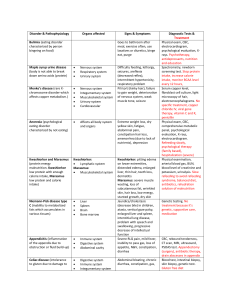

Kwashiorkor Kwashiorkor is a type of malnutrition characterized by severe protein deficiency. It causes fluid retention and a swollen, distended abdomen. Kwashiorkor most commonly affects children, particularly in developing countries with high levels of poverty and food insecurity. People with kwashiorkor may have food to eat, but not enough protein. What is kwashiorkor? Kwashiorkor is one of the two main types of severe protein-energy undernutrition. People with kwashiorkor are especially deficient in protein, as well as some key micronutrients. Severe protein deficiency causes fluid retention in the tissues (edema), which distinguishes kwashiorkor from other forms of malnutrition. People with kwashiorkor may look emaciated in their limbs but swollen in their hands and feet, face and belly. The distended abdomen typical of kwashiorkor can be misleading in people who are actually critically malnourished. Who does kwashiorkor affect? Kwashiorkor is rare in developed countries. It’s mostly found in developing countries with high rates of poverty and food scarcity. Poor sanitary conditions and a high prevalence of infectious diseases also help set the stage for malnutrition. Kwashiorkor can affect all ages, but it’s most common in children, especially between the ages of 3 to 5. This is an age when many children have recently transitioned from breastfeeding to a less adequate diet — one higher in carbohydrates but lower in protein and other nutrients. What is the difference between kwashiorkor and marasmus? Kwashiorkor and marasmus are the two main types of severe protein-energy undernutrition recognized by healthcare providers worldwide. The main difference between them is that kwashiorkor is predominantly a protein deficiency, while marasmus is a deficiency of all macronutrients — protein, carbohydrates and fats. People with marasmus are deprived of calories in general, either because they’re eating too little or expending too many, or both. People with kwashiorkor may not be deprived of calories in general but are deprived of protein-rich foods. SYMPTOMS AND CAUSES What are the signs and symptoms of kwashiorkor? Edema (swelling with fluid, especially in the ankles and feet). Bloated stomach with ascites (a build-up of fluid in the abdominal cavity). Dry, brittle hair, hair loss and loss of pigment in hair. Dermatitis — dry, peeling skin, scaly patches or red patches. Enlarged liver, a symptom of fatty liver disease. Depleted muscle mass but retained subcutaneous fat (under the skin). Dehydration. Loss of appetite (anorexia). Irritability and fatigue. Stunted growth in children. What other complications can kwashiorkor cause? Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). Hypothermia (low body temperature). Hypovolemia (low blood volume) and hypovolemic shock. Electrolyte imbalances resulting from dehydration. Immune system failure, causing frequent infections and slow wound healing. Cirrhosis of the liver and liver failure. Atrophy of the pancreas, leading to digestive difficulties. Atrophy of the gastrointestinal mucosa, possibly leading to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Growth and developmental delays in children. Starvation and death. What causes kwashiorkor? Protein deficiency is the main feature of kwashiorkor, and many researchers believe it's the cause — but not all are convinced. Some have noted cases where dietary protein failed to prevent or improve kwashiorkor. This suggests that protein deficiency may only be part of the picture. The primary factors associated with kwashiorkor are: Diet of mostly carbohydrates. In populations that are considered high-risk, particularly poorer regions of Africa, Central America and Southeast Asia, often the only available food is a type of carbohydrate: rice, corn or starchy vegetables. These crops tend to be cheaper and more abundant than protein-rich foods, especially in rural areas where many are farmers. Mothers who are protein deprived may pass their deficiency on to their children. Weaning with inadequate food replacement. The name “kwashiorkor” comes from the Ga language of Ghana, Africa, meaning "the sickness the baby gets when the new baby comes." This describes a common condition in which a nursing toddler is rapidly weaned so that a new baby can begin breastfeeding. Due to a scarcity of resources or ignorance of nutrition, or both, the weaning toddler doesn’t receive an adequate replacement diet, and their nutrition deteriorates. Other factors that may contribute include: Lack of essential vitamins and minerals. Lack of dietary antioxidants. Aflatoxins — toxins from a mold that commonly grows on crops in hot and humid climates. Parasites and infectious diseases, particularly measles, malaria and HIV. Significant life stress, including famine, deprivation, war and natural disasters. DIAGNOSIS AND TESTS How is kwashiorkor diagnosed? Healthcare providers can often diagnose kwashiorkor by physically examining the child and observing its telltale physical signs. They will ask about the child’s diet and history of illnesses or infections. They may measure the child’s weight-to-height ratio and height-toage and score them according to various charts. The weight-toheight score tells them how severe the child’s condition is. Their height-to-age score tells them how much the child's growth has been affected by malnutrition. MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT How is kwashiorkor treated? The World Health Organization has outlined 10 steps to follow when treating severe undernutrition: 1. Treat/prevent hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia can occur when calories are introduced. The rehydration formula for malnourished people includes glucose to help restore balance. It’s given incrementally during the first hours of treatment. 2. Treat/prevent hypothermia. Malnourished bodies have trouble regulating their own temperature, so they must be kept warm. 3. Treat/prevent dehydration. A special formula called RESOMAL (REhydration SOlution for MALnutrition) is given to treat dehydration in kwashiorkor. It’s designed to restore and maintain the body’s fluid/sodium balance. It can be given orally or through a tube. 4. Correct electrolyte imbalances. Electrolyte imbalances can have serious and even life-threatening effects, especially when a malnourished person begins refeeding. Healthcare providers try to address these first, usually in their rehydration formula. 5. Treat/prevent infection. With the diminished immune system that comes with kwashiorkor, all infections are serious threats to recovery. Infections are treated with antibiotics. 6. Correct micronutrient deficiencies. Specific vitamin and mineral deficiencies can have serious effects if they are severe enough. Healthcare providers try to correct these before refeeding. 7. Start cautious feeding. Undernourished bodies have altered metabolism. Refeeding will trigger their metabolism to change again. But if this happens too fast, it can cause life-threatening complications (refeeding syndrome). Feeding begins slowly under close observation. Protein, in particular, should be reintroduced gradually in kwashiorkor. 8. Achieve catch-up growth. Once the child has stabilized and appears to be tolerating refeeding well, their calories can increase to up to 140% of recommended values for their age. The WHO provides ready-made liquid formulas that can be given orally or by tube if necessary. This is the nutritional rehabilitation stage of treatment. It may last up to six weeks. 9. Provide sensory stimulation and emotional support. Children with kwashiorkor may have been in a state of apathy for some time. Their malnutrition may have stunted their intellectual, neurological and social development. Stimulating their development to reboot is part of their treatment plan. Ideally, healthcare providers will include the child’s mother in this project. 10. Prepare for follow-up after recovery. Before discharging the child from care, healthcare providers offer education and counseling to the mother regarding nutrition, breastfeeding, food and water hygiene and disease prevention. They may provide immunizations as necessary. If possible, they should help secure access to a consistent, nutritious food supply. PREVENTION How can kwashiorkor be prevented? Education. Some populations simply aren’t informed of basic nutrition, the benefits of breastfeeding or the nutritional needs of children and mothers. Nutritional support. The WHO and other organizations are working to reintroduce native crops that offer sources of protein and micronutrients in affected countries. They have developed nutritional formulas made from locally available resources, such as skim milk and peanuts. Disease control. Widespread diseases and infections weaken the immunity of high-risk populations. Diseased bodies require more nutritional resources and could shed calories through chronic diarrhea. Diseases also deplete a community’s material resources, breeding poverty. Improved sanitation and immunizations can go a long way toward preventing malnutrition. OUTLOOK / PROGNOSIS What is the prognosis for people with kwashiorkor? Left untreated, kwashiorkor can be fatal. Death may be caused by infection, dehydration or liver failure. When treatment begins, people are also at high risk of complications from refeeding syndrome. However, those who are successfully rehabilitated can make a strong recovery. They may have some lingering effects from kwashiorkor, but they may not. The complications of kwashiorkor are more severe and last longer the longer they’ve been left untreated. Some children may never fully recover from their growth and development shortages. They may remain predisposed to liver disease and pancreatic insufficiency. Earlier intervention leads to better outcomes. A note from Cleveland Clinic Kwashiorkor may not look like malnutrition because it causes swelling and bloating. It also comes with hidden side effects that may be unexpected, such as loss of appetite and fatty liver disease. Kwashiorkor needs to be understood to be treated effectively. Simply feeding with protein may be insufficient and even dangerous. But kwashiorkor should be treated as soon as possible, especially in children. Earlier intervention can help minimize the long-term effects of malnutrition. Marasmus Marasmus is severe undernutrition — a deficiency in all the macronutrients that the body requires to function, including carbohydrates, protein and fats. Marasmus causes visible wasting of fat and muscle under the skin, giving bodies an emaciated appearance. It causes stunted growth in children. What is marasmus? Marasmus is a severe form of malnutrition — specifically, proteinenergy undernutrition. It results from an overall lack of calories. Marasmus is a deficiency of all macronutrients: carbohydrates, fats, and protein. If you have marasmus, you lack the fuel necessary to maintain normal body functions. People with marasmus are visibly depleted, severely underweight and emaciated. Children may be stunted in size and development. Prolonged marasmus leads to starvation. What is the difference between marasmus and kwashiorkor? Marasmus and kwashiorkor are two different variations of severe protein-energy undernutrition. Marasmus is a deficiency of all macronutrients, while kwashiorkor is a deficiency in protein predominantly. Kwashiorkor occurs in people who may have access to carbohydrates — bread, grains or starches — but lack protein in their diet. Marasmus has a wasted and shriveled appearance, while kwashiorkor is known for causing edema — swelling with fluid, especially in the belly and the face. Who does marasmus affect? Marasmus can affect anyone who lacks overall nutrition, but it particularly affects children, especially infants, who require more calories to support their growing bodies. It is more common in developing countries with widespread poverty and food scarcity, and where parasites and infectious diseases may contribute to calorie depletion. In the developed world, elderly people in nursing homes and hospitals or who live alone with few resources are more at risk. What happens to the body in marasmus disease? When the body is deprived of energy from food, it begins to feed on its own tissues — first adipose tissue (body fat) and then muscle. It also begins shutting down some of its functions to conserve energy. Cardiac activity slows down, causing low heart rate, low blood pressure and low body temperature. In some cases, this leads to heart failure. The immune system is also compromised, making undernourished people more prone to infection and illness and slower to recover. Children with chronic marasmus will not have the physical resources to grow and develop as they should. They may be stunted in size or have developmental delays or intellectual disabilities. These effects can be lasting, even in children who receive treatment. Parts of the digestive system also begin to atrophy from the lack of use. This means that even when people do have food to eat, they might not be able to absorb nutrition from their food effectively. Ironically, marasmus can lead to food aversion. SYMPTOMS AND CAUSES What are the main causes of marasmus? The main causes affecting all ages include: Poverty and food scarcity. Wasting diseases such as AIDS. Infections that cause chronic diarrhea. Anorexia. Additional causes affecting children include: Inadequate breastfeeding or early weaning of infants. Child abuse/neglect. Additional causes affecting adults include: Dementia. Elder abuse/neglect. What are the external signs of marasmus? Visible wasting of fat and muscle. Prominent skeleton. Head appears large for the body. Face may appear old and wizened. Dry, loose skin (skin atrophy). Dry, brittle hair or hair loss. Sunken fontanelles in infants. Lethargy, apathy and weakness. Weight loss of more than 40%. BMI below 16. What other symptoms and complications can marasmus cause? Dehydration. Electrolyte imbalances. Low blood pressure. Slow heart rate. Low body temperature. Gastrointestinal malabsorption. Stunted growth. Developmental delays. Anemia. Osteomalacia or rickets. DIAGNOSIS AND TESTS How is marasmus diagnosed? Healthcare providers will begin by physically examining the person’s body. Marasmus has some telltale physical features, the primary one being the visible wasting of fat and muscle. People with marasmus appear emaciated. The loss of fat and muscle under the skin may cause the skin to hang loose in folds. Beyond appearances, healthcare providers will measure the height or length of the person’s body and the circumference of their upper arm. Healthcare providers use a few different charts to measure a child’s or adult’s weight-to-height ratio against medical standards, depending on their age. Marasmus is defined differently on different charts, but it is always significantly below average. To use a chart more people are familiar with, marasmus would score below a 16 on the BMI (body mass index). The purpose of the scoring is mostly to confirm the diagnosis and rate how severe it is. What tests are used to diagnose marasmus? Diagnosis primarily relies on body measurements, which are then scored according to different scoring systems for children and adults. Upper arm circumference and height-to-weight ratios help healthcare providers rate the severity of undernutrition. Height-toage ratios help define growth delays in children. Healthcare providers will usually recognize the type of undernutrition (marasmus) based on physical signs. The next step will be to take a blood test to identify the secondary effects of marasmus, including specific vitamin, mineral, enzyme and electrolyte deficiencies. This will help determine the child’s or adult’s nutritional needs for refeeding. A complete blood count can also help reveal any infections or diseases that may have contributed to or resulted from marasmus. They may check a stool sample for parasites. Infections will need to be treated separately. MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT How is marasmus treated? People in treatment for marasmus are at risk of refeeding syndrome, a life-threatening complication that can result when the undernourished body tries to reboot too fast. For this reason, rehabilitation happens in stages. Ideally, people with marasmus should be treated in a hospital setting, under close medical supervision. Healthcare providers who are trained to anticipate and recognize refeeding syndrome can help prevent or correct it by supplementing missing electrolytes and micronutrients. Stage 1: Rehydration and stabilization The first stage of treatment is focused on treating dehydration, electrolyte imbalances and micronutrient deficiencies to prepare the body for refeeding. In many cases, these can all be treated with one formula, REhydration SOlution for MALnutrition (ReSoMal), given orally or through a nasogastric tube. It's also important to keep the person warm to prevent hypothermia and to treat infections, which compromise their meager energy resources. Depending on the individual, it may take several hours to days before they are considered stable enough to begin refeeding. Stage 2: Nutritional rehabilitation Refeeding begins slowly with liquid formulas that carefully balance carbohydrates, proteins and fats. For inpatients, healthcare providers prefer tube feeding because it allows for gradual but continuous nutrition. Calories are introduced at about 70% of normal recommended values for the person’s age. Eventually, they may increase to 140% of recommended values to meet the growth requirements of stunted children. This phase may last two to six weeks. During this time, patients gradually progress to more ordinary oral feeding with solid foods. Stage 3: Follow-up and prevention Since marasmus can recur, a complete treatment protocol includes education and outgoing support for the patient and/or their caregiver before they are discharged. In the developing world, this may mean breastfeeding support, safe drinking water and food preparation guidelines, immunizations and education to prevent widespread diseases. In the developed world, caregivers may need guidance on how to recognize signs of malnutrition in those they care for. The Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) can help identify people at risk.