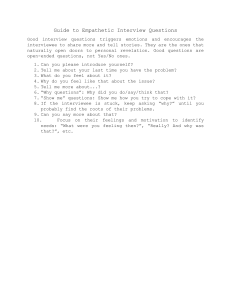

2/28/2019 Interviews LING401: Research Methods Lecture 6 Oksana Afitska Today’s lecture Today we’re going to do the following: • Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the interview method 2 1 2/28/2019 Discussion • What are interviews good at doing? Why? • What are they not so good at doing? Why? • How could you use interviews to do research in an area of linguistics you’re interested in? • In what ways could interviews be used inappropriately? Why? • What different types of interview can you think of (e.g., in terms of duration, style, number of people, purposes, etc.)? 3 Interview format Interviews can be in several different formats. They can be face-to-face interactions, larger group interviews/focus groups, or can be held over the phone, done via Skype, or via email. Let’s look at the three main types of interview which researchers normally talk about… 4 2 2/28/2019 Interview design Structured Semi-structured Open/Unstructured 5 The Standardised/Structured Interview Questions exactly the same for each interviewee Questions asked in the same order to each interviewee Interviewer has a complete list of questions on their sheet; just asks each one in turn Like a spoken questionnaire Short answers, often ‘Yes/No’ questions, ticking boxes Like a market research interview Good for collecting QUANTITATIVE data 6 3 2/28/2019 The Semi-Standardised/Semi-Structured Interview Researcher will have SOME of the questions on their sheet only Researcher will ask different/additional questions, depending on each interviewee’s responses to questions on sheet So each interview different to some extent Order of questions may vary Very different from a questionnaire Often much longer answers Used for collecting QUALITATIVE data 7 The Non-Standardised/Unstructured/Open Interview ‘Here interviewers simply have a list of topics which they want the respondent to talk about, but are free to phrase the questions as they wish, ask them in any order that seems sensible…, and even join in the conversation by discussing what they think of the topic themselves’ (Fielding & Thomas 2001: 124) 8 4 2/28/2019 Why use qualitative interviews? To explore beliefs, experiences ‘If you choose qualitative interviewing it may be because [your research questions explore] people’s knowledge, views, understandings, interpretations, experiences, and interactions…. Perhaps most importantly, you will be interested in their perceptions.’ (Mason 2002: 63) 9 Why use qualitative interviews? To uncover beliefs and generate lengthy accounts Compare: ‘Is honesty important to you?’ Yes/No [STRUCTURED] vs. ‘Tell me about an experience when a family member was dishonest’ [SEMI-STRUCTURED] 10 5 2/28/2019 Why use qualitative interviews? As part of a mixed methods study You may use qualitative interviews in tandem with other methods. For instance, many studies of teachers’ beliefs observe the teachers in their classrooms, and then use things that happened in the lessons they observed as the basis for their qualitative interview questions. 11 Why use qualitative interviews? To allow the interviewee more control, making the research EMIC Interviewees have far more freedom to change the direction of the interview than they would if you were following a traditional structured interview format, or a questionnaire. While emic research allows us to interpret things through the eyes of the informant, etic enquiry involves interpreting things through the eyes of the researcher Hence the interviewee can set the agenda to some extent, raising issues important to him/her 12 6 2/28/2019 Strengths of interviews: To avoid reactivity • They avoid the reactivity problem: ‘Because retrospective accounts allow researchers to get a glimpse into writers’ strategies and decisions after the fact, they have the advantage of allowing writers to explain and reflect on their decisions without interfering directly with their attention to the task, freeing the writer from the “cognitive load”…that the concurrent verbalization of a think-aloud would require.’ (Greene & Higgins 1994: 118) 13 Weaknesses of interviews 14 7 2/28/2019 Weaknesses of interviewing: Will interviewees tell the truth? For instance, if we observed a teacher in their classroom, and then interviewed the teacher about what we saw, we might ask why she didn’t pay much attention to a student in the lesson. The teacher could reply: ‘That student prefers to be left alone to work things out for herself’. But there is always the possibility that this isn’t the real reason… Can you think of a couple of other reasons the teacher might not pay student x much attention? 15 Weaknesses of interviewing: Interviewee behaviour, personality Respondents might be over-polite, shy, or anxious to impress the interviewer. They might ‘tell the interviewer what they think she wants to hear’ 16 8 2/28/2019 Weaknesses of interviewing: The tendency to forget and simplify accounts of behaviour ‘Retrospective accounts of writing rely on people’s memory, and it appears clear that people remember relatively little of the momentto-moment thinking and action they have engaged in. […] The farther the separation between the event and the recall, the more likely that the account will contain… conventionalization and simplification…. Details drop out and new ones are added.’ (Prior 2004: 184-5) 17 Weaknesses of interviewing: An example of forgetting • Tomlinson (1984: 434) cites Donald Murray, a writing scholar who was asked to account for his composing behaviour, and who found that he had forgotten because he wasn’t asked immediately after he had finished writing: “It is certainly true that debriefing by the researcher at some distance from the time of writing was virtually useless. I could not remember why I had done that. In fact, the researcher knows the text better than I do.” (Murray 1983:70) 18 9 2/28/2019 Weaknesses of interviewing: Beliefs, not ‘facts’ ‘…the interview method is heavily dependent on people’s capacities to verbalize, interact, conceptualize and remember. It is important not to treat understandings generated in an interview… as though you were simply excavating facts’. (Mason 2002: 64) 19 Getting more specific when interviewing • Greene & Higgins (1994) therefore suggest more specific interviews are to be preferred: ‘Since…writers have a tendency to generalize information, we need to provide prompts or cues that can help writers better access detailed information…. The use of concrete examples, contextual cues, and “critical incidents”…is helpful for this purpose. […] Writers may have a hard time explaining their strategies when they do not have a specific experience or example in mind.’ (pp.123-4) 20 10 2/28/2019 Weaknesses of interviewing: Interviewee cooperation ‘…some informants may be more willing and/or able to introspect than others: hence while CS6, for instance, carefully accounted for every single citation in his fairly lengthy text, others tended to account for their citations in “clumps” (‘This citation is doing X…And so are all the others on that page’).’ (Harwood 2009: 517) 21 Different types of questions Have a look at the interview extract on your handout from Richards’ (2003) book and try to identify 5 different types of questions; that is, questions which play different functions. 22 11 2/28/2019 Different types of questions 1. Opening: …it’s often a good idea to begin by inviting a fairly lengthy response. Spradley (1979) describes this as a ‘grand tour’ approach (e.g. ‘Talk me through that lesson’)…. This often provides a natural springboard for further questions… [Extract 01-2] 2. Check/reflect: If you’re in any doubt about whether you’ve understood something, it’s always worth checking this or reflecting a statement back to the speaker. This may also prompt the speaker to develop a point further…. [Extract 08-9] 3. Follow-up: When the speaker has raised something or perhaps given a subtle indication that there is more to be discovered on this topic, the interviewer may decide 23 to follow it up…. [Extract 12-13] Different types of questions 4. Probe: …points will emerge during the interview that demand more careful excavation…. The most straightforward method is by direct invitation to add more detail, or through the use of directed questions. You can use Wh- questions, but too many of these produce a staccato effect in the interview and can cast it in too interrogatory a light. [Extract 18-19] Indirect probes can be very useful, especially where topics are sensitive. Questions like ‘What do people think about X?’ can be even more revealing than ‘What do you think about X?’…. 5. Structuring:…it may be necessary to mark a shift of topic by using structuring moves such as, ‘Can we move on to…’ (Richards 2003: 56-7) 24 12 2/28/2019 More about different types of interview questions… 25 The fixed alternative question The respondent chooses from 2 or more alternatives, such as agree—disagree, or yes— no. Sometimes a 3rd option, like don’t know or undecided is also included. Cohen et al (2000: 275) give the following example of a fixed alternative question: Do you feel it is against the interests of a school to make public its examination results? Yes No Don’t know What are the pros and cons of using fixed alternative questions? 26 13 2/28/2019 Fixed alternative questions: pros and cons Pros guaranteed that every interviewee will be asked the same question, which gives the interview greater reliability than a more open-ended, unstructured format easier to code and interpret the results Cons superficial the informants might not find any of the [3] choices suitable, and provide an answer which isn’t what they believe ‘These weaknesses can be overcome, however, if the items are written with care, mixed with open-ended ones, and used in conjunction with probes on the part of the 27 interviewer.’ (Cohen et al 2000: 275) Open-ended questions Open-ended questions identify the question topic, but place ‘no…restrictions on either the content or the manner of the interviewee’s reply’ (Cohen et al 2000: 275). Cohen et al give the following example of an open-ended question: What kind of television programmes do you most prefer to watch? What are the pros and cons of using openended questions? 28 14 2/28/2019 Open-ended questions: pros and cons Pros flexible ‘allow the interviewer to probe so that she may go into more depth if she chooses, or to clear up any misunderstandings’ (Cohen et al 2000: 275) ‘they allow the interviewer to make a truer assessment of what the respondent really believes’ (p.275) ‘Open-ended situations can also result in unexpected or unanticipated answers which may suggest hitherto unthought-of relationships or hypotheses’ (p.275) Cons may be more difficult to measure and quantify than fixed response questions 29 The scale question Cohen et al (2000: 275) give the following example of a scale question: Attendance at school after the age of 14 should be voluntary: Strongly agree Agree Undecided Disagree Strongly disagree What’s the obvious type of follow-up question which comes next? 30 15 2/28/2019 Problematic interview questions To finish, let’s have a look at some interview questions that can be seen as problematic… These questions are from interviews with political science lecturers about: (i) The types of different texts they write (e.g., journal articles, articles for newspapers, politics blogs, etc.); and (ii) What being an ‘author’ or ‘writer’ means to them Why are the strengths and weaknesses of these questions? How could you improve them by rewriting them? 31 Problematic questions (1) I’ve asked you lots of questions today and last time. What are the right questions to ask a political scientist about writing? Have I been asking you the right questions? 32 16 2/28/2019 Problematic questions (1) Strengths: May enable the interviewee space to talk about what the crucial issues are FOR HIM/HER, rather than answer researcher’s questions about what RESEARCHER thinks are the important issues So enables exploration of important issues (to the interviewee) the researcher didn’t anticipate Weaknesses: ‘Meaning of life’-type question? (‘What are the right questions to ask about writing’? How/Where do you start answering that?!) Will interviewee really admit: ‘No, you’ve been asking me all the wrong questions’? 33 Asks two questions at once Problematic questions (2) Tell me about all the different kinds of things you write. 34 17 2/28/2019 Problematic questions (2) Tell me about all the different kinds of things you write. Strengths: Good that the interviewer is not presuming the interviewee only write a narrow range of genres (books, journal articles), and is prepared to explore more widely. The interviewee may write more genres than interviewer has anticipated. Weaknesses: Another very broad question How do we know the interviewee will be able to recall all the genres? (Better to give the question in advance of the interview for interviewee to think about?) Write in what context? When using, for instance, social media? When in role as an academic, writing articles? In public or in private? 35 ‘Tell me about…’. Tell you what? Problematic questions (3) [All of this question is put on a prompt card and handed to the interviewee] How does the experience of writing these different types of texts compare in terms of the following? how satisfied you are with the outcome the sense of fulfillment/achievement it gives you the level of freedom to express what you really think level of prestige the publication provides level of response the text has had how easy/difficult it was to write and publish it how easy/difficult it was to find the right language to express yourself how enjoyable or not each was to write the types of pressures (if any) you felt while working on it audience (how wide / specialist?) how these texts represent you as an author to your audience how these texts represent you as a person to your audience 36 any other important dimension of difference 18 2/28/2019 Problematic questions (3): Strengths Strengths: They could generate lots of detail. They could generate accounts of SPECIFIC experiences of writing. Some prompts may elicit lengthy stories, e.g., ‘level of response the text has had’ may lead to stories about people who have written to the interviewee about their books and articles The final item (‘any other important dimension of difference’) allows the interviewee the space to talk about an issue the interviewer hasn’t anticipated. Better chance of emic data emerging. 37 Problematic questions (3): Weaknesses Weaknesses: Lots of different things to talk about; where does one begin? So question intimidating? They’re big questions; but won’t they just be answered superficially— especially as they come with lots of OTHER questions? Doesn’t this encourage the interviewee to only VERY BRIEFLY talk about (too many) things? If we want interviewees to talk about specific texts, don’t we need these texts in front of us? Don’t we need to have asked these questions in advance to allow interviewees to reflect and recall exactly what happened/plan what they want to tell us? Some are very specific questions, but seem unlikely to elicit specific detail (e.g., ‘how easy/difficult it was to find the right language to express yourself’) Some seem pretty deep (e.g., ‘how these texts represent you as an author to your audience’). Will everyone understand the meaning of the question? Even if they will, wouldn’t they need time to think about their 38 answers? 19 2/28/2019 Problematic questions (4) [All of this question is put on a prompt card and handed to the interviewee] What is your reaction to these statements by academic writers? Writing is about a means of saying who you are, and locating yourself in the world, and representing yourself in the world…So my way of representing myself in the world has been through writing. So that it’s been an essential part of me. Writing is not about who I am; it’s simply a matter of getting the job done. 39 Problematic questions (4) Strengths: An attempt is made to avoid bias by giving interviewees a quote from one person who sees writing as part of his identity and another quote which sees writing in purely instrumental terms. The interviewee can ‘take sides’ with one or the other—or neither. (In contrast to only asking whether writing is part of the interviewee’s identity— expecting a ‘yes’ answer) Weaknesses: How much depth will responses to these statements elicit? The interviewee is being asked to make vague, generalised statements about what writing means to 40 him/her. 20 2/28/2019 TASK 2: Practising qualitative interviewing In your group suggest a topic/problem for which collecting data via the interview procedure could be appropriate. Individually develop 5 interview questions for this topic. Interview one person from another group using your questions. Compare your questions (and answers) with the rest of your group. What makes some questions ‘better’ than others? What did you learn about interviewing? 41 Good and bad interviewing Watch the following: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9t_hYjAKww&src_vid=FGH2tYuXf0s&feature= iv&annotation_id=annotation_554130 42 21 2/28/2019 TASK 3: Reading Hermanowicz, J.C. (2002) The great interview: 25 strategies for studying people in bed. Qualitative Sociology 25(4): 479-499. And the chapters on interviewing in: Cohen, L. et al (2007) Research Methods in Education (7th ed.). London: Routledge Falmer. Richards, K. (2003) Qualitative Inquiry in TESOL. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 43 References Cohen, L. et al (2000) Research Methods in Education (5th ed.). London: RoutledgeFalmer. Fielding, N. & Thomas, H. (2001) Qualitative interviewing. In N Gilbert (ed.), Researching Social Life (2nd ed.). London: Sage. Greene, S. & Higgins, L. (1994) “Once upon a time”: the use of retrospective accounts in building theory in composition. In P. Smagorinsky (ed.), Speaking About Writing: Reflections on Research Methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp.115-140. Harwood, N. (2009) An interview-based study of the functions of citations in academic writing across two disciplines. Journal of Pragmatics 41(3): 497-518. Mason, J. (2002) Qualitative Researching (2nd ed.). London: Sage. Murray, D. (1983) Response of a laboratory rat—or, being protocoled. College Composition & Communication 34: 169-172. Prior, P. (2004) Tracing process: how texts come into being. In C. Bazerman & P. Prior (eds.), What Writing Does and How It Does It. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 167-200. Richards, K. (2003) Qualitative Inquiry in TESOL. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Spradley, J. (1979) The Ethnographic Interview. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Tomlinson, B. (1984) Talking about the composing process: the limitations of retrospective accounts. Written Communication 1(4): 429-445. 44 22