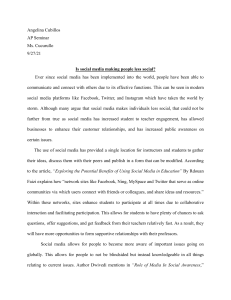

EuroMed Journal of Business Consumer behavior on Facebook : Does consumer participation bring positive consumer evaluation of the brand? Ching-Wei Ho Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) Article information: To cite this document: Ching-Wei Ho , (2014),"Consumer behavior on Facebook ", EuroMed Journal of Business, Vol. 9 Iss 3 pp. 252 - 267 Permanent link to this document: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-12-2013-0057 Downloaded on: 02 May 2015, At: 22:54 (PT) References: this document contains references to 76 other documents. To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 434 times since 2014* Users who downloaded this article also downloaded: Sertan Kabadayi, Katherine Price, (2014),"Consumer – brand engagement on Facebook: liking and commenting behaviors", Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, Vol. 8 Iss 3 pp. 203-223 http:// dx.doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-12-2013-0081 Johanna Gummerus, Veronica Liljander, Emil Weman, Minna Pihlström, (2012),"Customer engagement in a Facebook brand community", Management Research Review, Vol. 35 Iss 9 pp. 857-877 http:// dx.doi.org/10.1108/01409171211256578 Hsin Chen, Anastasia Papazafeiropoulou, Ta-Kang Chen, Yanqing Duan, Hsiu-Wen Liu, (2014),"Exploring the commercial value of social networks: Enhancing consumers’ brand experience through Facebook pages", Journal of Enterprise Information Management, Vol. 27 Iss 5 pp. 576-598 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ JEIM-05-2013-0019 Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by 514603 [] For Authors If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation. *Related content and download information correct at time of download. The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/1450-2194.htm EMJB 9,3 Consumer behavior on Facebook Does consumer participation bring positive consumer evaluation of the brand? 252 Ching-Wei Ho Department of Marketing, Feng Chia University, Taichung, Taiwan Received 10 December 2013 Revised 24 January 2014 Abstract 28 March 2014 Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate consumers’ voluntary behaviors on Facebook Accepted 2 May 2014 Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) through exploring how members’ community participation affects consumer citizenship behaviors toward the brand. The study also provided further insight into the mediating effect by considering brand trust and community identification. Design/methodology/approach – This research begins by developing a framework to describe and examine the relationship among Facebook participants, brand trust, community identification, and consumer citizenship behaviors. Furthermore, it tests the mediating effects of brand trust and community identification on the relationship between Facebook participation and consumer citizenship behaviors. The model and hypotheses in this study employ structural equation modeling with survey data. Findings – First, this study reveals consumers’ community participation on Facebook has directly positive and significant effects on brand trust and community identification. Second, this research confirms that brand trust has directly positive and significant effects on community identification. Third, this study found that brand trust and community identification play a mediating role between Facebook participation and consumer citizenship behaviors. Research limitations/implications – The sample comprised primarily young adults, which may not be completely generalizable to the population at large. This study examined a specific form of virtual community, Facebook, so the results cannot be ascribed to other formats of brand community. Originality/value – The issue of consumer’ voluntary behavior on social networking sites has become more and more important. This study proposed an exclusive model of the process by which the paper can consider consumers’ voluntary behaviors on Facebook from participation to consumer citizenship behavior toward the brand. This finding can be viewed as pioneering, setting a benchmark for further research. Keywords Trust, Identification, Community participation, Citizenship behaviors, Facebook community Paper type Research paper EuroMed Journal of Business Vol. 9 No. 3, 2014 pp. 252-267 r Emerald Group Publishing Limited 1450-2194 DOI 10.1108/EMJB-12-2013-0057 1. Introduction Currently, social networks have become extremely popular; they are defined as networks of friends for social or professional interactions (Trusov et al., 2009). Social networking is considered a tool that supports both electronic marketing and viral marketing and enables the process of building connections to a network or social circle (Zarella, 2010). Social networking enables connections with a network of people who share common interests or goals (Hsu, 2012) and affords companies the possibility of mapping social connections to expand relationships and spread information (Boyd and Ellison, 2007; Cross and Parker, 2004). Of all the social networks, Facebook is the most popular and claims to have attracted more than 751 million active monthly users (as of March 2013) since starting in February 2004 (www.facebook.com); Facebook has become the top social networking site based on number of users and volume of access or use (Hsu, 2012). Facebook has changed consumer behavior; for example, consumers dedicate almost one-third of their time to social networking (Lang, 2010) and half of these active users Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) log on every day. Thus, companies and brand players find it necessary to maintain a brand presence somewhere on Facebook. Therefore, the Facebook fan page as a brand community on Facebook was established, where fans and consumers can communicate and interact with companies or brands using the “Like” or “Comment” option. According to Hsu (2012), the Facebook community has the following characteristics: shares company, product, or service information; communicates and shares marketing messages; expands networks; and receives feedback updates, which provide members with as many opportunities as possible to become involved and participate in the community. Community participation is an important issue that influences participants’ behaviors (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010; Ouwersloot and Odekerken-Schröder, 2008; Royo-Vela and Casamassima, 2011). However, in previous studies, the consequence of participation has usually been discussed in terms of loyalty (e.g. Casalo et al., 2007); less mentioned is the specific behavioral form, such as voluntary consumer behaviors that will benefit the brand (i.e. consumer citizenship behaviors). Actually, when a member is willing to participate, regardless of passive or active mode, in a Facebook community, it is a kind of voluntary consumer behavior. Thus, would voluntary behavior in participation in a Facebook community affect a consumer’s citizenship behavior and how? This question signals the gap that this study attempts to close. The objectives of the current empirical study are three: first, to enhance and examine the knowledge and the relationships among Facebook participants, brand trust, community identification, and consumer citizenship behaviors. It hypothesizes that the more members participate in a Facebook brand community, the more likely they are to trust this brand and/or identify as a community member, and then to exhibit consumer citizenship behaviors that benefit the brand; second, to examine the mediating effects of brand trust and community identification; third, to propose an model of the process by which we can consider consumers’ voluntary behaviors on Facebook from participation to consumer citizenship behaviors toward the brand. This research begins by developing a framework to describe and examine the relationship among Facebook participants, brand trust, community identification, and consumer citizenship behaviors. Furthermore, it tests the mediating effects of brand trust and community identification on the relationship between Facebook participation and consumer citizenship behaviors. The model and hypotheses in this study employ structural equation modeling (SEM) with survey data. Finally, this paper concludes with a discussion of the marketing significance, theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research. 2. Literature and hypotheses development 2.1 Facebook participation and trust Facebook community participation can be discussed in terms of interacting and cooperating with community elements and participating in joint activities (Algesheimer et al., 2005; Matzler et al., 2011). Regarding the community element, according to McAlexander et al. (2002), “a community is made up of its entities and the relationships among them” (p. 38). That is, a Facebook community comprises entities (i.e. the brand, products, customers, and the company). Therefore, community participation can be considered the interactions and communications among elements of a brand community. Meanwhile, Facebook fans control their participation level because of the voluntary nature of the brand community. Members participate for free and there are no clear requirements for their contributions to ongoing communication. Some members in the Consumer behavior on Facebook 253 EMJB 9,3 Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) 254 Facebook community get involved with more active communication, while others focus on watching the continuing communication around shared brand interests (Cothrel and Williams, 1999; Ridings et al., 2002). When a customer logs on to a Facebook community to become a member and comments, shares experiences, interacts with marketers, asks questions about the brand or product, or answers comments, that member is participating in the community’s activities. During these interactions, meaningful experiences, useful information, and other valuable resources are being shared among members so that ties are strengthened in such communities (Laroche et al., 2013) and increase individual willingness to participate in the communities. According to Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001), brand trust is “the willingness of the average consumer to rely on the ability of the brand to perform its stated function” (p. 82). In a situation of uncertainty, brand trust plays an important role in reducing uncertainty. A trusted brand makes consumers feel comfortable (Chiu et al., 2010; Doney and Cannon, 1997; Gefen et al., 2003; Moorman et al., 1992; Pavlou et al., 2007). Holmes (1991) argued that repeated interaction and maintaining long-term relationships are key factors in building trust. Enhancing relationships with customers and elements of the brand community can enhance relationships and increase contacts between the brand and the customers so that brand trust is influenced positively (Laroche et al., 2013). Kang et al. (2014) also approved that active participation on Facebook fan pages has a positive influence on brand trust. Therefore, in terms of the degree to which Facebook members frequently participate and interact within the brand community, trust in the brand makes members feel more comfortable. Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is put forward: H1. The greater the level of participation in a Facebook brand community, the more likely it is that members will trust the brand. 2.2 Facebook participation and identification Facebook community participation can be discussed in terms of acting in ways that endorse the community and enhance its value for members and others (Algesheimer et al., 2005; Matzler et al., 2011). Community member participation is commonly classified into two different modes: passive (participation) and active (interaction) (Kozinets, 1999; Qu and Lee, 2011; Wang and Fesenmaier, 2004). Prior research has suggested that even passive participation, which includes lurking, also relates to members’ sense of identification (Arnett et al., 2003). Some academics have suggested that active lurking, which means actively participating but without interacting, enables members to better evaluate online communications and develop a sense of identification (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2003; Carlson et al., 2008). Moreover, several academics, such as Bergami and Bagozzi (2000), Gruen et al. (2000), and McWilliam (2000), have suggested that if members become psychologically attached to the community, they are more likely to behave in accordance with community values. According to Lembke and Wilson (1998), community identification exists when a member feels, thinks, and behaves like a member of the community, which means that the member distinguishes a community identity from a self-identity. Some researchers have proposed that community identification involves both cognitive self-categorization and affective commitment (e.g. Algesheimer et al., 2005). Cognitive self-categorization occurs through consumers’ comparison of their own defining characteristics to those that define the community (Bergami and Bagozzi, 2000). Affective commitment takes this process a step further into feelings of attachment and belongingness (Algesheimer et al., 2005; McAlexander et al., 2002). Consumers who engage in a variety of social activities have direct access to other members and can mediate the flow of resources in the community. Thus, participation in brand community activities makes them more like insiders (Tsai and Pai, 2012). Therefore, once an individual participates in a Facebook community and becomes a fan of a brand page, no matter whether in passive or active mode, he or she will be affected by the community values and gradually develop identification with this brand community. Consolidating the theoretical arguments reviewed so far, we hypothesize that: Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) H2. The greater the level of participation in a Facebook brand community, the greater the brand community identification. Analysis of the relationship between trust and identification is not found in the extant literature. However, based on the above discussions about brand trust and community identification, we have proposed that a member who trusts and relies on a brand will also be emotionally attached and identify as a part of the brand community. That is, a positive relationship exists between brand trust and community identification. Thus: H3. The higher the level of trust toward a brand, the greater the brand community identification. 2.3 Consumer citizenship behaviors Customer citizenship behaviors comprise voluntary customer behaviors that benefit the firm and go beyond customer role expectations (Gruen, 1995). Customers perform citizenship behaviors at their sole discretion (Bettencourt, 1997; Groth, 2005) and customer citizenship behaviors provide extraordinary value to the firm. The literature suggests various forms of customer citizenship behaviors, such as positive word-of-mouth (WOM) communication, constructive involvement in suggesting service improvements, and other polite and courteous behaviors (Bettencourt, 1997; Rosenbaum and Massiah, 2007). Based on the concept of organizational citizenship behavior (Bateman and Organ, 1983), consumers are more likely to express their support for an organization (e.g. participate in a brand community) by engaging in in-role behaviors like purchasing products from the company (Ahearne et al., 2005) and extra-role behaviors, such as making recommendations to others and engaging in positive WOM (Anderson et al., 2004; Bettencourt, 1997). In most recent researches, customer citizenship behaviors have been discussed and applied in the online behavior context, e.g. Anaza and Zhao (2013) and Anaza (2014). Social exchange theory (Blau, 1964) suggests that the association between the consumer and organization can be seen as social exchanges in which consumers give back a positive gain (e.g. identity or experience) from a sense of personal obligation or gratitude by providing positive feedback to the organization (Lii and Lee, 2012). In the context of the online community (e.g. a Facebook community), social exchange theory can also be applied to demonstrate the relationships between members and other parties. These relationships are seen as exchanges in which a receiver reciprocates a positive personal effect by providing positive outcomes to the other party, such as citizenship behaviors (Chen et al., 2010). When consumers participate and interact within a Facebook community, they may gain more information by sharing or psychologically supporting and gradually identify themselves as part of this Consumer behavior on Facebook 255 EMJB 9,3 256 community; they will be more likely to respond with reciprocal behavior that may benefit the community. Citizenship behaviors may be one type of benefit. In addition, Blau (1964) pointed out that social exchange is based on the expectation of trust and reciprocation, as the exact nature of the return is left unspecified. Morgan and Hunt (1994) theorized that trust is the key mediating variable between the antecedents and consequences of developing a long-term customer relationship. Consumers’ willingness to exhibit citizenship behavior to a brand presents their intent to maintain a relationship with the brand. Thus, when consumers participate in a Facebook community, they may gain more information or become familiar with the brand and gradually trust the brand; therefore, they are more likely to engage in reciprocal behavior that may benefit the brand. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed: Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) H4. The greater the brand trust, the more likely it is that consumers will exhibit in-role and extra-role behaviors that support the community. H5. The greater the community identification, the more likely it is that consumers will exhibit in-role and extra-role behaviors that support the company. The integrated theoretical framework as represented by H1H5 is shown in Figure 1. 3. Research method 3.1 Sample To date, social network users are more concentrated in Asia. Currently, almost 90 percent of Asian brands use social networks as a marketing platform, and 75 percent of these brands have developed social networking strategies that have been in use for longer than a year (Pon and Wang, 2012). Therefore, the data used to examine the hypotheses were collected in Taiwan from Facebook community members. As Zhao (2011) suggested, Facebook communities include four forms: public celebrity communities, individual sharing communities, online game or app software communities, and company/brand communities. In the top 100 Taiwanese Facebook communities in 2011, company/brand communities (e.g. seven-Eleven, Starbucks, Rakuten Ichiba Taiwan) had a 33 percent share (Zhao and Yang, 2011). The purpose of this research was to explore whether Facebook participation leads to citizenship behaviors toward the brand; thus, only the community for companies/ brands was considered in this study. Moreover, the sample of respondents was obtained based on the following qualification: Respondents should have been registered and active in at least one Facebook brand community for longer than three H4a Trust H1 In-role behavior H4b Participation H3 H5a H2 Figure 1. The conceptual model Identification Ex-role behavior H5b Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) months. According to Chin and Newsted (1999), a sample size of 150-200 is required to attain reliable coefficient values using partial least squares (PLS) analysis (Hur et al., 2011). Hair et al. (2010) suggested that the ratio of observations to the independent variable should not fall below 5 (5:1), although the preferred ratio is 10 respondents for each independent variable (minimum ratio of observation to variables is 10:1) (Yap et al., 2012). Hence, bearing in mind the 15 variables to be used in SEM, this study required a minimum sample size of 150 respondents. 3.2 Data collection method Data were collected by a structured questionnaire developed for the research and adapted from those used in previous studies. As the target population in this study was members of the Facebook brand community, the questionnaire was distributed through several posts on Facebook and PTT. PTT is the local social networking website in Taiwan with the largest scales and longest history. It provides a platform for discussing Facebook (like the “Facebook forum”) and distributes virtual questionnaires. Gathering data through this site can be more efficient than just gathering data through Facebook. We asked participants to keep in mind a company/ brand Facebook community in which they were members and that they followed while answering the questions. Participants were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity in relation to their returned questionnaires. Self-administered questionnaires with the assistance of a support letter were used to ensure a good response rate and reduce non-sampling bias in the survey process. An effort was made to randomize data collection at different times of the day and week. At the end of the data collection period, 232 questionnaires were collected with 26 missing values. That is, 206 fully completed questionnaires were used for the data analysis. 3.3 Measurement of variables The survey questionnaire was developed by adapting measures from a variety of studies. Participation in Facebook was measured through three items adapted from Qu and Lee (2011) and Tsai and Pai (2012). To measure brand trust, we used the threeitem scale proposed by Laroche et al. (2013), and to measure community identification, we used the three-item scale proposed by Bergami and Bagozzi (2000) and Tsai and Pai (2012). The construct of in-role behavior consisted of three items adapted from Putrevu and Lord (1994). The measures for the extra-role behavior construct consisted of three items adapted from de Matos et al. (2009). All items for assessing the constructs employed a seven-point Likert scale indicating the extent of agreement or disagreement with the item. The items for each construct and their measurement scales are presented in Table I. 3.4 Data analysis This study used PLS to test the hypotheses and analyze the data. The PLS algorithm allows each indicator to vary in terms of how much it contributes to the composite score of the latent variable, instead of assuming equal weight for all indicators of a scale (Chin et al., 2003; Hur et al., 2011). According to Anderson and Swaminathan (2011), PLS path modeling is commonly used in marketing (Henning-Thurau et al., 2007), international business (Henseler et al., 2009), and information systems (Al-Gahtani et al., 2007; Burton-Jones and Hubona, 2006) studies, necessitating simultaneous estimation of the factor loadings of the measurement model and path coefficients of the structural model. This study used PLS rather than other SEM Consumer behavior on Facebook 257 EMJB 9,3 258 Construct Measurement items Participation in Facebook (Par) I often watch the FB page activities I actively participate in the FB activities I frequently interact with other FB members My brand gives me everything that I expect out of the product I rely on my brand My brand never disappoints me I feel strong ties to this community I see myself as a part of this community I feel emotionally attached to this community It is very possible that I will buy the brand I will consider buying the brand the next time I need this product I will try this brand I will recommend this brand to my relatives and friends I will tell my relatives and friends about the good experience with this brand I am willing to join the activity hold by the brand in the future Brand trust (Trust) Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) Community identification (CI) In-role behavior (In) Ex-role behavior (Ex) Table I. Constructs and their measurement items Loading a CR AVE 0.829 0.838 0.810 0.77 0.87 0.68 0.928 0.927 0.884 0.902 0.921 0.908 0.759 0.90 0.94 0.83 0.90 0.94 0.83 0.72 0.84 0.64 0.68 0.82 0.61 0.832 0.801 0.799 0.871 0.660 methods (i.e. LISREL, AMOS) because the PLS approach places minimal restrictions on sample size and residual distribution (Hur et al., 2011; Phang et al., 2006). 4. Results 4.1 Demographic profile of respondents Of the 206 respondents, 46 percent was male while 54 percent was female. In terms of age, 62 percent was 20-30 years old, and 29 percent was under 20; these two groups accounted for the largest portion of the sample, followed by those aged 31-40 years (6 percent). Most of the respondents (45 percent) had been members of the brand community for one to two years, 28 percent for two years or longer, and 27 percent for less than one year. 4.2 Measurement model We used the two-step approach as described by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). We first assessed reliability and convergent validity as shown in Table I and then discriminant validity as illustrated in Table II. To examine reliability, Cronbach’s a revealed that all constructs showed a value above 0.6 (the bar adopted by Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). Par Trust CI In Ex Table II. Correlation matrix Mean SD Par Trust CI In Ex 3.26 2.66 3.51 2.93 3.30 1.273 0.933 1.216 1.153 1.282 0.83 0.39 0.54 0.45 0.58 0.91 0.55 0.62 0.65 0.91 0.59 0.73 0.80 0.71 0.78 Note: Diagonals represent the square root of the average variance extracted while the other entries represent the correlations Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) To test for convergent validity, composite reliability (CR), factor loading, and average variance extracted (AVE) were examined. The measures are acceptable if an individual item loading is 40.7, CR exceeds 0.7, and AVE is 40.5 (Gefen et al., 2000). To examine the discriminant validity of the constructs, this study used the Fornell and Lacker (1981) criterion whereby the average variance shared between each construct and its measures should be greater than the variance shared between the construct and other constructs. As shown in Table II, the correlations for each construct are less than the square root of AVE for the indicators measuring that construct, indicating adequate discriminant validity. Consumer behavior on Facebook 259 4.3 Structural model The explanatory power of the structural model is evaluated by looking at the R2 values. From Figure 2, the R2 values range from 0.154 to 0.625, which suggests that the modeled variables explain 15.4 to 62.5 percent of the variance of the respective dependent variables. From Figure 2, Facebook participation exerts a significant and positive influence on both brand trust (H1, b ¼ 0.393, po0.001) and community identification (H2, b ¼ 0.383, po0.001). Therefore, H1 and H2 are both supported. The model predicted the path from brand trust to community identification (H3) and shows a significant and positive relationship between them (b ¼ 0.402, po0.001). Thus, H3 gains supported. In addition, the paths from brand trust have a significant and positive influence on both in-role behavior (H4a, b ¼ 0.418, po0.001) and extra-role behavior (H4b, b ¼ 0.361, po0.001). Meanwhile, the paths from community identification have a significant and positive influence on both in-role behavior (H5a, b ¼ 0.358, po0.001) and extra-role behavior (H5b, b ¼ 0.532, po0.001). Thus, both H4 and H5 are fully supported. The seven paths examined in the structural model are summarized in Table III. The mediating effects of brand trust and community identification were tested. As seen in Figure 3, the direct path between Facebook participation and in-role and extra-role behavior are both significant. After introducing brand trust as a mediator, the indirect path for the effect of participation on in-role behavior is significant and stronger than the direct path (b ¼ 0.3904b ¼ 0.255). Moreover, the indirect path for the effect of participation on extra-role behavior is also significant and stronger than Trust R 2 =0.154 0.418*** In-role R 2 =0.468 0.393*** 0.358*** Facebook Participation 0.402*** 0.361*** 0.383*** Identification R 2 =0.429 Significance Note: ***p<0.001 0.532*** Ex-role R 2 =0.625 Figure 2. Results of the structural model analysis EMJB 9,3 260 Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) Table III. Results of testing Hypothesized relationship H1 H2 H3 H4a H4b H5a H5b Participation-Trust Participation-Identification Trust-Identification Trust-In-role Trust-Ex-role Identification-In-role Identification-Ex-role Coefficient T-value 0.393*** 0.383*** 0.402*** 0.418*** 0.361*** 0.358*** 0.532*** 3.969 4.319 5.009 5.122 5.083 3.796 7.467 Supported Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Note: *** po0.001 In-role behavior 0.255*** 0.516*** Facebook Participation 0.390*** 0.375*** Figure 3. The mediating effect of brand trust Significance Brand Trust R 2 = 0.434 R 2 = 0.152 0.517*** R 2 = 0.559 Ex-role behavior Note: ***p<0.001 the direct path (b ¼ 0.3904b ¼ 0.375). Therefore, in this test, brand trust indicates a partial mediating effect on Facebook participation and both citizenship behaviors. The same procedure was repeated to test the mediating effect of community identification in the relationship between Facebook participation and both in-role and extra-role behavior. The results differ slightly. As seen in Figure 4, the direct path between Facebook participation and in-role behavior is insignificant. After introducing community identification as a mediator, the indirect path for the effect of participation on in-role behavior is significant. This result suggests that community identification has a fully mediating effect on participation and in-role behavior. Nevertheless, regarding the relationship between participation and extra-role behavior, the indirect path for the effect of participation on extra-role behavior is significant and stronger than the direct path (b ¼ 0.5414b ¼ 0.269). Thus, community identification indicates a partial mediating effect on Facebook participation and extra-role behavior. 5. Discussions and conclusions The purpose of this study was to demonstrate consumers’ voluntary behaviors on Facebook through exploring how members’ community participation affects consumer citizenship behaviors toward the brand. The study also provided further insight into the mediating effect by considering brand trust and community identification. The study showed that members’ voluntary participation on Facebook can enhance In-role behavior 0.192 0.485*** Facebook Participation 0.541*** Community Identification 0.592*** R 2 = 0.373 R 2 = 0.293 Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) Insignificance 261 R 2 = 0.596 0.269*** Significance Consumer behavior on Facebook Ex-role behavior Note: ***p<0.001 brand trust, community identification, and citizenship behaviors. The results offer important contributions and implications for both marketing academics and practitioners. 5.1 Theoretical implications First, this study reveals that consumers’ community participation on Facebook has directly positive and significant effects on brand trust and community identification. These findings demonstrate that the crucial purpose of Facebook brand communities is to bring people with certain similar characteristics together and to facilitate communication among them. This is consistent with Laroche et al.’s (2013) research on the social media-based brand community-trust relationship and the research on community participation-identification relationship from Qu and Lee (2011) and Tsai and Pai (2012). Second, this research confirms that brand trust has directly positive and significant effects on community identification. This relationship has not been described in previous literature and this finding can be viewed as pioneering, setting a benchmark for further research. In addition, almost all the previous literature has examined the relationship between community participation and identification only in a direct path (e.g. Qu and Lee, 2011; Tsai and Pai, 2012); however, this study considered brand trust as a mediator between Facebook community participation and community identification and verified its mediation effects. The results showed that when a participant in a brand community trusts the brand, the trust facilitates the participant in identifying himself or herself as part of this brand community. This is also seen as pioneering and can provide further paths of inquiry for future researchers. Above two discussions achieved the first objective of this research. Third, this study found that brand trust and community identification play a mediating role between Facebook participation and consumer citizenship behaviors. This reached the second objective of this research. The role of brand trust and community identification as an antecedent of citizenship behavior has seldom been addressed (e.g. Lii et al., 2013; Lii and Lee, 2012). This study suggested that the mediation effect of brand trust is similar to both citizenship behaviors, but differs depending on the type of citizenship behavior. Specifically, community identification mediates fully between community participation and in-role behavior, whereas it Figure 4. The mediating effect of community identification EMJB 9,3 Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) 262 partially mediates between participation and extra-role behavior. One possible reason for this is that, in this study, in-role behavior was represented by buying products or brands, which is related to economic behavior. Normally, consumers’ behaviors will be considered more when they involve “money.” Therefore, after community participation, having community identification is like double-checking for consumers to present their appropriate in-role behaviors. Fourth, current researches (e.g. Chen et al., 2012; Gironda and Korgaonkar, 2014; Hoadley et al., 2010; Ko, 2013; Pate and Adams, 2013; Velleghem et al., 2012) have indicated that the issue of consumer’ voluntary behavior on social networking sites has become more and more important. This study proposed an exclusive model of the process by which we can consider consumers’ voluntary behaviors on Facebook from participation to consumer citizenship behaviors toward the brand. We tested and validated this model and found support for the hypotheses in the context of a social media-based brand community. Thus, the greater the brand trust, the more likely it is that consumers exhibit both in-role and extra-role behaviors that support the community. In addition, the greater the community identification, the more likely it is that consumers exhibit both in-role and extra-role behaviors that support the company. This finding satisfied the third objective of this research and can be viewed as pioneering, setting a benchmark for further research. 5.2 Managerial implications The findings in this study have practical implications for marketing and consumer behavior practices. First, it is clear that consumer participation in a Facebook brand community has the potential to exert a significant positive influence on brand trust and community identification. Accordingly, managers and e-marketers who recognize the essential role of Facebook should make every effort to engage in active management of their brand community on Facebook. Second, the study suggests new insights for practitioners to enhance their customerbrand relationship and related consumer voluntary behaviors. This helps marketing managers identify brand trust as influential on both in-role and extra-role behaviors. Managers should focus on maintaining brand commitment and undertake careful communication management to ensure that all available information is trustworthy. In addition, community identification is another powerful influence on consumer citizenship behavior, particularly in that the behavior is related to economic intention (e.g. purchasing products or brands). Brand community managers should help members develop an emotional bond with the brand community. Sustained efforts to give these members pleasure and enjoyment and to ensure that they have a close attachment to the fan page will increase their identification with the brand community. Third, this study helps practitioners in their involvement with the Facebook community. The popularity of Facebook and its vast potential reach, being in no fixed location and carrying a low cost, motivates marketers to try to use it in different ways. The model and findings in this study confirm that by building a Facebook community, and by strengthening brand trust and community identification, marketers can increase consumers’ in-role and extra-role behaviors. 5.3 Limitations and future research The following limitations of this study should be considered. When addressing these limitations, we also suggest directions for future research. First, this study adopted Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) brand trust and community identification as antecedents of consumer citizenship behaviors. Other relational variables, such as consumer commitment, could also be considered and examined as antecedents. Second, our sample comprised primarily young adults (under 30 years old); hence, their responses may not be completely generalizable to the population at large. Finally, this study examined a specific form of virtual community, Facebook, so the results cannot be ascribed to other formats of brand community. Future researchers can explore consumer behaviors and brand community with regard to different types of social media with specific brand settings. References Ahearne, M., Bhattacharya, C.B. and Gruen, T. (2005), “Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: expanding the role of relationship marketing”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 90 No. 3, pp. 574-585. Al-Gahtani, S.S., Hubona, G.S. and Wang, J. (2007), “Information technology (IT) in Saudi Arabia: culture and the acceptance and use of IT”, Information & Management, Vol. 44 No. 8, pp. 681-691. Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U.M. and Herrmann, A. (2005), “The social influence of brand community: evidence from European car clubs”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 69 No. 3, pp. 19-34. Anaza, N.A. (2014), “Personality antecedents of customer citizenship behaviors in online shopping situations”, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 31 No. 4, pp. 251-263. Anaza, N.A. and Zhao, J. (2013), “Encounter-based antecedents of e-customer citizenship behaviors”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 130-140. Anderson, E.W., Fornell, C.F. and Mazvancheryl, S.K. (2004), “Customer satisfaction and shareholder value”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 68 No. 4, pp. 172-185. Anderson, J.C. and Gerbing, D.W. (1988), “Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 103 No. 3, pp. 411-423. Anderson, R.E. and Swaminathan, S. (2011), “Customer satisfaction and loyalty in e-markets: a PLS path modeling approach”, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 221-234. Arnett, D.B., German, S.D. and Hunt, S.D. (2003), “The identity salience model of relationship marketing success: the case of nonprofit marketing”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 67 No. 2, pp. 89-105. Bagozzi, R.P. and Yi, Y. (1988), “On the evaluation of structural equation models”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 74-94. Bateman, T.S. and Organ, D.W. (1983), “Job satisfaction and the good solider: the relationship between affect and employee ‘citizenship’”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 26 No. 4, pp. 587-595. Bergami, M. and Bagozzi, R.P. (2000), “Self-categorization affective commitment and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in the organization”, British Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 39 No. 4, pp. 555-557. Bettencourt, L.A. (1997), “Customer voluntary performance: customers as partners in service delivery”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 73 No. 3, pp. 383-406. Bhattacharya, C.B. and Sen, S. (2003), “Consumer-company identification: a framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 67 No. 2, pp. 76-88. Blau, P.M. (1964), Exchange and Power in Social Life, Wiley, New York, NY. Consumer behavior on Facebook 263 EMJB 9,3 Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) 264 Boyd, D. and Ellison, N. (2007), “Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship”, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 210-230. Burton-Jones, A. and Hubona, G.S. (2006), “The mediation of external variables in the technology acceptance model”, Information & Management, Vol. 43 No. 6, pp. 706-717. Carlson, B.D., Suter, T.A. and Brown, T.J. (2008), “Social versus psychological brand community: the role of psychological sense of brand community”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 61 No. 4, pp. 284-291. Casalo, L.V., Flavian, C. and Guinaliu, M. (2007), “The impact of participation in virtual brand communities on consumer trust and loyalty”, Online Information Review, Vol. 31 No. 6, pp. 775-792. Chaudhuri, A. and Holbrook, M.B. (2001), “The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 65 No. 2, pp. 81-93. Chen, M.J., Chen, C.D. and Farn, C.K. (2010), “Exploring determinants of citizenship behavior on virtual communities of consumption: the perspective of social exchange theory”, International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 195-205. Chen, Y.J., Lo, C.Y. and Yang, H.L. (2012), “Top 100 of Taiwan website in 2012”, Business Next, No. 214, March 1, pp. 121-125. Chin, W.W. and Newsted, P.R. (1999), “Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares”, in Hoyle, R.H. (Ed.), Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 307-341. Chin, W.W., Marcolin, B.L. and Newsted, P.R. (2003), “A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic mail emotion/adoption study”, Information Systems Research, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 189-217. Chiu, C.M., Huang, H.Y. and Yen, C.H. (2010), “Antecedents of online trust in online auctions”, Electronic Commerce Research and Application, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 148-159. Cothrel, J.P. and Williams, R.L. (1999), “On-line communities: helping them form and grow”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 54-60. Cross, R. and Parker, A. (2004), The Hidden Power of Social Networks, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. de Matos, C.A., Rossi, C.A.V., Veiga, R.T. and Voeira, V.A. (2009), “Consumer reaction to service failure and recovery: the moderating role of attitude toward complaining”, Journal of Service Marketing, Vol. 23 No. 7, pp. 462-475. Doney, P.M. and Cannon, J.P. (1997), “An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 61 No. 2, pp. 35-51. Fornell, C. and Lacker, D.F. (1981), “Evaluation structural equation models with unobserved variables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50. Gefen, D., Karahanna, E. and Straub, D.W. (2003), “Trust and TAM in online shopping: an integrated model”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 51-90. Gefen, D., Straub, D. and Boudreau, M.C. (2000), “Structural equation modeling and regression: guidelines for research practice”, Communications of the Association for Information Systems, Vol. 7 No. 7, pp. 1-78. Gironda, J.T. and Korgaonkar, P.K. (2014), “Understanding consumers’ social networking site usage”, Journal of Marketing Management, doi:10.1080/0267257X.2013.851106. Groth, M. (2005), “Customers as good soldiers: examining citizenship behaviors in internet service deliveries”, Journal of Management, Vol. 31 No. 1, pp. 7-27. Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) Gruen, T.W. (1995), “The outcome set of relationship marketing in consumer markets”, International Business Review, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 447-469. Gruen, T.W., Summers, J.O. and Acito, F. (2000), “Relationship marketing activities, commitment, and membership behaviors in professional associations”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 64 No. 3, pp. 34-49. Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J. and Anderson, R.E. (2010), Multivariate Data Analysis, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Henning-Thurau, T., Henning, V. and Sattler, H. (2007), “Consumer file sharing of motion pictures”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 71 No. 4, pp. 1-18. Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M. and Sinkovics, R.R. (2009), “The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing”, in Sinkovics R.R. and Ghauri, P.N. (Eds), Advances in International Marketing, Vol. 20, JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, pp. 277-320. Hoadley, C.M., Xu, H., Lee, J.J. and Rosson, M.B. (2010), “Privacy as information access and illusory control: the case of the Facebook news feed privacy outcry”, Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 50-60. Holmes, J.G. (1991), “Trust and the appraisal process in close relationship”, in Jones, W.H. and Perlman, D. (Eds), Advances in Personal Relationships, Vol. 2, Jessica Kingsley, London, pp. 57-104. Hsu, Y.L. (2012), “Facebook as international eMarketing strategy of Taiwan hotels”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 31 No. 2012, pp. 972-980. Hur, W.M., Ahn, K.H. and Kim, M. (2011), “Building brand loyalty through managing brand community commitment”, Management Decision, Vol. 49 No. 7, pp. 1194-1213. Kang, J., Tang, L. and Fiore, A.M. (2014), “Enhancing consumer-brand relationships on restaurant Facebook fan pages: maximizing consumer benefits and increasing active participation”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 145-155. Kaplan, A.M. and Haenlein, M. (2010), “Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media”, Business Horizons, Vol. 53 No. 1, pp. 59-68. Ko, H.C. (2013), “The determinants of continuous use of social networking sites: an empirical study on Taiwanese journal-type bloggers’ continuous self-disclosure behavior”, Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 103-111. Kozinets, R.V. (1999), “E-Tribalized marketing? the strategic implications of virtual communities of consumption”, European Management Journal, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 252-264. Lang, B. (2010), “Ipsos OTX study: people spend more than half their day consuming media”, The Wrap, September 20, available at: www.thewrap.com/media/column-post/peoplespend-more-12-day-consuming-media-study-finds-21005/ (accessed 25 July 2014). Laroche, M., Habibi, M.R. and Richard, M.O. (2013), “To be or not to be in social media: how brand loyalty is affected by social media?”, International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 33 No. 1, pp. 76-82. Lembke, S. and Wilson, M.G. (1998), “Putting the team into teamwork: alternative theoretical contributions for contemporary management practice”, Human Relations, Vol. 51 No. 7, pp. 927-944. Lii, Y.S. and Lee, M. (2012), “Doing right leads to doing well: when the type of CSR and reputation interact to affect consumer evaluations of the firm”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 105 No. 1, pp. 69-81. Lii, Y.S., Chien, C.S., Pant, A. and Lee, M. (2013), “The challenges of long-distance relationships: the effects of psychological distance between service provider and consumer on the efforts to recover from service failure”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 43 No. 6, pp. 1121-1135. Consumer behavior on Facebook 265 EMJB 9,3 Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) 266 McAlexander, J.H., Schouten, W.J. and Koening, F.H. (2002), “Building brand community”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 66 No. 1, pp. 38-54. McWilliam, G. (2000), “Building stronger brands through online communities”, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 41 No. 3, pp. 43-54. Matzler, K., Pichler, E., Fuller, J. and Mooradian, T.A. (2011), “Personality, person-brand fit, and brand community: an investigation of individuals, brands, and brand community”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 27 Nos 9/10, pp. 874-890. Moorman, C., Zaltman, G. and Deshpande, R. (1992), “Relationships between providers and users of market research: the dynamics of trust within and between organizations”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 29 No. 3, pp. 314-328. Morgan, R.M. and Hunt, S.D. (1994), “The commitment trust theory of marketing relationships”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58 No. 3, pp. 20-38. Ouwersloot, H. and Odekerken-Schröder, G. (2008), “Who’s who in brand communities – and why?”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 42 Nos 5/6, pp. 571-585. Pate, S.S. and Adams, M. (2013), “The influence of social networking sites on buying behaviors of Millennials”, Atlantic Marketing Journal, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 92-108. Pavlou, P.A., Liang, H. and Xue, Y. (2007), “Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: a principal-agent perspective”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 31 No. 1, pp. 105-136. Phang, C.W., Sutanto, J., Kankanhalli, A., Li, Y., Tan, B.C.Y. and Teo, H.H. (2006), “Senior citizens’ acceptance of information systems: a study in the context of e-government services”, IEEE Transactions Engineering Management, Vol. 53 No. 4, pp. 555-569. Pon, Y.P. and Wang, C.J. (2012), “Which keyword let brand control the digital trend?”, Brand News, November 6, available at: www.brain.com.tw/News/RealNewsContent.aspx? ID ¼ 17819 (accessed July 25, 2014). Putrevu, S. and Lord, K.R. (1994), “Comparative and noncomparative advertising: attitudinal effects under cognitive and affective involvement conditions”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp. 77-90. Qu, H. and Lee, H. (2011), “Travelers’ social identification and membership behaviors in online travel community”, Tourism Management, Vol. 32 No. 6, pp. 1262-1270. Ridings, C.M., Gefen, D. and Arinze, B. (2002), “Some antecedents and effects of trust in virtual communities”, Journal of Strategic Information Systems, Vol. 11 Nos 3/4, pp. 271-295. Rosenbaum, M.S. and Massiah, C.A. (2007), “When customers receive support from other customers: exploring the influence of intercustomer social support on customer voluntary performance”, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 9 No. 3, pp. 257-270. Royo-Vela, M. and Casamassima, P. (2011), “The influence of belonging to virtual brand communities on consumers’ affective commitment, satisfaction and word-of-mouth advertising The ZARA case”, Online Information Review, Vol. 35 No. 4, pp. 517-542. Trusov, M., Bucklin, R.E. and Pauwels, K. (2009), “Effects of word-of-mouth versus traditional marketing: findings from an internet social networking site”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 73 No. 5, pp. 90-102. Tsai, H.T. and Pai, P. (2012), “Positive and negative aspects of online community cultivation: implications for online stores’ relationship management”, Information & Management, Vol. 49 No. 2, pp. 111-117. Velleghem, S.V., Thijs, D. and Ruyck, T.D. (2012), “Social media around the world 2012”, available at: www.slideshare.net/InSitesConsulting/social-media-aroundthe-world-2012by-insites-consulting. Downloaded by FREIE UNIVERSITAT BERLIN At 22:54 02 May 2015 (PT) Wang, Y. and Fesenmaier, D.R. (2004), “Towards understanding members’ general participation in and active contribution to an online travel community”, Tourism Management, Vol. 25 No. 6, pp. 709-722. www.facebook.com (2013), “Statistics”, May 22, available at: www.facebook.com/press/info.php? statistics (accessed July 25, 2014). Yap, B.W., Ramayah, T. and Shahidan, W.N.W. (2012), “Satisfaction and trust on customer loyalty: a PLS approach”, Business Strategy Series, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 154-167. Zarella, D. (2010), The Social Media Marketing Book, O’Reilly Media Inc., Sebastapol, CA. Zhao, D.Y. (2011), “The competition among 15 thousand fan pages”, Business Next, 1 October No. 209, pp. 130-133. Zhao, D.Y. and Yang, H.N. (2011), “2011 Top 100 Facebook fan pages”, Business Next, 1 October No. 209, pp. 134-135. About the author Dr Ching-Wei Ho, PhD is an Assistant Professor at the Feng Chia University. His research interests focus on branding, retailing marketing, and service marketing. His research has contributed to academic journals and conference proceedings. Dr Ching-Wei Ho can be contacted at: chingwei1121@yahoo.com.tw To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints Consumer behavior on Facebook 267