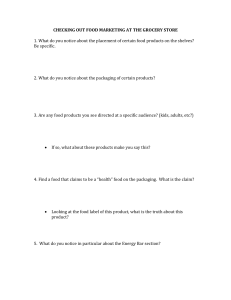

Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Cleaner Production journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jclepro A consumer definition of eco-friendly packaging Anh Thu Nguyen a, *, Lukas Parker b, Linda Brennan b, Simon Lockrey c a School of Business and Management, RMIT University Vietnam, Viet Nam School of Media and Communication, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia c School of Design, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia b a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Received 12 April 2019 Received in revised form 16 December 2019 Accepted 18 December 2019 Available online 18 December 2019 Consumers are increasingly concerned about the environmental consequences of packaging. Businesses are under pressure not only from consumers but also from governments to use eco-friendly packaging for their products. However, what consumers perceive to be eco-friendly packaging is still unclear, especially in emerging markets. This study examines consumer perceptions of eco-friendly packaging in the context of packaged food products of Vietnam. The study involved a series of six focus group discussions conducted with a diverse range of consumers. The focus of the discussion was consumer perceptions of eco-friendly packaging, particularly whether or not consumers would adjust their purchase behaviours to be more environmentally friendly. The data analysis procedure was undertaken using inductive manual coding principles associated with interpretivist research. The results indicate that consumer perceptions of eco-friendly packaging can be categorised along three key dimensions: packaging materials, manufacturing technology and market appeal. While consumers have diverse perceptions of eco-friendly packaging, their knowledge is limited and more related to packaging materials (such as biodegradability and recyclability), and market appeal (such as attractive graphic design and good price). Consumers show little knowledge about manufacturing technologies but still desire an ecofriendly manufacturing process. Results also suggest that a consumer-defined eco-friendly package for food products should be visually appealing while satisfying consumers’ environmental expectations relating to packaging materials and manufacturing process. We therefore propose a consumer-initiated development of eco-friendly packaging that can be applied for sustainable packaging strategies. Published by Elsevier Ltd. Handling Editor: Yutao Wang Keywords: Eco-friendly packaging Packaging materials Manufacturing technology Market appeal Packaged food products 1. Introduction This paper contributes deeper understanding to the growing body of knowledge of consumer behaviour towards eco-friendly packaging in a unique socio-cultural context: Vietnam. Globally, the use of plastic packaging for consumer products has steadily increased. In 2012, the global plastic production volume was 288 million tons (Parker, 2015). In 2015, this figure increased to 448 million tons, 40 per cent of which was single-use plastic (Parker, 2018), mostly applied for food packaging (Ritschel, 2018). Each year, it is estimated that 90 million tons of plastic waste enters the world’s oceans from coastal regions (Howard et al., 2018). Plastic waste can damage the ecosystem of the oceans. There is evidence that plastic may cause malnutrition or starvation for fish and eventually lead to plastic ingestion by humans on a large scale. In * Corresponding author. E-mail address: thu.nguyen@rmit.edu.vn (A.T. Nguyen). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119792 0959-6526/Published by Elsevier Ltd. 2016, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) gave a warning of increased risks to human health from micro-plastic pollution in commercial fish (Trowsdale et al., 2017). Additionally, the European Parliament has approved the ban of single-use plastics, effective from 2021 across European Union (EU) member countries (Rankin, 2019). Several governments around the world also pioneer in banning single-use plastics, including the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, France, Australia, Taiwan, Kenya and Zimbabwe (Calderwood, 2018). However, plastic can be a fit-for-purpose and efficient option to deliver goods to consumers (Verghese et al., 2015). Plastic is often used as a cost-effective solution by manufacturers to deliver more products to the market with less packaging materials. Hence, a paradox exists between the impacts and benefits of packaging choices, with industry heads pushing to increase plastic use while governments are increasingly banning or restricting single-use plastics. The acceptability or otherwise of these opposing motivations to consumers is still not known. Although there are emergent studies that aim to address this (Dilkes-Hoffman et al., 2019; Herbes et al., 2018), these are 2 A.T. Nguyen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 conducted in a Westernised consumption context. Given this research context, this study elucidates Vietnamese consumers’ perceptions about eco-friendly packaging in a product category that contributes substantially to packaging waste (Instant Noodles). 1.1. Research context Vietnam is a rapidly industrialising and increasingly a consumerist society with a mounting plastic waste problem. Disposal of packaging has become a major environmental challenge in the country. In 2013, Vietnam’s largest city, Ho Chi Minh City, used approximately 120 tons of packaging of all types each day, of which 72 tons was plastic (Vietnam News, 2013). In 2019, it is estimated that about 80 tons of plastic waste and bags are thrown away every day in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City combined (Dan Tri News, 2019). A report from Ocean Conservancy claims that Vietnam is among five countries e China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam e which dump as much as 60 per cent of global plastic waste into the world’s seas (Winn, 2016). As plastic decomposes slowly, related adverse impacts on the environment will continue for not only Vietnam but also the entire planet in the long term. The role of consumers in decreasing packaging waste is a central one. However, nothing is yet known about consumers’ attitudes towards or perceptions of eco-friendly packaging options in Vietnam. Accordingly, this study contributes novel information regarding consumers in a rapidly growing economy, and within a unique cultural context. Global consumers are increasingly concerned about the negative environmental impacts of packaging waste. In previous studies, international researchers have noted growing consumer concern about packaging and its effects on the environment (e.g., Fernqvist et al., 2015; Lewis and Stanley, 2012; Lindh et al., 2016a; Magnier , 2015; Mishra et al., 2017; Prakash and Pathak, 2017; and Crie Rokka and Uusitalo, 2008; Taylor and Villas-Boas, 2016). A decade ago, packaging was rated as the issue of greatest environmental and ethical concern of UK consumers (Lewis and Stanley, 2012). Several studies have investigated consumer choice in terms of eco-friendly packaging in developed market contexts (e.g., Barber, 2010; Koenig-Lewis et al., 2014; Laforet, 2011; Rokka and Uusitalo, 2008; Steenis et al., 2017, 2018). Koenig-Lewis et al. (2014) explored consumers’ evaluations of ecological or eco-friendly packaging and found that purchase intention is significantly affected by consumers’ concerns for the environment. Similarly, Rokka and Uusitalo (2008) discovered that thirty per cent of surveyed Swedish consumers considered green or eco-friendly packaging as the most important criterion when buying a beverage product. A Deloitte study in the United States of America (USA) (2018) also found that consumers are demanding eco-friendly products as they become more aware of environmental issues. However, to date, there is limited research from rapidly developing economies such as those in Southeast Asia. This study contributes new evidence in relation to developing, non-Western settings, therefore deepening the understanding of eco-friendly packaging in a globalising manufacturing context. At this stage, there are no studies that examine eco-friendly packaging in Vietnam although there are some in India (Biswas and Roy, 2015; Mishra et al., 2017; Prakash et al., 2019; Prakash and Pathak, 2017) and China (Hao et al., 2019). In the Vietnamese context, citizens are increasingly concerned about public littering and packaging disposal because most urban areas are visibly polluted, commonly with discarded plastic packaging (De Koning et al., 2015; Vietnam News, 2018). To arrive at a more accurate understanding of consumer behaviour towards packaging, consumer research could be focused more on studying actual product choices rather than general environmental attitudes (Rokka and Uusitalo, 2008) and therefore move towards understanding actual behaviours within their decision-making contexts (Lockrey et al., 2018). However, at this stage, a strong theoretical understanding of consumers’ appreciation of eco-friendly packaging is still lacking (Prakash and Pathak, 2017). The present study examines consumer perceptions of eco-friendly packaging within a previously unexamined setting. 1.2. The concept of eco-friendly packaging Eco-friendly packaging has great potential to contribute to € m et al., sustainable development (Lindh et al., 2016a; Wikstro 2018). Although packaging is a social and political concern, there has been only limited research into consumer perceptions of ecofriendly packaging. Indeed, eco-friendly packaging has never been a clear concept in the consumer behaviour literature (Magnier , 2015). Furthermore, researchers have used different terms and Crie to indicate eco-friendly packaging, such as environmentally friendly packaging, eco-packaging, ecological packaging, green packaging, sustainable packaging, eco-design, design for the environment, and environmentally conscious design (Boks and Stevels, , 2015), causing 2007; Koenig-Lewis et al., 2014; Magnier and Crie confusion when undertaking research. In practice, eco-friendly packaging is often referred to as sustainable packaging. Many initiatives have been introduced to promote the concept of sustainable packaging in industry. A widely accepted definition of sustainable packaging is given by the Sustainable Packaging Coalition® (SPC) (2011): Sustainable packaging is beneficial, safe and healthy for individuals and communities throughout its life cycle; meets market criteria for performance and cost; is sourced, manufactured, transported, and recycled using renewable energy; maximises the use of renewable or recycled source materials; is manufactured using clean production technologies and best practices; is made from materials healthy in all probable end of life scenarios; is physically designed to optimise materials and energy; and is effectively recovered and utilised in biological and/or industrial cradle-to-cradle cycles. The SPC definition embraces functional as well as environmental and technological dimensions of sustainable packaging and € m et al., 2014, is well recognised (Verghese et al., 2015; Wikstro 2018). Sustainable packaging is expected to protect the product and communicate its features, embracing material reuse and waste reduction throughout a packaging life cycle from production to consumption, disposal and after disposal (Dominic et al., 2015). With regard to packaged food products, packaging fulfils many purposes. The primary purpose of packaging is to protect products € m et al., 2014). Packaging is also a way to communicate to (Wikstro consumers (Rundh, 2005; Silayoi and Speece, 2007). Packaging can influence how consumers evaluate products prior to purchase (Becker et al., 2011). Moreover, packaging can generate emotional responses (Liao et al., 2015) and motivate consumers to purchase a product (Murray and Delahunty, 2000). However, these functions always come with both monetary and environmental costs (Simms and Trott, 2010). In food packaging, a majority of materials used are slowly degradable petroleum-based plastic polymer materials, which impart serious problems to the environment (Kirwan et al., 2011) but which may be abundantly available to consumers. To manufacturers and marketers of packaged food products, consumers’ expectations in relation to packaging are important in defining the overall acceptability and marketability of the product. There are criteria consumers consider when making food product choices related to packaging. Health-conscious consumers pay attention to label information (Coulson, 2000) whereas others A.T. Nguyen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 place priority on eco-friendly characteristics of the package (Rokka and Uusitalo, 2008). Furthermore, consumers may believe that packaging is wasteful, and may also consider the product negatively as they throw packaging away (Roper and Parker, 2013). Therefore, what consumers perceive to be eco-friendly packaging is an important question to address before businesses can successfully implement eco-friendly packaging strategies in order to remain sustainably competitive. Considerable research has been undertaken into consumer environmental considerations in terms of eco-friendly packaging (e.g., Barber, 2010; Davies and Gutsche, 2016; Koenig-Lewis et al., 2014; Laforet, 2011; Rokka and Uusitalo, 2008; Van Birgelen et al., 2009). For instance, environmental concern is found to be positively associated with purchase intention for eco-friendly packaging (Magnier and Schoormans, 2015; Martinho et al., 2015; Prakash and Pathak, 2017), whilst price may affect consumer intention to buy eco-friendly packaging (Martinho et al., 2015; til, 2019). While there appears to be a growing Pícha and Navra interest in consumer behavioural responses to eco-friendly packaging, there are not many studies reported on what consumers perceive to be eco-friendly packaging. Some studies have been directed at consumer perceptions towards eco-friendly packaging, (2015); such as Koenig-Lewis et al. (2014); Magnier and Crie Magnier and Schoormans (2015). These previous studies mostly focus on developed markets. Knowledge of what consumers in emerging markets perceive to be eco-friendly packaging is still lacking. This should be addressed as economic growth in emerging markets rapidly increases packaging waste into the environment (Engel et al., 2016). On the other hand, several researchers have introduced the concept of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), taking into account the packaging manufacturing process as well as food packaging, transport and disposal stages (e.g., Bertolini et al., 2016; Grant et al.,2015; Verghese et al., 2015). However, the question remains whether consumers ever think through the packaging life cycle process when it comes to buying packaged products. The main aim of this research is therefore to address this deficiency. Knowledge of consumers’ perceptions towards eco-friendly packaging for food products will provide useful input for manufacturers and marketers designing and specifying packaging. As shown in Section 1.1, in addition to not comprehending consumer perceptions, existing studies are heavily weighted to developed markets. Vietnam, an emerging market, has had recent rapid growth in consumption of packaged foods. Urbanisation and busier lifestyles lead Vietnamese consumers to make more purchases for convenience (Euromonitor, 2017). Packaged food product categories are expected to grow as modern lifestyle trends increase demand for convenience foods. Therefore, the food sector provides a novel context in which to examine consumer perceptions of ecofriendly packaging in Vietnam. Our study explores Vietnamese consumers’ perceptions of packaging for a common fast-moving consumer good, the Instant Noodle (IN) product category. This is because IN is a very frequently bought packaged food product in Vietnam. IN buying decisions are made on a daily basis for many consumers because they are relatively cheap and convenient. Vietnamese people consume 55 IN packets per capita per year, the second highest average personal consumption in the world after China (World Instant Noodles Association, 2018). In terms of size, Vietnam’s IN market had a value of 27 trillion VND (1.19 billion USD) in 2017 and was expected to gain steadily increasing consumption volumes (Vietnam Investment Review, 2017). This indicates that INs maintain strong growth, which may be attributed to low price and strong demand of a large young population for whom convenience is important (Euromonitor, 2017). As a consequence, Vietnamese consumers are regularly exposed to the various packaging types available for the 3 IN product category. This study seeks to understand Vietnamese consumers’ perceptions of eco-friendly packaging for a common fast-moving consumer good by addressing the following research questions (RQs): RQ1: What are consumer expectations for food packaging to be considered eco-friendly? RQ2: What dimensions of eco-friendly packaging are important to consumers when it comes to purchase behaviour? 2. Material and methods In this study, a phenomenological approach was employed, to gain an appreciation of individuals’ experiences through the consciousness of the experiencer (Giorgi, 2009). This approach has been widely used in sustainable consumption research (Davies and , 2015; Ritch, 2015). PhenomenoGutsche, 2016; Magnier and Crie logical approaches can gain insights into the actuality of phenomena, deepen understanding and provide rich authentic empirical data (Denzin, 2019). Phenomenology follows an interpretivist research tradition whereby research is conducted in naturalistic settings (Creswell, 2009). Focus groups were used to obtain data from research participants with deep probing to assist them in making sense of their perspectives (Brinkmann, 2014; Guest et al., 2017). Focus groups encourage free flowing discussions among small groups of participants and facilitate the sharing of perceptions in an open and tolerant environment (Creswell, 2009). Moreover, the subject of eco-friendly packaging is not individually sensitive, allowing participants to freely share their own perspectives and experiences (Saunders et al., 2012). When conducting the focus groups, we used open-ended questions to encourage participants to share opinions. Probing questions are useful to encourage participants to express more detail (Strang et al., 2015). Hence, the focus group moderator used several probing questions to identify where individuals might have different experiences and perceptions of eco-friendly packaging so as to encourage elaboration. We conducted six focus group interviews with a total of 36 participants. No new viewpoints were raised after four focus groups, indicating saturation in data collection (Mason, 2010). We used purposive sampling because this type of sampling seeks relevant information from knowledgeable participants for the research’s purposes (Elo et al., 2014). Participants were aged from 20 to 55 years and had purchased INs within the last 3 months at the time of the focus group interviews. Participants were recruited from a consumer panel of a commercial market research provider and drawn from a cross section of Vietnamese demographic segments. Participants were given a nominal incentive for their participation. Ethical clearance was provided by the institutional ethics committee. The focus groups were arranged in relevant age groups so that participants would be comfortable to share experiences and express their opinion with their age peers. Each focus group had six participants. Three focus groups were conducted in Ho Chi Minh City and three in Hanoi. These sites were chosen because they are the first-tier largest consumer markets of INs (Vietnam Investment Review, 2017). The study was limited to major cities in Vietnam. Rural and regional areas were not included. Table 1 summarises participants’ profiles. Participants came from diverse occupational backgrounds, such as office workers, students, homemakers, traders, doctors, and the self-employed. There were more female participants (58.5 per cent), reflecting a greater female influence in purchasing household products 4 A.T. Nguyen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 Table 1 Participant profile. Focus group name (purposive target) Occupation Age range Mean age Gender split (f:m) Group 1. Middle-aged 1 Ho Chi Minh City Group 2. Young adults 1 Ho Chi Minh City Group 3. Young adults 2 Ho Chi Minh City Group 4. Middle-aged 2 Hanoi Group 5. Young adults 3 Hanoi Group 6. Young adults 4 Hanoi Trader (2), Tailor (2), Homemaker (2) 36e45 40 6:0 30.5 3:3 23 2:4 46e54 26e30 20e25 49 27.5 23 6:0 4:2 2:4 20e54 32 23:13 Combined Security staff (1), Shop owner (1), Office worker (1), Homemaker (1), Customer service staff (1), 26e35 Accountant (1) College student (4), Accountant (1), Information Technology (IT) technician (1) 20e25 Office worker (1), Homemaker (2), Fashion trader (1), Craftsperson (1), Doctor (1) Office workers (3), Sales staff (1), Accountant (1), Homemaker (1) Fashion trader, Mobile phone sales staff, Electric biker trader, Office worker, Bank clerk, Accountant e N ¼ 36. (Nielsen, 2016). A majority of participants (66.6 per cent) were aged between 21 and 35 years old, with a mean age of 32. This reflects Vietnam’s relatively young population, where the median age is 31 (Central Intelligence Agency US, 2018). All focus groups were conducted in Vietnamese and the transcripts were translated into English by a professional translator. In order to decrease the potential for bias, the documents were backwards-translated into Vietnamese by a bilingual researcher. Both versions were then double checked by another bilingual researcher to ensure equivalence in the meaning (Brennan et al., 2015a). As the objective of our study is to obtain insights into the experiences of the research participants in their own words, in the data analysis, we used inductive manual coding principles associated with interpretivist research as suggested by Basit (2003). Fig. 1 illustrates the data analysis procedures. Qualitative data were systematically analysed in order to “understand and interpret the meanings and experiences of the informants” (Spiggle, 1994, p. 492), using the qualitative analysis process described by Creswell (2009). Themes were constructed using an iterative process of data analysis and interpretation (Clarke and Braun, 2014). The main themes extracted and interpreted were based on Boks and Stevels (2007) work, which identified three different categories of eco-friendliness characteristics of eco-friendly packaging: governmental, scientific and consumer. The assignment of data to constructed themes was undertaken by multiple researchers independently. Where disagreement occurred, discussions were facilitated to ensure agreement (Spiggle, 1994). In the data analysis, focus was given to the consumer category, which addresses consumers’ perceptions of the eco-friendliness of packaging and their expectations of eco-friendly packaging. In the data analysis process, transcripts were analysed to identify key themes using the key-words-in-context method (Creswell, 2009). Firstly a list of themes emerged with 22 concepts labelled as items. We reviewed each of the items carefully by re-examining the context in which participants expressed their perceptions of ecofriendly packaging to identify themes. Next, we thoroughly reviewed the codes and coded data to identify similarity and overlap (i.e., patterns of similar semantic meanings) among items. In case of overlap (i.e., items with similar semantic meanings), we removed overlapping items in order to reach a refined list of distinct items relating to constructed themes. In total, ten overlapping items were removed to create a refined list of twelve discrete items or topics. The twelve topics that emerged from the analysis were categorised into three main themes/dimensions: packaging materials, manufacturing technology and market appeal. This classification of eco-friendly packaging dimensions is considered as new, compared to prior studies such as Lindh et al. (2016a); Magnier and Crie (2015); Scott and Vigar-Ellis (2014). For example, Magnier and (2015) have identified two dimensions of eco-friendly packCrie aging in terms of perceived consumer benefits and perceived consumer costs. Scott and Vigar-Ellis (2014) have focussed more on how consumers interpreted labels, logos and material cues to assess if a package is or is not eco-friendly. Alternatively, Lindh et al. (2016a) have explored consumer perceptions of packaging for organic food products with regard to three themes e perceived packaging functions and materials, perceived environmentally sustainable packaging, and perceived importance of environmentally sustainable packaging. In our study, content analysis identified and categorised consumer perceptions of eco-friendly packaging into three key dimensions, which reflect a holistic approach in gaining a practical understanding of eco-friendly packaging from a consumer perspective. 3. Results and discussion Fig. 1. Data analysis procedures (Adapted from Creswell, 2009). The twelve topics emerging from the analysis were grouped under three main themes, namely, (1) packaging materials, i.e. characteristics of materials used to manufacture eco-friendly packaging, (2) manufacturing technology, i.e. characteristics of the eco-friendly package manufacturing process and (3) market A.T. Nguyen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 appeal, i.e. characteristics related to how eco-friendly packaging can appeal to consumers. The themes were then labelled as dimensions of eco-friendly packaging. Table 2 illustrates how the three themes were interpreted from the twelve items/topics that were identified and extracted from the coding process. The following sections discuss the three main dimensions and the related important attributes of eco-friendly packaging in consumer perceptions. 3.1. Packaging materials The most prominent dimension of eco-friendly packaging from a consumer perspective relates to packaging materials. In the focus groups, participants associated eco-friendly packaging with their expectations for packaging materials. Most were aware of ecofriendly packaging and stated that eco-friendly packaging was not as abundantly available in the market as they expected, despite the focus of media attention on plastic packaging and plastic waste. This was demonstrated in comments such as: I know about eco-friendly packaging from media. Sadly, there are not many eco-friendly packages in the market. (Female, sales staff) Participants also described eco-friendly packaging as non-toxic, easily decomposed at disposal, and best if biodegradable. These characteristics partly form a consumer definition of an eco-friendly package: An eco-friendly package does not pollute the environment, can be easily treated after use and is biodegradable. (Female, craftsperson) Eco-friendly packaging should be safe and non-toxic to humans. (Female, trader) These consumer views are consistent with Lindh et al. (2016b) who found that sustainable packaging development starts with packaging materials. Consumers in our study evaluated packaging materials when shopping and assessed whether a package was ecofriendly based on material cues. Prior studies have also indicated that consumers strongly rely on material cues to form judgements on packaging eco-friendliness (Lindh et al., 2016a; Magnier and , 2015). Crie Recyclability was another criterion participants perceived as important to eco-friendly packaging. Many focus group participants stated that recyclability made packaging less harmful to the environment because this attribute helped reduce packaging waste. This is consistent with Young’s (2008) finding that consumers across developed and developing countries (the UK, the USA, Germany and China) associate eco-friendly packaging mostly with 5 recycling. Participants suggested that materials in eco-friendly packaging should be able to be reused as well as recycled. Reusability can be in two ways: some materials are reused in the home in their entirety as packages, and parts of the packaging can also be developed for a second use (Lindh et al., 2016b). Participants assumed that ecofriendly packaging must be reused for another purpose, such as reproduction or construction. One participant gave a short definition of eco-friendly packaging as follows: First, eco-friendly packaging must be biodegradable. Second, it must be reusable. Third, it must not contain toxic substances. (Female, bank clerk) The idea that packaging can be reduced, reused or recycled is not new and the responses of participants in this study echo studies undertaken in other parts of the world. For example, Lewis and Stanley’s (2012) study in the UK revealed that consumer perceptions of eco-friendly packaging reflect packaging disposal issues, and hence consumers desire packaging with the characteristics of biodegradability, recyclability and reusability. Similarly, Magnier (2015) found that most consumers associate eco-friendly and Crie packaging with perceived recyclability and biodegradability. Scott and Vigar-Ellis (2014) also found that for South African consumers, the most commonly associated benefits with eco-friendly packaging are recyclability and reusability. Thus, it is reassuring that Vietnam, despite being a rapidly developing country, has a similar attitude towards eco-friendly packaging. With regard to packaging materials, many participants cited paper as the most eco-friendly material, for example: First thing comes to my mind about eco-friendly packaging is that it is made from paper. (Male, electric bike trader). No doubt, the most eco-friendly packaging material must be paper. (Female, office worker). Participants considered paper as easily decomposable, compared to other types of packaging materials. To their knowledge, paper might cause fewer negative environmental impacts, such as: I believe paper is most eco-friendly because it can decompose itself. (Female, accountant) To me, paper packaging is the most eco-friendly because it is easily decomposed, leaving less negative impact on the environment. (Female, office worker) Consumers’ perceptions of paper as the most eco-friendly Table 2 Key dimensions of eco-friendly packaging. Item/topic Theme/dimension Biodegradable Non-toxic Easily decomposed Reusable Recyclable Paper-based Production causing no harm to the environment Natural and organic sources of materials used in production New and advanced technology for production Good price Visually attractive graphic design Protective performance Packaging Material Packaging Material Packaging Material Packaging Material Packaging Material Packaging Material Manufacturing technology Manufacturing technology Manufacturing technology Market appeal Market appeal Market appeal 6 A.T. Nguyen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 packaging material is consistent with earlier studies. For example, Allegra et al. (2012) and Lewis and Stanley (2012) found that consumers regard paper as one of the most eco-friendly materials. Likewise, according to Lindh et al. (2016a), consumers consider paper-based packaging as having the least negative environmental impact, and thus being the most environmentally advantageous. Dilkes-Hoffman et al. (2019) and Steenis et al. (2017) also report that consumers judge paper-based packaging as more sustainable than plastic packaging. In practice, consumers’ environmental awareness is driving the demand of paper packaging for food because it is both economically and environmentally appealing (Furlong, 2015). The fact that consumers perceive paper-based packaging to be eco-friendly could be a paradox, if we consider the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of a paper packaging product’s life. The development of LCA in assessing environmental impacts of packaging takes into account the package manufacturing process, the food packaging process, the transport phases, and the end-of-life management of different types of packaging (Bertolini et al., 2016). If tested by LCA, packaging of any type is considered to be environmentally damaging primarily for its material use and disposal issues at the end of its life (Grant et al.,2015). However, paper and cardboard can be worse for the environment compared to plastic, because of the amount of materials required to make packaging fitfor-purpose (Verghese et al., 2015), and associated impacts driven by agricultural processes and end of life degradation (Boesen et al., 2019). There is a discrepancy between what consumers perceive and what is scientifically measured in terms of eco-friendly packaging. As pointed out by Steenis et al. (2017), a study on consumer perceptions and LCA indicates that consumers hold inaccurate beliefs about packaging. One of the reasons may be that consumers’ relationship with packaging is only for short periods. The desire is for the product that the packaging contains, not with the package itself (Grant et al.,2015). Furthermore, consumers pay attention to the environmental effects of the end of packaging life (Herbes et al., 2018) because they are visible. Nevertheless, the consensus among consumers relating to paper-based packaging in our study could be considered as an important input for strategists who wish to educate consumers about the environmental characteristics of different types of packaging materials. Some participants preferred plastic packaging even though it might be regarded by many others as less eco-friendly. One participant (participant 14, college student) said that he preferred plastic packages, even when he knew they were not eco-friendly. This is because to most consumers, plastic provides convenience, hygiene and ease of use. A few participants still stated that plastic could be eco-friendly, for instance: I still think that plastic packaging is eco-friendly. (Female, tailor) According to LCA, plastic can be more eco-friendly than paper packaging in some impact categories, such as water and energy consumption, given the raw materials required for production (Boesen et al., 2019). However, this fact may be unknown to this participant and to most consumers. Our study shows that there are consumer groups who give preference to plastic packaging for food products although they are not fully aware about the environmental impacts of different types of packaging materials. This triggers a question about why consumers hold preference for plastic packaging. The analysis of market appeal characteristics of packaging in Section 3.3 serves to explain why plastic packaging is more appealing to some consumers, as well as to provide useful input for eco-friendly packaging marketers to enhance the attractiveness of their products. Overall, the inconsistencies in consumer perceptions of different types of packaging materials, such as paper and plastic, reveals that consumers cannot clearly distinguish between less and more ecofriendly packaging materials. This might be because there are several different types of plastic materials and it is often difficult to rank them according to their environmental indicators (Orset et al., 2017). Whilst LCA is the most comprehensive and complete tool for quantitatively assessing environmental impacts of different types of food packaging (Barros et al., 2018; Morris, 2005; Vignali, 2016), it is often used as an in-house tool, and its results are not available to the public. When made public, LCA results can simply confuse consumers due to the complexity of such data. Without access to these data or an understanding of what they mean, consumers cannot accurately know what is and is not environmentally sustainable through these metrics. In Vietnam, about 90 per cent of packaged instant noodles are in plastic bag-type (Dong, 2016). The dominance of plastic packaging in the packaged instant noodle market of Vietnam might produce effects on consumer preference that mean the more abundantly available and therefore more familiar the type of packaging, the more welcome it is. This indicates a need for research into the commonly used packaging materials for packaged foods and the effects on consumer preferences and purchase decisions, which is not covered in our study. 3.2. Manufacturing technology Manufacturing technology emerged as the second dimension relating to eco-friendly packaging in the focus groups. In consumer views, eco-friendly packaging should come from an eco-friendly manufacturing process, and favourably from the use of natural and organic sources of raw materials. This could again be a paradox based on LCA measurements of synthetic versus natural material production (Boesen et al., 2019), which might be unknown to consumers. In the focus groups, there were several opinions about sources of materials used to produce packaging that could reduce negative impacts on the environment, for example: Eco-friendly packaging should come from a good choice of raw materials: materials used to produce eco-friendly packaging must be eco-friendly. (Male, office worker) Consumer concerns about raw materials used to produce packaging correlate with findings from Palombini et al. (2017), which showed that packaging materials are often associated with environmental issues. Furthermore, most focus group participants stressed that the manufacturing process should be improved to minimise negative environmental impacts. They declared that the responsibility for providing eco-friendly packaging should lie with manufacturers, rather than leaving it to consumers to demand such packaging. They also underlined the need to implement an ecofriendly manufacturing process, such as: The manufacturing process must be simplified, to reduce costs and minimise adverse consequences to the environment. (Female, sales staff) Our findings fit Scott and Vigar-Ellis’ (2014) results, which show that consumers expect packaging manufacturers to adopt an ecofriendly manufacturing process. In addition, consumers in our study verbally expressed their expectations about the manufacturing process, specifically: Of course, it is the responsibility of manufacturers to ensure the packaging manufacturing process is eco-friendly. To me, the three most important things about eco-friendly packaging are: first, use A.T. Nguyen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 7 materials which take shorter time for decomposition; second, simplify the manufacturing process to not pollute the environment and third, make good use of natural and organic materials like paper, bamboo and banana leaves. (Female, accountant) seen as lesser quality than plastic. As reported by Magnier and ’s (2015), eco-friendly packaging is often perceived as less Crie appealing by consumers, because of its simplicity and lack of colours. Our study recorded several negative comments on the low attractiveness of biodegradable and paper packaging. For instance: These consumer opinions represent a dilemma in terms of cleaner production. That is, whose job is it to be environmentally responsible - the consumer or the manufacturer? (Brennan et al., 2015b). Although participants emphasised that the role of manufacturers is to ensure an eco-friendly manufacturing process, they could not clearly discuss technological terms and only used general terms such as ‘advanced’ and ‘new technology’: A biodegradable package is not attractive at all to buyers. (Female, craftsperson) Manufacturers have to apply new advanced technology for ecofriendly packaging. (Male, IT technician) Overall, consumer understanding of manufacturing technology seemed to be limited and they struggled to share what they knew about technology. The technological aspects of packaging production might be beyond an average consumer’s knowledge (Esbjerg et al., 2016), and therefore, consumers’ limited understanding of manufacturing technology is not unique to the Vietnamese market. 3.3. Market appeal The third dimension of eco-friendly packaging which emerged from the focus groups is market appeal. In our study, market appeal is defined as the ability of a packaged food product to attract consumers’ attention at the point of purchase. Market appeal is interpreted in consumer terms, embracing three attributes: visual presentation, functional performance and price. 3.3.1. Visual presentation Participants stated that product packages should be visually appealing. Most participants said that regardless of whether packaging was eco-friendly or not, it should be attractively designed and affordable. Many emphasised that they made purchase decisions in store outlets based on the attractive appearance of packaging. Colour and images were found to be used on packaging in order to attract consumer attention, and proved to be effective. For example: Nice design of graphics on packaging strongly influences my decision to buy a packaged food product. (Female, office worker) Attractive design of packaging in the form of graphic images was highly favoured by participants. This observation contradicts Martinho et al. (2015) who found that packaging design is not an important factor to consumers; and that low price is more important. However, others have found, in alignment with our study, that aesthetically appealing packaging designs can increase desire for a product (Norman, 2005), encourage willingness to pay a premium (Bloch et al., 2003), increase preference over well-known brands (Reimann et al., 2010), and enable more direct comparison of alternatives, as well as attract the consumer’s attention (Venter et al., 2011). Our study supports the findings of Tait et al. (2016) who found that graphic images impacted on consumer choice of packaged food products. Mueller et al. (2010) also reported that a graphic label format was the second most important attribute after price. Hence, aesthetic appeal of packaging is an important criterion in consumers’ buying consideration. In this study, most research participants stated that eco-friendly packaging was not aesthetically pleasing. In consumer perceptions, eco-friendly packaging, either biodegradable or paper-based, was I do not like paper packages because they are so plain and uglylooking. (Female, tailor) Focus group participants gave positive comments about the appealing characteristics of plastic packaging in the market. Most stated that buying INs in plastic packaging was undeniably a common behaviour because the usual packaging for INs was plastic bag-type with colourful graphic designs. Many indicated the likelihood of choosing plastic packaging over other types of packaging, citing the reasons of abundant availability in the market and the attractive graphic design. For example: Plastic packaging for instant noodles is so abundantly available and we buy them. (Female, fashion trader) I choose plastic packaging. It is eye-catching and very attractive with colourful images. (Female, sale staff) In addition to attractive graphic design, participants highlighted brand name as another determinant attribute. Many said that a well-known brand indicated quality. Hence, a good graphic design of the package, combined with a well-known brand, would affect their choice. For instance: Eco-friendly packaging such as paper packaging is boring. Paper packages are boring with dull colours and poor graphic images. At the point of purchase, a nice graphic design of the package plus a well-known brand will absolutely affect our buying decisions. (Female, accountant) When asked about the most well-known brand of IN in the market, most participants mentioned Hao Hao. Hao Hao is a brand of Acecook, a Japanese-owned instant noodle company operating in Vietnam. The brand itself occupies 25 per cent market share while Acecook as a whole accounts for 43 per cent of the market (Vietnam Investment Review, 2017). To many participants, a well-known brand was influential at the point of purchase: When it comes to instant noodles, we will say Hao Hao. We choose Hao Hao products as this brand is so famous. (Female, accountant) According to Schuitemai and De Groot (2015), consumers tend to focus on egoistic product attributes (i.e. to fulfil self-serving motives such as a nice design and a well-known brand), before attending to green product attributes. While some participants expressed willingness to buy eco-friendly packaging, other product attributes - nice design and well-known brand - were emphasised by many participants as being more important. This indicates a complexity in consumer behaviour towards eco-friendly packaging. Consumers desire eco-friendly packages which have aesthetic appeal of the design reinforced by a well-known brand. 3.3.2. Functional performance In this study, only a few participants raised concerns about the protective performance of packaging. They stated that packaging must be able to protect the product and that this attribute would 8 A.T. Nguyen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 also influence their purchase intentions. Specifically, IN packaging should ensure that the noodles were tasty, easy to access, not broken or degraded, and easy to prepare and eat ‘instantly’. All other considerations were secondary to the motivation of taste, convenience and ‘instantaneous’ availability. This is expressed as being fit-for-purpose by Verghese and Lewis (2007), who state that packaging materials should be selected to provide sufficient protection to the contents inside, while maintaining the effective use of materials with the lowest environmental impact. Additionally, some participants said they would trade off the eco-friendly characteristics of the package against functional attributes. While expressing views that paper packaging could be the most ecofriendly, some also commented that paper packages were not as effective in protecting the quality of instant noodles as plastic ones: I do not think a paper package can protect the product. It is easily torn out and can damage the product quality. Plastic packaging provides better protection. (Female, sales staff) Other than these few participants expressing concerns for protective performance of paper packages, most participants did not even mention the functions of packaging. This awareness (or lack thereof) is contrary to concepts suggested by Verghese et al.’s (2015) study, which highlights the core functional attributes of packaging as a major contribution to sustainability. This research finding might imply that Vietnamese consumers consider market appealing attributes of a package design as more important than functional attributes of the package. 3.3.3. Price Regarding price, most focus group participants were very insistent that eco-friendly packaging must be reasonably priced. Eco-friendly packaging was perceived to be more expensive, leading to increased consumer costs. Hence, the decision to buy INs packaged environmentally was driven by affordability and convenience: No matter how attractive the package is, the product price should be affordable to encourage a trial. (Male, IT staff) Previous studies have also reported that eco-friendly packaging is perceived by consumers to be more expensive, and so many , 2015). Likeconsumers are not willing to pay (Magnier and Crie wise, Martinho et al. (2015) found that price is one of the most important criteria in consumers’ purchasing consideration. In contrast, consumers in South Africa seemed to have long-term perspectives as they believed that eco-friendly packaging would save money because it was reusable (Scott and Vigar-Ellis, 2014). In our study, most participants were not willing to pay extra or to invest in eco-friendly packaging for long-term environmental benefits. While only a few expressed their willingness to pay a premium for INs packaged environmentally, many stressed that they would only pay extra once they were satisfied with the market appeal characteristics of the product or package. Krystallis and Chryssohoidis (2005) similarly reported that unless consumers are entirely convinced that the product satisfies the market appeal criteria at the point of purchase, they are not willing to pay a premium price. Thus, market appeal characteristics of the product or the package seem to be the most important criteria for many Vietnamese consumers when it comes to purchase behaviour. 4. Conclusions This is the first study on the topic of consumer perceptions of eco-friendly packaging in the Southeast Asian emerging market of Vietnam. This study identifies three key dimensions of eco-friendly packaging from a consumer perspective. These categories will be of practical use for manufacturers and marketers of packaged food products in designing packaging options acceptable to consumers. What is new in this study is the classification of three key dimensions reflecting consumers’ characterisations of eco-friendly packaging, namely, packaging materials, manufacturing technology, and market appeal. The first dimension identified in our study is that of packaging materials. Consumers use their evaluation of different types of packaging materials to determine what an eco-friendly package should be. Plastic is perceived as the least eco-friendly material whereas paper or biodegradable materials are both considered environmentally friendly. Plastic is viewed negatively with regard to its environmental impact. However, consumers acknowledge the increased protective performance of plastic packaging, compared to paper-based packaging. Consumers pay more attention to material properties in respect of environmental effects of packaging materials. Hence, LCA application in assessing materials for packaging could be used to enhance consumers’ and manufacturers’ comparison of the environmental performance of plastic versus paper, which would in turn result in a more precise evaluation of ecofriendly packaging. Still, it must be noted that consumers consider that the responsibility for eco-friendly packaging should lie with the manufacturer as the consumer merely buys what is available. This insight provides an opportunity for major brands to take a lead in decreasing the environmental impacts of their products. This will be especially important as the Vietnamese economy shifts from centrally planned to a more market and consumer-based demand economy. Moving towards a completely consumer demand system may increase environmental costs of packaging, particularly if the key criterion for selecting a product is price. The second dimension of eco-friendly packaging concerns manufacturing technology. Consumer understanding of manufacturing technology seems to be limited. One of the challenges to acceptance of new products is consumers’ limited understanding of technologies. Consumers are unable to evaluate manufacturing processes or account for the use of energy and materials in order to estimate which product or packaging is the least harmful to the environment. Making the findings of the LCA public, simple and understandable, is one way this could be addressed, by linking manufacturing inputs to environmental impacts. Nevertheless, the technological aspects of the manufacturing process might be beyond an average consumer’s capacity to engage with, because most processes are not visible to consumers. Therefore, educating consumers about the packaging life cycle might be a good start to make them fully aware of related environmental effects. However, given the nature and rate of change in Vietnam’s rapidly developing market, keeping up with information flows about technology might be beyond the consumer’s capacity to assimilate. Consequently, a more product driven approach to decreasing environmental impacts is suggested. That is, an approach that does not leave it to the consumer to make informed demands for eco-friendly packaging when they cannot understand the technological or manufacturing implications for packaging design, or the implications for food waste. The third dimension of eco-friendly packaging is related to market appeal. Consumers have their expectations for eco-friendly packaging related to attractive graphic design, functional performance and price. With regard to graphic design, consumers are attracted by colourful images on the package. Furthermore, consumers are dissatisfied with the poor appearance of paper-based packages (which they considered to be eco-friendly in the current A.T. Nguyen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 study). This is something that manufacturers can take into account when it comes to designing an eco-friendly package that can also catch the attention of shoppers. In terms of functional performance, most consumers do not really take the functions of packaging into account. Consumers in Vietnam give more weight to market appealing attributes whereas the functional performance of packaging does not receive the same level of consideration. Still, consumers want a package that can protect the product. Hence, the minimum requirement for a package is to protect the product, ensuring the package is fit-forpurpose. In practice, the main function of packaging (regardless of what types of packaging) is to protect the product throughout its shelf life. This re-emphasises the functional role that eco-friendly packaging should play in order to gain acceptance of some consumer segments while also satisfying aesthetic needs of other consumer segments. Importantly, function precedes aesthetic appeal and consumers will purchase ‘ugly’ packaging if they understand its purpose, but not if there is a product available that satisfies both functional and aesthetic appeals at the same price point. As far as price is concerned, Vietnamese consumers desire ecofriendly packaging that is priced equal to or even cheaper than conventional packaging. Price is therefore a barrier to purchase behaviour towards eco-friendly packaging. This might push manufacturers of packaged food products to consider cost-effective solutions for eco-friendly packaging alternatives to stay competitive in the market and to decrease their environmental footprint. This may require governments and industries to become more involved in setting guidelines for packaging designs that ensure a minimum standard for environmental impacts. Relying on consumers to demand eco-friendly packaging and to pay a premium price is not a workable solution. In summary, our study shows that consumers are aware of plastic pollution and have some perceived knowledge of ecofriendly packaging. Consumers are also able to express their perceptions of the main dimensions of eco-friendly packaging. Their expectations of eco-friendly packaging are primarily associated with packaging materials (such as biodegradability and recyclability), and to market appeal (such as attractive graphic design and good price). In addition, consumer perceptions towards current package manufacturing technologies appear to convey a desire to have more advanced eco-friendly technologies to reduce adverse impacts of the manufacturing process. Our study indicates that businesses could be better off if consumer-defined dimensions (packaging materials, manufacturing technology and market appeal) are considered in production and marketing practices of packaged food products. This paper adds to the literature on consumer perceptions of eco-friendly packaging in an emerging economy. It provides an indepth analysis from a consumer perspective and identifies three major dimensions relating to eco-friendly packaging, namely, packaging materials, manufacturing technology and market appeal. Thus, it builds a practical understanding of consumer expectations for eco-friendly packaging, which can provide useful input to manufacturers and marketers of packaged food products. For ecofriendly packaging to be accepted in the market, it must satisfy not only the environmental attributes of packaging materials and manufacturing processes, but also the market appeal attributes of the package which should be aesthetic, fit-for-purpose, and reasonably priced. Practically, this knowledge provides an opportunity for brands to engage with consumers directly, whether that is to use consumers to help specify packaging, or to communicate to consumers the ways packaging can play a role in sustainability as Verghese et al. (2015) suggest. Packaging managers can use the key dimensions identified in this paper as practical input for their packaging design strategy. 9 Consumers are concerned with disposal issues of packaging materials, but they are more interested in the market appeal of packaging. Therefore, in packaging strategy, manufacturers should take into account not only consumer concerns for environmental impacts of packaging materials but also market appeal in terms of aesthetics, price and protection. By considering these dimensions collectively, businesses will have a better chance of engaging consumers to purchase food products packaged in an environmentally conscious way. Future research could extend this study by focusing on products with a higher level of purchase involvement. Further research on consumer perceptions of eco-friendly packaging could also take the effects of brand image into consideration. As consumers may be influenced by well-known brands at the point of purchase, knowledge of brand image and its effects on consumers’ purchase intentions for eco-friendly packaging could help explain the complexity in green consumer behaviour. Moreover, exploring relationships between brand image and corporate social responsibility with consumer perceptions of eco-friendly packaging could shed more light on proposed practices of packaging strategies of manufacturers, the legislation practices of the government sector in sustainable production, and ultimately consumer behaviour that results. Funding This work was supported by RMIT University Vietnam (Grant number 05-2014). Two of the Investigators are supported by the Fight Food Waste Cooperative Research Centre https://fightfoodwastecrc.com.au/. Declaration of competing interest The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. CRediT authorship contribution statement Anh Thu Nguyen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing original draft. Lukas Parker: Supervision, Methodology, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Linda Brennan: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Simon Lockrey: Visualization, Writing - review & editing. References Allegra, V., Zarba, A.S., Muratore, G., 2012. The post-purchase consumer behaviour, survey in the context of materials for food packaging. Ital. J. Food Sci. 24 (4), 160e164. Barber, N., 2010. Green wine packaging: targeting environmental consumers. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 22 (4), 423. Barros, M.V., Salvador, R., Piekarski, C.M., de Francisco, A.C., 2018. Mapping of main research lines concerning life cycle studies on packaging systems in Brazil and in the world. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 1e15. Basit, T.N., 2003. Manual or electronic? The role of coding in qualitative data analysis. Educ. Res. 45 (2), 143e154. Becker, L., van Rompay, T.J., Schifferstein, H.N., Galetzka, M., 2011. Tough package, strong taste: the influence of packaging design on taste impressions and product evaluations. Food Qual. Prefer. 22 (1), 17e23. Bertolini, M., Bottani, E., Vignali, G., Volpi, A., 2016. Comparative life cycle assessment of packaging systems for extended shelf life milk. Packag. Technol. Sci. 29 (10), 525e546. Biswas, A., Roy, M., 2015. Green products: an exploratory study on the consumer behaviour in emerging economies of the East. J. Clean. Prod. 87, 463e468. Bloch, P.H., Brunel, F.F., Arnold, T.J., 2003. Individual differences in the centrality of visual product aesthetics: concept and measurement. J. Consum. Res. 29 (4), 551e565. Boesen, S., Bey, N., Niero, M., 2019. Environmental sustainability of liquid food 10 A.T. Nguyen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 packaging: is there a gap between Danish consumers’ perception and learnings from life cycle assessment? J. Clean. Prod. 210, 193e1206. Boks, C., Stevels, A., 2007. Essential perspectives for design for environment: experiences from the electronics industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 45 (18e19), 4021e4039. Brennan, L., Parker, L., Nguyen, D., Aleti Watne, T., 2015a. Chapter 6: design issues in cross-cultural research: suggestions for researchers. In: Strang, K. (Ed.), Palgrave Handbook of Research Design in Business and Management. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY, pp. 81e101. Brennan, L., Binney, W., Hall, J., Hall, M., 2015b. Whose job is that? Saving the biospheres starts at work. J. Nonprofit & Public Sect. Mark. 27 (3), 307e330. Brinkmann, S., 2014. Interview. In: Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology. Springer, New York, pp. 1008e1010. Calderwood, I., 2018. 16 times countries and cities have banned single-use plastics. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/plastic-bans-aroundthe-world/. (Accessed 18 December 2018). Central Intelligence Agency US, 2018. The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/ library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/vm.html. (Accessed 14 June 2018). Clarke, V., Braun, V., 2014. Thematic analysis. In: Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-being Research. Springer, New York, pp. 6626e6628. Coulson, N.S., 2000. An application of the stages of change model to consumer use of food labels. Br. Food J. 102 (9), 661e668. Creswell, J.W., 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Method Approaches, third ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, California. Dan Tri News, 2019. Ho Chi Minh City campaign calls for joint actions to reduce plastic waste. http://dtinews.vn/en/news/017/61144/hcm-city-campaign-callsfor-joint-actions-to-reduce-plastic-waste.html. (Accessed 11 April 2019). Davies, I.A., Gutsche, S., 2016. Consumer motivations for mainstream ‘ethical’ consumption. Eur. J. Market. 50 (7/8), 1326e1347. De Koning, J.I.J.C., Crul, M.R.M., Wever, R., Brezet, J.C., 2015. Sustainable consumption in Vietnam: an explorative study among the urban middle class. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 39 (6), 608e618. Deloitte, 2018. Deloitte Resources 2018 Study. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/ dam/insights/us/articles/4568_Resource-survey-2018/DI_Deloitte-Resources2018-survey.pdf. (Accessed 3 January 2019). Denzin, N.K., 2019. The Qualitative Manifesto: A Call to Arms. Routledge, New York. Dilkes-Hoffman, L.S., Pratt, S., Laycock, B., Ashworth, P., Lant, P.A., 2019. Public attitudes towards plastics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 147, 227e235. € Dominic, C.A., Ostlund, S., Buffington, J., Masoud, M.M., 2015. Towards a conceptual sustainable packaging development model: a corrugated box case study. Packag. Technol. Sci. 28 (5), 397e413. Dong, Nguoi Lao, 2016. Thi truong mi goi - instant noodle market in Vietnam. http://nld.com.vn/thi-truong-mi-goi.html. (Accessed 20 January 2016). €€ €lkki, T., Utriainen, K., Kyng€ Elo, S., Ka ari€ ainen, M., Kanste, O., Po as, H., 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis: a Focus on Trustworthiness, vol. 4. Sage Open, pp. 1e10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633 (1). Engel, H., Stuchtey, M., Vanthournout, H., 2016. Managing waster in emerging markets. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/ourinsights/managing-waste-in-emerging-markets. (Accessed 15 March 2019). Esbjerg, L., Burt, S., Pearse, H., Glanz-Chanos, V., 2016. Retailers and technologydriven innovation in the food sector: caretakers of consumer interests or barriers to innovation? Br. Food J. 118 (6), 1370e1383. Euromonitor, 2017. Packaged food in Vietnam. http://www.euromonitor.com/ packaged-food-in-vietnam/report. (Accessed 1 July 2017). Fernqvist, F., Olsson, A., Spendrup, S., 2015. What’s in it for me? Food packaging and consumer responses, a focus group study. Br. Food J. 117 (3), 1122e1135. Furlong, H., 2015. Trending: sustainability demand spurs new packaging innovations. http://www.sustainablebrands.com/news_and_views/packaging/ hannah_furlong/trending_sustainability_demand_spurs_new_packaging_ innovatio. (Accessed 2 May 2017). Giorgi, A., 2009. The Descriptive Phenomenological Method in Psychology: A Modified Husserlian Approach. Duquesne University Press. Grant, T., Barichello, V., Fitzpatrick, L., 2015. Accounting the impacts of waste product in package design. Procedia CIRP 29, 568e572. Guest, G., Namey, E., McKenna, K., 2017. How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods 29 (1), 3e22. Hao, Y., Liu, H., Chen, H., Sha, Y., Ji, H., Fan, J., 2019. What affect consumers’ willingness to pay for green packaging? Evidence from China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 141, 21e29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.10.001. Herbes, C., Beuthner, C., Ramme, I., 2018. Consumer attitudes towards biobased packaging - a cross-cultural comparative study. J. Clean. Prod. 194, 203e218. Howard, B.C., Gibbens, S., Zachos, E., Parker, E., 2018. A running list of action on plastic pollution. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/07/ ocean-plastic-pollution-solutions/?user.testname¼none. (Accessed 10 November 2018). Kirwan, M.J., Plant, S., Strawbridge, J.W., 2011. Plastics in food packaging. In: Coles, R., Kirwan, M. (Eds.), Food and Beverage Packaging Technology. WileyBlackwell Publisher, UK, pp. 157e293. Koenig-Lewis, N., Palmer, A., Dermody, J., Urbye, A., 2014. Consumers’ evaluations of ecological packaging - rational and emotional approaches. J. Environ. Psychol. 37, 94e105. Krystallis, A., Chryssohoidis, G., 2005. Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic food: factors that affect it and variation per organic product type. Br. Food J. 107 (5), 320e343. Laforet, S., 2011. Brand names on packaging and their impact on purchase preference. J. Consum. Behav. 10 (1), 8e30. Lewis, H., Stanley, H., 2012. Marketing and communicating sustainability. In: Verghese, K., Lewis, H., Fitzpartrick, L. (Eds.), Packing for Sustainability. @ Springer-Verlag London Limited 2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-85729988-8_3. Liao, L.X., Corsi, A.M., Chrysochou, P., Lockshin, L., 2015. Emotional responses towards food packaging: a joint application of self-report and physiological measures of emotion. Food Qual. Prefer. 42, 48e55. Lindh, H., Olsson, A., Williams, H., 2016a. Consumer perceptions of food packaging: contributing to or counteracting environmentally sustainable development? Packag. Technol. Sci. 29 (1), 3e23. €m, F., 2016b. Elucidating the indirect Lindh, H., Williams, H., Olsson, A., Wikstro contributions of packaging to sustainable development: a terminology of packaging functions and features. Packag. Technol. Sci. 29 (4e5), 225e246. Lockrey, S., Brennan, L., Verghese, K., Staples, W., Binney, W., 2018. Enabling employees and breaking down barriers: behavioural infrastructure for proenvironmental behaviour. In: Wells, V.K., Gregory-Smith, D., Danae Manika, D. (Eds.), Research Handbook on Employee Pro-environmental Behaviour. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, pp. 313e348. , D., 2015. Communicating packaging eco-friendliness: an exploMagnier, L., Crie ration of consumers’ perceptions of eco-designed packaging. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 43 (4/5), 350e366. Magnier, L., Schoormans, J., 2015. Consumer reactions to sustainable packaging: the interplay of visual appearance, verbal claim and environmental concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 44, 53e62. Martinho, G., Pires, A., Portela, G., Fonseca, M., 2015. Factors affecting consumers’ choices concerning sustainable packaging during product purchase and recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 103, 58e68. Mason, M., 2010. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews, in: forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qual. Soc. Res. 11 (3) https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.3.1428. Mishra, P., Jain, T., Motiani, M., 2017. Have green, pay more: an empirical investigation of consumer’s attitude towards green packaging in an emerging economy. In: Essays on Sustainability and Management. Springer Singapore, pp. 125e150. Morris, J., 2005. Comparative LCAs for curbside recycling versus either landfilling or incineration with energy recovery. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 10 (4), 273e284. Mueller, S., Lockshin, L., Louviere, J.J., 2010. What you see may not be what you get: asking consumers what matters may not reflect what they choose. Mark. Lett. 21, 335e350. Murray, J.M., Delahunty, C.M., 2000. Mapping consumer preference for the sensory and packaging attributes of Cheddar cheese. Food Qual. Prefer. 11 (5), 419e435. Nielsen, 2016. News Release: Vietnamese just love convenient cleanliness. http:// www.nielsen.com/content/dam/nielsenglobal/vn/docs/PR_EN/Vietnam_Home% 20Care%20PR_EN.pdf. (Accessed 2 June 2017). Norman, D.A., 2005. Emotional Design: Why We Love (Or Hate) Everyday Things. Basic Books, New York. Orset, C., Barret, N., Lemaire, A., 2017. How consumers of plastic water bottles are responding to environmental policies? Waste Manag. 61, 13e27. Palombini, F.L., Cidade, M.K., de Jacques, J.J., 2017. How sustainable is organic packaging? A design method for recyclability assessment via a social perspective: a case study of Porto Alegre city (Brazil). J. Clean. Prod. 142, 2593e2605. Parker, L., 2015. Eight million tons of plastic dumped in ocean every year. http:// news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2015/02/150212-ocean-debris-plasticgarbage-patches-science/. (Accessed 26 February 2019). Parker, L., 2018. We made plastic. We depend on it. Now we’re drowning in it. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/06/plastic-planet-wastepollution-trash-crisis/. (Accessed 10 November 2018). til, J., 2019. The factors of lifestyle of health and sustainability Pícha, K., Navra influencing pro-environmental buying behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 234, 233e241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.072. Prakash, G., Pathak, P., 2017. Intention to buy eco-packaged products among young consumers in India: a study on developing nation. J. Clean. Prod. 141, 385e393. Prakash, G., Choudhary, S., Kumar, A., Garza-Reyes, J.A., Khan, S.A.R., Panda, T.K., 2019. Do altruistic and egoistic values influence consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions towards eco-friendly packaged products? An empirical investigation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 50, 63e169. Rankin, J., 2019. Single-use plastics ban approved by European Parliament. The Guardian 27 March 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/ mar/27/the-last-straw-european-parliament-votes-to-ban-single-use-plastics. (Accessed 24 November 2019). Reimann, M., Zaichkowsky, J., Neuhaus, C., Bender, T., Weber, B., 2010. Aesthetic package design: a behavioural, neural and psychological investigation. J. Consum. Psychol. 20 (4), 431e441. Ritch, E.L., 2015. Consumers interpreting sustainability: moving beyond food to fashion. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 43 (12), 1162e1181. Ritschel, C., 2018. Why is plastic bad for the environment and how much is in the ocean? https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/plastic-bad-environmentwhy-ocean-pollution-how-much-single-use-facts-recycling-a8309311.html. (Accessed 20 June 2019). Rokka, J., Uusitalo, L., 2008. Preference for green packaging in consumer product choices e do consumers care? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 32 (5), 516e525. Roper, S., Parker, C., 2013. Doing well by doing good: a quantitative investigation of A.T. Nguyen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 252 (2020) 119792 the litter effect. J. Bus. Res. 66 (11), 2262e2268. Rundh, B., 2005. The multi-faceted dimension of packaging: marketing logistic or marketing tool? Br. Food J. 107 (9), 670e684. Saunders, M., Lewis, P., Thornhill, A., 2012. Research Methods for Business Students, sixth ed. Pearson Education Limited. Schuitemai, G., De Groot, J.I.M., 2015. Green consumerism: the influence of product attributes and values on purchasing intentions. J. Consum. Behav. 14, 57e69. Scott, L., Vigar-Ellis, D., 2014. Consumer understanding, perceptions and behaviours with regard to environmentally friendly packaging in a developing nation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 38, 642e649. Silayoi, P., Speece, M., 2007. The importance of packaging attributes: a conjoint analysis approach. Eur. J. Market. 41 (11/12), 1495e1517. Simms, C., Trott, P., 2010. Packaging development: a conceptual framework for identifying new product opportunities. Mark. Theory 10 (4), 397e415. Spiggle, S., 1994. Analysis and interpretation of qualitative data in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 21 (3), 491e503. Steenis, N.D., van der Lans, I.A., van Herpen, E., van Trijp, H.C., 2018. Effects of sustainable design strategies on consumer preferences for redesigned packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 205, 854e865. Steenis, N.D., van Herpen, E., van der Lans, I.A., Ligthart, T.N., van Trijp, H.C., 2017. Consumer response to packaging design: the role of packaging materials and graphics in sustainability perceptions and product evaluations. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 286e298. Strang, K., Brennan, L., Vajjhala, R., Hahn, J., 2015. Gaps to address in future research design practices. In: Strang, K. (Ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Research Design in Business and Management. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY. Sustainable Packaging Coalition, 2011. Definition of sustainable packaging. http:// sustainablepackaging.org/uploads/Documents/Definitionper cent20ofper cent20Sustainableper cent20Packaging.pdf. (Accessed 20 March 2016). Tait, P., Saunders, C., Guenther, M., Rutherford, P., Miller, S., 2016. Exploring the impacts of food label format on consumer willingness to pay for environmental sustainability: a choice experiment approach in the United Kingdom and Japan. Int. Food Res. J. 23 (4), 1787e1796. Taylor, R., Villas-Boas, S.B., 2016. Food store choices of poor households: a discrete choice analysis of the national household food acquisition and purchase survey (FoodAPS). Am. J. Agri. Econ. 98 (2), 513e532. Trowsdale, A., Housden, T., Meier, B., 2017. Seven charts that explain the plastic pollution problem. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-42264788. 11 (Accessed 10 November 2018). Van Birgelen, M., Semeijn, J., Keicher, M., 2009. Packaging and proenvironmental consumption behaviour: investigating purchase and disposal decisions for beverages. Environ. Behav. 41 (1), 125e146. Venter, K., van der Merwe, D., de Beer, H., Kempen, E., Bosman, M., 2011. Consumers’ perceptions of food packaging: an exploratory investigation in Potchefstroom, South Africa. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 35 (3), 273e281. Verghese, K., Lewis, H., 2007. Environmental innovation in industrial packaging: a supply chain approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 45 (18e19), 4381e4401. Verghese, K., Lewis, H., Lockrey, S., Williams, H., 2015. Packaging’s role in minimizing food loss and waste across the supply chain. Packag. Technol. Sci. 28 (7), 603e620. Vietnam Investment Review, 2017. Vietnam’s instant noodle giants. http://www.vir. com.vn/vietnams-instant-noodle-giants-54058.html. (Accessed 14 June 2018). Vietnam News, 2013. Vietnam steps closer to green production. http://Vietnam. News.vn/economy/245115/viet-nam-steps-closer-to-green-production.html. (Accessed 24 February 2016). Vietnam News, 2018. Heavy fines fail to stop littering. https://vietnamnews.vn/ society/462834/heavy-fines-fail-to-stop-littering.html#f6ieeitlej8ICkYy.97. (Accessed 28 March 2019). Vignali, G., 2016. Life-cycle assessment of food-packaging systems. In: Muthu, S. (Ed.), Environmental Footprints of Packaging. Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes. Springer, Singapore. €m, F., Williams, H., Verghese, K., Clune, S., 2014. The influence of packaging Wikstro attributes on consumer behaviour in food-packaging life cycle assessment studies - a neglected topic. J. Clean. Prod. 73, 100e108. €m, F., Verghese, K., Auras, R., Olsson, A., Williams, H., Wever, R., Wikstro € nman, K., Kvalvåg Pettersen, M., Møller, H., Soukka, R., 2018. Packaging Gro strategies that save food: a research agenda for 2030. J. Ind. Ecol. https:// doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12769. Winn, P., 2016. Five countries dump more plastic into the oceans than the rest of the world. Public Radio Int. https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-01-13/5-countriesdump-more-plastic-oceans-rest-world-combined. (Accessed 25 April 2019). World Instant Noodles Association, 2018. Global demand for instant noodles. https://instantnoodles.org/en/noodles/market.html. (Accessed 10 November 2018). Young, S., 2008. Packaging and the environment: a cross-cultural perspective. Desig. Manag. Rev. 19, 41e48.