A study on Medical Negligence - Reassessing the Apportionment of Liabilities

advertisement

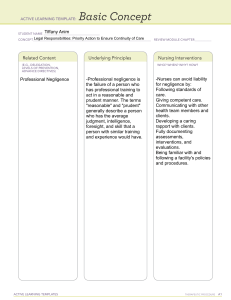

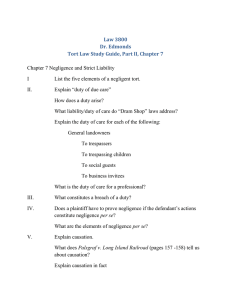

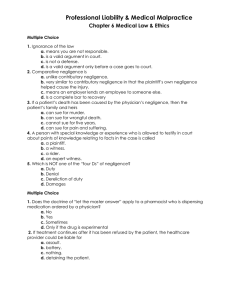

MASTER OF LAW : LEGAL RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY LWM701 (B) PREPARED BY NAMES Nor Fadlina Mohd Lutfi Irna Shahana Samsudin Nur Syafiq bin Kamaruzzaman Mohd Hairulanuar Suli : GROUP 4 STUDENT ID NUMBER 2021613106 2021679142 2021667966 2021661476 RESEARCH PROPOSAL TITLE : A Study on Medical Negligence: Reassessing the Proportions of Liabilities between Hospitals & Medical Practitioners PREPARED FOR : DR. NADZRIAH AHMAD SUBMISSION DATE : 11th February 2022 RESEARCH PROPOSAL 1. RESEARCH TITLE A Study on Medical Negligence: Reassessing the Proportion of Liabilities between Hospital and Medical Practitioners. 2. BACKGROUND/INTRODUCTION Over the recent years, there has been an increase in the number of medical negligence cases in Malaysia by both the government and private hospitals. There were unequivocally efforts carried out by both sectors to mitigate the negligence cases as well as improving the healthcare and treatment given to patients. However, the question now is, whether or not it is sufficient as mitigating factors in reducing the liabilities by both medical practitioners and healthcare facilities and/or hospitals be it government or private. According to the Health Ministry’s official figures, there was an increase of malpractice such as wrong surgeries, transfusion, unintended retention of foreign objects, wrongful and/or improper advice and diagnosis, misrepresentation as well as wrong medication prescriptions which can be seen in below schedule. INCIDENTS 2016 2018 Wrong surgeries 6 11 Unintended retention of foreign objects (URFOs) 27 32 Transfusion errors 40 47 Medication errors 3104 3741 Patient falls (adults) 2374 3547 Patient falls (children) 441 696 Health Minister Datuk Seri Dr Dzulkefly Ahmad, 2019, The Malaysia Reserve News 1 However, comprehensive annual statistics on medical negligence claims are not available in Malaysia since such data are not collected systematically in this country. However, there are indications of an upward trend1. Ministry of Health statistics reveal that between 1986 and 1990, 61 medical negligence claims were made against government physicians, averaging about 12 claims per year. The figures stood at 20 and 16 in 1991 and 1992 respectively. It is believed that many more cases are actually settled out of court.2 Radhakrishnan, the Malaysian Medical Protection Society’s legal adviser said, “Although official statistics on the exact number of medical accidents in clinics and hospitals were not available, the increase could be seen from the rise in premiums paid by doctors for protection against malpractice suits”3. Also Milton Lum, The Medical Defence Malaysia (MDM) board member said, based on the increase in indemnity subscriptions, there seems to be an increase in the number of litigations against doctors. He further added Health Ministry data showed an increase from 29 to 56 cases against doctors from 2006 to 2011 (Chin, 2013). The main issue in medical negligence has always been whether there was a breach of standard of care by the medical practitioner expected of a skilled man in his/her expertise area. One of the other issues as well is whether distinction should be made between diagnosis and treatment and duty to advise of risks. However, more often than not, there is also an issue of to what extent a hospital and/or the medical facilities holds liability towards the aggrieved patient besides the doctor him/herself. It has been a perpetual challenge for human ingenuity to resolve conflicting social interests, particularly when the nature and the content of these interests undergo a continuous change in the process of social evolution according to Ali Mohammad Matta, the Associate Professor of Kulliyyah of Laws, International Islamic University Malaysia.4 The cases of medical negligence found their way to court rooms which saw an unequivocal liability imposed on doctors for the negligent performance of their duties.5 He added that medical history is replete with cases of negligence such as the cases of wrong diagnosis, wrong treatment, swabs left inside the body of the 1 Siti Naaisha Hanbali, Solmaz Khodapanahandeh (2014), A Review of Medical Malpractice Issues in Malaysia under Tort Litigation System retrieved from Global Journal of Health Science; Vol. 6, No. 4; 2014, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e665/a4f5c126822e7f2313348a004e0f8863590d.pdf?_ga=2.6940082.1261550269.164 4512757-494349080.1644512757 2 Ibid 3 Ibid 4 Medical Negligence: New Issues And Their Resolution [2000] 3 MLJ Clxxxiv 5 Ibid 2 patient during the course of surgery and performance of surgery. Historically, hospitals were considered as charitable institutions and were afforded absolute immunity from tortious liability, says Prof Dr Puteri Nemie Jahn Kassim and Su Wai Mon @ Faridah in their article6. Hence, being a charitable institution, hospital authorities could not be vicariously liable for the negligence of members of their medical staff, whether professionally qualified or not, as the element of control over the method of working was lacking. However, in modern cases, a different view has prevailed. Professional qualified staff such as consultants, radiographers and anaesthetists have been held to be employees of the hospital authority for the purposes of vicarious liability. The doctrine of vicarious liability was introduced under the common law. This doctrine is a form of strict, secondary liability that arises under the common law doctrine of agency, namely, the responsibility of the superior for the acts of their subordinate. It is based on the theory that 'the master should be held responsible for the wrongful or negligent acts of their servants. The relationship is naturally that of employment between master and servant or employer and employee and between principal and agent. In other words, employers are vicariously liable for the torts which are committed by their employees in the course of employment. In the healthcare context, the doctrine provides that all healthcare providers will be vicariously liable for the acts and conducts of their employees such as doctors, nurses and medical attendants provided that the employee was acting 'in the course of employment'. Thus, a hospital can be held to be vicariously liable for its doctors’ negligence provided that it can be shown that the they were employed by the hospital at the material time of the alleged negligence and that the negligence occurred within the scope of the staff's employment with the hospital. However, there are also “non-delegable duties” principles adopted by the Malaysian law from the UK position of the law which are very much distinct from “vicarious liability”. Now the question is, to what extent does the hospital assume the liability in cases of medical negligence in comparison to its medical practitioners and staff? This proposal aims to reassess the apportionment of liabilities between medical practitioners and the hospitals and/or healthcare facilities. 6 The Medical Profession, Societal Demands and Developing Legal Standards [2014] 5 MLJ cxxxvii 3 3. PROBLEM STATEMENT Quite often, even if the plaintiff/claimant (patient) overcomes the substantive law in proving negligence, there are still the difficulties in the procedural law to overcome. In many aspects, the conduct of medical negligence litigation in Malaysia is similar to claims with regards to personal injuries. However, there are some notable differences such as finding suitable expert witnesses and interpreting medical records. According to a report made by the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare on medical malpractice: "Medical malpractice cases are among the most difficult to try. They usually take two or three times longer than other personal injury cases because of the complexity of the expert medical testimony. Thus, although few in total number, they contribute significantly to the congestion and overload of the court system."7 The main problems in civil litigation, particularly medical negligence litigation, are excessive costs, delay8, inequality between the two parties and at the end of it, the outcome is uncertain. If a patient wishes to initiate legal action against the doctor, he has to do it within a specified period of time or else the action will be barred. This is known as the limitation period and the rules are mostly consolidated in the Malaysian Limitation Act 1953 (Act 254). The rationale for imposing limitation periods on actions is to protect the defendants from stale claims and encourage plaintiffs to proceed without unreasonable delay rather than sleeping on their rights. Such will provide finality so that a person can feel confident that after a certain period of time, potential claims are closed against him and he can therefore, manage his affairs accordingly. The basic rule governing any action brought under the law of torts is that the claim cannot be brought after a lapse of six years from the date on which the cause of action accrued9. In torts actionable per se, such as trespass to the person, the cause of action normally accrues at the date of 7 U.S. Dept. of Health, Education & Welfare (HEW), Report of the Secretary's Commission on Medical Malpractice 18 (1973). 8 The main contributor to the costliness of the tort system is the delay involved in the pursuit of a claim. The situation is made worse with regards to medical negligence claims as these cases take a long time to try. For instance, in the case of Dr Chin Yoon Hiap v Ng Eu Khoon & Ors and other appeals [1998] 1 MLJ 57, litigation was initiated on 23 December 1981 whereas the judgment was delivered on 7 November 1997. Altogether, the case took about 16 years to conclude. If the time considered was when the cause of action accrued, that is, 7 January 1976. then the duration would be 21 years. 9 Limitation Act 1953, section 6(1)(a) 4 the defendant's wrong, whereas with torts actionable only on proof of damage, such as negligence, the action accrues when the damage occurs and this is usually not the same time with the defendant’s breach of duty but later. Vicarious Liability refers to a situation where A is liable to C for damage or uy suffered by C due to the negligence or other tort committed by B. A need not have done anything wrongful and A further need not owe a duty of care to C. The most important condition for imposing liability on A as the nature of relationship between A and B and the tort committed by Bis connected to the nature of this relationship. This relationship is usually that of employment between master and servant or employer and employee and between a principal and his agent. Many reasons have been put forward in justification of this doctrine, some of which are that a master is to be held liable for employing a negligent employee; for failure to control the employee; that since the master derives benefit from the employee's services, he should be made liable for any tortious or wrongful conduct of the employee in the performance of his work. Another reason, practical in nature, is because the master would be in a better financial position to compensate the injured third party. He would also be in a better position, in theory at least, to insure against such loss. This last reason ensures, if nothing else, that the third party will in fact receive compensation for his injuries and the doctrine therefore secures actual compensation to the tort victim, and so provides the means for realising loss-distribution in the community. However, any certainty in the justification for the theory is doubtful as held in Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd v Shatwell10 where Lord Pearce said: The doctrine of vicarious liability has not grown from any very clear, logical or legal principle but from social convenience and rough justice. The master having (presumably for his own benefit) employed the servant, and being (presumably) better able to make good any damage which may occasionally result from the arrangement, is answerable to the world at large for all the torts committed by his servant within the scope of it. The doctrine maintains that liability even in respect of acts which the employers had expressly prohibited (see Canadian Pacific Railway v Lockhart 10 [1965] AC 656 at 685. 5 [1942] 2 All ER 464) and even when the employers are guilty of no fault themselves (Staveley Iron & Chemical Co Ltd v Jones [1956] 1 All ER 403). It follows that they are liable for the torts of one servant against another. Certainly, where the employer's business is in the form of public service, such as operating a public bus service, policy dictates that the employer should be liable even for unauthorised acts of his employee. In Cassidy v Ministry of Health11 and Roe v Ministry of for Health12," the courts held that if negligence occurs in a hospital, and the tortfeasors cannot be identified, the hospital will be vicariously liable for the negligence. Lord Denning in Roe stated that the hospital would still be held liable even though the negligence is committed by a part-time employee as the employee is still part of the organisation. Negligent acts of consultants would also render the hospital vicariously liable and in fact the hospital may be independently liable if the negligence of the consultants is due to the hospital's failure in ensuring that it has the recommended basic equipment. An exception would undoubtedly apply to consultants, and surgeons at hospitals where the consultant or surgeon has a contract with the patient that the hospital would not be vicariously liable for any negligence committed by the consultant or surgeon. This would mean that the treatment which is performed by the consultant or surgeon is not on behalf of the hospital but is pursuant to a direct engagement with the patient. It has been suggested that a hospital's liability for the torts committed by its employees’ rests not on the principle of vicarious liability, but the breach of its primary duty to the patients.29 In Tan Eng Siew v Dr Jagjit Singh13 where the plaintiff, a 65-year-old woman, was dissatisfied with the post-surgery care she received from the consultant who had conducted her two hip operations, the court held that a private consultant who has clients of his own, and pays the hospital for using the hospital's facilities such as running a clinic and other operating facilities is not an employee but an independent contractor. It is irrelevant that the private practitioner is a shareholder of the hospital. Thus, the hospital cannot be vicariously liable for any negligent conduct on the part of the consultant. On the issue of whether the hospital could be independently liable to the plaintiff, 11 [1951]1 All ER 574. [1954] 2 QB 66. 13 [2006] 1 MLJ 57 12 6 the court answered in the negative as the hospital only provided the premises and operating facilities which use were paid for by the consultant. No liability could be attached to the hospital as it never had any control over the course or form of treatment, management and care of the plaintiff. Although the ward nurses, medical attendants and physiotherapist were employees of the hospital, these personnel did not commit any tort on the plaintiff. By depending on the tort and common law principles, medical negligence claims toward the doctor nor the vicarious liability was not laid down in Medical Regulations 2017. The problem statement will be focused on legal issues regarding hospital or medical facilities by vicarious liability in medical negligence law suite with an assist of regulations14 and/or act15. 3. RESEARCH QUESTIONS The research questions for this paper are as follows: (i) Does the legal framework in Malaysia, particularly the Private Healthcare Facilities & Services Act 1998 (“PHFSA”), the Private Healthcare Facilitiesand Services (Private Hospitals and Other Private Healthcare Facilities) Regulations 2006 (‘Regulations’) and the Medical Act 1971 provide adequate protection for medical practitioners in cases of medical negligence in Malaysia particularly on determining the proportions of liabilities between hospitals and doctors? (ii) How does referring to the laws in the United Kingdom address the issue of determining the proportions of liabilities between hospitals and doctors in Malaysia? (iii) How to reform the existing law in order to provide clarity on the determination of proportions of liabilities between hospitals and doctors/medical practitioners in cases of medical negligence? 4. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES The research objectives of this paper are : (i) To critically examine the adequacy of legal framework in Malaysia particularly the Private Healthcare Facilities & Services Act 1998 (“PHFSA”), the Private Healthcare Facilitiesand Services (Private Hospitals and Other Private Healthcare Facilities) Regulations 2006 14 15 Medical Regulation 2017. Medical Act 1971. 7 (‘Regulations’) and the Medical Act 1971 in providing legal protection for doctors and medical practitioners in Malaysia in cases of medical negligence. ii) To analyse the courts’ decisions and compare the doctrines/principles applicable in Malaysia and the United Kingdom with regards to determining the proportions of liabilities between medical practitioners and hospitals and/or healthcare facilities in medical negligence cases. (iii) To propose a recommendation in a view of improving the current legal framework governing medical negligence liabilities between medical practitioners and hospitals and/or healthcare facilities in Malaysia. 5. SCOPE & LIMITATIONS Analysis will be focused on two countries’ laws which are Malaysia’s Private Healthcare Facilities & Services Act 1998 (“PHFSA”) and the Private Healthcare Facilities and Services (Private Hospitals and Other Private Healthcare Facilities) Regulations 2006 (‘Regulations’), and the United Kingdom’s laws on medical negligence which mainly found in the country’s reported cases. This study is limited to the proportion of liabilities between both private and government hospitals/health facilities and doctors/medical practitioners serving in the private and government hospitals/health facilities. There a few limitations in data gathering process, where some of them are : 1. tight and unpredictable schedule of the respondent (medical practitioners) 2. late or unresponded emails for interviews from respondents 3. lack of current statistics and information due to emergence of COVID-19 4. Some information is considered confidential and respondents could not disclose them In order to fulfil the requirement of the study, few measures will have to be taken : 1. rescheduling the time of interviews with the respondent 2. looking for new respondents to fill the missing required numbers of respondent lacked 3. by taking informations and statistics before the emergence of COVID-19 but still within 5 years from the current date of study 8 6. LITERATURE REVIEW 6.1 Concepts 6.1.1 Duty of Care In the words of K Kuldeep Singh16, to understand what would constitute medical negligence, it is best to first visit the core foundation of what the medical profession seeks to uphold in its promises, i.e. the oath the doctors and/our medical practitioners take in order to carry out their duties. He added that, the emphasized sections of the oath clearly paved the platform of duty of care and the abstinence of that which is deleterious, making the duty of care and standard of care to the patient always paramount.17 He emphasized that defining medical negligence, regard must first be had to Lord Atkin's ‘neighbour principle' in Donoghue v Stevenson,18 which is self-servient of showing the necessity of ‘proximity' between parties, and which in the field of medicine is described by Hewitt CJ in R v Bateman19 to be: “.... if a person holds himself out as possessing special skill and knowledge and he is consulted as possessing such skill and knowledge by or on behalf of a patient, he owes a duty to the patient to use due caution in undertaking treatment. If he accepts the responsibility and undertakes the treatment and the patient submits to his direction and treatment accordingly he owes a duty to the patient to use diligence, care, knowledge, skill and caution in administering the treatment. No contractual relation is necessary nor is it necessary that the service be rendered for reward.” Thus, the element of duty is established between patient and doctor, arising then into the duty of care owed. Case law has defined that professionals who specialize in particular skilled fields are bound to exercise the skill of similar ordinary competent professionals in the same calling. The standard of care that is required is higher than that of a common person. In Lanphier v Phipos,20 Tindal CJ said that a professional does not undertake to use the highest possible degree of skill; ‘he 16 The Standard of Care in Medical Negligence Cases in Malaysia - Is There a Diminution of Judicial Supervision by Adopting the Bolam Test [2002] 3 MLJ xci 17 Ibid 18 [1932] AC 562 19 [1925] LJKB 791 20 [1838] 8 C & P 475 9 undertakes to bring fair, reasonable and competent degree of skill'. The standard of care is also to be adjudged in accordance with the level of knowledge and practice that the industry has and was prevailing at the time of the breach. This legal position was enunciated by McNair J in Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee,21 : “ In an ordinary case, it is generally said that you judge that by the action of the man in the street. He is the ordinary man…But where you get a situation which involves the use of some special skill or competence, then the test whether there has been negligence or not is not the test of the man on top of Clapham omnibus, because he has not got this special skill. The test is the standard of the ordinary skilled man exercising and professing to have that special skill. A man need not possess the highest expert skill at the risk of being found negligent … it is sufficient if he exercises the ordinary skill of an ordinary competent man exercising that particular art.” The Federal Court found favor in this approach in Kow Nan Seng v Nagamah22 and allowed the medical negligence claim where the court found a failure to exercise the due care and skill of a competent medical man in respect of the treatment and observation of a patient after treatment. In Swamy v Matthews & Anor 23the court held that: “They (the jury) should find him guilty when he had fallen short of the standard of reasonable medical care…” It is thus submitted that, generally, for a case of negligence to arise, there has to be four elements and they are: (1) A duty of care is established and was owed; (2) Such a duty had been breached; (3) This breach precipitates a subsequent or immediate loss, injury or damage; and (4) The foreseeability and remoteness of such a loss, injury or damage was within contemplation or expectations of the parties. 21 [1957] 2 All ER 118 at p 121 [1982] 1 MLJ 128 23 [1968] 1 MLJ 138 (FC) 22 10 6.1.2 Malpractice/ Medical Negligence The Court of Appeal judges in the case of Shalini Kanagaratnam v Pusat Perubatan Universiti Malaya & Anor came to the conclusion that in cases of professional negligence and/or medical negligence, the plaintiff has to prove four elements.24 They are (i) duty of care; (ii) breach of standard of care; (iii) breach of duty of care; and (iv) caused damages. In consequence, the plaintiff has to lead evidence to show the standard of care has been breached. The doctrine of res ipsa loquitur will not ordinarily apply as the plaintiff will have to discharge the legal burden and only after the legal burden has been discharged, the defendant has to satisfy that legal duty was not breached. In delivering his judgement, Mohamad Abazafree Mohd Abbas PK however reminded the court of the remarks made by Denning L.J in Roe v Ministry of Health & others to ensure that the medical practitioners are not placed under unnecessary burden and/or perform their professional tasks in a defensive way.25 His Lordship said: “We should be doing a disservice to the community at large if we were to impose liability on hospitals and doctors for everything that happens to go wrong. Doctors would be led to think more of their own safety than of the good of their patients. Initiative would be stifled and confidence shaken. A proper sense of proportion requires us to have regard to the conditions in which hospitals and doctors have to work. We must insists on due care for the patient at every point, but we must not condemn as negligence that which is only a misadventure”26 6.1.3 Non-Delegable Duties vs Vicarious Liabilities Non-delegable duties, as a concept distinct from vicarious liability, have been established in many Commonwealth jurisdictions. The earliest can be traced to the court judge’s finding in Burnie Port Authority v General Jones Pty Ltd (1994) 120 ALR 4227. In a Malaysian case of Datuk Bandar Dewan Bandaraya Kuala 24 [2016] 6 CLJ 225 [2021] MLJU 1748 26 [1954] 2 All ER 131 27 Mason CJ discerned that non-delegable duties are recognised where there is ‘some element in the relationship between the parties that makes it appropriate to impose on the defendant a duty to ensure that reasonable care and skill is taken for the safety of the persons to whom the duty is owed’ 25 11 Lumpur v Ong Kok Peng & Anor28, where the defendant was held liable for the harm occasioned to the plaintiff in a situation of special danger created by an independent contractor’s extra hazardous act or omission, Malaysia’s then Supreme Court explained that a non-delegable duty of care requires a defendant who engages a contractor to ‘see to it that such duty of care is exercised, whether by his contractor or not, otherwise he would be equally liable as the contractor. The court recognised certain situations where non-delegable duties exist, including the withdrawal of support to neighbouring land and work conducted on a highway. Delivering the main judgement of the Supreme Court in the case of Woodland v swimming Teachers Association and Others29 (hereinafter referred to as “the Woodland’s Case”), Lord Sumption articulated the meaning of ‘non-delegable duty’ as ‘the conventional way of describing those cases in which the ordinary principle is displaced and the duty extends beyond being careful, to procuring the careful performance of work delegated to others’. His Lordship opined that the personal and non-delegable character of the duty is derived from additional factors, such as the claimant’s vulnerability, and the defendant’s custody or control over the former. According to His Lordship, there are five defining features of the cases where the common law imposes a duty upon the defendant.30 Lord Sumption however further cautioned against imposing unreasonable financial burdens on those providing critical public services and said that a non-delegable duty should be imputed to schools only so far as it would be fair, just and reasonable to do so. In analysing the distinction between vicarious liability and non-delegable duties, the 28 [1993] 2 MLJ 234 [2014] AC 537 30 Lord Sumption identified five defining features of the cases where the common law imposes a duty upon the defendant as identified by Lord Sumption:a) The claimant is a patient or a child, or for some other reason is especially vulnerable or dependent on the protection of the defendant against the risk of injury. b) There is an antecedent relationship between the claimant and the defendant, independent of the negligent act or omission itself. It is characteristic of such relationships that they involve an element of control over the claimant, which varies in intensity from one situation to another, but is clearly very substantial in the case of schoolchildren. c) The claimant has no control over how the defendant chooses to perform those obligations, ie whether personally or through employees or through third parties. d) The defendant has delegated to a third party some function which is an integral part of the positive duty which he has assumed towards the claimant; and the third party is exercising, for the purpose of the function thus delegated to him, the defendant’s custody or care of the claimant and the element of control that goes with it. e) The third party has been negligent not in some collateral respect but in the performance of the very function assumed by the defendant and delegated by the defendant to him. 29 12 Singapore Court of Appeal laid out the test in which to demonstrate that a non-delegable duty arises on a particular set of facts, a claimant must minimally be able to satisfy the court either that: (a) the facts fall within one of the established categories of non-delegable duties; or (b) the facts possess all the five features described in Woodland. The appeal court judges also did take Lady Hale’s obiter dictum in the Woodland’s case into consideration and stated that the court will additionally have to take into account the fairness and reasonableness of imposing a non-delegable duty in the particular circumstance, as well as the relevant policy considerations in our local context.31 Although the concept of non-delegable duty has been dismissed as a ‘logical fraud’ and criticised as a departure from basic principles of negligence, our Federal Court judges in the case of Dr Kok Choong Seng & Anor v Soo Cheng Lin and another appeal consider such characterization to be misconceived.32 They quoted Mason J’s remarks in the Australian case, Commonwealth of Australia v Introvigne and further opined that there is no reason why the doctrine of non- delegable duty should not continue to be applied in Malaysia, and that the guiding principles refined in Woodland as a useful starting point.33 6.1.4 Non-Delegable Duties in Hospital Cases Previously, the traditional view as seen in the 1909 case of Hillyer v The Governors of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital was that hospitals do not undertake a duty to treat patients, but only to procure the services of surgeons and other medical professionals. The appellate court judges pointed out that these professionals are not considered servants of the hospital and further remarked that as long as the hospital has taken due care in selecting the professionals and to provide proper facilities at their disposal, the hospital cannot be held liable for the negligence of those professionals in treating the patient.34 In Gold v Essex County Council35 , Lord Greene MR offered a broader basis for the hospital’s liability. According to His Lordship, once the extent of the obligation 31 The Management Corporation Strata Title Plan No 3322 v Tiong Aik Construction Pte Ltd [2016] SGCA 40 [2018] 1 MLJ 685 33 Ibid at para 40 34 [1909] 2 K.B. 820 35 [1942] 2 KB 293 32 13 assumed by a defendant is discovered, he ‘cannot escape liability because he has employed another person, whether a servant or agent, to discharge it on his behalf’. This further leads to His Lordship’s view that the hospital’s duty included the treatment of patients with reasonable care, and such duty is not discharged by delegation whether or not any special skill was involved. In another appellate case of Cassidy v Ministry of Health, Denning LJ dismissed the distinction between those engaged under a contract of service or a contract for services - in other words, between employees and independent contractors - as irrelevant.36 His Lordship had also reiterated the same principle in a later case concerning liability of a hospital for alleged negligence by a part-time anaesthetist.37 6.2 The Practice in Malaysia In considering the position of both government and private hospitals in Malaysia, we shall refer to the Medical Act 1971, Private Healthcare Facilities & Services Act 1998 (“the PHFSA”) and the Private Healthcare Facilities and Services (Private Hospitals and Other Private Healthcare Facilities) Regulations 2006 (‘the Regulations’). Having read reg 11(4) and reg 14(1) of the Regulations, the Federal Court Judges in the Malaysian case of Dr Kok Choong Seng & Anor v Soo Cheng Lin and another appeal do not consider that the relevant legislation warrants the interpretation that private hospitals are mere providers of facilities and not medical treatment.38 In contrast, the legislative scheme clearly envisages that the function of private hospitals includes generally the ‘treatment and care of persons who require medical treatment or suffer from any disease’, and considers the services of medical practitioners as part of that function. 6.3 Comparison between practises in Malaysia & The United Kingdom (UK) In general, the UK uses the Common Law for trials regarding negligence cases. In order to compare the legal framework between Malaysia and the UK, we will be referring to the most recent case of Hopkins v Akramy, Badger Group and NHS Commissioning Board.39 This case is about a claim by the plaintiff, a 2 ½ years old boy who suffers permanent disability allegedly due to the negligence of the first Defendant. 36 [1951] 2 KB 343 Roe v Ministry of Health [1954] 2 QB 66 38 [2018] 1 MLJ 685 39 [2020] EWHC 3445 (QB) 37 14 One of the highlights of this case is within the preliminary issues, where the first Defendant named NHS Commissioning Board as the 3rd Defendant due to their disability of fully compensating the claimant, should the claimant’s claim succeed. The High Court considered whether NHS Primary Care Trust (“PCT”) owed a non-delegable duty of care for health services provided to NHS patients by a private company. Her Honour Judge Melissa Clarke, sitting as a Judge of the High Court, held that it did not. Based on the obiter dicta of the learned judge, she interpreted Section 83 of National Health Service Act 2006 (“NHS”) as it is not the intention of the lawmakers to hold a contractee liable for its contractor's breach of duty of care. She explained one of the test from the case of Woodland v Swimming Teachers Association and Ors40, as one of the landmark cases for non-delegable duty of care in reaffirming her decision. This decision became a controversy in the UK, as the decision means that the rights of the people there are not protected by the law. By deciding the issue in such a manner, this will cause the claimant to suffer from under compensation, in the event of a successful claim. The United Kingdom is similar to Malaysia in terms of its stand. However, the inadequacies there were criticised by legal practitioners in the UK where they recognise the unfairness of the situation, including its inconsistency with the NHS Constitution and public expectation. Some of them proposed the amendment of the law41, and some proposed on setting up indemnity or insurance policy42 that will help ensure that there will be no case of undercompensation should similar situations happen later. In relation to the situation in Malaysia and the UK, it could be well established that they have a similar stand on the position of their governmental body in cases regarding negligence. However, as the legal framework differs, a new method needs to be constructed in order to fill the gap. By taking the opinion and criticisms of both legal practitioners here and there, 40 [2013] UKSC 66 Bennett, S. (2020, December 21). Outsourcing of NHS services: the High Court in JMH v Akramy finds that no non-delegable duty is owed to patients. 1 Chancery Lane retrieved from https://1chancerylane.com/outsourcing-of-nhs-services-the-high-court-in-jmh-v-akramy-finds-that-no-non-delegable-du ty-is-owed-to-patients/ 42 S.W., & V.A.P.B. (2021, January 18). Clarification on non-delegable duty of care in clinical cases. Retrieved from https://blmhealthandcareblog.com/2021/01/18/clarification-on-non-delegable-duty-of-care-in-clinical-cases/ 41 15 the first suggestion to fill the gap in law in Malaysia would be by amending the law. The amendment should provide more protection for medical practitioners or impose more liabilities to the governing body that governs medical practitioners, in the event of negligence by their members. For example, a specific statutory law should be made for cases in regards with negligence by the Government Hospitals. This is due to the fact that they are currently regulated by mere sets of regulations instead of a specific, binding statutory law. The second suggestion would be for the Malaysia’s Ministry of Health (MOH) to collaborate with the Malaysian Medical Council (MMC) to provide better protection for medical practitioners, in the form of setting up extra insurance funds to cover for medical practitioners in the event of negligence in their parts. The insurance coverage should be limited to the registered members of MMC only and serve as both a safety net and a warning to the medical practitioners as there should be a limited number of times for them to exercise these rights before getting harsher punishments. Another method that can be used to protect the medical practitioners with regards to insurance is by making it compulsory for them to set up insurance coverage as part of the requirement for them to renew their operating licence. This will ensure that in the event of successful claims against their negligence, they would be able to pay up the claimant, and the claimant would not be under compensated which will protect the rights of both parties. 7. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY This research adopts a qualitative method by conducting library-based research. The first part of this research would be doctrinal research, which draws upon primary and secondary sources. Primary sources include the English Common Law, Civil Law Act 1956, Medical Act 1971, Limitation Act 1953 and Medical Regulation 1974, Private Healthcare Facilities & Services Act 1998, Private Healthcare Facilities and Services (Private Hospitals and Other Private Healthcare Facilities) Regulations 2006 and others related to the medical will be analysed and taken into consideration. Secondary sources include the Law and Ethics Related to Medical Profession, the journal and reading materials and books obtained from online databases such as Lexis.com, LexisNexis Academic, Westlaw International, CLJ Legal, Lawnet, Google Scholar, Springer Link, Sage Publications and ProQuest. Qualitative research studies gather qualitative data such as words and images which are often 16 through interviews and observations. Because human behaviours, including teaching and learning, are complex, they should be studied in-depth over an extended period of time. Qualitative research develops explanations and theories based on what they have observed. The product of qualitative research is a narrative report, rich in detail was one of our main considerations in proceeding with a qualitative study. In this research we are focusing on case study and grounded theory that are summarised from the arm-chair research or library-based research. Case study is a detailed account of one or more cases. An intrinsic case study focuses on in-depth understanding of medical negligence and between vicarious liability relationships. A collective case study examines several cases, allowing us to effectively generalise the results. Beside that we plan to gather data through multiple methods, including observation in the field, interviews, focus groups, questionnaires, and document reviews. The case study research report provides a vivid, detailed description of the case and its context, as well as implications from the case. Grounded theory is generated inductively from the data to describe and explain a phenomenon. Data will be gathered primarily through open-ended recorded interviews through virtual meetings such as Zoom or Google Meet with 2 Medical Practitioners and 2 Medical Facilities Management Team from 3 government hospitals and 2 private hospitals, to get their opinion on proportions of liabilities between hospitals and medical practitioners. To better comprehend the nature of problems in medical negligence, interviews will be conducted with the officers from the Department of Legal of the Ministry of Health and a set of questionnaires will be gathered and analysed. We will construct a grounded theory by identifying concepts, themes, and patterns in the data that show how the phenomenon operates in real life. The grounded theory research report describes the topic, the people studied, the methods of data collection, and the principles that emerged from the data. The purpose is to get information on the medical negligence liabilities awareness among Malaysians. The data for this research can be collected by qualitative and quantitative data such as:I. II. Through Electronically such as Medline, PubMed, and Google Scholar; Through manually such as from various papers, journals, researches and books such as Medical Malpractice, Medical Negligence Liabilities, law review articles and healthcare analysis articles; and III. Surveys and interviews with relevant people to seek the advice of experts and counsels. 17 Mixed methods can be used to gain a better understanding of connections or contradictions between qualitative and quantitative data; which we believe able to provide opportunities for participants to have a strong voice and share their experiences across the research process, and they can facilitate different avenues of exploration that enrich the evidence and enable questions to be answered more deeply. Since the mixed method is used, NVivo is one of Computer-assisted (or aided) qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) used to run and analyse the data collected in this research. With the compatibility of NVivo in information-gathering platforms, including Atlas.ti, MaxQDA and Framework, EndNote, Mendeley, RefWorks, Zotero, Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Word, Microsoft Access and IBM SPSS Statistics including Evernote, Survey Monkey, Qualtrics, OneNote and TranscribeMe will be able to assist in analysing the data in this research. 8. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY This research contributes to the body of knowledge and literature on the legal aspect of liabilities between Hospital and Medical Practitioners in medical negligence cases of Malaysia. Being the pioneer and only work on the subject, this study is sure of major significance to both the industry and academia. It will first further protect the rights of doctors and other medical officers that are registered with the Malaysian Medical Council. The findings will then make clear on the improvement, plus to enhance our legal system on tort action particularly in vicarious liabilities between hospital or medical facilities and professionals especially medical practitioners, and to ascertain the usage of the principle in medical negligence in Malaysia. Apart from enhancing the literature on the reformation of the current legal framework, it is hoped that the findings of this research could assist the Judiciary Federal, State and local authorities, research institutions, governing medical negligence bodies and people at large in understanding, applying and improving the current legal framework which is suitable in Malaysia. Besides that, it will assist Judiciary Federal, State and local authorities to develop clear distinction on proportions of liabilities between parties by making hospitals bear the same responsibilities and liabilities toward medical negligence in Malaysia. 18 9. CONCLUSION In conclusion, the issue of the proportion of liability between doctors and hospitals were highlighted in this study. We are not looking to make the doctors and medical practitioners to be wholly liable for negligence cases, nor do we want the medical practitioners to fully escape liabilities from their negligence. The intention of the study is to create a form of justness for the medical practitioners in the event of them being liable for negligence. In relation to this, we compare and contrast the situation and laws of Malaysia and the UK, and try to reach an equilibrium point between the contemporary and the traditional views of the law towards medical negligence. Thus, the recommendations for Malaysian lawmakers and relevant bodies such as MOH and MMC to take a hybrid stance between the contemporary and traditional view on medical negligence may be the best outcome for all parties involved. RESEARCH MILESTONES/PROVISIONAL PLANS Year 2022 Months 3 4 5 6 7 Literature Review Data collection Data Management (Transcribing and Data Coding) Data Analysis and Findings Writing Research of Report and Project Completion 19 LIST OF REFERENCES/BIBLIOGRAPHY Legislations 1. Limitation Act 1953 2. Medical Regulation 2017 3. Medical Act 1971 4. Private Healthcare Facilities & Services Act 1998 5. Private Healthcare Facilities and Services (Private Hospitals and Other Private Healthcare Facilities) Regulations 2006 6. Civil Law Act 1956 Case Reports Dr Chin Yoon Hiap v Ng Eu Khoon & Ors and other appeals [1998] 1 MLJ 57 Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd v Shatwell [1965] AC 656 at 685 Canadian Pacific Railway v Lockhart [1942] 2 All ER 464 Staveley Iron & Chemical Co Ltd v Jones [1956] 1 All ER 403 Cassidy v Ministry of Health [1951]1 All ER 574 Roe v Ministry of for Health [1954] 2 QB 66 Tan Eng Siew v Dr Jagjit Singh [2006] 1 MLJ 57 Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 R v Bateman [1925] LJKB 791 Lanphier v Phipos [1838] 8 C & P 475 Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 2 All ER 118 at p 121 Kow Nan Seng v Nagamah [1982] 1 MLJ 128 Swamy v Matthews & Anor [1968] 1 MLJ 138 (FC) Shalini Kanagaratnam v Pusat Perubatan Universiti Malaya & Anor [2016] 6 CLJ 225 Burnie Port Authority v General Jones Pty Ltd (1994) 120 ALR 42 Datuk Bandar Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur v Ong Kok Peng & Anor [1993] 2 MLJ 234 Woodland v swimming Teachers Association and Others [2014] AC 537 20 The Management Corporation Strata Title Plan No 3322 v Tiong Aik Construction Pte Ltd [2016] SGCA 40 Hillyer v The Governors of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital [1909] 2 K.B. 820 Gold v Essex County Council [1942] 2 KB 293 Hopkins v Akramy, Badger Group and NHS Commissioning Board [2020] EWHC 3445 (QB) Journals & Articles 1. Medical Negligence: New Issues And Their Resolution [2000] 3 MLJ Clxxxiv 2. Siti Naaisha Hanbali, Solmaz Khodapanahandeh (2014), A Review of Medical Malpractice Issues in Malaysia under Tort Litigation System retrieved from Global Journal of Health Science; Vol. 6, No. 4; 2014, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e665/a4f5c126822e7f2313348a004e0f8863590d.pdf?_ga=2 .6940082.1261550269.1644512757-494349080.1644512757 3. The Medical Profession, Societal Demands and Developing Legal Standards [2014] 5 MLJ cxxxvii 4. U.S. Dept. of Health, Education & Welfare (HEW), Report of the Secretary's Commission on Medical Malpractice 18 (1973) 5. Bennett, S. (2020, December 21). Outsourcing of NHS services: the High Court in JMH v Akramy finds that no non-delegable duty is owed to patients. 1 Chancery Lane retrieved from https://1chancerylane.com/outsourcing-of-nhs-services-the-high-court-in-jmh-v-akramy-fin ds-that-no-non-delegable-duty-is-owed-to-patients/ 6. S.W., & V.A.P.B. (2021, January 18). Clarification on non-delegable duty of care in clinical cases. Retrieved from https://blmhealthandcareblog.com/2021/01/18/clarification-on-non-delegable-duty-of-care-i n-clinical-cases/ 21