Study sample Percentage Statistics Dentists 3 2 67% Dental Support Staff 2 1 50% Ancillary Support Staff 3 2 67% Non-Employee 2 2 100% 634 159 25% Administrators Patient and patient records Average 62% Table 3.1: Target Sample Statistics 65 The dentists and dental assistants are the frontline, revenue generating workers. The support staff members are the accountant, receptionist and janitor, while the Administrators’ have been classified as non-employee members of the Administrative Committee, the body charged with the oversight and day to day running of the institution. The Administrative committee comprises the senior dentist, the accountant, the receptionist and the two non-employee administrators from the head-office, housed at the same complex as ADP. 66 3.4.3 Sampling Techniques A combination of sampling techniques was employed in the study, as a result of the different groups involved. According to Saunders et. al. (2009) with probability sampling the chance, or probability, of each case being selected from the population is known and is usually equal for all cases. This means that it is possible to answer research questions and to achieve objectives that require you to estimate statistically the characteristics of the population from the sample. For nonprobability samples, the probability of each case being selected from the total population is not known and it is impossible to answer research questions or to address objectives that require you to make statistical inferences about the characteristics of the population. Convenience sampling was used in conjunction with quota sampling to select interviewees from the staff members. Two of the three dentists were interviewed, and care was to be taken to ensure gender balance. Both administrators were interviewed. Of the three support staff members, one manager and one non-manager where selected. According to Saunders et. al.(2009), probability sampling (or representative sampling) is most commonly associated with survey-based research strategies where you need to make inferences from your sample about a population to answer your research question(s) or to meet your objectives. The researcher opted to follow the process recommended by these authors for carrying acquiring a probability sample for the purposes of analysing patient records. The sampling process is divided into four stages: 1) Identify a suitable sampling frame based on your research question(s) or objectives.2) Decide on a suitable sample size. 3) Select the most appropriate sampling technique and select the sample. 4) Check that the sample is representative of the population. 67 The random sampling method chosen for analysing patient cards is the systematic random sampling method. The researcher had to select one out of four records (159 out of 634 patient records). A sampling frame which was a list of all patients was extracted from the AccountingOne Software System, and the patients’ names numbered chronologically from number 1 to number 634. An online random number generator (www.random.org) was used to determine the starting point (Patient 187), and that patient, as well as every fourth patient thereafter was included in the sample, reverting back to the start of the list when I reached the end. The list of 159 patients was then followed, analysing each patients record for key success factors to be considered in the construction of the balanced scorecard. 3.5 Data Collection Techniques According to Saunders et. al (2009), various data collection techniques may be employed and are likely to be used in combination. They may include, for example, interviews, observation, documentary analysis and questionnaires. Consequently, if one is to use a case study strategy one is likely to need to use and triangulate multiple sources of data. This research made use of interviews, document analysis and observation. Saunders et. al. (2009) define triangulation as the use of different data collection techniques within one study in order to ensure that the data are telling you what you think they are telling you. The guides for documentation analysis and the interviews are included in the appendices. 3.5.1 Semi-structured interviews An interview is a purposeful discussion between two or more people (Kahn and Cannell 1957). The use of interviews can help the researcher to gather valid and reliable data that are relevant to the research question(s) and objectives. Interviews can be classified as structured, semi-structured and in-depth (unstructured) interviews. Semi-structured and in-depth interviews are often referred 68 to as ‘qualitative research interviews’ (King 2004). Saunders et. al. (2009) posit that in semistructured interviews the researcher will have a list of themes and questions to be covered, although these may vary from interview to interview. This means that one may omit some questions in particular interviews, given a specific organisational context that is encountered in relation to the research topic. The order of questions may also be varied depending on the flow of the conversation. On the other hand, additional questions may be required to explore the research question and objectives given the nature of events within particular organisations. The nature of the questions and the ensuing discussion mean that data will be recorded by audio-recording the conversation or perhaps note taking. The researcher employed the use of semi-structured interviews in this study. 3.5.2 Content Analysis According to Kothari (2004) content-analysis consists of analysing the contents of documentary materials such as books, magazines, newspapers and the contents of all other verbal materials which can be either spoken or printed. Content-analysis prior to 1940’s was mostly quantitative analysis of documentary materials concerning certain characteristics that can be identified and counted. However, since 1950’s content-analysis is mostly qualitative analysis concerning the general import or message of the existing documents. The researcher employed content analysis to analyse the financial reports, patient cards and other business documents relevant to the study. 3.5.3 Observation Kothari (2004) defines observation as the collection of information by way of investigator’s own observation, without interviewing the respondents. The information obtained relates to what is currently happening and is not complicated by either the past behaviour or future intentions or attitudes of respondents. This method is no doubt an expensive method and the information 69 provided by this method is also very limited, but it may provide insights that may not be discovered by other methods. The researcher will set aside one day to visit ADP and observe operations so as to gain a comprehensive understanding of their operations and this will be combined with the knowledge I gained while working at ADP. 3.6 Data reliability and validity 3.6.1 Reliabilty According to Saunders et. al. (2009), reducing the possibility of getting the answer wrong in research means that attention has to be paid to two particular emphases on research design: reliability and validity. According to Saunders et. al. (2009), reliability refers to the extent to which your data collection techniques or analysis procedures will yield consistent findings. It can be assessed by posing the following three questions (Easterby-Smith et al. 2008:109): 1) Will the measures yield the same results on other occasions? 2) Will similar observations be reached by other observers? 3) Is there transparency in how sense was made from the raw data? 3.6.2 Validity Kothari (2004) posits that validity is the most critical criterion and indicates the degree to which an instrument measures what it is supposed to measure. Validity can also be thought of as utility. In other words, validity is the extent to which differences found with a measuring instrument reflect true differences among those being tested. Robson (2002) proffers four threats to reliability; subject or participant error, subject or participant bias, observer error, and observer bias. The researcher considered the fact that the interviewees might give different answers depending on their mood the day the interview took place. This is referred to as subject or participant error. The researcher does not think this would result in any misleading information for the study since it is based on a number of interviews and buttressed 70 by triangulation. Participant relates to whether the interviewees were sharing their real point of view or will they provide information they are expected to by their immediate supervisors (Lewis et al., 2003). This issue has been solved by guaranteeing anonymity and confidentiality of information submitted. The main purpose of the anonymity is to protect the dental staff and patients or clients. Two other threats to reliability are regarding the observers of the interview. Observer error is the problem that occurs when more than one person performs the interview; different people might elicit different opinions from the interviewees. In addition to this is the observer bias, which is if two or more conduct the interview, there are different ways to interpret the answers (Lewis et al., 2003). This will not affect the current study, as the research is being carried out by an individual researcher. Further to this, the intention is to give feedback to the respondent documenting their input so as to verify intent, content as well as eliminate any misunderstandings. Validity is present when the findings actually support the point or claim. There are some different threats also to validity, one is that the researchers should consider if there has been any special event or changes that have taken place at the research organization that might influence or affect the results (Lewis et al., 2003). There has been an administrative change at Adventist Dental Practice, since the 1st of June 2020, with the appointment of a new director and a new accountant, however this has not borne any operational changes to date, and is therefore not expected to affect the research. The research concerns the functioning of the BSC and its application and therefore includes information covering or affecting several years. When conducting interviews one can increase both the validity and reliability by provide interviewees with information about the interview 71 beforehand (Lewis et al., 2003). Before the interviews with the respondents we sent our questions beforehand to them, to make sure that they had the information that we needed and also to make sure that the interviewees were prepared to answer the questions. 3.6.3 Generalizability Generalizability is an issue that is difficult when it comes to semi-structured interviews (Lewis et al., 2003). The chosen ADP case study cannot be generalized to other settings since this thesis is only based upon this one organization. Thus any generalizations made in this study can only refer to ADP and will need further research to be applicable to other dental clinics and health institutions.. Other issues to be considered are whether the correct information has been obtained as opposed to just the positive aspects of the BSC. Has the appropriate theory been used in the study, and finally, do the conclusions stand-up to the closest scrutiny (Lewis et al., 2003).The few respondents that we interviewed may only give a general reflection of the communication and information paths that are being created with individual employees, and therefore provide an overall impression. 72 3.7 Data analysis techniques and presentation In order to select indicators for BSC, the modified Delphi consensus process was applied using the standard criteria developed by RAND (Marshall et al., 2006). This includes; (i) importance, (ii) scientific soundness (credibility), (iii) appropriateness to clinics’ strategic plan, (iv) feasibility (i.e. whether the measure was available easily as part of management information system, could be collected accurately, reliably, and at a reasonable cost); and (v) modifiability of the clinical outcome measures. Each indicator was rated on a scale of 1-9 for the above criteria. Median scores and measures of disagreement for the whole panel and individual ratings were discussed, in subsequent meetings. Panel members were given an opportunity to change their ratings after the discussions. Indicators receiving final scores of 7-9 were regarded as robust, 4-6 as equivocal, and 1-3 as weak. All indicators receiving scores of 7 or more (face validity) were included in the final set. In addition, a small number of indicators which received scores of 4-6 were retained if the panelists considered the indicators essential to contribute to the overall balance and comprehensiveness of the final set. The indicators (receiving a median score of 7 or more) were finally selected and organized into the four BSC quadrants. Qualitative ’content analysis’ was done. It is a well-developed and widely used method in social sciences with an established pedigree (Dixon-Woods et al., 2005). Data abstraction, emphasizing actual communications (manifest content), descriptions and interpretations on a higher logical level (latent content) with the creation of codes, categories and themes was done. For the key informant interviews the unit of analysis was the interview text and for participant observation the meeting diary. As a next step descriptive codes were abbreviated on the left-hand margin of the interview text. A short sheet was then prepared that listed page numbers devoted to particular items, which later 73 became subheadings in the text. Once the interviews and observation diary were coded, a simple storage and retrieval system was designed in QSR Nvivo software 2.0 so that researchers could easily locate relevant items of information, each in a separate folder. Triangulation of methods gives multiple perceptions which can clarify meaning and verifies the repeatability of observations (Stake, 2005). Reflections and reporting based on both field notes from participant observation studies and other empirical data such as interviews is emphasized in ethnographic studies (Palsson, 2007). All sources of evidence (content analysis, participant observation and key informant interviews) were reviewed by the researcher. Data was analyzed together, so that the case study findings were based on convergence of information from these three sources. Unclear responses and contradictory reports obtained during key informant interviews were checked with participant observation text and by sharing draft notes with key informants. Moving between these two venues (interviews and observations) allowed for frequent independent reflection and then discussions with other involved project members. The evolution of discrete themes could therefore be explored and either confirmed or refuted. Themes were only retained when more than 50% of respondents described the same items in key informant interviews and then the same was confirmed by analysis of participant observation texts. Findings from quantitative surveys were also consulted to highlight the cultural context of BSC implementation. 3.8 Ethical considerations The study was submitted and approved by the medical director. Institutional consent and support was a part of this project throughout the execution of the study. The study subjects were institutional employees (administrators and staff) as well as patients. 74 Participation in survey and interviews was purely voluntary and without any monetary compensation. There were several queries on the purpose and institutional utility of this project however no refusals to consent to the key informant interviews were or to be observed were noted. Interviewees had the right to skip any question they did not wish to answer or to withdraw from the interview at any point. Interview transcripts were shared with interviewees before coding for the purpose of qualitative analysis. Some individual participants were reluctant to contribute occasionally. Reassurance was therefore required from time to time to clarify that survey and interview data will only report analysis and their personal identity or clinical unit affiliation will not be revealed. This shows the importance of periodic sensitization to the objectives of the study and highlights challenges of conducting research in one’s own organization or former organization of employment. 3.9 Chapter summary Having looked at the research plan and analysis procedure covering content analysis, interviews and observation, together with issues pertaining to reliability and validity, the researcher will now go on to document the actual research findings. 75 Chapter 4: Data Presentation and Analysis 4.1 Introduction This chapter focuses on presentation techniques, interpretation and discussion of research findings. 4.2 Feasibility of BSC Implementation In LICs Using the specified search terms and review methodology, 32 articles were found to be of direct relevance. Of these 26 were actual descriptions (case studies) of BSC implementation in various health care settings, one was a review (Zelman et al., 2003) and 5 were related to BSC design and principles. There were 174 articles which do not report using a formal BSC but use tools, performance measurement techniques and indicators quite similar to the BSC framework. Most common themes were centered on quality of care initiatives and organizational management. The majority (135) of these articles were from HICs while the remaining 39 were based on experience and context of LICs. The latter provided information for commentary while comparing experience of BSC in HIC against contextual realities of LIC. It was found that use of BSC is spread over a broad range of health care settings with great diversity and concentrated in the HICs (United States mainly). Besides its application for strategic management it appears that these health care organizations have used BSC for public information, clinical pathways, hospital department performance, women’s quality of care, outcome measurement, managed care evaluation and performance measurement of a consortia of hospitals (Inamdar et al., 2000; Jones and Filip, 2000; Zelman et al., 2003). The traditional four perspectives of BSC were thus quite amenable to modification. Most of the organizations that used BSC report an improvement in all four traditional quadrants of BSC. Two large scale health sector applications of the BSC were found for acute care hospitals in Ontario Canada and critical access 76 hospitals in the US (Zelman et al., 2003). A third dimension of NHS Trust hospitals UK was added to this in order to enhance the body of evidence. Although all three applications are based on theory and concepts of BSC, they are different in their approaches and thus make an interesting comparison and contrast. Using the criteria developed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) for improving quality of services in low and middle-income countries (NCQA, 2006), the researcher contextualized application of BSC in LICs (Table 5). 77 Analytical framework for translating BSC experience from high to low income settings PARAMETERS Benefits COMMENTARY BSC has resulted in improved and effective health care in HIC. Interest, ability to report, respond and compliance to performance measurement is however questionable in LIC. Feasibility In HIC basic requirement for BSC implementation turned out to be infrastructure for valid, comprehensive and timely information system. This is currently lacking /of low quality in LIC Objectivity BSC was designed in HIC using established guidelines and strategic plans. This shows that BSC has a basis in science not in individual judgement. However most LIC do not have operational strategic planning in place Cost-effectiveness BSC has been applied in HIC at a single health outlet or a larger health system with minimal training and input. Even then the issue of costs is a major constraint in under-resourced systems. Sustainability BSC was designed by program staff themselves in HIC based on needs. However accountability systems are weak in LIC and sustainability may be an issue Table 4.1: Analytical Framework for translating BSc experience from HI to LI settings Adapted from: NCQA recognition model on quality assessment and improvement in low and middleincome countries Source: Hibbard et al., 2005; Langenbrunner and Liu, 2005; McIntyre et al., 2001; McNamara, 2006; Mehrotra et al., 2003; Siddiqi et al., 2005; Smits et al., 2002; Unger et al., 2003; Bhat, 1996; Bourne 2000; Grol, 2001; Brown et al., 2001; Nandraj et al., 2001 Any direct evidence describing BSC use in a low-income health care setting or why such an implementation is hindered or how it could be facilitated was not available at the time of this systematic review. The articles that described BSC use in HICs were all individual case studies and not designed to evaluate BSC outcomes. Regarding experience of using BSC in HICs, it was observed that theory and concepts of BSC have been applied among all types of health care organizations and on a large scale. Committed leadership, quality information systems, viable strategic plans, and optimum resources emerged as required prerequisites for BSC 78 implementation. It is however to be noted that even within LICs there are pockets of relatively less deprivation where the required BSC prerequisites may be fulfilled. Cautious implications for BSC adaptability in LICs however need to be drawn. An organizational cultural assessment must precede BSC implementation 4.3 Use of existing data in designing BSC In the initiative towards BSC design, data which are routinely collected by ADP were used in to develop an integrated core of 20 indicators. Despite few measurement issues related to comparability across various settings, many indicators in were similar to the ones shortlisted in HICs (Baker and Pink, 1995). Other studies have also used existing documents to create effective Balanced Scorecards by using similar criteria (Idänpään-Heikkilä etal., 2006; Marshall et al., 2006; McLoughlin et al., 2006). The Afghanistan study (Peters et al., 2007) shortlisted 29 indicators for the BSC including domains of patient and community, staff, capacity for service, service provision, financial system and overall vision. Despite contextual differences similarity can be drawn among indicators shortlisted those that were identified in Canadian dental clinics (Schalm, 2008). 79 4.4 Depth Interview Feedback The researcher will now proceed to document the feedback from the depth interviews, by beginning with a tabular summary. Of the planned 9 interviews, the researcher was only able to carry out 7 face to face interviews due to the unavailability of prospective interview respondents within the limited time (3 administrators and 4 staff members). Demographics Factor A B C D Gender Male: 3 Female: 4 Age Below 40 yrs: 3 Above 40 yrs: 4 Qualification None: 1 Diploma: 2 Degree/s: 4 Position Dentist: 2 Dental Assistant: 1 Support staff: 2 Administrator: 2 Tenure at ADP Less than 1 yr: 2 1-3yrs: 2 3-5yrs: 1 More than 5 yrs: 2 Table 4.2: Demographic Analysis of Respondents Interview Feedback Interview Question/Area Constructive What would you describe as the critical success factors for ADP? 7 In what way is performance measurement carried out at ADP? 5 2 4 3 What resources if any, can be allocated for BSC implementation 5 2 How do you expect the implementation of the BSC to affect the clinic’s staff and operations? 7 How is the BSC different from what performance measurement systems already existed in your clinical clinic? What might helped or hinder the BSC implementation activities in your clinic? Unconstructive 7 Table 4.3: Analysis of interview feedback 80 Only 2 finance related personnel had an understanding of the Balanced Scorecard prior to the researcher explaining the concept, leading to constructive feedback on most interview pointers. Initially 37 critical success factors were listed from feedback from respondents, and these where short-listed to the 20 used in the proposed Balanced Scorecard. Performance measurement and management is weak under the current setup, with the management practice only being carried out on average once every three years hence there is need to improve the current performance management culture. ADP has sufficient financial resources, as they have posted profits for the two previous financial periods (2018 and 2019) and are sufficiently liquid, and the necessary budgetary flexibility. A consultant may need to hired on a contract basis to oversee the technical aspects of the implementation, as evinced by four of the interview respondents. The BSC is expected to improve operations at ADP, resulting in higher liquidity, revenue, less expenses, higher customer and employee satisfaction as well as a better ADP reputation. Management also anticipate that they will have more practical knowledge following a system reorganisation based on the intended BSC implementation. However, three respondents felt BSC would result in more work for employees, with many feeling strained already under the current load. 81 4.5 Designing the BSC Using Formal Consensus Technique An expert multidisciplinary panel was involved in selecting indicators and designing the BSC. A modified Delphi Group Technique was used to reach consensus about indicators for an institutional level BSC. Following an extensive review of existing internal documents (periodical quality assurance, patient and employee satisfaction surveys and financial reports), a preliminary list of 50 indicators was formulated in line with dental practices strategic plan. No indicators were removed from consideration at this phase of the activity. The next step was to prioritize key performance indicators based on the criteria described under the Data Analysis section. The panel used the modified Delphi technique during face to face meetings to individually rate each indicator on a scale of 1–9 for the above criteria. All criteria were given equal weightage. Twenty indicators (receiving a median score of 7 or more) were finally selected (see the following table.) . These indicators were distributed across all 4 quadrants of BSC: financial perspective (n=4), internal business (n=7), human resource perspective (n=4) and patient satisfaction perspective (n=5). 82 Shortlisted List of Indicators for the ADP Balanced Scorecard. INDICATORS Financial Perspective (FP) • Annual Patient Value • Length of procedure • Daily census • Net operating margin • Overall FP Median Median 8.00 7.00 8.00 9.00 8.00 Internal Business Perspective (IBP): Clinical Outcomes (efficiency and quality) Denture and crown delivery time • Percentage of new patients • Avoidable patient revisits • Incidence of drug reactions • Nosocomial infection • Dental procedure injuries • Overall IBP Median Human Resource Perspective (HRP) 8.00 8.00 7.00 7.00 8.00 8.00 • Satisfaction with job • Satisfaction with colleagues • Satisfaction with dental facilities • Satisfaction with organization • Annual Production per full time employee • Overall HRP Median Patient Satisfaction Perspective (PSP) 8.00 7.00 8.00 8.00 7.00 7.00 • • • • • • • 7.40 Satisfaction with dentists Patient Complaints Satisfaction with reception and support services 7.00 8.00 7.00 Satisfaction with dental assistants’ services Proportion of patients recommending ADP to their families and friends Overall PSP Median 7.40 7.00 8.00 Table 4.4: Shortlisted List of Indicators for the ADP Balanced Scorecard 83 4.6 Summary of Results BSC compels individual clinicians and managers to jointly work towards improving performance. The Delphi group process led to a pragmatic interpretation of existing data resulting in the design of a scorecard with comprehensive indicators in multiple dimensions. A need for stringent definitions, international benchmarking and standardized measurement methods was identified. This scorecard is now ready to be implemented by this hospital as a performance management tool, subject to a culture study, to determine the appropriateness of the timing of the implementation. 84 Chapter 5: Conclusion and Recommendations 5.1 Introduction In this section, the researcher will interpret the meaning of the research results, showing the link between the results and the literature review, showing the points of similarity and departures with theory and previous research findings on the topic. 5.2 Summary of Findings 5.2.1 Feasibility of BSC in the HICs The study demonstrates increasing use of BSC in HICs. It was observed that the theory and concepts of the BSC have been applied among all types of healthcare organizations and on a large scale. The systematic review showed that BSC promoted integration and facilitation of clinical, operational and financial indicators in HICs with greater employee motivation and patient satisfaction, which is a goal that health care organizations in both HICs and LICs are today aiming for. The Campania Regional Government applied the BSC and was successful in overcoming the surmounting deficit incurred within the region’s health services (Impagliazzo et al., 2009). These studies complement the findings from this study , emphasizing that BSC application must be adapted to suit specific organizational contexts (Guifang, 2009). Hospitals initially used the BSC to avoid barriers such as financial pressure however BSC has since evolved to achieve the mission and vision of the organization as well (Schalm, 2008). 5.2.2 Feasibility of BSC in LIC settings Despite the positive outcomes demonstrated in the HICs, caution was warranted in the use of BSC within the LIC health care settings. This caution is supported by the realities of health care systems in LICs and LMIC settings. In terms of health care financing, these countries spend less than US$ 85 34 per capita annually on health, and are marked by weak governance, bureaucratic culture and lack of accountability mechanisms (Nishtar, 2009; Siddiqi et al., 2009). Compliance to PM and maintaining quality information systems (requirement for effective BSC) can therefore be only partially feasible. Moreover, lack of accountability impairs sustainability of initiatives such as the BSC. Health delivery systems lack quality and strategic planning due to which objectivity of the BSC will remain a challenge. Also, with poor central government spending on health and constrained resources, cost- effectiveness of BSC is an issue. At the time when the current study was conducted no studies of BSC application in the context of LICs could be identified. An experience of using BSC has now been documented from Afghanistan where BSC has been applied at a national (macro) level by the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) to demonstrate how provinces and the country are doing in delivering the basic package of health services (Peters et al., 2007). In the absence of a routine system to collect information on health services, the MOPH chose to initiate a program to monitor health services through household surveys and annual surveys of health facilities. There were obstacles to developing a BSC based on surveys, including the lack of a sampling frame, insecurity, bad roads and poor communications etc. Once operational, the BSC proved to be a useful tool to summarize the multidimensional nature of health services and enabled managers to benchmark performance and identify strengths and weaknesses in the Afghan context. Recently, in a Chinese hospital, BSC was integrated with an incentive plan in the nursing field resulting in improved performance (Chu, 2009). These examples further support findings from the current study. Due consideration to variable levels of feasibility is required while implementing BSC in LICs. It is to be mentioned that prior to launching the BSC it was anticipated that most of the desired prerequisites for BSC implementation i.e willingness of leadership, presence of good quality information systems, 86 functional strategic plan and optimal resources are in place in ADP. Therefore, the current study used the current information data base to design the BSC and study IV was rolled-out as an implementation case study of BSC. 5.2.3 Paucity of Analytical Studies On BSC in Health Care It can be seen from the systematic review in that BSC experience has mostly been described as case studies in health care. There is uncertainty not only about the effectiveness of BSC but also how to evaluate such effectiveness. In health care the effectiveness of clinical interventions is assessed on the basis of evidence from experimental studies and randomized clinical trials (the ‘gold standard’) as called for in 1972 by Archie Cochrane (Cochrane and Silagy,1999). This evidence-based approach however does not neatly fit current state of maturity in management research (Thor, 2007). This is so because the methodological orientation in health care management seeks to unpack the mechanism of how complex programmes work (or why they fail) in particular contexts and settings (Pawson et al., 2005). Therefore, the implementation of evidence based practice in health care management is unlikely simply to follow the established clinical model (Walshe and Rundall, 2001). Moreover, studies reveal that no coordinated effort has been undertaken to conduct and periodically update systematic reviews for healthcare managers and policy makers (Lavis et al., 2005). Little if any attempt has been made to adapt existing reviews for enhancing their local applicability (Lavis et al.,2006). Despite the nature of qualitative data available, the current study blended features common to systematic reviews (Pai et al., 2004) with interpretative data analysis and synthesis while reporting experience of BSC use in HICs and its applicability in the LIC context. 87 5.2.4 Indicator Selection and Measurement Issues It is to be mentioned that the primary search for indicators was not exhaustive in since the starting point was limited by data which were already being collected by ADP, as well as feedback from interview respondents. These indicators were relevant to ongoing management processes in finance, marketing, and human resource departments of the study hospital and to the current hospital quality accreditation plans. However, certain valuable and relevant indicators for the BSC may have been overlooked or were not available. Besides the indicators shortlisted in this study, BSCs in other settings have come up with more sophisticated indicators on survival rates and age, sex and disease- specific mortality and morbidity ratios etc (Robinson et al., 2003; Schalm, 2008; ten Asbroek et al., 2004; Wachtel et al., 1999). The BSC developed in this setting did not have some of these more analytical indicators. Such lack of in-depth outcome data has been listed elsewhere as a BSC implementation challenge (Schalm, 2008). On the other hand many of the current indicators in the internal business quadrant of the BSC are driven by the need to collect data for accreditation at this clinic (ADP). Besides the issue of completeness of the data sets, the results from this investigation also reflect limitations of routinely collected data. Certain indicators selected for BSC had relatively lower face validity as assessed by their median ratings. This was mainly due to lack of standardized definitions and measurement techniques, reliable instruments, adequate sample sizes and response rates etc. Other studies (Baker and Pink, 1995; Zeitlin et al., 2003) have also noted that methodological shortcomings of many indicators have generated skepticism about the data sources, consistency of reporting, derivation of the numbers and their usefulness in offering analogous estimates. However, starting with the search of more sophisticated and comprehensive indicators would have required more efforts, time, and resources and was simply not feasible within the scope of this study. Due to restricted resources and capacities in LICs it has already been recommended that only a limited set of indicators should be selected (Larson and Mercer, 88 2004). Relying on existing information system and using standard steps of Delphi technique, this BSC with 20 indicators was derived. As such this is a preliminary step towards defining a more inclusive and comparable set of indicators for use across LIC and HIC hospital settings. Other studies while selecting regionally comparable indicators, have given the criterion ‘feasibility’ a lesser weightage. This is because limited information about data sets in other countries is available (Mc Loughlin et al., 2006). Since the BSC indicators in this study were derived specifically for the study clinic from already ongoing information system, ‘feasibility’ of acquiring the information was not an issue in this study. An equal weightage was thus given to all criteria while short listing indicators for the study. 89 5.3 Conclusions In this thesis I have set out to contribute to the limited body of empirical evidence about the use and applicability of the Balanced Scorecard in a LIC dental setting. It has been explored how HICs have used the BSC for improved performance management and how the experience can be transferred to the context of LICs. Importance of organizational culture and leadership in initiating and implementing the BSC has been emphasized. I have pointed out the value of a multidisciplinary panel in selecting indicators for BSC using formal consensus methods. Moreover the case has been argued for using existing dental clinic data to select indicators for the BSC, despite the inherent limitations of data quality management in LICs. The key conclusions from this thesis are: Direct evidence describing BSC use in a LIC health care setting or why such an implementation is hindered or how it could be facilitated has not been demonstrated Delphi process is useful in selecting indicators for BSC with consensus. Measurement issues related to indicators pose a methodological challenge. Committed leadership, quality information systems, participatory culture and multidisciplinary team approaches can enhance feasibility of BSC implementation 90 5.4 Recommendations of the Study Studies show that BSC implementation is usually unsuccessful where the concept is not communicated properly. It is recommended that extensive training courses be conducted to spread the awareness of BSC. Kaplan and Norton (2001a) and Hao et al. (2012) suggest using multiple communication tools to ensure that employees get the right message i.e. quarterly town meetings, brochures, monthly newsletters, education programs, and company intranet. It is recommended that all of these means of communication are used at KFSH. Further, Mooraj et al. (1999) suggest that organisations should apply a combination of top-down and bottom-up communication strategies to implement BSC and to ensure the involvement of the full organisation. It is also recommended that the importance of external stakeholders is considered by including them in the communication loop. 5.5 Limitations of the study 5.5.1 Challenges of doing research in one’s own organization The author of this study subject is a former employee of the same organization, having only been transferred in May 2020. This has the potential of introducing an observation bias and affecting team dynamics. It is possible that some respondents showed greater enthusiasm because of the presence of the researcher (Hawthorne effect). Influence of the Hawthorne effect seems unlikely to have affected results were corroborated by interviews and document analysis to increase the objectivity and neutrality of results. Similar strategies to decrease the effect of observer on study participants have been described by Pettigrew (Pettigrew, 1999). There is a paucity of literature on the hurdles that employees face while using their own organization as the study site. Some of the challenges that were encountered in the study were the ethical concerns on part of a few staff members about the anonymity and confidentiality of their views with regards to their unit’s/department’s leadership as the author of this thesis was also 91 working in the same organization. Other studies have pointed out that in relationships within an organization subordinates usually have to encounter certain repercussions from their supervisor if their views about the leader are openly expressed (Coghlan and Brannick, 2001a). It has been reported elsewhere that combining action research role with regular organizational assignments creates a role duality and measures need to be taken to reduce the observation bias (Coghlan and Casey 2001b; Sellgren, 2007b). 92 5.5.2 Limitation of Study Questionnaire Questionnaires have limitations. The main limitation is that they rely on perceptions of the individuals (Arvonen, 2002). Another concern is that these questionnaires do not measure real behavior, just the attitude of the employees about their organization and leadership. The study participants were well conversant in English. However the questionnaire was not pretested due to time constraints. Despite these measures, cautious interpretation of results is important as the questionnaire was not locally validated. 5.5.3 Generalizability The study recognized that Zimbabwe does not have a national medical institution database. Therefore, the indicators developed for BSC in this hospital cannot be necessarily applicable to other dental settings in Zimbabwe. However there are several studies on BSC (described above) which came up with similar set of indicators using a consensus process. Overall generalizability of this study to other private or faith-based clinic settings within and outside Zimbabwe should be carefully interpreted as the study is based ADP data only. However, it seems feasible that findings could apply to dental clinics which are similar to ADP. At least three other dental facilities in Bulawayo are comparable to the study clinic in terms of dental facilities and information technology infrastructure. Additional research is warranted to further develop the contextual understanding of BSC design and broaden the evidence base generated through this study. 93 5.6 Recommendation for further studies The current study concluded that committed leadership, participatory culture, quality information systems, viable strategic plans, and optimum resources are essential prerequisites for BSC implementation. These issues will need to be looked at in-depth before the BSC can be implemented successfully. The study identified organizational culture assessment as a key prerequisite prior to BSC application. Other studies also recommend that prior to rolling the BSC an assessment of ‘strategic readiness’ be conducted because success of BSC implementation will ultimately depend on the culture of the organization being appropriate and receptive (Kaplan and Norton, 2004; Schalm, 2008). Rabbani (2010) identified organizational culture assessment as a key prerequisite prior to BSC application. Other studies also recommend that prior to rolling the BSC an assessment of ‘strategic readiness’ be conducted because success of BSC implementation will ultimately depend on the culture of the organization being appropriate and receptive (Kaplan and Norton, 2004; Schalm, 2008). Rabbani (2010) goes on to futher advocate that wise process and takes more time to manifest. It is advocated that multiple cycles of BSC execution are required for its complete implementation (Quality Insights of Pennsylvania, 2009). No conclusions on BSC effectiveness in bringing about a change in the indicators can be drawn from this thesis. 94 References 1. Asiedu E (2015). Developing Market as a Source of Competitive Advantage. The Role of Management Tools. Elixir Int. J. Manage. Arts 88:36319-36320 2. Bair S. (2011), Speeches and testimony, Federal Deposit Insurance, Corporation 3. Baker, G.R., Macintosh-Murray, A., Porcellato, C., Dionne, L., Stelmacovich, K., & Born, K. (2008). "Jönköping County Council." High Performing Healthcare Systems: Delivering Quality by Design. 121-144. Toronto: Longwoods Publishing. 4. Baker, G.R. & Pink, G.H. (1995) 'A balanced scorecard for Canadian hospitals', Healthcare Management Forum, 8, 7-21. 5. Campbell, S.M., Braspenning, J., Hutchinson, A. & Marshall, M. (2002) 'Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care'. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 11, 358-364. 6. Chen S, Yang C, Shiau J (2006). The application of the Balanced Scorecard in performance evaluation of higher education. TQM Magazine Journal. 18(2):190–205. 7. Choong K. K. (2013). Understanding the features of performance measurement system: a literature review. Measuring Business Excellence. Vol. 17 (4), p. 102-121. https://doi.org/10.1108/MBE-05-2012-0031 8. Christauskas Č., Kazlauskienė V. (2009). Modernių veiklos vertinimo sistemų įtaka įmonės valdymui globalizacijos laikotarpiu. Ekonomika ir vadyba. Nr. 14, p. 715-722. Retrieved from: http://verslokelias.eu/resursu_katalogas/content/article/kitos20publikacijos/220kitos20publi kacijos20nr204.pdf 9. Creswell J.W., (2014) Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE 10. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited(2019), 2019 Global health care outlook 95 11. De Toni A. and Tonchia S. (2001). Performance measurement systems – Models, characteristics and measures. International Journal of Operations & Production Management. Vol. 21 (1/2), p. 46-71. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570110358459 12. Dixon-Woods, M., Agarwal, S., Jones, D., Young, B. & Sutton, A. (2005) 'Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods'. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 10, 45-53. 13. Dorweiler VP, Yakhou M (2005). Scorecard for academic administration performance on the campus. Managerial Auditing Journal. 20(2):138–144. 14. Edwards Stephanie and Technical Services Team, Balanced Scorecard S Topic Gateway Series No. 2, CIMA, 2006 15. Feigenbaum, A.V. (1991) Quality Control. 3rd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York. 16. Fisher, C (2010) Researching and Writing a Dissertation: An Essential Guide for Business Students, Pearson Education, Harlow, England. 17. Fryzlewicz J., Analysis of measures of performance and continuous improvement at the Naval Dental Centre, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Naval Post-Graduate School, Monterey, California 18. Gibbons, R., and Kaplan R. S., 2015. "Formal Measures in Informal Management: Can a Balanced Scorecard Change a Culture?" American Economic Review, 105 (5): 447-51. 19. Gray,D.E (2009) Doing Research in the Real World, University of Surrey, SAGE Publications, Second Edition. 20. Griffith J.R., Reengineering health care: Management Systems for survivors, Hospital and Health Administration , 39, 451- 470 21. Gustafsson K., Schold C., Sihvo C. Summitt S. (2009), Application of the Balanced Scorecard in the health care department within the Jonkoping County Council, Unpublished thesis, Jonkoping International Business School, Jonkoping University, Sweden 96 22. Hansen, E.G., & Schaltegger, S. (2012). Pursuing Sustainability With The Balanced Scorecard: Between Shareholder Value And Multiple Goal Optimisation. Working Paper. Luneburg, Germany: Centre For Sustainability Management (CSM), Leuphana University Of Luneburg. 23. Hartwig K., Pashman J., Cherlin E., Dale M., Callaway M., Czaplinski C.,Wood W. E., Abebe Y., Dentry T. & Bradley E. H., (2008), Hospital management in the context of health sector reform: a planning model in Ethiopia, The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 23, 203 – 218 24. Henry, G.T. (1990) Practical Sampling. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. 25. Huang, H.-C. (2009). Designing a knowledge-based system for strategic planning: A balanced scorecard perspective. Expert Systems with Applications, 36, 209-218. 26. Institute of Medicine (1999). Leading Health Indicators for Healthy People 2010:Final Report.. Washington, DC. National Academies Press. 27. Juran J.M. (2004), Architect of Quality, New York: McGraw-Hill 28. Kahn, R. and Cannell, C. (1957) The Dynamics of Interviewing. New York and Chichester: Wiley. 29. Kaplan RS, Norton DP (1992). The Balanced Scorecard: Measures that drive performance. Harvard business review. 70(1):71-79. 30. Kaplan RS, Norton DS. The Balanced Scorecard. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1996. 31. Kaplan, Robert S, "Conceptual Foundations of the Balanced Scorecard1", Working Paper, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, 2010. 32. Kaplan, Robert S, "Conceptual Foundations of the Balanced Scorecard1", Working Paper, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, 2010. 33. Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (2005). The balanced scorecard: measures that drive performance. Harvard business review, 83(7), 172. 97 34. Khomba JK, Vermaak FNS, Hanif (2012). Relevance of the balanced scorecard model in Africa: Shareholder-centred or stakeholder-centred? J. Bus. Manage. 6(17):5773-5785 35. Kim J, Suh E, Hwang H (2003). Model for evaluating the effectiveness of CRM using the balanced scorecard. J. Interactive Market. 17(2):5-19. 36. King, N. (2004) ‘Using templates in the thematic analysis of text’, in C. Cassell and G. Symon (eds), Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. London: Sage, pp. 256–70. 37. Klovienė L. (2012). Veiklos vertinimo sistemos adekvatumas verslo aplinkai: daktaro disertacijos santrauka. Kaunas: Kauno technologijos universitetas, Socialiniai mokslai, Vadyba ir administravimas. 38. Kothari C.R. (2004) Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques, New Age, Second Edition 39. Kotler P. and Caslione J.A. (2009), Chaotics: The Business of Managing and Marketing in the Age of Turbulence. New York : AMACOMLee N (2006). Measuring the performance of public sector organisations: A case study on Public Schools in Malaysia. Measuring Business Excellence 10(4):50-64. 40. Krylov S. I. (2016), Balanced Scorecard Concept Development Analysis, Department of Accounting, Analysis and Audit, Ural Federal University, Russian Federation 41. Lewis, P., Saunders, M., & Thornhill, A. (2003). Research Methods for Business Students 3rd ed, Spain: Pearson Education Limited. 42. Love P, Holt G (2000). Construction Business performance: The S P M alternative. Business Process Manage. J. 6(5):408-416. 43. Management College of Southern Africa 44. Marshall, M., Klazinga, N., Leatherman, S., Hardy, C., Bergmann, E., Pisco, L., Mattke, S. & Mainz, J. (2006) 'OECD Health Care Quality Indicator Project. The expert panel on 98 primary care prevention and health promotion'. International Journal of Quality in Health Care, 18:Supplement 1, 21-25. 45. McBurney, D. (2001) Research methods. Wadsworth Thomson Learning Belmont, CA: Stamford, USA. 46. McNair CJ, Lynch RL, Cross KF (1990). Do financial and non-financial measures have to agree? Manage. Account, pp.28-36. 47. Medical and Dental Practitioner’s Council of Zimbabwe, Registered Doctors, http://www.mdpcz.co.zw/mdpcz_find/_f/_find_practitioner.php 48. Ministry of Health Sri Lanka and Japan International Cooperation Agency (2003), Master plan study for the strengthening of health system in the democratic socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, supporting document I, situation analysis, healthy and Shining Island in the 21st Century, final report, Pacific Consultants International: Columbo 49. Modell, S. (2012), “The politics of the balanced scorecard”, Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 475-489. 50. Murphy, M.K., Black, N.A., Lamping, D.L., McKee, C.M., Sanderson, C.F., Askham, J. & Marteau, T. (1998) 'Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development'. Health Technology Assessment, 2, 1-88. 51. Mutale W, Stringer J, Chintu N, Chilengi R, Mwanamwenge MT, et al. (2014) Application of Balanced Scorecard in the Evaluation of a Complex Health System Intervention: 12 Months Post Intervention Findings from the BHOMA Intervention: A Cluster Randomised Trial in Zambia. PLoS ONE 9(4): e93977. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093977 52. Najmi M., Kehoe D. F. (2001). The role of performance measurement system in promoting quality development beyond ISO 9000. International Journal of Operations & Production Management. Vol. 21 (1/2), p. 159-172, https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570110358512 99 53. Narkunienė J., Ulbinaitė A. (2018),Comparative Analysis Of Company Performance Evaluation Methods, The International Journal Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, ISSN 2345-0282 (online) http://jssidoi.org/jesi/ 54. Neely A., Adams C., Kennerley M. (2002). The performance prism: the scorecard for measuring and managing business success. Financial Times Series. Financial Times/Prentice Hall 55. Nordberg, D. (2008). Corporate governance principles and Issues. London: Sage 56. Palsson, H. (2007) 'Participant observation in logistics research'. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 37, 148-163. 57. Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL (1986). SERVQUAL: A multi-item scale for measuring customer perception of service quality. J. Retailing. 64 (1):12-40. 58. Peleckis K., Krutinis M., Slavinskaitė N. (2013). Daugiakriterinis alkoholio pramonės įmonių pagrindinės veiklos efektyvumo vertinimas. [Multivariate assessment of the main activities of the alcohol industry], Verslo ir teisės aktualijos. Nr. 8, p. 1 – 16. https://doi.org/10.5200/1822-9530.2013.1 59. Peters D.H., Noor A. A., Singh L.P., Kakar F.K., Hansen P.M., & Burnham G., (2007), A balanced scorecard for health services in Afghanistan, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85, 146 – 151. 60. Peters D. H., Noor A. A.,Singh L. P., Kakar F. K., Hansen P. M. & Burnham G., A Balanced Score Card for Health Services Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, March 2007, p. 147-151 61. Punniyamoorthy M, Murali R (2008). Balanced scorecard for the balanced scorecard: A benchmarking tool. Benchmarking Journal. 15(4):420-443. 62. Rabbani F.(2010), Science and Practice of a Balanced Scorecard in a hospital in Pakistan, Feasibility, Context, Design and Implementation, Karolinska Intitutet, Stockholm, Sweden 100 63. Rigby, D. and Bilodeau, B. (2011), Management Tools and Trends: 2011, Bain&Co, Boston, MA. 64. Samir Ghosh, Subrata Mukherjee. Measurement of Corporate performance through balanced scorecard: An overview. Vidyasagar University Journal of CommerceVol. 11, March 2006, p. 64-67. 65. Saunders M., Lewis P. and Thornhill A (2009), Research Methods for Business Students, Prentice Hall, Pearson Education, Harlow, England, Fifth Edition, 66. Schalm, C. (2008) 'Implementing a balanced scorecard as a strategic management tool in a long-term care organization'. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 13:Supplement 1, 8-14. 67. Schneiderman M. (1999), Why Balanced Scored Cards Fail, Journal of Strategic Performance Measurement, January 1999 68. Senyoni W (2019), Scorecards can help measure health outcomes. An East Africa case study: https://theconversation.com/scorecards-can-help-measure-health-outcom... 69. Siddiqui A. A., Mirza A. A., Mian R.I., Alshammari A. And Alsalwah N. (2017), Dental Treatment: Patients’ Expectations, Satisfaction Dentist Behavior, International Journal Of Current Advanced Research, Volume 6; Issue 11; November 2017 70. Sigalas C. (2015), Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 11(4): 546-572. DOI: 10.1108/JAOC-03-2014-0024 71. Soutar G, Mc Neil M (1996). Measuring service quality in a tertiary Institution. J. Educ. Admin. 34(1):72-82. 72. Stake, R.E. (2005) 'Qualitative case studies', in N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (eds.) The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 3rd edn. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks. 73. Teklehaimanot H.D., Teklehaimanot A, Tedella A.A., and Abdella M. (2016), Use of Balanced Scorecard Methodology for Performance Measurement of the Health Extension Program in Ethiopia, The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 101 74. Ten Asbroek AH, Arah OA, Geelhoed J, Custers T, Delnoij DM, Klazinga NS (2004), Developing a national performance indicator framework for the Dutch heath system. Int J Qual Health Care;16(Suppl 1):i65-71. 75. Thunaian S.A. A.(2013), Exploring The Use Of The Balanced Scorecard (BSC) In The Healthcare Sector Of The Kingdom Of Saudi Arabia: Rhetoric And Reality, School of Management, University of Bradford, UK 76. Travis P., Bennet S., Heinnes A., Pang T., Bhutta Z, Hyder A., Pielemeier N. R., Mills A., Evans T. (2004), Overcoming health-system constraints to achieve, Millenium Development Goals, The Lancet 364, 900 - 906 77. Topazio N. (2014), CGMA Briefing - Integrated Thinking 78. Wongrassamee S, Gardner PD, Simmons GEL (2003).Performance Measuring Tools: The Balanced scorecard and the EFQM Excellence Model. Measuring Business Excellence. 7(1):14-29. 79. Woodward G., Manuel D., Goel V.(2004), Developing a Balanced Scorecard for Public Health, ICES Investigative Report, Toronto ICES, www.ices.on.ca/file/scorecard_report_final.pdf 80. World Bank Data Team (2019), https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country- classifications-income-level-2019-2020 81. World Health Organisation, Oral Health services; https://www.who.int/oral_health/action/services/en/ 82. Zingales L. (2000), In Search of New Foundations, The Journal of Finance, The Journal Of The American Finance Association, Volume 55, Issue 4 102 Appendices 103 APPENDIX 1: DATA EXTRACTION FORM FOR SYSTEMATIC REVIEW 104 SYSTEMATIC REVIEW: DATA EXTRACTION FORM Balanced Scorecard in Health care Article Reference # Date Name of Extractor Name of Journal Language of article Year of Publication Authors Full text available 1. Yes 2. No Name of Organization where BSC implemented Does this study involve BSC application 1. Yes 2. No 3. Other PM initiative related to BSC Study Design 1. General discussion of BSC principles 2. Case study 3. Quasi experimental design 4. Case Control study 5. Cohort study 6. RCT 7. Other Study outcomes 1. Well described 2. Partially described 3. Not described/ evaluated 4. Not applicable Briefly describe the study results with implications: Selection criteria met: 1. Yes 2. No 105 Analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to faith-based health institutions in Zimbabwe: The case of Adventist Dental Practice APPENDIX 2: KEY INFORMANT GUIDE 106 Analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to faith-based health institutions in Zimbabwe: The case of Adventist Dental Practice Demographic Data Gender : __________ Age: _______ years Qualification: ________________________________________________________ Position: ________________________________________________________ Tenure at ADP: _______ years Key informant interview guide a) What would you describe as the critical success factors for ADP? b) In what way is performance measurement carried out at ADP? c) How is the BSC different from what performance measurement systems already existed in your clinical clinic? d) What resources if any, can be allocated for BSC implementation e) How do you expect the implementation of the BSC to affect the clinic’s staff and operations? f) What might helped or hinder the BSC implementation activities in your clinic? Interview guide developed based on Pettigrew and Whip’ s conceptual framework (WHAT, WHY, HOW) 107 Analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to faith-based health institutions in Zimbabwe: The case of Adventist Dental Practice APPENDIX 3: AUTHORIZATION TO CARRY OUT THE RESEARCH 108 Analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to faith-based health institutions in Zimbabwe: The case of Adventist Dental Practice 1895 Mahatshula North Bulawayo 12 May 2020 The Medical Director Adventist Dental Practice Suburbs Dear Sir Re: Request for permission to carry out a research at Adventist Dental Practice I am kindly requesting permission to carry out my research at your institution. My dissertation is entitled “Analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to faith-based health institutions in Zimbabwe: The case of Adventist Dental Practice.” This research, while being a requirement for my Master of Science degree in Accounting and Finance with Lupane State University, will also benefit your institution by providing financial management insights and beneficial customer feedback. It is in this light that I am requesting permission to carry out the above mentioned study. I will need to gather facts by means of questionnaires and interviews with willing administrators, employees and patients. I also intend to analyse some patient records and business documents. The deadline for submission is end of this month (May 2020) so the request is a bit urgent. I anticipate a favourable response. Yours sincerely Dumisani Dlodlo 109 Analysis of the applicability of the Balanced Scorecard concept to faith-based health institutions in Zimbabwe: The case of Adventist Dental Practice Adventist Dental Practice 41 Lawley Road Suburbs Bulawayo 14 May 2020 Dear Mr. Dlodlo Re: Request for permission to carry out a research at Adventist Dental Practice Your request dated 12 May 2020 refers. I am pleased to authorize your request to carry out the said research. We trust that the study will be of benefit to us as an organization as well. We wish you the best in your studies. Yours sincerely Dr. Jesse Agra Medical Director 110