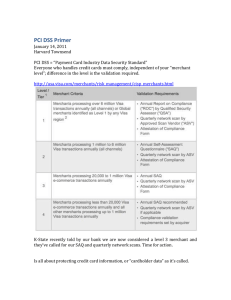

A CRITICAL LOOK AT PAYMENT CARD INDUSTRY DATA SECURITY STANDARDS IMPLEMENTATION IN RESTAURANTS by Kutay Kalkan A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Hospitality Information Management Spring 2009 Copyright 2009 Kutay Kalkan All Rights Reserved UMI Number: 1469501 Copyright 2009 by Kalkan, Kutay All rights reserved INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ______________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 1469501 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. _______________________________________________________________ ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 A CRITICAL LOOK AT PAYMENT CARD INDUSTRY DATA SECURITY STANDARDS IMPLEMENTATION IN RESTAURANTS by Kutay Kalkan Approved: __________________________________________________________ Cihan Cobanoglu, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis Approved: __________________________________________________________ Robert R. Nelson, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Hotel, Restaurant and Institutional Management Approved: __________________________________________________________ Conrado M. Gempesaw, Ph.D. Dean of Alfred Lerner Collage of Business and Economics Approved: __________________________________________________________ Debra Hess Norris, M.S. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writing of a thesis can be a lonely and isolating experience, yet it is obviously not possible without the psychological and practical support of numerous people. Thus, my sincere gratitude goes to the faculty members, my parents and my close friends for their love, support, and patience during this period. First of all, I wish to thank to the person who has completely changed my life. He is Dr. Cihan Cobanoglu; my mentor, chair of my thesis committee and I can even say “my big brother”. He has taken care of me since the first minute I arrived in the U.S.A. and he is one of the few people in the world that I truly trust, respect and follow. He always pushed me for the best and supported me all the time during my master’s degree. Even when he was so busy, he always spared his time to help me out when I got into troubles. Especially in my thesis period, I really cannot think about writing a thesis without his humanity, support, knowledge, encouragement, guidance, inspiration and professionalism. He has been and will be one of the most important people in my life that I will never forget. My appreciation goes to Dr. Brian Miller, my thesis committee member, for his extensive guidance and care on my thesis. What a great honor for me to have had him in my committee! I would also like to present my gratitude to Dr. Srikanth Beldona for everything he has done to make my thesis better. I also want to thank Dr. Fred DeMicco, Dr. Francis Kwansa, Ms. Donna Laws, Dr. Robert Nelson and many other faculty members and staff. I would also like iii to thank Kathie Young for her guidance and understanding throughout my thesis submittal process. My sincere appreciation also extended to my best friend and mentor Erhan Avinal. He has always been there on the other side of the phone to support me and guide me. Whenever I do not mentally feel good, he is just like a medicine to me. He knows how to heal me with his positive energy. On top of that, he has helped me develop “Dr. Recipe”, which saved me a lot of time—maybe the time that I have used for my thesis. He has a very unique brain and heart and he will definitely be one of the people that I will not forget in my life. As I always say, “It is a one in a million chance to find a friend like that”. My special appreciation goes to Anil Bilgihan, who has been a true friend for me since the moment I came here and thanks to him for his friendship and support. My gratitude goes to Jessica Blasik who has helped me a lot and answered my questions patiently. Thank you very much “Blazer”. A special appreciation also goes to my lovely girlfriend, Maris Chen. She has been the only girl in my life that loved me and cared for me unconditionally. She not only has a good heart and a smart brain, but she also has a strong characteristic to deal with a guy like me. She has always supported me and helped me willingly from the heart. No matter what I do, I know I will never be able to pay back for what she has done for me. Finally, my greatest appreciations go to my family. I have always been thankful that I have Aysegul Kalkan as my mother, Ayca Kalkan as my sister, and Vedat Kalkan as the father of the universe. I cannot really express how much I love them. They have all contributed my successes so far, and I am sure they will always be iv there for me no matter what condition they are in. However, there is only one person in my life that I cannot do without. This is my father. He is such a great man that he can sacrifice anything for me without a second thought. He has taught me the real life. He leaded me the way up here and supported me all throughout the way. The thing I like most about him is that he trusts me unconditionally. He is the greatest guy in the world. I love you dad. And of course my mom, she has always been like an angel to me. She has never broken my heart even once. She always gave me her love and prayed for me for the best. I love you mom. I also love my sister a lot. She has always been with me and I love her so much. I would like to thank to my family for everything they have done for me and for letting me feel special because of their invaluable love. Thus, I dedicate this thesis to my father Vedat Kalkan, mother Aysegul Kalkan and my lovely sister Ayca Kalkan. v TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................... viii LIST OF FIGURES......................................................................................................... x ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................xi INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 12 Purpose and Objectives of the Study ................................................................ 12 Background ....................................................................................................... 13 Growth of Credit Card Transactions ........................................................ 13 Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council ................................ 14 Credit Card Breaches in Hospitality Industry .......................................... 15 Definition of Terms .......................................................................................... 16 PCI DSS ................................................................................................... 16 ACH…………………………………………………………….............16 Skimming................................................................................................. 17 EMV……………………………………………………………… .... …17 Merchant .................................................................................................. 17 Service Provider....................................................................................... 17 Network Segmentation ............................................................................ 17 Research Questions ........................................................................................... 18 LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................. 19 What is Identity Theft? ..................................................................................... 20 Current Payment Method .................................................................................. 21 Restaurant Management Systems Affected by PCI DSS Compliance .............. 26 Point of Sale Systems (POS) ................................................................... 26 What Is a Point of Sale System? .................................................. 26 POS Systems and Restaurant Types. ........................................... 27 Costs…………………………………………………………..... 28 Benefits………………………………………………… ............ 31 1. Efficient Transaction Processing. ................................. 31 2. Better Record Keeping. ................................................. 32 3. Effective Use of Information. ....................................... 32 4. Cost Savings. ................................................................ 34 Pay at Table Technologies ....................................................................... 34 The Importance of Pay at the Table Technology ......................... 34 Restaurant Operator Perspective. ................................................. 35 1. Provider Concerns and Market Detractors. ................... 36 vi 2. Benefits and Market Drivers. ........................................ 39 How Card Processing Works? .......................................................................... 41 What is PCI DSS, PCI SSC: A brief history? ................................................... 45 PCI Compliance Enforcement .......................................................................... 48 The Need for PCI DSS Compliance ........................................................ 48 State Legislation ...................................................................................... 50 Merchant Levels and Compliance Validation ................................................... 51 Merchant Level 1 ..................................................................................... 51 Merchant Level 2 ..................................................................................... 52 Merchant Level 3 ..................................................................................... 52 Merchant Level 4 ..................................................................................... 53 Challenges of PCI Compliance ......................................................................... 54 Best Practices .................................................................................................... 58 Compliance in Restaurants ............................................................................... 58 RESEARCH DESIGN .................................................................................................. 61 Instrument ......................................................................................................... 61 Sampling Plan ................................................................................................... 62 Data Analysis .................................................................................................... 63 Limitations and Assumptions ........................................................................... 64 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ................................................................................... 65 Respondent Profile ............................................................................................ 65 Respondent And Company Characteristics....................................................... 66 Company Average Annual Revenue and Business Metrics .............................. 69 IT Characteristics .............................................................................................. 69 Credit Card Acceptance And Integration .......................................................... 73 Use of Wireless Access Points and Security Protocols..................................... 73 PCI DSS Compliance Levels ............................................................................ 74 CONCLUSIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS, AND FUTURE RESEARCH ............... 90 Conclusions and Recommendations ................................................................. 90 Future Research ................................................................................................ 98 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................. 99 vii LIST OF TABLES Table 2.1 PCI Data Security Standard-High-Level Overview. ................................ 47 Table 4.1 Respondent and Company Characteristics ............................................... 68 Table 4.2 Company Average Annual Revenue and Business Metrics ..................... 71 Table 4.3 IT Characteristics ..................................................................................... 72 Table 4.4 Credit Card Acceptance and Integration .................................................. 73 Table 4.5 Use of Wireless Access Points and Security Protocols............................ 74 Table 4.6 PCI DSS Compliance Levels ................................................................... 75 Table 4.7 PCI DSS Total Compliance Levels......................................................... 76 Table 4.8 Tests of normality for organizations’ innovativeness levels ................... 78 Table 4.9 Descriptives and Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis of total compliance by organizations’ innovativeness from a technology perspective ............................................................................................... 79 Table 4.10 T-test results of total compliance by compliance management .............. 80 Table 4.11 Barriers to PCI DSS Compliance ............................................................. 81 Table 4.12 PCI DSS Management ............................................................................. 82 Table 4.13 Non-Monetary Costs of PCI Non-Compliance ........................................ 83 Table 4.14 Attitudes toward PCI DSS ....................................................................... 84 Table 4.15 Perceptions toward PCI DSS ................................................................... 85 Table 4.16 T-test between Grand Perception Mean Scores and Organizational Type ......................................................................................................... 88 Table 4.17 T-test between Grand Perception Mean Scores and IT Governance ....... 89 viii Table 5.1 Research Questions and Summary of the Results .................................... 97 ix LIST OF FIGURES Figure 2.1 Non-cash payments in the United States, selected years ........................ 23 Figure 2.2 Electronic payments in the United States, selected years. ...................... 24 Figure 2.3 Total Costs per Checkout System ($) ..................................................... 30 Figure 2.4 Total Costs per Checkout System ........................................................... 31 Figure 2.5 How Card Processing Works. ................................................................. 43 x ABSTRACT In order to improve the security of customer data, the credit card companies have come together to create a security standard, called Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS), which involve mandatory requirements for merchants that accept credit card transactions. All restaurants that accept a credit card must comply with PCI DSS. The purpose of the study was to evaluate selfreported compliance of Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards version 1.2. in the restaurant industry. A random sample of 1000 restaurant managers that are in charge of information technology at their companies and are subscribers of Hospitality Technology Magazine were surveyed. The findings of this study provide restaurateurs a general idea on the PCI DSS compliance levels of the restaurant industry. Moreover, findings also identifed the barriers to PCI DSS compliance in the restaurant industry for each of the PCI DSS requirements. xi Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION Experian’s National Score Index study showed that U.S. consumers have an average of four credit cards and about 14 percent of the U.S. population use at least 50 percent of their available credit (“Score News Feature,” 2007). According to Privacy Rights Clearinghouse (2007), 8.4 million people in the U.S. were subject to identity theft. The monetary loss was $49.3 billion or an average of $5,720 per victim. Additionally, it took an average of 25 hours to resolve the issue for each victim. As the data above supports, consumers are concerned about the security of their personal information when using their credit cards to purchase goods and services. In order to improve the storage and processing of customer data, the credit card companies have come together to create a security standard, called Payment Card Industry - Data Security Standard (PCI DSS), which involves mandatory requirements for merchants that accept credit card in transactions. As of June 30, 2007, all businesses that process credit card transactions are required to have achieved PCI compliance (“PCI Compliance Deadline”, 2006). However, most U.S. restaurants are still not fully compliant with PCI DSS as of 2008 according to a study conducted by Kalkan, Kwansa and Cobanoglu (2008). Purpose and Objectives of the Study The purpose of this study is to evaluate self-reported compliance of Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards version 1.2 in the restaurant industry. 12 Specifically, this study is attempting to determine the level of compliance of the PCI DSS and if not, what are the barriers to not achieving a full compliance will be examined. Background Growth of Credit Card Transactions As time passed, representations of value became more and more abstract, evolving from barter through bank notes, payment orders, checks, credit cards, and now electronic payment systems (Asokan et al., 1997, p. 28). Rysman (2007) suggested that that the percentage of transactions conducted with payment cards has increased from 12.4% (1994) to 28.9% (2001). Furthermore, according to the American Bankers Association, use of cash fell from %39 in 1999 to %32 in 2003. Today, checks account for just %15 of all store purchases while use of debit cards has risen to 31% of all purchases, up from 21% four years ago. Recent statistics also provide additional evidence in the increase at use of payment cards. In the U.S., nearly 1 in every 3 consumer purchases is made with a payment card including credit, debit, and prepaid products and of every $100 spent by consumers; nearly $40 is in a form other than cash or check (Visa Internal Statistics, 2006). “The advantages of electronic transactions - swift, reliable, and silent - over clunky checks and bulky cash are apparent to consumers” (Epstein and Brown, 2006, p. 12). In addition, electronic transactions are mobile and easy to use. However, just like other electronic technologies, the major drawbacks of using payment cards are privacy and security of the cardholder’s personal information. 13 With the ubiquitous access of the Internet, credit card holder’s personal information has become easier to obtain, especially for professionals (Collins & Cobanoglu, 2008). Identity thieves use personal information such as names, social security numbers, and birth dates to commit fraud and other white-collar crimes in someone else's name (Albany Law Review, 2004). Hackers are phishing for security breaches of data files to break in and steal personal information of customers that use credit cards for the payment of goods and services. Moreover, digital documents can be copied perfectly, often without a trace to the hacker, which further increases the susceptibility of these data. Once digital signatures are produced anybody with knowledge of the secret cryptographic key can gain access to buyers’ personal information that is associated with each credit card transaction (Asokan et al., 1997). Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council The threats identified above have left customers with serious concerns about the security of their personal information. Consumers today are demanding absolute assurance from businesses that their financial and personal information are safe (Kalogeris, 2005). American Express, Discover Financial Services, JCB, MasterCard Worldwide, and Visa International have come together to form the Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council with the mission to enhance payment account data security by fostering broad adoption of network and computer security standards. According to the Council, PCI DSS is multifaceted and includes requirements for security management, policies, procedures, network architecture, software design and other critical protective measures. PCI DSS originally began as five different programs: Visa Card Information Security Program, MasterCard Site Data Protection, American Express 14 Data Security Operating Policy, Discover Information and Compliance, and the JCB Data Security Program (The AHLA PCI, 2008). In the beginning each credit card company’s intentions was similar: to create an additional level of protection for customers by ensuring that merchants meet minimum levels of security when they store, process and transmit cardholder data. In December of 2004, the Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council was formed and the credit card companies aligned their individual policies and created the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards. In September 2006, the PCI standard was updated to version 1.1 to provide clarification with minor revisions to version 1.0. In October 2007, Visa International announced a new Payment Applications Security mandates that are designed to help companies comply with PCI. Visa required these mandates to be implemented by 2010 calling for new merchants that want to be authorized for payment card transactions will have to be using only Payment Application Best Practice - validated applications. These new mandates were designed to help companies achieve Payment Application Best Practice (www.visa.com/PABP) compliance, an implementation of PCI DSS in vendor software. Credit Card Breaches in Hospitality Industry About 55% of credit card fraud comes from the hospitality industry (Cougias, 2008). Similarly, a vast majority of credit card breaches (85%) happen in the smallest merchants (Visa, 2008). In the hospitality industry, there are numerous cases where credit card holder data were breached. One of the most recently publicized data breaches took place in Dave & Buster’s corporate network (McMillan, 2008). Three criminals were charged with hacking into the network and then remotely installing 15 software called “packet sniffer” on the point-of-sale servers at 11 Dave & Buster's locations in the U.S. The criminals used the “packet sniffer” to log credit- and payment-card data as it was sent as plain text, unencrypted form from the branch locations to corporate headquarters. They hacked the network from April to September 2007 and caused significant amount of damage to credit card holders. For example, at the Dave & Buster’s Islandia, New York location, the hackers managed to capture details of about 5,000 payment credit cards, which they sold the information to other criminals who went on to scammed online merchants using the card numbers. The approximate monetary loss stemming from the fraudulent transactions from the 675 cards taken from this one store is US$600,000. Definition of Terms PCI DSS Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards (PCI DSS), is a multifaceted security standard that includes requirements for security management, policies, procedures, network architecture, software design and other critical protective measures. This comprehensive standard is intended to help organizations proactively protect customer account data (PCI Security Standards Council, 2008; Wright, 2008). ACH Automated Clearing House (ACH) is a secure payment transfer system that connects all U.S. financial institutions (ACH, 2000). 16 Skimming Skimming is the theft of credit card information used in an otherwise legitimate transaction (Skimming, 2009). EMV Europay, Mastercard and Visa (EMV) is a global standard for credit and debit payment cards based on chip card technology (“About EMV,” n.d.). Merchant A business entity is directly involved in the processing, storage, transmission, and switching of transaction data and cardholder information (Wright, 2008). Service Provider A business entity that is not a payment card brand member or a merchant directly involved in the processing (Wright, 2008). Network Segmentation Network Segmentation in computer networking is the act or profession of splitting a computer network into sub-networks, each being a network segment or network layer. Advantages of such splitting are primarily for boosting performance and improving security. 17 Research Questions The following research questions were developed to guide this study: 1. To what extent are U.S. restaurants compliant with PCI DSS requirements? 2. Is the level of PCI compliance different based on organizational characteristics? 3. What are the barriers to PCI compliance for restaurants? 4. How is the management of PCI compliance handled? 5. What are the perceived costs of non-compliance of PCI DSS? 6. What are the attitudes and perceptions regarding the requirements of PCI DSS? 7. Do organizational characteristics impact attitudes toward PCI DSS requirements? 8. Do organizational characteristics impact perceptions toward PCI DSS requirements? 18 Chapter 2 LITERATURE REVIEW Although the main purpose of this study was to evaluate self-reported compliance of Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards version 1.2 in the restaurant industry, an extensive literature review was compiled in order to give indepth information of the subject. The literature review employed a funnel approach, explaining the context from general to specific. First of all, the facts about the increase in identity theft and the increase in electronic payment methods were presented to help readers have a better understanding as to why PCI Security Standards council was formed. Then, restaurant management systems which are in the scope of PCI compliance; POS (Point of Sale) and PATT (Pay at the Table) technologies, were explained in detail. In addition, the importance of PATT technologies in reducing consumer concerns about their payment card security was discussed. Provider concerns, market detractors and drivers, and benefits were also discussed to fill in the blanks on the restaurant operator perspective. After that, the workflow of a card processing process was presented. The second part of the literature review has solely focused on issues related to PCI DSS such as the history of PCI SSC (Security Standards Council), PCI DSS and a brief overview of its requirements, PCI compliance enforcement, merchant levels and compliance validation, challenges of PCI compliance, and problems and breaches in the hospitality industry. 19 What is Identity Theft? At the most general level, identity theft is “the misuse of another individual's personal information to commit fraud” (Gonzales & Majoras, 2007, p. 2). According to Pemble (2008), there are two types of financial identity theft: 1) existing account fraud, in which a fraudster chooses not to empty the account and takes over an existing account or credit relationship, and 2) false account creation (new account fraud), in which a fraudster uses personal information to open new accounts and credit dealings on behalf of the victim. Existing account fraud is more common and usually less costly than new account fraud (Anderson, 2006 as cited in Eisenstein 2008). “Although existing account fraud may result in thousands of dollars of charges to a credit card, laws and corporate policy limit consumer liability for such fraudulent charges, and existing account fraud rarely affects an individual's credit rating” (Eisenstein, 2008, p. 1). By contrast; in cases where a new accounts have opened, out-of-pocket expenses for victims were $1,200 on average (Newman & Megan, 2005). Moreover, while an existing account theft is usually over when the victim’s account is closed, new account fraud is more problematic. As a consequence, new account fraud may carry on for years until the thief is caught (as the thief continues to open new additional accounts), which results with a decrease in the victim’s credit rating score (Eisenstein, 2008). Identity theft is the fastest growing crime in America (Eisenstein, 2008). It is estimated that corporations spend over $20 billion on identity theft every year and that consumers spend over $2 billion and 100 million hours of time directly dealing with identity theft crimes. In 2008, the Federal Trade Commission released its annual report detailing consumer complaints about fraud and identity theft for 2007. For the eighth year in a row, the report shows that identity theft is the number one consumer 20 complaint category with a complaint rate of 32% out of a total of 813,899 complaints. The report states that credit card fraud was the most common form of reported identity theft (23%), followed by utilities fraud (18%), employment fraud (14%), and bank fraud (13%). Additionally, consumers reported fraud losses totaling more than $1.2 billion with the median monetary loss per person at $349 (Federal Trade Commission, 2008). However, in light of the previous reported findings, there has been a steady decline in reported identity theft between 2004 through 2007; 42% to 36%, respectively. A 2008 identity fraud survey report confirmed that identity fraud continues to decline but warns that criminals are turning to other channels to commit fraud (Javelin Strategy and Research, 2008a). Current Payment Method In the past, checks and cash have been the major types of payment for purchasing goods and services in the U.S. Yet, “over the years, representations of value have become more abstract, evolving from barter to bank notes, to payment orders, to checks, to credit cards, and now electronic payment systems” (Asokan et al., 1997, p. 28). Research conducted by Rysman (2007) reports that the percentage of transactions conducted with payment cards has increased from 12.4% in 1994 to 28.9% in 2001. According to the findings from the American Bankers Association and Dove Consulting research, consumers are migrating to electronic payments across all payments venues, although traditional paper-based payments continue to be important (ACI, 2008). Over the last 25 years, electronic payment methods’ share of wallet has increased from 15% in 1979 to 55% in 2004. Additionally, consumers migrating from cash and checks to electronic payment methods and the rate at which that change is occurring is escalating. Cash had maintained its share of transactions through 2005, 21 accounting for 33% of consumers’ in-store payments. However, when questioned how their behavior has changed from 2003 to 2005, 45% of consumers reported that they use cash less often than they used to. As a substitute for cash, these consumers are chiefly using card-based payment methods. Of those consumers reporting lower cash usage, 40% reported using credit cards instead, 31% are using PIN debit, 22% use signature debit, and 7% pay with paper checks. According to Gerdes (2008), the use of checks has been declining since the mid-1990s because check payments and some cash payments are being replaced by payments made with electronic instruments such as credit or debit cards. In sum, consumers are using electronic forms of payment much more often than a decade ago, with most of the increase between 2003 and 2006 due to the rise in the number of debit card payments used for purchases of relatively low value ($39 on average). Data previously published by the Federal Reserve show that the number of electronic payments in the United States (made mostly through debit and credit card networks and the automated clearinghouse system) exceeded the number of check payments for the first time in 2003. As seen in figure 2.1, the amount of electronic payments has started surpassing the amount of check payments in 2003 and by 2006 the number of electronic payments was more than twice the number of check payments, or about two-thirds of all non-cash payments. Likewise, the number of payments made over the major electronic payment systems in the United States—the Automated Clearing House system, debit and credit card systems, and the Electronic Benefit Transfer system—grew from 44.1 billion to 62.8 billion between 2003 and 2006, for an annual rate of growth of 12.5 percent ( See Figure 2.2). 22 Source: Total Recent Payment Trends in the United States, Federal Reserve Bulletin, 2008(Oct). Figure 2.1 Non-cash payments in the United States, selected years 23 Source: Total Recent Payment Trends in the United States, Federal Reserve Bulletin, 2008 Figure 2.2 Electronic payments in the United States, selected years. The electronic payments study by The Payment Cards Center of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, also obtained a similar prediction about payment trends. It estimated that by 2007 paper payments would drop to 57% from the 67% of paper payments in 2002 and electronic payment would represent about 43% in the payment mix (cash, debit, credit, ACH, check and others). Further predictions from this study were that there would be 30 billion transactions per year and debit card volume will grow 25% to 30% percent per year and ACH volume will grow by 15% per year (The Payment Cards Center, 2003). 24 Although cash is still widely being used for small dollar transactions, the advantages of increased speed and convenience of the recent payment formats such as credit/debit cards and innovative contactless payment systems will likely keep on hampering the use of cash as a payment method (Kasavana, 2006). According to the results of the 2006 Payment Trends Summary report (Visa U.S.A. Inc., 2006), payment method by share of dollar volume for cash at quick service restaurants in the United States went down from 87% in 1999 to 66% in 2005, while credit and debit card payments went up from roughly 1.5% in 1999 to 14.5 percent in 2005. As for midpriced restaurants (casual-dining), payment method by share of dollar volume for cash went down from 56% in 1999 to 36% in 2005, while debit cards went up from 27% to 36% and credit cards went up from 9% to 23% in the same time interval. Although not as much as mid-priced and quick service restaurants, electronic methods of payment at high-priced restaurants also augmented. Payment method by share of dollar volume for cash at high-priced (fine-dining) restaurants went down from 35% in 1999 to 20% in 2005, while debit cards went up from 6% to 12% and credit cards went up from 51% to 59% in the same time interval. Consumers keep using their credit cards at this type of restaurants for their convenience as well as earning reward points associated with using these cards. As reported by a more recent online consumer survey, which is conducted in June 2008, 68% of the payments in restaurants were made in credit and debit cards, while cash accounts for 30% and check accounts for 2% (First Data, 2008). The reason why cash alone accounts for 30% is because of inexpensive purchases and unavailability of other forms of payment. Still, it does not affect the popularity of electronic forms of payment in the restaurant industry. 25 Restaurant Management Systems Affected by PCI DSS Compliance “To compete effectively in today's saturated restaurant markets, all stages of food-service production and service must operate in concert so as to ultimately deliver quality products at the right price to the right guests at the right time” (Sill, 1994, p. 1). Not conforming to this judgment may lead to unnecessary costs, underutilized capacity, poor guest service, poor food quality and excess inventory. However, this is not an easy task without having necessary restaurant technologies effectively implemented into the restaurant operations. Some of the most common technologies available for restaurateurs are as follows: 1. Point of sale (POS) systems 2. Kitchen display systems 3. Inventory control systems 4. Menu management systems 5. Home delivery software 6. Pay at table technologies (PATT) In this study, only the POS systems and PATT will be detailed as the other systems are out of the scope of the PCI DSS compliance. Point of Sale Systems (POS) What Is a Point of Sale System? In the most basic sense, a point of sale system is a computerized substitute for traditional cash registers. To give more detail, “a point of sale system is a network of cashier and server terminals that typically handles food and beverage orders, 26 transmission of orders to the kitchen and bar, guest-check settlement, time keeping, and interactive charge posting to guest folios” (Collins & Cobanoglu, 2008, p. 245). Moreover, data kept in a POS system can be imported to accounting and inventory management systems. Reports that can be generated include open check, labor cost, tip, menu mix, sales analysis, cashier, void/complimentary, server sales summary and so on. The type of reports may go up to 200 depending of the capabilities of a specific POS terminal. POS Systems and Restaurant Types. In retail style restaurants like sub shops, POS systems generally do not need to include printers in the food preparation as production has already occurred. Therefore the POS acts as an inventory control tool. In quick-service restaurants, POS systems are absolutely crucial as they make the transaction process quicker. Orders taken on terminals in the front are displayed on monitors in the kitchen, ready to be quickly prepared and then delivered to the customer (Sacco, n.d.). POS systems for table-service restaurants are rather different. These systems need to be set up with a menu and a seating plan (Collins & Cobanoglu, 2008). These systems can handle transactions, forward orders to the kitchen and bar, track reservations and seating. As to fine dining POS systems, characteristically they should include more stations: multiple server stations, a bar station, a hostess station, and printers in the kitchen than more basic POS systems. They also have more functionality such as creating and storing open checks. On top of that, they let servers track which server is responsible for which table, as well as send "fire" orders to the kitchen to start the next course. 27 Costs The more consumer demands increase, the more focus is being placed on the consumer shopping experience by retailers (Perry & Witty, 2006). The fact that retail industry is dominated by a couple of enormously large players, along with this strategy above, retailers need to challenge the way they do business in order to distinguish themselves in innovative and effective ways. IT managers in the hospitality industry are striving to find the best ways to meet the opportunities and challenges regarding this transformation. Regarding the POS systems, retailers are going for long-term solutions because they think the in-store technology should support their business for several years. Hence; pros, cons, and costs of the POS devices must be clearly set down to support retailer spending decisions. Lately, there has been an ongoing prejudice that POS systems are more expensive to purchase and maintain than PC Cash Drawer (PCCD) technologies. However, this is not the case. According to Collins & Cobanoglu (2008), although the average cost of a POS system, including installation, is about 20,000$; the pay-back period is claimed to be less than 2 years. Likewise, Perry and Witty (2006) supports that POS systems are more expensive to purchase compared to PCCD systems; however, they start paying back a year after the acquisition. After five years of use, PCCD costs on average over 31% more than POS. Beyond the total costs, Perry and Witty’s research and analysis uncovered the following findings: 1. When analyzed individually, system hardware costs, peripheral costs, software costs, and staffing costs are all cheaper over the life of a POS system than a PCCD system; 28 2. POS systems offer improved customer experience by speeding up transactions by 44% while delivering 15% improved availability over PCCD; 3. Asset utilization of POS systems is greater than that of PCCD systems due to the lower costs per customer served and longer life span of POS systems. (p. 2) Formerly, PCCD solution providers put emphasis on low cost and provided basic solutions with few peripherals customized to the specialized retail environment. PCCD was advantageous up front with respect to cost. Nevertheless, because of the capabilities gap, customers were paying less and getting less. Today, PCCD solutions come with more capabilities. As a result, the initial cost differential has decreased, and in some cases, initial hardware and software costs now favor POS. Still, we can say that POS systems generally have higher initial costs than PCCD, mainly because of the installation labor costs (see Figure 2.3 and Figure 2.4). However, POS’s lower operating costs mean that within the first year, POS becomes the lower-cost solution. After three years, because of operational costs, PCCD is 30% more expensive, and at five years, the gap widens to over 31% as PCCD customers replace 100% of their systems, an expense POS customers will not encounter for another two to three years. 29 Source: IDC White Paper sponsored by IBM, Total Cost of Ownership for Point-ofSale and PC Cash Drawer Solutions: A Comparative Analysis of Retail Checkout Environments, 2006 Update, Doc # 203766, November 2006. Figure 2.3 Total Costs per Checkout System ($) 30 Source: IDC White Paper sponsored by IBM, Total Cost of Ownership for Point-ofSale and PC Cash Drawer Solutions: A Comparative Analysis of Retail Checkout Environments, 2006 Update, Doc # 203766, November 2006. Figure 2.4 Total Costs per Checkout System Benefits The process of buying a new POS system or even upgrading a current one is undoubtedly time, labor and money intensive; however, there are clear gains once it is installed and then maintained regularly. 1. Efficient Transaction Processing. According to a survey regarding guest-check accuracy, which was conducted by Kelly and Carvell (1987), the main reason of the inaccuracy of a handwritten check is arithmetic errors. Besides, approximately one in eight checks were 31 inaccurate, and 70% of those inaccurate checks resulted in undercharging the guest. Inaccuracy of a check may cause loss of revenue, lower tips or dissatisfied customers. A good POS system is capable of reducing or even eliminating any human errors that occur in merchant processing of transactions (ResourceNation, n.d.). For instance, most restaurants that do not use POS systems are vulnerable to the risk of order errors due to poor communication between waiters and kitchen staff. Some retail stores have different terminals for sales computation and credit card processing. A good POS system can fix these problems, reducing employee error and making communication between different parts of the business much easier. 2. Better Record Keeping. POS systems standardize the format and recording of transactions, keeping a record of daily sales that is organized and easy to understand. This is very useful to restaurants because they rely on precise records like calculating tips for employee tax information. A POS system also records every piece of information for each server, listing average guest check, items sold and total sales. That specific information can then be used for job evaluations, motivational programs (e.g., wine contest), assessing merchandising skills (e.g., average guest check and item sales) and server efficiency (e.g., sales per hour). 3. Effective Use of Information. Regardless of manufacturer and model, POS systems allow a business to use information more effectively, which is one of the most important factors to choose them. For example, most POS systems have reporting functions, where a business owner can generate a list of sales and cost information by employee, meal period, 32 outlet, register, table, category, date, or menu item for any given time period (e.g., hourly, daily, weekly). If a restaurant is deciding whether or not to place an order for a certain product, a detailed outline of all past sales information can be queried, which is a feature of inventory management systems by nature, through the POS system. Moreover, sales report gives the restaurant operator an idea about items that are being sold more at a certain time of a year, a day of a week, or even an hour of a day. Hence, ordering decisions will be more strategic and effective. Tracking promotions and special offers through POS systems are very useful. For example, reports can be generated to find out how many drinks were sold at a discounted price during a happy hour. Then, that information can be compared to past or future reports regarding the same guests to see if those guests purchase those drinks at full price once the promotional period is over. On the strength of those information, a restaurateur can determine which promotions are beneficial, and plan better for the future. Information that is acquired from a POS system also allows operators to pinpoint problematic areas undermining profitability such as a declining average guest check during lunch, excessive labor hours in the kitchen, a changing menu mix, or sluggish liquor sales (Collins & Cobanoglu, 2008). Some POS systems present information on table turnover and utilization, too. This can be used to evaluate station sizes, service style, dining room table mix, server and kitchen efficiency, and seating and reservation policies. 33 4. Cost Savings. As stated in the “costs” section, a POS system’s overall cost is lower than traditional cash registers. That is claimed to be the most important reason for businesses to go with POS systems (ResourceNation, n.d.). POS systems are built for productivity, speed and efficiency. For example, it may be a hassle for a restaurateur to keep track of the inventory. With computer generated reports, restaurants not only save time but also are able to pinpoint and target loyal customers to increase profits. Moreover, a good POS system makes it hard for employees to give unnecessary discounts of free merchandize away because inventory is better controlled. A POS system may also eliminate the need for cashier positions by assigning that responsibility to servers that carry their own transaction devices (Collins & Cobanoglu, 2008). Other cost-saving features are as follows: 1. POS systems also eliminate the need for stand-alone credit card terminals as they are already attached to the system; 2. Only one telephone line or internet connection is enough to support a POS network; Discrepancy between a sale amount and the amount of the charge on the credit card will never occur. Thus, there will be no need to go back and match individual sales when the credit card batch does not match credit card sales. Pay at Table Technologies The Importance of Pay at the Table Technology. With the help of the advantages of wireless technologies (Bluetooth, GPRS and wi-fi) such as high transaction speeds as well as reliability and performance (Koroneos, 2008), Pay at the Table (PATT) technologies started taking attention of 34 restaurateurs. Table-top payment terminals, mobile payment terminals (table-side), newly emerging Near Field Communications (NFC) and pay-by-wrist method can theoretically be considered as PATT technologies. However, as the usage of NFC and pay-by-wrist technologies have not been widely embraced by restaurant operators yet; only table-top and table-side payment systems will be mentioned in this study. Basically, PATT, whether it is a table-top or table-side payment, is a technology that allows customers to pay bills without their credit or debit cards leaving their sights. Considering the fact that about 55% of credit card fraud comes from the hospitality industry (Cougias, 2008), along with the estimation that more than 70% of card skimming occurs at restaurants (“The Skinny on Skimming,” 2007); consumers are now more concerned about the security risks involved in losing sight of their credit cards (“Why make a meal of customer payments?,” 2005). Moreover, a recent study presents that 60% of consumers are concerned about the safety of the current card payment process in table service restaurants (As cited in Verifone, 2007). Restaurant Operator Perspective. Although the payment industry had a leap forward with the emerging PATT systems, it is a relatively new phenomenon outside of France and Canada (Payment-at-table, 2004). The United States is about 10 years behind the curve (Coomes, 2007). However, consumer demands and reduced costs for the restaurant operator will accelerate PATT acceptance in the United States. In addition, with the help of the developments in the business climate and the technologies such as Bluetooth, GPRS and Wi-Fi; terminal manufacturers now believe that they are able to penetrate other country markets, as well (“Why make a meal of customer payments?,” 2005). 35 Today, the world economy is on the edge of a severe global economic downturn and the United States is no exception for that. According to United Nations’ (2008) , economic growth in the United States was expected to show a decline in 2008, and a wide array of macroeconomic indicators are already alluding to a recession: employment is in decline, consumer confidence has dropped to the lowest level in a decade, household spending growth has slowed sharply, and business equipment spending is slowing. Recession also hit the restaurant industry. Restaurants are closing, samestore sales are falling and employees are losing their jobs (Horovitz, 2008). Likewise, recession has a negative effect on people’s tendency to eat out. People are less likely to spend money in today’s environment; and when they do, they want to feel secure (Richardson, 2008). On the other hand, the restaurant industry is one of the last frontiers in terms of customers giving up possession of credit cards so as to complete sales (Murphy, 2007). Thus, restaurant operators should carefully analyze the market drivers and detractors for PATT technologies and take appropriate actions accordingly. 1. Provider Concerns and Market Detractors. Even though restaurants are early adopters of payment methods, fullservice restaurants have been left behind by emerging payment trends because their conventional stationary POS systems may not be able to support customer activated routines such as table-side PIN entry (Murphy, 2007). Other than security issues— customers are not comfortable with losing sight of their credit cards—, not providing PIN-debit transaction option to customers may lead to lost market share to signaturebased debit transactions (Kasavana, 2006). This would have a negative impact to net income as PIN-debit transactions have a lower interchange fee and higher processing 36 speed (the movement of the money from one account to the other) compared to credit cards or signature-debit transactions. Another concern of restaurateurs is the reliability and security of the wireless payments. Security of the communication between the wireless devices (mobile payment systems, laptops etc.) requires an additional layer of security to prevent non-authorized devices from accessing the network to intercept payment data from POS devices. So, restaurants that use PATT technology installed on a wi-fi network should pay attention to security measures and PCI DSS compliance requirements as wi-fi networks are more susceptible to security attacks (Collins & Cobanoglu, 2008, p. 86). Moreover, restaurateurs should also be careful about choosing wireless ordering devices as some of them may not be capable of achieving PCI PED approval, which is required by PCI Security Standards Council (“PIN Entry Devices,” n.d.), mostly because they depend on open system software and development tools, and they lack hardware-based security (Verifone, 2007). Other than those mentioned above, there are barriers to PATT systems, especially in areas such as cost and technology (“Why make a meal of customer payments?,” 2005). Some of the detractors are as follows: 1. Restaurants operate in a mixture of environments from open spaces to cozy basements. Each environment will have different technical requirements (eg. GPRS may not work at every table of a restaurant); 2. Confusion amongst decision makers about the technologies and how they work; 3. Fear that it may not be possible to conduct wireless mobile payments reliably and securely; 4. Connectivity of applications to back office and end-to-end solutions; 37 5. Portable terminals are still more expensive than countertop terminals; 6. Some portable devices are too large and heavy; 7. End user acceptance of PIN; 8. 9. Transaction times on some solutions are too slow, with the extra time taken magnified in the eyes of customers when a waiter is standing in front of the customer waiting for feedback; Reliability and performance of the terminal. 10. Costly wireless devices may be stolen or damaged. Although there are some serious detractors such as monetary and nonmonetary costs of moving from traditional POS systems to PATT systems, the move will pay for itself and leave customers more satisfied and secure. Costs also contribute to provider concerns and market detractors. There are a number of costs in installing a PATT system into a restaurant. On the hardware side, there are the costs of the hand-held units, magnetic strip readers, batteries, coffins to charge the batteries, cradles, routers, warranties and accessories (Brooks, 2008). The approximate cost would be $25,000 for 15 wireless devices to run in a 6,000 sq/foot restaurant. On the software side, POS licenses may go up to $7,500. Lastly, the cost associated with installation, training and wiring may run near as much as $11,000. Even though portable terminals are somewhat expensive, waiting staff productivity might increase up to 33%. Additionally, as only one telephone connection is enough for multiple terminals, telecommunication costs will decrease (“Why make a meal of customer payments,” 2005). If quick service restaurants are the case, a PATT system would cost considerably less as they will have terminals only at the counters and drive-through window (Coomes, 2007). 38 2. Benefits and Market Drivers. One of the most important reasons for a restaurant to embrace PATT systems is providing a more secure environment for customers to make their payments to reduce card fraud and identity theft (Coomes, 2007). In a study of measuring service quality states that service quality leads to customer satisfaction (Cronin & Taylor, 1992). So, the second most important reason could be the speed of check settlement as it improves customer satisfaction. Steiger also emphasizes the importance of swift transactions by saying, “Customers hate to wait, and sometimes I have waited 11 minutes for the server to come back with my card when I paid the bill. To be able to swipe your card, close the transaction and leave the device on the table…customers will love that” (Coomes, 2007, p. 2). The strongest and most tangible evidence of PATT’s speedy check settlement is that it reduces the steps required to complete a transaction. Today, in a table service setting such as a fine dining restaurant, the credit card transaction process requires eight steps: 1. Customer requests check; 2. Server brings check and leaves; 3. Server comes back to table to pick up credit card; 4. Server takes credit card back to POS system for initial transaction—without tip; 5. Server returns to table with check and card; 6. Customer puts on the tip and signs the receipt; 7. Server goes back to table to pick up check; 8. Server or manager edits the tip in the POS system—secondary transaction. 39 On the other hand, PATT makes that process as simple as three steps: 1. 2. 3. Customer asks for check; Server brings mobile payment device to the table, pulls up the correct guest check, and leaves the device with the customer to complete the transaction, including automatic tip calculation options, and automatic receipt printing. Server picks up terminal and receipt. Including those, the benefits of PATT technologies can be summarized as follows: 1. Improves customer service through reduced wait time for tables and check settlement (Verifone, 2007); 2. Offering multiple payment options including PIN-debit; 3. Increased table turns and capacity, and in return, higher return on investment (Koroneos, 2008); 4. Reducing ordering mistakes stemming from manually writing down orders and then entering them into a free standing POS terminal (Brooks, 2008); 5. Reducing the liability of restaurants in the case of a fraud, since all PATT transactions are card-present and are closed by the customer (Coomes, 2007); 6. Reducing fraud and customer fears of identity theft while sticking to PCI DSS requirements (Brooks, 2008). Along with these general advantages of PATT systems, restaurateurs who choose to install table-top devices may gain additional benefits. As these systems let customers pay at any time during their meal, there is no waiting for the waiter. Thus, the transaction time is even more reduced than tableside payment processes. Mary Russo, president and COO of Food, Friends and Company, a restaurant management company that operates 13 restaurants in nine 40 states, said that out of 1000 customers that they surveyed, 80% of the customers said they would prefer table-top payments to table-side payments (Mastroberte, 2008). Secondly, because of the nature of using these systems, customers never hand their payment cards out to a waiter. Having full control over their payment cards not only makes them feel more secure in terms of fraud, but restaurateurs also reduce their responsibilities on their customers’ payment cards. Lastly, those systems are very useful and attractive. They have features such as automatic tip calculation, splitting checks, and even emailing or printing the receipt for customers (“Pay-at-the-Table,” n.a.). Along with those advantages of PATT systems, significant market drivers are evident in many countries (“Why make a meal of customer payments?,” 2005). A summary of the market drivers related to PCI DSS are as follows: 1. The need to update terminals to comply with EMV; 2. Chip and PIN principle means cardholders should never lose sight of their cards; 3. Developments with wireless communication technologies such as Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi; 4. Tip entry features on terminals reduce errors and fraud; 5. News coverage about identity theft and skimming has resulted in more consumers expecting higher levels of privacy and security. How Card Processing Works? When a customer pays for products or services with a credit card, the card information is recorded—either by manual entry, a card imprinter, point-of-sale (POS) terminal, or virtual terminal—and then verified so that the merchant can receive 41 payment for the transaction (“How Card Processing Works?,” n.d.). This process involves the following parties: 1. Cardholder: the owner of the card used to make a purchase. 2. Merchant: the business accepting credit card payments for products or services sold to the cardholder. 3. Acquirer: the financial institution or other organization that provides card processing services to the merchant. 4. Card association: a network such as VISA® or MasterCard® (and others) that acts as a gateway between the acquirer and issuer for authorizing and funding transactions. 5. Issuer: the financial institution or other organization that issued the credit card to the cardholder. 42 Source: Bank of America. How Card Processing Works? Figure 2.5 How Card Processing Works. The flow of information and money between these parties—always through the card associations—is known as the interchange, and it consists of a few steps: 1. Authorization. The cardholder pays for the purchase and the merchant submits the transaction to the acquirer. The acquirer verifies with the issuer—almost instantly—that the card number 43 and transaction amount are both valid, and then processes the transaction for the cardholder. 2. Batching. After the transaction is authorized it is then stored in a batch, which the merchant sends to the acquirer later to receive payment (usually at the end of the day). 3. Clearing and Settlement. The acquirer sends the transactions in the batch through the card association, which debits the issuers for payment and credits the acquirer. In effect, the issuers pay the acquirer for the transactions. 4. Funding. Once the acquirer has been paid, the merchant receives payment. The amount the merchant receives is equal to the transaction amount minus the discount rate, which is the fee the merchant pays the acquirer for processing the transaction. The entire process, from authorization to funding, usually takes about 3 days. However, Merchant Card Processing from Bank of America offers next-day deposits to customers with a Bank of America business checking account. In the event of a chargeback (when there's an error in processing the transaction or the cardholder disputes the transaction), the issuer returns the transaction to the acquirer for resolution. The acquirer then forwards the chargeback to the merchant, who must either accept the chargeback or contest it. During these processes, the card holder information is sometimes breached by internal or external hackers. In the case of a breach, the credit card company assumes the financial responsibility provided that merchants did accept the payments in regulations (i.e. check the signature of the customer with the back of credit card). However, the financial assumption for these frauds increased so much that credit card companies wanted to pass some of the responsibility to the merchants in protecting the card holder information. The next section will talk about the fruit of these initiatives by credit card companies. 44 What is PCI DSS, PCI SSC: A brief history? As stated previously, there has been a considerable increase in the adoption of electronic payment forms and systems, both by consumers and by providers. Unfortunately, this increase has yielded to many security concerns about the security of electronic payment systems and identity theft. Consumers want and need absolute assurance from businesses that their financial and personal information are safe (Kalogeris, 2005). Because of these concerns and the increase in the number of security breaches in various industries; American Express, Discover Financial Services, JCB, MasterCard Worldwide, and Visa International came together to form the PCI Security Standards Council (PCI SSC), an open global forum for the development, enhancement, dissemination and implementation of security standards for account data protection (Laredo, 2008). Actually, each company had their own security programs before the unification. The American Express program is called Data Security Operating Policy (DSOP); the Discovery program is called Discover Information Security and Compliance (DISC); The MasterCard program is called MasterCard Site Data Protection (SDP); and the Visa program is called Cardholder Information Security Program (CISP) (“History of the PCI,” n.a.). Companies processing each of those cards had to be compliant with each security programs separately (“Payment Card Industry,” n.a.). For example, if a company was processing VISA and MasterCard, then it had to be compliant with CISP and SDP. However, after the unification of those companies in September 2006, the agreement amongst the industry had changed. According to the council, if a merchant is VISA CISP compliant, all other companies, MasterCard, American Express, 45 Discover Financial Services, and JCB international will honor the CISP compliance and consider that particular merchant as PCI compliant. Right after the unification, the council released PCI DSS version 1.1. Since then, it has rapidly become one of the most important concerns of both merchants and service providers. In October, 2008, PCI SSC announced general availability of version 1.2 of the PCI DSS in their press release (PCI Security Standards Council, 2008). This latest version is considered to be the culmination of two years of feedback and suggestions from its industry stakeholders and is designed to clarify and ease implementation of the foremost standard for cardholder account security. Version 1.2 took effect immediately and the deadline for the transition from version 1.1 to version 1.2 of the standard was on Dec. 31, 2008. However, Version 1.2 did not change the major requirements. The main purpose of it was to enhance clarity, improve flexibility, and address evolving risks and threats. PCI DSS requirements are designed for use by assessors conducting onsite reviews for merchants and service providers who must validate compliance with the PCI DSS. Below is a high-level overview of the 12 PCI DSS requirements: 46 Table 2.1 PCI Data Security Standard-High-Level Overview. Build and Maintain a Secure Network Requirement 1: Install and maintain a firewall configuration to protect cardholder data Requirement 2: Do not use vendor-supplied defaults for system passwords and other security parameters Protect Cardholder Data Requirement 3: Protect stored cardholder data Requirement 4: Encrypt transmission of cardholder data across open public networks Maintain a Vulnerability Management Program Requirement 5: Use and regularly update anti-virus software Requirement 6: Develop and maintain secure systems and applications Implement Strong Access Control Measures Requirement 7: Restrict access to cardholder data by business need-to-know Requirement 8: Assign a unique ID to each person with computer access Requirement 9: Restrict physical access to cardholder data Regularly Monitor and Test Networks Requirement 10: Track and monitor all access to network resources and cardholder data Requirement 11: Regularly test security systems and processes Maintain an Information Security Policy Requirement 12: Maintain a policy that address information security Source: PCI Security Standards Council. PCI DSS version 1.2., 2008(Oct), p 3. Each requirement has sub-requirements as much as 20, and some even have sub-sub-requirements. For example, requirement 3, protecting stored cardholder data, provides several sub-requirements, which range from “keeping cardholder data to a minimum” to “not storing sensitive authentication data after authorization”. The latter requirement again has sub-requirements and for every requirement, testing procedures are clearly stated for the use of merchants and service providers. As to requirements 11 and 12, which are “regularly testing security systems and processes” and “maintaining a policy that addresses information security”, contains elements that are less intuitive (Rowlingson & Winsborrow, 2006). The former requirement includes a sub-requirement for intrusion detection and/or 47 prevention functions while the latter addresses a range of security management functions, including matters such as incident response and management of third party relationships. All of the PCI requirements apply to all network components, whether it is software or hardware, included in or connected to the card-holder data environment. Network components include firewalls, switches, routers, wireless access points, and other security appliances while software components include all off-the-shelf and custom applications including intranet and Web-applications. Server types include, but are not limited to those for database, authentication, application, mail, DNS (Domain Name Server), NTP (Network Time Protocol) and proxy. PCI Compliance Enforcement The Need for PCI DSS Compliance Unlike legal and regulatory compliance, such as the US Sarbanes-Oxley Act 2002 (monitored and enforced by the US Security and Exchange Commission SEC), or the UK Data Protection Act 1998 (monitored and enforced by the UK Information Commissioner’s Office); PCI DSS is a ‘contractual’ requirement between the merchants and service providers, including the hosting providers (Wright, 2008). PCI compliance is enforceable by the credit card brands through contractual penalties or sanctions (Wright, 2008). Sanctions for failure to comply may include fines or revocation of the company’s right to accept or process credit card transactions. For some organizations, this would significantly affect their ability to maintain their business and may result in bankruptcy. On top of these penalties, there are also additional drivers and benefits for being PCI compliant. 48 Non-compliance with the PCI DSS may result in fines up to $500,000 per data compromise and in the United States, additionally the government may charge firms penalties for negligence of $5 million to $20 million. Avoiding these large fines is one the important benefit to being PCI DSS compliant. If a company is found to be compliant at the time of a data compromise, the company will not be fined (Bradly, 2007). However, the company will most probably be taken to a civil court regardless of the compliance status, but it is likely that jury will be much more sympathetic because of the company being in PCI DSS compliance. Other monetary advantages are found in incentives. In December 2006, Visa USA announced their PCI Compliance Acceleration Program (CAP). Merchants who were in compliance with their standards had a chance to receive a one-time payment incentive. Contrastly, Visa USA, as part of the CAP program, maintain that acquirers that have not validated PCI compliance of their merchant clients by October 1, 2007, will not be eligible for a discount in the interchange rates. PCI compliance can have a positive effect on stockholder value, consumer confidence and overall risk reduction for the operation (Meadowcroft, 2008). However, if a company involved in a data breach becomes public knowledge, that company would have difficulty doing business after the damage to their reputation and has to deal with addressing trust issues with their shareholders (Dallaway, 2008). Moreover, 40% of consumers report that they will not deal with a company they know has been breached (Bradly, 2007). Last but not least, in the case of a data breaches, the company is held liable for paying the full costs of a forensic investigation by a PCI certified forensic investigator (Owen & Dixon, 2007). This investigation will affect the bottom line of 49 the organization, as well as cause considerable disruption to their systems and network as servers are taken offline and systems are frozen to preserve evidence. State Legislation Currently, as Morse and Raval (2008) have stated “Neither the PCI SSC nor its participating organizations have any independent legal authority to enforce those standards” (p. 551). However, several states are beginning to change the accuracy of this statement. California and Minnesota are all beginning to enact state legislation that are placing components of the PCI Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) into law. Additionally, there is a big push by state legislatures and industry trade associations to enact a federal law around data security and breach notification. The state of California has taken the lead in this area by providing a comprehensive statue for consumer protection which states (Morse & Raval, 2008): “A business that owns or licenses personal information about a California resident shall implement and maintain reasonable security procedures and practices appropriate to the nature of the information, to protect the personal information from unauthorized access, destruction, use, modification, or disclosure.” Besides, businesses that deal with nonaffiliated third parties are required to contract for such protections on behalf of their patrons. Waiver of these protections is outlawed as contrary to public policy. Customers exposed to a security violation may institute a civil action for damages. In 2007, Minnesota established the “Plastic Card Security Act” which states that any company that is breached and is found to have been storing “prohibited” PCI data (e.g., magnetic stripe , CVV codes, track data etc) are required to reimburse banks and other entities for costs associated with blocking and reissuing cards (Young, 50 2009). This law also opens up these companies to private lawsuits. Currently, this law does not affect merchants processing up to 1 million VISA transactions per year. Massachusetts recently announced that it will introduce a new law, 201 CMR 17.00, which pulls some important concepts from the PCI DSS. For example, the law has requirements around limiting the type of data collected, requiring written security policies, and data encryption. This law would apply to any company who has customer data (or handles it) from customers based in Massachusetts. Recently, compliance enforcement of this law was pushed back until 2010, but unlike previous laws, this one does not have a stipulation that excludes Level 4 merchants from complying with the legislation. Merchant Levels and Compliance Validation Basically, any organization that processes credit card transactions must be in compliance with the PCI DSS regardless of the size of the organization. However, there are various levels of compliance proof or validation required based on merchant levels. As specified in the Visa website, merchants are categorized according to the volume of transactions processed annually and the potential risk and exposure they introduce into the payment system. Each merchant classification has been charged with different levels of compliance tasks. The following is the list of the merchant levels along with their compliance tasks (“Compliance Validation,” n.d.). Merchant Level 1 Defined as: 1. Any merchant-regardless of acceptance channel-processing over 6,000,000 Visa e-commerce transactions per year; 51 2. Any merchant that has suffered a hack or an attack that resulted in an account data compromise; 3. Any merchant that Visa, at its sole discretion, determines should meet the Level 1 merchant requirements to minimize the risk to the Visa network; 4. Any merchant identified by any other payment card brand as Level 1. Merchant Level 1 Compliance Tasks: 1. Annual Report on Compliance (ROC) by Qualified Security Assessor (QSA). 2. Quarterly Network Scan by Approved Scan Vendor (ASV). 3. Attestation of Compliance Form. Merchant Level 2 Defined As: Any merchant processing 150,000 to 6,000,000 Visa ecommerce transactions per year. Merchant Level 2 Compliance Tasks: 1. Annual Self-Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ). 2. Quarterly Network Scan by ASV. 3. Attestation of Compliance Form. Merchant Level 3 Defined As: Any merchant processing 20,000 to 150,000 Visa ecommerce transactions per year. Merchant Level 3 Compliance Tasks (same as a merchant level2) 1. Annual SAQ. 2. Quarterly Network Scan by ASV. 52 3. Attestation of Compliance Form. Merchant Level 4 Defined As: Any merchant processing fewer than 20,000 Visa ecommerce transactions per year, and all other merchants processing fewer than 1,000,000 Visa transactions per year. Merchant Level 4 Compliance Tasks 1. Annual SAQ (recommended but not mandatory). 2. Quarterly Network Scan by ASV (recommended but not mandatory). 3. Compliance validation requirements set by acquirer. However, the cost and complexity of establishing PCI DSS-compliant transaction architecture is challenging. “The time required by retailers to establish total end-to-end compliance on their own, compounded with the time and expense of PCI DSS audits by third-party security certification companies, build a compelling case for working with vendors and service providers who can make the job easier” (“PCI Compliance,”2007). While some companies develop, deploy, assess and test a compliance strategy on their own, others find that there are certain advantages of using a thirdparty vendor for these activities. For some organizations, an outside vendor can provide external validation of the appropriateness of the processes and policies. This action provides reassurance to customers, partners, shareholders and card issuers. Most importantly, a third-party vendor can also provide an objective analysis of current compliance status and gives recommendations for closing any gaps (“Profiting from PCI Compliance,” 2007). 53 When compliance validation is not outsourced, company officials become fully liable for any omissions or errors. Using a third-party vendor helps spread the risk carried by corporate management. However, companies have the chance to conduct their own penetration testing if they prefer. Nevertheless, external network scans are required for the majority of merchants and service providers, and these scans must be performed by an approved third-party assessor. When companies reach a certain number of payment card transactions, a certified PCI assessor must validate PCI compliance. The PCI Security Standards Council manages a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) program in order to ensure that assessors are fully certified to conduct PCI assessments. Challenges of PCI Compliance Considering the fact that PCI DSS compliance levels (between 50% and 80%) are still not satisfying (Lorden & Skorupa, 2008), it would be wise for merchants to pinpoint the challenges and align their compliance strategies accordingly. Identified below are some general challenges to PCI compliance, and strategies for overcoming those challenges. First of all, there is a general confusion about who will be responsible for compliance and who will be held liable if a breach takes place. As mentioned earlier, any organization that processes, stores or transmits credit card data should comply with PCI DSS. On top of that, many merchants assume that service providers (POS system or payment processor vendors) owns the risk if they have a simple agreement add-on that mentions PCI. However, according to the latest findings from the PCI Knowledge Base (Taylor, 2008), breach rate occurred at a third party is 75% of all forensic exams they have done. The same study also showed that industry leaders are 54 using detailed questionnaires and site visits by internal and third party auditors to verify service provider security. These findings provide evidence that merchants should be more careful as to which service providers to work with because the responsibility for using PCI compliant technologies rests solely on the merchant itself. Secondly, some merchants may be intimidated by the detailed and prescriptive standards and the psychological pressure of having to prove their compliance (Owen & Dixon, 2007). However, this can be overcome by a structured approach to PCI DSS compliance as it requires a high level of knowledge and experience to implement in sophisticated organizations. Likewise, many companies do not have a unified strategy for compliance that consists of a team of executives from across the company, including operations, legal, finance, IT, and empowering the group to make PCI compliance a holistic part of the organization (Lorden & Skorupa, 2008). Thirdly, for the majority of the merchants, two of the most difficult requirements of PCI DSS are protecting stored cardholder data (requirement three), and encrypting transmission of cardholder data across open, public networks (requirement four). VeriSign research found the following results regarding those two requirements of PCI DSS (Meadowcroft, 2008): 1. 79% of assessed companies failed to protect stored card holder data due to unencrypted spreadsheet data and unsecured physical assets within the company network; 2. 74% of assessed companies do not regularly test security systems and processes, which results in POS application vulnerabilities where cardholder data is copied and re-used by fraudsters; 3. Only 55% of merchants encrypt transmission of cardholder data and sensitive information across public networks. 55 However, keeping credit card information has some benefits for merchants. Many merchants use credit or debit card numbers to uniquely identify returning customers, especially in the case of online purchases. Because of the fact that credit cards contain detailed information on a customer, their shopping patterns can also be analyzed and transaction histories can be tracked. Some merchants also keep credit card information to pay refunds in case an item is returned. In such cases when merchants cannot just remove magnetic stripe and card verification data as soon as a payment is made, they have to get a firm understanding of the security of the stored cardholder data by asking four key questions: 1. Where the data is stored? 2. How is it used? 3. Where is it transferred to and from? 4. Is the data saved in an encrypted or unencrypted form? Additionally, merchants should fulfill all of the encryption requirements from VPN tunnels using IP security; email secured by SMIME and SSL certificates, to application, database and disk encryption. Merchants should take encryption seriously and have a structured encryption strategy to protect cardholder data as in the TJ Maxx case, where hackers had access to internal systems that processed and stored customer transaction data. This breach cost the company US$296.9 million which provides clear evidence of the importance of data encryption. Finally and most importantly, merchants believe that PCI DSS compliance guarantees a defense against hackers. However, this myth has been found to be untrue many times. The most recent and destructive data breach was against Hartland Payment Systems, a Princeton, N.J.-based company that provides payment processing 56 for roughly 200,000 U.S. businesses (Kircher, 2009). Forensic investigators found carefully hidden malware that was recording private cardholder data and was most likely sending it to a third party for fraudulent activities on Heartland’s servers. The dramatic part is that the company had been PCI compliant as of April 2008, which was before the breach took place. Likewise, the Hannaford grocery chain had a security breach of 4.2 million credit card records even though they were PCI compliant (PCI Knowledgebase, 2008). System changes can create security vulnerabilities and make the organization non-compliant instantly (Kidd, 2008). Because of that, organizations should understand that it is crucial to continuously monitor their systems for configuration changes in both physical and virtual environments (Configuresoft, 2008). According to Kidd (2008), compliance can be achieved through two simple steps. Initially, an organization should assess their compliance level with the elements of the PCI DSS. By doing so, current areas of potential risk will be defined and resources will be allocated more effectively. After addressing these issues and achieving a full compliance, the organization should continuously run system infrastructure monitoring with change auditing to make sure that compliance is sustained. Moreover, IT staff should be immediately alerted to any unauthorized changes, so that potential security weaknesses are pinpointed before a data compromise can occur. Briefly, merchants should focus on a strategy of pervasive security and think of PCI DSS compliance as a starting point rather than a destination (Lorden & Skorupa, 2008). 57 Best Practices Identified above are major challenges to PCI compliance and it is hard for many companies to be fully compliant. According to a survey published in September 2007, only %11 of top UK retailers, financial services institutions and other businesses that accept card payments are fully compliant with PCI-DSS (Meadowcroft, 2008). However, that statistic also proves that full compliance is achievable. Below are the differentiators for PCI leaders. PCI leaders (Taylor, 2008): 1. 2. Use controls data to predict breaches; Have tools or services to monitor their environment on a continuous basis; 3. Share ownership of PCI and they take it as a collaborative process; 4. Share more budget on tracking individual actions; 5. Use risk management tools; 6. Protect other data, such as social security numbers and account numbers, besides card numbers; 7. Put more intention on monitor their service providers and partners for security and conformity of PCI DSS; 8. Use fewer compensating controls, which are the supplementary controls required for organizations that cannot or will not meet the requirements around the encryption of cardholder data (Owen, 2007), than typical enterprises; Compliance in Restaurants Restaurants are vulnerable to security attacks simply because about 80 percent of credit-card data breaches are tied to cash-registers and other POS terminals majority of which are found in restaurants (Clark, 2007). Again, it is estimated that 58 losses which are caused by credit card skimming has become a worldwide problem, and 70% of skimming occurs at restaurants (“The Skinny on Skimming,” 2007). As a consequence, companies that process card transactions are increasing the pressure on restaurants, threatening to cut off service, along with fines, to those who are not complying with their security rules (Sidel, 2007). The minimum fine for data loss is $500,000 for retailers who are dealing directly with the card companies (Gentry, 2007). On the other hand, fines start at $50,000 for non-compliance without data loss. Furthermore, if cardholder data is stolen in mass quantities, the retailer will be required to pay a reissue fee of as much as $200 per card. In the restaurant industry, there are various cases where credit card holder data were breached. One of the most recent data breaches took place in Dave & Buster’s corporate network (McMillan, 2008). Three criminals were charged with hacking into the network and then remotely installing software called packet sniffer on the point-of-sale servers of 11 Dave & Buster's locations throughout the U.S. The criminals used the packet sniffer to log credit- and payment-card data as it was sent in the plain text, unencrypted form from the branch locations to corporate headquarters. They hacked from April to September 2007, and the outcomes of the hacking were rewarding for the hackers according to court filings. For example, at Dave & Buster’s Islandia, New York location, the hackers managed to capture details of about 5,000 payment cards. Following, they sold the information to other criminals who then scammed online merchants using the card numbers. The approximate monetary loss which stems from the fraudulent transactions from 675 cards taken from this one store is US$ 600,000 . 59 For instance, the credit card processing system of Atlanta Bread Co. restaurant in Kansas city, was compromised by a hacker at a cost of over $25,000 (Stagemeyer, 2007). The restaurant was threatened with fines of up to $1 million and had $16,000 withdrawn from their bank account without notice. This prohibited them from buying inventory for a period of time and then they had to spend $7000 to upgrade their POS system. Another example is Chipotle Mexican Grill. Prior to August 2004, the company experienced nearly 2,000 incidents of customers’ credit card theft resulting in $1.4 million of fraudulent charges for which the restaurant chain became responsible. For this reason, they had to pay $4 million to cover the following: reimbursement of the fraudulent charges, the cost of replacing cards, monitoring expenses and fines imposed by Visa and MasterCard. Their 2005 annual report showed that the fines from Visa and MasterCard totaled $1.3 million. In summary, a large number of restaurants do not comply with PCI DSS and about 60% of the security breaches come from restaurant industry (Sidel, 2007). This assertion is supported by Visa International, which reports that 50% of incidents in which credit-card information is accessed illegally, occurred in restaurants. 60 Chapter 3 RESEARCH DESIGN The planning and development of the research study began in the fall of 2008 and continued through March 2009. During this time a review of literature was conducted and data collection procedures were determined. A survey instrument was formulated, and data analysis techniques were selected. In this chapter; the instrument, sampling plan and data analysis for this study will be explained in detail. Finally, limitations and assumptions for the study will be presented. Instrument A self-administered online questionnaire was created from the information obtained from the literature review. Additionally, a pilot study of this questionnaire was conducted among local restaurateurs to test the efficiency and clarity of the questionnaire. Revisions of the questionnaire were made based on the recommendations of the respondents in the pilot test. The first section of the survey consisted of characteristics of respondent and company includes organization distribution, job function distribution, total number of units, market coverage. The second section consisted of questions related to average annual revenue and business metrics of the company. The third section listed attributes related to IT characteristics. This section included questions asking respondents to provide their organization’s IT budget for 2008 (actual) and 2009 61 (projected), rate the innovativeness of IT from a business and technology perspective, identify where IT decisions were made, and to report if their organization had an IT steering committee. The fourth section of the instrument asked respondents questions about credit card acceptance and integration within their organization. The fifth section asked questions related to wireless access points and security protocols. The final section of the survey consisted of PCI DSS related questions. One question listed the 12 requirements of PCI DSS and asked the respondents to report if they were compliant with each of the requirements or not. For each of the requirements that they are not compliant with, they were asked to choose the barriers to compliance. In addition, the survey listed statements regarding the perceptions towards PCI DSS compliance. In this section a five-point Likert type scale response format (1= Strongly Disagree; 5 = Strongly Agree) was used. It was determined, based on prior research, that the five-point scale format reduces frustration and increases the quality of the responses (Shifflet, 1992). Lastly, a question related to the PCI DSS compliance management was asked. Sampling Plan The target population consisted of U.S. restaurant managers. An important and complex issue in sampling is to determine the appropriate sample size to be used. This determination largely depends on the statistical estimating precision needed by the researcher and the number of variables. The sample of 1000 American restaurants was drawn randomly from Hospitality Technology Magazine database. 62 Data Analysis Data was coded and analyzed with The Statistical Packages for Social Sciences 17. The first part of the data analysis involved characteristics of the respondents and their company including organization distribution, job function distribution, total number of units, market coverage. That data obtained from the questionnaires were tabulated using frequency tables. The second part of data analysis involved the average annual revenue and business metrics of the company. Similarly, that data obtained from the questionnaires were tabulated using frequency tables. The third part of data analysis involved IT characteristics of the organizations. Frequency tables are used to demonstrate that section. The fourth part of data analysis involved responses from the respondent’s organization credit card acceptance and integration, frequency tables were drawn with SPSS to show the data in tables. Similarly, for the fifth part of data analysis, frequency tables of wireless access points and security protocols of the organizations were shown. For the last section of the data analysis, PCI DSS related findings were obtained from questions that were tabulated using ANOVA, t-tests, frequencies, means, and standard deviations. 63 Limitations and Assumptions The first limitation is that the sample was drawn from Hospitality Technology Magazine subscribers. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized beyond that target population. Compliance levels were self-reported; therefore it was assumed that respondents would complete the questionnaire objectively and accurately. Finally, the sample size for this study was small. Therefore, it was harder to find significant relationships from the data, as statistical tests normally require a larger sample size to justify that the effect did not just happen by chance alone. 64 Chapter 4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The purpose of this study was to evaluate self-reported compliance of Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards version 1.2 in the restaurant industry. Thus, 8 research questions were constructed not only to provide restaurateurs a general idea on the PCI DSS compliance levels of the restaurant industry, but they also shed light on the attitudes and perceptions toward PCI DSS. These research questions were also used to identify organizational characteristics affecting PCI compliance. Moreover, findings also identifed the barriers to PCI DSS compliance in the restaurant industry for each of the PCI DSS requirements. In this chapter, respondent profile, organizational characteristics and IT characteristics of the organizations will be presented. Following, the 8 research questions regarding PCI compliance will be addressed. Respondent Profile One thousand surveys were distributed to the Hospitality Technology Magazine members. Survey had a total of 72 respondents; 2 of the responses were unusable. However, before the PCI DSS compliance questions, respondents were asked if they had credit card settlement in their organizations. If respondents selected “No” as the answer, the survey was terminated. Two of the respondents stated that their organization did not use credit cards, so they did not see the PCI DSS related 65 questions and were taken to the end of the survey. Because of the survey logic, not every respondent had to provide a response to all of the questions posed in the survey. Given that, 68 respondents filled in the survey completely, which yielded a net response rate of 6.8%. Whenever there is less than 100 % participation in a survey, there is a question of non-response bias that is the likelihood of data being changed if all members of the population would have responded to the survey. A non-response analysis using wave analysis (early versus later respondents) was conducted to determine (1) whether non-respondents and respondents differed significantly, (2) whether equivalent data from those who did not respond would significantly altered findings. Rylander, Propst, and McMurtry (1995) suggested that late respondents and non-respondents were alike and wave analysis and respondent/non-respondent comparisons yielded similar results. The survey was open for 15 days. All the responses received on or before the 7th day of the survey were coded as “early respondents.” Similarly, all responses received after the 7th day were coded as “late respondents”. Then, an independent t-test was conducted on the means of PCI perceptions to see if early respondents’ responses were different from late respondents’. The analysis indicated that there were no significant difference, concluding that this survey did not suffer non-response bias and therefore was representative of the population of Hospitality Technology subscribers who are in charge of information technology in restaurants. Respondent And Company Characteristics The respondent and company characteristics are shown in table 4.1. Respondents’ job functions varied however, the majority of the respondents’ job 66 functions are related to information systems and technology (47.1%), followed by owner/operators (17.1%) and corporate management (14.3%). Financial management accounted for 10% and other job functions such as operations/property management, food/beverage management and general manager account for 11.4%. As to organizational distribution, 78.6% of the organizations were multiunit restaurant chains (n=55), while 15.7% were single-unit restaurants (n=11). About 5% of the respondents chose “other” for this question. Market coverage of the franchisors (n=55) are: 18.6% for the organizations operated at global level, 21.4% for the organizations operated at national level, 24.3% for the organizations operated at regional level, and 10% for the organizations operated at local level. Among those multi-unit restaurants (n=55), 63.6% percent were franchisors, while 37.4% were franchisees. And among those franchisors, the percentages of their franchise proportion are: 42.9% for 0% to 25%, 14.3% for 26% to 50%, 14.3% for 51% to 75%, and 28.6% for 76% to 100%. When looking at the responses by restaurant segment, the following was found. In quick service restaurants, 20% have less than 10 units, 11.4% have 101 to 1000 units, 8.6% have 11 to 1000 units, and 10% have more than 1000 units. In casual family restaurants, 21.4% have less than 10 units, 21.4% have 11 to 100 units, 8.6% have 11 to 1000 units, and 5.7% have more than 1000 units. In respondents that operate fine dining restaurants, 11.4% have less than 10 units, 7.1% have 11 to 100 units, and 1.4% has 101 to 1000 units. To generalize, 41.4% of the restaurants are quick service, 41.4% are casual/family and 17.1% are fine dining restaurants. 67 Table 4.1 Respondent and Company Characteristics Job function distribution Organization distribution Type n % Sub-Type n % Multi-Unit Restaurant chain 55 78.6 Franchisor 35 63.6 Franchisee Single-Unit restaurant Other Total 11 15.7 4 70 5.7 100.0 QSR n % 20 Franchise % 0 to 25% 26% to 50% 51% to 75% 75% to 100% n % Job Type n % 15 5 42.9 14.3 Owner/Operator Corporate Management 12 10 17.1 14.3 5 14.3 33 47.1 10 28.6 Information systems/Technology Management Financial Management 7 10.0 Other 8 11.4 Total 70 100.0 36.4 Total Number of Units Casual Family Fine Dining n % n % Market Coverage of multi-unit restaurant chains Other n % n % 13 23.6 15 17 27.3 30.9 Less than 10 units 14 20.0 15 21.4 8 11.4 5 7.1 11-100 units 101-1000 units More than 1000 units None Total 6 8 8.6 11.4 15 9 21.4 12.9 5 1 7.1 1.4 1 3 1.4 4.3 Operated at global level (USA and international) Operated at national level (USA) Operated at regional level (USA) 7 10.0 4 5.7 0 0.0 0 0.0 Operated at local level (city or state) 10 18.2 35 70 50.0 100.0 27 70 38.6 100.0 56 70 80.0 100.0 61 70 87.1 100.0 Total 55 100.0 68 Company Average Annual Revenue and Business Metrics According to the data acquired from the respondents (Table 4.2), 38.6% of the organizations’ approximate annual revenue was less than $50 million, followed by $100 to $499 million (20%), $500 million to $1 billion (14.3%), $50 to $99 million (12.9%), and more than 1 billion (11.4%). Considering the current economic conditions, it is not surprising to see that 47.1% of the respondents reported that there is a negative change in their gross revenues, guest counts, same store sales and net profitability over last year. Conversely, the only business metric that changed positively was average guest check with 38.6% reported, which is slightly more than those responding a negative change (31.4%). IT Characteristics According to table 4.3, majority of the respondents (28.6%) reported that their organization’s IT budget in 2008 was below 1% of sales for that year. Also for the year 2009, 26.8% of the respondents reported that their organization’s IT budget was below 1% of sales for that year. However, regardless of the year, a majority of organizations’ IT budget is equal to or less than 2% of sales. Table 4.3 also projects the means and frequencies of the organizations’ innovativeness levels from a business and a technology perspective. A five-point Likert-type scale response format (1=Laggard, 5=Innovator) was deployed. Respondents reported that their organizations consider themselves innovators from a business perspective (M=3.84) more than a technology perspective (M=3.39). Majority 69 of the organizations have an IT steering committee (62.9%) and decisions are made predominantly at the corporate level (85.7%) rather than unit level (14.3%). 70 Table 4.2 Company Average Annual Revenue and Business Metrics Approximate annual revenue of the organizations (last year) More than $1 billion $500 million - $1 billion $100 - $499 million $50 - $99 million Less than $50 million I prefer not to answer Total n 8 10 14 9 27 2 70 % 11.4 14.3 20.0 12.9 38.6 2.9 100.0 Organizations’ direction of change in the business metrics for this year (forecasted - 2008 to 2009) compared to last year (actual - 2007 to 2008)? Gross Average guest Guest counts Same store Net revenue check (guest sales growth profitability (company(per customer) volume) (per location) (companywide) wide) n % n % n % n % n % Positive 26 37.1 27 38.6 18 25.7 23 32.9 22 31.4 None 11 15.7 21 30.0 11 15.7 14 20.0 20 28.6 Negative 33 47.1 22 31.4 41 58.6 33 47.1 28 40.0 Total 70 100.0 70 100.0 70 100.0 70 100.0 70 100.0 71 Table 4.3 IT Characteristics Organizations’ innovativeness from business and technology perspective Organizations’ IT budget percentage in 2008 (actual) and 2009 (projected) 2008 <1 1% 2% 3% 4% 5% 8% I don’t know Total n 20 12 13 2 2 3 2 16 70 % 28.6 17.1 18.6 2.9 2.9 4.3 2.9 22.9 100.0 2009 n 19 18 8 3 3 0 3 16 70 Business Perspective n % 1-Innovator 20 28.6 2 22 31.4 3 25 35.7 4 3 4.3 5-Laggard 0 0.0 Total 70 100.0 Mean 3.84 SD* .89 1=Laggard; 5=Innovator % 26.8 25.4 12.7 4.2 4.2 0.0 4.3 22.9 100.0 IT decisions are made predominantly at the: n % Corporate level 60 85.7 Unit level 10 14.3 Total 70 100.0 *SD = Standard Deviation Technology Perspective n % 13 18.6 18 25.7 26 37.1 9 12.9 4 5.7 70 100.0 3.39 1.11 Does your organization have an IT steering committee? n % Yes 26 37.1 No 44 62.9 Total 70 100.0 72 Credit Card Acceptance And Integration Table 4.4 provides the evidence that credit cards are widely used in the restaurant industry. Just over 97% of the organizations accept credit cards as a payment method, which is in line with the statistics provided in the literature review. Only 2 of the respondents reported that their organization does not accept credit cards at the present time. One responded that credit card transactions were too expensive, while the other responded that the details to accept credit cards have not been worked out however, both organizations were planning to implement credit card processing within the next 6 months. According to the data, 86.8% of the credit card systems are integrated with the POS systems. As presented in the literature review, restaurants are vulnerable to security attacks as nearly 80 percent of credit-card data breaches are tied to cashregisters and POS terminals (Clark, 2007). Table 4.4 Credit Card Acceptance and Integration Credit card acceptance n % Yes 68 97.1 No 2 2.9 Total 70 100.0 Credit card integration with the POS system n % Yes, it is integrated 59 86.8 No, it is independent of my POS 9 13.2 Total 69 100.0 Use of Wireless Access Points and Security Protocols Table 4.5 manifests that 48.5% of the organizations in this survey do not provide wireless access points for their customers or staff. From a security perspective, this may be useful as wireless networks are more susceptible to security attacks 73 (Collins & Cobanoglu, 2008). Among the organizations that provide wireless access points, 77.1% have configured them with security protocols. Conversely, only 20% percent of the wireless access points have not been configured with security protocols. Table 4.5 Use of Wireless Access Points and Security Protocols Do you provide Wireless Access Points for your customers or staff? For customers For staff n 12 5 % 17.6 7.4 For customers and staff 18 No Total 33 68 Are the wireless access points configured with security protocols? Yes No n 27 7 % 77.1 20.0 26.5 I do not know 1 2.9 48.5 100.0 Total 35 100.0 PCI DSS Compliance Levels Research Question #1 stated: “To what extent are U.S. restaurants compliant with PCI DSS requirements?” To address this research question, respondents were asked to state if they are compliant with each of the 12 requirements of the PCI DSS (N=68). Table 4.6 shows that 91.2% of the respondents believed their company was in compliance with the first requirement. When asking respondents to report their organization’s compliance of the PCI DSS requirements individually, for each requirement at least 67.6% of the respondents reported that their company was compliant with the requirement. With respect to ranking the level of compliance with each requirement; 3, 4, 5, and 7, took the lead respectively. 74 Table 4.6 PCI DSS Compliance Levels Please indicate if your organization is in compliance with the following requirements of PCI Data Security Standards. Please use "Yes" only if your organization is in FULL compliance with the requirement. n (Yes) % (Yes) 1- Install and maintain a firewall configuration to protect cardholder data 62 91.2 2- Do not use vendor-supplied defaults for system passwords and other security parameters 3- Protect stored cardholder data 60 88.2 66 97.1 4- Encrypt transmission of cardholder data across open, public networks 65 95.6 5- Use and regularly update anti-virus software 65 95.6 6- Develop and maintain secure systems and applications 62 91.2 7- Restrict access to cardholder data by business need-to-know 63 92.6 8- Assign a unique ID to each person with computer access 46 67.6 9- Restrict physical access to cardholder data 58 85.3 10- Track and monitor all access to network resources and cardholder data 48 70.6 11- Regularly test security systems and processes 48 70.6 12- Maintain a policy that addresses information security 51 75.0 N = 68. In further analysis, the sum of “yes” responses for each PCI DSS requirement compliance question was calculated to arrive at a PCI DSS compliance score. Table 4.7 shows that 45.6% of the respondents reported that their organizations are in full compliance, meaning that they are compliant with all 12 of the PCI DSS requirements. This means that 54.4% of the respondents’ organizations are not compliant with PCI DSS. Study also found that 72.1 % of the respondents are in compliance with at least 10 of the requirements, and 22.1% of them are in compliance from 7 to 9 requirements. However, as PCI compliance is either black or white, 45.6% for full compliance is not sufficient as it has been almost 3 years since the first version of the requirements came out. 75 Table 4.7 PCI DSS Total Compliance Levels Research Question #2 stated: Is the level of PCI compliance different based on organizational characteristics? To address this question, for each respondent, the number of “yes” (which is recoded as an integer value of 1) responses for the PCI DSS requirement compliance questions were summed up and put into a new variable called “Total PCI DSS Compliance Score”, being a maximum score of 12. And then, additional tests (independent t-test or ANOVA) were performed to determine if the total PCI compliance scores were significantly different across organizational characteristics. There were no significance in the total PCI Compliance scores across organizational type (Multi-unit versus single-unit), restaurant types (QSR, Casual/Family, and Fine- 76 Dining Restaurants), franchising type (Franchisor versus Franchisee), total number of units, market coverage, approximate annual revenue, gross revenue (company-wide), average guest check (per customer), guest counts (guest volume), net profitability (company-wide), the organizations’ innovativeness from a business perspective, organizations’ IT budget percentage, IT governance, and IT steering committee. The two organizational characteristics that were found to be significant were the organizations’ innovativeness from a technology perspective and how PCI DSS management was handled. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the effect of the level of organizations’ innovativeness from a technology perspective on total PCI compliance scores. Rogers (1995) proposes that adopters of any new innovation or idea can be categorized as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards. Thus, those groups were used in the questionnaire for categorization. The assumptions under which ANOVA is reliable are: (1) Independence: observations should be independent and the dependant variable should be measured on at least an interval scale, (2) Normality: data should be from a normally distributed population, (3) Equal variance: the variances in each experimental condition are fairly similar (Field, 2005). Since the sample was chosen by using simple random sampling method, the first assumption was met. To address the second assumption of the ANOVA, normality tests such as Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) and Shapiro-Wilk (SW) tests were applied. The results of these tests were tabulated in table 4.8. For the early majority, early adopters and innovators groups; both of the tests found significance at the p<0.5 level. However, a skewed distribution may actually be a desirable outcome on a criterion-referenced test (Brown, 1996, p. 138-142). Thus, box-plots, q-q plots 77 and histograms of the variables were visually inspected and outliers were identified. Taken together, it was decided that assumption of normality was met. To see if the equal variances assumption was met, the homogeneity of variance test was conducted and found that the variances (based on the mean) are homogeneous, Levene (4, 63) = 2.134, p = .087. It was found that there was a significant effect of the level of organizations’ innovativeness from a technology perspective on total PCI compliance score at the p<.05 level for the three conditions [F (4, 63) = 3.54, p = .011]. Post hoc comparisons (Table 4.9) using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the innovators group (M = 11.30, SD = 1.49) achieved significantly higher compliance scores than the late majority group (M = 8.22, SD = 3.73, p = .023). To put differently, innovators achieved better in terms of total PCI compliance score than early adopters. Table 4.8 Tests of normality for organizations’ innovativeness levels Innovativenes s Levels Total Compliance Kolmogorov-Smirnova Statistic df Laggards .250 4 Late Majority .261 9 Early Majority .246 Early Adopters Innovators Sig. Shapiro-Wilk Statistic df Sig. .961 4 .783 .079 .854 9 .083 25 .000* .828 25 .001* .287 17 .001* .648 17 .000* .448 13 .000* .515 13 .000* * = Significant at p≤.05 level; a = Lilliefors significance correction. 78 Table 4.9 Descriptives and Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis of total compliance by organizations’ innovativeness from a technology perspective Innovativeness levels n Mean Mdn *SD Skewness Kurtosis 1 – Laggards 4 8.00 8.50 3.74 -.76 1.50 2 – Late Majority 9 8.22 8.00 3.73 -1.32 2.39 3 – Early Majority 25 10.48 11.00 1.76 -1.01 .308 4 – Early Adopters 17 10.53 11.00 2.18 -2.78 9.39 5 – Innovators 13 11.30 12.00 1.49 -2.04 2.77 Total 68 Post Hoc 5>2 (p=.023)* * = Significant at p≤.05 level; *SD = Standard Deviation Survey participants were asked to report their approach to PCI compliance management with three options: (1) Completely in-house, (2) Completely outsourced, (3) Both in-house and outsourced. Since there were three groups in the independent variable, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. However, the homogeneity of variance assumption was violated, as Levene’s test results were statistically significant at the p≤.05 level. Thus, completely outsourced group was taken out of the analysis because of the small sample size of the group (n = 5). After that, an independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the effect of the compliance management type on total PCI compliance scores (Table 4.10). There was a significant difference in the scores for “completely in-house” group (M = 9.14, SD = 3.40) and “both in-house and outsourced” groups (M = 10.76, SD = 1.70); t (26.761) = -2.099, p = .045. These results suggest that organizations managing PCI compliance operations with both inhouse and outsourced staff have higher total PCI compliance scores than those that manage PCI compliance operations only in-house. 79 Table 4.10 T-test results of total compliance by compliance management n Mean 1-Completely in-house 22 9.14 Std. Deviation 3.40 2-Both in-house and outsourced 41 10.76 1.70 Total 63 9.95 2.55 Compliance Management t= -2.099; degrees of freedom=26.761; Sig.= .045. Research question #3 stated: What are the barriers to PCI compliance for restaurants? For each requirement that the respondents reported their organization was not compliant with, they were asked to choose the barriers to compliance from a list. The responses for each barrier was added up for each requirement and percentage of the sum total were calculated based on frequency. Table 4.10 manifests that limited budget is the leading barrier (n=59) to PCI DSS compliance. This was followed by the lack of qualified staff (n=47) and then lack of tools to manage the process (n=42). A small minority of respondents believed that lack of detail was a barrier to compliance of PCI DSS requirements. When looking at barriers for each requirement independently, the data shows that the barriers; limited budget, lack of tools to manage, and lack of qualified staff were reported consistently for most of the requirements. However, the lack of detail in the PCI DSS regulation does not appear to be an important barrier to the organization’s compliance. 80 Table 4.11 Barriers to PCI Compliance Please indicate if your organization is in compliance with the following requirements of PCI Data Security Standards. Please use "Yes" only if your organization is in FULL compliance with the requirement. 1. Install and maintain a firewall configuration to protect cardholder data 2. Do not use vendor-supplied defaults for system passwords and other security parameters 3. Protect stored cardholder data 4. Encrypt transmission of cardholder data across open, public networks 5. Use and regularly update anti-virus software 6. Develop and maintain secure systems and applications 7. Restrict access to cardholder data by business need-to-know 8. Assign a unique ID to each person with computer access 9. Restrict physical access to cardholder data 10. Track and monitor all access to network resources and cardholder data 11. Regularly test security systems and processes 12. Maintain a policy that addresses information security Total 81 Limited Budget Lack of tools to manage Lack of detail in regulation n % 0 0 n 3 % 5.08 n 3 % 7.14 3 5.08 3 5.08 0 2 4 1 5 4 9 5 9 8 6 59 3.39 6.78 1.69 8.47 6.78 15.25 8.47 15.25 13.56 10.17 100.0 1 1 3 2 3 11 4 3 6 2 42 3.39 6.78 1.69 8.47 6.78 15.25 8.47 15.25 13.56 10.17 100 0 0 0 2 0 1 2 5 4 6 20 Lack of qualified staff Other n 3 % 6.38 n 1 % 5 0 4 8.51 2 10 0 0 0 10 0 5 10 25 20 30 100 1 1 1 4 4 7 2 7 9 4 47 2.13 2.13 2.13 8.51 8.51 14.89 4.26 14.89 19.15 8.51 100 1 0 0 0 0 5 2 2 3 4 20 5 0 0 0 0 25 10 10 15 20 100 Research question #4 stated: How is the management of PCI DSS handled? Table 4.11 shows that 60.3% of organizations manage PCI DSS through both in-house and outsourced. It was reported that 32.4% of the organizations reported that the management of PCI compliance was handled completely in-house. It appears that only a small minority of restaurants completely outsourced the management of PCI compliance. Additionally, companies who do not completely outsource PCI DSS compliance operations were asked an open-ended question of how many IT personnel are assigned to monitoring compliance of PCI DSS. The mean of the responses were that 3.3 dedicated IT personnel were used for PCI DSS monitoring and compliance. Table 4.12 PCI DSS Management Type of Management n % Completely in-house 22 32.4 Completely outsourced 5 7.4 Both in-house and outsourced 41 60.3 Total 68 100.0 Research question #5 stated: What are the perceived costs of non-compliance of PCI DSS? To address this question, 5 sub-questions related to non-monetary costs of PCI DSS non-compliance were asked. Means of the non-monetary cost items to noncompliance were tabulated in table 4.13. A five-point Likert-type scale response 82 format (1=Strongly Disagree, 5=Strongly Agree) was deployed. Respondents think that the biggest cost of non-compliance is that organization’s reputation and brand damage would be negatively affected (M=4.06). This is followed by the negative impact on the organizations bottom line (M=3.83), negative effects on customer loyalty (M=3.43), decline in sales revenue (M=3.38) and the negative effect on the organization’s stock price (M=2.72). Table 4.13 Non-Monetary Costs of PCI Non-Compliance Mean Std. Deviation The organization's reputation/brand image will be negatively affected 4.06 0.92 It will have a negative impact on the organization’s bottom line 3.83 0.94 Customer loyalty will be significantly affected 3.43 0.99 The organization's sales revenue will decline 3.38 0.99 Stock price of the organization will be affected 2.72 1.50 n=69 *: 1=Strongly Disagree; 5=Strongly Agree Research question #6 stated: What are the attitudes and perceptions regarding the requirements of PCI DSS? To address this research question, a five-point Likert-type scale response format (1=Strongly Disagree, 5=Strongly Agree) was deployed and a series of attitude and perceptional questions related to PCI DSS were asked to the respondents. Four of those statements; “Compliance with PCI DSS is a good idea”, “Conforming with PCI DSS makes my job interesting”, “Working with PCI DSS is making us a better organization”, “I am happy that my company is focusing on PCI 83 compliance”, were developed based on the statements related to “Attitude toward using technology” section of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model (Venkatesh et al., 2003). A reliability analysis was conducted for the attitude statements. The Cronbach Alpha statistics for the attitude statements (n=4) was .795, well above the minimum value of 0.50 considered acceptable as an indication of reliability for applied research (Nunnally, 1967). As Table 4.14 shows, respondents tended to agree that PCI Compliance is a good idea (M=4.25), they are happy that their companies are focusing on PCI compliance (M=3.74), working with PCI compliance is making them a better organization (M=3.40) and conforming to PCI DSS makes their jobs interesting (M=3.04). Taken together, a total mean of 3.56 was achieved by the respondents. However, as PCI compliance is crucial for the organizations processing credit cards, the average attitude score was relatively low. Table 4.14 Attitudes toward PCI DSS Mean Std. Deviation Compliance with PCI DSS is a good idea 4.29 .93 I am happy that my company is focusing on PCI compliance 3.74 1.00 Working with PCI compliance is making us a better organization 3.40 1.12 Conforming to PCI DSS makes my job interesting 3.04 1.30 Total 3.56 1.09 n=68 *: 1=Strongly Disagree; 5=Strongly Agree 84 Table 4.15 presents 7 perception related statements along with their means and standard deviations. According to the table, respondents tended to agree that their organizations has made significant progress toward PCI compliance (M=4.16), and their POS systems are PCI compliant (M4.04). Those findings show that organizations are aware of the importance of PCI DSS and they are at least trying to be PCI compliant. On the other hand, they did not agree that they do not believe hackers will not be interested in their organizations (M=2.37), which is also a sign of their discretion. Table 4.15 Perceptions toward PCI DSS Mean Std. Deviation My organization has made significant progress toward PCI compliance. 4.16 1.00 Our POS system is PCI compliant. 4.04 1.39 I am aware of Version 1.2 of PCI DSS 3.84 1.40 I can list each and every network segment (including those between offices if you have a multi-site operation) that transfers credit card data in my organization 3.56 1.50 I believe that PCI compliance is the responsibility of technology vendors. 3.46 1.24 It is impossible to achieve 100% PCI compliance 3.40 1.31 I don’t believe hackers will be interested in my organization 2.39 1.18 Grand Mean 3.55 1.29 n=68 *: 1=Strongly Disagree; 5=Strongly Agree Research question #7 stated: Do organizational characteristics impact attitudes toward PCI DSS requirements? 85 To address this research question, additional tests (i.e. independent t-test or ANOVA) were performed to determine if attitudes toward PCI DSS were significantly different across organizational characteristics. Results of the analysis showed that there is no significance in attitudes toward PCI Compliance scores across organizational type (Multi-unit versus single-unit), restaurant types (QSR, Casual/Family, and Fine-Dining Restaurants), franchising type (Franchisor versus Franchisee), total number of units, market coverage, approximate annual revenue, organizations’ innovativeness from a business perspective, organizations’ innovativeness from a technology perspective, organizations’ IT budget percentage, IT governance, IT steering committee and type of PCI DSS management. This may be due to the fact that the study employed a small sample size. Research question #8 stated: Do organizational characteristics impact perceptions toward PCI DSS requirements? To address this research question, 5 statements in table 4.14 were selected and used for the analysis. Those are: “My organization has made significant progress toward PCI compliance“, “Our POS system is PCI compliant”, “It is impossible to achieve 100% PCI compliance”, “I can list each and every network segment (including those between offices if you have a multi-site operation) that transfers credit card data in my organization”, and “I am aware of Version 1.2 of PCI DSS”. A reliability analysis was conducted for these perception statements. The Cronbach Alpha statistics for the perception statements (n=5) was .261.Thus, each of the statements were compared with organizational characteristics independently; instead of computing a total perception score. Then, additional tests (i.e. independent t-test or ANOVA) were 86 performed to find out if perceptions toward PCI DSS were significantly different across organizational characteristics. Results of the analysis showed that there is no significance in perceptions toward PCI Compliance statements across restaurant types (QSR, Casual/Family, and Fine-Dining Restaurants), franchising type (Franchisor versus Franchisee), total number of units, market coverage, approximate annual revenue, organizations’ innovativeness from a business perspective, organizations’ innovativeness from a technology perspective, organizations’ IT budget percentage, IT steering committee and type of PCI DSS management. However, two of the organizational characteristics that were significant were organizational type (Multiunit versus single-unit) and IT governance. An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare individual perception scores in multi-unit restaurants and single-unit restaurants (Table 4.16). There was a significant difference in the “My organization has made significant progress toward PCI compliance” statement score for multi-unit restaurants (M = 4.33, SD = .85) and single-unit restaurants (M = 3.27, SD = 1.27); t (66) = 3.47, p = .001. There was also a significant difference in the “Our POS system is PCI compliant” statement score for multi-unit restaurants (M = 4.21, SD = 1.28) and single-unit restaurants (M = 3.18, SD = 1.66); t (66) = 2.32, p = .023.These results suggest that organizational type does have an effect on two of the perception statements. Specifically, results indicate that multi-unit restaurant managers believe more than single-unit restaurant managers that their companies have made more significant progress toward PCI compliance and that their POS system is more PCI compliant. 87 Table 4.16 T-tests between Perception Statements and Organizational Type Perception Statements My organization has made significant progress toward PCI compliance Our POS system is PCI compliant Organizational Type Multi-Unit restaurant chain Single-Unit restaurant Multi-Unit restaurant chain Single-Unit restaurant n Mean Std. Deviation 57 4.33 .85 11 3.27 1.27 57 4.21 1.28 11 3.18 1.66 t df Sig. 3.47 66 .001* 2.32 66 .023* * = Significant at p≤.05 level As shown in table 4.17, an independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare individual perception statement scores in organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the corporate level and organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the unit level. The alpha level was .05. There was a significant difference in the perception statements “I believe that PCI DSS compliance is the responsibility of technology vendors”, “Our POS system is PCI compliant”, “I can list each and every network segment (including those between offices if you have a multi-site operation) that transfers credit card data in my organization” for organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the corporate level and organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the unit level. These results suggest that IT governance type has an effect on three of the perception statements. Specifically, results indicate that managers of the organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the corporate level believe more than managers of the organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the unit level that PCI compliance is the responsibility of technology vendors, their POS system is PCI compliant and they can list each and every network segment (including those between 88 offices if you have a multi-site operation) that transfers credit card data in their organization. Table 4.17 T-test between Grand Perception Mean Scores and IT Governance Perception Statements I believe that PCI DSS compliance is the responsibility of technology vendors Our POS system is PCI compliant IT Governance n Mean SD* Corporate level 58 4.22 1.24 Unit level Corporate level Unit level 10 58 10 3.80 4.21 3.10 .70 1.29 1.59 58 3.72 1.48 I can list each and every network Corporate level segment (including those between offices if you have a multi-site operation) that transfers credit card Unit level data in my organization * = Significant at p≤.05 level; SD*=Standard Deviation 89 10 2.60 1.35 t df Sig. -2.73 66 .008 2.41 66 .019 2.24 66 .029 Chapter 5 CONCLUSIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS, AND FUTURE RESEARCH In this chapter, results of the study will be summarized and recommendations will be given based on the literature review and findings. Also, information as to how this study would be improved will be discussed in the future research section. Conclusions and Recommendations Results of the study showed that credit cards are widely used in the restaurant industry. About 97% of the organizations accept credit cards as a payment method, which is in line with the statistics shown in the literature review. Nearly 87% of the participating restaurant organizations’ credit card processing systems are integrated with the POS systems. As stated in the literature review, restaurants are vulnerable to security attacks simply because about 80 percent of credit-card data breaches are tied to cash-registers and other POS terminals, majority of which are found in restaurants (Clark, 2007). About 47% of the organizations do not provide wireless access points for their customers or staff. From a security perspective, this may be advantageous as wireless networks are more susceptible to security attacks (Collins & Cobanoglu, 2008, p. 86). Among the organizations which provide wireless access points, majority of them have configured them with security protocols. 90 Results of the study pointed out that most the requirements of the PCI DSS were achieved by the companies. Although many hospitality merchants find it difficult to be compliant with requirements 3 and 4 (Lorden, 2008), which are protecting stored cardholder data and encrypting transmission of cardholder data across open and public networks respectively, almost all of the organizations in this study reported that they are compliant with those requirements. Moreover, 45.6% of the respondents reported that they are in full compliance, meaning that they are compliant with all of the 12 PCI DSS requirements. One may assume that this is a good ratio considering the fact that PCI compliance is a difficult and time consuming process for the organizations. Besides; because of the nature of the requirements, keeping the PCI compliant state is harder than achieving PCI compliance itself for organizations. Results of the study showed that there are differences in total self-reported PCI compliance levels based on some of the organizational characteristics. High levels of organizations’ innovativeness from a technology perspective, and managing PCI compliance operations both in-house and outsourced have a significant positive effect on total compliance scores. The former finding makes perfect sense as PCI compliance requires a wide array of high-end technologies and network components to be put in place and that they work collaboratively. The latter finding also makes sense when the advantages of outsourcing compliance operations are considered. For some organizations, an outside vendor can provide external validation of the appropriateness of the processes and policies. This action provides reassurance to customers, partners, shareholders and card issuers. Most importantly, a third-party vendor can also provide an objective analysis of current compliance status and give recommendations for 91 closing any gaps (“Profiting from PCI Compliance,” 2007). Plus, when compliance validation is not outsourced, company officials become fully liable for any omissions or errors. Using a third-party vendor helps spread the risk carried by corporate management. However, the cost of outsourcing and those high-end technologies is high. So, one may assume that assigning in-house employees would help reduce the amount of money spent on outsourcing PCI compliance operations when possible. Findings of this study are also in line with that notion as limited budget was found to be the most common barrier to PCI compliance. As to one of the most important issues with PCI compliance; challenges and barriers, limited budget was the most reported barrier as mentioned above, followed by lack of qualified staff and lack of tools to manage PCI compliance. Those results are not surprising as organizations are having a hard time allocating resources for IT operations and qualified IT staff during the recession. Still, an open ended question asking how many IT personnel are assigned to monitoring and compliance of PCI DSS (this question is only asked to organizations who do not completely outsource PCI compliance operations) showed that organizations have 3.3 dedicated IT personnel for PCI DSS monitoring and compliance on average. Other than that, minority of the respondents thought that PCI DSS regulations are not detailed enough. However, for the last requirement (Maintain a policy that addresses information security), lack of details was reported as the biggest barrier for compliance. If sub-requirements of that requirement are further analyzed, it can be clearly seen that some organizations may approach some of the subrequirements in a different way than others. For example, requirement 12.6 entails implementing a formal security awareness program to make all employees aware of 92 the cardholder security. In one of its sub-requirements, which is verifying that the security awareness program provides multiple methods of communication awareness and educating employees (for example, posters, letters, memos, web-based training, meetings, and promotions); organizations are required to create training materials. However, there are no guides or templates provided by PCI security standards council, which may result in confusion as how to approach to this requirement. Taken together, PCI SSC should do due diligence in terms of clarity and magnitude of the standards for forthcoming versions of PCI DSS. Results of the study suggest that limited budget is the most frequently reported barrier for requirements 8 (Assign a unique ID to each person with computer access), 10 (Track and monitor all access to network resources and cardholder data), 11 (Regularly test security systems and processes). Because of the nature of these requirements, they require more continuous attention than the others. For requirement 8, there are lots of sub-requirements that entail on-going examinations, inspections and interviews. As to requirements 10 and 11, they can be assumed as the most important requirements because tracking, monitoring and testing the systems for security vulnerabilities are the only way to retain a compliant state for a particular organization. More to the point, as monitoring functions are effective in pinpointing problems that hamper the speed, efficiency and reliability of systems; it would be wise for organizations to take care of requirements 10 and 11 earlier in their PCI compliance processes. Since those requirements are also on-going, it is recommended for organizations that more work hours should be allocated for those requirements. That means more money or qualified staff is needed. Thus, it is not surprising as presented by the findings of this study that those three requirements alone constituted as much as 93 50% of the total responses for the lack of qualified staff barrier. Additionally, respondents reported that lack of tools to manage is the leading barrier for requirement 8. This finding also makes sense as expensive technologies such as remote authentication and dial-in service (RADIUS), terminal access controller access control system (TACACS) with tokens, wireless private networks (VPN) with individual certificates, token devices, smart cards and biometrics are required to be compliant with requirement 8. Thus, organizations should allocate more budget for better achievement on requirement 8. Findings also shed light to the perceived non-monetary cost of PCI noncompliance. Respondents reported that the biggest cost of non-compliance is that organization’s reputation and brand would be negatively affected. This is followed by the negative impact on the organizations’ bottom line, customer loyalty, sales revenue and organizations’ stock price. However, findings of the study showed that majority of the organizations’ IT budget is equal to or less than 2% of sales for the years 2008 (actual) and 2009 (projected). That means the budget spent on PCI compliance is even less. If not being compliant causes those non-monetary losses, along with the monetary losses as stated in the literature review, organizations should consider the aftermaths of non-compliance and increase their IT budgets. Results of the study also confirmed that there are differences in respondent perceptions toward PCI DSS based on some of the organizational characteristics. Results indicate that multi-unit restaurant managers believe more than single-unit restaurant managers that their companies have made more significant progress toward PCI compliance and that their POS system is more PCI compliant. This may be due to the fact that multi-unit restaurants have a more structured approach for PCI 94 compliance operations. Considering that, it is not surprising to see in the results of this study that managers of the organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the corporate level believe more than managers of the organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the unit level that their POS system is PCI compliant and they can list each and every network segment (including those between offices if you have a multi-site operation) that transfers credit card data in their organization. Based on the fact that multi-unit restaurants have a more structured approach for PCI compliance operations, it was surprising to be found in this study that managers of the organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the corporate level believe more than managers of the organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the unit level that PCI compliance is the responsibility of technology vendors. However, as also stated in the literature review, the responsibility for using PCI compliant technologies rests solely on the organization itself. Thus, organizations should be more careful as to which service providers to work with. It is also recommended that organizations send out questionnaires or send auditors to review the security of the service providers. Respondents also agree that PCI Compliance is a good idea, their organizations made significant progress, and their POS systems are PCI compliant. Those findings show that organizations are aware of the importance of PCI DSS and they are at least trying to be PCI compliant. On the other hand, they agreed that hackers may be interested in their organizations, which is also a sign of their discretion. Besides, majority of the respondents think that it is impossible to achieve 100% PCI compliance. This maybe because of the fact that PCI DSS has quite a lot of 95 sub-requirements that need to be addressed in order to be compliant with the main 12 requirements. If it is even assumed that there will always be updates to these requirements or sub-requirements, it is expectable for some merchants to think that 100% PCI compliance is not possible. It would be suggested to large-scaled organizations that they have a unified strategy for compliance which consists of a team of executives from across the company; including operations, legal, finance, IT, and empowering the group to make PCI compliance a holistic part of the organization (Lorden & Skorupa, 2008). This type of structure would definitely help the organization share the ownership of PCI compliance; and in return, reduce the fear that 100% PCI compliance will never be achieved. As to small and mid-scaled organizations, it would be prudent to think about outsourcing because of the advantages declared above. Also, they could do research and find out ways of reducing the scope of PCI such as network segmentation and using third-party hardware and software. Table 5.1 tabulates the research questions and the summary of their results. 96 Table 5.1 Research Questions and Summary of the Results Research Questions 1. To what extent are U.S. restaurants compliant with PCI DSS requirements? 2. Is the level of PCI compliance different based on organizational characteristics? 3. What are the barriers to PCI compliance for restaurants? 4. How is PCI DSS management handled? 5. What are the perceived costs of noncompliance of PCI DSS? 6. What are the attitudes and perceptions regarding the requirements of PCI DSS? Summary of the Results Generally, organizations have difficulty in being compliant with requirements 8, 10, 11 and 12. The least percentage for compliance is about 68% (requirement 8). However, organizations have achieved higher compliance levels for the other requirements with at least 85.3% (requirement 9). Study found that 45.6% of the respondents reported that they are in full compliance, meaning that they are compliant with all of the 12 PCI DSS requirements. However, as PCI compliance is either black or white, 45.6% for full compliance is not sufficient as it has been almost 3 years since the first version of the requirements came out. High levels of organizations’ innovativeness from a technology perspective, and managing PCI compliance operations both in-house and outsourced have a positive effect on total compliance scores. Limited budget was found to be the leading barrier to PCI compliance. Besides, when looking at barriers for each requirement independently, the data shows that the barriers; limited budget, lack of tools to manage, and lack of qualified staff were reported consistently for most of the requirements. However, the lack of detail in the PCI DSS regulation does not appear to be an important barrier to the organization’s compliance. It was reported that 60.3% of organizations manage PCI DSS through both in-house and outsourced, while 32.4% of the organizations manage PCI compliance completely in-house. It appears that only a small minority of restaurants completely outsourced the management of PCI compliance (7.4%). Respondents think that the biggest cost of non-compliance is that organization’s reputation and brand damage would be negatively affected (M=4.06). This is followed by the negative impact on the organizations bottom line (M=3.83), negative effects on customer loyalty (M=3.43), decline in sales revenue (M=3.38) and the negative effect on the organization’s stock price (M=2.72). Respondents tended to agree that PCI Compliance is a good idea (M=4.25), they are happy that their companies are focusing on PCI compliance (M=3.74), working with PCI compliance is making them a better organization (M=3.40) and conforming to PCI DSS makes their jobs interesting (M=3.04). Taken together, a total mean of 3.56 was achieved by the respondents. However, as PCI compliance is crucial for the organizations processing credit cards, the average attitude score was relatively low. As to perception statements, respondents tended to agree that their organizations has made significant progress toward PCI compliance (M=4.16), and their POS systems are PCI compliant (M4.04). Those findings show that organizations are aware of the importance of PCI DSS and they are at least trying to be PCI compliant. 7. Do organizational characteristics impact attitudes toward PCI DSS requirements? No, attitudes toward PCI DSS were not significantly different across organizational characteristics. 8. Do organizational characteristics impact perceptions toward PCI DSS requirements? Yes, perceptions toward PCI DSS were significantly different across organizational type and IT governance. Results indicate that multi-unit restaurant managers have higher total perception scores than single-unit restaurant managers, and managers of the organizations that make their IT decisions predominantly at the corporate level have higher total perception scores than those that make their IT decisions predominantly at the unit level. 97 Future Research Future research may be conducted to duplicate this study in international markets. It would be interesting to compare these study findings with European restaurants in terms of PCI compliance as they are the leaders in the application of many new restaurant technologies such as pay at table systems, chip and pin cards, and other types of payment methods. This study may also be replicated for hotels to identify and compare the challenges to PCI compliance between hotels and restaurants. In this type of study, survey questions may have more focus on the challenges and barriers, and results would most probably be more significant if questions are structured according to several models. Research may be conducted addressing each of the specific PCI DSS requirements and focus on the requirement in detail. PCI DSS is an extensive set of requirements and it would be appropriate to deal with requirements individually along with the sub-requirements. This would give more detailed information about the specifics of PCI compliance. Finally, the sample size for this study was small. Therefore, it was harder to find significant relationships from the data, as statistical tests normally require a larger sample size to justify that the effect did not just happen by chance alone. So, it would be wise to replicate this study with larger sample sizes. 98 REFERENCES About the PCI Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). Retrieved December 19, 2008, from https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/security_standards/pci_dss.shtml About EMV. Retrieved April 02, 2009 from http://www.emvco.com/ ACH. (2000). In WhatIs.com online IT dictionary. Retrieved April 02, 2009 from http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/sDefinition/0,,sid14_gci214632,00.html AHLA PCI Compliance Process for Lodging Establishments (2008). American Hotel and Lodging Association. Albany Law Review. (2004). Identity Theft Statutes: Which will Protect Americans the most? (Issue Brief No. 4). New York: Catherine Pastrikos. American Bankers Association/Dove Consulting. (2005). Consumer Payment Preferences: Understanding Choice. Retrieved March 01, 2009, from http://www.aciworldwide.com/downloads/consumer_payment_preferences_tre nd.pdf Anderson, K. B. (2006) Who Are the Victims of ID Theft?: The Effect of Demographics, Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25(2)(2006), pp. 160– 171. 99 Asokan, N., Janson, P. A., Steiner, M., Waidner, M. (1997). The State of the Art in Electronic Payment Systems. IEEE JNL, 30(9), 28-35. Brooks, S. (2008, July). Tableside Ordering and Payment Answers. Hospitality Technology Magazine. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.htmagazine.com/ME2/dirmod.asp?sid=&nm=&type=MultiPublishi ng&mod=PublishingTitles&mid=3E19674330734FF1BBDA3D67B50C82F1 &tier=4&id=8E6293BF24B2469598808476435B3422 Brown, J. D. (1996). Testing in language programs. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Collins, G. R., & Cobanoglu, C. (2008). Hospitality Information Technology: Learning How to Use It (6th ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt. Compliance Validation Details for Merchants. Retrieved March 15, 2009, from: http://www.usa.visa.com/merchants/risk_management/cisp_merchants.html?it =c|/merchants/risk_management/cisp.html|Defining%20Your%20Merchant%2 0Level#anchor_2 Configuresoft. (2008). Moving Beyond the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard Checklist Approach: Achieving Continuous Compliance [White Paper]. Retrieved March 18, 2009, from http://securitypark.bitpipe.com/detail/RES/1210960403_58.html Coomes, S. (2007). Pay-at-the-table is iron-clad protection. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.selfserviceworld.com/article.php?id=17614 100 Cougias, D. (2008, April 18). Securing Payments: What the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard Means for your Resort. 8th Annual Resort Conference, San Diego, CA. Cronin, J. J., Jr., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. The Journal of Marketing, 56(3), 55-68. Epstein, R. A., & Brown, T. P., "The War on Plastic". Regulation, 29(3), pp. 12-16, Fall 2006 Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=944870 Eisenstein, E.M. (2008). Identity theft: An exploratory study with implications for marketers. Journal of Business Research, 61(11), 1160-1172. Experian National Score Index (2007). Score News Feature. Retrieved December 19, 2008, from http://www.nationalscoreindex.com/ScoreNews_Archive_13.aspx Federal Trade Commission (2008). FTC Releases List of Top Consumer Fraud Complaints in 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2008, from http://www.ftc.gov/opa/2008/02/fraud.shtm Field, A. P. (2005). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (2nd Edition). London: SAGE Publications. First Data. (2008). [Graph illustration of the most frequently used payment method by retail location]. Consumer Payment Preferences for In-Store Purchases. Retrieved from http://www.firstdata.com/enews/CPPBrief_InStore.pdf 101 Gerdes, G. G. (2008). Recent Payment Trends in the United States, Federal Reserve Bulletin, 2008(Oct), pp. A75-A106. Gonzales A.R. & Majoras, D. P. (2007). Combating identity theft: a strategic plan, Office of the President (Ed.): U.S. Department of Justice. Newman, G. R. & McNally, M. M. (2005). ‘Identity Theft Literature Review.’ United States Department of Justice: National Institute of Justice. History of the PCI and PCI Compliance. Retrieved March 14, 2009, from http://www.pcicomplianceguide.org/pcicompliance-history.php Hoffman, D. L., Novak, T. P. (1999). Building ConTrust Online. Communications of the ACM, 42(4), 80-85. Horovitz, B. (2008). Hard Times are on the Menu at Restaurants. Retrieved March 16, 2008, from http://abcnews.go.com/Business/Economy/Story?id=4375720&page=1 How Card Processing Works? Retrieved March 16, 2009, from http://www.bankofamerica.com/small_business/merchant_card_processing/ind ex.cfm?template=card_processing_basics Kalkan, K., Kwansa, F., Cobanoglu, C. (2008). PCI Compliance in the U.S. Hospitality Industry. Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Hospitality and Tourism Management, Ocho Rios, Jamaica. 102 Kalogeris, R. (2005, Fall). Are you S.A.F.E.? Secure Against Fraud Electronically. Hospitality Upgrade, 160. Kasavana, M. (2006, Fall). Changing Actions in Point of Sale Transactions. Hospitality Upgrade, 145-148. Kelly, T. J., Carvell, S. (1987). Checking the Checks: A Survey of Guest-Check Accuracy. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 28(3), 63. Kircher, T. (2009). Restaurants Hit by Heartland Data Breach. Retrieved March 18, 2009, from http://www.fastcasual.com/article.php?id=13182 Kidd, R. (2008). Counting the cost of non-compliance with PCI DSS. Computer Fraud & Security, 2008(11), pp. 13-14. Koroneos, G. (2008, May). New Payment Options. Hospitality Technology Magazine. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.htmagazine.com/ME2/dirmod.asp?sid=&nm=&type=MultiPublishi ng&mod=PublishingTitles&mid=3E19674330734FF1BBDA3D67B50C82F1 &tier=4&id=D1B4836DA32F43AC9DBDFF0E37FD2740 Laredo, V. G. (2008). PCI DSS compliance: A matter of strategy. Card Technology Today, 20(4), 9. Lorden, A., Skorupa, J. (2008, September). PCI: Roadmap to Real-World Security. Hospitality Technology Magazine. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.htmagazine.com/ME2/dirmod.asp?sid=8D86DF469BD74C098382 D9532C904D8E&nm=&type=MultiPublishing&mod=PublishingTitles&mid= 3E19674330734FF1BBDA3D67B50C82F1&tier=2&did=E91F9698D8C84F2 B993EBF8D000DE48A&dtxt=September+2008 103 Mastroberte, T. (2008, June). Payment Decadance: Pay-at-Table Tech Takes Hold. Hospitality Technology Magazine. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.htmagazine.com/ME2/dirmod.asp?sid=&nm=&type=MultiPublishi ng&mod=PublishingTitles&mid=3E19674330734FF1BBDA3D67B50C82F1 &tier=4&id=A86CC98DCC3742C6B61C66F5C55BCF1C McMillan, R. (2008). Three Charged in Dave & Buster's Hacking Job. PCWorld. Retrieved December 19, 2008, from http://www.pcworld.com/businesscenter/article/145781/three_charged_in_dave _amp_busters_hacking_job.html Meadowcroft, P. (2008). Card fraud – will PCI-DSS have the desired impact? Card Technology Today, 20(3), pp. 10-11. Morse, E. A., & Raval, V. (2008). PCI DSS: Payment card industry data security standards in context. Computer Law & Security Report, 24(6), pp. 540-554. Murphy, P. (2007, July). Tableside payment serves as a new tool in the fight against credit card skimming. Stores Magazine. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.stores.org/LPinformation_new/2007/07/LPiEdit1.asp Network Segmentation. (2009). In Wikipedia online encyclopedia. Retrieved April 10, 2009 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Network_segmentation Nunnally, Y.J.C. (1967). Psychometic Theory, McGraw Hill: New York. Owen, M., & Dixon, C. (2007). A new baseline for cardholder security. Network Security, 2007(6), pp. 8-12. 104 Owen, M. (2007). The PCI DSS Appendix B: Compensating Controls [White Paper]. Retrieved April 10, 2009, from http://www.irmplc.com/downloads/whitepapers/PCI_DSS_Whitepaper.pdf Pay-at-the-Table. Retrieved March 10, 2009, from http://www.tabletopmedia.com/solution.html Payment-at-table – enabling the wireless revolution. (2004). Card Technology Today, 16(10), 11-12. Payment Card Industry -PCI- Compliance. Retrieved March 14, 2009, from http://www.solidcactus.com/pci.html PCI Compliance: Low Risk, High Reward. (September, 2007). Retrieved November 26, 2007, from Hughes Networks Systems Web site: http://www.hughes.com/HUGHES/Doc/0/BIJENRGP3AT4JFJSEAUGLUJ7C 1/PCI%20Compliance.H36659.09-24-07.pdf Taylor, D. (2008). The PCI Leadership Report. Retrieved March 16, 2009, from http://www.pciknowledgebase.com/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat _view&gid=26&Itemid=151 PCI Security Standards Council. (2008). About the PCI Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). Retrieved December 19, 2008, from https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/security_standards/pci_dss.shtml 105 PCI Security Standards Council. (2008, October 1). PCI SECURITY STANDARDS COUNCIL RELEASES VERSION 1.2 OF PCI DATA SECURITY STANDARD [Press release]. Retrieved March 14, 2008, from https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/pdfs/pr_080930_PCIDSSv1-2.pdf PCI Security Standards Council. (2008). Payment Card Industry (PCI) Data Security Standard: Requirements and Security Assessment Procedures, version 1.2. [White paper]. Retrieved March 15, 2009, from https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/security_standards/pci_dss_download.ht ml Pemble, M. (2008). Don’t panic: taxonomy for identity theft. Computer Fraud & Security, 2008(7), pp. 7-9. Perry R., & Witly, M. J. (2006). Total Cost of Ownership for Point-of-Sale and PC Cash Drawer Solutions: A Comparative Analysis of Retail Checkout Environments. Framingham, MA: IDC. Retrieved February 18, 2009, from ftp://ftp.software.ibm.com/software/retail/marketing/whitepaper/pos_vs_pccd_ 1106.pdf PIN Entry Devices. Retrieved March 10, 2009, from https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/security_standards/ped/index.shtml Privacy Rights Clearinghouse (2007). How Many Identity Theft Victims Are There? What Is the Impact on Victims? Retrieved October 23, 2007, from http://www.privacyrights.org/ar/idtheftsurveys.htm Profiting from PCI Compliance. (September, 2007). Retrieved November 26, 2007, from IBM Corporation Web site: www935.ibm.com/services/us/iss/pdf/profiting_from_pci_compliance_wp.pdf 106 ResourceNation. (n.d.). Benefits of Using a POS System. Buyer Guide on the Benefits of Using a POS System. Retrieved February 23, 2009, from ResourceNation Web site: http://www.resourcenation.com/buyers-guides/benefits-using-possystem Richardson, N. (2008, December). Payment Processing Update. Technology Magazine. Retrieved March 10, 2009, from http://www.htmagazine.com/ME2/dirmod.asp?sid=&nm=&type=MultiPublishi ng&mod=PublishingTitles&mid=3E19674330734FF1BBDA3D67B50C82F1 &tier=4&id=E71FE3DDAA634AEF816E309554457F86 Rogers, E. M. 1995. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press. Rowlingson, R., & Winsborrow, R. (2006). A comparison of the payment card industry data security standard with ISO17799. Computer Fraud & Security, 2006(3), 16-19. Rysman, M. (2007). An Emprical Analysis of Payment Card Usage. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 55(1), 4, 13. Sacco, J. (n.d.). Restaurant POS Systems. Retrieved February 18, 2009, from http://www.assuredcomptech.com/WHITE%20PAPERS/Restaurant%20POS% 20Systems.pdf. Sill, B. (1994). Operations engineering: Improving multiunit operations. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 35(3), pp. 64-71. Skimming. (2009). In Wikipedia online encyclopedia. Retrieved April 02, 2009 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skimming_(credit_card_fraud)#Skimming 107 The Payment Cards Center of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia and the Electronic Commerce Payments Council of the Electronic Funds Transfer Association. (2003). AFTER THE HYPE e-COMMERCE PAYMENTS GROW UP. Retrieved March 01, 2009, from http://www.philadelphiafed.org/payment-cardscenter/events/conferences/2003/eCommerce_062003.pdf The Skinny on Skimming. (2007, July). Stores Magazine. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.stores.org/LPinformation_new/2007/07/LPiEditSide1.asp. United Nations. (2008, January). World Economic Situation and Prospects 2008; Update as of mid-2008. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.un.org/esa/policy/wess/wesp2008files/wesp08update.pdf Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425478. Verifone. (2007). A Better Way to Pay in Restaurants [White Paper]. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.verifone.com/aboutus/whitepapers/VFI_Hospitality_WP_Apr_07.pdf Visa (2008, February 27). Security Best Practices for Level 4 Merchants and Franchise Operators: Payment System Security Compliance. Retrieved December 19, 2008, from http://usa.visa.com/download/merchants/20080227l4-franchises-best-practices.pdf. Visa Internal Statistics Q4 2006.Useful Facts. Retrieved December 19, 2008, from http://usa.visa.com/merchants/new_acceptance/benefits/index.html 108 Visa U.S.A. Inc. (2006). 2006 Payment Trends Summary. Retrieved March 16, 2009, from http://www.bos.frb.org/economic/eprg/conferences/payments2006/papers/ham pton.pdf Young, F. (2009). Is PCI Compliance a Law? Should it be? Retrieved March 06, 2009, from http://www.pcicomplianceguide.org/security-tips-20090227-pcicompliance-law.php Why make a meal of customer payments? (2005). Card Technology Today, 17(9), 1416. Wright, S. (2008). PCI DSS: A practical guide to implementation. Available from http://books.google.com/books?id=Gz4eEJHv3j0C 109