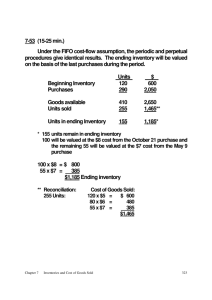

Answers to Questions CMA Part 1 Answers to Questions 1 b – Current liabilities are those liabilities that will be settled within one year or during the operating cycle if it is longer than one year. Long-term debt that matures within one year and will be retired through the use of current assets is a current liability. 2 d – A statement of financial position (balance sheet) cannot provide a basis for determining profitability and assessing past performance for a specific period. An income statement is required for that. 3 a – The income statement reports the results of operations for a period of time. 4 d – Comprehensive income includes the results of all transactions except for those that are carried out with owners, such as investments by owners and the sale of new shares and distribution of dividends. It includes all changes in equity (net assets, or total assets less total liabilities) of an entity during a period from transactions and other events and circumstances other than those resulting from investments by owners and distributions to owners. 5 d – Dividends paid to company shareholders are shown on the statement of cash flows as cash flows from financing activities. 6 d – The correct order of presentation in the statement of cash flows is: (1) cash flows from operating activities, (2) cash flows from investing activities, and (3) cash flows from financing activities. That is the order of presentation whether the direct or the indirect method is being used to report net cash flow from operating activities. 7 c – Net cash flow from operating activities is: Net income Plus: Depreciation expense Plus: Increase in accounts payable Minus: Increase in accounts receivable Plus: Increase in deferred income tax liability Net cash provided by operating activities $ 920,000 110,000 45,000 (73,000) 16,000 $1,018,000 8 a – The direct method of calculating net cash provided by operating activities presents the major classes of operating cash receipts such as receipts from customers less the major classes of operating cash disbursements such as cash paid for merchandise. This presentation is different from the indirect method of presentation because the indirect method begins with net income and adjusts net income to (1) include net changes in operating cash that do not appear on the income statement and (2) to remove noncash items that are included in the income statement. 9 b – The indirect method of calculating and reporting a company’s net cash flow from operating activities on its statement of cash flows is the method most commonly used. 10 d – The cash received from the sale of the stock was $150,000, and that is the amount that should be shown for the transaction in the cash flows from investing activities section of James’ statement of cash flows. 11 d – The transaction should be disclosed in the statement of cash flows as a noncash financing activity and a noncash investing activity. When real estate is purchased with borrowed funds, the borrower/buyer signs the mortgage documents and the payment for the real estate is sent by the lender directly to the seller of the real estate. The cash is never recorded in the borrower’s accounts. Thus, the company acquired land, an investing activity, without any cash payment; and it became liable for a mortgage, a financing activity, without receiving any cash. Since the company did not pay or receive any cash, the two activities will not be included in the line items on the statement of cash flows. However, they must be disclosed in the statement of cash flows as noncash financing and investing activities. 12 c – Cash provided by operating activities is: + + − − 436 Net income Depreciation Decrease in accounts receivable Decrease in accounts payable Increase in inventory Net cash provided by operating activities $ 456,900 45,600 11,560 (2,155) (7,620) $504,285 © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. CMA Part 1 Answers to Questions 13 a – Net cash flow from operating activities is: Minus: Plus: Plus: Plus: Minus: Net income Increase in accounts receivable Decrease in inventory Increase in accounts payable Depreciation expense Gain on the sale of available-for-sale debt securities Net cash provided by operating activities $ 2,000,000 (300,000) 100,000 200,000 400,000 (700,000) $1,700,000 14 c – Cash and cash equivalents include all cash items and short-term investments with a maturity of 3 months or less when acquired. In this question the cash in the checking account ($50,000) is cash, the balance in the money market account ($100,000) is a cash equivalent, and the Treasury bond purchased on November 15, 20X0 with a maturity date of January 31, 20X1 ($300,000) is also a cash equivalent, for a total of $450,000. The Treasury bill purchased November 1, 20X0 with a maturity date of February 28, 20X1 is a short-term investment, but it is not a cash equivalent, because when it was purchased by Senger, it was scheduled to mature in four months. Cash equivalents are defined as very short-term, highly liquid investments that mature in three months or less from the date acquired by the company. 15 d – The Treasury bond with a maturity date of January 31, 20X1 was a highly liquid investment with a maturity of three months or less when it was purchased on November 15, 20X0, and therefore, it is a cash equivalent. The purchase (and sale) of a cash equivalent is not reflected on the statement of cash flows as either a cash inflow or a cash outflow. However, its balance will be included in the ending balance of cash, cash equivalents, and restricted cash on the statement of cash flows. 16 d – All of the securities except treasury bonds are examples of cash equivalents. Treasury bonds are long-term U.S. government securities, so unless one was purchased less than three months before its maturity date, a treasury bond does not qualify as a cash equivalent. 17 b – In order to determine the credit loss expense for the period using the percentage of receivables method, the first thing to do is calculate the required ending balance in the allowance account. Using the aging schedule for the calculation of the ending balance in the allowance account requires making four calculations, one for each of the different “ages” of receivables. By multiplying the amount in each category by the percentage estimated to be expected credit losses and summing the results, the required ending balance in the allowance account is calculated as follows: ($730,000 × 0.01) + ($40,000 × 0.06) + ($18,000 × 0.09) + ($72,000 × 0.25) = $29,320. $29,320 is the amount that should be in the allowance account at the end of the year as a credit balance. Since the account presently has a debit balance of $14,000, a credit of $43,320 ($29,320 + $14,000) will be needed in order to change the balance from a debit balance of $14,000 to a credit balance of $29,320. The corresponding debit will be to credit loss expense. 18 d – Writing off an account when the allowance method is used has no effect on either the income statement or on current assets. The journal entry to write off the account is a credit to accounts receivable and a debit to the allowance account, so the net effect on net accounts receivable and on total current assets is zero. Furthermore, the writeoff does not affect any income statement account at all. An income statement account (credit loss expense) is debited when the allowance is booked, not when an account is written off. 19 a, Percentage of Sales method: Ending balance in the allowance account ($1,550), credit loss expense $1,800. Credit loss expense is calculated as $60,000 credit sales × 0.03 = $1,800. The ending balance in the allowance account after the credit loss expense for the year is recorded is calculated as ($750) credit balance + 1,000 written off + ($1,800) credit loss expense = ($1,550) credit balance. b, Percentage of Receivables method: Ending balance in the allowance account ($840), credit loss expense $1,090. Ending accounts receivable before the credit loss expense for the year is recorded is $14,000, calculated as follows: $10,000 beginning A/R balance + $60,000 credit sales − $55,000 collections on credit sales − $1,000 written off = $14,000 ending A/R balance. Since 6% of ending accounts receivable are deemed credit losses, the ending balance in the allowance account needs to be $14,000 × 0.06, which equals ($840), a credit balance. The balance in the allowance account before the credit loss expense for the year is recorded is ($750) credit balance + $1,000 written off = $250, a debit balance. The balance in the allowance account needs to be a credit balance of ($840). Therefore, the credit to the allowance account needs to be a credit of $250 + $840, or $1,090. The credit loss expense is the other side of the entry, or a debit to credit loss expense of $1,090. Using the allowance for credit losses on receivables T-account to calculate both the required ending balance in the allowance account (and the ending balance after recording the credit loss expense) and credit loss expense: © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. 437 Answers to Questions CMA Part 1 Allowance for Credit Losses - Percentage of Receivables (credits in parentheses) (1) Beginning balance: (750) (2) Amount actually written off as credit losses for the year: 1,000 (3) Collection losses: 0 of previously written-off credit (4) Amount to be charged as credit loss expense for the period (residual figure): (750) + 1,000 = ending debit balance of 250 in allowance account before adjustment for credit loss expense. To change a debit balance of 250 to a credit balance of (840), a credit is needed in the amount of (1,090). (5) Ending balance calculated using ending A/R: Ending A/R (calculated above) 14,000 × 0.06 = (840) 20 a – A lot of unnecessary information is given in this problem. Davis Corporation uses the percentage of sales method to determine credit loss expense. Therefore, the entry to record credit loss expense is simply the percentage of current sales determined to be appropriate for credit loss expense, and that is 3%. Credit sales during the year totaled $10,000,000, and 3% of $10,000,000 is $300,000. 21 a – When the last-in, first-out inventory cost flow assumption is being used, the most recently-purchased inventory items will be assumed to be the first ones sold. Thus, the most recently incurred costs will be allocated to cost of goods sold while the earliest costs are allocated to ending inventory. 22 c – In a period of rising prices, the last-in, first-out cost flow assumption usually provides the best matching of expenses against revenues because the cost allocated to sold units is the most recently incurred cost for each item of inventory. 23 c – If more inventory is purchased at the end of the year when prices are rising and the last-in, firstout inventory cost flow assumption is being used, the cost of the sales that take place at year-end will be increased because the most recently purchased inventory items will have the highest cost, and those are the items assumed to have been sold when LIFO is being used. The increase in cost of sales will result in a decrease in net income. 24 b – In periods of rising costs, the last-in, first-out cost flow assumption will result in higher cost of sales because the cost of the most recently purchased inventory items, at the current higher price, will be used as the cost of the goods sold. 25 b – The first-in, first-out method will yield the same ending inventory value and cost of goods sold whether a perpetual or a periodic system is used because under FIFO, the oldest unit is the unit sold. Regardless of whether the company determines the oldest unit at the end of the period or after each sale, the oldest unit is always the oldest unit. 26 d – Net income next year will be understated because net income this year will be overstated. Income this year will be overstated because cost of goods sold this year will be understated. The formula for cost of goods sold is: Beginning inventory + Purchases = Cost of goods available for sale − Ending inventory = Cost of goods sold If ending inventory is overstated at the end of this year, cost of goods sold will be understated for this year and this year’s net income will be overstated. Because ending inventory is overstated at the end of this year, beginning inventory for next year will also be overstated. As a result, cost of goods sold will be overstated next year, and so net income next year will be understated. However, retained earnings will not be understated next year because the error is a self-correcting error. 438 © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. CMA Part 1 Answers to Questions 27 b – Because of the way cost of goods sold is calculated (see answer to previous question), if ending inventory is overstated, cost of goods sold will be understated. If cost of goods sold is understated, net income will be overstated. 28 $0 and $1,000 – To determine whether a fixed asset has been impaired, compare the book value with the undiscounted sum of expected future cash flows from the asset. In question a) the future cash flows of $5,000 are greater than the book value of the asset ($4,500), so the asset is not impaired and no impairment loss needs to be recognized. In question b), however, the asset is impaired since the future cash flows of $3,000 are less than the $4,500 book value. In this case the asset needs to be written down from its book value ($4,500) to its fair value ($3,500), for a $1,000 impairment loss. 29 d – The assurance warranty expense is the total value of the sales multiplied by the estimated future assurance warranty costs: $3,000,000 × 4% = $120,000. 30 b – Deferred tax liability represents the accumulated difference between the income tax expense reported on the firm’s books and the income tax actually paid. 31 c – On the declaration date of January 31, Reese will record a gain on the 1,000 shares of Alpha stock of $25 per share, or $25,000, increasing the carrying value of the asset by the same amount. Also on January 31, Reese will record a debit to retained earnings for the fair value of the stock to be distributed ($100 per share × 1,000 shares, or $100,000) and a credit for the same amount to property dividends payable. Thus, the amount charged to retained earnings as a result of this property dividend declaration will be $100,000. 32 b – On December 1, the date of the property dividend’s declaration, Noble will record a gain of $50,000, increasing the asset account for the equity investment by the same amount. Also on December 1, Noble will record a debit to retained earnings for the fair value of the stock to be distributed ($150,000) and a credit for the same amount to property dividends payable. Even though the fair value of the Multon stock had increased by December 31, the balance in the property dividends payable account is not adjusted to the Multon stock’s fair value as of December 31. Thus, the balance shown on Noble’s statement of financial position at December 31 as property dividends payable will be $150,000. 33 a – When a stock dividend is declared but not immediately distributed, the future stock dividend is not recorded as a dividend payable but rather as “common shares – issuable as a dividend,” an account in the equity section of the balance sheet. Therefore, when the dividend is declared, no liability is recorded. 34 c – The first step is to find how much cash in dividends were declared for the year, then use that to find how much in cash dividends were actually paid during the year. The retained earnings account began the year with a balance of $100,000 and ended the year with a balance of $125,000. Net income for the year increased retained earnings by $40,000 to a balance of $140,000. The stock dividend in the amount of $8,000 was almost certainly a small stock dividend, so the full $8,000 was debited to retained earnings, reducing retained earnings to $132,000. The only other transaction(s) that would have affected retained earnings would have been the declaration of cash dividends, which reduce retained earnings. Thus, dividends declared must have been $7,000 ($132,000 − $125,000 ending balance). The question says that dividends payable decreased by $5,000 during the year. That means that $5,000 in dividends declared during the previous year were paid during the current year and that the full $7,000 of dividends declared during the current year were also paid during the current year (that is, no dividends were payable at year end). Therefore, the total cash dividends paid during the year were $5,000 declared during the previous year + $7,000 declared during the current year, which equals $12,000. T-accounts: Retained Earnings Dr Beginning balance Dividends Payable 100,000 Net income Dr Cr 40,000 Beginning balance Cash dividend paid Stock dividend declared 8,000 Cash dividend declared Cash dividend declared 7,000 Cash dividend paid Ending balance 125,000 Ending balance © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. Cr 5,000 5,000 7,000 7,000 0 439 Answers to Questions CMA Part 1 35 d – Note that the question asks for the amount of revenue that will be reported in 20X3, not the amount of gross profit. Total revenue on the contract was $100,000. At the end of 20X2, construction was 37.5% complete ($30,000 ÷ [$30,000 + $50,000]), so the revenue recognized for 20X2 was $37,500. At the end of 20X3, construction was completed because the estimated cost to complete as of the end of 20X3 was zero. Therefore, the $62,500 remaining revenue on the contract—$100,000 minus the $37,500 recognized in 20X2—will be recognized in 20X3. 36 c – This question and the following two use the formula for the recognition of revenue and gross profit over time. The formula is: × = − = Estimated Gross Profit Percentage Satisfied Total Gross Profit to be Recognized to Date Profit Previously Recognized Gross Profit to Recognize This Period In 20X0, $400,000 of costs had been incurred of an estimated $1,200,000 in total costs. Therefore, the performance obligation is 1/3 satisfied, so 1/3 of the estimated gross profit of $300,000 ($1,500,000 − $1,200,000) is to be recognized to date, or $100,000. Since 20X0 is the first year of the project, no revenue or gross profit has yet been recognized. Therefore, Carefree should recognize gross profit of $100,000 for 20X0. 37 a – In 20X1, the performance obligation is 6/13 ($600,000 ÷ $1,300,000) satisfied. At this point, the total amount of gross profit that should be recognized to date on the contract is $92,308: ([$1,500,000 − $1,300,000] × 6/13). However, $100,000 of gross profit was recognized in 20X0. So, using the last part of the formula, the $100,000 that was recognized in 20X0 is subtracted from the total amount of profit that should be recognized to date, and the result is a loss for 20X1. $92,308 − $100,000 = $(7,692). This loss for 20X1 is not a loss on the whole contract, at least not yet, but rather the de-recognition of some of the gross profit that had been over recognized in the prior period. 38 a – In 20X2, something happened to the project and it went from an estimated gross profit to an estimated loss of $50,000 ($1,500,000 − $1,550,000). The formula can still be used, but remember that losses are always 100% recognized. Therefore, a total loss of $50,000 needs to have been recognized on the project by the end of 20X2. However, the company already recognized $92,308 of gross profit to date, so in order to change that to a loss of $50,000, it must recognize a $142,308 loss in 20X2 ($50,000 + $92,308). 39 b – As of the end of Year 2, estimated gross profit on the contract was $180,000 ($700,000 contract price minus [$390,000 cumulative costs incurred to date + $130,000 estimated cost to complete]). The project was 75% satisfied ($390,000 ÷ [$390,000 + $130,000]). Therefore, the total gross profit that should be recognized to date through Year 2 is 75% of $180,000, or $135,000. $65,000 in gross profit was recognized in Year 1, so the amount of gross profit to be recognized in Year 2 is $135,000 − $65,000, or $70,000. 40 d – Planning does not enable selection of personnel for open positions. 41 b – The statement that formal plans can act as a constraint on the decision-making freedom of managers and supervisors is a true statement. However, that is a justification for not making the plan too formal. It is not a justification for formalizing phases of the planning process. If plans are too formal, they prevent managers from pursuing new opportunities or making necessary decisions as a result of changes in the environment from what was planned. 42 b – Strategic plans are long-term, and therefore strategic analysis does not include the product mix for the current year. The target production mix and schedule to be maintained during the year is a short-term planning matter. 43 b – The objectives of the company must be determined before anything else can be set. 44 c – Evaluation of environmental issues that could affect the company’s profitability is not included in a company’s internal analysis process because this type of analysis is not internal, but rather a factor that uncovers external opportunities and threats. 45 d – Contingency planning is preparation for “what if” events that are typically external and unpredictable. It produces alternatives that will prepare the organization to respond nimbly if required. This scenario planning is particularly important for companies that can be impacted by new technologies, changing government regulations or entry of competitors into the marketplace. Even though contingency planning can be expensive because it involves developing multiple plans or alternatives, it often leads to greater savings than the cost of the planning should unforeseen events occur. 440 © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. CMA Part 1 Answers to Questions 46 c – The contribution per machine hour for product A is $95 ÷ 4, or $23.75. The contribution per machine hour for product B is $55 ÷ 2.5, or $22. Assuming customer demand is adequate to permit the company to sell all the product A it can manufacture, the company should produce product A because its contribution per machine hour required for the production is higher than that of product B. 47 d − The support of top management is critical to gain the support of lower-level managers, and the support of lower-level managers is critical in order to gain the support of the affected employees. Without this support from above, the budget effort will be wasted because personnel will not take the process seriously. 48 b – Production doubles 3 times (from 1 to 2, from 2 to 4, and from 4 to 8). With the cumulative averagetime learning model, the estimated total number of direct labor hours required to produce a total of eight units is 100 × (2 × 0.70) × (2 × 0.70) × (2 × 0.70) = 274.4 hours. 49 d – With the cumulative average time learning model, whenever the total quantity of units produced doubles, the cumulative average time per unit required for all the units produced is X% of the cumulative average time per unit required at the previous production-doubling level, where X% represents the learning rate. This question gives labor costs instead of labor time; however, since the question also asks for total labor cost, the costs can be used in the same way as time would be used. The question says that the average labor cost for the first batch is $120 per unit and the cumulative average labor cost after the second batch (the first doubling) is $72 per unit. Using this information, the learning rate is calculated at 60% (72 ÷ 120 = 0.60). If the average cost per unit for the first two batches is $72, then the average cost per unit for all four batches (after the fourth batch – the second doubling) is $72 × 0.6, or $43.20. Since each batch contains 100 units, 4 batches contain a total of 400 units. If the average cost per unit is $43.20, the total cost for 400 units (4 batches) is $43.20 × 400, or $17,280. 50 c – The expected value is a weighted average of the possible values, with the probabilities as the weights. Thus, the expected percent defective is (0.02 × 0.30) + (0.03 × 0.50) + (0.04 × 0.20) = 0.0290 or 2.90%. 51 a − At all times, the budget covers a set number of months, quarters, or years into the future. When a rolling budget is used, the month or quarter just completed is dropped from the budget and a new month or quarter’s budget is added on to the end of the budget. At the same time, the other periods in the budget can be revised to reflect any new information that has become available. Thus, the budget is continuously being updated and always covers the same amount of time in the future. A rolling budget is also called a continuous budget. 52 d – Activity-based budgeting enables better identification of resource needs, enables linking of costs to outputs, and enables identification of budgetary slack. While it may reduce some planning uncertainty, reduction of planning uncertainty is not guaranteed; therefore, d is the best answer. 53 c – Top management must be involved in the budgeting process and its involvement includes using the budget as a means to communicate company goals. 54 b – If top management sets the budget levels without any input from others in the company, those charged with fulfilling the budgeted goals will not support the budget as their own. 55 d – The forecasted cash balance at the end of the second quarter is Beginning cash balance + Cash collections 2nd Quarter − Decrease in A/P − 2nd Quarter costs & expenses + Depreciation included in costs & expenses − Cash purchase of equipment + Cash received from sale of asset ($35,000 + $5,000) − Repayment of notes payable = Ending cash balance $ 36,000 1,300,000 (25,000) (1,200,000) 60,000 (50,000) 40,000 (66,000) $ 95,000 56 d – Selling and administrative budgets should be detailed enough to be useful, including an explanation of the underlying assumptions. These assumptions should be documented so that if they are changed it will be easier to adjust the affected budget figures. 57 b – The sales budget is the first budget that needs to be set because the production budget and all the other budgets for the company are derived from the sales budget. 58 a – A sales forecast for a full year does not need to take into consideration seasonal sales volume fluctuations in the same way as a monthly sales forecast would. © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. 441 Answers to Questions CMA Part 1 59 d – This question says, “In the budgeting and planning process . . . which one of the following should be completed first?” The strategic plan must be in place before any budgeting activities can occur. Therefore, even though the sales budget is the first budget that needs to be completed, in the budgeting and planning process the strategic plan comes before the sales budget. 60 b − The cash budget draws upon information from all the other budgets given as answer choices. Therefore, it should be prepared after those other budgets have been prepared. 61 a − The individual budgets that make up the operating and financial budgets are compiled into a budgeted income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows, which is the master budget. 62 b – The flexible budget amount for a single product is the standard cost per unit multiplied by the actual production volume. The budget calls for 144,000 units at a cost of $180,000, so the standard cost per unit is $1.25 ($180,000 ÷ 144,000). Actual production was 10,800 units, so the flexible budget amount is $13,500 (10,800 units × $1.25 per unit). 63 c – In order to solve this problem, determine the total fixed costs and the variable costs per unit. The total fixed costs are $200,000 ($100,000 each of manufacturing and selling costs). The variable costs in the 100,000-unit budget total $450,000, so the standard variable cost is $4.50 per unit ($450,000 ÷ 100,000 units). Therefore, to produce 110,000 units the company will incur $495,000 in variable costs ($4.50 × 110,000 units) and $200,000 in fixed costs for total costs of $695,000. 64 c – Much of the information given in this question is not needed to determine the correct answer. The shipping cost function is provided as well as the total pounds actually shipped (12,300 pounds) to use in the function. Putting this information into the formula results in: $16,000 + ($0.50 × 12,300) = $22,150. 65 b – The flexible budget amount is the budgeted contribution margin per unit multiplied by the actual sales volume, minus the budgeted fixed costs. Note that fixed costs in the flexible budget are the same as fixed costs in the static budget because fixed costs do not change with changes in activity as long as the activity remains within the relevant range. The budgeted contribution margin at a sales volume of 180,000 units is $975,000 ÷ 150,000 × 180,000 = $1,170,000. $1,170,000 minus $250,000 fixed overhead and minus $500,000 fixed selling and administrative expenses equals flexible budget net income for the month of $420,000. 66 c – This question asks for the budgeted amount of direct material that needs to be purchased during the third quarter. Purchases made during the third quarter need to cover the amount required for production during the third quarter and the amount of direct materials inventory necessary to begin the fourth quarter with the required amount of 30% of the fourth quarter’s usage requirement. The calculation of Purchases must also consider the amount of direct materials on hand at the beginning of the third quarter. The basic inventory formula is: Beginning Inventory + Purchases − Usage = Ending Inventory. With three of the four amounts, the fourth can always be determined. For this question, Purchases is the unknown to solve for. Information for the other three amounts can be derived from the information given in the question. The beginning inventory for the third quarter is 30% of the third quarter’s usage requirement. The third quarter’s usage requirement is 34,000 × 3, or 102,000 units of direct materials. Thus, the beginning inventory of direct material for the third quarter is 102,000 × 0.30, or 30,600. Third quarter usage, as calculated above, is 102,000 units of direct material. The ending inventory for the third quarter is the same as the beginning inventory for the fourth quarter. The beginning inventory for the fourth quarter needs to be 30% of the usage requirement for the fourth quarter. Planned production for the fourth quarter is 48,000 units, so materials requirements for those will be 48,000 × 3, or 144,000 units of direct materials. Thus, the beginning inventory for the fourth quarter needs to be 144,000 × 0.30, or 43,200 units, and this is the ending inventory for the third quarter. With three of the four amounts for the inventory formula, Purchases for the third quarter can be calculated. Beginning Inventory + Purchases − Usage = Ending Inventory Let P stand for Purchases. The equation is: 30,600 + P − 102,000 = 43,200. P = 114,600. 67 c – The inventory formula in units, which can be used for either finished goods or direct materials inventory, is: Beginning Inventory + Units Produced or Purchased − Units Sold or Used = Ending Inventory 442 © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. CMA Part 1 Answers to Questions With three of these amounts, the fourth amount can be calculated. To answer this question, it is necessary to calculate what the production needs to be during July, August, and September in order to end the month of September with the required number of units in ending finished goods inventory. Beginning finished goods inventory is 150,000 units. The number of units that will be sold during the threemonth period and the ending inventory level need to be calculated, and then Beginning Inventory, Units Sold, and Ending Inventory can be used to calculate Units Produced. The required ending inventory on September 30 needs to be 80% of the next month’s estimated sales, so October’s budgeted sales are needed. If July’s budgeted sales are 200,000 units and the company expects a growth rate in sales of 5% per month, October’s budgeted sales will be 200,000 × 1.05 × 1.05 × 1.05, or 231,525. Therefore, the September 30 ending finished goods inventory needs to be 231,525 × 0.80, or 185,220 units. Sales during July, August, and September are budgeted as follows: July budgeted sales are 200,000 units. August budgeted sales are 200,000 × 1.05, or 210,000 units. September budgeted sales are 210,000 × 1.05, or 220,500 units. Therefore, the total number of units budgeted to be sold during July, August, and September is 200,000 + 210,000 + 220,500, or 630,500. Now Berol Company’s production requirement in units of finished product for the three-month period ending September 30 can be calculated, as follows: Beginning Inventory + Units Produced − Units Sold = Ending Inventory Let X stand for Units Produced. The equation is: 150,000 + X − 630,500 = 185,220 X = 665,720 units that must be produced during July, August, and September. 68 c – The question says to assume that July, August, and September production will be 600,000 units. Each unit requires 4 pounds of direct materials, so to produce 600,000 units, 2,400,000 pounds (600,000 × 4) of direct materials will be needed. Beginning direct materials inventory is 800,000 pounds. Ending direct materials inventory needs to be 25% of the direct materials used during the three-month period of July through September, or 2,400,000 pounds × 0.25, which is 600,000 pounds. Beginning Inventory + Units Purchased − Units Used in Production = Ending Inventory Let X stand for Units Purchased. The equation is: 800,000 + X − 2,400,000 = 600,000 X = 2,200,000 pounds of direct materials to be purchased. However, the question does not ask for the number of pounds to be purchased; rather, it asks for the estimated cost to purchase direct materials. The estimated cost to purchase 2,200,000 pounds of direct materials at $1.20 per pound = $2,640,000. 69 b – This is a very long question with only a few important pieces of information. In January, the production will be equal to 1.5 times the expected sales in February. Expected February sales are 36,000; therefore, in January the company will produce 54,000 units (36,000 × 1.5). 70 b – In February the production will be equal to 50% of March sales. March sales are expected to be 33,000, so February’s production will be 16,500 units. The variable cost per unit is $7 ($3.50 + $1 + $2 + $0.50), so total variable costs will be 16,500 × $7, or $115,500. Adding this figure to the $12,000 of fixed costs produces a total production cost of $127,500. 71 c – The basic inventory formula for any purpose is: Beginning Inventory + Additions to Inventory − Inventory Used = Ending Inventory. Beginning inventory needs to be 40% of the amount Rokat expects to sell during August, or 40% of 2,500, which is 1,000 units. Ending inventory needs to be 40% of the amount Rokat expects to sell during September, or 40% of 2,100, which is 840. The company expects to sell 2,500 units during August. Letting P stand for Units Produced (additions to inventory), the formula is: 1,000 + P − 2,500 = 840 P = 2,340 © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. 443 Answers to Questions CMA Part 1 2,340 tables will need to be produced during August. 72 b – Four table legs are required for each table produced. The basic inventory formula is: Beginning Inventory + Additions to Inventory − Inventory Used = Ending Inventory. August production is 1,600 tables, and 1,600 multiplied by 4 legs per table equals 6,400 table legs that will be needed for August production. August beginning inventory is 4,200 legs. August ending inventory is 60% of the amount required for September production. September production is 1,800 tables, and the number of table legs needed for September production will be 1,800 × 4, or 7,200 legs. Thus, August ending inventory will be 60% of 7,200, or 4,320 legs. Letting P stand for legs purchased, the formula is: 4,200 + P − 6,400 = 4,320 P = 6,520 6,520 table legs will need to be purchased during August. 73 a – This mathematical calculation can be performed in several ways. One method is as follows: 1,800 units will be produced and each table requires 20 minutes of labor, so 36,000 minutes (1,800 × 20) will be required. 36,000 minutes divided by 60 minutes in an hour equals 600 direct labor hours required. Each employee works 160 hours a month (40 hours × 4 weeks), so 3.75 employees will be needed 600 ÷ 160). 74 d – The first thing to do is determine the number of bicycles and tricycles to be produced because the total production determines how much of component A19 is needed, since 2 units of A19 are used in each bicycle and each tricycle. Use the basic inventory formula for finished goods to determine how many bicycles and tricycles will be produced. Then the basic inventory formula can be used for direct materials to find the number of units of A19 that will need to be purchased. The basic inventory formula for any purpose is: Beginning Inventory + Additions to Inventory − Inventory Used = Ending Inventory For direct materials inventory, “Additions to Inventory” means Purchases and “Inventory Used” means amount used in production. Begin with finished goods inventory. Tricycles and bicycles both use 2 units of A19, so their A19 requirements do not need to be calculated separately. Beginning inventory of tricycles is 800 and beginning inventory of bicycles is 2,150, for a total of 2,950. Sales of tricycles are 96,000 and sales of bicycles are 130,000 for a total of 226,000. Ending inventory of tricycles is 1,000 and ending inventory of bicycles is 900, for a total of 1,900. Beginning Inventory + Number of Units Produced − Sales = Ending Inventory 2,950 + Number of Units Produced − 226,000 = 1,900 Number of Cycles (tricycles and bicycles) Produced = 224,950 Use the basic inventory formula for direct materials in order to calculate the number of units of A19 needed to be purchased. Beginning inventory of A19 is 3,500. Each cycle requires 2 units of A19. Therefore, the number of units of A19 needed for production will be 449,900 (224,950 × 2). Ending inventory of A19 is 2,000. Beginning Inventory + Purchases − Amount Used in Production = Ending Inventory 3,500 + Purchases − 449,900 = 2,000 Purchases = 448,400 The unit cost of A19 is $1.20. Therefore, the budgeted dollar value of purchases of A19 is 448,400 × $1.20, or $538,080. Note: If the number of units of A19 needed per finished unit had been different for tricycles and bicycles, it would have been necessary to calculate each product’s production requirements separately and then multiply the production of each product by the number of A19s required for that product. Then the total number of A19s needed for production of both products would have been the number needed for tricycles plus the number needed for bicycles. 75 b – The economic order quantity is the most economical amount to order each time an order is placed to minimize ordering costs and holding costs. The economic order quantity for B12 is 70,000 units. If Wellfleet always orders 70,000 units of B12, the number of times the company should place an order for B12s will be the total number of B12s needed for production divided by 70,000. 444 © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. CMA Part 1 Answers to Questions The planned production of bicycles is 128,750 units and the planned production of tricycles is 96,200 units, calculated as follows, using the basic inventory formula: Bicycles: Beginning Inventory 2,150 + Units Produced – Units Sold 130,000 = Ending Inventory 900 Units Produced = 128,750 Tricycles: Beginning Inventory 800 + Units Produced – Units Sold 96,000 = Ending Inventory 1,000 Units Produced = 96,200 Each bicycle requires four B12s, while each tricycle requires one B12. Therefore, the total number of B12s required for production is (128,750 × 4) + (96,200 × 1) = 611,200. The beginning inventory of B12s is 1,200 and the ending inventory is 1,800. The basic inventory formula can now be used to determine the number of B12s to be purchased: Beginning Inventory + Units Purchased − Units Used in Production = Ending Inventory Let P stand for Units Purchased. The equation is: 1,200 + P − 611,200 = 1,800 P = 611,800 Since 611,800 units of B12 need to be purchased, divide 611,800 by the order size of 70,000 to find the number of times Wellfleet will purchase B12s: 611,800 ÷ 70,000 = 8.74. Therefore, 9 orders will need to be placed in order to receive the required amount of B12. The company will have a few extra units, since the division does not work out evenly. But if the company were to order only 8 times, it would not have enough B12s to complete all of its planned production for the year. 76 c – To calculate collections expected during the third calendar quarter, analyze each month in the quarter to determine the amount of that month’s sales to be collected and the amount of the previous month’s sales to be collected. The company collects 50% of the credit sales in the month of the sale and 45% in the following month. Therefore, the collections during the third quarter are: July 50% of current month’s sales 45% of previous month’s sales Total $70,000 $54,000 $ 124,000 August 80,000 63,000 143,000 September 75,000 72,000 147,000 $414,000 77 b – This question is similar to the previous question, except for a small and critical difference. In the previous question, 50% of the sales were collected in the month of the sale, 45% in the month after, and 5% were never collected. In this question, 5% are never collected, and 60% of the amount to be collected is collected in the month of the sale and 40% of the amount to be collected is collected in the month after the sale. Notice the difference: in this question it is not 60% of the total credit sales that will be collected during the month of sale but rather 60% of the total credit sales that will be collected that will be collected during the month of sale. It is essential to recognize which percentage of which quantity is being collected. Therefore, in December Noskey will collect 40% of 95% of the November credit sales. November credit sales were $240,000. Of this amount, 95% or $228,000 will be collected. Of this amount, 40% will be collected in December, or $91,200. 78 c – The budgeted cash receipts in January will include the cash collected from December and January credit sales as well as the cash sales from January. January cash sales were $60,000. Collections from December sales will be $136,800 ($360,000 × 0.95 × 0.4), and collections from January credit sales will be $102,600 ($180,000 × 0.95 × 0.6). In total, $299,400 will be collected in January ($60,000 + $136,800 + $102,600). 79 c – Since the question states that Raymar intends to maintain a minimum balance of $100,000 at the end of each month by either borrowing for deficits below the minimum balance or investing excess cash, assume that the company’s balance of cash at the end of March is $100,000. Thus, the beginning balance for April is also $100,000. The ending balance for April, before any borrowing or investing, will be the beginning balance adjusted by the month’s activity. To determine the month’s activity, determine the cash collections for April: 50% of April sales and 50% of March sales (or $25,000 + $20,000 = $45,000) will be collected in April. © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. 445 Answers to Questions CMA Part 1 Next, determine the disbursements for April: 75% of April A/P and 25% of March A/P (or $30,000 + $7,500 = $37,500) will be paid on accounts payable in April. Other disbursements are paid in the month they occur, and for April they are: $70,000 for payroll plus $30,000 of other disbursements, totaling $100,000 in disbursements other than accounts payable. Total cash receipts are $45,000 and total cash disbursements are $137,500. Subtracting the amount of cash outflows from cash inflows results in a $92,500 net cash deficit in the month’s activity. Therefore, the ending cash balance before any borrowing is $100,000 − $92,500, or $7,500. The company needs to increase that amount to at least $100,000. Since borrowings for cash deficits must be made in $10,000 increments, the company needs to borrow $100,000 to cover the $92,500 cash deficit and bring the ending cash balance from $7,500 to its required minimum of $100,000. The ending cash balance will actually be $107,500 after $100,000 is borrowed, but the extra $7,500 in the cash account is unavoidable because of the $10,000 incremental borrowing requirement. 80 d – In the previous question, the April ending cash balance was forecasted to be $107,500, funded by $100,000 of borrowing. Therefore, the company will need to pay $1,000 of interest in May ($100,000 × [12% ÷ 12]) for the funds borrowed during April. Next, determine the cash inflows and outflows for May. Cash collections in May are 50% of the April and May sales: (50% × $50,000) + (50% × $100,000) = $75,000. Accounts payable paid in May are 75% of May’s A/P and 25% of April A/P: ($40,000 × 75%) + $40,000 × 25%) = $40,000. Other disbursements total $61,000 ($50,000 for payroll + $10,000 in other disbursements + $1,000 in interest for the funds borrowed during April). Subtracting the total disbursements from the collections in May results in a $26,000 negative cash flow: $75,000 − $40,000 − $61,000 = ($26,000). At the beginning of the month, the company had a cash balance of $107,500. $107,500 minus the $26,000 negative net cash flow during May results in a May ending cash balance before any borrowing of $81,500. However, the company needs to end the month with a cash balance of $100,000; therefore, it is $18,500 short. Since borrowings for cash deficits must be made in $10,000 increments, the company must borrow $20,000 to cover the $18,500 cash deficit for May and end the month with at least $100,000 in cash. It will thus end the month of May with $101,500 in cash: $107,500 − $26,000 + $20,000 = $101,500. 81 c – Top management would not be likely to be involved in setting budget standards for production because setting budget standards is an activity best done by those more directly involved with budgetrelated matters. 82 d – Standard costing systems are often and best used together with a flexible budget. By using standard costs, the firm can prepare the flexible budgets that enable better analysis at the end of the period. 83 d – The actual sales volume of the product will not impact the materials efficiency variance. The materials efficiency variance, also called the direct materials quantity variance, is a manufacturing input variance that measures the difference in cost between the actual material used in production at the standard price and the standard usage allowed for the level of actual output at the standard price. It is not affected by the amount of the finished good that is sold. 84 b – The total standard cost allowed for the actual output is $60,000. Two units of raw material are allowed for each unit produced and the company produced 12,000 units. Therefore, the standard quantity allowed for the actual output is 12,000 × 2, or 24,000 units. The standard price for one unit of material is $60,000 ÷ 24,000 units of direct materials, or $2.50 per unit of direct materials. 85 d – For this question, use the materials quantity variance formula and solve for AQ. The variance formula is (AQ − SQ) × SP. SQ can be calculated because the company produced 12,000 units, and two units of raw materials are required for each unit of output. Therefore, the standard quantity for the actual output is 24,000 units. The standard price per unit of raw material can also be calculated because the standard cost allowed for the actual output is $60,000. Since the standard quantity for the actual output is 24,000 units, the standard price per unit of raw materials is $60,000 ÷ 24,000, or $2.50. The quantity variance is given as $2,500 unfavorable. Therefore, the formula is: (AQ − 24,000) × $2.50 = $2,500. Solving for AQ: 2.5AQ − 60,000 = 2,500 2.5AQ = 62,500 446 © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. CMA Part 1 Answers to Questions AQ = 25,000 units 86 c – The formula for calculating the materials price variance is (AP − SP) × AQ. The actual price for raw materials is $105,000 ÷ 35,000 units in inventory, or $3.00 per unit. The standard price is $2.50 per unit of raw materials ($60,000 standard cost for material allowed for the output ÷ [12,000 units actually produced × 2 units of materials per unit produced]). The Actual Quantity in the formula is the actual quantity of the raw materials that were used in producing the 12,000 finished units. It is not the actual quantity of product produced, nor is it the standard quantity of materials for the actual quantity produced. To calculate the price variance, the number of units of raw material actually used in production is needed, but the question does not provide that number. However, the question states that there is an unfavorable quantity variance of 2,500. Therefore, to determine the number of units of materials actually used, use the quantity variance formula and solve for AQ. The quantity variance formula is (AQ − SQ) × SP. Since the question indicates that the materials standard is 2 units of raw materials for each unit produced, the standard quantity of materials for 12,000 units is 24,000 units. The actual quantity is not yet known. The standard price is $2.50 per unit of raw material ($60,000 standard cost for material allowed for the output ÷ [12,000 units actually produced × 2 units of materials per unit produced]). The quantity variance is 2,500 Unfavorable. The formula is: (AQ − 24,000) × $2.50 = $2,500 Solving for AQ: 2.5AQ − 60,000 = 2,500 2.5AQ = 62,500 AQ = 25,000 Next, input the actual quantity of materials used into the materials price variance formula and calculate the materials price variance, (AP − SP) × AQ: ($3.00 − $2.50) × 25,000 = $12,500 Unfavorable 87 b – The price variance formula is (AP – SP) × AQ. Entering the figures from the question into the formula, results in ($0.75 − $0.72) × 4,100 = $123 Unfavorable. (Remember for the price variance to use the number of units used in production, unless the problem asks for the purchase price variance.) 88 d – To solve for the direct materials usage variance, use the following formula: (AQ – SQ) × SP. The AQ is the actual quantity of the direct materials used, and the SQ is the standard quantity of direct materials allowed for the actual output. The standard price is $3.60 per pound and the standard quantity required to produce the actual quantity of output is 110,000 (22,000 units × 5 pounds per unit). The actual quantity used is 108,000; therefore, the formula is (108,000 – 110,000) × $3.60 = $(7,200) Favorable. 89 a – To solve for the direct labor rate variance, use the following formula: (AP – SP) × AQ. The actual quantity of labor hours is 28,000 and the standard rate is $12.00 per hour. The actual rate is calculated by dividing the actual cost ($327,600, which is 90% of the total labor cost of $364,000) by the actual hours worked (28,000). The result is an actual labor rate of $11.70 per hour. Inputting these numbers into the formula results in ($11.70 − $12.00) × 28,000 = $(8,400) Favorable. 90 b – To solve for the direct labor usage (efficiency) variance, use the following formula: (AQ – SQ) × SP. The AQ is the actual number of direct labor hours used, and the SQ is the standard number of direct labor hours allowed for the actual output. The standard price is $12.00 and the actual number of direct labor hours worked is 28,000. The number of direct labor hours allowed for the actual level of output is 27,500 (22,000 units × 1.25 hours per unit). Putting these numbers into the formula results in (28,000 – 27,500) × $12 = $6,000 Unfavorable. 91 b – If the company has an unfavorable materials usage variance, then more materials were used in production than should have been used. An unfavorable materials usage variance may be caused by inferior materials that created the need to discard the unusable materials and start over. Thus, an unfavorable variance in materials usage may in turn cause more labor hours to be used in order to handle and process the additional materials. Therefore, the unfavorable materials usage variance may also cause an unfavorable direct labor efficiency variance. 92 d – The materials mix variance equals the actual total quantity used multiplied by the difference between the weighted average standard price for the actual mix per unit of direct materials, which in this question is kilogram (waspAM) and the weighted average standard price for the standard mix per kilogram (waspSM). The weighted average total standard price for the actual mix is (21,000 × $0.75) + (14,000 × $0.90) = $28,350, and the weighted average standard price per kilogram for the actual mix is $0.81 ($28,350 ÷ 35,000 kg). The weighted average standard price for the standard mix is $0.80 per kilogram ($240 standard total cost per batch ÷ 300 standard total kg per batch). The mix variance is ($0.81 − $0.80) x 35,000 = $350 Unfavorable. © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. 447 Answers to Questions CMA Part 1 93 b – The materials yield variance equals the weighted average standard price for the standard mix per unit multiplied by the difference between the actual total quantity used and the standard total quantity for the actual output achieved. The weighted average standard price for the standard mix is $0.80 per kg ($240 standard total cost per batch ÷ 300 standard total kg per batch). The actual total quantity used is 35,000. The standard total quantity for the actual output achieved is 300 kg per batch × 110 batches = 33,000 kg. Therefore, the yield variance is (35,000 – 33,000) x $0.80 = $1,600 Unfavorable. 94 b – The variable overhead efficiency variance is essentially a quantity variance, and it determines the amount of the total variance caused by a different usage of the allocation base than was expected. The allocation base used in this question is direct labor hours. The variable overhead efficiency variance is closely related to efficiency or inefficiency in the use of whatever allocation base is used to apply the variable overhead. For example, if variable overhead is applied on the basis of direct labor hours, the variable overhead efficiency variance will be unfavorable when the direct labor efficiency variance is unfavorable and vice versa. The variable overhead efficiency variance is: Budgeted VOH based on actual usage – Variable OH applied to production Or: (AQ – SQ) × SP Where: AQ is the actual quantity of the variable overhead allocation base (direct labor hours or direct machine hours) used for the actual output, SQ is the standard quantity of the variable overhead allocation base allowed for the actual output, and SP is the standard variable overhead application rate. The direct labor efficiency variance is: (AQ – SQ) × SP Where: AQ is the actual direct labor hours used, SQ is the standard direct labor hours allowed for the actual output, and SP is the standard direct labor rate. When variable overhead is applied on the basis of direct labor hours, “AQ” and “SQ” are the same amounts in both the variable overhead efficiency variance and the direct labor efficiency variance. Thus, when variable overhead is applied on the basis of direct labor hours and the direct labor efficiency variance is unfavorable, the variable overhead efficiency variance will also be unfavorable and vice versa. 95 a − The production-volume variance (or the volume variance) is the flexible/static budgeted fixed overhead minus the amount of fixed overhead applied. The flexible/static budget fixed overhead amount is given as $400,000. The predetermined application rate for fixed overhead is $400,000 ÷ 10,000 DLH, or $40 per DLH. With standard costing, overhead is applied to production on the basis of the amount of the application base that is allowed for the actual output. The amount of DLH allowed for the actual output is given as 9,900 hours. Therefore, the amount of fixed overhead applied to production is $40 per DLH multiplied by the 9,900 DLH allowed for the actual output, or $396,000. The Volume Variance is $400,000 − $396,000, which equals $4,000. Since the amount is positive, the variance is unfavorable. It is unfavorable because it means the facilities were not used to the extent planned. 96 b – The total fixed overhead variance is the difference between the actual total fixed overhead cost incurred and the applied fixed overhead. That difference is also the amount of the under-applied or overapplied fixed overhead costs. 97 c – The fixed overhead volume variance results from a difference between actual and budgeted production. Unlike other variances, the fixed overhead production-volume variance (or the volume variance) does not relate to an expenditure problem in which either too much is paid or too much is used. Therefore, the fixed overhead volume variance is the least significant variance for cost control. 98 b – Two standard direct labor hours are allowed for each unit. Since Franklin Glass Works produced 198,000 units, 396,000 standard total direct labor hours are allowed for the actual production (198,000 × 2). 448 © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. CMA Part 1 Answers to Questions 99 a – The VOH efficiency variance can be calculated as Budgeted VOH Based on Inputs Actually Used – VOH Applied to Production. Budgeted VOH based on inputs actually used = VOH allocation rate × DLH actually used. The VOH allocation rate is budgeted variable overhead divided by the DLH allowed for the budgeted number of units. The total budgeted overhead is $900,000 and the fixed overhead is $3 per unit. Since 200,000 units are budgeted for production, the budgeted fixed overhead is $600,000 (200,000 × $3). Therefore, the budgeted variable overhead is $300,000 ($900,000 − $600,000). Since 200,000 units were budgeted and 2 direct labor hours are allowed per unit, 400,000 direct labor hours were allowed for the budgeted production. The variable overhead allocation rate is thus $300,000 ÷ 400,000 hours, which equals $0.75 of variable overhead allocated per direct labor hour. VOH based on inputs actually used = $0.75 VOH allocation rate × 440,000 DLH actually used = $330,000. VOH applied to production = $0.75 VOH allocation rate × (198,000 actual production × 2 DLH allowed per unit) = $297,000. The VOH efficiency variance = $330,000 − $297,000 = $33,000 Unfavorable. The VOH efficiency variance can also be calculated using the following equation: (AQ – SQ) × SP, where AQ is the actual quantity of the direct labor hours used, SQ is the standard quantity of direct labor hours allowed for the actual output, and SP is the standard variable overhead application rate. The actual number of direct labor hours is 440,000 and the standard number of direct labor hours allowed for the actual production is 396,000 (198,000 units actually produced multiplied by 2 direct labor hours allowed per unit produced). The standard VOH application rate was calculated above as $0.75 per DLH allowed for the actual output. Therefore, the formula is: (440,000 − 396,000) × $0.75, which equals $33,000 Unfavorable. 100 c – The Variable Overhead Spending Variance can be calculated as Actual VOH Incurred – Budgeted VOH Based on Inputs Actually Used. Actual VOH incurred is given as $352,000. VOH based on inputs actually used (calculated in the answer explanation to the previous question) = $0.75 VOH allocation rate × 440,000 DLH actually used = $330,000. The VOH spending variance = $352,000 − $330,000 = $22,000 Unfavorable. The VOH spending variance can also be calculated using the following equation: (AP – SP) × AQ, where AP is the actual variable overhead cost per direct labor hour, SP is the standard variable overhead allocation rate per direct labor hour, and AQ is the actual quantity of direct labor hours used for the actual output. The SP, the variable overhead allocation rate per direct labor hour, is $0.75 (calculated in the previous question). The AP is calculated as the actual variable overhead ÷ actual direct labor hours used. The actual variable overhead is $352,000 and 440,000 direct labor hours were actually used. Thus, the AP is $352,000 ÷ 440,000 = $0.80 per direct labor hour. Therefore, the formula is: ($0.80 − $0.75) × 440,000, which equals $22,000 Unfavorable. 101 b – The fixed overhead spending variance is actual fixed overhead incurred – budgeted fixed overhead. The actual fixed overhead is given as $575,000. The budgeted fixed overhead, as calculated in the answer explanation to the previous question, is $3 × 200,000, or $600,000. Therefore, the fixed overhead spending variance is $575,000 − $600,000 = $(25,000) Favorable. 102 c – The amount of fixed overhead applied is calculated as the application rate ($3 per unit as given in the question) multiplied by the number of units actually produced (198,000). Fixed overhead applied is $594,000. 103 a – The fixed overhead volume variance is calculated as the budgeted fixed overhead minus the applied fixed overhead, and a positive amount is unfavorable because it means production volume was lower than planned. The budgeted fixed overhead is $600,000 (calculated for a previous question) and the applied amount is $594,000 (also calculated for a previous question), so the fixed overhead volume variance is $600,000 − $594,000 = $6,000 Unfavorable. 104 d – Clear Plus manufactures a single product. For a single-product firm, flexible budget amounts can be calculated for variable revenue and variable cost lines by dividing the static budget variable amount by the static budget number of units to be sold to get the budgeted amount per unit, and then multiplying that figure by the actual number of units sold. In the static (master) budget, the contribution per unit is $4 per unit ($40,000 ÷ 10,000 units). Therefore, since Clear Plus actually sold 12,000 units, the contribution margin at a sales level of 12,000 units would be expected to be $48,000 ($4 × 12,000 units), and that is © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. 449 Answers to Questions CMA Part 1 the flexible budget amount for the contribution margin. Next, subtract budgeted fixed costs of $30,000. Fixed costs are the same in the flexible budget as in the static budget, since they do not change with changes in activity. The result is the flexible budget operating income of $18,000 at a sales level of 12,000 units. 105 c – The sales volume variance for operating income is the same as the sales volume variance for the contribution margin line and is calculated as (AQ – SQ) × SP, where SP is the standard (or budgeted) contribution margin per unit. The sales volume variance for operating income can also be calculated by subtracting the Static Budget Operating Income from the Flexible Budget Operating Income. Using the formula (AQ – SQ) × SP to calculate the sales volume variance for the contribution margin line, the actual quantity is 12,000 and the standard quantity is 10,000. The standard contribution margin per unit (SP) is $4 ($40,000 ÷ 10,000 units). The sales volume variance is $8,000 Favorable: (12,000 – 10,000) × $4 = $8,000. $8,000 Favorable is also the sales volume variance for operating income. The sales volume variance for the contribution margin and the sales volume variance for operating income are the same since the sales volume variance for fixed costs is zero. The sales volume variance for operating income can also be calculated by subtracting the static budget operating income of $10,000 from the flexible budget operating income of $18,000, as calculated in the previous question: $18,000 − $10,000 = $8,000 Favorable. 106 c – The stand-alone cost allocation method determines the weights for cost allocation by considering each user of the cost as a separate entity. When the stand-alone method is used, total common costs are distributed among the operating units based on each unit’s proportion of the entire organization, using an appropriate basis. 107 d – In evaluating segment performance and the segment manager’s performance, it is important to distinguish between the performance of the manager and the performance of the segment the manager manages. Costs that are traceable to a segment but controlled by someone other than the segment manager are used in evaluating the performance of the segment, but they should not be used in evaluating the performance of the segment manager. 108 a – Contribution margin is calculated as sales revenue minus the variable costs for the units sold. The sales price is $100 per unit and the variable costs total $72 per unit: DM $30; DL $20; other variable manufacturing costs $10; Variable selling costs $12. Thus, contribution is $28 per unit ($100 − $72). 900 units were sold, for a contribution margin of $25,200. 109 a – The basic issue of transfer prices is simply how much should one unit of a company charge another unit of the same company for its goods or services. The goal in setting a transfer price is that the method used will stimulate both the buying and selling department managers to do what will provide the greatest benefit to the company as a whole, rather than to act in their own interest. When there is an external market for the product, market price is almost always the best transfer price to use. Thus, market price is at the maximum of the natural range. When the company has idle capacity, the variable cost approach to determining the transfer price also works well. Since the Fabricating Division has enough capacity to fulfill the demand of the Assembling Division without any over-time, the variable cost approach is also acceptable and is at the minimum of the natural range. 110 a – There are two important points to note in this question. One, the Fabrication Division has excess capacity that is adequate to manufacture all of the 4,500 units of UT-371 that the Electronic Assembly wants to purchase. And two, the question asks for the minimum price, not the best price. "Minimum" means the very lowest price that the Fabrication Division must receive to avoid having a loss on the internal sale. The Fabrication Division will not have any variable selling and distribution costs on the internal order, and its total fixed manufacturing cost will be the same whether it accepts the internal order or not. Since the Fabrication Division has enough excess capacity to produce the order without having to give up any external orders, there will be no opportunity cost. Therefore, the very lowest price that the Fabrication Division must receive is its variable manufacturing cost of $21. The Fabrication Division will break even if the price it receives for the internal order from the Electronic Assembly Division is equal to its variable manufacturing cost. 111 c – A transfer price is not a price charged by the company to external customers, so this is an incorrect description of transfer pricing. A transfer price is the price charged by one unit of the company to another unit of the same company for the services or goods produced by the first unit and "sold" to the second unit. 112 d – The ROI for a division is calculated as its operating income divided by its assets. The division’s operating income is calculated as sales minus expenses, or $4,000,000 net sales − $3,525,000 COGS − 450 © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. CMA Part 1 Answers to Questions $75,000 general and administrative expenses = $400,000. Assets are $2,400,000. The ROI is $400,000 ÷ $2,400,000, or 16.67%. 113 c – Return on investment is operating income divided by assets. North’s ROI is $1,000 ÷ $2,500 or 0.40; East’s ROI is $5,000 ÷ $15,000 or 0.333; South’s ROI is $4,000 ÷ $8,000 or 0.50; and West’s ROI is $7,500 ÷ $25,000 or 0.30. South’s return on investment is the highest of the four. 114 b – To solve this problem, set up a basic ROI using any numbers. For example, use operating income of $100,000 ($500,000 sales revenue − $400 expenses) ÷ assets of $400,000 = ROI of 0.25. Then go through the answer choices, changing the amounts as outlined in each answer choice to find the answer choice that results in an increased ROI, as follows: Answer a: Sales revenue and expenses both increase by $50,000 (thus operating income remains the same) while total assets increase by the same amount. ($550,000 sales revenue − $450,000 expenses) ÷ assets of $450,000 will result in a decreased ROI (to 0.222 from the current 0.25) because the numerator remains the same while the denominator increases. Answer b: Sales revenue remains the same ($500,000) while expenses are reduced by the same amount by which total assets increase. Using a decrease in expenses of $50,000 and an increase in assets of $50,000, ROI increases: ($500,000 sales – $350,000 expenses) ÷ $450,000 assets = ROI of 0.333, an increase from the current 0.25. There is no need to go further, because answer b fulfills the requirement of increasing ROI and thus is the correct answer. However, for illustration purposes, here are examples of the other two answer choices: Answer c: Sales revenue decreases by $25,000 and expenses increase by $25,000: ($475,000 sales revenue – $425,000 expenses) ÷ $400,000 assets (unchanged) = ROI of 0.125, a decrease from the current 0.25. Answer d: Sales and expenses increase by the same percentage that total assets increase: Using 10% increases, sales revenue increases to $550,000 ($500,000 × 1.10); expenses increase to $440,000 ($400,000 × 1.10); and assets increase to $440,000 ($400,000 × 1.10). ROI is unchanged at ($550,000 − $440,000) ÷ $440,000, or 0.25. 115 c – The required rate of return used in calculating Residual Income is an interest rate assigned by management. It is the rate of return that management desires. It is not a cash interest charge but rather it is an interest charge that is assigned for the purpose of analysis. The required rate of return may be the company’s weighted average cost of capital, or it may be another rate. 116 b – Because residual income focuses on an absolute amount of return, use of RI for performance evaluation will prevent the manager of a division with a high current return on investment from rejecting an investment that would be profitable in terms of increasing shareholder wealth but simply has a lower rate of return on investment than the division’s current ROI. 117 d – Residual income is the excess of income over the target level of income, which is assets of the business unit multiplied by the required rate of return. The required rate of return is 10% of the business unit’s assets ($200,000), or $20,000. Since the division’s operating income is $50,000, the division has residual income of $30,000 ($50,000 − $20,000). 118 a – If the expected rate of return on a new investment is greater than the required rate of return (usually the cost of capital), residual income will increase, even if the expected return on the new investment is lower than the current return on investment. 119 c – Any of the accounting policies for inventory listed has the potential to reduce comparability of ROI between two similar divisions. However, the accounting policy difference that would reduce comparability the most is a difference in cost flow assumptions used. ROI is the income of the business unit divided by the assets of the business unit. The inventory cost flow assumption used affects both the income of the business unit and the assets of the business unit. Assuming increasing costs, the use of LIFO will increase cost of goods sold, thereby decreasing net income while also decreasing total assets, because the units on hand in inventory will be costed at lower prices. The use of FIFO will decrease cost of goods sold, thereby increasing net income while also increasing total assets, because the units on hand in inventory will be costed at higher prices. The two ROIs would not be comparable because the bases on which they would be calculated would be different. 120 c – Customer returns, manufacturing throughput time, and training hours are all non-financial measurements that could be used in a balanced scorecard. Return on investment is a financial measurement, and number of manufacturing plants is not a meaningful metric. 121 a – To calculate the customer-level operating profit per unit sold for each customer, consider only relevant revenues and costs. Relevant revenues and costs are those revenues and costs that would cease © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited. 451 Answers to Questions CMA Part 1 to exist if a customer were no longer making purchases. Once the customer-level operating profit is calculated, dividing each customer’s operating profit by the number of units sold to that customer results in the operating profit per unit sold for each customer. Relevant revenues and costs are: sales, cost of goods sold, delivery cost and order taking cost. Those revenues and costs would go away if the customer were no longer a customer. Administration, depreciation and utilities costs would continue. Thus, the customer-level operating profit per unit sold for each of the four customers is as follows: Customer A Customer B Customer C Customer D Sales Cost of goods sold Delivery cost Order taking $100,000 50,000 10,000 15,000 $150,000 60,000 25,000 20,000 $200,000 70,000 30,000 25,000 $250,000 75,000 50,000 30,000 Customer-level operating profit $ 25,000 $ 45,000 $75,000 $ 95,000 Divided by number of units sold 10,000 20,000 35,000 50,000 Equals customer-level operating profit per unit sold $2.50 $2.25 $2.14 $1.90 The customer with the highest customer-level operating profit per unit sold is Customer A. 452 © 2019 HOCK international, LLC. For personal use only by original purchaser. Resale prohibited.