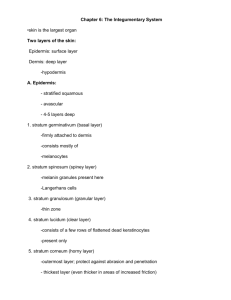

MINISTRY OF HEALTH OF UKRAINE VINNITSA NATIONAL PIROGOV MEMORIAL MEDICAL UNIVERSITY “ Approved ” on methodical meeting of the department of skin and venereal diseases record № 1 Heard of department ________prof. Bondar S.А. «_27_»__August_2021_ GUIDELINES for independent work of students in preparation to a practical lesson Academic discipline Theme of the lesson № 3 Dermatology and venereology Morphology of primary and secondary skin lesions. Course 4 Faculty Medical faculty Vinnytsia VINNITSA NATIONAL PIROGOV MEMORIAL MEDICAL UNIVERSITY Department of skin and venereal diseases Guideline of the practical lessons on dermatovenerology for self-study students of fourth year of medical faculty MODULE I THEMATIC MODULE 1 LESSON 3 Theme:MORPHOLOGY OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SKIN LESIONS. Amount of hours for lesson: 2 Guideline for self-study of students for practical lesson Module I . Dermatology and Venereology Thematic module 1. General Dermatology LESSON 3 Morphology of primary and secondary skin lesions. 1. Theme urgency To define properly the pathological skin process, which is manifested by morphological lesions composing the skin affection, the dermatologist must appraise the condition of the skin over the whole body of the patient, its color, turgor, moistness. luster, local temperature, etc. The objective findings are judged on the basis of visual impression and touch. The ability to distinguish the lesions of the skin rash makes it possible to define the pathological process correctly and approach the diagnosis of the dermatosis. In many cases the clinical picture 'drawn on the skin' by the erupted lesions and the character of their arrangement allow the diagnosis to be made and treatment begun; in certain cases additional methods of examination (including laboratory tests) have to be resorted to in making the diagnosis. A dermatological diagnosis is based both on the distribution of lesions and on their morphology and configuration. For example, an area of seborrhoeic dermatitis may look very like an area of atopic dermatitis; but the key to diagnosis lies in the location. Seborrhoeic dermatitis affects the scalp, forehead, eyebrows, nasolabial folds and central chest; atopic dermatitis typically affects the antecubital and popliteal fossae. See if the skin disease is localized, universal or symmetrical. Depending on the disease suggested by the morphology, you may want to check special areas, like the feet in a patient with hand eczema, or the gluteal cleft in a patient who might have psoriasis. Examine as much of the skin as possible. Look in the mouth and remember to check the hair and the nails. Note negative as well as positive findings, e.g. the way the shielded areas are spared in have a characteristic morphology, but scratching, ulceration and other events can change this. The rule is to find an early or primary lesion and to inspect it closely. What is its shape? What is its size? What is its colour? What are its margins like? What are the surface characteristics? What does it feel like? There are many reasons why you should describe skin diseases properly. Skin disorders are often grouped by their morphology. Once the morphology is clear, a differential diagnosis comes easily to mind. If you have to describe a condition accurately, you will have to look at it carefully. You can paint a verbal picture if you have to refer the patient for another opinion. You will sound like a physician. You will be able to understand the terminology of the dermatology. 2. Concrete Objectives: Students must know: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Classification of morphological lesions. Description and character of each of the morphological lesions. The histological picture of each of the morphological lesions. How may terminate each of the morphological lesions. Monomorphic and polymorphic lesions. Students should be able to: 1. Distinguish an inflammatory and non-inflammatory primary morphological lesions. 2. Distinguish an infiltrative and exudative primary morphological lesions. 3. Define secondary morphological lesions.. 4. Distinguish monomorphic and polymorphic lesions. 3. Tasks for self-study during preparation for lesson. 3.1. Theoretical questions for the lesson: 1. Primary morphological lesions. 2. Inflammatory and non-inflammatory primary morphological lesions (how to differentiate them). 3. Infiltrative primary morphological lesions (a macula, papule, tubercle, and a nodule). 4. Exudative primary morphological lesions (a vesicle, bulla, pustule, and wheal). 5. Secondary morphological lesions. 6. A stable and non-stable secondary morphological lesion. 7. Monomorphic and polymorphic lesions. 8. True- and false polymorphism. The subject-matter: Eruptions on the skin may be inflammatory or non-inflammatory. Most, rashes in skin diseases are of an inflammatory character. Pigmented spots, tumours, atrophy, hyperkeratosis, etc. are the non-inflammatory manifestations. All lesions of skin eruptions are subdivided into primary and secondary. Primary morphological lesions appear on a seemingly healthy skin as the first, direct reaction to an exogenous or endogenous stimulus. Secondary morphological lesions form as the result of spontaneous evolution of the primary lesions or as a consequence of applied treatment. The primary morphological lesions are subdivided into infiltrative and exudative. PRIMARY MORPHOLOGICAL LESIONS Infiltrative Primary Morphological Lesions A spot (macula) is a circumscribed alteration in the colour of the skin or mucous membrane. It is not raised above the surface of the skin and does not differ from it in consistency. An inflammatory maculae are clinically manifested by a circumscribed redness of the skin as the result of dilation of the vessels of the superficial vascular network. Depending on the degree of filling of the blood vessels the maculae differ in colour; they may be red, rose-coloured or bluish (cyanotic or congestive). An inflammatory macula disappears when it is pressed but reappears in the same form when the pressure is removed. Small inflammatory spots which may reach the size of the nail of the little finger form a rash called roseola. This rash occurs in secondary syphilis, measles, drug rash, etc. The spot may be of an acute inflammatory character, with a bright rose colour. There are also non-acute inflammatory spots which are pale-rose with a brownish tinge. Rose-coloured spots of an acute inflammatory character appear as a primary lesion in patients with children's infections, in eczema, dermatitis, pityriasis rosea; those of a non-acute inflammatory character form in patients with secondary (rarely tertian) syphilis, erythrasma, pityriasis versicolor. Large vascular, spots (the size of a child's palm and larger) are called erythema. They may have a bright red colour. They are attended with an itch and are consequent, as a rule, upon acute inflammatory dilatation of, vessels in patients with eczema, dermatitis, 1st degree burn, erysipelatous inflammation, and erythema exudativum multiforme. A non-inflammatory maculae caused by stable non-inflammatory dilatation of the superficial skin vessels (capillaries) are called telangiectasias. Telangiectasias are acquired spots which may occur independently or be a component of the clinical picture of acne rosacea, cicatrizing erythematosis, and some other diseases. Non-inflammatory vascular birthmarks (naevi) are congenital maculae. Effusion of blood into the skin may occur in increased permeability of the vascular walls, as a result of which hemorrhagic maculae form, which do not disappear when they are pressed. Depending on the period of time after the effusion, these maculae are red, bluish-red, purple, green or yellow (their colour changes with the gradual conversion of hemoglobin to hemosiderin and hematoidin). They are distinguished according to size: pinpoint hemorrhages are called petechiae, small round and usually multiple hemorrhages are known as purpura, large linear hemorrhages - vibex, effusion of blood over a large area with irregular contours is called ecchymosis; massive hemorrhage with swelling of the skin which is raised above the surface of the surrounding areas is known as a hematoma. Hemorrhagic maculae occur in allergic vasculitis of the skin and some infectious diseases (typhuses, rubella, scarlet fever, and others). Pigmentation spots form on areas with an increased or decreased content of the pigment melanin in the skin. They may be patches of hyperpigmentation or depigmentation. Pigmentation spots may be congenital (birthmarks, lentigo, albinism) or acquired (freckles, chloasma, Vitiligo). Spots of hyperpigmentation include freckles (small areas of light-brown or brown colour which form on exposure to ultraviolet irradiation of increased intensity), lentigo (foci of hyperpigmentation with hyperkeratosis), chloasma (large areas of hyperpigmentation forming in Addison's disease, hyperthyroidism, and other morbid conditions). Small patches of depigmentation are called leucoderma. Leucoderma occurs in patients with secondary recurrent syphilis when these spots of depigmentation form against a hyperpigmented background. Vitiligo is marked by areas of various size devoid of pigment, which is attributed to neuroendocrine disorders and enzymatic dysfunction. Congenital absence of pigment in the skin with insufficient coloration of the eyebrows, eyelashes, and hair on the scalp is called albinism. Effusion of dye into the skin may occur an artificial non-inflammatory maculae (tattoo). A papule is a solid, more or less hard lesion, elevated above the skin surface. It resolves leaving neither a scar nor cicatricial atrophy, though a non-persisting trace, pigmentation or depigmentation, may remain. Papules which mainly occur in the epidermis are called epidermal (e.g. a flat wart), those found in the dermis are called dermal (e.g. in secondary syphilis). Papules most commonly have epidermo-dermal localization (e. g. in lichen planus, psoriasis, neurodermitis). Inflammatory and non-inflammatory papules are distinguished. The former are much more frequent occurrences (in psoriasis, eczema, secondary syphilis, lichen planus, lichen rubra acuminatus, neurodermitis, and other diseases). They are marked by inflammatory infiltration in the papillary layer of the dermis, dilatation of vessels, and a circumscribed swelling. When pressed, the papule turns pale but does not lose its colour completely. In non-inflammatory papules there is proliferation of the epidermis (a wart), or deposit, of аbnormal metabolites in the dermis (xanthoma), or proliferation of dermal tissue (papilloma). Papules vary in size. Papules of the size of a millet seed or the head of a pin are called miliary (those in lichen planus or lichen scrofulosorum), of the size of a lentil or pea, lenticular (in psoriasis, secondary syphilis, etc.), those of the size оf coin аге called nummular. Confluent papules form plaques (to the size of a child's palm). Papules are usually strictly circumscribed but they vary in outline (they may be spherical, oval, flat, polygonal, pointed, navel-like, domeshaped) and their surface is smooth or rough. The consistency of papules may also vary (they may be soft, dough-like, firm-elastic, firm, hard) just as their colour (the colour of normal skin, yellow, pink, red, purple, livid, brown, etc. ). The surface of papules growing on adjacent skin surfaces may undergo erosion as a result of friction, the surface of those growing on mucous membranes may also erode because of the irritating effect of saliva, secretions, food, etc. (these are erosive papules), while the papules themselves grow larger, undergo hypertrophy. In papules, the histological picture in the epidermis is marked by hyperkeratosis, granulosis, acanthosis, parakeratosis; deposits of various infiltrates are found in the papillary layer of the dermis. A tubercle is an infiltrative solid skin elevation of a non-acute inflammatory character. It often ulcerates and terminates by cicatrization or cicatricial atrophy. It is difficult to distinguish it from a nodule in its morphological appearance, especially in the initial developmental stage. A tubercle and papule may be similar in size, shape, surface, colour, and consistency. The inflammatory cellular infiltration in tubercles spreads not only in the papillary but mainly in the reticular layers of the dermis and histologically is an infectious granuloma which either ulcerates with the eventual formation of a scar, or resorbs leaving cicatricial atrophy. This is the main clinical distinction between a tubercle and a papule, which makes it possible to determine retrospectively many years after the process had terminated whether the patient had had, for instance, lesions of tertian syphilis or those of lupus vulgaris (nor only the presence of scars or atrophy is taken into account, but the character of their arrangement, e.g. the mosaic pattern of the scar in syphilis, the presence of bridges in lupus vulgaris, and other symptoms). In some cases the tubercles have a rather characteristic colour: reddish-brown in tertian syphilis, reddish-yellow in lupus vulgaris, rusty-brown in leprosy. In different diseases the tubercles have distinguishing features in their histological structure. A tubercle in tuberculosis of the skin, for instance, consists mainly of epithelial cells and various numbers of Langhans' giant cells; the tubercle in syphilis consists of plasma cells, lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and fibroblasts. Tubercles occur on restricted areas of the skin as a rule, either in groups or they coalesce forming a compact infiltration, much less frequently they are scattered, disseminated. A nodule is a primary infiltrative morphological lesion without acute inflammation. It is large (the size of a pea to that of a walnut of larger) and is situated in the subcutaneous fat. The nodule may at first be not raised above the skin surface (in which case it is detected by palpation), but with growth it gradually becomes elevated (often considerably). The nodules ulcerate and eventually cicatrize. Their consistency varies from soft (in tuberculosis colliquativa) to firmelastic (in leprosy and tertian syphilis). The specific features of the nodules in some diseases (appearance, colour, shape, surface, consistency, the character of secretions) permit designating them specially: scrofuloderma in tuberculosis colliquativa, gumma in tertian syphilis, leproma in leprosy. Benign and malignant new growths may occur in the form of nodules. Exudative Primary Morphological Lesions A vesicle is a primary morphological lesion of an exudative character; it has a fluidcontaining cavity and is slightly elevated. A cavity with serous, less frequently serosanguineous contents, a covering, and floor are distinguished in a vesicle. The vesicles may be situated under the horny layer, in the middle of the epidermis, and between the epidermis and dermis. The size of a vesicle ranges from that of a pin head to the size of a lentil. The contents of the vesicle may be clear, serous, less frequently sanguineous, and often turn cloudy and purulent, which occurs when the vesicle transforms into a pustule. The fluid discharged from the vesicle dries to form a crust or the covering of the vesicle ruptures, an erosion forms and weeping occurs. Such is the case in eczema in the stage of exacerbation. The vesicles may occur on normal skin but usually they have an inflammatory erythematous base. On the oral mucosa and rubbing skin surfaces the vesicles rupture rapidly, leaving erosive surfaces; in places with a thicker skin (e.g. on the palms in dyshidrosis) they remain longer. A vesicle either disappears without a trace or leaves a temporary pigmentation as is the case, for instance, in Duhring's herpetiform dermatitis. In vesicle formation the histological picture is marked by spongiosis (eczema, dermatitis), ballooning degeneration (lichen planus pemphigoides, herpes zoster, chickenpox), and intracellular vacuolation (dyshidrotic eczema, epidermophytosis). A bulla is an exudative cavitary lesion the size of a hazel nut to that of a hen's egg and larger. Like the vesicle, it consists of a covering, a cavity with serous contents, and a floor. A bulla under the horny layer is called subcorneal, one in the thickness of the prickle-cell layer intraepidermal, and bulla found between the epidermis and dermis is called subepidermal. The bullae are spherical, semispherical or oval, and their contents are clear, yellowish, less frequently cloudy or sanguineous. Various amounts of leucocytes, eosinophils, and epithelial cells are found in the fluid. Cytological examination of impression smears or scrapings from the floor of the bulla is sometimes of practical importance in the diagnosis of dermatoses because the cell composition in some of them has specific features. Bullae occurring on rubbing skin surfaces and on the mucous membranes rupture rapidly and leave erosions with a border of scraps of the covering of the bullae. Bullae occur in pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus congenitalis, acute epidermatic pemphigus neonatorum, erythema multiforme exudativum, burns, drug dermatitis (e.g. in sulphanilamide erythema), and some other skin diseases. A bulla usually forms against the background of an erythematous macula, though it may also be found on apparently healthy skin (in patients with pemphigus vulgaris). Various endogenous factors often promote the development of intraepidermal bullae; breakage of the intercellular connections (acantholysis) and degenerative changes in the epidermal cells are encountered in such cases. In disturbed structure of the basement membrane, the transudate or exudate from the vessels loosens epidermis (epidermolysis) and subepidermal bullae form, e. g. in erythema multiforme exudativum. Pemphigus is characterized by intraepidermal localization of the bullae (in the prickle-cell layer) and the presence of acantholytic cells which are found either as occasional cells or in clusters. A pustule is an exudative cavitary lesion containing pus. There is a considerable number of leucocytes in the purulent exudate which is also rich in albumins and globulins. Under the effect of the products of vital activity of microbes (mainly staphylococci and streptococci) the epithelial cells undergo necrosis as a result of which the cavity of the pustule forms in the epidermis. Pustules located in the thickness of the epidermis and marked by a tendency to form a crust are known as impetigo. After the crusts drop off a temporary pigmentation of the affected area remains. A condition in which pustules form around the hair follicles is called folliculitis. When pus penetrates the orifice of the hair infundibulum, the centre of the pustule pierces the hair and ostial folliculitis develops. Folliculitis may be superficial, in which case the lesions do not leave any traces, or deep (the part of the follicle lying deep in the dermis is involved in the process) with the formation of a scar. Staphylococcus is the most common causative agent of folliculitis. Eruption of deep non-follicular pustules which form in the dermis is called ecthyma. After it resolves an ulcer forms which heals leaving a scar. Ecthyma is caused by streptococcus. Superficial streptococcal pustule (flaccid, flat is called phlyctena. Pustules are always surrounded by a rose-coloured nimbus of inflamed tissue. They are sometimes secondary in character, developing from vesicles and bullae in concomitant pyococcic infection. A wheal is an exudative non-cavitary lesion which forms as a result of circumscribed acute-inflammatory oedema of the papillary skin layer. It is a rather hard cushion-like elevation, spherical, or less frequently oval in shape, which is attended with strong itching. A wheal is an ephemeral lesion, i.e. it usually disappears rapidly (from several scores of minutes to a few hours) leaving no trace. It may be the size of a pea to that of a palm and larger. It is pale-pink because dilatation of the vessels occurs simultaneously with the oedema of the papillae. In drastic oedema the vessels are compressed and the wheals take a porcelain-like colour. Wheals may form at the sites of mosquito, midge, or other insect bites, after exposure to cold, on contact with stinging nettle (external factors), in severe emotions, toxicosis and sensitization of the organism (internal factors). Wheals appear on the skin in drug, food and bacterial allergy (urticaria, angioneurotic oedema, serum sickness) and may be induced by mechanical irritation of affected skin areas, for instance in urticaria pigmentosa. Large persisting wheals form in such cases after mechanical irritation of the skin (urticaria factitia, or dermatographia). Though the development of wheals is attended with severe itching, no scratches are usually found on the patient's skin. SECONDARY MORPHOLOGICAL LESIONS Secondary morphological lesions develop in the process of evolution of primary morphological lesions. They include pigmentation maculae, scales, crusts, superficial and deep fissures, excoriations, ulcers, scars, lichenification, and vegetations. Pigmentation. Here we shall deal with hyperpigmentation consequent upon increased deposit of the pigment melanin after the resolution of primary (papules, tubercles, vesicles, bullae, pustules) and secondary (erosions, ulcers) skin lesions and deposit of the blood pigment hemosiderin in hemosiderosis of the skin. Secondary hypopigmentation is associated with a diminished content of melanin in separate skin areas and is known as secondary leucoderma. Secondary pigmentation maculae take the shape and contours of the lesions which they replace. Scales (squamae) are detached horny laminae. Unnoticeable physiological shedding of the laminae of the horny layer occurs continuously under normal conditions. These laminae are removed by washing and rubbing of the clothes against the skin. In some pathological conditions the formed scales are seen with the naked eye. They characterize the process of abnormal desquamation. Small and fine scales resembling flour or bran are called branny and the shedding of such scales is termed furfuraceous desquamation; it is encountered, for instance, in pityriasis versicolor. Larger scales are termed lamellae and their shedding is called lamellar desquamation; it is encountered in psoriasis. In some skin diseases, e.g. erythroderma and scarlatiniform dermatitis, the horny layer is shed in large plates. Scales are among the constant objective symptoms of some dermatoses, for instance ichthyosis. The colour of the scales may be white, grey, yellowish or brownish. Abnormal scaling usually occurs as a consequence of parakeratosis (disturbed cornification), when there is no granular layer in the epidermis and remnants of nuclei are found in the horny laminae. Desquamation is less frequently the result of hyperkeratosis, i.e. abnormally intensive development of the ordinary horny cells, or keratosis (the layering of hard, dry horny masses as, for example, in corns). Knowledge of the form of desquamation and the type of scales helps in making the diagnosis of some dermatoses. Crusts (crustae) form when a serous exudate, pus or blood, sometimes with an admixture of the drugs applied, dries on the skin. Therefore serous, purulent, seropurulent, sanguinopurulent, and other kinds of crusts are distinguished. They result from the drying of vesicles, bullae and pustules, the ulceration of tubercles, and nodules, in necrosis and purulent melting of deep pustules. Laminated massive oyster-like crusts are called rupia; the upper part of the crust in such case is oldest but, at the same time, the smallest. The colour of the crusts is determined by the character of the secretions from which they formed; they are transparent or yellowish in a serous secretion, yellow or greenish-yellow in a purulent secretion, red or brownish in a sanguineous secretion, etc. When the secretions are of a mixed character, the colour of the crusts changes accordingly and takes various tinges. Crusts often form on the lips (in pemphigus, erythema exudativum multiforme, lichen planus pemphigoides, in various types of cheilitis, etc.). Crusts appear on the skin in scabies, mycoses, pyoderma, eczema, neurodermitis, in various syphilids, and in other diseases. A superficial fissure (fissura) does not penetrate beyond the epidermis and heals without a trace. A deep fissure (rhagas) forms in the epidermis and the dermis, sometimes with involvement of the deeper tissues, and leaves a scar after healing. Linear fissures (defects in the skin) appear when the skin loses its elasticity due to inflammatory infiltration on skin areas that are subject to stretching (e.g. at angles of the mouth, in the folds between the fingers or toes, on the skin overlying the joints, in the region of the anus, etc.). They also form in chronic eczema, intertriginous epidermophytosis of the feet, pyodermal or fungal lesions at angles of the mouth (perleche), intertrigo, etc. and also from stretching of skin with a dry horny layer. Deep fissures may be encountered in early congenital syphilis. They form around the natural orifices and bleed easily. Depending on the depth of the fissures, serous or serosanguineous secretions appear which dry and form crusts corresponding to the fissures in shape. An excoriation is a skin defect resulting from scratches or some other traumatic damage. Scratching may injure not only the epidermis but also the papillary layer of the dermis; no scars form in such cases. A deeper penetrating excoriation leaves a scar, pigmentation or depigmentation. Excoriations are objective signs of excruciating itching. The localization and shape of the excoriations some -times help in making the diagnosis (e.g. in scabies). Erosion is a superficial skin defect within the epidermis. Erosions appear after rupture of vesicles, bullae and pustules and are of the same shape and size as the primary morphological cavitary lesions in whose place they had formed. They are usually pink or red and have a moist, weeping surface. Large eroded skin and mucosal surfaces are observed in pemphigus. Small erosions form in rupture of vesicles in patients with eczema, lichen pemphigoides, herpes zoster, dyshidrosis, and dyshidrotic epidermophytosis of the feet. Erosive syphilitic papules are often found in the mouth and on the rubbing skin surfaces; hard chancre may also form as an erosion. Erosions heal without leaving scars. An ulcer (ulcus) is a skin defect with involvement of the epidermis, dermis, and sometimes the deeper lying tissues. Ulcers develop from tubercles, nodules, and after rupture of deep pustules. Trophic ulcers alone form as the result of primary necrosis of seemingly healthy tissue because of its disturbed trophies. Ulcers may be spherical, oval or of an irregular shape. The surface of ulcers varies in colour from bright-red to cyanotic congestive. The floor may be even or uneven and covered with a serous, purulent, or sanguineous secretions, and with scanty or rich granulations. The edges may be regular, undermined and eroded, flat or raised, hard or soft. In a purulent inflammatory process the edges of the ulcer are oedematous and soft, and there are abundant purulent discharge and diffuse hyperemia around the ulcer. In disintegration of infectious granulomas (e.g. a gumma in syphilis), hard circumscribed infiltration forms around the ulcer with congestive hyperemia on the periphery. A hard infiltration around the ulcer with no inflammatory phenomena suggests a new growth. An ulcer heals always leaving a scar from the character of which the previous pathological process may be judged. A scar (cicatrix) is a stable secondary morphological lesion. It forms in place of deep defects in the skin which had been replaced by coarse, fibrous connective tissue (collagen fibres). The skin papillae are smoothed out in such cases and the interpapillary epithelial processes disappear, with the result that the boundary between the epidermis and dermis is seen as a straight horizontal line. The scar has neither the skin pattern nor the openings of the follicles or sweat ducts. Cicatricial tissue also contains no hair, sebaceous or sweat glands, vessels or elastic fibres. A scar forms at the site of deep burns, cuts, ulcerated tubercles, nodules or deep pustules or it may form in the 'dry manner' without preceding ulceration, e.g. in papulonecrotic tuberculosis of the skin or in some cases of tertiary tubercular syphilis. Fresh scars are red or pink, older scars are hyperpigmented or depigmented. Scars may be smooth or rough. Hypertrophic scars raised above the skin surface form as the result of excessive amount of hard fibrous tissue; they are called keloidal scars. Atrophy (a stable secondary morphological lesion) is a condition in which finer connective tissue forms and in a lesser amount than in a scar. In such cases the skin in the affected area is very thin, devoid of the normal pattern for the most part, and is often depressed, i.e. is below the level of the surrounding skin. Atrophy develops without preceding ulceration of the lesion as a rule, i.e. in the 'dry manner', (e.g. in erythematosis and scleroderma). When pressed between the fingers such a skin gathers in fine folds like cigarette paper. The localization, shape, number, size and colour of the scars often help in making the diagnosis of a pathological process suffered earlier by a person. A syphilitic gumma, for instance, leaves a deep retracted stellate scar; colliquative tuberculosis of the skin leaves retracted uneven, irregular in shape bridge-like scars in the region of the lymph nodes. Similar scars on other skin areas may be caused not only by tuberculosis but by chronic deep pyoderma. Papulonecrotic tuberculosis of the skin leaves clearly demarcated, as if stamped, superficial scars, whereas tubercular syphilid of the tertiary syphilis leaves motley tessellated scars with scalloped contours; smooth lustre atrophy of the skin develops in place of the lesions in lupus vulgaris. Lichenization, or lichenification is thickening and hardening of the skin marked by exaggeration of its normal pattern, hyperpigmentation, dryness, roughness, and shagrin-like appearance. In lichenification the prickle-cell layer of the epidermis is hypertrophied and the interpapillary epithelial processes are considerably enlarged and penetrate deep into the dermis (acanthosis) and the upper parts of the dermis are involved in chronic inflammatory infiltration and the papillae are elongated. In skin and venereal diseases the eruption may be monomorphic, consisting of a single type of primary morphological lesions (e.g. papules in psoriasis and syphilis, roseolas in syphilis, warts, etc.). In view of this, monomorphic dermatoses are distinguished, among which are psoriasis, lichen planus, urticaria, pemphigus vulgaris, furunculosis, hidradenitis, pemphigus epidermicus neonatorum, etc. If there are several types of primary morphological lesions, the condition is called true polymorphism. The group of dermatoses in which true polymorphism is encountered includes eczema, leprosy, Duhring's dermatitis herpetiformis, polymorphic exudative erythema, secondary period of syphilis, etc. These are cases of polymorphic diseases. For instance, rapidly rupturing bullae form in patients suffering from epidermolysis bullosa. Erosed surfaces with an exudate drying to crusts are exposed in such cases; pigmentation spots remain when the crusts drop off. It seems as if there is a diversity of clinical signs. This is what gives the idea of the polymorphism of the eruption, that is why it is called false polymorphism. Correct recognition of a monomorphic or polymorphic eruption or false polymorphism makes the diagnosis easier. Materials for self-checking: А. Tasks for self-checking: Tests for verification of initial level of knowledges 1. Which of the following signs are characteristic to description of macula? 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Change of relief of skin. Change of consistency of skin. Change of color of skin. Congenial absence of pigment in a skin. Acquired absence of pigment in a skin. 2. Which histomorphological changes takes place in formation of vesicles? 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Ballooning degeneration; Spongiosis; Parakeratosis; Acanthosis; Granulosis. 3. Which of the followings primary lesions terminates atrophy of skin? 1) 2) 3) 4) Papule; Tubercle; Vesicle; Nodule; 5) Macula. 4. Which of these statements are incorrect? 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) A tubercle locates in the reticular layer of the dermis; A tubercle locates in the Malpighian layer; A tubercle terminates by cicatrization; A tubercle histologically is an specific granuloma; A tubercle is a stable secondary morphological lesion. 5. Which spots become anemic after vitropression? 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Telangiectasias; Purpura; Inflammatory spots; Hemorrhagic spots; Erythema. Literature. The basic: 1. Lecture on the theme. 2. Guideline for self-study of students by preparation for practical lesson 3. 3. Dermatology, Venereology. Textbook / [Stepanenko V.I, Shupenko M.M., Mikheiev O.G. et al.];under edit. of V.I.Stepаnenko. – Kyiv: KIM, 2013.– p. 27-42. 4. V.H. Koliadenko, T.P. Vysochanska, O.I. Denysenko. Dermatovenereology Modules, Kyiv AUS Medicine Publishing, 2010, p.10-18. 5. Yu. K.Skripkin and M.V. Milich. Skin and Venereal Diseases, English translation, Mir Publishers, 1981, p.62-75. The additional: 1. Family Medicine: textbook: in 3 books. – Book 3: . Multidisciplinary General Medical Practice Special part / L.S. Babinets, P.A. Bezditko, S.A. Bondar and et al. – Кyiv: AUS Medicine Publishing, 2020. – 616 p. (in English) 2. Fitzpatrick et al. Dermatology in General Medicine, 4th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1993. 3. Fitzpatrick. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 3rd Edition, 1997. 4. J.A.A. Hunter, J.A. Savin and M.V. Dahl. Clinical Dermatology, 3rd Edition, 2002, p. 30-33. 5. P.N Behl, A. Aggarwal, Govind Srivastava. Practice of Dermatology, 9th Edition, 2002, p.3339.