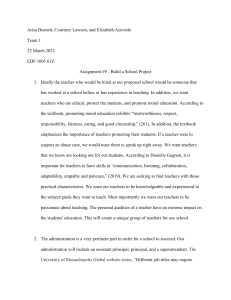

For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. W20571 OWEN BARRY: COPING WITH BREXIT STALEMATE R Chandrasekar wrote this case under the supervision of Professor Neil Bendle solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality. This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized, or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 0N1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) cases@ivey.ca; www.iveycases.com. Our goal is to publish materials of the highest quality; submit any errata to publishcases@ivey.ca. i1v2e5y5pubs Copyright © 2020, Ivey Business School Foundation Version: 2020-07-08 In July 2019, Jack Allen, finance and production manager at Owen Barry Inc. (Owen Barry), was weighing his options for navigating a way out of the turbulence in which the company found itself. As a leading sheepskin products manufacturer in the United Kingdom (UK), Owen Barry was caught in a crisis not of its own making. The two-year countdown to the United Kingdom’s formal exit from the European Union— known as Brexit—had begun in March 2017. The United Kingdom was to leave the European Union on March 29, 2019, but the plan had recently spun out of control. On March 20, the UK’s prime minister had sought an extension until June 30 on the grounds that there was no consensus on the withdrawal agreement in the House of Commons, the UK Parliament. The European Union offered two alternative dates—May 22, provided the withdrawal agreement was ready, and April 12 if the agreement was not ready. On April 2, the United Kingdom sought a further extension. On April 10, both the United Kingdom and the European Union agreed to a new exit date of October 31, 2019. 1 The departure date had been extended twice by a total of seven months, from March 2019 to October 2019, but the suspense had begun three years earlier, in June 2016, when a public referendum in favour of exiting the European Union had passed. Allen recalled having had a rush of adrenaline when he had voted in favour of Brexit in the referendum. He was certain that the United Kingdom would reclaim the national identity he believed it had lost in the European Union. He was also certain that Owen Barry would stand tall once again, promoting its “Made in England” label to customers worldwide. But the extra time that Brexit had gone into, with the departure date extensions, and the possibility of prolonged uncertainty over a formal departure, had aggravated the concerns he had been facing at his desk since June 2016. Allen had three main concerns: How should he deal with the exchange rate fluctuations that had affected Owen Barry’s business? How should he deal with issues around sourcing and importing critical raw materials? How should he deal with problems around recruitment and retention of a skilled workforce? BREXIT Europe was in ruins after the end of World War II, when six countries of the region—Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany—came together in 1951 to form the European This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 2 9B20A061 Coal and Steel Community, headquartered at Brussels. The formation was a two-pronged attempt at preempting another war and leveraging trade and commerce for Europe’s economic well-being. By 1957, the group, by then known as the European Economic Community (EEC), was characterized by not only a common market but also an integration of the customs duties that facilitated it. The British Empire was shrinking at the time, as its colonies gained independence, and the United Kingdom was compelled to look for new markets for its goods and services. In 1961, it applied for membership in the EEC. The application was rejected over concerns, from France in particular, that the United Kingdom would team up with the United States to control Europe. When the country applied for the second time in 1967, it was declined again. The United Kingdom finally joined the EEC in 1973, when the Conservative party, led by Edward Heath, was in power. 2 Although the rationale for membership was rooted in economic factors such as jobs and trade, there were frequent rumblings in the United Kingdom about being part of a group that was becoming a political establishment in its own right. The EEC was taking on new members as part of its Mediterranean expansion. More would join after the fall of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989. By 1991, Europe was no longer just a common market: it was on its way to becoming a full-fledged political entity with a parliament, a flag, and an anthem. It would also have its own foreign and defence policies in addition to bureaucratic institutions, a judiciary system, and a central bank. The European Union, as it was re-christened, would also have its own currency. By July 2013, the European Union had a total of 28 member countries. 3 Citizens of European Union countries enjoyed common benefits. They could travel, live, and work freely across Europe; they could hold property in a country of their choice; and students could seek education or work experience through specially designed programs like Erasmus. As the world’s most open economic bloc, the European Union was also helping the countries that were least developed at the time, such as Brazil, with free access to its markets. It was also financing the development of infrastructure—including roads, bridges, and ports—among these countries so that they could increase their exports to European Union nations. 4 Rumblings about the United Kingdom’s membership in the European Union were rooted in various grounds: the United Kingdom was seen to be losing its national identity and sovereignty; European Union laws had taken precedence over the laws made by the UK Parliament; UK firms had become takeover targets of European firms; and the United Kingdom was also paying more into the European Union budget than it was getting in return. 5 For example, in 2017, the United Kingdom was the second-largest net contributor, at €7.43 billion, 6 after Germany at €12.8 billion. 7 Many were unhappy about the perceived lack of control over immigration matters such as how many foreign nationals would be allowed into the United Kingdom, what their income levels should be, and from which countries they came. The growing clamour had led to the public referendum on the issue in June 2016. The referendum was acrimonious, involving allegations of racism. The nation was shocked by the murder, a week before the referendum, of a pro-European Union member of Parliament—a mother of two young children—by a man who gave his name in court as “death to traitors, freedom for Britain.” 8 Faced with the core question “Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?,” 17,410,742 voters (51.9 per cent) favoured the “leave” option and 16,141,241 voters (48.1 per cent) favoured “remain.” 9 Three separate opinion polls, conducted soon after the referendum, asked Britons why they voted the way they did. While “sovereignty” and “immigration” were the two main reasons why people voted to leave the European Union, “the economy” was the main reason why people voted to remain. 10 This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 3 9B20A061 An immediate fallout of the referendum was a fall in the value of the UK pound sterling (pound). The pound was worth US$1.4811 on the day of the vote, and it dropped to $1.29 soon after the results were announced (see Exhibit 1). 12 The 15 per cent fall put UK businesses on alert. There was also a period of extended political turmoil, beginning with the resignation of Prime Minister David Cameron, who had shepherded the referendum and was in favour of remaining a member of the European Union. This was followed by the resignation of his successor, Theresa May, who also favoured remaining but had been compelled to carry out the popular mandateand had failed to do so within the timeline. The referendum had not specified exactly what leaving the European Union meant. The ways for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union could be grouped into three broad categories: a soft exit, a hard exit, and a no-deal exit. A soft exit meant any number of arrangements by which free trade would continue as hitherto, with some modifications to be determined as part of the withdrawal agreement between the United Kingdom and the European Union. This would likely include the United Kingdom remaining part of the European Union Customs Union. A hard exit meant a clean and complete withdrawal from the European Union after a transition period. The United Kingdom would regain control over immigration and trade; the prevailing trade deals would completely disappear; and businesses would have to pay tariffs, to be determined as part of the withdrawal agreement. The transition period gave a small amount of time for new trade deals to be struck. A no-deal exit meant a clean and complete exit without a transition period. The breakup would be abrupt. This would be when the World Trade Organization tariffs would replace the existing trade tariffs between the United Kingdom and the European Union. There was also the option, simmering beneath the surface, of no Brexit, since a sizable proportion of the population still hoped the decision would be reversed and there would be no Brexit at all. 13 The period following June 2016 was tense, with uncertainty for individual businesses. It was also costly for the UK economy. The Bank of England estimated in February 2019 that Brexit had cost the United Kingdom £800 million 14 ($1.06 billion) per week since the June 2016 referendum. 15 An April 2019 report by Goldman Sachs pegged the weekly costs at £600 million while stating that the gross domestic product of the United Kingdom had decreased by 2.5 per cent in 2017 compared to its growth prior to the mid-2016 vote. 16 According to the Ernst & Young Financial Services Brexit Tracker, financial services and manufacturing plants had eliminated thousands of jobs in the United Kingdom—both existing and planned—as companies prepared for greater tariffs and trade barriers with the European Union. 17 A 2017 report from the National Audit Office, an independent watchdog, outlined an increase in the number of official procedures post-Brexit: customs declarations, for example, would increase from 55 million to 255 million. It also said that at least 145,000 traders would need to make customs declarations for the first time and that new customs controls could apply to £423 billion worth of goods. 18 UK businesses trading across international borders and those with suppliers and customers based in the European Union would be lose access to the European Union’s current free trade arrangements. They had common challenges in three areas: supply chain, trade tariffs, and workforce retention. Supply chain considerations involved increased costs, administrative complexity, and changes in delivery lead times. Tariff considerations involved the transition from a border-free zone to a new order of duties. Workforce considerations involved the retention of employees in industries dependent on a transient migrant workforce (e.g., fruit pickers) and skilled workers (e.g., staff of the National Health Service). The government had advised businesses trading with the European Union to consider stockpiling goods, but there was insufficient warehousing capacity in the United Kingdom to accommodate this. Vacancy rates for warehousing, which had been falling steadily since 2014, were at 6 per cent nationally and 3 per cent in and around London. Large companies had managed to build inventory buffers, but small- and medium- This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 4 9B20A061 sized firms (SMEs) did not have the means to do so. Enterprises that normally planned their inventory one season in advance were badly affected. 19 UK FASHION INDUSTRY The United Kingdom was a global leader in fashion. London Fashion Week ranked alongside events in New York, Milan, and Paris. Fashion colleges in the United Kingdom were considered world-class and were known for having trained many international fashion stars. Fashion was considered part of the United Kingdom’s “soft power” and a fundamental driver of the country’s economic and cultural development. 20 The industry had revenues of £32.3 billion in 2017, having grown by 5.4 per cent over 2016. Ninety per cent of fashion brands in the United Kingdom had originated as SMEs. There were a total of 59,395 SME fashion businesses in the United Kingdom, employing over 890,000 people, many of them young. 21 On the supply side, 75 per cent of the components for fashion products made in the United Kingdom— comprising leather, yarn, cotton, and silk, among other components—were imported from European Union countries. The United Kingdom imported £10 billion worth of clothes and shoes alone from the European Union annually. On the demand side, 74 per cent of UK fashion and textile exports went to the European Union. Products were also crossing borders many times because of close-knit value chains. For example, a shirt could be designed by a company in the United Kingdom employing skilled pattern designers from France; manufactured in Portugal with fabrics from Italy, Turkey, and India; photographed in the United Kingdom; wholesaled to international buyers in France; and sold back to shops in the United Kingdom to be retailed worldwide. Any delays at borders would cause problems for businesses and could necessitate the relocation of jobs and employees. 22 The Brussels office of the European Union was funding the development of creative sectors such as fashion among member nations. It supported new product development and consumer research. It was also involved in protecting the human rights of workers, like those in the garment industry for example, and promoting safe working environments. Its Erasmus program enabled students of European Union countries to travel, study, and gain international experience. Post-Brexit, it was not clear whether funding would continue. 23 Arguably, one of the contributions of the European Union to the fashion industry was in safeguarding brands and trademarks, which were the lifeblood of the fashion industry. Businesses could obtain protection from the European Union Intellectual Property Office, avoiding the need to register separately with each EU country. One could not ignore the EU’s big-picture contribution of ensuring peace in the region, which reflected the reason the six founding EU members had come together in the first place. 24 The United Kingdom’s fashion industry did not vote for Brexit. Ninety per cent of designers in the country told the British Fashion Council they were voting to remain part of the European Union. They were worried that, post-Brexit, London would lose its reputation as a global fashion capital. 25 OWEN BARRYCOMPANY BACKGROUND Located in Somerset, long considered the heart of Britain’s 1,000-year-old sheepskin industry, Owen Barry was founded in 1948. Five generations of the Barry family had been working with leather, lambskins, sheepskins, and cowhides ever since to produce premium-quality outerwear for men and women. The current generation of entrepreneurial managers comprised a mother and daughter duo—Cindi and Chas— This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 5 9B20A061 at the helm. The company was listed under the official Standard Industrial Classification as a “leather and sheepskin and manufacturer.” Leather and sheepskin were the two primary raw materials with which Owen Barry made its products. The company’s annual revenue had averaged £1.6 million in recent years. It employed 34 staff at its manufacturing facility in Somerset, 27 of whom worked in the factory and seven of whom worked in support functions at the back office. Four of the factory workers were from Eastern Europe, bringing with them unique skill sets in handicrafts. The work force was mature, with an average tenure of 12 years. The company sourced sheepskin from the European Union, principally from Spain and Turkey. The imports were tariff-free because Spain was part of the European Union while Turkey was part of the Customs Union. Owen Barry had to pay 20 per cent of each invoice as value added tax (VAT) at the port of entry for goods from Turkey. The duty affected cash flow but not the final costs because the company could claim reimbursement of VAT quarterly from the UK government. The sheepskin was often of UK origin, having been imported by tanneries in the European Union from sheep farms in the United Kingdom. The onceflourishing tannery industry in the United Kingdom had largely disappeared in the 1990s because of cheap imports from China. For decades, Owen Barry had six regular suppliers in Spain and Turkey, who provided 60 per cent of the company’s annual shipment volume. It also bought sheepskin from wholesale merchants who serviced the needs of many customers. The consignments travelled by sea for 14 days before landing in a UK port for clearance. The sheepskin produced in Turkey and Spain was considered the finest in the world, in part because the climate of these countries was perfect for raising sheep with thin skins, resulting in wool that was not particularly dense. As a result, the coats were warm but not heavy. Spain was, in fact, home to the famous Merino sheep. Spanish sheepskin was held in high regard in clothing manufacturing for its softness and ultra-light weight. It commanded a premium over the heavier skins from Australia. The latter were the preferred raw material for products like boots and slippers. Brazil and Italy were the principal sources of leather for Owen Barry. The consignments carried tariffs, but Owen Barry was not directly involved in tariff payments since it paid a consolidated amount to the merchants from whom it imported the raw material. Owen Barry regularly participated in industry tradeshows and industry forums in a bid to stay on top of contemporary trends. Its team visited tanneries based in Europe and South America, not only to inspect the skins but also to track dyeing processes, effluent disposal, and energy emissions at these facilities. The company had about 100 customers overall, but 60 per cent of its sales came from six customers. The main customers were department stores (in both the United Kingdom and the United States) and agent distributors (in Japan and South Korea). It did not have long-term, legally-binding contracts with these customers but rather had long-term business relationships, which were more enduring. About 10 per cent of its sales was direct to customers in the United Kingdom. This online channel, more commonly known as business-tocustomer (B2C), had higher margins for Owen Barry. It comprised about 15 per cent of UK sales. The company exported 40 per cent of its output, with the United States accounting for 47 per cent and Japan for 45 per cent of exports. The Japanese traders relied on certainty for factors such as price and delivery schedule, following just-in-time and similar inventory management practices. Brexit had unsettled many of Owen Barry’s customers in Japan for that very reason. This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 6 9B20A061 Owen Barry’s products were designed for cold climates such as the northern parts of the United States and Canada, which were natural markets. Climate change was a major risk for the company; it was witnessing an erosion of demand in parts of the world that were becoming warmer. Japan, its major export market, had become warmer in the last few years due to rising sea levels. In July 2018, for example, the country had witnessed a heat wave that peaked at 41 degrees Celsius (106 degrees Fahrenheit). It claimed 80 lives and led to the hospitalization of 30,000 people, forcing the government to declare it a natural disaster. 26 The company thus renewed its marketing efforts in South Koreawhere it was very hot in summer but also very cold in winterprincipally as an alternative to Japan. The threat of counterfeit goods had pre-empted Owen Barry’s entry into China. Sensing the company’s potential interest in the market, a local entrepreneur had officially registered the Owen Barry name, just as the company was seeking a foot in the door, and demanded a hefty sum to surrender the title. Smaller markets like South Korea were easier to get into and more manageable in terms of product volumes. The company’s production capacity was unable to supply a seemingly huge Chinese demand. Owen Barry had diversified its product range over the years. It had developed handbags, rugs, shrugs, gloves, and key-holders in a bid not only to create a rounded offering for the customer but also to counter the seasonal nature of its business. The company took orders for sheepskin products from its institutional customers from January to March, made the products from April to July, and delivered them from August to October, in time for the cold season and Christmas. The lead time was around 10 months from the point of order to the point of shipping the finished goods. Every order was made to specifications; nothing was made for stock. A major element of the company’s value proposition was the lifetime guarantee it offered on its products. Every Owen Barry product was “christened,” carrying a name that conveyed somethingwhether about its origins or its core concept or its expected usage—and every name had a story. Some of Owen Barry’s products had become classics. The company maintained a record of each of its products, showcasing the design and the timeline for any customer interested in it. Owen Barry had no plans to move from this customization model to the mass-market model. For example, Walmart Inc. was not a customer Owen Barry would be courting. Its products were premium; a sheepskin coat sold for between £1,500 and £2,000. But the company did have several growth plans, beyond Brexit. Expanding B2C was one of these. Doing so would enable the company to find the market pulse more closely and to stay grounded. While it had no plans to set up its own stores, it was keen on placing its own sales staff at kiosks in some of the leading luxury stores. This move would be consistent with the premium positioning the company valued. Deploying its own staff at a designated Owen Barry kiosk within a large department store would be economical, Allen had estimated, only at a sales level of about £20,000 per month from the kiosk. Owen Barry prided itself on upholding the philosophy of UK heritage and manufacturing. The company believed that it was important to keep traditional handicraft skills flourishing alongside the fast-paced evolution of technology. It also believed in the “Made in England” label it promoted in overseas markets. That was one of the reasons why it was not planning to relocate to a country within the European Union, as several UK SMEs were beginning to do in the wake of uncertainty over Brexit. The company’s interests were linked intricately to Somerset, where it had been founded. Allen was in favour of Brexit on a personal level. He believed that the decision-making carried out in the European Union was not democratic and did not necessarily suit the United Kingdom. The downside of This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 7 9B20A061 being part of the European Union was greater, as he saw it, than the upside. He also believed the European Union was benefiting from the trust that international markets had in the United Kingdomin its labour standards, for example, among other thingsand that the United Kingdom should leverage that trust from a stand-alone position to its own benefit. THE ISSUES BEFORE ALLEN Dealing with Exchange Rate Fluctuations The cost of sheepskin imports had gone up by 28 per cent, due to currency fluctuations alone, over a period of three years since the United Kingdom had voted in favour of Brexit. It was not possible for Owen Barry to recover the additional costs from customers in the middle of the year since prices were mainly revised only on an annual basis. The revision would normally be made in October, when deliveries for the current season were completed and negotiations for the next fashion season began. Typically, Owen Barry added 8 per cent to the prevailing rate of exchange in October as a contingency to cover anticipated exchange rate fluctuations between the pound and the US dollar (for US customers) and between the pound and the euro (for domestic customers). The provision had been generally adequate in the past, since currency movements had not exceeded 8 per cent through a year. Post-Brexit, however, the cut-off points were being breached midway through the financial year. For example, for the year ending March 2017, the company had incurred an exchange rate loss of $71,513. The company had quickly pegged the contingency at 15 per cent of the prevailing exchange rate for the financial year (FY) 2017−18. The step had led to an exchange rate gain of $16,577 for the year ending March 2018. The gain had, however, relapsed into a loss of $8,813 for the year ending March 2019 because of a further fall in the value of the pound. In looking for options other than contingency, Allen had found a tactical way of dealing with the situation. Pre-Brexit, Owen Barry was buying raw materials and selling finished goods in both euros and dollars. Post-Brexit, it started buying raw material only in euros and selling in the US market only in dollars. It simplified the somewhat messy transactions; it also generated a competitive advantage. When raw material prices increased in the light of a weakening pound in relation to the euro, the dollar−pound rate acted as a counterpoint in the light of a strengthening dollar. The hike in costs on the supply side was offset by an increase in the value of receivables on the demand side. Over time, they were balancing out. However, there was an element of risk when the company bought sheepskins in euros and sold the finished goods in either pounds (in the domestic market) or another currency (in the non-US markets, largely Japan). Comprising nearly 80 per cent of overall sales revenue (60 per cent in the domestic market and 20 per cent in the export market), this segment had no coverage for currency fluctuations. What compounded the situation was the drying up of orders since June 2016 from Japanese customers, who were wary of dealing with the uncertainty over Brexit and who were switching suppliers accordingly. Allen wondered how he should manage the swings in exchange rates in order to provide a consistent wholesale price to customers without compromising the profits the company had already budgeted. It was important to safeguard the relationships it had built up over the years with institutional customers. Allen’s experience suggested that, for his Japanese contacts, their word was their bond and they believed in personal commitments rather than legal contracts. For US customers, any mid-year hike in prices, however small, was a red flag; in Allen’s personal experience, events outside of the United States, however significant, were of limited importance to US customers. The red flag would go up because Brexit would not figure into their calculations and they presumed that UK traders were making more money than they should on a normal day. This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 8 9B20A061 Dealing with Raw Materials Sourcing One of the biggest concerns in international trade were delays in the cross-border mobility of goods and services. Owen Barry had not noticed any form of border delays since June 2016, particularly on the supply side. The main reason for this was that the company’s imports of raw materials from the European Union were tariff-free and the borders were seamless. But in the event of a no-deal Brexit, border-free zones would no longer exist. Tariffs would come into play with each country of the European Union. The paperwork would also increase because the country of origin would become a crucial part of the trade documentation. The UK government’s own no-deal planning, Operation Yellowhammer, had suggested that cross-channel goods could face “significant disruption.” 27 Owen Barry was in a strong position because of two elements of its business model: (1) it booked its orders for the entire season five to six months in advance of the dates it would ship out finished goods, and (2) it manufactured everything to customer specifications. Paradoxically, the two elements also made it vulnerable to the hazards of piling up inventory—of both raw materials and finished goods—beyond a threshold. Backward integration was one of the options before Allen. Owen Barry could buy sheepskin locally from sheep farms in the United Kingdom and process it locally at a tannery, which it could set up in Somerset, where tanneries had at one time been the basis of a thriving industry. But that was an untested ground with no guarantee of success. Allen was therefore looking at another option: developing partnerships with some of the remaining local tanneries. Many of its peers in the United Kingdom were buying sheepskin from Pakistan, India, and China. However, the lead times for doing so would be long, running into weeks, and the quality was not always world class. Dealing with Recruitment and Retention of a Skilled Workforce The manufacture of leather and sheepskin products involved a heavy manual component. Everything was cut by hand using either a hand knife or a metal-frame knife with a clicker press that would knock the knife into place. Sewing machines and industrial irons were the only machinery used on the shop floor. Many tools used on the shop floor were fully depreciated. The way they were used by labourers had not changed over time. The manual component prevailed through the entire value chain, and manufacturing sheepskin products was considered an art since no two skins were the same. An experienced tanner could usually tell the breed of sheep, the type of pasture on which it had been reared, and the condition the sheep was in. Tanning was a traditional craft that often ran in families, passed down from one generation to the next. Owen Barry had realized early on that local workers were not interested in doing what they viewed as lowlevel jobs involving manual work. The company therefore recruited workers from Eastern Europe, mainly from Poland, Romania, and Lithuania. The region was known for people who were skilled in handicrafts, liked using their hands, enjoyed the physical aspect of their work, and took pride in the materials they dealt with. They came to the United Kingdom to find work that honoured their skill sets, to earn a living, and to send money home to their dependents. Allen found that they had a great work ethic. One of the cutters who did sheepskin coats had been with Owen Barry for 50 years. He had joined as an apprentice and spent the entire first year learning how to use a knife before he could cut a piece of sheepskin. The job required good eyesight, which enabled the cutter to aggregate sheepskins into colour-matched sets. The company once thought of investing in a cutting machine but quickly gave up this idea because handmade was part of the core value proposition at Owen Barry. This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 9 9B20A061 In June 2016, the “people debate” of Brexit involved the question of who among EU citizens would be allowed to stay in the United Kingdom. In June 2019, the question was around who among them wanted to stay on and whether EU citizens wanted to come to the United Kingdom. The number of migrants from Eastern Europe to the United Kingdom had already decreased post-Brexit because the United Kingdom was seen as less welcoming. 28 The situation had also affected Owen Barry. In early 2019, a cutter from Romania left, citing uncertainty surrounding the company’s business volume. He believed export orders would begin to dwindle, reducing his working hours and cutting his overtime earningone of the major reasons he had left his home country in the first place to join Owen Barry. This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 10 9B20A061 EXHIBIT 1: POUND−US DOLLAR MOVEMENT, JUNE 2016−JUNE 2019 Source: Created by the case authors using data from Trading Economics, accessed www.tradingeconomics.com. November 19, 2019, This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 11 9B20A061 EXHIBIT 2: OWEN BARRY INC. PROFIT & LOSS ACCOUNT Year Ending March (in £) Sales by Geography United Kingdom United States Japan Others Total Sales Less: Discounts Total Net Sales Less: Cost of Sales Purchases Import Duty/C&F Exchange Rate Loss/(Gain) Wages Subcontract Commission Finance Charges Depreciation Total Cost of Sales Gross Profit Less: Sales & General Admin. Expenses Salaries Rent, Rates, & Insurance Professional Fees Training Office Expenses Travelling Promotion/Exhibition Recruitment Miscellaneous Total SGA Net Profit/(Loss) 2016 2017 2018 2019 893,547 330,602 275,293 37,352 1,536,794 13,520 1,523,274 1,020,432 230,652 341,013 36,826 1,628,923 12,338 1,596,585 1,076,382 291,071 242,128 28,276 1,637,857 17,547 1,620,310 898,684 256,467 244,065 42,348 1,441,564 10,013 1,431,551 620,666 11,389 3,137 400,671 11,432 10,891 26,697 18,516 1,103,399 419,875 642,322 10,010 71,513 418,866 13,832 3,859 132,486 15,380 1,208,268 408,317 691,451 9,867 (16,577) 434,213 21,814 8,785 26,097 12,723 1,188,373 431,937 593,829 11.395 8,813 434,671 15,870 17,274 21,776 16,339 1,128,968 302,583 239,698 38,662 11,004 3,575 40,275 26,625 77,465 21,302 458,606 (38,731) 250,150 27,258 17,490 1,513 50,841 37,089 63,621 20,406 468,368 (60,051) 187,738 31,888 17,405 2,780 58,466 34,676 53,898 3,167 15,918 405,936 26,001 167,614 37,838 14,366 62,864 50,802 26,751 20,173 380,408 (77,825) Note: SGA = selling, general, and administrative; C&F = cost and freight. Source: Company files. This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021. For the exclusive use of A. FARIAS, 2021. Page 12 9B20A061 ENDNOTES 1 Nigel Walker, “Brexit Timeline: Events Leading to the UK’s Exit from the European Union,” UK Parliament House of Commons Library, October 30, 2019, accessed October 31, 2019, https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-7960#fullreport. 2 “The History of the European Union,” European Union, accessed October 11, 2019, https://europa.eu/european-union/abouteu/history_en. 3 Ibid. 4 European Commission, 10 Ways the EU Supports the World’s Least Developed Countries, EU Trade and Development Policy, accessed October 30, 2019, https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/september/tradoc_154961.pdf. 5 Juliette Ringeisen-Biardeaud (2017), “‘Let’s Take Back Control’: Brexit and the Debate on Sovereignty,” Revue Francaise de civilization Britannique 22, no. 2 (2017). 6 € = EUR = euro; €1 = US$1.12 on July 31, 2019. 7 Tamara Kovacevic, “EU Budget: Who Pays Most In and Who Gets Most Back?,” BBC News, May 28, 2019, accessed October 31, 2019, www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-48256318. 8 Robert Booth, Vikram Dodd, Keving Rawlinson, and Nicola Slawson, “Jo Cox Murder Suspects Tells Court His Name is ‘Death to Traitors, Freedom for Britain’,” Guardian, June 18, 2016, accessed October 30, 2019, www.theguardian.com/uknews/2016/jun/18/thomas-mair-charged-with-of-mp-jo-cox. 9 Walker, op. cit. 10 Centre for Social Investigation, CSI Brexit 4: People’s Stated Reasons for Voting Leave or Remain, Economic & Social Research Council, April 24, 2018, accessed October 30, 2019, https://ukandeu.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/CSI-Brexit4-People%E2%80%99s-Stated-Reasons-for-Voting-Leave.pdf. 11 All dollar amounts in the case are US dollars. 12 Trading Economics, accessed June 5, 2020, www.tradingeconomics.com www.tradingeconomics.com. 13 Daniel Liberto, “Hard, Soft, On Hold or No Deal: Brexit Outcomes Explained,” Investopedia, January 23, 2019, accessed June 5, 2020, www.investopedia.com/hard-soft-on-hold-or-no-deal-brexit-outcomes-explained-4584439. 14 £ = GBP = Great Britain pound; £1 = US$1.32 on July 31, 2016. 15 Gertjan Vlieghe, “The Economic Outlook: Fading Global Tailwinds, Intensifying Brexit Headwinds,” Bank of England, February 14, 2019, accessed June 30, 2019, www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2019/gertjan-vlieghe-speech-at-theresolution-foundation. 16 Helen Reid, “Brexit Uncertainty has Cost Britain £600 Million a Week – Goldman Sachs,” Reuters, April 1, 2019, accessed June 6, 2019, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-britain-eu-goldmansachs/brexit-uncertainty-has-cost-britain-600-million-aweek-goldman-sachs-idUKKCN1RD1T8. 17 Andrew Soergel, “Brexit’s Heavy Costs on the United Kingdom,” US News & World Report, April 10, 2019, accessed June 6, 2019, www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2019-04-10/brexits-costs-on-british-european-economies-continueto-rise. 18 Comptroller and Auditor General, “The UK Border Issues and Challenges for Government’s Management of the Border in Light of the UK’s Planned Departure from the European Union,” October 20, 2017, accessed July 10, 2019, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads /2017/10/The-UK-border.pdf. 19 ING, “Stockpiling Frenzy Lifts UK Growth during Bumpy First Quarter,” ING Think: Economic and Financial Analysis, May 10, 2019, accessed June 8, 2020, https://think.ing.com/snaps/stockpiling-frenzy-lifts-uk-growth-during-bumpy-first-quarter/. 20 Fashion Roundtable, “Brexit and the Impact on the Fashion Industry,” March 2018, accessed October 11, 2019, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a1431a1e5dd5b754be2e0e9/t/5ac080ed70a6ad85f4bcd50b/1522565362283/Fashio n-Roundtable-Brexit-and-The-Impact-on-the-Fashion-Industry-Paper.pdf. 21 Ibid. 22 Ibid. 23 Ibid. 24 Andrew Williams, “How Valid is the Claim that the EU Has Delivered Peace in Europe,” New Statesman, May 9, 2016, accessed October 31, 2019, www.newstatesman.com/world/2016/05/how-valid-claim-eu-has-delivered-peace-europe. 25 Fashion Roundtable, op. cit. 26 “How the Climate Crisis Impacts Japan,” The Climate Reality Project, August 7, 2019, accessed October 24, 2019, www.climaterealityproject.org/blog/how-climate-crisis-impacts-japan. 27 “Brexit: Operation Yellowhammer No-Deal Document Published,” BBC News, September 11, 2019, accessed October 31, 2019, www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-49670123. 28 Frey Lindsay, “Figures Show More Eastern Europeans Are Leaving the U.K. After Brexit,” Forbes, August 27, 2019, accessed October 31, 2019, www.forbes.com/sites/freylindsay/2019/08/27/figures-show-more-eastern-europeans-the-areleaving-the-u-k-after-brexit/#433c87ca4261. This document is authorized for use only by ANAIS FARIAS in Finanzas Internacionales AJ2021 taught by KARLA MACIAS, ITESM from Apr 2021 to Jul 2021.