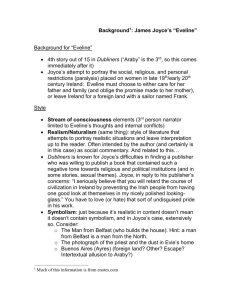

Batool 1 Sabahat Batool Academic Writing Dr. Ruth Wishart 28.04.2022 Desire for Escape in “Eveline” and “The Dead” Dubliners, a collection of short stories by James Joyce, illustrate the socioeconomic realities of early nineteenth-century Ireland. These stories represent Joyce's perspective on Irish life. Joyce presents the theme of desire of escape in his stories. In Dubliners, Eveline is the most mature character who is fulfilling her duty after the death of her mother. Joyce paints a gloomy picture of the secluded lives of women in Dublin in the nineteenth century. Eveline adopts a motionless position, symbolizing the bleakness of Joyce's overarching critique on Dublin society. Her struggle is told in a one-of-a-kind story told in thirdperson and in a stream-of-consciousness style. . The protagonist's literal and mental conflict between her obligation to stay and her longing for freedom is best shown through Eveline's point of view. The story explores Eveline's views and desires through peering into her mind, which propels the plot along. The story's lack of physical action is overshadowed by Eveline's inability to move, her psychological and spiritual immobility. The window, the persistent dust, and Eveline's departed mother's memories all show in the perspective. These folks represent Eveline's personal struggle as well as Dublin as a whole. She is trapped in her responsibility and she desires to flee her life of responsibilities. She is paralyzed by strong memories of her past and home that she is unable to board the ferry. Eveline's mental and physical immobility is revealed by the importance of a third-person narrative paired with the stream of consciousness style. In Joyce's story, the protagonist is depicted from a far, as though he were sitting across the room from Eveline. When Eveline begins to reflect about the innocence that was so important in her youth, the voice enters her consciousness. He comments on her physical description and certain characteristics of her immediate surroundings, but the voice enters Eveline's mind when she begins to reflect about the innocence that was so important in her upbringing. Eveline's time Batool 2 spent in front of the window is a type of subconscious imprisonment as well as a breach of her right to live a free life. Eveline engages physically and intellectually with 'windows' and 'dust' throughout the narrative. The window symbolizes the separation of residential space from the outside world. Eveline's repressed personality and the window's anticipatory sign create a delicate contrast of hope and despair. “She sat at the window watching the evening invade the avenue. Her head was leaned against the window curtains and in her nostrils was the odour of dusty cretonne. She was tired.”(Joyce.29). And again Joyce says, “Her time was running out but she continued to sit by the window, leaning her head against the window curtain, inhaling the odour of dusty cretonne.” (Joyce.32) Eveline is still enslaved by her mother's and life's memories, as well as the opportunities she has yet to seize. She is constantly thinking about her family, particularly her father. Joyce expresses herself. “Still they seemed to have been rather happy then. Her father was not so bad then; and besides, her mother was alive. That was a long time ago; she and her brothers and sisters were all grown up her mother was dead.” (Joyce.29) The dust that gathers on the curtain symbolizes the passage of time as a result of constant bodily action. This is strikingly close to Eveline's position; the dust reminds her of her own 'paralysis' and inability to move for an extended period of time. The window and the dust accumulation together represent Eveline's pessimism in ever seeking out what lies beyond the window, for she herself "inhales" and endures the dust that surrounds her. Joyce laments her tainted nostalgia for the dust that engulfs her belongings. “Home! She looked round the room, reviewing all its familiar objects which she had dusted once a week for so many years, wondering where on earth all the dust came from. Perhaps she would never see again those familiar objects from which she had never dreamed of being divided.”(Joyce, 29) Eveline's existence is supported by dull and repetitive tasks such as dusting her surrounds. Dusting and material dust prevent her from pursuing a career outside the home. The passage's point of view is important in depicting Eveline's psychological and spiritual bonds to household life, as well as her fear over probable escape. Eveline's difficulty to make a decision is sympathetically shown by Joyce since it has little to do with her and much to do with leaving her family behind, as well as the promises she made to her mother, who is now deceased. Eveline Batool 3 yearns for escape, but she also struggles with the luxuries of her current life, which are linked to her history. Eveline generally thinks about her home and family throughout the story, but she rarely mentions Frank and how she feels about him: the small amount of information that readers do get reveals her genuine sentiments about Frank and their relationship. Eveline is torn between staying at home to care for her family and leaving to marry the guy she loves. Even though her life at home is monotonous and unhappy, she accepts to marry Frank but has reservations about it. Eveline not only has the desire to abandon her life in Dublin, but also the potential to break free from the confines of her monotonous existence. The reader gets a glimpse into Eveline's life and the difficulties she faces as a result of her father's lack of responsibility, which he avoids; He said that she used to squander the money, that she had no head, that he wasn’t going to give her his hard-earned money...She had to work to keep the house together and to see that the two young children...went to school regularly and got their meals..(Joyce,29) Eveline is forced to grow up quickly after her mother dies, and she feels bound to her family to stay because she has taken on this matriarchal position. Eveline is complacent, and while she fantasizes of a new life with Frank, she appears to be having difficulty carrying it out. The idea of leaving and starting a new life is exciting, but having to really leave her family and follow through gives the reader a better understanding of Eveline's mindset: despite her father's devastation and betrayal, she cannot bring herself to do the same to him. Eveline clings to the memories she has of her father when her mother was alive, despite the fact that he is emotionally abusive and an alcoholic. It's difficult for her to leave her father and siblings because of her empathy for them. One can also ask if she can't leave her father because of the promise she made to her mother, or if he's the last link she has to the pleasant memories she shared with her family before her mother died. Eveline also demonstrates to readers that, while her life of caring for her father and brothers isn't ideal, she isn't wholly unhappy: She is taking a step towards her new life by leaving her house to travel to the station to meet with Frank, but the time it took her to leave her house hints at the fact that she has already made up her mind. Eveline seemed to be persuading herself that fleeing with Frank is a great decision down at the dock. It's strange how both "Eveline" and "Araby" protagonists build themselves up to a heightened sense of transformation and happiness just to be disappointed after it's all gone. Even though Eveline Batool 4 recognizes that a new life and a fresh start await her outside of Dublin, she is unable to leave with Frank. She appears to be stuck on the dock and unable to move. She felt her cheek pale and cold and, out of a maze of distress… (Joyce, 33) Her distress awoke nausea in her body and she kept moving her lips in silent fervent prayer. It was impossible. Her hands clutched the iron in frenzy. Amid the seas she sent a cry of anguish…. She set her white face to him, passive, like a helpless animal. Her eyes gave him no sign of love or farewell or recognition. (Joyce, 34) It's evident today that her attempt to flee was motivated by her own predicament, not by Frank's. She does not completely set herself up for disappointment by not fully committing to the decision to go with Frank; nonetheless, she is aware that by not going, she must prepare herself for a lifetime of regret and reflection on her past. It's uncertain whether Eveline opted to stay with her father or if she was seeking to avoid more pain or sorrow in her relationship with Frank. She is clearly uncomfortable with her life at the moment, but not so much that she can do anything but fantasize about it. Eveline's stare out the window shows she desires more, but she is unable to commit to anything other than staying with her father and keeping her mother's pledge. We see her trapped in her own feelings, torn between her comforting existence and a life that could provide a fresh start for her and her sad father. Eveline sees this excursion as merely a means of getting away from her current situation; she does not envision herself ever escaping with Frank. The terrible ending, in which she waits at the dock “like a helpless animal,” is traditionally interpreted as another illustration of Dublin's paralysis and citizens' figurative death. Eveline, like so many of her companions in Joyce's short story collection, has made the "wrong" decision. Eveline, like our narrator in Araby, is dissatisfied with herself and her incapacity to take charge of her life and make her own decisions. She doesn't do anything throughout the novel, and her only action is a refusal to take action: leaving the country" Once again, we are introduced to a lonely, alienated character who is enslaved by life's limitations. Eveline, like Gabriel and Gretta in “The Dead,” clings to the past and the spirits that accompany it, allowing them to infiltrate their contemporary existence. Batool 5 “The Dead” Joyce begins his narrative, “The Dead," with the protagonist, Gabriel Conroy, and his wife, Gretta, attending a party. Gabriel strives to escape the routine of his existence, his failing relationship with his wife, and the reality of who he is throughout the novel; eventually, his attempts to reignite his relationship in the hopes of improving his life fail, just as every other character in Dubliners fails to escape. The story begins with Gabriel's arrival at the party, as well as his interactions with the other guests, as well as his inner thoughts and feelings. Gabriel's sense of superiority is evident early on in various occasions, the most notable of which being his speech. Gabriel believes he is smarter and superior to the other partygoers, and he fears making a fool of himself by referencing someone they are unfamiliar with, which is his greatest dread. Gabriel clearly keeps everyone at arm's length, even his wife, and doesn't try to strengthen these relationships until the very end, but even then, his attempt to connect with his wife is at best perfunctory. Roland Wagner writes: Gabriel is revealed to be both secure and insecure, the ‘generous’ and responsible husband...and the somewhat cold, anxious, and sexually uncertain lover. His insecurity is manifest in his self-absorbed, self-justifying and hypocritical feelings of superiority towards the guests... (448) He has no emotional connection to the people or the environment around him, but most importantly, he has no emotional connection to himself. Everyone he claims to be close to walks on eggshells around him and it's obvious that there are no real ties. He blames his wife for taking “three mortal hours to dress herself,” which could be misconstrued as a joke, but he is patronizing rather than amusing. His rude comments about his wife don't end there; he's outraged that Gretta "would walk home in the snow if she were allowed." Gretta’s demeanor toward the party guests, as well as her willingness to go through the snow, stand in stark contrast to Gabriel, who refuses to let down his guard for fear of being judged. Gretta does not come across as pretentious or arrogant, despite her guarded demeanor. Gabriel believes he is superior than others, but he is preoccupied with what others think of him. Gabriel’s friends and family members make him look dumb. Gabriel’s paralysis is caused by his arrogance and lack of emotional connection to others around him, including himself. Gabriel is continuously struggling with his self-identity, and he enables people' opinions to undermine and degrade his self-esteem. Batool 6 Gabriel’s self-consciousness and social anxiety have rendered him immobile. Even though it's not exactly what he wants to say, he struggles with what the correct thing to say is. Because he is always self-conscious and self-aware, yet incredibly pretentious, his struggle with how people perceive him is at the heart of his issues. He doesn’t want to make a fuss with Miss Ivors at dinner, but he can't help but brag about his career and travel to get away from the boring topics. Gabriel is caught between his desire for people to see him in a specific light and his internal struggle with his wife's cold demeanor during the party. We witness Gabriel constantly trying to prove his brilliance and worth to the many people at the party in Joyce's “The Dead”: “Gabriel is torn between haughty cultural superiority and underlying emotions of inadequacy, and he pushes this inner drama out onto the social world, which becomes a stage for his never-ending quest for self-affirmation” (Boysen 401). His public persona, which he displays to society, his wife, and even himself, gives him a false sense of adulation. Everyone seems to be looking forward to his arrival, and when we see him arrive to the party, he appears to be arrogantly anticipating everyone's excitement. This quality in him makes him seem a little haughty, and while it's good that he looks after Freddy Malins, the drunk, and the others, his true entitled nature emerges. What fascinates me about Gabriel is how quickly he dismisses every lady who stands in his way, such as Lilly or Miss Ivors. It's off-putting that he tries to silence Lilly with a lovely tip rather than apologizing for overstepping a boundary. Gabriel notices his wife standing at the top of the stairs; listening to someone sing “The Lass of Aughrim” and gazing sadly off into the distance as the party winds down. “The Lass of Aughrim” is described as “...a song depicting a misinterpretation between lovers as leading to their tragic separation, serves to reveal the lack of true intimacy and genuine love binding the Conroys, bringing about an emotional distance between them” in “The Lass of Aughrim” – Love, Tragedy, and the Power of the Past (Kapus 3). In “The Dead”, “The Lass of Aughrim” serves as an interpretive lens for addressing the weighty subject of a tragic death motivated by love, especially when such love has been hidden within the memory for years, Gabriel observes as his wife transforms from socialite to recluse as she withdraws into herself for the rest of the night until she reveals the story of Michael Furey. Gabriel notices his wife Gretta, who is listening to “The Lass of Aughrim” with grace and mystery in her attitude.(Kapus 3) Batool 7 A wave of yet more tender joy escaped from his heart and went coursing in warm flood along his arteries. Like the tender fire of stars moments of their life together, that no one knew of or would ever know of, broke upon and illumined his memory. He longed to recall to her those moments, to make her forget the years of their dull existence together and remember only their moments of ecstasy. For the years, he felt, had not quenched his soul or hers. Their children, his writing, her household cares had not quenched all their souls’ tender fire. (Joyce, 215) As they return to the hotel, Gabriel appears to be enjoying the fact that he and his wife are now alone, and he is riding the high he has built up of rekindling some kind of fire within their relationship. “She was walking on before him with Mr. Bartell D'Arcy, her shoes in a brown parcel tucked under one arm and her hands holding her skirt up from the slush. She had no longer any grace of attitude, but Gabriel’s eyes were still bright with happiness. The blood went bounding along his veins; and the thoughts went rioting through his brain, proud, joyful, tender, valorous.”(Joyce, 214). Gabriel daydreams about the moments he and his wife will share after they've arrived in their room. “Gabriel strove to restrain himself from breaking out into brutal language about the sottish Malins and his pound. He longed to cry to her from his soul, to crush her body against his, to overmaster her”. (Joyce, 218) Gabriel’s fantasies about his wife and his assertion of control over her have something wrong with them. His feelings aren’t about reciprocal love or even a tender yearning; instead, he wants to dominate her and is turned on by these thoughts of power; his thoughts and desires are completely and sexually selfish. It's as if he has a fantasy of dominating his wife and sees an opportunity to realize it, but these strange feelings are countered by his wife's aloofness and his inability to comprehend why she appears so distant. Gabriel's need to assert his authority, even over his wife, is evident once again. “Gretta’s story puts an end to the idea of Gabriel's ego and the consciousness with which he is confronted, and which he is unable to comprehend, or master,” Boysen writes. (411) As he observes his wife, he implements a strategy for restoring their relationship to its former state. Gabriel fantasizes about having sex with his wife and dominating her when they ride home in a cab. Gabriel yearns to be in charge of his wife, and Joyce's comments make readers question how far he would go to fulfill his dreams. Gabriel longs to make love to Gretta in their hotel room as he tries to rekindle the spark of his marriage with her. Gretta pulls away from her husband and collapses into the bed, crying and covering her face. She tells him that the song Batool 8 “The Lass of Aughrim,” which he used to sing while they were together, reminded her of Michael Furey, the guy she thought was the love of her life. Gretta tells Gabriel about how she was about to leave for Dublin and Michael, despite being very unwell, came to see her in the pouring rain in the dead of winter. She learned about Michael’s death after arriving in Dublin, and she believes that his last visit to her was a selfless gesture of love that cost him his life. Gabriel is deeply saddened as his wife cries herself to sleep; he considers how she has managed to keep her anguish and love for Michael hidden. Gabriel's embarrassment is compounded by the fact that he has been outdone by a dead man. So she had had that romance in her life: a man had died for her sake. It hardly pained him now to think how poor a part he, her husband, had played in her life”(Joyce, 222) He realizes now that there is much about their relationship he did not fulfill, and no matter how much effort he put into their relationship, he would never out do Michael Furey, who “had braved dead” for Gabriel’s wife (Joyce, 222) Gabriel revokes from his wife, stunned and hurt by the abrupt news that he is not her first love. Gabriel’s supposed realizations may be shocking or even strong, yet he has gained nothing and is left with nothing but himself. Gabriel’s enlightenment begins with him realizing that he is incapable of loving, and he sobs. He is unable to genuinely understand or empathize with his wife’s feelings, revealing his selfish nature in the process. He seeks comfort and indulges in self-pity by pondering his own coming mortality and what it would mean if he died having made no daring or significant contribution to this life. Gabriel considers a journey away from Dublin and his current predicament as he observes the snow, hoping to find something more interesting than his dull and miserable life. He snoozed while he watched the silvery, black flakes fall obliquely against the lamplight. The moment had arrived for him to go on his westward adventure. Gabriel may fantasize about leaving Dublin with his wife and rekindling their love, but he will never be able to totally escape the reality of his wife's anguish over her old lover and the truth that he can never measure up to Michael Furey. As Gabriel glances out the window at the cemetery and sees “all the live and the dead,” he understands that he cannot and will not change his actual nature. His spirit has arrived at the place where the enormous hordes of the dead reside. He was aware of their erratic and fleeting existence, but he couldn't comprehend it. His own individuality was slipping into an impenetrable grey realm. Gabriel’s paralysis is heightened by Joyce’s comparison of it to the cold, silent snow that has blanketed Dublin; Gabriel, like the snow, is frigid and his emotions are blanketed. Batool 9 Gabriel recognizes that Michael has won because he has escaped, whilst Gabriel is trapped and also knows that he has no idea who he is. All the forms of psychological paralysis shown in the previous...are masterfully mixed. Conroy is revealed to be so shy and emotionally befuddled that he is unable to exert himself in public or in personal relationships. Gabriel thinks that it’s better to walk bravely into that other realm, in the full flory of some emotion, than to wilt and wither dismally with age. This simply serves to highlight Gabriel's immobility. He realizes now that he has lost out on passionate love, and that his wife thinks of her dead lover when she lies next to him. Batool 10 Work Cited: Ben-Merre, David. “Eveline Ever After.” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 3-4, 2012, pp. 455–471., doi:10.1353/jjq.2012.0033. Boysen, Benjamin. “The Self and the Other: On James Joyce's A Painful Case and The Dead.” Orbis Litterarum, vol. 62, no. 5, Oct. 2007, pp. 394-418. EBSCOhost. Corrington, J. W. "The Themes of Corruption, Escape and Frustration in James Joyce's Dubliners." 1964. EBSCOhost Daronkolaee, Esmaeel Najar. “James Joyce's Usage of Diction in Representation of Irish Society in Dubliners: The Analysis of The Sisters and The Dead in Historical Context." Journal of International Social Research, vol. 5, no. 23, Fall 2012, pp. 169 Joyce, James. Dubliners. Penguin Books. 2000. Kapus, Allie J. “The Lass of Aughrim” – Love, Tragedy, and the Power of the Past,” The Kabod 3.3 (2017) Article 6. Liberty University Digital Commons Pecora, Vincent P. “The Dead and the Generosity of the Word.” PMLA, no. 2, 1986, pp. 233. EBSCOhost, doi:10.2307/462406 Wagner, C. Roland. “A Birth Announcement in The Dead (Special Dubliners Number).” Studies in Short Fiction, no. 3, 1995, pp. 447. EBSCOhost. Zennure Köseman. “Spiritual Paralysis and Epiphany: James Joyce’s Eveline and The Boarding House.” Gaziantep University Journal of Social Sciences, Vol 11, Issue 2, no. 2 2012, pp. 587-600. EBSCOhost.