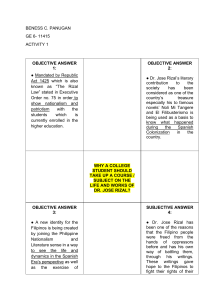

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE RIZAL SUBJECT THE RIZAL BILL was as controversial as Jose Rizal himself. The mandatory Rizal subject in the Philippines was the upshot of this bill which later became a law in 1956. The bill involves mandating educational institutions in the country to offer a course on the hero’s life, works, and writings, especially the ‘Noli Me Tangere’ and ‘El Filibusterismo’. The transition from being a bill to becoming a republic act was however not easy as the proposal was met with intense opposition particularly from the Catholic Church. Largely because of the issue, the then senator Claro M. Recto—the main proponent of the Rizal Bill—was even dubbed as a communist and an antiCatholic. Catholic schools threatened to stop operation if the bill was passed, though Recto calmly countered the threat, stating that if that happened, then the schools would be nationalized. Afterward threatened to be punished in future elections, Recto remained undeterred. Concerning the suggestion to use instead the expurgated (edited) version of Rizal’s novels as mandatory readings, Recto explained his firm support for the unexpurgated version, exclaiming: “The people who would eliminate the books of Rizal from the schools would blot out from our minds the memory of the national hero. This is not a fight against Recto but a fight against Rizal.” (Ocampo, 2012, p. 23) The bill was eventually passed, but with a clause that would allow exemptions to students who think that reading the Noli and Fili would ruin their faith. In other words, one can apply to the Department of Education for exemption from reading Rizal’s novels—though not from taking the Rizal subject. The bill was enacted on June 12, 1956. RA 1425 AND OTHER RIZAL LAWS The Rizal Bill became the Republic Act No. 1425, known as the ‘Rizal Law’. The full name of the law is “An Act to Include in the Curricula of All Public and Private Schools, Colleges and Universities Courses on the Life, Works and Writings of Jose Rizal, Particularly His Novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, Authorizing the Printing and Distribution Thereof, and for Other Purposes.” The first section of the law concerns mandating the students to read Rizal’s novels. The last two sections involve making Rizal’s writings accessible to the general 1 public—they require the schools to have a sufficient number of copies in their libraries and mandate the publication of the works in major Philippine languages. Jose P. Laurel, then senator who co-wrote the law, explained that since Jose Rizal was the founder of the country’s nationalism and had significantly contributed to the current condition of the nation, it is only right that Filipinos, especially the youth, know about and learn to imbibe the great ideals for which the hero died. Accordingly, the Rizal Law aims to accomplish the following goals: 1. To rededicate the lives of youth to the ideals of freedom and nationalism, for which our heroes lived and died 2. To pay tribute to our national hero for devoting his life and works in shaping the Filipino character 3. To gain an inspiring source of patriotism through the study of Rizal’s life, works, and writings. So far, no student has yet officially applied for exemption from reading Rizal’s novels. Correspondingly, former President Fidel V. Ramos in 1994, through Memorandum Order No. 247, directed the Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports and the Chairman of the Commission on Higher Education to fully implement the RA 1425 as there had been reports that the law had still not been totally carried out. In 1995, CHED Memorandum No. 3 was issued enforcing strict compliance to Memorandum Order No. 247. Not known to many, there is another republic act that concerns the national hero. Republic Act No. 229 is an act prohibiting cockfighting, horse racing, and jai-alai on the thirtieth day of December of each year and to create a committee to take charge of the proper celebration of Rizal Day in every municipality and chartered city, and for other purposes. The Importance of Studying Rizal The academic subject on the life, works, and writings of Jose Rizal was not mandated by law for nothing. Far from being impractical, the course interestingly offers many benefits that some contemporary academicians declare that the subject, especially when taught properly, is more beneficial than many subjects in various curricula. The following are just some of the significance of the academic subject: 1. The subject provides insights on how to deal with current problems 2 There is a dictum, “He who controls the past controls the future.” Our view of history forms the manner we perceive the present, and therefore influences the kind of solutions we provide for existing problems. Jose Rizal course, as a history subject, is full of historical information from which one could base his decisions in life. In various ways, the subject, for instance, teaches that being educated is a vital ingredient for a person or country to be really free and successful. 2. It helps us understand better ourselves as Filipinos The past helps us understand who we are. We comprehensively define ourselves not only in terms of where we are going, but also where we come from. Our heredity, past behaviors, and old habits as a nation are all significant clues and determinants to our present situation. Interestingly, the life of a very important national historical figure like Jose Rizal contributes much to shedding light on our collective experience and identity as Filipino. The good grasp of the past offered by this subject would help us in dealing wisely with the present. 3. It teaches nationalism and patriotism Nationalism involves the desire to attain freedom and political independence, especially by a country under foreign power, while patriotism denotes proud devotion and loyalty to one’s nation. Jose Rizal’s life, works, and writings—especially his novels—essentially, if not perfectly, radiate these traits. For one thing, the subject helps us to understand our country better. 4. It provides various essential life lessons We can learn much from the way Rizal faced various challenges in life. As a controversial figure in his time, he encountered serious dilemmas and predicaments but responded decently and high-mindedly. Through the crucial decisions he made in his life, we can sense his priorities and convictions which manifest how noble, selfless, and great the national hero was. For example, his many resolutions exemplified the aphorism that in this life there are things more important than personal feeling and happiness. 5. It helps in developing logical and critical thinking 3 Critical Thinking refers to discerning, evaluative, and analytical thinking. A Philosophy major, Jose Rizal unsurprisingly demonstrated his critical thinking skills in his argumentative essays, satires, novels, speeches, and written debates. In deciding what to believe or do, Rizal also proved his being a reasonably reflective thinker, never succumbing to the irrational whims and baseless opinions of anyone. In fact, he indiscriminately evaluated and criticized even the doctrines of the dominant religion of his time. A course on Rizal’s life, works, and writings therefore is also a lesson in critical thinking. 6. Rizal can serve as a worthwhile model and inspiration to every Filipino If one is looking for someone to imitate, then Rizal is a very viable choice. The hero’s philosophies, life principles, convictions, thoughts, ideals, aspirations, and dreams are a good influence to anyone. Throughout his life, he valued nationalism and patriotism, respect for parents, love for siblings, and loyalty to friends, and maintained a sense of chivalry. As a man of education, he highly regarded academic excellence, logical and critical thinking, philosophical and scientific inquiry, linguistic study, and cultural research. As a person, he manifested versatility and flexibility while sustaining a strong sense of moral uprightness. 7. The subject is a rich source of entertaining narratives People love fictions and are even willing to spend for books or movie tickets just to be entertained by made-up tales. But only a few perhaps know that Rizal’s life is full of fascinating non-fictional accounts. For instance, it is rarely known that (1) Rizal was involved in a love triangle with Antonio Luna as also part of the romantic equation; (2) Rizal was a model in some of Juan Luna’s paintings; (3) Rizal’s common-law wife Josephine Bracken was ‘remarried’ to a man from Cebu and had tutored former President Sergio Osmeña; (4) Leonor Rivera (‘Maria Clara’), Rizal’s ‘true love’, had a son who married the sister of the former President of the United Nations General Assembly Carlos P. Romulo; (5) the Filipina beauty queen Gemma Cruz Araneta is a descendant of Rizal’s sister, Maria; (6) the sportscaster Chino Trinidad is a descendant of Rizal’s ‘first love’ (Segunda Katigbak); and (7) the original manuscripts of Rizal’s novel (Noli and Fili) were once stolen for ransom, but Alejandro Roces had retrieved them without paying even a single centavo. 4 CHAPTER II 19th CENTURY PHILIPPINES AS RIZAL’S CONTEXT Nineteenth Century is commonly depicted as the birth of modern life, as well as the birth of many nation-states around the globe. The century was also a period of massive changes in Europe, Spain and consequently in the Philippines. It was during this era that the power and glory of Spain, the Philippines’ colonizers had waned both in its colonies and in the world. The Economic Context End of Galleon Trade Our locals were already trading with China, Japan and Siam (now Thailand), India. Cambodia, Borneo, and the Moluccas (Spice Islands) when the Spanish Colonizers came to the Philippines. In 1565, the Spanish government closed the ports of Manila to all countries except Mexico thereby giving birth to the ManilaAcapulco Trade popularly known as Galleon Trade. The Galleon Trade (1565-1815) was a ship (galleon) trade going back and forth between Manila (which actually landed first in Cebu) and Acapulco, Mexico. It started when Andres de Urdaneta, in convoy under Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, discovered a return route from Cebu to Mexico in 1565. The trade served as the central income-generating business for Spanish colonists in the Philippines. Other consequences of this 250-year trade were the intercultural exchanges between Asia (especially Philippines), Spanish America, and onward to Europe and Africa. Because of Galleon Trade, Manila became a trading hub where China, India, Japan, and South East Asian countries sent their goods to be consolidated for shipping. Those who ran the hub and did most of the work were primarily Chinese. They arrived in the Philippines in junks yearly, bringing goods and workforce. With the huge migration of Chinese because of the Galleon Trade, the Spaniards feared them, taxed them, sent them out to the parian and eventually, when tensions rose, massacred some of them. Such massacres were at their height in the 17th century from suspicion, unease and fear until the Spaniards and the Chinese learned to live with each other in the next few centuries. 5 The Manila Galleon Trade allowed modern, liberal ideas to enter the Philippines, eventually and gradually inspiring the movement for independence from Spain. On September 14, 1815, the Galleon Trade with Mexico’s war of independence. OPENING OF THE SUEZ CANAL An artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, the Suez Canal connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez. Constructed by the Suez Canal Company between 1859-1869 under the leadership of French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps, it was officially opened on November 17, 1869. (Manila to Spain lasted for 90 days before Suez Canal was built) With the opening of the canal, the distance of travel between Europe and the Philippines was considerably abbreviated and thus virtually brought the country closer to Spain. Before the opening of the canal, a steamer from Barcelona had to sail around the Cape if Good hope to reach Manila after a menacing journey of more than three months. With the Suez Canal, the voyage was lessened to only 32 to 40 days. The opening of the Suez Canal became a huge advantage in commercial enterprises especially between Europe and East Asia. More importantly it served as a significant factor that enabled the growth of nationalistic desires of Jose Rizal and other Filipino Illustrados. The Suez Canal expedited the importation not only of commercial products but also of books, magazines and newspapers with liberal ideas from America and Europe, which ultimately affected the minds of Rizal and other Filipino reformists. The availability of Suez Canal has also encouraged the Illustrados especially Jose Rizal to pursue education abroad and learn scientific and liberal education in European academic institutions. Their social dealings with liberalism in the west have influenced their thoughts on nationhood, politics and government. TRIVIA 6 Republic Act No. 137- Province of Rizal Republic Act No. 243- An Act granting the right to use public land upon the Luneta in the city of Manila upon which to erect a statue of Jose Rizal, Republic Act No. 345- Anniversary of Rizal’s Death MONOPOLIES Another main source of wealth during the post galleon era was monopoly contracting. After 1850, government monopoly contracts for the collection of different revenues were opened to foreigners for the first time. The opium monopoly was specifically a profitable one. During the 1840’s, Spanish government had legalized the use of opium and a government monopoly of opium importation and sales was created. There were monopolies of special crops and items such as spirituous liquors (1712-1864), betel nut (1764), tobacco (1782-1882), and explosives (1805-1864). Among these monopoly systems, the most controversial and oppressive to locals was the tobacco monopoly. On March 1, 1782, Governor General Jose Basco placed the Philippine Tobacco industry under government control, thereby establishing the tobacco monopoly. It aimed to increase government revenue since then annual subsidy coming for the widespread cultivation of tobacco in the provinces of Cagayan Valley, Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, la union, Isabela, Abra, Nueva Ecija, and Marinduque. These provinces planted nothing but tobacco and sold their produce only to the government at a pre-designated price, leaving little or no profit for the local farmers. The system set that required number of tobacco plants t must be sold to them by each family. Nobody was allowed to keep even a few tobacco leaves for personal use, thereby forcing the local farmers to buy the tobacco they themselves from the government. The colonial government exported the tobacco to other countries and to the cigarette factories in Manila. The tobacco monopoly positively raised revenues for the government and made Philippine tobacco prominent all over Asia and some parts in Europe. The tobacco monopoly was finally abolished in 1882 (some references state that the tobacco monopoly in the Philippines was from 1781 to 1881 not 1782 to 1882 although most authors agree that it lasted for exactly 100 years. A century of hardship and social injustice caused by the tobacco monopoly prompted Filipinos. 7 THE SOCIAL BACKGROUND EDUCATION IN THE 19TH CENTURY With the coming of Spanish colonizers, the European system of education was somewhat introduced to the archipelago. Schools were established and run by Catholic missionaries. The colonial government and the catholic church made religion a compulsory subject at all levels. King Philip II’s Leynes de Indies (Laws of Indies) mandated Spanish authorities in the Philippines to educate the locals. To teach them how to read and write and to learn Spanish. The Spanish missionaries thus established schools, somewhat educated the natives, but did not seriously teach them the Spanish language, fearing that the Indios would become so knowledgeable and turn out to be their co-equal. Less than one-fifth of those who went to school could read and write Spanish, and far fewer could speak the language properly. The first formal schools in the land were the parochial schools opened in their parishes by the missionaries, such as the Augustinians, Franciscans, Jesuits, and Dominicans. Aside from Religion, the native children were taught reading, writing, arithmetic and some vocational and practical arts subjects. Aside from the Christian Doctrines, Latin (the official language of the Catholic Church) was also taught to the students instead of Spanish. The Spanish friars believed that the natives would not be able to match their skills, and so one way for the locals to learn fast was to use strict discipline, such as applying corporal punishment. Later on, colleges (which were the equivalent of our high schools today) were established for boys and girls, there was no co-education during the Spanish regime as boys and girls studied in separate schools. The subject taught to college students included history, Latin, geography, mathematics, and Philosophy. University Education was opened in the country during the early part of the century. Initially, the colleges and universities were open only to the Spaniards and those with Spanish Blood (mestizos). It was only in the 19th century that these universities started accepting native Filipinos. Still giving emphasis on religion, universities then did not necessarily teach science and mathematics. 17th In 1863, a royal decree called for the establishment of a public-school system in the Philippines. Formerly run totally by the religious authorities, the education in the colony was thus finally administered by the government during the last half of the 19th century though even the church controlled its curriculum. Previously exclusive for Spaniards and Spanish Mestizos, universities became open to natives though they limited their accommodations to the sons of wealthy Indio Families. 8 Nonetheless, as a result of the growing number of educated natives, a new social class in the country emerged, which came to be known as the Illustrados. But despite their wealth and education, the Illustrados were still deemed by the Spaniards as inferior. One of the aims of the Illustrados was to be in the same level with the proud Spaniards. With the opening of Suez Canal, which made travel to Europe faster easier, and more affordable, many locals took advantage higher and better education in Europe, typically in Madrid and Barcelona. There, nationalism and the thirst for reform bloomed in the liberal atmosphere. The new enlightened class in the Philippine independence movement, using the Spanish language as their key means of communication. Out of this talented group of students from the Philippines arose what came to be known as the Propaganda movement. The most prominent of the Illustrados was Jose Rizal, who inspired the craving for freedom and independence with his novels written in Spanish. TRIVIA Peninsulares- Spaniards born in Spanish Insulares- Spaniards born in Philippines Mestizo- (middle class) Chinese - Indios Chinese - Spaniards Spanish - Indios Indios- Pure Filipinos POLITICAL LANDSCAPE LIBERALISM Liberalism is a worldview founded on ideas of freedom and equality. The French Revolution (1789-1799) started a political revolution in Europe having Liberty, Equality and Fraternity as its battle cry. This revolution became a fundamental change in political history of France as French governmental structure was changed from absolute monarchy into a more liberal government system founded on the principles of citizenship and inalienable rights. As an 9 eventual repercussion of the French Revolution, Spain later experienced a stormy century of political disturbances which included numerous changes in parliaments and constitutions, the Peninsular War, the loss of Spanish America and the Struggle between liberals and conservatives. They thus pursued curbing its influence in political life and education. In the 19th century, the movement against catholic church, called anti-clericalism, has gained some strength. When the Philippines was opened to world trade in 19th century, liberal ideas from America carried by ships and people from foreign parts started to penetrate the country and sway the Illustrados. The Philippines actual experience of liberalism came from the role modelling of the first liberal governor-general in the Philippines, Governor-General Carlos Maria De la Torre. The liberal General was appointed by the provisional government as Governor General of the Philippines. He held the position from 1869-1871 and is widely considered to be the most beloved of the Spanish Governors General ever assigned in the Philippines. His liberal and democratic governance had provided Jose Rizal and the others a review of a democratic rule and way of life. He avoided luxury and living a simple life. He encouraged freedom and abolished censorship. He recognized the freedom of speech and of the press. Because of his tolerant policy, Father Jose Burgos and other Filipino priests were encouraged to pursue their dream of replacing the friars with the Filipino clergy as parish priest. His greatest achievement was the peaceful solution to the land problem in Cavite. IMPACT OF BOURBON REFORMS During the Napoleonic occupation of Spain, a liberal constitution was promulgated in Cadiz in March 1812. Drafted by elected representatives, the Cadiz Constitution was put in practice in almost of the areas of Hispanic Monarchy still under control of the Spanish crown. This milestone constitution had an impact on many other European constitutions as well as on the American states after independence. The Cadiz Constitution was the first constitution in Europe to deal with national sovereignty, sovereignty as coming from the people and not from the king. Unlike the French constitution, which applied to all Frenchspeaking citizens of France, this Spanish Constitution of 1812 had a universal character as it included everyone from overseas, like the Italian kingdoms as well as the Philippines. The first delegates from the Philippines were Pedro Perez de Tagle and Jose Manuel Coretto who took their oath of office in Madrid. The Cadiz constitution, which was formally implemented in Manila soon after, established the principles of universal male suffrage, national sovereignty constitutional monarchy, and 10 freedom of the press, and advocated the and reform and free enterprise. From the freedom-loving people of the Philippines in the 19 th century, the constitution was very influential as it was a liberal constitution, which vested sovereignty in the people, recognized the equality of all men and the individual liberty of the citizen, and granted the right of suffrage. 11 TINIENTE KIKO OF CALAMBA (FRANCISCO MERCADO RIZAL) WITH MORE THAN 600 resorts in the place today, its tourism’s promoters claim that it has earned the nickname “Resort Capital of the Philippines”. In 1848, Jose Rizal’s parents decided to build a home in this town in Laguna, southern Luzon called Calamba. Its name was derived from "kalan-banga", which means "clay stove" (kalan) and "water jar" (banga). Rizal’s adoration of its scenic beauty—punctuated by the sights of the Laguna de Bay, Mount Makiling, palm-covered mountains, curvy hills, and green fields—was recorded in the poem he wrote in Ateneo de Manila in 1876, ‘Un Recuerdo A Mi Pueblo’ (In Memory of my Town). But if Rizal ‘s poem was written today, he might have mentioned the threefloor SM mall, shopping centers, and the South Luzon Expressway (SLEX) terminus in the place. A city since 2001, Calamba’s most recent claim to international fame is perhaps it’s being the origin of Herbert Chavez, the ‘Superman’ look-alike via plastic surgery recognized by the Guinness World Records as having the largest collection of superman memorabilia. DON FRANCISCO MERCADO More than one and a half century ago, a far greater ‘superman’, Jose Rizal, was born in the place. His father, Francisco Engracio Rizal Mercado, was an independent-minded, taciturn but dynamic gentleman from whom Jose inherited his ‘free soul’. Don Francisco became ‘tiniente gobernadorcillo’ (lieutenant governor) in Calamba and was thus nicknamed ‘Tiniente Kiko’. Students’ comical conjecture that the fictional character ‘Kikong Matsing’ of ‘Batibot’ was named after Don Francisco is, of course, unfounded. Francisco’s great grandfather is Domingo Lam-co, a learned pro-poor or ‘maka-masa’ Chinese immigrant businessman who married a sophisticated Chinese mestiza of Manila named Ines de la Rosa. One of their two children, Francisco (also), resided in Biñan and married Bernarda Monicha. Francisco and Bernarda’s son, Juan Mercado, became a ‘gobernadorcillo’ (town mayor) of Biñan, Laguna. He married Cirila Alejandra and they had 12 children, the youngest being Jose Rizal’s father, Francisco. Jose’s father was born on May 11, 1818 in Biñan, Laguna. When he was eight years old, he lost his father. He was nonetheless educated as he took Latin and Philosophy at the College of San Jose in Manila, where he met and fell in love with Teodora Alonso, a student in the College of Santa Rosa. Married on June 28, 12 1848, they settled down in Calamba where they were granted lease of a rice farm in the Dominican-owned haciendas. DON FRANCISCO’S INFLUENCE TO RIZAL When Jose was seven years old, his father provided him the exciting experience of riding a ‘casco’ (a flat-bottomed boat with a roof) on their way to a pilgrimage in Antipolo, and to visit afterward Saturnina at the La Concordia College in Manila. As a gift, the child Jose also received a pony named ‘Alipato’ from his father (Bantug and Ventura). One of Jose’s childhood tutors, Don Leon Monroy, was Don Francisco’s friend whom the father personally chose to teach his son the basics of Spanish and Latin. When Monroy died after five months of tutoring Rizal, Don Francisco sent his son to a school in Biñan. After sometime, Jose told his father that he had already learned all there was to be taught at Biñan. Teniente Kiko firmly scolded Jose and hustled him back to the school. Maestro Justiano Aquino Cruz, Jose’s teacher in Biñan, later confirmed nonetheless that Jose had indeed finished already all the needed curricular works. Against his wife’s reluctance, Don Francisco then sent Jose to enroll at the Ateneo Municipal in Intramuros, Manila. When Jose was in his third year in Ateneo, he became indulge in reading novels. Because Jose requested for it, his loving father bought him an expensive set of the Universal History by Cesar Cantu. While boarding in a small house on Calle Caraballo, Jose was once persuaded by his landlady Tandang (Old) Titay to play the card game ‘panguingue’ for her. But Don Francisco suddenly arrived from Calamba and caught Jose at the ‘panguingue’ table. The father scolded the young Rizal and the respectful son wholeheartedly accepted his father’s reprimand (Bantug and Ventura). After the Cavite mutiny and the martyrdom of the Gomburza in 1872, Jose, for the first time, heard of the word ‘filibustero’ (subversive). But Don Francisco then forbade the members of his family to utter the word. And when Rizal, upon his return to the country from Europe in 1887, wanted to visit his girlfriend Leonor Rivera in Pangasinan, his father strongly opposed the idea. Don Francisco believed that the visit would put Leonor’s family in danger since at the time Jose 13 had already earned the label ‘filibustero’ for writing the controversial Noli Me Tangere. Later in his life, Jose would use the derivative of the term (Filibusterismo) to name his more ‘subversive’ second novel. In 1891, Don Francisco, along with Paciano and son-in-law Silvestre Ubaldo, had escaped from the clutch of their Spanish persecutors and opted to join Jose in Hong Kong. The Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) were not that many in Hong Kong yet, but it is said that the 73-year old Don Francisco loved the climate in the place where he stayed with his beloved son. RIZAL’S LOVE FOR HIS FATHER Rizal’s affection for his father may have not been given much emphasis by many biographies. But Jose, no doubt, adored Don Francisco. In 1881, Jose made a clay bust of his father. About six years later, he carved a life-size wood sculpture of Don Francisco. Perhaps, Jose even spent a lot of time finishing the life-size sculpture—because Don Kiko, unlike the national hero, was above average in height. In honor of his father, Jose named his premature son (by Josephine Bracken) ‘Francisco’. The infant ‘Francisco’ unfortunately died three hours after birth. Before his death on December 30, 1896, Jose wrote this to his brother, Paciano: “Tell our father I remember him, and how! I remember my whole childhood, of his affection and his love. Ask him to forgive me for the pain that I have unwillingly caused him.” To his father, Jose directly wrote: My beloved Father, Pardon me for the pain with which I repay you for sorrows and sacrifices for my education. I did not want nor did I prefer it. Goodbye, Father, goodbye …. Don Francisco died in Manila on January 5, 1898 at the age of 80, approximately a year after his son’s martyrdom in Bagumbayan. Jose Rizal considered Teniente Kiko as ‘model of fathers. Whenever we study the life of Don Francisco, we remember our respective father whom we likewise subjectively call ‘the best Dad in the world’. 14 LOLA LOLAY OF BAHAY NA BATO (TEODORA ALONZO) IF INTERNET’S SOCIAL MEDIA were already existing during the PhilippineAmerican War, and somebody had posted the famous picture of the aged Doña Teodora Alonso next to the excavated skull of the national hero, there might have been an online pandemonium which could have surpassed the Gangnam Style’s record. Some consider the picture morbid, but others regard it as an indubitable manifestation of the mother’s intense love for her son. THE RIZAL HOME Doña Teodora Alonzo y Quintos is the homemaker of the first massive stone house, or ‘bahay na bato’, in Calamba, which is the very birthplace of the national hero. It was a rectangular two-storey building, built of adobe stones and solid woods, with sliding capiz windows. Its ground floor was made of lime and stone, the second floor of hard woods, except for the roof, which was of red tiles. There was an azotea and a water reservoir at the back. The courtyard contained tropical fruit trees, poultry yard, a carriage house, and a stable for the ponies. Its architectural style and proximity to the church implied the owners’ wealth and political influence. Rizal’s ancestral house was destroyed during World War II. Juan Nakpil supervised its reconstruction and restoration as ordered by President Quirino. With funds mainly contributed by Filipino school children, this Jose Rizal Shrine was inaugurated in 1950. It is said that the only surviving feature of Rizal’s original house is the deep well that has become a ‘wishing well’ for many tourists. Even the house’s familiar white color was not preserved for it was repainted a pale shade of green. Nonetheless, many Rizal ‘relics’, including the supposed black coat worn by Rizal during his execution, can be found in the shrine. 15 TEODORA ALONSO Unknown to many, Doña Teodora— together with her husband—is buried near the narra tree about 20 meters away from the shrine’s ‘wishing well.’ For long, this historic Calamba house was tended and managed by Jose’s mother also known as ‘Lolay’. Common biographies state that Doña Teodora was born on November 8, 1826 in Santa Cruz, Manila and baptized in Santa Cruz Church. Strangely however, the volume in the church books that supposedly contains Teodora’s baptismal records is the only one missing in the otherwise complete records down to the eighteenth century (Ocampo, p. 39). Asuncion Rizal-Lopez Bantug, the granddaughter of Jose’s sister Narcisa, distinctively claims that Lola Lolay and her all siblings were born in Calamba, but (just) lived in Manila (Bantug, p. 18). Doña Lolay was educated at the College of Santa Rosa, an esteemed school for girls in Manila. She was usually described as a diligent business-minded woman, very graceful but courageous, well-mannered, religious, and well-read. Very dignified, she disliked gossip and vulgar conversation. Possessing refined culture and literary talents, she influenced her children to love the arts, literature, and music. Herself an educated woman, Lolay sent her children to colleges in Manila. To help in the economy of the family, she ran sugar and flourmills and a small store in their home, selling home-made ham, sausages, jams, jellies, and others. Looking back, her business in a way predated the meat processing commerce of the Pampangueños today and the ube jam production of some nuns in Baguio. 16 DOÑA TEODORA ‘S ANCESTRY It is believed that Doña Teodora’s family descended from Lakandula, the last native king of Tondo. (For young generations, Lakandula has to be distinguished from the unofficial ‘Hari ng Tondo’, Asiong Salonga, the Manila kingpin who was immortalized in the movie incidentally by Laguna’s own governor E. R. Ejercito.) Lolay’s great-grandfather was Eugenio Ursua (of Japanese descent) who married a Filipina named Benigna. Regina, their daughter, married a FilipinoChinese lawyer of Pangasinan, Manuel de Quintos. Lorenzo Alberto Alonso, a well-off Spanish-Filipino mestizo of Biñan, took as his ‘significant other’ Brigida Quintos, daughter of Manuel and Regina Quintos. The Lorenzo-Brigida union produced five children, the second of them was Jose Rizal’s mother, Teodora Alonso Quintos. Through the Claveria degree of 1849 which changed the Filipino native surnames, the Alonsos adopted the surname Realonda. Rizal’s mother thus became Teodora Alonso Quintos y Realonda. LOLAY AND THE YOUNG RIZAL Doña Teodora played an important role in the life of the national hero. She was said to have suffered the greatest pain during the delivery of her seventh child, the younger of her two sons, Jose. Her daughter Narcisa recalled: “I was nine years of age when my mother gave birth to Jose. I recall it vividly because my mother suffered great pain. She labored for a long time. Her pain was later attributed to the fact that Jose’s head was bigger than normal” (Bantug and Ventura). But this would not be the only pain that she would suffer on account of this son. Lolay was the first teacher of the hero—teaching him Spanish, correcting his composed poems, and coaching him in rhetoric. On her lap, Jose learned the alphabet and Catholic prayers at the age of three, and had learned to read and write at age 5. At an early age, Rizal thus learned to read the Spanish family Bible, which he would refer to later in his writings. Rizal himself remarked that perhaps the education he received since his earliest infancy was what has shaped his habits. The mother also induced Jose to love the arts, literature, and the classics. Before he was eight years old, he had written a drama which was performed at a local festival and for which the municipal captain rewarded him with two pesos. 17 THE STORY OF THE MOTH To impart essential lessons in life, Lolay held regular storytelling sessions with the young Rizal. Doña Teodora loved to read to Pepe stories from the book ‘Amigo de los Niños’ (The Children’s Friend). One day, she scolded his son for making drawings on the pages of the story book. To teach the value of obedience to one’s parents, she afterward read him a story in it. Lolay chose the story about a daughter moth who was warned by her mother against going too near a lamp flame. Though the young moth promised to comply, she later succumbed to the pull of the light’s mysterious charm, believing that nothing bad would happen if she would approach it with caution. The moth then flew close to the flame. Feeling comforting warmth at first, she drew closer and closer, bit by bit, until she flew too close enough to the flame and perished. Incidentally, Pepe was watching a similar incident while he was listening to the storytelling. Like a live enactment, a moth was fluttering too near to the flame of the oil lamp on their table. Not merely acting out, it did fall dead as a consequence. Both moths in the two tales paid the price of getting near to the fatal light. Many years later, Rizal himself felt that the moths’ tale could serve as an allegory of his own destiny. About himself, he wrote: “Years have passed since then. The child has become a man… Steamships have taken him across seas and oceans … He has received from experience bitter lessons, much more bitter than the sweet lessons that his mother gave him. Nevertheless, he has preserved the heart of a child. He still thinks that light is the most beautiful thing in creation, and that it is worthwhile for a man to sacrifice his life for it.” AGAINST RIZAL’S FURTHER EDUCATION Doña Teodora was remarkably against the idea of sending Jose to Manila to study, arguing that he already knew enough and that “if he learns more, he will only end up on the scaffold” (Bantug, p. 37). This stand she reiterated when Rizal had to go to the University of Santo Tomas for higher studies. Aware that Spanish officials frowned at learned Filipino, she told her husband: “Don’t send him to Manila again; he knows enough. If he gets to know more, the Spaniards will cut off his head” (as quoted in Zaide, p. 46). Doña Teodora never ceased to worry about his bright son. In 1884, after Rizal gave a toasting speech in Spain at the banquet for the winning Filipino painters (Juan Luna and Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo), his assail to the unworthy Spaniards in the Philippines received a great deal of reactions. The general sentiment was that it would not be good for him to return to the Philippines. This caused Doña Teodora much worries that she turned ill. Upon recovering, she 18 begged his son through a letter not to meddle in things that bring her sorrow, and to comply instead with the duties of a good Christian. RIZAL’S TIO JOSE ALBERTO Among Teodora’s siblings—Narcisa, Teodora, Gregorio, Manuel, and Jose—it was the youngest, Jose Alberto, who became the most historically significant to the Rizal family. Jose Alberto, the illustrious engineer of Biñan, studied in a British school in Calcutta, India. It is said that he exerted a good influence on the young Rizal, particularly inspiring him to cultivate his artistic talents. Jose Alberto is diversely referred to as brother, cousin, half-brother, or stepbrother of Teodora Alonso, depending on the biographer you are reading. This is now clarified by the unearthed information that even before Lorenzo Alberto Alonso (Teodora and Jose Alberto’s father) took Brigida as his better half, he “had married a 12-year old Ilocana named Paula Florentino in 1814” (Ocampo, 2013, p. 38). Those who declare that Jose Alberto is Teodora’s half-brother thus seem to imply that Jose Alberto was from the Florentino lineage and therefore the only legal son of Lorenzo Alberto. However, a document written by Rizal himself, now being kept at the Rizal Library in Ateneo de Manila University, plainly reveals that Jose Alberto and Teodora Alonzo are of the same parents. Moreover, Lorenzo Alberto Alonso’s marriage to the 12-year old girl from Vigan—which was by a fixed marriage—did not produce any child. Dr. Bimbo Sta. Maria, an officer of Biñan-based organization, United Artists for Cultural Conservation and Development (UACCD) believes that the halfbrother issue was part of the family’s plan to keep its ties with the Spanish government (“Mga Lihim ng Pamilya ni Rizal”). Researching about Rizal’s family for many years, Sta. Maria had known that Lorenzo Alberto was conferred the title “Knight of the Order of Queen Isabella the Catholic” for supporting the Dominicans in their missions in Indo-China. The title was transferable to one of his legal children after his death. However, all his children by Brigida Quintos (including Teodora Alonzo and Jose Alberto) were all illegitimate in papers. To receive the influential title, Jose Alberto, with the approval of his siblings, thus declared himself the legitimate son of Lorenzo Alberto and Paula Florentino, in effect disowning his real mother. If Sta. Maria’s theory is correct, then the controversial 200-year old mansion in Biñan should at least be considered by the government as a historical landmark for being the ancestral house of Teodora Alonso’s family. As 19 of this writing, the mansion is being demolished for plans of making the place commercial. DOÑA TEODORA’S IMPRISONMENTS When Rizal was just about to go to Manila to continue his education at the Ateneo, an ordeal occurred to his family—his mother was thrown into prison. Jose Alberto, Lolay’s ‘favorite’ brother, had returned from Europe and found that her wife, Teodora Formoso, left their home and children for another man. He planned to divorce her, but Doña Teodora persuaded the couple to reconcile so as to avoid family scandal. Alberto’s wife however sued her husband for allegedly trying to poison her and incriminated Dona Teodora as his coconspirator. Alberto’s wife was aided by the Spanish lieutenant of the Guardia Civil. Remarkably, the Calamba’s gobernadorcillo, Antonio Vivencio del Rosario, was hasty to believe the charge. The two officials were frequent guests at the Rizal home but both had been nursing grudges against the Rizals. At one occasion, Rizal’s father could not accommodate to give fodder for the lieutenant’s horse. The gobernadorcillo, on the other hand, is said to have felt insulted that he had not been shown any greater respect than the Filipino guests in his visits to Rizal home. Barbara Cruz-Gonzalez, great granddaughter of Rizal’s sister, Maria, shared one detailed version of the ‘poisoning’ accusation based on the tales that circulate in the involved clans (“Mga Lihim ng Pamilya Ni Rizal”). She narrated that Jose Alberto, upon discovering his wife’s infidelity, locked Teodora Formoso in a room in the historically controversial mansion in Biñan, and asked her sister Teodora to watch over his wife. One day, Teodora Alonso brought some food to Formoso which the latter refused to eat. Formoso instead fed it to her dog. Allegedly, the dog eventually died after eating the food. Hence, with the help of a leader of the Guardia Civil, who was purportedly Formoso’s lover, Jose Alberto’s wife had sent Teodora Alonso to prison. Rizal’s mother was imprisoned in Santa Cruz, the capital of Laguna. It is said that the Rizals appealed to the Supreme Court, which ordered her immediate discharge. But she was rearrested by the order of the insulted judge, stating that Rizals’ appeal to the Supreme Court was contempt of his court. The Supreme Court irrationally upheld this contention. Some other fabricated charges were filed against her, hence she languished behind bars for about two and a half years in the 1870s. Teodora Alonso was imprisoned for the second time in the 1880s on the nonsense charge that she did not call herself a ‘Realonda de Rizal’ but simply ‘Teodora 20 Alonso’. Concerning this, Rizal bitterly recorded: “From Manila they sent her to Sta. Cruz, Laguna Province, through mountains from town to town … Imagine an old woman of 64 traveling through mountains and highways with her daughter under the custody of the civil guard. When my mother and sister, after four days of traveling, arrived at Sta. Cruz, the governor, deeply touched, released them.” (Epistolario Rizalino, Vol. V, Part II, p. 621.) TEODORA’S LONG WALKS In both imprisonments, Rizal’s mother was forced to walk rough roads before being locked up in the prison cell in Santa Cruz, Laguna. When she was incarcerated for the first time, some histories claim that she did a gruesome 50kilometer walk, while others state ‘16 kilometers. So why is there a discrepancy? Which figure is plausible? Online distance calculators today indicate that Calamba is 43-kilometer away from Santa Cruz, suggesting that the ‘50 kilometers’ claim is more plausible. But that is if the walk was really from Calamba to Santa Cruz. Because a relative of Teodora Alonso, Jacoba Faustina-Cruz, narrated that the forced walk was only from Biñan to Calamba (as quoted by Ocampo, 2010, Philippine Daily Inquirer). Thus, if Cruz’s statement is true, then the ’16 kilometers’ claim is more reasonable. Biñan and Calamba are 15.2465035627 kilometers away from each other, according to a modern mobile phone’s application. Concerning the second time Teodora was imprisoned, Rizal’s descendants claim that the then half-blind Teodora Alonso was ordered to walk ‘85 kilometers’ from Manila to Santa Cruz (Bantug, p. 100). Modern distance calculators suggest that 91.5 kilometers is the distance between the two locations, though it’s only 58.9813974616 kilometers if one could just fly like a bird in a straight line. The Zaides’ however claimed that the walk was only from Calamba to Santa Cruz (Zaide & Zaide p. 205)—which if true, then the walk was just about a half shorter. Either way, the miserable experience of Doña Teodora had predated the sufferings of the victims in the infamous WW II Death March (about 151 kms.). JOSE’S LOVE FOR HIS MOTHER One known thing about Rizal is that he loved his mother very much. At the end of his first year at the Ateneo, Rizal visited her mother in Santa Cruz prison without telling his father. Doña Teodora joyfully embraced her son who told her of his outstanding school grades. The next summer vacation, Rizal did not forget to see again and brighten up her mother with news of his academic successes. On her part, Doña Teodora had mentioned of her dream the previous night. Rizal interpreted the dream as portending that she would be released from prison in three months’ time. Rizal’s 21 ‘prophecy’ proved true as Teodora was set free barely three months after her son’s visit. The most known poem written by Rizal in Ateneo, ‘Mi Primera Inspiracion’ (My First Inspiration) was dedicated to his mother on her birthday. It is believed to have been written in the year 1874, upon the release from prison of his mother. Upon learning that Doña Teodora was going blind, Rizal decided to take medicine at the University of Santo Tomas. He nonetheless transferred to the Universidad Central de Madrid where he obtained the degree of Licentiate in Medicine. And because he really wanted to cure his mother's advancing blindness, Rizal went to the University of Paris and then the University of Heidelberg to complete further study in ophthalmology. After earning the fury of the Spaniards in the Philippines for writing the Noli, Rizal decided to return to Calamba in 1887 despite his loved ones’ strong warnings. His major reason for standing by his decision is to perform an operation on Doña Teodora’s eyes. MOTHER AND SON IN DAPITAN Newly released from prison in 1891, Doña Teodora joined Rizal in Hong Kong where the Rizal family had a happy Yuletide celebration together. And when Rizal was exiled in Dapitan, Doña Teodora did not hesitate to leave the peaceful life in Hong Kong in August 1893 just to keep house for her son. The son operated on his mother’s cataract in Dapitan. The whole ophthalmic treatment was successful despite her being a difficult patient, removing at least once the bandages from her eyes against her son’s prescription. In 1895, Doña Teodora left Dapitan for Manila to be with Don Francisco who was getting weaker. Attesting to his mother’s being a loving wife, Rizal wrote in his letter to Blumentritt: “My father is well again and my old mother does not want to separate from him – like two friends in the last hours of farewell, knowing that they are going to separate, they do not like to be far from each other.” In October 1895, Rizal sent her mother his now widely acclaimed poem ‘Mi Retiro’ which he wrote upon her request. After Doña Lolay left Dapitan, Josephine Bracken came to Rizal’s life. The son wrote her mother about Josephine. Aware that the priests refused to marry 22 the couple, Doña Teodora told her excommunicated son that loving each other in God’s grace was better than being married in mortal sin (Bantug, p. 120). In 1896, when the revolution broke out while Rizal was on his way to Cuba, he wrote to his mother these meaningful sentences: “Don’t worry about anything; we are all in the hands of the Divine Providence. Not all who go to Cuba die, and when finally, one has to die, at least one may die doing some good” (as quoted in Bantug, p. 136). DOÑA TEODORA’S SHARE OF MARTYRDOM When Rizal was sentenced to death after a mock trial, the aged Doña Teodora fervently plead to the governor general for her son’s life, but to no avail. In Rizal’s last hours, his sorrowful mother came to see her sentenced son. Teodora Alonso was not permitted a last embrace by the guard though her beloved son, in quiet grief, managed to press a kiss on her hand. Captain Rafael Dominguez, the special Judge Advocate appointed to institute the court’s action against Rizal, was said to have been moved with compassion at the sight of Rizal’s kneeling before his mother and asking pardon. What greater grief could dwell in a mother’s heart than to see the day come when her dearly loved son would be executed just for wishing the best for his family and country. On December 30, 1896, Doña Teodora indeed tragically lost her much-loved son. More than ten years after, the Philippine government offered her a lifetime pension as a sign of gratefulness. With sincere dignity, she refused the offer, courteously explaining that her family had never been patriotic for money. She suggested that if the government had plenty of funds, it better reduces the citizens’ taxes. At the age of 80, our Lola Lolay died in Manila on August 16, 1911. Appropriate honors were accorded to her funeral. Her memories teach us to love our respective mothers and grandmas while they are still alive. 23 PACIANO RIZAL: PINOY HERO’S BIG BROTHER ON HIS ADVICE, the national hero dropped the last three names in his full name and thus enrolled at the Ateneo as ‘Jose Protasio Rizal.’ Paciano, the second of eleven children of Don Francisco and Doña Teodora, is the only brother of Dr. Jose Rizal. When he was a student at the College of San Jose, Paciano had used “Mercado” as his last name. But because he had gained notoriety with his links to Father Burgos of the ‘Gomburza,’ he suggested that Jose use the surname ‘Rizal’ for his own safety. THE SURNAME RIZAL Had their forefathers not adopted other names, then Jose and Paciano could have been known as ‘Lamco’ brothers. Their paternal great-great grandfather, Chinese merchant Domingo Lamco, adopted the name ‘Mercado’ which means ‘market’. But Jose’s father, Francisco, who eventually became primarily a farmer, adopted the surname ‘Rizal’ (originally ‘Ricial’, which means ‘the green of young growth’ or ‘green fields’). The name was suggested by a provincial governor who is a friend of the family. The new name, however, caused confusion in the commercial affairs of the family. Don Francisco thus settled on the name ‘Rizal Mercado’ as a compromise, and often just used his more known surname ‘Mercado’. Commenting on using the name ‘Rizal’ in Ateneo, Jose once wrote: “My family never paid much attention [to our second surname Rizal], but now I had to use it, thus giving me the appearance of an illegitimate child!” But this very name suggested by Paciano to be used by his brother had become so well known by 1891, the year Jose finished his El Filibusterismo. As Jose wrote to a friend, “All my family now carry the name Rizal instead of Mercado because the name Rizal means persecution! Good! I too want to join them and be worthy of this family name...” PACIANO’S PROFILE Paciano Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda was born on March 7, 1851 in Calamba, Laguna. According to Filipino historian Ambeth R. Ocampo, Paciano was fondly addressed by his siblings as ‘ñor Paciano,’ short for ‘Señor Paciano’. The 10-year older brother of Jose studied at San Jose College in Manila, became a farmer, and later a general of the Philippine Revolution. Had Paciano owned a Facebook account and you were his friend; you would not be entertained that much by looking at his photo albums. Paciano had only two known pictures—one is a ‘stolen shot’ by a nephew during a family reunion, and the other, taken posthumously, of his corpse. A descendant explained that Paciano—unlike his brother who even frequented photo studios 24 for his pictures—did not want to be photographed. The reason was that “he was a wanted man in the past and if there were no photographs of him, then it would be hard for the authorities to arrest him. He could walk everywhere without being recognized” (Ocampo, p. 43). According to his grandchildren, Paciano had a very fair complexion and rosy cheeks. His descendants were quick to add that their lolo was more handsome than the national hero, and much taller, about 5’7” to 5’9. “When he died and the body was brought to the funeraria, his feet stuck out of the coffin, which was too small for him” (as quoted in Ambeth Ocampo, p. 43). This description though was neither relative nor one-sided, for it was confirmed by Jose Rizal himself. In a letter to Blumentritt, he wrote: “[Paciano] is more refined and serious than I, taller, slenderer, and fairer in complexion than I with a nose that is fine, beautiful and sharp pointed, but he is bow-legged” (as quoted in Ambeth Ocampo, p. 43). PACIANO, BURGOS, AND THE GOMBURZA When Jose was about to study in Manila, Paciano was studying at the College of San Jose, living and working with his teacher Dr. Jose Burgos, a dignified and courageous Filipino priest. Jose Burgos, just like some other Filipino priests that time such as Mariano Gomez and Jacinto Zamora, was seeking reform within the Catholic Church. Promoting equal rights for Filipino and Spanish priests in the country and advocating the secularization of local churches, they openly denounced the practice of throwing Filipino priests out of their churches to make place for Spanish friars. The Spanish priests took advantage of the mutiny by workers of the Cavite Arsenal in 1872 to get rid of Gomez, Burgos, and Zamora. They were falsely blamed for having stirred up the mutiny, court-martialed, and convicted. Later known in history as the Gomburza, an acronym denoting their surnames, all three were executed on February 17, 1872 at Bagumbayan by having the garrote screwed into the backs of their necks until the vertebrae cracked. On his part, Paciano was prevented from taking his final examinations because of his known connection with Burgos and for denouncing the injustice and abuses against Filipinos. PACIANO AND THE SPANISH AUTHORITIES Paciano Rizal grew up being exposed to the exploitation of the Spanish clergy and colonial government. Because of his relationship with Burgos, Spanish authorities had put him in the ‘watch list’ long before Jose was spied on by officials. And even before Jose experienced to be exiled, Paciano had already 25 gone through deportation to Mindoro in 1890 to 1891 for fighting for the rights of Calamba farmers. Paciano deliberately exhibited a firm character in the face of the abusive Spanish colonizers. It is said that he once went to the Dominican estate house in Canlubang and was made to wait for a long time before the friars at last attended to him. Some months later, he let those friars experience the same thing when they went to his place to buy a reputedly good horse. In November 1896, Paciano was arrested while Jose was in Fort Santiago prison. To extract evidence for Jose’s involvement in the revolution, Paciano was subjected to tortures for two agonizing days. Two officers took turns in thrashing him and crushing his fingers using thumbscrew. Hanged by the elbows and raised several feet, he was dropped repetitively until he lost consciousness. But never did he sign any document that could incriminate his brother to any charge. Paralyzed for days, it is said that Paciano never completely recuperated from that torment. THE CALAMBA AGRARIAN TROUBLE Paciano’s deportation to Mindoro had something to do with the Calamba agrarian trouble, also known as ‘Calamba hacienda question’. Being the elder son, he was given responsibilities not only in watching his younger siblings but also in the Mercado-Rizal farm. This thus put him in the forefront when an agrarian upheaval arose. In December 1887, Governor General Emilio Terrero, induced by the contents of the Noli Me Tangere, ordered a government investigation of the way friar estates were run. In Calamba, the folks chose to beseech Jose Rizal’s assistance in collecting information and listing their comments as regards Dominican hacienda management. It was thus exposed and recorded that the Dominican Order continually and arbitrarily increased the land rent or canon. It had been charging the tenants ridiculous fees for irrigation services and other agricultural improvements which were actually nonexistent. Excessive rates of interest were also charged for late payment of rent. And when the rent could not be paid, the tenants’ houses and belongings were confiscated. Since no receipts were issued for payments, some tenants were accused of not paying and thus dispossessed of their fields. These findings, which the townsfolk, friar representatives, and government officials signed on January 8, 1888, were sent to the civil government. But the authorities had their necks held by the friars. Unsurprisingly, Rizal’s report did not 26 resolve the agrarian trouble. Instead, the land occupied by the Rizal family and that toiled by Paciano and Don Francisco became the target of Dominican retaliation. PACIANO AS CALAMBA LEADER Angered enough by the grievances aired by the Calamba tenants, the Dominicans even raised the rent higher. Because the Rizal family had stopped paying the unreasonable rent, a lawsuit was filed to dispossess them of their lands. The agrarian uproar got worse as the Calamba case which was appealed to the Real Audiencia (highest court in the country) in 1888 had been won by the Dominicans in 1890. Under Paciano’s leadership, the Calamba townsfolk prepared to elevate the case to the Tribunal Supremo (Supreme Court in Madrid). He actively corresponded with Jose who rushed to Madrid to seek legal assistance for his brother. Jose took the service of Marcelo H. del Pilar as their lawyer and tapped every influential person and association he could just to help Paciano win his fight. Unfortunately, Rizal found no Spanish authorities who would fully back up the Calamba tenants’ advocacy. Meanwhile, Valeriano Weyler, the governor general who replaced the impartial Emilio Terrero, sent demolition teams to Calamba. Taking the friars’ side, he ordered to raze to the ground the tenants’ houses. Forced to leave the place within several hours, Rizal’s parents moved in with their daughter Narcisa. This unfortunately resulted in her husband, Antonino Lopez, becoming the center of persecution. After dismantling his house and confiscating his belongings, “Lopez was then ordered deported to Mindoro, but Paciano offered to go in his place” (Bantug, p. 96). Paciano, together with some in-laws, were arrested in Calamba and shipped out of Manila in September 1890. BEING JOSE’S SECOND FATHER Some jokingly suggest that their respective grandfathers should also be mentioned in history for allegedly sharpening the bolos and cleaning the guns of heroes like Andres Bonifacio. But if you were a descendant of Paciano Rizal, you could seriously claim that your forebear has a noteworthy place in Philippine history for he did extensively influence the heroism of none less than the national hero. Acting as Jose’s caring guardian, Paciano brought him to Biñan to study under the tutelage of Justiniano Aquino Cruz. Paciano introduced Jose to the teacher, whom he (Paciano) knew very well because he had been a pupil under the teacher before. In 1872, Paciano also accompanied the young Rizal in taking the entrance exam at the College of the San Juan de Letran and in matriculating instead at the Ateneo Municipal. Paciano even looked for Jose’s boarding house in the Walled City. 27 In choosing a course to take at the University of Santo Tomas, Rizal was said to have originally thought about law. Paciano however warned him that being a lawyer could be problematic, for one might find himself backing a wrong cause. Because he also wished to cure their mother, Jose thus opted to take medicine instead. Tired of discrimination against Filipinos by the Dominican professors, Rizal stopped studying at UST in 1882. The two Rizals then made a secret pact that Jose would go to Spain while his big brother would stay behind and care for their parents. But Jose’s more crucial mission was not merely to continue his medical studies but to ultimately liberate the exploited Filipinos from Spanish tyranny by first widening his political knowledge through exposure to European governments. So, when the day came for Jose to leave, “Paciano woke him before daybreak and gave him 365 pesos for the trip” (Bantug, p. 52). Paciano then took the responsibility in telling their parents about Jose’s leaving and in sustaining the financial needs of his brother abroad. For five years, Paciano sent him monthly stipend of 50 pesos, which was later reduced to only 35. Maintaining a constant watch over Jose, Paciano would tell him where to go and what to do. For instance, when Rizal reached Spain, a letter from Paciano arrived, telling him to proceed to Madrid and reminding him he had gone to Europe to dedicate himself to matters of ‘greater usefulness’. Sometime in November 1885, Rizal also received a letter from his kuya disapproving his plan to transfer to Paris. At the beginning of that year, Paciano disallowed Jose’s intention to return home and advised him to wait for the opportune time for the situation in the Philippines was dangerous for him. When Jose had returned home in 1887, Paciano never left him during the first days after arrival, fearing that his enemies would assault him. When Jose, together with his assigned bodyguard and two brothers-in-law climbed up Mount Makiling one morning, Paciano went with them. Hoisting a white sheet on top of the mountain, they were accused of having erected the German flag. The Rizal brothers nonetheless were able to explain their non-political adventure and were believed in by the officials. Before leaving the country for the second time, Jose wanted to marry his girlfriend, Leonor Rivera, and leave her in a sister’s care. But Paciano was adamant and was said to have told Jose, “Iniisip mo lang ang iyong sarili” (Ocampo, p. 41). Paciano was supposed to have also explained that “it was selfish of Rizal to marry someone, only to leave her behind” (Bantug, p. 76). The passionate bond between the two heroes cannot be overemphasized. Their last memorable moments together perhaps happened in 1891 when 28 Paciano, after a year of being deported, had escaped further persecutions and joined Jose in Hong Kong. With their parents and other family members, they celebrated the year-end holidays together. When Jose was about to be prosecuted, the older Rizal opted to be tortured, which nearly cost his life, than to testify against his brother. Before his execution, the national hero wrote these very emotional words to his beloved kuya: “For more than four years, we have neither seen nor written each other, not for lack of love on your part nor on mine, but because knowing each other as we do, we needed no words to understand each other. Now that I am about to die, I dedicate these last times to you to tell you how sorry I am to leave you alone in the world, bearing the burden of the whole family and our old parents. I think of the hardships you went through to help me in my career and I believe I tried my best to waste no time. My brother, if the fruit is bitter, the fault is not mine, but fate’s…” THE REVOLUTIONARY PACIANO When some members of the Rizal family were peacefully living in Hong Kong in 1891, the rumors of a looming revolution in the Philippines had reached them. Perusing a map of the country, Paciano and Jose were often observed discussing about the probable areas where the revolutionaries would begin to strike. After his brother’s execution in December 1896, Paciano joined the Katipuneros in Cavite under General Emilio Aguinaldo. He was not new to reform and revolutionary organizations. He had been an avid member of Propaganda Movement, soliciting funds to finance the organization and the nationalist paper ‘Diariong Tagalog’. As Katipunero, Paciano was later commissioned as general of the revolutionary forces. He was said to have been elected too as secretary of finance in the Department Government of Central Luzon. Assigned as revolutionary commander in Laguna, he was supposed to have wittingly ordered that firecrackers be used to make the Spaniards believe that the Katipuneros were heavily armed. As a result, the enemies in hiding were flushed out and forced to surrender. During the Philippine-American War, Paciano continued to fight for Philippine independence in his area of jurisdiction in Laguna. During the revolution, he was said to have had several meetings with Apolinario Mabini. Dented by malaria however, Paciano was captured by the Americans in 1900. 29 He was released soon after on the power of his promise that he would lead a peaceful life. PACIANO CHOSE TO LIVE A QUIET LIFE Paciano, in his later years, chose to live a serene life and busied himself in the farm instead. He was supposed to have respectfully declined Governor William Howard Taft’s offer to have an important government position in the government and the bid to seek public office in Laguna. In 1907, when the Philippine Assembly passed a resolution providing for a life pension of P200 a month for his mother, Paciano courteously opposed the plan, declaring that he was responsible to take care of his mother till her death as he promised to the national hero. Paciano never married but he had a daughter by Severina Decena named Emiliana Rizal. A son of Emiliana reported that his lola Severina actually married someone else from Calamba but used to visit her Rizal grandchildren when they were young (Ambeth Ocampo, p. 41). On April 13, 1930, Don Paciano died of tuberculosis at his Los Baños home at age of 79. His remains were buried in the North Cemetery in Manila. His life exemplifies that ‘a brother is a brother’ and reminds us that siblings must stand united and remain loyal to each other. (© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog) 30 SATURNINA RIZAL: THE HERO’S SECOND MOTHER Saturnina Rizal (1850-1913) is the eldest child of Don Francisco and Teodora Alonso. She and her mother provided the little Jose with good basic education that by the age of three, Pepe already knew his alphabet. The first time Jose experienced to ride a casco (a flat-bottomed boat with a roof) was when he and his father visited Saturnina at the La Concordia College in Manila. Saturnina had always been a loving ‘Ate’ Neneng to Jose. When their mother was imprisoned, Saturnina brought the young Jose to Tanauan during the summer vacation of 1873 just to cheer up the sad little brother. On his way to Marseilles in May 1882, Rizal—perhaps missing her ‘ate’—dreamed that he was traveling with Neneng and that their path was blocked by snakes. On September 26, 1882, Neneng offered a diamond ring to Jose, worrying that he had no sufficient money to spend. In June 1885, Saturnina and her husband sent one hundred pesos (P100) to Jose as their contribution to Jose’s expenses in finishing his doctorate degree. Saturnina married Manuel Timoteo Hidalgo of Tanauan, Batangas. Hidalgo was also close to his ‘bayaw’ Jose as the two kept up a correspondence. Through a letter, Hidalgo once informed Rizal of a cholera case in Manila in 1885 and requested Jose to buy for him a Spanish book by Rousseau. For allegedly being a conspirator and representative of Jose Rizal, Hidalgo also experienced deportation (to Bohol) during the so-called Calamba agrarian trouble. Manuel and Saturnina had five children, all of whom had a name which began with letter A: Alfredo, Adela, Abelardo, Amelia, and Augusto. Recent controversial story mentions Saturnina as being with her mother when the latter allegedly tried to poison Teodora Formoso, the wife of Jose Alberto (Teodora Alonso’s brother). The story further alleges that Saturnina and her uncle Jose Alberto were the real parents of Soledad, the supposed youngest sister of Jose. In 1909, Doña Saturnina published Pascual Poblete’s Tagalog translation of the Noli Me Tangere. Jose Rizal, on the other hand, immortalized his sister Neneng through the oil painting he made of her, which is now housed in the Rizal Shrine in Fort Santiago.(© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog) 31 NARCISA RIZAL: THE HOSPITABLE SISTER OF THE HERO Narcisa Rizal (1852-1939) or simply ‘Sisa’ was the third child in the family. Like Saturnina, Narcisa helped in financing Rizal’s studies in Europe, even pawning her jewelry and peddling her clothes if needed. It is said she could recite from memory almost all of the poems of the national hero. Narcisa was perhaps the most hospitable among the siblings. When Don Francisco and Doña Teodora were driven out of their house in Calamba, Narcisa took them in her house. It was with Narcisa also that Josephine Bracken once stayed, when the rest of Rizal's family were suspicious that Rizal’s girlfriend was a spy for the Spanish friars. In August 1896, while being kept under arrest aboard the cruiser Castilla anchored off Cavite, Rizal thanked Narcisa, in a letter, for her hospitality in letting Josephine stay in her home. It was also Narcisa who painstakingly searched for the place where the authorities secretly buried the dead Rizal. She found freshly turned earth at the Paco cemetery where a body had been buried without a box of any kind and with no identification on the grave. She wittingly made a gift to the caretaker to mark the site ‘RPJ’, Rizal’s initials in reverse. Years later, Narcisa and her other siblings dug up the hero’s remains at the spot. Sisa married Antonino Lopez, a teacher and musician from Morong, Rizal. For letting the Rizal parents live in their house, Lopez became the target of Spanish persecution. He was threatened of deportation, his house was dismantled, and the unsecured belongings were confiscated. Narcisa and Antonino had eight children. Their son Antonio (1878-1928) married his first cousin Emiliana Rizal, the daughter of Paciano Rizal by Severina Decena. Narcisa’s daughter Angelica, who had visited Rizal in Dapitan, joined the Katipunan after her uncle’s martyrdom. In an interview by Ambeth Ocampo (p. 47), Narcisa’s grandchildren revealed that their lolo, Antonino Lopez was actually the son of the priest Leoncio Lopez—the ‘cura parroco’ of Calamba from whom Rizal based the character of Fr. Florentino in his El Fili. Substantiating the disclosure, they explained that Narcisa and Antonino, after marriage, lived in Leoncio’s parish house and Antonino inherited all of Leoncio’s books and possessions when the priest died. (© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog) 32 OLYMPIA RIZAL: THE SISTER WHOM THE HERO LOVES TO TEASE Olympia Rizal (1855-1887) is the fourth child in the Rizal family. Jose loved to tease her, sometimes goodhumoredly describing her as his stout sister. Jose’s first love, Segunda Katigbak, was Olympia’s schoolmate at the La Concordia College. Rizal confided to Olympia about Segunda and the sister willingly served as the mediator between the two teenage lovers. It was thus unclear whether it was Olympia or Segunda whom Jose was frequently visiting at La Concordia at the time. Olympia married Silvestre Ubaldo, a telegraph operator from Manila. The couple perhaps had no permanent address for they would stay wherever Silvestre was assigned as telegraph operator. In one of Jose’s letters to his other sisters in Calamba, he wrote, “Is Sra. Ipia (Señora Olympia) there already? Do her eyes still become small when she laughs?” Wherever Olympia and Silvestre were, they corresponded with Jose, telling him updates about the family, like about their son Aristeo. While in Bulacan in October 1882, Olympia wrote Jose about Saturnina’s giving birth and the cholera epidemic in Bulacan and Laguna. Perhaps missing her brother, she asked Rizal to try to come home as soon as possible. In January the next year, Ubaldo and Olympia wrote Jose about the ten Baliwag silk handkerchiefs they sent for his birthday and the unpleasant reactions of friars to Rizal's article in the Diariong Tagalog. In a letter dated June 12, 1885, Olympia asked Jose to write the priest Federico Faura to transfer them back to Calamba. The loving brother thus wrote to P. Faura and Sr. Barrantes on June 28, 1885 requesting them to work for the transfer of his brother-in-law from Albay where the latter was assigned. In March 1887, Olympia informed Jose that her husband was assigned in Manila and that their parents were in good health. Paradoxically, Olympia died of hemorrhage while giving birth on September that same year—an event that spoiled Rizal’s homecoming. Interestingly, about three years before her death, in Jose’s letter to his parents where she talked about the student agitation in Madrid and the condition of the sugar trade, he all of a sudden asked about the condition of Olympia who was then expecting. He even joked about her being a mother, “If her habits haven't changed yet, I fear very much for the skin of that boy: How many pinchings he will get.” 33 Like Jose’s other in-laws, Olympia’s husband did not escape the Spaniards’ persecution. With Paciano, Ubaldo was deported to Mindoro because of the Calamba agrarian trouble. In December 1891, he nonetheless escaped from further oppression in the Philippines and arrived at Hong Kong with Paciano and Don Francisco to join Dr. Rizal there.(© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog) 34 LUCIA RIZAL: PARTAKER OF THE HERO’S SUFFERING Lucia Rizal (1857–1919) is the fifth child in the Rizal family. She married Mariano Herbosa of Calamba, Laguna. Charged of inciting the Calamba townsfolk not to pay land rent and causing unrest, the couple was once ordered to be deported along with some Rizal family members. Lucia’s husband Mariano died during the cholera epidemic in May 1889. He was refused a Catholic burial for not going to confession since his marriage to Lucia. In Jose’s article in La Solidaridad entitled Una profanacion (‘A Profanation’), he scornfully attacked the friars for declining to bury in ‘sacred ground’ a ‘good Christian’ simply because he was the “brother-in-law of Rizal”. In December 1891, the then widowed Lucia was among Rizal’s siblings who were present in their so-called ‘family reunion’ in Hong Kong. She also accompanied Jose when he returned to Manila in June the following year. From July 6 to 15, 1892, Jose however was regrettably imprisoned in Fort Santiago and later deported to Dapitan on a made-up charge that anti-friar pamphlets were found in Lucia’s luggage on board Don Juan. Lucia and Mariano’s children were Delfina, Concepcion, Patrocinio, Teodosio, Estanislao, Paz, Victoria, and Jose. Delfina (1879 –1900) became renowned for being one of the three women (along with Marcela Agoncillo and her daughter Lorenza) who seemed together the Philippine flag. She became the first wife of Gen. Salvador Natividad of the Philippine Revolution. Teodosio (Osio) and Estanislao (Tan) became pupils of their uncle Jose in the school he established in Dapitan. (© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog) 35 MARIA RIZAL: THE HERO’S CONFIDANT Maria Rizal (1859-1945) is the sixth child in the family. It was to her whom Jose talked about wanting to marry Josephine Bracken when the majority of the Rizal family was apparently not amenable to the idea. In his letter dated December 12, 1891, Jose had also brought up to Maria his plan of establishing a Filipino colony in North British Borneo. Jose and Maria’s letters to each other contain many interesting information about their lives. While in Madrid in December 1882, Jose wrote her sister, “since the middle of August I haven't taken a bath and I haven't perspired either. That is so here. It is very cold and a bath is expensive. One pays thirty-five cent for one.” In Maria’s letter dated March 15, 1887, she explained to her slighted (or better yet, ‘nagtatampo’) brother that she got busy that’s why she had not immediately updated him about her new status as married to the “very young man from Biñang whose name is Daniel Faustino Cruz.” A caring family physician, Jose once prescribed through letters a remedy for Maria’s toothache and a treatment for her son Moris (Mauricio). In his letter dated December 28, 1891, Jose wrote to Maria, “I'm told that your children are very pretty.” Today, we have a historical proof that Maria’s progenies were indeed nice-looking (‘lahing maganda’). Maria and Daniel had five children: Mauricio, Petrona, Prudencio, Paz and Encarnacion. Their son Mauricio married Conception Arguelles and the couple had a son named Ismael Arguelles Cruz. Ismael was the father of Gemma Cruz Araneta, the first Filipina to win the Miss International title, the first Southeast Asian to win in an international beauty pageant title. Mauricio ‘Moris’ Cruz became a pupil of his uncle Jose in Dapitan. Updating Maria on the progress of her son, Jose once sent her a letter interestingly describing the ‘lolo’ of our Miss International as “stout and dark and he knows how to swim a little.” Moris—Rizal’s ‘favorite’ nephew whom he further described as using a lot of Manila vulgar expressions—also had a Jesuit priest son, Jose A. Cruz. (© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog) 36 CONCEPCION RIZAL: THE HERO’S FIRST GRIEF Also called ‘Concha’ by her siblings, Concepcion Rizal (1862-1865) was the eight child of the Rizal family. She died at the age of three. Of his sisters, it is said that Pepe loved most the little Concha who was a year younger than him. Jose played games and shared children stories with her, and from her he felt the beauty of sisterly love. When Concha died of sickness in 1865, Jose mournfully wept at losing her. He later wrote in his memoir, “When I was four years old, I lost my little sister Concha, and then for the first time I shed tears caused by love and grief.” From Concha’s life we could learn that not a few children in those times died young. If records are correct, more than ten of Rizal’s nieces and nephews also died young, not to mention that Jose’s child himself experienced the same fate. 37 JOSEFA RIZAL: THE KATIPUNERA Josefa Rizal’s nickname is Panggoy (1865-1945). She’s the ninth child in the family who died a spinster. Among Jose’s letters to Josefa, the one dated October 26, 1893 is perhaps the most fascinating. Written in English, the letter addressed Josefa as “Miss Josephine Rizal”, thereby making her the namesake of Rizal’s girlfriend Josephine Bracken. In the letter, Jose praised her sister for nearly mastering the English language, commenting that the only fault he found in Josefa’s letter is her apparent confusion between the terms ‘they are’ and ‘there’. Jose also wrote about the 20 pesos he sent; the 10 pesos of the amount was supposed for a lottery ticket. This indicates that Jose did not stop ‘investing’ in lottery tickets despite winning 6, 200 pesos in September the previous year. Even when he was in Madrid, he used to spend at least three pesetas monthly for his ‘only vice’ (Zaide, p. 221). After Jose’s martyrdom, the epileptic Josefa joined the Katipunan and is even supposed to have been elected the president of its women section. She was one of the original 29 women admitted to the Katipunan along with Gregoria de Jesus, wife of Andres Bonifacio. They safeguarded the secret papers and documents of the society and danced and sang during sessions so that civil guards would think that the meetings were just harmless social gatherings. (© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog) 38 TRINIDAD RIZAL: THE CUSTODIAN OF THE HERO’S GREATEST POEM Trinidad Rizal (1868-1951) or ‘Trining’ was the tenth child and the custodian of Rizal’s last and greatest poem. In March 1886, Jose wrote to Trining describing how the German women were serious in studying. He thus advised her: “now that you are still young and you have time to learn, it is necessary that you study by reading and reading attentively.” Perhaps sensing that studying is not Trinidad’s thing, Jose continued, “It is a pity that you allow yourself to be dominated by laziness when it takes so little effort to shake it off. It is enough to form only the habit of study and later everything goes by itself.” Four years later, Trining surprised Jose by writing him, “Dearest Brother: I left the College two years, one month and a half ago.” In August 1893, Trinidad, along with their mother, joined Rizal in Dapitan and resided with him in his casa cuadrada (square house). It is said that Trinidad had once planned Rizal’s escape from his exile. In January 1896, Jose invited Trinidad to return to Dapitan. Jose though had one hesitation: “The difficulty is, whom are you going to marry here? The town is lonely still, for there is almost no one.” Trining once wrote to Jose: “I have read your letter to our brother Paciano in which you asked how I'm getting along with Señora Panggoy. Thank God we are getting along well and we live together peacefully.” Never married, Trinidad and Josefa lived together until their deaths. Right before Jose’s execution, Trinidad and their mother visited him in the Fort Santiago prison cell. As they were leaving, Jose handed over to Trining an alcohol cooking stove, a gift from the Pardo de Taveras, whispering to her in a language which the guards could not understand, “There is something in it.” That ‘something’ was Rizal’s elegy now known as “Mi Ultimo Adios”. Like Josefa and two nieces, Trinidad joined the Katipunan after Rizal’s death. In 1883, Trining was in bed for five months, from April to August, being sick with intermittent fever—that kind which rises and falls and then returns, occurring in diseases such as malaria. Astonishingly however, she was the last of the family to die. (© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog) 39 SOLEDAD RIZAL: THE HERO’S CONTROVERSIAL SISTER Also called ‘Choleng’, Soledad Rizal (1870-1929) was the youngest child of the Rizal family. Being a teacher, she was arguably the best educated among Rizal’s sisters. In his long and meaty letter to Choleng dated June 6, 1890, Jose told her sister that he was proud of her for becoming a teacher. He thus counseled her to be a model of virtues and good qualities “for the one who should teach should be better than the persons who need her learning.” Rizal nonetheless used the topic as leverage in somewhat rebuking her sister for getting married to Pantaleon Quintero of Calamba without their parents’ consent. “Because of you”, he wrote, “the peace of our family has been disturbed.” Some timeless lessons in ethics and good manners can be learned from the letter. For instance, it reveals that Jose was very much against women who allow themselves to be courted outside their homes. He said to Choleng, “If you have a sweetheart, behave towards him nobly and with dignity, instead of resorting to secret meetings and conversations which do nothing but lower a woman's worth in the eyes of a man… You should value more, esteem more your honor and you will be more esteemed and valued.” (Copyright by author Jensen DG. Mañebog) 40 RIZAL’S BIRTH Donya Teodora was said to have suffered the greatest pain during the delivery of her seventh child, Jose. Her daughter Narcisa recalled: “I was nine years of age when my mother gave birth to Jose. I recall it vividly because my mother suffered great pain. She labored for a long time. Her pain was later attributed to the fact that Jose’s head was bigger than normal.” Jose Rizal was born in Calamba. In 1848, his parents decided to build a home in his town in Laguna. The name Calamba was derived from kalan banga, which means “clay stove” (kalan) and “water jar” (banga). Jose’s adoration of its scenic beauty-punctuated by the sights of the Laguna De Bay, Mount Makiling, palm covered mountains, curvy hills, and green fields- it was recorded in the poem he would later write at Ateneo De Manila in 1876. Un Recuerdo A Mi Pueblo (In Memory of my town). (if Rizal’s poem were written today, he might mention the three-floor SM mall, shopping centers, and the South Luzon Expressway terminus in the place.) The first massive stone house in Calamba was the birthplace of our national hero. It was a two-storey building. Its architectural style and proximity to the church implied Rizal Family’s wealth and political influence. THE CHILDHOOD OF A PHENOM Jose Rizal’s first memory, in his infancy, was his happy days in their family garden when he was three years old. Because the young Pepe was weak, sickly, and undersized, he was given the fondest care by his parents, so his father built a nipa cottage for Pepe to play in daytime. Another childhood memory was the daily Angelus prayer in their home, Rizal recorded in his memoir that by nightfall, his mother would gather all the children in their home to pray the Angelus. At the early age of three, he started to take a part in family prayers. At the age of five, the young Pepe learned to read the Spanish family Bible, which he would refer to later in his writings. Rizal himself remarked that perhaps the education he received since his earliest infancy was what had shaped his habits. As a child, Rizal loved to go to chapel, pray, participate in novenas, and join religious procession. In Calamba, one of the men he esteemed and respected was the scholarly Catholic priest Leoncio Lopez, the town priest. He used to visit him and listen to his inspiring opinions on current events and through life views. also, at the age of five, Pepe started to make pencil sketches and mold in clay 41 and wax objects, which attracted his fancy. When he was about six years old, his sister once laughed at him for spending much time making clay and wax images. Initially keeping silent, he then prophetically told them “all right laugh at me now! Someday when I die, people will make monuments and images for me. “ When Jose was seven years old, his father provided him the exciting experience of riding a “casco” (a flat-bottomed boat with a roof) on their way to a pilgrimage in Antipolo. The Pilgrimage was to fulfill the vow made by Jose’s mother to take him to the shrine of Virgin of Antipolo should she and her child survive the ordeal of delivery, which nearly caused her life. From Antipolo, Jose and his father proceeded to Manila to visit his sister Saturnina who was at the time studying at La Concordia College. In Sta. Ana, Manila. As a gift, the child Jose received a pony named “Alipato” from his father. As a child, he loved to ride his pony or take long walks in the meadows and lakeshore with his black dog named “Usman”. The mother also induced Jose to love the arts, literature and the classics. Before he was eight years old, he had written a drama (some source say Tagalog comedy) which was which the municipal captain rewarded him with two pesos (some references specify that It was staged in a Calamba festival and that it was a gobernadorcillo from Paete who purchased the manuscript of two pesos.) Contrary to the “former” common knowledge however, Rizal did not write the Filipino poem “Sa Aking Mga Kababata/kabata” (To My Fellow Children). The poem was previously believed to be Rizal’s first written poem at the age of eight and was said to have been published posthumously many years after Rizal’s death. However, Jose had a preserved correspondence (letters) with his brother Paciano admitting that he (Jose) had only encountered the word “Kalayaan” when he was already 21 years old. The term (“Kalayaan”) was used not just once in the poem “Sa Aking Mga Kababata/kabata” (for more details concerning this matter, read the article, “Did Jose Rizal Write the Poem “Sa Aking Mga Kababata”) The young Rizal was also interested in magic. He read many books on magic. He learned different tricks such as making a coin disappear and making a handkerchief vanish in air. Some other influences of Rizal’s childhood involved his three uncles: his Tio Jose Alberto who inspired him to cultivate his artistic ability; his Tio Manuel who encouraged him to fortify his frail body through physical exercises; and his Tio Gregorio who intensified Rizal’s avidness to read good books. 42 JOSE RIZAL AND HIS CHINESE ANCESTORS National hero Jose Rizal would have been known as Jose Co, the greatgreat grandson of Siang Co and Zun Nio from Fujian, China. Although Rizal now has several streets, provinces and barrios named after him for his martyrdom, many still wonder why his father had a different surname. Jose Protacio Mercado y Alonso, popularly known as Jose Rizal was the seventh of 11 children of Francisco Engracio Mercado and Teodora Alonso of Biñan Laguna. The national hero traced his roots to the village of Sionque in the district of Chin-Chew, Fujian. From Fujian, Siang Co and Zun Nio a son, Lam Co migrated to the Philippines in 1690. At 35, Co was baptized into the Catholic faith in Binondo, acquiring his Christian name - Domingo Co - and married a Chinese mestiza, Ines de la Rosa. Co was close friends with Spanish friars Francisco Marquez and Juan Caballero who had enticed him to settle in the friars an estate in San Isidro Labrador in Biñan, where he helped develop the irrigation system in the area. The union of Co and Dela Rosa produced a son in 1731. The offspring acquired the Christian name Francisco Mercado. Francisco was derived from one of Co's friar friends while Mercado meant 'market' in Spanish, signifying his future job as trader. The young Francisco married Bernarda Monica, a native of the nearby hacienda in San Pedro, Laguna and born children Clemente and Juan, who would be Rizal's grandfather. In 1783, Francisco Mercado was elected gobernadorcillo (municipal mayor) of Biñan while Rizal's grandfather Juan Mercado was elected Capitan del pueblo of the same town in 1808, 1813 and 1823. Juan Mercado married Cirila Alejandro, a Chinese mestiza, and had 13 children, one of them Rizal's father Francisco Engracio Mercado. Rizal's grandfather died when Francisco Engracio was only eight, and the child helped his widowed mother run the family business. Francisco Engracio was studying Latin and Philosophy at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran when he met his wife Teodora Alonso y Realonda who was studying in Colegio de Sta. Rosa. Francisco Engracio and Teodora raised their family in the rented estate from the Dominican Order and produced rice, corn and sugarcane. In 1848, Governor General Narciso Claveria decreed that Filipinos and Chinese immigrants adopt Spanish family names and Francisco Mercado opted to adopt Ricial which means green fields. However, his new surname confused many of his business associates and patrons, forcing him to change it to Rizal Mercado. 43 In 1865 during his studies in Ateneo Municipal de Manila, Jose Protacio Rizal Mercado dropped his second last name to disassociate himself from his brother Paciano who was then under surveillance of Spanish authorities because of his links with the martyred Filipino priests Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos and Jacinto Zamora. Rizal also needed a fresh identity so he could travel freely abroad without the hassles of Spanish inquisition. Today in Philippine History, May 11, 1818, Francisco Mercado was born in Biñan, Laguna. 44 JOSE RIZAL: THE ADVENTUROUS VOYAGER HE DID GO PLACES! Jose Rizal’s thrilling experience during his first lake-and-river voyage perhaps inspired him to travel more. Riding in a ‘casco’, Jose temporarily left his hometown Calamba on June 6, 1868. He and his father went on a pilgrimage to Antipolo and afterward visited his sister Saturnina in Manila, who was at the time a student at La Concordia. Across Laguna de Bay and the Pasig River, Jose had an unforgettably amazing trip that he did not fail to record the journey in his memoir. IN BIÑAN AND MANILA A year after, Paciano brought Jose to the nearby town Biñan to attend the school of Maestro Justiniano Aquino Cruz. Except for occasional homecomings, he stayed in the town for a year and a half of schooling, living in an aunt’s house where his breakfasts generally consisted of a plate of rice and two dried sardines (‘tuyo’). Don Francisco sent Jose to Manila in June 1872 to enroll in Ateneo Municipal. Paciano found Jose a boarding house in Intramuros though Jose later transferred to a house on Calle Carballo in Santa Cruz area. The following year, Jose transferred residence to No. 6 Calle Magallanes. Two years after, he became an intern (boarding student) in Ateneo and stayed there until his graduation in the institution. From 1877 to 1882, Rizal studied in the University of Santo Tomas, enrolling in the course on Philosophy in Letters, but shifted to Medicine a year after. During his first year in UST, he simultaneously took in Ateneo a vocational course leading to being an expert surveyor. He boarded in the house of a certain Concha Leyva in Intramuros, and later in “Casa Tomasina”, at Calle 6, Santo Tomas, Intramuros. In ‘Casa Tomasina’, his landlord-uncle Antonio Rivera had a daughter, Leonor, who became Jose’s sweetheart. IN EUROPE Sick and tired of the discriminatory and oppressive Dominican professors, Rizal stopped attending classes at UST in 1882. On May 3 of that year, he left for Spain to complete his studies and widen his political knowledge through exposure to European governments. It’s funny that his departure for Spain had gone down to history as a ‘secret departure’ although at least ten sure people—including his three siblings and an uncle—collaborated in his going away, exclusive of the unnamed and unnumbered ‘Jesuit priests’ and ‘intimate friends’ who coconspired in the plan. 45 On his way to Madrid, Rizal had many stopovers. He first disembarked and visited the town of Singapore. Onboard the steamship ‘Djemnah’ he passed through Punta de Gales, Colombo and Aden. En route to Marseilles, he also went across the historic waterway of Suez Canal and visited the Italian city of Naples. He left Marseilles, France for Barcelona in an express train. After some months, Rizal left Barcelona for Madrid and enrolled in Medicine and Philosophy and Letters at the Universidad Central de Madrid on November 3, 1882. In Rizal’s letter dated February 13, 1883, he informed Paciano of his meeting with other Filipinos: “The Tuesday of the Carnival we had a Filipino luncheon and dinner in the house of the Paternos, each one contributing one ‘duro’. We ate with our hands, boiled rice, chicken adobo, fried fish and roast pig.” Ironically, a year after that sumptuous feasting, Rizal became penniless as his family encountered economic regression. One day in June 1884, Rizal who failed to eat breakfast still went to school and even won a gold medal in a contest. At night, he attended the feast held in honor of two award-winning Filipino painters, Juan Luna and Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo. In the occasion, he delivered a daring liberal speech which became so controversial that it even caused sickness to his worrying mother. Perhaps, being broke and hungry could really make one braver and more impulsive. As one student commented, “Hayop man, ‘pag gutom, tumatapang.” In 1885, Rizal who had finished his two courses in Madrid went to Paris, France. From November 1885 to February 1886, he worked as an assistant to the celebrated ophthalmologist, Louis de Weckert. In February 3, 1886, he left Paris for Heidelberg, Germany. He attended lectures and training at the University of Heidelberg where he is said to have completed his eye specialization. Afterward, Rizal settled for three months in the nearby village, Wilhemsfeld, at the pastoral house of a Protestant pastor, Dr. Karl Ullmer. It was also during this time that the correspondence and long-distance friendship between Jose and Ferdinand Blumentritt began. Rizal wrote a letter in German and sent it with a bilingual (Spanish and Tagalog) book ‘Aritmiteca’ to Blumentritt who was interested in studying Jose’s native language. Jose traveled next to Leipzig and attended some lectures at its university. Having reached Dresden afterward, he met and befriended Dr. Adolph B. Meyer, the Director of the Anthropological and Ethnological Museum. Also, a 46 Filipinologist, Meyer showed Rizal some interesting things taken from tombs in the Philippines. In November 1886, he went to Berlin and further enhanced his skills and knowledge in ophthalmology. In that famous city, not only did he learn other languages but also became member of various scientific communities and befriended many famed intellectuals at the time. On February 21, 1887, he finished his first novel and it came off the press a month later. GRAND EUROPE TOUR With his friend Maximo Viola who loaned him some amount to cover for the printing of the ‘Noli’, Rizal traveled to various places in Europe. Through Paciano’s remittance, Jose had paid Viola and decided to further explore some places in Europe before returning to the Philippines. They went first to see Potsdam, a city southwest of Berlin which became the site of the Potsdam Conference (1945) at which the leaders of powerful nations deliberated upon the postwar administration of Germany. On May 11, 1887, they left Berlin for Dresden and witnessed the regional floral exposition there. Wanting to visit Blumentritt, they went to Leitmeritz, Bohemia passing through Teschen (Decin, Czechoslovakia). Professor Blumentritt warmly received them at Leitmeritz railroad station. The professor identified them through the pencil sketch which Rizal had previously made of himself and sent to his European friend. Blumentritt acted as their tour guide, introducing them to his family and to famous European scientists like Dr. Carlos Czepelak and Prof. Robert Klutschak. On May 16, the two Filipinos left Leitmeritz for Prague where they saw the tomb of the famous astronomer Copernicus. They stopped at Brunn on their way to Vienna. They met the famed Austrian novelist Norfenfals in Vienna, and Rizal was interviewed by Mr. Alder, a newspaper correspondent. To see the sights of the Danube River, they left Vienna on a boat where they saw passengers using paper napkins. From Lintz, they had a short stay in Salzburg. Reaching Munich, they tasted the local beer advertised as Germany’s finest. In Nuremberg, they saw the infamous torture machines used in the so-called Catholic Inquisition. Afterward, they went to Ulm and climbed Germany’s tallest cathedral there. They also went to Sttutgart, Baden, and then Rheinfall where they saw Europe’s most beautiful waterfall. 47 In Switzerland, they toured Schaffhausen, Basel, Bern, and Lausanne before staying in Geneva. Rizal’s 15-day stay in Geneva was generally enjoyable except when he learned about the exhibition of some Igorots in Madrid, side by side some animals and plants. Not only did the primitive Igorots in ‘bahag’ become objects of ridicule and laughter, one of them (a woman) also died of pneumonia. On June 19, 1887, Rizal treated Viola for it was his 26th birthday. Four days after, they parted ways—Viola went back to Barcelona while Rizal proceeded to Italy. In Italy, Rizal went to see Turin, Milan, Venice, and Florence. In Rome, he paid a visit to the historical places like the Amphitheatre and the Roman Forum. On June 29, he had seen the glorious edifices, like the St. Peter’s Church, in the Vatican City. Literally and figuratively speaking, Rizal did go places. As a coprofessor commented, “Nag-gala talaga ang lolo mo!” FIRST HOMECOMING Despite being warned by friends and loved ones, Jose was adamant in his decision to return to his native land. From a French port Marseilles, he boarded on July 3 the steamer ‘Djemnah’ which sailed to the East through the Suez Canal and reached Saigon on the 30th of the month. He then took the steamer ‘Haiphong’ and reached Manila near midnight of August 5. After meeting some friends in Manila, he returned to Calamba on August 8. Restoring his mother’s eyesight, he began to be dubbed as “German doctor” or “Doctor Uliman” (from the word ‘Aleman’ which means German) and made a lot of money because people from different places flocked him for a better vision. Because of his enemies’ allegation that ‘Noli’ contained subversive ideas, Rizal was summoned by the Governor General Emilio Terrero. Seeing no problem in the book, Terrero nonetheless assigned to Rizal a body guard, Don Jose Taviel de Andrade, to protect the ‘balikbayan’ from his adversaries. In December 1887, the Calamba folks asked Rizal’s assistance in collecting information as regards Dominican hacienda management. It was in compliance to the order of the government to investigate the way friar estates were run. So, Rizal had reported, among others, that the Dominican Order had arbitrarily increased the land rent and charged the tenants for nonexistent agricultural services. The enraged friars pressured the governor general to ‘advise’ the author of the ‘Noli’ to leave the country. (In other words, “napuno na talaga sa kanya ang nga pari”) 48 SECOND TRAVEL ABROAD What Rizal failed to accomplish in his six-month stay in the country was visiting his girlfriend Leonor Rivera in Pangasinan. His father strongly opposed the idea, sensing that the visit would put Leonor’s family in jeopardy. On February 3, 1888, Rizal sailed to Hongkong onboard ‘Zafiro’ and just stayed inside the ship during its short stop at Amoy. He stayed at Victoria Hotel in Hongkong (not in Sta. Mesa) and visited the nearby city Macao for two days along with a friend, Jose Maria Basa. Among other things, Rizal experienced in Hong Kong the noisy firecracker-laden Chinese New Year and the marathon lauriat party characterized by numerous dishes being served. (The ‘lauriat’ combo meal in ‘Chowking’ originated from this Chinese party.) From Hong Kong, he reached Yokohama, Japan on February 28 and proceeded to Tokyo the next day. He lived in the Spanish legation in Tokyo upon the invitation of its secretary, Juan Perez Caballero. In March 1888, he heard a Tokyo band nicely playing a European music and was astonished to find out after the gig that some of its members were Filipinos (Zaide & Zaide, p. 130). We can surmise from this that even during Rizal’s time, some Filipinos were already entertainers in Japan (‘Japayuki’ or ‘Japayuko’). But if there were a person who was truly entertained at the time, it was Rizal himself who was amused by the Japanese girl who used to pass by the legation every day. The 23-year old Seiko Usui whom he fondly called ‘O-Sei-San’ became his tour guide and sweetheart rolled into one. SAIL TO THE WEST Because he loved his mission more than O-Sei-San, he boarded the ‘Belgic’ on April 13, 1888. In the vessel, he had befriended Tetcho Suehiro, a Japanese novelist and human rights fighter who was also forced by his government to leave his country. The ship arrived in San Francisco on April 28. For a week, they were however quarantined, allegedly because of the cholera outbreak in the Far East. In reality, some politicians were just questioning the arrival of the Chinese coolies in the ship who would displace white laborers in railroad construction projects. On May 6, he went to Oakland. Onboard a train, he took his evening meal at Sacramento and woke up at Reno, Nevada. He had visited also the states of Utah, Colorado, Nebraska, Illinois, and finally reached New York on May 13. On Bedloe Island, he had seen the Statue of Liberty symbolizing freedom and democracy. Inconsistently, Rizal observed that there was racial inequality in the 49 land and real freedom was only for the whites. But if Rizal were alive today, he would be surprised that the Americans have already allowed a black guy to become their president for two terms. IN GREAT BRITAIN On May 16, 1888 on the ship ‘City of Rome’ Rizal sailed for Liverpool and arrived on May 24. A day after, he reached London and stayed briefly at Dr. Antonio Ma. Regidor's home. He then boarded at the Beckett family where he fell in love with Gertrude, the oldest daughter of his landlord. In June 1888, Rizal made friends with Dr. Reinhold Rost and his family. Expert in Malayan language, Rost had in his house a good Filipiniana library. Our national hero was described by Rost as “a pearl of a man” (‘una perla de hombre’). In London, Rizal manually copied and annotated Morga’s ‘Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas’, a rare book available in the British Museum. He also became the honorary president of the patriotic society Asociacion La Solidaridad (Solidaridad Association) and wrote articles for the ‘La Solidaridad’. In his 10-month stay in London, he had short visits in Paris, Madrid, and Barcelona. In Spain, he met Marcelo H. del Pilar for the first time. IN FRANCE Leaving London for good, he went to Paris in March 1889. He shortly lived in the house of a friend, Valentin Ventura before transferring in a little room where he had as roommates two Filipinos, one of which was Jose Albert, a student from Manila. In Paris, Rizal frequented the Bibliotheque Nationale, working on his annotation of the ‘Sucesos’. He spent his spare hours in the houses of friends like Juan Luna and his wife Paz Pardo de Tavera. Rizal witnessed the Universal Exposition of Paris, having as its greatest attraction the Eiffel Tower.He formed the ‘Kidlat Club’, a temporary social club which brought together Filipinos witnessing the exposition. He also organized the ‘Indios Bravos’, an association which envisioned Filipinos being recognized for being admirable in many fields, and the mysterious Redencion de los Malayos (Redemption of the Malays) which aimed to propagate useful knowledge. In Paris, Rizal also finished and published his annotation of the ‘Sucesos.’ 50 IN BELGIUM After celebrating the Yuletide season in Paris in 1889, Rizal shortly visited London for the last time. With Jose Albert, Rizal left Paris for Brussels on January 28, 1890. The two stayed in a boarding house administered by the Jacoby sisters (Suzanne and Marie) where Rizal met and had a transitory affair with Petite, the niece of his landladies. In Belgium, Rizal busied himself with writing the ‘Fili’ and contributing for La Solidaridad using the pen names Dimas Alang and Laong Laan. When he heard the news that the Calamba agrarian trouble was getting worse, Rizal decided to go home. But Paciano told him through a letter that they lost the court case against the Dominicans in the Philippines and they intended to bring the case to Madrid. This prompted Jose to go to Madrid instead to look for a lawyer and influential people who would defend the Calamba tenants. IN MADRID Rizal traveled to Madrid in August 1890. Along with his lawyer, Marcelo H. Del Pilar, he tried to seek justice for his family but could not find anyone who could help him. Rizal encountered many adversities and tribulations in Madrid. He heard that his family was forced to leave their land in Calamba and some family members were even deported to far places. One day, Rizal challenged his friend Antonio Luna to a duel when he (Luna), being unsuccessful in seeking Nellie Boustead’s love, gave negative comments on the lady. Rizal also dared to a duel Wenceslao Retana of the anti-Filipino newspaper ‘La Epoca’ who wrote that Rizal’s family did not pay their land rent. Both duels were fortunately aborted— Luna became Rizal’s good friend again and Retana even became Rizal’s first non-Filipino biographer. In Madrid, Rizal also heard the news of Leonor Rivera's marriage with an Englishman Henry Kipping who was the choice of Leonor’s mother. As if ‘misfortunes’ were not enough, there emerged the Del Pilar-Rizal rivalry for leadership in the Asociacion Hispano Filipino. The supposedly healthy election for a leader (‘Responsible’) produced divisive unpleasant split among the Filipinos in Madrid (the Rizalistas vs. the Pilaristas). Rizal thus decided to leave Madrid, lest his presence results in more serious faction among Filipinos in Madrid. 51 IN BIARRITZ, PARIS, AND BRUSSELS Rizal proceeded to take a more than a month vacation in Biarritz, a tourist town in southwestern France noted for its mild climate and sand beaches. Arriving there in February 1891, Rizal was welcomed as a family guest in the house of the Bousteds, especially by Nellie whom he had a serious (but failed) romantic relationship. In Biarritz, he continued to worked on his ‘El Fili’ and completed its manuscript on March 29, the eve of his departure for Paris. Valentin Ventura hosted his short stay in Paris, and the Jacobies, especially Petite Suzanne, cordially welcomed his arrival in Brussels in April 1891. In Brussels, Rizal revised and prepared for printing his second novel until the end of May. By June 1891, he was already looking for a printing firm to print the ‘El Filibusterismo.’ IN GHENT Rizal went to Ghent in July 1891 because the cost of printing in the place was cheaper. He lived in a low-cost boarding house where he had as roommate Jose Alejandro, an engineering student in the University of Ghent. Tightening their belts, they rented a room exclusive of breakfast. They bought a box of biscuit, counted the contents, and computed for their daily ration for a month. In just 15 days, Alejandro had eaten up all his shares whereas Rizal frugally limited himself to his daily allocation. The publisher F. Meyer-Van Loo Press, No. 66 Viaanderen Street agreed to print the ‘El Fili’ on installment basis. Despite pawning all his jewels and living tightfistedly, Rizal run out of funds and the printing had to be suspended on August 6. But through Valentin Ventura’s ‘salvific’ act, the ‘El Filibusterismo’ came off the press on September 18, 1891. Two weeks after, he visited Paris for the last time to bid goodbye to his friends and compatriots. IN HONG KONG AND SANDAKAN In October 1891, Rizal left Europe for Hong Kong onboard the ship ‘Melbourne’ on which he began writing his third (but unfinished) novel. He arrived in Hong Kong on November 20 and resided at No. 5 D’ Aguilar Street, No. 2 Rednaxela Terrace. (In case you did not notice, ‘Rednaxela’ is ‘Alexander’ spelled reversely). Having escaped the friars’ persecution, Don Francisco, Paciano, and Silvestre Ubaldo (Jose’s brother-in-law) also arrived in Hong Kong. Shortly after, 52 Doña Teodora and children Lucia, Josefa, and Trinidad also came, and the Rizal family had a sort of family reunion in the Yuletide season of 1891. In Hong Kong, Jose opened a medical clinic. A Portuguese friend, Dr. Lorenzo P. Marques helped him to have plentiful patrons of various nationalities. His successful operation on his mother’s left eye allowed her to read again. In March 1892, he went to Sandakan (East Malaysia) aboard ‘Menon’ to negotiate with British authorities concerning the founding of a Filipino colony in North Borneo (now called Sabah). On March 21, Rizal asked Governor General Eulogio Despujol through a letter to allow the landless Filipinos, especially the deported Calamba tenants, to establish themselves in North Borneo. Rizal was back in Hon Kong in April, 1892. SECOND HOMECOMING Wanting to confer with Despujol concerning his North Borneo colonization project, Rizal left Hong Kong on June 21, 1892 along with his sister Lucia. Without his knowledge, the Spanish consul in Hong Kong sent a cablegram to Despujol stating figuratively that “the rat is in the trap”. A secret case against Rizal was thus filed in Manila for anti-religious and anti-patriotic public campaign. Rizal and his sister arrived in Manila at 12:00 noon of June 26, 1892. At 7 pm, he was able to confer in Malacañan with Despujol who agreed to pardon his father and told him to return on June 29. He then visited sisters and friends in Manila. On June 27, he took a train and visited his friends in Central Luzon. He had a stopover at the Bautista mansion in Malolos, Bulacan and spent the night in the house of Evaristo Puno in Tarlac, Tarlac, about 30 kilometers away from the residence of Leonor Rivera-Kipping in Camiling. He also went to San Fernando and Bacolor, Pampanga and returned to Manila on June 28, at 5 pm. On June 29, 30, and July 3, he had other interviews with Despujol. The colonization project was rejected though Rizal’s request to lift the exile of his sisters was granted. On the evening of July 3, Rizal spearheaded the meeting in the house of Doroteo Ongjunco on Ylaya Street, Tondo, Manila of at least 20 Filipinos, including Andres Bonifacio and Apolinario Mabini. Rizal explained the aims of the civic association ‘La Liga Filipina’. Officers were then elected, having Ambrosio Salvador as the president, thereby officially establishing the league. 53 Just three days after though, Rizal was arrested during his interview with the governor general. Despujol showed him anti-friar leaflets ‘Pobres Frailes’ (Poor Friars) allegedly discovered in his sister Lucia’s pillow cases. Imprisoned in Fort Santiago for almost ten days, Rizal was brought at 12:30 am on July 14 to the steamer ‘Cebu’. Passing through Mindoro and Panay, the vessel docked at Dapitan in Zamboanga del Norte on the evening of July 17. True, Dapitan is a scenic place with fine beaches, perhaps a soothing place for a ‘balik-bayan’ like Rizal. But Jose was not there as a tourist or a vacationer—he was an exile. The ship captain Delgras handed him over to the local Spanish commandant, Ricardo Carnicero and that signaled the start of Rizal’s life as a deportee in Dapitan. (© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog) 54 THE FAMILIAR STATEMENT that Doña Teodora was Rizal’s first teacher is not just a sort of ‘venerating’ his mother who sacrificed a lot for our hero. It was a technical truth. In his memoirs, Rizal wrote, “My mother taught me how to read and to say haltingly the humble prayers which I raised fervently to God.” EDUCATION IN CALAMBA In Rizal’s time, seldom would one see a highly educated woman of fine culture like Doña Teodora who had the capacity to teach Spanish, reading, poetry, and values through rare story books. Under her supervision, Rizal had thus learned the alphabet and the prayers at the age of three. Aside from his mother, his sister Saturnina and three maternal uncles also mentored him. His uncle Jose Alberto taught him painting, sketching, and sculpture. Uncle Gregorio influenced him to further love reading. Uncle Manuel, for his part, developed Rizal’s physical skills in martial arts like wrestling. To further enhance what Rizal had learned, private tutors were hired to give him lessons at home. Thus, Maestro Celestino tutored him and Maestro Lucas Padua later succeeded Celestino. Afterward, a former classmate of Don Francisco, Leon Monroy, lived at the Rizal home to become the boy’s tutor in Spanish and Latin. Sadly, Monroy died five months later. (Of course, there is no truth to some students’ comically malicious insinuation that Rizal had something to do with his death.) EDUCATION IN BIÑAN Rizal was subsequently sent to a private school in Biñan. In June 1869, his brother Paciano brought him to the school of Maestro Justiniano Aquino Cruz. The school was in the teacher’s house, a small nipa house near the home of Jose’s aunt where he stayed. In Rizal’s own words, his teacher “knew by the heart the grammars by Nebrija and Gainza.” During Rizal’s first day in Biñan school, the teacher asked him: “Do you know Spanish?” ” A little, sir,” replied Rizal. ” Do you know Latin?” ” A little, sir.” Because of this, his classmates, especially the teacher’s son Pedro, laughed at the newcomer. So later in that day, Jose challenged the bully Pedro to a fight. Having learned wrestling from his Uncle Manuel, the younger and smaller Jose had defeated his tormenter. Compared to bullying victims today, we can say that 55 Rizal did not wait for anyone to enact a law against bullying, but rather took matters into his own hands. After the class however, he had an arm-wrestling match with his classmate Andres Salandanan in which Jose lost and even almost cracked his head on the sidewalk. That only proves that merely being a ‘desperado’ won’t make you win all your fights. In the following days, Jose was said to have had other fights with Biñan boys. (If his average was two fights per day, as what happened during his first day in Biñan school, then he might have been more active than today’s MMA [mixed martial arts] fighters). For his scuffles, he nonetheless received many whippings and blows on the open palm from his disciplinarian teacher. Rizal may have not won all his brawls but he nevertheless beat all Biñan boys academically in Spanish, Latin, and other subjects. EDUCATION IN MANILA There’s a claim that from Biñan school, Rizal studied in Colegio de San Juan de Letran. The story states that after attending his classes for almost three months in Letran, Jose was asked by the Dominican friars to look for another school due to his radical and bold questions. However, standard biographies agree that Rizal just took the entrance examination in that institution but Don Francisco sent him to enroll instead in Ateneo Municipal in June 1872. Run by the Jesuit congregation (Society of Jesus), Ateneo upheld religious instruction, advanced education, rigid discipline, physical culture, and cultivation of the arts, like music, drawing, and painting. Ironically, this school which is now the archrival of La Salle in being exclusively luxurious, among others, was formerly the ‘Escuela Pia’ (Charity School)—a school for poor boys in Manila established by the city government in 1817. Paciano found Jose a boarding house in Intramuros but he later transferred to the house of a spinster situated on Calle Carballo in Santa Cruz area. There he became acquainted with various mestizos that were said to be begotten by friars. (Jose perhaps had not thought twice to befriend them, believing that they were probably nice people—for after all, they were ‘mga anak ng pari’ [children of priests]). 56 To encourage healthy competitions, classes in Ateneo were divided into two groups which constantly competed against each other. One group, named the Roman Empire, comprised the interns (boarders) while the other one, the Carthaginian Empire, consisted of the externs (non-boarders). Within an empire, members were also in continuous competition as they vied for the top ranks called dignitaries— Emperor, being the highest position, followed by Tribune, Decurion, Centurion, and Standard-Bearer, respectively. Initially placed at the tail of the class as a newcomer, Jose was soon continually promoted—that just after a month, he had become an Emperor, receiving a religious picture as a prize. When the term ended, he attained the mark of ‘excellent’ in all the subjects and in the examinations. The second year, Jose transferred residence to No. 6 Calle Magallanes and he obtained a medal at the end of that academic term. In the third year, he won prizes in the quarterly examinations. The following year, his parents placed him as intern (boarding student) in the school and stayed there until his graduation. At the end of the school year, he garnered five medals, with which he said he could somewhat repay his father for his sacrifices. On March 23, 1877, he received the Bachelor of Arts degree, graduating as one of the nine students in his class declared ‘sobresaliente’ or outstanding. Some of his priest-professors in Ateneo were Jose Bech, a man with mood swings and somewhat of a lunatic and of an uneven humor; Francisco de Paula Sanchez, an upright, earnest, and caring teacher whom Rizal considered his best professor; Jose Vilaclara; and a certain Mineves. At the Ateneo, Rizal cultivated his talent in poetry, applied himself regularly to gymnastics, and devoted time to painting and sculpture. Don Augustin Saez, another professor, thoughtfully guided him in drawing and painting, and the Filipino Romualdo de Jesus lovingly instructed him in sculpture. In 1877, Rizal enrolled in the University of Santo Tomas, taking the course on Philosophy in Letters. At the same time, he took in Ateneo a land surveyor and assessor's degree (expert surveyor), a vocational course. He finished his surveyor's training in 1877, passed the licensing exam in May 1878, though the license was granted to him only in 1881 when he reached the age of majority. After a year in UST, Jose changed course and enrolled in medicine to be able to cure the deteriorating eyesight of his mother. But being tired of the discrimination by the Dominican professors to Filipino students, he stopped attending classes at UST in 1882. It’s worthwhile to note that Rizal’s another reason for not completing medicine in UST was that the method of instruction was 57 obsolete and repressive. Rizal’s observation perhaps had served as a challenge for UST to improve in its mode of instructions. If records were accurate, Rizal had taken a total of 19 subjects in UST and finished them with varied grades, ranging from excellent to fair. Notably, he got ‘excellent’ in all his subjects in the Philosophy course. EDUCATION IN EUROPE On May 3, 1882, he left for Spain and enrolled in Medicine and Philosophy and Letters at the Universidad Central de Madrid on November 3. In some days of November 1884, Rizal was involved in the chaotic student demonstrations by the Central University students in which many were wounded, hit by cane, arrested, and imprisoned. The protest rallies started after Dr. Miguel Morayta had been excommunicated by bishops for delivering a liberal speech, proclaiming the freedom of science and the teacher, at the opening ceremony of the academic year. Incidentally, the street in Manila named after Morayta (Nicanor Reyes Street today) has always been affected by, if not itself the venue of, student demonstrations. In June of 1884, Rizal received the degree of Licentiate in Medicine at the age of 23. His rating though was just ‘fair’ for it was affected by the ‘low’ grades he got from UST. The next school year (1884-1885), he took and completed the three additional subjects leading to the Doctor of Medicine degree. He was not awarded the Doctor’s diploma though for failing to pay the fee and the required thesis. Exactly on his 24th birthday, the Madrid university awarded him the degree of Licentiate in Philosophy and Letters with the grade of excellent (‘sobresaliente’). We can thus argue that Rizal was better as a ‘philosopher’ than a physician. Wanting to cure his mother's advancing blindness, Rizal went to Paris. He was said to have attended medical lectures at the University of Paris. From November 1885 to February 1886, he worked as an assistant to Dr. Louis de Weckert. Through this leading French ophthalmologist, Rizal was thankful that he learned how to perform all the ophthalmological operations. In February 3, 1886, Rizal arrived in Heidelberg, Germany. He attended the lectures of Dr. Otto Becker and Prof. Wilhelm Kuehne at the University of Heidelberg. He also worked at the University Eye Hospital under the guidance of 58 Dr. Becker. Under the direction of this renowned German ophthalmologist, Rizal had learned to use the then newly invented ophthalmoscope (invented by Hermann von Helmholtz) which he later used to operate on his mother’s eye. In Heidelberg, the 25-year-old Rizal completed his eye specialization. Afterward, Rizal spent three months in the nearby village, Wilhemsfeld where he wrote the last few chapters of ‘Noli Me Tangere’. He stayed at the pastoral house of a kind Protestant pastor, Dr. Karl Ullmer, the whole family of whom became Rizal’s good friends. In August 1886, he attended lectures on history and psychology at the University of Leipzig. In November 1886, he reached Berlin, the famous city where he worked as an assistant in Dr. Schweigger’s clinic and attended lectures in the University of Berlin. In Berlin, he was inducted as a member of the Berlin’s ‘Ethnological Society’, ‘Anthropological Society’, and ‘Geographical Society’. In April 1887, he was invited to deliver an address in German before the ‘Ethnographic Society’ of Berlin on the orthography and structure of the Tagalog language. In Germany, Rizal met and befriended the famous academicians and scholars at the time. Among them were Prof. Friedrich Ratzel, German historian; Dr. Hanz Meyer, German Anthropologist; Dr. Feodor Jagor, the author of ‘Travels in the Philippines’ which Rizal had read as a student in Manila; Dr. Rudolf Virchow, German anthropologist; and Rudolf’s son, Dr. Hans Virchow, Descriptive Anatomy professor. Especially after the hero’s martyrdom, these people who were the renowned personalities in the academe not only in Germany but also in Europe were so proud that once in their life they had known the educated and great Filipino named Jose Rizal. 59 JOSE RIZAL’S LOVELIFE 60 SEGUNDA KATIGBAK: JOSE RIZAL’S FIRST LOVE She was Jose Rizal’s “puppy love” and with her the hero was believed to have had “love at first sight”. Rizal was 16 years old when one Sunday in 1887 he paid visit to his maternal grandmother in Trozo, Manila and there met, among others, Segunda Katigbak, a two-yearyounger-than-him ‘colegiala’. In his ‘Memorias de Un Estudiante de Manila’, Rizal graphically described her as a short lady with “eloquent eyes, rosy cheeks, and smile that reveals very beautiful teeth”. Mariano Katigbak, Segunda’s brother and Rizal’s classmate who was also in the house, probably had no idea that his friend had been experiencing “a love at first sight” being bewitched by his alluring sister. During the 1880s, the Katigbaks of Batangas were known for their successful and very lucrative coffee industry. When Jose met Segunda, she was at the time a boarding student of La Concordia College where Rizal’s sister Olympia was also studying. Jose and Segunda got to know each other more intimately as his visits to his sister Olympia (or rather to his love interest Segunda) in La Concordia surprisingly became more frequent. How could Rizal forget that incident when he was urged by other acquaintances and conformed to make a pencil sketch of Segunda? “From time to time”, he later recorded in his diary, “she looked at me, and I blushed.” When Segunda one day gave him a white artificial rose, she had made herself at school, he gave her in exchange that pencil sketch he had drawn of her. In hindsight, we can submit that Rizal was somewhat clueless and naïve. As in the song “Paper Roses,” the artificial flower was perhaps Segunda’s way of insinuating that their affection was hopeless from the very start. The ‘rumor’ that she had been engaged to be married to a fellow-townsman, Manuel Luz, even before she met Pepe, was all along true. Rizal’s discovery of the real score later was probably his major reason, being a man of delicadeza, why he did not propose to her, more than his being ‘torpe’ or a reluctant lover. It was also at La Concordia where the young lovers talked to each other for the last time. It was a romantic day in December 1877 when the confused Rizal came to see the ever-hopeful Segunda. Rizal said goodbye because he would spend his New Year vacation in his hometown starting the following day. Segunda replied that she was also going home to Lipa a day later. She then maintained silence, perhaps giving Rizal enough opportunity to say anything romantic, especially that sweetest tri-syllabic pronouncement which a lover would want to 61 hear from a beloved. To her surprise, Rizal indeed uttered a three-syllable statement. The young Rizal said, “Well, good-bye” (which is virtually equivalent to today’s cold text message “Ah ok” plus a smiley). “Anyway—I’ll see you when you pass Calamba on your way to Lipa”, he nevertheless promised. Rizal went home to Calamba and woke up the following day determined to fulfill his promise to Segunda. The steamer carrying Segunda anchored in Biñan so Jose saddled his white horse to wait at the road. When Segunda’s carromata passed by, she smiled and waved her handkerchief to him. Initially wanting to follow, Rizal at the last minute turned his horse around and decided to ride home instead. That incident marked the end of everything between the young lovers. Segunda returned to Batangas and in due time married Don Manuel Luz y Metra who also hailed from a prominent family in Batangas. Segunda’s husband was actually the nephew of her maternal grandmother. The Luz-Katigbak ancestral house called ‘Casa de Segunda’, an old ‘bahay-na-bato’ which survived the World War II bombings, still exists today in Lipa on a street ironically named ‘Calle Rizal’. The house was restored as a vacation house and later turned into a private museum. The sportscaster Chino Trinidad, a descendant of Segunda and Manuel, once related in a TV interview that Rizal had gone to ‘Casa de Segunda”, played chess and lost to his Lolo Manuel. The historic house has been declared a National Heritage house in 1996 by the National Historical Commission. 62 LEONOR RIVERA: JOSE RIZAL'S TRUE LOVE ON TOP OF BEING DUBBED as Jose Rizal’s “childhood sweetheart,” “betrothed,” and “lover by correspondence,” she was widely considered as the hero’s “true love”. Leonor Rivera (April 11, 1867 – August 28, 1893) of Camiling, Tarlac was the daughter of Antonio Rivera and Silvestra Bauzon. Leonor’s father—who was one of the few persons who conspired in Jose’s ‘secret’ departure to Spain—is a cousin of the hero’s father, Francisco Mercado. Subjectively considered as a pretty lady, Leonor is commonly described as having wavy soft hair, high forehead, wistful almond eyes, small and pensive mouth, and charming dimples. She was said to be intelligent and talented, as she could play the harp and the piano—skills which matched her fascinating singing voice. Leonor was a “tender as a budding flower” colegiala at the La Concordia College when she became romantically involved, though secretly, with her distant relative Rizal. Though both Leonor Rivera and Segunda Katigbak (Rizal’s first love) studied in the same school, they probably had not met and known each other (much less pulled each other’s hair) as the Tarlaqueña was four years younger than the Batangueña. Rizal was just a young high school student in Ateneo when he was ‘dating’ Segunda. When he boarded at his Uncle Antonio’s boarding house in Intramuros and became the boyfriend of the landlord’s daughter, Rizal was already a second-year medical student then at the UST. Secret as the romance was to Leonor’s parents, she used pen names in her letters to Jose. She hid from the signatures ‘La Cuestion del Oriente’ and ‘Taimis/Tamis’. Records aren’t clear on what Jose used in return. (Some students jokingly guess that he used pseudonyms like ‘Pinsan’, or ‘Kuya Pepe’, or ‘Ang inyong boarder’. The funniest suggestion so far is: “Ang pamangkin ng iyong ama, a.k.a The Calamba boy.”) In one of Indios’ street brawls against young Spaniards in Escolta, Rizal was wounded on the head. Bleeding and filthy, he was brought home by friends to his boarding house. With tender love and care, Leonor nursed him. His wound was gently washed and carefully dressed, though the band-aid used was unnamed. All Leonor ever wanted was to be on Jose’s side each time, to look for him, and take care of him. But this became far from possible when Jose left for Spain in May 1882 without giving her a notice, fearing that she—being young and not that 63 cautious yet—could not keep a secret. The ‘farewell poem’ he left for her had not washed away the sorrow she felt when she learned of her boyfriend’s departure. Seriously affected by Rizal’s departure, Leonor had become often unwell because of insomnia. While busy studying and fighting for a cause abroad, Rizal nonetheless took time to write to his sweetheart. Numerous multi-lingual (Filipino, English, Spanish, and French) love letters were exchanged between the lovers. Rizal was puzzled though as time came when Leonor became silent. To probe into why Leonor was not answering his letters was one of the reasons Rizal went home in August 1887, notwithstanding the dangers he could face in such a decision. When he returned though, Leonor was no longer in Manila for her family had transferred to Dagupan, Pangasinan where her parents had a clothing merchandise business. The couple wanted to see each other but both were prohibited by their respective parents. Don Francisco Mercado believed that the meeting would put the Rivera family in danger for the author of the Noli at the time was already branded by the Spaniards as a ‘filibustero’ (subversive). Before his second departure from the country in 1882, Rizal wanted to marry the uncomplaining Leonor and leave her in his sister Narcisa’s care. Don Francisco however consistently disapproved of Jose’s plan. Paciano also thought that it was selfish of his brother to marry Leonor only to leave her behind. In foreign lands, Rizal kept on sending letters to Leonor but received no reply. The lovers had no idea that Doña Silvestra—who understandably did not like the controversial Filipino for a son-in-law—had been hiding from Leonor all the letters sent her by Rizal. It was said that Mrs. Rivera bribed two post office officials to give her all of Jose’s letters and gifts for her daughter. The mother convinced Leonor to marry Charles Henry Kipping, an English railway engineer who was responsible for the completion of the railroad from Bayambang to the ‘Ferrocarril de Manila’ (railroad from Manila-Dagupan). Mrs. Rivera and Kipping were said to have connived in making Leonor believe that Jose had already fallen in love with other women in Europe. Leonor desolately consented to marry her mother’s choice on supposed conditions that she would never play the piano again, all her and Jose’s letters to each other which had been gathered be burned and the ashes be deposited in her jewelry box, and that her mother stand beside her at her wedding. The marriage ceremony happened two days before Rizal’s birthday in 1891. Six months before the ceremony, Rizal had received a letter announcing this imminent Kipping-Rivera wedding. The letter was from his true love herself who 64 was also asking for his forgiveness. Rizal described the news as a great blow to him as he was “stunned, his eyes dimmed with tears, and his heart broke.” The mail signaled the death of Rizal’s 11-year love affair with Leonor. After two years of her married life, Leonor died on August 28, 1893 from complications of childbirth, while Jose was serving his term as an exile in Dapitan. Rizal’s mourning heart was injured even more upon learning that “Leonor had asked to be buried in the saya (native skirt) she was wearing when he and she had first come to an ‘understanding.’ She had also asked for the silver cup which held the ashes of the few letters from him which had reached her” (Bantug, p. 115). While walking toward the place of his execution on December 30, 1896, Rizal turned towards the sea and was said to have uttered, “What a beautiful morning! On mornings like this, I used to take walks here with my sweetheart” (Ocampo, p. 228). By the term “sweetheart”, Rizal was most likely referring to Leonor Rivera. On the record therefore, she was the girlfriend last mentioned by the hero before he died. In fact, Rizal was said to have “kept a lock of Leonor’s hair and some of her letters until his death” (Bantug, p. 115). Rizal had a crayon sketch of Leonor which was preserved, the image of which can now be searched and viewed over the internet. On top of this, Rizal immortalized his true love by basing from her the character of ‘Maria Clara’ in his Noli and Fili. As a postscript, Kipping and Rivera had a child named Carlos Rivera Kipping (who later became Carlos Rivera Kipping, Sr.) who married Lourdes Romulo, a sister of the former United Nation official and Boy Scouts of the Philippines co-founder Carlos P. Romulo. The descendants of the Kipping family donated to the Yuchengco Museum in Makati City the box which housed the ashes of burned Rizal’s letters to Leonor. The box was covered with Leonor’s dress with the letters “J” and “L” embroidered on it. 65 LEONOR VALENZUELA AND JOSE RIZAL'S INVISIBLE LOVE LETTERS Nicknamed Orang, Leonor Valenzuela was commonly described as a tall girl with regal bearing who was Rizal’s province-mate. She was the daughter of Capitan Juan and Capitana Sanday Valenzuela, who were from Pagsanjan, Laguna. Orang was Rizal’s neighbor when he boarded in the house of Doña Concha Leyva in Intramuros during his sophomore year at the University of Santo Tomas as medicine student. To finally move on perhaps from his unsuccessful love story with Segunda Katigbak, Rizal frequently visited Orang’s house with or without social gatherings. The proofs that Rizal indeed courted her were the love letters he sent her. His love notes were mysteriously written in invisible ink made of common table salt and water, which could be read by heating the note over a candle or lamp. More than a manifestation of Rizal’s knowledge of chemistry, his magical love notes to Orang, one can say, are a proof that he wanted to keep the courtship private. But why would he want to make it secret? Many references declare that Orang was Rizal’s object of affection (too) while he was courting the other Leonor, his cousin Leonor Rivera. If this were true, then sending invisible love letters would indeed be the smart thing to do for other people would find them as mere blank papers. Without clear material evidence, the ‘two-timer charge’ could indeed be easily denied. (To do a further speculative stretch, Rizal was perhaps thinking that if both ladies would become his girlfriends, he would not make the mistake of calling any of them by a wrong name.) When Rizal left for Spain, he received a letter from his friend and confidant Jose M. Cecilio (Chenggoy) indicating that the two ladies had an idea that their ‘common denominator’ was not only their first name: “…nagpipilit ang munting kasera (Leonor Rivera) na makita si Orang, pero dahil natatakpan ng isang belong puti, hindi naming nakilala nang dumaan ang prusisyon sa tapat ng bahay. Sinabi sa akin ni O(rang) na sabihin ko raw sa munting kasera na hindi siya kumakaribal sa pag-iibigan ninyo. Que gulay, tukayo, anong gulo itong idinudulot natin sa mga dalagang ito!” The letter suggests that either Orang was giving way to Rivera-Rizal love affair or she (Orang) was not that interested in Rizal. In fact, records were not clear if she officially reciprocated Rizal’s courtship. If indeed she never took Rizal’s 66 courtship seriously, we could not actually blame her. Her would-be affair with Rizal could only be either a rebound relationship (from Segunda-Jose failed affair) or an unhealthy love triangle (with the other Leonor in the equation). Unlike her ‘tukayo’, Orang didn’t feel much sorrow upon Rizal’s departure. She was said to have accepted other suitors, attended social parties, and ended up marrying an employee of a trade house. 67 CONSUELO ORTIGA Y REY: THE "CRUSH NG BAYAN" IN RIZAL'S TIME She was probably very likable because at least two Filipinos in Spain in Jose Rizal’s time had had feelings for her. Consuelo Ortiga y Rey was considered the prettier of the daughters of Don Pablo Ortiga y Rey, the Spanish liberal and former mayor of Manila who became vicepresident of the Council of the Philippines in the Ministry of Colonies. Very supportive to the Filipinos in Madrid, Don Pablo’s house was the common meeting place of ‘Circulo Hispano-Filipino’ members like Rizal. The Ortiga residence was thus frequented by Filipino lads especially that Don Pablo had beautiful daughters. Consuelo recorded in her diary that she first met Rizal on September 16, 1882 when he went to Spain for the first time primarily to study. The diary entry indicated that they talked the whole night and that the young Filipino said many beautiful things about her. The Spanish ladyalso wrote of a day Rizal spent at their house when he entertained them with his ingenious humor, elegance, and sleightof-hand tricks. Most likely, Consuelo had witnessed Rizal’s recitation of a poem on October 4, 1882 in the effort to save a Filipino meeting from disintegration. Rizal had also recorded either in his diary or letters that he attended another meeting of compatriots in Ortiga’s residence on October 7, 1882 and the birthday party of Consuelo’s father on January 15, 1883. The following year (1884), Rizal and other compatriots attended (again) the birthday party of Don Pablo in which there was a dance. It was not clear if Rizal had a dance with Consuelo but five days after, he sent her a piece of guimaras cloth. Rizal recorded that he again went to see Consuelo on February 10 after doing something at the university district. On March 15, Rizal and other compatriots—including Eduardo de Lete—were again gathered in the Ortiga house. Lete was actually one of the reasons Rizal gave up his affection for Consuelo. Lete seriously liked Ms. Ortiga and Rizal did not wish to ruin their friendship over a lady. It was said that even Maximino and Antonio Paterno, Rizal’s good friends, regularly visited the lady. (Thus, we can submit that Consuelo was the “crush ng bayan” among Filipinos in Madrid in Rizal’s time). It can be remembered that Eduardo de Lete (the ‘karibal’) was one of the Filipinos who promised Rizal of helping in the writing of a nationalistic novel but ended up contributing nothing—for they, according to Rizal, were more interested to write on women and would rather spend their time gambling or flirting with Spanish women. It was not clear if Lete and Consuelo ‘became an item’ but this Lete—whom Rizal considered in suppressing his feelings for Consuelo—later attacked the hero through an article in ‘La Solidaridad’ on April 68 15, 1892 depicting Rizal as coward, egoistic, opportunistic, and someone who had abandoned the country’s cause. Officially therefore, this Lete had hurt the hero’s feeling not just once but at least twice. Rizal’s admiration for Consuelo was immortalized by the poem he wrote, ‘A La Señorita C.O. y R’. This poem which is now subjectively regarded as one of Rizal’s best was written either as a reaction to Consuelo’s request or out of Rizal’s pure volition as an admirer. Ultimately though, Rizal really had to give up his feeling for Consuelo for he was then still engaged to Leonor Rivera. 69 SEIKO USUI: JOSE RIZAL'S JAPANESE GIRLFRIEND If only Jose Rizal had no patriotic mission and no political will, he would have married her and settled in Japan for good. It was during Rizal’s second trip abroad when he met Seiko Usui. From Hong Kong, he arrived in Japan in February 1888 and moved to the Spanish Legation in the Azabu district of Tokyo upon the invitation of an official in the legation. One day, Rizal saw Seiko passing by the legation in one of her daily afternoon walks. Fascinated by her charm, Rizal inquired and learned from a Japanese gardener some basic information about her. The next day, Rizal and the Japanese gardener waited at the legation gate for Seiko. Acting as a go-between and interpreter, the gardener introduced the gracious Filipino doctor and the pretty Japanese woman to each other. The gardener’s role as intermediary was cut short however when Seiko spoke in English. She also knew French, and so she and Rizal began to converse in both languages. O-Sei-San, as Rizal fondly called Seiko, voluntarily acted as Rizal’s generous tour guide. She accompanied him to Japan’s shrines, parks, universities, and other interesting places like the Imperial Art Gallery, Imperial Library, and the Shokubutsu-en (Botanical Garden). Serving as his tutor and interpreter, she helped him improve his knowledge of the Japanese language (Nihonngo) and explained to him some Japanese cultural elements and traditions like the Kabuki plays. It was thus not surprising that Jose fell for the charming, modest, pretty, and intelligent daughter of a samurai. Seiko subsequently reciprocated the affection of the talented and virtuous guest who, like her, had deep interest in the arts. Their more than a month happy relationship had to end nonetheless, as the man with a mission Rizal had to leave Japan. His diary entry on the eve of his departure illustrates what he had thrown away in deciding to leave O-Sei-San: “Japan has enchanted me. The beautiful scenery, the flowers, the trees, and the inhabitants – so peaceful, so courteous, and so pleasant. O-Sei-San, Sayonara, Sayonara! I have spent a happy golden month; I do not know if I can have another one like that in all my life. Love, money, friendship, appreciation, honors –these have not been wanting. 70 To think that I am leaving this life for the uncertain, the unknown. There I was offered an easy way to live, beloved and esteemed…” As if talking to Seiko, Rizal affectionately addressed this part of his diary entry to his Japanese sweetheart: “To you I dedicate the final chapter of these memoirs of my youth. No woman, like you has ever loved me. No woman, like you has ever sacrificed for me. Like the flower of the chodji that falls from the stem fresh and whole without falling leaves or without withering –with poetry still despite its fall – thus you fell. Neither have you lost your purity nor have the delicate petals of your innocence faded – Sayonara, Sayonara! You shall never return to know that I have once more thought of you and that your image lives in my memory; and undoubtedly, I am always thinking of you. Your name lives in the sight of my lips, your image accompanies and animates all my thoughts. When shall I return to pass another divine afternoon like that in the temple of Maguro? When shall the sweet hours I spent with you return? When shall I find them sweeter, more tranquil, more pleasing? You the color of the camellia, its freshness, its elegance… Ah! Last descendant of a noble family, faithful to an unfortunate vengeance, you are lovely like…everything has ended! Sayonara, Sayonara!” Onboard the steamer ‘Belgic’, Rizal left Japan on April 13, 1888 never to see Seiko again. In 1897, a year after Rizal’s martyrdom, Seiko married Alfred Charlton, British chemistry teacher of the Peer’s School in Tokyo. Mr. Charlton died on November 2, 1915, survived by Seiko and their child Yuriko. At the age of 80, Seiko died on May 1, 1947 and was buried in the tomb of her husband at Zoshigawa Cemetery. Their daughter Yuriko became the wife of a certain Yoshiharu Takiguchi, son of a Japanese senator. 71 GERTRUDE BECKETT: JOSE RIZAL'S FLING IN LONDON SHE HELPED JOSE RIZAL mix his colors for painting and prepared the clay for his sculpturing, hoping that a colorful romantic relationship would be formed between them. Gertrude was the daughter of Rizal’s landlord— Charles Beckett who is an organist at St. Paul’s Church in London. Coming from brief stay in Japan and the United States of America, Rizal chose to live in the capital city of the United Kingdom on May, 1888. The oldest of the ‘three’ (some say ‘four’) Beckett sisters, Gertrude (also called ‘Gettie’ or ‘Tottie’) was a curvy lady with cheerful blue eyes, brown hair, rosy cheeks, and thin lips. (Based on the pictures of Rizal’s ‘girlfriends’ now available over the internet, one can even argue that Gertrude is the most beautiful.) This English girl (who probably spoke the British accent of the ‘Harry Potter’ characters) fell in love with Rizal. The more-than-normal assistance she gave to the Filipino boarder betrayed her special feelings for him. She showered him with all her attention and assisted him in his painting and sculpturing. With her aid, Rizal finished some sculptural works like the ‘Prometheus Bound’, ‘The Triumph of Death over Life,’ and ‘The Triumph of Science over Death.’ Away from his home, it was just normal for Rizal to find enjoyment in Gertrude’s loving service. Rizal called her by her nickname “Gettie” and she affectionately called him “Pettie.” It was said that their friendship glided towards romance, but Rizal, for some reasons, was alleged to have ultimately backed out. Some sources nonetheless suggest that their relationship was just a one-sided love affair as Rizal never really reciprocated her love. Either way, it was clear that the couple did not end up as husband and wife as Rizal chose to leave London on March 19, 1889 so that Gertrude may forget him. As Rizals compatriots like Marcelo del Pilar put it, Rizal left London because he was running away from a girl. Before leaving though, he finished his composite carving of the heads of the Beckett sisters and gave it to Gettie as a souvenir. 72 SUZANNE JACOBY: JOSE RIZAL'S FLING When Jose Rizal left her place, her dream was to follow him and to travel with the Filipino lover boy who was always in her thoughts. Suzanne Jacoby was a Belgian lady whom Rizal met when he was 29. To somewhat economize in his living expenses, he left the expensive city of Paris and went to Belgium in January 1890. Along with his friend Jose Albert, Rizal arrived in Brussels on February 2 and stayed in the boarding house managed by two Jacoby sisters, Suzanne and Marie (some references say “Catherina and Suzanna”). It was said that Rizal had a transitory romance with the petite niece of his landladies, Suzanne. In Rizal’s 6-month stay in the boarding house, Suzanne, also called ‘Petite,’ got to know and was attracted to the skillful and enigmatic Filipino doctor. Jose might have had a somewhat romantic intimacy with Petite—a relationship which was probably comparable to today’s ‘mutual understanding’ (like what Rizal possibly had with Gertrude Beckett). Presumably, Petite and Jose (who was at one time called ‘Pettie” by Beckett) had together enjoyed the merriments of Belgium’s summertime festival of 1890 with its multicolored costumes, animated floats, and lively crowds. But the relationship was most likely not that serious as Rizal did not mention her in his letters to his intimate friends. Informing Antonio Luna of his life in Brussels, Rizal just talked about going to the clinic, working and studying, reading and writing, and practicing at the ‘Sala de Armas’ and gymnasium. Historically, his affair with Suzanne could not possibly blossom as Rizal, that time, was busy writing the ‘Fili’, contributing for La Solidaridad, and worrying for his family as regards the worsening Calamba agrarian trouble. Suzanne shed tears when Rizal left Belgium toward the beginning of August, 1890. He was said to have made Suzanne’s sculpture which he unexplainably gave to his friend Valentin Ventura. Leaving Brussels, Rizal left the young Suzanne a box of chocolates. Two months later, she wrote him a letter, saying: “After your departure, I did not take the chocolate. The box is still intact as on the day of your parting. Don’t delay too long writing us because I wear out the soles of my shoes for running to the mailbox to see if there is a letter from you. There will never be any home in which you are so loved as in that in Brussels, so, you little bad boy, hurry up and come back…” 73 In her another letter, she was mentioning of Rizal’s letter to her, suggesting that the Filipino in Madrid probably replied to her at least once. From her letter though, we can glean that the affection was (already) one-sided: “Where are you now? Do you think of me once in a while? I am reminded of our tender conversations, reading your letter, although it is cold and indifferent. Here in your letter I have something which makes up for your absence. How pleased I would be to follow you, to travel with you who are always in my thoughts. You wish me all kinds of luck, but forget that in the absence of a beloved one a tender heart cannot feel happy. A thousand things serve to distract your mind, my friend; but in my case, I am sad, lonely, always alone with my thoughts – nothing, absolutely nothing relieves my sorrow. Are you coming back? That’s what I want and desire most ardently – you cannot refuse me. I do not despair and I limit myself to murmuring against time which runs so fast when it carries us toward a separation but goes so slowly when it’s bringing us together again. I feel very unhappy thinking that perhaps I might never see you again. Goodbye! You know with one word you can make me very happy. Aren’t you going to write to me? To her surprise, Rizal returned to Brussels by the middle of April 1891 and stayed again in the Jacoby’s boarding house. Rizal’s return however was not specifically for Suzanne for the hero just busied himself revising and finalizing the manuscript of El Fili for publication. On July 5, 1891, Rizal bade goodbye to Brussels and Suzanne, never to come back again in Belgium and in her arms. Lately, a certain Belgian named Pros Slachmuylders claimed that Rizal had romance with his landladies’ niece named Suzanna Thill, not with Suzanne Jacoby. Thill was said to be 16 years old when Rizal was in Belgium in 1890. One hundred and seventeen (117) years after Rizal left Belgium, Slachmuylders’ group unveiled in 2007 a historical marker which commemorates Rizal’s stay in Brussels. 74 NELLIE BOUSTEAD: JOSE RIZAL'S ALMOST WIFE Perceiving Jose Rizal’s imminent courtship to her, his compatriot Marcelo H. del Pilar teased the lover boy by suggesting that his first novel should be renamed ‘Nelly Me Tangere’. Nellie Boustead, also called Nelly, was the younger of the two pretty daughters of the wealthy businessman Eduardo Boustead, son of a rich British trader, who went to the Orient in 1826. The Bousteads hosted Rizal’s stay in Biarritz in February 1891 at their winter residence, Villa Eliada on the superb French Riviera. Rizal had befriended the family back in 1889-90 and used to fence with the Anglo-Filipino Boustead sisters (Adelina and Nellie) at the studio of Juan Luna. Having learned Leonor Rivera’s marriage to Henry Kipping, Rizal entertained the idea of having romantic relation with the highly educated, cheerful, athletic, beautiful, and morally upright Nellie. He wrote some of his friends (though remarkably except Ferdinand Blumentritt) about his affection for Nelly and his idea of proposing marriage to her. His friends seemed to be supportive of his intentions. Tomas Arejola, for instance, wrote him: “… if Mademoiselle Boustead suits you, court her, and marry her, and we are here to applaud such a good act.” (Zaide, p. 184). Even Antonio Luna, who had been Nelly’s fiancé, explicitly permitted Rizal to court and marry her. It could be remembered that Jose and Antonio nearly had a deadly duel before when he (Antonio), being drunk one time, made negative remarks on their ‘common denominator’. As regards Jose’s courtship to Nelly later, Antonio gentlemanly conceded to Rizal through a letter: “With respect to Nelly, frankly, I think there is nothing between us more than one of those friendships enlivened by being fellow countrymen. It seems to me that there is nothing more. My word of honor. I had been her fiancé, we wrote to each other. I like her because I knew how worthy she was, but circumstances beyond our control made all that happiness one cherished evaporate. She is good; she is naturally endowed with qualities 75 admirable in a young woman and I believe that she will bring happiness not only to you but to any other man who is worthy of her…I congratulate you as one congratulates a friend. Congratulatons!” (as quoted by Zaide, pp. 184-185) As Nelly had long been infatuated to Rizal, she reciprocated his affection and they officially became an item. With Nelly, Rizal enjoyed his stay in Biarritz as he had many lovely moonlight nights with her. Inspired by her company, Rizal was also able to work on the last part of his second novel at the Bousted’s residence. Though very much ideal, Nelly-and-Jose’s lovely relationship unfortunately did not end up in marriage. Nelly’s mother—a Filipina who came from the rich Genato family in Manila—was not in favor of taking as a son-in-law a man who could not provide a sure stable future for her daughter. On top of this, Rizal refused to be converted in Protestantism which Nellie demanded. Later in his life, Rizal would state in his letter, “… had I held religion as a matter of convenience or an art getting along in this life … I would now be a rich man, free, and covered with honors.” (Zaide, p. 185) The breakup between the very civil and educated couple was far from bitter as the two parted as friends. When Rizal was about to leave Europe in April 1891, Nelly sent him a goodbye letter, saying: “Now that you are leaving I wish you a happy trip and may you triumph in your undertakings, and above all, may the Lord look down on you with favor and guide your way giving you much blessings, and may your learn to enjoy! My remembrance will accompany you as also my prayers.” 76 JOSEPHINE BRACKEN: JOSE RIZAL'S DEAR AND UNHAPPY WIFE IN JOSE RIZAL’S OWN WORDS, she was his dear wife. A few hours before his execution, they embraced for the last time and he gave her a souvenir—a religious book with his dedication, “To my dear unhappy wife, Josephine.” EARLY LIFE Marie Josephine Leopoldine Bracken was born on August 9, 1876 in Victoria, Hong Kong. She was the youngest of the five children of an Irish couple who were married on May 3, 1868 in Belfast, Ireland: British army corporal James Bracken and Elizabeth Jane MacBride. A few days after giving birth to Josephine, her mother Elizabeth died. Her father decided to give her up for adoption to her childless godparents, American George Taufer, an engineer of the pumping plant of the Hong Kong Fire Department, and his Portuguese (second) wife. Josephine’s real father (James) left Hong Kong after retirement and was said to have died at the hands of robbers in Australia. When Josephine was 7, her godmother—whose name Leopoldine was added to her own—also died. In 1891, her foster father remarried another Portuguese lady from Macau, Francesca Spencer. Because Josephine could not get along with Taufer’s new wife, she (Josephine) ran away and sought shelter in a boarding house run by nuns. After two months, either she was taken back or she voluntarily returned home. MEETING IN DAPITAN Josephine and Taufer first met Rizal in Hongkong, when they consulted the Filipino doctor for Taufer’s failing eyesight. In 1895, the Taufer family sailed to the Philippines to seek treatment from Rizal for Taufer’s cataract. They arrived in Manila on February 5, and later that month, Josephine, George, and a certain Manuela Orlac, the mistress of a friar at the Manila Cathedral (Bantug. p. 117), sailed to Dapitan where Rizal had been living as a political exile for three years. The petite Josephine who had blue eyes and brown hair was 18 years old at the time of their arrival in Dapitan. Josephine was said to be not a remarkable beauty, but she “had an agreeable countenance because of the childlike expression of her face, her profound blue and dreamy eyes and abundant hair of brilliant gold” (Alburo). It is thus said that the lonely Rizal was attracted to Josephine who was a happy character despite having lived a difficult life with her adoptive father and his various wives. Unsurprisingly, the two easily fell in love with each other. 77 TAUFER’S OPPOSITION Rizal worked on Taufer’s eyes but later told the patient that the illness was incurable. It is supposed that it was this news, plus Josephine’s wish to stay with Rizal and “the marriage in Manila of a daughter by his first wife” (Alburo) which led the distressed Taufer to slash his wrist (some say ‘throat’)—an attempt which Rizal and Josephine had fortunately averted. Taufer’s supposed furious jealousy and strong opposition to the couple’s union caused Josephine to accompany him as they left for Manila on March 14, 1895, together with Rizal’s sister, Narcisa. Josephine nonetheless carried a letter from Rizal recommending her to Doña Teodora: The bearer of this letter is Miss Josephine Leopoldine Taufer whom I was at the point of marrying, counting on your consent, of course. Our relations were broken at her suggestion, on account of the numerous difficulties in the way. She is almost alone in the world; she has only very distant relatives. As I am interested in her and it is very possible that she may later decide to join me and as she may be left all alone and abandoned, I beg you to give her hospitality there, treating her as a daughter, until she shall have an opportunity or occasion to come here. I have decided to write the general about my case. Treat Miss Josephine as a person I esteem and value much and whom I would not like to be unprotected and abandoned. When Taufer left for Hong Kong, it was with Narcisa that Josephine stayed. The rest of Rizal’s family was suspicious that Josephine had been working as a spy for the Spanish friars. MARRYING JOSEPHINE Some references claim that even before Taufer and Josephine left for Manila, Rizal had already proposed to her and applied for their marriage. Dapitan parish priest Antonio Obach however wanted Rizal’s retraction of his anti-clerical views as a prerequisite and would only grant the church ceremony if Rizal could get permission from the Bishop of Cebu. “Either the Bishop did not write him back or Rizal was not able to mail the letter because of the sudden departure of Mr. Taufer” (Wikipedia). When Josephine returned to Dapitan, the church wedding she hoped for could not happen. Rizal would not retract and so Obach denied them the permission to marry, and “the Bishop of Cebu confirmed the priest’s decision” (Bantug, p. 118). 78 With Josephine’s consent, Rizal nonetheless took her as his wife even without the Catholic blessings. The couple married themselves before the eyes of God by “holding hands in the presence of two witnesses” (Alburo). Aware of the circumstances, Doña Teodora told her excommunicated son that loving each other in God’s grace was better than being married in mortal sin (Bantug, p. 120). These words somewhat gave Rizal a peace of mind. But still believing that his live-in relationship was somewhat of a shame, Rizal never told his friend and confidant Blumentritt about it. JOSEPHINE AS RIZAL’S WIFE Depending on the reference one is using, Rizal and Josephine lived together either in Rizal’s ‘casa cuadrada’ or octagonal bamboo house. In his letters to his family, Rizal related that Josephine “turned the house into a love nest, stocking the pantry with preserves and pickles” (Alburo). To prove the depiction, the letters were accompanied by packages of food “prepared by the woman who lives in my house” (Alburo). Josephine kept house and took good care of “Joe,” her nickname for Rizal. She “cooked, washed, sewed, and fed the chickens. She learned to make suman (a sticky rice dessert wrapped in banana leaves), bagoong, noodles, and bread. With the Spanish she learned from Rizal, she could write a simple letter. His [Rizal] nephews called her ‘Auntie’” (Bantug, p. 120). To his mother, Rizal described Josephine as “good, obedient, and submissive … We have still to have our first quarrel, and when I reprove her, she does not talk back.” RIZAL’S SON Before the year ended in 1895, the couple had a child who was born prematurely. “Rizal’s sisters say the boy was named Peter; others say he was named Francisco, after Don Francisco Mercado” (Bantug, p. 121). Unfortunately, the son died a few hours after birth. Rizal was said to have “made a pencil sketch of the dead infant on the jacket of a medical book. He then buried the baby in an unmarked grave in a secluded part of Talisay” (Bantug, p. 121). Filipino historian Gregorio Zaide narrated that Rizal played a prank on Josephine which frightened her so that she untimely gave birth to an eight-month baby (Zaide, p. 240). But doubting the veracity of this tale, some intriguingly ask questions like: Was the miscarriage due to a fall down from the stairs? Did Rizal push her during one of their quarrels? Or, did they quarrel intensely at all? 79 Some sources declare that the two had quarrels, “one of which, according to a 1966 article in the Free Press, was violent, leading to her [Bracken’s] miscarriage. The same article, written by L. Rebomantan, suggests that Rizal’s days of consolation with Josephine were [soon] over and that his request for assignment to Cuba was also prompted by his unhappiness with her.” (Alburo) LEAVING DAPITAN On July 30, 1896, Rizal received a letter from the governor general sanctioning his petition to serve as volunteer physician in Cuba. In the late afternoon of July 31, Rizal and Josephine got on the ‘España’ along with Narcisa, a niece, three nephews, and three of his students. The steamer departed at midnight of July 31 and arrived in Manila on August 6. While Rizal was being kept under arrest aboard the cruiser ‘Castilla’ docked at Cavite, Josephine stayed in Narcisa’s home in Manila. While waiting for Jose’s fate, she “filled her time with tutoring in English and taking piano lessons from one of her 15 pupils” (Alburo). GOODBYE JOSE When Rizal was tried on the morning of December 26, 1896, Josephine was said to be among the spectators inside the military building, Cuartel de España, along with some newspapermen and many Spaniards (Zaide & Zaide, p. 259). At about 6 p.m. on the day before Rizal’s execution, Josephine Bracken arrived in Fort Santiago. Rizal called for her and they emotionally talked to each other. Though some accounts state that Josephine was forbidden from seeing her husband on the fateful day of his martyrdom, the historian Gregorio Zaide wrote that at 5:30 a.m., she and Josefa (Rizal’s sister) came. The couple was said to have embraced for the last time and Rizal gave to Josephine the book ‘Imitation of Christ’ (by Thomas a Kempis) on which he lovingly wrote: “To my dear and unhappy wife, Josephine/ December 30th, 1896/ Jose Rizal”. There’s an allegation that either the evening before or in the early morning of Rizal’s day of execution, the couple was married in a ceremony officiated by the priest Vicente Balanguer. Nonetheless, the members of Rizal family themselves seriously doubt the claim as no records were found as regards the wedding. JOINING THE KATIPUNAN Three days after Rizal’s martyrdom, Josephine hurriedly joined the Katipunan’s forces in Cavite. As Rizal’s widow, she could have easily penetrated the revolutionary group but it was said that “Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo was reluctantly persuaded to admit Josephine into the military ranks, providing her with lessons in shooting and horseback riding” (Alburo). Aside from serving as an inspiration to the Katipuneros (being Rizal’s wife), she assisted in operating the 80 reloading of jigs for Mauser cartridges at the Imus arsenal under revolutionary General Pantaleón Garcia” (Wikipedia). She also helped in taking care of the sick and wounded. In fact, “it was her suggestion to start a field hospital in the casa hacienda of Tejeros” (Alburo). When Imus became under threat of recapture, Bracken made her way through bushes and mud to the forces in Maragondon where she witnessed the Tejeros Convention on March 22, 1897. When the enemies captured San Francisco de Malabon, “Josephine, accompanied by her brother-in-law Gen. Paciano Rizal, left for Bay, Laguna, passing through forests and over mountains, many times barefoot and riding on a carabao” (Alburo). While in Bay, Josephine was summoned by the Spanish governor general, Camilo Polavieja. She was given the options of leaving the country or be subjected to torture and imprisonment. Owing however to Mr. Taufer’s American citizenship, she could not be compulsorily banished, though Josephine eventually left for Hong Kong in May 1897 “upon the advice of the American consul in Manila” (Wikipedia). JOSEPHINE’S SECOND HUSBAND Upon returning to Hong Kong, Josephine went back to Taufer’s house. She petitioned for her share of Rizal’s library in Hong Kong, which was under the guardianship of Jose Maria Basa. Though sympathetic to her, Basa could not grant her request because the Rizals, especially Doña Teodora, were contesting the petition and Josephine had no proof that she was legally married to Jose. After her foster father’s death, she married the Philippine-born mestizo Vicente Abad y Recio from Cebu. Some sources introduce Bracken’s second husband as the son of a Hong Kong tabacalera company owner whereas others present him as one of the employees of Tabacalera. It was said that Hong Kong-based Julio Llorente, a Cebuano friend of Rizal, introduced Abad to Bracken. Llorente was also the one who wrote the letter of introduction to Rizal carried by Josephine and Taufer when they arrived in Dapitan in 1895.Llorente must have referred his co-Cebuano Abad to Josephine to be her student in English. As a businessman in Hong Kong, Abad had to learn English. Having been to the Philippines and knowing Spanish, Josephine was thus an ideal tutor for him. The two fell for each other and after a short courtship got married on December 15, 1898. Some narrations state that the couple moved to the Philippines in May 1899 while others say that the family returned to Manila a year 81 after the couple’s child was born. Josephine gave birth to their daughter, Dolores, on April 17, 1900. After some months in Manila, they moved and settled in Cebu City. The place, by then, was already under the control of the Americans and Julio Llorente himself even became Cebu governor under the American rule. Abad returned to Cebu to open the first bicycle store and rental in the place, a business which was said to have blossomed. TUTORING SERGIO OSMEÑA While Abad was managing the bicycle business, Josephine was also earning in the place by using it as study center. This is proved by the advertisement placed in the newspaper ‘El Pueblo’ in April 1900, which posted: “Josephine Bracken (sic) de Abad, Profesora de Lenguas living near Plaza Rizal, is giving lessons in English and German in her residence.” Their place was on Magallanes and Burgos Streets, just a stone’s throw away from Basilica del Santo Niño and the present-day Cebu City Hall. There, Josephine had taught the young Sergio Osmeña y Suico (better known as Sergio Osmeña, Sr.) who later became the 4th President of the Philippines (1944 to 1946). Osmeña was said to have learned at least two things in the place: paddling a bike and the English language. However, Osmeña’s biographer, Vicente Albano Pacis, doubts that the first Visayan to become Philippine president learned much from Bracken (Alburo). Bracken’s little experience as English tutor in Manila and Cebu (and most probably her connection to the national hero and Llorente) made it easier for her to get a steadier occupation “as public-school teacher at the recommendation of [a certain] Dr. David Barrows” (Alburo). The poor condition of her health nonetheless precluded her to work further. To seek a cure for her tuberculosis, she returned to Hong Kong once again. DEATH AND INTERMENT The rapid advancement of Josephine’s terminal tuberculosis of the larynx took its toll on her body and also drained her family’s financial resources. She was confined in St. Francis Hospital, a Catholic charitable institution in Hong Kong. Msgr. Spada, the Vicar General in Hong Kong who visited her in the hospital, had this to say about the dying Josephine: “The last time I saw Mrs. Rizal, I was stricken with pity. She was broken down; yes, very much broken down both in health and in spirit. I deemed it my first duty to comfort her and revive her spirit, but my efforts were futile. It was a losing fight. Poor woman, she had lost all hope, and with it, her faith in humanity.” (“Final Rest”) 82 On the eve of March 14-15, 1902, Bracken restfully died in the land where she was born. Because of the contagiousness of her ailment, she was immediately buried the next day at the Happy Valley Cemetery, not too far from the grave of her mother (Grave No. 4258) in the Military Section. A small news item on page 4 of Hong Kong’s ‘China Mail’ reported that she died at “No. 87, Praya East, where she had been residing for some time”. The funeral, the news item added, was “attended by a number of prominent Filipinos.” Her husband who hastily arrived in Hong Kong was said to have witnessed the closing of his wife’s grave. Unfortunately, Vicente failed to indicate to any relative the exact location of Bracken’s tomb, as he himself died the following year, of the same disease, and buried in the same cemetery. However, the idea that Josephine was buried in a pauper’s grave in Hong Kong was fervidly refuted later by her husband’s family. The Abad family could easily afford a decent burial for Josephine, especially with her brother-in-law Jose also in Hong Kong, so argued Dolores, Vicente Abad’s daughter by Bracken (Alburo). BRACKEN’S DAUGHTER Since her mother died when she was about to turn 2, Dolores Bracken Abad did not have vivid memories of Josephine. The tales she knew about her mother were only those related to her by Josephine's in-laws. Remember that she also had no father to tell her about her mom for he himself died a year after Josephine’s demise. Dolores married Antonio Mina of Ilocos. (Though Dolores was not a fruit of Rizal-Josephine’s union, this Ilocano could legitimately boast that he married the only sibling [half-sister] of Jose Rizal’s son). Josephine’s daughter died on December 9, 1987 and was survived by four children. Macario Ofilada, Dolores’ grandson wrote the first full biography of Josephine Bracken, ‘Errante Golondrina’. RIZAL FAMILY’S DISLIKE OF BRACKEN It is almost a historical fact that the Rizal family, except for Narcisa (and possibly Choleng and Paciano), had never liked Jose’s ‘dear unhappy wife’. One may argue that even after the passing of both Jose and Josephine, her memory was not that generously welcomed in the Rizal clan. One friend jokingly concluded, in hindsight, that Josephine was a sort of ‘bad omen’ (if ever you believe in that) and exclaimed, “Malas siya sa buhay ni Rizal.” His ‘theory’ he based on the observation that almost everyone who had become connected to Josephine died young—her own mother (who died shortly 83 after giving birth to her), her real father, her Portuguese step mother, Jose Rizal, Mr. Taufer, and his second husband Vicente Abad. But this argument, which is an instance of a ‘false cause fallacy’, is most likely not the reason the Rizal family did not like Bracken. There was an explicit declaration that the Rizals were suspicious that she was a spy for the friars and regarded her as “threat to Rizal’s security.” (Bantug) Remember that when Bracken and Taufer arrived in Dapitan in 1895, they were with a certain Manuela Orlac. It was Orlac’s being a mistress of a friar which caused some of Jose’s sisters to presume that Josephine had come as friars’ undercover. While staying with Narcisa’s family in Binondo, Bracken would frequently leave the house and return after some hours. To find out where she was going, the Rizal sisters asked someone to trail and keep an eye on her. One afternoon, it was discovered that she had gone to the archbishop’s place. Josephine later confessed that she had indeed gone to see the church official to beg for Rizal’s freedom. The ‘spy-charge’ against Bracken was never proved as it was never true. But even then, the Rizal family could not be persuaded to like her, especially that her union with Jose was not sanctioned by the Church. The family’s antipathy toward her was thus understandable as many were indeed scandalized by the couple’s live-in relationship. As a result, many distasteful stories about the couple were also passed around by gossips. Far from being selfish though, Bracken thought of leaving Dapitan to save Rizal from further humiliation. In fact, she even selflessly induced Rizal to get married should he find someone else in Spain. While Rizal was waiting for a ship which would bring him to his medical mission in Cuba, Josephine wrote him this self-sacrificing unedited letter dated August 13, 1896: If you go to Spain, you see any one of your fancy you better marry her but, dear, heare me, better marry than to live like we have been doing. I am not ashamed to let people know my life with you but as your dear Sisters are ashamed, I think you had better get married to someone else. Your sister Narcisa and your Father, they are very good and kind to me. RIZAL’S ‘DULCE ESTRANJERA’ As a testament of his love for her, Jose Rizal made use of his common-law wife as a model and inspiration in at least two of his artworks: a carving of her head and shoulder (side view) and a plaster statue of her reclining. 84 When Josephine (temporarily) left Dapitan to accompany Taufer to Manila, Rizal gave her this short poem: “A Josefina” Josephine Who to these shores came, Searching for a home, a nest, Like the wandering swallows, If your fate guides you To Shanghai, China, or Japan, Forget not that on these shores A heart beats for you. In Rizal’s last and greatest poem posthumously entitled “Mi Ultimo Adios”, there’s a line which reads, “Adios, dulce estranjera, mi amiga, mi alegria” which is now commonly translated, “Farewell, sweet foreigner, my darling, my delight!” As the line is conventionally accepted as Rizal’s farewell to his “dear unhappy wife,” Josephine Bracken had thus earned the historical moniker, “Rizal’s dulce estranjera (sweet foreigner).” Josephine, for his part, had also immortalized her affection for Rizal through her letters with which she consoled him when he was on his way to Cuba and during his prison days. Some of her letters involved matters like sending him his clothing and the foods he loved like a hundred sweet santoles, lansones, and cheese. But Bracken’s (unedited) letter dated August 13, 1896 stands out as it manifests the purity of her love to our national hero: I am always sorry, thinking of you. Oh, dear, how I miss you, I will always be good and faithful to you, and also do good to my companions so that the good God will bring you back to me. I will try all my best to be good to your family, especially to your dear old Parents: “the hands that we cannot cut, lift it up and kiss it, or adore the hand that gives the blow.” How it made the tears flew in my eyes when I read those few lines of you. Say, darling, say it makes me think of our dear old hut in Dapitan and the many sweet ours we have passed their. Love, I will love you ever; love, I will leave thee never; ever to me precious to thee; never to part, heart bound to heart, or ever to say goodbye. So, my darling, receive many warm Affection and love from your ever faithful and true till death. Josephine Bracken 85 Today, there’s a small street somewhere in Project 4, Quezon City which is named in the memory of Rizal’s “dear unhappy wife”. 86 JOSE RIZAL'S BITTER-SWEET LIFE IN DAPITAN THE DEPORTEE could have stayed in the Dapitan parish convent should he retracted his ‘religious errors’ and made a general confession of his past life. Not willing to accede to these main conditions set by the Jesuits, Jose Rizal instead opted to live at commandant’s residence they called ‘Casa Real’. The commandant Captain Ricardo Carnicero and Jose Rizal became good friends so much so that the exile did not feel that the captain was actually his guard. Later in his life in Dapitan, Rizal wrote a poem ‘A Don Ricardo Carnicero’ honoring the kind commandant on the occasion of his birthday on August 26, 1892. In September 1892, Rizal and Carnicero won in a lottery. The Manila Lottery ticket no. 9736 jointly owned by Rizal, Carnicero, and a Spanish resident of Dipolog won the second prize of Php 20, 0000. Rizal used some part of his share (Php 6, 200) in procuring a parcel of land near the coast of Talisay, a barrio near Dapitan. On a property of more than 10 hectares, he put up three houses made of bamboo, wood, and nipa. He lived in the house which was square in shape. Another house, which was hexagonal, was the barn where Rizal kept his chickens. In his octagonal house lived some of his pupils—for Rizal also established a school, teaching young boys practical subjects like reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and Spanish and English languages. Later, he constructed additional huts to accommodate his recovering out-of-town patients. DAILY LIFE AS AN EXILE During his exile, Rizal practiced medicine, taught some pupils, and engaged in farming and horticulture. He grew many fruit trees (like coconut, mango, lanzones, makopa, santol, mangosteen, jackfruit, guayabanos, baluno, and nanka) and domesticated some animals (like rabbits, dogs, cats, and chickens). The school he founded in 1893 started with only three pupils, and had about more than 20 students at the time his exile ended. Rizal would rise at five in the morning to see his plants, feed his animals, and prepare breakfast. Having taken his morning meal, he would treat the patients who had come to his house. Paddling his boat called ‘baroto’ (he had two of them), he would then proceed to Dapitan town to attend to his other patients there the whole morning. 87 Rizal would return to Talisay to take his lunch. Teaching his pupils would begin at about 2 pm and would end at 4 or 5 in the afternoon. With the help of his pupils, Rizal would spend the rest of the afternoon in farming—planting trees, watering the plants, and pruning the fruits. Rizal then would spend the night reading and writing. RIZAL AND THE JESUITS The first attempt by the Jesuit friars to win back the deported Rizal to the Catholic fold was the offer for him to live in the Dapitan convent under some conditions. Refusing to compromise, Rizal did not stay with the parish priest Antonio Obach in the Church convent. Just a month after Rizal was deported to Dapitan, the Jesuit Order assigned to Dapitan the priest Francisco de Paula Sanchez, Rizal’s favorite teacher in Ateneo. Many times, they engaged in cordial religious discussions. But though Rizal appreciated his mentor’s effort, he could not be convinced to change his mind. Nevertheless, their differences in belief did not get in the way of their good friendship. The priest Pablo Pastells, superior of the Jesuit Society in the Philippines, also made some attempts by correspondence to win over to Catholicism the exiled physician. Four times they exchanged letters from September 1892 to April 1893. The debate was none less than scholarly and it manifested Rizal’s knowledge of the Holy Scriptures for he quoted verses from it. Though Rizal consistently attended mass in Dapitan, he refused to espouse the conventional type of Catholicism. ACHIEVEMENTS IN DAPITAN Rizal provided significant community services in Dapitan like improving the town’s drainage and constructing better water system using empty bottles and bamboo joints. He also taught the town folks about health and sanitation so as to avoid the spread of diseases. With his Jesuit priest friend Sanchez, Rizal made a huge relief map of Mindanao in Dapitan plaza. Also, he bettered their forest by providing evident trails, stairs, and some benches. He invented a wooden machine for mass production of bricks. Using the bricks, he produced, Rizal built a water dam for the community with the help of his students. As the town’s doctor, Rizal equally treated all patients regardless of their economic and social status. He accepted as ‘fees’ things like poultry and crops, and at times, even gave his services to poor folks for free. His specialization was ophthalmology but he also offered treatments to almost all kinds of diseases like fever, sprain, broken bones, typhoid, and hernia. Rizal also helped in the livelihood of the abaca farmers in Dapitan by trading their crops in Manila. He also gave them lessons in abaca-weaving to produce 88 hammocks. Noticing that the fishing method by the locals was inefficient, he taught them better techniques like weaving and using better fishing nets. AS A SCIENTIST AND PHILOLOGIST Aside from doing archaeological excavations, Rizal inspected Dapitan’s rich flora and fauna, providing a sort of taxonomy to numerous kinds of forest and sea creatures. From his laboratory and herbarium, he sent various biological specimens to scientists in Europe like his dear friend Doctor Adolph B. Meyer in Dresden. In return, the European scholars sent him books and other academic reading materials. From the collections he sent to European scholars, at least three species were named after him: a Dapitan frog (‘Rhacophorus rizali’), a type of beetle (‘Apogonia rizali’), and a flying dragon (Draco rizali). Having learned the Visayan language, he also engaged himself in the study of language, culture, and literature. He examined local folklores, customs, Tagalog grammar, and the Malay language. His intellectual products about these subjects, he related to some European academicians like Doctor Reinhold Rost, his close philologist friend in London. SPIES AND SECRET EMISSARY Not just once did Rizal learn that his ‘enemies’ sent spies to gather incriminating proofs that Rizal was a separatist and an insurgent. Perhaps disturbed by his conscience, a physician named Matias Arrieta revealed his covert mission and asked for forgiveness after he was cured by Rizal (Bantug, p. 115). In March 1895, a man introduced himself to Rizal as Pablo Mercado. Claiming to be Rizal’s relative, this stranger eagerly volunteered to bring Rizal’s letters to certain persons in Manila. Made suspicious by the visitor’s insistence, Rizal interrogated him and it turned out that his real name was Florencio Nanaman of Cagayan de Misamis, paid as secret agent by the Recollect friars. But because it was raining that evening, the kind Rizal did not command Nanaman out of his house but even let the spy spend the rainy night in his place. In July the next year, a different kind of emissary was sent to Rizal. Doctor Pio Valenzuela was sent to Dapitan by Andres Bonifacio—the Katipunan leader who believed that carrying out revolt had to be sanctioned first by Rizal. Disguised as a mere companion of a blind patient seeking treatment from Rizal, Valenzuela was able to discreetly deliver the Katipunan’s message for Rizal. But Rizal politely refused to approve the uprising, suggesting that peaceful means was far better than violent ways in obtaining freedom. Rizal further believed that a revolution would be unsuccessful without arms and monetary support from wealthy Filipinos. He thus recommended that if the Katipunan was to start a revolution, it had to ask for the support of rich and educated Filipinos, like Antonio Luna who was an expert on military strategy (Bantug, p. 133). 89 VISITED BY LOVED ONES Rizal was in Dapitan when he learned that his true love Leonor Rivera had died. What somewhat consoled his desolate heart was the visits of his mother and some sisters. In August 1893, Doña Teodora, along with daughter Trinidad, joined Rizal in Dapitan and resided with him in his ‘casa cuadrada’ (square house). The son successfully operated on his mother’s cataract. At distinct times, Jose’s sisters Maria and Narcisa also visited him. Three of Jose’s nephews also went to Dapitan and had their early education under their uncle: Maria’s son Mauricio (Moris) and Lucia’s sons Teodosio (Osio) and Estanislao (Tan). Jose’s niece Angelica, Narcisa’s daughter, also had experience living for some time with her exiled uncle in Mindanao. In 1895, Doña Teodora left Dapitan for Manila to be with Don Francisco who was getting weaker. Shortly after the mother left, Josephine Bracken came to Jose’s life. Josephine was an orphan with Irish blood and the stepdaughter of Jose’s patient from Hongkong. Rizal and Bracken were unable to obtain a church wedding because Jose would not retract his anti-Catholic views. He nonetheless took Josephine as his common-law wife who kept him company and kept house for him. Before the year ended in 1895, the couple had a child who was born prematurely. The son who was named after Rizal’s father (Francisco) died a few hours after birth. (For detailed discussion on Rizal-Bracken relationship, look for the section “Josephine Bracken” under “Rizal’s love life”.) GOODBYE DAPITAN In 1895, Blumentritt informed Rizal that the revolution-ridden Cuba, another nation colonized by Spain, was raged by yellow fever epidemic. Because there was a shortage of physicians to attend to war victims and disease-stricken people, Rizal in December 1895 wrote to the then Governor General Ramon Blanco, volunteering to provide medical services in Cuba. Receiving no reply from Blanco, Rizal lost interest in his request. But on July 30, 1896, Rizal received a letter from the governor general sanctioning his petition to serve as volunteer physician in Cuba. Rizal made immediate preparations to leave, selling and giving as souvenirs to friends and students his various properties. In the late afternoon of July 31, Rizal got on the ‘España’ with Josephine, Narcisa, a niece, three nephews, and three of his students. Many Dapitan folks, especially Rizal’s students, came to see their beloved doctor for the last time. Cordially bidding him goodbye, they shouted “Adios, Dr. Rizal!” and some of his students even cried. With sorrowing heart, He waved his hand in farewell to the generous and loving Dapitan folks, saying, “Adios, Dapitan!” The steamer departed for Manila at midnight of July 31, 1896. With tears in his eyes, Rizal later wrote in his diary onboard the ship, “I have been in that district four years, thirteen days, and a few hours.” 90 JOSE RIZAL: FROM DAPITAN TO BAGUMBAYAN VARIOUS SIGNIFICANT EVENTS happened during Rizal’s Dapitan-to-Manila trip. Leaving Dapitan for Manila on July 31, 1896, the steamer ‘España’ with Rizal as a passenger made some stopovers in various areas. In Dumaguete, Rizal had visited some friends like a former classmate from Madrid and had cured a sick Guardia Civil captain. In Cebu, he carried out four operations and gave out prescriptions to other patients. Going to Iloilo, he saw the historical Mactan island. He went shopping and was impressed by the Molo church in Iloilo. The ship then sailed to Capiz, to Romblon, and finally to Manila. IN MANILA It is said that as the steamer approached Luzon, there was an attempt by the Katipuneros to help Rizal escape (Bantug, p. 135). The Katipunero Emilio Jacinto, disguising himself as a ship crew member, was supposed to have managed to get close to Rizal, while another Katipunan member, Guillermo Masankay, circled the ship in a boat. Firm in his aim to fulfill his mission in Cuba, Rizal accordingly refused to be rescued by Katipunan’s envoys. Rizal arrived in Manila on August 6, 1896, a day after the mail boat ‘Isla de Luzon’ had left for Spain, and so he had to stay in Manila until the next steamer arrived. Afraid that his one-month stay onboard the ship might bring him troubles, he requested the governor general that he (Rizal) be isolated from everyone except his family. The government reacted by transferring him near midnight of the same day to the cruiser ‘Castilla’ docked at Cavite. On August 19, the Katipunan plot to revolt against the Spanish authorities was discovered through the confession of a certain Teodoro Patiño to Mariano Gíl, Augustinian cura of Tondo. This discovery led to the arrest of many Katipuneros. The Katipunan led by Bonifacio reacted by convening many of its members and deciding to immediately begin the armed revolt. As a sign of their commitment to the revolution, they tore their cedulas (residence certificates). Katipunan’s first major assault happened on August 30 when the Katipuneros attacked the 100 Spanish soldiers protecting the powder magazine in San Juan. Because Spanish reinforcements arrived, about 150 Katipuneros were killed and more than 200 were taken prisoner. This bloody encounter in San Juan and the uprisings in other suburban Manila areas on that same day prompted the 91 governor general to proclaim a state of war in Manila and other seven nearby provinces. On the same day (August 30), Blanco issued letters of recommendation on Rizal’s behalf to Spanish Minister of War and Minister of Colonies with a cover letter clearing Rizal of any connection to the raging revolution. On September 2, he was transported to the ship ‘Isla de Panay.’ GOING TO SPAIN The steamer ‘Isla de Panay’ left Manila for Barcelona the next day. Arriving in Singapore on September 7, Rizal was urged by some Filipinos like his copassenger Don Pedro Roxas and Singaporean resident Don Manuel Camus to stay in the British-controlled territory. Trusting Blanco’s words, Rizal refused to stay in Singapore. Without his knowledge however, Blanco and the Ministers of War and the Colonies had been exchanging telegrams, planning his arrest upon reaching Barcelona. As ‘Isla de Panay’ made a stopover at Port Said, Egypt on September 27, the passengers had known that the uprising in the Philippines got worsen as thousands of Spanish soldiers were dispatched to Manila and many Filipinos were either killed in the battle, or arrested and executed. Rizal had the feeling that he had already been associated to the Filipino revolution as his co-passengers became aloof to him. A day after, he wrote a letter to Blumentritt informing him that he (Rizal) received an information that Blanco had an order to arrest him. Before reaching Malta on September 30, he was officially ordered to stay in his cabin until further orders from Blanco come. With Rizal as a prisoner onboard, the ‘Isla de Panay’ anchored at Barcelona on October 3, 1896. He was placed under heavy guard by the then Military Commander of Barcelona, General Eulogio Despujol, the same former governor general who deported Rizal to Dapitan in 1892. Early in the morning of October 6, he was transported to Monjuich prison-fortress. In the afternoon, he was brought to Despujol who told him that there was an order to ship him (Rizal) back to Manila in the evening. He was then taken aboard the ship ‘Colon’ which left for Manila at 8 pm. The ship was full of Spanish soldiers and their families who were under orders not to go near or talk to Rizal. Though he was allowed to take walks on deck during the journey, he was locked up and handcuffed before reaching any port. 92 LAST HOMECOMING Arriving in Manila as a prisoner on November 3, 1896, Rizal was detained in Fort Santiago where he had been imprisoned four years ago. To gather pieces of evidence against him, some of his friends, acquaintances, members of the ‘La Liga,’ and even his brother Paciano were tortured and forcibly questioned. As a preliminary investigation, Rizal underwent a series of interrogation administered by one of the judges, Colonel Francisco Olive—the same military leader who led the troops that forced the Rizal family to vacate their Calamba home in 1890. Those who were coerced to testify against Rizal were not allowed to be crossexamined by the accused. Rizal is said to have admitted knowing most of those questioned, “though he would deny to the end that he knew either Andres Bonifacio or Apolinario Mabini” (Bantug, p. 139). Fifteen pieces of documentary evidence were presented—Rizal’s letters, letters of his compatriots like Marcelo del Pilar and Antonio Luna, a poem (Kundiman), a Masonic document, two transcripts of speech of Katipuneros (Emilio Jacinto and Jose Turiano Santiago), and Rizal’s poem ‘A Talisay.’ The testimonial evidence involved the oral testimonies of 13 Filipinos notably including that of La Liga officers like Ambrosio Salvador and Deodato Arellano, and the Katipunero Pio Valenzuela. Olive submitted the reports to Blanco on November 26 and Captain Rafael Dominguez was assigned as special Judge Advocate in Rizal’s case. Dominguez made a summary of the case and delivered it to Blanco who subsequently sent the papers to Judge Advocate General Don Nicolas Dela Peña. After examining the case, Peña recommended that (1) Rizal be instantly brought to trial, (2) he must be kept in jail, (3) an order of attachment be issued against his property, and (4) a Spanish army officer, not a civilian lawyer, be permitted to defend him in court. On December 8, Rizal was given the restricted right to choose his lawyer from a list of 100 Spanish army officers. He chose Lt. Luis Taviel de Andrade who turned out to be the younger brother of his bodyguard-friend in Calamba in 1887, Jose Taviel de Andrade. Three days after (December 11), the formal charges were read to Rizal in his prison cell, with Andrade on his side. In short, he was accused of being the main organizer and the ‘living soul’ of the revolution having proliferated ideas of rebellion and of founding illegal organizations. He pleaded not guilty to the crime of rebellion and explained that ‘La Liga’, the constitution of which he wrote, was just a civic organization. 93 On December 13, the day Camilo G. de Polavieja replaced Blanco as governor general, papers of Rizal’s criminal case were sent to Malacañang. Concern about the welfare of his people, Rizal on December 15 wrote a manifesto appealing to the revolutionaries to discontinue the uprising and pursue to attain liberty instead by means of education and of labor. But de la Peña interpreted the manifesto as all the more advocating the spirit of rebellion as it ultimately willed the Filipino liberty. Polavieja thus disallowed to issue Rizal’s manifesto. THE RAT IN THE KANGAROO COURT On December 26 morning, the Filipino patriot who was once figuratively referred to by Spanish officials as a ‘trapped rat’ appeared in the kangaroo court inside the military building, Cuartel de España. He was tried before seven members of the military court with Lt. Col. Jose Togores Arjona acting as the president. Judge Advocate Dominguez presented Rizal’s criminal case followed by the lengthy speech of Prosecuting Attorney Enrique de Alcocer. To appeal to the emotions of the Spanish judges, Alcocer went as far as dramatically mentioning the Spanish soldiers who had died in the Filipino traitorous revolt and discriminately describing Rizal as “a typical ‘Oriental,’ who had presumed to rise from a lower social scale in order to attain powers and positions that could never be his” (Bantug, p. 144). At the end, Alcocer petitioned for a death sentence for Rizal and an indemnity of twenty thousand pesos. Rizal’s defense counsel, Lt. Andrade, then took the floor and tried his very best to save his client by reading his responsive defense, stressing too that it’s but natural for anyone to yearn for liberty and independence. Afterward, Rizal was allowed to read his complementary defense consisting of logical proofs that he could have not taken part in the revolution and that La Liga was distinct from Katipunan. He argued, among others, that he even advised the Katipunan emissary (Valenzuela) in Dapitan not to pursue with the plan to revolt; the revolutionists had used his name without his knowledge; he could have escaped either in Dapitan or Singapore if he were guilty; and the civic group La Liga which died out upon his exile did not serve the purpose of the uprising, and he had no knowledge about its reformation. Lt. Col. Arjona then declared the trial over. Expectedly, the entire defense was indifferently disregarded in Rizal’s mock trial as it instantaneously considered him guilty and unanimously voted for the death sentence. 94 The trial ended with the reading of the sentence. Doctor Jose Rizal was found guilty. The sentence was death by firing squad. On December 28, Governor General Polavieja signed the court decision and decreed that the guilty be executed by firing squad at 7 a.m. of December 30, 1896 at Bagumbayan (Luneta). Because Rizal was also required to sign the verdict, he stoically signed his own death sentence. RIZAL’S LAST 25 HOURS Accounts on Rizal’s last hours vary and largely depend on the historian one is reading. What happened in Rizal’s life from 6 a.m. of December 29, 1896 until his execution was perhaps the most controversial in his biography, for the divisive claims—like his supposed retraction and Catholic marriage with Bracken— allegedly occurred within this time frame. Standard biography nonetheless states that at 6 a.m. of December 29, Judge Advocate Dominguez formally read the death sentence to Rizal. At about 7 a.m., he was transferred to either his ‘death cell’ or ‘prison chapel’. He was visited by Jesuit priests, Miguel Saderra Mata and Luis Viza. They brought the medal of the Ateneo’s Marian Congregation of which Rizal was a member and the wooden statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus he had carved in the school. Rizal put the wooden image on his table while he rejected the medal saying "Im little of a Marian, Father.” (“Last Hours of Rizal”). At 8 a.m., the priest Antonio Rosell arrived, after his co-priest Viza left. Rizal shared his breakfast with Rosell. Later, Lt. Andrade came and Rizal thanked his defense lawyer. Santiago Mataix of the Spanish newspaper ‘El Heraldo de Madrid’ interviewed Rizal at about 9 a.m. Then came the priest Federico Faura at about 10 a.m. He advised Rizal to forget about his resentment and marry Josephine canonically. The two had heated discussion about religion as witnessed by Rosell (“Last Hours of Rizal”). Two other priests, Jose Vilaclara and Vicente Balaguer (missionary in Dapitan) also visited Rizal at about 11 a.m. The Jesuits tried to convince Rizal to write a retraction. Though still believing in the Holy Scriptures, Rizal supposedly refused to retract his anti-Catholic views, exclaiming, “Look, Fathers, if I should assent to all you say and sign all you want me to, just to please you, neither believing nor feeling, I would be a hypocrite and would then be offending God.” (Bantug, p. 148). 95 At 12 noon, Rizal was left alone in his cell. He had his lunch, read the Bible, and meditated. About this time, Balaguer reported to the Archbishop that only a little hope remained that Rizal would retract (“Last Hours of Rizal”). Refusing to receive visitors for the meantime, Rizal probably finished his last poem at this moment. Rizal also wrote to Blumentritt his last letter in which he called the Austrian scholar “my best, my dearest friend”. He then had a talk with priests Estanislao March and Vilaclara at about 2 p.m. Balaguer then returned to Rizal’s cell at 3:30 p.m. and allegedly discussed (again) about Rizal’s retraction (Zaide, p. 265). Rizal then wrote letters and dedications and rested for short. At 4 p.m., the sorrowful Doña Teodora and Jose’s sisters came to see the sentenced Rizal. The mother was not allowed a last embrace by the guard though her beloved son, in quiet grief, managed to press a kiss on her hand. Dominguez is said to have been moved with compassion at the sight of Rizal’s kneeling before his mother and asking forgiveness. As the dear visitors were leaving, Jose handed over to Trinidad an alcohol cooking stove, a gift from the Pardo de Taveras, whispering to her in a language which the guards could not comprehend, “There is something in it.” That ‘something’ was Rizal’s elegy now known as “Mi Ultimo Adios.” The Dean of the Manila Cathedral, Don Silvino Lopez Tuñon, came to exchange some views with Rizal at about 5:30 p.m. Balaguer and March then left, leaving Vilaclara and Tuñon in Rizal’s cell. As Rosell was leaving at about 6 p.m., Josephine Bracken arrived in Fort Santiago. Rizal called for her and they emotionally talked to each other (“Last Hours of Rizal”). At 7 p.m., Faura returned and convinced Rizal to trust him and other Ateneo professors. After some quiet moments, Rizal purportedly confessed to Faura (“Last Hours of Rizal”). Rizal then took his last supper at about 8 p.m. and attended to his personal needs. He then told Dominguez that he had forgiven his enemies and the military judges who sentenced him to death. At about 9 or 9:30 p.m., Manila’s Royal Audiencia Fiscal Don Gaspar Cestaño came and had an amiable talk with Rizal. Historian Gregorio F. Zaide alleged that at 10 p.m. Rizal and some Catholic priests worked on the hero’s retraction (Zaide & Zaide, pp. 265-266). Supposedly, Balaguer brought to Rizal a retraction draft made by Archbishop Bernardino Nozaleda (1890-1903) but Rizal did not like it for being long. A shorter retraction made by Jesuit Pio Pi was then offered to Rizal which he allegedly liked. So it is said that he wrote his retraction renouncing freemasonry and his anti-Catholic ideas. Zaide nonetheless admitted that the supposed retraction is now a (very) controversial document. For many reasons, Rizal’s assumed retraction and his 96 supposed church marriage with Bracken have been considered highly dubious by many Rizal scholars. Rizal then spent the night resting until the crack of dawn of December, perhaps praying and meditating once in a while. Zaide however alleged that at 3 a.m., Rizal heard Mass, confessed sins, and took Communion. At about 4 a.m., he picked up the book ‘Imitation of Christ’ by Thomas a Kempis, read, and meditated. At 5 a.m. he washed up, attended to his personal needs, read the Bible, and contemplated. For breakfast, he was given three boiled eggs. Rizal’s grandniece Asuncion Lopez-Rizal Bantug mentioned “three soft-boiled eggs” and narrated that Rizal ate two of them (Bantug, pp. 151-152). Known historian Ambeth R. Ocampo, on the other hand, wrote “three hard-boiled eggs” and related that Rizal “did not have any breakfast” (Ocampo, p. 227). Both historians however wrote that Rizal placed the boiled egg (or eggs) to a cell corner, saying in effect, “This is for the rats, let them celebrate likewise!” Afterward, Rizal wrote letters, one addressed to his family and another to Paciano. To his family, he partly wrote, “I ask you for forgiveness for the pain I cause you … I die resigned, hoping that with my death you will be left in peace…” He also left this message to his sisters: “I enjoin you to forgive one another… Treat your old parents as you would like to be treated by your children later. Love them very much in my memory.” To Paciano, he partially wrote, “I am thinking now how hard you have worked to give me a career … I know that you have suffered much on my account, and I am sorry.” Though some accounts state that Bracken was forbidden from seeing Rizal on this fateful day, Zaide wrote that at 5:30 a.m., she and Rizal’s sister Josefa came. The couple was said to have embraced for the last time and Rizal gave to Josephine the book ‘Imitation of Christ’ on which he wrote the dedication: “To my dear and unhappy wife, Josephine/ December 30th, 1896/ Jose Rizal”. Before Rizal made his death march to Bagumbayan, he managed to pen his last letters to his beloved parents. To Don Francisco, he wrote, “Pardon me for the pain which I repay you … Good bye, Father, goodbye…”. Perhaps told by the authorities that the march was about to begin, Rizal managed to write only the following to his mother: To my very dear Mother, Sra. Dña. Teodora Alonso 6 o’clock in the morning, December 30, 1896. Jose Rizal 97 At 6:30 a.m., Rizal in black suit and black bowler hat, tied elbow to elbow, began his slow walk to Bagumbayan. He walked along with his defense lawyer, Andrade, and two Jesuit priests, March and Vilaclara. In front of them were the advance guard of armed soldiers and behind them were another group of military men. The sound of a trumpet signaled the start of the death march and the muffled sound of drums served as the musical score of the walk. Early in that morning, plenty of people had eagerly lined the streets. Some were sympathetic to him, others—especially the Spaniards—wanted nothing less than to see him die. Some observed that Rizal kept keenly looking around and “it was believed that his family or the Katipuneros would make a last-minute effort to spring him from the trap” (Ocampo, p. 228). Once in a while, Rizal conversed with the priests, commenting on things like his happy years in the Ateneo as they passed by Intramuros. Commenting on the clear morning, he was said to have uttered something like, “What a beautiful morning! On days like this, I used to talk a walk here with my sweetheart.” After some minutes, they arrived at the historic venue of execution. Filipino soldiers were deliberately chosen to compose the firing squad. Behind them stood their Spanish counterparts, ready to execute them also should they decline to do the job. There was just a glitch in the proceeding as Rizal refused to kneel and declined the traditional blindfold. Maintaining that he was not a traitor to his country and to Spain, he even requested to face the firing squad. After some sweet-talk, Rizal agreed to turn his back to the firing squad but requested that he be shot not in the head—but in the small of the back instead. When agreement had been reached, Rizal thankfully shook the hand of his defense lawyer. The military physician then asked permission to feel the pulse of the man who had only a few minutes to live and the doctor was startled to find it normal. Before leaving Rizal in his appointed place, the priests offered him a crucifix to kiss “but he turned his head away and silently prepared for his death” (Ambeth Ocampo, p. 228). When the command had been given, the executioners’ guns barked at once. Rizal yelled Christ’s two last words “Consummatum est!” (“It is finished!”) simultaneously with his final effort to twist his bullet-pierced body halfway around. Facing the sky, Jose Rizal fell on the ground dead at exactly 7:03 in the morning of December 30, 1896. 98 THE DEATH OF JOSE RIZAL: AMBETH OCAMPO’S VERSION Editor’s note: The following is the article written by today’s most famous Filipino historian Ambeth R. Ocampo on Jose Rizal’s death. Simply entitled, “The Death of Jose Rizal,” this historical piece by the current head of the National Historical Institute (of the Philippines) could be deemed refreshing and controversial, as it offers several unpopular and unorthodox accounts of what (presumably) transpired on the day of Rizal’s execution. For one thing, it virtually proclaims that Rizal refused to kiss the crucifix before he was executed, thereby negating the claim of other historians (like Zaide) that the national hero even asked for this Catholic sacramental. Happy reading! "THE OBSERVANT WILL NOTICE metal footprints on the pavement running from Fort Santiago to the Luneta in seafront Manila. They resemble dancing patterns, but actually trace the last steps of Jose Rizal as he walked from his prison cell to the site of his execution on December 30, 1896. The Rizal Centennial Commission claims that the footprints are based on Rizal’s actual shoe size. When people ask why the steps are so small, the quick reply is: “If you are walking to your death, would you hurry?” The slow walk to Bagumbayan field (as Rizal Park or the Luneta was once called) began at 6:30 a.m. on a cool, clear morning. Rizal was dressed in black coat and trousers and a white shirt and waistcoat. He was tied elbow to elbow, but held up his head in a chistera or bowler hat. A bugler signaled his passage, while the roll of drums muffled in black cloth gave cadence to his gait. From Fort Santiago he took a right turn, and walked along the Paseo Maria Cristina (now Bonifacio Drive), which gave him a view lifting the darkness over Manila Bay on the right, and a last glimpse of Intramuros, shadowed by the missing sun, on his left. He walked between two Jesuits, Father Estanislao March and Father Jose Villaclara. They too were in black – the trademark black hats, tunics, and heavy coats that made the young Rizal and his Ateneo schoolmates refer to them as paniki (bats, or colloquially perhaps, batmen). Behind Rizal walked the brother of his former bodyguard, Lieutenant Luis Taviel de Andrade, who had vainly defended him in a farce masquerading as a trial. The streets were lined with people who wanted to see the condemned man, since Rizal was many things to different people: “leader of the revolution,” physician, novelist, poet, sculptor, heretic, subversive. Rizal was a person one could not be neutral about. Like him or hate him, he was a celebrity. Although he was walking to his death, eyewitnesses describe Rizal as serene – a bit pale, not because of fear of his fate, but because he had not had any breakfast. All he had been given were three hard-boiled eggs, which he took to a corner of his prison cell, saying, “This is for the rats; let them have a fiesta, too.” Then he left his cell. Rizal is said to have nodded left and right to acknowledge familiar faces in crowd. From time to time he smiled, and is said to have made a few jokes, and 99 laughed at these himself because the Jesuits flanking him remained somber. Others noticed his eyes dart quickly from left to right, and some believed that members of his family or the Katipuneros would make a last-ditch effort to save him from death. Was Rizal waiting for help that never came? And perhaps for an opportunity to spurn that help? Had he expected to see his family by the roadside? We will never know more than the fact that he was walking to his destiny. In the clear morning Rizal could probably see as far as Susong Dalaga, and appreciate the silhouette of a naked woman on the mountain range across from Manila Bay. “What a beautiful morning!” he said, “On mornings like this I used to take walks here with my sweetheart.” Before reaching Bagumbayan, he glanced at Intramuros, sighed, and seeing the spires of the church of San Ignacio, said: “Is that the Ateneo? I spent many happy years there.” The Jesuits’ response is not recorded. Someone had the foresight to take a photograph of the execution. The scene looked like a box, lined, three or four people deep, on three sides. The empty fourth side faced the bay, and the executioners’ line of fire. Eight Filipino soldiers armed with Remingtons formed the firing squad. Behind them stood the drummers and another line of Spanish soldiers with Mausers, ready to shoot the Filipinos if they refused to shoot, or purposely missed their target. When everyone was in place, there was a slight delay because Rizal refused the customary blindfold, and asked to face the firing squad. The Spanish captain who had guided Rizal to the site insisted that he be shot in the back as ordered, because he was a traitor to Spain. Rizal declared that he had never been a traitor to the country of his birth or to Spain. After some coaxing, Rizal finally turned his back, but again refused the blindfold, and furthermore refused to kneel. After all this haggling he made one last request: that the executioners spare his head, and shoot him in the back towards the heart. When the captain agreed, Rizal clasped the hand of Lieutenant Taviel de Andrade and thanked him once more for the vain effort of defending him before the military court that sentenced him to death. Meanwhile, a curious Spanish military doctor felt Rizal’s pulse, and was surprised to find it regular and normal. The Jesuits were the last to leave the condemned man. They raised the crucifix to his face and lips, but he turned his head away and silently prepared to meet death. The captain raised his saber in the air, ordered his men to get ready, and barked the order: “Preparen!” This was followed by the order to aim the rifles: “Apunten!” In the split second before the saber was brought down with the order to fir – “Fuego!” – Rizal shouted the last two words of the crucified Christ: “Consummatum est!” (It is done). The shots rang out, the bullets hit their mark, and Rizal executed that carefully choreographed twist that he had practiced years before, which made him fall faced up on the ground. People held their breath as soldiers came up to 100 the corpse and gave Rizal the tiro de gracia, one last merciful shot in the head at close range to make sure he was really dead. A small dog, the military mascot, ran around the corpse whining, and the crowd moved in for a closer look, but were kept at bay by the soldiers who stood in the first row of spectators. After a short silence, someone shouted: “Long live Spain! Death to the traitor!” The crowd did not respond. An officer approached the person who had shouted, and berated him. To fill in the gap, the military band played the Marcha de Cadiz. It was 7:03 a.m. The show was over." 101