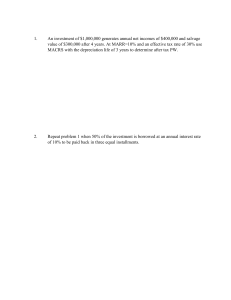

Capitalized Costs Title of Course and Depreciation Participant Manual 2017 Instructor Notes 2017 By Dr. Shelley Rhoades-Catanach, Ph.D., CPA A Customized Curriculum for Firms Copyright Copyright 2017 2017 By American Institute of Certified Accountants By Association of International Certified Public Professional Accountants Durham, North Carolina Durham, North Carolina All All Rights Rights Reserved Reserved Month 2017 Version Date: January 2017 The AICPA offers a free, daily, e-mailed newsletter covering the day’s top business and financial articles as well as video content, research and analysis concerning CPAs and those who work with the accounting profession. Visit the CPA Letter Daily news box on the www.aicpa.org home page to sign up. You can opt out at any time, and only the AICPA can use your e-mail address or personal information. Have a technical accounting or auditing question? So did 23,000 other professionals who contacted the AICPA's accounting and auditing Technical Hotline last year. The objectives of the hotline are to enhance members' knowledge and application of professional judgment by providing free, prompt, high-quality technical assistance by phone concerning issues related to: accounting principles and financial reporting; auditing, attestation, compilation and review standards. The team extends this technical assistance to representatives of governmental units. The hotline can be reached at 1-877-242-7212. CAPITALIZED COSTS AND DEPRECIATION BY DR. SHELLEY RHOADES-CATANACH, PH.D., CPA TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1........................................................................................................................... 1-1 Tax Basis of Property Acquisitions .................................................................................... 1-1 Cost Basis of Purchased Business Assets .................................................................................... 1-3 Initial Basis of Property Acquired in an Exchange Transaction .................................................. 1-24 Adjusted Tax Basis ................................................................................................................... 1-28 Chapter 2........................................................................................................................... 2-1 Materials, Supplies, Repairs, and Improvements............................................................... 2-1 Materials and Supplies ............................................................................................................... 2-2 Repairs Versus Improvements .................................................................................................... 2-9 Accounting Methods Changes ................................................................................................. 2-25 Chapter 3........................................................................................................................... 3-1 Depreciation ...................................................................................................................... 3-1 Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System ............................................................................. 3-3 Alternative Depreciation System .............................................................................................. 3-19 Section 179 Limited Expensing Election ................................................................................... 3-20 First-Year Bonus Depreciation .................................................................................................. 3-26 Limitations on Depreciation of Passenger Automobiles and Other Listed Property .................. 3-30 Depreciation of Property Acquired in a Like-Kind Exchange or Involuntary Conversion ........... 3-36 Chapter 4........................................................................................................................... 4-1 Intangible Assets and Amortization .................................................................................. 4-1 Intangibles Capitalization ........................................................................................................... 4-3 Copyright 2017 $,&3$8QDXWKRUL]HG&RS\LQJ3URKLELWHG Table of Contents 1 Amortization ............................................................................................................................ 4-12 Organizational and Start-Up Costs........................................................................................... 4-16 Other Intangibles Issues........................................................................................................... 4-19 Appendix A....................................................................................................................... A-1 Additional Examples t Chapters 2 and 3 .......................................................................... A-1 Glossary ................................................................................................................. Glossary 1 Solutions ............................................................................................................... Solutions 1 Chapter 1 ...................................................................................................................... Solutions 1 Chapter 2 ...................................................................................................................... Solutions 2 Chapter 3 ...................................................................................................................... Solutions 4 Chapter 4 ...................................................................................................................... Solutions 7 Recent Developments Users of this course material are encouraged to visit the AICPA website at www.aicpa.org/CPESupplements to access supplemental learning material reflecting recent developments that may be applicable to this course. The AICPA anticipates that supplemental materials will be made available on a quarterly basis. Also DYDLODEOH RQ WKLV VLWH DUH OLQNV WR WKH YDULRXV ³6WDQGDUGV 7UDFNHUV´ RQ WKH $,&3$¶V Financial Reporting Center which include recent standard-setting activity in the areas of accounting and financial reporting, audit and attest, and compilation, review and preparation. 2 Table of Contents Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Chapter 1 TAX BASIS OF PROPERTY ACQUISITIONS LEARNING OBJECTIVES After completing this chapter, you should be able to do the following: x x x Recall the initial tax basis and adjusted tax basis of business property. Identify purchase price in a lump-sum purchase of business assets. Identify the tax basis of self-constructed assets. INTRODUCTION This chapter discusses fundamental concepts related to the tax basis of assets used in business activities. Tax basis is an important measure of the taxpayer·s investment in business property. It controls the ability to deduct such investment, through allowable cost recovery deductions. Tax basis also affects the calculation of taxable gain or deductible loss on disposition of assets. Thus, the tax life cycle of business property depends on identification of tax basis. Final regulations issued in 2013 provide detailed guidance on the treatment of costs to acquire or produce tangible property. We will first consider the initial tax basis of property at the time of acquisition. Initial tax basis often depends on the manner in which the property was acquired. For example, property acquired in a taxable purchase transaction will have different basis issues than property acquired as part of a nontaxable exchange transaction. Special tax rules apply in determining the tax basis of self-constructed assets. Allocation rules must be considered when a group of assets is acquired as part of a lump sum purchase of a business. This chapter addresses basis issues for each of these situations. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-1 For property acquired in a taxable purchase, initial tax basis is often referred to as cost basis. This chapter details the elements of such costs. Which acquisition-related costs are included in initial tax basis? Which costs are not part of tax basis, and may produce immediate tax deductions? In particular, how are debt financing, acquisition expenses, and installation costs treated for tax purposes? When property is acquired as part of a nontaxable exchange, carryover or substituted basis rules typically apply. While this chapter does not address in detail all of the opportunities for and tax consequences of such transactions, it describes in general the critical elements affecting the calculation of carryover or substituted basis for property acquired in a nontaxable exchange. Finally, the chapter concludes by reviewing the calculation of adjusted tax basis of business property, taking into account initial basis, capitalized improvements, and allowable cost recovery deductions. 1-2 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Cost Basis of Purchased Business Assets IRC Section 1012 provides that the basis of property acquired through purchase is its cost. Cost equals cash payments for property plus the fair market value of non-cash property given in payment. In addition to such purchase price, costs directly related to the acquisition of property must also be included in its initial basis. In September 2013, the Treasury issued final regulations (TD 9636, 9/19/13) providing capitalization rules for acquisition and production of tangible property. These regulations replace proposed and temporary regulations issued in 2011. The new regulations provide detailed guidance on the tax treatment of acquisition costs, as well as a deduction for de minimis acquisition costs in limited circumstances. (See Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-1(f).) These provisions are coordinated with IRC Section 263A which applies to capitalization requirements for inventory. The general rule for capital expenditures under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-1 provides that no deduction is allowed for x x any amount paid for new buildings or for permanent improvements or betterments made to increase the value of any property or estate or any amount paid in restoring property or in making good the exhaustion thereof for which an allowance is or has been made. Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-1(d) provides the following seven specific examples of capital expenditures: x x x x x x x An amount paid to acquire or produce a unit of real or personal tangible property. (See Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2.) An amount paid to improve a unit of real or personal tangible property. (See Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3.) An amount paid to acquire or create intangibles. (See Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4.) An amount paid or incurred to facilitate an acquisition of a trade or business, a change in capital structure of a business entity, and certain other transactions. (See Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-5.) An amount paid to acquire or create interests in land, such as easements, life estates, mineral interests, timber rights, zoning variances, or other interests in land. An amount assessed and paid under an agreement between bondholders or shareholders of a corporation to be used in a reorganization of the corporation or voluntary contributions by shareholders to the capital of the corporation for any corporate purpose. (See Section 118 and Reg. Sec. 1.118-1.) An amount paid by a holding company to carry out a guaranty of dividends at a specified rate on the stock of a subsidiary corporation for the purpose of securing new capital for the subsidiary and increasing the value of its stockholdings in the subsidiary. This amount must be added to the cost of the stock in the subsidiary. AMOUNTS PAID TO ACQUIRE OR PRODUCE TANGIBLE PROPERTY Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(d)(1) addresses amounts paid to acquire or produce a unit of real or personal property. Except for the de minimis rule discussed as follows, this rule does not change the treatment of items covered by other provisions except for Section 162(a) or Section 212 and the related regulations. 1 Generally these costs to acquire or produce tangible property must be capitalized. Tangible property 1 For example this rule does not override the rule under Sections 195 (startup costs) or 263A (UNICAP inventory). Also, materials and supplies are covered under Reg. Sec. 1.162-3. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-3 includes leasehold improvement property, land and land improvements, buildings, machinery and equipment, and furniture and fixtures. The relevant amounts paid include the invoice price, transaction costs as provided as follows, and costs for work performed prior to the date that the unit of property is placed in service. Eleven examples illustrate the general rule of Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2, two of which are reproduced in the following section with only minor editorial changes. Example 1-1 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(d)(2) Example 4 Acquisition or Production Cost X purchases and produces jigs, dies, molds, and patterns for use in the manufacture of Xps products. Assume that each of these items is a unit of property and is not a material and supply. X is required to capitalize the amounts paid to acquire and produce the jigs, dies, molds, and patterns. Example 1-2 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(d)(2) Example 11 Work Performed Prior to Placing the Property in Service In January Year 1, X purchases a new machine for use in an existing production line of its manufacturing business. Assume the machine is a unit of property and is not a material and supply. X pays amounts to install the machine, and after the machine is installed, X pays amounts to perform a critical test on the machine to ensure that it will operate in accordance with quality standards. On November 1, Year 1, the critical test is complete and X places the machine in service. X pays amounts to perform periodic quality control testing after the machine is placed in service. The amounts paid for the installation and the critical test performed before the machine is placed in service must be capitalized as amounts to acquire the machine. However, amounts paid for periodic quality control testing after X placed the machine in service are not required to be capitalized as amounts paid to acquire the machine. Costs to Defend Title Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(e) provides that amounts paid to defend or perfect title to real or personal property must be capitalized. Three examples are provided to illustrate this rule, one of which is reproduced in the following section with only minor editorial changes. Example 1-3 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(e)(2) Example 3 Amounts Paid to Challenge Building Line The board of public works of a municipality establishes a building line across Xps business property, adversely affecting the value of the property. X incurs legal fees in unsuccessfully litigating the establishment of the building line. The amounts X paid to the attorney must be capitalized because they were to defend Xps title to the property. 1-4 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Transaction Costs In general, amounts paid to facilitate the acquisition of real or personal property must also be capitalized (see Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(f)). Facilitative amounts must be included in the basis of the property acquired or produced. An expenditure facilitates the acquisition of real or personal property if paid in the process of investigating or otherwise pursuing the acquisition. This is a facts and circumstances determination. Whether the amount would be incurred absent the acquisition is relevant but not determinative. Capitalized transaction costs include but are not limited to the following items defined as inherently facilitative: x x x x x x x x x x x Transporting the property (for example, shipping fees and moving costs) Securing an appraisal or determining the value or price of property Negotiating the terms or structure of the acquisition and obtaining tax advice on the acquisition Application fees, bidding costs, or similar expenses Preparing and reviewing the documents that effectuate the acquisition of the property (for example, preparing the bid, offer, sales contract, or purchase agreement) Examining and evaluating the title of the property Obtaining regulatory approval of the acquisition or securing permits related to the acquisition, including application fees Conveying property between the parties, including sales and transfer taxes, and title registration costs Finders· fees or brokers· commissions, including amounts paid that are contingent on the successful closing of the acquisition Architectural, geological, engineering, environmental, or inspection services pertaining to the property Services provided by a qualified intermediary or other facilitator of an exchange under Section 1031 Special Rule for Acquisitions of Real Property Expect for the rules for inherently facilitative amounts, amounts paid in the process of investigating or otherwise pursuing the acquisition of real property, do not facilitate the acquisition if they relate to activities performed in the process of determining whether to acquire real property and which real property to acquire. See Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(f)(2)(iii)(A). Real and Personal Property Acquired in a Single Transaction Amounts paid by the taxpayer in the process of investigating or otherwise pursuing the acquisition of personal property facilitate the acquisition of such personal property even if such property is acquired in a single transaction that also includes the acquisition of real property subject to the rule for real property just discussed. Taxpayers are to use a reasonable allocation to determine which costs facilitate the acquisition of personal property and which costs relate to the acquisition of real property. See Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(f)(2)(iii)(B). Employee Compensation and Overhead Generally employee compensation and overhead are not capitalized as facilitative costs. However, taxpayers are allowed to elect to treat employee compensation or overhead as amounts that facilitate the acquisition of property. This election is done separately for each acquisition and is applicable to employee compensation or overhead, or both. The election is made by treating the amount as facilitating the acquisition on a timely (including extension) return. For flow-through entities the election is at the entity level. Revocation of the election requires a letter ruling and cannot be made or revoked through filing a change in method. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-5 Example 1-4 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(f)(4) Example 5 Scope of Facilitate X is in the business of providing legal services to clients. X is interested in acquiring a new conference table for its office. X hires and incurs fees for an interior designer to shop for, evaluate, and make recommendations to X regarding which new table to acquire. X must capitalize the amounts paid to the interior designer to provide these services because they are paid in the process of investigating or otherwise pursuing the acquisition of personal property. Example 1-5 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(f)(4) Example 6 Transaction Costs Allocable to Multiple Properties X, a retailer, wants to acquire land for the purpose of building a new distribution facility for its products. X considers various properties on highway A in state B. X incurs fees for the services of an architect to advise and evaluate the suitability of the sites for the type of facility that X intends to construct on the selected site. X must capitalize the architect fees as amounts paid to acquire land because these amounts are inherently facilitative to the acquisition of land. De minimis Safe Harbor Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-1(f) provides a safe harbor election under which taxpayers are not required to capitalize amounts paid for the acquisition or production (including any amounts paid to facilitate the acquisition or production) of a unit of property, if certain requirements are met. The specific requirements vary, depending on whether the taxpayer has an applicable financial statement as defined in Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)1(f)(4). Applicable financial statements include Form 10-K filed with the SEC, certified audited financial statements, and any financial statement (other than a tax return) required to be provided to the federal or state government or any federal or state agency. A taxpayer with an applicable financial statement may rely on the de minimis safe harbor if x x x the taxpayer has at the beginning of the tax year written accounting procedures treating as an expense for non-tax purposes amounts paid for property costing less than a certain dollar amount or that have a useful life of not more than 12 months; the taxpayer treats the amounts paid during the tax year as an expense on its applicable financial statement in accordance with its written accounting procedures; and the amount paid for the property does not exceed $5,000 per invoice (or per item if the invoice itemized costs). A taxpayer without an applicable financial statement must also meet the first two preceding requirements in order to rely on the de minimis safe harbor. The third requirement is modified by imposing a $500 per invoice or item threshold. Note: Effective for taxable years beginning on or after January 1, 2016, the Internal Revenue Service in Notice 2015-82 increased the de minimis safe harbor threshold from $500 to $2500 per invoice or item for taxpayers without applicable financial statements. In addition, the IRS will provide audit protection to 1-6 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited eligible businesses by not challenging the use of the $2,500 threshold for tax years ending before January 1, 2016 if the taxpayer otherwise satisfies the requirements of Treasury Regulation § 1.263(a)-1(f)(1)(ii). This de minimis rule does not apply to the following cases: x x x Amounts paid for property that is or is intended to be included in inventory property Amounts paid for land Amounts paid for certain rotable, temporary, and standby emergency spare parts Amounts paid to acquire or produce a unit of property that is a material or supply are subject to the rules of Reg. Sec. 1.162-3 unless the taxpayer elects the de minimis rule described above. If the taxpayer makes the de minimis safe harbor election, it also applies to all eligible materials and supplies. Property that the taxpayer uses the de minimis rule for is not treated as either a capital or Section 1231 asset at the time of sale or disposition. The safe harbor election is made annually by including a statement on the taxpayer·s timely filed original federal tax return for the year elected. If elected, the de minimis safe harbor must be applied to all amounts paid in the tax year for tangible property that meets the requirements under the safe harbor, including amounts paid for materials and supplies as discussed as follows. Example 1-6 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(f)(7) Example 3 De minimis Rule Taxpayer with Applicable Financial Statement X is a member of a consolidated group for federal income tax purposes. Xps financial results are reported on the consolidated applicable financial statements for the affiliated group. Xps affiliated group has a written policy at the beginning of Year 1, which is followed by X, to expense amounts paid for property costing less than $5,000. In Year 1, X pays $6,250,000 to purchase 1,250 computers at $5,000 each. X receives an invoice from its supplier indicating the total amount due ($6,250,000) and the price per item ($5,000). Assume that each computer is a unit of property. The amounts paid for the computers meet the requirements for the de minimis safe harbor. If X elects to apply the de minimis safe harbor for Year 1, X may deduct these amounts provided the amounts otherwise constitute deductible ordinary and necessary expenses incurred in carrying on a trade or business. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-7 Example 1-7 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(f)(7) Example 9 De minimis Rule with Materials and Supplies X is a corporation that provides consulting services to its customers. X has an applicable financial statement and a written accounting policy at the beginning of the taxable year to expense amounts paid for property costing $5,000 or less. In Year 1, X purchases 1,000 computers at $500 each for a total cost of $500,000. Assume that each computer is a unit of property and is not a material or supply. In addition, X purchases 200 office chairs at $100 each for a total cost of $20,000 and 250 customized briefcases at $80 each for a total cost of $20,000. Assume that each office chair and each briefcase is a material or supply. X treats the amounts paid for the computers, office chairs, and briefcases as expenses on its applicable financial statement. The amounts paid for computers, office chairs, and briefcases meet the requirements for the de minimis safe harbor. If X elects to apply the de minimis safe harbor in Year 1, X may deduct the amounts paid for the computers, the office chairs, and the briefcases provided the amounts otherwise constitute deductible ordinary and necessary expenses incurred in carrying on a trade or business. Treatment of Capital Expenditures Amounts that are required to be capitalized must be taken into account through a charge to capital account or basis, or in the case of property that is inventory in the hands of a taxpayer, through inclusion in inventory costs.2 Generally these amounts are recovered through the process of depreciation, cost of goods sold, or as an adjustment to basis when placed in service, sold, used or disposed. The rules provide two examples, which are reproduced with only minor editorial changes. Example 1-8 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(h)(2) Example 1 Recovery When Property Placed in Service X owns a 10-unit apartment building. The refrigerator in one of the apartments stops functioning, and X purchases a new refrigerator to replace the old one. X pays for the acquisition, delivery, and installation of the new refrigerator. Assume that the refrigerator is the unit of property, and is not a material or supply. X is required to capitalize the amounts paid for the acquisition, delivery, and installation of the refrigerator. The capitalized amounts are recovered through depreciation, which begins when the refrigerator is placed in service by X. 2 Again for inventory the reader is referred to Section 263A. 1-8 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 1-9 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(h)(2) Example 2 Recovery for Property Used in Production X operates a plant where it manufactures widgets. X purchases a tractor loader to move raw materials into and around the plant for use in the manufacturing process. Assume that the tractor loader is a unit of property and is not a material or supply. X is required to capitalize the amounts paid to acquire the tractor loader. The capitalized amounts are recovered through depreciation, which begins when X places the tractor loader in service. However, because the tractor loader is used in the production of property, per Section 263A the depreciation on the capitalized amounts must be capitalized to Xps property produced, and, consequently, recovered through cost of goods sold. Method Change and Effective Dates Changing to apply these rules is generally a method change governed by Sections 446 and 481. Taxpayers will need to follow the applicable procedure for obtaining consent. For many such changes, Revenue Procedure 2014-16, 2014-0 IRB 606, as modified by Rev. Proc. 2014-54, 2014-41 IRB 675 and Rev. Proc. 2016-29, 2016-21 IRB, provides procedures for obtaining automatic consent to change to accounting methods now available in the new regulations under Sections 162 and 263. The rules set forth in the new regulations under Section 263 are generally effective for tax years that begin on or after January 1, 2014. Four rules³the special rule for the acquisition of real property, the rule for employee compensation and overhead, the rule for inherently facilitative amounts, and the de minimis rule³apply to amounts paid or incurred (to acquire or produce property) after January 1, 2014 for tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2014. A taxpayer may elect to apply these provisions to tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2012. OTHER ACQUISITION-RELATED COSTS Real Property Taxes Real property taxes apportioned to or owed by the seller and paid by the purchaser are also included in the purchaser·s tax basis [Reg. Sec. 1.1012-1(b)]. Real property taxes apportioned to and paid by the purchaser related to periods subsequent to the purchase are typically deductible, either as ordinary and necessary business expenses (Section 162) or as an itemized deduction (Sections 63 and 164). Example 1-10 Real Property Taxes paid by Buyer Linus Corporation purchased land on which to construct a new manufacturing facility. It paid $200,000 cash to the seller, a purchase commission of $2,500, title fees of $1,000, and transfer taxes of $1,500. In addition, in order to gain clear title to the land Linus paid $3,000 of delinquent real estate taxes owed by the seller. Cost basis of the land equals $208,000 ($200,000 + $2,500 + $1,000 + $1,500 + $3,000). Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-9 For tax purposes, apportionment of real estate taxes between buyer and seller occurs under Section 164(d). If real property is sold during a real property tax year, tax for the portion of such tax year ending on the day before the date of sale is treated as imposed on the seller. Tax for the portion of such tax year beginning on the date of sale is treated as imposed on the buyer. Example 1-11 Property Tax Apportionment Simmons Corporation purchased a building on September 1 from Hemming Inc. The building is located in a county where the real property tax year is January 1 to December 31. For the current year, Hemming paid $25,000 of property tax on the building, prior to the sale. Of this amount, $16,644 (243/365 × $25,000) is considered a tax on the seller and $8,356 (122/365 × $25,000) is considered a tax on the buyer. Financing of Asset Acquisitions The acquisition cost of an asset need not be paid in cash in order to create basis. The amount of any liability incurred by the taxpayer to acquire the property is included in basis (Crane v. Commissioner, 331 U.S. 1 (1947), Reg. Sec. 1012-1). In addition, basis includes seller debt assumed by the buyer of property and debts to which the property continues to be subject after the acquisition, including nonrecourse debt (Revenue Ruling 69-77, 1969-1 C.B. 59). Because acquisition debt is included in the basis of the property when acquired, basis is not increased by subsequent principal payments on the debt [Doyal, 37 TCM 1279 (1978)]. Basis does not include debt incurred after acquisition that is secured by the property [Woodsam Associates, Inc., 198 F.2d 357 (2d Cir. 1952)]. Example 1-12 Acquisition Debt Givens Inc. acquired an office building. It made a down payment of $150,000 cash and financed the remainder of the purchase with a mortgage of $500,000. The mortgage is payable over a 30year term and bears a market rate of interest. The cost basis of the building equals $650,000 ($150,000 + $500,000). Example 1-13 Second Mortgage Debt Refer back to example 1-4. Two years after purchase of the office building, Givens obtained a second mortgage on the building for $50,000. The basis of the building is not increased by this additional borrowing. Costs of obtaining a loan, whether or not secured by a mortgage, are generally not deductible in the year in which the loan is negotiated. Instead, costs such as commissions, loan origination fees, escrow costs, and other such costs must be capitalized [see, for example, Detroit Consol. Theatres, Inc. v Comm. ¶41,403 PH Memo BTA, aff·d (1942, CA6) 30 AFTR 749]. If the property is used in a trade or business or held for the production of income, the capitalized loan costs can be deducted ratably over the life of the loan (Sections 162 and 212). Any unamortized balance may be deducted when the property is sold or the loan 1-10 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited paid in full [see S. & L. Bldg. Corp. (1930) 19 BTA 788]. The capitalized loan fees are not included in the basis of the acquired property, but constitute a separate intangible asset. Example 1-14 Loan Origination Fees Treadway Company paid $15,000 in loan origination fees to obtain a $1 million 15-year mortgage loan upon purchase of a new warehouse. Treadway must capitalize the loan fees and may deduct $1,000 per year as a business expense. Three years after acquisition of the warehouse, Treadway sold it and the purchaser assumed the remaining balance of the mortgage. Treadway may deduct the remaining $12,000 capitalized loan fees in the year of the sale. When a taxpayer issues a debt instrument as part of the consideration for a property acquisition, the amount of such debt included in the tax basis of the property is generally the stated principal amount of the debt. However, in certain circumstances, the amount of debt included in the property·s tax basis must be determined under the original issue discount (OID) rules of Section 1274. The OID rules are extremely complex. They are summarized here only to the extent necessary to explain their impact on the cost basis of acquired assets. Section 1274 applies to debt instruments issued as consideration for the sale or exchange of property when there is not adequate stated interest or, if there is adequate stated interest, the instrument·s stated redemption price exceeds the stated principal amount. Certain instruments are excluded from these requirements, including instruments with terms less than six months, instruments from sales of farms for less than $1 million, instruments from sales of personal residences, instruments from sales involving total payments of $250,000 or less, and publicly- traded instruments. Under Section 1274, the amount of a debt instrument included in the tax basis of acquired property equals the issue price of the debt, per Reg. 1.1012-1(g). If the debt instrument bears adequate stated interest, the issue price equals the stated principal amount, per Reg.1.1274-2(b)(1). If the debt instrument does not bear adequate stated interest, the issue price must be determined by calculating an imputed principal amount. The goal of the imputation process is to separate payments to be made under the debt instrument between principal and interest using an applicable federal rate instead of the stated interest amount. Exhibit 1-1 Imputed Versus Stated Principal Amount No OID: Imputed Principal Amount > Stated Principal Amount Imputed = Principal Amount < Stated Principal Amount = Issue Price OID: Issue Price Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-11 Example 1-15 Issue Price Chester Corporation acquired a building by issuing a debt instrument with a stated principal amount of $3 million, payable in equal annual installments over five years beginning one year from the date of sale. If the debt instrument bears adequate stated interest, its issue price is also $3 million, the entire amount of which will be included in the cost basis of the building. However, suppose that the debt instrument bears no stated interest. In this case, the annual installment payments required by the debt instrument, even though characterized as principal, economically represent both a repayment of borrowing (principal) and a payment for the use of the borrowed funds (interest). Under Section 1274, the imputed principal amount will be less than $3 million; this lower amount will be included in the cost basis of the building. As installment payments are made, a portion of such payments will be treated as interest for tax purposes, likely deductible under Section 162 as an ordinary and necessary business expense. The imputed principal amount is the sum of the present value of all payments due under the debt instrument, determined as of the date of the property acquisition. Present value is computed using the applicable federal rate, compounded semi-annually. Applicable federal rates are published monthly by the Treasury, and vary depending on the term of the debt instrument. The imputed principal amount is compared to the stated principal amount to determine if the debt instrument bears adequate stated interest. If the imputed principal amount is greater than or equal to the stated principal amount, there is adequate stated interest and the issue price equals the stated principal amount. If not, the issue price (and the amount of debt included in the basis of the property) is equal to the imputed principal amount. Amounts paid in excess of the issue price are considered interest, recognized over the life of the debt instrument. Example 1-16 Imputed Principal Amount Refer back to example 1-15, in which Chester Corporation acquired a building by issuing a debt instrument with a stated principal amount of $3 million, payable in equal annual installments over five years beginning one year from the date of sale. Assume that the debt instrument bears no stated interest. Further assume that on the date of the transaction, the mid-term (more than three years but not more than nine years) applicable Federal rate is 3 percent compounded semiannually. The imputed principal amount is computed as follows: Year 1-12 Amount Present Value 1 $ 600,000 $ 582,397 2 600,000 565,311 3 600,000 548,725 4 600,000 532,627 5 600,000 517,000 $3,000,000 $2,746,060 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 1-16 Imputed Principal Amount (continued) The imputed principal amount is $2,746,060, which is less than the stated principal amount. Therefore, the issue price and the cost basis of the building is $2,746,060. Each year, the amount of each payment considered interest is based on the 3 percent yield to maturity compounded semi-annually. KNOWLEDGE CHECK 1. In general, which amounts are not required to be capitalized to the basis of tangible property? a. b. c. d. Amounts paid for permanent improvements or betterments to real property. Amounts paid to facilitate an acquisition of a trade or business. Amounts paid to defend or perfect title to real property. Employee compensation and overhead costs related to the acquisition of property. 2. Real property taxes apportioned to or owed by the seller and paid by the purchaser are a. b. c. d. Included in the purchaser·s tax basis. Deductible by the purchaser. Deductible by the seller. Not deductible or included in tax basis. 3. In determining cost basis of an asset, which statement regarding debt financing is correct? a. b. c. d. Basis is increased as the buyer makes payments on debt incurred to acquire property. Basis includes seller debt assumed by the buyer of property. Basis includes debt incurred after acquisition that is secured by the property. Loan fees and other costs of obtaining a loan are included in the cost basis of the financed asset. OTHER CAPITALIZATION ISSUES Restaurant Smallwares The IRS has issued a safe harbor revenue procedure that allows taxpayers in the restaurant or tavern business to currently deduct the cost of smallwares. Smallwares are defined as glassware, flatware, dinnerware, pots and pans, tabletop items, bar supplies, food preparation utensils, storage supplies, service items, and small appliances that cost $500 or less. The IRS will not assert that these items are depreciable or capital assets. A taxpayer desiring to change its method of accounting under this new procedure must follow the automatic accounting method change provisions of Rev. Proc. 2011-14, Appendix Sec. 3.03(2011-1 C.B. 330); a net negative adjustment may be claimed entirely in the year of change (Rev. Proc. 2002-19, 2002-1 C.B. 696). Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-13 Restaurant or Retail Establishment Remodel or Refresh Costs The IRS has issued a revenue procedure providing a safe harbor method of accounting to determine whether costs incurred to remodel or refresh a restaurant or retail establishment are currently deductible or must be capitalized as improvements or production costs. The safe harbor method minimizes the need to perform a detailed factual analysis of each cost incurred during a remodel-refresh project. The revenue procedure also provides procedures for obtaining automatic consent to change to the safe harbor method of accounting (Rev. Proc. 2015-56, 2015-49 IRB 11/19/2015). Truck Tires The IRS has provided a safe harbor method of accounting for the cost of original and replacement tires for trucks used in business activities. This method, known as the original tire capitalization method, allows the business to immediately expense any replacement tires, provided that the taxpayer has treated the original tires on the vehicle at acquisition as part of the capitalized cost of the truck. The original tires must be depreciated using the same method and recovery period applicable to the truck. No adjustment is made for the cost of the original tires that were replaced, but the replacement tires are allowed immediate deductibility. This procedure was effective for tax years ending on or after December 31, 2001, with the automatic accounting method change procedures permitted to allow taxpayers to convert to this method (Rev. Proc. 2002-27, 2002-1 C.B. 802). Automobile Dealer Parts Inventory The IRS has issued a safe harbor procedure that allows vehicle dealerships to maintain their vehicle parts inventory at replacement cost rather than actual cost. The revenue procedure applies to any business selling vehicle parts at retail that has an authorized agreement with one or more vehicle manufacturers or distributors to sell new automobiles or new light, medium, or heavy-duty trucks. These businesses are allowed to use a replacement cost method in conjunction with either a FIFO or LIFO method of accounting for the vehicle parts inventory. A taxpayer not presently using this method may use the automatic accounting method change provisions to adopt this safe harbor method for any tax year ending on or after December 31, 2001 (Rev. Proc. 2011-14, Appendix Sec. 6.05, 2011-1 C.B. 330). In Rev. Proc. 2008-23, IRB 2008-12, the IRS provided an alternative dollar-value LIFO pooling method, which is labeled the Vehicle Pool Method, for retail dealers and wholesale distributors of cars and lightduty trucks. This method allows for the pooling of both new cars and new light duty trucks into the same new pool and for pooling of both old cars and old light duty trucks into the same old pool. Sec. 22.08 of the Appendix to Rev. Proc. 2011-14 also provides details regarding mechanics of changing to this method. Removal of Architectural and Transportation Barriers A business may elect to currently deduct the costs incurred to remove architectural and transportation barriers to the handicapped and elderly in any facility or public transportation vehicle owned or leased for use in a trade or business. The deduction is limited to $15,000 per taxpayer per tax year, with any remainder capitalized and depreciable (section 190). Note: Eligible small businesses can take a credit for the costs of providing access for disabled individuals. However, no double benefit is allowed. Thus, taxpayers electing the Section 190 deduction cannot take advantage of any other credit or deduction for the same expenditure. 1-14 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Removal of Depreciable Assets The IRS has ruled that a business does not need to capitalize the costs of removing a depreciable asset if the costs are incurred in connection with the installation or production of a replacement asset. The ruling involved a telephone company that incurred costs to remove existing telephone poles. These costs were not capitalizable as part of the costs of the replacement poles. The removal costs were considered allocable to the removed assets, and thus did not relate to an asset with a useful life extending beyond the taxable year (Revenue Ruling 2000-7, 2000-1 C.B. 712. See also Appendix Sec. 10.03 to Rev. Proc. 201114, as modified by Rev. Proc. 2014-17, 2014-12 IRB 661). Demolitions Capitalization is required as part of the basis of land for all expenses sustained for demolition of any VWUXFWXUHLQFOXGLQJDFHUWLILHGKLVWRULFVWUXFWXUH 6HFWLRQ% )LQDOUHJXODWLRQVGHILQHD´VWUXFWXUHµIRU these purposes as a building and its structural components as those terms are defined in Reg. Sec. 1.481(e)(1) and (e)(2). Also, the rules of Section 280B do not apply to the demolition of other inherently permanent structures, such as oil and gas storage tanks, blast furnaces, and coke ovens [Reg. Sec. 1.280B1(b); Reg. Sec. 1.48-1(e)(1)]. Example 1-17 Demolition Costs Lexco, Inc. acquires an adjacent parcel of real estate to serve its future expansion needs at a cost of $600,000. This property is primarily vacant land, but includes an older residence that is in rental status. Lexco allocates its purchase price as $500,000 attributable to the land and $100,000 allocable to the rental residence, and begins depreciating the residence. Several years later, at a time when the adjusted tax basis of the residence is $90,000, Lexco demolishes the building. The adjusted tax basis of the building must be capitalized to the land account under Section 280B. The IRS has provided a safe-harbor rule under which a substantial structural modification of a building will not be treated as a demolition if (1) at least 75 percent of the existing external walls are retained in place as internal or external walls, and (2) at least 75 percent of the existing internal structure framework is retained in place. In the case of a certified historic structure, the modification must also be part of a ´FHUWLILHGUHKDELOLWDWLRQµXQGHU6HFWLRQ F & 1RWHWKDWHYHQLIWKHFRVWVDQGORVVHV sustained on account of the modification satisfy this rule, they are deductible only if they satisfy all other relevant Code provisions, such as Section 162 (ordinary and necessary) and Section 263A (UNICAP) (Rev. Proc. 95-27, 1995-1 C.B. 704). Note: A loss sustained before demolition (for example, as a result of abnormal retirement because of a casualty or extraoUGLQDU\REVROHVFHQFH LVGHGXFWLEOHEHFDXVHLWLVQRWLQFXUUHG´RQDFFRXQWRIµWKH demolition [DeCou, 103 TC 80 (1994)]. The Third Circuit distinguished DeCou in a later case where the taxpayer, whose building had been vandalized and found to contain asbestos, was held not to have incurred a loss prior to demolition. Unlike DeCou, the taxpayer did not claim his loss in the year the damage occurred (1988), but instead claimed it in the year of demolition (1991) [Gates, 98-2 USTC ¶50,814 (3rd Cir. 1998)]. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-15 Garment Supplier The Tax Court has allowed an industrial uniform and garment supply business to deduct the cost of garments when placed in service. The IRS had attempted to require the business to capitalize garments and depreciate them over three to five years, depending on the type of property. The court found that the garments, towels, and linens that the business furnished to customers had a useful life of approximately one year or not substantially in excess of one year, with a constant turnover of these items for wear and tear, obsolesce, or customer design changes. The Tax Court noted that the physical life of these items may have been in excess of one year, but that within this business the estimated useful life was approximately one year (Prudential Overall Supply v. Comm., TC Memo 2002-103, 4/23/2002). LUMP SUM PURCHASES OF BUSINESS ASSETS When a single business asset is acquired, application of the rules discussed previously determines that asset·s initial tax basis. However, what if the taxpayer acquires all of the assets of an existing business in a taxable transaction? In that case, acquisition cost of this group of assets must somehow be allocated among the assets acquired, in order to determine allowable cost recovery and any gain or loss on subsequent dispositions. The allocation of a lump sum purchase price to the acquired assets of an existing business is determined under Section 1060. 6HFWLRQDSSOLHVWRDQ\´DSSOLFDEOHDVVHWDFTXLVLWLRQµGHILQHGDVDQ\WUDQVIHURIDVVHWVFRQVWLWXWLQJD trade or business for which the acquirer tax basis in the assets is determined wholly by the consideration paid for the asset. In other words, the acquisition is a taxable purchase transaction in which the assets have a cost basis. If the assets constitute a trade or business in the hands of either the seller or the buyer, Section 1060 applies. Example 1-18 Applicable Asset Acquisition Coliseum Corporation paid $1 million to acquire the equipment, receivables, and other assets used by Rome Associates in its technology consulting business. Coliseum does not plan to continue Romeps consulting business but instead will use Romeps assets in Coliseumps existing technology development business. If these assets constituted a trade or business for Rome, the acquisition is subject to Section 1060 even though Coliseum will not continue Romeps historic business but will use the assets in Coliseumps existing business. Example 1-19 Not an Applicable Asset Acquisition Windy City Inc. acquired 10 pieces of office furniture from Office Delux, a local retailer, for a total purchase price of $35,000. The office furniture is considered inventory for Office Delux, and thus does not constitute a trade or business of the seller. Windy City will use the office furniture in its existing business. However, the furniture alone does not constitute a trade or business for Windy City. The allocation of the purchase price of the furniture is not subject to Section 1060. 1-16 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Purchase Price Allocation The regulations under Section 1060 divide all assets into seven classes, as follows: x x x x x x x Class I: Cash and cash equivalents Class II: Marketable securities, certificates of deposit, and foreign currency Class III: Accounts receivable, mortgage receivables, and credit card receivables Class IV: Inventory and stock in trade Class V: All other tangible assets Class VI: Identifiable intangible assets other than goodwill and going concern value Class VII: Goodwill and going concern value The allocation of purchase price to these assets uses the residual method, beginning with Class I and continuing on through each class up through Class VI. Any purchase price not allocated to assets in Classes I through VI (the residual), is allocated to Class VII, goodwill. Total consideration paid by the purchaser is allocated first to Class I assets based on their aggregate fair market value, then to Class II assets, and so on. Within each class, purchase price is allocated to each asset equal to (but not greater than) fair market value. Under this method, any premium paid by the purchaser in excess of the fair market value of tangible and identifiable intangible assets is treated as goodwill rather than allocated proportionately among the other assets. Example 1-20 Purchase Price Allocation Refer back to example 1-18, in which Coliseum Corporation paid $1 million to acquire the equipment, receivables, and other assets of Rome Associates. The asset classes and fair market values of the acquired tangible and identifiable intangible assets are as follows: Asset Class FMV Accounts receivable Class III $450,000 Equipment Class V 75,000 Proprietary computer software Class VI 200,000 Trademarks Class VI 10,000 Total FMV of identifiable assets $735,000 Under Section 1060, Coliseum will allocate $450,000 of purchase price to Class III assets, accounts receivable, $75,000 to Class V assets, equipment, and $210,000 to Class VI assets. Within Class VI, $200,000 will be allocated to proprietary computer software and $10,000 is allocated to trademarks. The remaining purchase price, $265,000 ($1,000,000 t $735,000), is allocated to goodwill. The total purchaser consideration to be allocated to an asset purchase often includes acquisition costs such as appraisal fees, transfer taxes, and title costs. Reg. Sec. 1.1060-1(c)(3) addresses the treatment of Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-17 such costs in allocating purchase price in a lump sum asset acquisition. When such costs are specifically identifiable with a particular asset, they are taken into account in determining the purchase price of that asset and are not included in consideration to be allocated under the residual method. General costs associated with the asset acquisition as a whole (such as non-specific appraisal or accounting fees) are included as part of consideration allocated using the residual method. Example 1-21 Allocation of Transaction Costs Pritchard Corporation acquired the business of Bender for $1 million. Pritchard incurred $20,000 in appraisal costs to determine the value of the assets, and $2,500 of real property transfer taxes associated with the acquisition of Benderps building. The asset Classes and fair market values of the acquired tangible and identifiable intangible assets are as follows: Asset Class FMV Accounts receivable Class III $150,000 Equipment Class V 50,000 Building Class V 750,000 Total FMV of identifiable assets $950,000 Under the residual method, Pritchard will allocate consideration of $1,020,000 ($1 million purchase price + $20,000 general appraisal costs). The real property transfer tax of $2,500 will be specifically identified and allocated to the building. As a result, Pritchardps cost basis in the acquired assets is as follows: Asset Accounts receivable Equipment $ 150,000 50,000 Building 752,500 Goodwill 70,000 Total cost basis $1,022,500 As part of an asset acquisition, the seller and purchaser may agree in writing on the allocation of purchase price or the fair market value of the assets to be transferred. In that case, Reg. Sec. 1.1060-1(c)(4) provides that the parties will be bound to such agreement for purposes of Section 1060, absent a claim of fraud, duress, undue influence or an admissible error. The IRS, however, is not so bound, and may challenge the allocation or values arrived at in the written agreement. 1-18 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Planning for Purchase Price Allocations As noted above, purchase price allocation under Section 1060 is controlled by the fair market value of acquired assets. Appraisals or other evidence of fair value are critical to this allocation. To the extent such measures provide a range of values, taxpayers should carefully consider the future tax consequences of this initial allocation. Generally, purchasers of assets prefer to allocate purchase price to those items whose cost will be recovered sooner rather than later. For inventory, cost is recovered on sale, typically within a short period of time. For depreciable assets, cost is recovered over the asset·s depreciable life. Thus, personal property costs are recovered faster than real property costs. Costs allocated to land are not depreciable and are only recovered on disposition. Finally, costs of Class VI and Class VII (purchased intangible assets) are recovered over 15 years under Section 197. Reporting Requirements 7KHVHOOHUDQGWKHSXUFKDVHUPXVWILOH)RUP´$VVHW$FTXLVLWLRQ 6WDWHPHQWµZLWKWKHLULQFRPHWD[ returns for the taxable year in which an applicable asset acquisition occurs. SELF-CONSTRUCTED ASSETS At times taxpayers may choose to construct assets needed in their business rather than acquire them from others. Under Section 263A, the cost basis of constructed assets includes the direct construction costs and a portion of the taxpayer·s indirect costs properly allocable to the property. Section 263A applies to real and tangible personal property produced by a taxpayer for use in its trade or business or for sale to its customers. The section also applies to real or personal property acquired by the taxpayer for resale, unless the taxpayer·s average annual gross receipts over the preceding three taxable years were $10 million or less. Also note that property produced for the taxpayer under a contract with another party is treated as property produced by the taxpayer to the extent the taxpayer makes payments or otherwise incurs costs with respect to the property. Example 1-22 Self-Constructed Assets Big Corporation has expanded its operations and requires a larger space for its corporate headquarters. After searching in vain for an existing building that meets its needs, Big decides to build a new corporate office building. If Big constructs the building using its own personnel, such construction is subject to the capitalization rules of Section 263A. If Big instead contracts with a construction company to build its new headquarters, the project is still subject to Section 263A as Big makes payments under the contract or incurs other costs related to the construction project. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-19 Direct Costs The following are examples of direct costs included in the cost basis of constructed property or property acquired for resale [see Reg. Secs. 1.263(a)-2, 1.263A-1(e)(2)]: x x x x x Architectural services and design costs. Cost of materials that become an integral part of the constructed property. Cost of materials that are consumed in the ordinary course of production associated with particular property produced. Costs of labor associated with particular property produced. For this purpose, labor encompasses full-time and part-time employees, as well as contract employees and independent contractors. Direct labor costs include all elements of compensation other than employee benefit costs (such as pension contributions, insurance and workers compensation costs, and other fringe benefits). Employee benefits are generally included in indirect costs, as discussed further as follows. Direct labor costs include basic compensation, overtime pay, vacation pay, holiday pay, sick leave, payroll taxes, and payments to a supplemental unemployment benefit plan. For resellers, the acquisition costs of property acquired for resale. Indirect Costs Taxpayers subject to Section 263A also must capitalize indirect costs properly allocable to property produced or acquired for resale. Indirect costs are properly allocable when the costs directly benefit or are incurred by reason of the production or resale activities. Indirect costs may be allocable to both production and resale activities, as well as to other activities that are not subject to Section 263A. The following are examples of indirect costs that may be allocable under Section 263A and included in the cost basis of constructed property or property acquired for resale [see Reg. Sec. 1.263A-1(e)(3)]: x x x x x x x x x x x Indirect labor costs. Indirect labor includes costs of full-time and part-time employees, as well as contract employees and independent contractors, not directly involved in production activities. Officers· compensation Pension and employee benefits costs Indirect materials costs Purchasing, handling and storage costs Cost recovery of production facilities and equipment Rent, insurance, utilities, repairs and maintenance costs related to production facilities or equipment Taxes, other than income taxes, to the extent attributable to labor, materials, supplies, equipment, land, or facilities used in production or resale activities License and franchise costs for rights associated with property produced or acquired for resale Qualified interest Capitalizable service costs Qualified interest includes interest on debt incurred or continued during the production period to finance production of certain real or tangible personal property with a recovery class life of 20 years or more. In addition, the property must have an estimated production period exceeding two years, or an estimated production period exceeding one year and a cost exceeding $1 million. In determining the amount of interest included in the basis of constructed property, interest on any debt directly attributable to construction expenditures of that asset are assigned directly to the property. Interest on other debt is also assigned to the constructed property to the extent the taxpayer·s interest costs could have been reduced had production costs (not directly financed) not been incurred. This 1-20 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited interest assignment is determined using the avoided cost method of Reg. Sec. 1.263A-9. Finally, interest on debt related to assets used in the production process is also subject to capitalization in the basis of constructed property. Example 1-23 Construction Period Interest Big Corporation was engaged in the construction of an office building during the entire taxable year. Production expenditures totaled $3 million. Indebtedness directly traced to the construction during the construction period totaled $1,800,000, bearing interest at 5 percent. In addition to this traced debt, Big incurred other debt during the construction period of $2 million that bears interest at 6 percent. Big is required to capitalize interest on the traced debt amount of $90,000 ($1,800,000 × 5%). Under the avoided cost method, Big is also required to capitalize interest on the other debt. The total interest on the other debt is $120,000. However, the amount to be capitalized is limited to interest on excess construction expenditures. Excess expenditures are computed by comparing average construction expenditures during a computation period over the traced debt amount for that period.3 Assume that average construction expenditures for the taxable year were $1.5 million and average traced debt was $1 million, resulting in excess construction expenditures of $500,000. Big must capitalize interest on its other debt equal to $30,000 ($500,000 excess expenditures × 6% interest rate on other debt). Construction period interest capitalized during the year totals $120,000 ($90,000 interest on traced debt + $30,000 interest on other debt). Service costs are indirect costs (for example, general and administrative costs) identified specifically with a service department or function. Service departments are administrative, service, or support departments such as personnel, accounting, data processing, security, legal, and other similar departments. Service costs are capitalizable only when they directly benefit or are incurred by reason of the performance of the taxpayer·s production or resale activities. Service costs that do not directly benefit or are not incurred by reason of the performance of the production or resale activities of the taxpayer, are not required to be capitalized under section 263A. Deductible service costs generally include costs incurred by reason of the taxpayer·s overall management or policy guidance functions. In addition, deductible service costs include costs related to marketing, selling, advertising, and distribution activities. Mixed service departments are those incurring both capitalizable and deductible service costs. Costs associated with mixed service departments must be allocated between capitalization and deductibility, using one of four methods provided in the regulations. 3 The computation period is typically the taxable year, although taxpayers may choose a shorter period. Within the computation period, excess expenditures are computed at several measurement dates (at least quarterly) and averaged over those dates. See Reg. Sec. 1.263A-9(c) for a more complete description of the computation of the excess expenditure amount. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-21 Example 1-24 Service Costs Reed Inc. is a large regional distribution company, which acquires property for resale. In addition, during the current taxable year Reed contracted to build a major addition to its distribution facilities. Both the construction of the addition and Reedps resale activities are subject to the cost capitalization rules of Section 263A. Reedps corporate operations include a large in-house accounting and finance department. Costs associated with this department are service costs, within the meaning of Reg. Sec. 1.263A-1(e)(4), and must be examined to determine which such costs are capitalizable and which are deductible. Per the regulations, capitalizable accounting and finance department service costs include cost accounting, accounts payable, disbursements, and payroll functions (but excluding accounts receivable and customer billing functions). Deductible service costs related to the accounting and finance department include costs related to financial, accounting, and legal officers (including their immediate staff), provided that no substantial part of the cost of such departments or functions benefits a particular production or resale activity; strategic business planning; general financial accounting; general financial planning (including general budgeting); financial management (including bank relations and cash management); internal audit; and tax services. Because Reedps accounting and finance department incurs both capitalizable and deductible service costs, it is considered a mixed service cost department. The portion of the departmentps costs subject to capitalization will be determined using one of the allocation methods specified in the regulations. As a result of these allocations, some portion of the costs associated with the accounting and finance department will be capitalized to the inventory cost of property acquired for resale; some portion will be capitalized to the tax basis of the new distribution facilities. Under Reg. Sec. 1.263A-1(e)(3)(iii), the following indirect costs are not subject to capitalization under Section 263A: x x x x x x x x x Marketing, selling, advertising and distribution costs Research and experimental costs Section 179 deductions Bad debt deductions Income taxes Strike expenses Warranty and product liability insurance costs On-site storage and warehousing costs Deductible service costs Taxpayers subject to Section 263A must make a reasonable allocation of indirect costs between production, resale, and other activities. The regulations under Section 263A, at 1.263-1(f) provide detailed guidance on acceptable methods for allocating indirect costs among the taxpayer·s activities and to specific items of property. The regulations provide flexibility to taxpayers in making allocation choices. However, such choices once made constitute accounting methods choices that generally cannot be changed without IRS permission. Acceptable allocation methods include specific identification, burden rate, standard cost, and any other method meeting certain total cost consistency requirements detailed in 1-22 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited the regulations. A detailed discussion of the application of these allocation methods is beyond the scope of this course. KNOWLEDGE CHECK 4. The cost basis of self-constructed assets includes a. Only direct construction costs, including direct labor and direct materials. b. Both direct costs and a portion of the taxpayer·s indirect costs properly allocable to the property. c. An allocable share of income taxes associated with the business constructing the assets. d. Only costs of construction undertaken directly by the taxpayer rather than through contract. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-23 Initial Basis of Property Acquired in an Exchange Transaction Taxpayers may acquire business property in exchange for other non-cash assets. Such a transaction involves both the disposition of property and the acquisition of replacement property. Absent the application of special tax provisions, the disposition would be taxable, resulting in the recognition of realized gain or loss, and the acquisition of the replacement property would result in tax basis equal to the property·s cost, under the rules previously discussed. However, many such transactions are nontaxable under a host of special tax provisions. When these provisions apply, some or all of the gain or loss realized on the property disposition is not currently recognized. In addition, the tax basis of the replacement property generally will not equal its cost. Instead, the tax basis of the acquired property will be based, in whole or in part, on the adjusted tax basis of the property given up in the exchange. Such tax basis is typically referred to as substituted basis. Example 1-25 Basis in a Nontaxable Exchange Versus a Taxable Exchange Flack Inc. transferred land (Property A) with a fair market value of $50,000 and an adjusted basis of $28,000 to Jennings Corporation in exchange for other land (Property B) with a fair market value of $50,000. If this transaction does not qualify for nontaxable exchange treatment, Flack recognizes a gain of $22,000 on the disposition of Property A. The cost basis of Property B is $50,000. If the transaction qualifies as a nontaxable exchange, Flack will not recognize its $22,000 realized gain. The basis of Property B is $28,000, a substituted basis equal to the basis of Property A. This chapter does not discuss the requirements for or details of the nontaxable exchange provisions. Instead, it focuses on the impact of such exchanges on the tax basis of property acquired in the exchange transaction. The substituted basis rules apply to transactions qualifying under the following exchange provisions:4 x x x x Section 351: exchanges of property for corporate stock Section 1031: like-kind exchanges Section 1033: involuntary conversions Section 1091: wash sales While these transactions are commonly referred to as nontaxable exchanges, this label is somewhat misleading. Gains and losses realized on most nontaxable exchanges do not escape recognition permanently. Instead, the substituted basis rule ensures that unrecognized gains and losses are merely deferred until some future time. The substituted basis rule embeds the unrecognized gain or loss in the basis of the qualifying property received. The unrecognized gain or loss is later recognized when the qualifying property received in the exchange is disposed of in a taxable transaction or subject to cost recovery through depreciation, amortization, or depletion. 4 Other provisions, such as Section 721, provide nontaxable treatment with slight variations to the substituted basis rule discussed herein. 1-24 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 1-26 Subsequent Disposition of Exchange Acquisition Refer back to example 1-25. Three years after the exchange, Flack sells Property B for $60,000. If the exchange did not qualify for nontaxable treatment, Flack recognizes $10,000 of gain on the sale of Property B. However, if the exchange qualified as nontaxable, Flack recognizes $32,000 of gain on the sale of Property B. This gain includes the $22,000 of unrecognized gain on the disposition of Property A and the $10,000 increase in value of Property B while held by Flack. Through the substituted basis rule, Flackps gain on the disposition of Property A was deferred for three years and recognized on the sale of Property B. When a nontaxable exchange involves only a transfer of qualifying property in exchange for other qualifying property,5 the substituted basis rule is simple: the basis of qualifying property received in the exchange equals the basis of the qualifying property given [see Section 358 (which determines shareholder basis in a Section 351 exchange), Section 1031(d), Section 1033(d), and Section 1091(d)]. However, if the otherwise nontaxable exchange involves cash, nonqualifying property, or relief of liabilities, the substituted basis rule must be modified to account for the impact of these elements of the transaction. Under Sections 358(a)(1) and 1031(d), the basis of qualifying property received in a nontaxable exchange is computed as follows: Basis of property surrendered in the exchange + Gain recognized on the exchange ² Loss recognized on the exchange ² Fair market value of cash or nonqualifying property received in the exchange = Basis of qualifying property acquired in the exchange 7KHGHILQLWLRQRI´TXDOLI\LQJSURSHUW\µGHSHQGVRQWKHH[FKDQJHSURYLVLRQ)RUH[DPSOHXQGHU6HFWLRQ nonrecognition treatment applies only when property held for productive use in a trade or business or for investment is exchanged solely for property of like kind which is to be held either for productive use in a trade or business or for investment. Regulations under Section 1031 provide detailed guidance in determining when exchange property is of ´OLNHNLQGµ 5 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-25 Example 1-27 Boot in a Nontaxable Exchange Rondo Inc. transferred machinery with a tax basis of $3,000 and a fair market value of $4,300 to Hardy Corporation in exchange for machinery with a fair market value of $3,800 and $500 cash. Rondops realized gain on the transaction is $1,300 ($3,800 + $500 total consideration received t $3,000 tax basis in machinery surrendered). Assuming the transaction qualifies as a like-kind exchange, Rondo will recognize $500 of gain as a result of the receipt of cash. Rondops basis in the machinery received in the exchange is $3,000 ($3,000 basis of machinery surrendered + $500 gain recognized t $500 cash received). Suppose that Rondo received in the exchange machinery with a fair market value of $2,800 and $1,500 cash. Rondo would recognize its entire $1,300 realized gain on the exchange. Its basis in the machinery received in the exchange is $2,800 ($3,000 basis of machinery surrendered + $1,300 gain recognized t $1,500 cash received). When part of the consideration received in an exchange transaction is the assumption of taxpayer liabilities by the other party to the exchange, Sections 358(d) and 1031(d) generally treat that liability assumption in the same manner as cash received in the exchange. Example 1-28 Liabilities as Boot Dive Corporation transferred a building with tax basis of $200,000 subject to a mortgage of $150,000 to Sail Corporation in exchange for land with a fair market value of $340,000. Sail assumed liability for the mortgage on the building as part of the exchange. Diveps total consideration received in the exchange is $490,000 ($340,000 fair market value of land received + $150,000 relief of liabilities), resulting in a realized gain of $290,000. Dive will recognize $150,000 of gain on the transaction. Its tax basis in the land received is $200,000 ($200,000 basis of building surrendered + $150,000 gain recognized t $150,000 debt relief). The substituted basis rule for involuntary conversions is modified slightly. Section 1033 provides for nonrecognition of gain when property disposed of in an involuntary conversion is replaced with property similar or related in service or use within two years. Losses on involuntary conversions are not deferred by Section 1033 and are fully recognized in the year incurred. Under Section 1033(b)(2), the basis of the replacement property equals the cost of such property decreased by gain not recognized on the involuntary conversion. 1-26 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 1-29 Involuntary Conversion Travel Corporation owned a warehouse with a tax basis of $300,000 that was destroyed in a flood. Travel received an insurance reimbursement for its loss of $400,000, resulting in a realized gain of $100,000 on the involuntary conversion. If Travel purchases qualifying replacement property within two years at a cost of $400,000 or more, the gain is not recognized. Assume Travel paid $460,000 for qualifying replacement property. Its tax basis in the replacement property is $360,000 ($460,000 cost t $100,000 gain not recognized on the involuntary conversion). Assume instead that Travel paid $380,000 for qualifying replacement property. Because it did not reinvest the entire amount of the insurance reimbursement, it will recognize $20,000 of gain on the involuntary conversion. Its tax basis in the replacement property is $300,000 ($380,000 cost t $80,000 gain not recognized). The substituted basis rule for wash sales is similar to that for involuntary conversions. Section 1091 disallows a deduction for realized losses on stock and securities sales when substantially similar stock or securities are acquired within 30 days before or after the sale. Under Section 1091(d), the basis of the acquired property equals its cost increased by the disallowed loss. Section 1091 does not apply to gains, which are fully recognized in the year of the disposition. Example 1-30 Wash Sale On June 10, Ark Inc. sold stock with a tax basis of $1,500 for $1,200. On July 1, Ark purchased substantially similar stock for $1,100. Under Section 1091, Ark will not be permitted to recognize the $300 realized loss on the sale. Its tax basis in the shares acquired is $1,400 ($1,100 cost + $300 disallowed loss). KNOWLEDGE CHECK 5. The tax basis of property acquired as part of a nontaxable exchange equals a. b. c. d. Zero. Cost. A substituted basis. The fair market value of the property on the date of the exchange. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-27 Adjusted Tax Basis The variety of tax rules discussed in this chapter assist taxpayers in determining the initial tax basis of business assets, as well as determining the need to increase tax basis as a result of improvements to business property. These capitalized amounts are critical to computing allowable cost recovery of business assets, via depreciation, depletion, or amortization. However, when property is sold or otherwise disposed of, the adjusted tax basis of the property determines resulting gain or loss on sale. Required adjustments to tax basis are detailed in Section 1016. These basis adjustments are applied to the initial basis of the property, whether a cost or substituted basis. The adjustments commonly applicable to business property are as follows: x x Basis is increased for expenditures properly chargeable to a capital account. Such expenditures include those improvements capitalized under Section 263(a). Basis is reduced by depreciation, depletion, and amortizable deductions allowed or allowable in computing taxable income. Example 1-31 Adjusted Tax Basis Hall Associates recently sold a warehouse used in its business. The original cost of the warehouse, including capitalized purchase costs, was $450,000. During the time Hall owned the property, it made improvements totaling $50,000 that were capitalized under Section 263(a). In addition, it properly claimed depreciation on the warehouse up to the date of sale totaling $187,000. Hallps adjusted basis in the warehouse is $313,000 ($450,000 + $50,000 t $187,000). The basis reduction for depreciation, depletion, and amortization is the greater of amounts allowed as deductions in computing taxable income or the amount allowable, even if not claimed as a deduction. Example 1-32 Depreciation Allowed or Allowable Willis Corporation acquired property in 2010 for $100,000. Through 2016, Willis claimed $35,000 of depreciation on the property using straight-line MACRS. The allowable amount using straight-line MACRS for 2010 through 2016 is $43,000 and the allowable amount using accelerated MACRS is $51,000. Willisp adjusted basis in the property is $57,000 ($100,000 t $43,000), and not $65,000 or $49,000. Although Willis improperly applied straight-line MACRS in calculating its depreciation deductions, its adjusted basis is computed using the chosen method because it is a proper method. Rev. Proc. 2004-VROYHVWKH´DOORZHGRUDOORZDEOHµWUDSWKDWFRXOGDULVHZKHQDWD[SD\HUGLVSRVHGRIDQ asset but had not properly claimed all permissible depreciation. Rev. Proc. 2004-11 allows a taxpayer, in the year of disposition of an asset, to file a Form 3115 automatic consent accounting method change to claim all prior omitted depreciation in the year of disposition (Rev. Proc. 2004-11, 2004-1 CB 211, as modified by Rev. Proc. 2007-16, 2007-1 CB 358). 1-28 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 1-33 Disposition of Improperly Depreciated Property Refer back to example 1-23. If Willis disposes of the asset in 2016 and files an appropriate Form 3115, it can claim $8,000 of additional depreciation on the property on its return as filed for the year of disposition. The adjusted basis of business property captures the tax history of the asset. It takes into account the expenditures of business resources to acquire and improve the property, and the allowance of deductions over the life of the property through cost recovery. Unrecovered basis at the date of sale is effectively recovered as a return of investment, reducing resulting gain (or producing deductible loss) on disposition of the asset. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 1-29 1-30 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Chapter 2 MATERIALS, SUPPLIES, REPAIRS, AND IMPROVEMENTS LEARNING OBJECTIVES After completing this chapter, you should be able to do the following: x x x Recall the tax treatment of expenditures for materials and supplies. Distinguish between deductible repairs and capitalized improvements. Recall recent changes in the tax rules to classification of expenditures as materials, supplies, repairs, and improvements. INTRODUCTION This chapter addresses the tax treatment of common business expenditures for materials and supplies used in a business, as well as the treatment of costs incurred to maintain, repair, or improve business assets. In each case, the primary tax question is whether the expenditure is currently deductible as an ordinary and necessary business expense, or must be capitalized and subject to cost recovery. The issue of whether expenses should be deducted currently or capitalized has been central in many disputes between taxpayers and the IRS. In September 2013, Treasury issued final regulations (TD 9636, 9/19/13) addressing the tax treatment of materials, supplies, repairs, and improvements. These regulations replace Proposed and Temporary Regulations issued in 2011. The new regulations provide detailed guidance on when expenditures for materials, supplies, repairs, and maintenance may be deducted. The regulations also identify criteria for when amounts must be capitalized as improvements to property. This chapter focuses on the content and application of these regulations. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-1 Materials and Supplies Regulation Section 1.162-3 provides guidance on the deductibility of materials and supplies acquired for use in a trade or business. As a general rule, the costs of non-incidental materials and supplies are deductible in the tax year in which the materials and supplies are used or consumed. 1 Amounts paid to acquire or produce incidental materials and supplies, carried on hand and for which no record of consumption is kept or of which physical inventories at the beginning and end of the tax year are not taken, are deductible in the tax year in which paid. Materials and supplies are defined by Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(c) as tangible property used or consumed in the taxpayer·s operations that is not inventory and that x is a component acquired to maintain, repair, or improve a unit of tangible property (as determined under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-(e)) owned, leased, or serviced by the taxpayer and that is not acquired as part of any single unit of tangible property; consists of fuel, lubricants, water, and similar items reasonably expected to be consumed in 12 months or less, beginning when used in taxpayer·s operations; is a unit of property as determined under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e) that has an economic useful life of 12 months or less, beginning when the property is used or consumed in the taxpayer·s operations; is a unit of property as determined under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e) that has an acquisition or production cost of $200 or less (or other amount as identified in published guidance in the Federal Register or in the Internal Revenue Bulletin); is identified in published guidance in the Federal Register or in the Internal Revenue Bulletin as materials and supplies for which treatment is permitted under this rule; or meets the definition of rotable, temporary, or standby emergency spare parts. The treatment of spare parts is discussed in more detail in the following section. x x x x x The new regulations contain examples, some of which are reproduced in the following section with only minor editorial changes. Unless noted otherwise, the examples assume that the property is not an incidental material or supply. It is also assumed that the taxpayer uses a calendar year, the accrual method, and has not elected to capitalize or apply the de minimis rule. Example 2-1 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(h) Example 5 Consumable Property X operates a fleet of aircraft that carries freight for its customers. X has several storage tanks on its premises which hold jet fuel for its aircraft. Assume that once the jet fuel is placed in Xps aircraft, the jet fuel is reasonably expected to be consumed within 12 months or less. On December 31, Year 1, X purchases a two-year supply of jet fuel. In Year 2, X uses a portion of the jet fuel purchased on December 31, Year 1, to fuel the aircraft used in its business. The jet fuel that X purchased in Year 1 is a material or supply because it is reasonably expected to be consumed within 12 months or less from the time it is placed in Xps aircraft. X may deduct in Year 2 the amounts paid for the portion of jet fuel used in the operation of Xps aircraft in Year 2. 1 The guidance contains a reference that these provisions do not alter the treatment any other rule in the Internal Revenue Code. Reference is made to Sections 263A and 471 that have specific rules related to inventory. 2-2 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 2-2 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3)(h) Example 6 Unit of Property Costing $200 or Less X operates a business that rents out a variety of small individual items to customers (rental items). X maintains a supply of rental items on hand. In Year 1, X purchases a large quantity of rental items to use in its rental business. Assume that each rental item is a unit of property and costs $200 or less. In Year 2, X begins using all of the rental items purchased in Year 1 by providing them to customers of its rental business. X does not sell or exchange these items on established retail markets at any time after the items are used in the rental business. The rental items are materials and supplies, the amounts that X paid for the rental items in Year 1 are deductible in Year 2, the tax year in which the rental items are used in Xps business. Economic Useful Life The general rule of Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(c)(4) states that the economic useful life of a unit of property is not necessarily the useful life inherent in the property but is the period over which the property may reasonably be expected to be useful to the taxpayer, useful to the taxpayer·s trade or business, or useful for the production of income. 2 If the taxpayer has an applicable financial statement (as defined as follows), the economic useful life of a unit of property for this purpose is the useful life initially used by the taxpayer for purposes of determining depreciation in its applicable financial statement, regardless of salvage value. When a taxpayer does not have an applicable financial statement in the tax year in which a unit of property is originally acquired or produced, the economic useful life of the unit of property must be determined under the general rule for economic life described previously. If the taxpayer treats amounts paid for a unit of property as an expense in its applicable financial statement on a basis other than the useful life of the property or if a taxpayer does not depreciate the unit of property on its applicable financial statement, the economic useful life of the unit of property must also be determined using the preceding general rule.3 An applicable financial statement is the following statement with the highest priority. They are ordered in descending priorities. x x A financial statement required to be filed with the SEC (the 10-K or the Annual Statement to Shareholders); A certified audited financial statement that is accompanied by the report of an independent CPA (or in the case of a foreign entity, by the report of a similarly qualified independent professional), that is used for ² credit purposes; 2 The rules refer to Reg. Sec. 1.167(a)-1(b) for the factors to be considered in determining this period. The rules use as an example a taxpayer that has a policy of expensing on its applicable financial statement amounts paid for a unit of property costing less than a certain dollar amount (materiality threshold), notwithstanding that the unit of property has a useful life of more than one year. This case would require using the general rule for economic useful life. 3 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-3 x ² reporting to shareholders, partners, or similar persons; or ² any other substantial non-tax purpose; or A financial statement (other than a tax return) required to be provided to the federal or a state government or any federal or state agencies (other than the SEC or the IRS). Rotable, Temporary, and Standby Emergency Spare Parts The tax treatment of rotable and temporary spare parts has sparked controversy in recent years. The new final regulations under Section 162 provide four methods of dealing with rotable and temporary spare parts: (1) treating them as non-incidental materials and supplies; (2) using a new optional method of accounting for them; (3) electing to capitalize and depreciate them; or (4) deducting their cost currently under a de minimis safe harbor election. This section discusses each of these four methods. The final UHJXODWLRQVDOVRFUHDWHDQHZFDWHJRU\RIFRVWVFDOOHG´VWDQGE\HPHUJHQF\VSDUHSDUWVµ and permit three of the four methods just described to be applied to this category. Rotable spare parts are materials and supplies acquired for installation on a unit of property, removable from that unit of property, generally repaired or improved, and either reinstalled on the same or other property or stored for later installation. Temporary spare parts are materials and supplies used temporarily until a new or repaired part can be installed and then removed and stored for later (emergency or temporary) installation. See Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(c)(2). As defined in Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(c)(3), standby emergency spare parts are materials and supplies that are: x x x x x x x acquired when particular machinery or equipment is acquired (or later acquired and set aside for use in particular machinery or equipment) and directly related to that particular machinery or piece of equipment; set aside for use as replacements to avoid substantial operational time loss caused by emergencies due to particular machinery or equipment failure; located at or near the site of the installed related machinery or equipment to be readily available when needed; normally expensive, available only on special order, not readily available from a vendor or manufacturer, and not subject to normal periodic replacement; not interchangeable in other machines or equipment; not acquired in quantity (generally, only one is on hand for each piece of machinery or equipment); and not repaired and reused. General Rule for Rotable, Temporary and Standby Emergency Spare Parts As a general rule, rotable, temporary, and standby emergency spare parts are subject to the same tax treatment as non-incidental materials and supplies. Thus, they are treated as used or consumed in the tax year in which the taxpayer disposes of the parts, per Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(a)(3). Under this general rule, the cost of such spare parts would be deductible only in the year of disposition. 2-4 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 2-3 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(h) Example 2 Rotable Spare Parts Disposal Method X operates a fleet of specialized vehicles that it uses in its service business. Assume that each vehicle is a unit of property. At the time that it acquires a new type of vehicle, X also acquires a substantial number of rotable spare parts that it will keep on hand to quickly replace similar SDUWVLQ;ps vehicles as those parts break down or wear out. These rotable parts are removable from the vehicles and are repaired so that they can be reinstalled on the same or similar vehicles. X does not use the optional method of accounting for rotable and temporary spare parts. In Year 1, X acquires several vehicles and a number of rotable spare parts to be used as replacement parts in these vehicles. In Year 2, X repairs several vehicles by using these rotable spare parts to replace worn or damaged parts. In Year 3, X removes these rotable spare parts from its vehicles, repairs the parts, and reinstalls them on other similar vehicles. In Year 5, X can no longer use the rotable parts it acquired in Year 1 and disposes of them as scrap. The rotable spare parts acquired in Year 1 are materials and supplies. Rotable spare parts are generally used or consumed in the tax year in which the taxpayer disposes of the parts. So the amounts that X paid for the rotable spare parts in Year 1 are deductible in Year 5, the tax year in which X disposes of the parts. Optional Method of Accounting for Rotable and Temporary Spare Parts Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(e) allows taxpayers to adopt an optional method of accounting for rotable and temporary spare parts. This method does not apply to standby emergency spare parts. The optional method is considered a method of accounting under Section 446(a). A taxpayer that uses the optional method for rotable parts must use this method for all of the taxpayer·s pools of rotable and temporary spare parts used in the same trade or business and for which it uses this method for its books and records. If a taxpayer uses the optional method for pools of rotable or temporary spare parts for which it does not use the optional method for its book and records, then the taxpayer must use the optional method for all of its pools of rotable spare parts in the same trade or business. If used, the optional method must be applied to each rotable or temporary spare part (part) upon the taxpayer·s initial installation, removal, repair, maintenance or improvement, reinstallation, and disposal of each part. Under this method, the taxpayer must deduct the amount paid to acquire or produce the part in the tax year in which that part is first installed on a unit of property for use in the taxpayer·s operations, per Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(a)(2)(i). Related installation costs are also deductible. When the part is removed from a unit of property to which it was initially or subsequently installed, per Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(e)(2)(ii), the taxpayer must x x include in gross income the fair market value of the part and include in the basis of the part its fair market value and the amount paid to remove the part from the unit of property. The taxpayer is not permitted to currently deduct and must include in the basis of the part any amounts paid to maintain, repair, or improve the part in the tax year these amounts are paid. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-5 In the case of reinstallation, the taxpayer must deduct the amount to reinstall the part and those included in basis under the removal and repair points just described to the extent they have not been previously deducted under this reinstallation rule, per Reg. 1.162-3(e)2)(iv). A similar rule applies in the case of disposals (they are deducted to the extent not previously deducted). Election to Capitalize and Depreciate Rotable, Temporary and Standby Emergency Spare Parts Taxpayers may also elect to capitalize and depreciate the cost of rotable, temporary and standby emergency spare parts, per Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(d). The election generally applies to amounts paid during the tax year to acquire or produce any such parts. However, the election cannot be made if x the rotable, temporary, or standby emergency spare part is intended to be used as a component of a unit of property with an economic useful life of 12 months or less or costing $200 or less; or the rotable, temporary, or standby emergency spare part is intended to be used as a component of a property and the taxpayer cannot or has not elected to capitalize and depreciate that unit of property under this paragraph; or the part is a rotable or temporary spare part and the taxpayer has elected to use the optional method of accounting for rotable and temporary spare parts. x x Taxpayers make the election by capitalizing the relevant amounts in the tax year they are paid and properly depreciating them. The election must be made on a timely (including extensions) filed return. For pass-through entities the election is made at the entity and not at the owner level. The election can only be revoked through a letter ruling. The rules also state that an election may not be made or revoked through the filing of an application for change in accounting method or, before obtaining the commissioner·s consent to make the late election or to revoke the election, by filing an amended federal income tax return. Example 2-4 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(h) Example 13 Election to Capitalize and Depreciate X is in the mining business. X acquires certain temporary spare parts, which it keeps on hand to avoid operational time loss in the event it must make temporary repairs to a unit of property that is subject to depreciation. These parts are not used to improve property. These temporary spare parts are used until a new or repaired part can be installed and then are removed and stored for later temporary installation. X does not use the optional method of accounting for rotable and temporary spare parts. The temporary spare parts are materials and supplies and the amounts paid for the temporary spare parts are generally deductible in the taxable year in which they are disposed of by X. However, because it is unlikely that the temporary spare parts will be disposed of in the near future, X would prefer to treat the amounts paid for the spare parts as capital expenditures subject to depreciation. X may elect to treat the cost of each temporary spare part as a capital expenditure and as an asset subject to an allowance for depreciation. X makes this election by capitalizing the amounts paid for each spare part in the taxable year that X acquires the spare parts and by beginning to recover the costs of each part on its timely filed federal tax return for the taxable year in which the part is placed in service for purposes of determining depreciation under the applicable provisions of the Internal Revenue Code and the Treasury Regulations. 2-6 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited De Minimis Safe Harbor Rule A taxpayer making the de minimis safe harbor election under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-1(f) is permitted a current deduction for amounts paid for property costing less than a certain dollar amount or that have a useful life of not more than 12 months. In general, taxpayers making the election must apply it to all eligible materials and supplies, including eligible rotable, temporary, and standby emergency spare parts. However, the de minimis safe harbor election cannot be made for those rotable, temporary, or standby emergency spare parts of which the taxpayer elects the optional method of accounting or capitalization method described previously. Note: Effective for taxable years beginning on or after January 1, 2016, the IRS in Notice 2015-82 increased the de minimis safe harbor threshold from $500 to $2,500 per invoice or item for taxpayers without applicable financial statements. In addition, the IRS will provide audit protection to eligible businesses by not challenging the use of the $2,500 threshold for tax years ending before January 1, 2016, if the taxpayer otherwise satisfies the requirements of Treasury Regulation Section 1.263(a)-1(f)(1)(ii). Example 2-5 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(h) Example 14 Election to Apply de minimis Rule X provides consulting services to its customers. In Year 1, X pays amounts to purchase 50 laptop computers. Each laptop computer is a unit of property, costs $400, and has an economic useful life of more than 12 months. Also in Year 1, X purchases 50 office chairs to be used by its employees. Each office chair is a unit of property that costs $100. X has an applicable financial statement and a written accounting policy at the beginning of Year 1 to expense amounts paid for units of property costing $500 or less. X treats amounts paid for property costing $500 or less as an expense on its applicable financial statement in Year 1. The laptop computers are not materials or supplies. Therefore, the amounts X pays for the computers must generally be capitalized as amounts paid for the acquisition of tangible property. The office chairs are materials and supplies. Thus, the amounts paid for the office chairs are deductible in the taxable year in which they are first used in Xps business. However, if X properly elects to apply the de minimis safe harbor to amounts paid in Year 1, then X must apply the de minimis safe harbor to amounts paid for the computers and the office chairs, rather than treat the office chairs as the costs of materials and supplies. Under the de minimis safe harbor, X may deduct the amounts paid for the computers and the office chairs in the taxable year paid. KNOWLEDGE CHECK 1. The cost of nonincidental materials and supplies a. b. c. d. Must be capitalized and recovered through depreciation. Is deductible in the year in which paid. Is deductible in the year in which used or consumed. Must be capitalized to inventory and recovery through cost of goods sold. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-7 2. Costs of rotable spare parts a. b. c. d. Are generally not considered materials and supplies. Must be capitalized and depreciated. Are typically deductible upon acquisition. Are eligible for a new optional method of accounting. 3. Which material and supply costs are deductible in the current year? a. Non-incidental materials and supplies purchased during the year and on hand at year end. b. The cost of standby emergency spare parts with a useful life of greater than 12 months purchased during the year and on hand at year end, but not yet installed on a unit of property. c. The cost of incidental materials and supplies purchased during the year for which inventory records are not maintained. d. Costs of materials incorporated into inventory items produced during the current year. 2-8 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Repairs Versus Improvements Repairs, unlike improvements, do not add value to the underlying property or significantly lengthen its life. Repairs maintain property in efficient operating condition. Repairs are deductible as business expenses, while improvements must be capitalized and can generally be recovered through depreciation. Taxpayers and the IRS often disagree over whether a particular outlay is a repair or a capital improvement. New regulations attempt to provide clarity on the distinction between repairs and improvements. Reg. Sec. 1.162-4 addresses deductibility of amounts paid for repairs and maintenance. Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3 provides rules on identifying when costs result in an improvement of tangible property and must be capitalized. AMOUNTS PAID TO IMPROVE TANGIBLE PROPERTY Generally, taxpayers must capitalize the aggregate of related amounts paid to improve a unit of property owned by the taxpayer.4 A unit of property is considered improved for this purpose if the amounts paid for activities performed after the property is placed in service by the taxpayer either x x x result in a betterment to the unit of property; restore the unit of property; or adapt the unit of property to a new or different use.5 Unit of Property The concept of unit of property is very important to understanding the new rules. These unit of property rules as defined in Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e)(1) are only applicable to the following: Section 263(a) and Reg. Secs. 1.263(a)-1, 1.263(a)-2, 1.263(a)-3, and 1.162-3. The rules generally use a functional interdependence standard, but special rules apply for certain types of property. The rule also states that property that is aggregated or subject to a general asset account election or accounted for in a multiple asset account (pooled assets) may not be treated as a single unit of property. Buildings Except as otherwise provided in the rules, Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e)(2) provides that each building and its related structural components is a single unit of property. Despite this, the capitalization standards must be applied not to that unit of property but instead to the building structure and to each of the eight building systems listed. Thus, amounts are considered as paid for improvements to a building if it results in an improvement to the following: 4 The rule refers taxpayers to Section 263A for the costs required to be capitalized to property produced by the taxpayer or to property acquired for resale; Section 1016 for adding capitalized amounts to the basis of the unit of property; and Section 168 for the treatment of additions or improvements for depreciation purposes. Also, as was the case for other temporary regulations in this area, these rules to do not override other provisions (for example Section 263A) except for Sections 162(a) or 212. 5 The rule provides that the aggregate of related amounts paid to improve a unit of property may be incurred over a period of more than one tax year, and whether amounts are related to the same improvement is a facts and circumstances determination. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-9 x x Building structure³the building and its structural components other than the structural components designated as buildings systems. Building system³each of the following structural components including the components thereof constitutes a building system that is separate from the building structure, and to which the improvement rules must be applied: ² Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems (including motors, compressors, boilers, furnace, chillers, pipes, ducts, radiators). ² Plumbing systems (including pipes, drains, valves, sinks, bathtubs, toilets, water and sanitary sewer collection equipment, and site utility equipment used to distribute water and waste to and from the property line and between buildings and other permanent structures). ² Electrical systems (including wiring, outlets, junction boxes, lighting fixtures and associated connectors, and site utility equipment used to distribute electricity from property line to and between buildings and other permanent structures). ² All escalators. ² All elevators. ² Fire-protection and alarm systems (including sensing devices, computer controls, sprinkler heads, sprinkler mains, associated piping or plumbing, pumps, visual and audible alarms, alarm control panels, heat and smoke detection devices, fire escapes, fire doors, emergency exit lighting and signage, and firefighting equipment, such as extinguishers, hoses). ² Security systems for the protection of the building and its occupants (including window and door locks, security cameras, recorders, monitors, motion detectors, security lighting, alarm systems, entry and access systems, related junction boxes, associated wiring and conduit). ² Gas distribution system (including associated pipes and equipment used to distribute gas to and from property line and between buildings or permanent structures). ² Other structural components identified in published guidance in the Federal Register or in the Internal Revenue Bulletin. In the case of someone owning an individual unit of a condominium or similar type of multi-unit building, the unit of property is the individual unit owned by the taxpayer and the structural components that are part of the unit. Condominium improvements again consist of improvements to the building structure or building system. Building management associations must also apply the appropriate rules to the building structure or building system.6 In the case of a leased building, the unit of property is each building and its structural components if the whole building is leased, or the portion of each building subject to the lease and the structural components associated with the leased portion, per Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e)(2)(v). Property Other Than Buildings For property other than buildings, generally the components that are functionally interdependent will constitute a single unit of property. This functional interdependence means that placing one component in service is dependent on placing the other component in service, per Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e)(3)(i). Plant property is defined as functionally interdependent machinery or equipment, other than network assets, used to perform an industrial process, such as manufacturing, generation, warehousing, distribution, automated materials handling in service industries, or other similar activities. For plant property, the general rule unit is divided into smaller units which consist of each component (or group of 6 Similar rules apply to cooperatives with the unit of property based on the portion to which the owner has possessory rights and the related structural components. 2-10 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited components) that performs a discrete and major function or operation within the functionally interdependent equipment. Network assets are defined as railroad track, oil and gas pipelines, water and sewage pipelines, power transmission and distribution lines, and telephone and cable lines that are owned or leased by taxpayers in each of those respective industries. The rules provide as examples: trunk and feeder lines, pole lines, and buried conduit, but does not include building structures or systems or property that is adjacent to the network asset but not part of that network asset such as a bridge or tunnel. For network assets, the unit of property is based on the facts and circumstances (unless provided otherwise in official published guidance by the IRS). The functional interdependence standard is not determinative in the area of network assets. For leased property other than buildings, the general rules just described apply, but note that the unit of property cannot be larger than the unit of leased property. Additional Rules The rules provide that a component (or a group of components) of a unit property must be treated as a separate unit of property if, when initially placed in service, the taxpayer has properly treated the component as being within a different class of property under Section 168(e) (Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) classes) than the class of the unit of property of which the component is a part, or the taxpayer has properly depreciated the component using a different depreciation method than the depreciation method of the unit of property of which the component is a part. If the taxpayer or the IRS changes the treatment of property (or part of it) to a proper MACRS class or method, then the taxpayer must change the unit of property determination for that property (or part) to be consistent with the change in treatment for depreciation purposes. 7 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(g) provides that taxpayers are required to capitalize all of the direct costs of an improvement and all of the indirect costs (including, for example, otherwise deductible repair or component removal costs) that directly benefit or are incurred by reason of an improvement per the Section 263A guidance. The rule provides, therefore, that those indirect costs that do not directly benefit and are not incurred by reason of an improvement are not required to be capitalized under Section 263(a), regardless of whether they are made at the same time as an improvement. The rules provide an exception for individuals· residences under which an individual taxpayer is allowed to capitalize amounts paid for repairs and maintenance that are made at the same time as capital improvements to units of property not used in the taxpayer·s trade or business or for the production of income if the amounts are paid as part of a remodeling of the taxpayer·s residence. 7 The rule uses as an example a cost segregation study or a change in the use of the property. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-11 Example 2-6 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e)(6) Example 1 Building Systems X owns an office building that contains a HVAC system. The HVAC system incorporates ten roof-mounted units that service different parts of the building. The roof-mounted units are not connected and have separate controls and duct work that distribute the heated or cooled air to different spaces in the buildingps interior. X pays an amount for labor and materials for work performed on the roof-mounted units. X must treat the building and its structural components as a single unit of property. An amount is paid for an improvement to a building if it results in an improvement to the building structure or any designated building system. The entire HVAC system, including all of the roof-mounted units and their components, comprise a building system. Therefore, if an amount paid by X for work on the roof-mounted units results in an improvement (for example, a betterment) to the HVAC system, X must treat this amount as an improvement to the building. Example 2-7 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e)(6) Example 6 Plant PropertytDiscrete and Major Function X is engaged in a uniform and linen rental business. X owns and operates a plant that uses many different machines and equipment in an assembly line-like process to treat, launder, and prepare rental items for its customers. X uses two laundering lines in its plant, each of which can operate independently. One line is used for uniforms and another line is used for linens. Both lines incorporate several sorters, boilers, washers, dryers, ironers, folders, and waste water treatment systems. Because the laundering equipment contained within the plant is property other than a building, the unit of property for the laundering equipment is initially determined under the general rule of functional interdependence. Under this rule, the initial units of property are each laundering line because each line is functionally independent and is comprised of components that are functionally interdependent. However, because each line is comprised of plant property, X must further divide these initial units of property into smaller units of property by determining the components (or groups of components) that perform discrete and major functions within the line. So, X must treat each sorter, boiler, washer, dryer, ironer, folder, and waste water treatment system in each line as a separate unit of property because each of these components performs a discrete and major function within the line. 2-12 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 2-8 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e)(6) Example 16 Personal Property Application of Additional Rules X is engaged in the business of transporting freight throughout the US. To conduct its business, X owns a fleet of truck tractors and trailers. Each tractor and trailer is comprised of various components, including tires. X purchased a truck tractor with all of its components, including tires. The tractor tires have an average useful life to X of more than one year. At the time X placed the tractor in service, it treated the tractor tires as a separate asset for depreciation purposes (per Section 168). X properly treated the tractor (excluding the cost of the tires) as three-year property and the tractor tires as five-\HDUSURSHUW\%HFDXVH;pVWUDFWRULVSURSHUW\RWKHUWKDQDEXLOGLQJ the initial units of property for the tractor are determined under the general rule of functional interdependence. This would indicate that X must treat the tractor, including its tires, as a single unit of property because the tractor and the tires are functionally interdependent (that is, the placing in service of the tires is dependent upon the placing in service of the tractor). However, X must treat the tractor and tires as separate units of property because X properly treated the tires as being within a different class of property under Section 168(e). Improvements to Leased Property For a leased building, the lessor applies the improvement and unit of property rules to amounts paid to improve the building and its systems. The lessee applies the improvement and unit of property rules to the portions of the building and its structural components subject to the lease. A lessee is required to capitalize the aggregate of related amounts that it pays to improve a unit of leased property except to the extent that Section 110 applies to a construction allowance received by the lessee for the purpose of such improvement or where the improvement constitutes a substitute for rent. 8 The lessee is also required to capitalize the aggregate of related amounts that a lessor pays to improve a unit of leased property if the lessee is the owner of the improvement (again except to the extent that Section 110 applies). Amounts paid for lessee improvements are treated as amounts paid to acquire or produce a unit of real or personal property and are thus capitalized under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-2(d)(1). An amount capitalized as a lessee improvement is a unit of property separate from the leased property being improved. However, an amount that a lessee pays to improve a lessee improvement is not a unit of property separate from such lessee improvement. Similarly, a lessor is required to capitalize the aggregate of related amounts that it pays directly, or indirectly, through a construction allowance to the lessee, to improve a unit of leased property where the lessor is the owner of the improvement or to the extent that Section 110 applies to the construction allowance. 8 Section 110 contains the general rule that gross income of a lessee does not include any amount received in cash (or treated as a rent reduction) by a lessee from a lessor that is under a short-term lease of retail space, and is for the SXUSRVHRIVXFKOHVVHH·VFRQVWUXFWLQJRULPSURYLQJTXDOLILHGORQJ-term real property for use in sXFKOHVVHH·VWUDGHRU business at such retail space, but only to the extent that such amount does not exceed the amount expended by the lessee for such construction or improvement. The rule refers to Reg. Sec. 1.61-8(c) for the treatment of lessee expenditures that constitute a substitute for rent Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-13 A lessor is also required to capitalize the aggregate of related amounts that the lessee pays to improve a unit of property in which the lessee·s improvement constitutes a substitute for rent. If an amount is capitalized by the lessor, it is not to be capitalized by the lessee. Amounts capitalized as lessor improvements are not a unit of property separate from the unit of property improved. Example 2-9 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(f)(4) Example 1 Lessee ImprovementstAdditions to Building T is a retailer of consumer products. In Year 1, T leases a building from L, which T intends to use as a retail sales facility. The leased building consists of the building structure and various building systems, including a plumbing system, an electrical system, and an HVAC system. Under the terms of the lease, T is permitted to improve the building at its own expense. Because T leases the entire building, T must treat the leased building and its structural components as a single unit of property. An amount is paid for an improvement to the entire leased building if it results in an improvement to the leased building structure or to any building system within the leased building. So, if T pays an amount that improves the building structure, the plumbing system, the electrical system, or the HVAC system, then T must treat this amount as an improvement to the entire leased building. In Year 2, T pays an amount to construct an extension to the building to be used for additional warehouse space. Assume that this amount results in a betterment to Tps leased building structure and does not affect any building systems. Accordingly, the amount that T pays for the building extension results in an improvement to the leased building structure, and thus, is treated as an improvement to the entire leased building. Because T, the lessee, paid an amount to improve a unit of leased property, T is required to capitalize the amount paid for the building extension as a leasehold improvement. In addition, T must treat the amount paid for the improvement as the acquisition or production of a unit of property. In Year 5, T pays an amount to add a large overhead door to the building extension that it constructed in Year 2 to accommodate the loading of larger products into the warehouse space. To determine whether the amount paid by T is for a leasehold improvement, the unit of property and the improvement rules are applied and include Tps previous improvements to the leased property. Therefore, the unit of property is the entire leased building, including the extension built in Year 2. In addition, the leased building property is improved if the amount is paid for an improvement to the building structure or any building system. Assume that the amount paid to add the overhead door is for a betterment to the building structure, which includes the extension. Accordingly, T must capitalize the amounts paid to add the overhead door as a leasehold improvement to the leased building property. In addition, T must treat the amount paid for the improvement as the acquisition or production of a unit of property (leasehold improvement property). However, to determine whether a future amount paid by T is for a leasehold improvement to the leased building, the unit of property and the improvement rules are again applied and include the new overhead door. Note: The rules states that for this purpose, a federal, state, or local regulator·s requirement that a taxpayer make certain repairs or maintenance on a unit of property to continue operating the property is not relevant in determining whether the amount paid improves the unit of property. 2-14 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Routine Maintenance Safe Harbor Amounts paid for routine maintenance performed on a unit of property, including a building, its structural components and its systems, are generally not improvements to that unit of property. Costs qualifying under the routine maintenance safe harbor should be currently deductible as ordinary and necessary business expenses. The definition of routine maintenance differs slightly for building property versus non-building assets. Requirements under the safe harbor are found in Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(i). Routine Maintenance of Buildings Routine maintenance for a building unit of property is the recurring activities a taxpayer expects to perform to keep the building structure or each building system in its ordinarily efficient operating condition. Routine maintenance activities include, for example, inspection, cleaning, and testing of the building structure or each building system. Routine maintenance also includes the replacement of damaged or worn parts with comparable and commercially available replacement parts. Maintenance activities are routine only if the taxpayer reasonably expects to perform such activities more than once during the 10-year period beginning when the building structure or system on which the routine maintenance is performed is placed in service by the taxpayer. A taxpayer·s expectation will not be deemed unreasonable merely because it does not actually perform the maintenance a second time during the 10-year period, as long as the taxpayer can substantiate that its expectation was reasonable at the time the property was placed in service. In making this determination, relevant factors include the recurring nature of the activity, industry practice, manufacturer·s recommendations, and the taxpayer·s experience with similar property. Routine Maintenance of Non-Buildings Routine maintenance on units of property other than building units is the recurring activities that a taxpayer expects to perform as a result of the taxpayer·s use of the unit of property to keep the unit of property in its ordinarily efficient operating condition. Examples of routine maintenance provided are inspection, cleaning, and testing, and the replacement of parts of the unit of property with comparable and commercially available and reasonable replacement parts. To be considered routine, at the time the unit of property is placed in service, the taxpayer must have reasonably expected to perform the activities more than once during the unit·s class life.9 Examples of factors for routine maintenance include the recurring nature of the activity, industry practice, manufacturers· recommendations, and the taxpayer·s experience with similar property. In the case of a lessor, use includes the use by a lessee of the property. Except as provided as follows, amounts paid for routine maintenance include routine maintenance for rotable and temporary spare parts. 10 Additional Issues The following items are not included in the definition of routine maintenance: x x Amounts considered a betterment under the rules discussed as follows. Amounts paid for the replacement of a component of a unit of property and the taxpayer has properly deducted a loss for that component (other than a casualty loss under Reg. Sec. 1.165-7). 9 Class life for this purpose is defined as the recovery period under the alternative depreciation system of Sections 168(g)(2) and (3). This is the case regardless of whether the property is depreciated under Section 168(g). If the unit of property consists of components with different class lives, use the life of the component with the longest class life. 10 The rule also refers readers to Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(a)(3), providing generally that rotable and temporary spare parts are used or consumed by the taxpayer in the tax year in which the taxpayer disposes of the parts. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-15 x x x x x x Amounts paid for the replacement of a component of a unit of property and the taxpayer has properly taken into account the adjusted basis of the component in realizing gain or loss resulting from the sale or exchange of the component. Amounts paid for the repair of damage to a unit of property for which the taxpayer has taken a basis adjustment as a result of a casualty loss under Section 165, or relating to a casualty event described in Section 165. Amounts paid to return a unit of property to its ordinarily efficient operating condition, if the property has deteriorated to a state of disrepair and is no longer functional for its intended use under the rules discussed as follows. Amounts paid to adapt a unit of property to a new or different use under the rules discussed as follows. Amounts paid for repairs, maintenance, or improvement of network assets. Amounts paid for repairs, maintenance, or improvement of rotable and temporary spare parts to which the taxpayer applies the optional method of accounting for rotable and temporary spare parts per Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(e). Example 2-10 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(i)(6) Example 1 Routine Maintenance on Component X is a commercial airline engaged in the business of transporting passengers and freight throughout the US and abroad. To conduct its business, X owns or leases various types of aircraft. As a condition of maintaining its airworthiness certification for these aircraft, X is required by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to establish and adhere to a continuous maintenance program for each aircraft within its fleet. These programs, which are designed by X and the aircraftps manufacturer and approved by the FAA, are incorporated into each aircraftps maintenance manual. The maintenance manuals require a variety of periodic maintenance visits at various intervals. One type of maintenance visit is an engine shop visit (ESV), which X expects to perform on its aircraft engines approximately every four years in order to keep its aircraft in its ordinarily efficient operating condition. In Year 1, X purchased a new aircraft, which included four new engines attached to the airframe. The four aircraft engines acquired with the aircraft are not materials or supplies because they are acquired as part of a single unit of property, the aircraft. In Year 5, X performs its first ESV on the aircraft engines. The ESV includes disassembly, cleaning, inspection, repair, replacement, reassembly, and testing of the engine and its component parts. During the ESV, the engine is removed from the aircraft and shipped to an outside vendor who performs the ESV. If inspection or testing discloses a discrepancy in a partps conformity to the specifications in Xps maintenance program, the part is repaired, or if necessary, replaced with a comparable and commercially available and reasonable replacement part. After the ESVs, the engines are returned to X to be reinstalled on another aircraft or stored for later installation. Assume that the unit of property for Xps aircraft is the entire aircraft, including the aircraft engines, and that the class life for Xps aircraft is 12 years. Assume that none of the preceding five bulleted exceptions applies to the costs of performing the ESVs. 2-16 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 2-10 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(i)(6) Example 1 (continued) Because the ESVs involve the recurring activities that X expects to perform as a result of its use of the aircraft to keep the aircraft in ordinarily efficient operating condition, and consist of maintenance activities that X expects to perform more than once during the 12 year class life of the aircraft, Xps ESVs are within the routine maintenance safe harbor. Accordingly, the amounts paid for the ESVs are deemed not to improve the aircraft and are not required to be capitalized.11 Example 2-11 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(i)(6) Example 7 Routine Maintenance t Not Meeting Safe Harbor X is a Class I railroad that owns a fleet of freight cars. Assume that a freight car, including all its components, is a unit of property and has a class life of 14 years. At the time that X places a freight car into service, X expects to perform cyclical reconditioning to the car every 8 to 10 years in order to keep the freight car in ordinarily efficient operating condition. During this reconditioning, X pays amounts to disassemble, inspect, and recondition or replace components of the freight car with comparable and commercially available and reasonable replacement parts. Ten years after X places the freight car in service, X pays amounts to perform a cyclical reconditioning on the car. Because X expects to perform the reconditioning only once during the 14-year class life of the freight car, the amounts X pays for the reconditioning do not qualify for the routine maintenance safe harbor. Accordingly, X must capitalize the amounts paid for the reconditioning of the freight car if these amounts result in an improvement. Building Safe Harbor for Small Taxpayers The final regulations under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(h) add a new safe harbor permitting qualifying small taxpayers to elect to deduct rather than capitalize improvements made to eligible building property. For this purpose, a qualifying taxpayer is one with $10 million or less average annual gross receipts in the three preceding tax years. An eligible building property is a building unit with an unadjusted basis of $1 million or less. The safe harbor election applies only if the total amount paid during the tax year for repairs, maintenance, improvements, and similar activities performed on the eligible building does not exceed the lesser of $10,000 or 2 percent of the building·s unadjusted basis. To determine the total paid, amounts deducted under the de minimis safe harbor of Reg. Sec. 263(a)-1(f) and the building routine maintenance safe harbor discussed previously must be included. If the total amounts paid exceed the per-building threshold, the small taxpayer building safe harbor doesn·t apply to any amounts spent during the tax year. 11 In example 2, the ESV is performed in Year 15, which is beyond the 12-year life, but the amount is still not an improvement because it is the same routine maintenance activity and it meets the routine maintenance safe harbor. In example 3 four additional engines are rotable spare parts because they are acquired separately and are repaired and reinstalled. Here the asset also has a 12-year life, and the ESV on these engines also meets the safe harbor. Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(a) addresses the amounts initially paid for these engines. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-17 The small taxpayer building safe harbor is elected annually on a building-by-building basis by including a statement on the taxpayer·s timely filed original federal tax return, including extensions, for the year the costs are incurred. An election to apply the safe harbor cannot be revoked. The safe harbor applies to amounts paid in tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2013. However, a taxpayer may choose to apply the safe harbor to amounts paid in tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2012. Example 2-12 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-(h)(10) Example 1 Safe Harbor Applicable A is a qualifying small taxpayer. A owns an office building in which A provides consulting services. In Year 1, Aps building has an unadjusted basis of $750,000. In Year 1, A pays $5,500 for repairs, maintenance, improvements, and similar activities to the office building. Because Aps building unit of property has an unadjusted basis of $1,000,000 or less, Aps building constitutes eligible building property. The aggregate amount paid by A during Year 1 for repairs, maintenance, improvements, and similar activities on this eligible building property does not exceed the lesser of $15,000 (2 percent of the buildingps unadjusted basis of $750,000) or $10,000. Therefore, A may elect not to capitalize the amounts paid for repair, maintenance, improvements, or similar activities on the office building in Year 1. If A properly makes the election under paragraph (h)(6) of this section for the office building and the amounts otherwise constitute deductible ordinary and necessary expenses incurred in carrying on a trade or business, A may deduct these amounts in Year 1. Capitalization of Betterments Betterment of a unit of property must be capitalized, under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(j). An amount results in the betterment of a unit of property only if it: x x x ameliorates a material condition or defect that either existed prior to the taxpayer·s acquisition of the unit of property or arose during the production of the unit of property, whether or not the taxpayer was aware of the condition or defect at the time of acquisition or production; results in a material addition (including a physical enlargement, expansion, extension or addition of a major component) to the unit of property or a material increase in the capacity of the unit of property; or is reasonably expected to materially increase the productivity, efficiency, strength, quality, or output of the unit of property. In the case of a building, a betterment results if there is a betterment to the following properties: improvements to buildings (structure and system as defined previously); condominiums; cooperatives; and leased buildings. Whether a betterment exists involves examining the facts and circumstances, which include the purpose of the expenditure, the physical nature of the work performed, and the effect of the expenditure on the unit of property. Note: The rules provide that where a replacement with the same type of part (for example, because of technological advancements or product enhancements) is not practicable, the replacement of the part with an improved, but comparable, part does not, by itself, result in a betterment to the unit of property. 2-18 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited If there is a specific cause for an expenditure, comparing the condition before and after the event is used to determine if there was a betterment. When correcting for normal wear and tear, the before test is based on the condition of the unit after the last time the taxpayer corrected the unit for wear and tear. Example 2-13 Reg. Sec. 1.263-3(j)(3) Example 1 Amelioration of Pre-existing Defect In Year 1, X purchases a store located on a parcel of land that contained underground gasoline storage tanks left by prior occupants. Assume that the parcel of land is the unit of property. The tanks had leaked, causing soil contamination. X is not aware of the contamination at the time of purchase. In Year 2, X discovers the contamination and incurs costs to remediate the soil. The remediation costs result in a betterment to the land because X incurred the costs to ameliorate a material condition or defect that existed prior to Xps acquisition of the land. Example 2-14 Reg. Sec. 1.263-3(j)(3) Example 6 Building RefreshtNot a Betterment X owns a nationwide chain of retail stores that sell a wide variety of items. To remain competitive in the industry and increase customer traffic and sales volume, X periodically refreshes the appearance and layout of its stores. The work that X performs to refresh a store consists of cosmetic and layout changes to the storeps interiors and general repairs and maintenance to the store building to make the stores more attractive and the merchandise more accessible to customers. The work to each store building consists of replacing and reconfiguring a small number of display tables and racks to provide better exposure of the merchandise, making corresponding lighting relocations and flooring repairs, moving one wall to accommodate the reconfiguration of tables and racks, patching holes in walls, repainting the interior structure with a new color scheme to coordinate with new signage, replacing damaged ceiling tiles, cleaning and repairing vinyl flooring throughout the store building, and power washing building exteriors. The display tables and the racks all constitute Section 1245 property. X pays amounts to refresh 50 stores during the taxable year. In its applicable financial statement, X capitalizes all the costs to refresh the store buildings and amortizes them over a five-year period. Assume that each Section 1245 property within each store is a separate unit of property. Finally, assume that the work does not ameliorate any material conditions or defects that existed when X acquired the store buildings or result in any material additions to the store buildings. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-19 Example 2-14 Reg. Sec. 1.263-3(j)(3) Example 6 (continued) An amount is paid to improve a building unit of property if the amount is paid for a betterment to the building structure or any building system. Considering the facts and circumstances including the purpose of the expenditure, the physical nature of the work performed, and the effect of the expenditure on the buildingsp structures and systems, the amounts paid for the refresh of each building are not for any material additions to, or material increases in the capacity of, the buildingsp structures or systems as compared with the condition of the structures or systems after the previous refresh. Moreover, the amounts paid are not reasonably expected to materially increase the productivity, efficiency, strength, quality, or output of any building structure or system as compared to the condition of the structures or systems after the previous refresh. Rather, the work performed keeps Xps store buildingsp structures and buildingsp systems in their ordinarily efficient operating condition. Therefore, X is not required to treat the amounts paid for the refresh of its store buildingsp structures and buildingsp systems as betterments. However, X is required to capitalize the amounts paid to acquire and install each Section 1245 property. Capitalization of Restorations Generally, costs to restore a unit of property must be capitalized under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(k). Restoration includes amounts paid in making good the exhaustion for which an allowance is or has been made. Amounts are paid to restore a unit of property only if these amounts: x x x x x x are for the replacement of a component of a unit of property and the taxpayer has properly deducted a loss for that component (other than a casualty loss under Reg. Sec. 1.165-7); are for the replacement of a component of a unit of property and the taxpayer has properly taken into account the adjusted basis of the component in realizing gain or loss resulting from the sale or exchange of the component; are for the repair of damage to a unit of property for which the taxpayer has properly taken a basis adjustment as a result of a casualty loss under Section 165, or relating to a casualty event per Section 165; return the unit of property to its ordinarily efficient operating condition if the property has deteriorated to a state of disrepair and is no longer functional for its intended use; result in the rebuilding of the unit of property to a like-new condition after the end of its class life; or are for the replacement of a part or a combination of parts that comprise a major component or a substantial structural part of a unit of property. In the case of a building, the amount restores the unit if it restores improvements to buildings (structure and system as defined previously); condominiums; cooperatives; and leased buildings. The rules provide that a unit of property is rebuilt to a like-new condition if it is brought to the status of new, rebuilt, remanufactured, or similar status under the terms of any federal regulatory guideline or the manufacturer·s original specifications. The determination of whether the amount is for the replacement of a part or a combination of parts that comprise a major component or a substantial structural part of the unit of property involves 2-20 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited consideration of the facts and circumstances, including the quantitative or qualitative significance of the part or combination of parts in relation to the unit of property. 12 Example 2-15 Reg. Sec. 1.263-3(k)(7) Example 1 Replacement of Loss ComponenttCapitalization X owns a manufacturing building containing various types of manufacturing equipment. X does a cost segregation study of the manufacturing building and properly determines that a walk-in freezer in the manufacturing building is Section 1245. The freezer is not part of the building structure or the HVAC system, which is a separate building system. Several components of the walk-in freezer cease to function and X decides to replace them. X abandons the old freezer components and properly recognizes a loss from the abandonment of the components. X replaces the abandoned freezer components with new components and incurs costs to acquire and install the new components. X must capitalize the amounts paid to acquire and install the new freezer components because X replaced components for which it had properly deducted a loss. Example 2-16 Reg. Sec. 1.263-3(k)(7) Example 14 Replacement of Major ComponenttRoof K owns a manufacturing building. K discovers several leaks in the roof of the building and hires a contractor to inspect and fix the roof. The contractor discovers that a major portion of the decking has rotted and recommends the replacement of the entire roof. K pays the contractor to replace the entire roof, including the decking, insulation, asphalt, and various coatings. An amount is paid to improve a building if the amount is paid to restore the building structure or any building system. The roof is part of the building structure. Because the entire roof performs a discrete and critical function in the building structure, the roof comprises a major component of the building structure. In addition, because the roof comprises a large portion of the physical structure of the building structure, the roof comprises a substantial structural part of the building structure. Therefore, under either analysis, K must treat the amount paid to replace the roof as a restoration of the building and must capitalize the amount paid as an improvement. CapitalizationtAdapting Property to a New or Different Use Generally, amounts paid to adapt a unit of property to a new or different use must be capitalized under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(l). Adapting for this purpose means that the adaptation is not consistent with the taxpayer·s intended ordinary use of the unit of property at the time it was originally placed in service. 12 The rule states that a major component or substantial structural part includes a part or combination of parts that represents a large part of the physical unit of property. They could also be a part or combination that perform a discrete and critical function of the unit. An incidental component of the unit of property generally will not, by itself, constitute a major component, even though such component performs a discrete and critical function (Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(k)(6)(i)(A)). Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-21 In the case of buildings, the amounts adapt the unit if they adapt any of the following: improvements to buildings (structure and system as defined previously); condominiums; cooperatives; and leased buildings. Example 2-17 Reg. Sec. 1.263-3(k)(7) Example 1 New or Different Use X is a manufacturer and owns a manufacturing building that it has used for manufacturing since Year 1, when X placed it in service. In Year 30, X pays an amount to convert its manufacturing building into a showroom for its business. To convert the facility, X removes and replaces various structural components to provide a better layout for the showroom and its offices. X also repaints the building interiors as part of the conversion. When building materials are removed and replaced, X uses comparable and commercially available replacement materials. An amount is paid to improve Xps manufacturing building if the amount adapts the building structure or any designated building system to a new or different use. The amount paid to convert the manufacturing building into a showroom adapts the building structure to a new or different use because the conversion to a showroom is not consistent with Xps ordinary use of the building structure at the time it was placed in service. Therefore, X must capitalize the amount paid to convert the building into a showroom as an improvement to the building. Optional Regulatory Accounting Method The rules in Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(m) allow for an optional simplified method, which is called the regulatory accounting method, for regulated taxpayers. This method can be used to determine whether amounts paid to repair, maintain, or improve tangible property are to be treated as deductible expenses or capital expenditures. If a taxpayer uses the regulatory accounting method, then the rule states that the taxpayer must use that method for property subject to regulatory accounting instead of determining whether amounts paid to repair, maintain, or improve property are capital expenditures or deductible expenses under the general principles of Sections 162(a), 212, and 263(a).13 To be eligible, the taxpayer will be engaged in a trade or business in a regulated industry and subject to the accounting rules of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), or the Surface Transportation Board (STB). Under this method, the taxpayer follows its method of accounting for regulatory accounting purposes in determining whether an amount paid improves property. Therefore, a taxpayer capitalizes for federal income tax purposes amounts paid that are capitalized as an improvement for regulatory accounting purposes. If an improvement is not capitalized for regulatory purposes, then it is not capitalized for federal income tax under this method. If this method is used it must be used for all tangible property 13 The rule provides that the general capitalization rules and the routine maintenance safe harbor do not apply to amounts paid to repair, maintain, or improve property subject to regulatory accounting for taxpayers using this optional method.. 2-22 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited subject to regulatory accounting rules. It does not apply to such tangible property if it is not subject to the regulatory rules.14 Election to Capitalize Repairs and Maintenance Costs Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(n) permits taxpayers to elect to capitalize as an improvement and depreciate otherwise deductible repairs and maintenance costs. To qualify, expenses must be incurred in a trade or business and the taxpayer must treat the amounts as capital expenditures on its books and records. A taxpayer electing this treatment must apply the election to all repairs and maintenance of tangible property treated as capital expenditures on its books and records for the tax year of the election. The election is made by attaching a statement to the taxpayer·s timely filed (including extensions) original federal tax return for the year in which the improvement is placed in service. The election cannot be revoked. Other Issues Cost recovery of amounts capitalized is determined under the relevant provision of the tax law; that is, depending on use, sale, or disposition, it may occur through depreciation, cost of goods sold, and the like. Prior to the final regulations under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3, taxpayers were typically advised that repairs should not be undertaken at the same time as a general plan of improvement. The IRS had required capitalization of amounts expended under a general plan to rehabilitate railroad freight cars where their value was materially increased and their useful life was appreciably prolonged. A portion of the amounts expended, standing alone rather than as part of a general plan of rehabilitation, would have been deductible incidental repairs (Revenue Ruling 88-57, 1988-2 CB 36). Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(g)(1)(i) clarifies that indirect costs arising from activities that do not directly benefit and are not incurred by reason of an improvement are not required to be capitalized under Section 263(a), regardless of whether the activities are performed at the same time as an improvement. However, a taxpayer must capitalize all of the indirect costs (including, for example, otherwise deductible repair costs) that directly benefit or are incurred by reason of an improvement. In general, these rules apply to tax years that begin on or after January 1, 2014. The building safe harbor for small taxpayers, the optional regulatory accounting method, and the election to capitalize repairs and maintenance apply to costs incurred in tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2014. Except for the building safe harbor for small taxpayers, the optional regulatory accounting method, and the election to capitalize repairs and maintenance, a taxpayer may choose to apply these rules to tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2012. A taxpayer may choose to apply the building safe harbor for small taxpayers, the optional regulatory accounting method, and the election to capitalize repairs and maintenance to amounts paid in taxable years beginning on or after January 1, 2012. 14 The rule states that this method also does not apply to property for the tax years in which the taxpayer elected to apply the repair allowance per Reg. Sec. 1.167(a)-11(d)(2). Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-23 KNOWLEDGE CHECK 4. For purposes of the unit of property rules, building systems a. Are treated as if they were part of the same unit of property as the building structure. b. May include multiple units of property (for example, each air conditioning unit in an HVAC system is a separate unit of property). c. Include fire-protection and alarm systems, and security systems. d. Do not include elevators and escalators, which are considered part of the building structure. 5. The routine maintenance safe harbor a. Permits a current deduction for qualifying expenses. b. Does not apply to replacement of damaged or worn parts. c. With respect to buildings, requires that the taxpayer reasonably expect to perform the related DFWLYLWLHVPRUHWKDQRQFHGXULQJWKHSURSHUW\·VFODVVOLIH d. Is only available to small taxpayers. 6. Expenditures incurred to adapt property to a new or different use are a. b. c. d. Considered betterments. Deductible as repairs. Deductible as maintenance costs. Capitalized as improvements. 7. The new regulations on improvements to tangible property a. b. c. d. 2-24 Generally apply to costs incurred after January 1, 2012. Generally apply to tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2012. Generally apply to tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2014. Generally apply to costs incurred on or after January 1, 2014. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Accounting Methods Changes Changes to comply with the rules of Reg. Sec. 1.162-3 and Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3 are considered a change in method of accounting and Sections 446 and 481 will apply. Revenue Procedure 2014-16, 2014-9 IRB 606, as modified by Rev. Proc. 2014-54, 2014-41 IRB and Rev. Proc. 2015-14, 2015-5 IRB, provides procedures whereby taxpayers may obtain automatic consent to change to the methods described in Reg. Sec. 1.162-3 and Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3. AUTOMATIC CHANGE PROCEDURES UNDER REV. PROC. 2014-16 Rev. Proc. 2014-16 provides automatic accounting methods change procedures for taxpayers seeking to change to new methods required or desired in order to comply with the tangible property regulations. In order to use these automatic change procedures, the taxpayer generally must comply with the final regulations starting with his or her 2014 tax year (first tax year beginning after December 31, 2013). These procedures apply to potential methods changes for the following topics previously discussed in this chapter: x x x x x x x Deducting repairs and maintenance costs that have been capitalized in the past, capitalizing improvements that have been deducted as repairs and maintenance in the past, and changes in identifying the unit of property to which such rules apply. Adopting available routine maintenance safe harbor methods. Changing to the optional regulatory accounting method for determining whether expenditures repair, maintain, or improve tangible property. Deducting non-incidental materials and supplies when used or consumed. Deducting incidental materials and supplies when paid or incurred. Deducting non-incidental rotable and temporary spare parts when disposed of. Changing to the optional method for rotable and temporary spare parts. A taxpayer seeking more than one method change within the scope of Rev. Proc. 2014-16 may file a single Form 3115. The signed original of the form is filed with the taxpayer·s federal income tax return for the year of the change. In addition, a copy of the signed Form 3115 must be filed with the IRS service center in Ogden, Utah, in lieu of filing the IRS National Office copy typically required for other automatic changes. Rev. Proc. 2014-16 provides designated automatic accounting method change numbers for all applicable changes. These numbers must be entered on the appropriate line on Form 3115 for all changes sought by the taxpayer. In addition, the taxpayer must indicate on Form 3115 the relevant paragraph of the tangible property regulations providing the method to which the taxpayer is changing. Additional detailed information requirements apply if a taxpayer is changing a unit of property, or the identification of a building structure or system. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-25 Table 2-1 Rev. Proc. 2014-16 Common Changes Under Final Tangible Property Regulations, Related Designated Automatic Accounting Method Change Numbers (DCNs) and Citations Description of Change DCN Citation A change to deducting amounts for repairs and maintenance or a change to capitalizing amounts for improvements 184 Reg. Secs. 1.162-4, 1.263(a)-3 Change to deducting non-incidental materials and supplies when used or consumed 186 Reg. Secs. 1.162-3(a)(1), (c)(1) Change to deducting incidental materials and supplies when paid or incurred 187 Reg. Secs. 1.162-3(a)(2), (c)(1) Change to deduct non-incidental rotable and temporary spare parts when disposed of 188 Reg. Secs. 1.162-3(a)(3), (c)(2) Change to the optional method for rotable and temporary spare parts 189 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(e) See Rev. Proc. 2014-16, Section 3.02(1).11(8)(a) and (b) for other changes. When a taxpayer is required or allowed to file a single Form 3115 for two or more concurrent changes, the taxpayer must provide a detailed attachment for each change included of the information required by Form 3115 Part II, line 12, and Part IV, line 25 (including the amount of any Section 481(a) adjustment). Also attach an explanation for any other line(s) on the single Form 3115 where the taxpayer·s answer is different for any of the concurrent changes to which the single Form 3115 relates. In general, a change in method of accounting requires the taxpayer to compute an adjustment under Section 481(a). This adjustment is typically computed by comparing the amounts reported for tax years before the year of change under the method the taxpayer employed for those years, and the amounts that would have been reported if the taxpayer had used the new method in those years. If the Section 481(a) adjustment is negative (reduces income), such adjustment is taken into account in full in the year of the change. If the adjustment is positive (increases income), Rev. Proc. 2011-14, 2011-4 IRS 330, Section 5.04(1) generally provides that the adjustment is taken into account ratably over a four-year period, beginning in the year of the change. Rev. Proc. 2014-16 modifies and simplifies Rev. Proc. 2011-16 in important ways. Under paragraph 10.11(6)(b) of the appendix to Rev. Proc. 2011-16, as modified, a modified Section 481(a) adjustment applies to many accounting methods changes made under the tangible property regulations. Under this modified approach, the taxpayer is permitted to calculate its Section 481(a) adjusted as of the first day of year of the change, taking into account only amounts paid or incurred in tax years beginning after December 31, 2013. Effectively, this modification permits taxpayers to make specified accounting methods changes under the tangible property regulations on a cut-off basis. Referring back to table 2-1, the cut-off method applies to all of the listed method changes except a change to the optional method for rotable and temporary spare parts under Regulation 1.162-3(e). 2-26 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 2-18 Section 481(a) Adjustment Versus Modified Section 481(a) Adjustment In order to comply with the tangible property regulations, ABC must change its method of accounting for certain expenditures, to treat such expenditures as capitalized improvements rather than deductible repairs. By comparing the amounts reported for tax years before the year of change under the method ABC employed for those years, and the amounts that would have been reported if ABC had used the new method in those years, a positive Section 481(a) adjustment of $40,000 would result. Absent Rev. Proc. 2014-16, ABC would include $10,000 in income each year for four years, beginning in the year of the change. However, because this change qualifies under Rev. Proc. 2014-16 for the modified Section 481(a) adjustment, ABC may simply begin using the new method in its 2014 tax year. SIMPLIFIED CHANGE PROCEDURES FOR SMALL BUSINESS TAXPAYERS In February 2015, the IRS issued Rev. Proc. 2015-20, 2015-9 IRB, providing simplified accounting methods change procedures for qualifying small business taxpayers to comply with the tangible property regulations. The simplified procedures are generally available to small businesses, including sole proprietorships, with total assets less than $10 million or average annual gross receipts totaling $10 million or less for the prior three taxable years. Under these rules, qualifying taxpayers may change to methods allowed under the regulations on a prospective basis, beginning with their 2014 taxable year (first year beginning after December 31, 2013). Under this procedure, the taxpayer is permitted to calculate his or her Section 481(a) adjusted as of the first day of year of the change, taking into account only amounts paid or incurred in tax years beginning after December 31, 2013. Effectively, this modification permits small businesses to make accounting methods changes under the tangible property regulations on a cut-off basis. In addition, taxpayers choosing this simplified method need not complete and file a Form 3115. If the election to apply the simplified procedure is made, it must be applied consistently to most changes to comply with the tangible property regulations. It must also be applied to method changes related to certain property dispositions subject to Sections 6.37²6.39 of Rev. Proc. 1015-14, 2015-5 IRB. KNOWLEDGE CHECK 8. Rev. Proc. 2014-16 permits certain accounting methods changes under the new tangible property regulations to be made under a cut-off method, without the usual Section 481(a) adjustment. Which accounting methods change is not eligible for this cut-off method? a. b. c. d. Change to the optional method of accounting for rotable and temporary spare parts. Change to deducting non-incidental materials and supplies when used or consumed. Change to deducting incidental materials and supplies when paid or incurred. Change to deducting non-incidental rotable and temporary spare parts when disposed of Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 2-27 2-28 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Chapter 3 DEPRECIATION LEARNING OBJECTIVES After completing this chapter, you should be able to do the following: x x x Recall the fundamentals of MACRS depreciation. Recognize eligibility for Section 179 immediate expensing. Recognize which assets are considered listed property. Depreciation applies only to wasting assets that lose value over time because of wear and tear, physical deterioration, or obsolescence, and have a reasonably ascertainable useful life. Nonwasting tangible assets lacking these characteristics, such as land and works of art, are not depreciable. Taxpayers can recover their cost of certain property, such as equipment they use in their business (or property used for the production of income) by taking deductions for depreciation. Before 1981, depreciation for tax purposes was based on the estimated useful life of business property. Because the useful life of any asset is a subjective assessment, taxpayers and the IRS often disagreed over the question of asset lives. Firms argued for the shortest life over which to recover the tax basis of their assets, while the IRS asserted that a longer recovery period was more realistic. In 1981, Congress enacted a radically new cost recovery system to replace the old depreciation rules. This system, the Accelerated Cost Recovery System (ACRS), established standard recovery lives for different types of business assets and removed nearly all subjectivity from the calculation of tax depreciation. In 1986, Congress refined this system into the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS), which is in effect today. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-1 The method applied depends on the kind of asset involved or when it was placed in service. The following are the various depreciation systems used for regular tax purposes: x x x Property placed in service before 1981 ² Asset Depreciation Range (ADR). Property placed in service after 1980 and before 1987 ²ACRS. Property placed in service after 1986 ²MACRS. This chapter will focus on MACRS, bonus depreciation, and the Section 179 immediate expensing election. 3-2 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System OVERVIEW MACRS applies to tangible business property placed in service after 1986. MACRS actually consists of two systems, the General Depreciation System (GDS) Section 168(a) through (f) and the Alternative Depreciation System (ADS) Section 168(g). Most taxpayers will use GDS. However, in some circumstances, ADS is required, or may be elected by the taxpayer. ADS is required in the following circumstances [see Section 168(g)(1)]: x x x x x Listed property used 50 percent or less for business purposes Tangible property used predominately outside the United States Tax-exempt use and tax-exempt bond-financed property Certain farming property Property imported from certain countries imposing trade restrictions or engaged in discriminatory trade practices In addition, taxpayers may elect, under Section 168(g)(7), to use ADS instead of GDS. The election must cover all tangible personal property in the same property class placed in service during the taxable year. For real property, the election is made on a property-by-property basis. Once made, the election cannot be revoked. MACRS applies to all property placed in service after 1986. The system is referred to as the MACRS to distinguish it from the prior method ACRS, although Section 168 still refers to the system as ACRS. The application of MACRS depends on identifying three variables: the recovery period, the applicable convention, and the depreciation method. MACRS RECOVERY PERIODS MACRS applies to both depreciable real property (buildings, improvements, and other structures permanently attached to the land) and depreciable personal property (any tangible asset not part of a building or other permanent structure) used in a trade, business, or income-producing activity. Depreciation begins when property is placed in service. Property is placed in service when it is ready and available for its intended use, even if actual use does not commence until a later time. MACRS assigns every depreciable asset to 1 of 10 recovery periods ranging from 3 to 50 years. The UHFRYHU\SHULRGVRIDVVHWVRWKHUWKDQUHDOSURSHUW\DUHDVVLJQHGE\6HFWLRQ H EDVHGRQWKHDVVHW·V class life under the depreciation rules of Section 167. One authoritative source of information on asset class lives is Revenue Procedure 87-56 1987-2 C.B. 674, as modified. The asset class life tables from the revenue procedure are also included in IRS Publication 946, How to Depreciate Property. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-3 Recovery Periods for Real Property For real property, the applicable recovery periods are specified in Section 168(c). Residential rental property is assigned a recovery period of 27.5 years. Nonresidential real property is assigned a recovery period of 39 years. Railroad grading and tunnel bores have the longest MACRS recovery period of 50 years. The appropriate recovery period for real property has changed frequently in recent decades. The following summarizes the various recovery periods associated with real property: x x Former Categories: ² Real property placed in service before 1981: based on useful life (usually 35 to 40 years for new property). ² Real property placed in service after December 31, 1980, and before March 16, 1984: ACRS with a 15-year recovery period. ² Low-income housing placed in service after 1980 and before 1987: 15-year recovery period. ² Real property placed in service after March 15, 1984, and before May 9, 1985: ACRS with 18-year recovery period (not low-income housing). ² Real property placed in service after May 8, 1985, and before January 1, 1987: ACRS with a 19-year recovery period (not low-income housing) (unless MACRS was elected for real property placed in service after July 31, 1986). ² Real property placed in service after December 31, 1986, and before May 13, 1993: nonresidential real property: 31.5-year recovery period. Current Categories: ² Real property placed in service after December 31, 1986: residential rental: 27.5-year recovery period. ² Real property placed in service after May 12, 1993: nonresidential real property: 39-year recovery period. Planning for Asset Recovery Periods Owners of commercial buildings generally depreciate the cost of such property over 39 years, to the extent purchase price is allocated to the building. Any purchase price allocated to the land is nondepreciable, with cost recovery occurring only when the property is sold. However, cost segregation studies can assist taxpayers in identifying and quantifying costs buried in the cost of the land and building that qualify for faster depreciation deductions. Cost segregation studies are performed by professionals with expertise in tax and engineering. They typically include a thorough review of blueprints, specifications, and cost data. Under Section 168(i)(6), taxpayers cannot break up a building into components and depreciate each component separately. However, assets installed in a building that are not structural components of that building can be deducted over their shorter recovery period. Some common examples are moveable room partitions, removable wall coverings, removable floor finishes, cabinets and counters, decorative lighting, emergency equipment, signs and graphics, certain electrical and plumbing systems, and air conditioning units. In addition, taxpayers should also consider the extent to which purchase price allocable to land could be attributed to land improvements such as landscaping, parking lots, sidewalks, and irrigation systems. Although land itself is not depreciable, land improvements are depreciated under MACRS using a 15-year recovery period. 3-4 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-1 Cost Segregation Study Himont Corporation recently paid $3 million for a commercial office building. Its initial assessment suggests that $500,000 of such value should be attributed to the land. If the remaining $2,500,000 is treated as 39-year recovery property, first year depreciation on the property would total $61,525 (assuming purchase in the first month of the taxable year). Suppose that a cost segregation study reveals $500,000 of assets within the building that qualify for seven-year recovery under MACRS and $100,000 of land value attributable to land improvements with a 15-year recovery life. In this case, first year depreciation on the property would be as follows. Building, $2,000,000 cost Tangible personal property, $500,000 cost $ 49,145 71,450 Land improvements, $100,000 cost Total first year depreciation 5,000 $125,595 First year depreciation has more than doubled, having increased $64,070. At a 35 percent marginal tax rate, the cost segregation study produced tax savings in just the first year of $22,424. Additional savings will accrue in future periods. KNOWLEDGE CHECK 1. Under MACRS, nonresidential real property is assigned a recovery period of a. b. c. d. 20 years. 27.5 years. 39 years. 50 years. DEPRECIATION CONVENTIONS The depreciation computation requires some assumption about how much depreciation is allowed in the \HDURIDQDVVHW·VDFTXLVLWLRQRUGLVSRVLWLRQ8QGHU6HFWLRQ G DVDJHQHUDOUXOHDOOSHUVRQDO property (assets with recovery periods less than 27.5 years) is assumed to be placed in service or disposed of exactly halfway through the taxable year. This half-year convention means that in the first year of the recovery period, six months of depreciation is allowed, regardless of when the asset was actually placed in service. The same convention applies in the year in which an asset is disposed of. Regardless of the actual date of disposition, the firm may claim six months of depreciation. This half-year convention simplifies depreciation calculations for the taxpayer and administration of the depreciation system for the IRS. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-5 The half-year convention is subject to an important exception found in Section 168(d)(3). If more than 40 percent of the depreciable personal property acquired during a taxable year is placed in service during the last three months of the year, the firm must use a mid-quarter convention with respect to all personal property placed in service during the year. Under this convention, assets placed in service during any quarter (three months) of the year are assumed to be placed in service at the midpoint (1½ months) of the quarter. When an asset whose acquisition was subject to this convention is disposed of, the disposition is treated as occurring at the midpoint of the quarter in which the disposition occurs. The mid-quarter requirement constrains a taxpayer that might be tempted to accelerate future-year property acquisitions into the last quarter of the current year to take advantage of cost recovery deductions available under the half-year convention. Example 3-2 Half-Year Convention During its calendar taxable year, Jones Corporation purchased the following depreciable personal property. Asset Date Placed in Service Depreciable Basis Furniture February 25 $ 70,000 Machine 1 August 1 20,000 Machine 2 December 10 50,000 $140,000 In this case, only 36 percent ($50,000 ÷ $140,000) of the depreciable basis of personal property was placed in service during the last three months of the taxable year. Therefore, Jones uses the half-year convention and calculates six months of depreciation for all three assets. Example 3-3 Mid-Quarter Convention Refer back to example 3-2. Now assume that Jones purchased an additional machine costing $20,000 on December 4. In this case, 44 percent of the depreciable personal property ($70,000 ÷ $160,000) was placed in service in the last three months of the year. Jones must now use the mid-quarter convention for all four assets, with the following result for the current year. Quarter Placed in Service Months of Depreciation Allowed Furniture First 10.5 Machine 1 Third 4.5 Machine 2 Fourth 1.5 Machine 3 Fourth 1.5 Asset 3-6 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Under Section 168(d)(2), a mid-month convention applies to the year in which depreciable real property (assets with recovery periods of 27.5, 39, or 50 years) is placed in service or disposed of. Under this convention, real property placed in service (or disposed of) during any month is treated as placed in service (or disposed of) midway through the month. DEPRECIATION METHODS MACRS assumes zero salvage value at the end of the recovery period of depreciable property [Section 168(b)(4)]. Thus, the entire tax basis of such property is subject to recovery. The method used to calculate annual depreciation under MACRS is a function of the recovery period, as described in Section 168(b). Assets with a 3-year, 5-year, 7-year, or 10-year recovery period are depreciated using a 200 percent (double) declining-balance method. Assets with a 15-year or 20-year recovery period are depreciated using a 150 percent declining-balance method. In each case, the depreciation method switches to straight line in the first year in which a straight-line computation over the remaining recovery period results in a greater deduction than the declining-balance method. For these six classes of personal property, MACRS lives up to its name ² depreciation deductions are indeed accelerated into the early years of the recovery period. Such front-end loading of depreciation further reduces the after-tax cost of tangible personal property. Before 1987, buildings and other types of real property could also be depreciated using accelerated methods. Since 1987, properties with 25-year, 27.5-year, 39-year, or 50-year recovery periods must be depreciated using the straight-line method. Thus for real property, MACRS is an accelerated cost-recovery system in name only. Straight-line depreciation is computed by dividing the cost of the asset equally over its recovery period. The annual depreciation rate under straight-line is simply 1 divided by the recovery period. In the year of acquisition and disposition, the mid-month convention will reduce the otherwise allowable depreciation. The required computation is simply the annual depreciation multiplied by the ratio of months depreciation allowed over total months in the taxable year. Note: Taxpayers have the option of electing to use either the 150 percent declining balance or the straight-line method for 3-year through 20-year property over the MACRS class life, in lieu of the 200 percent declining balance method (the standard method under MACRS) [Section 168(b)(2)]. This election applies to all property in the MACRS class placed in service during the year. Once made, the election is irrevocable for that year. IRS Depreciation Tables To allow taxpayers to avoid the MACRS math process, the IRS publishes a set of tables containing annual percentages that incorporate the MACRS computational rules. One authoritative source of these tables is Revenue Procedure 87-57 1987-2 C.B. 687, as modified. The MACRS recovery tables from the revenue procedure are also included in IRS Publication 946, How to Depreciate Property. The annual percentages found in these tables are multiplied against the initial undepreciated basis of the asset to compute depreciation for the year. The table percentages also incorporate the appropriate convention for the year of acquisition. However, the table percentages assume the asset will be held until fully depreciated. If property is sold prior to the end of its recovery life, depreciation in the year of disposition must be adjusted to apply the appropriate convention. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-7 Exhibit 3-1 contains the annual percentages for the six recovery periods for business personal property, based on the half-year convention. Exhibits 3-2 through 3-5 provide the annual percentages for personal property under the mid-quarter convention. Exhibit 3-1 MACRS GDS for Personal Property Using Half-Year Convention Recovery Period 7-Year 3-8 5-Year 10-Year Year 3-Year Depreciation Rate 15-Year 20-Year 1 33.33% 20.00% 14.29% 10.00% 5.00% 3.750% 2 44.45 32.00 24.49 18.00 9.50 7.219 3 14.81 19.20 17.49 14.40 8.55 6.677 4 7.41 11.52 12.49 11.52 7.70 6.177 5 11.52 8.93 9.22 6.93 5.713 6 5.76 8.92 7.37 6.23 5.285 7 8.93 6.55 5.90 4.888 8 4.46 6.55 5.90 4.522 9 6.56 5.91 4.462 10 6.55 5.90 4.461 11 3.28 5.91 4.462 12 5.90 4.461 13 5.91 4.462 14 5.90 4.461 15 5.91 4.462 16 2.95 4.461 17 4.462 18 4.461 19 4.462 20 4.461 21 2.231 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Exhibit 3-2 MACRS GDS for Personal Property Using Mid-Quarter Convention Placed in Service in First Quarter Recovery Period 7-Year Year 3-Year 10-Year 5-Year Depreciation Rate 15-Year 20-Year 1 58.33% 35.00% 25.00% 17.50% 8.75% 6.563% 2 27.78 26.00 21.43 16.50 9.13 7.000 3 12.35 15.60 15.31 13.20 8.21 6.482 4 1.54 11.01 10.93 10.56 7.39 5.996 5 11.01 8.75 8.45 6.65 5.546 6 1.38 8.74 6.76 5.99 5.130 7 8.75 6.55 5.90 4.746 8 1.09 6.55 5.91 4.459 9 6.56 5.90 4.459 10 6.55 5.91 4.459 11 0.82 5.90 4.459 12 5.91 4.460 13 5.90 4.459 14 5.91 4.460 15 5.90 4.459 16 0.74 4.460 17 4.459 18 4.460 19 4.459 20 4.460 21 0.565 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-9 Exhibit 3-3 MACRS GDS for Personal Property Using Mid-Quarter Convention Placed in Service in the Second Quarter Recovery Period 7-Year 3-10 10-Year Year 3-Year 5-Year Depreciation Rate 15-Year 20-Year 1 41.67% 25.00% 17.85% 12.50% 6.25% 4.688% 2 38.89 30.00 23.47 17.50 9.38 7.148 3 14.14 18.00 16.76 14.00 8.44 6.612 4 5.30 11.37 11.97 11.20 7.59 6.116 5 11.37 8.87 8.96 6.83 5.658 6 4.26 8.87 7.17 6.15 5.233 7 8.87 6.55 5.91 4.841 8 3.33 6.55 5.90 4.478 9 6.56 5.91 4.463 10 6.55 5.90 4.463 11 2.46 5.91 4.463 12 5.90 4.463 13 5.91 4.463 14 5.90 4.463 15 5.91 4.462 16 2.21 4.463 17 4.462 18 4.463 19 4.462 20 4.463 21 1.673 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Exhibit 3-4 MACRS GDS for Personal Property Using Mid-Quarter Convention Placed in Service in the Third Quarter Recovery Period 7-Year Year 3-Year 5-Year 1 25.00% 15.00% 10.71% 2 50.00 34.00 25.51 3 16.67 20.40 4 8.33 10-Year Depreciation Rate 15-Year 20-Year 3.75% 2.813% 18.50 9.63 7.289 18.22 14.80 8.66 6.742 12.24 13.02 11.84 7.80 6.237 5 11.30 9.30 9.47 7.02 5.769 6 7.06 8.85 7.58 6.31 5.336 7 8.86 6.55 5.90 4.936 8 5.53 6.55 5.90 4.566 9 6.56 5.91 4.460 10 6.55 5.90 4.460 11 4.10 5.91 4.460 12 5.90 4.460 13 5.91 4.461 14 5.90 4.460 15 5.91 4.461 16 3.69 4.460 7.50% 17 4.461 18 4.460 19 4.461 20 4.460 21 2.788 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-11 Exhibit 3-5 MACRS GDS for Personal Property Using Mid-Quarter Convention Placed in Service in the Fourth Quarter Recovery Period 7-Year Year 1 3-12 3-Year 8.33% 5-Year 5.00% 10-Year Depreciation Rate 3.57% 2.50% 15-Year 20-Year 1.25% 0.938% 2 61.11 38.00 27.55 19.50 9.88 7.430 3 20.37 22.80 19.68 15.60 8.89 6.872 4 10.19 13.68 14.06 12.48 8.00 6.357 5 10.94 10.04 9.98 7.20 5.880 6 9.58 8.73 7.99 6.48 5.439 7 8.73 6.55 5.90 5.031 8 7.64 6.55 5.90 4.654 9 6.56 5.90 4.458 10 6.55 5.91 4.458 11 5.74 5.90 4.458 12 5.91 4.458 13 5.90 4.458 14 5.91 4.458 15 5.90 4.458 16 5.17 4.458 17 4.458 18 4.459 19 4.458 20 4.459 21 3.901 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-4 MACRS Depreciation Using IRS Tables Parker bought a computer for $38,000 and placed it in service on September 19. The computer is five-year property subject to the half-year convention. Using exhibit 3-1, Parker will depreciate the computer according to the following schedule. Year Initial Basis Table Percentage 20.00% Depreciation 1 $38,000 $ 7,600 2 38,000 32.00 12,160 3 38,000 19.20 7,296 4 38,000 11.52 4,378 5 38,000 11.52 4,378 6 38,000 5.76 2,188 Note that the table percentages are not adjusted in year one or year six; the half-year convention is already taken into account in computing these percentages. Example 3-5 Adjusting IRS Tables for Early Disposition Refer back to example 3-4. If Parker sells the computer on May 3 of Year 4, MACRS depreciation for that year is computed by multiplying the otherwise applicable table percentage by 50 percent, as follows: Year four sale depreciation: $38,000 × 11.52% × 50% = $2,189 The IRS also provides tables for computing annual depreciation for real property. For years other than the year of acquisition and retirement, the table percentages are identical. Thus, the tables are really helpful only for the first and last years of the recovery period in which the mid-month convention applies. Because of their length and limited usefulness, these tables are not reproduced here. MACRS is applied to the initial tax basis of property as discussed in this chapter, regardless of whether the property is acquired new or used. If the taxpayer makes subsequent expenditures that increase the value or extend the useful life of the asset, under Section 263(a), such expenditures are capitalized as improvements. The cost of such improvements is subject to recovery under MACRS. Section 168(i)(6) provides that improvements are treated as property placed in service on the date of the improvement. Thus, the cost of improvements is depreciated using the same methods and lives as the original property, commencing on the date of the improvement. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-13 Correction of Depreciable Class Life or Method Personal property and realty placed in service after 1986 is normally depreciated under either the MACRS or, if elected or required, the alternative depreciation system (ADS). The IRS has argued that taxpayers using an improper depreciation method, such as depreciating property over seven years when the correct recovery period is five years, must file a request for change in accounting method to correct the recovery period. IRS Form 3115, Application for Change in Accounting Method, Schedule E (page 8), would be used for such changes. Court Activity Several recent court cases have held that the correction of a depreciable recovery period or class life is not a change in accounting method requiring advance approval of the IRS. These cases have relied on Reg. Sec. 1.446-1, which previously held that an adjustment in the useful life of a depreciable asset does not constitute a change in method of accounting. In a recent case, a retail grocery business constructed gas station convenience stores, initially classifying the real estate as nonresidential commercial property with a 31.5 or 39 year recovery period. Subsequently, the corporation reclassified the structures as 15 year recovery property after learning that gas station convenience stores have a special recovery period. Both the Tax Court and the Fifth Circuit found that this correction of the recovery period on the convenience store buildings was not an unauthorized change in accounting method (Brookshire Brothers Holding, Inc. and Subsidiaries v. Comm., 20031 USTC ¶50,214, CA-DII·J7&0HPR-150). Similarly, the Eighth Circuit has determined that a glass manufacturing business that recategorized certain plant assets from one asset category to another for purposes of MACRS was not changing an accounting method. The court noted that reallocating an asset into an existing asset category for purposes of MACRS depreciation more closely resembled a correction of a reporting error or inconsistency than a change in accounting method (2·6KDXJKQHVV\Y&RPP, 2003-1 USTC ¶50,522, CA-UHY·J 2002-1 USTC ¶50,235, DC, Mn.). The Tax Court has also ruled that a taxpayer who changed the classification of equipment from DDB or SL to ADS is not required to request a change in accounting method (Green Forest Manufacturing, Inc. v. Comm., TC Memo 2003-75, 3/14/2003). The tax court issued a non-taxpayer friendly ruling that stated that a taxpayer could not change the useful lives of assets based on a cost segregation study from what was originally put forth in the asset allocation schedule agreed to by the buyer and seller at the time of the purchase. (Peco Foods Inc. et al,. TC Memo 2012-18). New Regulations and IRS Procedures Final regulations (Reg. Secs. 1.167(e)²1, 1.446²1, and 1.1016²3) have been issued (TD 9307, 2007-7 IRB 470) that discuss changes in computing depreciation or amortization and changing an asset from a nondepreciable or non-amortizable asset to a depreciable or amortizable asset.1 The Regulations are effective beginning on December 28, 2006, and apply to changes in depreciation made by a taxpayer for assets placed into service in tax years ending on or after December 30, 2003. The final regulations retain the temporary rules which provide that the rules in Reg. Sec. 1.167(e)²1 (change in depreciation method under Reg. Sec. 1.167(e)²1(b), (c), and (d)) made without the consent of 1 Reg. Secs. 1.167(e)²1T, 1.446²1T, and 1.1016²3T are removed. 3-14 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited the Commissioner apply only to property for which depreciation is determined under Section 167 (other than under Sections 168, 1400I, 1400L, or 1400N(d), or former Section 168). The final regulations, at Reg. Sec. 1.446-1(e)(3), state that the following are to be considered accounting method changes under Section 446(e): x x x x x x x Changing the treatment of an asset from non-depreciable or non-amortizable to depreciable or amortizable, or vice versa. Changing an item that was treated consistently as an expense to a depreciable asset, or vice versa. Changing the depreciation method, period of recovery, or convention (however, in this case note that the automatic switch from double declining balance to straight line in the MACRS tables is not a method change because it is prescribed by the DDB method). Changing to or from claiming the additional first year depreciation deduction provided by Sections 168(k), 1400L(b), or 1400N(d) under certain circumstances. Changing the salvage value to zero for an asset for which the salvage value is expressly zero according to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) (or other published administrative guidance). Changing the accounting for assets from a single asset account to a multiple asset account (pooling assets), or vice versa, or changing from one type of pooling to a different type of pooling. Changing the method of identifying which assets have been disposed of in the case of assets that are mass assets accounted for using multiple asset accounts (or pools). The regulations do not change the procedures for obtaining consent; therefore, the rules in Reg. Sec. 1.446²1(e)(3) are applicable to a change in depreciation that is considered to be a change in a method of accounting. The regulations clarify that a change in depreciation that is due to a posting or mathematical error (or a change in underlying facts) is not a change in a method of accounting. Other items that are not accounting method changes include the following: x x x x x Adjusting the useful life of a depreciable or amortizable asset for which depreciation is determined under Section 167 (other than under Sections 168, 1400I, 1400L, or 1400N(d), or former Section 168). (This rule does not apply, however, if a taxpayer is changing to or from a useful life that is specifically assigned by the IRC or other published administrative guidance.) Changing the computation of depreciation or amortization allowances in the tax year in which the use of an asset changes in the hands of the same taxpayer. Making a late depreciation election or the revocation of a timely valid depreciation election except as otherwise provided by the IRC or other published administrative guidance. Changing the salvage value (except as mentioned previously). Changing the placed-in-service date of a depreciable or amortizable asset. (Since changing the placedin-service date is not an accounting method change, no Section 481 adjustment is required or permitted.) A Section 481 adjustment is not required or permitted for a change from one permissible method of depreciation (or amortization) to another permissible method because this type of change is accounted for using the cutoff method or a modified cutoff method. However, changing from an impermissible method or changing to or from expensing an asset to depreciating or amortizing it does result in a Section 481 adjustment. Example 9 from Reg. Sec. 1.446-1(e)(2)(iii) demonstrates changing the method of accounting due to a cost segregation study. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-15 Example 3-6 Reg. Sec. 1.446-1(e)(2)(iii) (Example 9) Change in Method of Accounting s Cost Segregation Study In 2009, A1, a calendar-year taxpayer engaged in the trade or business of manufacturing knitted goods, purchased and placed in service a building and its components at a total cost of $10,000,000 for use in its manufacturing operations. A1 classified the $10,000,000 as nonresidential real property under Section 168(e). A1 elected not to deduct the additional firstyear depreciation provided by Section 168(k) on its 2009 federal tax return. As a result, on its 2009, 2010, and 2011 federal tax returns, A1 depreciated the $10,000,000 under the general depreciation system of Section 168(a), using the straight line method of depreciation, a 39-year recovery period, and the mid-month convention. In 2012, A1 completes a cost segregation study on the building and its components and identifies items that cost a total of $1,500,000 as Section 1245 property. As a result, the $1,500,000 should have been classified in 2009 as five-year property under Section 168(e) and depreciaWHGRQ$pV 2009, 2010, and 2011 federal tax returns under the general depreciation system, using the 200 percent, declining balance method of depreciation, a five-year recovery period, and the half-year FRQYHQWLRQ$pVFKDQJHWRWKLV depreciation method, recovery period, and convention is a change in method of accounting, and results in a Section 481 adjustment. The useful life exception does not apply because the assets are depreciated under Section 168. Waiver of Two-year Rule Previously, the IRS position was that an incorrect depreciation method must be used for two consecutive years before it is considered an accounting method. Accordingly, if a depreciation error occurred only for a single year, the taxpayer was required to amend that prior year rather than correct the change currently as an accounting method change (Revenue Ruling 90-38, 1990-1 CB 57). However, in conjunction with the clarifications in the regulations regarding accounting method changes, the IRS has dropped this twoyear rule with respect to depreciation changes. Accordingly, a taxpayer may either correct a one-year depreciation error by making a current Form 3115 accounting method change or by filing an amended return to correct the year of the error (Revenue Procedure 2004-11, 2004-1 CB 211, as modified by Revenue Procedure 2007-16, 2007-1 CB 358). Note: This change is effective for a Form 3115 filed for tax years ending on or after December 30, 2003. Example 3-7 Correction of Prior Year Depreciation Error H Corp acquired and placed in service $100,000 of tangible personal property in 2015, categorizing the equipment as seven-year property. However, in 2016, H Corp discovers that these assets should properly be classified as five-year property under the MACRS recovery periods. Prior to Revenue Procedure 2004-11, H Corp could only correct this error by filing an amended return for 2015. However, H Corp now has the option of either filing an amended 2015 return or filing a Form 3115 with its 2016 return, and claiming the omitted depreciation as a Section 481(a) negative amount in 2016. 3-16 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Corrections in Year of Disposition Revenue Procedure 2004-DOVRVROYHVWKH´DOORZHGRUDOORZDEOHµWUDSWKDWFRXOGDULVHZKHQDWD[SD\HU disposed of an asset but had not properly claimed all permissible depreciation. In the past, the adjusted tax basis of the asset must reflect all depreciation allowed or allowable, whether or not actually claimed. Revenue Procedure 2004-11 allows a taxpayer, in the year of disposition of an asset, to file a Form 3115 automatic consent accounting method change to claim all prior omitted depreciation in the year of disposition (Revenue Procedure 2004-11, 2004-1 CB 211, as modified by Revenue Procedure 2007-16, 2007-1 CB 358)). Revenue Procedure 2007-16, 2007-4 IRB 358, is designed to provide further relief to taxpayers changing their method of accounting for a disposed asset in cases in which depreciation has not previously been taken (or too little has been taken) on the asset. Ordinarily, when a taxpayer has used an impermissible method for two years, the taxpayer is considered to have adopted that as a method of accounting. Taxpayers that have adopted a method of accounting then usually must secure the permission of the Commissioner in order to change that method of accounting according to Reg. Sec. 1.446²1. The new Procedure allows a taxpayer to file a Form 3115 with an original federal tax return for the tax year in which the disposition of the property occurs to account for the depreciation difference. The procedure also clarifies that it is an accounting method change under Section 446(e) and Reg. Sec. 1.446²1(e) when a taxpayer changes from an impermissible method of determining depreciation expense for property in two (or more) consecutive tax returns. The Procedure also extends the application of this rule to property dispositions that occurred in tax years that end prior to December 30, 2003. This rule applies generally to property that is subject to depreciation under Sections 167, 168, 197, 1400I, 1400L(c), and to former Section 168. This provision also applies to additional first year depreciation deduction provisions. The Procedure states that this rule does not apply to: x x x x Property to which Section 1016(a)(3) (property held by a tax-exempt organization) applies, Property for which a taxpayer is revoking a timely valid depreciation election, or making a late depreciation election, under the IRC, regulations, or other guidance, Property for which the taxpayer deducted the cost or other basis of the property as an expense, or Property disposed of by the taxpayer in a transaction to which a non-recognition provision applies unless the taxpayer elects to treat the entire basis, both the exchanged and excess basis of the replacement MACRS property as being placed in service by the taxpayer at the time of replacement and therefore treats the adjusted depreciable basis of the relinquished MACRS property as being disposed of. This Procedure is effective for Forms 3115 filed for tax years which end on or after December 26, 2006. Automatic Consent Procedures for Depreciation Method Changes Revenue Procedure 2011-14 2011-4 IRB 330 (as modified by Revenue Procedure 2012-39 2012-2 CB 470) contains automatic consent procedures for depreciation methods changes. These procedures have been supplemented by Revenue Procedure 2015-14 2015-5 IRB 459. Under Revenue Procedure 2015-14, taxpayers may receive automatic consent to change from an impermissible depreciation method to a permissible method or from one permissible method to another permissible method. Taxpayers changing from an impermissible method that has only been employed one year may follow the rules for making an automatic change or may file an amended return for the year the property was placed in service as lRQJDVWKLVLVEHIRUHWKHVXFFHHGLQJ\HDU·VUHWXUQLVILOHG Revenue Procedures 2011-14 and 2015-14 contain detailed requirements for information to be attached to the Form 3115 requesting the automatic change. However, Revenue Procedure 2015-14 also provides Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-17 reduced filing requirements for qualified small taxpayers (those with average annual gross receipts of $10 million or less). KNOWLEDGE CHECK 2. The computation of cost recovery in the year of acquisition of depreciable real property is based on a a. b. c. d. Half-year convention. Mid-month convention. Mid-quarter convention. Daily proration of the applicable annual depreciation amount. 3. MACRS provides that depreciation of personal property be computed using a. b. c. d. 3-18 The straight-line method. Accelerated-depreciation methods. The same methods adopted for financial accounting purposes. Any method elected by the taxpayer. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Alternative Depreciation System IRC Sec. 168(g) provides that an alternative depreciation system (ADS) for property placed in service after 1986 must be used to calculate (1) earnings and profits of a foreign and domestic corporation; and (2) depreciation for the following property: (a) any tangible property used predominantly outside the U.S.; (b) any tax-exempt use property; (c) any tax-exempt bond-financed property; (d) certain imported property; (e) property for which an ADS irrevocable election has been made; and (3) any property used predominantly in a farming business and placed in service during any tax year in which an election is PDGHQRWWRDSSO\WKH81,&$3UXOHVWRFHUWDLQIDUPLQJFRVWV,WDOVRPXVWEHXVHGIRU´OLVWHGSURSHUW\µ not predominately used in business [Section 280F(b)]. Under the alternative depreciation system, the deduction is computed by the straight-line method with no salvage value. The recovery periods used are as follows: x x x x x x Personal property with no class life: 12 years (half-year convention). Qualified technological equipment: 5 years. Automobile or light general purpose truck: 5 years. Nonresidential real and residential rental property: 40 years (mid-month convention). Any Section 1245 property that is real property with no class life: 40 years. All other property: Class life (half-year convention). The alternative depreciation system can be irrevocably elected for any tax year. If this election is made, this system applies to all property in the MACRS class placed in service during the tax year. For residential rental property and nonresidential real property, this election can be made on a property-byproperty basis. The election to use the alternative depreciation system is in addition to the election to recover costs using the straight-line method over the MACRS recovery period. Observation: The alternative depreciation system election generally requires longer straight-line recovery periods than straight-line MACRS, which is claimed over the regular recovery period. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-19 Section 179 Limited Expensing Election MAXIMUM ANNUAL DEDUCTION AND ANNUAL ACQUISITION THRESHOLD Section 179 provides taxpayers an election to expense (rather than capitalize) a limited dollar amount of the cost of qualifying property placed in service during the taxable year. Through this immediate tax benefit, Section 179 is intended to provide an incentive for taxpayers to invest in tangible business assets. This incentive is targeted at smaller businesses, through limits on its availability. The election allows many small firms to simply deduct the cost of their newly acquired assets and avoid the burden of maintaining depreciation or amortization schedules. Section 179 has been part of the tax code for decades. However, in its original form it provided a very limited deduction amount ($10,000 or less in years before 1990, gradually increasing to $24,000 in 2001). The Section 179 expense election is also subject to an annual acquisition threshold. If a firm purchases more than the threshold amount of qualifying property in a year, the annual dollar amount is reduced by the excess of the total cost of the property over the threshold [Section 179(b)(2)]. Beginning in 2003, Congress began proactively using Section 179 as a short-term economic stimulus. The following table summarizes the annual deduction amounts and annual acquisition thresholds for the Section 179 deduction over the past two decades. Exhibit 3-6 Section 179 Annual Deduction and Acquisition Threshold Amounts Period Maximum Annual Deduction Annual Acquisition Threshold 2003-2006 $100,000* $ 400,000* 2007 $125,000 $ 500,000 2008-2009 $250,000 $ 800,000 2010-2014 $500,000 $2,000,000 2015 $500,000 $2,000,000 2016 $500,000 $2,010,000 20172 $510,000 $2,030,000 *Adjusted annually for inflation during these years. 2 Rev. Proc. 2016-55, 2016-45 IRB. 3-20 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited The $500,000 deduction amount for 2014 was retroactively extended by the Tax Increase Prevention Act of 2014. The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 makes the $500,000 deduction permanent and indexes both the deduction amount and the annual acquisition threshold for inflation. QUALIFIED PROPERTY Under Section 179(d)(1), qualified property includes the following types of depreciable assets. x x x x x Tangible personal property Other tangible property (except buildings and their structural components) used as ² An integral part of manufacturing, production, or extraction; or furnishing transportation, communications, electricity, gas, water, or sewage disposal services ² A research or bulk-storage facility used in connection with any of the preceding activities Certain single-purpose agricultural or horticultural structures Storage facilities (except buildings and their structural components) used in connection with distributing petroleum or any primary product of petroleum Off-the-shelf computer software, the cost of which is amortizable over 36 months (placed in service in tax years beginning in 2010 through 2014) In general, the election does not apply to real property, with limited exceptions explained as follows. In addition, qualified property must be acquired by purchase from a taxpayer that is not a related party [Section 179(d)(2)]. The provision for tax years beginning in 2010 through 2014 had been modified to allow for certain real property interests to be included under Section 179 for these years. The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 permanently extends this provision. IRC Section 179(g) provides that the property must be x x x of a character subject to an allowance for depreciation, acquired by purchase for use in the active conduct of a trade or business, and not described in the last sentence of Section 179(d)(1). The provision defined qualified real property as x x x qualified leasehold improvement property described in Section 168(e)(6), qualified restaurant property described in Section 168(e)(7), and qualified retail improvement property described in Section 168(e)(8). For tax years beginning in 2010 through 2015, the Section 179 amount that can be taken with regard to qualified real property was limited to $250,000 out of the potential $500,000 for each year. The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 eliminates the $250,000 cap beginning in 2016. Where an amount was elected that cannot be used due to this cap limitation, it will be treated as if the election had not been made for that amount. If this occurs, the amount is treated as being placed in service on the first day of the tax year. If there are multiple properties involved where this limit applies, the amount disallowed is determined using a ratio method specified in the provision. The Committee Report (JCX-47-10) confirms that the taxpayer may elect not to treat qualified real property as Section 179 eligible property. Taxpayers that purchase qualifying property with an aggregate cost in excess of the limited dollar amount may expense part of the cost of a specific asset or assets. The remaining unexpensed cost is capitalized Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-21 and recovered through depreciation or amortization. Because the Section 179 deduction is an election to expense rather than capitalize qualifying costs, it reduces the depreciable basis of the asset for applying MACRS, and reduces adjusted tax basis for purposes of computing gain or loss on disposition of qualifying property. Example 3-8 Section 179 With MACRS In July 2017, Bennett Corporation acquired and placed in service tangible personal property with a seven-year recovery life costing $540,000. This was the only qualified property acquired during the year. Bennett may elect to deduct $510,000 of the cost under Section 179. The remaining cost of $30,000 will be depreciated under the normal MACRS rules, beginning in 2017. The first-year recovery percentage for MACRS seven-year property (assuming the halfyear convention) is 14.29 percent. Thus, Bennett is allowed MACRS depreciation of $4,287. If a firm purchases more than a threshold amount of qualifying property in a year, the annual dollar amount is reduced by the excess of the total cost of the property over the threshold [Section 179(b)(2)]. As indicated in exhibit 3-6, for 2010 through 2015, the threshold was $2 million. Because of this excess property limitation, a firm that purchases more than $2.5 million of qualifying property in each of these tax years cannot benefit from a Section 179 election, because its limited dollar amount is reduced to zero. With passage of the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015, the $2,000,000 threshold limitation was made permanent and indexed for inflation. The 2017 threshold amount is $2,030,000. Example 3-9 Annual Acquisition Threshold Ryan Inc. purchased $2,038,000 of equipment in 2017. Consequently, its excess amount of qualifying property was $8,000 ($2,038,000 t $2,300,000 2017 threshold). Because of the excess property limitation, Ryan may expense only $502,000 of the cost of its qualifying property ($510,000 2017 limited dollar amount t $8,000 excess). It must capitalize the remaining $1,536,000 cost and recover it through MACRS depreciation. An allowable expense amount reported to a partner or S corporation shareholder on Schedule K-1 is not DXWRPDWLFDOO\GHGXFWLEOHRQWKDWRZQHU·VWD[UHWXUQ,QWKHFDVHRISDUWQHUVKLSVDQG6 corporations, the annual dollar limitation under Section 179 is applied at both the entity (partnership or S corporation) and the owner (partner or shareholder) level, under Section 179(d)(8). However, Reg. Sec. 1.179-2(b)(3) and (4) provide that the cost of Section 179 property placed in service by a partnership or S corporation is not attributed to any partner or shareholder for purposes of the annual acquisition threshold. 3-22 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-10 Partnership Section 179 Deduction In 2017, Kane Partnership placed in service qualifying property with a total cost of $560,000. It elected a Section 179 deduction of $510,000 with respect to these acquisitions. Randall Jones, a 40 percent partner in Kane, was allocated $204,000 of Section 179 deduction related to $224,000 of qualifying acquisitions on his 2017 Schedule K-1 from Kane. Independent of his partnership interest in Kane, Randall acquired and placed in service $400,000 of qualifying property during 2017. Randall is eligible to elect Section 179 for these acquisitions in an amount not greater than $306,000 ($510,000 annual limitation t $204,000 from Kane). 6XSSRVHWKDW5DQGDOOpVLQGHSHQGHQW7 acquisitions totaled $1,900,000. Even though the sum of his independent acquisitions and those attributed from the partnership ($224,000) exceeds the 2017 annual acquisition threshold of $2,030,000, because his independent acquisitions are less than the threshold he is entitled to a Section 179 deduction of $510,000. Randall is eligible to elect Section 179 for his independent acquisitions in an amount not greater than $306,000 ($510,000 2017 annual limitation t $204,000 from Kane). Example 3-11 Partnership Section 179 Deduction Limited Refer back to example 3-10:KDWLI5DQGDOOpVLQGHSHQGHQW7 acquisitions totaled $2,500,000? In this case, his independent acquisitions are sufficient to reduce his allowable Section 179 deduction to zero. He may not deduct the $204,000 Section 179 amount allocated from the partnership, despite its election. Instead, he is permitted to deduct MACRS depreciation on his $2VKDUHRISDUWQHUVKLSDFTXLVLWLRQVVXEMHFWWR.DQHpV6HFWLRQ election. Randall must calculate and track these deductions on his personal return because the partnership considers the tax basis of these acquisitions to be zero. Component members of a controlled group on December 31 are treated as one taxpayer for the dollar limit. The expense deduction may be claimed by one member of the group or pursuant to an agreement among the members or allocated among several members if a consolidated return is filed. However, no member of the group can receive an allocation exceeding the cost of qualifying property bought and placed in service by that member. A statement must be attached to the consolidated return claiming an election to expense the cost. In a consolidated return covering all members, an allocation among them cannot be revoked after the due date of the return (including extensions) of the common parent [Reg. Sec. 1.179-2(b)(7)]. TAXABLE INCOME LIMITATION Once a firm elects to expense the cost of qualifying property, the expense is generally deductible. However, the deductible amount in any given year is limited to taxable business income computed without regard to the deduction. Any nondeductible expense resulting from this taxable income Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-23 limitation carries forward to succeeding taxable years (Section 179(b)(3) and Reg. Sec. 1.179-3). The carryforward of a nondeductible expense to a succeeding taxable year does not increase the limited dollar amount for such year. In other words, the maximum allowable deduction in any taxable year is applied to the combination of current acquisitions and carryforwards from prior tax years. In the case of partnerships and S corporations, the taxable income limitation, distinguished from the deduction limit previously discussed, applies to the partnership or S corporation and to each partner or shareholder [Section 179(d)(8)]. That rule is amplified in Reg. Sec. 1.179-2(c)(2), which has been upheld as valid by the Tax Court and Seventh Circuit [Hayden, 2000-1 USTC ¶50,219, CA- DII·J7& No. 115]. Amounts elected with respect to qualified real property cannot be carried over to years that begin after 2015. Where an amount was elected that cannot be used due to this limitation, it will be treated as if the election had not been made for that amount. If this occurs, the amount is treated as being placed in service on the first day of the tax year that begins in 2015. If there are multiple properties involved where this limit applies, the amount disallowed is determined using a ratio method specified in the provision. $25,000 VEHICLE LIMIT The 2004 Jobs Act decreased the Section179 limit from the former $100,000 level to $25,000 for vehicles not subject to the luxury vehicle depreciation limits of Section 280F. This new provision applies to any automobiles, trucks, vans, or SUVs with a weight rating more than 6,000 pounds, but not more than 14,000 pounds. The change is effective for vehicles placed in service after October 22, 2004 [Section 179(b)(5)]. Exceptions The definition of a more than 6,000-pound vehicle subject to the lower $25,000 Section 179 limit excludes three categories: x x x Any vehicle GHVLJQHGWRKDYHDVHDWLQJFDSDFLW\RIPRUHWKDQQLQHSHUVRQVEHKLQGWKHGULYHU·VVHDW (hotel shuttle van), Any vehicle equipped with a cargo area of at least six feet in interior length which is an open area or is designed for use as an open area but is enclosed by a cap and is not readily accessible directly from the passenger department (a pickup truck), or Any vehicle that has an integral enclosure, fully enclosing the driver compartment and load carrying GHYLFHGRHVQRWKDYHVHDWLQJUHDUZDUGRIWKHGULYHU·VVHDWDQGKDVQRERG\VHFWLRQSURWUXGLQJPRUH than 30 inches ahead of the leading edge of the ZLQGVKLHOG DQHOHFWULFLDQ·VYDQ If a vehicle meets one of these three exceptions and exceeds the 6,000-pound gross vehicle weight rating, the vehicle remains eligible for the full Section 179 deduction ($500,000 for tax years after 2009). MAKING THE ELECTION The Section 179 election is made by taking the expensing deduction on Form 4562. In general, the election under Section 179 must be made on the taxpayHU·VILUVWLQFRPHWD[UHWXUQIRUWKHWD[DEOH\HDUWR which it applies, whether or not the return is timely filed. 3-24 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited EFFECT OF EXPENSING ON CORPORATE EARNINGS AND PROFITS Any amount taken as a Section 179 expensing deduction is treated as a deduction taken ratably over a five-\HDUSHULRGIRUSXUSRVHVRIFRPSXWLQJDFRUSRUDWLRQ·VHDUQLQJVDQGSURILWV [Section 312(k)(3)(B)]. ADDITIONAL EXPENSING PROVISIONS The Code also contains the following sections which allow for expensing but which are not explored in greater detail in this course: x x x x x Section 179A Deduction for clean-fuel vehicles and certain refueling property, Section 179B Deduction for capital costs incurred in complying with EPA sulfur regulations, Section 179C Election to expense certain refineries, Section 179D First year deduction for energy efficient commercial building property, and Section 179E Election to expense advanced mine safety equipment. KNOWLEDGE CHECK 4. Due to the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act (passed on December 18, 2015)the maximum annual Section 179 deduction for qualified property placed in service in 2016 is a. b. c. d. $2,000,000. $250,000. $100,000. $500,000. 5. Qualified property for the Section 179 deduction includes a. b. c. d. Depreciable personal property. Depreciable real property. Internally developed software. Property purchased from a related party. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-25 First-Year Bonus Depreciation Qualified property placed in service after December 31, 2007, and before September 9, 2010, was eligible for additional 50 percent bonus depreciation in the year of acquisition [see Section 168(k)]. The 2010 Tax Relief Act provided for 100 percent bonus depreciation in the year of acquisition for qualified property placed in service after September 8, 2010, and before January 1, 2012. This generous incentive provision thus permits a full deduction for the cost of qualifying property in the year of acquisition. For qualifying property placed in service during calendar years 2012 through 2014, 50 percent bonus depreciation is permitted. The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 extends 50 percent bonus depreciation for five years, thru December 31, 2019. The percentage phases down to 40 percent for property placed in service in 2018 and to 30 percent for property placed in service in 2019. The bill also modifies the alternative minimum tax (AMT) rules to increase the amount of unused AMT credits that can be claimed in lieu of bonus depreciation. Bonus depreFLDWLRQZLOOQRZEHDOORZHGIRU´TXDOLILHG LPSURYHPHQWSURSHUW\µ7KHELOODOVRVSHFLILHVWKDWFHUWDLQWUHHVYLQHVDQGIUXLW-bearing plants will be eligible for bonus depreciation when planted or grafted, rather than when placed in service. During the past decade, Congress has frequently used first time bonus depreciation as an incentive to acquire business property. An additional first-year depreciation deduction equal to 30 percent of depreciable basis was available with respect to qualified property placed in service after September 10, 2001, and before January 1, 2005. The bonus depreciation percentage was increased to 50 percent for qualifying acquisitions after May 5, 2003, and before January 1, 2005. During the later period, taxpayers could choose whether to apply the 30 percent or 50 percent deduction. QUALIFYING PROPERTY In order to qualify for bonus depreciation, the original use of the property must commence with the taxpayer; in other words, it is new, not used, property. In addition, the definition of qualified property includes the following: x x x x x x Depreciable property with a recovery period of 20 years or less Computer software not subject to Section 197 Water utility property Certain leasehold improvements Certain noncommercial aircraft Certain trees, vines, and fruit-bearing plants when planted or grafted The adjusted basis of the property is reduced by the amount of bonus depreciation for purposes of computing regular MACRS depreciation over the recovery life of the asset. Thus, bonus depreciation DFFHOHUDWHVRWKHUZLVHDOORZDEOHFRVWUHFRYHU\LQWRWKHILUVW\HDURIWKHSURSHUW\·VUHFRYHU\OLIH,QWKHFDVH of 100 percent bonus depreciation, basis is reduced to zero and no unrecovered cost remains to which MACRS would apply. 3-26 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-12 Bonus Depreciation In March 2017, Wallace Inc. acquired and placed in service new tangible personal property with a cost of $700,000. Under MACRS, these assets are five-year recovery property. Without bonus depreciation, Wallaceps cost recovery deduction for 2017 would be $140,000 ($700,000 × 20% first-year MACRS rate for five-year property). With bonus depreciation, WallacepVWRWDO cost recovery for the property is $420,000, computed as follows. Recovery Deductions Initial cost 50% bonus depreciation Adjusted basis for MACRS MACRS percentage for five-year property $ 700,000 (350,000) $ 350,000 × 20.00% MACRS depreciation $ 70,000 Total cost recovery $420,000 Note that the combination of bonus depreciation and MACRS permits Wallace to deduct 60 percent ($420,000 ÷ $700,000) of the asset cost in the year of acquisition. The remaining asset cost will be depreciated under the normal MACRS rules for the remainder of its recovery life. If the property had been acquired in March 2011, the entire $700,000 cost would have been deductible under 100 percent bonus depreciation in 2011. INTERACTION OF SECTION 179 AND BONUS DEPRECIATION If property qualifies both for the Section 179 deduction and 50 percent bonus depreciation, Section 179 is applied first [see Reg. Sec. 1.168(k)-1(d)(1)(i)]. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-27 Example 3-13 Bonus Depreciation and Section 179 Refer back to example 3-12, in which new property was acquired in March 2017. If Wallace elects both Section 179 and 50 percent bonus depreciation for this acquisition, its total 2017 recovery deduction for the asset is $624,000, computed as follows: Recovery Deductions Initial cost $700,000 Section 179 expense (510,000) Adjusted basis for bonus depreciation $190,000 50% bonus depreciation (95,000) Adjusted basis for MACRS $ 95,000 MACRS percentage for five-year property × 20.00% MACRS depreciation $ 19,000 Total cost recovery $624,000 As a result of these incentive provisions, Wallace is able to deduct 89 percent ($624,000 ÷ $700,000) of the cost of the acquisition in 2017. The remaining unrecovered basis of the asset will be depreciated under the normal MACRS rules for the remainder of its recovery life. For qualifying acquisitions placed in service after September 8, 2010, and before January 1, 2012, bonus depreciation alone permits immediate recovery of 100 percent of the cost. For such acquisitions, taxpayers may benefit by foregoing the Section 179 deduction and simply electing bonus depreciation. In particular, bonus depreciation is not subject to the taxable income limitation that applies to Section 179. ELECTING OUT OF BONUS DEPRECIATION Taxpayers may elect out of additional first-year bonus depreciation under Section 168(k)(2)(D)(iii). Such an election applies to all property in the same asset class placed in service in the year of the election. The election is available for qualified assets purchased and placed in service after March 31, 2008, and before January 1, 2020. Taxpayers may choose this election in order to claim additional research or AMT credits under the provisions of Section 168(k)(4). Revenue Procedure 2009-33, 2009-29 IRB 150, provides guidance to corporations regarding the property eligible for this election, the time and manner for making the election, and the computation of the 3-28 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited amount by which the business credit limitation and AMT credit limitation may be increased if the elections provided by Section168(k)(4)(H) are or are not made. To determine whether it is advantageous to make this election, taxpayers should compare the present value of claiming bonus depreciation in the placed-in-service year versus claiming straight-line depreciation over the property's recovery period. They then compare these two options with the benefit of claiming additional AMT and research credits now versus in the future. ,QDGGLWLRQWKHEHQHILWLVOLPLWHGWRWKHOHVVHURIPLOOLRQRUSHUFHQWRIWKHVXPRIWKHWD[SD\HU·V research and AMT credit carryovers from tax years beginning before January 1, 2006. The increased credit amounts allowable are treated as tax overpayments and are refundable to the taxpayer even if no tax is owed. The right choice between bonus depreciation and aGGLWLRQDOFUHGLWVZLOOGHSHQGRQWKHWD[SD\HU·VIDFWV$ taxpayer with credit carryovers in danger of expiring, particularly one currently in a loss position or SD\LQJOLWWOHFXUUHQWWD[OLDELOLW\PD\EHQHILWVLJQLILFDQWO\IURPWKLVFKRLFHE\´FDVKLQJLQµ their unused credits. Rev. Proc. 2008-65 2008-44 IRB 1082 provides detailed guidance on the application of Section 168(k). KNOWLEDGE CHECK 6. For 2017 acquisitions, bonus depreciation in the year of acquisition equals a. b. c. d. 100 percent of the cost of qualified property. 50 percent of the cost of qualified property. 30 percent of the cost of qualified property. Either 30 percent or 50 percent of the cost of qualified property, at the election of the taxpayer. 7. If property qualifies both for the Section 179 deduction and additional first-year bonus depreciation, a. Taxpayers are permitted to choose whether to apply Section 179 first or bonus depreciation first. b. Section 179 is applied first. c. Bonus depreciation is applied first. d. Taxpayers may not take both incentive provisions, but must elect one or the other. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-29 Limitations on Depreciation of Passenger Automobiles and Other Listed Property Section 280F imposes two limits on depreciation allowed for listed property. First, if the property is not used more than 50 percent in a qualified business, the Section 179 election, bonus depreciation, and the GDS system do not apply. Second, annual limitations apply in computing depreciation and Section 179 deductions on certain passenger automobiles. LISTED PROPERTY DEFINED Section 280F(d)(4) defines listed property to include the following items: x x x x Any passenger automobile Any other property used as a means of transportation Any property of a type generally used for entertainment, recreation, or amusement Any computer or peripheral equipment, except when used exclusively at a regular business establishment and owned or leased by the person operating such establishment Passenger automobiles are defined by Section 280F(d)(5) as four-wheeled vehicles manufactured primarily for use on public roads with an unloaded gross vehicle weight of 6,000 pounds or less. Vehicles directly used in the business of transporting people or property for compensation, such as taxicabs, limousines, hearses, ambulances, and delivery vans and trucks are excluded from the definition of passenger automobiles. BUSINESS USE LIMITATION If for a given taxable year the business use percentage of any listed property does not exceed 50 percent, depreciation on such property is computed using ADS [see Section 280F(b)(1)]. If in the year of acquisition, the business use percentage of listed property does not exceed 50 percent, the taxpayer is not entitled to make any election under Section 179 with respect to the property [Reg. Sec. 1.280F-3T(c)]. In addition, because ADS is required, bonus depreciation is not available. When listed property is not used exclusively for business purposes, the actual cost recovery deduction permitted in computing taxable income is based on the percentage of combined business and investment use [see Reg. Sec. 1.280F-6(d)(3)]. This approach ensures that no deduction is permitted for personal use of the property. If the business use percentage of listed property exceeds 50 percent in the year of acquisition but does not exceed 50 percent in any subsequent year, recapture provisions apply under Section 280F(b)(2). Under these recapture rules, the amount of depreciation computed on the property during years in which business use exceeded 50 percent is compared to the amount that would have been allowed had business use not exceeded 50 percent. The excess is included in income in the first year in which business use does not exceed 50 percent. 3-30 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-14 Recapture When Business Use Declines Below 50 Percent In Year 1, James Learner acquired a pickup truck costing $25,000 for use in his landscaping EXVLQHVV7KHWUXFNpVJURVVYHKLFOHZHLJKWLVPRUHWKDQSRXQGVVRLWLVQRWVXEMHFWWRWKH passenger automobile limits. For Year 1 and Year 2, James used the pickup exclusively for business. He claimed a Section 179 deduction of $15,000 on the truck in Year 1, and MACRS GDS depreciation of $2,000 and $3,200 in Year 1 and Year 2, respectively, based on the fiveyear recovery life of the truck. In Year 3, James used the truck 40 percent for business purposes and 60 percent for personal purposes. He must include in his Year 3 income excess depreciation on the truck computed as follows. Total Section 179 deduction and depreciation claimed for years 1 and 2 $20,200 Depreciation allowable under ADS (12-year SL) Year 1 $1,042 Year 2 2,083 Excess depreciation included in Year 3 income (3,125) $17,075 PASSENGER AUTOMOBILE LIMITATIONS The annual depreciation deduction for passenger automobiles may not exceed the limits provided in Section 280F(a) under a special schedule, which is adjusted annually for inflation. The amount deductible in any recovery year varies depending on the year placed in service. For passenger automobiles other than trucks, vans, and electric vehicles, the limitation amounts through 2016 are shown in exhibit 3-7.3 As these materials are being finalized, the 2017 depreciation limitations for passenger automobiles have not been announced. 3 The 2016 amounts were set forth in Rev. Proc. 2016-23, 2016-16 IRB 581. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-31 Exhibit 3-7 Maximum Depreciation Deduction for Passenger Automobiles st Year Placed in Service 1 Recovery Year 2012t2016 $3,160* 2011 2 nd Recovery Year rd th 3 Recovery Year 4 and Later Years $5,100 $3,050 $1,875 3,060* 4,900 2,950 1,775 2010 3,060* 4,900 2,950 1,775 2009 2,960* 4,800 2,850 1,775 2008 2,960* 4,800 2,850 1,775 2007 3,060 4,900 2,850 1,775 2006 2,960 4,800 2,850 1,775 2005 2,960 4,700 2,850 1,675 2004 2,960* 4,800 2,850 1,675 2003 3,060* 4,900 2,950 1,775 2002 3,060* 4,900 2,950 1,775 2001 3,060* 4,900 2,950 1,775 2000 3,060 4,900 2,950 1,775 1999 3,060 5,000 2,950 1,775 1998 3,160 5,000 2,950 1,775 1997 3,160 5,000 3,050 1,775 *This limit is before considering any allowable bonus depreciation. The limit is increased by $4,600 allowable 30 percent bonus depreciation for vehicles placed in service between September 11, 2001, and May 5, 2003. The limit is increased by $7,650 allowable 50 percent bonus depreciation for vehicles placed in service between May 6, 2003, and December 31, 2004, and $8,000 allowable bonus depreciation for vehicles placed in service in 2008 through 2016. The passenger automobile limitations of Section 280F are applied annually, by comparing depreciation computed under MACRS GDS to the maximum deduction amounts for each recovery year as reflected in exhibit 3-7. In tax years following the end of the normal MACRS recovery period, taxpayers continue 3-32 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited WRGHGXFWDQDPRXQWHTXDOWRWKHOHVVHURIWKH´IRXUWKDQGODWHU\HDUVµUHFRYHU\OLPLWDWLRQRUUHPDLQLQJ unrecovered basis (see Section 280F(a)(1)(B)). As previously discussed, qualifying assets placed in service after September 8, 2010, and before January 1, 2012, are eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation. The interaction of the passenger automobile limitations and 100 percent bonus depreciation is addressed in detail in Rev. Proc. 2011-26, 2011-16 IRB 664. The revenue procedures offer two options for determining allowable depreciation for automobiles qualifying for 100 percent bonus depreciation but subject to the passenger automobile limitations. Under the first alternative (considered the general rule), if the cost of the automobile exceeds the first-year automobile limitation amount, no deduction is permitted until the first tax year following the end of the normal MACRS recovery period. Beginning in that tax year, the unrecovered basis is deductible subject WRWKH´IRXUWKDQGODWHU\HDUVµUHFRYHU\OLPLWDWLRQVKRZQLQH[KLELW-7. Revenue Procedure 2011-26 offers taxpayers an elective alternative. Under this election, the taxpayer calculates MACRS depreciation in years after the placed-in-service year as if 50 percent bonus depreciation applied instead of 100 percent bonus depreciation. The election is made by adopting this PHWKRGWRFRPSXWHGHSUHFLDWLRQRQWKHUHWXUQIRUWKHILUVWWD[\HDUIROORZLQJWKHYHKLFOH·VSODFHG-inservice year. The maximum depreciation deductions for light trucks and vans (those with a gross vehicle weight of 6,000 pounds or less) placed in service after 2002 are higher than the limits shown in exhibit 3-7. Exhibit 3-8 defines these higher limits. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-33 Exhibit 3-8 Maximum Depreciation Deduction for Light Trucks and Vans Year Placed in Service st 1 Recovery Year 2 nd Recovery Year rd th 3 Recovery Year 4 and Later Years 2016 $3,560* $5,700 $3,350 $2,075 2015 3,460* 5,600 3,350 1,975 2014 3,460* 5,500 3,350 1,975 2013 3,360* 5,400 3,250 1,975 2012 3,360* 5,300 3,150 1,875 2011 3,260* 5,200 3,150 1,875 2010 3,160* 5,100 3,050 1,875 2009 3,060* 4,900 2,950 1,775 2008 3,260* 5,200 3,150 1,875 2007 3,260 5,200 3,050 1,875 2006 3,260 5,200 3,150 1,875 2005 3,260 5,200 3,150 1,875 2004 3,260* 5,300 3,150 1,875 2003 3,360* 5,400 3,250 1,975 *This limit is before considering any allowable bonus depreciation. The limit is increased by $4,600 allowable 30 percent bonus depreciation for vehicles placed in service between January 1, 2003, and May 5, 2003. The limit is increased by $7,650 allowable 50 percent bonus depreciation for vehicles placed in service between May 6, 2003, and December 31, 2004, and $8,000 allowable bonus depreciation for vehicles placed in service in 2008 through 2016. 2016 amounts are set forth in Revenue Procedure 201623, 2016-16 IRB 581. The maximum depreciation amounts for electric vehicles are higher if such vehicles were placed in service before January 1, 2007. After this date, the maximum depreciation amounts for electric vehicles classified as automobiles are as shown in exhibit 3-7; for electric light trucks and vans, exhibit 3-8 applies for 2007 through 2016 acquisitions. Taxpayers that use passenger automobiles in their business cannot avoid the limitation on depreciation by leasing automobiles rather than purchasing them. Section 280F(c) provides that deductions for lease payments on passenger auWRPRELOHVPXVWEHOLPLWHGLQDPDQQHUWKDWLV´VXEVWDQWLDOO\HTXLYDOHQWµWRWKH depreciation limitation. Treasury Regulations under Section 280F and IRS Publication 463, Travel, 3-34 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Entertainment, Gift, and Car Expenses, include the complicated procedure by which taxpayers compute their limited deduction for lease payments on passenger automobiles. KNOWLEDGE CHECK 8. Under the listed property limitations, passenger automobiles a. b. c. d. Are depreciable under the normal MACRS rules. Must be depreciated using ADS. Are subject to annual limits on deductible depreciation. Are not depreciable. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-35 Depreciation of Property Acquired in a Like-Kind Exchange or Involuntary Conversion The adjusted tax basis of property acquired in a like-kind exchange or involuntary conversion is a substituted basis, computed with reference to the basis of property surrendered as part of the nontaxable exchange. In effect, the substituted basis rules require the taxpayer to treat the new property as a substitute for the old. Consistent with this approach, depreciation of the replacement property is also based, in whole or in part, on the manner in which the surrendered property was depreciated prior to its disposition. Reg. Sec. 1.168(i)-6 provides detailed guidance on the depreciation of property acquired in a like-kind exchange or involuntary conversion. These regulations focus on exchanges in which depreciable property subject to the MACRS is replaced with other property subject to MACRS. Depreciable property disposed of in a qualified transaction is permitted the normal MACRS cost recovery for the year of disposition, in accordance with Reg. Sec. 1.168(i)-6(c)(5)(i)(A). Example 3-15 Depreciation in Year of Disposition In August of Year 4, Asset A owned by Stark LLC was destroyed in a fire. Asset A was seven-year MACRS recovery property. In September of tax Year 4, Stark replaced Asset A with Asset B, also qualifying as seven-year MACRS recovery property. Asset A was acquired in Year 1 for $200,000, subject to the half-year convention, and depreciated under the general depreciation system (GDS) of MACRS. Accumulated depreciation on Asset A at the end of Year 3 (the year prior to the conversion) was $112,540. Allowable MACRS depreciation on Asset A for Year 4, the year of the exchange, is $12,490, computed as follows: Original cost $200,000 Year 4 MACRS recovery percentage × Full-year MACRS depreciation $ 24,980 Half-year convention × Allowable MACRS cost recovery for year of disposition $ 12,490 12.49% 50% In depreciating property acquired in a like-kind exchange or involuntary conversion, Reg. Sec. 1.168(i)-6 distinguishes between exchanged basis and excess basis. Exchanged basis is defined in Reg. Sec. 1.168(i)6(b)(7) as the lesser of the adjusted basis of the replacement property immediately after the exchange or the adjusted basis of the relinquished property at the date of the exchange. Excess basis is the excess of the adjusted basis of the replacement property immediately after the exchange over the exchanged basis. 3-36 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-16 Exchanged and Excess Basis Refer back to example 3-15. The adjusted basis of Asset A at the date of the involuntary conversion was $74,970 ($200,000 cost t $112,540 accumulated depreciation through Year 3 t $12,490 depreciation allowed in Year 4). Stark received $80,000 in insurance proceeds, realizing a gain of $5,030. It elected to defer the gain under Section 1033, and reinvested the $80,000 insurance proceeds plus $6,000 of additional funds in replacement Asset B. 6WDUNpVEDVLVLQUHSODFHPHQW$VVHW%LV FRVWt $5,030 deferred gain). Of this amount, $74,970 is exchanged basis and $6,000 is excess basis. With regard to exchanged basis, if the relinquished asset and the replacement asset are subject to the same MACRS recovery life and method, the taxpayer continues to depreciate the replacement asset over the remaining recovery life of the relinquished asset. If the replacement asset has a shorter recovery period, or is subject to a more-accelerated depreciation method than the relinquished asset, the taxpayer depreciates the exchanged basis of the replacement asset over the remaining recovery life of the relinquished asset using the recovery method applicable to the relinquished asset. In effect, in these circumstances cost recovery of the exchanged basis continues as though the taxpayer still owned the relinquished asset [see Reg. Sec. 1. 168(i)-6(c)]. Example 3-17 Depreciation of Exchanged Basis Refer back to examples 3-15 and 3-16. Asset A was seven-year recovery property depreciated using the MACRS GDS. At the time of the conversion, it was in the fourth year of its recovery life. As shown in the following example, Stark was entitled to a half-year of depreciation on Asset A in the year of the conversion. The $74,970 exchanged basis of Asset B will be depreciated over the remaining 4½ years of $VVHW$pVUHFRYHU\OLIHDVIROORZV Year MACRS Recovery Year 4 Year 4 (half-year convention) 5 Recovery Percentage Cost Recovery 12.49% × 50% $12,490 Year 5 8.93% 17,860 6 Year 6 8.92% 17,840 7 Year 7 8.93% 17,860 8 Year 8 4.46% 8,920 $74,970 Cost recovery for Asset B is computed using the applicable recovery percentages applied to $VVHW$pVFRVWRIQRWWKHH[FKDQJHGEDVLVRI$VVHW%LVHOLJLEOHIRUWKHKDOIyear convention in the year of acquisition. Note that by the end of Year 8, the final year of Asset $pVRULJLQDOUHFRYHU\OLIHWKHH[FKDQJHEDVLVRIDVVHW%LVIXOO\GHSUHFLDWHG Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-37 If the replacement asset has a longer recovery period, or is subject to a less-accelerated depreciation method than the relinquished asset, the taxpayer depreciates the exchanged basis of the replacement asset over the remaining portion of its longer recovery life, using the less- accelerated recovery method applicable to the replacement asset [see Reg. Sec. 1. 168(i)-6(c)]. The remaining portion of the recovery OLIHLVGHWHUPLQHGE\UHGXFLQJWKHUHSODFHPHQWDVVHW·VDOORZDEOHUHFRYHU\OLIHE\WKHSHULRGRYHUZKLFKWKH relinquished property was depreciated. Reg. Sec. 1.168(i)-6(d) treats excess basis in the replacement property as property placed in service in the year of the replacement. Thus, excess basis is recovered over the MACRS recovery life of the replacement property, using the applicable MACRS convention and recovery method. Example 3-18 Depreciation of Excess Basis Refer back to examples 3-15, 3-16, and 3-176WDUNpVH[FHVVEDVLVLQ$VVHW%LV7KH excess basis is seven-year MACRS recovery property depreciable beginning in Year 5, subject to the half-year convention. Cost recovery deductions allowable for this excess basis are computed as follows: Year MACRS Recovery Year Recovery Percentage Cost Recovery 4 Year 1 14.29% 5 Year 2 24.49 1,469 6 Year 3 17.49 1,049 7 Year 4 12.49 749 8 Year 5 8.93 536 9 Year 6 8.92 535 10 Year 7 8.93 536 11 Year 8 4.46 269 $ 857 $6,000 Note that even though the exchanged basis of Asset B will be fully depreciated in Year 8, per example 3-17, the excess basis will continue to be depreciated until Year 11. Under Reg. Sec. 1.168(i)-6(i), a taxpayer may elect not to apply this section for any MACRS property involved in a like-kind exchange or involuntary conversion. If the election is made, the sum of the exchanged basis and excess basis, if any, in the replacement property is treated as property placed in service by the taxpayer at the time of replacement. 3-38 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited The examples presented previously assume that the replacement property is not eligible for either the Section 179 deduction or additional first-year bonus depreciation under Section 168(k). For replacement property otherwise qualifying under these sections, the Section 179 deduction is permitted only with respect to excess basis [see Reg. Sec. 1.168(i)-6(g)]. However, additional first-year bonus depreciation may be claimed for the entire depreciable basis of qualified replacement property, under Reg. Sec. 1.168(k)1(f)(5). If property is eligible for both Section 179 and additional first-year bonus depreciation, Reg. Sec. 1.168(k)-1(d)(1)(i) provides that Section 179 is applied first. KNOWLEDGE CHECK 9. The __________ basis of replacement property acquired in a like-kind exchange or involuntary conversion is depreciated over its MACRS recovery life, beginning in the year of the replacement. a. b. c. d. Initial Excess. Exchanged. Substituted. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3-39 3-40 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Chapter 4 INTANGIBLE ASSETS AND AMORTIZATION LEARNING OBJECTIVES After completing this chapter, you should be able to do the following: x x x x x Identify common amortizable intangibles. Recognize the types of purchased intangible costs that must be capitalized. Distinguish how to allocate purchase price to intangible assets under the residual method. Recall how to depreciate improvements to leased tangible property. Identify self-created intangibles that must be capitalized. INTRODUCTION Businesses often own a variety of assets that have no physical substance but represent a valuable property right or economic attribute. Intangible assets may be purchased by the business, either independently or as part of a larger asset acquisition. Alternatively, intangible assets may be created by the efforts of the business, with appropriate legal steps taken to secure and protect the created rights. Other intangibles arise in the process of creating a new business or forming a new legal entity to conduct that business. This chapter explores the transactions resulting in intangible assets, the issues surrounding the tax basis of such assets, and the cost recovery methods permitted for tax purposes for deducting capitalized costs of intangibles. It also discusses the requirements for tax amortization of intangibles. We distinguish between self-created intangibles and those acquired by purchase. In the purchase context, we discuss Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-1 both independent purchases of intangibles and those acquired as part of the purchase of an ongoing business. When the purchase of a business occurs, issues surrounding the allocation of purchase price will affect the cost basis of acquired intangibles. This chapter briefly describes the residual method of purchase price allocation and the resulting tax basis in intangible assets including goodwill. Finally, it discusses capitalization and cost recovery rules applicable to start-up and organization costs. The tax basis in intangible assets may be recoverable under some amortization method allowed for tax purposes. As a general rule under Regulation Section 1.167(a)-3, amortization is permitted only if the intangible asset has a determinable life. For instance, a firm that purchases a patent or copyright can deduct the cost ratably over the number of months during which the patent or copyright confers an exclusive legal right on the owner [Reg. Secs. 1.197-2(c)(7) and 1.167(a)-14(c)(4)]. The cost basis in an intangible asset with an indeterminable life generally is not amortizable but can be recovered only upon disposition of the asset. However, certain exceptions exist to this rule, as discussed in the following section. The tax law contains a number of amortization provisions that do not relate to intangible assets. For example, Section 169 provides for amortization of certified pollution control facilities; Section 190 provides for amortization of costs of removing barriers to handicapped access; and Section 194 provides for amortization of reforestation expenditures. These amortization provisions are not discussed in this chapter, which focuses specifically on intangibles. 4-2 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Intangibles Capitalization TAX BASIS OF ACQUIRED INTANGIBLES In rules that contained major departures from prior positions, the IRS issued final regulations on the capitalization requirements for intangible assets [Reg. Secs. 1.263(a)-4, 1.263(a)-5, and 1.446-5, and amendments of Reg. Sec. 1.167(a)-3, T.D. 9107, 12/31/2003]. As a general principle, the regulations require the capitalization of the acquisition, creation, or enhancement of an intangible asset. This definition applies to any intangible acquired from another in a purchase transaction, certain rights, privileges and benefits created by the taxpayer, separate and distinct intangible assets, and items producing a distinct future benefit. Under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(c), a taxpayer must capitalize amounts paid to another party to acquire any intangible in a purchase or similar transaction. Examples of acquired intangibles subject to this rule include the following: x x x x x x x x An ownership interest in a corporation, partnership, trust, estate, limited liability company, or other entity A debt instrument or other financial instrument A lease A patent, copyright, franchise, trademark, or trade name An assembled workforce A customer list Customer-based or supplier-based intangibles Goodwill or going concern value In addition to the direct purchase price of the intangible, the taxpayer must capitalize any amount paid to facilitate the acquisition or creation of an intangible, as defined in Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(e), including amounts paid in the process of investigating the acquisition. Such capitalized transaction costs include appraisal costs, payments to outside legal counsel assisting in the negotiation of the acquisition or preparing contracts, and payments to accountants or other consultants assisting in establishing the value of the intangible or negotiating its acquisition. Example 4-1 Acquired Intangible Advance Inc. wished to acquire a trademark from Lux Corporation to use in producing specialty cosmetics. Prior to the purchase, it hired an outside market consulting firm at a cost of $20,000 to develop projections of the future revenue stream associated with the trademarked products. It also paid outside legal counsel $10,000 to prepare the purchase contract and assist in purchase negotiations. Advance paid Lux $150,000 for the trademark. The total capitalized cost of the acquired intangible is $180,000 ($150,000 purchase price + $20,000 consulting firm fee + $10,000 outside legal fees). Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-3 In an important simplification of the transaction cost capitalization rule, employee compensation, overhead, and de minimis costs are not capitalized as amounts that facilitate the acquisition or creation of an intangible. For this purpose, costs that do not exceed $5,000 are considered de minimis. See Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(e)(4). ALLOCATION OF LUMP SUM PURCHASE PRICE Intangible assets are often acquired as part of the acquisition of the assets of an ongoing business. In that case, acquisition cost of the group of assets must somehow be allocated among the items acquired, in order to determine allowable cost recovery including amortization of acquired intangibles. The allocation of a lump sum purchase price to the acquired assets of an existing business is determined under Section 1060. The regulations under Section 1060 divide all assets into seven classes, as follows: x x x x x x x Class I: Cash and cash equivalents Class II: Marketable securities, certificates of deposit, and foreign currency Class III: Accounts receivable, mortgage receivables, and credit card receivables Class IV: Inventory and stock in trade Class V: All other tangible assets Class VI: Identifiable intangible assets other than goodwill and going concern value Class VII: Goodwill and going concern value The allocation of purchase price to these assets uses the residual method, beginning with Class I and continuing on through each class up through Class VI. Any purchase price not allocated to assets in Classes I through VI (the residual), is allocated to Class VII, goodwill. Total consideration paid by the purchaser is allocated first to Class I assets based on their aggregate fair market value, then to Class II assets, and so on. Within each class, purchase price is allocated to each asset equal to (but not greater than) fair market value. Under this method, any premium paid by the purchaser in excess of the fair market value of tangible and identifiable intangible assets is treated as goodwill rather than allocated proportionately among the other assets. Under Section 1060 (with reference to Reg. Sec. 1.338-6 and Section 197), the following acquired intangibles are included in Class VI: x x x x x x Workforce in place Business books and records, operating systems, or any other information base including customer lists Patents, copyrights, formulas, processes, designs, know-how, formats, franchises, trademarks, trade names, or other similar items Customer-based and supplier-based intangibles Licenses, permits, or other rights granted by governmental units or agencies A covenant not to compete To the extent such Class VI intangibles are identifiable and can be separately valued, purchase price allocated to this class is then allocated among these assets based on relative value. Any residual purchase price is then classified as goodwill or going concern value. 4-4 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 4-2 Lump-Sum Purchase of Business Assets Jones Inc. has offered to purchase the business of Smith for $2 million. Included in the deal is an agreement by the owner or employees of Smith to refrain from starting a competing business within the five-VWDWHDUHDVXUURXQGLQJ6PLWKpVKHDGTXDUWHUVIRUDSHULRGRIWHQ\HDUV 7KHIROORZLQJWDEOHLGHQWLILHVWKHYDOXHRI6PLWKpVDVVHWVFODVVLILHGLQDFFRUGDQFHZLWK6ection 1060, including several identifiable intangibles. Asset and Class Fair Market Value Class I Cash $ 25,000 Class III Accounts receivable 240,000 Class V Furniture Computer equipment 50,000 150,000 Class VI Workforce in place 400,000 Customer lists 450,000 Information system 200,000 Covenant not to compete 350,000 Total $ 1,865,000 7KHWRWDOYDOXHRI6PLWKpVLGHQWLILDEOHDVVHWVLQ&ODVVHV,WKURXJK9,LV7KHUHVLGXDO purchase price of $135,000 ($2 million t $1,865,000) is allocated to goodwill. FACILITATIVE COSTS FOR BUSINESS ACQUISITIONS AND CAPITAL STRUCTURE CHANGES Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-5 contains rules requiring taxpayers to capitalize amounts paid to facilitate the acquisition of a business, a change in the capital structure of a business entity, and other similar transactions. Under these regulations, a taxpayer must capitalize an amount paid to facilitate each of the following transactions, without regard to whether gain or loss is recognized in the transaction: x x x An acquisition of assets that constitutes a business, whether the taxpayer is the acquirer or the target of the acquisition. An acquisition by the taxpayer of an ownership interest in a business entity if, immediately after the acquisition, the taxpayer and the business entity are related within the meaning of Section 267(b) or Section 707(b). An acquisition of an ownership interest in the taxpayer (other than an acquisition by the taxpayer of an ownership interest in the taxpayer, such as by a redemption). Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-5 x x x x x x x A restructuring, recapitalization, or reorganization of the capital structure of a business entity. A transfer such as a formation of a corporation under Section 351 or a Section 721 partnership formation. A formation or organization of a disregarded entity. An acquisition of capital. Stock issuance. A borrowing transaction, such as an issuance of debt. Writing an option [Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-5(a)]. Observation: These final regulations provide a single set of rules for amounts paid to facilitate an acquisition of a business, regardless of whether the transaction is structured as an acquisition of the entity or as an acquisition of assets constituting a business. The regulations also contain a number of important exceptions, under which capitalization is not required for costs that facilitate an acquisition or a capital restructuring: x x x x De minimis amounts paid in the process of investigating or otherwise pursuing a capitalizable transaction may be expensed if the amounts do not exceed $5,000 [Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-5(d)(3)]. Employee compensation and overhead are not considered capitalizable costs that facilitate a transaction [Reg. Sec. 263(a)-5(d)(1)]. An amount paid to integrate the business operations of the taxpayer with the business operations of another entity does not require capitalization [Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-5(c)(6)]. 7KHUHJXODWLRQVFRQWDLQD´EULJKWOLQHGDWHµUXOHXQGHUZKLFKH[SHQGLWXUHVWRIDFLOLWDWHDQDFTXLVLWLRQ (a taxable acquisition of assets that constitutes a business, a taxable acquisition of an ownership interest in a business, or a reorganization) are capitalizable only if the amount relates to activities performed on or after the earlier of a. the date on which a letter of intent or similar written communication is executed by the representatives of the acquirer and the target or b. the date on which the material terms of the transaction are authorized or approved by the governing officials of the taxpayer. While this exception allows preliminary and preacquisition cost to be deductible, it is not applicable to transactions categorized as ´LQKHUHQWO\IDFLOLWDWLYHDPRXQWVµ Observation: ´,QKHUHQWO\IDFLOLWDWLYHDPRXQWVµDUHGHILQHGLQWKHUHJXODWLRQVDVFRVWVWKDWDUHFDSLWDO regardless of when incurred in connection with an acquisition or reorganization. Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-5(e)(2) defines six categories of these expenses that must always be capitalized: 1. Securing an appraisal, formal written evaluation, or fairness opinion related to the transaction. 2. Structuring the transaction, including negotiating the structure and obtaining tax advice on the structure of the transaction. 3. Preparing and reviewing the documents that accomplish the transaction. 4. Obtaining regulatory approval, including preparing and reviewing regulatory filings. 5. Obtaining shareholder approval of the transaction. 6. Conveying property between the parties to the transaction. 4-6 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 4-3 Employee Bonus and Integration Costs in Connection With a Corporate Acquisition R Corp pays a bonus of $10,000 to one of its corporate officers who negotiated a business acquisition transaction. R Corp is not required to capitalize this employee compensation. Before and after this acquisition was accomplished, R Corp incurs costs to relocate personnel and equipment, provide severance benefits to terminated employees, integrate records and information systems, prepare new financial statements for the combined entity, and eliminate inefficiencies in the combined business operations. R Corp is not required to capitalize any of these integration costs. Example 4-4 Various Acquisition and Borrowing Fees Z Corp pays $1 million to an investment banker to evaluate four alternative transactions ($250,000 for each alternative): an initial public offering, a borrowing of funds, an acquisition by Z Corp of a competitor, and an acquisition of Z Corp by a competitor. Z Corp eventually decides to pursue the borrowing and abandons the other options. The $250,000 payment for the borrowing transaction is capitalized, and is amortized under Reg. Sec. 1.446-5 relating to debt issuance costs. The other $750,000 of various fees must be capitalized until each of those transactions is abandoned, at which time a loss is allowed under Section 165. Note: The preamble to the final regulations, as well as examples within the regulations, make it clear that fees incurred to defend against a hostile takeover are not required to be capitalized. Similarly, fees paid to ORFDWHDSRWHQWLDO´ZKLWHNQLJKWµDFTXLUHUDUHWUHDWHGDVGHIHQVHFRVWVWKDWDUHQRWUHTXLUHGWREH capitalized. Success Based Fees in Reorganizations Revenue Procedure 2011-29 2011-18 IRB 746 provides the mechanism for a safe harbor election for allocating success-based fees paid in business acquisitions or reorganizations per Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-5(e)(3). Under the safe harbor, electing taxpayers treat 70 percent of the success-based fee as an amount that does not facilitate the transaction and the remaining portion of the fee is capitalized as an amount that facilitates the transaction. EMPLOYEE COMPENSATION TO ACQUIRE INTANGIBLES Employee compensation and overhead amounts, including bonuses and commissions, are not considered as facilitating the acquisition, creation, or enhancement of an intangible asset, regardless of the percentage of the time of the employee allocable to the transaction, and thus are not required to be capitalized [Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(e)(4)]. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-7 Example 4-5 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(e)(5), Example 8 Employee Compensation for Intangible Asset Acquisition P, a commercial bank, maintains a loan acquisition department whose only function is to acquire loans from other financial institutions. P is not required to capitalize any portion of the compensation paid to the employees in its loan acquisition department or any other portion of its overhead allocable to the loan acquisition department. CREATED INTANGIBLES Except as provided under the 12-month rule discussed in the following section, a taxpayer must capitalize amounts paid to create an intangible [Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(d)]. The regulations identify eight categories of created intangibles requiring capitalization: 1. Financial interests³A taxpayer must capitalize amounts paid to create an ownership interest in an entity such as a corporation, partnership, trust or LLC, a debt instrument, financial contract or option or other such agreement for the right or obligation to provide property. Example 4-6 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(d)(2)(vi), Examples 5 and 6 Customer Payments P Corp pays a customer PLOOLRQLQH[FKDQJHIRUWKHFXVWRPHUpVDJUHHPHQWWRSXUFKDVH XQLWVRI3&RUSpVSURGXFWDWDQ\WLPHZLWKLQWKHVXFFHHGLQJFDOHQGDU\HDUV7KH agreement with the customer describes this amount as a sales discount. This payment is an amount paid to induce the customer to enter into an agreement providing P Corp the right to provide property, and it must be capitalized. On the other hand, if P Corp entered into an agreement with a customer under which P Corp agreed to make a payment of $1 million to a customer on the date on which the customer had completed the purchase of 1,000 units of P Corp property over a defined period of time, P Corp would not be required to capitalize its payment because the payment does not provide P Corp with the right or obligation to provide property and does not create a separate and distinct intangible asset. 2. Prepaid expenses³A taxpayer must capitalize prepaid expenses. Examples in the regulations include an DFFUXDOPHWKRGWD[SD\HU·VSD\PHQWRIWRDQLQVXUHUIRUWKUHH\HDUVRISURSHUW\DQGFDVXDOW\ FRYHUDJHDQGDFDVKPHWKRGWD[SD\HU·VSUHSD\PHQWRIUHQWRQD-month lease. 4-8 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3. Memberships and privileges³A taxpayer must capitalize amounts paid to obtain, renew, or upgrade a membership or privilege from an organization, but is not required to capitalize amounts paid to obtain, renew, or upgrade certification of the WD[SD\HU·VSURGXFWVVHUYLFHVRUEXVLQHVVSURFHVVHV Example 4-7 Capitalized Membership Fee Y Corp pays a $50,000 initiation fee to obtain membership in a trade association. This fee must be capitalized. Example 4-8 Business Product Rating V Corp pays a national quality ratings association $100,000 to conduct a study and provide DUDWLQJRIWKHTXDOLW\DQGVDIHW\RID9&RUSSURGXFW9&RUSpVSD\PHQWLVWRREWDLQD certification and is not required to be capitalized. Similarly, if V Corp obtained an ISO 9000 certification, payments would not be required to be capitalized. 4. Government rights³A taxpayer must capitalize amounts paid to a governmental agency to obtain, renew, or upgrade rights under a trademark, trade name, copyright, license, permit, franchise, or other similar right granted by that agency. 5. Contract rights³A taxpayer is required to capitalize amounts paid to another party to create, originate, enter into, renew, or renegotiate an agreement providing the taxpayer the right to use tangible or intangible property or the right to be compensated for the use of such property, an agreement providing the taxpayer the right to provide or to receive services, a covenant to compete, an agreement not to acquire additional ownership interests in the taxpayer, or an agreement providing the taxpayer with an annuity, endowment or insurance coverage [Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(d)(6)]. However, an amount paid to another party with the mere hope or expectation for developing or maintaining a business relationship is not subject to capitalization. Also, an agreement does not provide a taxpayer with the right to use property or to provide or receive services if the agreement may be terminated at will by the other party before the end of its term. An agreement is not terminable at will if the other party is economically compelled not to terminate the agreement. An agreement that merely provides that a taxpayer will stand ready to provide services if requested, but places no obligation, is not subject to capitalization. Also, a taxpayer is not required to capitalize amounts paid to another party if the aggregate of all amounts paid with respect to the agreement does not exceed $5,000. Example 4-9 Modification of Lease Agreement P Corp leases a piece of equipment. When the lease has three years remaining, P Corp pays $50,000 to the lessor to extend the lease term by five years. Because the payment is a contract right intangible that exceeds $5,000, P Corp must capitalize the payment. Note: Under Reg. Sec. 1.162-11, the payment is amortized over the lease term. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-9 Example 4-10 $5,000 De Minimis Exception X is a wireless telecommunications provider. To induce a customer to enter into a three-year contract, X provides a free wireless telephone. The fair market value of the telephone is $300. Although this is a payment to induce a customer to enter into a service agreement, the amount is de minimis (in other words, under the $5,000 rule), and X is not required to capitalize the payment. 6. Contract terminations³A taxpayer must capitalize amounts paid to another party to terminate a lease, an agreement that grants the party the right to acquire or use property or services or to conduct business, or an agreement that prohibits the taxpayer from competing. However, break-up fees are addressed under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-5, discussed previously, and are deductible if the payment does not facilitate an acquisition. 7. Real property improvements³A taxpayer must capitalize amounts paid for real property if the taxpayer transfers the ownership to another party (other than a sale at fair market value) and if the real property can be expected to produce significant economic benefits to the taxpayer after the transfer. A taxpayer also must capitalize amounts paid to produce or improve real property owned by another if the real property can reasonably be expected to produce significant economic benefits for the taxpayer. Example 4-11 Amount Paid for Real Property Owned by Another L Corp operates a quarry, and finds that an existing bridge between its quarry and crush plant is inadequate to support its trucks in transferring stone. As a result, L Corp contributes $1 million to City N to defray part of the cost of constructing a publicly owned bridge capable of accommodating its trucks. This payment is an amount to improve real property owned by another that can reasonably be expected to produce significant economic benefits to L Corp, and accordingly it must capitalize the payment. 8. Defense or perfection of title to intangibles³A taxpayer must capitalize amounts paid to another party to defend or perfect title to intangible property. For example, if a taxpayer incurs costs in defense of a lawsuit to retain or perfect title to its patent, the cost must be capitalized. 4-10 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited KNOWLEDGE CHECK 1. The capitalized cost of acquired intangibles includes a. b. c. d. Only the direct purchase price of the intangible. Any amount paid to facilitate the acquisition of an intangible. An allocable portion of employee compensation. An allocable SRUWLRQRIWKHDFTXLUHU·VRYHUKHDGFRVWV 2. The residual method of allocating purchase price in a lump-sum purchase of business assets allocates residual value a. b. c. d. Proportionately to identifiable tangible and intangible assets. Proportionately to all tangible assets. Proportionately to all intangible assets. To goodwill and going concern value. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-11 Amortization TREATMENT OF CAPITALIZED INTANGIBLES The final regulations hold that an amount required to be capitalized is not currently deductible, but instead is added to the basis of the intangible acquired or created [Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(g)]. In many cases, existing law will direct the consequences of this capitalization. For example, goodwill and many other LQWDQJLEOHVDUHDPRUWL]DEOHRYHU\HDUV>6HFWLRQ D @6LPLODUO\DWHQDQW·VFRVWVWRDFTXLUHDOHDVHDUH amortizable over the term of the lease [Reg. Sec. 1.162-11(a)]. 15-Year Amortization The final regulations provide a safe harbor amortization period of 15 years for intangible assets [Reg. Sec. 1.167(a)-3(b)]. A capitalized intangible asset will be treated as having an amortizable life of 15 years, other than where the following occur: 1. Amortization of the intangible is specifically prohibited by the tax law or regulations or other published guidance. 2. The intangible is one acquired from another party in a purchase or similar transaction that is capitalizable under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(c) or is a created intangible in the form of a financial interest, such as an ownership interest in a corporation, partnership, or LLC; a debt instrument, or other financial instrument such as a letter of credit, option, or annuity; or insurance contract under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(d)(2). 3. The intangible asset has a useful life that can be estimated with reasonable accuracy. 4. Amounts are capitalized under Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-5, relating to payments to facilitate the acquisition of a business or the acquisition of an entity or a change in the capital structure of an entity [Reg. Sec. 1.167(a)-3(b)]. 25-Year Amortization With respect to capitalization of amounts related to real property owned by another taxpayer, a special 25-year depreciable term is provided. [See preceding example 4-11 for an illustration of such a capitalized intangible as required by Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(d)(8).] Note: Both the 15-year safe harbor amortization and the 25-year real estate intangible asset depreciation are calculated without regard to salvage value and by claiming the deduction ratably over the useful life beginning on the first day of the month in which the intangible asset is placed in service [Reg. Sec. 1.167(a)-3(b)(3)]. These provisions apply to intangible assets created on or after December 31, 2003. Section 197 Intangibles Section 197 intangibles include all those listed previously as Class VI under Section 1060 and goodwill and going concern value. Section 197 intangibles do not include the following: x x x A financial interest in a corporation, partnership, trust, or estate A futures contract, foreign currency contract, notional principal contract, or other similar financial contract Land 4-12 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited x x x x Certain computer software Certain intangibles not acquired as part of the acquisition of the assets of an existing business, including ² Interests in a film, sound recording, video tape, book, or similar property ² Government contract rights ² Patents and copyrights ² Contract rights with a fixed duration of 15 years or fewer Interests under existing leases of tangible property Most debt instruments Note that the list of Section 197 intangibles includes many such assets that could be self-created. Section 197(c)(2) excludes from the amortization rules of Section 197 self-created patents, copyrights, and other know-how intangibles. Such assets are amortizable only under the rules discussed as follows for created intangibles. Example 4-12 Amortization of Section 197 Intangibles Refer back to example 4--RQHV,QFWKHSXUFKDVHURI6PLWKpVEXVLQHVVZLOOEHHQWLWOHGWR amortize the following Section 197 intangibles over 15 years, beginning in the month of the acquisition. Asset Allocated Cost Monthly Amortization $400,000 $2,222 Customer lists 450,000 2,500 Information system 200,000 1,111 Covenant not to compete 350,000 1,944 Goodwill 135,000 750 Workforce in place The arbitrary, 15-year amortization period of Section 197 is imposed regardless of the actual or expected economic life of the intangible. For example, if patents and copyrights are acquired as part of the purchase of an existing business, the purchaser must amortize the cost allocated to the patent or copyright over 15 years, regardless of the remaining legal life of the asset. However, this same rule benefits taxpayers in many instances by allowing amortization of assets, such as goodwill, without a readily ascertainable life. Prior to the enactment of Section 197, the IRS routinely argued that goodwill was not amortizable. If an intangible acquired as part of the acquisition of an existing business is disposed of or becomes worthless, Section 197(f) provides that no loss is recognized as a result of such disposition or worthlessness. Instead, the remaining basis of the subject intangible is reallocated to other intangibles acquired in the transaction. In particular, no loss is allowed with respect to a covenant not to compete until the entire interest in the acquired business with which the covenant relates is disposed of. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-13 Example 4-13 Amortization Period Versus Legal Life Refer back to examples 4-2 and 4-12. Recall that the covenant not to compete prevents the owner or employees of Smith from starting a competing business within the five-state area VXUURXQGLQJ6PLWKpVKHDGTXDUWHUVIRUDSHULRGRI0 years. Even though this intangible has a stated legal life of 10 years, it is amortized over 15 years under Section 197. No loss is permitted for the unamortized balance of the intangible in the year in which the covenant expires. Leasehold Costs When a taxpayer rents tangible property for use in its business, it may incur upfront costs to acquire the lease on the property. Such leasehold costs must be capitalized and amortized over the term of the lease [Reg. Sec. 1.162-11(a)]. In contrast, if a taxpayer pays for physical improvements to leased property, the cost of the leasehold improvements must be capitalized to an asset account, assigned to a MACRS recovery period, and depreciated under the MACRS rules. This cost recovery rule applies even when the term of the lease is shorter than the MACRS recovery period [Section 168(i)(8)]. Example 4-14 Lease Acquisition Costs Early in the year, Veto Corporation entered into a lease agreement for commercial office space. 9HWRpVFRVWRIQHJRWLDWLQJWKHOHDVHZDV $3,120, and it also spent $28,000 to construct cabinets, bookshelves, and lighting fixtures to conform the leased space to its needs. The term of the lease is 48 months, beginning on May 1. Veto must capitalize the $3,120 lease acquisition cost and amortize it over 48 months ($65 per month for a current-year amortization deduction of $520). It must also capitalize the $28,000 cost of the leasehold improvements. These improvements qualify as seven-year recovery property, and Veto will recover its cost basis through MACRS depreciation. Unless Veto renews its lease on the office space after 48 months, it will not have recovered its entire cost basis in the leasehold improvements when it surrenders the space back to the lessor. It will be entitled to a deduction for the unrecovered basis in the leasehold improvements at that time. $5,000 De Minimis Rule Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(d)(6), issued in early 2004, has clarified that a taxpayer must capitalize amounts paid to another party in connection with a contractual right for the use of property (lease acquisition costs). However, this regulation contains an important de minimis exception, holding that a taxpayer is not required to capitalize amounts that do not exceed $5,000. 4-14 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited KNOWLEDGE CHECK 3. Which acquired intangibles are amortizable under Section 197? a. b. c. d. Self-created goodwill. Customer lists. Foreign currency contracts. Land. 4. Costs associated with a covenant not to compete acquired as part of the acquisition of an ongoing business a. b. c. d. May be amortized over the shorter of its legal duration or 15 years. Are amortizable over 15 years. Cannot be amortized. Are immediately deductible. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-15 Organizational and Start-Up Costs Sections 248 and 709 address the tax treatment of the organizational costs of forming a corporation or partnership. Organization costs are defined as expenditures which are (1) incident to the creation of the corporation or partnership, (2) chargeable to a capital account, and (3) of a character which, if expended to create an entity with a limited life, would be amortizable over that life [Sections 248(b) and 709(b)]. Examples of organization costs include legal and accounting fees attributable to the formation and any filing or registration fees required under state or local law. A new partnership or corporation can deduct the lesser of its actual organizational costs or $5,000 in the taxable year in which it begins business. This $5,000 maximum is reduced by the amount by which total costs exceed $50,000. The entity must capitalize any nondeductible organizational costs and may elect to amortize such costs over a 180-month period starting with the month in which business begins. Section 195 provides a similar rule for the start-up expenditures of any new business, regardless of organizational form. Start-up expenditures include both the upfront costs of investigating the creation or purchase of a business and the routine expenses incurred during the preoperating phase of a business. This preoperating phase ends only when the business has matured to the point that it can generate revenues. A firm may deduct the lesser of its actual start-up expenditures or $5,000. This $5,000 maximum is reduced by the amount by which total expenditures exceed $50,000. The firm must capitalize any nondeductible start-up expenditures and may elect to amortize such costs over a 180-month period starting with the month in which business begins. According to Section 195(c)(1), interest expense, taxes, and research and experimentation costs are not start-up expenditures and may be deducted even if incurred during the preoperating phase of a business venture. The IRS has clarified that expenditures incurred in the course of a general search or investigation to determine whether to enter a new business and which new business to enter qualify as start-up or investigatory costs eligible for amortization under Section 195. However, expenditures incurred in the attempt to acquire a specific business do not qualify because they are considered capital acquisition costs under Section 263. Thus, as a taxpayer considers entry into a particular industry or type of business activity, the costs are eligible for Section 195 amortization, but upon identifying a target business to acquire, the costs of investigation and due diligence are capital to the acquisition of that particular business (Revenue Ruling. 99-23, 1999-1 CB 998; PLR 9825005; Preamble to Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4, T.D. 9107). Example 4-15 Start-Up Costs Ginger Corporation incurred total start-up costs of $50,000. It can elect to deduct $5,000 of this amount. The remaining $45,000 is amortized over 180 months beginning the month in which business begins. ,I*LQJHUpVWRWDOVWDUW-up costs were $52,000, the $5,000 deductible amount is reduced by the excess of total start-up costs more than $50,000. Ginger can deduct $3,000 of its start-up cost and amortize the remaining $49,000 over 180 months. 4-16 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 4-16 Organization Costs Mr. Adams and Mrs. Bonner agreed to start a new business in the corporate form. They engaged an attorney to draft the corporate charter and bylaws and a CPA to set up an accounting system. The total cost of these professional services was $11,000. AB Corporation spent three months locating and renting suitable office space, hiring and training staff, advertising the new business, and applying for the operating license required under local law. These preoperating expenses totaled $62,000. The corporation received an operating license in late May and opened its doors for business on June 8. AB can deduct $5,000 of its organizational costs and must capitalize the $6,000 remainder. Because its start-up expenditures exceeded $55,000, its deduction for these expenditures is reduced to zero, and it must capitalize the entire $62,000. If the corporation reports on a calendar year basis, its amortization deduction for its first taxable year is $2,646 [$68,000 ÷ 180 months = $378 monthly amortization. $378 × seven months (June through December) = $2,646]. AB will amortize the $65,354 remaining capitalized costs over the next 173 months. For tax years beginning in 2010, Congress temporarily increased the maximum initial deduction for startup costs to $10,000, with a phase-out threshold of $60,000. This increase was not extended by the 2010 Tax Relief Act. Thus, for tax years beginning in 2011 and beyond, the maximum initial deduction is once again $5,000. The election to deduct $5,000 of organization and start-up costs and the election to amortize any remaining costs, must be made by the extended due date of the income tax return filed by the new business for the first year in which it conducts business. For costs paid or incurred before September 9, 2008, the election is typically made by attaching a statement to the return referencing the appropriate code section and the costs subject to the election. For organization and start-up costs paid or incurred after September 8, 2008, it is not necessary to attach a statement to the return to make this election. A business can opt to follow the new rules for costs paid or incurred during the 2008 tax year (even on or before September 8, 2008) on its timely filed income tax return for that year. The capitalization requirement for start-up expenditures does not apply to the expansion costs of an existing business [see Section 195(c)(1)(B)]. Example 4-17 Expansion Costs Refer back to example 4-16. Once AB Corporation begins operations, it has established an active business. If it expands to a second location, it will repeat the process of renting a facility, hiring and training additional staff, and advertising the new location. Although the expenses with respect to these activities are functionally identical to the $62,000 start-up expenditures, AB can deduct these expansion expenses because they are incurred in the conduct of an existing business. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-17 Under regulations issued in 2011, taxpayers are no longer required to file a separate election statement to deduct organization and start-up costs. The Service is making this change to facilitate various electronic return filing initiatives. It also noted that most taxpayers with these costs choose to elect to deduct them. Per Reg. Sec. 1.195-1, a taxpayer can forgo the deemed election by clearly electing to capitalize its start-up expenditures (per the form instructions) on a timely filed (including extensions) return for the tax year the business begins. The election either to deduct start-up expenditures under Section 195(b) or to capitalize start-up expenditures is irrevocable. It also applies to all start-up expenditures of the taxpayer that are related to that business. A parallel rule applies in the case of organizational expenditures under Sections 248 and 709. KNOWLEDGE CHECK 5. Start-up expenditures associated with the creation or purchase of a new business are a. b. c. d. Fully deductible in the year business begins. Subject to limited deductibility, with remaining costs capitalized and amortized over 15 years. Amortized over their expected useful life. Not deductible. 6. Mega Corporation commenced business on July 1 of the current year and choose a calendar year for tax purposes. Mega incurred $41,000 of costs properly classified as organization costs. How much of such costs can Mega deduct in its first taxable year? a. b. c. d. 4-18 $41,000 $5,000 $7,400 $6,200 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Other Intangibles Issues TWELVE-MONTH PREPAID EXPENSE RULE Under the final regulations regarding capitalization of intangibles, taxpayers are not required to capitalize amounts, including transaction costs, paid to create or enhance intangible rights or benefits that do not extend beyond the earlier of 12 months after the first date on which the taxpayer realizes the benefit or the end of the tax year following the year in which payment is made [Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(f)]. However, this 12-month rule does not permit an accrual method taxpayer to deduct an amount prepaid for goods and services where the amount has not been incurred under the Section 461(h) economic performance rules. Also, the 12-month rule is not applicable to assets that represent Section 197 amortizable intangibles, nor to a created financial interest described in Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(d)(2). Example 4-18 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(f)(8), (Examples 1 and 2) Prepaid Insurance On December 1, 2016, N Corporation pays a $10,000 insurance premium for a property insurance policy with a one-year term beginning on February 1, 2017. Because the right attributable to the $10,000 payment extends beyond the end of the taxable year following the taxable year in which the payment is made, the 12-month rule does not apply and N is required to capitalize the $10,000 payment. Assume the same facts, except the policy has a one-year term beginning on December 15, 2016. The 12-month rule now applies because the right attributable to the payment neither extends more than 12 months beyond December 15, 2016, (the first date the benefit is realized by the taxpayer), nor beyond the taxable year following the year in which the payment is made. Accordingly, N is not required to capitalize the $10,000 payment. Coordination With Economic Performance Rules In general, the economic performance rules require that an accrual method taxpayer may not claim a deduFWLRQXQWLODQH[SHQVHKDVPHWWKH´DOO-HYHQWVµWHVWDQGHFRQRPLFSHUIRUPDQFHKDVRFFXUUHGZLWK respect to the liability [Section 461(h)]. In general, economic performance occurs as the property or services are provided to the taxpayer. A prepayment for goods or services is treated as economic performance, provided the services are rendered or the goods are provided no more than three and onehalf months after payment [Reg. Sec. 1.461-4(d)] or within the recurring item exception (eight and onehalf months). With respect to an accrual for the rental of property, economic performance is considered to occur ratably over the period covered by the lease or other agreement [Reg. Sec. 1.461-4(d)(3)]. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-19 Example 4-19 12-month Rule for Prepaid Rent U Corp leases office space at a monthly rate of $2,000. On August 1, 2016, U Corp prepays its office rent for the first six months of 2017 in the amount of $12,000. If U Corp is an accrual method taxpayer and subject to the economic performance rules, economic performance is not considered to occur until 2017. Accordingly, U Corp may not use the 12-month rule to deduct its prepaid rent because economic performance has not occurred with respect to the rent prepayment. Alternatively, if U was a cash method taxpayer, then the economic performance rules do not DSSO\$FFRUGLQJO\8&RUSpVSUHSD\PHQWRIUHQWRITXDOLILHVXQGHUWKH-month rule and may be deducted in 2016. Observation: The 12-month rule has greatest application for accrual method taxpayers who are now permitted to prepay an expense that does not have a benefit extending beyond 12 months, thereby permitting a current deduction. However, to avoid the disallowance of this prepaid expense under the economic performance rules, the prepaid expenditure will typically need to relate to an item for which payment is considered to be economic performance under Reg. Sec. 1.461-4, such as insurance, taxes, and licensing fees. Accounting Method Changes A taxpayer desiring to change a method of accounting to comply with Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4, such as an accrual method taxpayer seeking to use the 12-month rule, must secure the consent of the IRS to accomplish the accounting method change [Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-4(p)]. However, the IRS has now provided an indefinite automatic consent accounting method change procedure, to allow adoption of the 12month prepaid expense rule by an accrual method taxpayer (Revenue Procedure 2006-12, IRB No. 20063). This automatic consent procedure applies to tax years ending on or after December 31, 2005. Accrual method taxpayers now may adopt only the 12-month prepaid expense rule using the automatic consent procedures. A taxpayer who wishes to combine a change in accounting method under Reg. Secs. 1.263(a)-4, 1.263(a)-5, or 1.167(a)-3(b) with a change in method of accounting using either the 3½-month prepaid rule or the recurring item exception may apply for both changes on a single application for a change in method of accounting using advance consent procedures of Rev. Proc. 97-27, 1997-1 CB 680. [Rev. Proc. 2006-37, IRB 2006-38.] The automatic consent procedures allow a taxpayer to accomplish an accounting method change by attaching a Form 3115 to a timely filed return. TREATMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL EXPENDITURES Environmental Cleanup The IRS has issued a Revenue Ruling, holding that amounts incurred to clean up land that a taxpayer had contaminated with hazardous waste must be capitalized to inventory under the UNICAP provisions of Section 263A. The contamination had occurred as a result of the operation of a manufacturing plant. The IRS noted that the primary function of the business was to produce inventory, that the contamination had occurred as part of that manufacturing process, and accordingly the expense to remediate the land should be considered a capitalizable inventory item (Rev. Rul. 2004-18, 2004-1 CB 509). 4-20 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Observation: The IRS has indicated that it will not challenge the treatment of environmental remediation costs claimed as current deductions in any taxable year ending on or before February 6, 2004. Accordingly, capitalization of environmental remediation costs to the inventory account under Section 263A is required only for tax years ending after February 6, 2004. Prior IRS rulings had allowed current deductibility of the clean-up of contaminated ground water in a manufacturing business (Rev. Rul. 94-38, 1994-1 CB 35) and the current deductibility of the costs to replace underground storage tanks containing industrial waste and replacing them with new tanks (Rev. Rul. 98-25, 1998-1 CB 998). In a ruling issued in 2005, the IRS has expanded on its earlier position in Rev. Rul. 2004-18 that a PDQXIDFWXUHU·VFRVWVLQFXUUHGIRUHQYLURQPHQWDOUHPHGLDWLRQPXVWEHFDSLWDOL]HGXQGHU6HFWLRQ$WR inventory costs. The latest ruling relates to environmental costs incurred to clean up land or treat groundwater that was contaminated from production activities, and applies where the expenses are not environmental management policy costs under Reg. Sec. 1.263A-1(e)(4) or permissible as current deductions under Section 198. This latest IRS position holds that environmental remediation costs of a manufacturer are properly allocated to property produced during the tax year in which the costs are incurred. This ruling addresses five different situations involving environmental clean-up costs, and in each situation requires capitalization to inventory. These examples included a taxpayer that contaminated while manufacturing one product and currently is manufacturing a different product, a taxpayer no longer using the site on which contamination occurred, and a taxpayer that temporarily ceased its manufacturing activities during the clean-up period (Rev. Rul. 2005-42, 2005-2 CB 67). Observation: Taxpayers using a method of accounting that is not in compliance with Rev. Rul. 2005-42 must file a Form 3115 under the automatic change in method of accounting provisions. Rev. Rul. 200542 provides detailed guidance on the completion of the Form 3115 for this accounting method change. Expensing of Environmental Remediation Costs Section 198 allows a taxpayer to claim a current expense for a qualified environmental remediation expenditure which otherwise would be capitalized. A qualified environmental remediation expenditure must be incurred in connection with the abatement or control of hazardous substances at a qualified contaminated site. A qualified contaminated site is an area on which there has been a release, or threat of release, or disposal of any hazardous substance. The area must be designated as a contaminated site by the appropriate state environmental agency. Any deduction claimed under Section 198 is treated as a depreciation expense for purposes of the Section 1245 depreciation recapture rules, and requires recognition of ordinary income upon disposition of the property with respect to the prior Section 198 deductions. Development: The Tax Relief and Health Care Act extended the Section 198 expensing treatment of qualifying environmental remediation expenditures through December 31, 2007. The act also expanded the definition of hazardous substance to include petroleum products [per Section 4612(a)(3)]. The Tax Extenders and AMT Relief Act of 2008 then extended this provision for expenditures incurred through December 31, 2009. Tax Relief legislation enacted in late 2010 further extended this provision through 2011. This provision has not been extended into 2012 or beyond as of the time this course went to press. Asbestos Removal The Tax Court held that the cost of asbestos removal that was part of a general plan of building renovation had to be capitalized. The court did not rule on the deductibility of asbestos removal done separately (Norwest Corp., 108 TC 358, 4/30/97). Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-21 The IRS has also ruled that the cost of asbestos removal incident to the repair of production plants and machinery needed to be capitalized under Section 263, and was not currently deductible. The taxpayer, an electric utility company, routinely inspected and repaired production plants and machinery, often resulting in a requirement to remove asbestos insulation. The IRS deemed the asbestos insulation to be a part of the production plant and of the capitalized cost of the assets of the plant, and accordingly not currently deductible as an expense (FSA 200035021). In another ruling, the IRS held that a taxpayer had to capitalize the cost of removing asbestos from a portion of its business property, but could deduct the cost of encapsulating asbestos-containing materials in another portion of the property. According to the IRS, the latter did not materially enhance the value of WKHWD[SD\HU·VSURSHUW\VXEVWDQWLDOO\SURORQJLWVOLIHRUDGDSWLWIRUDQHZRUGLIIHUHQWXVH 3/5 However, the Court of Federal Claims has allowed a corporation to deduct, as an ordinary and necessary business expense, the cost of both removing and encapsulating asbestos in an office building. The court found that the asbestos abatement did not increase the value or life of the building, the building was not adapted to a new or different use, and the purpose of the work was to correct a condition of GHWHULRUDWLRQWKDWWKUHDWHQHGWKHEXLOGLQJ·VFRQWLQXHGXVH Cinergy Corp. v. U.S., 2003-1 USTC ¶50,302, U.S. Ct. of Fed. Cl., 3/10/2003). The asbestos abatement work cost the corporation over $800,000 and occurred over a seven-month period. The parties had stipulated to the fact that this asbestos work did not extend the useful life of the structure. The court distinguished this asbestos abatement decision from a Fourth Circuit opinion (Dominion Resources, 2000-2 USTC ¶50,633, CA-4) in which the court found that the cost of removal of asbestos materials should be capitalized, on the grounds that the earlier case involved converting the property into an entirely new use. RESEARCH AND EXPERIMENTAL EXPENDITURES General Rules A corporation has the following options under Section 174 in handling research and experimental costs: x x Deduct such expenditures as they occur [except that deduction is denied for 100 percent of the Section 41 credit claimed for qualified research expenses or basic research expenses unless, under Section 280C(c), the corporation elects on its tax return to reduce its credit by the product of 100 percent of the research credit multiplied by the maximum corporate tax rate (currently 35 percent)], or Capitalize the costs (subject to the same preceding rules where credit is claimed for research expenses). If a taxpayer capitalizes such expenditures, the taxpayer can: x x Recover the costs through depreciation deductions if depreciable assets are produced, or If the outlays do not involve depreciable (or depletable) property, amortize the costs over a period of 60 months or longer as the corporation chooses [Section 174(b)]. Observation: Amortization might be advisable when income is currently low but is expected to rise once the developed product is manufactured. Amortization deductions begin when the developed item begins producing benefits. A new business is allowed to deduct qualified research and experimental expenses for the development of its initial product even though the business has not yet fully developed a product for sale. 4-22 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited The IRS permits the cost of developing computer software to get the same treatment as Research & Experimental expenditures under Section 174 (Rev. Proc. 69-21, 1969-2 CB 303). Definition of Covered Expenses Reg. Sec. 1.174- D GHILQHV´UHVHDUFKRUH[SHULPHQWDOH[SHQGLWXUHVµDVH[SHQGLWXUHVWKDWUHSUHVHQW research and development costs in the experimental or laboratory sense. Expenditures satisfy the preceding definition if they are for activities intended to discover information that would eliminate uncertainty concerning the development or improvement of a product. The requisite uncertainty exists if the information actually available to the taxpayer does not establish the capability or method for developing or improving the product or the appropriate design of the product. For purposes of the definition of research or experimenWDOH[SHQGLWXUHVWKHWHUP´SURGXFWµLQFOXGHVDQ\ pilot model, process, formula, invention, technique, patent or similar property, and includes products to be used by the taxpayer in its business as well as products to be held for sale, lease, or license. However, the term research or experimental expenditures does not include expenditures for ordinary testing or LQVSHFWLRQHIILFLHQF\VXUYH\VPDQDJHPHQWVWXGLHVDGYHUWLVLQJRUSURPRWLRQWKHDFTXLVLWLRQRIDQRWKHU·V patent, model, production or process, or research in connection with literary, historical, or similar projects. The term research or experimental expenditures also applies to costs paid or incurred for research carried RQLQWKHWD[SD\HU·VEHKDOIE\DQRWKHUSHUVRQRURUJDQL]DWLRQ Caution: Under Section 56(b)(2), an individual is required to make an alternative minimum tax (AMT) addback with respect to Section 174 research or experimental expenditures claimed as a deduction. Accordingly, an S corporation must report an AMT adjustment to the shareholder for research and experimentation expenses claimed as a deduction, but this AMT adjustment is not applicable to a C corporation. Capitalization in Lieu of Disallowed Deduction A taxpayer whose research payments were denied a current deduction under Section 174 was allowed to FDSLWDOL]HWKHPLQVWHDG DQGXVHWKHPWRUHGXFHJDLQUHDOL]HGZKHQWKHWD[SD\HU·VUHVHDUFKSURMHFWVZHUH later sold at a profit). The IRS determined that its Section 174 disallowance and the subsequent capitalization were an IRS-LQLWLDWHGFKDQJHLQWKHWD[SD\HU·VDFFRXQWLQJPHWKRGDQGFRQVHTXHQWO\WKH taxpayer did not have to secure IRS consent when it capitalized the expenses (PLR 9707003). AMORTIZABLE BOND PREMIUM Overview A corporation that purchases a bond at a premium is allowed to elect to amortize the bond premium over the period from acquisition of the bond until its maturity. The bond premium is the excess of the purchase price of the bond more than the face value of the bond. The amortization of the bond premium is not claimed as a deduction, but rather is an offset to the interest income received on the bond. Effectively, the amortization reduces the tax basis in the bond and offsets the interest income [Section 171(a); Section 1016(a)(5)]. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 4-23 For tax-exempt bonds, no deduction for the amount of amortization of bond premium is allowed. The amortization is considered to be an offset to the tax-exempt interest income. Accordingly, at maturity, no loss is allowed on a tax-exempt bond purchased at a premium [Section 171(a)(2)]. The amortization of the premium is calculated as an offset to the interest income under the constantyield method. See Reg. Sec. 1.171-2(a). KNOWLEDGE CHECK 7. The capitalized cost of self-created intangibles includes a. b. c. d. 4-24 Research and development costs resulting in intangible assets. Asbestos removal costs. Direct legal costs and application filing fees associated with securing these intangible rights. Costs incurred to create goodwill or going concern value. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Appendix A ADDITIONAL EXAMPLES ² CHAPTERS 2 AND 3 This Appendix is included for supplementary purposes only and is not required for CPE credit. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited A-1 A-2 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 2-1 Materials and Supplies Gruber Company manufactures engine parts. It keeps on hand a supply of lubricant used in its manufacturing process. During the current year, Gruber paid $150,000 to acquire lubricant. If the lubricant is considered an incidental material or supply, Gruber may deduct the cost currently. If the lubricant is considered a non-incidental material or supply, Gruber should maintain inventory records of its purchase and use of the lubricant. It will be entitled to a current year deduction only for the cost of lubricant used or consumed. Example 2-3 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3)(h) Example 6 Unit of Property Costing $200 or Less X operates a business that rents out a variety of small individual items to customers (rental items). X maintains a supply of rental items on hand. In Year 1, X purchases a large quantity of rental items to use in its rental business. Assume that each rental item is a unit of property and costs $200 or less. In Year 2, X begins using all of the rental items purchased in Year 1 by providing them to customers of its rental business. X does not sell or exchange these items on established retail markets at any time after the items are used in the rental business. The rental items are materials and supplies, the amounts that X paid for the rental items in Year 1 are deductible in Year 2, the tax year in which the rental items are used in Xps business. Example 2-4 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(h) Example 7 Unit of Property Costing $200 or Less X provides billing services to its customers. In Year 1, X pays amounts to purchase 50 scanners to be used by its employees. Assume each scanner is a unit of property and costs less than $200. In Year 1, Xps employees begin using 35 of the scanners, and X stores the remaining 15 scanners for use in a later taxable year. The scanners are materials and supplies. The amounts X paid for 35 of the scanners are deductible in Year 1, the tax year in which X uses those machines. The amounts that X paid for the remaining 15 scanners are deductible in the tax year in which each machine is used. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited A-3 Example 2-6 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(h) Example 3 Rotable Spare Parts Optional Method X operates a fleet of specialized vehicles that it uses in its service business. Assume that each vehicle is a unit of property. At the time that it acquires a new type of vehicle, X also acquires a substantial number of rotable spare parts that it will keep on hand to replace similar parts in Xps vehicles as those parts break down or wear out. These rotable parts are removable from the vehicles and are repaired so that they can be reinstalled on the same or similar vehicles. X uses the optional method of accounting for all of its rotable and temporary spare parts. Example 2-8 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(h) Example 14 Election to Apply de minimis Rule X provides consulting services to its customers. In Year 1, X pays amounts to purchase 50 laptop computers. Each laptop computer is a unit of property, costs $400, and has an economic useful life of more than 12 months. Also in Year 1, X purchases 50 office chairs to be used by its employees. Each office chair is a unit of property that costs $100. X has an applicable financial statement and a written accounting policy at the beginning of Year 1 to expense amounts paid for units of property costing $500 or less. X treats amounts paid for property costing $500 or less as an expense on its applicable financial statement in Year 1. The laptop computers are not materials or supplies. Therefore, the amounts X pays for the computers must generally be capitalized as amounts paid for the acquisition of tangible property. The office chairs are materials and supplies. Thus, the amounts paid for the office FKDLUVDUHGHGXFWLEOHLQWKHWD[DEOH\HDULQZKLFKWKH\DUHILUVWXVHGLQ;pVEXVLQHVV+RZHYHULI X properly elects to apply the de minimis safe harbor to amounts paid in Year 1, then X must apply the de minimis safe harbor to amounts paid for the computers and the office chairs, rather than treat the office chairs as the costs of materials and supplies. Under the de minimis safe harbor, X may deduct the amounts paid for the computers and the office chairs in the taxable year paid. Note: Effective for taxable years beginning on or after January 1, 2016, the Internal Revenue Service in Notice 2015-82 increased the de minimis safe harbor threshold from $500 to $2500 per invoice or item for taxpayers without applicable financial statements. In addition, the IRS will provide audit protection to eligible businesses by not challenging the use of the $2,500 threshold for tax years ending before January 1, 2016 if the taxpayer otherwise satisfies the requirements of Treasury Regulation § 1.263(a)-1(f)(1)(ii). A-4 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 2-11 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e)(6) Example 8 Personal Property X owns locomotives that it uses in its railroad business. Each locomotive consists of various components, such as an engine, generators, batteries and trucks. X acquired a locomotive with all its components and treated all the components of the locomotive as being within the same class of property (per Section 168(e)) and depreciated all the components using the same depreciation method. Because Xps locomotive is property other than a building, the initial unit of property is determined under the general rule of functional interdependence. The locomotive is a single unit of property because it consists entirely of components that are functionally interdependent.1 1 In example 2-12, a laptop and printer used by a legal service firm are separate units of property under the test because they are not functionally interdependent even though they can be used together. Example 2-12 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-3(e)(6) Example 14 Leased Personal Property X is engaged in the business of transporting passengers on private jet aircraft. To conduct its business, X leases several aircraft from Y. Assume that each aircraft is not plant property or a network asset. X must treat all of the components of each leased aircraft that are functionally interdependent as a single unit of property. Thus, X must treat each leased aircraft as a single unit of property. Example 2-17 Reg. Sec. 1.162-3(i)(6) Example 7 Routine MaintenancetNot Meeting Safe Harbor X is a Class I railroad that owns a fleet of freight cars. Assume that a freight car, including all its components, is a unit of property and has a class life of 14 years. At the time that X places a freight car into service, X expects to perform cyclical reconditioning to the car every 8 to 10 years in order to keep the freight car in ordinarily efficient operating condition. During this reconditioning, X pays amounts to disassemble, inspect, and recondition or replace components of the freight car with comparable and commercially available and reasonable replacement parts. Ten years after X places the freight car in service, X pays amounts to perform a cyclical reconditioning on the car. Because X expects to perform the reconditioning only once during the 14-year class life of the freight car, the amounts X pays for the reconditioning do not qualify for the routine maintenance safe harbor. Accordingly, X must capitalize the amounts paid for the reconditioning of the freight car if these amounts result in an improvement. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited A-5 Example 2-19 Reg. Sec. 1.263(a)-(h)(10) Example 1 Safe Harbor Applicable A is a qualifying small taxpayer. A owns an office building in which A provides consulting services. In Year 1, Aps building has an unadjusted basis of $750,000. In Year 1, A pays $5,500 for repairs, maintenance, improvements, and similar activities to the office building. Because Aps building unit of property has an unadjusted basis of $1,000,000 or less, Aps building constitutes eligible building property. The aggregate amount paid by A during Year 1 for repairs, maintenance, improvements and similar activities on this eligible building property does not exceed the lesser of $15,000 (2 percent of the buildingps unadjusted basis of $750,000) or $10,000. Therefore, A may elect not to capitalize the amounts paid for repair, maintenance, improvements, or similar activities on the office building in Year 1. If A properly makes the election under paragraph (h)(6) of this section for the office building and the amounts otherwise constitute deductible ordinary and necessary expenses incurred in carrying on a trade or business, A may deduct these amounts in Year 1. Example 2-23 Reg. Sec. 1.263-3(j)(3) Example 13 Replacement with Same Part Not a Betterment M owns a building that it uses for its retail business. Over time, the waterproof membrane (top layer) on the roof of Mps building begins to wear, and M experiences water seepage and leaks throughout its retail premises. To eliminate the problem, a contractor recommends that M put a new rubber membrane on the worn membrane. Accordingly, M pays the contractor to add the new membrane. The new membrane is comparable to the worn membrane when it was originally placed in service by the taxpayer. An amount is paid to improve a building unit of property if the amount is paid for a betterment to the building structure or any building system. The roof is part of the building structure. The condition necessitating the expenditure was the normal wear of Mps roof. To determine whether the amounts are for a betterment, the condition of the building structure after the expenditure must be compared to the condition of the structure when M placed the building into service because M has not previously corrected the effects of normal wear and tear. Under these facts, the amount paid to add the new membrane to the roof is not for a material addition or a material increase in the capacity of the building structure as compared to the condition of the structure when it was placed in service. Moreover, the new membrane is not reasonably expected to materially increase the productivity, efficiency, strength, quality, or output of the building structure as compared to the condition of the building structure when it was placed in service. Therefore, M is not required to treat the amount paid to add the new membrane as a betterment to the building. A-6 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 2-25 Reg. Sec. 1.263-3(k)(7) Example 3 Restoration after Casualty LosstCapitalization X owns an office building that it uses in its trade or business. A storm damages the office building at a time when the building has an adjusted basis of $500,000. X deducts per Section 165 a casualty loss in the amount of $50,000 and properly reduces its basis in the office building to $450,000. X hires a contractor to repair the damage to the building and pays the contractor $50,000 for the work. X must capitalize the $50,000 amount paid to the contractor because X properly adjusted its basis in that amount as a result of a casualty loss. Example 2-28 Reg. Sec. 1.263-3(k)(7) Example 22 Replacement of Major ComponenttPlumbing System X owns a building in which it conducts a retail business. The retail building has three floors. The retail building has men and womenps restrooms on two of the three floors. X decides to update the restrooms by paying an amount to replace the plumbing fixtures in all of the restrooms, including the toilets, sinks, and associated fixtures, with modern style plumbing fixtures of similar quality and function. X does not replace the pipes connecting the fixtures to the buildingps plumbing system. An amount is paid to improve a building if the amount restores the building structure or any building system. The plumbing system, including the plumbing fixtures, is a building system. All of the toilets together perform a discrete and critical function in the operation of the plumbing system, and all of the sinks, together, also perform a discrete and critical function in the operation of the plumbing system. Therefore, all of the toilets comprise a major component of the plumbing system, and all of the sinks comprise a major component of the plumbing system. Accordingly, X must treat the amount paid to replace all of the toilets and all of the sinks as a restoration of the building and must capitalize the amount paid as an improvement to the building. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited A-7 Example 2-30 Reg. Sec. 1.263-3(k)(7) Example 2 Not a New or Different Use X owns and leases out space in a building consisting of twenty retail spaces. The space was designed to be reconfigured; that is, adjoining spaces could be combined into one space. One of the tenants expands its occupancy by leasing two adjoining retail spaces. To facilitate the new lease, X pays an amount to remove the walls between the three retail spaces. Assume that the walls between spaces are part of the building and its structural components. An amount is paid to improve Xps building if it adapts the building structure or any of the building systems to a new or different use. The amount paid to convert three retail spaces into one larger space for an existing tenant does not adapt Xps building structure to a new or different use because the combination of retail spaces is consistent with Xps intended, ordinary use of the building structure. Therefore, the amount paid by X to remove the walls does not improve the building and is not required to be capitalized. Example 3-3 Half-Year Convention During its calendar taxable year, Jones Corporation purchased the following depreciable personal property. Asset Date Placed in Service Depreciable Basis Furniture February 25 $ 0,000 Machine 1 August 1 20,000 Machine 2 December 10 50,000 $140,000 In this case, only 36 percent ($50,000 ÷ $140,000) of the depreciable basis of personal property was placed in service during the last three months of the taxable year. Therefore, Jones uses the half-year convention and calculates six months of depreciation for all three assets. A-8 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-4 Mid-Quarter Convention Refer back to example 3-3. Now assume that Jones purchased an additional machine costing $20,000 on December 4. In this case, 44 percent of the depreciable personal property ($70,000 ÷ $160,000) was placed in service in the last three months of the year. Jones must now use the mid-quarter convention for all four assets, with the following result for the current year. Quarter Placed in Service Months of Depreciation Allowed Furniture First 10.5 Machine 1 Third 4.5 Machine 2 Fourth 1.5 Machine 3 Fourth 1.5 Asset Example 3-5 Convention in Year of Disposition Refer back to example 3-3 in which the half-year convention applied. In the following taxable year, Machine 1 is disposed of on January 20. Because Machine 1 was subject to the half-year convention in the year of acquisition, Jones will also be entitled to six months of depreciation on Machine 1 in the year of disposition, even though the asset was held less than one month of the year. Now consider example 3-4, in which the mid-quarter convention applied. Machine 1 is disposed of on January 20 of the following taxable year, during the first quarter of the year. Because Machine 1 was subject to the mid-quarter convention in the year of acquisition, mid-quarter will also apply in the year of disposition. Jones will be entitled to 1.5 months of depreciation on Machine 1 in the year of disposition. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited A-9 Example 3-7 MACRS Calculation Acme Corp. buys an asset (seven-year class) on February 15, for $10,000 (assume expensing is not elected and a non-bonus depreciation year). The declining balance rate is determined as follows: Divide 1 by 7 to get the basic rate of 1/7 or 14.29 percent. Since this is seven-year property and the 200 percent declining balance applies, Acme multiplies 14.29 percent by 2, or 28.58 percent. A half-year convention must be used. The write-off over the assetps seven-year recovery period is as follows: Year 1: $10,000 × 28.58% = $2,858 × ½ = $1,429 Year 2: $10,000 t $1,429 = $8,571 × 28.58% = $2,450 Year 3: $8,571 t $2,450 = $6,121 × 28.58% = $1,749 Year 4: $6,121 t $1,749 = $4,372 × 28.58% = $1,250 Year 5: $4,372 t $1,250 = $3,122 × 28.58% = $892 The remaining basis at the start of Year 6 will be $2,230 ($3,122 t $892) and the declining balance deduction would be $637 ($2,230 × 28.58%). But by switching to straight-line, the deduction would be $892 ($2,230 / 2.5 remaining years in recovery period) for both Year 6 and Year 7. For Year 8 (final year), Acme can deduct $446 (a half-year of write-off). Thus, the total write-off that Acme will have claimed for the property is the assetps cost ($10,000). Note: Because of the half-year convention, under which a half-year deduction is claimed in the first and last year, a seven-year recovery period asset requires eight tax years to be fully depreciated. Example 3-8 MACRS Depreciation Using IRS Tables Parker bought a computer for $38,000 and placed it in service on September 19. The computer is five-year property subject to the half-year convention. Using exhibit 3-1, Parker will depreciate the computer according to the following schedule. Year Initial Basis Table Percentage 20.00% Depreciation 1 $38,000 $ 7,600 2 38,000 32.00 12,160 3 38,000 19.20 7,296 4 38,000 11.52 4,378 5 38,000 11.52 4,378 6 38,000 5.76 2,188 Note that the table percentages are not adjusted in year one or year six; the half-year convention is already taken into account in computing these percentages. A-10 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-9 Adjusting IRS Tables for Early Disposition Refer back to example 3-8. If Parker sells the computer on May 3 of Year 4, MACRS depreciation for that year is computed by multiplying the otherwise applicable table percentage by 50 percent, as follows: Year four sale depreciation: $38,000 × 11.52% × 50% = $2,189 Example 3-10 IRS Tables and Mid-Quarter Convention Trimble Corporation, a calendar-year taxpayer, purchased small manufacturing tools costing $10,000 on June 2 and other equipment costing $60,000 on October 20. Because greater than 40 percent of Trimbleps personal property acquisitions occurred during the last three months of the year, it must use the mid-quarter convention to calculate depreciation on these assets. Its Year 1 depreciation is as follows. Asset Recovery Life Quarter Placed in Service Table Percentage Depreciation Tools 3-year Second 41.67% $4,167 Equipment 7-year Fourth 3.57 2,142 $6,309 The table percentage applicable to the tools is found in exhibit 3-3; the percentage for the equipment is from exhibit 3-5. Example 3-11 IRS Tables With Disposition and Mid-Quarter Convention Refer back to example 3-10. Suppose that on August 5 of Year 3 Trimble sells the equipment. Because the equipment was subject to the mid-quarter convention in the year of acquisition, mid-quarter will also apply in the year of disposition. Trimble disposed of the equipment during the third quarter of the year; thus, it will be entitled to 7.5 months of depreciation in the year of disposition. Using the Year 3 percentage for seven-year property from exhibit 3-4, Trimbleps depreciation on the equipment in Year 3 is as follows. $60,000 × 18.22% × 7.5 ÷ 12 = $6,833 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited A-11 Example 3-15 Section 179 Deduction Anthony Associates purchased and placed in service in 2014, business property with a cost of $90,000. If the property qualifies under Section 179, Anthony can elect to deduct the entire cost of the acquisition in computing its 2014 taxable income. Example 3-16 Section 179 With MACRS In July 2015, Bennett Corporation acquired and placed in service tangible personal property with a seven-year recovery life costing $540,000. This was the only qualified property acquired during the year. Bennett may elect to deduct $500,000 of the cost under Section 179. The remaining cost of $40,000 will be depreciated under the normal MACRS rules, beginning in 2015. The first-year recovery percentage for MACRS seven-year property (assuming the halfyear convention) is 14.29 percent. Thus, Bennett is allowed MACRS depreciation of $5,716. Example 3-20 Taxable Income Limitation on Section 179 Deduction Dennis Inc. purchased $147,800 of tangible personal property in 2014 and elected to expense WKHHQWLUHFRVW7KHILUPpVWD[DEOHLQFRPHZLWKRXWUHJDUGWRDQ\6HFWLRQ 179 deduction was $129,600. Because of the taxable income limitation, Dennis could deduct only $129,600, thereby reducing taxable income to zero. The $18,200 nondeductible expense carried forward into 2015. Dennis purchased $6,250 of tangible personal property in 2015 and elected to expense the HQWLUHFRVW7KHILUPpVWD[DEOHLncome without regard to any Section 179 deduction was %HFDXVHWKHWD[DEOHLQFRPHOLPLWDWLRQZDVLQDSSOLFDEOHWKHILUPpV6HFWLRQ deduction was $24,450 ($6,250 + $18,200 carryforward), and its taxable income was $569,650. Assume instead that Dennis purchased $493,000 of qualifying property in 2015. In this case, its Section 179 deduction is limited to $500,000 2015 maximum annual deduction ($493,000 + $7,000 carryforward from 2014), and the firm has a $11,200 remaining carryforward to 2016. A-12 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-23 Bonus Depreciation In March 2014, Wallace Inc. acquired and placed in service new tangible personal property with a cost of $700,000. Under MACRS, these assets are five-year recovery property. Without bonus depreciation, Wallaceps cost recovery deduction for 2014 would be $140,000 ($700,000 × 20% first-year MACRS rate for five-year property). With bonus depreciation, Wallaceps total 2014 cost recovery for the property is $420,000, computed as follows. Recovery Deductions Initial cost 50% bonus depreciation Adjusted basis for MACRS MACRS percentage for five-year property $ 700,000 (350,000) $ 350,000 × 20.00% MACRS depreciation $ 70,000 Total cost recovery $420,000 Note that the combination of bonus depreciation and MACRS permits Wallace to deduct 60 percent ($420,000 ÷ $700,000) of the asset cost in the year of acquisition. The remaining asset cost will be depreciated under the normal MACRS rules for the remainder of its recovery life. If the property had been acquired in March 2011, the entire $700,000 cost would have been deductible under 100 percent bonus depreciation in 2011. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited A-13 Example 3-24 Bonus Depreciation and Section 179 Refer back to example 3-23, in which new property was acquired in March 2014. If Wallace elects both Section 179 and 50 percent bonus depreciation for this acquisition, its total 2014 recovery deduction for the asset is $620,000, computed as follows: Recovery Deductions Initial cost $700,000 Section 179 expense (500,000) Adjusted basis for bonus depreciation $200,000 50% bonus depreciation (100,000) Adjusted basis for MACRS $100,000 MACRS percentage for five-year property × 20.00% MACRS depreciation $ 20,000 Total cost recovery $620,000 As a result of these incentive provisions, Wallace is able to deduct 89 percent ($620,000 ÷ $700,000) of the cost of the acquisition in 2014. The remaining unrecovered basis of the asset will be depreciated under the normal MACRS rules for the remainder of its recovery life. Example 3-25 Electing Out of Bonus Depreciation Jensen Corporation acquires an asset costing $5 million that would qualify for 50 percent bonus depreciation. The asset is a five-year MACRS property. With bonus depreciation, first-year cost recovery on the asset would be $3 million ($2.5 million bonus depreciation + ($2.5 million × 20% MACRS first-year depreciation)). If Jensen elects not to claim bonus depreciation, first-year cost recovery is $1 million ($5 million × 20%).The amount of cost recovery foregone by electing out of bonus is $2 million ($3 million t $1 million). The maximum credit increase allowable is $400,000 ($2 million foregone depreciation × 20%), limited to 6 percent of the sum of the WD[SD\HUpVUHVHDUFKDQG$07 credit carryovers from tax years beginning before January 1, 2006. A-14 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-26 Listed Property In the current year, Leslie Higgins acquires a new home computer at a cost of $6,000. She uses the computer 50 percent of the time to manage her investments and 30 percent of the time in KHUFRQVXOWLQJEXVLQHVV/HVOLHpVKRPHFRPSXWHULVOLVWHGSURSHUW\ because it is not used at a regular business establishment. Because her business use percentage for the computer is not greater than 50 percent, she will depreciate it using the straight-line method over the ADS recovery life of five years (see exhibit 3-1). In addition, she is not permitted a Section 179 deduction for the cost of the computer. )RUWKH\HDURIDFTXLVLWLRQWKHFRPSXWHUpVGHSUHFLDWLRQLV ´\HDUFRQYHQWLRQÔ 5-\HDUOLIH /HVOLHpVFRPELQHGEXVLQHVVDQGLQYHVWPHQWXVHSHUFHQWDJHLVSHUFHQW investment use + 30% business use). She is allowed a depreciation deduction equal to $480 ($600 × 80%). Example 3-28 In 2015, West Inc. paid $23,000 for a passenger automobile exclusively for business use by its employees. For MACRS purposes, automobiles are five-year recovery property. Assuming a mid-year convention and no bonus depreciation, the following schedule contrasts MACRS depreciation with limited depreciation for this purchase. Year MACRS GDS Depreciation Maximum Depreciation Allowable Depreciation 2015 $ 4,600 $3,160 $ 3,160 2016 7,360 5,100 5,100 2017 4,416 3,050 3,050 2018 2,650 1,875 1,875 2019 2,650 1,875 1,875 2020 1,324 1,875 1,324 2021 1,875 1,875 2022 1,875 1,875 2023 1,875 1,875 2024 1,875 991 Total $23,000 $23,000 Because MACRS depreciation would exceed the annual limits in all years other than 2020, West will recover its $23,000 cost over 10 years rather than over the normal six years in the MACRS recovery period. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited A-15 Example 3-29 Refer back to example 3-28, in which West Inc. paid $23,000 for a passenger automobile used exclusively for business purposes. If the automobile was acquired in 2014 and was eligible for 50 percent bonus depreciation, the following schedule determines Westps allowable depreciation in each year. Year MACRS GDS Depreciation Maximum Depreciation Allowable Depreciation 2014 $13,800 $11,160 $11,160 2015 3,680 5,100 3,680 2016 2,208 3,050 2,208 2017 1,325 1,875 1,325 2018 1,325 1,875 1,325 2019 662 1,875 662 2020 1,875 1,875 2021 1,875 765 Total $23,000 $23,000 Because $8,000 of bonus depreciation is permitted in the acquisition year, the total recovery period under the passenger automobile limitations is extended to only eight years in this example. A-16 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Example 3-30 Passenger Automobiles and 100 Percent Bonus Refer back to example 3-28, in which West Inc. paid $23,000 for a passenger automobile used exclusively for business purposes. If the automobile was acquired in 2011 and was eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation, the following schedule determines Westps allowable depreciation in each year under the general rules of Revenue Procedure 2011-26. Year MACRS GDS Depreciation 2011 $23,000 Maximum Depreciation Allowable Depreciation $11,060 $11,060 2012 4,900 0 2013 2,950 0 2014 1,775 0 2015 1,775 0 2016 1,775 0 2017 1,775 1,775 2018 1,775 1,775 2019 1,775 1,775 2020 1,775 1,775 2021 1,775 1,775 2022 1,775 1,775 2023 1,775 1,290 Total $23,000 $23,000 In these circumstances, West does not fully recover the cost of the automobile for 12 years. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited A-17 Example 3-31 Election To Use 50 Percent Instead of 100 Percent Bonus Refer back to example 3-30, in which West Inc. paid $23,000 in 2011 for a passenger automobile used exclusively for business purposes and eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation. Under the elective method of Rev. Proc. 2011-26, the following schedule determines Westps allowable depreciation in each year. Year MACRS GDS Depreciation 2011 $23,000 $11,060 $11,060 2012 3,680 4,900 3,680 2013 2,208 2,950 2,208 2014 1,325 1,775 1,325 2015 1,325 1,775 1,325 2016 662 1,775 662 2017 1,775 1,775 2018 1,775 965 Total Maximum Depreciation Allowable Depreciation $23,000 The elective method provides a much faster recovery of the vehicle cost, and is likely to be preferred by most taxpayers. West can choose this method by using it to report depreciation of the automobile on its 2011 tax return. A-18 Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited TAX GLOSSARY 401(k) Plan ² A qualified retirement plan to which contributions from salary are made from pre-tax dollars. Accelerated Depreciation ² Computation of depreciation to provide greater deductions in earlier years of equipment and other business or investment property. Accounting Method ² Rules applied in determining when and how to report income and expenses on tax returns. Accrual Method ² Method of accounting that reports income when it is earned, disregarding when it may be received, and expense when incurred, disregarding when it is actually paid. Acquisition Debt ² Mortgage taken to buy, hold, or substantially improve main or second home that serves as security. Active Participation ² Rental real estate activity involving property management at a level that permits deduction of losses. Adjusted Basis ² Basis in property increased by some expenses (for example, by capital improvements) or decreased by some tax benefit (for example, by depreciation). Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) ² Gross income minus above-the-line deductions (such as deductions other than itemized deductions, the standard deduction, and personal and dependency exemptions). Alimony ² 3D\PHQWVIRUWKHVXSSRUWRUPDLQWHQDQFHRIRQH·VVSRXVHSXUVXDQWWRDMXGLFLDOGHFUHHRU written agreement related to divorce or separation. Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) ² System comparing the tax results with and without the benefit of tax preference items for the purpose of preventing tax avoidance. Amortization ² Write-RIIRIDQLQWDQJLEOHDVVHW·VFRVWRYHUDQXPEHURI\HDUV Applicable Federal Rate (AFR) ² An interest rate determined by reference to the average market yield on U.S. government obligations. Used in Sec. 7872 to determine the treatment of loans with belowmarket interest rates. At-Risk Rules ² Limits on tax losses to business activities in which an individual taxpayer has an economic stake. Backup Withholding ² Withholding for federal taxes on certain types of income (such as interest or dividend payments) by a payor that has not received required taxpayer identification number (TIN) information. Bad Debt ² Uncollectible debt deductible as an ordinary loss if associated with a business and otherwise deductible as short-term capital loss. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Tax Glossary 1 Basis ² $PRXQWGHWHUPLQHGE\DWD[SD\HU·VLQYHVWPHQWLQSURSHUW\IRUSXUSRVHVRIGHWHUPLQLQJJDLQRU loss on the sale of property or in computing depreciation. Cafeteria Plan ² Written plan allowing employees to choose among two or more benefits (consisting of cash and qualified benefits) and to pay for the benefits with pretax dollars. Must conform to Sec. 125 requirements. Capital Asset ² Investments (such as stocks, bonds, and mutual funds) and personal property (such as home). Capital Gain/Loss ² Profit (net of losses) on the sale or exchange of a capital asset or Sec. 1231 property, subject to favorable tax rates, and loss on such sales or exchanges (net of gains) deductible against $3,000 of ordinary income. Capitalization ² Addition of cost or expense to the basis of property. Carryovers (Carryforwards) and Carrybacks ² Tax deductions and credits not fully used in one year are chargeable against prior or future tax years to reduce taxable income or taxes payable. Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) ² A voluntary program for soil, water, and wildlife conservation, wetland establishment and restoration and reforestation, administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Credit ² Amount subtracted from income tax liability. Deduction ² Expense subtracted in computing adjusted gross income. Defined Benefit Plan ² Qualified retirement plan basing annual contributions on targeted benefit amounts. Defined Contribution Plan ² Qualified retirement plan with annual contributions based on a percentage of compensation. Depletion ² Deduction for the extent a natural resource is used. Depreciation ² Proportionate deduction based on the cost of business or investment property with a useful life (or recovery period) greater than one year. Earned Income ² Wages, bonuses, vacation pay, and other remuneration, including self-employment income, for services rendered. Earned Income Credit ² Refundable credit available to low-income individuals. Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) ² Defined contribution plan that is a stock bonus plan or a combined stock bonus and money purchase plan designed to invest primarily in qualifying employer securities. Estimated Tax ² Quarterly payments of income tax liability by individuals, corporations, trusts, and estates. Exemption ² A deduction against net income based on taxpayer status (such as single, head of household, married filing jointly or separately, trusts, and estates). Fair Market Value ² The price that would be agreed upon by a willing seller and willing buyer, established by markets for publicly-traded stocks, or determined by appraisal. 2 Tax Glossary Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Fiscal Year ² A 12-month taxable period ending on any date other than December 31. Foreign Tax ² ,QFRPHWD[SDLGWRDIRUHLJQFRXQWU\DQGGHGXFWLEOHRUFUHGLWDEOHDWWKHWD[SD\HU·V election, against U.S. income tax. Gift ² Transfer of money or property without expectation of anything in return, and excludable from income by the recipient. A gift may still be affected by the unified estate and gift transfer tax applicable to WKHJLIW·s maker. Goodwill ² $EXVLQHVVDVVHWLQWDQJLEOHLQQDWXUHDGGLQJDYDOXHEH\RQGWKHEXVLQHVV·VWDQJLEOHDVVHWV Gross Income ² Income from any and all sources, after any exclusions and before any deductions are taken into consideration. Half-Year Convention ² A depreciation rule assuming property other than real estate is placed in service in the middle of the tax year. Head-of-Household ² An unmarried individual who provides and maintains a household for a qualifying dependent and therefore is subject to distinct tax rates. Health Savings Account (HSA) ² A trust operated exclusively for purposes of paying qualified medical expenses of the account beneficiary and thus providing for deductible contributions, tax-deferred earnings, and exclusion of tax on any monies withdrawn for medical purposes. Holding Period ² The period of time a taxpayer holds onto property, therefore affecting tax treatment on its disposition. Imputed Interest ² Income deemed attributable to deferred-payment transfers, such as below-market loans, for which no interest or unrealistically low interest is charged. Incentive Stock Option (ISO) ² $QRSWLRQWRSXUFKDVHVWRFNLQFRQQHFWLRQZLWKDQLQGLYLGXDO·V employment, which defers tax liability until all of the stock acquired by means of the option is sold or exchanged. Income in Respect of a Decedent (IRD) ² Income earned by a person, but not paid until after his or her death. Independent Contractor ² A self-employed individual whose work method or time is not controlled by an employer. Indexing ² Adjustments in deductions, credits, exemptions and exclusions, plan contributions, AGI limits, and so on, to reflect annual inflation figures. Individual Retirement Account (IRA) ² Tax-exempt trust created or organized in the U.S. for the exclusLYHEHQHILWRIDQLQGLYLGXDORUWKHLQGLYLGXDO·VEHQHILFLDULHV Information Returns² Statements of income and other items recognizable for tax purposes provided to the IRS and the taxpayer. Form W-2 and forms in the 1099 series, as well as Schedules K-1, are the prominent examples. Installment Method² Tax accounting method for reporting gain on a sale over the period of tax years during which payments are made, such as, over the payment period specified in an installment sale agreement. Intangible Property² Items such as patents, copyrights, and goodwill. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Tax Glossary 3 Inventory ² Goods held for sale to customers, including materials used in the production of those goods. Involuntary Conversion ² A forced disposition (for example, casualty, theft, condemnation) for which deferral of gain may be available. Jeopardy ² For tax purposes, a determination that payment of a tax deficiency may be assessed immediately as the most viable means of ensuring its payment. Keogh Plan ² A qualified retirement plan available to self-employed persons. Key Employee ² Officers, employees, and officers defined by the Internal Revenue Code for purposes RIGHWHUPLQLQJZKHWKHUDSODQLV´WRSKHDY\µ Kiddie Tax ² $SSOLFDWLRQRISDUHQWV·PD[LPXPWD[UDWHWRXQHDUQHGLQFRPHRIWKHLUFKLOGXQGHUDJH 19.Full-time students under 24 are also subject to the kiddie tax. Lien ² A charge upon property after a tax assessment has been made and until tax liability is satisfied. Like-Kind Exchange ² Tax-free exchange of business or investment property for property that is similar or related in service or use. Listed Property ² Items subject to special restrictions on depreciation (for example, cars, computers, cell phones). Lump-Sum Distribution ² 'LVWULEXWLRQRIDQLQGLYLGXDO·VHQWLUHLQWHUHVWLQDTXDOLILHGUHWLrement plan within one tax year. Marginal Tax Rate ² 7KHKLJKHVWWD[EUDFNHWDSSOLFDEOHWRDQLQGLYLGXDO·VLQFRPH Material Participation ² 7KHPHDVXUHPHQWRIDQLQGLYLGXDO·VLQYROYHPHQWLQEXVLQHVVRSHUDWLRQVIRU purposes of the passive activity loss rules. Mid-month Convention ² Assumption, for purposes of computing depreciation, that all real property is placed in service in the middle of the month. Mid-quarter Convention ² Assumption, for purposes of computing depreciation, that all property other than real property is placed in service in the middle of the quarter, when the basis of property placed in service in the final quarter exceeds a statutory percentage of the basis of all property placed in service during the year. Minimum Distribution ² A retirement plan distribution, based on life expectancies, that an individual must take after age 70 ½ in order to avoid tax penalties. Minimum Funding Requirements ² Associated with defined benefit plans and certain other plans, such as money purchase plans, assuring the plan has enough assets to satisfy its current and anticipated liabilities. Miscellaneous Itemized Deduction ² Deductions for certain expenses (for example, unreimbursed employee expenses) limited to only the amount by which they exceed 2% of adjusted gross income. Money Purchase Plan ² Defined contribution plan in which the contributions by the employer are PDQGDWRU\DQGHVWDEOLVKHGRWKHUWKDQE\UHIHUHQFHWRWKHHPSOR\HU·VSURILWV 4 Tax Glossary Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Net Operating Loss (NOL) ² A business or casualty loss for which amounts exceeding the allowable deduction in the current tax year may be carried back two years to reduce previous tax liability and forward 20 years to cover any remaining unused loss deduction. Nonresident Alien ² An individual who is neither a citizen nor a resident of the United States. Nonresidents are taxed on U.S. source income. Original Issue Discount (OID) ² The excess of face value over issue price set by a purchase agreement. Passive Activity Loss (PAL) ² Losses allowable only to the extent of income derived each year (such as by means of carryover) from rental property or business activities in which the taxpayer does not materially participate. Passive Foreign Investment Company (PFIC) ² A foreign based corporation subject to strict tax rules which covers the treatment of investments in Sections 1291 through 1297. Pass-Through Entities ² Partnerships, LLCs, LLPs, S corporations, and trusts and estates whose income or loss is reported by the partner, member, shareholder, or beneficiary. Personal Holding Company (PHC) ² A corporation, usually closely-held, that exists to hold investments such as stocks, bonds, or personal service contracts and to time distributions of income in a manner that limits the owner(s) tax liability. Qualified Subchapter S Trust (QSST) ² A trust that qualifies specific requirements for eligibility as an S corporation shareholder. Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) ² A form of investment in which a trust holds real estate or mortgages and distributes income, in whole or in part, to the beneficiaries (such as investors). Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit (REMIC) ² Treated as a partnership, investors purchase interests in this entity which holds a fixed pool of mortgages. Realized Gain or Loss ² The difference bHWZHHQSURSHUW\·VEDVLVDQGWKHDPRXQWUHFHLYHGXSRQLWVVDOH or exchange. Recapture ² The amount of a prior deduction or credit recognized as income or affecting its characterization (capital gain vs. ordinary income) when the property giving rise to the deduction or credit is disposed of. Recognized Gain or Loss ² The amount of realized gain or loss that must be included in taxable income. Regulated Investment Company (RIC) ² A corporation serving as a mutual fund that acts as investment agents for shareholders and customarily dealing in government and corporate securities. Reorganization ² Restructuring of corporations under specific Internal Revenue Code rules so as to result in nonrecognition of gain. Resident Alien ² An individual who is a permanent resident, has substantial presence, or, under specific election rules is taxed as a U.S. citizen. Roth IRA ² Form of individual retirement account that produces, subject to holding period requirements, nontaxable earnings. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Tax Glossary 5 S Corporation ² A corporation that, upon satisfying requirements concerning its ownership, may elect to act as a pass-through entity. 6DYHU·V&UHGLW ² Term commonly used to describe Sec. 25B credit for qualified contributions to a retirement plan or via elective deferrals. Sec. 1231 Property ² Depreciable business property eligible for capital gains treatment. Sec. 1244 Stock ² Closely held stock whose sale may produce an ordinary, rather than capital, loss (subject to caps). Split-Dollar Life Insurance ² Arrangement between an employer and employee under which the life insurance policy benefits are contractually split, and the costs (premiums) are also split. Statutory Employee ² An insurance agent or other specified worker who is subject to social security taxes on wages but eligible to claim deductions available to the self-employed. Stock Bonus Plan ² A plan established and maintained to provide benefits similar to those of a profitsharing plan, except the benefits must be distributable in stock of the employer company. Tax Preference Items ² Tax benefits deemed includable for purposes of the alternative minimum tax. Tax Shelter ² A tax-favored investment, typically in the form of a partnership or joint venture, that is subject to scrutiny as tax-avoidance device. Tentative Tax ² Income tax liability before taking into account certain credits, and AMT liability over the regular tax liability. Transportation Expense ² The cost of transportation from one point to another. Travel Expense ² Transportation, meals, and lodging costs incurred away from home and for trade or business purposes. Unearned Income ² Income from investments (such as interest, dividends, and capital gains). Uniform Capitalization Rules (UNICAP) ² Rules requiring capitalization of property used in a business or income-producing activity (such as items used in producing inventory) and to certain property acquired for resale. Unrelated Business Income (UBIT) ² Exempt organization income produced by activities beyond the RUJDQL]DWLRQ·VH[HPSWSXUSRVHVDQGWKHUHIRUHWD[DEOH Wash Sale ² Sale of securities preceded or followed within 30 days by a purchase of substantially identical securities. Recognition of any loss on the sale is disallowed. 6 Tax Glossary Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited CAPITALIZED COSTS AND DEPRECIATION BY DR. SHELLEY RHOADES-CATANACH, PH.D., CPA Solutions The AICPA offers a free, daily, e-PDLOHGQHZVOHWWHUFRYHULQJWKHGD\¶VWRSEXVLQHVVDQG financial articles as well as video content, research and analysis concerning CPAs and those who work with the accounting profession. Visit the CPA Letter Daily news box on the www.aicpa.org home page to sign up. You can opt out at any time, and only the AICPA can use your e-mail address or personal information. Have a technical accounting or auditing question? So did 23,000 other professionals who contacted the AICPA's accounting and auditing Technical Hotline last year. The objectives of the hotline are to enhance members' knowledge and application of professional judgment by providing free, prompt, high-quality technical assistance by phone concerning issues related to: accounting principles and financial reporting; auditing, attestation, compilation and review standards. The team extends this technical assistance to representatives of governmental units. The hotline can be reached at 1-877-242-7212. SOLUTIONS CHAPTER 1 Solutions to Knowledge Check Questions 1. a. Incorrect. Amounts paid for permanent improvements or betterments to real property are required to be capitalized. b. Incorrect. Amounts paid to facilitate an acquisition of a trade or business are required to be capitalized. c. Incorrect. Amounts paid to defend or perfect title to real property are required to be capitalized. d. Correct. Employee compensation and overhead costs related to the acquisition of property generally are not required to be capitalized. However, taxpayers are allowed to elect to capitalize such costs. 2. a. Correct. Obligations of the seller assumed and paid by the purchaser are part of cost basis. b. Incorrect. Real property taxes apportioned to and paid by the purchaser related to periods subsequent to the purchase are typically deductible. c. Incorrect. The seller would be allowed a deduction for real property taxes paid by the seller, not by the purchaser. d. Incorrect. Real property taxes are either deductible or included in cost basis, depending on the period to which they relate and the party paying the tax. 3. a. Incorrect. Basis includes the full amount of the liability incurred or assumed to acquire property, and does not depend on the timing of debt payments. b. Correct. The amount of any liability incurred or assumed by the taxpayer to acquire the property is included in basis. c. Incorrect. Basis does not include debt incurred after acquisition that is secured by the property. d. Incorrect. Capitalized loan acquisition costs are not included in the basis of the acquired property, but constitute a separate intangible asset. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Solutions 1 4. a. Incorrect. Direct materials and direct labor costs are included in cost basis of self-constructed assets, but they are not the only costs required to be capitalized. b. Correct. The cost basis of self-constructed assets includes both direct costs and a portion of the WD[SD\HU·VLQGLUHFWFRVWVWKDWGLUHFWO\EHQHILWRUDUHLQFXUUHGE\UHDVRQRIWKHFRnstruction activities. c. Incorrect. Income taxes are not subject to capitalization into the cost basis of self-constructed assets. d. Incorrect. Property produced for the taxpayer under a contract with another party is treated as property produced by the taxpayer to the extent the taxpayer makes payments or otherwise incurs costs with respect to the property. 5. a. Incorrect. The tax basis of property acquired as part of a nontaxable exchange typically equals a substituted basis. b. Incorrect. The tax basis of property acquired by purchase or in a taxable exchange typically equals cost. c. Correct. The tax basis of the acquired property will be based, in whole or in part, on the adjusted tax basis of the property given up in the exchange. Such tax basis is typically referred to as substituted basis. d. Incorrect. The substituted-basis rule ensures that unrecognized gains and losses are merely deferred until some future time, by embedding the unrecognized gain or loss in the basis of the qualifying property received. A fair market value basis would allow the unrecognized gain or loss to permanently escape taxation. CHAPTER 2 Solutions to Knowledge Check Questions 1. a. b. c. d. Incorrect. Capitalization of materials and supplies is elective, not required. Incorrect. The cost of incidental materials and supplies is deductible when paid. Correct. The cost of non-incidental materials and supplies is deductible when used or consumed. Incorrect. Generally, non-incidental materials and supplies are consumed rather than made part of inventory items. 2. a. Incorrect. Rotable spare parts are generally considered non-incidental materials and supplies. b. Incorrect. Taxpayers may elect, but are not required, to capitalize and depreciate the cost of rotable spare parts. c. Incorrect. Only such costs qualifying under a de minimis safe harbor election may be deductible currently. d. Correct. The new optional method of accounting applies to rotable and temporary spare parts, but may not be used for standby emergency spare parts. 2 Solutions Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3. a. Incorrect. Non-incidental materials and supplies are deductible when consumed, not when purchased. b. Incorrect. The cost of standby emergency spare parts with a useful life of greater than 12 months is deductible either when disposed of, installed on a unit of property, or through depreciation, GHSHQGLQJRQWKHWD[SD\HU·VFKRLFHRIDPHWKRGRIDFFRXQWLQJ c. Correct. The cost of incidental materials and supplies for which inventory records are not maintained is deductible at the time of purchase. d. Incorrect. Direct materials incorporated into inventory must be capitalized and deducted through cost of goods sold. 4. a. Incorrect. Building systems as identified in the regulations are considered separate units of property distinct from the building structure. b. Incorrect. An individual building system, such as the HVAC system, is a single unit of property. c. Correct. Fire-protection and alarm systems, and security systems are among the building systems specifically identified in the unit of property regulations. d. Incorrect. Elevators and escalators are considered building systems, not part of the building structure, for purposes of the unit of property rules. 5. a. Correct. Expenses qualifying under the routine maintenance safe harbor are deductible as ordinary and necessary business expenses. b. Incorrect. Routine maintenance under the safe harbor includes the replacement of damaged or worn parts with comparable and commercially available replacement parts. c. Incorrect. With respect to buildings, maintenance activities are routine only if the taxpayer reasonably expects to perform such activities more than once during the 10-year period beginning when the building structure or system on which the routine maintenance is performed is placed in service by the taxpayer. d. Incorrect. The routine maintenance safe harbor is not restricted to small taxpayers. However, there is a building safe harbor that is only available to qualifying small taxpayers. 6. a. Incorrect. Betterments are a category of improvement distinct from adaption of property to a new or different use. b. Incorrect. Expenditures to adapt property to a new or different use are generally not considered repairs and are not currently deductible. c. Incorrect. Expenditures to adapt property to a new or different use are generally not considered maintenance costs and are not currently deductible. d. Correct. Expenditures to adapt property to a new or different use must be capitalized as improvements and recovered through depreciation. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Solutions 3 7. a. Incorrect. Except for the building safe harbor for small taxpayers, the optional regulatory accounting method, and the election to capitalize repairs and maintenance, a taxpayer may choose to apply these rules to tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2012. A taxpayer may choose to apply the building safe harbor for small taxpayers, the optional regulatory accounting method, and the election to capitalize repairs and maintenance to amounts paid in taxable years beginning on or after January 1, 2012. b. Incorrect. There rules generally apply to tax years that begin on or after January 1, 2014. However, a taxpayer may choose to apply some of the rules to tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2012. c. Correct. In general, these rules apply to tax years that begin on or after January 1, 2014. d. Incorrect. In general, these rules apply to tax years that begin on or after January 1, 2014. The building safe harbor for small taxpayers, the optional regulatory accounting method, and the election to capitalize repairs and maintenance apply to costs incurred in tax years beginning on or after January 1, 2014. 8. a. Correct. A change to the optional method of accounting for rotable and temporary spare parts is not eligible for the cut-off method. b. Incorrect. Change to deducting non-incidental materials and supplies when used or consumed is eligible for the cut-off method. c. Incorrect. Change to deducting incidental materials and supplies when paid or incurred is eligible for the cut-off method. d. Incorrect. Change to deducting non-incidental rotable and temporary spare parts when disposed of is eligible for the cut-off method. CHAPTER 3 Solutions to Knowledge Check Questions 1. a. b. c. d. Incorrect. Certain farm buildings are assigned a recovery period of 20 years. Incorrect. Residential rental property is assigned a recovery period of 27.5 years. Correct. Nonresidential real property is assigned a recovery period of 39 years. Incorrect. Railroad grading and tunnel bores are assigned a recovery period of 50 years. 2. a. Incorrect. The half-year convention applies to depreciable personal property rather than real property. b. Correct. The mid-month convention applies to the year in which depreciable real property is placed in service or disposed of. c. Incorrect. The mid-quarter convention applies to depreciable personal property when more than 40 percent of acquisitions occur within the fourth quarter of the taxable year. d. Incorrect. Tax depreciation in the year of acquisition follows a part-year convention rather than requiring daily proration of depreciation amounts. 4 Solutions Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited 3. a. Incorrect. Depreciable real property must be depreciated using the straight-line method. b. Correct. Assets with a 3-year, 5-year, 7-year, or 10-year recovery period are depreciated using a 200 percent (double) declining-balance method. Assets with a 15-year or 20-year recovery period are depreciated using a 150 percent declining-balance method. c. Incorrect. Tax and financial accounting depreciation methods typically differ significantly. d. Incorrect. Allowable depreciation methods are specified by the MACRS rules. 4. a. Incorrect. Section 179 depreciation limitation begins when annual purchases of Section 179 property exceed a threshold of $2,000,000. b. Incorrect. The maximum Section 179 deduction was $250,000 for qualifying property placed in service in 2008 and 2009. c. Incorrect. The maximum Section 179 deduction was $100,000 (adjusted for inflation) for qualifying property placed in service in 2003 through 2006. d. Correct. With passage of the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015, the maximum Section 179 deduction of $500,000 is now permanent. 5. a. Correct. The most common type of qualified property for Section 179 is tangible personal property. b. Incorrect. Section 179 specifically excludes buildings and their structural components from the definition of qualified property, with limited exceptions that expired on December 31, 2013. c. Incorrect. Section 179 also applies to off-the-shelf computer software (not internally developed software) the cost of which is amortizable over 36 months. d. Incorrect. Qualified property must be acquired by purchase, but cannot be purchased from a related party. 6. a. Incorrect. The bonus depreciation percentage was 100 percent for qualifying acquisitions placed in service after September 8, 2010, and before January 1, 2012. b. Correct. The bonus percentage for 2017 acquisitions is 50 percent. c. Incorrect. As originally enacted, an additional first-year depreciation deduction equal to 30 percent of depreciable basis was available with respect to qualified property placed in service after September 10, 2001, and before January 1, 2005. d. Incorrect. For qualifying acquisitions after May 5, 2003, and before January 1, 2005, taxpayers could choose whether to apply the 30 percent or 50 percent deduction. 7. a. Incorrect. In this case, taxpayers are not permitted a choice. b. Correct. If property qualifies for both of these incentive provisions, Section 179 is applied first. c. Incorrect. If property qualifies for both of these incentives, bonus depreciation may be taken, only after basis has been reduced by the Section 179 deduction. d. Incorrect. Taxpayers are entitled to both incentive provisions if the property qualifies. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Solutions 5 8. a. Incorrect. Depreciation on passenger automobiles is limited both when the business use percentage does not exceed 50 percent and when MACRS depreciation exceeds the annual depreciation limitations provided for passenger automobiles. b. Incorrect. If for a given taxable year the business use percentage of any listed property does not exceed 50 percent, depreciation on such property is computed using ADS. c. Correct. The annual depreciation deduction for passenger automobiles may not exceed the limits provided under a special schedule, which is adjusted annually for inflation. d. Incorrect. Allowable depreciation equals the lesser of MACRS or the annual limitation. 9. a. Incorrect. Initial basis of property is used to compute MACRS depreciation prior to an exchange or involuntary conversion. b. Correct. Excess basis in the replacement property is treated as property placed in service in the year of the replacement. Thus, excess basis is recovered over the MACRS recovery life of the replacement property, using the applicable MACRS convention and recovery method. c. Incorrect. With regard to exchanged basis, if the relinquished asset and the replacement asset are subject to the same MACRS recovery life and method, the taxpayer continues to depreciate the replacement asset over the remaining recovery life of the relinquished asset. If the replacement asset has a shorter recovery period, or is subject to a more accelerated depreciation method than the relinquished asset, the taxpayer depreciates the exchanged basis of the replacement asset over the remaining recovery life of the relinquished asset using the recovery method applicable to the relinquished asset. In effect, in these circumstances cost recovery of the exchanged basis continues as though the taxpayer still owned the relinquished asset. If the replacement asset has a longer recovery period, or is subject to a less-accelerated depreciation method than the relinquished asset, the taxpayer depreciates the exchanged basis of the replacement asset over the remaining portion of its longer recovery life, using the less-accelerated recovery method applicable to the replacement asset. d. Incorrect. The term substituted basis generally applies to assets acquired in a like-kind exchange or other nontaxable exchange transaction, rather than an involuntary conversion. 6 Solutions Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited CHAPTER 4 Solutions to Knowledge Check Questions 1. a. Incorrect. While direct purchase price is capitalized, related acquisition costs may also be included in the tax basis of the intangible. b. Correct. In addition to the direct purchase price of the intangible, the taxpayer must capitalize any amount paid to facilitate the acquisition of the intangible, including amounts paid in the process of investigating the acquisition. Such capitalized transaction costs include appraisal costs, payments to outside legal counsel assisting in the negotiation of the acquisition or preparing contracts, and payments to accountants or other consultants assisting in establishing the value of the intangible or negotiating its acquisition. c. Incorrect. In an important simplification of the transaction cost capitalization rule, employee compensation and de minimis costs are not capitalized as amounts that facilitate the acquisition or creation of an intangible. For this purpose, costs that do not exceed $5,000 are considered de minimis. d. Incorrect. Overhead costs are not capitalized as amounts that facilitate the acquisition or creation of an intangible. 2. a. Incorrect. Under the residual method, any premium paid by the purchaser cannot be allocated proportionately among the other assets. b. Incorrect. Tangible assets are allocated purchase price up to their fair market value. c. Incorrect. Identifiable intangible assets are allocated purchase price up to their fair market value. d. Correct. Under this method, any premium paid by the purchaser in excess of the fair market value of tangible and identifiable intangible assets is treated as goodwill. 3. a. Incorrect. Self-created goodwill typically has no tax basis and is not amortizable under Section 197. b. Correct. Section 197 intangibles include business books and records, operating systems, or any other information base including customer lists. c. Incorrect. Section 197 intangibles specifically exclude futures contracts, foreign currency contracts, notional principal contracts, or other similar financial contracts. d. Incorrect. Land is not amortizable or depreciable. 4. a. Incorrect. The arbitrary, 15-year amortization period of Section 197 is imposed regardless of the actual or expected economic life of the intangible. In addition, no loss is allowed with respect to a covenant not to compete until the entire interest in the acquired business with which the covenant relates is disposed of. b. Correct. Section 197 intangibles are amortized ratably over the 15-year period beginning with the month in which such intangible was acquired. c. Incorrect. A covenant not to compete acquired as part of the acquisition of an ongoing business is considered a Section 197 intangible. Associated costs are amortizable over a 15-year period. d. Incorrect. A covenant not to compete is considered an intangible asset, whose cost is only recoverable through amortization. Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited Solutions 7 5. a. Incorrect. Start-up expenditures are not considered ordinary and necessary business expenses and are therefore not immediately deductible. b. Correct. A firm may deduct the lesser of its actual start-up expenditures or $5,000. This $5,000 maximum is reduced by the amount by which total expenditures exceed $50,000. The firm must capitalize any nondeductible start-up expenditures and may elect to amortize such costs over a 180-month period starting with the month in which business begins. c. Incorrect. Regardless of their expected useful life, start-up costs are amortized over 180 months. d. Incorrect. Such costs are deductible or amortizable at the election of the taxpayer. 6. a. Incorrect. Organization costs must be capitalized under Section 248 and are not immediately deductible. b. Incorrect. In addition to the upfront deduction of $5,000 of organization costs permitted under Section 248, Mega is permitted to amortize its remaining $36,000 of organization costs of 180 months. c. Incorrect. Because Mega commenced business on July 1, it is permitted only six months of amortization in the first year. d. Correct. Mega may deduct $5,000 of its organization costs in the first year of operations. It may amortize the remainder over 180 months beginning July 1. Current year amortization is $1,200 = ($41,000 - $5,000) x 6 months ÷ 180 months. MegD·VWRWDOGHGXFWLRQLQLWVILUVWWD[DEOH\HDULV $6,200. 7. a. Incorrect. Costs associated with research and development, which results in intangible assets, are routinely deducted under Section 174. b. Incorrect. Asbestos removal costs are not considered an intangible asset. When not deductible, they are capitalized as an improvement to the tangible asset to which they relate. c. Correct. Only direct legal costs and application filing fees associated with securing these intangible rights would be capitalized. d. Incorrect. Costs producing goodwill and going concern value, such as employee salaries, customer service, superior products, and the like, are deductible either as ordinary and necessary business expenses or through cost of goods sold. 8 Solutions Copyright 2017 AICPA Unauthorized Copying Prohibited