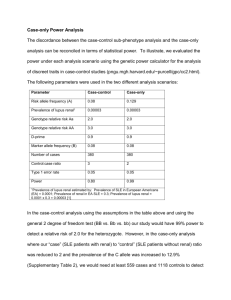

TREAT SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOUS Determining the appropriate therapeutic regimen requires an accurate assessment of: - Disease activity: manifestations of the underlying inflammatory process at a point in time in terms of magnitude and intensity à three patterns of disease: Intermittent disease flares / Chronically active disease in terms of organ involvement / quiescent disease - Disease severity: type and level of organ dysfunction and its consequences, often described as mild, moderate, and severe - patient's response to previous and ongoing therapeutic interventions. In clinical practice, disease activity and severity are assessed using a combination of clinical history, physical examination, laboratory and serologic studies as well as organ-specific tests: - Clinical evaluation — o All organ systems must be reviewed and examined o Ask about any potential triggers such as sun exposure, infection, or discontinuation of therapy. - Laboratory evaluation — help assess disease activity and monitor organ-specific complications (such as renal or hematological). There is no single marker of disease activity, we typically check: o CBC with differential: Leukopenia, anemia and thrombocytopenia may reflect active disease. Cytopenias may also result from drug toxicities. o ESR and CRP: Increases are commonly observed in patients with SLE, and therefore may not be as reliable for detecting disease. Nonetheless, an elevated ESR can be associated with increased disease activity and accrued damage. An elevated CRP should raise the suspicion for infection in a patient with SLE. o Urinalysis with examination of urinary sediment – Proteinuria or cellular casts and hematuria may be due to lupus involving the kidney. o Spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio – Quantification of proteinuria helps assess the severity of glomerular disease o Serum creatinine and eGFR – Elevations in creatinine may reflect lupus nephritis. o Anti-dsDNA – Titers often fluctuate with disease activity, particularly in patients with active glomerulonephritis o C3 and C4 – Low C3 and C4 and/or elevated C3 and C4 activation products often indicate active lupus, particularly lupus nephritis. - Additional studies — Monitoring for specific SLE-related organ involvement typically requires additional studies such as ECG, lung function tests, x-rays, CT scans, and renal or other organ (eg, skin) biopsies. - Monitoring frequency — depending on disease activity (eg every one to two weeks in active lupus nephritis and every 3 to 4 months in quiescent SLE) - Flares: o Definition: No consensus on what constitutes a disease flare, but most definitions have incorporated a combination of serologic measures and disease activity indices. A moderate or severe flare refers to a measurable increase in disease activity that is clinically meaningful enough to result in a change in therapy. Exemples: Symptoms Laborato Treatment and signs ry evaluatio n Mild new onset mild no treatment or addition SLE low-grade leukopen of hydroxychloroquine or the flare fevers, a ia equivalent of prednisone 7.5 malar rash, mg per day or less. and arthralgias , increasingl y fatigued Modera pleuritic te SLE chest pain flare and a swelling of the wrists Severe SLE flare elevated acute phase reactants , rightsided pleural effusion new onset low C3, renal C4, insufficien elevated cy and dsDNA significant antibodie proteinuria s, and due to elevated lupus acute nephritis phase reactants short course of prednisone high doses of glucocorticoids (eg, 1 to 2 mg/kg/day of prednisone or equivalent or intermittent intravenous "pulses" of methylprednisolone), additional immunosuppressive therapy (eg, cyclophosphamide, azathio prine, or mycophenolate mofetil), and/or hospitalization. o Predictors: § Of an SLE flare (particularly lupus nephritis) are the onset of an increased serum titer of anti-dsDNA antibodies and a fall in complement levels (especially CH50, C3, and C4). Persistently low serum levels of complement C1q are also associated with activity of lupus nephritis § Other clinical features that are associated with an increased risk of SLE flare include diagnosis of SLE before age 25, patients who have renal, vasculitic, or neurologic involvement. NON PHARMACOLOGIC AND PREVENTIVE INTERVENTIONS a- Sun protection — and avoid exposure to direct or reflected sunlight use sunscreens and avoid medications that can cause photosensitivity (doxycycline, piroxicam, tolbutamide, furosemide, chlorthiazide, hydrochlorothiazide, chlorpromazine, promethazine, amiodarone…) b- Diet and nutrition — balanced diet consisting of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. (increase caloric intake when active inflammatory disease and fever, vitamin D because of low serum levels of 25hydroxyvitamin D due to avoidance of sun exposure and/or use of sunscreen products) c- Exercise — Inactivity produced by acute illness causes a rapid loss of muscle mass, bone demineralization, and loss of stamina resulting in a sense of fatigue. d- Smoking cessation — smoking has been associated with more active disease and diminishes the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine e- Immunizations — appropriate immunizations prior to immunosuppressive therapies (Influenza, pneumococcal, HPV, hepatitis B vaccines are safe). Live attenuated vaccines (eg, measles, mumps, rubella, polio, varicella, zoster, and vaccinia [smallpox]) can lead to complications in patients on immunosuppressive therapy. f- Treating comorbid conditions — Accelerated atherosclerosis, pulmonary hypertension, and antiphospholipid syndrome, as well as osteopenia or osteoporosis can be screened and treated: g- Issues with specific medications and therapies — a- Sulfonamide-containing antimicrobials have been associated with SLE allergies and exacerbations and should therefore be avoided, if possible. b- By contrast, medications that cause drug-induced lupus, such as procainamide and hydralazine, do not cause exacerbations of idiopathic SLE. Avoid the use of minocycline in patients with established (idiopathic) SLE. h- Pregnancy and contraception — Women with SLE should be counseled not to become pregnant until the disease has been quiescent for at least six months PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES: I- Treatment of constitutional symptoms: a- Hydroxychloroquine: Risk factors for retinopathy: duration of treatment, dose, CKD, preexisting macular retinal disease b- Glucocorticosteroids: - longterm aim should be to minimise daily dose to ≤7.5 mg/day prednisone equivalent or to discontinue them - two approaches can be considered: (1) use of pulses of IV methylprednisolone (MP) of various doses (depending on severity and body weight), which may allow for a lower starting dose and faster tapering of PO GC, and (2) early initiation of IS agents, to facilitate tapering and eventual discontinuation of oral GC. - High-dose intravenous MP (usually 250–1000 mg/day for 3 days) is often used in acute, organ-threatening disease (eg, renal, neuropsychiatric) after excluding infections. c- Immunosuppressive therapy: - Methotrexate (MTX) and azathioprine (AZA) à relatively safe profile. - Published evidence is generally stronger for MTX than AZA, yet the latter is compatible with pregnancy contemplation. - Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is a potent immunosuppressant with efficacy in renal and non-renal lupus (although not in neuropsychiatric disease). It is teratogenic potential (needs to be discontinued at least 6 weeks before conceiving), - Cyclophosphamide (CYC) à o in organ-threatening disease (especially renal, cardiopulmonary or neuropsychiatric) and only as rescue therapy in refractory non-major organ manifestations o Gonadotoxic effects so use with caution in women and men of fertile age.55–57 à Concomitant use of GnRH analogues attenuates the depletion of ovarian reserve in premenopausal patients with SLE. Information about the possibility of ovarian cryopreservation should be offered ahead of treatment. o Risk of malignancy and infections should also be considered d- Biological agents: - Belimumab should be considered in: o extrarenal disease with inadequate control to first-line treatments (typically including combination of HCQ and prednisone with or without IS agents), and inability to taper GC daily dose to acceptable levels (ie, maximum 7.5 mg/day). o More likely to respond are patients with high disease activity, prednisone dose >7.5 mg/day and serological activity (low C3/C4, high antidsDNA titres), with cutaneous, musculoskeletal and serological manifestations. - RTX is currently only used off-label, in: o patients with severe renal or extrarenal (mainly haematological and neuropsychiatric) disease refractory to other IS agents and/or belimumab, or in patients with contraindications to these drugs. o More than one IS drug need to have failed prior to RTX administration, except perhaps for cases of severe autoimmune thrombocytopaenia and haemolytic anaemia, where RTX has demonstrated efficacy both in lupus and in patients with (ITP). o In LN, RTX is typically considered following failure of firstline therapies (CYC, MMF) or in relapsing disease. II- Treatment for specific SLE manifestations — There is limited evidenced-based literature for managing organ-specific manifestations outside of the kidney and skin manifestations. - Fatigue: exclude other causes (depression, deconditioning, disordered sleep, fibromyalgia, and iron-deficiency anemia) à then, low-dose glucocorticoids and hydroxychloroquine - Fever: after excluding an underlying infection àNSAIDs, acetaminophen, and/or low to moderate doses of glucocorticoids. Fever that does not respond to such therapy further raises the suspicion of an infectious and/or drug-related etiology - Specific organ system involvement — a- Skin disease - Effective protection from ultraviolet exposure with broad-spectrum sunscreens andsmoking cessation are strongly recommended. - A sizeable proportion (almost 40%) of patients will not respond to first-line treatment à MTX can be added. Other agents include retinoids, dapsone and MMF. - Belimumab and RTX have also shown efficacy in mucocutaneous manifestations of SLE; RTX may be less efficacious in chronic forms of skin lupus. - Thalidomide is effective in various subtypes of cutaneous disease. Due to its strict contraindication in pregnancy, the risk for irreversible polyneuropathy, and the frequent relapses on drug discontinuation, it should be considered only as a ‘rescue’ therapy b- Neuropsychiatric disease (NPSLE) - Patients with SLE with cerebrovascular disease should be managed like the general population in the acute phase - in addition to controlling extra-CNS lupus activity, IS therapy may be considered in the absence of aPL antibodies and other atherosclerotic risk factors or in recurrent cerebrovascular events. - Targeted symptomatic therapy (eg, antipsychotics for psychosis, anxiolytics for anxiety disorder and so on). c- Haematological disease - Significant lupus thrombocytopaenia (plt < 30 000/mm3) : o First-line treatment is moderate/high doses of GC in combination with IS agent (AZA, MMF or cyclosporine; the latter having the least potential for myelotoxicity) to facilitate GC-sparing. Initial therapy with pulses of intravenous MP (1–3 days) is encouraged. o IVIG in the acute phase, in cases of inadequate response to high-dose GC or to avoid GC-related infectious complications. o Treatment is typically lengthy and often characterised by relapses during GC tapering. o If no response to GC (ie, failure to reach a platelet count >50 000) or relapses, RTX should be considered. CYC may also be considered in such cases. o Thrombopoietin agonists or splenectomy reserved as last options. - Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA) is less common than thrombocytopenia in SLE; its treatment follows the same principles regarding use of GC, IS drugs and RTX. - Autoimmune leucopaenia is common in SLE but rarely needs treatment; careful work-up is recommended to exclude other causes of leucopaenia (especially drug-induced). d- Renal disease - Patients at high risk of developing renal involvement (males, juvenile lupus onset, serologically active including positivity for anti-C1q antibodies) à vigilant monitoring (eg, at least every 3 months) to detect early signs of kidney disease. - Diagnosis should be secured with a kidney biopsy - Treatment of LN includes: o initial induction phase, followed by a more prolonged maintenance phase. o MMF and CYC are the IS agents of choice for induction treatment; § low-dose CYC is preferred over high dose (comparable efficacy and lower risk of gonadotoxicity) § Use MMF or high-dose CYC in severe forms of LN associated with increased risk of progression into endstage renal disease o An early significant drop in UPr (to ≤1 g/day at 6 months or ≤0.8 g/day at 12 months) is a predictor of favourable long-term renal outcome. o MMF or AZA may be used as maintenance therapy, with the former associated with fewer relapses; the choice depends on the agent used for induction phase and on patient characteristics, including age, race and wish for pregnancy. o In refractory or relapsing disease, RTX may be considered. o CNIs may be considered as second-line agents for induction or maintenance therapy mainly in membranous LN, podocytopathy, or in proliferative disease with refractory nephrotic syndrome, despite standard-of-care within 3–6 months; they may be used alone or in combination with MMF. e- Comorbidities: - High risk aPL profile (ie, triple aPL positivity, lupus anticoagulant or high titres of anticardiolipin antibodies) - in patients with SLE-APS, use of novel oral anticoagulants for secondary prevention should be avoided