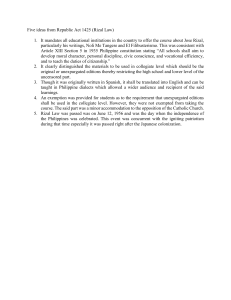

The Importance of the Jose Rizal Subject THE RIZAL BILL was as controversial as Jose Rizal himself. The mandatory Rizal subject in the Philippines was the upshot of this bill which later became law in 1956. The bill involves mandating educational institutions in the country to offer a course on the hero’s life, works, and writings, especially the ‘Noli Me Tangere’ and ‘El Filibusterismo’. The transition from being a bill to become a republic act was however not easy as the proposal was met with intense opposition particularly from the Catholic Church. Largely because of the issue, the then-senator Claro M. Recto—the main proponent of the Rizal Bill—was even dubbed as a communist and an anti-Catholic. Catholic schools threatened to stop operation if the bill was passed, though Recto calmly countered the threat, stating that if that happened, then the schools would be nationalized. Afterward threatened to be punished in future elections, Recto remained undeterred. Concerning the suggestion to use instead of the expurgated (edited) version of Rizal’s novels as mandatory readings, Recto explained his firm support for the unexpurgated version, exclaiming: “The people who would eliminate the books of Rizal from the schools would blot out from our minds the memory of the national hero. This is not a fight against Recto but a fight against Rizal.” (Ocampo, 2012, p. 23) The bill was eventually passed, but with a clause that would allow exemptions to students who think that reading the Noli and Fili would ruin their faith. In other words, one can apply to the Department of Education for exemption from reading Rizal’s novels —though not from taking the Rizal subject. The bill was enacted on June 12, 1956. RA 1425 and other Rizal laws The Rizal Bill became the Republic Act No. 1425, known as the ‘Rizal Law’. The full name of the law is “An Act to Include in the Curricula of All Public and Private Schools, Colleges and Universities Courses on the Life, Works and Writings of Jose Rizal, Particularly His Novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, Authorizing the Printing and Distribution Thereof, and for Other Purposes.“ The first section of the law concerns mandating the students to read Rizal’s novels. The last two sections involve making Rizal’s writings accessible to the general public—they require the schools to have a sufficient number of copies in their libraries and mandate the publication of the works in major Philippine languages. Jose P. Laurel, then-senator who co-wrote the law, explained that since Jose Rizal was the founder of the country’s nationalism and had significantly contributed to the current condition of the nation, it is only right that Filipinos, especially the youth, know about and learn to imbibe the great ideals for which the hero died. Accordingly, the Rizal Law aims to accomplish the following goals: 1. To rededicate the lives of youth to the ideals of freedom and nationalism, for which our heroes lived and died 2. To pay tribute to our national hero for devoting his life and works in shaping the Filipino character 3. To gain an inspiring source of patriotism through the study of Rizal’s life, works, and writings. So far, no student has yet officially applied for exemption from reading Rizal’s novels. Correspondingly, former President Fidel V. Ramos in 1994, through Memorandum Order No. 247, directed the Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports and the Chairman of the Commission on Higher Education to fully implement the RA 1425 as there had been reports that the law had still not been totally carried out. In 1995, CHED Memorandum No. 3 was issued enforcing strict compliance to Memorandum Order No. 247. Not known to many, there is another republic act that concerns the national hero. Republic Act No. 229 is an act prohibiting cockfighting, horse racing, and jai-alai on the thirtieth day of December of each year and to create a committee to take charge of the proper celebration of Rizal day in every municipality and chartered city, and for other purposes. The Importance of Studying Rizal The academic subject on the life, works, and writings of Jose Rizal was not mandated by law for anything. Far from being impractical, the course interestingly offers many benefits that some contemporary academicians declare that the subject, especially when taught properly, is more beneficial than many subjects in various curricula. The following are just some of the significance of the academic subject: 1. The subject provides insights on how to deal with current problems There is a dictum, “He who controls the past controls the future.” Our view of history forms the manner we perceive the present, and therefore influences the kind of solutions we provide for existing problems. Jose Rizal course, as a history subject, is full of historical information from which one could base his decisions in life. In various ways, the subject, for instance, teaches that being educated is a vital ingredient for a person or country to be really free and successful. 2. It helps us understand better ourselves as Filipinos The past helps us understand who we are. We comprehensively define ourselves not only in terms of where we are going, but also where we come from. Our heredity, past behaviors, and old habits as a nation are all significant clues and determinants to our present situation. Interestingly, the life of a very important national historical figure like Jose Rizal contributes much to shedding light on our collective experience and identity as Filipino. The good grasp of the past offered by this subject would help us in dealing wisely with the present. 3. It teaches nationalism and patriotism Nationalism involves the desire to attain freedom and political independence, especially by a country under foreign power, while patriotism denotes proud devotion and loyalty to one’s nation. Jose Rizal’s life, works, and writings—especially his novels—essentially, if not perfectly, radiate these traits. For one thing, the subject helps us to understand our country better. 4. It provides various essential life lessons We can learn much from the way Rizal faced various challenges in life. As a controversial figure in his time, he encountered serious dilemmas and predicaments but responded decently and highmindedly. Through the crucial decisions he made in his life, we can sense his priorities and convictions which manifest how noble, selfless, and great the national hero was. For example, his many resolutions exemplified the aphorism that in this life there are things more important than personal feeling and happiness. 5. It helps in developing logical and critical thinking Critical Thinking refers to discerning, evaluative, and analytical thinking. A Philosophy major, Jose Rizal unsurprisingly demonstrated his critical thinking skills in his argumentative essays, satires, novels, speeches, and written debates. In deciding what to believe or do, Rizal also proved his being a reasonably reflective thinker, never succumbing to the irrational whims and baseless opinions of anyone. In fact, he indiscriminately evaluated and criticized even the doctrines of the dominant religion of his time. A course on Rizal’s life, works, and writings, therefore, is also a lesson in critical thinking. 6. Rizal can serve as a worthwhile model and inspiration to every Filipino If one is looking for someone to imitate, then Rizal is a very viable choice. The hero’s philosophies, life principles, convictions, thoughts, ideals, aspirations, and dreams are a good influence to anyone. Throughout his life, he valued nationalism and patriotism, respect for parents, love for siblings, and loyalty to friends, and maintained a sense of chivalry. As a man of education, he highly regarded academic excellence, logical and critical thinking, philosophical and scientific inquiry, linguistic study, and cultural research. As a person, he manifested versatility and flexibility while sustaining a strong sense of moral uprightness. 7. The subject is a rich source of entertaining narratives People love fiction and are even willing to spend on books or movie tickets just to be entertained by made-up tales. But only a few perhaps know that Rizal’s life is full of fascinating non-fictional accounts. For instance, it is rarely known that (1) Rizal was involved in a love triangle with Antonio Luna as also part of the romantic equation; (2) Rizal was a model in some of Juan Luna’s paintings; (3) Rizal’s common-law wife Josephine Bracken was ‘remarried’ to a man from Cebu and had tutored former President Sergio Osmeña; (4) Leonor Rivera (‘Maria Clara’), Rizal’s ‘true love’, had a son who married the sister of the former President of the United Nations General Assembly Carlos P. Romulo; (5) the Filipina beauty queen Gemma Cruz Araneta is a descendant of Rizal’s sister, Maria; (6) the sportscaster Chino Trinidad is a descendant of Rizal’s ‘first love’ (Segunda Katigbak); and (7) the original manuscripts of Rizal’s novel (Noli and Fili) were once stolen for ransom, but Alejandro Roces had retrieved them without paying even a single centavo. Lesson 1: Introduction of R. A 1425 (Rizal Law) Laws on Rizal There are at least two Republic Acts and two Memorandum Orders pertaining to Jose Rizal: Republic Act N. 1425 or the Rizal Law Republic Act No. 229 or the Celebration of Rizal Day’ Memorandum Order No. 247 by President Fidel V. Ramos CHED Memorandum No. 3, s 1995 by Commissioner Mona D. Valismo. Introduction about the Rizal Law Republic Act 1425: Rizal Law was authored by Senator Claro M. Recto It was signed by President Ramon Magsaysay on June 12, 1956 It requires the implementation of the Rizal course as a requirement for graduation in all non-degree and degree courses in the tertiary education It includes the life, works, and writings of Jose Rizal, particularly his novels, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo. On August 16, 1956, the Rizal Law took effect Aims of Rizal Law Recognize the relevance of Jose Rizal ideas, thoughts, teaching, and life-values to present conditions in the community and country and apply them in the solution to day to day situations and problems of contemporary life. Develop an understanding and appreciation of the qualities, behavior, and character of Rizal and thus foster the development of moral character and personal discipline. The goals set by the Board on National Education (Capino et.al, 1997) Recognize the relevance of Rizal’s ideas, thoughts, teachings, and life values to present conditions in the Community; Apply Rizal’s ideas in the solution of day-to-day situations and problems in contemporary life; Develop an understanding and appreciation of the qualities and behavior and character of Rizal; and Forster development of moral character, personal discipline, citizenship, and vocational efficiency among the Filipino Youth. REPUBLIC ACT NO. 1425 AN ACT TO INCLUDE IN THE CURRICULA OF ALL PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SCHOOLS, COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES COURSES ON THE LIFE, WORKS AND WRITINGS OF JOSE RIZAL, PARTICULARLY HIS NOVELS NOLI ME TANGERE AND EL FILIBUSTERISMO, AUTHORIZING THE PRINTING AND DISTRIBUTION THEREOF, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES WHEREAS, today, more than any other period of our history, there is a need for a re-dedication to the ideals of freedom and nationalism for which our heroes lived and died; WHEREAS, it is meet that in honoring them, particularly the national hero and patriot, Jose Rizal, we remember with special fondness and devotion their lives and works that have shaped the national character; WHEREAS, the life, works and writing of Jose Rizal, particularly his novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, are a constant and inspiring source of patriotism with which the minds of the youth, especially during their formative and decisive years in school, should be suffused; WHEREAS, all educational institutions are under the supervision of, and subject to regulation by the State, and all schools are enjoined to develop moral character, personal discipline, civic conscience and to teach the duties of citizenship; Now, therefore, SECTION 1. Courses on the life, works and writings of Jose Rizal, particularly his novel Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, shall be included in the curricula of all schools, colleges and universities, public or private: Provided, That in the collegiate courses, the original or unexpurgated editions of the Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo or their English translation shall be used as basic texts. The Board of National Education is hereby authorized and directed to adopt forthwith measures to implement and carry out the provisions of this Section, including the writing and printing of appropriate primers, readers and textbooks. The Board shall, within sixty (60) days from the effectivity of this Act, promulgate rules and regulations, including those of a disciplinary nature, to carry out and enforce the provisions of this Act. The Board shall promulgate rules and regulations providing for the exemption of students for reasons of religious belief stated in a sworn written statement, from the requirement of the provision contained in the second part of the first paragraph of this section; but not from taking the course provided for in the first part of said paragraph. Said rules and regulations shall take effect thirty (30) days after their publication in the Official Gazette. SECTION 2. It shall be obligatory on all schools, colleges and universities to keep in their libraries an adequate number of copies of the original and unexpurgated editions of the Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, as well as of Rizal’s other works and biography. The said unexpurgated editions of the Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo or their translations in English as well as other writings of Rizal shall be included in the list of approved books for required reading in all public or private schools, colleges and universities. The Board of National Education shall determine the adequacy of the number of books, depending upon the enrollment of the school, college or university. SECTION 3. The Board of National Education shall cause the translation of the Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, as well as other writings of Jose Rizal into English, Tagalog and the principal Philippine dialects; cause them to be printed in cheap, popular editions; and cause them to be distributed, free of charge, to persons desiring to read them, through the Purok organizations and Barrio Councils throughout the country. SECTION 4. Nothing in this Act shall be construed as amendment or repealing section nine hundred twenty-seven of the Administrative Code, prohibiting the discussion of religious doctrines by public school teachers and other person engaged in any public school. SECTION 5. The sum of three hundred thousand pesos is hereby authorized to be appropriated out of any fund not otherwise appropriated in the National Treasury to carry out the purposes of this Act. SECTION 6. This Act shall take effect upon its approval. Approved: June 12, 1956 Senate Bill No. 438 House Bill No. 5561 Archbishop of Manila - bishop Rufino Santos Mayor of Manila – Arsenio Lacson What is the RA 1425 or the Rizal Law? RA 1425, also commonly known as Rizal Law, was a law signed by President Ramon Magsaysay on June 12, 1956 that requires all schools in the country include Rizal’s life, works and writings in the curriculum. The rationale behind the law was that there is a need of rekindle and deepen the sense of nationalism and freedom of the people, especially of the youth. The law sought to cultivate character, discipline, and conscience and to teach the obligations of citizenship. Libraries are required to keep sufficient copies of Rizal’s writings, especially Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo. Language barrier and poverty-related restrictions were taken out of the equation with provisions such as translation of Rizal’s writings into English, Filipino and other major Philippine Languages and the free charge distribution through Purok Organizations and Barrio Councils. The main proponent of the law was Senator Claro M. Recto who was met by protestants from the Catholic Church. Senator Jose P. Laurel Sr., then Chairman of the Committee on Education sponsored the bill in the senate. REPUBLIC ACT NO. 229 AN ACT TO PROHIBIT COCKFIGHTING, HORSE RACING AND JAIALAI ON THE THIRTIETH DAY OF DECEMBER OF EACH YEAR AND TO CREATE A COMMITTEE TO TAKE CHARGE OF THE PROPER CELEBRATION OF RIZAL DAY IN EVERY MUNICIPALITY AND CHARTERED CITY, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES SECTION 1. The existing laws and regulations to the contrary notwithstanding, cockfighting, horse racing and jai-alai are hereby prohibited on the thirtieth day of December of each year, the date of the martyrdom of our great hero, Jose Rizal. SECTION 2. It shall be the official duty of the mayor of each municipality and chartered city to create a committee to take charge of the proper observance of Rizal Day Celebration of each year, in which he shall be the chairman, which shall be empowered to seek the assistance and cooperation of any department, bureau, office, agency or instrumentality of the Government, and the local civic and educational institutions. Among the ceremonies on Rizal Day shall be the raising of the Philippine flag at half mast in all vessels and public buildings. SECTION 3. Any person who shall violate the provisions of this Act or permit or allow the violation thereof, shall be punished by a fine of not exceeding two hundred pesos or by imprisonment not exceeding six months, or both, at the discretion of the court. In case he is the mayor of a municipality or a chartered city he shall suffer an additional punishment of suspension from his office for a period of one month. In case of partnerships, corporations or associations, the criminal liability shall devolve upon the president, director, or any other official responsible for the violation thereof. SECTION 4. This Act shall take effect upon its approval. Approved: June 9, 1948 Explanation: Rizal Day Mangubat gave three reasons explaining why Rizal's death served as a turning point to the nationalistic hopes of the countrymen: First is that it served as a signal to the Katipunan to raise up arms against the Spaniards and begin the revolution. It is important to note that it was not formed after the death of Rizal, rather, the event at Bagumbayan on December 30 crystallized the motives of the organization. Second, his execution also served as a realization to the elite that they weren't an exemption to the despotism of the Spanish rule. Many other sectors joined in the Katipunan as the revolutionary and nationalistic mind began to settle on them. Lastly, because the event happened at the turn of the century, it was also significantly considered as a "New Beginning" for the country. Emilio Aguinaldo gave the first decree to declare December 30 as "national day of mourning" and as anniversary of Jose Rizal's death. To observe this, he ordered that all flags must be hoisted at halfmast on December 29 and on the following day, there would be no government offices. The first ever monument of Rizal erected was on Daet, Camarines Norte and its unveiling is simultaneous to the first observance of Rizal Day on December 30, 1898 by the Club Filipino. February 1, 1902, the Philippine Commission ordained Act no. 345 which issues December 30 as Rizal Day and as national holiday observed each year. According to Ambeth Ocampo, oftentimes, heroes are remembered more on their deaths than their births. However, Mangubat mentions that the death of Rizal would not have that been more meaningful were it not for birth and life spent for the betterment of our country. There are many moves that wish to change the date of Rizal Day to June 19 because it has a more positive sense and that it is close to June 12 and May 28 which are the Philippine Independence Day and the National Flag Day, respectively. On the other hand, December 30 is nearer to the much more celebrated holidays of Christmas and New Year which often overshadow the hero's celebration. For me personally, although his birth date is a much more joyous celebration, his death can be a better perspective to look at the entirety of Rizal's life and why he was willing to die for the sake of his love for the country. MEMORANDUM ORDER No. 247 DIRECTING THE SECRETARY OF EDUCATION, CULTURE AND SPORTS AND THE CHAIRMAN OF THE COMMISSION ON HIGHER EDUCATION TO FULLY IMPLEMENT REPUBLIC ACT NO. 1425 ENTITLED "AN ACT TO INCLUDE IN THE CURRICULA OF ALL PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SCHOOLS, COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES, COURSES ON THE LIFE, WORKS AND WRITINGS OF JOSE RIZAL, PARTICULARLY HIS NOVELS, NOLI ME TANGERE AND EL FILIBUSTERISMO, AUTHORIZING THE PRINTING AND DISTRIBUTION THEREOF AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES" WHEREAS, Republic Act No. 1425 approved on June 12, 1956, directs all schools, colleges and universities, public and private, to include in their curricula, courses on the life, works and writings of Jose Rizal, particularly his novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo which "are a constant and inspiring source of patriotism with which the minds of the youth, especially during their formative and decisive years in school should be suffused;" WHEREAS, according to Dr. Rizal, "the school is the book in which is written the future of the nation;" WHEREAS, in 1996, the Filipino people will commemorate the centennial of Rizal’s martyrdom and, two years thereafter, the centennial of the Declaration of Philippine Independence; and WHEREAS, as we prepare to celebrate these watershed events in our history, it is necessary to rekindle in the heart of every Filipino, especially the youth, the same patriotic fervor that once galvanized our forebears to outstanding achievements so we can move forward together toward a greater destiny as we enter the 21st century. NOW, THEREFORE, I FIDEL V. RAMOS, President of the Republic of the Philippines, by virtue of the powers vested in me by law, hereby direct the Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports and the Chairman of the Commission on Higher Education to take steps to immediately and fully implement the letter, intent and spirit of Republic Act No. 1425 and to impose, should it be necessary, appropriate disciplinary action against the governing body and/or head of any public or private school, college or university found not complying with said law and the rules, regulations, orders and instructions issued pursuant thereto. Within thirty (30) days from issuance hereof, the Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports and the Chairman of the Commission on Higher Education are hereby directed to jointly submit to the President of the Philippines a report on the steps they have taken to implement this Memorandum Order, and one (1) year thereafter, another report on the extent of compliance by both public and private schools in all levels with the provisions of R.A. No. 1425. This Memorandum Order takes effect immediately after its issuance. DONE in the City of Manila, this 26th day of December in the year of Our Lord, Nineteen Hundred and Ninety-Four. Former President Fidel V. Ramos in 1994 through Memorandum Order no.247, directed the Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports and the Chairman of the Commission on the Higher Education to fully implement the RA 1425. In the year 1995, CHED Memorandum Order No. 3 was issued enforcing strict compliance to Memorandum Order no. 247 Republic Act No. 229 is an act prohibiting cockfighting horse. The said Memorandum Order issued by the CHED Commissioner Mona Valisno enforcing strict compliance to Memorandum Order No. 247 CHED MEMORANDUM NO. 3,s. 1995 Commission on Higher Education Office of the President of the Philippines January 13, 1995 CHED Memorandum No.3,s. 1995 To: Head of State Colleges and Universities Head of Private Schools, Colleges and Universities Office of the President Memorandum Order No. 247 Re: Implementation of Republic Act No. 1425 Enclosed is a copy of Memorandum Order No. 247 dated December 26, from the Office of the President of the Philippines entitled, "Directing Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports and the CHAIRMAN OF COMMISSION ON HIGHER EDUCATION to fully implement the Republic Act No. 1425 entitled "An Act to include in the curricula of all public and private schools, colleges and universities, courses on the Life, Works and Writings of Jose Rizal, particularly his novels, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, authorizing the printing and distribution thereof and for other purposes" for guidance of all concerned. Strict compliance therewith is requested. (sgd) MONA D. VALISNO Commissioner Officer-in-Charge WHY STUDY RIZAL? Aside from those mentioned above, there are other reasons for teaching the Rizal course in Philippine schools: To recognize the importance of Rizal’s ideals and teachings in relation to present conditions and situations in the society. To encourage the application of such ideals in current social and personal problems and issues. To develop an appreciation and deeper understanding of all that Rizal fought and died for. To foster the development of the Filipino youth in all aspects of citizenship. Take note, Rizal’s legacy is very important in changing the condition of our present society. His teachings challenge us all Filipinos to make a difference for the future of our country by living the teachings of Rizal. Likewise, it teaches us to be more responsible and braver enough to face the challenges in our present society by acting on the principles that Rizal had strongly spoken and lived. A Panoramic Survey (the Philippines in the 19th century) The essence of the life of Rizal is marked by the conditions that existed during his lifetime in the Philippines and around the world particularly in Europe. Rizal is the product of his era and his message sets forth as human declaration that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. The 19th century stands out as an extremely dynamic and creative age especially in Europe and the United States. During this period such concepts as industrialism, democracy, and nationalism gained ascendancy and triggered revolutionary changes in science, technology, economics, and politics. These changes enabled man to achieve the heights of prosperity and dignity. However, 19th century Philippines was largely medieval, although signs of progress or change were noted in certain sectors. Its social and economic structure was based on the old feudalistic patterns of abuse and exploitation of the indio. Earlier, clamor for reforms had mentioned unheeded; social and discontent caused confusion among the people. THE PHILIPPINES IN THE 19th CENTURY SOCIAL STRUCTURE: The Philippine society was predominantly feudalistic- the result of the Spanish land holding system imposed upon the country with the arrival of the conquistadores. An elite class exploited the masses, fostered by the “massive slave” relationship between the Spaniards and the Filipinos. The Spaniards exacted all forms of taxes and tributes, and drafted the natives for manual labor. Consequently, the poor became poorer and the rich wealthier. The Pyramidal structure: APEX (TOP) - peninsolares – spanish-born took the highest position in the society and (b) friars MIDDLE CLASS – favored rich natives, mestizos (half breed), criollos (Philippine-born Spaniards) BASE – indios were looked down upon Racial discrimination was prevalent as the Spanish born peninsulares were given the highest offices and positions in society. While the criollos, the Philippine-born Spaniards, the half breed or mestizos, enjoyed second priority and the native or indios were look down upon. This shows the structure of the Philippine government and its function. Unluckily, there were abuses of the officials in their power to hold public office. So, below are the specified sources of abuses and sometimes corruption by the officials in the administrative system. The main cause of the administrative system was the appointment of officials with inferior qualifications, and without dedication to duty, and moral strength to resist corruption for material advancement. These officials were given duties and powers and privileges. Another is the Union of the Church and the State. The principal officials of the Administrative system obtained their position by royal appointment, while the rest of the position were either filled by the governor general himself or were sold to the highest bidder. POLITICAL SYSTEM: Spain governed the Philippines through the Ministro de Ultramar (Ministry of the Colonies) established in Madrid in 1863. This body helped the Spanish monarch manage the affairs of the colonies and govern the Philippines through a centralized machinery exercising: Executive Legislative Judicial and Religious powers The Governor General appointed by the Spanish monarch headed the central administration in Manila, He was the king’s representative in all state and religious matters and as such he exercised extensive powers. He issued executive orders and proclamation and he had supervision and disciplinary powers over all government officials. He was the commander in chief of the armed forces of the Philippines. He had supreme authority in financial matters until 1784. He also exercised legislative powers with his cumplase. CUMPLASE is the power of the Governor-General to disregard or suspend a Royal decree if the condition in the colony does not warrant it.By which he could disregard or suspend any law or royal decree from Spain. An ex-officio president of the Royal Audiencia until 1861. He enjoyed religious duty gave him the prerogative to nominate priest to ecclesiastical positions and control the finances of the missions. In terms of its Political Structure, Spain governed the Philippines through the Ministro de Ultramar Ministry of the Colonies established in 1863 It helped the Spanish monarchs manage the affairs of the colonies Governed the Philippines through a centralized machinery Exercising executive, legislative, judicial and religious powers The Governor General Appointed by the King of Spain, headed the central administration in Manila. He served as the King’s representative. He issued executive and administrative orders over all government officials Responsible for all government and religious activities He was assisted by Lieutenant General (general segundo cabo) Alcaldes Mayores Civil Governors Led the provincial government (alcaldias) Alcaldes en ordinario City mayor and vice mayor Ruled the city government (ayuntamiento) Gobernadorcillo Town mayor Ruled the town government (principalia) Cabeza de Barangay Barangay captain Ruled the barrio The Guardia Civil Headed by alferez (Second lieutenant) Performed police duties Helped in the maintenance of peace and order The system of courts was a centralized system It was a pyramidical organization Headed by the Royal Audiencia Served as highest court for civil and criminal cases Together with the Governor General, they made laws for the country called autos acordados SOURCES OF ABUSES IN THE ADMINISTRATIVE SYSTEM The main cause of weakness of the administrative system was the appointment of officials with inferior qualifications -without dedication to duty, no moral strength to resist corruption. The kind of officials sent in the Philippines were corrupt, abusive and unqualified officers. They were not equipped to any public office. This was the reason why instead of focusing on their role as public officers to form a good and well nation, they focused on getting wealth through corruption. The worse thing was that, they became brutal and abusive to native Filipinos to the extent that they executed most of our fellow native Filipinos who fought and resisted against them. There was also complication in the situation between the union of the church and state. The priest or what we call the “Friars” also became powerful, cruel and corrupt. FRIARS. The missionaries or the friars as they were known, played a major role not only in propagating the Christian faith but also in the political, social, economic and cultural aspects of the Filipinos. Aside from spreading the word of God, they helped in pacifying the country.The checks adopted by Spain to minimize abuses either proved ineffective or discouraged the officials appointed by the King of Spain were ignorant of Philippine needs. This was the reason behind their bad motives to our Philippine nation. The most corrupt branch of government was the alcaldias. Dishonest and corrupt officials often exacted more tributes than required by law and pocketed the excess collections. They also monopolized provincial trade and controlled prices and business practices. The parish priests could check this anomaly but in many cases they encouraged the abuses in exchange for favors. Participation in the government of the natives was confined to the lowest offices. They participate only as gobernadorcillo of a town and cabeza de barangay of a barrio. The position of gobernadorcillo was honorary entitled to two pesos/month. The natural and constitutional rights and liberties of the indios were curtailed. Homes were searched without warrants. People were convicted and exiled for being filibusteros Books, magazines and other written materials could not be published without the approval of the Board of Censors THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM There was no systematic government supervision of schools. The teaching methods was obsolete. There was a limited curriculum and poor classroom facilities and there was an absence of teaching materials. The friars inevitably occupied a dominant position in the Philippine educational system. Religion was the main subject in the schools. Fear of God was emphasized and obedience to the friars was instilled. Indios were constantly reminded that they had inferior intelligence and were fit only for manual labor. These practices resulted in a lack of personal confidence and a development of inferiority complex. Students memorized and repeated the contents of books which they did not understand. Teacher discrimination against Filipinos was present. The friars were against the teaching of Spanish in the Philippines. They believed that the knowledge of the Spanish language would encourage the people to oppose Spanish rule. Indios might be inspired by the new ideas of freedom and independence, so they isolate Filipinos in the light of intellectual attainment. Since racial discrimination is rampant Indios were not allowed to study and they are only good for manual labor and students/pupils before were only to memorize and repeated the contents of books, religion also was the main subject in the schools in order for them to inculcate in their mind the Fear of God. As seen above the educational system Filipinos were left behind because of discrimination, after sometime the Filipinos allowed to study in the Philippines and in abroad. Ateneo de Manila / Escuela Pia and College of San Juan de Latran Only school offering secondary education in the Philippines At the end of the Spanish period, the College of San Juan de Letran was the only official secondary school in the Philippines although secondary education was offered at the Ateneo de Manila. Seven provinces had private colleges and Latin schools for general studies, and Secondary Education for girls was furnished by five colleges in Manila. These are: Santa Isabel La Concordia Santa Rosa Looban Santa Catalina Up the end of the Spanish regime, the University of Santo Tomas was the only institution in the University level of Manila. Initially established solely for Spaniards and mestizos, it opened its doors to Filipino students for decades before the end of the Spanish rule. Felipe Buencamino In 1820, he led the petition criticizing the Dominican methods of instruction in UST, clamored for better professors and demanded government control their University thru anonymous letters. One cannot fully understand Rizal’s thought without understanding the social and political context of the 19th century. Social scientists marked the 19th century as the birth of modern life as well as the birth of many nation-states around the world. The birth of modernity was precipitated by three great revolutions around the world: the Industrial revolution in England, the French Revolution in France and the American Revolution. This will be discussed in module 3. PENINSULARES- Considered as the highest position in the pyramidal structure of the Philippine society Problems of the educational system in 19th century CHRISTIANITY- Weapon for facilitating the political and economic subjugation of the native during the 19th century in the Philippine society. POOR BECAME POORER AND THE RICH WEALTHIER- result of the Spaniards giving taxes and tributes to the natives. DIVIDE AND CONQUER- Approach of the Spaniards to the colonization. MINISTRO DE ULTRAMAR – Governed the Philippines ( Political System) SOCIO-CULTURAL ASPECT- not managed by the Spanish Monarch GOVERNOR GENERAL- The representative of king of Spain and responsible for all government and religious activities GOVERNOR CRESPO – Who organized the commission, study and recommend remedial measures to improve elementary education in the Philippines. ALCALDIAS- most corrupt brach of the government GOVERNOR GENERAL- He issued executive and administrative orders over all government officials GOBERNADORCILLO- Town Mayor CABEZA DE BARAANGAY- Barangay captain Guardia Civil- headed by alvarez Gobernadorcillo-ruled the principalia Rizal and Theory of Nationalism INTRODUCTION: Today we will discuss about the Birth of National Consciousness and Filipino Nationalism, the reasons why Rizal was considered a National Hero and the service given and sacrificed by him for the sake of our Country. We will also discuss the reasons why our nation is considered as an imagined community. Rizal and the Theory of Nationalism José Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines, is not only admired for possessing intellectual brilliance but also for taking a stand and resisting the Spanish colonial government. While his death sparked a revolution to overthrow the tyranny, Rizal will always be remembered for his compassion towards the Filipino people and the country. José Protasio Rizal Mercado Y Alonso Realonda was born on June 19, 1861 to Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonzo in the town of Calamba in the province of Laguna. He had nine sisters and one brother. At the early age of three, the future political leader had already learned the English alphabet. And, by the age of five, José could already read and write. When he enrolled in the Ateneo Municipal de Manila (now referred to as Ateneo De Manila University), he dropped the last three names from his full name, after his brother’s advice – hence, his more popular name José Protasio Rizal. His performance in school was outstanding – winning various poetry contests, impressing his professors with his familiarity of Castilian and other foreign languages, and crafting literary essays that were critical of the Spanish historical accounts of pre-colonial Philippine societies. A man with multiple professions. While he originally obtained a land surveyor and assessor’s degree in Ateneo, Rizal also took up a preparatory course on law at the University of Santo Tomas (UST). But when he learned that his mother was going blind, he decided to switch to medicine school in UST and later on specialized in ophthalmology. In May 1882, he decided to travel to Madrid in Spain, and earned his Licentiate in Medicine at the Universidad Central de Madrid. Apart from being known as an expert in the field of medicine, a poet, and an essayist, Rizal exhibited other amazing talents. He knew how to paint, sketch, and make sculptures. Because he lived in Europe for about 10 years, he also became a polyglot – conversant in 22 languages. Aside from poetry and creative writing, Rizal had varying degrees of expertise in architecture, sociology, anthropology, fencing, martial arts, and economics to name a few. Apart from being known as an expert in the field of medicine, a poet, and an essayist, Rizal exhibited other amazing talents. He knew how to paint, sketch, and make sculptures. Because he lived in Europe for about 10 years, he also became a polyglot – conversant in 22 languages. Aside from poetry and creative writing, Rizal had varying degrees of expertise in architecture, sociology, anthropology, fencing, martial arts, and economics to name a few. His novels awakened Philippine nationalism Rizal had been very vocal against the Spanish government, but in a peaceful and progressive manner. For him, “the pen was mightier than the sword.” And through his writings, he exposed the corruption and wrongdoings of government officials as well as the Spanish friars. While in Barcelona, Rizal contributed essays, poems, allegories, and editorials to the Spanish newspaper, La Solidaridad. Most of his writings, both in his essays and editorials, centered on individual rights and freedom, specifically for the Filipino people. As part of his reforms, he even called for the inclusion of the Philippines to become a province of Spain. But, among his best works, two novels stood out from the rest – Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not) and El Filibusterismo (The Reign of the Greed). In both novels, Rizal harshly criticized the Spanish colonial rule in the country and exposed the ills of Philippine society at the time. And because he wrote about the injustices and brutalities of the Spaniards in the country, the authorities banned Filipinos from reading the controversial books. Yet they were not able to ban it completely. As more Filipinos read the books, their eyes opened to the truth that they were suffering unspeakable abuses at the hands of the friars. These two novels by Rizal, now considered his literary masterpieces, are said to have indirectly sparked the Philippine Revolution. Upon his return to the Philippines, Rizal formed a progressive organization called the La Liga Filipina. This civic movement advocated social reforms through legal means. Now Rizal was considered even more of a threat by the Spanish authorities (alongside his novels and essays), which ultimately led to his exile in Dapitan in Northern Mindanao. This however did not stop him from continuing his plans for reform. While in Dapitan, Rizal built a school, hospital, and water system. He also taught farming and worked on agricultural projects such as using abaca to make ropes. Rizal was granted leave by then Governor-General Blanco, after volunteering to travel to Cuba to serve as doctor to yellow fever victims. But at that time, the Katipunan had a full-blown revolution and Rizal was accused of being associated with the secret militant society. On his way to Cuba, he was arrested in Barcelona and sent back to Manila to stand for trial before the court martial. Rizal was charged with sedition, conspiracy, and rebellion – and therefore, sentenced to death by firing squad. Days before his execution, Rizal bid farewell to his motherland and countrymen through one of his final letters, entitled Mi último adiós or My Last Farewell. Dr. José Rizal was executed on the morning of December 30, 1896, in what was then called Bagumbayan (now referred to as Luneta). Upon hearing the command to shoot him, he faced the squad and uttered in his final breath: “Consummatumest” (It is finished). According to historical accounts, only one bullet ended the life of the Filipino martyr and hero. His legacy lives on after his death, the Philippine Revolution continued until 1898. And with the assistance of the United States, the Philippines declared its independence from Spain on June 12, 1898. This was the time that the Philippine flag was waved at General Emilio Aguinaldo’s residence in Kawit, Cavite. Some Literary Pieces of Dr. Jose Rizal To the Filipino Youth Rizal wrote this literary poem when he was still studying at the University of Sto. Tomas (UST). Originally written in Spanish (A la juventud filipina), Rizal submitted this piece for a poem contest organized for Filipinos by the Manila Lyceum of Art and Literature. At the age of 18, this work is beaming with strong messages to convince readers, the youth in particular, that they are the hope of the nation. He also stresses the importance of education to one’s future. Rizal won the first prize and was rewarded with a feathershaped silver pen and a diploma. To the Young Women of Malolos Addressed to the Filipino women, Rizal’s letter entitled To The Young Women of Malolos reflects his inheritance and issues reminders to Filipino women. In his letter, he addresses all kinds of Filipino women – mothers, wives, and even the single women. Throughout this literary piece, he highlights the qualities that Filipino mothers should possess, the duties of wives to their husbands and children, and a counsel on how young women should choose their lifetime partners. The idea behind this letter sparked after he was impressed by the women of Malolos who won the battle they fought. Rizal advises women to educate themselves, protect their dignity and honor, and live with good manners – setting up as a role model. Hymn to labor Jose Rizal’s patriotism is shown in this poem where he urges his fellowmen to strive and work for their country whether in war or in peace. This poem was originally written in Tagalog as Imno sa Paggawa. Noli Me Tángere One of the most sought-after books in Philippine literature until today, is Rizal’s famous novel titled Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not). Driven by his undying love for his country, Rizal wrote the novel to expose the ills of Philippine society during the Spanish colonial era. At the time, the Spaniards prohibited the Filipinos from reading the controversial book because of the unlawful acts depicted in the novel. Yet they were not able to ban it completely and as more Filipinos read the book, it opened their eyes to the truth that they were being manhandled by the friars. In this revolutionary book, you’ll learn the story of Crisostomo Ibarra, how he dealt with Spanish authorities, and how he prepared for his revenge, as told in Rizal’s second book, El Filibusterismo. El Filibusterismo This is Rizal’s sequel to his first book, Noli Me Tángere. In El Filibusterismo (The Reign of the Greed), the novel exhibits a dark theme (as opposed to the hopeful atmosphere in the first novel) in which it depicts the country’s issues and how the protagonist attempts a reform. The story takes place 13 years after Noli Me Tángere, where revolutionary protagonist Crisostomo Ibarra is now under the guise of Simoun – a wealthy jewelry tycoon. Because the novel also portrays the abuse, corruption, and discrimination of the Spaniards towards Filipinos, it was also banned in the country at the time. Rizal dedicated his second novel to the GOMBURZA – the Filipino priests named Mariano Gomez, Jose Apolonio Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora who were executed on charges of subversion. The two novels of Rizal, now considered as his literary masterpieces, both indirectly sparked the Philippine Revolution. The Birth of National Consciousness Filipino Nationalism Filipino Nationalism is an upsurge of patriotic sentiments and nationalistic ideals in the Philippines of the 19th century that came consequently as a result of more than two centuries of Spanish rule and as an immediate outcome of the Filipino Propaganda Movement (mostly in Europe) from 1872 to 1892. It served as the backbone of the first nationalist revolution in Asia, the Philippine Revolution of 1896. The Creole Age (1780s- 1872) The term 'Filipino' in its earliest sense referred to Spaniards born in the Philippines or Insulares (Creoles) and from which Filipino Nationalism began. Traditionally, the Creoles had enjoyed various government and church positions—composing mainly the majority of the government bureaucracy itself. The decline of Galleon Trade between Manila and Acapulco and the growing sense of economic insecurity in the later years of the 18th century led the creole to turn their attention to agricultural production. Characterized mostly in Philippine history as corrupt bureaucrats, the Creole gradually changed from a very government-dependent class into capitaldriven entrepreneurs. Their turning of attention towards gild soil caused the rise of the large private haciendas. The earliest signs of Filipino Nationalism could be seen in the writings of Luis Rodriquez Varela, a Creole educated in liberal France and highly exposed to the romanticism of the age. Knighted under the Order of Carlos III, Varela was perhaps the only Philippine Creole who was actually part of European nobility. The court gazzette in Madrid announce that he was to become a Conde and from that point on proudly called himself 'Conde Filipino'. He championed the rights of Filipinos in the islands and slowly made the term applicable to anyone born in the Philippines. However, by 1823 he was deported together with other creoles (allegedly kn own as HijosdelPais), after being associated with a Creole revolt in Manila led by the Mexican Creole Andres Novales. Varela would then retire from politics but his nationalism was carried on by another Creole Padre Pelaez, who campaigned for the rights of Filipino priests and pressed for secularization of Philippine parishes. The Latin American revolutions and decline of friar influence in Spain resulted in the increase of the regular clergy (friars) in the Philippines. Filipino priests were being replaced by Spanish friars and Pelaez demanded explanation as to the legality of replacing a secular with regulars—which is in contradiction to the Exponinobis. Pelaez brought the case to the Vatican almost succeeded if not for an earthquake that cut his career short and the ideology would be carried by his more militant disciple, Jose Burgos. Burgos in turn died after the infamous Cavite Mutiny, which was pinned on Burgos as his attempt to start a Creole Revolution and make himself president or 'reyindio'. The death of Jose Burgos, and the other alleged conspirators Mariano Gomez and Jacinto Zamora, seemingly ended the entire creole movement in 1872. GovernorGeneral Rafael de Izquierdo unleashed his reign of terror in order to prevent the spread of the creole ideology—Filipino nationalism. But the creole affair was seen by the other natives as a simple family affair—Spaniards born in Spain against Spaniards born the Philippines. The events of 1872 however invited the other colored section of the Ilustrado (intellectually enlightened class) to at least do something to preserve the creole ideals. Seeing the impossibility of a revolution against Izquierdo and the Governor-General’s brutal reign convinced the ilustrado to get out of the Philippines and continue propaganda in Europe. This massive propaganda upheaval from 1872 to 1892 is now known as the Propaganda Movement. Through their writings and orations, Marcelo H. delPilar, Graciano Lopez Jaena and Jose Rizal sounded the trumpets of Filipino nationalism and brought it to the level of the masses. Rizal’s Noli me tangere and El filibusterismo rode the increasing anti-Spanish sentiments in the islands and was pushing the people towards revolution. By July 1892, an ilustrado mass man in the name of Andres Bonifacio established a revolutionary party based on the Filipino nationalism that started with ' los hijos del pais'—Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan. Ideology turned into revolution and gave Asia its first anti-imperialist/nationalist revolution by the last week of August 1896. Causes of the Awakening of the Filipinos’ National Consciousness The opening of Manila (1834) and other parts of the Philippine to foreign trade brought not only economic prosperity to the country but also a remarkable transformation in the life of the Filipinos. As the people prospered, their standard of living improved. They came into contact with foreign ideas and with travelers from foreign lands. They read periodicals and books, including those brought in from abroad. As a result, their mental horizons were broadened. They became discontented with the old order of things and wanted social and political changes that were in harmony with the freer spirit of the times. Economic prosperity produced a new class of Filipinos–the intelligentsia–educated, widely read, and enlightened individuals. Many Filipinos had learned Spanish, and some knew other Western languages such as French, English, and German. Boldly patriotic, they discussed social and economic problems and advocated reforms to remedy the evils of colonialism. Many of them sent their children to colleges and universities not only in Manila but in Europe too. From the intelligentsia came patriotic leaders who sowed the seeds of Filipino nationalism. Among these were Father Pedro Pelaez, Father Jose Burgos, Dr. Jose Rizal, Marcelo H. delPilar, the Luna Brothers (Juan and Antonio), Jose ma. Panganiban, Mariano Ponce, Graciano Lopez Jaena and Pedro A. Paterno. Through the newly opened ports of the Philippines streamed liberal and modern idea. These ideas were contained in books and periodicals brought in by ships form Europe. These included ideas of freedom of the American and French revolutions and enlightened thoughts of Montesquieu, Rousseau, Voltaire, Locke, Jefferson, and other philosophers of freedom. The Filipinos began to wonder at the deplorable situation in the Philippines. In their minds sprouted the aspirations for reforms, justice, and liberty. The opening of the Suez Canal which was built by Ferdinand de Lesseps to world shipping on November 17, 1869, linked the Philippines closer to Europe. It promoted the flow of ideas of freedom into the Philippines. Opening of the Philippines to world trade from 1834 to 1873 This stimulated the economic activities in the country which brought prosperity to some of the Filipinos but most of all to the Chinese and the Spaniards. It resulted to the rise of a new social class referred to as “Middle Class” or the “Illustrados”. Acquired material wealth Improved their social stature and influence Clamored for social and political equality with the colonial masters Influx of Liberal Ideas With the opening of the Philippines to world trade, European ideas freely penetrated the country in form of printed books, newspapers, and treatises made available to the natives as they participated in the process of exchange of goods and products. The new knowledge and current events they learned and acquired outside affected their ways of living and the manner of their thinking. The Rise of the Middle Class The middle class or the Illustrado their family particularly male children students would be exposed to European lead in call for reforms Filipino patriots came from this class. family sent members of to study abroad. These thoughts and would later and propagandist mostly Opening of Suez Canal The Suez Canal was created by a French engineer named Ferdinand de Lesseps This man-made canal made transportation easier, making the transfer of goods and ideas better and faster. With the opening of this canal, the distance of travel between Europe and the Philippines was significantly shortened and brought the country closer to Spain. With this canal, the trip was reduced to only 32 days. The opening of the Suez Canal facilitated the importation of books, magazines and newspapers with liberal ideas from Europe and America which eventually influenced the minds of Jose Rizal and other Filipino reformists. Political thoughts of liberal thinkers like Jean Jacques Rousseau (Social Contract), John Locke (/two Treatises of Government), Thomas Paine (Common Sense) and others entered the country (Maguigad & Muhi 2001; 62). The opening of this canal in 1869 further stimulated the local economy which give rise—as already mentioned above--to the creation of the middle class of mestizos and illustrados in the 19th century. The shortened route has also encouraged the ilustrados led by Rizal to pursue higher studies abroad and learn liberal and scientific ideas in the universities of Europe. Their social interaction with liberals in foreign lands has influenced their thinking on politics and nationhood. Liberal Regime of Carlos Ma. Dela Torre The first-hand experience of what it is to be liberal came from the role modeling of the first liberal governor general in the Philippines—Governor General Carlos Ma. Dela Torre. Why Govenor Dela Torre was able to rule in the Philippines has a long story. The political instability in Spain had caused frequent changes of Spanish officials in the Philippines which caused further confusion and increased social as well as political discontent in the country. But when the liberals deposed Queen Isabela II in 1868 mutiny, a provisional government was set up and the new government extended to the colonie the reforms they adopted in Spain. These reforms include the grant of universal suffrage and recognition of freedom and conscience, the press, association and public assembly. General Carlos Ma. De la Torre was appointed by the provisional government in Spain as Governor General of the Philippines (Romero et al 1978: 21). The rule of the first liberal governor general in the person of General de la Torre became significant in the birth of national consciousness in the 19th century. De la Torre’s liberal and propeople governance had given Rizal and the Filipinos during this period a foretaste of a democratic rule and way of life. De la Torre put into practice his liberal and democratic ways by avoiding luxury and living a simple life. During his two-year term, Governor De la Torre had many significant achievements. He encouraged freedom and abolished censorship (Maguigad & Muhi 2001: 63). He recognized the freedom of speech and of the press, which were guaranteed by the Spanish Constitution. Because of his tolerant policy, Father Jose Burgos and other Filipino priests were encouraged to pursue their dream of replacing the friars with the Filipino clergy as parish priests in the country (Zaide 1999: 217). Governor De la Torre’s greatest achievement was the peaceful solution to the land problem in Cavite. This province has been the center of agrarian unrest in the country since the 18thcentury because the Filipino tenants who lost their land had been oppressed by Spanish landlords. Agrarian uprisings led by the local hero, Eduardo Camerino, erupted several times in Cavite. This agrarian problem was only solved without bloodshed when Governor De la Torre himself went to Cavite and had a conference with the rebel leader. He pardoned the latter and his followers, provided them with decent livelihood and appointed them as members of the police force with Camerino as captain. It was during his term as governor general that freedom of speech was allowed among the Filipinos De la Torre was a well-loved leader because he was concern with the needs of the natives He ordered the abolition of flogging as punishment for military disobedience He implemented the Educational Decree of 1863 and the Moret Law which delimit the secularization of educational institutions and allowed the government to take control among different schools and academic institutions. NATIONALISM According to Gellner, “nationalism” is not the awakening of nations to self- consciousness: it invents nations where they do not exist. The drawback to this formulation, however, is that Gellner is so anxious to show that nationalism masquerades under false pretences that he assimilates “inventions” to “fabrication” and falsity, rather than to “imagining” and creation. RIZAL AND NATIONALISM Acquiring a better understanding of Rizal’s life demands a deeper and more profound analysis of his life and writings. His firm beliefs were the results of what he had seen and experienced during his European days. Thus, to clear up vague thoughts about him requires a glimpse into his past. Rizal was one of the elites who demands changes in the Philippine government during the Spanish colonization. Together with his other ilustrado friends, Rizal voiced the inclusion of Filipinos as representatives in the Cortes. Filipinization in churches and equal rights were among the requests made by Rizal to the Spanish government. Rizal fought for equality with the Spaniards. Rizal and his fellow ilustrados wanted to acquire the same education and wealth as the Spanish students and families in the Philippines have. The unheard cries of the natives and the increasing fame of Rizal fueled revolts in the country. The natives organized groups and continued to engage in bloody battles to acquire reforms and democracy. Rizal’s writings made a huge impact on the minds of the native who wished to break free from the abuses of the Spaniards. When Rizal was imprisoned, numerous plans to break him out of jail were initiated by the revolting group but none of them prospered as Rizal preferred to engage in a bloodless battle for independence The dilemma that Rizal faced was depicted in his two famous novels, the Noli and El Fili In Noli Me Tangere, Rizal was represented by both Elias and Ibarra. In the chapter, “Voice of the Hunted,” Elias believed in the need for radical reforms in the armed forces, priesthood, and administrative justice system. While, Ibarra did not agree with the reforms Elias wanted and believed in the power of the authorities and the need for necessary evil. In the chapter, “Elias’ Story,” Elias saw the need for an armed struggle and resistance against the opposing forces while Ibarra disagreed and believed that education was the key to make the people liberated, so he encourages the building of schoolhouses to educate those who are worthy of it. In the chapter “Chase on the Lake,” Elias suddenly had a change of heart; he believed in reforms while Ibarra became a filibuster, initiating revolution. This change of heart in Ibarra was a product of hardships and the desire to attain personal vengeance This trend of vagueness continued in the novel El Fili, were Rizal was reflected in the characters of Simoun, Basilio, and Padre Florentino. In the conclusion of the El Fili, Rizal has implied his resolution when in the story, he killed Simoun, the promoter of revolution, and made Padre Florentino, an advocate of peace. In real life, Rizal reiterated his stand regarding this issue in his December 15 Manifesto when he declared that he was against the revolution, and he favored the reform programs, especially regarding education. In the process of making circumstances favorable for both, his appeal was for reforms and education. What would liberate the people was the massive movement of the natives united against the oppressors. When Rizal died, the natives were able to push through their freedom with their strong nationalism that had been heated up and strengthened by his artistic and realistic viewpoints in his writings. He had influenced numerous natives to fight for independence. The result of independence was very sweet for the Filipinos who fought and died for it, and it was a regret feel that Rizal was not able to see that the revolution that he did not favor was what liberated his people. Nationalism usually springs from the consciousness of a national identity of being one people. It is that all pervading spirit that binds together men of diverse castes and creeds, clans and colors, and unites them into one people, one family, one nation with common aspirations and ideals (Anderson, 1983) IMAGINED COMMUNITY An IMAGINED COMMUNITY is a concept developed by Benedict Anderson in his 1983 book Imagined Communities, to analyze nationalism. Anderson depicts a nation as a socially constructed community, imagined by the people who perceive themselves as part of that group. NATION NATION “An imagined political community- and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign”. (Benedict Anderson, Imagined Community) It is an anthropological spirit, then I propose the following definition of the Nation: it is an imagined community-and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign. “Imagined” means that we will never meet the majority of the community members. It is imagined because members cannot all know each other. The members of even the smallest nation will never know most their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them. Yet in the minds of their lives the image of their communion Nation as “limited” meaning that it co-exists with other nations on the same plane. Also, because of finite boundaries. “Sovereign” means that it is self-governing, not ruled by an outside power (as in imperialism) or by a higher power (as in older religious world news.) It is imagined as sovereign because the concept was born in an age in which enlightenment and Revolution were destroying the legitimacy of the divinely-ordained, hierarchical dynastic realm. It is imagined as sovereign because it is not religious or monarchic. Finally, it is imagined as a community because, regardless of the actual inequality and exploitation that may prevail in each nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship. National identity is a sense of a nation: as a cohesive whole as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language. Genealogy of Rizal and His Descendants Introduction Jose Rizal lived in the nineteenth century, a period in history when changes in public consciousness were already being felt and progressive ideas were being realized. Studying Rizal’s genealogy, therefore, will lead to a better understanding of how Rizal was shaped and influence by his family. As discussed in the previous modules, Rizal was born on June 19, 1861 in the town of Calamba, province of Laguna. Calamba, the town with around three to four thousand inhabitants, is located 54 kilometers south of Manila. It is found in a heart of a region known for its agricultural prosperity and is among the major producers of sugar and rice, with an abundant variety of tropical fruits. On the Southern part of the town lies the majestic Mount Makiling, and on the other side is the Lake called Laguna the Bay. The wonders of creation that surrounded Rizal made him love nature form an early age. His student memoirs show how his love of nature influenced his appreciation of the arts and sciences. Rizal’s father, Francisco Mercado, was a wealthy farmer who leased lands from the Dominican Friars. Francisco’s earliest ancestors were Siang-co and Zun-nio, who later gave birth to Lamco. Lam-co is said to have come from the district of Fujian in Southern China and migrated to the Philippines in the late 1600’s. In 1967, he was baptized in Binondo, adopting “Domingo” as his first name. He married Ines de la Rosa of a known entrepreneurial family in Binondo. Domingo and Ines later settled in the estate of San Isidro Labrador, owned by the Dominicans. In 1731, they had a son whom they named Francisco Mercado. The surname Mercado, which means “market,” was a common surname adopted by many Chinese merchants at that time (Reyno, 2012). Francisco Mercado became one of the richest in Biñan and owned the largest herd of carabaos. He was also active in local politics and was elected as capitan del pueblo in 1783. He had a son named Juan Mercado who was also elected as capitan del pueblo in 1808, 1813, and 1823. (Reyno, 2012). Juan Mercado married Cirila Alejandra, a native of Biñan. They had 13 children, including Francisco Engracio, the father of Jose Rizal. Following Governor Narcisco Claveria’s decree in 1849 which ordered the Filipinos to adopt Spanish surnames, Francisco Engracio added the surname “Rizal,” form the word “racial” meaning “green field”, as he later setlled in the town of Calamba as a framer growing sugar cane, rice, and indigo. Being in a privileged family, Francisco Engracio (1818-1898) had a good education that started in a Latin school in Biñan. Afterwards, he attended the College of San Jose in Manila. IN 1848, Francisco married Teodora Alonso (1826-1911) who belonged to the one of the wealthiest families in Manila. Teodora, whose father was a member of the Spanish Cortes, was educated at the College of Sta. Rosa. Rizal described her as a “woman of more than ordinary culture” and that she is “a mathematician and has read many books” (letter Blumentritt, November 8, 1888). Because of Francisco and Teodora’s industry and hard work, their family became prominent member of the principalia class in the town of Calamba. Their house was among the first concrete houses to be built in the town. Rafael Palma, one of the first biographers of Jose Rizal, described the family’s house: R i z a l “The house was high and even sumptuous, a solid and massive earthquake-proof structure with sliding shell windows. Thick walls of lime and stone bounded the first floor; the second floor was made entirely of wood except for the roof, which was of red tile, in the style of the buildings in MANILA AT THAT TIME. Francisco himself selected the hardest woods from the forest and had them sawed; it took him more than two years to construct the house. At the back there was an azotea and a white, deep cistern to hold rain water for home use.” and the Lessons His Mother Taught Him by Ma. Cielito G. Reyno published by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (2018) Of all the persons who had the greatest influence on Rizal’s development as a person was his mother Teodora Alonso. It was she who opened his eyes and heart to the world around him—with all its soul and poetry, as well as its bigotry and injustice. Throughout his brief life, Rizal proved to be his mother’s son, a chip off the old block, as he constantly strove to keep faith the lessons she taught him. His mother was his first teacher, and from her he learned to read, and consequently to value reading as a means for learning and spending one’s time meaningfully. It did not take long before he learnt to value time as life’s most precious gift, for she taught him never to waste a single second of it. Thus as a student in Spain he became the most assiduous of students, never missing a class despite his activities as Propaganda leader, or an examination, despite having to take it on an empty stomach. By his example, he inspired his compatriots – those who had sunk into a life of dissipation, wasting time and allowances on gambling and promiscuity- to return to their studies and deserve their parents’ sacrifices back home. From his mother he learnt the primacy of improving oneself- thus growing up he took pains to comprehend the logic of mathematics; to write poems; to draw, and sculpt; to paint. Sadly, for all these he earned not only glory but also the fear of myopic souls. By taking the lead in running the family’s businesses- farms, flour and sugar milling, tending a store, even making fruit preserves, aside from running a household, Teodora imbibed in him the value of working with one’s hands, of self-reliance and entrepreneurship. And by sharing with others she taught him generosity and helping to make the world a better place for those who had less in the material life. All these lessons he applied himself during his exile in Dapitan, as he improved its community by building a dam; encouraging the locals to grow fruit trees, establishing a school, even documenting the local flora and fauna. His mother also taught him to value hard-earned money and better yet, the importance of thrift and of denying oneself, and saving part of one’s earnings as insurance against the vagaries of life. Thus he learned to scrimp and save despite growing up in comfort and wealth. These would later prove very useful to him during his stay in Europe as he struggled with privation, considering the meager and often delayed allowance that his family sent him (by then his family was undergoing financial reverses due to land troubles). Whenever his precious allowance ran out, he went without lunch and supper, putting up a front before everyone by going out of his dormitory every day to give the impression that he took his meals outside. But, as he walked the streets of Berlin or Barcelona, his nostrils would be assailed by the delicious aroma of the dishes being cooked within buildings and houses, increasing his hunger pangs and his suffering all the more. Other times he saved up on rent by foregoing breakfast altogether, his breakfast consisting of biscuits and water for a month. Above all, it was from her he learned about obedience, through the story of the moth that got burned by the flame because he disobeyed his mother moth’s warning not to get too near the flame. But life as it often happens has poignant way of turning around, for it was obedience to the Catholic Church, as his mother taught him, which proved too hard to live by especially when he struggled with a crisis of faith in its teachings.Teodora took none too gently his defection from the Church, which she saw was an apostasy from faith itself. One of the turning points of his life, which had a profound influence on his becoming a political activist later on, was the unjust arrest of his mother on the charge of conspiring to poison a relative, despite the lack of evidence against her. But what made the arrest even worse was her humiliating treatment at the hands of authorities who made her walk all the way from Calamba to the provincial jail in Santa Cruz, which was 50 kilometers far. There she was imprisoned for two years before gaining her freedom. All these she took with calm and quiet dignity, which Rizal though only a child of eleven about to embark on secondary school in Manila would remember and replicate during his final moments just before a firing squad snuffed out his meaningful life on that fateful December morn in 1896. Rizal and His Siblings 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Saturnina Rizal (1850-1913)- Eldest child of the Rizal-Alonzo marriage. Married Manuel Timoteo Hidalgo of Tanauan, Batangas. Paciano Rizal (1851-1930)- Only brother of Jose Rizal and the second child. Studied at San Jose College in Manila; became a farmer and later a general of the Philippine Revolution. Narcisa Rizal (1852-1939) -The third child. married Antonio Lopez at Morong, Rizal; a teacher and musician. Olympia Rizal -(1855-1887) The fourth child. Married Silvestre Ubaldo; died in 1887 from childbirth. Lucia Rizal (1857-1919)- The fifth child. Married Matriano Herbosa. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Maria Rizal (1859-1945-) The sixth child. Married Daniel Faustino Cruz of Biñan, Laguna. Jose Rizal (1861-1896)- The second son and the seventh child. He was executed by the Spaniards on December 30,1896. Concepcion Rizal (1862-1865)- The eight child. Died at the age of three. Josefa Rizal (1865-1945) -The ninth child. An epileptic, died a spinster. Trinidad Rizal (1868-1951) -The tenth child. Died a spinster and the last of the family to die. Soledad Rizal (1870-1929)- The youngest child married Pantaleon Quintero. Rizal was affectionate to all his siblings. However, his relation to his only brother, Paciano, was more than that of an older brother. Paciano became Rizal’s second father. Rizal highly respected him and value all his advice. It was Paciano who accompanied Rizal when he went to school in Biñan. It was also him who convinced Rizal to persue his studies in Europe. Like Rizal, Paciano also had his college in Manila but later joined the Katipunan to fight for Independence. After the revolution, Paciano retired to his home in Los Baños and lived a quiet life until his death in 1930.