STANLEY B. BLOCK

Texas Christian University

GEOFFREY A. HIRT

DePaul University

BARTLEY R. DANIELSEN

North Carolina State University

J. DOUGLAS SHORT

Northern Alberta Institute of Technology

MICHAEL A. PERRETTA

Sheridan College Institute of Technology

and Advanced Learning (RT) and University of

Waterloo (RT)

FOUNDATIONS OF FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT

TENTH CANADIAN EDITION

Copyright © 2015, 2012, 2009, 2005, 2003, 2000, 1997, 1994, 1991, 1988 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. Copyright 2014, 2011, 2009, 2008 by McGraw-Hill Education LLC. All rights reserved. No

part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a

data base or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited, or

in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from The Canadian Copyright

Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Statistics Canada information is used with the permission of Statistics Canada. Users are forbidden

to copy the data and redisseminate them, in an original or modified form, for commercial purposes,

without permission from Statistics Canada. Information on the availability of the wide range of data

from Statistics Canada can be obtained from Statistics Canada’s Regional Offices, its World Wide

Web site at www.statcan.gc.ca, and its toll-free access number 1-800-263-1136.

The Internet addresses listed in the text were accurate at the time of publication. The inclusion of a

Web site does not indicate an endorsement by the authors or McGraw-Hill Ryerson, and McGraw-Hill

Ryerson does not guarantee the accuracy of the information presented at these sites.

ISBN-13: 978-1-25-902497-9

ISBN-10: 1-25-902497-0

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 CTPS 1 9 8 7 6 5

Printed and bound in China.

Care has been taken to trace ownership of copyright material contained in this text; however, the

publisher will welcome any information that enables them to rectify any reference or credit for

subsequent editions.

Director of Product Management: Rhondda McNabb

Senior Product Manager: Kimberley Veevers

Executive Marketing Manager: Joy Armitage Taylor

Product Developer: Erin Catto

Senior Product Team Associate: Marina Seguin

Supervising Editor: Jessica Barnoski

Photo/Permissions Editor: Derek Capitaine

Copy Editor: Julie van Tol

Plant Production Coordinator: Scott Morrison

Manufacturing Production Coordinator: Lena Keating

Cover Design: Mark Cruxton

Cover Image: Chris Schmid/Getty Images

Interior Design: Mark Cruxton

Page Layout: Tom Dart, Kim Hutchinson, First Folio Resource Group Inc.

Printer: China Translation & Printing Services Limited

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Block, Stanley B., author

Foundations of financial management / Stanley B. Block (Texas

Christian University), Geoffrey A. Hirt (DePaul University), Bartley R. Danielsen (North Carolina State

University), J. Douglas Short (Northern Alberta Institute of Technology), Michael Perretta (Sheridan

College Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning). -- Tenth Canadian edition.

Includes index.

Revision of: Foundations of financial management / Stanley B. Block … [et al.]. -- 9th Canadian

ed. -- [Whitby, Ont.] : McGraw-Hill Ryerson, ©2012.ISBN 978-1-259-02497-9 (bound)

1. Corporations--Finance--Textbooks. I. Hirt, Geoffrey A., author II. Short, J. Douglas, author III.

Danielsen, Bartley R., author IV. Perretta, Michael, author V. Title.

HG4026.B56 2015 658.15 C2014-906529-9

Passion and reason in all that you do and feel.

To those I love.

Doug

To all my past, current, and future students…

aim for higher expectations!

Michael

BRIEF CONTENTS

PA RT 1

I N TRO DU C TIO N

1

1

13

THE GOALS AND FUNCTIONS OF

FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT 1

PART 5

PA RT 2

PA RT 3

PA RT 4

iv

RISK AND CAPITAL

BUDGETING 448

LONG-T ERM F INAN C IN G

48 4

FI NA NCI AL ANA LYSIS

AND PLA NN ING 22

14

CAPITAL MARKETS 484

15

INVESTMENT UNDERWRITING

2

REVIEW OF ACCOUNTING 22

16

3

FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

LONG-TERM DEBT AND LEASE

FINANCING 537

4

FINANCIAL FORECASTING

17

5

OPERATING AND FINANCIAL

LEVERAGE 126

COMMON AND PREFERRED STOCK

FINANCING 581

18

DIVIDEND POLICY AND RETAINED

EARNINGS 609

19

DERIVATIVE SECURITIES 641

58

93

WORK IN G CAPITAL

M AN AGE MEN T 1 6 4

PART 6

EXPANDING THE PERSPECTIVE

OF CORPORATE FINANCE 674

6

WORKING CAPITAL AND THE

FINANCING DECISION 164

7

CURRENT ASSET

MANAGEMENT 201

20

EXTERNAL GROWTH THROUGH

MERGERS 674

8

SOURCES OF SHORT-TERM

FINANCING 237

21

INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL

MANAGEMENT 701

TH E CA PITA L B U DG ET ING

PR OCESS 26 6

9

THE TIME VALUE OF MONEY 266

10

VALUATION AND RATES OF

RETURN 304

11

COST OF CAPITAL 340

12

THE CAPITAL BUDGETING

DECISION 393

Brief Contents

510

APPENDICES

GLOSSARY

INDEX

IN-1

735

GL-1

CONTENTS

PART 1

1

PART 2

2

IN TRO DU C TIO N

Statement of Cash Flows 34

Developing an Actual Statement 34

Determining Cash Flows from Operating

Activities 35

Determining Cash Flows from Investing

Activities 38

Determining Cash Flows from Financing

Activities 38

Combining the Three Sections of the

Statement 38

Amortization and Cash Flow 40

Free Cash Flow 41

Income Tax Considerations 42

Corporate Tax Rates 42

Effective Tax Rate Examples 43

Personal Taxes 44

Cost of a Tax‐Deductible Expense 45

Amortization (Capital Cost Allowance) as a

Tax Shield 45

Summary 47

1

THE GOALS AND FUNCTIONS OF

FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT 1

The Field of Finance 2

Evolution of Finance as a Discipline 3

Goals of Financial Management 5

Maximizing Shareholder Wealth 5

Measuring the Goal 6

Market Share Price 6

Management and Shareholder Wealth 7

Social Responsibility 8

Ethical Behaviour 9

Functions of Financial Management 11

Forms of Organization 12

The Role of the Financial Markets 14

Structure and Functions of the Financial

Markets 14

Allocation of Capital 14

Risk 15

Format of the Text 17

Parts 17

Summary 19

3

FINANCIAL ANALYSIS 58

Ratio Analysis 59

Ratios for Comparative Purposes 59

Classification System 59

The Analysis 60

DuPont Analysis 62

Interpretation of Ratios by Trend

Analysis 67

Distortion in Financial Reporting 71

Inflationary Impact 71

Disinflation Effect 73

Valuation Basics with Changing Prices 73

Accounting Discretion 73

Summary 76

4

FINANCIAL FORECASTING 93

The Financial Planning Process 94

Constructing Pro Forma Statements 95

FIN AN CI AL A NALYSIS AND

P LAN NIN G 22

REVIEW OF ACCOUNTING 22

Income Statement 23

Return on Capital 24

Valuation Basics from the Income

Statement 25

Limitations of the Income Statement 27

Balance Sheet 28

Effects of IFRS on Financial Analysis 28

Interpretation of Balance Sheet Items 29

Valuation Basics from the Balance

Sheet 32

Limitations of the Balance Sheet 32

Contents

v

Pro Forma Income Statement 96

Establish a Sales Projection 97

Determine a Production Schedule and the

Gross Profit 97

Other Expense Items 100

Actual Pro Forma Income Statement 100

Cash Budget 101

Cash Receipts 101

Cash Payments 103

Actual Budget 104

Pro Forma Balance Sheet 105

Explanation of Pro Forma Balance

Sheet 106

Analysis of Pro Forma Statement 108

Percent‐of‐Sales Method 108

Sustainable Growth Rate 111

Summary 113

5

PA RT 3

6

vi

Short‐Term Financing (Risky) 177

The Financing Decision 178

Term Structure of Interest Rates 178

Term Structure Shapes 181

Interest Rate Volatility 182

A Decision Process 183

Introducing Varying Conditions 183

An Expected Value Approach 184

Shifts in Asset Structure 185

Toward an Optimal Policy 186

Summary 188

7

CURRENT ASSET MANAGEMENT 201

Cost‐Benefit Analysis 202

Cash Management 203

Reasons for Holding Cash Balances 204

Collections and Disbursements 205

Float 204

Improving Collections and Extending

Disbursements 204

Electronic Funds Transfer 206

Cash Management Analysis 207

International Cash Management 207

Marketable Securities 209

The Rates and Securities 211

Management of Accounts

Receivable 214

Accounts Receivable as an

Investment 214

Credit Policy Administration 215

An Actual Credit Decision 208

Another Example of a Credit

Decision 219

Inventory Management 220

Level versus Seasonal Production 221

Inventory Policy in Inflation (and

Deflation) 221

The Inventory Decision Model 222

Safety Stock and Stockouts 224

Just‐in‐Time Inventory Management 225

Summary 227

8

SOURCES OF SHORT-TERM

FINANCING 237

Cost of Financing Alternatives 238

Trade Credit 238

Payment Period 239

Cash Discount Policy 239

Net Credit Position 240

Bank Credit 241

Demand Loans and the Prime Rate 241

Fees and Compensating Balances 242

Maturity Provisions 243

Cost of Bank Financing 243

Interest Costs with Fees or Compensating

Balances 244

OPERATING AND FINANCIAL

LEVERAGE 126

Leverage in a Business 127

Operating Leverage 128

Break‐Even Analysis 128

A More Conservative Approach 131

The Risk Factor 131

Cash Break‐Even Analysis 131

Degree of Operating Leverage 133

Limitations of Analysis 134

Financial Leverage 135

Impact on Earnings 136

Degree of Financial Leverage 137

The Indifference Point 139

Valuation Basics with Financial

Leverage 140

Leveraged Buyout 141

Combining Operating and Financial

Leverage 142

Degree of Combined Leverage 142

A Word of Caution 144

Summary 145

WORK IN G CAPITAL

M AN AGE MEN T 1 6 4

WORKING CAPITAL AND THE FINANCING

DECISION 164

The Nature of Asset Growth 166

Controlling Assets—Matching Sales and

Production 167

Temporary Assets under Level

Production—an Example 169

Cash Flow Cycle 172

Patterns of Financing 175

Alternative Plans 176

Long‐Term Financing (Conservative) 176

Contents

Rate on Instalment Loans 245

The Credit Crunch Phenomenon 246

Annual Percentage Rate 247

Financing through Commercial

Paper 247

Advantages of Commercial Paper 248

Limitations on the Issuance of

Commercial Paper 249

Bankers’ Acceptances 250

Foreign Borrowing 250

Use of Collateral in Short‐Term

Financing 251

Accounts Receivable Financing 251

Pledging Accounts Receivable 252

Factoring Receivables 252

Asset‐Backed Securities 253

Inventory Financing 254

Stages of Production 254

Nature of Lender Control 255

Appraisal of Inventory Control

Devices 255

Hedging to Reduce Borrowing Risk 255

Summary 257

PART 4

9

Patterns of Payment 284

Perpetuities 286

Growing Annuity (with End Date) 286

Canadian Mortgages 287

A Final Note 288

Summary 289

Appendix 9A: Derivation of Time‐Value‐

of‐Money Formulas 300

10

VALUATION AND RATES OF RETURN 304

Valuation Concepts 305

Yield 305

Valuation of Bonds 307

Time and Yield to Maturity—Impact on

Bond Valuation 309

Time to Maturity 312

Determining Yield to Maturity from the

Bond Price 313

Semiannual Interest and Bond Prices 315

Valuation of Preferred Stock 316

Determining the Required Rate of Return

(Yield) from the Market Price 317

Valuation of Common Stock 318

No Growth in Dividends 318

Constant Growth in Dividends 319

Determining the Inputs for the Dividend

Valuation Model 320

Determining the Required Rate of Return

from the Market Price 322

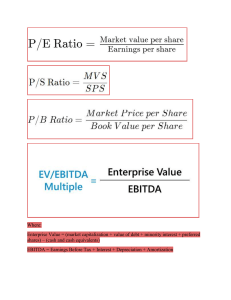

The Price‐Earnings Ratio Concept and

Valuation 322

Variable Growth in Dividends 323

Summary and Review of Formulas 325

Appendix 10A: The Bond Yield to Maturity

Using Interpolation 335

Appendix 10B: Valuation of a

Supernormal Growth Firm 336

11

COST OF CAPITAL 340

The Overall Concept 341

Cost of Debt 343

Cost of Preferred Stock 346

Cost of Common Equity 347

Valuation Approach (Dividend Model) 348

Cost of Retained Earnings 349

Cost of New Common Stock 350

CAPM for the Required Return on

Common Stock 351

Overview of Common Stock Costs 353

Optimal Capital Structure—Weighting

Costs 353

Market Value Weightings 355

Calculating Market Value Weightings 356

Capital Acquisition and Investment

Decision Making 357

TH E CAPITAL B UD G ET ING

P RO CE SS 2 6 6

THE TIME VALUE OF MONEY 266

Application to the Capital Budgeting

Decision and the Cost of Capital 268

Future Value (Compound Value)—Single

Amount 269

Annual Interest Rates—Effective and

Nominal 271

Present Value (Discounted Value)—Single

Amount 273

Future Value (Cumulative Future

Value)—Annuity 274

Future Value—Annuity in Advance

(Annuity Due) 275

Present Value (Cumulative Present

Value)—Annuity 276

Present Value—Annuity in Advance 277

Determining the Annuity Value 277

Annuity Equalling a Future Value (Sinking‐

Fund Value) 278

Annuity Equalling a Present Value (Capital

Recovery Value) 279

Formula Summary 280

Determining the Yield on an

Investment 281

Yield—Present Value of a Single

Amount 281

Yield—Present Value of an Annuity 283

Special Considerations in Time Value

Analysis 283

Contents

vii

Risk and the Capital Budgeting

Process 455

Risk‐Adjusted Discount Rate 455

Increasing Risk over Time 455

Qualitative Measures 457

Certainty Equivalents 459

Computer Simulation Models 460

Sensitivity Analysis 460

Decision Trees 461

The Portfolio Effect 462

Portfolio Risk 462

An Example of Portfolio Risk

Reduction 465

Evaluation of Combinations 467

The Share Price Effect 467

Summary 468

Cost of Capital in the Capital Budgeting

Decision 358

The Marginal Cost of Capital 360

Summary 364

Appendix 11A: Cost of Capital and the

Capital Asset Pricing Model 376

Appendix 11B: Capital Structure Theory

and Modigliani and Miller 386

12

13

viii

THE CAPITAL BUDGETING DECISION 393

Administrative Considerations 394

The Notion of Resultant Cash Flows 395

Accounting Flows versus Cash Flows 397

Methods of Evaluating Investment

Proposals 399

Average Accounting Return 399

Establishing Cash Flows 400

Payback Period 401

Net Present Value 402

Internal Rate of Return 403

Profitability Index 407

Summary of Evaluation Methods 408

Selection Strategy 408

Mutually Exclusive Projects 408

Discounting Consideration 409

Modified Internal Rate of Return 410

Multiple Internal Rates 410

Capital Rationing 411

Net Present Value Profile 413

Characteristics of Investment C 414

Capital Cost Allowance 416

Addition and Disposal of Assets 418

Straight‐Line CCA Classes 419

Investment Tax Credit 419

Combining CCA with Cash Flow

Analysis 420

A Decision 422

IRR Solution 423

Comprehensive Investment Analysis

(NPV) 423

Incremental CCA Tax Savings

(Shields) 424

Cost Savings 424

Other Resultant Costs 424

Discounted Cash Flow Models—the

Difficulties 426

Suggested Considerations for NPV

Analysis 427

Summary 428

RISK AND CAPITAL BUDGETING 448

Risk in Valuation 449

The Concept of Risk Aversion 450

Actual Measurement of Risk 451

Risk in a Portfolio 453

Contents

PART 5

LONG-T ERM F INAN C IN G

48 4

14

CAPITAL MARKETS 484

The Structure 485

Competition for Funds in the Capital

Markets 487

Government Securities 489

Government of Canada Securities 489

Provincial and Municipal Government

Bonds 490

Corporate Securities 490

Corporate Bonds 490

Preferred Stock 490

Common Stock 491

Corporate Financing in General 491

Internal versus External Sources of

Funds 492

The Supply of Capital Funds 493

The Role of the Security Markets 494

The Organization of the Security

Markets 496

The Organized Exchanges 496

The Over‐the‐Counter Markets 499

Challenges for the Canadian

Exchanges 500

Market Efficiency 501

Criteria of Efficiency 502

The Efficient Market Hypothesis 503

Securities Regulation 505

Summary 507

15

INVESTMENT UNDERWRITING 510

The Investment Industry 511

The Role of the Investment Dealer 511

Enumeration of Functions 512

The Distribution Process 513

The Spread 514

Pricing the Security 516

Dilution 516

Market Stabilization 517

Aftermarket 517

The Securities Industry in Canada 517

Underwriting Activity in Canada 519

Size Criteria for Going Public 519

Public versus Private Financing 520

Advantages of Being Public 520

Disadvantages of Being Public 520

Venture Capital 520

Initial Public Offerings 521

Private Placement 522

Going Private and Leveraged

Buyouts 522

Mergers, Acquisitions, and

Privatization 523

Summary 525

16

LONG-TERM DEBT AND LEASE

FINANCING 537

The Expanding Role of Debt 538

The Debt Contract 538

Restrictive Covenants 539

Security Provisions 539

Unsecured Debt 540

Methods of Repayment 541

Bond Prices, Yields, and Ratings 542

Bond Yields 543

Bond Ratings 544

Examining Actual Bond Offerings 545

The Refunding Decision 546

A Capital Budgeting Problem 546

Other Forms of Bond Financing 549

Zero‐Coupon Bond 549

Strip Bond 549

Strip Bond Illustrated 550

Floating‐Rate Bond 550

Real Return Bond 551

Revenue Bond 551

Eurobond Market 551

Corporate Debt for the Medium

Term 552

Term Loans 552

Operating Loans 552

Medium‐Term Notes 552

Mortgage Financing 553

Criteria for Approval 553

Application Requirements 554

Mortgage Term and Amortization 554

Asset‐Backed Securities 554

Advantages and Disadvantages of

Debt 555

Leasing as a Form of Debt 555

Capital Lease versus Operating Lease 556

Advantages of Leasing 557

Lease‐versus‐Purchase Decision 558

Summary 562

Appendix 16A: Financial Alternatives for

Distressed Firms 573

17

COMMON AND PREFERRED STOCK

FINANCING 581

Common Shareholders’ Claim to

Income 582

The Voting Right 582

Cumulative Voting Example 583

The Right to Purchase New Shares 585

The Use of Rights in Financing 585

Effect of Rights on Shareholder’s

Position 588

Rights Offering: No Wealth Increase 588

Desirable Features of Rights Offerings 589

American Depository Receipts

(ADRs) 589

Poison Pills 590

Preferred Stock 590

Justification for Preferred Stock 591

Provisions Associated with Preferred

Stock 593

Income Trusts 594

Comparing Features of Common and

Preferred Stock and Debt 595

Summary 597

18

DIVIDEND POLICY AND RETAINED

EARNINGS 609

Dividend Theories 610

The Marginal Principle of Retained

Earnings 610

Residual Theory 610

An Incomplete Theory 611

Arguments for the Irrelevance of

Dividends 611

Arguments of the Relevance of

Dividends 612

Dividends in Practice 613

Dividend Payouts 613

Dividend Yields 614

Dividend Stability 615

Other Factors Influencing Dividend

Policy 616

Legal Rules 616

Cash Position of the Firm 617

Access to Capital Markets 617

Desire for Control 617

Tax Position of Shareholders 617

Life Cycle Growth and Dividends 618

Dividend Payment Procedures 620

Stock Dividend 621

Contents

ix

Terms of Exchange 683

Cash Purchases 683

Stock‐for‐Stock Exchange 684

Market Value Maximization 685

Portfolio Effect 686

Accounting Considerations in Mergers

and Acquisitions 687

Premium Offers and Stock Price

Movements 688

Mergers and the Market for Corporate

Control 689

Holding Companies 690

Drawbacks 691

Summary 692

Accounting Considerations for a Stock

Dividend 621

Value to the Investor 622

Possible Value of Stock Dividends 622

Use of Stock Dividends 623

Stock Splits 624

Repurchase of Stock as an Alternative to

Dividends 625

Other Reasons for Repurchase 626

Dividend Reinvestment Plans 626

Summary 628

19

DERIVATIVE SECURITIES 641

Forwards 642

Futures 644

Options 648

Call Option 649

Put Option 651

Options versus Futures 652

Options Issued by Corporations 652

Convertible Securities 652

Value of the Convertible Bond 653

Is This Fool’s Gold? 655

Advantages and Disadvantages to the

Corporation 655

Forcing Conversion 656

Accounting Considerations with

Convertibles 657

Some Final Comments on Convertible

Securities 658

Warrants 658

Valuation of Warrants 660

Use of Warrants in Corporate

Finance 661

Accounting Considerations with

Warrants 662

Comparisons of Rights, Warrants, and

Convertibles 662

Summary 663

21

PA RT 6

EXPANDING THE PERSPECTIVE

OF CORPORATE FINANCE 6 74

20

EXTERNAL GROWTH THROUGH

MERGERS 674

The International and Canadian Merger

Environment 675

Negotiated versus Tendered Offers 677

The Domino Effect of Merger Activity 678

Foreign Acquisitions 679

Government Regulation of Takeovers 680

Motives for Business Combinations 680

Financial Motives 681

Nonfinancial Motives 682

Motives of Selling Shareholders 683

x

INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL

MANAGEMENT 701

The Scope 702

Trade 702

Capital Investment 704

Reasons for Capital Investment 704

The Risks 707

Foreign Exchange Risk 707

Exchange Rates 707

Exchange Rate Exposure 709

Political Risk 711

Exchange Rate Management 712

Factors Influencing Exchange Rates 712

Spot Rates and Forward Rates 714

Cross Rates 715

Hedging (Risk Reduction)

Techniques 716

The Multinational Corporation 719

Financing International Business

Operations 720

Funding of Transactions 720

Global Cash Management 724

Summary 725

Appendix 21A: Cash Flow Analysis and the

Foreign Investment Decision 730

APPENDICES 735

A. Future Value of $1, FVIF 736

B. Present Value of $1, PVIF 738

C. Future Value of an Annuity of $1,

FVIFA 740

D. Present Value of an Annuity of $1,

PVIFA 742

E. Using Calculators for Financial

Analysis 744

GLOSSARY

INDEX

Contents

www.tex-cetera.com

IN-1

GL-1

PREFACE

The daily events of business news, the dynamics of the capital markets, and the deals that

change enterprises encompass the world of finance. The dynamics of recent history are

particularly startling. Too often, the finance discipline is considered challenging by students

because we make its concepts overly complicated. Although finance has unique language

and terms, it relies on some fairly basic, commonsensical ideas. Foundations of Financial

Management is committed to making finance accessible to you.

As always, this edition incorporates content and presentation revisions to make the text an

even better tool for providing you with the skills and confidence you’ll need to be an effective

financial manager. Concepts are explained in a clear and concise manner with numerous

“Finance in Action” boxes highlighting real-world examples and employing Internet resources

to reinforce and illustrate these concepts. The extensive and varied problem material helps to

reinforce financial concepts in more detail. The text is committed to presenting finance in an

enlightening, interesting, and exciting manner.

REINFORCING PREREQUISITE KNOWLEDGE

Employers of business graduates report that the most successful analysts, planners, and

executives have both ability and confidence in their financial skills. We couldn’t agree more.

One of the best ways to increase your ability in financial planning is to integrate knowledge

from prerequisite courses. Therefore, this text is designed to build on your knowledge from

basic courses in accounting and economics, with some statistics thrown in for good measure.

By applying tools learned in these courses, you can develop a conceptual and analytical

understanding of financial management.

For some of you, a bit of time has passed since you’ve completed your accounting

courses. Therefore, included in Chapter 2 is a basic review of financial statements based

on Accounting Standards for Private Enterprises (ASPE) and International Financial Reporting

Standards (IFRS) for public companies, finance terminology, and basic tax effects. With a

working knowledge of that chapter, you will have a more complete understanding of financial

statements, the impact of your decisions on financial results, and how financial statements

can serve you in making effective financial decisions. Furthermore, as you are about to begin

your career, you will be better prepared when called on to apply financial concepts.

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

xi

FLEXIBILITY

Foundations of Financial Management covers all core topics taught in a financial management

course. However, it is almost impossible to cover every topic included in this text in a single

course. This book has therefore been carefully crafted to ensure a flexibility that accommodates

different course syllabi and a variety of teaching approaches. We encourage instructors to use

an approach to the text that works best for them and for the student.

Financial management’s three basic concerns are the management of working capital,

the effective allocation of capital by means of the capital budgeting decision, and the

raising of long‐term capital with an appropriate capital structure. These topics are covered

in Parts 3, 4, and 5 of the text. An introduction to financial management in Part 1 and to

financial analysis and planning in Part 2 precede these central parts. A broader perspective

on finance is addressed in Part 6.

There is continual debate on the best method to present the time‐value‐of‐money

concepts. To allow for the range of opinion, formulas, tables, and calculator presentations

and solutions are available. Although this is sometimes cumbersome, an attempt has been

made to separate the different approaches with colour shading. Choose the method that

works best for you.

NEW FOR THE 10TH EDITION

Throughout the 10th edition there have been timely updates to the “Finance in Action”

(FIA) boxes, figures, and tables as finance continually changes, often in a dramatic

fashion. With a mix of familiar examples from the markets to illustrate financial concepts,

new examples have been added as appropriate. Instructors who have used this text before

will find it familiar, and yet significant improvements have also been made in both the

content in the book and the supplements that accompany it.

•

Updated content on the IFRS and its impact on finance in Canada is now included.

•

Lessons learned from the 2008 financial crisis have been incorporated.

•

Streamlined discussions by casting these in bullet‐point form when appropriate. This

has been a delicate process. Nevertheless, the pay‐off for students is that it allows them

to focus attention more acutely on key ideas.

•

All FIA boxes have been re‐examined for appropriateness and have been updated as

required. Web links have been updated to help students explore further research on

these topics.

•

Problem sets have been extensively changed from the 9th edition. Also, new problems

have been added, as requested by reviewers.

In Part 1, the Introduction, we lay the groundwork for the dynamic nature of finance,

including a discussion of the $19 billion purchase of WhatsApp by Facebook, as the

technology world continues to amaze us with it’s market valuations.

In Part 2, Financial Analysis and Planning, we reflect the changes in accounting and tax

rules, as well as financial presentation.

In Part 3, Working Capital and the Financing Decision, we note the changes in working capital

positions due to the cash hoarding of firms, reflecting their conservatism, resulting from the

most severe financial recession since the 1930s. We can tie this into the healthy dividends

and share repurchases discussed in Chapter 18. This conservatism and risk aversion is seen

in the significant drop in short‐term financing by way of commercial paper and asset‐backed

securities. The implications of the low interest rate environment are also noted.

In Part 4, the Capital Budgeting Process, we add where appropriate screen shots of

spreadsheets to illustrate calculations. With bond yields we note the risk to prices from

any upward yield movements. In the FIAs we highlight the drop in R&D spending by

BlackBerry, replaced as the largest R&D spender by Bombardier. The Northern Gateway

xii

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

pipeline as a capital budgeting strategy is highlighted. Adjustments have been made for the

impact of the lower tax rate environment and its impact on capital budgeting decisions.

WestJet, now an established airline, has been successful in a very risky business and has

now been joined by Porter Airlines.

In Part 5, Long Term Financing, the capital markets chapter is extensively revised to show

the significant relative increase in corporate borrowing, the banks’ continuing domination

in financial intermediation although activity is tempered by pension and mutual funds,

and ongoing globalization controlled to some extent by local regulatory concerns. Income

trusts and asset‐backed securities have retreated in influence, and the FIA in Chapter 16,

“Know What You Are Buying,” points out how we sometimes forget to examine the assets

behind the financial security. Alibaba, the Chinese online retail facilitator is highlighted as

it was poised to become the largest IPO in history, also demonstrating the influence of the

Chinese retail market. The shifting markets, from bond rates and tax changes (dividend

tax credit) and Microsoft entering the stage of its lifecycle where growth has slowed

and dividends replaced capital gains are all examined and noted. The continuing use of

convertible securities by less credit worthy firms is seen in the derivatives chapter.

In Part 6, the mergers and acquisitions chapter notes the presence of sovereign

governments, such as China and Malaysia, as players particularly in the energy sector,

and the reorganizations taking place in the retail sector (Hudson’s Bay/Saks, Loblaw). The

international financial management chapter continues to emphasis the significance the

global market plays for Canada and the volatility of the exchange markets.

ETHICAL BEHAVIOUR AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

The approach is to lay out in Chapter 1 an ethical framework from which financial

management practices can be examined. The agency conflict related to good corporate

governance can be examined in the context of establishing the goal of the firm. Numerous

FIA boxes raise issues for discussion and research by students.

The discussion in Chapter 1 begins with socially desirable actions from an example of

a responsible Canadian corporation.

A good ethical practice framework focuses first on fairness, tying into the rules and

regulatory environment within which the firm operates and the changes that take place. It

then identifies honesty as requiring timely, relevant, and reliable financial reporting. (This

framework can be used to discuss several FIA topics.)

Good corporate governance practices and recent changes are tied into several

chapters and to resources that include academic research and the Canadian Coalition for

Good Governance.

The discussions on market efficiency and securities regulation in Chapter 14 and what

makes for good regulation should be tied into discussions of good corporate governance.

FIAS

Chapter 1

“Are Executive Salaries Fair?”

Chapter 2

“Apparently Earnings Are Flexible”; “Meeting the Targets!”

Chapter 3

“Taking a Big Bath”

Chapter 7

“Why Are Firms Holding Such High Cash Balances”

Chapter 10

“Diamonds, Nickel, Gold, or BlackBerry—for Value?”

Chapter 11

“Canadian Utilities, Return on Common Equity, and Cost of Capital”

Chapter 12

“Strategies: Right or Wrong?”

Chapter 14

“Listing Requirements”; ”Do Financial Statements Tell the Truth”

Chapter 15

“To Market! To Market!”

Chapter 16

“The Prospectus”; “Before the Fall”

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

xiii

Chapter 17

“A Claim to Income and a Right to Vote?”; “An Expensive Pill to Swallow”

Chapter 18

“Pay Those Dividends!”

Chapter 19

“The Derivatives Market”

Chapter 21

“Whiskey Is Risky!”

RISK

Risk is identified in Chapter 1 as one of the key concepts of finance (sometimes neglected)

in determining value. Consideration of risk is interwoven throughout the text with

discussion and FIA boxes. The general concept of volatility is illustrated, to be examined

more extensively, particularly in Chapter 13 through statistical measures. Chapter 1

suggests the early warning signs of the 2008 market downturn found in the Treasury‐bill–

commercial paper yield spread.

In Chapter 2 rule‐of‐thumb risk measures of price‐earnings and market to book ratios are

examined from a financial statement perspective. Additionally, tax rule changes identify risk.

In Chapter 3 ratio analysis is seen in the context of gauging pressure points increasing

risk within the firm, while Chapter 4 explores the risks and sensitivities of forecasting.

Chapter 5 is the first full chapter exploring risk from the leverage perspective, identifying

business, operating, and financial risk.

Hedging across the balance sheet is established in the context of risk reduction in

Chapter 6, while volatility is viewed through interest rate changes. Chapter 8 assesses the

credit crunch phenomenon that reappears time and time again.

In Chapter 10 there is the risk premium discussion on required rates of returns (yields),

with Chapter 11 exploring risk within the overall concept of the cost of capital. Additionally

the CAPM risk return model is introduced. It is within Chapter 13 that three significant

questions related to risk are identified. The distinction between total risk (coefficient of

variation) and systematic risk (beta) is highlighted. Risk reduction through the portfolio

effect is constructed statistically with important conclusions and follow‐up problems.

In Chapter 19 risk reduction from derivatives is illustrated, and is tied back to leverage in

Chapter 5 and hedging in Chapter 6. Chapter 21 examines risk reduction through international

diversification, and the volatility of the Canadian dollar in 2007–2014 (Figure 21–9)

is illustrated.

FIAS

xiv

Chapter 1

“The Foundations”; “The Markets Reflect Value, Yields, and Risk”

Chapter 2

“Apparently Earnings Are Flexible”; “Corporate Tax Rules”

Chapter 3

“Applying DuPont Analysis on the Rails”; “Taking a Big Bath”

Chapter 4

“Oil Prices! How about a Forecast?”; “Operational Cash Flow Exceeds

Earnings and Allows Capital Expenditures”

Chapter 5

“Big Leverage! Big Losses! Big Gains! Insolvency! Rebirth!”; “Leverage of

Twenty Times Equity”

Chapter 7

“Treasury Bills, Not ABCP, for Liquidity and Safety”, “Why Are Firms Holding

Such High Cash Balances”

Chapter 8

“CN Rail Maintains a Negative Trade Credit Position”; “Liquid Assets as

Collateral: It Goes Down Well”

Chapter 10

“Market Yields and Market Values”; “The Ups and Downs of Bond Prices”

Chapter 11

“Debt Costs around the Globe”

Chapter 13

“Financial Crisis 2008, U.S. Government Default 2011, Crimea Conflict 2014:

How Do You Get a Risk Reading?”

Chapter 20

“Are Diversified Firms Winners or Losers?”; “Refocusing Strategies”

Chapter 21

“Whiskey Is Risky!”; “Rating the Countries”

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

PEDAGOGY

To provide guidance and insights throughout the text, we incorporate a number of proven

pedagogical aids, including:

Learning Objectives At the beginning of each chapter, learning objectives will help

A R T learning

2

focus Pyour

as you proceed through the material. The summary of each chapter

responds

objectives

F I NtoAeach

N C IofAthese

A Nobjectives.

A LY S I Learning

AND P

L A N N are

N Gtagged in‐chapter and with

end‐of‐chapter questions.

Review of Accounting

CHAPTER 3

Financial Analysis

CHAPTER 4

Financial Forecasting

CHAPTER 5

Operating and Financial Leverage

REVIEW OF

ACCOUNTING

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LO1

Prepare and analyze the four basic

financial statements.

LO2

Examine the limitations of the income

statement as a measure of a firm’s

profitability.

Calculators When the use of a calculator is illustrated, a calculator icon appears in the

margin. Appendix E demonstrates the use of the three most commonly used business

calculators, with the illustrations in the text tending to conform to the Sharp calculator.

Chapter 9 demonstrates the use of a calculator with time lines, and the use of tables (as

an option). The formulas for present value analysis, which are the basis for calculators,

tables, or computers, have been included. Answers computed with the calculator will be

V lues are s ated on historic o origi al cost as for pr v t compan es ut

more accurate than those

provided

by

the tables,

due to the roundinga of the table factors.

b

s

F

A financial calculator tutorial

usingmore

thethan

TI BA

canorbe

found

Connect.

considerably

thei II

o Plus

i inal cost

may

requireon

many

times the

“Finance in Action” Boxes These popular boxes address topics related to the chapter

subject matter and deal with the difficulties and opportunities in the financial markets.

Ta b e 2– 5

Ma require

ket Value Internet

Book Valu searches

Ratio of Market

Questions

appropriate to the topic often

for Value

background

p

C mp

information

for Fhelp

in

analysis.

Rewarding

discussions

of

current

and

historical

value to book value and

er

dM t C

an

$15 38

$ 6 9

23

share Feb ua yevents,

2014

financial

issues,

with this material.

Most1Finance

in Action

BC and

(BCE practices can begin

35 08

2 43

64

of Montr

al (BMO) (URL)

59.23

38 discussion,

1 which

3

(FIA) boxes include atBank

least

one website

relevant to32the

will allow

Lo law (L)

1.10

27

1

for updating the events

outlined in the box. Furthermore,

when

companies

are discussed,

their stock market ticker

“symbol”

is

included

in

the

FIA

box

to

assist

in

O

t TC)

43 3

13 94

3 11 searches for

information on the company

EnCana EC

Small

references

Small Business Icons

So

Company business

n ncial report TSX

webs te www ts and

com examples are highlighted throughout

the text with an icon.

Meeting the Targets!

FINANCE IN ACTION

LO1

Valeant Corporation, formerly Biovail, is a Canadian pharmaceutical company. Between 2001 and 2004, according

to the OSC and the Securities and Exchange Commission

(SEC) of the United States, it manipulated its financial statements. It was suggested that Valeant

• Used outdated and misleading exchange rates in its

valuation

• Recorded phony sales at the end of financial quarters

• Moved research and development expenses off its

balance sheet to the pharmaceutical technologies

division

• Overstated the impact of a truck accident and product

loss

The overall impact was misleading to investors. Valeant settled out of court, paying a fine to the OSC. The

company has since bounced back to improved financial

results.

Q1 How has Valeant’s share price performed during the

last 12 months?

Q1 What are Valeant’s comments on these events and

charges?

valeant.com

Symbol: VRX

sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2008/lr20506.htm

tems such

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

xv

Examples and Tables For problem solving and its methodologies, we have employed

tables to illustrate the development of solutions. This is integrated with discussion of

the concepts that are illustrated through the “number‐crunching.” Problem solving is

integrated throughout the text material, as in Chapter 2 where an income statement is

developed over several pages.

The use of tables brings your attention to a problem‐solving methodology.

END-OF-CHAPTER MATERIAL

Practice makes perfect. Each chapter concludes with review and problem materials to

g

p

p

,

help students review and Ross

apply

over 90

cou what

d hedg they’ve

this r k atlearned

a probable throughout

ftert x cost f the

out chapter

120 00 pe yWell

r Whi

he was

making

this point, Ben

Gilbert

ve Al O

ive a co

percent of the problems are

new

or revised

from

theg 9th

edition.

he mat r al on h ging at the en of Chapt r and n Chapter 19 A l er k ew that he

Summary Each chapter ends

with a summary that ties the material back to the specific

f

f

chapter objectives presented

beginning

of the

chapter.

B at

for the

the discussion

was ove

Al Oliver

w s pr

a d onend

an a nu

basis a d

the only g that

in to t includes

e investor ame

in the form a

o capital

Review of Formulas At the

of every

chapter

formulas,

list of all

p

,

ti ly

, er

m

h

formulas used in that chapter

is

provided

for

easy

reviewing.

The

formulas

l ch”

ent

k d

lb

t

b ks

ht b

thi from

f all

Ben r spo perforated

ded

chapters are included on issue

the tearout

card that comes with the text.

,

y

y g

g

y

Discussion Questions andis Problems

The

material

by

e dur ng i s if

ee

be greater ris in

wh the

ch m ytext

me n is

he esupported

is a lower

ting onover

the issue.

of course, know

wha 10th

t at means

in ter to

s o reinforce

a higher

approximately 300 questionsr and

500You

problems

in this

edition,

and

y

b

test your understanding of the chapter. The problems are a very important part of the text,

p

p

and have been written with

careo to

consistent

chapter

material

as many

th be

other

items that Be with

Gilbe the

t brought

up He called

his you The

g ass problems

tant n

some h p.

for this edition have beenfor

revised,

while maintaining the extensive variety and the range of

a

difficulty from previous editions.

th

y

Spreadsheet Templates Several

(identified by an arrow) within the end‐of‐

l kely questions

for L land Industries?

. f the bonds of Leland Industries carried a requirement that perce

chapter material can be solved

using the Excel Templates available on Connect.

d

t

d g

t

y

ea

d

rc

t

have

comprehensive

problems

Comprehensive Problems Several

t

tchapters

m t

thi

?A u

10

i

t t that integrate

d several

From a st ic

ly dollars‐and‐cents

viewpoint

does problem.

the f oating‐

and require the application of

financial

concepts

into one

Assume the zero‐coupon rate bonds would be issued at a yield of 3/4 of

Mini Cases These are moree.intense

extensive problems that may involve several concepts

l

and cover material from more of

than

one

chapter,

often

discussion

a $ 000 bond?

How many

bondsinvolving

must be issued

to raise $20 m

MINI CASE

WARNER MOTOR OIL CO.

Gina Thomas was concerned about the effect that high interest expenses were having

on the bottom‐line reported profits of Warner Motor Oil Co. Since joining the company

three years ago as vice‐president of finance, she noticed that operating profits appeared

to be improving each year, but that earnings after interest and taxes were declining

because of high interest charges.

Because interest rates had finally started declining after a steady increase, she

thought it was time to consider the possibility of refunding a bond issue. As she

explained to her boss, Al Rosen, refunding meant calling in a bond that had been

issued at a high interest rate and replacing it with a new bond that was similar in most

respects, but carried a lower interest rate. Bond refunding was only feasible in a period

of declining interest rates. Al Rosen, who had been the CEO of the company for the last

seven years, understood the general concept, but he still had some questions.

xvi

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS

McGraw‐Hill Connect™ is a web‐based assignment and assessment platform that gives

students the means to better connect with their coursework, with their instructors, and

with the important concepts that they will need to know for success now and in the future.

With Connect, instructors can deliver assignments, quizzes, and tests online. Nearly

all the questions from the text are presented in an auto‐gradeable format and tied to the

text’s learning objectives. Instructors can edit existing questions and author entirely new

problems. Track individual student performance—by question, assignment, or in relation

to the class overall—with detailed grade reports. Integrate grade reports easily with

Learning Management Systems (LMS).

By choosing Connect, instructors are providing their students with a powerful tool

for improving academic performance and truly mastering course material. Connect

allows students to practise important skills at their own pace and on their own schedule.

Importantly, students’ assessment results and instructors’ feedback are all saved online—

so students can continually review their progress and plot their course to success.

Connect also provides 24/7 online access to an eBook—an online edition of the text—

to aid them in successfully completing their work, wherever and whenever they choose.

Connect material has been prepared by Ernest Kerst, Sheridan College.

KEY FEATURES

Simple Assignment Management

With Connect, creating assignments is easier than ever, so you can spend more time

teaching and less time managing.

• Create and deliver assignments easily with selectable end‐of‐chapter questions and

testbank material to assign online.

• Streamline lesson planning, student progress reporting, and assignment grading to

make classroom management more efficient than ever.

• Go paperless with the eBook and online submission and grading of student assignments.

Smart Grading

When it comes to studying, time is precious. Connect helps students learn more efficiently

by providing feedback and practice material when they need it, where they need it.

• Automatically score assignments, giving students immediate feedback on their work

and side‐by‐side comparisons with correct answers.

• Access and review each response; manually change grades or leave comments for

students to review.

• Reinforce classroom concepts with practice tests and instant quizzes.

Instructor Library

The Connect Instructor Library is your course creation hub. It provides all the critical

resources you’ll need to build your course, just how you want to teach it.

•

Assign eBook readings and draw from a rich collection of textbook‐specific assignments.

•

Access instructor resources:

Instructor’s Manual This manual, written by the authors, integrates the graphs, tables,

PowerPoint slides, and problems into a lecture format. Each chapter opens with a brief

overview of the chapter and a review of the key learning objectives. Then each chapter

is outlined in an annotated format to facilitate its use as an in‐class reference guide by

the instructor.

The manual includes detailed solutions to all problems and questions at the end of

the chapters. The solutions are presented in large type to facilitate their reproduction

as transparencies for use in the classroom.

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

xvii

•

•

Computerized Test Bank Software The test bank, prepared by Ernest Kerst, Sheridan

College, includes more than 1,500 multiple‐choice and true‐false questions, and

short‐answer questions written according to the revisions of the 10th edition. The

test bank is available in the EZ Test. McGraw‐Hill’s EZ Test Software is a user‐friendly

program for Windows that enables you to quickly create customized exams. You

can sort questions by format, edit existing questions or add new ones, and scramble

questions for multiple versions of the same test.

Microsoft® PowerPoint® Slide Presentations The PowerPoint package, prepared by

Michel Paquet, SAIT, contains relevant tables, figures, and illustrations from the text

material that you can customize for your lecture.

Image Bank

Excel Templates & Solutions These templates were prepared by Ernest Kerst,

Sheridan College. Selected problems are provided with Excel templates and are

marked with an arrow in the end‐of‐chapter problems.

View assignments and resources created for past sections.

Post your own resources for students to use.

INSTRUCTOR RESOURCES

eBook

Connect reinvents the textbook learning experience for the modern student. Every

Connect subject area is seamlessly integrated with Connect eBooks, which are designed to

keep students focused on the concepts key to their success.

• Provide students with a Connect eBook, allowing for anytime, anywhere access to the

textbook.

• Merge media, animation, and assessments with the text’s narrative to engage students

and improve learning and retention.

• Pinpoint and connect key concepts in a snap using the powerful eBook search engine.

• Manage notes, highlights, and bookmarks in one place for simple, comprehensive review.

No two students are alike. Why should their learning paths be? LearnSmart uses

revolutionary adaptive technology to build a learning experience unique to each student’s

individual needs. It starts by identifying the topics a student knows and does not know.

As the student progresses, LearnSmart adapts and adjusts the content based on his or

her individual strengths, weaknesses, and confidence, ensuring that every minute spent

studying with LearnSmart is the most efficient and productive study time possible.

As the first and only adaptive reading experience, SmartBook is changing the way students

read and learn. SmartBook creates a personalized reading experience by highlighting the

most important concepts a student needs to learn at that moment in time. As a student

engages with SmartBook, the reading experience continuously adapts by highlighting

content based on what each student knows and doesn’t know. This ensures that he or she

is focused on the content needed to close specific knowledge gaps, while it simultaneously

promotes long‐term learning.

New to the 10th Canadian edition of Block! Visualized data tailored to your needs as an

instructor make it possible to quickly confirm early signals of success, or identify early

warning signs regarding student performance or concept mastery—even while on the go.

xviii

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

SUPERIOR LEARNING SOLUTIONS AND SUPPORT

The McGraw‐Hill Ryerson team is ready to help you assess and integrate any of our

products, technology, and services into your course for optimal teaching and learning

performance. Whether it’s helping your students improve their grades, or putting your

entire course online, the McGraw‐Hill Ryerson team is here to help you do it. Contact

your Learning Solutions Consultant today to learn how to maximize all of McGraw‐Hill

Ryerson’s resources!

For more information on the latest technology and Learning Solutions offered by

McGraw‐Hill Ryerson and its partners, please visit us online: www.mheducation.ca/he/

solutions.

Solutions that make a difference.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to the following individuals, who have offered their thoughts and

insights to improve this text. We are impressed by the ongoing support for the text and the

willingness of so many to offer suggestions and advice. Thanks go out to all for the source

of stimulation. We hope we’ve been able to address most of the concerns raised, as we

believe that we continue to make the text more effective for our students. As always, we’ve

tried to balance competing thoughts and accommodate individual classroom styles. These

individuals include:

Raymond A. K. Cox, University of Northern

British Columbia

Michel Paquet, Southern Alberta Institute

of Technology

Mark Norton, Northern Alberta Institute of

Technology

David Roberts, Southern Alberta Institute

of Technology

Judith Palm, Vancouver Island University

David Grusko, Red River College

To those colleagues across the country whom we have visited over the years, thank you

for your continued support. We look forward to meeting with other instructors in the future.

Special thanks go to the individuals who over several editions have always been there to

help find an answer. Robert Short acts as a guide through the capital markets. Peter Nissen

simplifies the Income Tax Act and tax practices for our understanding. Pan Zhang and

Luigi Figliuzzi were of great assistance working on several chapters in a previous edition.

For this 10th edition there was wonderful help from Devika Short in the preparation and

review of several support documents.

Many individuals contributed in innumerable ways to earlier editions, and their efforts

live on in this edition. Thank you to H. Allan Conway for his groundwork in preparing the

first Canadian edition of this text. We would like to express our gratitude to Stanley B.

Block and Geoffrey A. Hirt for the work and care that they continue to put into the U.S.

editions. We also appreciate the latitude that they have allowed in adapting the book for

the Canadian environment and student.

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

xix

To our Senior Product Manager, Kimberley Veevers, our thanks for her commitment

to a text focused on the student. Kim’s efforts to keep us on course were appreciated.

As always, she is sensitive to concerns and desires in producing a first‐rate text, while

carefully considering the trends of the marketplace.

To our Product Developer, a sincere thanks. Erin Catto juggled with great skill our cut‐

and‐pastes, e‐files, and phone calls in putting together a workable manuscript with an eye

to our oversights and errors. She also persisted in keeping us on task.

To the marketing representatives, a special thanks for doing such a great job of keeping

in touch with the current and future users of this text. Call anytime!

Finally, a thanks to our students. We find finance fascinating because it changes every

day and it reflects the future. It is like you.

—J. Douglas Short

Michael A. Perretta

xx

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

PREFACE

The daily events of business news, the dynamics of the capital markets, and the deals that

change enterprises encompass the world of finance. The dynamics of recent history are

particularly startling. Too often, the finance discipline is considered challenging by students

because we make its concepts overly complicated. Although finance has unique language

and terms, it relies on some fairly basic, commonsensical ideas. Foundations of Financial

Management is committed to making finance accessible to you.

As always, this edition incorporates content and presentation revisions to make the text an

even better tool for providing you with the skills and confidence you’ll need to be an effective

financial manager. Concepts are explained in a clear and concise manner with numerous

“Finance in Action” boxes highlighting real-world examples and employing Internet resources

to reinforce and illustrate these concepts. The extensive and varied problem material helps to

reinforce financial concepts in more detail. The text is committed to presenting finance in an

enlightening, interesting, and exciting manner.

REINFORCING PREREQUISITE KNOWLEDGE

Employers of business graduates report that the most successful analysts, planners, and

executives have both ability and confidence in their financial skills. We couldn’t agree more.

One of the best ways to increase your ability in financial planning is to integrate knowledge

from prerequisite courses. Therefore, this text is designed to build on your knowledge from

basic courses in accounting and economics, with some statistics thrown in for good measure.

By applying tools learned in these courses, you can develop a conceptual and analytical

understanding of financial management.

For some of you, a bit of time has passed since you’ve completed your accounting

courses. Therefore, included in Chapter 2 is a basic review of financial statements based

on Accounting Standards for Private Enterprises (ASPE) and International Financial Reporting

Standards (IFRS) for public companies, finance terminology, and basic tax effects. With a

working knowledge of that chapter, you will have a more complete understanding of financial

statements, the impact of your decisions on financial results, and how financial statements

can serve you in making effective financial decisions. Furthermore, as you are about to begin

your career, you will be better prepared when called on to apply financial concepts.

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

xi

FLEXIBILITY

Foundations of Financial Management covers all core topics taught in a financial management

course. However, it is almost impossible to cover every topic included in this text in a single

course. This book has therefore been carefully crafted to ensure a flexibility that accommodates

different course syllabi and a variety of teaching approaches. We encourage instructors to use

an approach to the text that works best for them and for the student.

Financial management’s three basic concerns are the management of working capital,

the effective allocation of capital by means of the capital budgeting decision, and the

raising of long‐term capital with an appropriate capital structure. These topics are covered

in Parts 3, 4, and 5 of the text. An introduction to financial management in Part 1 and to

financial analysis and planning in Part 2 precede these central parts. A broader perspective

on finance is addressed in Part 6.

There is continual debate on the best method to present the time‐value‐of‐money

concepts. To allow for the range of opinion, formulas, tables, and calculator presentations

and solutions are available. Although this is sometimes cumbersome, an attempt has been

made to separate the different approaches with colour shading. Choose the method that

works best for you.

NEW FOR THE 10TH EDITION

Throughout the 10th edition there have been timely updates to the “Finance in Action”

(FIA) boxes, figures, and tables as finance continually changes, often in a dramatic

fashion. With a mix of familiar examples from the markets to illustrate financial concepts,

new examples have been added as appropriate. Instructors who have used this text before

will find it familiar, and yet significant improvements have also been made in both the

content in the book and the supplements that accompany it.

•

Updated content on the IFRS and its impact on finance in Canada is now included.

•

Lessons learned from the 2008 financial crisis have been incorporated.

•

Streamlined discussions by casting these in bullet‐point form when appropriate. This

has been a delicate process. Nevertheless, the pay‐off for students is that it allows them

to focus attention more acutely on key ideas.

•

All FIA boxes have been re‐examined for appropriateness and have been updated as

required. Web links have been updated to help students explore further research on

these topics.

•

Problem sets have been extensively changed from the 9th edition. Also, new problems

have been added, as requested by reviewers.

In Part 1, the Introduction, we lay the groundwork for the dynamic nature of finance,

including a discussion of the $19 billion purchase of WhatsApp by Facebook, as the

technology world continues to amaze us with it’s market valuations.

In Part 2, Financial Analysis and Planning, we reflect the changes in accounting and tax

rules, as well as financial presentation.

In Part 3, Working Capital and the Financing Decision, we note the changes in working capital

positions due to the cash hoarding of firms, reflecting their conservatism, resulting from the

most severe financial recession since the 1930s. We can tie this into the healthy dividends

and share repurchases discussed in Chapter 18. This conservatism and risk aversion is seen

in the significant drop in short‐term financing by way of commercial paper and asset‐backed

securities. The implications of the low interest rate environment are also noted.

In Part 4, the Capital Budgeting Process, we add where appropriate screen shots of

spreadsheets to illustrate calculations. With bond yields we note the risk to prices from

any upward yield movements. In the FIAs we highlight the drop in R&D spending by

BlackBerry, replaced as the largest R&D spender by Bombardier. The Northern Gateway

xii

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

pipeline as a capital budgeting strategy is highlighted. Adjustments have been made for the

impact of the lower tax rate environment and its impact on capital budgeting decisions.

WestJet, now an established airline, has been successful in a very risky business and has

now been joined by Porter Airlines.

In Part 5, Long Term Financing, the capital markets chapter is extensively revised to show

the significant relative increase in corporate borrowing, the banks’ continuing domination

in financial intermediation although activity is tempered by pension and mutual funds,

and ongoing globalization controlled to some extent by local regulatory concerns. Income

trusts and asset‐backed securities have retreated in influence, and the FIA in Chapter 16,

“Know What You Are Buying,” points out how we sometimes forget to examine the assets

behind the financial security. Alibaba, the Chinese online retail facilitator is highlighted as

it was poised to become the largest IPO in history, also demonstrating the influence of the

Chinese retail market. The shifting markets, from bond rates and tax changes (dividend

tax credit) and Microsoft entering the stage of its lifecycle where growth has slowed

and dividends replaced capital gains are all examined and noted. The continuing use of

convertible securities by less credit worthy firms is seen in the derivatives chapter.

In Part 6, the mergers and acquisitions chapter notes the presence of sovereign

governments, such as China and Malaysia, as players particularly in the energy sector,

and the reorganizations taking place in the retail sector (Hudson’s Bay/Saks, Loblaw). The

international financial management chapter continues to emphasis the significance the

global market plays for Canada and the volatility of the exchange markets.

ETHICAL BEHAVIOUR AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

The approach is to lay out in Chapter 1 an ethical framework from which financial

management practices can be examined. The agency conflict related to good corporate

governance can be examined in the context of establishing the goal of the firm. Numerous

FIA boxes raise issues for discussion and research by students.

The discussion in Chapter 1 begins with socially desirable actions from an example of

a responsible Canadian corporation.

A good ethical practice framework focuses first on fairness, tying into the rules and

regulatory environment within which the firm operates and the changes that take place. It

then identifies honesty as requiring timely, relevant, and reliable financial reporting. (This

framework can be used to discuss several FIA topics.)

Good corporate governance practices and recent changes are tied into several

chapters and to resources that include academic research and the Canadian Coalition for

Good Governance.

The discussions on market efficiency and securities regulation in Chapter 14 and what

makes for good regulation should be tied into discussions of good corporate governance.

FIAS

Chapter 1

“Are Executive Salaries Fair?”

Chapter 2

“Apparently Earnings Are Flexible”; “Meeting the Targets!”

Chapter 3

“Taking a Big Bath”

Chapter 7

“Why Are Firms Holding Such High Cash Balances”

Chapter 10

“Diamonds, Nickel, Gold, or BlackBerry—for Value?”

Chapter 11

“Canadian Utilities, Return on Common Equity, and Cost of Capital”

Chapter 12

“Strategies: Right or Wrong?”

Chapter 14

“Listing Requirements”; ”Do Financial Statements Tell the Truth”

Chapter 15

“To Market! To Market!”

Chapter 16

“The Prospectus”; “Before the Fall”

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

xiii

Chapter 17

“A Claim to Income and a Right to Vote?”; “An Expensive Pill to Swallow”

Chapter 18

“Pay Those Dividends!”

Chapter 19

“The Derivatives Market”

Chapter 21

“Whiskey Is Risky!”

RISK

Risk is identified in Chapter 1 as one of the key concepts of finance (sometimes neglected)

in determining value. Consideration of risk is interwoven throughout the text with

discussion and FIA boxes. The general concept of volatility is illustrated, to be examined

more extensively, particularly in Chapter 13 through statistical measures. Chapter 1

suggests the early warning signs of the 2008 market downturn found in the Treasury‐bill–

commercial paper yield spread.

In Chapter 2 rule‐of‐thumb risk measures of price‐earnings and market to book ratios are

examined from a financial statement perspective. Additionally, tax rule changes identify risk.

In Chapter 3 ratio analysis is seen in the context of gauging pressure points increasing

risk within the firm, while Chapter 4 explores the risks and sensitivities of forecasting.

Chapter 5 is the first full chapter exploring risk from the leverage perspective, identifying

business, operating, and financial risk.

Hedging across the balance sheet is established in the context of risk reduction in

Chapter 6, while volatility is viewed through interest rate changes. Chapter 8 assesses the

credit crunch phenomenon that reappears time and time again.

In Chapter 10 there is the risk premium discussion on required rates of returns (yields),

with Chapter 11 exploring risk within the overall concept of the cost of capital. Additionally

the CAPM risk return model is introduced. It is within Chapter 13 that three significant

questions related to risk are identified. The distinction between total risk (coefficient of

variation) and systematic risk (beta) is highlighted. Risk reduction through the portfolio

effect is constructed statistically with important conclusions and follow‐up problems.

In Chapter 19 risk reduction from derivatives is illustrated, and is tied back to leverage in

Chapter 5 and hedging in Chapter 6. Chapter 21 examines risk reduction through international

diversification, and the volatility of the Canadian dollar in 2007–2014 (Figure 21–9)

is illustrated.

FIAS

xiv

Chapter 1

“The Foundations”; “The Markets Reflect Value, Yields, and Risk”

Chapter 2

“Apparently Earnings Are Flexible”; “Corporate Tax Rules”

Chapter 3

“Applying DuPont Analysis on the Rails”; “Taking a Big Bath”

Chapter 4

“Oil Prices! How about a Forecast?”; “Operational Cash Flow Exceeds

Earnings and Allows Capital Expenditures”

Chapter 5

“Big Leverage! Big Losses! Big Gains! Insolvency! Rebirth!”; “Leverage of

Twenty Times Equity”

Chapter 7

“Treasury Bills, Not ABCP, for Liquidity and Safety”, “Why Are Firms Holding

Such High Cash Balances”

Chapter 8

“CN Rail Maintains a Negative Trade Credit Position”; “Liquid Assets as

Collateral: It Goes Down Well”

Chapter 10

“Market Yields and Market Values”; “The Ups and Downs of Bond Prices”

Chapter 11

“Debt Costs around the Globe”

Chapter 13

“Financial Crisis 2008, U.S. Government Default 2011, Crimea Conflict 2014:

How Do You Get a Risk Reading?”

Chapter 20

“Are Diversified Firms Winners or Losers?”; “Refocusing Strategies”

Chapter 21

“Whiskey Is Risky!”; “Rating the Countries”

Preface

www.tex-cetera.com

PEDAGOGY

To provide guidance and insights throughout the text, we incorporate a number of proven

pedagogical aids, including:

Learning Objectives At the beginning of each chapter, learning objectives will help

A R T learning

2

focus Pyour

as you proceed through the material. The summary of each chapter

responds

objectives

F I NtoAeach

N C IofAthese

A Nobjectives.

A LY S I Learning

AND P

L A N N are

N Gtagged in‐chapter and with

end‐of‐chapter questions.

Review of Accounting

CHAPTER 3

Financial Analysis

CHAPTER 4

Financial Forecasting

CHAPTER 5

Operating and Financial Leverage

REVIEW OF

ACCOUNTING

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LO1

Prepare and analyze the four basic

financial statements.

LO2

Examine the limitations of the income

statement as a measure of a firm’s

profitability.

Calculators When the use of a calculator is illustrated, a calculator icon appears in the

margin. Appendix E demonstrates the use of the three most commonly used business

calculators, with the illustrations in the text tending to conform to the Sharp calculator.

Chapter 9 demonstrates the use of a calculator with time lines, and the use of tables (as

an option). The formulas for present value analysis, which are the basis for calculators,

tables, or computers, have been included. Answers computed with the calculator will be

V lues are s ated on historic o origi al cost as for pr v t compan es ut

more accurate than those

provided

by

the tables,

due to the roundinga of the table factors.

b

s

F

A financial calculator tutorial

usingmore

thethan

TI BA

canorbe

found

Connect.

considerably

thei II

o Plus

i inal cost

may

requireon

many

times the

“Finance in Action” Boxes These popular boxes address topics related to the chapter

subject matter and deal with the difficulties and opportunities in the financial markets.

Ta b e 2– 5

Ma require

ket Value Internet

Book Valu searches

Ratio of Market

Questions

appropriate to the topic often

for Value

background

p

C mp

information

for Fhelp

in

analysis.

Rewarding

discussions

of

current

and

historical

value to book value and

er

dM t C

an

$15 38

$ 6 9

23

share Feb ua yevents,

2014

financial

issues,

with this material.

Most1Finance

in Action

BC and

(BCE practices can begin

35 08

2 43

64

of Montr

al (BMO) (URL)

59.23

38 discussion,

1 which

3

(FIA) boxes include atBank

least

one website

relevant to32the

will allow

Lo law (L)

1.10

27

1

for updating the events

outlined in the box. Furthermore,

when

companies

are discussed,

their stock market ticker

“symbol”

is

included

in

the

FIA

box

to

assist

in

O

t TC)

43 3

13 94

3 11 searches for

information on the company

EnCana EC

Small

references

Small Business Icons

So

Company business

n ncial report TSX

webs te www ts and

com examples are highlighted throughout

the text with an icon.

Meeting the Targets!

FINANCE IN ACTION