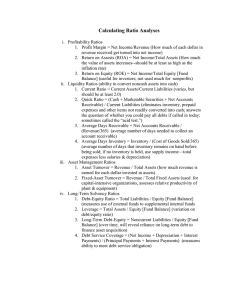

Chapter 3 Financial Statement Analysis Edited by Jerald James Guerrero Montgomery, CPA Original Lecture Notes by Mac Kerwin Lim, CPA Purpose of the Chapter: I. How analysts use historical financial statements in financial statement analysis. Calculate and interpret operating, credit, and investment ratios. Prepare a trend analysis of a company’s financial ratios. How analysts use financial statement analysis to help prepare a valuation forecast. The cautions analysts must consider when using financial statement analysis. INTRODUCTION TO FINANICAL ANALYSIS Financial Analysis requires the financial statements and ratios of a company to be compared, for example, with industry averages. Financial statement analysis is used to weigh and evaluate the operating performance of a firm. It accesses the profitability of the business firm, the firm’s ability to meet its obligations, safety of the investment in the business and effectiveness of management in running the firm. If you were to look at a statement of financial position or statement of comprehensive income, how would you decide whether the company was doing well or badly? Or whether it was financially strong or financially vulnerable? Financial analysis is therefore the practice of reviewing financial statements to answer these questions. It can be broken down into different types: 1. The horizontal analysis involves comparing one company’s financial statements directly with those of another similar company and considering why differences may be evident. For example, one company may have higher profit than another with similar revenue. A review of expenses may reveal that the company to have lower interest costs, which explain the difference. This may then be linked to the statements of financial position where more profitable company will have lower debt than the other company. 2. Trend analysis is a similar exercise, but this time involving a comparison of the financial statements of one company with those of the previous year. This form of analysis is useful in assessing the ongoing performance of a company, particularly when analysis relates to several years. 3. Ratio Analysis is the practice of analyzing amounts reported within the financial statements to calculate further values, which may add to the finding of basic horizontal or trend analysis. A ratio that should already be familiar to you is that of gross profit margin. The majority of this chapter relates to common ratios that may be calculated and what they mean. As with other forms of analysis, there must be some form of comparative or benchmark for ratios. This may be ratios calculated for a competitor, for the same company in previous years, or industry averages. Tools and techniques in analyzing financial statement. 1. HORIZONTAL ANALYSIS – involves comparing figures in two or more consecutive period. The difference between the figures of the two periods is calculated and the percentage of change from one period to the next, with the earliest period as the base. Example: 2017 2018 %change Sales 10,000 15,000 50% Increases are usually reflected with a positive % of change and decreases are usually reflected with a negative () % of change. a. Trend Analysis – a more advance form of Horizontal Analysis. Trend Analysis needs at least 5 – 10 years of experience in order to determine the trend for a particular account, unusual changes are not reflected in the trend. The firm will then compare the financial statement for a given year, based on the trend with that of the actual financial statement of the firm. Analysis: Net Income Decreases by 42.29% as a result of decrease in sales of 5%, though Cost of Goods Sold decreases by 1.49% it didn’t equal the decrease of 5% in sales (possible scenarios are: The volume of sale decreases and cost to produce one unit increases or Selling Price decreases as a result of decreasing the cost of goods sold) and Total operating expenses decreases by 3.49%. 2. Vertical Analysis – involves comparing figures in financial statements of a single period. The base for income statement is the revenue/sales and the base for balance sheet is the total assets/ total liabilities and equity. Vertical Analysis are effective when comparing two or more companies. Example: A firm’s salaries expense is 60% of revenue while another firm’s salaries expense is 70% of revenue. At the bottom of the analysis, note that net income, as a percentage of sales, declined by 2.62 percentage points (6.67 percent to 4.05 percent). As a dollar amount, net income declined by 14,096 (33,333 to 19,237). Management should consider both the percentage change and the dollar amount change. 3. Ratio Analysis – different ratios are computed to access the performance of the firm. Financial statement ratios are categorized into four (3). a. Liquidity ratios – allows the firm to measure its ability to pay its current obligations. b. Solvency ratios – allows the firm to measure its ability to pay long-term obligations. It assesses the firm’s ability to exist in the long run (going concern). c. Profitability/Efficiency ratios – allows the firm to measure its ability to earn an adequate return on sales, total assets and invested capital. It allows the firm to access if its capital is earning effectively through operations. Usually the firm’s rate of return is compared to a highest risk-free rate of return of an investment that is available in the market d. Investor Ratios Note: Within each heading, we will identify several standard measures or ratios that are normally calculated and generally accepted as meaningful indicators. Each business must be considered separately, however, and a ratio that is meaningful for a manufacturing company may be completely meaningless for a financial institution. It must be stressed that ratio analysis on its own is not sufficient for interpreting company accounts and that there are other items of information which should be looked at, for example: a) The content of any accompanying commentary on the accounts and other b) c) d) e) statements The age and nature of the company’s assets Current and future developments in the company’s markets, at home and overseas, recent acquisitions or disposals of a subsidiary by the company. Usual items separately disclosed in the statement of comprehensive income Any other noticeable features of the report and accounts, such as events after the end of the reporting period, contingent liabilities, a qualified auditor’s report, the company’s taxation position, and so on. Liquidity Ratios: 1. Current ratio – also called the working capital ratio, measures the number of times that the current liabilities can be paid with the available current liabilities. Working Capital = Current Assets – Current Liabilities Formula is: Current Assets Current Ratio = Current Liabilities Example: If Current Assets is 1,000,000 and Current Liabilities is 200,000. Then: Current Ratio = 1,000,000= 5 200,000 Which means that the current liabilities can be paid 5 times until the current assets are exhausted. Current Ratio roughly defines the short term debt-paying ability of the firm 2. Acid test ratio – also called the quick asset ratio, because not all asset can pay current liabilities, like prepaid expenses, quick asset considers only the part of current liabilities that are nearly converted into cash. The quick assets are: Cash and cash equivalent, trading securities and receivables. Formula is: Cash & Cash Equivalent + Trading Securities + Receivables Acid test ratio = Current Liabilities Example: If Cash is 150,000, Short term Investment is 200,000 and Accounts Receivable is 400,000 and Current Liabilities is 200,000. Then: Acid test ratio = 150,000 + 200,000 + 400,000 = 3.75 200,000 Acid test ratio is stricter than current ratio. Acid test ratio does not include inventory and prepaid expense, because inventory needs to be sold then collected first before it can be used to pay debts and prepaid expenses will never be converted to cash while short term investments can be immediately sold through active market and accounts receivable can be used to finance short term debt through pledging and factoring. 3. Working capital activity ratios – measures the turnover rate of working capital a. Receivable turnover – measures how fast cash is collected from receivable, it is presented in the unit (times), times meaning in a single year how many times does receivable be converted to cash. Formula is: Net Credit Sales Receivable Turnover = Average Receivable Average Receivable = Beginning Receivable + Ending Receivable 2 Example: If net credit sales is 500,000 and average receivable is 50,000. Then: Receivable Turnover = 500,000 = 10 times 50,000 b. Average Age of Receivable – at an average how many days will it take for accounts receivable before it is collected. Formula is: 365 days Average age of receivable = Receivable Turnover Example: In the previous example, Average Age of Receivable = 365 = 36.5 days 10 Which means that at an average, receivables are collected after 36.5 days c. Inventory turnover – measures how fast inventory is sold, meaning in a single year how many times inventories are purchased and sold. Formula is: Cost of Goods Sold Inventory Turnover = Average Inventory Average Inventory = Beginning Inventory + Ending Inventory 2 Example: if Cost of Goods sold is 300,000 and average inventory is 60,000. Then: Inventory Turnover = 300,000 = 5 times 60,000 d. Average Age of Inventory = at an average how many days will it take for the inventory to be sold. Formula is: 365 days Average age of Inventory = Inventory Turnover Example: In the previous example, Average Age of Inventory = 365 = 73 days 5 Which means that inventory are sold 73 days after purchase. Operating Cycle – The length of time raw materials are acquired, through production, sale of finished goods, until the time when receivables are collected or converted into cash which may in turn be used again to acquire raw materials. Formula is: Ave. Age of Receivable + Ave. Age of Operating Cycle = Inventory Example: If Average Age of Receivable is 36.5 days and Average Age of Inventory is 73 days then: Operating Cycle = 36.5 + 73 = 109.5 days Which means that if inventory are sold on credit, it takes 109.5 days for purchased inventory to be sold and ultimately collected e. Accounts Payable turnover – measures how fast payables are paid. Formula is: Net Credit Purchases Payables Turnover = Average Trade Payables Average Trade Payables = Beginning Payables + Ending Payables 2 Example: If Net Credit Purchase is 500,000 and Average Trade Payables is 200,000. Then: Accounts Payable Turnover = 500,000 = 2.5 times 200,000 f. Average Age of Trade Payables = at an average how many days will it take for payables to be paid. Formula is: 365 days Average age of Inventory = Inventory Turnover In the Previous Example, Average age of Inventory = 365 = 146 days 2.5 At an average it takes 146 days for accounts payable to be paid. Cash Conversion Cycle – The length of time for cash used to purchase inventory to be converted back to cash. Cash Conversion Cycle = Ave. Age of Receivable + Ave. Age of Inventory – Ave Age of Payable The acceptable liquidity ratios depend on the accepted standard of the entity but in no case should it be lower than one (1). A liquidity ratio of less than one indicates that the entity is no longer liquid. A very high liquidity ratio may indicate that the entity might not be utilizing its assets efficiently, to avoid underutilization of asset, the entity can either choose to expand their business, establish a new project or purchase long-term assets. Notes: 1. Current and quick ratios reveal a company’s ability to pay its debts as they fall due (LIQUIDITY). The efficient management of working capital revealed by efficiency ratios will contribute to a healthy liquidity position. 2. Liquidity is the amount of cash a company can put its hands on quickly to settle its shortterm debts (and possibly to meet other unforeseen demands for cash payments, too). Liquidity, therefore, involves the short term management of debts. 3. Liquid funds consists of: a) Cash b) Short term investments for which there is a ready market c) Fixed term deposits with a bank or other financial institution, for example, a six month high interest deposit with a bank d) Trade receivables e) Bills of exchange receivable 4. The cash cycle Solvency Ratios: Solvency is the ability of a company to manage its debt burden in the long run. Debt ratios are concerned with how much the company owes to its size, whether it is getting into more debt or improving its situation, and whether its debt burden seems heavy or light. a) When a company is heavily in debt, banks and other potential lenders may be unwilling to advance further funds. b) When a company is earning only a modest profit before interest and tax and has a heavy debt burden, there will be a very little profit left over for shareholders after the interest charges have been paid. And so, if interest rates were to rise (on bank overdrafts and so on) or the company as to borrow, even more, it might soon be incurring interest charges over EBIT. This might eventually lead to the liquidation of the company. These are the two BIG reasons why companies should keep their debt burden under control. 1. Times Interest Earned – Determines the company’s ability to cover its interest expense Formula is: Times Interest Earned = Income before interest and tax Interest Expense Example: Income before interest and taxes is 500,000 while interest expense is 250,000. Then: Times Interest Earned = 500,000 = 2 times 200,000 Times Interest Earned shows if your earnings are beings used up to pay interest. If a company has less than one (1) times interest earned, then the entities earnings are actually not enough to cover the interest of loans. If a company has low times interest earned (depends on the standard of the company) most operating income are used to pay interest. High times interest earnings is desired. 2. Debt-equity ratio or the Ratio of Debt to Equity Formula is: Debt-equity ratio = Total Liabilities Total Equity Example: If Total Liabilities is 300,000 and Total Equity is 100,000. Then: Debt-Equity Ratio = 300,000 = 3 100,000 Debt-equity ratio compares the ownership of creditors to the total asset, a very high debtequity ratio shows that if the entity is liquidated, most of assets are actually used to pay liabilities, while a minimal amount goes to the owner. 3. Debt Ratio – Indicates the percentage of total assets provided by creditors. Formula is: Total Liabilities Debt ratio = Total Assets Example: If Total Liabilities is 300,000 and Total Assets is 400,000. Then: Debt Ratio = 300,000 = 75% 400,000 Debt Ratio shows the percentage of ownership of creditors to the total asset, in the example in shows that 75% of the total asset belongs to the creditors 4. Equity Ratio – Indicates the percentage of total assets provided by the owners or stockholders. Formula is: Total Equity Equity ratio = Total Assets Example: If Total Equity is 100,000 and Total Assets is 400,000. Then: Equity Ratio = 100,000 = 75% 400,000 Equity Ratio shows the percentage of ownership of shareholders to the total asset, in the example in shows that 25% of the total asset belongs to the shareholders. Equity Ratio + Debt Ratio = 100% Profitability Ratio: 1. Return on Investment (ROI) ore Rate of Return It is impossible to assess profits or profit growth properly without relating them to the amount of funds or capital that were employed in making the profits. The most important profitability ratio is, therefore, returning on investment (ROI), which states the profit as a percentage of capital employed. Formula is: Rate of Investment = Net Income Investment Or ROI = (Current value of investment – cost of investment) / cost of investment 2. Return on Sales – measures the percentage of each peso revenue that results in net income Formula is: Net Income Return on Sales = Net Sales 3. Return on Asset – it measures how assets were efficiently used to produce the sales or revenue Formula is: Net Income Return on Asset = Average Total Asset 4. Return on Equity – measures the percentage of net income to capital Formula is: Net Income Return on Equity = Average Equity Or ROE = (Profit after tax and preference dividend)/ Equity shareholder’s fund 5. Return on Common Equity – measures the percentage of return to common equity after deducting the dividends for preference stock. Formula is: Net Income – Preferred Dividends Rate on Common Equity = Average Common Stockholders’ Equity 6. Basic Earnings Power Ratio - ratio is a measure that calculates the earning power of a business before the effect of the business' income taxes and its financial leverage. Formula is: Basic Earnings Power Ratio = Net Income Before Interest and Taxes Average Common Stockholders’ Equity 7. Earnings per share Formula is: Earnings per share = Net Income – Preferred Dividends Weighted Average Number of Common Shares Note: 1. Return on Investment (ROI) may be used by the shareholders or the Board to assess the performance of the management. 2. Earnings before taxation is generally thought to be a better figure to use than earnings after taxation because there might be unusual variations in the tax charge from year to year, which would not affect the underlying profitability of the company’s operations. 3. Another earnings (profit) figure that should be calculated is EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Tax). This is the amount of earnings that the company earned before having to pay interest to the providers of loan capital, such as loans payable and medium-term bank loans, which will be shown in the statement of financial position as non-current liabilities. 4. Using EBIT instead of operating income means that the ratio considers ALL income earned by the company, not just income from operating activity. This gives more complete picture of how the company makes money, therefore ignoring tax and interest expenses, and focus primarily on the company’s ability to earn from its operations. Formula to learn: Earnings before interest and tax is, therefore: A) The profit on ordinary activities before taxation; plus B) Interest charges on loan capital Example: Earning before tax Interest payable EBIT 2020 Earnings 342,130 18,115 360,245 2019 Earnings 225, 152 21,909 247,011 This shows a 46% growth between 2019 and 2020 5. Profit Margin. A company might make a high or low-profit margin on its sales. For example, a company that makes a profit of 25c per P1 of sales is making a bigger return on its revenue than another company making a profit of only 10c per P1 of sales. 6. Asset Turnover. Asset turnover is a measure of how well the assets of a business are being used to generate sales. For example, if two companies each have capital employed of P100,000 and Company A makes sales of P400,000 per annum whereas Company B makes sales of the only P200,000 per annum, Company A is making a higher revenue from the same amount of assets (twice as much asset turnover as Company B), and this will help A to make a higher return on capital employed (or ROI) than B. Asset turnover is expressed as “x times” so that assets generate x times their value in annual sales. Here, Company A’s asset turnover is four times and B’s is two times. Profit margin and asset turnover together explain the ROI, and if ROI is the primary profitability ratio, these two others are the secondary ratios. The relationship between the three can be shown mathematically. Formula to learn: Profit margin x Asset Turnover =ROI ∴ (EBIT/Sales) x (Sales/Cost of Investment)=(EBIT/Cost of Investment) Examples: Profit Margin a) 2020 2019 ROI 3,095,576 360,245 3,095,576 1,099,899 1,099,899 11.64% b) Asset Turnover 360,245 x 3.06 times = 35.6% 247,011 1,099,899 247,011 1,099,899 768,769 768,769 12.94% x 2.48 times = 32.1% Investor Ratios These are the ratios which help equity shareholders and other investors to assess the value and quality of an investment in the ordinary shares of a company. Relevant ratios are: a) b) c) d) e) Earnings per share Dividend cover Price/Earnings ratio Dividend yield Dividend payout The value of an investment in ordinary shares in a company listed on a stock exchange is its MARKET VALUE, and so investment ratios must have regard not only to information in the company’s published accounts, but also to the current share price, and the PE Ratio and Dividend yield involve using the share price. a. Earnings per share - It is possible to calculate the return on each ordinary share in the year. This is the EPS. EPS are the amount of net profit for the period that is attributable to each ordinary share, which is outstanding during all or part of the period. The calculation can become very complex, but there are far more complicated aspects outside the scope of our syllabus. EPS = Earnings attributable to ordinary shares/Number of Ordinary Shares in issue b. Dividend Cover – Formula to learn: Dividend Cover = EPS/Dividend per OS c. Price-earnings ratio – relationship price to earnings, it shows how many years would it take for the shareholder to recover the price paid for the shares using the earnings received from the same shares, lower price-earnings ratio is desirable, while high priceearnings ratio indicates that the shares are overpriced. Formula is: Price per share Price-Earnings Ratio (P/E) = Earnings Per Share d. Dividend yield – relationship of dividends to the price per share, it shows the percentage of the price that was recovered through dividends. High dividend yield is desirable. Formula is: Dividend per share Dividend Yield = Price per Share e. Dividend payout – percentage of earnings that is distributed as dividends. Formula is: Dividend Per Ordinary Share Dividend payout = Earnings Per Share Notes: 1. Market Tests– relationship of price, dividends and earnings, market test shows if shares of stocks are worth purchasing or not. 2. Dividend cover is the inverse of dividend payout ratio Limitations of Financial Analysis Financial Statements are affected by the obvious shortcomings of historical cost information and are also subject to manipulation. Financial analysis, be it simple horizontal analysis with another company, trend analysis over time or ratio analysis, has several limitations. Many of these stem from the limitations of the financial statements themselves. 1. Limitations of Financial Statements a) Problems of historical cost information – is it reliable and verifiable? Is it relevant? b) Creative accounting c) The effect of related parties d) Seasonal trading e) Asset acquisitions 2. Accounting Policies a. The effect of choice 3. Changes in accounting policy 4. Limitations of ratio analysis 5. Other issues