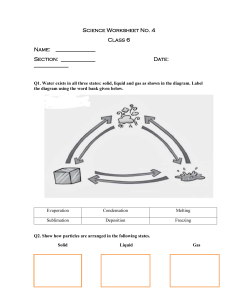

Circulation, Deposition and the Formation of the Greek Iron Age Author(s): Ian Morris Source: Man , Sep., 1989, New Series, Vol. 24, No. 3 (Sep., 1989), pp. 502-519 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2802704 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Man This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms CIRCULATION, DEPOSITION AND THE FORMATION OF THE GREEK IRON AGE IAN MORRIS University of Chicago The beginning of the Iron Age in the eastern Mediterranean is currently explained as a response to a bronze shortage following the collapse of the palatial systems around 1200 B.C. In this article the archaeological data are related more to depositional patterns. The model is challenged for ancient Greece and the dominance of iron in graves after 1050 B.C. is explained as an elite monopoly on iron, forming part of a new, stable ideological system and the rise of small-scale, inward-turned communities. This argument is important for our understanding ofthe Greek city state, for recent debates about the structures of Early Iron Age European society and for our definitions of 'Iron Ages' in prehistory. Around 1025 B.C. bronze more or less vanishes from excavated sites in central Greece, being replaced by a previously rare metal: iron.1 In this article, I argue that the dominant interpretation of this process assumes too direct a link between the circulation ofmetals in the past and the material record in the present. I contrast two approaches to the shift from bronze to iron in the archaeological record, which I call the 'circulation model' and the 'deposition model'. The currently popular circulation model sees a decline in long-distance trade causing a bronze shortage and the rise of an iron-based economy. The deposition model explains the same data in terms of the choices of actors creating the material record, thus severing the simple link between our evidence and the ancient uses of metals. Close analysis of context can invalidate old theories and stimulate new ones (e.g. Bradley 1985; S0rensen 1987). Most of the Greek finds were deliberately deposited; I argue that regional patterns in deposition may be evidence not for the rise of Europe's first iron-based economy but for the divergence of two types of social structure in mainland Greece. One, where iron displaced bronze in burial customs, grew in the eighth century into the polis city state. The other, where metals were used very differently in rituals, developed into the larger, looser ethnos states or the more 'archaic' city states of Crete. Ethnos states such as Macedonia and Achaea dominated Greece after 350 B.C., but in the poleis (city states), above all Athens in the sixth to fourth centuries, a unique cultural system developed which has affected all subsequent European history. The 'deposition model' lets us study the start of this divergence. On a more general level, I follow up what Hodder calls 'a lack of emphasis on the internally generated meaning of the exchange system' (1982: 204) in studies of prehis- toric trade. Sophisticated work is being done on long-distance contacts (e.g. Rowlands et al. 1987; Champion 1989), but more attention could be paid to cultural dynamics within small groups (e.g. Hodder 1989). The Greek data allow such a study. Gosden Man (N.S.) 23, 502- 519 This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms IAN MORRIS 503 (1985) has criticised models of European prehistory which emphasise long-distance trade. Like him, I describe the rise of a highly regionalised system, a typical process in Iron Age Europe. As Rowlands points out (1984; 1986; 1987), great sensitivity is needed in generalising about 'European' trends; and the unique palatial prehistory of Greece further complicates the issues. Simply opposing production and exchange or 'internal' and 'external' dynamics as prime movers is inadequate. I argue here that the collapse of east Mediterranean trade by 1050 was a crucial event in that locally-obtained prestige goods-iron artefacts-came to play a vital role in creating and maintaining alliances and hierarchy. Some of the problems addressed here, such as how to distinguish between types of prehistoric state and how to move from deposition to daily use of artefacts, are widely relevant. But the clearest need is for further detailed regional studies, paying close attention to local processes. Alternative general propositions about Iron Age Europe must be evaluated empirically, not at the level of competing paradigms. Two models: circulation and deposition There is a consensus that the first Iron Ages began before 1000 B.C. around the shores of the east Mediterranean (e.g. Waldbaum 1978; Snodgrass 1983), but Childe's theory that 'Cheap iron democratized agriculture and industry and warfare too' (1942: 191) is out of favour. Iron is seen as a symptom, not a cause, of upheavals (e.g. Snodgrass 1971: 239; Stech Wheeler et al. 1981: 268). The motor for change is located in the eclipse of the Bronze Age kingdoms. Simplifying somewhat, the Near Eastern metals trade before 1200 was largely run from the palaces, with raw materials moving as gifts between kings, each controlling a discrete area. The merchants were, at least till the thirteenth century, usually palace dependants (Zaccagnini 1977; Heltzer 1977; McCaslin 1980; Liverani 1987). The situation in Greece and Cyprus is less clear (Muhly 1983; Knapp 1986), but the Mycenaean palaces were involved in bronze production (Lang 1966). The circulation model explains the spread of iron in Syria: Palestine, Cyprus and Greece as a functional response to problems in obtaining copper and tin after the fall of many palaces around 1200 B.C. These regions had long known iron (Waldbaum 1983; Muhly et al. 1985) and after 1200 they were forced to exploit locally available iron ore on a larger scale. The circulation model thus provides a motive for the adoption of innovation. Snodgrass suggests a three-stage typology for the development of the Iron Ages (1980: 336-7); 1) Iron is known but is rare, and is used mainly for decoration; 2) Iron is used as a 'working metal'2 for weapons and tools, but bronze dominates for practical implements; 3) Iron is the main working metal, although it does not completely replace bronze. Snodgrass identifies stage 2 in Cyprus, Greece, Syria and Palestine by 1200, and sees Cyprus as the first iron-based economy, entering stage 3 around 1100 (1983: 285-94). Stage 3 begins in the Aegean islands and parts of the mainland by 1050. Crete was perhaps fifty years behind, while western Greece and western Mediterranean Europe lagged by up to 300 years (Snodgrass 1980: 359-66), and 'barbarian' Europe by longer still (Snodgrass 1965; in press). Snodgrass identifies three regional patterns in Greece (fig 2): This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 504 IAN MORRIS Olynthus, Kastanas * Assiros E Vergina ou ou TIo ro ne Phiki Stavros Gavala * Atalandi 0 0 * * t Lefkandi - Kalapodi AAegira'hIsthmia Athens Mycenae = Olympia> Argos *fV L ion Asine = PyloSi Nichorlia r0 n, ~ Knos os A) LY~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ it T _ ~~~~~~Kommo FIu y 1 Sts meniond n te txt s FIGUR,E 1. Sites mentioned in the text. This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms * Palaio IAN MORRIS 505 1) Around the Aegean (particularly in Attica, the Argolid, Thessaly, the Cyclades, southwest Asia Minor and perhaps the Dodecanese) iron weapons become relatively common around 1050 and very few bronzes at all date from between 1025 and 950, with even intricate ornaments being made from iron; 2) In Macedonia and Crete, iron becomes common for weapons after 1000, but bronze remains the main material for ornaments; 3) In the western parts of Greece (particularly Elis, Phocis, Kephallonia, Ithaca and Achaea) iron is very rare in deposits until the ninth century, and such bronzes as occur are either heirlooms or typologically backward copies of Bronze Age objects. 2 I~~~~~ 1 FIGURE. 2. Regional patterns of deposition (see text for expl Snodgrass suggests that advanced areas of Greece learned iron technology from Cyprus before 1050, but a collapse in long-distance trade cut off supplies, of copper, tin, gold and ivory. The Cypriot kingdoms probably survived the disasters around 1200 B.C. (Snodgrass 1988; contra, Rupp 1987; 1988) and stayed in touch with the Levant (Bikai 1987); but Greek objects vanish from Cyprus until the late tenth century (Coldstream 1986: 325) and even after this, the best evidence for contacts comes from Crete (Coldstream 1984). There is a major tin source in the Taurus mountains (Yener & Ozbal 1987) and much copper may have come from Sardinia (T.R. Smith 1987: 32-46), but if contact with Cyprus was lost it could have been lost with these regions too. The Aegean went over almost entirely to iron, even forjewellery; western Greece, where imports were rare but the new iron technology was not in use, struggled on This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 506 IAN by MORRIS recycling old bronzes. tin, gold and ivory, taking advantage of iron for functional items after 1000 while keeping other media for ornaments. By 925, trade was resuming. Bronze again became common around the Aegean. Corinthians began to penetrate northern Greece for copper (Morgan 1988) and iron reached the west (Snodgrass 1971: 228-68). The weakness in this model is its assumption of a direct link between the circulation ofbronze and its recovery by excavators, treating deposition as a neutral process. Nearly all the Greek metal has come from burials, and the implicit hypothesis that grave goods are a constant cross-section of the material culture of the living is questionable (Morris 1987: 29-43). Bronze might equally well have disappeared from graves because it was no longer appropriate for funerals. Desborough (1972: 316-18) suggested that 'personal preference' played a role, but he left choice as a whimsical factor, either too frivolous or too psychologically embedded to pursue further. Yet these 'preferences'; created strong regional patterns in ritual practices. The shift from bronze to iron is part of a larger set of changes in burial in central Greece around 1050. A basically Mycenaean material culture survived until about 1125, but the 'Sub-Mycenaean' evidence3 suggests rapidly changing systems of ritual meanings (Morris 1987: 172-3; Whitley 1987: 136-42). Around 1050 this chaos was swept away and new patterns emerged, which were stable till nearly 900 (Morris 1987: 179-83). Several distinct material cultures formed in the central Aegean region in the twelfth century. The pottery styles fall into two main groups: the Attic and the Thessalo-Euboean (Desborough 1975: 673-5), while burial customs are even more diverse (Snodgrass 1971: 147-64). However, beneath the formal variation, the whole region shares the same structure in its archaeological record. The new funerals made a distinction within the community, between an elite of perhaps a quarter to a third of the adult population, and an inferior group. This was marked most clearly by the informal disposal of the 'inferiors', so that their burials leave few traces (Morris 1987). Membership of these groups probably depended on control of land, not on genealogical position within a lineage (Finley 1978: 59-60; Morris 1987: 87-93). This burial pattern appears in the areas of the proposed 'bronze shortage', along with sweeping changes in all aspects of material culture the invention of the Protogeometric pottery style, new locations for settlements, new burial customs and, above all, the replacement of bronze by iron. At Athens, metalwork is distributed far more evenly after 1050 than before. For over 100 years no intact adult grave is either very rich or very poor (table 1): there is a marked uniformity in grave goods for each sex. The change from bronze to iron must be interpreted within this overall funerary framework. The age of iron People in many parts of the world give objects (and other people) 'exchange order' rather than 'exchange value' (Firth 1965: 336-44). Objects are classed in separate spheres of exchange and evaluated ordinally rather than cardinally. It can be difficult to break into the top-ranked sphere, especially if an individual or group wants to monopolise it (Appadurai 1986). Access to metals need not be easy or equal, even if they are mined locally. If an elite could control dependent smiths and/or the ores themselves-situations common enough in the ethnographic record (Rowlands 1971; This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms M IAN MORRIS 507 TABLE 1. Distribution of vases and metal objects in intact adult burials at Athens, 1125-900 B.C. Period Percentage Mean number of. Gini coefficient: ofgraves with metal Vases Metal Vases Metal objects objects Submycenaean (1125-1050) 28.9% 1.3 1.7 .525 .879 Protogeometric (1050-900) 74.5% 4.9 1.8 .441 .502 Source: Morris 1987: 140-4, 147-51 Welbourn 1981)-they could forge a powerful weapon of exclusion (Morris 1986a). By controlling iron and making it the only metal appropriate for grave goods in formal burial, the symbol of membership of the elite, the leaders of Greek communities could solidify their powers, creating a nrtual gap between themselves and those excluded from iron and the formal cemetery. Gifts ofiron weapons andjewellery to less powerful households would admit them as lower order members of the elite; lower still were those households excluded entirely from the ceremonial creation of the community in formal burials (cf. Morris 1987: 93-6). The prohibition of bronze for grave goods might represent not scarcity but the inability of the elite to monopolise it. Why iron? It may have given the elite a decisive military advantage, although we know little about its hardness (Snodgrass 1971: 215-16). In this case, iron would maintain the new order not only as a prestige good but also as the means of destruction guaranteeing unequal access to wealth (cf. Goody 1971). Retaining the core idea of the circulation model, a decline in bronze supplies would further increase the military advantages of control over iron. It would also explain the elite's inability to monopolise bronze, if most of it was spread around in recycled Mycenaean objects rather than being concentrated in trade routes. Emulation of Near Eastern metal use may have added to iron's attractions; and the history of the metals suggests a third possibility. In the eighth century, when iron was no longer so highly ranked as bronze and was used for more everyday tasks (Finley 1978: 61-8; Brookes 1981; Rhodes 1987), bronze weapons appear in poetry as symbols to mark the heroes of the Trojan War as superhumans, playing a potent role in underwriting elite authority (Morris 1986b: 115-29). Iron weapons may have had a similar 'historical' role in the eleventh century, setting their owners off from previous generations of bronze users, distancing the elite from the chaos of an unwelcome past and establishing a stable world order. Snodgrass's three regional patterns would then be not three types of circulation and technology, but three systems of funerary ideology. Using iron for complex jewellery would point not to a bronze shortage but to conspicuous use of a highly charged medium to assert the status of the buriers of the women with whom most of these ornaments were deposited. The main difference between Athenian and Macedonian metal use would be that the Macedonians thought along the lines iron:bronze::male:female, while Athenian rituals were based on the assumption iron:bronze::elite:commoner. Similarly, putting a small bronze, ivory or bone globe This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 508 IAN MORRIS on the shaft of an iron pin need not mean that bronze was scarce. Catling felt that it 'suggests more a delight in the decorative quality in terms of colour, first, of the iron, then of the strong contrast offered by the copper/bronze of the boss' (1983a: 333)-not a bronze shortage, but a relaxation of exclusiveness for aesthetic effect. This possibility cuts us off from direct evidence for circulation. We do not know how common bronze was; because it was not used in the only social context to produce deposits which we have chosen to excavate, it is invisible. For example, a dump of foundry refuse shows that bronze tripods were being cast at Lefkandi c. 925-900 B.C. (Catling & Catling 1980). Catling (1984; cf. Rolley 1977: 133-4; Magou et al. 1986: 126) has argued that production was not continuous from 1200 to 950 B.C. and that most examples from eighth-century contexts were in fact made in Cyprus before 1150. Even accepting this (Muhly [1988: 333-5] disputes it), these objects were in circulation throughout the period, but are very rare in the archaeological record because they were used in situations which produced no recognisable material residue. In Homer, tripods moved as gifts at weddings, in initiation ceremonies, and between guest-friends. They were used at feasts and as treasure to gloat over. Their potential for becoming our data was minimal until they were turned into sanctuary dedications, at Olympia after 950 and elsewhere after 800. The only trace dated 1025-950 is a group ofpostholes at Lefkandi, possibly the base for a giant tripod (Popham & Sackett 1980a: 105). Around 925, bronze, gold, ivory and other Near Eastern imports return to central Greek graves, and more Greek pottery is found overseas. In the deposition model, this is seen as the breakdown of the stable system, through the inability of the elite to control iron any longer. Competition within elites intensified; at Athens we see new restrictions on access to formal burial (Morris 1987: 180-3) and on the range of motifs acceptable on grave pots (Whitley 1987: 166-93). When iron lost its potency as a symbol, elites turned to imports, encouraging Greek voyaging beyond the Aegean and providing greater incentives for Phoenician traders to come to Greece. Snodgrass (1987: 193-209) has argued for agricultural intensification after 900; the evidence is thin (Garnsey & Morris 1989: 99), but it is a plausible idea, and the growth in settlement c.900 certainly took more land into cultivation. The wealth of burials at Athens, Argos and Lefkandi escalated until c. 825, when a balance returned, before the entire structure collapsed around 750 with the rise of the institutions of the polis (Qviller 1981; Morris 1987: 183-205). In the next sections I examine the two models against burial finds, which generally fit Snodgrass's patterns, and against settlement evidence and technical analyses, which the circulation model will not accommodate. Sanctuaries do not provide a test: the circulation model is itself one reason for dating the Olympia bronzes after 950 (Rolley 1977: 133-4), so using them as evidence could be self-defeating. Recent excavations in early sanctuaries at Aegira, Isthmia, Kalapodi, Kommos and Koukounaries have found almost no metal before 700. Regional patterns: burial evidence Western Greece. New finds fit the pattern of little iron and possibly recycled bronze (see Morgan 1986: 15-63, 198-9), but a late tenth-century tomb with iron and bronze near Pylos may be a problem (Blegen et al. 1973: 237-42). Snodgrass, pointing out that Pylos was a major centre before 1200, suggests that this may have lasted long enough for iron working to get established (1980: 354). Graves at Atalandi (Catling This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms IAN MORRIS 509 1986: 136-7), Stavros (Dakoronia 1978: 136-7) and Gavala (Stavropoulou-Gatsi 1980) are unusually rich, but their dates are not secure. Two wealthy graves at Phiki (Batziou-Efstathiou 1984) with bronze and gold date c.1000-950, but the site has distinctly northern pottery types, and may belong with the Macedonian pattern. Northern Greece. Most evidence comes from Vergina, where iron rules for weapons and bronze for ornaments. Table 2 divides the finds into categories of ornaments and 'functional items' (weapons and tools). Unfortunately, the dating is poor.4 The rich cemeteries at Palaio Gynaikokastro (Catling 1987: 37) and Koukou (Catling 1988: 49) may alter the picture when published, but the large necropolis at Torone in Chalcidice fits expectations, although metal is rare (A.M. Snodgrass, pers. comm.). TABLE 2. Bronze and iron finds at Vergina, Macedonia Ornaments 'Functional' items Bronze Number * The Iron 240+ Bronze 5 bronze 1* Iron 151 sword from Sources: Petsas 1962; 1963; Andronikos 1969 Crete. The main work has been in the Knossos North Cemetery.5 Bronze and gold were quite common in the early Greek tombs (Catling 1979: 46-7; Whitley 1987: 284-5), but the iron is very interesting (table 3). In Subnminoan (c. 1100-925), over 50 per cent. of the iron finds are ornaments; after 925, the figure falls below 25 per cent. Iron was used for ornaments very selectively, with pins heavily favoured (table 4). Much the same pattern appears at Skales in Cyprus (table 5). Both Cretan and Cypriot buriers had access to bronze but liked iron pins. Factors of choice intervene here. The central Aegean area. Cemeteries dating 1100-825 have been explored at Lefkandi. Catling compared this material with Snodgrass's theory, suggesting that A salient fact is that the period of bronze shortage at Lekandi (if that is the correct way to interpret the change of balance in bronze and iron objects in LPG) comes later than its supposed occurrence at Athens. In fact, at least until SPG II, bronze was always used rather sparingly at Lekandi and if bronze objects appear numerically abundant, particularly in SM and EPG, it must be remembered that they are all small and their total weight is relatively tnvial (Catling 1980: 263-4). This is a serious challenge to Snodgrass's patterns, but I do not think the evidence bears it out (table 6 and fig. 3). In Middle and Late Protogeometric, which probably correspond to the period when bronze is scarce in Athenian graves,6 bronze is underrepresented and iron over-represented in the Lefkandi burials. The spectacular 'hero' graves of c.1000-950 B.C. (Popham et al. 1982a) are more ambiguous. The male cremation was in a twelfth-century Cypriot bronze burn, and some of the jewellery with the woman went back to 2000 B.C. This seems to me more like the deliberate use of heirlooms to express the prestige of the dead than desperate reuse of old metalwork in a shortage, but any interpretation of this unique discovery is highly subjective. This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms g 510 IAN MORRIS TABLE 3. Iron finds from the Knossos North Cemetery Period Ornaments Subminoan Subminoan/ 'Functional' (1100-925) 7+ Protogeometric Protogeometnrc items (925-800) 7 1 5 2 126 Early-Middle Geometric (800-740) 10+ 46 Late Late Geometric Geometric/ (740-710) 7 Orientalising Orientalising (710-625) 29 10 12 17 58 A further 30 functional items can be dated only as Protogeometric-Middle Geometric, and a further 10 ornaments and 60 functional items only as Geometric. Source: A.M. Snodgrass, unpublished report. TABLE 4. Iron ornaments from Knossos Period Fortetsa North Cemetery Subminoan 1 pin 4+ pins, 2 fibulae, 1 ring Subminoan/ Protogeometric none 1 pin Protogeometric 4 pins 3 pins, 2 fibulae Early-Middle Geometric 8 pins 9+ pins,*, 1 fibula Late Geometric 7 pins 7+ pins Late Geometric/ Orientalising None 8 pins, 1 bracelet, 1 fibula Orientalising *The pins 1 ring from 12+ tomb pins 75 were rusted together tomb 294 could be Middle or Late Geometric. Sources: Brock 1957; A.M. Snodgrass, unpublished report. TABLE 5. Finds in the Skales cemetery, Paphos, Cyprus Period Ornaments 'Functional' items Gold/silver Bronze Iron Bronze Iron a) Metal use Cypro-Geometric I (1050-950) 99 9 59 20 21 Cypro-Geometric Cypro-Geometric b) Iron 0 17 4 1 15 III (850-750) 6 II (950-850) 22 1 9 22 ornaments Cypro-Geometric I 6 pins, 2 fibulae, 1 ring Cypro-Geometric II 4 bowls (all from tomb 80) Cypro-Geometric III 1 pin Sources: Karageorghis 1983; see also Snodgrass 1983 This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms in IAN MORRIS 511 TABLE 6. Mean numbers of objects of iron and bronze per grave at Lefkandi Period Iron Bronze Submycenaean Number (1125-1050) of 0.2 graves 2.0 22 Early Protogeometric (1050-1025) 0.6 2.4 11 Middle Protogeometric (1025-1000) 0.75+ 0.6+* 12 Late Protogeometric (1000-900) 1.25 0.6 24 Sub-Protogeometric I (900-875) 0.5 1.2 26 Sub-Protogeometric II (875-850) 0.4 2.5 14 Sub-Protogeometric III (850-825) 0.5 3.7 6 Overall 0.6 1.6+ 115 The Middle Protogeometric uncertainty concerns the number of grave goods with the Toumba heroon female inhumation; the mean figures are probably only very slightly higher than those shown. Sources: Popham & Sackett 1980a; Popham et al. 1982a; 1982b. Other graves are described in less detail in Catling 1985: 15-16; 1987: 12-14. 'Bronze shortage' + 150% +100% Ca E 0% - 50% -10 SM EPG MPG LPG SPG I SPG 11 SPG 111 Chronological phase FIGURE 3. Mean numbers of bronze and iron objects per adult burial at Lefkandi, shown as a percentage of the mean number of objects of each material per grave across the whole period of use of the cemeteries, c.1100-825 B.C. (see table 6). Regional patterns: settlement evidence Western Greece. The main site is Nichoria (table 7). In Dark Age It and III iron is more common for functional items, but bronze always dominates the ornaments. On Coulson's dating (1983: 318-22) Snodgrass's stage 3 of iron use begins only around 850 and Nichorians continued to have bronze for ornaments throughout the supposed shortage. This difference between settlement and burial uses fits the deposition model, but there are problems. The sample is tiny and its dating is weak, resting largely on parallels for a single bronze pin. Snodgrass (1984: 153) rightly points out that Coulson's dates could This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 512 IAN MORRIS TABLE 7. Bronze and iron finds from Nichoria Period Ornaments 'Functional' items Bronze Iron Bronze Iron Dark Age I Dark Age I-II Dark Age Dark Age Dark (1075-975)* II (975-850) (975-850) II-III Age III 0 4 5 0 8 2 16 8 9 (850-800) (800-750) *Excavator's 1 1 3 6 1 2 1 1 2 3 3 chronology (Coulson Source: McDonald et al. 1983 be 50-200 years too early. The site's relevance is therefore questionable. Northern Greece. The shallow Early iron Age layers at Assiros produced only a stone mould for casting bronze knives and an iron double axe, both from disturbed contexts (Wardle 1980:261; 1987: 320; Catling 1988: 42-5). Some metal has been found at Kastanas (table 8), but the sample is again small. TABLE 8. Bronze and iron finds from Kastanas Period Ornaments 'Functional' items Bronze Iron Bronze Iron Transition Early Early Iron Developed Late to Iron Age Age Age Iron Iron *The Iron I II 3 Age Age bronze 4 6 6 0 0 8 0 0 3 1 0 8 3 0 1 0 0 3 1 spearhead Source: Hochstetter 1987 The central Aegean area. The main published settlement of this period is Asine. Here, gr. 1970-15 (c.950-900 B.C.) fits Snodgrass's pattern of iron and no bronze (Wells 1976: 16-19), but in the houses seven small bronzes, a lead clamp and traces of bronze and iron working were found (Wells 1983: 79-80, 101, 116, 227, 255, 278). This would fit the deposition model best, but once more the sample is small. In the Lefkandi 'heroon' bronze and iron fragments were found, probably from a door fastening (Catling 1983b: 14). Technical studies Twenty-four bronzes from Nichoria have been analysed. The tin content was high, reaching 25 per cent. This was perhaps deliberate: Catling (1983a: 283) comments that 'a significant correlation seems clear between bronzes with a very high tin content and their decorative function'. The dating problems ofNichoria have been mentioned, but there is no such difficulty at Lefkandi, where 102 bronzes were studied. The mean tin content was stable at This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms IAN MORRIS 513 around 5 per cent. from c.1 100-900, before shooting up to 10.5 per cent. in the ninth century. Jones concluded that 'there was a ready availability of the base metals to the metalsmiths at Lefkandi during the time span of the cemeteries' (1980: 457). Another series of analysed bronzes, tripods from sanctuaries, begins c.925, just as the hypothesised bronze shortage ends; but down to 750, they were made from almost pure copper. What tin does occur is almost certainly accidental (Filippakis et al. 1983: 127). Further, the increase in tin after 750 was not simply a result of improved supplies but of deliberate imitation of oriental tripods with a higher tin content, or even of the presence ofNear Eastern craftsmen in Greece. The late eighth century mainland tripods which copy Oriental designs have a mean tin content of 6.0 per cent., while those continuing earlier mainland traditions have low and erratic tin contents, like their ninth-century models (Filippakis et al. 1983: 118). In ninth-century Crete, tripods were almost pure copper, like those on the mainland and on Ithaca, while Cretan bronze shields had a higher and more regular tin level (Magou et al. 1986: 130-3). Tripod makers chose to use tin-free copper after 925, or in some cases even to cast tripods in iron (Maass 1979: 126-30,225-7). Trade had increased, but creative selection of materials intervened between supply, production, circulation and deposition. Lead isotope analysis reveals that eighth-century Athenian tripods were made from copper from Lavrion (Magou et al. 1986: 133). Unless this source was forgotten between 1050 and 900, the Athenians could have cast low-tin bronzes without suffering from any trade decline. Summary The evidence suggests complex metal use, with hidden factors affecting the archaeological record and the ways we have created the Greek Early Iron Age. The material is consistent with the theory that iron drove bronze from central Aegean graves between 1025 and 950 as part of the rise of a new social structure, and less consistent with the idea that a decline in trade is a sufficient explanation. The circulation model by itself does not account for the patterns. Cold iron Gold is for the rnistress-Silver for the maid- Copper for the craftsman cunning at his trade. 'Good!' said the baron, sitting in his hall, 'But Iron-Cold Iron-is master of them all'. Rudyard Kipling, Cold Iron How are we to imagine this age of iron? I have proposed a prestige economy, with iron monopolised by elites and circulated as gifts among them. The local chief, the basileus of eighth-century poetry, would hold loose and probably unstable control over one or more villages in a lightly-settled countryside. Several basileis (the plural form) would concentrate where villages were grouped together, as at Athens, which may have numbered as many as 3,000-5,000 souls before 900 B.C. One of these men would probably be recognised as dominant, although it might be difficult for him to transfer this status to his children. Power would be based on control of land and dependants and alliances through gifts with lesser local households and with basileis in other areas. Short-distance gift relationships between basileis could act as buffers against the inter- This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 514 IAN MORRIS annual variability in rainfall which Greece is prone to (Gamsey 1988: 8-39; Gamsey & Morris 1989) and provide political support. Iron was not only a symbol of the elite group but also a means of enforcing its power. Control of the means of destruction was probably a vital part of the 'social caging' which the elites struggled to create to prevent their dependants from escaping into unoccupied lands. Some basileis might extend their power over a wider area or head leagues of chiefs, but such larger units would have been short-lived. The system ran into trouble by 900, and collapsed around 750, with the rise of the polis. This process of secondary state formation was perhaps predictable, given the proximity of imperial civilisations, and can be seen at one level as an example of peer polity interaction (Renfrew & Cherry 1986). However, its importance lies not in its 'complexity' but in the uniqueness of the citizen ideologies which emerged at this time. The structure of the archaeological record is totally transformed around 750. The change is abrupt and has been difficult to explain in other than the most general terms (Morris 1987: 201-5). The 'deposition model' of the bronze/iron transition allows a longer perspective on the rise of the polis. As early as the eleventh century, the central Aegean areas where the polis was to appear diverged from north and west Greece and Crete. Whether we emphasise differences in the Mycenaean world before 1200, or variations in responses to the twelfth-century breakup, or a more catastrophic rupture around 1050, this approach opens the way for a more detailed analysis of the rise of the polis. Many scholars have stressed the power of aristocrats in Archaic Greece, but the most remarkable feature of the polis was the solidarity of the citizen body as a whole against elite interests, culminating in the Classical Athenian democracy (Morris in press). We might see this communal strength growing up as a popular culture response to the very sharp ritual division created in 'official' burial practices, eventually creating enough subversive power to begin a social revolution in the eighth century, while outside the regions where this system was established c.1050 no such polarisation occurred. In Classical times, north and west Greece and Crete continued to be dominated by relations of production based on dependent serf-like groups within the community rather than the strictly delimited citizen body with deracinated chattel-slave labour force of the developed polis (Finley 1981: 97-166). The deposition model severs the link between our data and the use of metals in everyday life, raising the question of what it means to speak of the 'Early Iron Age' at all. Iron reigned supreme as a prestige good and on the battlefield, but metals were apparently little used otherwise-until c.700 or even later most tasks were probably carried out with stone, bone or wood (Runnels 1982; Blitzer & McDonald 1983; Morris 1986a: 10-11; Hochstetter 1987: 46-82). Compared to Greek settlements of the fifth and fourth centuries, the Early Iron Age was almost metal-free (e.g. Robinson 1941; Burr Thompson 1960). Metal tools were much commoner in Cyprus and the Levant than in Greece (Waldbaum 1978: 24-31). Genuine steel was produced in Palestine in the twelfth century (Davis et al. 1985) and perhaps earlier still in Jordan (R.H. Smith et al. 1984); thorough carburisation and quench-hardening were used in Cyprus well before 1000 B.C. (Tholander 1971; Maddin 1983; Stech et al. 1985). Both regions have a better claim than Greece to be called iron-based economies, although there are some unexpected patterns. McGovern (1986: 277) questions the circulation model's relevance to Jordan: in twenty analysed bronzes from burials in Baq'ah valley cave A4, the mean This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms IAN MORRIS 515 tin content rises steadily from 6.1 per cent. in Late Bronze I to 10.6 per cent. in Iron IA (McGovern 1986: 283). In the eleventh-century graves steel was used only for jewellery (McGovern 1986: 272-3, 338-9). Similarly, Astrom et al. (1986: 40) suggest that iron was highly valued in some parts of Cyprus, being found in tombs in association with gold (cf. Waldbaum 1983: 335-6). Braudel observed that 'the iron age had hardly begun for the entire chronological span of this book [A.D. 1400-1800]. The farther back in time one goes from the great turning point of the industrial revolution, the smaller the role played by iron ... The period covered by this book was still very much the age of wood' (1981: 382). Any definition of 'Iron Age' is of course relative, but to call the Aegean an iron-based economy before the sixth century would be a distortion. Iron moved around in a very restricted sphere of exchange, divorced from everyday activity, but it was that sphere which had the greatest influence on the creation of our archaeological record. To conclude: I propose a new interpretation of the replacement of bronze by iron in the archaeological record of eleventh-century Greece, seeing it as evidence for the rise of a new stable order after the fall ofthe Mycenaean palaces. This challenges current assumptions about the beginning of the Iron Age in the eastern Mediterranean and the construction of concepts of the 'Iron Age'. NOTES A shorter version of this article was discussed at the Cambridge Iron Age conference in December 1988, organised by Cathy Morgan, Sander van der Leeuw and Greg Woolf, and the argument has benefited from the participants' suggestions. I particularly want to thank Anthony Snodgrass, who has for more than six years helped me to propose interpretations of early Greece which differ from his own. He offered valuable comments on an earlier draft of this article, as well as allowing me access to his notes on the iron finds from the Knossos North Cemetery. Neither he nor anyone else named necessarily agrees with the results. 1 I follow the absolute chronology suggested by Snodgrass (1971: 134-5). Renfrew (1985: 84-7) and Mountjoy (1986: table 1) propose lower dates, and the best answer is still unclear. The calendar years are used as conventional signposts for the relative positions of different local sequences, not firm points (Morris 1987: 10-18). 2 Snodgrass's use of the expression 'working metal' was queried by Maddin (in Snodgrass 1983: 295), but confusion seems unlikely so I retain it here. 3 The best discussion of the problems of defining a Sub-Mycenaean culture in the period 1125-1050 is still Snodgrass (1971: 28-40). 4 Hammond (1972: 219-36, 384-99) and Kilian (1975: 65-74) challenged the excavator's dating, and Snodgrass (1971: 132-3, 160-3, 253-5; 1980: 350) has argued that all three systems are too high. 5 This cemetery is in the process of publication. Professor Snodgrass very kindly allowed me to read his report on the iron finds, but I have not yet seen accounts of the bronzes. The conventional chronology of Knossian metalwork may need to be revised in the light of this important excavation. 6 The chronological relationship of the Athenian and Lefkandian Protogeometric sequences is still unclear, but Desborough (1980: 285-92) put the start of both Early phases around 1050 on the absolute system used here and had Lefkandian Late Protogeometric begin at some point during the Attic Late style. Sub-Protogeometric II overlapped with Attic Early Geometric II, and Sub-Protogeometric III with Attic Middle Geometric. Popham and Sackett (1980b: 355) suggest c.1050-1000 for Early and Middle Protogeometric, and c.1000-900 for Late Protogeometric. REFERENCES Andronikos, M. 1969. Vergina L Athens: Vivliothiki tis en Athinais Arkhaiologikis Etaireias, no. o2. Appadurai, A. 1986. Introduction. In The social ife of things (ed.) A. Appadurai. Cambridge: Univ. Press. Astr8m, P., R. Maddin, J.D. Muhly & T. Stech 1986. Iron artefacts from Swedish excavations in Cyprus. Opuscula Atheniensa 16, 27-41. This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 516 IAN MORRIS Batziou-Efstathiou, A. 1984. Protogeometrika apo ti Dytiki Thessalia, Athens Annals Archaeol. 17, 74-87. Bikai, P.M. 1987. The Phoenician pottery of Cyprus. Nicosia: Dept. of Antiquities. Bintliff, J. (ed.) 1984. European social evolutions. Bradford: Univ. Press. Blegen, C.W., E. Rawson, W. Taylour & W.P. Donovan 1973. The palace of Nestor at Pylos in western Messenia III. Princeton: Univ. Press. Blitzer, H. & W.A. McDonald 1983. A note on stone and bone artifacts. In McDonald et al. 1983. Bradley, R. 1985. Exchange and social distance-the structure of bronze artefact distributions. Man (N.S.) 20, 692-704. Braudel, F. 1981. The structures of everyday lIfe. London: Fontana. Brock, J.K. 1957. Fortetsa: early Greek tombs near Knossos (Brit. Sch. Archaeol. Athens Supp. 2). Cambridge: Univ. Press. Brookes, A.C. 1981. Stoneworking in the Geometric period at Corinth. Hesperia 50, 285-90. Burr Thompson D. 1960. The house of Simon the shoemaker. Archaeology 13, 234-40. Catling, H.W. 1979. Knossos, 1978. Archaeological Reportsfor 1978-79: 43-8. 1980. Objects of bronze, iron and lead. In Popham et al. 1980c. 1981. Archaeology in Greece, 1980-81. Archaeological Reports for 1980-81: 3-48. 1982. Archaeology in Greece, 1981-82. Archaeological Reportsfor 1981-82: 3-62. 1983a. The metal objects. In McDonald et al. 1983. 1983b. Archaeology in Greece, 1982-83. Archaeological Reports for 1982-83: 3-62. 1984. Workshop and heirloom: prehistoric bronze stands in the east Mediterranean. Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus: 69-91. 1985. Archaeology in Greece, 1984-85. Archaeological Reportsfor 1984-85: 3-69. 1986. Archaeology in Greece, 1985-86. Archaeological Reportsfor 1985-86: 3-101. 1987. Archaeology in Greece, 1986-87. Archaeological Reports for 1986-87: 3-61. 1988. Archaeology in Greece, 1987-88. Archaeological Reports for 1987-88: 1-85. Catling, H.W. & E.A. Catling 1980. the mould and crucible fragments-the foundry refuse. In Popham et al. 1980. Champion, T.C.(ed.) 1989. Centre and periphery. London: Unwin & Hyman. Childe, V.G. 1942. Wat happened in history. Harmondsworth: Peregrine Books. Coldstream, J.N. 1984. Cypriaca and Cretocypriaca from the North Cemetery of Knossos, Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus: 122-37. 1986. Kition and Amathus: some reflections on their westward links during the Early Iron Age. In Karageorghis 1986. Coulson, W.D.E. 1983. The pottery. In McDonald et al. 1983. Curtis,J. (ed.) 1988. Bronze-workingcentres ofwesternAsia, c. 1000-539 B.C. London: Kegan Paul International. Dakoronia, F. 1978. Ephoreia proistorikon kai klasikon arkhaiotiton Lamias, Arkhaiologikon Deltion 33(2), 132-41. Davis, D., R. Maddin, J.D. Muhly & T. Stech 1985. A steel pick from Mt Adir in Palestine. J. Near East. Stud. 44, 41-51. Desborough, V.D. 1972. The Greek Dark Ages. London: Methuen. 1975. The end of the Mycenaean civilisation and the Dark Age: the archaeological background, Cambridge Ancient History II part 2B (3rd edn.). Cambridge: Univ. Press. 1980. The Dark Age pottery (SM-SPG III) from the settlement and cemeteries. In Popham et al. 1980c. Filippakis, S., E. Photou, C. Rolley & G. Varoufakis 1983. Bronzes grecs et onentaux: influences et apprentissages. Bull. Corresp. hellen 107, 111-32. Finley, M.I. 1978. The world of Odysseus (2nd edn). London: Chatto & Windus. 1981. Economy and society in ancient Greece (eds) B.D. Shaw & R.P. Saller. London: Chatto & Windus. Firth, R. 1965. Primitive Polynesian economy (2nd edn). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Gamsey, P. 1988. Famine andfood supply in the Graeco-Roman world. Cambridge: Univ. Press. Gamsey, P. & I. Morris 1989. Risk and the polis. In Halstead & O'Shea 1989. Goody, J.R. 1971. Technology, tradition and the state in Africa. Cambridge: Univ. Press for the International African Institute. Gosden, C. 1985. Gifts and kin in Early Iron Age Europe. Man (N.S.) 20, 475-93. Halstead, P. & J. O'Shea (eds) 1989. Bad year economics: cultural responses to uncertainty. Cambridge: Univ. Press. This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 56 UTC IAN MORRIS 517 Hammond, N.G.L. 1972. A history of Macedonia I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Heltzer, M. 1977. The metal trade of Ugarit and the problem of transportation of commercial goods. Iraq 39, 203-11. Hochstetter, A. 1987. Kastanas: die Kleinfunde (Prahist. Archaol. Suidosteuropa 6). Berlin: Volker Spiess. Hodder, I. 1982. Symbols in action. Cambridge: Univ. Press. (ed.) 1987. The archaeology of contextual meanings. Cambridge: Univ. Press. (ed.) 1989. The meanings of things. London: Unwin Hyman. Jones, R.E. 1980. Analyses of bronze and other base metals from the cemeteries. In Popham et al. 1980c. Karageorghis, V. 1983. Alt-Paphos III: Palaepaphos-Skales, an Iron Age cemetery in Cyprus. 2 vols. Konstanz: Univ. Press. (ed.) 1986. Cyprus between the orient and the occident. Nicosia: Dept. of Antiquities. Kilian, K. 1975. Trachtzubeh6r der Eisenzeit zwischen Agais und Adria. Prahist. Z. 50, 63-104. Knapp, A.B. 1986. Copper production and divine protection: archaeology, ideology and social complexity in Bronze Age Cyprus. G6teborg: Stud. Med. Arch. Pocketbook 42. Lang, M. 1966. In formulas and groups. Hesperia 35: 397-412. Liverani, M. 1987. The collapse of the Near Eastern regional system at the end of the Bronze Age: the case of Syria. In Rowlands et al. 1987. Maass, M. 1979. Olympische Forschungen X: die geometrischen Drefuisse von Olympia. Berlin: de Gruyter. McCaslin, D.E. 1980. Stone anchors in antiquity: coastal settlements and maritime trade routes in the eastern Mediterranean. Goteborg: Stud. Med. Arch. 61. McDonald, W.A., W.D.E. Coulson &JJ. Rosser (eds) 1983. Excavations at Nichoria in southwest Greece III. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press. McGovern, P.E. 1986. The Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages of central Transjordan: the Baq'ah Valley project (Philadelphia: Univ. Mus. Monogr. 65). Philadelphia: Univ. Museum. Maddin, R. 1983. Early iron technology in Cyprus. In Muhly et al. 1983. Magou, E., S. Philippakis & C. Rolley 1986. Tr6pieds geometriques de bronze, analyses complementaires. Bull. Corresp. hellen 110, 121-36. Morgan, C.A. 1986. Settlement and exploitation in the region of the Connthian Gulf, c.1000-700 B.C. Thesis, Cambridge University. 1988. Corinth, the Corinthian Gulf and western Greece during the eighth century B.C. Ann. Brit. Sch. Archaeol. Athens 83, 313-38. Morris, I. 1986a. Gift and conumodity in Archaic Greece. Man (N.S.) 21, 1-17. 1986b. The use and abuse of Homer. Class. Antiq. 5, 81-138. 1987. Burial and ancient society: the rise of the Greek city state. Cambridge: Univ. Press. in press. The early polis as city and state. In Rich & Wallace-Hadrill in press. Mountjoy, P. 1986. Mycenaean decorated pottery: a guide to identfication. Goteborg: Stud. Med. Arch. 73. Muhly, J.D. 1983. The nature of trade in the LBA east Mediterranean: the orgamsation of the metals' trade and the role of Cyprus. In Muhly et al. 1983. 1988. Concluding remarks. In Curtis (ed.) 1988. , R. Maddin & V. Karageorghis (eds) 1983. Early metallurgy in Cyprus, 4000-500 B.C. Nicosia: Dept. of Antiquities. , T. Stech & E. Ozgen 1985. Iron in Anatolia and the nature of the Hittite iron industry. Anatol. Stud. 35, 67-84. Petsas, Ph. 1962. Anaskaphi arkhaiou nekrotapheiou Verginis. Arkhaiologikon Deltion 17(1): 218-88. 1963. Anaskaphi arkhaiou nekrotapheiou Verginis. Arkhaiologikon Deltion 18(3): 217-32. Popham, M.R. & L.H. Sackett 1980a. The excavation and layout of the cemeteries. In Popham et al. 1980c. 1980b. Historical conclusions. In Popham et al. 1980c. , L.H. Sackett & P.G. Themelis (eds) 1980c. LeJkandi I (Brit. Sch. Archaeol. Athens Supp. 1). London: Thames & Hudson. , E. Touloupa & L.H. Sackett 1982a. The hero of Lefkandi. Antiquity 56, 169-74. 1982b. Further excavations of the Toumba cemetery at Lefkandi, 1981. Ann. Brit. Sch. Archaeol. Athens 77, 213-48. Qviller, B. 1981. The dynamics of the Homeric society. Symbolae Osloenses 56, 109-55. Renfrew, A.C. 1985. The archaeology of cult: the sanctuary at Phylakopi. (Brit. Sch. Archaeol. Athens Supp. 18). London: Thames & Hudson. Renfrew, A.C. & J.F. Cherry (ed.) 1986. Peer polity interaction and the development of sociocultural complexity. Cambridge: Univ. Press. This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 518 IAN MORRIS Rhodes, J.F. 1987. Early stone working in the Corinthia. Hesperia 56, 229-32. Rich, J. & A. Wallace-Hadrill (eds) in press. City and country in the ancient world. London: Routledge. Robinson, D.M. 1941. Excavations at Olynthus XI: metal and minor miscellaneous objects. Baltimore & London: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. Rolley, C. 1977. Fouilles de Delphes V. 3: les trepieds a cuve clouee. Paris: Editions de Boccard. Rowlands, M.J. 1971. The archaeological interpretation of prehistoric metalworking. Wid. Archaeol. 3, 210-24. 1984. Conceptualising the European Bronze and Iron Ages. In Bintliff 1984. 1986. Modernist fantasies in prehistory? Man (N.S.) 21, 745-6. 1987. The concept of Europe in prehistory. Man (N.S.) 22, 558-9. , M. Larsen & K. Kristiansen (eds) 1987. Centre and periphery in the ancient world. Cambridge: Univ. Press. Runnels, C. 1982. Flaked stone artifacts in Greece during the historical period. J. Fld. Archaeol. 9, 363-73. Rupp, D.W. 1987. Vive le roi: the emergence of the state in Iron Age Cyprus, in Western Cyprus: connections (ed.) D.W. Rupp. G6teborg: Stud. Med. Arch. 77. 1988. The 'Royal Tombs' at Salamis (Cyprus): ideological messages of power and authority. J. Medit. Archaeol. 1, 111-39. Smith, R.H. R. Maddin,J.D. Muhly & T. Stech 1984. Bronze Age steel from Pella,Jordan. Curr. Anthrop. 25, 234-6. Smith, T.R. 1987. Mycenaean trade and interaction in the west central Mediterranean, 1600-1000 B.C. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. Snodgrass, A.M. 1965. Barbarian Europe and Early Iron Age Greece. Proc. prehist. Soc. 31, 229-40. 1971. The Dark Age of Greece. Edinburgh: Univ. Press. 1980. Iron and early metallurgy in the Mediterranean. In Wertime & Muhly 1980. 1983. Cyprus and the beginnings of iron technology in the eastern Mediterranean. In Muhly et al. 1983. 1984. Review of Coulson (1983). Antiquity 58, 152-4. 1987. An archaeology of Greece. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: Univ. of California Press. 1988. Cyprus and early Greek history. Nicosia: Bank of Cyprus. in press. The bronze/iron transition in Greece. In Thomas & S0rensen, in press. S0rensen, M.L.S. 1987. Material order and cultural classification: the role of Bronze objects in the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in Scandinavia. In Hodder 1987. Stavropoulou-Gatsi, M. 1980. Protogeometriko nekrotapheio Aitolias. Arkhaiologikon Deltion 35(1), 102-30. Stech, T. J.D. Muhly & R. Maddin 1985. The analysis of iron artifacts from Palaepahos-Skales. Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus: 197-202. Stech Wheeler, T.,J.D. Muhly, K.R. Maxwell-Hyslop & R. Maddin 1981. Iron at Taanach and early iron technology in the eastern Mediterranean. Am. J. Archaeol. 85, 245-68. Tholander, T. 1971. Evidence for the use of carburized steel and quench hardening in Late Bronze Age Cyprus. Opuscula Atheniensa 10, 15-22. Thomas, R.L. & M.L.S. S0rensen (eds) in press. The archaeology of contextual meanings. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. Waldbaum, J. 1978. From bronze to iron. Goteborg: Stud. Med. Arch. 54. 1983. Bimetallic objects from the eastern Mediterranean and the question of the dissemination of iron. In Muhly et al. 1983. Wardle, K.A. 1980. Excavations at Assiros, 1975-9. Ann. Brit. Sch. Archaeol. Athens 75, 229-67. 1987. Excavations at Assiros Toumba 1986. Ann. Brit. Sch. Archaeol. Athens 82, 313-29. Welbourn, D.A. 1981. The role of blacksmiths in a tribal society. Archaeol. Rev. Cambr. 1, 30-40. Wells, B. 1976. Asine II.4. 1. Stockholm: Skrifter Utgvina i Svenska Institutet i Athen. 1983. Asine 11.4.2-3. Stockholm: Skrifter Utgvina i Svenska Institutet i Athen. Wertime, T.A. &J.D. Muhly (eds) 1980. The coming of the age of iron. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. Whitley, AJ.M. 1987. Style, burial and society in Dark Age Greece: social, stylistic and mortuary change in the two communities of Athens and Knossos between 1100 and 700 B.C. Thesis, Cambridge University. Yener, K. & H. Ozbal 1987. Tin in the Turkish Taurus mountains: the Bolkardag mining district. Antiquity 61, 220-6. Zaccagnini, C.C. 1977. The merchant at Nuzi. Iraq 39, 171-89. This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms IAN MORRIS 519 Circulation, depot et la formation de l'age du fer grec Resume Le commencement de l'age du fer en M6diterran6e Orientale est expliqu6 a pr6sent comme une r6ponse au manque de bronze faisant suite a l'effondrement des syst&mes de palais aux environs de 1200 avant Jesus Christ. Dans cet article, les donnees archeologiques se rapportent davantage aux modeles de depots. La situation consid6ree ici est pour la Grece Antique, et la predominance de fer dans des tombes apres 1050 avantJ6sus Christ est expliqu6e comme un monopole du fer par 1'elite, faisant partie d'un nouveau systeme id6ologique stable et de la montee de communaut6s a petite echelle, repliees sur elles-memes. Cette discussion est importante pour notre comprehension de la cite-etat grecque, pour des debats recents a propos des structures de la societe europeenne du d6but de l'age du fer et pour nos definitions en pr6histoire des 'Ages du Fer'. This content downloaded from 140.112.25.39 on Fri, 24 Mar 2023 13:24:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms