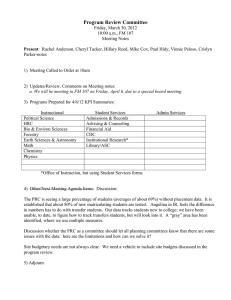

International Interactions, 41:480–508, 2015 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0305-0629 print/1547-7444 online DOI: 10.1080/03050629.2015.1006728 Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon: Can Engagement Moderate China’s Strategic Competition with America? XIAOTING LI East China Normal University Can US engagement moderate China’s strategic competition with America? This study indicates that the answer is a qualified yes. Under unipolarity, a rising state may face both incentives to reach an accommodation with the hegemon and to expand its own stature and influence against the hegemonic dominance. The ambivalence of its intentions is structurally induced and reflects its uncertain stake in the hegemonic order. Consequently, a strategy of engagement may help the hegemon to promote cooperation over competition in dealing with an ascending power, but it does not necessarily eliminate the structural incentives for the competition. Against this theoretical backdrop, this study utilizes both qualitative and quantitative research to demonstrate that China’s reaction to American preeminence has long been marked by a profound ambivalence. Specifically, the findings suggest that while US engagement has some restraining impact on China’s competitive propensity, Beijing will continue to hedge against American hegemony, as its capabilities grow, by solidifying its diplomatic and strategic association with the developing world. KEYWORDS Asia, peace, security With the proverbial rise of China, the future of the US-led global order has become a subject of intense debate among the scholarly community. To some, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the United States are destined for conflict because China’s burgeoning material power will inevitably sharpen its ambitions and lead Beijing to challenge the US primacy in the Address correspondence to Xiaoting Li, School of Advanced International and Area Studies, East China Normal University, A-406 Science Building, 3663 N. Zhongshan Road, Shanghai 200062, China. E-mail: lxtusa@yahoo.com 480 Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 481 world order (Friedberg 2011; Mearsheimer 2001, 2010). Others are more optimistic, on the grounds that China’s growing integration into the international system will likely increase Beijing’s affinity with the prevailing order and dampen its revisionist aspirations (Fingar 2012; Foot and Walter 2011; Johnston 2003, 2008). Still others steer a middle course, observing that the Sino-American relationship is a complex mixture of both cooperative and competitive elements and that the pressing task today is to expand cooperation and limit competition (Lieberthal and Wang 2012; Shambaugh 2013; Sutter 2012). Fundamentally, this debate reflects the deep uncertainties surrounding an old and recurring question in international politics—that is, can a rising state foster a constructive relationship with the hegemon (or the leading state in the system) over the long run? As a rule, rising states have uncertain intentions because new capabilities may create new aims and interests. In particular, as will be addressed in the following, China has long regarded American hegemony with a profound ambivalence; accordingly, PRC strategies often serve the seemingly paradoxical purposes of both accommodating and undercutting US predominance. Of course, the ambivalence of intentions does not necessarily prove an insuperable obstacle to the pursuit of cooperation. After all, from 1972 onward, successive US administrations have adhered to a strategy of “engaging” China, despite the vast ideological differences between the two nations. More recently, prominent US officials have reiterated Washington’s commitment to broadening political and economic exchanges with the PRC, so as to elevate cooperation above competition (Clinton 2012; Kerry 2014). However, when governments may tout the efficacy of a policy as a matter of faith, scholars have to evaluate the issue in terms of competing propositions and evidence. This study is a tentative attempt to explore how and to what extent US engagement might help to moderate China’s strategic competition with America (that is, a competition aimed at countering US primacy). Theoretically, this study derives from a basic tenet of classical realism— that is, while seeking power, states also value prudence in international politics. Under unipolarity, a rising state may thus face both incentives to reach an accommodation with the hegemon and to expand its own stature and influence against the hegemonic dominance. The ambivalence of its intentions is structurally induced and mirrors its uncertain stake in the hegemonic order. An engagement strategy may help the hegemon to build trust and advance cooperation with an ascending power, thereby restraining the latter’s competitive propensity. But it does not necessarily eliminate the structural cause of the competition. These theoretical expectations, moreover, accord largely with the complexity of China’s reaction to US predominance since the end of the Cold War. On the one hand, Beijing welcomes US engagement and seeks to develop practical and continuous cooperation with Washington. Yet, on the other, 482 X. Li Beijing views American hegemony and intentions skeptically and persists in building a diplomatic and strategic partnership with the developing world, which signals China’s dissatisfaction with the US/Western-dominated world order. Empirically, therefore, I use PRC leadership travel to other developing nations—including all countries not belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)—as an indicator of China’s strategic competition with America. As will be seen, such state visits are part and parcel of Beijing’s efforts to extend its strategic leeway against Washington. My quantitative findings suggest that while US engagement has some positive effect in keeping Chinese competition at manageable levels, it does not overwhelm the structural incentives that lead Beijing to hedge against American hegemony in the first place. This study proceeds as follows. The first section contemplates why the structural contradiction between hegemonic dominance and rising power breeds strategic competition and why a strategy of hegemonic engagement may soften, but not resolve, the contradiction. Against this theoretical background, the second section details the enduring ambivalence of Chinese foreign policy vis-à-vis US primacy and discusses the possible effect of engagement in inducing Beijing to stress cooperation over competition. The third section explains why PRC leadership travel to the developing world constitutes a plausible, first-cut indicator of China’s strategic competition with America, while the fourth section presents a research design for testing competing hypotheses about the variation in that competition. The results of the quantitative test are analyzed in the fifth section. The last section concludes by suggesting some implications for future research. THE PROMISE AND LIMITATION OF HEGEMONIC ENGAGEMENT WITH RISING POWER To realists, it is a structural feature of international politics that “overwhelming power repels and leads others to balance against it” (Waltz 1997:916). The hegemonic dominance in the international system, in other words, is in itself a cause for anxiety, resentment, and competition, especially to the rising states with natural ambitions of rewriting the rules governing the system (Gilpin 1981:187). However, while seeking greater power and influence, states are also known to value prudence as the supreme virtue (Morgenthau 1948 [1978]:11). Under unipolarity, it is assuredly imprudent to confront the American hegemon directly, for the following reasons. First, given the preponderance of US power, other states can reap little benefit from traditional balancing strategies, through either an arms race or the formation of a military alliance against the hegemon. Such strategies are not only costly and futile but likely to provoke hegemonic reprisals and thereby put the reckless challenger in immediate jeopardy (Brooks and Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 483 Wohlforth 2008; Kapstein and Mastanduno 1999; Mowle and Sacko 2007; Wohlforth 1999). Second, as a geographically insular country with a reputation for relatively benign intentions, the United States is not seen by most other states as a deadly menace (Pape 2005; Paul 2005; Walt 2005). Rather, it is a leading provider of global public goods, such as economic openness, stability, and security, which benefit most countries and enable their development (Gilpin 1981; Ikenberry 2011). Third, while the current international system reflects many of the hegemon’s interests, it is also an open, integrative, and rule-based order that provides abundant common benefits and opportunities. Consequently, most nations prefer to pursue their interests within this system, rather than challenge the hegemonic leadership that undergirds it (Ikenberry 2011). Thus, realistically, unipolarity requires other countries, including rising states, to accommodate the hegemonic primacy, instead of rocking the boat to their own detriment. Yet, on the other hand, it is equally imprudent for an ascending power to submit to the status quo with resignation. International politics, after all, is a self-help arena wherein states are never certain of each other’s intentions (Mearsheimer 2001:30); hence, they need to prepare for all eventualities. To begin with, there is no guarantee that the hegemon will always use its colossal power constructively or act benignly toward rising states (Ikenberry 2002, 2011; Kapstein and Mastanduno 1999; Monteiro 2014). For fear of losing its primacy, the hegemon might thwart the rise of a potential competitor by active containment or even preventive wars (Mowle and Sacko 2007; Schweller 1999). If an emerging power has dissimilar ideologies and political institutions to those of the hegemon, it might perceive an even greater threat from the latter and thereby feel constrained to counterbalance it (Lemke 2004:65). Furthermore, the hegemon may experience a relative decline over time, especially if a rising state is able to achieve sustained economic growth at a faster rate. Under the circumstances, the hegemon may act more belligerently toward the emerging competitor (see previous), but it may also choose to retrench from its systemic commitments and even negotiate some leadershipsharing arrangements with the newcomer (Schweller and Pu 2011:68–69; for an extended discussion, see Monteiro 2014). In either case, prudence requires the ascending power to strive in advance to expand its own stature and influence in the system, which has the implicit effect of competing against and/or countering the hegemonic dominance, as an insurance against whatever future developments. That is, with the diplomatic and strategic leverage gained from this endeavor, a rising state will be in a stronger position either to withstand a hegemonic assault if push comes to shove or to drive a hard bargain when the hegemonic retrenchment occurs. Thus, it is unsurprising that today’s emerging powers (not just China) invariably pursue a hedging strategy vis-à-vis the hegemon—that is, avoiding 484 X. Li direct confrontation with America but meanwhile preserving some independence of action and preparing favorable conditions for possible systemic changes in the long run. Though short of organizing a formal anti-US coalition (which, as argued earlier, is too risky under unipolarity), this hedging strategy aims at fostering a network of political and economic relationships that serves as a protective shield (and a strategic lever too) for the rising states, maximizing the latter’s ability to act autonomously in the international arena regardless of changes in the hegemonic position or temperament (Foot 2006; Schweller and Pu 2011; Tessman 2012). In essence, the ambivalent intentions of those “hedgers” are structurally bred because their rising power makes the prospect of the current hegemonic order uncertain in the first place and, relatedly, leaves them with an uncertain stake in the status quo. Against this backdrop, engagement becomes a sensible strategy for the hegemon to deal with the ascending powers in some important ways. According to leading US officials, engagement aims to strengthen political and economic associations with a rising state (in this case, China) and solidify its stake in the existing international system, through three mechanisms: promoting trade, broadening interactions through international institutions, and increasing high-level leadership contacts (Clinton 2012; Zoellick 2005). From the standpoint of international relations theory, these mechanisms serve the vital purposes of building trust and advancing cooperation, as elaborated in the following. First, the expansion of economic and trade linkages helps deepen interstate understanding and create a common interest in preserving amicable relations, thereby dampening the prospects for interstate rivalry and conflict.1 Second, as a rule, international institutions help states to improve communication, reduce uncertainty, and ease the management of their disputes.2 Promoting collaborative work through international institutions, therefore, helps the hegemon to allay other states’ concerns about its arbitrariness and bolster their faith in the legitimacy of the prevailing order (Ikenberry 2002, 2011). Moreover, by welcoming a rising state into more international institutions, the hegemon not only satisfies the newcomer’s desire for status (by granting it a “place at the table” of systemic governance) but also fetters it with greater responsibility for the provision of systemic services. Overall, this may help fortify an ascending power’s stake in systemic stability as well as collaboration with the hegemon (Ikenberry 2011; Larson and Shevchenko 2010; Mastanduno 1997). Third, face-to-face leadership contacts often prove critical to alleviating states’ mistrust of each other’s intentions (Holmes 2013). As a rising state 1 There is a voluminous literature on this topic. For a classical study that supports the trade-promotes-peace thesis, see Russett and Oneal (2001); for a classical rebuttal, see Barbieri (2002). 2 Again, there exists a huge literature on this subject. For two classical studies, see Keohane (1984) and Russett and Oneal (2001). Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 485 normally craves respect and higher status, the hegemon may utilize top-level leadership visits and dialogues both to convey its respect for the newcomer’s ascending status and to induce the latter to behave cooperatively in exchange for higher status (Larson and Shevchenko 2010). This may be a key factor that increases an emerging power’s satisfaction with the prevailing order and hence reduces its conflictual propensity (Tammen et al. 2000). In sum, through engagement, the hegemon may forge a closer relationship with a rising state for the pursuit of mutual gains, thereby restraining the latter’s competitive proclivities. It is unclear, however, whether this strategy will eventually resolve the contradiction between the old bottle of hegemonic dominance and the new wine of rising power: For, while engagement may help keep their strategic competition at manageable levels, it does not eliminate the structural cause of the competition. In the long term, despite its elevated position and stake in the existing system, an ascending power may still conclude that it could do even better under an alternative world order designed and governed by itself (Schweller and Pu 2011:51). This prospect becomes more likely today because many rising states have idiosyncratic norms and institutions at odds with the normative foundation of the current hegemonic order (Kupchan 2014). Finally, as argued earlier, even if the hegemon has perfectly benign and cooperative intentions, an emerging power still has to prepare for the remote but not unlikely prospect of hegemonic retrenchment, so that it could fill the vacuum of systemic leadership as much as possible when the critical moment comes. When the hegemon’s intentions are perceived as less than benign, it becomes a strategic necessity for a rising state to hedge against the not-impossible prospect of hegemonic conflict. As shown in the next section, such ambivalence of intentions has largely underlain China’s reaction to US predominance since the end of the Cold War. CHINESE AMBIVALENCE AND US ENGAGEMENT Since 1978, successive PRC administrations have placed a premium on integrating China into the international system, for the sake of the country’s long-term development. Pragmatically, this also requires Beijing to build a constructive relationship with the United States, which is the primary architect and maintainer of the system. In the sober-minded opinion of Chinese leaders and elites, American support is critical to China’s efforts to modernize its economy, participate in global affairs, acquire higher status, and manage sensitive disputes with neighboring countries. Thus, accommodation with the hegemon serves China’s interests far better than confrontation (Deng 2008; Goldstein 2005; Roy 2003; Shambaugh 2013; Sutter 2012). 486 X. Li Accommodation, however, does not imply contentment. On the contrary, since the Tiananmen crisis in 1989, China’s leaders have long perceived a grave “America threat.” Deng Xiaoping, for example, asserted in late 1989 that the United States and the West were waging a “smokeless world war” against the socialist states as well as the entire developing world (Deng 1993:344–345, 348). Jiang Zemin, general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and president of the PRC (1989–2003), kept warning that US and Western “hostile forces” sought to destabilize and dismember China and that Beijing must brace itself for a long-term struggle against their schemes (Jiang 2006, Vol. 1:134–135, 280; Vol. 2:197, 422–423; Vol. 3:8, 83, 139, 450). In November 2011, Jiang’s successor Hu Jintao reiterated the charge against the “hostile international forces,” stressing the “gravity and complexity” of this struggle.3 Meanwhile, although China achieves spectacular development under the prevailing world order, Beijing retains a profound skepticism of US hegemony. In his political reports to the CCP’s national congresses in 1992–2002, Jiang Zemin repeatedly described “hegemonism” (a euphemism for US predominance) as a threat to world peace and stability and stressed China’s support for multipolarity. More significantly, Jiang called for the establishment of a new, “fair and just” international order that inherently rejects US/Western supremacy (Jiang 2006, Vol. 1:242–243; Vol. 2:39–41; Vol. 3:566–567). In 2007–2012, the goals of setting up a new, “fair and just” international order and of “democratizing” international politics, both signaling Chinese dissatisfaction with American hegemony, continued to occupy a prominent place in the CCP’s foreign policy thinking.4 Nonetheless, under unipolarity, it is too risky to incur the hegemon’s focused animosity, by adopting an overt counterbalancing posture against it (see earlier discussions). Accordingly, most countries prefer to employ subtler strategies of countering and constraining US primacy, such as strengthening bilateral and multilateral coordination against American preeminence (Pape 2005; Paul 2005; Tessman 2012). China appears no exception to this rule. As early as the mid-1980s, when frustrated with alleged signs of US hegemonic arrogance, Deng Xiaoping had proposed to widen China’s strategic maneuvering room by forging closer collaboration with the developing world (Leng et al. 2004:819, 829, 935, 977). After the Tiananmen crisis, which caused Sino-American relations to sink to a record low, Beijing made a conscientious effort to cultivate other developing nations diplomatically, to buffer the PRC against US pressures (Qian 2003:255–257). 3 See Hu’s speech to the CCP’s Central Committee, available at http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/201201/01/c_122522635.htm. 4 See Hu Jintao’s political reports to the CCP’s 17th and 18th congresses, available at http://cpc.people. com.cn/GB/64162/64168/index.html. Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 487 Indeed, in Beijing’s visions, building a diplomatic and strategic partnership with the developing world holds the key to the construction of a new world order. Historically, great powers often produce the ideological divisions of the international system that in turn compel them to form divergent alliances (Braumoeller 2012). Admittedly, the current system is buttressed by a US-led coalition of advanced liberal democracies, for which China’s authoritarian development model exerts little appeal. In the abstract, those developed states may endorse the goal of restoring multipolarity and restraining American hegemony, due to their intermittent frictions with Washington. But they are unlikely to support any PRC attempts to revise the existing international order substantially, as long as Beijing appears to play for the other team. Hence, as the self-proclaimed “largest developing nation,” China has long regarded the developing world, which provides pivotal support for Beijing in many global forums (for example, by voting against US/Western attempts to condemn China’s human rights record), as its staunchest ally in international politics (Jiang 2006, Vol. 1:313–314; Vol. 2:373). As Jiang Zemin stated bluntly at a conference of PRC ambassadors in August 1998: We need not only rich friends, but poor friends as well, because poor friends often prove more reliable at critical moments. Thus, while developing relations with major powers, we need to strengthen cooperation with developing nations too, which are more important to us. (Jiang 2006, Vol. 2:205). In August 1999, Jiang again stressed: “Strengthening solidarity and cooperation with the Third World countries remains always the cornerstone of Chinese foreign policy,” especially with regard to Beijing’s cherished goal of reforming the prevailing, US/Western-dominated world order (Jiang, 2006, Vol. 2:372–373). To better engage those “poor friends,” Jiang laid particular emphasis on leadership diplomacy, himself visiting over 50 developing countries as president of the PRC. During those visits, Jiang invariably accentuated upgrading the collaboration between China and the developing world against US “hegemonism” and for the establishment of a new international order (Jiang 2006, Vol. 1:528–529; Vol. 2:402–403, 405–406; Vol. 3:239–241). Afterward, Jiang’s successor Hu Jintao followed suit, signaling through similarly high-profile visits that China could generate enough leverage in the developing world against American predominance (Medeiros 2009, chapter 6; Sutter 2012, chapter 12). More recently, the new PRC administration led by President Xi Jinping has gone further down this well-trodden path of Chinese leadership diplomacy in cultivating such regional powers as Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela, all literally located in Washington’s strategic backyard (Oppenheimer 2014). 488 X. Li Admittedly, like other “soft-balancers” against the United States, Beijing has hitherto refrained from founding formal military alliances with other countries, to avoid antagonizing Washington directly (Brooks and Wohlforth 2008:72–75; Walt 2005:121–123). But the strategic implications of China’s diplomatic activism in the developing world have long been a cause for concern in Washington. As a Pentagon report noted in November 1998: “Although China has no plan to lead a faction or block of nations in directly challenging the United States, its international political activities . . . are designed to achieve the same result.”5 In other words, if China decides in the future to convert those international relationships into a formal anti-US coalition, much of the necessary groundwork will already have been laid. Still, to this day, most PRC elites seem to agree that American unipolarity will not end anytime soon and that China still has to develop practical and continuous cooperation with the United States on a wide range of issues (Fingar 2012; Sutter 2012, chapter 6). Accordingly, Beijing has long welcomed US engagement, as a means of expanding cooperation and limiting disagreements. After the Tiananmen crisis, Deng Xiaoping promptly suggested that strengthening dialogues and exchanges was the only way of improving Sino-American relations (Leng et al. 2004:1296–1300, 1304–1305; see also Deng 1993:330–333, 350–351). In July 1993, Jiang Zemin also averred at a conference of PRC ambassadors that stabilizing and improving the SinoAmerican relationship was vitally important to China’s development; hence, Jiang advocated responding positively to the overtures of the US administration in engaging China, while remaining on guard against American “hegemonism” (Jiang 2006, Vol. 1:312–313). Indeed, in November 1993, during his first summit with US President Bill Clinton, Jiang took the initiative to pledge that “China will not engage in an arms race, or organize military alliances, to threaten US security.” Agreeing with President Clinton that the two countries still shared many common interests in promoting world peace and development, Jiang urged holding more leadership summits in the future, to reduce misunderstanding and resolve differences in a timely manner (Jiang 2006, Vol. 1:333–334). In 1994, the Clinton administration formally unveiled its strategy of “comprehensive engagement” with China. In October 1995, President Clinton told Jiang Zemin in person that American policy toward China was “not confrontation, but cooperation; not isolation, but integration; not containment, but engagement,” which impressed Jiang deeply and reinforced his determination to seek greater cooperation with the United States and to integrate China further into the international system (Jiang 2006, Vol. 2:203; Zhong 2006:135–136, 267–274). Thereafter, US engagement seemed to have some positive impact on Chinese foreign policy behavior. According to Susan 5 See the US Department of Defense, Future Military Capabilities and Strategy of the People’s Republic of China, available at http://www.fas.org/news/china/1998/981100-prc-dod.htm. Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 489 Shirk, former deputy assistant secretary of state in the Clinton administration, two engagement mechanisms—promoting top-level leadership contacts and broadening interactions through international institutions—were particularly important in this respect. To begin with, the exchange of state visits between Jiang Zemin and President Clinton in 1997–1998 left Jiang “personally invested in his relationship with President Clinton and in improving relations with the United States” (Shirk 2007:266). Afterward, when confronted by sudden diplomatic crises (for example, US bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999, and the EP-3 collision incident in the South China Sea in 2001), the PRC leadership invariably sought to prevent escalation and preserve cooperation with Washington (Jiang 2006, Vol. 3:447–448; Tang 2009:197, 328–339). In the Asia-Pacific area, until fairly recently, Sino-American cooperation had actually constituted a significant feature of the regional order, even on the ultrasensitive Taiwan issue (Huang and Li 2010; Shambaugh 2005, 2013; Shirk 2007). Meanwhile, Washington supports China’s inclusion in more and more international institutions (Clinton 2012). In Shirk’s (2007:267) view, “[m]aking China a member of all important multilateral forums enhances the prestige of China and its leaders, as well as giving them a strong sense of responsibility for maintaining world order.” In reality, closer Sino-American interactions in international institutions appear to have nudged Beijing in a more constructive direction on a wide range of global and regional issues (Foot and Walter 2011; Johnston 2008; Kent 2007; Medeiros 2007; Shirk 2007). In short, given the complexity of China’s reaction to American primacy, we face two broad possibilities: (1) since China harbors enduring misgivings about US hegemony and intentions, it will likely persist in hedging/competing strategically against American predominance; (2) on the other hand, if Beijing is pragmatic enough to welcome US engagement and expand cooperation, it will also likely keep competition within controllable bounds in the meantime. The next section will explain why PRC leadership travel to the developing world may serve as a plausible indicator of China’s strategic competition with America and present two main hypotheses correspondingly. LEADERSHIP TRAVEL AS AN INDICATOR OF STRATEGIC COMPETITION In a pioneering study, Kastner and Saunders (2012:165) argue that China’s diplomatic priorities could be partially inferred from where its leaders travel abroad, for the triple reasons that such travels are politically salient, involve a significant commitment of Chinese government resources, and herald the expansion of Beijing’s political, economic, and diplomatic collaboration with 490 X. Li other countries thereafter. Corroborating this argument, the preceding analysis shows that Beijing has long put leadership diplomacy at the forefront of its efforts to bolster the PRC’s stature and influence in the developing world against American hegemony. In reality, China’s gains from this endeavor may include: (1) greater international support for Beijing’s positions in global and regional affairs, (2) stronger relationships to protect Chinese access to overseas markets and energy sources (so as to offset any possible deterioration in US-China relations), (3) restrictions on US options toward the countries that benefit from closer ties with China, and (4) tentative security cooperation that may lay the foundations of future alliances (Goldstein 2005; Medeiros 2009; Nathan and Scobell 2012; Shambaugh 2013; Sutter 2012). As a RAND study concludes, these developments have produced complications in and constraints on US interactions with many developing nations (Medeiros 2009:211–212). Viewed in this light, PRC leadership travel to the developing world has the implicit effect of countering US primacy both symbolically and substantively. Hence, it may be considered a plausible, first-cut indicator of China’s strategic competition with America. Based on original data collected by myself (see the next section), Figure 1 graphs the annual number of Chinese leadership visits to developing/non-OECD and developed/OECD states respectively in 1982–2012. Evidently, in the last three decades, China’s top leaders (defined as the president and the premier in this study) have displayed a much stronger interest in visiting developing nations. The Tiananmen crisis in 1989 marks a veritable turning point in this respect. In 1982–1988, the PRC president/premier paid 40 visits to developing states and 28 visits to FIGURE 1 Chinese leadership travel to the developing and developed countries, 1982–2012. Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 491 developed states; in other words, 58.8% of Chinese leadership travel was directed toward the developing world, with approximately five to six visits per year. By contrast, in 1989–2012, the number of PRC leadership visits was 267 for developing countries and 117 for developed countries; in other words, 69.5% of Chinese leadership travel was targeted at the developing world, with approximately 11 to 12 visits annually (comparatively, there was little change in the yearly average of visits to OECD countries for the 1982–1988 and 1989–2012 periods). This development corresponds closely with Beijing’s aforementioned foreign policy objective, after Tiananmen, of seeking greater solidarity with the developing world against US “hegemonism.” Nevertheless, there are some interesting variations in this pattern. In 1996–1998, when US engagement acquired unprecedented momentum, culminating in the exchange of state visits between Jiang Zemin and President Clinton, there was a steep decline in PRC leadership travel to the developing world. In marked contrast, in 1999–2001, when Sino-American relations were strained once again, China’s top leaders resumed their diplomatic activism in visiting other developing countries. After President George W. Bush’s visit to China in early 2002, however, the US-China relationship improved rapidly, with a corresponding, drastic reduction in Chinese leadership travel to the non-Western world. Similar declines in PRC leadership diplomacy also occurred after 2006, when President Hu Jintao paid a successful visit to the United States; and after 2009, when President Barack Obama visited China. Those zigzag changes suggest that US engagement may have something to do with the adjustments in China’s diplomatic priorities. Indeed, Jiang Zemin indicated as much in his keynote address to the CCP’s 16th congress in November 2002. While continuing to extol solidarity with the developing world, Jiang conspicuously assigned a lower priority to this old theme of PRC diplomacy. Instead, he paid foremost attention to “improving and advancing relations with the developed countries,” with a view to expanding cooperation and managing differences appropriately (Jiang 2006, Vol. 3:567).6 In other words, Jiang affirmed indirectly that in Chinese foreign policy, the necessity to engage the West (primarily the United States) sometimes prevailed over the necessity to engage the developing world. Thus, if US engagement does induce Beijing to value cooperation with Washington, China will likely moderate its strategic competition with America, as manifested by fewer PRC leadership visits to the non-Western world. To realists, however, a rising state’s challenge to the hegemonic order is largely a function of its relative capabilities to do so. Accordingly, in the long 6 Note that in 2007–2012, Hu Jintao made similar statements in his political reports to the CCP’s 17th and 18th congresses, which are available at http://cpc.people.com.cn/GB/64162/64168/index.html. 492 X. Li run, US engagement may not be enough to dissuade China from seeking to undermine American predominance. On the contrary, as its capabilities grow, Beijing might still expend an increasing effort in solidifying its diplomatic and strategic association with a broad variety of developing nations, as manifested by more PRC leadership travel to the non-Western world. Quantitatively, when an outcome phenomenon of interest may be affected by several explanatory factors, it is often helpful to determine the relative impacts of those competing factors through statistical analysis. To begin with, I posit the following two hypotheses: H1: The more powerful China becomes vis-à-vis America, the more likely its leaders will visit the developing world. H2: The more China is engaged by America, the less likely its leaders will visit the developing world. RESEARCH DESIGN To examine these hypotheses, I use time-series, cross-section data on Chinese leadership travel to the developing world in 1990–2012 (see the appendix available online). In other words, the unit of analysis is the target country-year. Methodologically, this approach enables us to address several highly pertinent questions. First, since the PRC leadership never singles out any particular developing countries as Beijing’s preferred partners, we need to examine whether the passage of time leads to more Chinese leadership visits to any and all developing nations. Second, given the varying characteristics of individual states, we have to explore whether the PRC leadership will, over time, more likely visit some countries than others. Finally, the central purpose of this study is to evaluate the time-series effects of such causal variables as the growth of China’s relative power or various mechanisms of US engagement with China. I collect original data from the authoritative Xinhua Monthly Report (Xinhua Yuebao), a journal published by the Xinhua News Agency that provides timely accounts of the PRC leadership’s domestic and international activities. I choose 1990 as the beginning year because it signified to Beijing the beginning of post-Cold War US hegemony. My data focus on the two topmost leaders of China, the president (who serves invariably as the CCP’s general secretary) and the premier, who normally direct Chinese foreign policy. Other top civilian leaders, such as the Speaker of the National People’s Congress and the Chairman of the National Political Consultative Conference, have little influence over the relevant policymaking process (Nathan and Scobell 2012:49). Accordingly, as observed by Kastner and Saunders (2012), the president/premier’s travel abroad is perhaps the best indicator of China’s diplomatic priorities. Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 493 Meanwhile, my research design differs from the work of Kastner and Saunders (2012) in two aspects. First, it broadens the temporal domain, as their study deals only with the period 1998–2008. Second, it appraises the causal impact of key explanatory factors over time, whereas their study estimates such impact on a state-by-state, but not year-by-year, basis. As mentioned earlier, I conceptualize the developing world as comprising all countries that are not OECD members. If a state joins the OECD within the 1990–2012 period, I code it as a developing state until the year of its OECD admission. Because China’s leaders never visit any country that has no formal diplomatic relations with the PRC, I exclude any country-year observations wherein the concerned state maintains no diplomatic relationship with Beijing, to avoid inflating the data unnecessarily. Within the developing world, the PRC leadership may have a special affinity with authoritarian states. This is not only because birds of the same feather tend to flock together but because countries with domestic institutions dissimilar to those of the United States may share a common interest in counterbalancing Washington (Lemke 2004:65). Thus, I create a subset of data that includes autocracies alone, to explore whether US engagement reduces the likelihood of Chinese leadership travel to this particular group of countries, which are more likely to side with Beijing in an anti-American struggle. I regard a state as an autocracy in a given year if, according to the Freedom House’s annual Freedom in the World Survey, it is considered “not free” in that year (such states are invariably coded as “autocracies” by the widely used Polity IV data set too). Dependent Variable: Chinese Leadership Travel My dependent variable is a dichotomous measure—that is, whether or not the PRC president or premier visits a developing nation in a given year (0 means no leadership visit, 1 otherwise). I choose this measure because neither of the two leaders will visit the same country twice in a year and because they rarely visit the same country in the same year. Regrettably, I am unable to ascertain the number of days spent by the Chinese leaders on each trip, because Xinhua Monthly Report does not always supply this information. Like Kastner and Saunders (2012), my primary data exclude leadership visits made solely for the purpose of attending a multilateral international meeting in a particular developing nation, for two reasons. First, such “sideline” trips often do not involve a significant commitment of Chinese government resources (for example, economic aid and investment commitments); hence, they are perhaps of secondary importance in Beijing’s efforts to cultivate the developing world. Second, such visits are actually quite sparse: Due to the well-known Chinese penchant for ceremony and protocol, only 4% of all PRC leadership travels to developing countries in 494 X. Li 1990–2012 occurred in a multilateral context without being accompanied by a formal visit by the Chinese president/premier to the concerned countries in the same year (see the appendix). Consequently, in a separate robustness test, I find that the inclusion of those visits does not affect the results of the data analysis, which is consistent with Kastner and Saunders’s (2012) earlier discovery on the same count. Independent Variables To measure China’s relative power vis-à-vis America, I create a variable, CU Relative Power, which is the annual Sino-American GDP ratio (in current US$, from the World Bank database). For robustness tests, I use the annual ratio of military spending between China and the United States as an alternative measure, based on the Military Expenditure Database of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (http://milexdata.sipri.org). Unsurprisingly, those two measures are in fact highly correlated with each other (the Pearson’s r is .94). I choose not to utilize the Correlates of War (COW) project’s National Material Capabilities (v4.0) data set because its measure of national power may have greatly overestimated China’s relative capabilities. For example, according to this data set, the PRC’s material power has exceeded that of the United States since 1996, which is not a very credible estimation. I also create the following variables to approximate the three principal mechanisms of US engagement with China—expanded trade, increased interactions through international institutions, and more high-level leadership contacts. The first variable, CU Trade Dependence, is the ratio of China’s annual trade with the United States to China’s GDP in the same year. The trade information is taken from the COW Bilateral Trade (v3.0) dataset (Barbieri and Keshk 2012). I obtain China’s annual GDP data (in current US$) from the World Bank database. Regrettably, there are no reliable data on China’s dependence on foreign direct investment from the United States annually, due to the PRC’s inconsistent financial reporting standards before its accession to the World Trade Organization. The second variable, CU Joint IGOs, refers to the number of the shared membership of China and the United States in intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) in a given year. This is a widely adopted measure of the extent of interactions between two nations through international institutions, based on the COW Intergovernmental Organizations (v2.3) dataset (Pevehouse, Nordstrom, and Warnke 2004). The third variable, US Visits, is a dummy variable indicating whether the US president or vice president visits China in a given year (0 means no such visit, 1 otherwise). This information is also from Xinhua Monthly Report. For robustness checks, I create a dummy variable indicating whether the PRC president, vice president, or premier visits the United States in a given year. Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 495 Admittedly, the measures for the independent variables (especially relative power and trade dependence) change only incrementally, though the trend is toward an increase over time. Nonetheless, Beijing habitually pays close attention to the trends in its relations with other countries (for example, see Christensen 2006). Thus, these measures may still matter considerably to Beijing’s perceptions of its relative power position, and of how it is being engaged (for example, even one more shared IGO membership breeds more regularized interactions with Washington in international institutions). Control Variables Several competing explanations of Chinese leadership travel require attention here. First, Beijing’s diplomatic activism in the developing world derives also in part from its desire to secure access to overseas markets and strategic resources, especially oil (Medeiros 2009:148–149). To approximate the economic significance of a country to China, I use three controls, adopted first by Kastner and Saunders (2012): (1) Population, which is the natural log of a country’s population in a given year, as recorded in the Penn World Table Version 7.1 (Heston, Summers, and Aten 2012); (2) Bilateral Trade, which is the natural log of a country’s annual trade with China (based on the COW Trade dataset); (3) Oil-Richness, which is the natural log of a country’s proven oil reserves in a given year, based on the International Energy Statistics database of the Energy Information Administration of the US Department of Energy (http://www.eia.gov/countries/data.cfm). The log function is necessary for reducing the high level of variance in the raw data. For robustness tests, I also control for a country’s annual GDP and/or GDP per capita, which are, unsurprisingly, highly correlated with the country’s population and trade with China. Thus, using these alternative measures does not change the results. Regrettably, due to the lack of reliable data, I am unable to control for the annual investment flows between China and another country, or a country’s annual production of other natural resources that might pique Beijing’s attention. Second, while welcoming US engagement, China has long sought to broaden its political and economic contact with the West at large, which might have decreased Beijing’s interest in the developing world over time, leading to more PRC leadership travel to OECD states and fewer visits to developing nations. Thus, I create two controls: (1) CW Trade Dependence, which is the ratio of China’s annual trade with OECD countries to China’s total foreign trade in the same year (based on the COW trade dataset); and (2) CW Visits, which is the total number of PRC leadership visits to OECD countries in a given year (see the appendix). Third, since the mid-1990s, China has not only joined more international institutions but sponsored some intergovernmental organizations within the 496 X. Li non-Western world (for example, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the China-Africa Forum). Given the well-known coordination effects of IGOs, this might have helped Beijing to coordinate policies with other developing nations without the trouble of leadership visits. Thus, I create a control, CD Joint IGOs, which is the shared IGO membership of China and another developing state in a given year (based on the COW IGO data set). Fourth, China’s preoccupation with regional security challenges might have reduced its incentives for competition with America in other parts of the world. Thus, I create a control, Local Challenges, to indicate the number of China’s territorial disputes in a given year. In reality, Beijing always regards sovereignty and territorial integrity as a vital national interest, and the settlement of each dispute requires a significant commitment of Beijing’s attention and resources. This information is from Fravel’s (2008:46–47) data on China’s territorial disputes since 1949 because the Issue Correlates of War project has not included China yet. I code a territorial dispute as closed after China signs a boundary agreement concerning that dispute. Fifth, if the PRC is bent on challenging US preeminence, Beijing would find it easier to recruit allies from among the countries that are at odds or at least not closely associated with Washington. Thus, I create three controls, adopted also by Kastner and Saunders (2012): (1) Rising States, a dummy indicator of whether a country is a member of the Group of Twenty but not simultaneously a member of the original Group of Seven (1 if yes, 0 otherwise); (2) US Ally, a dummy indicator of whether a country has a formal military alliance with the United States in a given year (0 if no alliance, 1 otherwise); and (3) US Sanction, a dummy indicator of whether a country is the target of US economic sanctions in a given year (0 if no sanctions, 1 otherwise). The information about alliances and sanctions is taken from the COW Alliances (v4.1) data set (Gibler 2009) and the Peterson Institute for International Economics (Hufbauer, Schott, and Elliot 2007; Hufbauer, Schott, Elliot, and Muir 2012) respectively. In robustness tests, I use two alternative measures of a country’s political association with the United States: (1) Affinity of Interest, a widely adopted index of the affinity of nations based on the similarity of voting in the UN General Assembly in a given year (Gartzke 2006; Strezhnev and Voeten 2013); and (2) US Troops, a dummy indicator of whether the United States stations at least 1,000 troops in a country in a given year (1 if yes, 0 otherwise), as recorded in Kane’s (2006) data set on global US troop deployments. Finally, I control for a country’s geographical proximity to China by creating a dummy variable, Asia, to indicate whether the country is located in Asia (1 if yes, 0 otherwise). Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 497 Methodology Since my dependent variable takes binary values, I employ logistic regression as the method of estimation. I control for time dependence in the data by utilizing two alternative corrections—the spline method of Beck, Katz, and Tucker (1998) and the cubic polynomial method of Carter and Signorino (2010). The addition of year-dummies, as recommended by those two methods, helps to assess the possibility that there might exist other year-specific factors influencing Chinese leadership diplomacy that are not accounted for by the main explanatory variables. Typically, a PRC leadership visit to a foreign country requires extensive preparations over a long time. As a result, any leadership travel that occurs in a given year is plausibly planned according to Chinese assessments of changes in key explanatory factors in a previous year. Thus, I lag all explanatory variables by one year, except those that are time invariant (for example, G-20 states or US alliances). All computations of the data are completed by using Stata version 10. FINDINGS Before running the models, I first conduct a test of collinearity among the explanatory variables, by using the collin (Collinearity diagnostics) program designed by the UCLA Academic Technology Services (http://www.ats.ucla. edu/stat/stata/ado/default.htm). The results show that China’s relative power, measured by either GDP or military spending, is highly collinear with its trade dependence on the United States and its preoccupation with local challenges. Theoretically, this is hardly surprising because a flourishing SinoAmerican trade relationship has been a major cause of China’s economic takeoff, and much of Beijing’s military spending is directed at countering local security threats. Once the relative power variable is dropped, however, all other explanatory variables are below the threshold of collinearity. To avoid biasing the results of statistical analysis, I run the preliminary models without including the relative power variable, which I use in later models (reported in the following). In fact, this by no means obviates the causal importance of relative power in influencing Chinese leadership diplomacy. Instead, later models highlight this causal effect more clearly.7 In Table 1, Model 1 and Model 2 present the findings of the preliminary models. As expected, two of the three US engagement mechanisms, the SinoAmerican IGO interactions and US presidential visits to China, display a 7 All models control for time dependence with the application of splines. Using Carter and Signorino’s (2010) cubic polynomials produces similar results. 498 X. Li TABLE 1 Logit Analysis of Chinese Leadership Travel to the Developing World, 1990–2012 Explanatory Variables CU relative power CU Trade dependence CU joint IGOs US visits Population Bilateral trade Oil-richness CW trade dependence CW visits CD joint IGOs Local challenges Rising states US ally US sanction Asia Pseudo R2 N Model 1: All Developing World —−8.80 (7.38) −.15 −.50 .31 .42 −.01 −1.05 (.045)∗∗∗∗ (.23)∗∗ (.08)∗∗∗∗ (.07)∗∗∗∗ (.01) (1.11) −.03 (.04) −.01 (.02) −.42 (.11)∗∗∗∗ −.06 (.36) −.21 (.25) −.25 (.25) .18 (.21) .19 1904 Model 2: All Autocracies Model 3: All Developing World Model 4: All Autocracies —1.30 (13.65) 17.32 (5.50)∗∗∗ —- 34.88 (9.98)∗∗∗∗ —- −.22 −.46 .31 .40 −.01 1.08 −.29 (.10)∗∗∗ −1.06 (.45)∗∗ .37 (.16)∗∗ .23 (.14)∗ .002 (.017) 1.77 (1.61) −.175 (.089)∗∗ −.96 (.43)∗∗ .38 (.16)∗∗ .26 (.14)∗ −.0003 (.017) −1.87 (1.89) .05 −.01 −.58 −.26 −.01 −.34 .57 .18 (.07) (.03) (.21)∗∗∗ (.77) (.94) (.36) (.38) 643 (.05)∗∗∗∗ (.24)∗ (.08)∗∗∗∗ (.07)∗∗∗∗ (.01) (.93) −.05 (.04) −.01 (.02) —−.07 (.36) −.21 (.25) −.26 (.25) .21 (.21) .18 1904 .02 (.07) −.01 (.03) —−.28 (.77) −.02 (.94) −.34 (.36) .61 (.38) .18 643 Entries are logit coefficients. Standard errors in parentheses. ∗∗∗∗ p < .001, ∗∗∗ p < .01, ∗∗ p < .05, ∗ p < .1, two-tailed tests. Splines dropped for space limitations. statistically robust effect in restraining PRC leadership travel to the developing world as well as fellow autocracies.8 Intriguingly, China’s trade dependence on America fails to manifest any statistically significant impact on Beijing’s diplomatic activism in this regard. Possibly, given the high level of Sino-American economic interdependence, China has become “too big to cut off” for Washington, which decreases the utility of trade dependence as an instrument for influencing Chinese foreign policy. Other findings are equally interesting. Consistent with China’s image as a mercantile, market-hungry power, the PRC president/premier are significantly more likely to visit a developing nation, or an authoritarian state, that has a large population and/or a booming trade relationship with the PRC. However, whether a state possesses large oil reserves has no appreciable influence on the likelihood of Chinese leadership travel to that country—a discovery also made by Kastner and Saunders (2012). Meanwhile, China’s widening economic and diplomatic contact with the West does not significantly impact Beijing’s diplomatic activism toward the developing world. Likewise, the increased IGO interactions between China 8 In robustness tests, I find that PRC leadership visits to the United States, used as an alternative measure of Sino-American high-level contacts, also reduces significantly the likelihood of Chinese leadership travel to the developing world. Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 499 and other developing nations demonstrate no statistically robust influence on the PRC leadership’s travel decisions. Arguably, these findings convey a double message: (1) China’s growing connections with the West do not necessarily diminish the strategic importance of the developing world to Chinese foreign policy; and (2) to Beijing, US engagement is a weightier factor to reckon with than China’s interactions with any other Western or non-Western states. Furthermore, China’s preoccupation with territorial disputes does make its leaders significantly less likely to visit the developing world or fellow autocracies. Indirectly, this finding also points to a strategic necessity for Beijing to cultivate American support for the settlement of security conflicts in East Asia (Sutter 2012:134–135). Geographical proximity, however, proves unimportant: As China gradually becomes a global power, Beijing obviously no longer restricts the focus of Chinese diplomacy to Asia alone. Finally, like Kastner and Saunders (2012), I also find that the PRC president/premier have no visible interest in visiting a country that is either an emerging power, a target of US sanctions, or a formal ally of Washington. In robustness tests, whether a developing state has a lower affinity of interest or fewer defense links with America has no statistically significant impact on Chinese leadership travel, either. This finding corresponds with some US experts’ observation that since the 2000s, Beijing has become more cautious in approaching controversial regimes that are at variance with the United States (Kleine-Ahlbrandt and Small 2008; for a similar view, see Sutter 2012:597). Under unipolarity, as argued earlier, prudence requires China to avoid an overt challenge to the American colossus, despite Beijing’s latent revisionist aspirations. Yet, on the other hand, China’s growing relative capabilities might well have stiffened Beijing’s resolve to hedge against American hegemony. In Table 1, Model 3 and Model 4 present the results with the incorporation of the relative power variable and with the exclusion of two aforementioned variables that are highly collinear with it. As hypothesized, China’s burgeoning relative power exhibits a strong and highly significant effect in stimulating PRC leadership travel to the developing world as well as fellow autocracies.9 In other words, a materially stronger China becomes more proactive in competing against US primacy and expanding its own stature and influence internationally. Nonetheless, it is worth emphasizing that in Model 3 and Model 4, the two key mechanisms of US engagement continue to play a salient role in constraining Beijing’s diplomatic activism in this regard. Meanwhile, there are continuing indications that Chinese diplomacy is not yet driven by a virulent anti-Americanism: 9 The results remain the same if we use China’s annual military spending as an alternative indicator of its rising military power. Unsurprisingly, this variable is also highly correlated with the annual Sino-American GDP ratio (the Pearson’s r is .97). 500 X. Li As in previous models, the PRC president/premier are far more likely to visit a developing country because of its economic significance to China, rather than on account of its political relationship with the United States. At this point, however, a perceptive reader might ask: Since the Chinese leadership visits to developing nations have, on average, increased over time anyway, could this trend be driven mainly by the passage of time (similar to the thesis that “the longer you know somebody, the more likely you will visit his/her house”), rather than by other explanatory variables? Typically, in quantitative international relations (IR) scholarship, the problem of temporal dependence can be resolved either by the introduction of splines or cubic polynomials (as already applied in previous models) or by employing a time variable, such as the widely used indicator of the continuance of peace years between one state and another (see Senese and Vásquez 2008:60, 71). Adopting this latter approach, I create an alternative “year” variable, by coding the beginning year in each target country’s interactions with China as 1 within the 1990–2012 period.10 As this variable proves insignificant and does not affect the causal significance of others in all models, the validity of previous findings remains unimpaired. In an additional robustness check, I also assess the possibility that US military presence in East Asia may have increased China’s distrust of American intentions, thereby leading Beijing to hedge against US predominance more vigorously. Using Kane’s (2006) data on global US troop deployments, I create a control variable, US-Asia Troops, which is the annual number of US troops stationed in East Asia. This variable, however, appears insignificant in all models, perhaps because, until the 2010s, US military presence in the region had been overall declining and was not perceived by Beijing as a grave security concern.11 To illustrate the substantive effects of key explanatory variables, Table 2 reports the impact on the predicted probability of PRC leadership travel by each variable that remains statistically significant in Model 3 and Model 4 respectively when all other variables are held at their mean values. Due to space limitations, I only examine the results as each variable changes from its minimum value to its maximum value, but other analyses (based on representative values or one-standard-deviation increase in the values) are available upon request. 10 Nevertheless, if a state experienced a rupture in its diplomatic relations with China during this period, I code the year of the reestablishment of such relations as 1 again. 11 Similarly, controlling for China’s annual involvement in a militarized interstate dispute (MID) against the United States does not change the results, possibly because: (1) most Sino-American MIDs in 1990–2010 were lower-intensity conflicts (that is, not involving the actual use of force); and (2) after experiencing such a conflict, Beijing usually sought to improve its relations with Washington subsequently (for example, see Shirk 2007 and Tang 2009). 501 Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon TABLE 2 Predicted Probability of Chinese Leadership Travel, 1990–2012 Model 3 (All Developing World) Explanatory Variables Model 4 (All Autocracies) Min Max Prob. Change (% Change) Min Max Prob. Change (% Change) CU relative power .021 .141 .120 (+5, 700) .010 .385 .375 (+3, 750) CU joint IGOs .329 .028 −.301 (−91) .546 .026 −.520 (−95) US visits .056 .036 −.020 (−36) .076 .028 −.048 (−64) Population .013 .198 .185 (+1, 400) .009 .157 .148 (+1, 530) Bilateral trade .000 .429 .429 (+42, 900) .014 .178 .164 (+1, 200) Within the 1990–2012 period, when China’s relative power peaks vis-àvis America, the probability of PRC leadership travel to the developing world and to fellow autocracies rockets up by 57 times and 37.5 times respectively. This does not mean, however, that US efforts to engage China are useless. At the zenith of Sino-American IGO interactions (as measured by their joint IGO membership), the likelihood of a Chinese leadership visit to the developing world and/or other authoritarian states shrinks by 91% and 95% respectively. US presidential visits to China have a remarkable constraining effect in this direction too. In the wake of such a visit, the probability of PRC leadership travel to the developing world and to fellow autocracies dwindles by 36% and 64% respectively. Meanwhile, the likelihood of PRC leadership travel is also heavily swayed by a country’s economic significance (or market potential) to China. When a developing and/or authoritarian state happens to have the largest population among its peers, the probability of a Chinese leadership visit to that state increases by 14 times and 15 times respectively. Similarly, when a developing or authoritarian country’s trade volume with China reaches the highest level, the probability of a PRC leadership visit surges by 429 times and 12 times respectively. In sum, this study indicates that the relationship between an ascending China and the American hegemon is manageable to some extent but may become increasingly competitive over time. Theoretically, this is because a rising state may have wider aims and interests stemming from its enhanced relative capabilities and because those aims and interests are not always compatible with the existing hegemonic order. Consequently, a strategy of hegemonic engagement may help expand cooperation and limit competition 502 X. Li with an emerging power, but it does not necessarily set the permanent boundaries of the latter’s revisionist aspirations.12 This is not to say, however, that China and the United States are bound to become outright adversaries. The costs are simply too high for both countries and indeed for the world. This probably explains why both Beijing and Washington have persistently emphasized the necessity for promoting dialogues and cooperation, to build more bridges between the two nations and erode the ground for unlimited competition and conflict (Kerry 2014). Indirectly, this study provides both a testimony to the progress that has been made in this direction and a reminder that more arduous work still needs to be done in the future. CONCLUSION Can US engagement moderate China’s strategic competition with America? This study indicates the answer is a qualified yes. Under unipolarity, a rising state may face both incentives to accommodate the hegemonic dominance and to expand its own strategic leeway against the latter. Consequently, engagement may help the hegemon to promote cooperation over competition in dealing with an ascending power, but it does not necessarily overwhelm the structural incentives for the competition. Against this theoretical backdrop, this study utilizes both qualitative and quantitative research to demonstrate that China’s reaction to American primacy has long been marked by a profound ambivalence. Specifically, the findings suggest that while US engagement has some restraining impact on China’s competitive propensity, Beijing will continue to hedge against American hegemony, as its capabilities grow, by solidifying its diplomatic and strategic association with the developing world. The endurance of competition, however, does not imply that conflict is inevitable. In fact, facing the reality of rising power, realist theory does not uniformly predict catastrophe or recommend containment: To classical realists, the future is always unwritten, and so wise diplomacy matters (Kirshner 2012:65–66).13 Despite China’s impressive development to date, for example, it is far from certain that the PRC will achieve parity with the United States in economic, military, and technological strength for the foreseeable future 12 Note, for example, Beijing’s growing assertiveness in handling maritime disputes with Japan and some Southeast Asian countries and its unilateral declaration of an air defense identification zone in the East China Sea in late 2013. 13 Intriguingly, in July 2014, Secretary of State John Kerry made a similar point during the US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue, by emphasizing that Sino-American rivalry is not inevitable but depends on both sides’ policy choices. Accordingly, he voiced US concerns with particular aspects of Chinese foreign policy in a more forthright manner (Kerry 2014). Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 503 (Beckley 2011). Many PRC elites seem to realize this too and hence prefer to keep China committed to peaceful development, by working with rather than against America (Bader 2012:122–123; Sutter 2012:149–150). As noted recently by a renowned Singaporean expert, those “doves” still hold considerable sway in opposition to an aggressive, nationalist approach in Chinese foreign policy (Mahbubani 2014). Under the circumstances, sustained US engagement helps to strengthen the moderate Chinese groups and individuals by signaling that American intentions toward China are not inimical and that there is much room for promoting mutual understanding and benefit. Within this context, a belligerent Chinese posture toward America will appear less appealing or defensible in domestic debates. Engagement, in other words, reduces the likelihood of conflict by preventing the formation of a strong consensus among the ruling elites of an emerging power that the hegemon constitutes an unappeasable threat, a consensus that is a foremost necessary condition for balancing or confrontational behavior (Schweller 2004). Meanwhile, Washington should also conduct a candid and straightforward dialogue with Beijing, to tackle the apparent inconsistencies in China’s grand strategy on its own terms. What, for example, does the PRC want by espousing a new, “fair and just” international order, despite its deepening enmeshment in the current global system? What aspects of the existing order would Beijing wish to change, and in what ways (that is, through gradual reform or drastic overhaul)? And, last but not the least, what changes may look permissible to Washington, and what would overstep the red line of American tolerance? Such a dialogue would help both sides to assess each other’s strategic intentions with rigorous objectivity and to act upon the solidity of fact, rather than upon wishful thinking or misjudgments, in formulating future policies. For future research, this study suggests that China’s interactions with the developing world (and how those interactions relate to the ups and downs in US-China relations) warrant a deeper exploration. As argued earlier, a prudent rising state may choose not to overturn the existing world order by brute force but by covert competition. If that is the case, then it may not be possible, as some scholars contend, to maintain the current, largely Western-dominated system with a larger role for China (Ikenberry 2011:344–345; Nathan and Scobell 2012:356). For, conceivably, Beijing might work quietly with other developing nations to reduce the magnitude of US or Western supremacy, to prepare step by step for an ultimate systemic transformation. A recent study, for example, presents systematic evidence that as African and Latin American countries trade more with China, they become more likely to side with Beijing in voting on the UN General Assembly’s country-specific human rights resolutions, which are often a major point of contention between the West and the rest (Flores-Macias and Kreps 2013). It will be interesting, then, to examine how China interacts with like-minded 504 X. Li developing states in pivotal global institutions over time, to advance policy objectives that are at variance with Western preferences. The first step is to be on the lookout. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank John Vasquez, Paul Diehl, Mark Nieman, Gennady Rudkevich, Michael Colaresi, and three anonymous reviewers for many insightful comments and suggestions for improving this study. I also thank Xiaohong Zheng, Huaren Jin, and my mother for their generous research support. The appendix and replication files are available on the International Interactions Dataverse page at http://dvn.iq.harvard.edu/dvn/ dv/internationalinteractions. REFERENCES Bader, Jeffrey. (2012) Obama and China’s Rise: An Insider’s Account of America’s Asia Strategy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. Barbieri, Katherine. (2002) The Liberal Illusion: Does Trade Promote Peace? Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Barbieri, Katherine, and Omar Keshk. (2012) Correlates of War Project Trade Data Set Codebook, Version 3.0. Available at http://correlatesofwar.org. Beck, Nathaniel, Jonathan Katz, and Richard Tucker. (1998) Taking Time Seriously in Binary Time-Series-Cross-Section Analysis. American Journal of Political Science 42(4): 1260–1288. Beckley, Michael. (2011) China’s Century? Why America’s Edge Will Endure. International Security 36(3):41–78. Braumoeller, Bear. (2012) The Great Powers and the International System: Systemic Theory in Empirical Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Brooks, Stephen, and William Wohlforth. (2008) World Out of Balance: International Relations and the Challenge of American Primacy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Carter, David, and Curtis Signorino. (2010) Back to the Future: Modeling Time Dependence in Binary Data. Political Analysis 18(3):271–292. Christensen, Thomas. (2006) Windows and War: Trend Analysis and Beijing’s Use of Force. In New Directions in the Study of China’s Foreign Policy, edited by Alastair Iain Johnston and Robert Ross. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Clinton, Hillary. (2012) Remarks at the US Institute of Peace China Conference. Available at: http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2012/03/185402.htm. Deng, Xiaoping. (1993) Deng Xiaoping wenxuan [Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping], Vol. 3. Beijing: Renmin Chubanshe. Deng, Yong. (2008) China’s Struggle for Status: The Realignment of International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 505 Fingar, Thomas. (2012) China’s Vision of World Order. In China’s Military Challenge, edited by Ashley Tellis and Travis Tanner. Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research. Flores-Macías, Gustavo, and Sarah Kreps. (2013). The Foreign Policy Consequences of Trade: China’s Commercial Relations with Africa and Latin America, 1992–2006. Journal of Politics 75(2):357–371. Foot, Rosemary. (2006) Chinese Strategies in a US-Hegemonic Global Order: Accommodating and Hedging. International Affairs 82(1):77–94. Foot, Rosemary, and Andrew Walter. (2011) China, the United States, and the Global Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Fravel, Taylor. (2008) Secure Borders, Strong Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China’s Territorial Disputes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Friedberg, Aaron. (2011) A Contest for Supremacy: China, the United States, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia. New York: W. W. Norton. Gartzke, Erik. (2006) The Affinity of Nations Index, 1946–2008. Available at: http:// dss.ucsd.edu/∼egartzke/htmlpages/data.html. Gibler, Douglas. (2009) International Military Alliances, 1648–2008. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Press. Gilpin, Robert. (1981) War and Change in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Goldstein, Avery. (2005) Rising to the Challenge: China’s Grand Strategy and International Security. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Heston, Alan, Robert Summers, and Bettina Aten. (2012) Penn World Table Version 7.1. Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices, University of Pennsylvania. Holmes, Marcus. (2013) The Force of Face-to-Face Diplomacy: Mirror Neurons and the Problem of Intentions. International Organization 67(4):829–861. Hufbauer, Gary, Jeffrey Schott, and Kimberly Elliot. (2007) Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. Third Edition. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics. Hufbauer, Gary, Jeffrey Schott, Kimberly Elliot, and Julia Muir. (2012) Post2000 Sanctions Episodes. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics. Huang, Jing, and Xiaoting Li. (2010) Inseparable Separation: The Making of China’s Taiwan Policy. Singapore: World Scientific Press. Ikenberry, G. John, ed. (2002) America Unrivaled: The Future of the Balance of Power. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Ikenberry, G. John. (2011) Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Jiang, Zemin. (2006) Jiang Zemin wenxuan [Selected Works of Jiang Zemin], 3 vols. Beijing: Renmin Chubanshe. Johnston, Alastair Iain. (2003) Is China a Status Quo Power? International Security 27(4): 5–56. Johnston, Alastair Iain. (2008) Social States: China in International Institutions, 1980–2000. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 506 X. Li Kane, Tim. (2006) Global US Troop Deployment, 1950–2005. Available at: http:// www.heritage.org/research/reports/2006/05/global-us-troop-deployment-19502005. Kapstein, Ethan, and Michael Mastanduno, eds. (1999) Unipolar Politics. New York: Columbia University Press. Kastner, Scott, and Phillip Saunders. (2012) Is China a Status Quo or Revisionist State? Leadership Travel as an Empirical Indicator of Foreign Policy Priorities. International Studies Quarterly 56(1):163–177. Kirshner, Jonathan. (2012) The Tragedy of Offensive Realism: Classical Realism and the Rise of China. European Journal of International Relations 18(1):53–75. Kent, Ann. (2007) Beyond Compliance: China, International Organizations, and Global Security. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Keohane, Robert. (1984) After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Kerry, John. (2014) Remarks at the Opening Session of the Sixth US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue. Available at: http://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/ 2014/07/228910.htm. Kleine-Ahlbrandt, Stephanie, and Andrew Small. (2008) China’s New Dictatorship Diplomacy: Is Beijing Parting with Pariahs? Foreign Affairs 87(1):38–56. Kupchan, Charles. (2014) The Normative Foundations of Hegemony and The Coming Challenge to Pax Americana. Security Studies 23(2):219–257. Larson, Deborah Welch, and Alexei Shevchenko. (2010) Status Seekers: Chinese and Russian Responses to US Primacy. International Security 34(4):63–95. Lemke, Douglas. (2004) Great Powers in the Post-Cold War World: A Power Transition Perspective. In Balance of Power: Theory and Practice in the 21st Century, edited by T. V. Paul, James J. Wirtz, and Michel Fortmann. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Leng Rong, et al. (2004) Deng Xiaoping nianpu, 1975–1997 [A Chronology of Deng Xiaoping, 1975–997]. Beijing: Zhongyang Wenxian Chubanshe. Lieberthal, Kenneth, and Wang Jisi. (2012) Addressing US-China Strategic Distrust. Washington, DC: John L. Thornton China Center, Brookings Institution. Mahbubani, Kishore. (2014, July 18). Helping China’s Doves. New York Times. Available at: www.nytimes.com/2014/07/18/opinion/helping-chinasdoves.html. Mastanduno, Michael. (1997) Preserving the Unipolar Moment: Realist Theories and US Grand Strategy after the Cold War. International Security 21(4):49–88. Mearsheimer, John. (2001) The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W. W. Norton. Mearsheimer, John. (2010) The Gathering Storm: China’s Challenge to US Power in Asia. The Chinese Journal of International Politics 3(4):381–396. Medeiros, Evan. (2007) Reluctant Restraint: The Evolution of China’s Nonproliferation Policies and Practices, 1980–2004. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Medeiros, Evan. (2009) China’s International Behavior: Activism, Opportunism, and Diversification. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Monteiro, Nuno P. (2014) Theory of Unipolar Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Dealing with the Ambivalent Dragon 507 Morgenthau, Hans. (1948 [1978]) Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace. Fifth Edition. New York: Knopf. Mowle, Thomas S., and David H. Sacko. (2007) The Unipolar World: An Unbalanced Future. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Nathan, Andrew, and Andrew Scobell. (2012) China’s Search for Security. New York: Columbia University Press. Oppenheimer, Andres. (2014, July 19) China Is Flexing Its Muscle in Latin America. Miami Herald. Available at: http://www.miamiherald.com/2014/07/ 19/4243223/andres- oppenheimer-china-is-flexing.html. Pape, Robert. (2005) Soft Balancing against the United States. International Security 30(1): 7–45. Paul, T. V. (2005) Soft Balancing in the Age of US Primacy. International Security 30(1):46–71. Pevehouse, Jon, Timothy Nordstrom, and Kevin Warnke. (2004) The COW2 International Organizations Dataset Version 2.0. Conflict Management and Peace Science 21(2):101–119. Qian, Qichen. (2003) Waijiao Shiji [Ten Diplomatic Episodes]. Beijing: Shijie Zhishi Chubanshe. Roy, Denny. (2003) China’s Reaction to American Predominance. Survival 45(3):57–78. Russett, Bruce, and John Oneal. (2001) Triangulating Peace: Democracy, Interdependence, and International Organizations. New York: W. W. Norton. Schweller, Randall. (1999) Managing the Rise of Great Powers: History and Theory. In Engaging China: The Management of an Emerging Power, edited by Alastair Iain Johnston and Robert S. Ross. New York: Routledge. Schweller, Randall. (2004) Unanswered Threats: A Neoclassical Realist Theory of Underbalancing. International Security 29(2):159–201. Schweller, Randall, and Xiaoyu Pu. (2011) After Unipolarity: China’s Visions of International Oder in an Era of US Decline. International Security 36(1):41–72. Senese, Paul, and John Vasquez. (2008) Steps to War: An Empirical Study. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Shambaugh, David. (2005) China Engages Asia: Reshaping the Regional Order. International Security 29(3):64–99. Shambaugh, David. (2013) China Goes Global: The Partial Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Shirk, Susan. (2007) China: Fragile Superpower. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Strezhnev, Anton, and Erik Voeten. (2013) United Nations General Assembly Voting Data. Available at: http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/Voeten. Sutter, Robert. (2012) Chinese Foreign Relations: Power and Policy since the Cold War. Third Edition. New York: Rowman and Littlefield. Tammen, Ronald L., et al. (2000) Power Transitions: Strategies for the 21st Century. New York: Chatham House. Tang, Jiaxuan. (2009) Jin yu xu feng [Heavy Storm and Gentle Breeze]. Hong Kong: Commercial Press. Tessman, Brock. (2012) System Structure and System Strategy: Adding Hedging to the Menu. Security Studies 21(2):192–231. 508 X. Li Walt, Stephen. (2005) Taming American Power: The Global Response to US Primacy. New York: W.W. Norton. Waltz, Kenneth. (1997) Evaluating Theories. American Political Science Review 91(4):913–917. Wohlforth, William. (1999) The Stability of a Unipolar World. International Security 24(1):5–41. Zhong, Zhicheng. (2006) Weile shijie geng meihao: Jiang Zemin chufang jishi [For a Better World: Jiang Zemin’s Foreign Visits]. Beijing: Shijie Zhishi Chubanshe. Zoellick, Robert. (2005) Whither China: From Membership to Responsibility? Remarks to National Committee on US-China Relations. Available at: http://2001-2009. state.gov/s/d/former/zoellick/rem/53682.htm. Copyright of International Interactions is the property of Routledge and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.