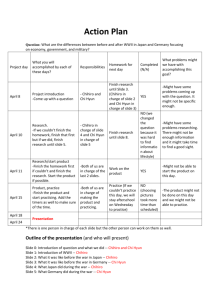

Anime as a New Form of Folklore: The Archetypes in Spirited Away Zoe Lucas Anime Ecology Dean Jennifer Prough 12/14/2021 Honor Code: I have neither given or received, nor have I tolerated others’ use of unauthorized aid. Zoe Lucas Lucas 2 I grew up watching fairy tales, predominantly Disney films like The Little Mermaid, Sleeping Beauty, and Tangled. These stories shaped my underdeveloped views on love, culture, and morals; and I would generalize and say that thousands of others had similar childhood experiences to me. A little later in my childhood, my interests shifted, and I was watching these Japanese cartoon-type shows, Sailor Moon, Pokémon, and Squid Girl. These shows were undoubtedly weird; my parents did not understand the appeal of the strange-looking characters with impossibly big eyes. Yet, there was something particularly resonant about these shows; their plotlines were nothing like the generic Disney films I grew up with, but in other ways, they were so similar. It was not until I was older that I was able to distinguish why I saw these similarities coinciding with these differences: anime is a new form of folklore in Japan just as Disney builds upon predominantly Western folklore. Built upon recurring structures and universal themes, anime reflects well-known fairy tales. However, it is unlike any other form of media and is its own genre in popular culture. There is something universal in anime like Spirited Away that resonates with me and thousands of viewers worldwide, yet at the same time reveal a distinct and profound respect for Japanese culture. Spirited Away is a Studio Ghibli film, a popular Japanese filmmaking enterprise known for their heartwarming, if eccentric works. Spirited Away is a film released August 31st, 2002 and up until very recently the highest-grossing film in Japan to date. Furthermore it is a, “globally recognized work, it won a number of accolades including an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature Film (2003), a Golden Bear at the Berlin International Festival (2002) and a nomination by the British Film Institute as one of the top ten films you should see by the age of fourteen.” 1 Yama, Megumi. “Spirited Away and its depiction of Japanese traditional culture.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Jungian Film Studies, edited by Luke Hockley, Routledge, 2018, 254-262. 1 Page 2 Lucas 3 The film is about a grudging young girl on the cusp of adolescence, Chihiro, and her family moving into the countryside. While driving, her father takes a wrong turn and they end up in front of a tunnel, where they cross over a threshold through the tunnel into the spirit world. Chihiro’s parents ravenously eat food they find in a stall, and as the sun sets and they continue to fulfill their gluttony, they transform into pigs. Horrified, Chihiro flees the scene in search of help, and as she runs through the village, she is surrounded by fantastical spirits and starts to become a spirit herself. For Chihiro, “the Bathhouse presents as dream-like place – an unconscious fantasy - that challenges her fear of change…a contained, yet meandrous alchemical and transformative space that equates to the Jungian unconscious where archetypal energies work to drive a sense of individuation, or psychological development.”2 A friendly boy/dragon spirit, Haku, finds her and becomes determined to help her. He warns her against Yubaba, the malicious bird spirit who rules the bathhouse, and against letting the other spirits know she is human. He helps her pass into the spirit world and urges her to seek out Kamaji, the hybrid-spider boiler man, and beg for a job. While in the spirit world, she is dubbed “Sen” and starts to lose her sense of “Chihiro” self. Once she completely loses herself, she will never make it home. Chihiro find a maternal figure in Lin, who takes her under her wing. She befriends a strange no-faced spirit, whom she invites into the bathhouse and, to her surprise, he makes gold. The catch is that the spirit has an insatiable appetite, which starts to affect business and safety, so Chihiro must talk the spirit down. Haku is injured, and Chihiro visits Yubaba’s kind twin, Zaneba, to find medicine to heal him. The spell ends up being broken by love, and as a final test, she must identify her parents amongst the other 2 Yama, Megumi. “Spirited Away and its depiction of Japanese traditional culture.” Page 3 Lucas 4 pigs. Her and her family return to the human world with a new outlook, sense of self, and maturity; and, most importantly, readiness to confront a new life. The strange film encapsulates the essence of folklore while at the same time existing in pop culture. The term for this, dubbed by Michael Dylan Foster, Professor of Folkore and Asian Studies, in his notable piece, The Challenge of the Folkloresque, is “folkloresque”. As a preemptive measure to differentiate, he defines folklore simply as traditional narratives. In a broader sense, folklore is an expression of a culture of a group of particular people. It is a critically defining factor of nations and peoples, and shape who they are and their values. To contrast, the folkloresque is, “popular culture’s own (emic) perception and performance of folklore… it refers to creative, often commercial products or texts that give the impression to the consumer that they derive directly from existing folkloric traditions.”3 In other words, folkloresque popular culture’s take on elements of folklore as displayed through modern media forms. It is special because it takes unique, novel works and honors their differentness, while acknowledging common strings found in age-old pieces. It ties together the past and present in an intentional way. One way Spirited Away contains folkloresque aspects is through the setting. In the very first scene, the dad turns down a beaten-up path through a forest. In the forest, there are little stones and statues everywhere where spirits allegedly live. The forest is a classic fairy tale setting, take Sleeping Beauty, Hansel and Gretel, Rapunzel, etc. It is nearly impossible to find a fairy tale that does not have at least one scene in a forest.4 This gives Spirited Away that authenticity associated with “real folklore” that Foster emphasizes, which is less about what it is 3 Foster, Michael Dylan. 2016. Introduction: The Challenge of the Folkloresque. Utah State University Press, Page 5. 4 Spirited Away 2:00-3:45 Page 4 Lucas 5 and more about how the audience perceives it. The forest setting is especially important in Japanese culture, but the associations are a bit different in Japan as opposed to Western culture. In the West, forests are often portrayed as wild and untamed, whereas the Japanese value cultivated nature, better known as satoyama landscapes. Satoyama landscapes are a type of “‘encultured’ nature” that “represents a sphere in which nature and culture intersect,” reminiscent of an “idyllic rural lifestyle” when “the Japanese ‘lived in harmony with nature.’”5 The term literally translates to “village mountain,” but is more generally recognized to be a “semi-managed, semi-cultivated area of woodland, shrubland and grassland surrounding human settlements, generally rural ones.”6 It can be interpreted as a traditional agrarian model that can, “function as a source of food, compose, and fuel resources”7 that is more sustainable than modern farming practices that use the ends of increased output to justify the means of potentially disrespecting the land. Satoyama landscapes can be seen at the beginning of Spirited Away, functioning as the gateway to the bathhouse: “her father tries to make a short-cut and ends up taking a wrong turn, they pass an old torii (a gateway to a Shinto shrine) which stands at the entrance to an unpaved mountain path scattered with numerous hokora (small shrines or spirit houses). These mystic symbols suggest a threshold into the spirit realm.”8 This older tradition of the satoyama being brought into new media forms displays how anime is a new form of folklore in Japan. Another recurring element that can be found in Spirited Away is magic. Magic can be found across cultures and stories from the past, from characters like the witch Circe in Greek Knight, Catering. December 2010. The Discourse of ‘‘Encultured Nature’’ in Japan: The Concept of Satoyama and its Role in 21st-Century Nature Conservation. Vol. 34, pp. 421-441. 6 Knight Encultured Nature 422 7 Knight 424 8 Yama, Megumi. “Spirited Away and its depiction of Japanese traditional culture.” 5 Page 5 Lucas 6 Mythology, notorious for turning men into pigs, to fairy tale princesses like Rapunzel, whose golden hair has healing qualities. The magic in Spirited Away is tied closely to nature. For example, Haku is a water spirit, the spirit of Kalaku River; Yubaba has control over all the elements, most notably air and fire; wind is a recurring theme, pulling the family into the tunnel that begins Chihiro's adventure. Magic, and especially giving the elements magical power, gives the story a timeless feeling that makes the viewer feel reminiscent of something they have seen or heard of before, “as if the events and characters are adapted from age-old narratives and beliefs.”9 The spirits in Spirited Away are magical, and are indicative of being a part of an older Japanese tradition, despite the fact that most do not have roots in folklore or traditional tales. For Foster, the fact that the creatures are not actual yōkai but like them is a part of the folkloresque; it makes it like folklore. These Japanese tales contain yōkai, which is another term for spirits; and kami, a key concept associated with yōkai literally translating literally to “god” or “deity.” This literal translation is misleading because, “kami in Japan may be worshipped and prayed to, but they do not have the all-powerful status attributed to gods in monotheistic religions. Rather, there are multitudes of kami inhabiting all sorts of things in the natural world.”10 In other words, almost anything, especially in nature, can be possessed by a kami spirit. According to Japanese folklorist Kazuhiko Komatsu, the “Japanese believed in the existence of an ‘other world’, and the possibility of being transported to, or ‘hidden’ within, this dimension by someone or something that has entered the everyday. ‘Kami’ is ambiguously used as a generic term for these kinds of 9 Foster The Challenge of the Folkloresque 3 Foster, Michael Dylan, and Kijin Shinonome. 2015. The Book of Yō kai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. University of California Press. 10 Page 6 Lucas 7 trespassers.”11 Even though the specific spirits in Spirited Away are not in any actual tales, they feel like they are, allowing the viewers to perceive them to be. By incorporating spirits into common forms of media, anime reuses them to form a new work that has a universal appeal. The characters in Spirited Away reflect common tropes found in tales across time and place, as explored by Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist and author who founded the branch of analytical psychology. He coined a term called the “collective unconscious,” which is the idea that there are “contents and modes of behavior that are more or less the same everywhere and in all individuals... it is identical in all men and thus constitutes a common psychic substrate of a suprapersonal nature which is present in every one of us.”12 According to the Oxford Languages dictionary, it is, “the part of the unconscious mind which is derived from ancestral memory and experience and is common to all humankind, as distinct from the individual's unconscious.”13 The collective unconscious is composed of feeling-toned complexes called archetypes, which ultimately make up who we are and reveal the nature of the soul. Archetypes are universal forms that shape our psychic processes and ideas, known indirectly through symbols. Some common archetypes are the Self, anima and animus, and the shadow. Archetypes can be found throughout cultures, mythologies, and stories. Joseph Campbell, an American author, came up with the idea of a hero’s journey based on Jungian archetypes, which is a repetitive, symbolic storyline characterized by struggle and representative of coming to consciousness out of the surrounding unconsciousness. He wrote about the hero’s journey in his book, The Power of Myth, with the thesis that “Myths are clues to 11 Komatsu, Kazuhiko. 2002. Kamikakushi to nihon jin. Kadokawa Sophia bunko. Tokyo: Kadokawa-shoten. 12 Jung, C.G. 2014. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated by R.F.C. Hull, Second ed., Volume Nine, Routledge. 13 Oxford Languages Page 7 Lucas 8 the spiritual potentialities of the human life.”14 He delves into archetypes in his book The Hero of a Thousand Faces. He identifies eight types of characters found in the hero’s journey: hero, mentor, ally, herald, trickster, shapeshifter, guardian, and shadow. The hero is the protagonist who must struggle to overcome some challenge. The mentor aids the hero in some way, shape, or form, like through a meaningful gift or advice that helps the hero through the challenge. The ally also assists the hero but is often less insightful and more directly involved in the journey itself, more like a sidekick. The herald comes into the story to signify change, like by delivering a message. The trickster acts as comic relief, but also aids the hero by giving him/her a new perspective. Shapeshifter characters change, generally in reference to their motives or relations to the hero. The guardian acts as an obstacle to the hero’s success that he/she must defeat in some way to continue on his/her journey. Finally, the shadow is the villain of the story and acts as the threat the hero must overcome to come out triumphant. The presence of these eight characters gives stories universal storyline appeal that is explained by the collective unconscious. According to Adam Waude, these archetypes are composed of characters found in stories throughout cultures, regardless of interaction between the nations15. According to an article written for The Routledge International Handbook of Jungian Film Studies, “Many of the mercurial beings inhabiting the Bathhouse represent concepts of alignment, compensation, equilibrium and the changing nature of these energies as they work together to harness a sense of wholeness.”16 Furthermore, “audiences are exposed to a realm of the imagination populated by 14 Campbell, Joseph, et al. The Power of Myth. Turtleback Books, 2012. 5. Waude, Adam. "How Carl Jung's Archetypes And Collective Consciousness Affect Our Psyche." Psychologist World. January 22, 2016. Accessed April 26, 2019. https://www.psychologistworld.com/cognitive/carl-jung-analytical-psychology. 16 Yama, Megumi. “Spirited Away and its depiction of Japanese traditional culture.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Jungian Film Studies, edited by Luke Hockley, Routledge, 2018, 254-262. 15 Page 8 Lucas 9 spiritual elements and loosely guided by a mixture of lesser male and more dominant female energies that align to notions of earthiness and spirituality.”17 The most obviously dominant female character is Yubaba, the main villain. It is sometimes rare to see a female in such a powerful role, especially since, “the idea of male domination over women still prevails in all aspects of contemporary Japanese society, and is largely accepted as natural.”18 Yet in anime, seeing powerful women in both heroic and nefarious roles is not uncommon. Yubaba is characterized as the magician, who possesses magical qualities and is generally portrayed as the villain who must be defeated. Yubaba is a wrinkly old witch with a comically large body and nose and overbearing and intimidating personality. Fig. 1 Yubaba The scene when Chihiro first meets Yubaba19 is especially striking in demonstrating her personality and characterization. Chihiro enters an intricate flower hallway after exiting the elevator. It is dark in the hallway with deafening silence, the only sound being Chihiro’s barefoot footsteps on the tile, making her seem even more naïve and innocent. Ominous music starts to play as she approaches the ornate red door with gold handles. Everything leading up to the room suggests wealth and opulence, demonstrating Yubaba’s materialism. Chihiro hesitantly reaches for the door when the knocker in the shape of Yubaba’s face chides her to knock, the first Yama, Megumi. “Spirited Away and its depiction of Japanese traditional culture.” Yama, Megumi. “Spirited Away and its depiction of Japanese traditional culture.” 19 Spirited Away 34:08-40:40 17 18 Page 9 Lucas 10 demonstration of the supernatural abilities of Yubaba in this scene. The door swings open to another intricate hallway, and then flashes to a close up of Yubaba’s comically large nose and mole, inviting her in. It flashes back to Chihiro briefly, and then back to Yubaba’s fingers beckoning her in, adorned with expensive-looking rings. The camera play here adds to the mystery and power shrouding Yubaba for Chihiro at this point. Chihiro is pulled in through a maze of hallways, adorned with chandeliers and ornate vases depicting shapes, colors, and creatures. She eventually tumbles into a Victorian style room with a fireplace and rich red chairs, making her seem particularly childlike. Anticipatory music swells, and three green ogre heads, Yubaba’s henchmen, bounce across the floor. The camera pans over to Yubaba, writing at her desk, suggesting she is someone important and powerful. Chihiro immediately asks for a job and Yubaba magically zips her lips and cackles menacingly, and insults her, saying this is no place for humans. The power dynamic is solidified here: Chihiro speaks when Yubaba allows here, making her subservient. As Yubaba is speaking her gold earrings flash, and moments like these throughout the scene demonstrate her obsession with wealth and how she prioritizes it over the well-being of her workers and others around her. Yubaba, while smoking, expresses that she does not regret transforming Chihiro’s parents into pigs since they deserved it for being gluttonous. Chihiro quivers, helpless against her power. Yubaba continues to laugh, but also coughs from smoking and her old age, creating a horrible cacophony as she asks her who has been helping her to make it this far. The camera pans back over to Chihiro, whose lips are unzipped, and she breathlessly and desperately asks for a job again. This ignites Yubaba’s rage and wind rises up behind her and she flies across the room and insults her, asking why she should give a job to a lazy, spoiled crybaby. The camera zooms in to Chihiro, trembling in fear, as Yubaba snakes around her, her giant eye next to her head and Page 10 Lucas 11 red talons wrapping around her body. The extreme size difference physically reinforces the power dynamic. The only reason Chihiro gets a job is because Yubaba’s equally giant baby throws a tantrum and objects start clattering to the floor all around them. Yubaba immediately switches to a maternal mode, switching back and forth depending on whether she is talking to Chihiro or her baby, demonstrating an almost bipolar nature. A contract flies over to Chihiro while hopeful music plays, since Yubaba can give people certain statuses or change events through contractual agreements. Once signed, Yubaba magically lifts her name from the paper, indicating ownership, renaming her Sen. The scene ends when Haku comes in and is instructed to assign her a job. Haku is characterized as the lover, the love interest of the hero. From the beginning, Chihiro is taken by Haku’s chivalry when she is becoming a spirit and tenderly embraces her and then swears to protect her. He shows her kindness by taking her to see her parents, even though it is forbidden. When Haku falls ill, Chihiro feels as though the world is crashing down around her and vows to do anything to heal him. She bravely takes a train ride to meet Zaneba, who tells her the illness will be lifted because of the love they have for each other. One of the most emotional scenes is when she remembers a time that Haku saved her in the river, reminding him of his name, effectively lifting the hold Yubaba has over him that is making him an indentured servant.20 As dragon Haku twists among the clouds and night sky, painted in a dazzling blue theme, happy and exciting music swells. Flashbacks are shown, a shoe in the water, back to Chihiro’s face, then a flash of water, back to Chihiro’s face, a wide-eyed Chihiro in the water, and back to Chihiro’s face. Excited, Chihiro leans over and tells Haku about a time that she was saved from drowning in the Kohaku River when the water brought her to shore. Haku remembers 20 Spirited Away 1:52:55-1:55:15 Page 11 Lucas 12 he is the spirit of that river and that is his real name. Symbolically, dragon Haku shatters into metallic petals into human. Touched, Haku and Chihiro clutch each other with sparkling eyes and the wind rushing around them. The angles keep switching, to his face, to her face, to a wide view, to the landscape, and this shows the excitement of the realization that they are free. Highly emotional scenes between lovers falling through the air is found in a few different animes, acting as a metaphor for falling in love. In Weathering with You, the hero, Hodaka, goes to save Hina from her endless sleep in the sky. As they fall back down to Earth, he passionately professes how much he cares for her and puts her above all else. Similar camera angles are used, and the scenes reflect each other closely. Young, passionate, true love is a universal trope that is recreated in anime through specific scenes and unique plots. Lin is characterized as the caregiver, who is the mother-figure in Spirited Away. Initially, Lin does not like Chihiro since she is an outsider, human, and child, but grows fond of her when she sees how hardworking and determined Chihiro is. She takes her under her wing, demonstrated by the scene when Haku assigns Lin to take care of Chihiro.21 In front of everyone, Lin whines about having to take care of Chihiro, but once out of sight, her scowl melts into a sweet smile, and her entire demeanor changes as she says, “I can't believe you pulled it off. You're such a dope. I was really worried.”22 Calling Chihiro a dope shows that she still annoys Lin, but the line suggests that she really cares about her. She offers Chihiro help and encourages her to come to her if she needs anything. Relieved and finally able to put down her shield, Chihiro bows her head and admits she does not feel good. Overwhelmed, Chihiro starts to cry while Lin rubs her back comfortingly. She becomes a confidant of Chihiro, and Chihiro trusts 21 22 Spirited Away 41:56-44:41 Spirited Away 43:05 Page 12 Lucas 13 Lin. Lin keeps Chihiro up-to-date about the events of the bathhouse, like informing her about noface. Maternal figures can be found in stories across cultures and time, and serve as an important tool and mode of strength for the protagonist. The basic storyline of the tale consists of the archetypes interconnected actions. Kristin Wardetzky generalizes that the storyline involves: Isolation of the protagonist—meeting with the victim of the villainy—mediation— beginning counteraction—departure—meeting with the helper—reaction of the protagonist to the helper—receipt of magic object—spatial transference, guidance— struggle—victory—restoration—return home.23 This storyline reflects standard tales and reinforces the existence of a universal archetypal structure, and can be found in most anime works, regardless of the content. There is no doubt that the film lacks a logical storyline, yet something gives it structure, that “something” being an archetypical storyline. At the beginning of the film, Chihiro is isolated from her family when they are turned into pigs, and because of this is also the victim of the villainy. Haku acts as the catalyst for the mediation, urging her to start her journey to save her parents as beginning counteraction. She departs from her hiding spot into the spirit world to find Kamaji, who acts as a helper by giving her a job. Chihiro is given a magic object, a hair tie, from Zaneba who guides her about how to save Haku and defeat Yubaba. She struggles against Yubaba and solves her riddle, a victory, and her family is restored and returns through the tunnel from the spirit world back to the human realm. Even though Spirited Away is so unique, the storyline still follows a basic universal structure that is found in others. 23 Wardetzky, Kristin. "The Structure and Interpretation of Fairy Tales Composed by Children." The Journal of American Folklore 103, no. 408 (1990): 157-76. doi:10.2307/541853. Page 13 Lucas 14 Ultimately, what these archetypes and universal storylines reveal is a truth about what Jung coined the “ego,” the executor of the personality and the center of the ongoing experience of one’s self in the psyche, or our interior/soul. Ego in Japan has a slightly different definition since it is more based in experience rather than knowledge or theoretical deduction. It is the experiences and encounters of the bathhouse that transform Chihiro from a sulky, immature, girl to a strong-willed young lady, not a single realization. Furthermore, in the Japanese psyche, the boundary between the conscious and unconscious is not as clearly defined, and so the ego is buried deeper within the psyche. Since it is more in the unconscious, it is harder to describe what is going on, so more involvement within is required. Spirited Away is a great sample of what an illogical, unconscious realm might look like as one’s self goes through a transformative process. This is why the film is presented in a rather non-linear fashion, and more of a shift from scenes to characters to encounters that all build up to gradually transform Chihiro along the way. This is a distinctively Japanese idea: jinden, denoting, “a state in which various elements flow spontaneously.”24 Spirited Away is such a wonderful example of anime being a new form of folklore in Japan because although its popularity is worldwide, “touching on concepts of the unconscious from a Western perspective, it also speaks to a particularly Japanese sensibility.”25 It continues to reach the hearts and minds of Western and Eastern culture alike, and finds a place in the psyche as a myth or fairy tale. The enduring transformative journey through the enchanted bathhouse is a not a situation everyone can relate to, but the strife of growing up is, which makes it a particularly effective tool to captivate audiences worldwide. The story pays tribute to the concept 24 25 Yama, Megumi. “Spirited Away and its depiction of Japanese traditional culture.” Yama, Megumi. “Spirited Away and its depiction of Japanese traditional culture.” Page 14 Lucas 15 of the folkloresque by contributing to pop culture in Japan’s own form of folklore being built by this anime tradition. The mystical settings align with other well-known tales throughout the world, while still demonstrating Japan’s emphasis and appreciation for cultivated nature and satoyama landscapes. The characters reflect universal archetypes as proposed by Jung, and in doing so allow the audience to resonate well with the different types depending on their unique experiences. Likewise, the narrative itself follows a typical pattern while still displaying a distinctly Japanese layout, jinden. Ultimately, this serves to reveal truths about the inner ego and psyche of the people of Japan and both their consistencies with the rest of the world and their differences. Page 15 Lucas 16 Figures Figure 1. Yubaba. Anime-planet.com. Page 16 Lucas 17 Bibliography Foster, Michael Dylan. 2016. Introduction: The Challenge of the Folkloresque. Utah State University Press, Page 5. Foster, Michael Dylan, and Kijin Shinonome. 2015. The Book of Yō kai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. University of California Press. Jung, C.G. 2014. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated by R.F.C. Hull, Second ed., Volume Nine, Routledge. Komatsu, Kazuhiko. 2002. Kamikakushi to nihon jin. Kadokawa Sophia bunko. Tokyo: Kadokawa-shoten. Knight, Catering. December 2010. The Discourse of ‘‘Encultured Nature’’ in Japan: The Concept of Satoyama and its Role in 21st-Century Nature Conservation. Vol. 34, pp. 421-441. Spirited Away (2001) Directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Tokuma Shoten, Studio Ghibli (Japan). Wardetzky, Kristin. "The Structure and Interpretation of Fairy Tales Composed by Children." The Journal of American Folklore 103, no. 408 (1990): 157-76. doi:10.2307/541853. Waude, Adam. "How Carl Jung's Archetypes And Collective Consciousness Affect Our Psyche." Psychologist World. January 22, 2016. Accessed April 26, 2019. https://www.psychologistworld.com/cognitive/carl-jung-analytical-psychology. Yama, Megumi. “Spirited Away and its depiction of Japanese traditional culture.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Jungian Film Studies, edited by Luke Hockley, Routledge, 2018, 254-262. Page 17