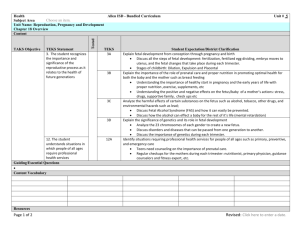

[Incredibly Easy! Series®] Lippincott Williams & Wilkins - Maternal-neonatal nursing made incredibly easy! (2015, Wolters Kluwer LWW) - libgen.lc

advertisement

![[Incredibly Easy! Series®] Lippincott Williams & Wilkins - Maternal-neonatal nursing made incredibly easy! (2015, Wolters Kluwer LWW) - libgen.lc](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/025899433_1-98aaaefeee144da05c3c92e117716113-768x994.png)