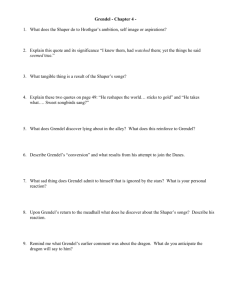

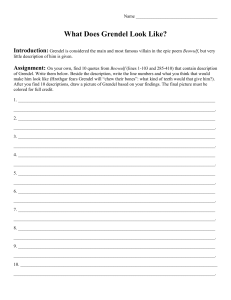

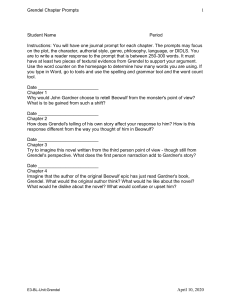

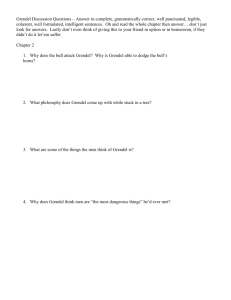

Myth and Monstrosity in John Gardner’s Grendel word count: 4638 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................1 THE DIALECTIC OF ENLIGHTENMENT .......................................................................................2 THE SHAPER OF MYTH ......................................................................................................................4 THE ABSURDIST TEACHER ..............................................................................................................7 THE PERSONIFICATION OF THE STRUGGLE ......................................................................... 10 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................................................... 15 Works Cited ......................................................................................................................................... 18 "I hung balanced, a creature of two minds" (Gardner 110) INTRODUCTION The monster of the story is almost always memorable because it carries a rich signification. As such monsters are integral for understanding the myths that create them. Hence, many adaptions of the Anglo-Saxon epic of Beowulf focus on shifting the idea of its monster Grendel. In the case of John Gardner’s adaption Grendel (1971) the monster is redefined to embody the struggle of humans trying to create order in an inherently chaotic world. To better understand the philosophical field of tension that Grendel is caught in, Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment offers a theory of myth and myth criticism that adequately captures the core conflict of the novel. The Dialectic of Enlightenment can not only help to analyze aesthetic function, but also offer an explanation for Grendel’s liminal position within the framework of the novel. This liminal status is also present in the original epic in which both Grendel and his mother have been read as carrying “alien stories and histories into the safety of the mead hall, unsettling the shared body of knowledge held within reading communities.” (Paz 232). However, Gardner’s version makes this status explicit as it reveals the monster’s mental suffering resulting from his alienation. It will thus be argued that Grendel can be read as a personification of the troubled relation between humanity and nature, because he is presented as a liminal being caught between two opposing ways of understanding the world. Firstly, Adorno and Horkheimer’s critique of myth as instrumental reason will be described to lay the theoretical groundwork for the subsequent analysis of the novel. The analysis is split into three parts and will examine both the Shaper as full acceptance of myth and the dragon as complete rejection of myth. Finally, Grendel is considered as the monster caught between these two poles. THE DIALECTIC OF ENLIGHTENMENT Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment tries to refute the very possibility of myth criticism and thereby calls into question the project of Enlightenment. They argue that “Enlightenment, understood in the widest sense as the advance of thought, has always aimed at liberating human beings from fear and installing them as masters. […] It wanted to dispel myths, to overthrow fantasy with knowledge” (Horkheimer and Adorno 1). Enlightenment’s understanding of myth as uncritical belief which leads to oppressive power relations and their preservation, is diagnosed as illusory since myth and rationality are revealed to be functioning according to the same principle (Cohen 584–85). They are both part of instrumental reason which seeks to learn how to use nature “to dominate wholly both it and human beings” (Horkheimer and Adorno 2). It follows that power and knowledge are understood to be synonymous (ibid. 2), and thus, they deem instrumental reason to be essential for the formation of civilization. In order to ensure self-preservation and limit the fear of an alien nature, instrumental reason inhibits a relationship with nature on the basis of identification. Instead humans pursue the maximization of control accomplished through separation from nature, now seen as the object “knowable” to the human subject (Cohen 585). Just as myth once “sought to report, to name, to tell of origins—but therefore also to narrate, record, explain” (Horkheimer and Adorno 5), rational thought and its abstract categories now operate in the same way to make the new “appear as something predetermined which therefore is really the old” (ibid. 21). The phenomenon can even be observed in the earliest popular epics in which specific rituals and local spirits are replaced by theoretical element alone and thus constitute a hierarchy of significations (e.g. any concept of heaven and its rules) (ibid. 5). As a result of this conceptualization, nature is rendered homogenous, and the actual is subsumed by the given order. Elements of surprise are defused by assigning them a repetitive pattern and thus dangers can be known in advance, producing the illusion of security (Cohen 586). Hence, myth and enlightenment alike assume that phenomena can be identified through their concepts as to make them controllable. However, this control is deceiving and comes with a price. As soon as “the single distinction between man’s own existence and reality swallows up all others” (Horkheimer and Adorno 5), infinite chaos is reduced to the order that is created. All that is unexpected is lost and with it, alternative ways of thinking and being in the world. Furthermore, nature being necessarily identified as the other (the object) in this process of domination, unavoidably forces the self-domination of humans. This is due to “the self as nature” also undergoing the same process of othering, producing a subject confined in the accepted mythical order (Benhabib 75). Hence, on a societal level, oppressive power relations are maintained by the assignment of different classes; There are those in power of defining the limits of the world and those who are fated to obedience (Horkheimer and Adorno 15–16). All the while civilization develops largely unaware of the fact that ultimately, myth’s dividing of nature into appearance and essence is a direct expression of human fear, which serves as its own explanation (ibid. 10). It is this troubled relation between humans and nature that is one of Grendel’s main themes. Reading the novel through the lens of Adorno and Horkheimer’s theory of myth can enable a nuanced interpretation in which neither humanity nor monstrosity is entirely wrong. In fact, as Adriano has argued, Grendel “suggests a dialectic, rather than a dualism, between the all-seeing dragon’s vision of blind mechanistic process in the universe and the blind Shaper’s vision of willfully imposing meaning on the universe through art” (118). The shaper thus represents the full acceptance of mythical thinking as one of the two opposing ways of subjectification presented in the novel and further serves as a showcasing of myth’s generative power. THE SHAPER OF MYTH When Gardner’s Monster first hears human singing, he describes that the song “swells, pushes through woods and sky, and they’re singing now as if by some lunatic theory they had won” (Gardner 14). From Grendel’s perspective, the song is experienced as something invasive, something which “pushes” through nature and thereby displays force. At the same time the act of singing is immediately connected to a pathology of conceptual thinking by hypothesizing the trigger to be a “lunatic theory”. Songs in the novel can be read as signifying conceptual thought or myth in its purest form, explaining the impact the singing has on Grendel. Heorot’s greatest songwriter, and thereby creator of myth, is introduced to the reader as “the Shaper”. The Shaper’s name already points towards a characteristic of the novel which has been explained as characters not merely describing but being living representations of philosophical ideas (Stromme 84). As the representation of a full embrace of mythical ordering, the Shaper truly shapes the world. He is in a position of power in which he can be understood as possessing “magic which defined the limits of that world” (Horkheimer and Adorno 15). Grendel discerns the Shaper’s power almost instantly and observes that he “stares strange-eyed at the mindless world and turns dry sticks to gold.” (Gardner 49). The shaper having impaired vision emphasizes the irrelevancy of the natural phenomena that the mythical meaning is built upon. The Shaper is not a Seer, neither in the metaphorical nor in the actual sense and he does not have to be. His powers and prevalence in the novel have also caused him to be read as a surrogate for the unnamed author of the original epic Beowulf (Hutman 21). Similarly to the author of Beowulf, the Shaper’s reordering makes meaning as he simultaneously produces a narrative. More importantly, they both create heroes in the process. One of the most interesting deviations of Gardner’s adaptation is that installing Grendel as a first-person narrator allows the reader to experience the functioning of mythical thinking from the outside. This creates a transparency that reveals the discrepancy between the concept and the actual. It is especially apparent when comparing Grendel’s perspective of the development of civilizations with the songs of the Shaper. Hrothgar and Heorot in the songs represent the pinnacle of human civilization, analogous to how they are depicted in the original epic (Lacy 56). Yet, Grendel observes that the Danes are often senseless and violent, nothing more but “ragged men fighting each other till the snow was red slush” (Gardner 44). Their morality is presented as arbitrary and bound to power relations and the Shaper’s tale is only sung for “a price” (ibid. 42). Myth thus is instrumental in the course of civilization only to the point of overwriting the past and creating tools for the domination of the present. The Shaper “had torn up the past by its thick, gnarled roots and had transmuted it, and they, who knew the truth, remembered it his way” (ibid. 42). Truth is redefined as an illusory notion, referring to particular acts of mythical remembering. It is exactly this kind of truth that creates the notion of the heroic in the novel and thus brings forth both Beowulf and Unferth as creations of the Shaper. As Hutman observes, the Shaper and Beowulf are connected by their inability to see; the Shaper because of his blindness and Beowulf because of his madness induced by the Shaper’s vision (25). The same madness can be observed in Unferth, who is willing to sacrifice himself for the myth of the hero. What Grendel exposes as meaningless bloodshed to both Unferth and Beowulf is rich in signification. The Shaper as the living representation of mythical thinking is therefore Grendel’s real antagonist and at the same time greatest temptation. Despite having access to the actual beneath the mythical concepts, Grendel is not untouched by the Shaper’s magic. His ambiguous relation to humanity complicates the original epic in which Grendel is merely a savage monster enraged by music. Hence, when the Shaper dies, it affects Grendel in that he falls deeper into nihilism. Stromme identifies this moment as the development of a Nietzschean philosophy due to abandonment (89). While the Shaper’s death is not the sole reason for Grendel adopting this philosophical understanding of the world, it leaves him without a stable identification created by his “vision without seams” (Gardner 49). Grendel thus faces the abyss that myth has concealed (albeit poorly) and rises from it as the existentialist monster. As Gardner himself explained, the monster of this novel was intended to be modelled upon the philosophy of JeanPaul Sartre (Stromme 83). Within the framework of Adorno and Horkheimer’s theory, Grendel’s struggle with nihilism can be interpreted as an expression of the vulnerability of the human condition. This is brought about by Grendel’s awareness that myth is both arbitrary and misleading, yet also an inescapable tool of domination and control. THE ABSURDIST TEACHER It would seem obvious to conclude that the monster of the novel also represents the opposing world view to that of the Shaper, however, this would certainly lead to an oversimplification of Grendel’s internal struggle and unjustly downplay the role of the dragon. Since the dragon is able to see both past and present, “all time, all space” (Gardner 62–63), he can easily see beyond mythical meaning and perceive the actual in its entirety. He tries to share that wisdom with Grendel and he acts as an intense influence on Grendel’s understanding of the world. Despite the dragon acting as a teacher, Grendel identifies him as “not a friend” (ibid. 12) early on in the novel. This is not only due to their distinct power dynamic, with the dragon being characterized as a higher being, but also because his teachings are painful. During their conversation, the dragon questions the concept of causation and exposes the workings of myth. He thereby confirms Grendel’s suspicions and installs his cynicism. The dragon, thus, truly is the Shaper’s antagonist in the realm of philosophy with Grendel being caught in the middle. The two monsters are able to observe humans from the outside and recognize them as “Counters, measurers, theory-makers” (ibid. 64). Instead of this being perceived as something admirable, the dragon comments: “They only think they think. No total vision, total system, merely schemes with vague family resemblance, no more identity than bridges and, say, spiderwebs. But they rush across chasms on spiderwebs, and sometimes they make it, and that, they think, settles that!” (ibid. 64) He thus exposes that instead of being on a journey towards enlightenment, humanity is merely using instrumental rationality for their own self-preservation. A pathetic makeshift framework giving the illusion of control that should ideally remain unquestioned. He further analyses the Shaper’s function as that of keeping the mythical vision seamless and preventing said questioning. Human “of course, from time to time; have uneasy feelings that all they live by is nonsense.”(ibid. 64– 65), so they do need the illusion of the Shaper to ensure control and stability. By assigning repetitive patterns and smoothing everything into a connected narrative, the chaos of the actual is suppressed and civilization can march onwards in blissful ignorance. Beyond these findings, the dragon, as a meta-ethical observer, also discloses to Grendel what his role in this system really is: “You improve them, my boy! Can’t you see that yourself? You stimulate them! You make them think and scheme. You drive them to poetry, science, religion, all that makes them what they are for as long as they last. You are so to speak, the brute existent by which they learn to define themselves. […] If you withdraw, you’ll instantly be replaced.” (ibid. 72) Grendel from the perspective of human civilization stands in for nature, more specifically what remains fear-inducing and uncontrollable in nature. In this, he stimulates them to develop instrumental rationality. Like Adorno and Horkheimer’s analysis of myth and enlightenment, the dragon regards religion, poetry, and science as essentially the same. He is also aware that humanity purchases “the increase in their power with estrangement from that over which it is exerted” (Horkheimer and Adorno 6). Thus, in trying to control nature, they inadvertently define themselves against it and create a monster. This principle underlies all their conceptual thinking and Grendel necessarily would be replaced by the next fear-inducing object they strive to dominate. Instead of adhering to the common view that monsters allow man to transcend themselves, the dragon introduces a critical voice, exposing the concept of monstrosity as nothing but a stabilizing element within the deceptive workings of myth. Unfortunately, despite the wisdom of the dragon, Grendel does not have the privilege of remaining at a comfortable intellectual distance to civilization. In the original epic, both monsters do not show any clear signs of intellect and are not contrasted against or influenced by each other. However, in Gardner’s adaption their relationship is important as it reveals Grendel as a liminal being only defined by difference. The discussions between the two only provide Grendel with momentary satisfaction (Milosh and Gardner 50). Ultimately, his reality is not the same as that of the dragon. As the dragon himself notes: “You’ll never know. It must be very frustrating to be caged like a Chinaman’s cricket in a limited mind” (Gardner 72). Grendel’s limited mind places him somewhere in between the dragon and the Shaper. He cannot fully attain the level of consciousness of the dragon and is vulnerable to the manipulation of the Shaper, yet he knows that myth does not present a real solution. Moreover, Grendel resides in the liminal space between the human world of myth and order, and that of nature and chaos. This is his misery and explains why both the dragon’s wisdom (“doom became a smell in the air”(ibid. 75) and the Shaper’s song (“I gnashed my teeth and clutched the sides of my head as if to heal the split, but I couldn’t” (ibid. 44) are experienced as a curse. THE PERSONIFICATION OF THE STRUGGLE The monsters created in storytelling can always be read as signifiers for an underlying crisis of orientation (Coles 179). This certainly holds true for the epic which conveys the growing influence of Christian faith contrasted with “regret for the pagan past” (ibid. 183). Accordingly, Grendel attacking the Mead Hall stands in for anxiety concerning Heorot’s social fabric, material security but also the reassurance of a worldview that is housed there (ibid. 189). In Gardner’s adaption, instead of signifying the replacement of one temporary myth by another, the monster personifies the crisis of orientation as a constant of the human condition. Grendel’s awareness of the fraudulent nature of instrumental rationality leads him to grapple with nihilism. His existentialism is nothing but an attempt to answer the question of life’s meaning posed by nihilism. In sharp contrast to the original Grendel, who shows no signs of reflection, Gardner’s monster is a feeling and thinking being who fights an internal battle that neither the civilization of Heorot nor the dragon really have an adequate solution for. In line with Sartrean philosophy, Grendel realizes that he alone exists and that all the rest is “merely what pushes me, or what I push against, blindly – blindly as all that is not myself pushes back” (Gardner 22). Blindness as a theme of the novel, yet again indicates the impossibility of grasping the actual and gaining real orientation or enlightenment. Rules are understood as something that comes as an afterthought to the forces of existence that push against one another. Moreover, this realization is not just a philosophical statement, but also embodied by Grendel’s pervasive loneliness. He cannot identify himself with any other existence he encounters, not even his own mother, who he is unable to communicate with. Grendel’s only option of self-definition is through difference as there is no other creature like him (Andriano 114). Therefore, when Grendel asserts that he has become something, he remarks: “I had hung between possibilities before, between the cold truths I knew and the heart-sucking conjuring tricks of the Shaper; now that was passed: I was Grendel, Ruiner of Meadhalls, Wrecker of Kings! But also, as never before, I was alone.” (Gardner 80). His solution is to affirm difference and use the Hrothgar’s kingdom as a backdrop to his identity, yet he immediately pays the price in the form of further estrangement and isolation. Contradictory to what one might expect, Grendel’s only real attempt at producing a stable orientation leads to him feeling alone like “never before”. At the same time, Grendel is never naïve about the arbitrary and temporary character of his identity. He poses the rhetorical question himself: “What will we call the Hrothgar-Wrecker when Hrothgar has been wrecked?” (ibid. 91). The downfall of Hrothgar’s kingdom would throw Grendel into nihilism again, perceived as even worse than his makeshift identity as a lonely being. It is this astuteness in observing the absurdity of his newfound identity coupled with his loneliness that enables the monster to be read as “a sympathetic and reliable narrator” (Merrill 165). The troubled protagonist, although clearly not human, stands in for the crisis between humans as controlling subjects and nature as the fear-inducing object which needs to be overcome through a stable narrative. Belonging to neither the natural nor the human side of the divide, also retains the original ambiguity of the monster in the epic. His physical appearance is never described in detail other than subtle indications such as Grendel being “wretched shape […] in the form of a man, except that he was bigger than any other man” (Donaldson 24). Gardner’s monster is aware of his status as nothing that would be particularly “more noble” than nature (Gardner 6). Swinford similarly reads Grendel as “not only a character passing through the woods; he is also a natural force” (326). His numerous encounters with animals throughout the novel also help establishing Grendel as a hybrid creature “stuck between the human and animal worlds” (Swinford 327) By virtue of partly belonging to the realm of the natural, Grendel’s perspective gives insight into the relation between humans and nature. When he is first discovered by humans, while stuck in a tree, one of the warriors mistakes him as “a growth of some kind […] some beastlike fungus.”(Gardner 24). Not much later, they are convinced he must be an angry spirit instead. Yet, their responses do not differ in regard to what they are supposed to attain: control over either nature or a natural spirit via instrumental rationality that specifies the correct measures to be taken. Their encounter finally ends in Grendel’s failed attempt at communicating, leading to him being attacked by the warriors and suffering as a breathing example of the shortcomings of mythical thinking. The same perverse relationship of humans mastering nature is presented through Grendel observing the advancement of civilization, along with descriptions of deforestation, wars and animal suffering. Hrothgar’s people are presented as “animals in denials of their beastly nature” (Swinford 331) instead of the pinnacle of progressive culture. While the original epic obviously adopts a different perspective, this struggle for the domination of nature in the sense of the Dialectic of Enlightenment applies to this version of the fight against Grendel too. Both Grendel and his mother are representations of what remains chaotic and unreadable in nature and thus threaten the stability of the mythical framework. Through storytelling, monstrosity is supposed to be made explainable, as any sense of “outside” the mythical system is the real source of fear (Horkheimer and Adorno 11). Gardner’s version transfers this conflict into a more modern context, capturing the rise of existentialist philosophy at the time, thereby producing a critique of mankind through the monster. This is neither natural nor human and questions the power of myth. Nevertheless, Gardner’s Grendel cannot help but yearn for the myths to be true. Throughout the novel he readily seems to wonder: “Why can’t I have someone to talk to?”(Gardner 53). Grendel being caught between nature and humanity prohibits him from really connecting with anyone. This is intensified by the two philosophical perspectives he is split between. Throughout the novel, he does not have conversation partners that understand his struggle. The dragon and his complete rejection of mythical order has the privilege of transcending the realm of human consciousness completely, and thereby adopts a rather patronizing tone with Grendel. Unferth as the Shaper’s creation cannot relate to Grendel as he completely caught within mythical thinking. What Grendel witnesses in his continuous attempts to communicate with Hrothgar’s people is that his critical reading of myth leads to estrangement from one’s society due to inhibiting the participation in meaning-making processes. Tragically, he does not have the option of accepting the myth as truth anymore. Even in admiring the Shaper’s song, he cannot forget about the actual that they conceal: “my mind aswim in ringing phrases, magnificent, golden, and all of them, incredibly, lies” (ibid. 43). The self-conscious monster is aware of the tragic of his situation. He admits to himself that he wishes for the Shaper’s story of divine creation to be true, despite it rendering him the outcast “cursed by the rules of his hideous fable” (Gardner 55). Grendel’s rift becomes so intense even that he considers killing himself, before he changes his mind in the next instance “for no particular reason” (ibid. 110). In contrast with those finding their places within the mythical framework, Grendel’s life seems to be nothing but suffering and questioning, as if myth provides for those who naively accept it (Payne 62). Upon seeing Beowulf, as the true hero of the ordered world Grendel, for the first time, observes that his body seems “a disguise for something infinitely more terrible” (Gardner 155). What Grendel senses has been described as the “mythical pattern itself” that brought Beowulf into existence (Payne 64). The fight with Grendel then can also be read as myth fighting to homogenize all that is left chaotic and uncontrollable. Throughout the fight, it appears as if Beowulf draws his powers from his faith in mythical continuity and is close to imposing his philosophical perspective onto the monster, who is resisting by jerking his head “trying to drive out illusion” (Gardner 169). Nevertheless, even while losing the fight Grendel does not lose his skepticism and is able to maintain what he deems his “sanity” (ibid. 169). Regardless of Beowulf contesting the claims of the dragon and defeating him, Grendel does not surrender to myth. Reasserting that Beowulf “penetrated no mysteries” and Beowulf being able to tear off his arm can only be explained by the “mere logic of chance” (ibid. 172-173). Grendel escapes into the forest. Even in dying there is no end to Grendel’s mental suffering and no closure for his philosophical quest. CONCLUSION Myth as an installment of power has been shown to be a pervasive theme throughout the novel. Mythical thinking understood in the sense of Adorno and Horkheimer’s concept of instrumental reason, reveals the Shaper’s importance, the dragon’s analysis and Grendel’s struggle as all relating back to humanity’s need to dominate nature. The narration of the novel can thus be read as illustrating Adorno and Horkheimer’s hypothesis. Humans are depicted as relying on repetitive patterns to reduce the chaos of the actual and establish control through ordering. However, neither humans nor monster are entirely wrong. Civilization is shown to need the self-domination that myth is based upon to avoid fear. The Shaper as its blind creator acts as an illustration of how effective myth is without bringing about true emancipation or enlightenment. As societal domination becomes harder to recognize the more sophisticated the domination of nature is (Horkheimer and Adorno 77), the people of Heorot seem to be completely blinded by the Shaper. It is Grendel as the outsider, who throughout the novel provides a critical perspective and understands that the task of culture is to “establish identity of the self in view of otherness” with instrumental rationality being the means by which to accomplish it (Benhabib 77–78). However, he does not attain these insights without help, but is introduced to this perspective through the dragon as his absurdist teacher. It is this divide between the Shaper with the heroes that he creates and the dragon as myth’s worst critic that Grendel is caught in between. Furthermore, Grendel is continuously read by Hrothgar’s people as part of uncontrollable nature and oscillates between the planes of wilderness and civilization. His Existentialism is therefore developed as a reaction to being caught in a liminal space between both myth and chaos and nature and humanity. The only form of self-identification available to Grendel is via difference, he cannot be integrated into a clear philosophical world view, nor a mode of existence. He remains a breathing example of the shortcomings of instrumental reason and the danger of nihilism that lurks when one tries to cut ties with myth. While Grendel is intended to be the existentialist villain, he can easily be read as a tragic and sympathetic character at war with a pathological society. Loneliness and reflectivity make Grendel a somewhat sympathetic narrator and complicates the status of monstrosity, as something which is frustrated with the established order. The novel offers readers the opportunity to see their “own inquiring minds through Grendel’s” (Milosh and Gardner 57). Hence, Gardner’s adaption retains prominent themes of the original epic such as the power of storytelling and the clash between civilization and nature, but through his protagonist makes visible the chasms that myth works to conceal. While Adorno believed that affinity without identity and difference without domination could exist, Grendel’s experiences deprived him of perceiving any lifeaffirming alternatives. Ultimately, unmasking the “dark realities” beneath all mythical order proved to be an undertaking that Grendel was never able to recover from, as he remained caught in the liminal space between “the self and the world – two snake pits” (Gardner 157). Works Cited Andriano, Joseph. Immortal Monster : The Mythological Evolution of the Fantastic Beast in Modern Fiction and Film. Greenwood Press, 1999, p. 179. Benhabib, Seyla. “The Critique of Instrumental Reason.” Mapping Ideology, edited by Slavoj Žižek, Verso, 2012, pp. 66–92. Cohen, Avner. “Myth and Myth Criticism Following the Dialectic of Enlightenment.” European Legacy, vol. 15, no. 5, 2010, pp. 583–98, doi:10.1080/10848770.2010.501660. Coles, Pamela. “Necessary Monsters: A General Theory about the Global Impulse to Monster-Make.” ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 2008, http://ezproxy.net.ucf.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/8 62994527?accountid=10003%5Cnhttp://sfx.fcla.edu/ucf?url_ver=Z39.882004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&genre=dissertations+&+ theses&sid=ProQ:ProQuest+Dissertations+&+T. Donaldson, E. Talbot. Beowulf - A Prose Translation. Edited by Nicholas Howe, Norton & Company, 2002. Gardner, John. Grendel. Vintage Books, 1971. Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. “The Concept of Enlightenment.” Dialectic of Enlightenment, 2020, pp. 1–34, doi:10.1515/9780804788090-004. Hutman, Norma L. “Even Mothers Have Monsters : A Study of Beowulf and John Gardner’s Grendel.” Mosaic, vol. 9, no. 1, 1975, pp. 1–14. Lacy, Jefferson C. Monsters We Become: The Development of the Inhuman Narrative Voice. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2006, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.050. Merrill, Robert. “John Gardner’s Grendel and the Interpretation of Modern Fables.” American Literature, vol. 56, no. 2, JSTOR, May 1984, p. 162, doi:10.2307/2925751. Milosh, Joseph, and John Gardner. “John Gardner’s ‘Grendel’: Sources and Analogues.” Contemporary Literature, vol. 19, no. 1, 1978, pp. 48–57. Payne, Craig. “The Cycle of the Zodiac in John Gardener ’ s Grendel.” Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature, vol. 18, no. 4, 1992, pp. 61–65. Paz, James. “Æschere’s Head, Grendel’s Mother, and the Sword That Isn’t a Sword: Unreadable Things in Beowulf.” Exemplaria, vol. 25, no. 3, 2013, pp. 231–51, doi:10.1179/1041257313Z.00000000033. Stromme, Craig J. “The Twelve Chapters of Grendel.” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, vol. 20, no. 1, Routledge, Oct. 1978, pp. 83–92, doi:10.1080/00111619.1978.10690184. Swinford, Dean. “Some Beastlike Fungus: The Natural and Animal in John Gardner’s Grendel.” LIT Literature Interpretation Theory, vol. 22, no. 4, 2011, pp. 323–35, doi:10.1080/10436928.2011.622689.