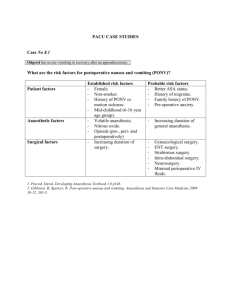

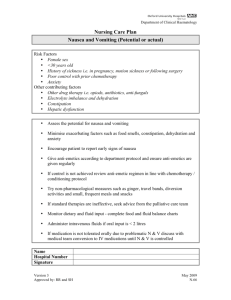

International Journal of Surgery 15 (2015) 100e106 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Surgery journal homepage: www.journal-surgery.net Review Post-operative nausea and vomiting: Update on predicting the probability and ways to minimize its occurrence, with focus on ambulatory surgery a, * € Emma Obrink , Pether Jildenstål b, Eva Oddby a, Jan G. Jakobsson a a b Department of Anaesthesia & Intensive Care, Institution for Clinical Science, Karolinska Institutet, Danderyds Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden € Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, University Hospital of Orebro, Sweden h i g h l i g h t s Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is still not uncommon after surgery and anaesthesia. It is still not possible to guarantee that an individual patient will not experience PONV. There are several factors contributing to the occurrence of PONV. There is a need for proper risk assessment. There is a need for further studies how to identify patients at risk. a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Received 15 November 2014 Received in revised form 6 January 2015 Accepted 26 January 2015 Available online 29 January 2015 Postoperative nausea and vomiting “the little big problem” after surgery/anaesthesia is still a common side-effect compromising quality of care, delaying discharge and resumption of activities of daily living. A huge number of studies have been conducted in order to identify risk factors, preventive and therapeutic strategies. The Apfel risk score and a risk based multi-modal PONV prophylaxis is advocated by evidence based guidelines as standards of care but is not always followed. Tailored anaesthesia and pain management avoiding too liberal dosing of anaesthetics and opioid analgesics is also essential in order to reduce risk. Thus multi-modal opioid sparing analgesia and a risk based PONV prophylaxis should be provided in order to minimise the occurrence. There is however still no way to guarantee an individual patient that he or she should not experience any PONV. Further studies are needed trying to identify risk factors and ways to tailor the individual patient prevention/therapy are warranted. The present paper provides a review around prediction, factors influencing the occurrence and the management of PONV with a focus on the ambulatory surgical patient. © 2015 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of Surgical Associates Ltd. Keywords: Postoperative nausea and vomiting PONV Ambulatory Anaesthesia Surgery Prediction Prophylaxis 1. Introduction Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is one of most frequent side effect after anaesthesia [1], occurring in 30% of unselected in patients and up to 70% of “high-risk” in patients during the 24 h after emergence [2]. Its incidence following ambulatory surgery is not uncommonly reported as lower than in inpatient surgery, but PONV may be under-recognized in the outpatient setting, where patients quickly leave direct medical oversight [3]. * Corresponding author. Department of Anaesthesia & Intensive Care, Dandryds Hospital, 182 88 Danderyd, Sweden. € E-mail address: Emma.obrink@ds.se (E. Obrink). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.01.024 1743-9191/© 2015 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of Surgical Associates Ltd. For the ambulatory patients Post Discharge Nausea and Vomiting [4] (PDNV) must also be acknowledged. Even though predischarge PONV predicts PDNV some patient do not experience emetic sequelae until after discharge. Nausea and vomiting may start and persist up to days after anaesthesia and thus strategies providing long-lasting protections should be sought (Figs. 1 and 2). The present paper aim at providing an overview around PONV with a focus on prediction and factors that influence the risk for and severity of PONV in the patient scheduled for ambulatory surgery and anaesthesia. Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is not only common but is one of most distracting side effects after surgery/anaesthesia [5]. Avoiding pain and PONV is highly prioritized [6]. PONV has € E. Obrink et al. / International Journal of Surgery 15 (2015) 100e106 101 not be the same and thus complicating analysis of different study results and comparing papers conclusion. Also clinical implication should be acknowledged; a short episode of mild nausea should possibly be weighed less than intense long-lasting/repeated episodes of vomiting. One episode of retching is likewise probably less distressing than hours of nausea. Vomiting may be objectively assessed during the hospital stay, while nausea and retching are subjective experience, assessed by questioning or recording of complaints. Relaying on personnel observation only may underestimate the true incidence [12]. The questioning may be conducted at several occasions or merely once, obtaining possibly somewhat different responses. Apfel et al. [13] provided a comprehensive review around methodology for studies on PONV in 2002. It seems obvious that method for assessing postoperative emesis and the observation period is of huge importance. One may argue that free of PONV is the ultimate outcome and any signs or symptom is a merely to be seen as a failure. Fig. 1. Major factors with impact on the risk for PONV. Fig. 2. The PONV prophylaxis/prevention escalating pyramid. major impact on quality of care [7] but it has also impact on patients transfer along the ambulatory pathway; delaying discharge [8] and may cause unanticipated admission [9,10]. PONV may also on rare occasions lead to dehydration; hypovolemia compromising safety. Numerous studies have been conducted aiming at increasing the understanding of the ethiology, trying to identify risk factors; patient related risks, surgery associated to high risk and anaesthesia/ analgesia related factors. There are also huge numbers of studies evaluating different preventive and therapeutic strategies. All of these are aiming at reducing the occurrence, severity and duration of emetic symptoms throughout the perioperative period [11]. PONV is usually “self-limiting” but may last for up to 2e3 days and thus interfere with resumption of activities of daily living [4]. 1.1. Method for assessment, how PONV should be followed and presented Postoperative nausea and vomiting - PONV - include a variety of symptoms; all from mild nausea up to severe repeated vomiting. When assessing studies around PONV study design and way of defining and recording the “outcome” is of importance. PONV may 1.2. Patient factors, likelihood of becoming nauseated The exact pathophysiology for emesis is not well understood. Vomiting e getting rid of potentially dangerous intake e is a defence mechanism. The emetic centre is most certainly scanning, reacting on, possibly irritating, dangerous triggers starting the emetic event [14]. There are a number of endogenous triggering substances. Multiple receptors in the chemo-trigger zone are involved and multiple substances have anti-emetic potentials [15,16] e.g. acetylcholine, dopamine, and serotonin. The exact triggering sequence for the individual patient is however not known. From populations studies we know that female, nonesmoking and younger age are known patient factors. Prediction of the risk for PONV has been suggested since long [17]. The best scoring system has been argued. The Apfel score; age <50 years of age, female, non-smoking, and history of PONV, has become highly accepted [18]. The Sinclair score include also length and type of surgery [19]. The risk factors for post discharge nausea and vomiting (PDNV) also been assessed by Apfel group. These include female gender, age less than 50 yr, history of nausea and/or vomiting after previous anaesthesia, opioid administration in the post-anaesthesia care unit and nausea in the post-anaesthesia care unit [20]. Female gender is associated to more PONV than men also among elderly patients [21]. Both the Apfel and Sinclair scores are not only feasible but most adequate tools for preoperative prediction and it may be worth doing a pre-discharge assessment providing patients information/advise and possibly rescue antiemetics if having a high risk score for PDNV. Emesis may from an evolutional perspective be seen as a protective measure, getting rid of inappropriate intakes. There are without doubt several patient factors having huge impact on risk that should be assessed and current risks scores should be implemented and adhered to. 1.3. Trigger factors, anaesthesia The impact of the composition of the fresh gas flow the FiO2 and whether nitrous oxide is mixed or not has been debated since long. Oxygen, high oxygen fraction, perioperative use of FiO2 0.8, has been studied in several studies. The meta-analysis from 2008 could not find clear evidence for any PONV preventive effect of a high FiO2 during surgery [22]. A more recent meta-analysis by Hovaguimian et al. published in 2013 concluded that an intra-operative high FIO2 decreases the risk of surgical site infections (SSI) in surgical patients receiving prophylactic antibiotics, has a weak beneficial effect on nausea, and does not increase the risk of 102 € E. Obrink et al. / International Journal of Surgery 15 (2015) 100e106 postoperative atelectasis [23]. It seems reasonable to conclude that we cannot explicitly state whether high oxygen fraction has an anti-emetic or merely a zero effect; not worsening the risk for PONV. The oxygen studies eliminate the potential impact of nitrous oxide. Nitrous oxide has a weak emetic potential, but whether it use as part of the fresh gas flow and thus reducing the need for more potent anaesthetics have any clinical relevant impact on the risk for PONV is less obvious. The ENIGMA-I trial showed “as expected according to Apfel risk score that age <55 yr, female sex were predictors but also that abdominal surgery, nitrous oxide administration, absence of BIS monitoring, and longer duration of anaesthesia were predictors of severe PONV [24]. The duration of nitrous oxide exposure seems to have an impact, less than 1 h use as part of the fresh gas has not been shown to increase the risk [25]. It may be similar to the other inhaled anaesthetics a matter of duration and concentration, thus nitrous oxide may be an option for the shorter ambulatory procedures [26]. There is also still sparse data showing clear evidence for any therapeutic effect from oxygen therapy in patients experiencing PONV, it is still not uncommonly part of the general manoeuvres made in patients retching or vomiting in the recovery area. Whether oxygen has any explicit effect on established PONV or is merely a part of a tradition and general care needs further studies. The major multi-factorial study by Apfel et al. showed that there is, regardless of anaesthetic technique and multi-modal triple prophylaxis, a residual group experiencing PONV [27]. It seems fair to state that inhaled anaesthetics have an emetic potential. In contrast to propofol that has been suggested to have a small but anti-emetic effect as long there is a low blood level. The debate around choice of anaesthetic for ambulatory surgery is continuing. Kumar et al. [28] published in 2014 October issue of Anaesthesia a meta-analysis concluding that based on the published evidence to date, maintenance of anaesthesia using propofol appeared to have no major impact on the incidence of unplanned admission to hospital. Propofol base anaesthesia was found to be associated with a decreased incidence of early postoperative nausea and vomiting compared with sevoflurane or desflurane in patients undergoing ambulatory surgery but the impact on discharge seems minor. It seems also as the effects are short-lasting, follow-up after ambulatory surgery at 24-h show commonly no difference [29e31]. Voigt et al. [32] found dual preventive anti-emetic therapy to provide similar and even numerically better PONV prevention when given prior to inhaled anaesthesia as compared to TIVA in females undergoing breast surgery. The choice of main anaesthetic inhaled or intravenous, propofol, seems further not to have major impact on oral intake day 1e2 after anaesthesia [33]. Avoiding early PONV is of value but propofol based anaesthesia is not sufficient to eliminate the occurrence on PONV. A more precise titration of depth of anaesthesia could have protective effects reducing the risk for PONV. The ENIGMA I study suggested that BIS monitoring had a significant impact reducing the incidence [34,35]. Whether this is a direct effect by reducing the amount of anaesthetic, decreasing the area under the curve delivered amount anaesthetic/analgesic or an indirect effect, lesser swings in circulation, stress, hypo/hypertension etc cannot from available information. The above data on fresh gas composition, anaesthetic technique, technique to titrate, and dose main anaesthetic is compiled from both in-patient and ambulatory surgery. The potential pharmacological impact is reasonably applicable for out as well as in-patient care. The duration, “area under the curve”, amount of exposure is of importance. Both the Sincalair score and the studies with depth-ofanaesthesia monitoring support this assumption. Anaesthetic technique has an impact both drugs used and how they are administered, how depth of anaesthesia is titrated. Propofol exhibit no emetic potential, inhaled anaesthetics, the potent halogenated as well as nitrous oxide has emetic effects, and all opioid substances do carry risk for nausea and vomiting. Minimising the dose and duration, fin-tuning administration is of value. 1.4. The airway, ventilation and gastric emptying There is sparse data around the independent effects of the airway; Larygeal mask airway vs. tube [36,37]. It seems more important to secure safety appropriate ventilation and avoidance of risk for regurgitation/aspiration. Likewise, whether assisted, controlled ventilation is associated to any different risk for PONV as compared to spontaneous breathing during surgery and anaesthesia has not been studied in prospective randomised studies having PONV as primary outcome. The potential impact of emptying the stomach by the use of a naso-gastric tube has not been shown to have major impact. Kerger et al. [38] published the results from the IMPACT study including more than 4000 patients with a special reference to the use of naso-gastric tube and these results provide evidence that routine use of an NG tube does not reduce the incidence of PONV. The explicit choice of airway, airway management seems not to have major impact on the occurrence of PONV. 1.5. Surgery aspects An outpatient study found that each 30-min increase in surgery duration increased baseline PONV risk by 60% and that plastic and orthopaedic shoulder surgery had a six-fold increase in the risk for PONV and duration of anaesthesia/surgery is included as risk factors in the Sinclair score [17]. Other studies have suggested that orthopaedic surgery is less emetogenic. Grabowska-Gaweł et al. [39] found a clear relation between the frequency of postoperative nausea and vomiting occurrence and the type of operative procedure. The relation appeared to be the strongest in case of the sick who underwent abdominal and laryngological procedures, as well as ophthalmologic procedures. However, the relation was the weakest in case of the sick who underwent orthopaedic procedures. Breast surgery has been shown to be associated to high incident, whether this is an effect of female gender and age or if the surgery as such has an independent effect cannot be explicitly stated [40]. It is however not easy to fully assess the independent effect, comparing the various studies as patient age, gender, smoking habits, anaesthetic technique, pain management and assessment of PONV commonly differ between studies [41]. Type of surgery have an influence on risk for PONV, abdominal surgery, breast surgery and ear nose and throat carry a high risk for PONV. Surgery associated to sever postoperative pain and need for higher doses of postoperative opioid, e.g. major orthopaedic surgery is also at risk. Preventive strategies should take surgical procedure into account, including an effective postoperative pain management plan possibly minimising need for opioids e.g. by nerve block and perineural catheter techniques. 1.6. Trigger agents Balanced analgesia, or multi-modal pain management, combining analgesics with different mode of action aiming at minimising the need for opioid analgesics was introduced in the mid 1990s [42,43]. Local anaesthesia in order to reduce pain and thus lower the need for opioids have become standard of care [44]. The optimal technique, central blocks, spinal or epidural, regional techniques or merely wound infiltration and catheters should be adopted on a procedural basis [45]. The implementation of laparoscopic techniques and Enhanced Recovery Program has made € E. Obrink et al. / International Journal of Surgery 15 (2015) 100e106 more extensive central block less appropriate [46]. Paracetamol, NSAIDs and Coxibs are commonly used for pain management for ambulatory surgery reducing the need for opioid and subsequently morphine related side effects [47,48]. Coxibs may have a benefit by less effect on platelets and thus risk for bleeding [49]. Complete opioid free anaesthesia has been shown to have favourable effect reducing PONV [50,51]. Reducing intraoperative opioid in combination with multi-modal analgesia has been shown to reduce PONV, postoperative nausea (68% vs. 27%) and vomiting (32% vs. 8%) in the first 24 postoperative hours, in females undergoing major breast [52]. Choice of intraoperative opioid seems not to have major impact, good evidence, however, exists to show that fentanyl and alfentanil do not cause more nausea and vomiting than the ultra fast-acting remifentanil [53,54]. Reversal agents, the use of standard 2.5 mg neostigmin and 0.5 mg glucopyrrolate for reversal of neuromuscular block seems not to increase the risk for PONV [55,56]. Postoperative use of opioids provides additional risk for PONV. Claxton et al. found fentanyl and morphine to be associated with similar risk for PONV but morphine caused more PDNV [57]. Multimodal opioid sparing analgesia, combining analgesics; paracetamol, NSAIDs/Coxibs and local anaesthesia has become standard of care in ambulatory surgery. Single shot local anaesthesia has a limited duration. Catheter techniques in order to prolong the duration may be used also in ambulatory surgery. Studies are ongoing with different slow release formulation of local anaesthesia. 1.7. Ethnicity A meta-analysis of PONV after gynaecological surgery [58] and a study in the laboratory-induced motion sickness setting [59] suggest that ethnicity (Dutch or English versus Scandinavian and Chinese or Asian-American versus Caucasian- or African-American, respectively) could be a PONV risk factor. Black South African ethnicity has also been shown as an independent risk factor for decreasing the incidence of PONV. The reason for this observation remains speculative and further investigation is warranted. The inclusion of ethnicity as a risk factor into PONV scoring systems has been suggested [60]. 1.8. Homeostasis Time without food and drink should follow revised, updated guidelines 6 h for food and 2 h for clear liquor. Whether preoperative “nutritional drinks” exhibits explicit benefits, e.g. reduced PONV needs further studies [61]. Fluids during anaesthesia volume and content has recently been reviewed in a meta-analysis suggest that a liberal crystalloid regime is favourable reducing PONV risk [62]. Hypotension may indeed as well as bradycardia trigger emesis and ephedrine has been shown to provide beneficial effects reducing PONV and hypotension [63], it provides similar effects as droperidol but less sedation [64]. Postoperative oral intake may delay discharge but seems not to have explicit effects on risk for PONV. Jin et al. found no significant difference in the frequency of PONV between the drinking and the nondrinking groups either in the hospital or after discharge [65]. Adherence to updated modern guidelines avoiding prolong fasting should be adopted, maintaining homeostasis and avoiding dehydration with the risk for drop in blood pressure during early ambulation is of huge importance. 103 1.9. None-pharmacological aspects Non-pharmacological techniques for alleviation of postoperative pain and distress are not extensively used. The potential benefit and low risk should however be acknowledged. Nonepharmacological manoeuvres with impact on PONV, anxiety/information/preparation, and acupuncture [66] should not be neglected. There is reassuring evidence for acupressor being effective in reducing the risk for PONV. The last Cochrane review was published in 2009 [67] and showed clear evidence for its efficacy, P6 acupoint stimulation prevented PONV. There was no reliable evidence for differences in risks of postoperative nausea or vomiting after P6 acupoint stimulation compared to antiemetic drugs. There is one more meta-analysis by Cheong et al. [68] published in 2013 supporting beneficial effects from acupressure. PC6 acupressure significantly reduced the number of cases of nausea and vomiting during the first 24 postoperative hours. The effects of “therapeutic suggestion” have also been studied but the results are fragile show only limited benefit [69,70]. It's surprising that simple non-pharmacological techniques such as the acupressure wrist band are not more commonly used. 1.10. The traditional anti-emetics recent meta-analysis and guidelines There are recent reviews around trigger substances and pharmacological interventions. There are several classical receptor antagonists apart from the 5-HT-3 blockers that have effect on PONV and systematic review around antiemetics and drug combination have recently been published [71e73]. A meta-analysis by DeOliviera et al. published late 2012 [74] showed that the old and wellestablished metoclopramide 10 is effective for prevention of PONV. Likewise the antiemetic effects of low <1 mg droperidol has been documented in a meta analysis by Shaub et al. [75]. Because adverse drug reactions are likely to be dose-dependent, there is an argument to stop using doses of more than 1 mg. Trans-dermal scopolamine (TDS) has also been evaluated in a meta-analysis by Apfel et al. [76]. TDS was associated with significant reductions in PONV with both early and late patch application during the first 24 h after the start of anaesthesia. TDS was associated with a higher prevalence of visual disturbances at 24e48 h after surgery, but no other AEs, compared with placebo. Steroids have received increasing attention having potential impact on pain, PONV but also possibly on the risk for neurocognitive side effects. The beneficial effects of single preoperative intravenous dexamethasone seem reassuringly proven [77,78]. The increase in blood glucose must be acknowledged. 1.11. New pharmacological options There is ongoing research looking for further improvement. Palonosetron is the most recently US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved 5-HT3 receptor antagonist for use in the management of PONV. It is interesting because of its long half life [79]. It is however not well proven whether the longer half-life translate in to clear clinical superiority. Park and Cho [80] found palonosetron more effective as compared to ondansetron. The incidence of PONV was significantly lower in the palonosetron group compared with the ondansetron group (42.2% vs 66.7%, respectively). Laha et al. [81] evaluated the efficacy of intravenous palonosetron (0.075 mg) versus ondansetron (4 mg) in preventing PONV during the first 24 h following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. They found not significantly different between the palonosetron and ondansetron groups, suggesting that the antiemetic efficacy of palonosetron is similar to that of ondansetron for preventing PONV, 104 € E. Obrink et al. / International Journal of Surgery 15 (2015) 100e106 despite the difference in pharmaco kinetics. Kang et al. [82] studied continuous palonosetron infusion, following single injection, reduces the incidence of PONV compared with single injection only in female patients undergo gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. However there were still about one third of patients that experienced PONV; the 24 h postoperatively was 31.8 vs. 56.1%, P ¼ 0.009 for the continuous palonosetron infusion group than the single-injection palonosetron group respectively. Candiotti et al. [83] studied intravenous palonosetron 0.075 mg and intravenous ondansetron 4 mg for the treatment in patients experiencing PONV following laparoscopic abdominal or gynaecological surgery despite prophylactic ondansetron. Palonosetron and ondansetron did not show differences in the primary efficacy endpoint during the 72 h after study drug administration. Neurokinin-1(NK1) receptor antagonists are today approved for the treatment and prevention of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. There are also studied evaluating apretenin for the prevention of PONV. The effect seems more pronounced for the reduction of vomiting while the effects on nausea and over all occurrence or PONV seem to be about the same as for 5-HT-3 blockers. Gan et al. [84] found aprepitant superior to ondansetron for prevention of vomiting in the first 24 and 48 h, but no significant differences were observed between aprepitant and ondansetron for nausea control, use of rescue, or complete response. Habib et al. [85] found the combination of aprepitant and dexamethasone more effective than was the combination of ondansetron and dexamethasone for prophylaxis against postoperative vomiting in adult patients undergoing craniotomy under general anaesthesia. However, there was no difference between the groups in the incidence or severity of nausea, need for rescue antiemetics, or in complete response between the groups. Thus the NK-1 receptor inhibitors seem to be highly effective reducing the occurrence of vomiting but with less of impact on the risk for any emetic symptoms. George et al. published in 2010 a review on new agents for the prevention and treatment of PONV [86]. There is one study of new dopamine receptor antagonistic effect. Kranke et al. [87] published the results from a randomized prospective study of three different doses (1, 5, or 20 mg) of investigational substance, amisulpride an antagonist at D2 and D3 receptors, in moderate-risk to high-risk adult surgical patients. The 5 mg dose was effective and superior to both the 1 and 20 mg doses still 14 percent vomited once or more and 24 needed rescue antiemetic therapy also in the 5 mg group of patients. The incidences of adverse events were similar for all study groups and no toxicities associated with D2-antagonists, such as extrapyramidal symptoms and psychological disturbances, were observed. There is as of today still no drug available eliminating the risk for PONV and the last addition of approved drugs as well as investigational substances are effective in reducing but seems not to provide any possibility to guarantee PONV free recovery. There is even far less of high quality research around treatment of established PONV. A general recommendation is to use drugs with a different mode of action than what has been administered for prevention/prophylaxis. The best effects may be gained with a 5HT-3-blocker in not used for prevention [88]. Multimodal risk score based prophylaxis should be adhered to, risk scoring and subsequent escalating prophylaxis and plan for rescue therapy should be part of each department standard internal guidelines. more or less impossible to cover all papers published. The present review aim merely at showing the complexity and the various aspects that needs to be kept in mind when planning for the individual patient care. There are recent updated guidelines [71,89] for risk assessment, risk based multi-modal PONV prophylaxis and the handling of patient experiencing PONV for the ambulatory patients both having received and for those who have not received preventive therapy. Still it is of importance to be aware of the fact that we cannot guarantee an individual patient that there will be no emetic side effects after anaesthesia. It is also of importance to have in mind that emetic symptoms do not only occur during the early phase during the hospital stay but may last and start also after discharge, post-discharge nausea and vomiting indeed have a most negative impact on quality of care [90]. The current guidelines are helpful but needs to be adhered to and followed in a proactive fashion [91,92]. There is still obvious room for further studies around how to identify patients at risk and more effective techniques to handle the at risk patient. Kranke [93] addressed the query about aggressive prevention or effective treatment in a recent editorial. The search for more specific makers in order to identify high risk patients and also the low risk individuals in order to better fine tune prevention is indeed of interest. A simple preoperative test would be of value. The serotonin gene type has been shown to impact the risk of post discharge PONV following breast cancer surgery [94]. Oddby et al. [95] studied whether chemotherapy provoked emesis and PONV interrelated and found no convincing overlap but they also found group of females relatively emetic resistant to both chemotherapy and anaesthesia/surgery. There seems room for further studies around association between motion sickness as well as hyperemsis gravidarum and PONV. Oddby et al. studied also blood markers and found that three different platelet-associated factors and an altered epinephrine pattern were found to be associated with the occurrence of PONV after breast cancer surgery [96] thus platelet pattern would be one potential that could be explored. Further studies looking for blood markers e.g. platelet profile, and possibly genetic subtypes associated to PONV and response to anti-emetics are warranted [97,98]. Ethical approval None required. Sources of funding None. Author contribution All authors have contributed equally to the writing of this “mini review”. Conflicts of interest Jan Jakobsson has received research grants from Baxter, Abbott, MSD, Phizer, MundiPharma, Maquet and PhaseIn, has been lecturing and taken part in advice board for these companies and is paid consultant, safety physician for Linde Healthcare. No further conflicts of interest. 1.12. Summary and conclusion Guarantor The number of studies and papers addressing nausea and vomiting in conjunction to surgery and anaesthesia is huge and it is NA. € E. Obrink et al. / International Journal of Surgery 15 (2015) 100e106 References [1] L.H. Eberhart, J. Hogel, W. Seeling, et al., Evaluation of three risk scores to predict postoperative nausea and vomiting, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 44 (2000) 480e488. [2] T.J. Gan, Postoperative nausea and vomiting: can it be eliminated? JAMA 287 (2002) 1233e1236. [3] N.V. Carroll, P. Miederhoff, F.M. Cox, J.D. Hirsch, Postoperative nausea and vomiting after discharge from outpatient surgery centers, Anesth. Analg. 80 (1995) 903e909. [4] J. Forren, L. Jalota, D.K. Moser, T.A. Lennie, L.A. Hall, J. Holtman, V. Hooper, C.C. Apfel, Incidence and predictors of postdischarge nausea and vomiting in a 7-day population, Odom. J. Clin. Anesth. 25 (2013) 551e559. [5] Y.H. Roh, H.S. Gong, J.H. Kim, K.P. Nam, Y.H. Lee, G.H. Baek, Factors associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing anambulatory hand surgery, Clin. Orthop. Surg. 6 (2014) 273e278. [6] K. Jenkins, D. Grady, J. Wong, R. Correa, S. Armanious, F. Chung, Post-operative recovery: day surgery patients' preferences, Br. J. Anaesth. 86 (2001) 272e274. [7] Y.H. Roh, H.S. Gong, J.H. Kim, K.P. Nam, Y.H. Lee, G.H. Baek, Factors associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing an ambulatory hand surgery, Clin. Orthop. Surg. 6 (2014) 273e278. [8] F. Chung, G. Mezei, Factors contributing to a prolonged stay after ambulatory surgery, Anesth. Analg. 89 (1999) 1352e1359. [9] D. Gupta, H. Haber, Emetogenicity-risk procedures in same day surgery center of an academic university hospital in United States: a retrospective cost-audit of postoperative nausea vomiting management, Middle East J. Anesthesiol. 22 (2014) 493e502. [10] R. Dzwonczyk, T.E. Weaver, E.G. Puente, S.D. Bergese, Postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis from an economic point of view, Am. J. Ther. 19 (2012) 11e15. [11] R.P. Hill, D.A. Lubarsky, B. Phillips-Bute, J.T. Fortney, M.R. Creed, P.S. Glass, T.J. Gan, Cost-effectiveness of prophylactic antiemetic therapy with ondansetron, droperidol, or placebo, Anesthesiology 92 (4) (2000 Apr) 958e967. [12] M. Franck, F.M. Radtke, C.C. Apfel, et al., Documentation of postoperative nausea and vomiting in routine clinical practice, J. Int. Med. Res. 38 (2010) 1034e1041. [13] C.C. Apfel, N. Roewer, K. Korttila, How to study postoperative nausea and vomiting, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 46 (2002) 921e928. [14] M.G. Palazzo, L. Strunin, Anaesthesia and emesis. I: etiology, Can. Anaesth. Soc. J. 31 (1984) 178e187. [15] K. Neoh, L. Adkinson, V. Montgomery, A. Hurlow, Management of nausea and vomiting in palliative care, Br. J. Hosp. Med. 75 (2014) 391e392. [16] A. Skolnik, T.J. Gan, Update on the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting, Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 27 (2014) 605e609. [17] D.R. Sinclair, F. Chung, G. Mezei, Can postoperative nausea and vomiting be predicted? Anesthesiology 91 (1999) 109e118. €gel, W. Seeling, A.M. Staack, G. Geldner, M. Georgieff, [18] L.H. Eberhart, J. Ho Evaluation of three risk scores to predict postoperative nausea and vomiting, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 44 (2000) 480e488. [19] S. Pierre, H. Benais, J. Pouymayou, Apfel's simplified score may favourably predict the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting, Can. J. Anaesth. 49 (2002) 237e242. [20] C.C. Apfel, B.K. Philip, O.S. Cakmakkaya, A. Shilling, Y.Y. Shi, J.B. Leslie, M. Allard, A. Turan, P. Windle, J. Odom-Forren, V.D. Hooper, O.C. Radke, J. Ruiz, A. Kovac, Who is at risk for postdischarge nausea and vomiting after ambulatory surgery? Anesthesiology 117 (2012) 475e486. [21] D. Conti, P. Ballo, R. Boccalini, A. Boccherini, S. Cantini, A. Venni, S. Pezzati, S. Gori, F. Franconi, A. Zuppiroli, A. Pedull a, The effect of patient sex on the incidence of early adverse effects in a population of elderly patients, Anaesth. Intensive Care 42 (2014) 455e459. [22] M. Orhan-Sungur, P. Kranke, D. Sessler, C.C. Apfel, Does supplemental oxygen reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, Anesth. Analg. 106 (2008) 1733e1738. r, Effect of intraoperative [23] F. Hovaguimian, C. Lysakowski, N. Elia, M.R. Trame high inspired oxygen fraction on surgical site infection, postoperative nausea and vomiting, and pulmonary function: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, Anesthesiology 119 (2013) 303e316. [24] K. Leslie, P.S. Myles, M.T. Chan, M.J. Paech, P. Peyton, A. Forbes, D. McKenzie, ENIGMA Trial Group, Risk factors for severe postoperative nausea and vomiting in a randomized trial of nitrous oxide-based vs nitrous oxide-free anaesthesia, Br. J. Anaesth. 101 (2008) 498e505. [25] P.J. Peyton, C.Y. Wu, Nitrous oxide-related postoperative nausea and vomiting depends on duration of exposure, Anesthesiology 120 (2014) 1137e1145. [26] R.J. Arellano, M.L. Pole, S.E. Rafuse, M. Fletcher, Y.G. Saad, M. Friedlander, A. Norris, F.F. Chung, Omission of nitrous oxide from a propofol-based anesthetic does not affect the recovery of women undergoing outpatient gynecologic surgery, Anesthesiology 93 (2000) 332e339. [27] C.C. Apfel, K. Korttila, M. Abdalla, H. Kerger, A. Turan, I. Vedder, C. Zernak, K. Danner, R. Jokela, S.J. Pocock, S. Trenkler, M. Kredel, A. Biedler, D.I. Sessler, N. Roewer, IMPACT Investigators, A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting, N. Engl. J. Med. 350 (2004) 2441e2451. [28] G. Kumar, C. Stendall, R. Mistry, K. Gurusamy, D. Walker, A comparison of total intravenous anaesthesia using propofol with sevoflurane or desflurane in [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [46] [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52] [53] 105 ambulatory surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis, Anaesthesia 69 (2014) 1138e1150. J.C. Raeder, O. Mjåland, V. Aasbø, B. Grøgaard, T. Buanes, Desflurane versus propofol maintenance for outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 42 (1998) 106e110. J. Raeder, A. Gupta, F.M. Pedersen, Recovery characteristics of sevoflurane- or propofol-based anaesthesia for day-care surgery, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 41 (1997) 988e994. €ki, The effects of propofol vs. S.M. Pokkinen, A. Yli-Hankala, M.L. Kallioma sevoflurane on post-operative pain and need of opioid, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 58 (2014) 980e985. € hlich, K.F. Waschke, C. Lenz, U. Go €bel, H. Kerger, Prophylaxis M. Voigt, C.W. Fro of postoperative nausea and vomiting in elective breast surgery, J. Clin. Anesth. 23 (2011) 461e468. T. Yatabe, K. Yamashita, M. Yokoyama, Influence of desflurane on postoperative oral intake compared with propofol, Asia Pac J. Clin. Nutr. 23 (2014) 408e412. K. Leslie, P.S. Myles, M.T. Chan, M.J. Paech, P. Peyton, A. Forbes, D. McKenzie, ENIGMA Trial Group, Risk factors for severe postoperative nausea and vomiting in a randomized trial of nitrous oxide-based vs nitrous oxide-free anaesthesia, Br. J. Anaesth. 101 (2008) 498e505. K.A. Nelskyl€ a, A.M. Yli-Hankala, P.H. Puro, K.T. Korttila, Sevoflurane titration using bispectral index decreases postoperative vomiting in phase II recovery after ambulatory surgery, Anesth. Analg. 93 (2001) 1165e1169. J.D. Griffiths, M. Nguyen, H. Lau, S. Grant, D.I. Williams, A prospective randomised comparison of the LMA ProSeal™ versus endotracheal tube on the severity of postoperative pain following gynaecological laparoscopy, Anaesth. Intensive Care 41 (2013) 46e50. J. Porhomayon, P.K. Wendel, L. Defranks-Anain, K.B. Leissner, N.D. Nader, Do the choices of airway affect the post-anesthetic occurrence of nausea after knee arthroplasty? A comparison between endotracheal tubes and laryngeal mask airways, Middle East J. Anesthesiol. 22 (2013) 263e271. K.H. Kerger, E. Mascha, B. Steinbrecher, T. Frietsch, O.C. Radke, K. Stoecklein, C. Frenkel, G. Fritz, K. Danner, A. Turan, C.C. Apfel, IMPACT Investigators, Routine use of nasogastric tubes does not reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting, Anesth. Analg. 109 (2009) 768e773. A. Grabowska-Gaweł, K. Porzych, G. Piskunowicz, Risk factors and frequency of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients operated under general anesthesia, Przegl Lek. 63 (2006) 72e76. E. Oddby-Muhrbeck, J. Jakobsson, L. Andersson, J. Askergren, Postoperative nausea and vomiting. A comparison between intravenous and inhalation anaesthesia in breast surgery, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 38 (1994) 52e56. T.J. Gan, Risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting, Anesth. Analg. 102 (2006) 1884e1898. H. Eriksson, A. Tenhunen, K. Korttila, Balanced analgesia improves recovery and outcome after outpatient tubal ligation, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 40 (1996) 151e155. C. Michaloliakou, F. Chung, S. Sharma, Preoperative multimodal analgesia facilitates recovery after ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Anesth. Analg. 82 (1996) 44e51. N.T. Ventham, S. O'Neill, N. Johns, R.R. Brady, K.C. Fearon, Evaluation of novel local anesthetic wound infiltration techniques for postoperative pain following colorectal resection surgery: a meta-analysis, Dis. Colon Rectum 57 (2014) 237e250. N.T. Ventham, M. Hughes, S. O'Neill, N. Johns, R.R. Brady, S.J. Wigmore, Systematic review and meta-analysis of continuous local anaesthetic wound infiltration versus epidural analgesia for postoperative pain following abdominal surgery, Br. J. Surg. 100 (2013) 1280e1289. M. Hübner, C. Blanc, D. Roulin, M. Winiker, S. Gander, N. Demartines, Randomized clinical trial on epidural versus patient-controlled analgesia for laparoscopic colorectal surgery within an enhanced recovery pathway, Ann. Surg. (2014) 1e6, http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000838 (Epub ahead of print). C.C. Apfel, A. Turan, K. Souza, J. Pergolizzi, C. Hornuss, Intravenous acetaminophen reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Pain 154 (2013) 677e689. M. Warren-Stomberg, M. Brattwall, J.G. Jakobsson, Non-opioid analgesics for pain management following ambulatory surgery: a review, Minerva Anestesiol. 79 (2013) 1077e1087. n Stomberg, M. Brattwall, J. Jakobsson, Coxibs: is there a L. Wickerts, M. Warre benefit when compared to traditional non-selective NSAIDs in postoperative pain management? Minerva Anestesiol. 77 (2011) 1084e1098. I. Smith, G. Walley, S. Bridgman, Omitting fentanyl reduces nausea and vomiting, without increasing pain, after sevoflurane for day surgery, Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 25 (10) (2008 Oct) 790e799. P. Ziemann-Gimmel, A.A. Goldfarb, J. Koppman, R.T. Marema, Opioid-free total intravenous anaesthesia reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting in bariatric surgery beyond triple prophylaxis, Br. J. Anaesth. 112 (2014) 906e911. G. Shirakami, Y. Teratani, H. Segawa, S. Matsuura, T. Shichino, K. Fukuda, Omission of fentanyl during sevoflurane anesthesia decreases the incidences of postoperative nausea and vomiting and accelerates postanesthesia recovery in major breast cancer surgery, J. Anesth. 20 (2006) 188e195. R. Komatsu, A.M. Turan, M. Orhan-Sungur, J. McGuire, O.C. Radke, C.C. Apfel, Remifentanil for general anaesthesia: a systematic review, Anaesthesia 62 (2007) 1266e1280. 106 € E. Obrink et al. / International Journal of Surgery 15 (2015) 100e106 [54] K.D. Johnston, The potential for mu-opioid receptor agonists to be anti-emetic in humans: a review of clinical data, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 54 (2010) 132e140. €, A. Yli-Hankala, A. Soikkeli, K. Korttila, Neostigmine with glyco[55] K. Nelskyla pyrrolate does not increase the incidence or severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting in outpatients undergoing gynaecological laparoscopy, Br. J. Anaesth. 81 (1998) 757e760. [56] G.P. Joshi, S.A. Garg, A. Hailey, S.Y. Yu, The effects of antagonizing residual neuromuscular blockade by neostigmine and glycopyrrolate on nausea and vomiting after ambulatory surgery, Anesth. Analg. 89 (1999) 628e631. [57] A.R. Claxton, G. McGuire, F. Chung, C. Cruise, Evaluation of morphine versus fentanyl for postoperative analgesia after ambulatory surgical procedures, Anesth. Analg. 84 (1997) 509e514. [58] C.G. Haigh, L.A. Kaplan, J.M. Durham, et al., Nausea and vomiting after gynaecological surgery: a meta-analysis of factors affecting their incidence, Br. J. Anaesth. 71 (1993) 517e522. [59] R.M. Stern, The psychophysiology of nausea, Acta Biol. Hung. 53 (2002) 589e599. [60] R.N. Rodseth, P.D. Gopalan, H.M. Cassimjee, S. Goga, Reduced incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in black South Africans and its utility for a modified risk scoring system, Anesth. Analg. 110 (2010) 1591e1594. [61] G.P. Pimenta, J.E. de Aguilar-Nascimento, Prolonged preoperative fasting in elective surgical patients: why should we reduce it? Nutr. Clin. Pract. 29 (2014) 22e28. [62] C.C. Apfel, A. Meyer, M. Orhan-Sungur, L. Jalota, R.P. Whelan, S. Jukar-Rao, Supplemental intravenous crystalloids for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: quantitative review, Br. J. Anaesth. 108 (2012) 893e902. [63] K. Naguib, H.A. Osman, H.C. Al-Khayat, A.M. Zikri, Prevention of post-operative nausea and vomiting following laparoscopic surgeryeephedrine vs propofol, Middle East J. Anesthesiol. 14 (1998) 219e230. [64] D.M. Rothenberg, S.M. Parnass, K. Litwack, R.J. McCarthy, L.M. Newman, Efficacy of ephedrine in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting, Anesth. Analg. 72 (1991) 58e61. [65] F. Jin, A. Norris, F. Chung, T. Ganeshram, Should adult patients drink fluids before discharge from ambulatory surgery? Anesth. Analg. 87 (2) (1998 Aug) 306e311. [66] I. Liodden, A.J. Norheim, Acupuncture and related techniques in ambulatory anesthesia, Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 26 (2013) 661e668. [67] A. Lee, L.T. Fan, Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2) (2009) CD003281, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub3. [68] K.B. Cheong, J.P. Zhang, Y. Huang, Z.J. Zhang, The effectiveness of acupuncture in prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomitingea systematic review and meta-analysis, PLoS One 8 (2013) e82474. [69] E. Oddby-Muhrbeck, J. Jakobsson, B. Enquist, Implicit processing and therapeutic suggestion during balanced anaesthesia, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 39 (1995) 333e337. [70] U. Nilsson, N. Rawal, L.E. Uneståhl, C. Zetterberg, M. Unosson, Improved recovery after music and therapeutic suggestions during general anaesthesia: a double-blind randomised controlled trial, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 45 (2001) 812e817. [71] T.P. Le, T.J. Gan, Update on the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting and postdischarge nausea and vomiting in ambulatory surgery, Anesthesiol. Clin. 28 (2010) 225e249. [72] C.C. Horn, W.J. Wallisch, G.E. Homanics, J.P. Williams, Pathophysiological and neurochemical mechanisms of postoperative nausea and vomiting, Eur. J. Pharmacol. 722 (2014) 55e66. [73] A.L. Kovac, Update on the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting, Drugs 73 (2013) 1525e1547. [74] G.S. De Oliveira Jr., L.J. Castro-Alves, R. Chang, E. Yaghmour, R.J. McCarthy, Systemic metoclopramide to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis without Fujii's studies, Br. J. Anaesth. 109 (2012) 688e697. r, Low-dose droperidol (1 mg or [75] I. Schaub, C. Lysakowski, N. Elia, M.R. Trame 15 mg kg1) for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in adults: quantitative systematic review of randomised controlled trials, Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 29 (2012) 286e294. [76] C.C. Apfel, K. Zhang, E. George, S. Shi, L. Jalota, C. Hornuss, K.E. Fero, F. Heidrich, J.V. Pergolizzi, O.S. Cakmakkaya, P. Kranke, Transdermal scopolamine for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Clin. Ther. 32 (2010) 1987e2002. [77] N.H. Waldron, C.A. Jones, T.J. Gan, T.K. Allen, A.S. Habib, Impact of perioperative dexamethasone on postoperative analgesia and side-effects: systematic review and meta-analysis, Br. J. Anaesth. 110 (2013) 191e200. [78] J. Jakobsson, Preoperative single-dose intravenous dexamethasone during ambulatory surgery: update around the benefit versus risk, Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 23 (2010) 682e686. [79] C. Rojas, A.G. Thomas, J. Alt, M. Stathis, J. Zhang, E.B. Rubenstein, S. Sebastiani, S. Cantoreggi, B.S. Slusher, Palonosetron triggers 5-HT(3) receptor internalization and causes prolonged inhibition of receptor function, Eur. J. Pharmacol. 626 (2010) 193e199. [80] S.K. Park, E.J. Cho, A randomized, double-blind trial of palonosetron compared with ondansetron in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynaecological laparoscopic surgery, J. Int. Med. Res. 39 (2011) 399e407. [81] B. Laha, A. Hazra, S. Mallick, Evaluation of antiemetic effect of intravenous palonosetron versus intravenous ondansetron in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial, Indian J. Pharmacol. 45 (2013) 24e29. [82] J.W. Kang, S.K. Park, Evaluation of the ability of continuous palonosetron infusion, using a patient-controlled analgesia device, to reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting, Korean J. Anesthesiol. 67 (2014) 110e114. [83] K.A. Candiotti, S.R. Ahmed, D. Cox, T.J. Gan, Palonosetron versus ondansetron as rescue medication for postoperative nausea and vomiting: a randomized, multicenter, open-label study, BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 15 (2014) 45. [84] T.J. Gan, C.C. Apfel, A. Kovac, B.K. Philip, N. Singla, H. Minkowitz, A.S. Habib, J. Knighton, A.D. Carides, H. Zhang, K.J. Horgan, J.K. Evans, F.C. Lawson, Aprepitant-PONV Study Group, A randomized, double-blind comparison of the NK1 antagonist, aprepitant, versus ondansetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting, Anesth. Analg. 104 (2007) 1082e1089. [85] A.S. Habib, J.C. Keifer, C.O. Borel, W.D. White, T.J. Gan, A comparison of the combination of aprepitant and dexamethasone versus the combination of ondansetron and dexamethasone for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing craniotomy, Anesth. Analg. 112 (2011) 813e818. [86] E. George, C. Hornuss, C.C. Apfel, Neurokinin-1 and novel serotonin antagonists for postoperative and postdischarge nausea and vomiting, Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 23 (2010) 714e721. [87] P. Kranke, L. Eberhart, J. Motsch, D. Chassard, J. Wallenborn, P. Diemunsch, N. Liu, D. Keh, H. Bouaziz, M. Bergis, G. Fox, T.J. Gan, I.V. APD421 (amisulpride) prevents postoperative nausea and vomiting: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial, Br. J. Anaesth. 111 (2013) 938e945. [88] J. Jokinen, A.F. Smith, N. Roewer, L.H. Eberhart, P. Kranke, Management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: how to deal with refractory PONV, Anesthesiol. Clin. 30 (2012) 481e493. [89] T.J. Gan, P. Diemunsch, A.S. Habib, A. Kovac, P. Kranke, T.A. Meyer, M. Watcha, F. Chung, S. Angus, C.C. Apfel, S.D. Bergese, K.A. Candiotti, M.T. Chan, P.J. Davis, V.D. Hooper, S. Lagoo-Deenadayalan, P. Myles, G. Nezat, B.K. Philip, r, Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia, Consensus guidelines for the M.R. Trame management of postoperative nausea and vomiting, Anesth. Analg. 118 (2014) 85e113. [90] I. Parra-Sanchez, R. Abdallah, J. You, A.Z. Fu, M. Grady, K. Cummings 3rd, C. Apfel, D.I. Sessler, A time-motion economic analysis of postoperative nausea and vomiting in ambulatory surgery, Can. J. Anaesth. 59 (2012) 366e375. [91] B. Kolanek, L. Svartz, F. Robin, F. Boutin, L. Beylacq, A. Lasserre, M.C. KrolHoudek, V. Berger, V. Altuzarra, O. Jecker, M. Sesay, P.M. Mertes, R. Rossignol, K. Nouette-Gaulain, Management program decreases postoperative nausea and vomiting in high-risk and in general surgical patients: a quality improvement cycle, Minerva Anestesiol. 80 (2014) 337e346. [92] D.J. Myklejord, L. Yao, H. Liang, I. Glurich, Consensus guideline adoption for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting, WMJ 111 (2012) 207e213. [93] P. Kranke, General multimodal or scheduled risk-adopted postoperative nausea and vomiting prevention: just splitting hairs? Br. J. Anaesth. 114 (2015) 190e193. [94] S.W. Wesmiller, C.M. Bender, S.M. Sereika, G. Ahrendt, M. Bonaventura, D.H. Bovbjerg, Y. Conley, Association between serotonin transport polymorphisms and postdischarge nausea and vomiting in women following breast cancer surgery, Oncol. Nurs. Forum 41 (2014) 195e202. € €nnqvist, Is there [95] E. Oddby-Muhrbeck, E. Obrink, S. Eksborg, S. Rotstein, P.A. Lo an association between PONV and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting? Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 57 (2013) 749e753. [96] E. Oddby-Muhrbeck, S. Eksborg, A. Helander, P. Bjellerup, S. Lindahl, €nnqvist, Blood-borne factors possibly associated with post-operative P. Lo nausea and vomiting: an explorative study in women after breast cancer surgery, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 49 (2005) 1346e1354. [97] J. Raeder, How do we move further in research on post-operative nausea and vomiting? Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 49 (2005) 1403e1404. [98] T.J. Gan, Mechanisms underlying postoperative nausea and vomiting and neurotransmitter receptor antagonist-based pharmacotherapy, CNS Drugs 21 (2007) 813e833.