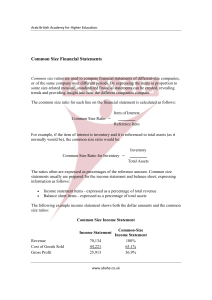

Introduction to PEHAA Basics of Corporate Finance 1 CONTENT Role and objective function of corporate finance within an organization Basic Corporate Finance Principles Cash flow and Capital Budgeting Approaches and Decision Rules Financial management framework in a public enterprise Main principles and rules of financial management in an SOE The anatomy of financial statements and how to read them Financial statement Analysis Mergers and Acquisitions 2 Role and objective function of corporate finance within an organization 3 FUNCTIONS OF CORPORATE FINANCE • Determine funding requirements • Investment profitability of investment decisions • Determine when to distribute dividends or investment back in business • Choose for debt/ equity or a mix of both Capital Budgeting Capital Structure Dividend Distribution Working Capital Requirements • Managing capital for day-to-day operations 4 FUNCTIONS OF CORPORATE FINANCE Planning finances: Here is where the comprehensions are made use of to determine the finances of the company effectively. Decisions need to be taken on how much finance is needed, how it will be sourced, where it will be invested, would the investment bring in profits, how much is anticipated profits and such to decide on a firm plan-ofaction. Capital raising: This is a vital stage highlighting the importance of corporate finance and decisions taken here will involve assessment of company assets four sources to fund investments. To raise enough capital a company may decide to sell shares, issue debentures and shares, take bank loans, ask creditors to invest etc 5 FUNCTIONS OF CORPORATE FINANCE Investments: Investments can be either on working capital or fixed assets. Fixed capital is utilised for financing the purchase of machinery, infrastructure, buildings, technological upgrades and property. However, working capital is required four day to day activities like rawmaterial purchases, running expenses of the company, salaries and overheads and bills. Risk management and financial monitoring: Persistently keep an eye on the investments is required. Riskmanagement aims to reduce and mitigate the undertaken risks of investments and forms a part of the on-going monitoring process. 6 ACTIVITIES OF CORPORATE FINANCE Investments & Capital Budgeting : Investing and capital budgeting is one the activities in corporate finance that includes planning where to place the company’s long-term capital assets in order to generate the highest riskadjusted returns. This mainly consists of deciding whether to pursue an investment opportunity through extensive financial analysis. Financial modelling, also falling under Investing and capital budgeting as one the activities in corporate finance, is used to estimate the economic impact of an investment opportunity and compare alternative projects. An analyst with often use Internal Rate of Return (IRR) in conjunction with Net Present Value (NPV) to compare projects and pick the optimal one. 7 ACTIVITIES OF CORPORATE FINANCE Capital Financing: This is one of the core activities in corporate finance and includes decisions on how to optimally finance the capital investments through the business’ equity, debt, or a mix of both. Long-term funding four major capital expenditures or investments may be obtained from selling company stocks or issuing debt securities in the market through investment banks. Balancing the two sources – equity and debt, should be closely managed as one of the activities in corporate finance because having too much debt may increase the risk of default in repayment, while depending too heavily on equity may dilute earnings and value four original investors. Dividends & Return of Capital: Dividends & Return of Capital requires the corporate finance professionals within the company to decide whether to retain a business’s excess earnings four future investments and operational requirements or to distribute the earnings to shareholders in the form of dividends or share buybacks. 8 Basic Corporate Finance Principles (Financing; Investment; and Dividend principles) 9 FINANCING, INVESTMENT, DIVIDEND PRINCIPLES Investment Definition: An investment is an asset or item acquired with the goal of generating income or appreciation. Appreciation refers to an increase in the value of an asset over time. When an individual purchases a good as an investment, the intent is not to consume the good but rather to use it in the future to create wealth. Financing Definition: Financing is the process of providing funds for business activities, making purchases, or investing. Financial institutions, such as banks, are in the business of providing capital to businesses, consumers, and investors to help them achieve their goals. Dividend Definition: A dividend is the distribution of a company's earnings to its shareholders and is determined by the company's board of directors. Dividends are often distributed quarterly and may be paid out as cash or in the form of reinvestment in additional stock. 10 Basic Corporate Finance Concepts 11 CAPITAL BUDGETING PROCESS To identify Investment Opportunities Gathering of the Investment Proposals Review of Performance Capital Budgeting Process Decision Making Process in Capital Budgeting Implementation Capital Budget Preparations & Appropriations 12 CAPITAL BUDGETING The process of identifying, evaluating, planning, and financing capital investment projects of an organization. Capital budgeting is defined “as the firm’s formal process for the acquisition and investment of capital. It involves firm’s decisions to invest its current funds for addition, disposition, modification and replacement of fixed assets”. “Capital budgeting is long term planning for making and financing proposed capital outlays”- Charles T. Horngreen. 13 CAPITAL BUDGETING Capital budgeting involves capital investment projects which require large sum of outlay and involve a long period of time – longer than the usual cut-off of one year or normal operating cycle. “Capital budgeting consists in planning development of available capital for the purpose of maximizing the long term profitability of the concern” – Lynch The main features of capital budgeting are Potentially large anticipated benefits A relatively high degree of risk Relatively long time period between the initial outlay and the anticipated return. - OsterYoung 14 CAPITAL BUDGETING The success and failure of business mainly depends on how the available resources are being utilized. Main tool of financial management All types of capital budgeting decisions are exposed to risk and uncertainty. They are irreversible in nature. Capital rationing gives sufficient scope for the financial manager to evaluate different proposals and only viable project must be taken up for investments. Capital budgeting offers effective control on cost of capital expenditure projects. It helps the management to avoid over investment and under investments. 15 CHARACTERISTICS OF CAPITAL INVESTMENT DECISIONS Capital investment decisions usually require relatively large commitments of resources. Most capital investment decisions involve long-term commitments. Capital investment decisions are more difficult to reverse than short-term decisions. 16 Working Capital: The Elements THE ELEMENTS OF WORKING CAPITAL current assets current liabilities Major elements: Inventories Accounts receivable Cash (in hand and at bank) Major elements: Short term loans Accounts payable working capital current assets - current liabilities = working capital 17 17 17 WHY IS WORKING CAPITAL IMPORTANT? Working capital... Is used to keep the organisation running on a day-to-day basis Represents a net investment in short-term assets Defines the liquidity of the business (whether or not the business is solvent in the short term) Directly related to the cash flow from operating activities. 18 18 WORKING CAPITAL: THE BUSINESS CYCLE Cash: Start. Company pays for raw materials Purchases 1 9 Cash: End. Customer pays for product or service 2 Collections 8 Current Assets Materials Inventory 3 7 4 Operating Cycle Production 5 Accounts Receivable 6 Sales Finished Inventory 19 WORKING CAPITAL (CASH CONVERSION) CYCLE TIMELINE - Working Capital Cycle Jan Feb March April May Creditors 62 Days Raw Materials 25 days Work in Progress 30 days Finished Goods 19 days Debtors •69 Days Financing Gap •81 Days Purchase Collection Day 0 | Sale Da y 62 Payment | Day 74 | Day 143 | 20 CASH CONVERSION CYCLE 21 MANAGEMENT OF WORKING CAPITAL Debtor Receivables Collection Days = Average Trade Debtors X 365 Credit Sales A decrease indicate: - A recent large payment received just before balance sheet date - Improved control of receivables; - Urgent need for cash. NB: -If average figure is not available, use the balance sheet figure instead - If credit sales not available, use the sales figure X Increase may indicate: - Poor control of receivables by the Company (e.g. failure to issue invoices in a timely manner; failure to pursue overdue debts); - Relaxation of credit terms to attract new business or as a result of competition; - A significant overdue payment or many customers struggling to pay 22 WORKING CAPITAL RATIOS Inventory Turnover Days (i.e. Inventory days) NB: If average figure is not = Average Inventory X 365 available, use the balance Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) sheet figure instead Decrease may indicate - A recent delivery just before the balance sheet was created - Inventory selling more quickly; - A rundown of inventories because of a need to generate cash; - Improved inventory control by the business X Increase may indicate - Inability to sell inventory, e.g. out of date/poor quality; - Failure to manage inventory levels; - Large contract due requiring a build up of inventory; - Planned inventory build up due to change in policy. 23 WORKING CAPITAL RATIOS Creditor Payment Days: Average Trade Creditors X 365 Cost of Goods (Inventory) bought on credit Increase may indicate - Company unable to pay bills on time; - Taking advantage of extended terms; - Deferring payments to preserve cash. - A large invoice received just before the date of the balance sheet. NB: -If average figure is not available, use the balance sheet figure instead - If purchases on credit not available, use cost of goods sold Decrease may indicate - Paying early to get discounts; Pressure from accounts - A large payment made just before the date of the balance sheet 24 WORKING CAPITAL RATIOS CAN BE EXPRESSED IN ‘DAYS’ OR AS ‘TURNOVER’ Cash Tied Up in Inventory Inventory Turnover = Cost of Goods Sold Average Inventory Inventory Days = Average Inventory Cost of Goods Sold x 365 Cash Tied Up in Receivables Receivables(debtor) Turnover = Credit Sales _________ Average Trade Debtors Receivables Days =Average Trade Debtors x 365 Credit Sales Cash Belonging to Creditors Held in by the Business Payables (creditor) Turnover = Cost of Goods bought on credit Average Trade Creditors Payables Days =Average Trade Creditors _____ x 365 Cost of Goods Bought on Credit 25 CASH CONVERSION (WORKING CAPITAL) CYCLE : CCC CCC= Inventory days + Receivable days – Payables days. ** This is the net days that funds are held up in inventories and trade counterparties** Usually, a short CCC means greater liquidity, which translates into less of a need to borrow, more opportunity to realize price discounts with cash purchases for raw materials, and an increased capacity to fund the expansion of the business into new product lines and markets. Conversely, a longer CCC increases an Company's cash needs 26 WORKING CAPITAL RATIOS Net Working Assets (NWA) to Sales = (Receivables + Inventory – Account Payable ) x 100 Sales This is an efficiency ratio. It indicates how the main components of working capital are being managed in relation to sales. If the ratio is increasing, it may indicate that the Company is mismanaging its key working assets. Careful management often results in a fall of this ratio. As sales increase the ratio should remain the same if NWA are being managed successfully. 27 OVERTRADING Definition: Conducting more business than the Company's working capital can normally sustain thus placing serious strain on cash flow and risking collapse or insolvency. There comes a point when increased sales volumes are no longer sustainable. a) Possible Signs of Overtrading (i) A large increase in sales or current assets or current liabilities with little increase in owners’ equity. (ii) Taking longer credit or giving longer credit.(iii) Gross and net profit margin falling (caused by an effort to raise cash to pay bills). (iv) If outside finance provided by loans and suppliers exceeds the owners’ equity (net assets) b) Dangers of Overtrading : Cash flow becomes tighter and production levels inevitably fall once loan facilities are fully drawn. This can result in a fall in profitability and a lack of liquidity to pay overheads as they fall due. In serious cases this will result in business failure. 28 EXERCISE: MAX LTD’S WORKING CAPITAL RATIOS Calculate Max Ltd’s Inventory Turnover and Inventory days Receivables (debtor) turnover and days Account payables (creditor) turnover and days Cash conversion cycle 29 EXERCISE: CALCULATE MAX LTD’S WORKING CAPITAL RATIOS Inventory Turnover and Inventory days Receivables (debtor) turnover and days Account payables (creditor) turnover and days Cash conversion cycle 30 Managing Working Capital CALCULATING WORKING CAPITAL REQUIREMENT: Urban fashion Sales COGS Receivables Inventory Payables Year 1 100,000 70,000 38 Days 10,328 75 Days 14,384 Year 2 110,000 77,000 11,362 15,822 24,712 6,712 26,671 7,384 18,000 18% 18,000 19,800 18% 18,000 35 Days Net working capital requirement Percent of annual sales Financed by: Owner's equity Retained profit Year 2 assume 1% of sales Shortfall 1,100 700 31 31 31 Managing Working Capital CASH FLOW STATEMENTS Sources and uses of cash Sources: Uses: Increase in a liability Decrease in an asset Increase in an asset Increase in equity Decrease in equity Profit from operations Loss from operations Decrease in a liability 32 32 32 Managing Working Capital REMEMBER….. THE WORKING CAPITAL CYCLE Time-line example Raw Materials Work in Progress Finished Goods Accounts Receivable Total Less Payables Total 55 Days 78,000 19 Days 69 Days 25,000 207,000 143 Days 310,000 62 Days 82,000 81 Days 228,000 33 33 33 Managing Working Capital REMEMBER……TIMELINE OF THE WORKING CAPITAL CYCLE January February March April May Creditors 62 days Raw Materials 25 days Work in Progress Finished Goods 30 days 19 days Debtors 69 days Financing Gap 81 days Day 0: Purchase Day 62: Payment Day 74: Sale Day 143: Collection 34 34 34 Managing Working Capital TIMELINE – WORKING CAPITAL CYCLE January February March Creditors 62 days Raw Materials 25 days Work in Progress Finished Goods 30 days 19 days Effective management of terms of April May trade can improve the finance gap. Poor management will worsen it. Debtors 69 days Financing Gap 81 days Day 0: Purchase Day 62: Payment Day 74: Sale Day 143: Collection 35 35 35 Managing Working Capital EXAMPLE The effect of a growth in sales on working capital Year 1 000's Ratio 1,000 100,000 COGS 800 70,000 Gross Profit 200 10,328 Gross Profit% 20% 14,384 Inventory 87.7 40 days 109.6 40 days 98.6 45 days Sales Receivables Payables Planned growth in sales of 40% The terms of trade will stay the same 36 36 36 Managing Working Capital EXAMPLE The effect of a growth in sales on working capital when the terms of trade stay the same Year 1 Year 2 Growth Each element of working capital grew by 40% 000's Ratio 000's 1,000 100,000 1,400 COGS 800 70,000 1,120 Gross Profit 200 10,328 280 Gross Profit% 20% 14,384 20% Inventory 87.7 40 days 122.8 40 days 40% 109.6 40 days 153.4 40 days 40% 98.6 45 days 138.0 45 days 40% Sales Receivables Payables Ratio If the terms of trade stay the same the elements of working capital will grow in harmony with sales 37 37 37 Managing Working Capital EXAMPLE The effect of a growth in sales on working capital when the terms of trade change Year 1 000's Sales Year 2 Ratio 000's Growth OR Ratio Growth Ratio 1,000 1,400 COGS 800 1,120 Gross Profit 200 280 Gross Profit% 20% 20% Inventory 87.7 40 days 122.8 40 days 40% 154.4 50 days 74% 109.6 40 days 153.4 40 days 40% 172.6 45 days 57% 98.6 45 days 138.0 45 days 40% 168.8 55 days 71% Receivables Payables 38 38 38 Managing Working Capital EXAMPLE Effect of a growth in sales on working capital when the terms of trade change Year 1 000's Sales Year 2 Ratio 000's Growth OR Ratio Growth Ratio 1,000 1,400 COGS 800 1,120 Gross Profit 200 280 Gross Profit% 20% 20% Inventory 87.7 40 days 122.8 40 days 40% 154.4 50 days 74% 109.6 40 days 153.4 40 days 40% 172.6 45 days 57% 98.6 45 days 138.0 45 days 40% 168.8 55 days 71% Receivables Payables If the terms of trade change the elements of working capital do not grow in harmony with sales A change in the terms of trade is not caused by a growth of sales. There must be another reason 39 39 39 Cash flow and Capital Budgeting Approaches and Decision Rules 40 USES OF BREAK-EVEN ANALYSIS Determine at what level of sales the business is able to cover its fixed costs Determine level of profits at various possible levels of sales Helps to make a decision whether to increase price or sales volumes If sales fall, at what level does the company make a loss If the business borrows to make investments, how much must sales increase to cover the additional debt service 41 BREAK-EVEN POINT Breakeven Gross profit 52% Fixed costs Profits 42 Using Break-Even Point Analysis First step – understand the nature of costs Fixed costs Variable costs: Not directly related to sales / output Vary directly with sales / output Care, some are a bit of both! 43 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS Using break-even analysis Sales 3000000 2500000 Profit Margin of safety Total costs 2000000 Break-even 1500000 Loss 1000000 Fixed costs 500000 Most recent trading year 44 Uses of Break-Even Analysis: Recap Determines at what level of sales the business is able to cover its fixed costs Determines level of profits for various levels of sales Helps to make a decision whether to increase the price or sales volumes If sales fall, at what level does the company make a loss If the business borrows to make investments, how much must sales increase to cover the additional debt service 45 BREAK-EVEN ANALYSIS Using break-even analysis: What does it tell us about the business? Low break-even point: Profitable at low sales (safety) High break-even point: The opposite Low investment type of business Most of cost is variable (can be turned off) Flexible and responsive Dependant on external suppliers 46 USING BREAK-EVEN ANALYSIS Consider where the break-even point occurs: High break-even – the business very vulnerable Normal break-even - the business is less vulnerable Low break-even - the business is not vulnerable 47 PRESENT VALUE 48 NET PRESENT VALUE The difference between the market value of a project and its cost Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Valuation: – The first step is to estimate the expected future cash flows. – The second step is to estimate the required return for projects of this risk level. – The third step is to find the present value of the cash flows and subtract the initial investment. 49 NPV – DECISION RULE If the NPV is positive, accept the project A positive NPV means that the project is expected to add value to the firm and will therefore increase the wealth of the owners. Since our goal is to increase owner wealth, NPV is a direct measure of how well this project will meet our goal. 50 COMPUTING NPV FOR THE PROJECT You are looking at a new project and you have estimated the following cash flows: – Year 0: CF = -165,000 – Year 1: CF = 63,120; – Year 2: CF = 70,800; – Year 3: CF = 91,080; Your required return for assets of this risk is 12%. NPV = 63,120/(1.12) + 70,800/(1.12)2 + 91,080/(1.12)3 – 165,000 = 12,627.42 Do we accept or reject the project? 51 DECISION CRITERIA TEST - NPV Does the NPV rule account for the time value of money? Does the NPV rule account for the risk of the cash flows? Does the NPV rule provide an indication about the increase in value? Should we consider the NPV rule for our primary decision criteria? 52 NET PRESENT VALUE Investment Returns Original Investment 100,000 Rate Year 1 100,000 20% 20,000 Year 2 100,000 20% 20,000 Year 3 100,000 20% 20,000 Year 4 100,000 20% 20,000 Year 5 100,000 20% 20,000 53 53 NET PRESENT VALUE 54 54 NET PRESENT VALUE The closing balance should be 248,832 if compound interest is used. If a flat rate is used the balance will be only 200,000 - a significant difference! If you introduced flat rates in your bank it would not be long before the complaints started to roll in! As illustrated above if the return is 20,000 each year, the rate falls dramatically and in the last year it is only 9.6%. This makes it difficult to assess the true value of future incomes, i.e. project returns which are usually stated in today's values. This means that future incomes must be adjusted to take account the time value of money. This can be achieved by calculating the cost of the capital used in the investment and adjusting the return. The method commonly used is net present value. 55 55 NET PRESENT VALUE The term present value refers to the present value of an amount of money that will be received at some time in the future. So, if you expect to receive EUR 1,191 three years from now what will it be worth in today's values? The present value of this EUR 1,191 is equal to the amount of money now that you must invest so that you will get EUR 1,191 at the end of the three-year period. When the interest rate is known, you can then determine how much you must invest. Present values can be calculated by discounting. The formula for Present value is: Where: P0 = Present value at time Pn = Principal value at the end of any year n i = interest rate, also known as the discount rate n = duration of the period, number of years 56 56 NET PRESENT VALUE As an example, assume you will receive an amount of EUR 1,191 three years from now. What is the present value of this EUR 1,191 when the interest rate or the discount rate is at 6% per year? In this case when: I = 0.06; P3 = 1,191 and n = 3 years Present Value = P0= 1,191/(1+0.06)3 Therefore, the present value is EUR 1,000. In the same way, it is possible to discount the future incomes for an investment. A business is planning to make an investment of EUR 100,000. The total costs for production using the machine are expected to be EUR 5,000 each year. The incomes generated by the machine are expected to be EUR 30,000 and therefore the net annual cash flow is expected to be EUR 25,000 (see Table 4-6: Example - incomes generated by an investment of 100,000 (1)). 57 57 NET PRESENT VALUE 58 58 NET PRESENT VALUE 59 59 NET PRESENT VALUE 60 60 INTERNAL RATE OF RETURN Definition: IRR is the return that makes the NPV = 0 Decision Rule: Accept the project if the IRR is greater than the required return This is the most important alternative to NPV – Often used in practice – Intuitively appealing – Based entirely on the estimated cash flows and is independent of interest rates found elsewhere Compute using trial and error process 61 NPV VS. IRR NPV and IRR will generally give us the same decision Exceptions – Non-conventional cash flows – cash flow signs change more than once – may be several IRRs – Mutually exclusive projects • Initial investments are substantially different • Timing of cash flows is substantially different Whenever there is a conflict between NPV and another decision rule, you should always use NPV 62 TIME VALUE OF MONEY - NET PRESENT VALUE The value of money decreases over time. This is because of interest. For example, EUR 1,000 invested for one year at an interest rate of 5% would be worth EUR 1,050 after 12 months. That means that an investor would expect higher incomes in future years from the same investment. So, in this example EUR 1,050 earned in one year’s time has only the same value as EUR 1,000 income earned today. Clearly, the effects of inflation should also be considered. 63 TIME VALUE OF MONEY - NET PRESENT VALUE The value of money decreases over time. This is because of interest. For example, EUR 1,000 invested for one year at an interest rate of 5% would be worth EUR 1,050 after 12 months. That means that an investor would expect higher incomes in future years from the same investment. So, in this example EUR 1,050 earned in one year’s time has only the same value as EUR 1,000 income earned today. Clearly, the effects of inflation should also be considered. 64 Financial management framework in a public enterprise 65 EFFICIENT PUBLIC FINANCE MANAGEMENT 66 UNDERSTANDING THE PUBLIC SECTOR FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT CYCLE 67 UNDERSTANDING THE PUBLIC SECTOR FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT CYCLE It is essential than in the past for there to be effective implementation processes for public sector financial management and service delivery. This is a continuous process of planning, implementation, evaluation, audit and improvement based on the outcomes – in other words, as a financial management cycle in which: Earlier steps lead logically to later steps during the financial year At the end of the process internally (and, from the auditors, externally) evaluation and review whether or not what was planned was actually delivered and how it might be done better in future. 68 UNDERSTANDING THE PUBLIC SECTOR FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT CYCLE The key stages in the cycle are: Budgeting and service planning – what the organization plans to do and how it allocates the necessary resources to make service delivery possible. This is based on a combination of corporate objectives and resources and project and activity budgeting and planning i.e. where top-down meets bottom-up Operational performance management – ensuring that planned service outcomes are actually achieved Budgetary control and integrated financial management – confirming that planned service outcomes are achieved within allocated budget Evaluation – internal review of how processes and outcomes can be improved Audit – external verification and also independent advice on how processes and outcomes can be improved. 69 Main principles and Rules of financial management in an SOE 70 TOOLS FOR FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT IN STATE OWNED COMPANIES A. Tools For Financial Planning B. Tools for Financial Implementation C. Tools for Financial Reporting and Analysis 1. Revenue Forecasting 7. Financial Performance Monitoring 9. Financial Reporting and Analysis: The Statement of Net Assets and the Statement of Net Position 2. Resource Development Analysis 8. Cash Management: Determining the Optimal Cash Balance 10. Financial Reporting and Analysis: Statement of Activities 3. Cost Estimation 11. Financial Reporting and Analysis: Fund-Level Statements 4. Cost Comparison 12. Financial Conditional Analysis 5. Incremental Cost Analysis 13. Debt Capacity Analysis 6. Cost-Benefit Analysis 14. Financial Risk Assessment: Analysing the Risk of Revenue Loss 71 1 REVENUE FORECASTING Revenue forecasting helps financial planning. Because revenue determines service capacity, accurate revenue forecasting allows for a good understanding of an organization’s ability to provide services. Forecasting is also a process through which managers learn about their communities and organizations The Delphi technique is probably the most popular qualitative tool. It is a process in which a group of experts are individually questioned about their perceptions of future events that will affect the revenue flows. 72 1 REVENUE FORECASTING Quantitative forecast tools vary from simple smoothing techniques to sophisticated causal modeling Using the simple moving average (SMA) technique, we calculate the arithmetic average of revenues in previous forecast periods (“years” in this case) and use it as the forecast. SMA is very simple to understand and easy to use. But it has a major drawback—it weighs all previous revenues equally in averaging. In other words, it treats the revenue from ten years ago as if it is as important as last year’s revenue. Common sense says that we should place more weight on the more recent revenue. The exponential smoothing (EXS) technique assigns different weights to data of different periods. 73 1 REVENUE FORECASTING Utility Taxes in city XXXX Year Revenues ($) 1 842,387 2 1,665,430 3 1,863,296 4 2,063,103 5 2,905,717 6 2,994,785 7 3,281,836 8 3,766,661 9 3,907,110 10 4,063,555 11 ? Licenses, Permits, and Fees in city XXXX Year Revenues ($) 1 13,717,979 2 14,369,907 3 16,232,768 4 15,693,711 5 17,684,099 6 18,276,037 7 20,289,136 8 ? Franchise Taxes in city XXXX Year Revenues ($) 1 12,442,000 2 12,427,000 3 13,091,000 4 13,743,000 5 14,306,000 6 15,089,000 7 15 257 000 8 16,749,000 9 ? 74 2 RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT ANALYSIS Resource development analysis (RDA) applies to a fiscal condition where a significant revenue increase or expenditure cut is needed for a large revenue shortage foreseeable in the near future. Revenue shortages result from one of three conditions—a significant expenditure increase, a significant revenue loss, or both. It is important to note that RDA is necessary for large and persistent revenue shortages that could severely hinder an organization’s service quality and affect its financial viability. Small, temporary, or incremental revenue shortages may be dealt with by using financial reserves or other established financial practices, and RDA may not be necessary. For example, the shortage caused by annual employee salary raises to offset inflation can be covered by allocating a certain percentage of the budget for the increase, and no specific justification or analysis is needed. RDA consists of several steps: 75 2 RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT ANALYSIS Understanding the issue. In this step, a revenue shortage and possible causes of it are specified. Estimating the amount of the revenue shortage. Developing revenue options. Possible revenue options to deal with the shortage are developed. Assessing revenue options. Pros and cons of each revenue option are analyzed. Making decisions. Finally, a decision on which revenue option(s) is most feasible is made. 76 2 RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT ANALYSIS Estimating Revenue Loss Revenue loss is the amount of revenue decline between two fiscal periods. For example, if $500 is collected this year and only $400 is available for the next year, the revenue loss is $100. Revenue loss can be broadly defined as: Revenue Amount Before the Loss – Revenue Amount After the Loss. Estimating Expenditure Growth 77 2 RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT ANALYSIS Estimating Purchase Prices (or Cost). The focus of this estimation is on the purchase prices of expenditure (expense) elements such as personnel, operating, and capital expenditures. Estimation Based on Demographics. Expenditure growth is often caused by increasing public demand for services, and public demand can be measured by population growth. Estimation Based on Comparable Scenarios. This method is particularly useful when little reliable information on purchase prices or demographics is available. The essence of the method is to develop comparable spending scenarios. 78 2 RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT ANALYSIS DEVELOPING REVENUE OPTIONS Once the amount of a revenue shortage is determined, potential sources should be identified to cover the shortage. A common strategy to deal with the shortage is to cut spending. Spending cuts can effectively reduce the revenue shortage. Nevertheless, it will affect services and people. Also, it is often politically risky for public officials. The following can be used to increase revenues. Option 1: Increasing Taxes Option 2: Increasing User Charges Option 3: Borrowing Option 4: Intergovernmental Assistance Option 5: Use of Financial Reserves Option 6: Making Institutional or Policy Changes Option 7: Combination of the Above Options and a Summary 79 2 RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT ANALYSIS Example of Estimating Expenditure Growth Year Ten years ago Nine years ago Eight years ago Seven years ago Six years ago Five years ago Four years ago Three years ago Two years ago Last year Average Total expenditure Population Expenditure per capita ($) Expendisture per capita growth rate 162,491,969 162,424,561 173,379,035 185,168,296 190,753,923 197,103,191 229,163,984 229,551,667 261,833,073 258,881,807 168,456 169,675 172,019 170,780 170,307 173,122 176,373 180,462 184,639 188,013 964.64 957.27 1,007.91 1,084.25 1,120.06 1,138.52 1,299.31 1,272.02 1,418.08 1,376.94 −0.0076 0.0529 0.0757 0.033 0.0165 0.1412 −0.0210 0.1148 −0.0290 0.0418 80 2 RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT ANALYSIS Applicability of Revenue Options According to Activity Type Column1 Taxes User charges Borrowing Intergovernmental aids Financial reserves Institutional/policy changes Revenue shortage caused by Governmental activities Business-type activities Applicable Not applicable Not applicable Applicable Applicable Applicable Applicable Questionable Applicable Applicable Applicable Applicable 81 2 RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT ANALYSIS The Decision-Making Matrix for Revenue Options Ratings: 0 = Extremely unfeasible.….10 = Extremely feasible Column1 Description Column2 Options 1 Column3 Column4 2 3 Financial Merits Cost of the feasibility study Cost of the revenue design study Cost of administration and collection Sufficiency of revenue generated Revenue/cost ratio Political Merits Elected officials’ acceptance General public’s acceptance Business community’s acceptance Other interest groups’ acceptance Legal Feasibility Compliance with federal legal requirements Compliance with state legal requirements Compliance with local legal requirements Total score 82 7 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE MONITORING A financial monitoring system serves three purposes. First, it provides an ongoing check on the budget. By comparing actual financial results against budgets, it can be determined how well financial objectives have been achieved and whether the budget is realistic. Second, a monitoring system helps uncover inefficient practices and operations. Third, and perhaps most important, a monitoring system helps avoid further deterioration of financial condition. Financial performance monitoring is a system designed to detect undesirable financial performance and provide possible solutions to enhance performance. 83 7 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE MONITORING Three essential elements are needed in developing an effective financial monitoring system: 1. Indicators that assess financial performance 2. Techniques to detect unacceptable financial performance 3. Techniques to diagnose causes of underperformance and to provide suggestions for performance improvement 84 7 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE MONITORING Indicator 1: Total Revenues or Revenues Per Capita. The variations of total revenues include total revenues by fund and revenues by source ‘i.e., taxes, fees, charges, intergovernmental revenues’, which indicate the level of resources available for service provision. The percentage of a particular revenue source in total revenues can also be monitored to assess whether an organization over relies on the revenue Indicator 2: Total Expenditures or Expenditures Per Capita. One variation of total expenditures is the expenditures by function, such as personnel, operating, or capital expenditures. These indicators assess the level of resources consumed for service provision. The percentage of a particular expenditure in total expenditures can also be monitored to identify major expenditure items. Expenditures per capita ‘Total Expenditures/Population’ measures the resource consumption for each individual resident. 85 7 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE MONITORING Indicator 3: Liquidity. Liquidity evaluates whether an organization has enough cash and cash equivalents to meet its short-term obligations. Insufficient liquidity affects an organization’s financial viability. Excessive liquidity suggests a possible loss of investment opportunities. One common liquidity indicator is the current ratio ‘Current Assets/Current Liabilities’. 86 7 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE MONITORING Indicator 4: Net Assets or Change in Net Assets ‘i.e., Operating Surplus or Deficit’. Assets are what an organization owns, or more formally, the valuable resources in an organization. They include current assets described above and long-term ‘or noncurrent’ assets, such as land, buildings, and equipment. Liabilities are what an organization owes to others. In addition to current liabilities, there are long-term liabilities, such as long-term debts. Net assets are the difference between assets and liabilities. Indicator 5: Fund Equity ‘Balance’ or Fund Operating Surplus ‘or Deficit’. Operating deficits occur when expenditures exceed revenues, which indicates that an organization consumes more than it receives. The constant recurrence of deficits exhausts an organization’s reserves and puts its financial viability on the line. Deficits can occur in different funds of an organization. 87 7 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE MONITORING Indicator 6: Borrowing Capacity. Debt issuances can be used to finance capital improvement and occasionally short-term revenue shortages. However, excessive debts can cause serious financial troubles. How much debt is too much? Ratios used are: debt outstanding ratios and the debt service ratio. One indicator that also assesses debt capacity is a comparison of debt ‘i.e., debt outstanding’ with total assets ‘i.e., Total Debt/Total Assets’. Indicator 7: Asset Allocation Efficiency. One such indicator is the total asset turnover ‘Total Revenues/Total Assets’, which calculates the revenue per dollar of assets. It is an indicator of asset allocation efficiency. 88 7 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE MONITORING Revenues, Expenditures, and Surplus ‘Deficit’ in the Current Year ‘$’ Description Total revenues Total expenditures Surplus or deficit Actual 5,000,000 5,150,000 −150,000 Budget 4,900,000 4,600,000 300,000 Difference 100,000 −550,000 −450,000 Actual 2900000 1,100,000 1,150,000 5150000 Budget 2500000 1,000,000 1,100,000 4600000 Difference −400,000 −100,000 −50,000 −550,000 Expenditure by Function ‘$’ Description Personnel Operating Capital Total 89 9 FINANCIAL REPORTING AND ANALYSIS THE STATEMENT OF NET ASSETS AND THE STATEMENT OF NET POSITION Balance sheet information for a government as a whole (i.e., governmentwide) is reported in the statement of net position. The financial statement used to report annual revenues and expenses for a government as a whole is the statement of activities. We focus on the statement of net assets (net position) in this chapter and the statement of activities in the one following. The following Accounting Equation describes the Net Position Net Position = (Assets + Deferred Outflows of Resources) − (Liabilities + Deferred Inflows of Resources) Deferred outflow of resources is consumption of net assets that is applicable to a future reporting period instead of the current period. Deferred inflow of resources is an acquisition of net assets that is applicable to a future reporting period instead of the current period. 90 9 FINANCIAL REPORTING AND ANALYSIS THE STATEMENT OF NET ASSETS AND THE STATEMENT OF NET POSITION Statement of Net Position Comparison: City XXXX Column1 Assets Current assets Cash 1,500,000 Accounts receivable Inventory 690,000 Total current assets Fixed assets Land 3,000,000 Equipment, net Total fixed assets Total assets7,750,000 Deferred Outflows of Resources Total assets + deferred outflows Liabilities Liabilities Current liabilities Accounts payable Wages payable Total current liabilities Long-term liabilities Bonds payable Total liabilities Deferred Inflows of Resources Net Position Net investment in capital assets Unrestricted Restricted Total net position Total liabilities + deferred inflows + net position Column2 12/31/20×4 2,000,000 560,000 250,000 2,750,000 3,000,000 2,000,000 5,000,000 8,050,000 0 7,750,000 Column3 12/31/20×3 300,000 2,550,000 2,500,000 5,500,000 0 8,050,000 3,000,000 1,300,000 4,300,000 3,000,000 1,050,000 4,050,000 1,000,000 5,300,000 0 1,500,000 5,550,000 0 1,000,000 500,000 950,000 2,450,000 7,750,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 500,000 2,500,000 8,050,000 91 10 FINANCIAL REPORTING AND ANALYSIS: STATEMENT OF ACTIVITIES The financial statement that presents revenues and expenses is called the statement of activities. Like the statement of net assets (net position), the statement of activities presents the financial information for a government as a whole. Expenses First, expenses are classified and presented by functions or programs. For example, a city can present expenses in the major service functions of public safety, transportation, education, health, and human services. Revenues The sources of revenue are presented in the statement. In governments, revenue sources include taxes, fees and charges, grants, investment earnings, and other revenue sources. 92 10 FINANCIAL REPORTING AND ANALYSIS: STATEMENT OF ACTIVITIES Expenses, Program Revenues, Net (Expenses) Revenues, and General Revenues in the Statement of Activities: City XXXXX Function/Program Governmental activities General government Public safety Transportation Health and human services Total Business-type activities Water Sewer Parking Total Total primary government General revenues Taxes Property taxes Sales taxes Franchise taxes Grants not restricted for specific programs Investment earnings Miscellaneous Total general revenues Change in net position Net position—beginning Net position—ending Expenses (1) Program revenues (2) Net (expenses) revenues (2)−(1) 420,000 1,500,000 440,000 300,000 2,660,000 140,000 53,000 49,000 150,000 392,000 -280,000 -1,447,000 -391,000 -150,000 -2,268,000 150,000 210,000 120,000 480,000 3,140,000 180,000 300,000 60,000 540,000 932,000 30,000 90,000 -60,000 60,000 -2,208,000 1,250,000 320,000 230,000 260,000 43,000 55,000 2,158,000 -50,000 2,500,000 2,450,000 93 11 FINANCIAL REPORTING AND ANALYSIS FUND-LEVEL STATEMENTS A fund is a fiscal and accounting entity in which financial transactions of specific types of activities are recorded and reported. Two conditions must be met to construct a fund. – First, a fund is a fiscal entity in which assets are set aside for liabilities incurred in supporting specific activities of the fund. A fund reports its own assets, liabilities, and the fund balance, which is the difference between assets and liabilities. – Second, a fund is an accounting entity in which the double-entry mechanism must be used in recording transactions. The accounting equation for a fund can be expressed as: Assets = Liabilities + Fund Balance In the USA governmental funds include: – governmental funds – proprietary funds – fiduciary funds 94 11 FINANCIAL REPORTING AND ANALYSIS FUND-LEVEL STATEMENTS Assets Cash Accounts receivable Inventory Total Amount 225,000 84,000 0 309,000 Liabilities Accounts payable 175,000 Due to other funds 70,000 Total 245,000 Fund balance Reserved 13,000 Unreserved 51,000 Total 64,000 Total liabilities and fund balance 309,000 Revenues Property taxes Sales taxes Franchise taxes Intergovernmental revenues Investment earnings Fees and fines Total revenues Expenditures General government Public safety Transportation Health and human services Total expenditures Excess (deficiency) of revenues over expenditures Other financing sources (uses) Transfer in Transfer out Total other financing sources (uses) Net change in fund balances Fund balances—beginning Fund balances—ending Amount 1,150,000 320,000 230,000 300,000 38,000 24,000 2,062,000 255,150 1,317,500 311,850 296,900 2,181,400 -119,400 200,300 -100,000 100,300 -19,100 83,100 64,000 95 12 FINANCIAL CONDITION ANALYSIS Measuring Financial Condition Financial condition (also known as economic condition’ is defined as the ability of an organization to meet its financial obligations. During the process of providing goods and services, an organization incurs financial obligations in the form of expenses, expenditures, and debt that must be paid sooner or later. If the organization can pay these obligations without incurring much financial hardship, we say that the organization’s ability to pay is high and the organization is in good financial condition. 96 12 FINANCIAL CONDITION ANALYSIS 97 12 FINANCIAL CONDITION ANALYSIS 98 12 FINANCIAL CONDITION ANALYSIS 99 The anatomy of financial statements and how to read them 100 WHAT IS PUBLIC FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT? A public financial management (PFM) system is a set of rules and institutions, policies, and processes that govern the use of public funds across all sectors, from revenue collection to monitoring of public expenditures. PFM policies vary by country and can cover issues related to tax law, budget management, debt management, subsidies, and state-owned enterprises. A wellfunctioning PFM system is critical to ensuring accountability and efficiency in the use of public financial resources, while a weak PFM system can result in significant wastage of scarce resources (Figure 1). 101 COMMON SIZE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS One of the most useful ways for the to look at the company’s financial statements of a small business is by using “common size” financial statements and ratios. Common size statements and ratios can be developed from both balance sheet and income statement items. For example, each of the items on the income statement would be calculated as a percentage of total sales. (Divide each line item by total sales, then multiply each one by 100 to turn it into a percentage.) Similarly, items on the balance sheet would be calculated as percentages of total assets (or total liabilities plus owners’ equity). 102 COMMON SIZE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Example: If you want to evaluate the cash position compared to the cash position of one of the key competitors, you need more information than, say, the business has Birr 12,000,000 and typical competitors have Birr 22,000,000. That’s a lot less informative than knowing that the business’s cash is equal to 7% of total assets, while the competitor’s cash is 9% of their assets. Common size ratios make comparisons more meaningful To calculate common size ratios from the balance sheet, simply compute every asset category as a percentage of total assets, and every liability account as a percentage of total liabilities + equity. 103 COMMON SIZE BALANCE SHEET 104 COMMON SIZE PROFIT & LOSS 105 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 106 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 107 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 108 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 109 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 110 Financial statement Analysis (Ratio Analysis) 111 FINANCIAL RATIOS Financial Ratios are mathematical indicators that will: Compare Company A’s results of operations over time; e.g. 2018 -2019 - 2020 Compare Company A’s results compared to Company B’s results Compare Company A’s results compared to Industry (its competitors) Identify areas of strengths and weakness 112 Financial Ratios Analysis 113 WHAT CAN FINANCIAL RATIOS MEASURE? 1. Trading Profitability 2. Operational Performance 3. Liquidity and Working Capital 4. Return(capital) 5. Cash Flow Performance 6. Risk (Debt & solvency) 114 Trading Profitability 115 TRADING PROFITABILITY Gross Profit Margin: Gross Profit X 100 Sales a. What are the usual margins for the particular trade or industry? b. Variations may be caused by: (i) Changes in input and sales prices, e.g. price cutting, offering early payment discounts. (ii) Inventory losses due to mark down or pilferage. (iii) Alterations in the basis for inventory valuations (iv) A change in the types/numbers of products sold (product mix) (v) Offering discounts for volume sales (vi) Manufacturing wages (vii) Poor buying (viii)Poor quality control (ix) Increased competition (ix) Failure to pass on higher production costs 116 TRADING PROFITABILITY Operating Profit Margin: Operating Profit (EBITDA) X 100 Sales Companys should be able to exercise a high level of control over expenses and overheads. Positive and negative trends in this ratio are usually directly attributable to management decisions. A Company's operating income (rather than the net profit) is often the preferred metric for making inter-Company comparisons since it is seen to be more reliable basis for comparing operating business performance. This is because it ignores levels of borrowing (interest costs), depreciation policies and differing tax charges. 117 PROFITABILITY Profit After Tax Margin (%): Profit After Tax (PAT) X 100 Sales Peer Company comparisons of net profit margins can be problematic because of different tax charges, depreciation, and interest costs. Year-on-year comparisons for the same Company are also affected by the same issues. This is one of the reasons that some analysts prefer to use the operating or pre-tax profit figures instead of the net profits for profitability ratio calculation purposes 118 2. Operational Performance 119 OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE 1. Sales Growth Ratio % This year's sales – Last years Sales X 100 Last years Sales Are sales growing/declining? What is the reason? Remember that sales are “price x volume”, therefore changes in sales can be due to changes of one or even both of these variables. What is the impact on working capital? If sales are growing the Company usually requires more working capital 120 OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE 2. Profit Growth Ratio % This year‘s PAT– Last years PAT X 100 Last years PAT When assessing the rate of growth consider the sales performance and the business need for profits to fund growth, dividends, and finance charges. 121 OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE: OTHER INDICATORS 3. Sales per employee Sales Headcount 4. Profit (PAT) per employee Profit (PAT) Headcount 5. Value Added per employee Value Added (Gross Profit) Headcount 122 OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE: OTHER INDICATORS 6. Fixed Assets Turnover Sales Fixed Assets 7. Average occupancy rate 8. Gross profit per square meter of display 123 2. Liquidity and Working Capital Ratios 124 LIQUIDITY AND WORKING CAPITAL Liquidity means having cash and access to cash Sufficient cash to meet the business’s current and near-term funding needs Working capital means Current assets minus current liabilities Sign of business’s ability to pay its bills and meet its other current obligations 125 LIQUIDITY RATIOS Current Ratio: Cash + Bank + Marketable Securities + Debtors+ Stock Short Term Liabilities • This ratio identifies whether a Company's short-term assets (cash, cash equivalents, marketable securities, receivables, inventory) are sufficient to pay off its short-term liabilities (bills payable, current portion of term debt, bank short term loan, accrued expenses, taxes). • In theory, the higher the current ratio, the better--there are cases where this can be misleading. In particular, consider the length of time required to turn current assets (accounts receivable and inventory) into cash – The Cash Conversion Cycle 126 LIQUIDITY RATIOS Quick Ratio Cash + Bank + Marketable Securities + Debtors Liabilities Short Term • This ratio gives an indication of the ability of the business to pay current liabilities from cash or near-cash items. • In other words, whether there is a need for inventory sales to meet urgent bills. • The quick ratio should also be compared with the current ratio. If the current ratio is significantly higher, it indicates that a significant proportion of Company's current assets are inventory and/or other less liquid items and that liquidity might be an issue 127 LIQUIDITY RATIOS Cash Ratio Cash + Bank + Marketable Securities Short Term Liabilities Why hold some assets in the form of cash? - For day-to-day trading purposes: Some of this may need to be in cash to pay rent, rates, fuel bills, tax, and/or interest. - As an ‘insurance’ against cash-flow problems: It may need a cash ‘buffer’ to ensure that it does not exceed the short-term loan limit at particular times in the year. - To take advantage of opportunities that may arise. There may be ‘bargains’ like early payment discounts or the Company may wish to secure short-term investments that offer high profitability. 128 LIQUIDITY RATIOS Liquid Surplus/Sales Ratio Liquid Surplus (Current Assets-Current Liabilities) X 100 Sales As sales increase, the liquid surplus ought to increase in harmony with it. The ratio ought to stay the same. If not, this may indicate that as sales increase the business needs to borrow more money. 129 3. Return Ratios 130 RETURN RATIOS Return on Assets (ROA) Profit Before Tax X 100 Average Total Assets An Company engaged in capital-intensive businesses (e.g. heavy engineering), using a large asset base will have a lower ROA than noncapital intensive businesses that have a small investment in fixed assets. As a rule of thumb, analysts like to see that a company's ROA is no less than 5%. 131 RETURN RATIOS Return on Equity _ Profit Before Tax X 100 _ Average Total Shareholders Equity (Net worth) The higher the ratio, the better There is however a weakness with this ratio. It may be disproportionately high if the Company borrows money heavily to fund business expansion rather than use shareholders equity 132 4. Debt and Solvency Ratios 133 RISK AND SAFETY Aspects to consider: How much money have the owners invested in the business? Are there any hidden reserves that would increase this figure? (e.g., a building last valued 35 years ago). What is the total of net assets? Are net assets increasing or decreasing? What has caused the increase/decrease? Consider the quality of the assets. Are they worth the figures stated? Are there any contingent liabilities? These will increase the level of borrowings. Are there any permanent directors’ loans? Quasi capital?? 134 SOLVENCY AND LEVERAGE Debt Ratio (%) = Total Liabilities X 100 Total Assets < 60-70% > 70% The higher the ratio, the more risk that Company is considered to have taken on. 135 SOLVENCY AND LEVERAGE Gearing Ratio % = Total Borrowing X 100 Owners’ Equity (Net Worth) < 100% > 100% Potential Gearing Ratio % = Total Borrowing Agreed X 100 Owners Equity (Net Worth) Reasons for an increase in gearing: Borrowings have increased; The owners’ investment has declined, usually after losses or capital withdrawals (e.g., dividends). 136 SOLVENCY AND LEVERAGE Interest Cover Ratio % (Profit Basis): = Profit Before Interest Paid (PAT + Interest) X 100 Interest Paid 137 EXERCISE: THOUGHTS ON MAX LTD’S RATIOS AGAINST INDUSTRY AVERAGE Have a look at Max Ltd’s ratios against industry averages. Type summary paragraph summary (max 150 words) on your thoughts on the performance of the company. Post your summary on the chat of the Teams Meeting 138 RATIO ANALYSIS: ASPECTS TO REMEMBER Risk or Safety Surplus (Net Assets) Hidden Reserves/Deficits Gearing Interest Cover (ICR) Debt Service Cover (DSCR) Ratio Analysis Trend Analysis Profitability Sales Is there a profit? From where? Is it retained or distributed? Gross & Net Profit Ratio Depreciation Director’s Remuneration Liquidity and Cash Flow Cash Flow generation Net Operating Cash Flow (NOCF) Cash Conversion Cycle Debtors/Creditors/Inventory Liquid Surplus/Deficit Trends Other Factors Are the figures audited by a reliable auditor? Schedule of Fixed Assets Capital Commitments Extra ordinary items Contingent Liabilities 139 RATIOS: OVERALL QUESTIONS TO ANSWER Is the business protected from unnecessary risks? (e.g. over trading/cash flow problems) Is the business growing and becoming a more efficient? Is the business meeting its objectives (e.g., increasing sales, increasing profits by 50%, etc.)? Are the performance measures up compared to the month/year before (e.g. Is there a trend of growth/improvement in performance)? How liquid is the business and how solvent is it? How does the business compare to others: - Competitors - Similar businesses and - Industry norms 140 RATIOS ANALYSIS - CONCLUSION Alone ratios can be quite meaningless. They need to be: Understood; Consistently calculated and used; Compared over periods of time (trend); Compared to other similar businesses (benchmark); Compared to the industry as a whole (norms). Competitor and industry information is often available from: Customers (at branch level); The bank head office; Professional financial databases; Periodic industry reports. 141 RATIOS: SHORTCOMINGS Ratios largely look at the past, not the future. It may be possible to make assumptions about future performance using ratios; Inventory valuations - different Companies use different methods to value their inventory. This can affect the accuracy of Company comparisons; Depreciation - Companies use different depreciation methods; Information about comparable businesses and an industry sector is not always available; Ratios focus on numbers. They should be used in conjunction with a sound nonfinancial analysis of the factors that affect financial performance, e.g. economic situation, level of competition, product quality, customer service etc Window Dressing – Financial information can be “manipulated” in several ways to make the figures used for ratios more attractive thus unreliable for analysis. 142 Mergers and Acquisitions 143 DEFINITIONS Merger: One firm absorbs the assets and liabilities of the other firm in a merger. The acquiring firm retains its identity. In many cases, control is shared between the two management teams. Transactions were generally conducted on friendly terms. In a consolidation, an entirely new firm is created. Mergers must comply with applicable state laws. Usually, shareholders must approve the merger by a vote. Acquisition: Traditionally, the term described a situation when a larger corporation purchases the assets or stock of a smaller corporation, while control remained exclusively with the larger corporation. Often a tender offer is made to the target firm (friendly) or directly to the shareholders (often a hostile takeover). Transactions that bypass the management are considered hostile, as the target firm’s managers are generally opposed to the deal. 144 MERGER NEGOTIATIONS Friendly Acquisition: The acquisition of a target company that is willing to be taken over. Usually, the target will accommodate overtures and provide access to confidential information to facilitate the scoping and due diligence processes. Hostile Takeover: A takeover in which the target has no desire to be acquired and actively rebuffs the acquirer and refuses to provide any confidential information. The acquirer usually has already accumulated an interest in the target (20% of the outstanding shares) and this preemptive investment indicates the strength of resolve of the acquirer. 145 • Target: the corporation being purchased, when there is a clear buyer and seller. • Bidder: The corporation that makes the purchase, when there is a clear buyer and seller. Also known as the acquiring firm. • Friendly: The transaction takes place with the approval of each firm’s management • Hostile: The transaction is not approved by the management of the target firm. 146 TYPES OF MERGERS Horizontal Mergers Between competing companies Vertical Mergers Between buyer-seller relation-ship companies Conglomerate Mergers Neither competitors nor buyer-seller relationship Reverse Mergers A reverse merger is a merger in which a private company may go public by merging with an already public company that often is inactive or a corporate shell. April 2013 147 SYNERGY The most used word in M&A is synergy, which is the idea that by combining business activities, performance will increase, and costs will decrease. Essentially, a business will attempt to merge with another business that has complementary strengths and weaknesses. Mv (A) + Mv(B) < Mv(AB) Financial Synergy: Borrow in Bulk : get better rates (borrowing interest rates) Save in Bulk : get better rates (deposit saving rates) Diversification of Risk : more companies in portfolio , less systemic risk. Offsetting tax losses. 148 SYNERGY Revenue Synergy : Market power , larger company will attract more customers (more brand awareness) Complementary products Reduce competition Bulk discounts : be able to attract better prices Market efficiency : one entity doing advertisements instead of two Reduced fixed overhead costs : overlapping departments and resources April 2013 149 MERGER FINANCING HOW THE DEAL IS FINANCED Cash Transaction – The receipt of cash for shares by shareholders in the target company. Share Transaction – The offer by an acquiring company of shares or a combination of cash and shares to the target company’s shareholders. Going Private Transaction (Issuer bid) – A special form of acquisition where the purchaser already owns a majority stake in the target company. Leveraged buyouts – In a LBO a buyer uses debt to finance the acquisition of a company (usually LBOs are a way to take a public company private, or put a company in the hands of the current management, MBO). 150 PURCHASE OF ASSETS & LIABILITIES The most common form of merger and acquisition involves purchasing the stock of the merged or acquired concern. An alternative is to purchase the target company’s assets. If the acquirer buys all the target’s stock, it assumes the seller’s liabilities (successor liability). In cases in which a buyer purchases a substantial portion of the target’s assets, the courts have ruled that the buyer is responsible for the seller’s liabilities (de facto merger). April 2013 151 HISTORY OF MERGER WAVES 1st wave 1895-1905 Horizontal mergers End with the passage and enforcement of antitrust legislation. 2nd wave 1920-1929 Vertical mergers Ends with stock market crash. 3rd wave 1960-1971 Conglomerate mergers Ends with recession and oil shocks of early 1970s. 4th wave 1982-1989 Hostile takeovers, LBOs, MBOs Ends with recession of late 1980s 5th wave 1993-2000 Stock-based friendly mergers May have ended with the burst of internet bubble 1992-1999 Strategic Mergers Very large in size and number 1998: over $1.5 trillion in deals Driven by: Deregulation, economic forces, technology, globalization Most done in cash (unlike 1980s) EXAMPLES •Deutsche Bank – Bankers Trust Citicorp – Travelers Insurance (Reigle –Neal 1994, Bliley Act 1999) AOL – Netscape 152 THANK YOU FOR YOUR ATTENTION! 153