A fine balance: individualism, society and the prevention of mental illness in the United States

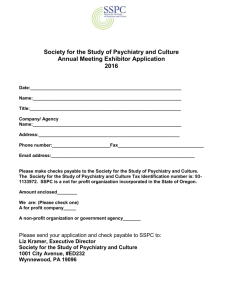

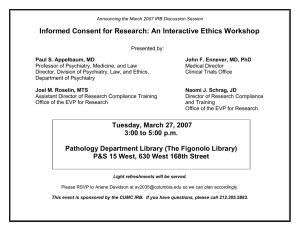

advertisement