ASEAN Politics & Government: Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos

advertisement

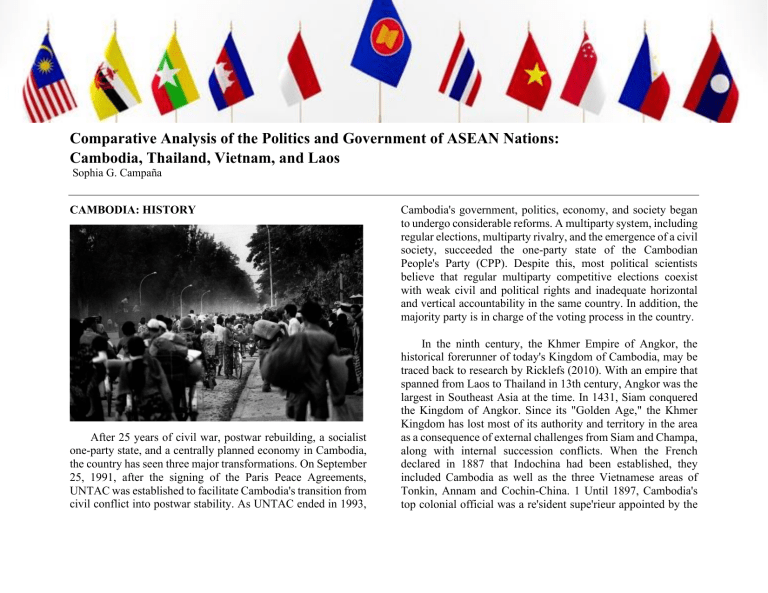

Comparative Analysis of the Politics and Government of ASEAN Nations: Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos Sophia G. Campaña CAMBODIA: HISTORY After 25 years of civil war, postwar rebuilding, a socialist one-party state, and a centrally planned economy in Cambodia, the country has seen three major transformations. On September 25, 1991, after the signing of the Paris Peace Agreements, UNTAC was established to facilitate Cambodia's transition from civil conflict into postwar stability. As UNTAC ended in 1993, Cambodia's government, politics, economy, and society began to undergo considerable reforms. A multiparty system, including regular elections, multiparty rivalry, and the emergence of a civil society, succeeded the one-party state of the Cambodian People's Party (CPP). Despite this, most political scientists believe that regular multiparty competitive elections coexist with weak civil and political rights and inadequate horizontal and vertical accountability in the same country. In addition, the majority party is in charge of the voting process in the country. In the ninth century, the Khmer Empire of Angkor, the historical forerunner of today's Kingdom of Cambodia, may be traced back to research by Ricklefs (2010). With an empire that spanned from Laos to Thailand in 13th century, Angkor was the largest in Southeast Asia at the time. In 1431, Siam conquered the Kingdom of Angkor. Since its "Golden Age," the Khmer Kingdom has lost most of its authority and territory in the area as a consequence of external challenges from Siam and Champa, along with internal succession conflicts. When the French declared in 1887 that Indochina had been established, they included Cambodia as well as the three Vietnamese areas of Tonkin, Annam and Cochin-China. 1 Until 1897, Cambodia's top colonial official was a re'sident supe'rieur appointed by the Ministry of Marine and Colonies in Paris, answerable to the French Governor General and appointed by Paris's Ministry of Marine and Colonies. There was less political activity in Cambodia in the 1930s compared to the Vietnamese-populated provinces of the Indochina, according to research by Brocheux and He'mery (2011). That changed in World War II when the French administration in Vichy was obliged to allow Japanese forces to enter the nation, as Ricklefs (2010) points out. King Norodom Sihanouk (1922–2012) was pushed by the Japanese to proclaim independence in March 1945, but the Japanese surrendered and the enthusiasm for independence quickly faded. As a result of the passage of a new constitution in 1947, Cambodia was no longer a French protectorate in 1949, and it was given full independence inside France. In November 1953, the Kingdom gained complete national sovereignty. Peou (2000) noted that new personalistic authoritarian regime: King Sihanouk resigned and became prime minister in 1955. Sihanouk's personal regiment, which he dubbed the "Khmer Rouge," was persecuted by both bourgeois and communist opponents. Sihanouk allowed the use of Cambodian land as a safe haven and supply route for the South Vietnamese Communists in accordance with a policy of international neutrality. According to Heder (2004) that it was in 1970 that a coup led by Lon Nol and a coalition of military officers and civilian elites against Sihanouk while the Cambodian leader was on vacation led to military rule in the country for the first time in its history. As a result, Sihanouk formed an alliance with the Khmer Rouge in order to rally the local populace. A series of intensive purges by the Khmer Rouge dictatorship led to the defection of a large number of military and party cadres to Vietnam. The Khmer Rouge rule was eventually overthrown in December 1978 when the xenophobic regime shifted its attention to Vietnam and Vietnamese soldiers attacked the country's eastern region. It was in 1989 that the Vietnamese government decided to withdraw its forces from combat. Although the Cambodian military still had a numerical advantage, the administration in Phnom Penh could no longer expect for success. Official peace discussions in Paris in 1991 were a result of informal conversations between the CGDK and the SoC. The warring parties signed the Paris Accords in 1991, which mandated the establishment of an interim government, the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia, under the guidance of the UN Security Council's Permanent Five and supported by the governments of Australia, Indonesia, Japan, and other concerned states (UNTAC). This organization was tasked with monitoring Cambodian authorities in the fields of foreign policy, defense, finance, information and public safety for a period of five years. Furthermore, UNTAC failed to ensure the impartiality of crucial ministries including Defense, Security and Home Affairs and Finance. A quarter of all combatants were disarmed and demobilized, mostly FUNCINPEC and KPNLF and a few CPP forces, but not the Khmer Rouge, which withdrew from the peace process in 1992. UNTAC's biggest success was the election of a Constituent Assembly in 1993, boycotted by the Khmer Rouge. The assembly adopted a constitution that envisaged parliamentary monarchy with King Norodom Sihanouk as head of state. UNTAC ended its mission in September 1993. Vietnamese Prime Minister Hun Sen's "personalist" rule rests on four pillars, including his control over the electoral process and access to state resources. He has created a form of "institutionalized nepotism" in which power and authority are highly personalized and concentrated in his hands. While the opposition has no access to material rewards or protection from state repression, it can participate in the distribution of state resources and the exploitation of the national economy. The opposition has a possibility of pulling off an electoral shock despite the fact that the country's elections aren't free and fair. a united opposition was successful in winning 55 of the 123 National Assembly seats in 2013. THAILAND: HISTORY The regime strives to legitimate its claim to power against its citizens and the international community. Hun Sen stylizes himself as the only person able to guarantee economic development and social peace. Elections at national and local level serve the purpose of legitimating the regime vis-a'-vis international donors and Western governments. The government tolerates basic human rights violations committed by members of the regime coalition, such as land grabbing, illegal-logging, and real estate speculation. This does not signal increased political liberalization, but instead authoritarian consolidation, as the Hun Sen government no longer feels the need to rely on hard repression to secure its political survival. According to Levitsky & Way (2002) stated that though Hun Sen's dictatorship seems to have found a balance between repression, legitimacy, and co-optation, a number of latent threats to his reign exist. It is important to note that the presence of competitive elections allows the opposition to question and damage the government inside its own institutions. Opposition parties and civil society groups may take on authoritarian rulers because of the presence of institutions ostensibly dedicated to democracy. The electoral sphere is the most significant of them. The Kingdoms of Sukhothai and Ayutthaya are traditionally considered the beginning of Siam. During the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV, 1850–1868), Siam yielded to pressure of Western powers. Rapid social change, conflicts between new and old elites weakened the power of the absolute monarchy. Following the overthrow of the absolute monarchy in 1932, a "bureaucratic" state became the primary arena of political rivalry for parcels of state control between two major forces: civilian bureaucrats and military elites. In contrast, King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX, 1946–2016) was symbolizing the historical continuity of Siam (Thailand) since ancient times but had little real political power himself. Long-term processes of economic and social change starting in the 1950s created new socioeconomic groups with new political demands and ideologies. During the anti-communist and highly repressive government of Thanin Kraivichien (1976–1977), thousands of intellectuals, student protesters, and trade-union activists fled to join the Communists in the jungle. In the 1980s, a new electoral authoritarian regime emerged when Army Commander General Prem Tinsulanonda became the unelected prime minister. When the government reintroduced parliamentary elections and legalized political parties, provincial capitalists turned their economic fortunes into political capital by financing political parties and mobilizing rural voters. In 1988, gradual liberalization under Prem opened the door for a short-lived democratic interregnum with an elected prime minister. Growing military suspicion of civilian interference in its domain, however, eventually led to an army coup under. General Suchinda Kraprayoon in February 1991. Mass protests took place in Bangkok from May 17–20, 1992. A series of shortlived coalitions took turns at governing in the following years. At the height of the Asian Financial Crisis, a new constitution came into force in October 1997. Nevertheless, the well-intended assumptions that this 1997 "People's Constitution" would pave the road for Thailand's democracy to expand and consolidate turned out to be false. Since the start of the millennium, Thailand has been in a state of political instability and upheaval. According to Abuza (2016), from 2001 to 2016, the nation witnessed five of eight sitting prime ministers overthrown by court decrees or military coups, two out of six Lower House elections invalidated, and a series of popular mobilization events. In addition, a century-old battle erupted anew in Thailand's three southernmost provinces in January 2004, killing or wounding almost 7000 people until June 2016. Thailand's current political crisis was not a social conflict at the outset. However, because of the way in which Thaksin Shinawatra took advantage of the plight of the poor, it quickly became one. By doing so, he threatened the informal, monarchical network that had formed since the 1970s that connected royalist elites in politics, military, civil service, economy, and society. TRT was disbanded, Thaksin and many top party leaders were excluded from politics, a new constitution was written, and general elections were held in late 2007. It gained 48 percent of the seats despite a skewed electoral system that favoured TRT's successor, allowing pro-Thaksin supporters to establish a coalition government. Returning to electoral democracy did nothing to reduce political division. An impeachment and PPP ban followed extended PAD demonstrations. In 2010, the pro-Thaksin United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD) staged major rallies in Bangkok that the Thai military violently dispersed, killing 23 and wounding hundreds. Nonetheless, another Thaksin-affiliated political party, the Puea Thai Party (PTP), won the 2011 election and created a government led by Yingluck Shinawatra, Thaksin's sister. In response, the People's Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) campaigned for another military coup, reviving the antiThaksin protest movement. On May 20, 2014, Thailand's military declared a state of emergency, led by Army Chief Gen. Prayuth Chan-ocha. General Prayuth led the military junta that was formed two days later. Since then, it has been ruled by the military. Thailand also lost a unique source of stability and societal harmony when Thai King Bhumibol Adulyadej died in October 2016. VIETNAM: HISTORY Vietnam's official name, "Socialist Republic of Vietnam," has been in use since 1976. It is one of only five "communist dictatorships" in the world that still exist after the fall of the Soviet Union. North Vietnam has been run by the Communist Party since 1954, and all of Vietnam since 1975. This makes the Communist Party one of the parties that has been in power the longest in the world. A study by Schirokauer and Clark (2004) stated that the Kingdoms of Aun Lac and Nam Viet, which were founded in the third century B.C., are historically considered the cradle of ancient Vietnamese sovereignty. In 111 BC, the Han Dynasty established Nam Viet as a Chinese prefecture. From the eleventh century forward, successive kingdoms were able to oust Chinese dominance, while Chinese customs and neo-Confucian official orthodoxy remained widespread and the administration of the Kingdom of Dai Viet under the Le Dynasty (1428–1788) followed the Chinese model. Dai Viet's power was initially limited to northern Vietnam (Tonkin) and parts of central Vietnam (Annam), but expansion at the expense of Cambodia and Champa was a recurring theme. In the eighteenth century, the Nguyen dynasty took control of the south and expanded its reach to the royal seat of Thang Long (Hanoi) in the north. Nguyen Anh proclaimed the Empire of Viet Nam in 1802 and founded the new capital in Hue in central Vietnam. Vietnamese unification under Nguyen collided with French expansion into Indochina. French troops occupied Da Nang, then Saigon (today, Ho Chi Minh City, HCMC) and neighboring provinces in 1858 and 1862, and forced the Nguyen Emperor to relinquish sovereignty over all of South Vietnam to France in 1874. Annam and Tonkin became French protectorates in 1882; these protectorates remained under nominal sovereignty of the Vietnamese court. The colonial misgovernment, corruption in the old but powerless Vietnamese bureaucracy, excessive taxation, and poverty and misery among the peasantry resulted in social unrest and localized protest. French repression of anticolonial movements unintentionally strengthened the communist movement, which gained strong support from workers and the urban intelligentsia. The French suppressed the Yeˆn Ba'i mutiny of 1930, but it indicated a failure of the policy of forcible depoliticization. Blanc (2004) noted that the Communist Party of Vietnam was formed in February 1930 when the Communist Party of Indochina merged with the Communist Party of Annam and the Communist League of Indochina. In order to include all of French Indochina, including Cambodia and Laos, the party, led by Nguyen Tat Thanh, better known as Ho Chi Minh, renamed itself the Indochinese Communist Party in October 1930. First from China, then from a base in Vietnam, the Communist Party was able to relaunch covert activities despite the efforts of the French government. This opportunity for the Communist Party to take control of the anticolonial struggle was provided by Japanese conquest in July 1941 and Vichy cooperation. A revolutionary uprising was launched in March 1945 by the Vietnamese Independence League (Viet Minh), who swiftly seized control of the country. On September 2, 1945, shortly after the Japanese capitulated, Ho Chi Minh announced the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) in Hanoi. The Provisional Government of the French Republic had to acknowledge the DRV as a sovereign state inside the French Union because France was unwilling to give up her colonial empire. The French-Vietnamese or First Indochina War lasted until French troops were defeated by the Viet Minh in the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954. Negotiations between France and the DRV government without participation from South Vietnam resulted in the Geneva Accords. North and South Vietnam remained separated, and while the north followed the political and economic lead of the Soviet Union and China, the south came under American influence. LAOS: HISTORY Dimitrov (2013) noted that the Democratic People's Republic of Lao is one of only five communist single party regimes in the world today. As a landlocked country with a sparsely populated hinterland, Laos struggles with unfavorable circumstances for economic development. Wedged in by more powerful neighbors, the country was frequently threatened both politically and military. Furthermore, Evans (2002) stated, the Kingdom of Lan Xang, founded in 1354, was the precursor of modern Laos. Historical memories of the ancient kingdom play a key role in postcolonial nation-building and Laos's socialist politics of legitimacy. The emergence of Lao nationalism delayed the emergence of French colonialism between 1893 and 1946. party. In recent years, nationalist-oriented (instead claims of legitimacy have become key ingredients of the party's legitimation strategy. During World War II, the Japanese Imperial Army took direct control over Laos, along with the rest of French Indochina. The Japanese supported the formation of a non-communist nationalist movement called Lao Issara. While French troops regained control of the country in 1946, France agreed to proclaim Laos as a self-governing constitutional monarchy within the French Union in 1949. In November 1953, however, Laos gained full sovereignty. During the Vietnam War or Second Indochina War, the country quickly became another front in the escalating conflict. The conflict was exacerbated by the massive American bombing campaign to disrupt the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the main North Vietnamese supply line that passed through Laos. During this phase of the conflict, more bombs were dropped on Laos than on Germany during World War II. Some observers argue that the communist regime in China can no longer be meaningfully characterized as communist, but has become a "post-socialist" political order. The socialist ideology still serves as a disciplinary instrument to control party cadres and society (Lintner 2008, p. 173) and while the commitment to the economic and social program of socialism remains suspect, adherence to the political structure of the communist party state signifies the enduring importance of Marxist–Leninism. Since 1975, the single-party regime of the Laotian Revolutionary Party (LPRP) has gone through various stages. In the initial phase of establishing party rule, the LPRP took complete control of the government and state apparatus. The collectivization of agriculture resulted in food shortages and swelled the stream of refugees. Central economic planning only began with the first 5-year plan in 1981. The 1991 Constitution marks the passage from revolutionary to consolidated party rule. Laos remains a closed single-party regime in which the LPRP monopolizes access to political office. Performance-based legitimation from economic growth and improving the livelihoods of the population are important new sources of legitimacy for the The absence of any significant political opposition within Laos reflects the strength of single-party rule in the country. However, the LPRP still faces some challenges that could potentially endanger regime stability in the long term. The economic transformation has resulted in rising horizontal socioeconomic inequalities, amplifying problems of socioeconomic inequality. Inefficient institutions will likely persist, which would stabilize party rule in the short- to medium-term, but threaten the legitimacy and survival of the communist party state. JUDICIAL BRANCH NATIONAL AND LOCAL GOVERNMEN T The legislative branch of the Cambodian government is made up of a bicameral parliament. The country has a constitutionall y independent judiciary composed of lower courts, an appeals court, and a Supreme Court. The National Assembly of Thailand is a bicameral legislature and is composed of two houses: the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Constitutional Court of the Kingdom of Thailand, the Courts of Justice, the Administrative Courts and the Military Courts. ASEAN COUNTRIES EXECUTIV E BRANCH LEGISLATIV E BRANCH CAMBODI A The Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) THAILAND The cabinet is the primary organ of the executive branch of the Thai government. HIGHLIGHT SOME GOVERNMEN T POLICIES ECONOMY CULTURE Cambodia is a unitary country with a three-tier subnational government system. The 1993 Constitution referred to the division into provinces and municipalities. Driven by garment exports and tourism, Cambodia's economy sustained an average annual growth rate of 7.7 percent between 1998 and 2019, making it one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. Cambodians have developed a unique Khmer culture and belief system from the syncretis m of indigenous animistic beliefs and the Indian religions of Buddhism and Hinduism. • Economics • Health • Pandemic • Education • Job Opportunities • Women’s Rights Three systems: central administration, local administration, and local autonomy (under the State Administration Act of 1991) Thailand's economic freedom score is 63.2, making its economy the 70th freest in the 2022 Index. Thailand is ranked 13th among 39 countries in the Asia–Pacific region, and its overall score is Buddhism and the monarchy have historically been seen as sources of order and stability in society and continue to act as symbols of • Public transport • Strategic Planning • Environmental Policies • Urban Realm policies above the regional and world averages. unity for the Thai people. VIETNAM The government (Chính phủ), the main executive state power of Vietnam, is headed by the Prime Minister, who has several Deputy Prime Ministers and several ministers in charge of particular activities. The National Assembly (Vietnamese: Quốc hội) is a unicameral legislative body, and is governed on the basis of democratic centralism. The court system consists of the Supreme Court, the provincial People's Courts and the district People's Courts Vietnam has a three-tier local government structure: provincial , district and commune levels. There are 63 provincial units including 5 cities. Vietnam's economi c freedom score is 60.6, making its economy the 84th freest in the 2022 Index. Vietnam is ranked 18th among 39 countries in the Asia–Pacific region, and its overall score is above the regional and world averages. Vietnamese culture was heavily influenced by Chinese culture due to the 1000 years of Northern rule. • Information and Education • Economic Instruments • Policy support LAOS The president is elected by the National Assembly for a five-year term. The prime minister and the Council of Ministers are appointed by the president with the approval of the National Assembly for a five-year term. The National Assembly (Sapha Heng Xat) has 164 members (158 are LPRP, 6 independents), elected for a fiveyear term. The Supreme Court, the local Court and the Military Court. The politics of the Lao People's Democratic Republic (commonly known as Laos) takes place in the framework of a one-party parliamentary socialist republic. The only legal political party is the Lao People's Revolutionary Party (LPRP). Laos is among the least developed and poorest countries in Asia, but significant economic growth in the past decade has benefited the country. Lao culture is centered on the pleasures of life: eating, drinking, sleeping and chatting with friends. • Employment policies • Security policies • Health policies • Safety policies • Education • Regulatory policies REFERENCES: Ricklefs, M. C. (2010). A new history of Southeast Asia. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Tully, J. A. (2002). France on the Mekong: A history of the protectorate in Cambodia, 1863–1953. Lanham: University Press of America. Karbaum, M. (2008). Kambodscha unter Hun Sen: Informelle Institutionen, politische Kultur und Herrschaftslegitimitat € . Münster: LIT Verlag. Roberts, D. (2001). Political transition in Cambodia 1991-1999: Power, elitism and democracy. London: Curzon. Levitsky, S., & Way, L. (2002). The rise of competitive authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy, 13, 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2002.0026 Cock, A. (2010). Anticipating an oil boom: The “Resource Curse” thesis in the play of Cambodian politics. Pacific Affairs, 83, 525–546. https://doi.org/10.5509/2010833525 Morgenbesser, L. (2017). Misclassification on the Mekong: The origins of Hun Sen’s personalist dictatorship. Democratization, 29, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2017.1289178 Brocheux, P., & He´mery, D. (2011). Indochina: An ambiguous colonization 1858–1954. Berkeley: University of California Press. Peou, S. (2000). Intervention and change in Cambodia: Towards democracy? Chiang Mai: Silkworm Press. Heder, S. R. (2004). Cambodian communism and the Vietnamese model. Bangkok: White Lotus Press. Englehart, N. A. (2001). Culture and power in traditional Siamese government. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Wyatt, D. K. (1984). Thailand. New Haven/London: Yale University Press. Mead, K. K. (2004). The rise and decline of Thai absolutism. New York: Routledge. Riggs, F. W. (1966). Thailand: The modernization of a bureaucratic polity. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. Connors, M. K. (2003). Democracy and national identity in Thailand. New York: Routledge. Wongrangan, K. (1984). The revolutionary strategy of the communist party of Thailand: Change and persistence. In J.-J. Lim & S. Vani (Eds.), Armed Communist movements in Southeast Asia (pp. 131– 185, Issues in Southeast Asian security). Singapore: ISEAS. Chai-anan, S. (1997). Old Soldiers Never Die. They are just bypassed: The military, bureaucracy and globalization. In K. Hewison (Ed.), Political change in Thailand: Democracy and participation. London: Routledge. McCargo, D. (1997). Thailand’s political parties: Real, authentic and actual. In K. Hewison (Ed.), Political change in Thailand: Democracy and participation (pp. 114–131). London: Routledge Schirokauer, C., & Clark, D. N. (2004). Modern East Asia: A brief history. South Melbourne: Thomson Blanc, M.-E. (2004). An emerging civil society? Local associations working on HIV/AIDS. In D. McCargo (Ed.), Rethinking Vietnam (pp. 153–165). London: RoutledgeCurzon. Schuler, P., & Malesky, E. (2014). Authoritarian legislatures. In S. Martin (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of legislative studies (pp. 676–695). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Thayer, C. A. (2013). Military politics in contemporary Vietnam: Political engagement, corporate interests, and professionalism. In M. Mietzner (Ed.), The political resurgence of the military in Southeast Asia: Conflict and leadership (pp. 63–84). New York: Routledge.