Uploaded by

Martina Nannyonjo

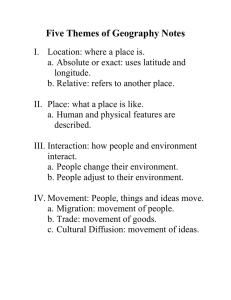

Geography Textbook Senior One: Maps, Climate, East Africa

advertisement