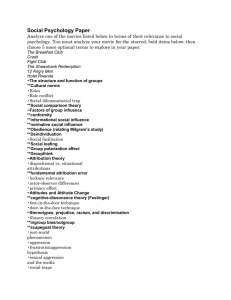

Personality and Individual Differences 48 (2010) 288–293 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Personality and Individual Differences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/paid Mean on the screen: Psychopathy, relationship aggression, and aggression in the media Sarah M. Coyne a,*, David A. Nelson a, Nicola Graham-Kevan b, Emily Keister a, David M. Grant a a b Brigham Young University, School of Family Life, Provo, UT 84602, USA University of Central Lancashire, Department of Psychology, Preston, UK PR1 2HE, UK a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 7 May 2009 Received in revised form 2 October 2009 Accepted 8 October 2009 Available online 8 November 2009 Keywords: Psychopathy Media Aggression Relational aggression Television Domestic violence a b s t r a c t The aim of the current study was to examine the association between psychopathic features and various forms of relationship aggression in a non-clinical population. Additionally, exposure to media aggression was examined as a potential mediator of the relationship between psychopathy and aggression. Participants consisted of a total of 337 individuals who either reported on their current or most recent relationship. Results revealed that secondary psychopathy traits were related to both types of aggression measured in the current study (physical aggression and romantic relational aggression). Additionally, primary psychopathy traits were related to romantic relational aggression. Though exposure to media aggression (both physical and relational forms) was related to perpetration of relationship aggression, such exposure did not mediate the relationship between psychopathy and aggression. Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Psychopathy has long been a focus of the public, media, and research community. Defined by features such as lacking conscience and feelings for others, psychopaths use charm, manipulation, and sometimes violence to get what they want (Hare, 1996). The literature suggests that psychopathy is multi-dimensional, with individual components (e.g. factor-1 and factor-2, Hare, 1991, or the four facets, Hare, 2003) demonstrating continuous rather than categorical qualities. It is therefore possible for a ‘psychopath’ to demonstrate few of the core psychological traits expected. This knowledge has led scholars such as Skeem, Poythress, Edens, Lilienfeld, and Cale (2003) to suggest that distinctions should be made on the basis of ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ psychopathy, the former demonstrating the core affective traits whereas the latter being more behaviorally derived. Karpman (1941) first proposed the primary–secondary psychopath distinction. Although both types manifested a disregard for the rights and feeling of others, as well as antisocial behavior, Karpman believed that primary psychopathy was the result of a congenital affective deficit whereas secondary psychopathy was the result of an adaptation to adverse early experiences. Primary psychopaths were believed to be motivated by reward (instrumen* Corresponding author. Address: 2087 JFSB, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA. Tel.: +1 801 422 6949. E-mail address: smcoyne@byu.edu (S.M. Coyne). 0191-8869/$ - see front matter Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.10.018 tal behavior), whereas secondary psychopaths were motivated by emotion (reactive behavior). Subsequent research has provided support for this distinction, finding that the traits of primary psychopathy may be the result of low levels of anxiety, whereas the features of secondary psychopathy may be the result of high levels of negative affect and impulsivity. There is broad research support for the existence of primary and secondary psychopathy traits (Falkenbach, Poythress, & Creevy, 2008; Ray, Poythress, Weir, & Rickelm, 2009; Wareham, Dembo, Poythress, Childs, & Schmeidler, 2009) (for a review see Poythress & Skeem, 2007). 1.1. Aggression A disproportionately large amount of violence and crime is thought to be perpetrated by individuals with psychopathic features (Hare, 1996). However, not all such individuals use violence to get what they desire. Indeed, many ‘‘successful” psychopaths function reasonably well in society, with many holding positions of power within academia, business, and other industries (e.g., Board & Fritzon, 2005; Lynam, Whiteside, & Jones, 1999). Although egocentric, callous, and manipulative (traits of primary psychopathy), these individuals usually lack the more overtly antisocial attributes found in secondary psychopathy, attributes that typically result in contact with the criminal justice system. According to the Warrior Hawk hypothesis (see Book & Quinsey, 2004), such individuals avoid violent behavior, particularly if they feel their S.M. Coyne et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 48 (2010) 288–293 behavior would be discovered. Instead, discretion and more manipulative types of behavior are likely to better suit their needs. Most research on the aggression and psychopathy relationship has focused on physical violence (e.g., Martinez et al., 2007). However, there is a growing body of research suggesting that individuals with psychopathic traits are also more likely to use relational aggression (e.g., Coyne & Thomas, 2008; Schmeelk, Sylvers, & Lilienfeld, 2008; Warren & Clarbour, 2009). Such aggression aims to harm relationships or the social structure as a whole (e.g., social exclusion, relationship manipulation, spreading rumors) and is linked to a variety of psychosocial problems for victims (e.g., Craig, 1998). Coyne and Thomas (2008) found that individuals with primary psychopathic traits were particularly likely to use relational aggression to manipulate those around them. However, they speculate that individuals with psychopathic traits may use aggression differently, depending on the target of the aggression. Some evolutionary theorists (Dawkins, 1976), indicate that aggression in close relationships may be particularly problematic, as the individual is not likely to remain anonymous, and the partner may eventually leave the relationship. However, various forms of partner aggression can be crafted to carefully manipulate and control one’s partner into a mindset of denial and need for the aggressor. For example, romantic relational aggression (Linder, Crick, & Collins, 2002) specifically focuses on manipulating the relationship to control one’s partner (e.g., threatening to leave the relationship should the individual not comply with the aggressor’s wishes). Such aggression in romantic relationships may be particularly common by individuals with psychopathic traits. Indeed, the relationship between psychopathy and abuse has been noted in several studies (e.g., Huss & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2006; Swogger, Walsh, & Kosson, 2007). However, the vast majority of this research focuses on physical forms of abuse in a clinical population and typically examines psychopathy as a unified construct as opposed to examining subtypes. Accordingly, one of the primary aims of this study is to examine the relationship between primary and secondary psychopathy traits and romantic relationship abuse, with a particular focus on romantic relational aggression in a non-clinical population. 1.2. Media One factor often examined when explaining aggressive behavior is the media. Some studies have found that viewing violence in the media can increase aggressive thoughts and behavior, both in the short and long term (Anderson et al., 2003). Other research has also revealed that viewing relational forms of aggression in the media can also affect both physically and relationally aggressive behavior (e.g., Coyne et al., 2008). Accordingly, examining even subtle forms of aggression in the media is important when determining the effect of media exposure on subsequent behavior. However, research examining the link between media violence and subsequent aggression has come under recent criticism. Browne and Hamilton-Giachritsis (2005) argue that though there is clear evidence for a short term effect of viewing media violence, the long-term effects on aggressive behavior and crime are weak or inconsistent. Additionally, after correcting for publication bias, a recent meta-analysis (Ferguson & Kilburn, 2009) found only a very small overall effect size (r = .08) when examining this relationship. Indeed, according to the uses and gratifications approach (Katz, Blumler, & Gurevitch, 1974), the viewer seeks out violent media to fulfill certain needs, such as having an aggressive personality. According to this theory, personality may drive any relationship between media and violence. Additionally, the General Aggression Model (GAM; Anderson & Bushman, 2002) notes that personality may influence the media 289 violence effect in two other important ways. First, long-term exposure to media violence can shape an individual’s personality, particularly those facets of personality related to aggressive behavior (Huesmann, 1986). Second, certain personality characteristics seem to mediate the effect of viewing media violence on subsequent aggressive behavior in the short term. For example, when Zilmann and Weaver (1997) exposed adults to gratuitous media violence, only males high in psychoticism showed increased acceptance of aggressive conflict resolution. On the other hand, Ferguson, Cruz, Martinez, Rueda, Ferguson, and Negy (2008) found that although personality was related to engagement in crime, exposure to media violence was not. To our knowledge, it is unknown whether psychopathic traits and media violence are related. Indeed, it is possible that individuals with such traits may be particularly vulnerable to media effects. First, these individuals may be more prone to enactment of aggression, with a highly elaborate system of aggression-related scripts in memory. Secondly, individuals with primary psychopathic features are unlikely to empathize with victims of on-screen violence, one of the characteristics that often buffers the effect of media violence on aggression (see Donnerstein, Slaby, & Eron, 1994). Accordingly, exposure to media aggression may particularly enhance the likelihood for engagement in aggressive behavior for those with psychopathic traits. 1.3. Aims and hypotheses There are two main purposes to this study. Firstly, we aim to assess the relationship between psychopathy traits and relationship aggression in a non-clinical population. It is expected that all forms of aggression will be associated with both types of psychopathy traits. However, since primary psychopathy is characterized by an aptitude for manipulating people and relationships for their own advantage (Hare, 1996), it is expected that the use of romantic relational aggression would be particularly associated with primary psychopathy traits. The other primary aim of the study is to test whether viewing media aggression mediates the relationship between psychopathy and aggression. Based on the uses and gratifications approach, we predicted that psychopathy would be related to both types of media aggression, and this would partially mediate the relationship between psychopathy and relationship aggression. 2. Method 2.1. Participants and procedure The study consisted of 337 participants (55% female) recruited from undergraduate courses at a university. Participant age ranged from 18–27 (M = 20.93, SD = 2.31) and the majority described themselves as Caucasian (88%). Furthermore, all participants reported being heterosexual. Relationship status was fairly mixed, with 23% of participants being married, 44% reporting they were dating someone at the present time, and 34% reporting they were currently single (though they had previously been in a relationship). Length of relationships ranged from one month to just over eight years (M = 1 year, 6 months; SD = 1 year, 1 month). The main requirement for participation was that participants had to have been involved in a serious relationship at some point in their adult life (since graduation from high school). Qualified participants were given the questionnaire packet and were asked to complete it by the next class period. A debriefing form was given upon completion of the questionnaires. Participants received course credit for their participation. Completion rates across classrooms ranged from 65 to 90% (overall completion rate of 85%). 290 S.M. Coyne et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 48 (2010) 288–293 2.2. Questionnaires 2.2.1. Psychopathy Two forms of psychopathy traits were measured using the 26item Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRP; Levenson, Kiehl, & Fitzpatrick, 1995). Primary psychopathy included items measuring selfishness, inability to care, and manipulativeness (e.g., ‘‘In today’s world, I feel justified in doing anything I can get away with to succeed”). Secondary psychopathy included items measuring impulsivity and a self-defeating lifestyle (e.g., ‘‘When I get frustrated, I often ‘let off steam’ by blowing my top”). All responses to items used a 4-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 4 = agree strongly). Internal consistency for both primary (a = .74) and secondary psychopathy (a = .68) scales was acceptable, but only after deleting one item (‘‘I am often bored”) from the secondary psychopathy scale. 2.2.2. Conflict tactics scale (CTS; Straus, 1979) The CTS consists of 19 behaviors that couples often engage in when angry with each other. Participants are asked to rate how frequently they engaged in each behavior (on a 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times in the past year) Likert scale) during the past year. Eleven of the 19 items involve direct physical aggression (e.g., kicked, punched, bit) and were used as a measure of physical aggression in the current study. Though nearly 20% of the sample reported perpetrating at least one act of physical aggression against their partner, four of the most severe items showed no or little variability and were subsequently dropped from the measure. Internal consistency for the remaining seven items was acceptable (a = .83). 2.2.3. Romantic relational aggression (RRA; Linder et al., 2002) Participants’ romantic relational aggression was measured by the RRA scale. This type of aggression specifically focuses on harming or manipulating relationships, not just individuals. The RRA consisted of five questions (e.g., ‘‘I try to make my romantic partner jealous when I am mad at him/her”) measured on a 1 (never) to 7 (very often) Likert scale. Again, internal consistency was acceptable for this measure (a = .73). 2.2.4. Television index Participants also listed their three favorite television programs and rated how frequently they viewed each program on a scale of 1 (not frequent) to 7 (extremely frequent). All the programs listed by participants were then given out to 69 independent undergraduate raters (52% male, M age = 23.43, SD = 6.44) who were asked to estimate how much physical violence and relational aggression (on separate scales) were in each program they were familiar with (i.e., viewed regularly). Raters were provided with detailed definitions and examples of each form of aggression. Ratings were based on a 1 (no aggression) to 7 (extreme amounts of aggression) Likert scale. The raters evaluated a total of 129 different programs. The mean rating from all the raters of a particular show (at least two raters per show) were determined. Intercoder reliability was then assessed with two different methods, consistent with the pattern set by Huesmann, Moise, Podolski, and Eron, 2003. In particular, we determined the means of the inter-rater correlations and average absolute discrepancies from the mean. Raters with a high number of consistent negative correlations (suggesting lack of care in ratings) were omitted. The resulting means for inter-rater correlations were .76 for physical aggression and .65 for relational aggression (using Fisher’s z). The average absolute discrepancy from the mean was .72 for physical aggression and .95 for relational aggression. Aggression ratings for each program were multiplied by the frequency of exposure score to give participants a total media expo- sure score. This commonly used approach gives programs viewed more frequently greater weight in the subsequent analyses (e.g., Huesmann et al., 2003) and is considered more sound than self ratings of media content, given the multi-informant method. 3. Results 3.1. Sex differences Initially, a MANOVA was conducted to explore any sex differences for study scales. This analysis revealed a significant multivariate effect, F (6, 330) = 14.20, p < .001, g2 = .21. Table 1 shows the univariate effects, means, and standard deviations for all variables. Men scored significantly higher than women on primary psychopathy traits and physical aggression viewed on television. Conversely, women scored higher on romantic relational aggression, perpetration of physical aggression, and relational aggression viewed on television. There was no significant sex difference for secondary psychopathy traits. As a result of the above analyses, all remaining analyses will be conducted separately for men and women. 3.2. Correlations Correlations between all variables are shown in Table 2. Both primary and secondary psychopathies were correlated with both types of aggression for men and women (save for physical aggression and primary psychopathy for women). Additionally, both forms of psychopathy were positively correlated with physical and relational aggression viewed on television by men only. Physical and relational aggression viewed on television were positively correlated with both types of aggression for men, but only with RRA for women. 3.3. Main analyses A series of multiple-group, multivariate multiple regressions were conducted with the Analysis of Moments Structure (AMOS) software (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999). Each model was run using full information, maximum likelihood estimation in order to account for any missing data. Additionally, the models were conducted separately for men and women, given the sex difference found in almost all the main variables. Initially, we conducted analyses on the relationship between psychopathy and relationship aggression without media aggression in the model (Figs. 1 and 2). For both men and women, secondary psychopathy was related to both forms of aggression, while primary psychopathy was related to only RRA. Both types of media aggression were then added as mediators to the model. To examine the potential mediation of media aggression, we conducted bootstrapping analyses for indirect effects based on 2000 bootstrap resamples and a 95% CI. The bootstrapping analysis revealed that neither type of media aggression was a significant mediator for the relationship between either type of psychopathy and types of aggression (p > .05 for each indirect path). Indeed, an inspection of the path coefficients revealed little change when media aggression was introduced into the model. Secondary psychopathy still predicts both types of aggression for men and women, and primary psychopathy predicts RRA for women (and for men at the level of a trend). However, some interesting findings did emerge regarding media aggression. Firstly, for men, secondary psychopathy predicted the amount of physical aggression viewed on television which then predicted engagement of physical aggression in relationships. Similarly, secondary psychopathy also predicted exposure to relational aggression on tele- 291 S.M. Coyne et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 48 (2010) 288–293 Table 1 Means and Standard Deviations for all Variables by Sex of Participant. Variable Men Primary psychopathy Secondary psychopathy Physical aggression Romantic relational aggression TV physical aggression TV relational aggression Women Mean SD Mean SD 1.59 1.73 .06 1.31 12.77 14.81 .43 .39 .16 .48 8.06 8.20 1.48 1.70 .20 1.59 10.89 17.67 .34 .41 .56 .73 6.73 8.88 F P g2 6.17 .21 8.66 16.15 5.42 9.25 .01** .65 .003** .001*** .02* .003** .02 .00 .03 .05 .02 .03 Note: df for each result is (1, 346). p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001. * Table 2 Correlations Between All Variables by Sex of Participant. Primary psychopathy Secondary psychopathy Physical aggression Romantic relational aggression TV physical aggression TV relational aggression 1 2 3 4 5 6 – .45*** .05 .32*** .07 .07 .48*** – .31*** .37*** .11 .05 .14+ .25** – .35*** .06 .05 .26** .30*** .07 – .14* .20** .25** .31*** .22** .16* – .78(.49)*** .21** .24** .11 .24** .75(.40)*** – Note: Upper diagonal: correlations for men; lower diagonal: correlations for women. As frequency of viewing the program remains constant for the TV physical and relational ratings, this naturally inflates the strength of the correlation. We have also provided correlations (in parentheses) of only the aggressive content (and not the frequency of viewing) of the programs. Both are significant at the p < .001 level. +p < .10. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001. 0, e1 1 .02/.00 Primary Psychopathy 0, .14 Physical Aggression .24* TV Physical e3 -.12 .14+ .73*** 1 .48*** -.01 .24**/.21** .24** Secondary Psychopathy -.12 TV Relational .22*/.20* .24* 0, Romantic Relational 1 Aggression e4 1 0, e2 Fig. 1. Relation of psychopathy to perpetration of aggression by men as mediated by media aggression. The figure before the slash (/) mark represents the initial association between psychopathy and relationship aggression. The figure after the slash mark represents the association between psychopathy and relationship aggression when media aggression is added to the model. +p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001. vision, which in turn predicted engagement in RRA. For women, psychopathy did not predict engagement with either form of media aggression; however, viewing relational aggression on television did predict engagement in RRA. 4. Discussion The results of this study show psychopathy to be related to relationship aggression, albeit differentially for secondary and primary psychopathy features. Secondary psychopathy traits were strongly related to both types of aggression for both men and women. This provides evidence that individuals with secondary psychopathic traits are likely to use and abuse, even with those who are most intimate to them. Indeed, individuals showing secondary psychopathic features may find intimate relationships particularly potent triggers, as such relationships are likely to involve frequent interactions, conflicts of interest that are not easily resolved, and high rates of aggression from partners (compared to strangers). This is consistent with Skeem et al.’s (2003) comment that anger and violence were likely consequences of an individual with secondary psychopathy traits who anticipated the loss of an interpersonal relationship. Conversely, primary psychopathy features were only related to romantic relational aggression for both men (at the level of a trend) and women. These subtle forms of aggression may be less likely to be recognized by the victimized partner. This may make it easier 292 S.M. Coyne et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 48 (2010) 288–293 0, e1 1 -.12/-.12 Primary Psychopathy 0, .03 Physical Aggression -.02 TV Physical e3 .06 .20**/.18* .79*** 1 .45*** .29*** .36***/.36*** .02 Secondary Psychopathy .28***/.29*** -.11 TV Relational .26* 0, Romantic Relational 1 Aggression e4 1 0, e2 Fig. 2. Relation of psychopathy to perpetration of aggression by women as mediated by media aggression. The figure before the slash (/) mark represents the initial association between psychopathy and relationship aggression. The figure after the slash mark represents the association between psychopathy and relationship aggression when media aggression is added to the model. +p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001. for partners who tend to evince primary psychopathy features to aggress, since subtle manipulation is key to controlling other individuals. Though Coyne and Thomas (2008) found that primary psychopathy was related to both physical and relational aggression in non-romantic relationships, we only found an association with relational aggression when examined in the context of romantic relationships. Indeed, romantic relational aggression represents a distinctly useful way to manipulate one’s partner, as such aggression can be very subtle, yet harmful to the victim. Physical aggression, in contrast, is clearly overt, and the victim has a better understanding of the perpetrator’s intentions and the wrongfulness of such behavior. Therefore, individuals with primary psychopathic tendencies may prefer to tread carefully and use more subtle tactics to control those around them while remaining outwardly reasonable. This is not to say that if such attempts are unsuccessful, anger and physical aggression are not also within their repertoire. It is only to suggest that those with primary psychopathy features may find more overt aggression less successful and therefore less attractive than more subtle manipulation. The relationship between psychopathy and relationship aggression was not mediated by exposure to media aggression. Instead, this relationship indicated a fairly independent direct effect. However, there were a few findings of note regarding media aggression. Firstly, for men, individuals with secondary psychopathic tendencies were more prone to seek out violent media. This is consistent with the uses and gratifications approach (Katz et al., 1974), which theorizes that individuals with a more aggressive personality (including having secondary psychopathy traits) would turn to violence in the media to fulfill a need for aggression. However, this same relationship was not found for primary psychopathy or relational aggression in the media. Accordingly, individuals with primary traits seem to seek out non-media sources to fulfill their needs (which may or may not include aggression). Furthermore, after controlling for psychopathic tendencies, physical aggression viewed on television predicted engagement in physical aggression for men, while relational aggression viewed on television predicted perpetration of RRA for both men and women. This is consistent with a number of studies showing a relationship between exposure to media aggression and subsequent aggressive behavior (e.g., Anderson et al., 2003). However, as stated previously, this effect did not mediate the psychopathy and aggression relationship; instead, media aggression appeared to be having an independent direct effect on relationship aggression. As a whole, it appears that psychopathic tendencies and exposure to media aggression represent two independent routes for increasing the likelihood of aggression in relationships. It appears that it is not necessary for individuals with psychopathic tendencies to view media aggression to engage in relationship abuse. Conversely, having psychopathic tendencies is not a requirement for aggressive behavior after viewing media aggression. Rather, they both evince relationship aggression, albeit through different routes. It is also possible that associations between psychopathy traits, intimate aggression, and television viewing preferences are due not to causation, but instead co-occur due to the influence of shared underlying genetically determined traits such as negative emotionality and daring (Waldman & Rhee, 2007). Meta-analytic research suggests that such underlying traits would directly influence behavior (39% of antisocial traits (which are similar to secondary psychopathy) and 42% of detached traits (which are similar to primary psychopathy). This research, however, also supports the notion that these traits would be subject to the additive influences of non-shared environments (61% antisocial and 58% detached traits), which in turn supports the contention that media viewing may interact with genetic propensities to enhance their phenotypic appearance (Waldman & Rhee, 2007). It should be noted that this study is correlational; as such, we are unable to make any causal explanations regarding psychopathy, media, or relationship aggression. Experimental studies may wish to address this in the future. Furthermore, all questionnaires were self-report, which may encourage underreporting. Accordingly, partner reports could be included in the future to supplement self-reports. In sum, this is the first study to show evidence that psychopathy traits are differentially related to various forms of aggression in romantic relationships in a non-clinical population. Additionally, this is also the first study to illustrate that psychopathy and exposure to different types of media aggression may have independent effects on relationship aggression. These findings then suggest that careful consideration of both personality and environmental influences such as media exposure is needed when examining both the causes and consequences of relationship aggression. References Anderson, C. A., Berkowitz, L., Donnerstein, E., Huesmann, L. R., Johnson, J. D., Linz, D., et al. (2003). The influence of media violence on youth. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 81–110. Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 27–51. Arbuckle, J. L., & Wothke, W. (1999). Amos 4.0 user’s guide. Chicago: Small Waters. Board, B. J., & Fritzon, K. (2005). Disordered personalities at work. Psychology, Crime and Law, 11, 17–32. Book, A. S., & Quinsey, V. L. (2004). Psychopaths: cheaters or warrior-hawks? Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 33–45. S.M. Coyne et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 48 (2010) 288–293 Browne, K. D., & Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. (2005). The influence of violent media on children and adolescents: A public-health approach. Lancet, 365, 702–710. Coyne, S. M., Nelson, D. A., Lawton, F., Haslam, S., Rooney, L., Titterington, L., et al. (2008). The effects of viewing physical and relational aggression in the media: Evidence for a cross-over effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1551–1554. Coyne, S. M., & Thomas, T. J. (2008). Psychopathy, aggression, and cheating behavior: A test of the Cheater-Hawk hypothesis. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1105–1115. Craig, W. (1998). The relationship among bullying, victimization, depression, anxiety, and aggression in elementary school children. Personality and Individual Differences, 24, 123–130. Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Donnerstein, E., Slaby, R. G., & Eron, L. D. (1994). The mass media and youth aggression. In L. D. Eron, J. Gentry, & P. Schlegel (Eds.), Reason to hope: A psychosocial perspective on violence and youth (pp. 219–250). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Falkenbach, D., Poythress, N., & Creevy, C. (2008). The exploration of subclinical psychopathic subtypes and the relationship with types of aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 821–832. Ferguson, C. J., Cruz, A. M., Martinez, D., Rueda, S. M., Ferguson, D. E., & Negy, C. (2008). Personality, parental, and media influences on aggressive personality and violent crime in young adults. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 17, 395–414. Ferguson, C. J., & Kilburn, J. (2009). The public health risks of media violence. A meta-analytic review. Journal of Pediatrics, 154, 759–763. Hare, R. D. (1991). The Psychopathy Checklist—Revised manual. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems. Hare, R. D. (1996). Psychopathy: A clinical construct whose time has come. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 23, 25–54. Hare, R. D. (2003). The Psychopathy Checklist—Revised manual (2nd ed.). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems. Huesmann, L. R. (1986). Psychological processes promoting the relation between exposure to media violence and aggressive behavior by the viewer. Journal of Social Issues, 42, 125–139. Huesmann, R., Moise, J., Podolski, C., & Eron, L. (2003). Longitudinal relations between children’s exposure to television violence and their later aggressive and violent behavior in young adulthood: 1977–1992. Developmental Psychology, 39, 201–221. Huss, M. T., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2006). Identification of the psychopathic batterer: The clinical, legal, and policy implications. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5, 403–422. Karpman, B. (1941). On the need for separating psychopathy into two distinct clinical types: Symptomatic and idiopathic. Journal of Criminology and Psychopathology, 3, 112–137. 293 Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Utilization of mass communication by the individual. In J. G. Blumler & E. Katz (Eds.), The uses of mass communication: Current perspectives on gratifications research (pp. 19–32). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Levenson, M. R., Kiehl, K. A., & Fitzpatrick, C. M. (1995). Assessing psychopathic attributes in a non-institutionalized population. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 151–158. Linder, J. R., Crick, N. R., & Collins, W. A. (2002). Relational aggression and victimization in young adults’ romantic relationships: Associations with perceptions of parent, peer, and romantic relationship quality. Social Development, 11, 69–86. Lynam, D., Whiteside, S., & Jones, S. (1999). Self-reported psychopathy: A validation study. Journal of Personality Assessment, 73, 110–132. Poythress, N. G., & Skeem, J. L. (2007). Disaggregating psychopathy: Where and how to look for subtypes, (pp. 172–192). In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of Psychopathy (pp. 205–250). The Guilford Press: New York. Ray, J., Poythress, N., Weir, J., & Rickelm, A. (2009). Relationships between psychopathy and impulsivity in the domain of self-reported personality features. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 83–87. Schmeelk, K. M., Sylvers, P., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2008). Trait correlates of relational aggression in a nonclinical sample: DSM-IV personality disorders and psychopathy. Journal of Personality Disorders, 22, 269–283. Skeem, J. L., Poythress, N., Edens, J. F., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Cale, E. M. (2003). Psychopathic personality or personalities? Exploring potential variants of psychopathy and their implications for risk assessment. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 513, 546. Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence. The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 75–88. Swogger, M. T., Walsh, Z., & Kosson, D. S. (2007). Domestic violence and psychopathic traits: Distinguishing the antisocial batterer from other antisocial offenders. Aggressive Behavior, 33, 253–260. Waldman, I. D., & Rhee, S. H. (2007). Genetic and environmental influences on psychopathy and antisocial behavior. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of Psychopathy (pp. 205–250). The Guilford Press: New York. Wareham, J., Dembo, R., Poythress, N., Childs, K., & Schmeidler, J. (2009). A latent class factor approach to identifying subtypes of juvenile diversion youths based on psychopathic features. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 27, 71–95. Warren, G. C., & Clarbour, J. (2009). Relationship between psychopathy and indirect aggression use in a noncriminal population. Aggressive Behavior, 35, 408–421. Zilmann, D., & Weaver, J. B. (1997). Psychoticism in the effect of prolonged exposure to gratuitous media violence on the acceptance of violence as a preferred means of conflict resolution. Personality and Individual Differences, 22, 613–627.