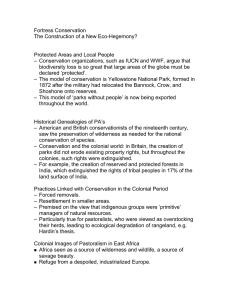

(Book) Friends for life Chapter 3 urban dwellers and protected areas Natural allies

advertisement