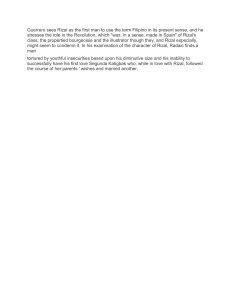

Rizal Law: Life and Works of Jose Rizal - Textbook Excerpt

advertisement