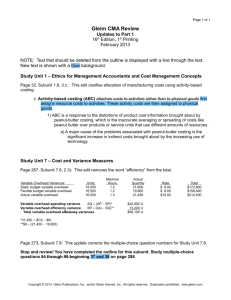

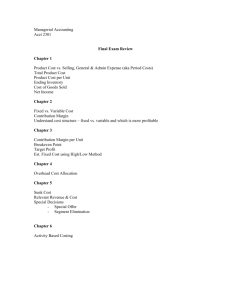

Activity-Based Costing Solutions: Cost Drivers & Allocation

advertisement