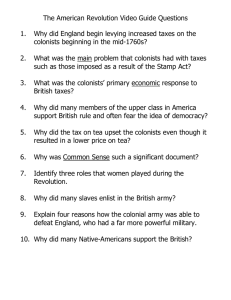

A republic is governed by its people. Considered by philosophers since the inception of political theory, such a system requires a particularly robust balance between personal freedom and social responsibility to be sustainable. This balance, and the experimentation necessary for it to pivot healthily, was already a demonstrably central component to British Colonial thinking in the New World during the Colonial Era. The British heritage of influential colonists as well as their unique situation demanded that the ideals of Popular Sovereignty, and necessarily Individual Rights, be concurrently upheld – and defended, in some cases, with violence. Our way of life today still treasures these principles, and that same balance continues to rock. The British have a history of valuing popular sovereignty: From before the Norman invasion, witanagemot assemblies would make major decisions together, even in questions of succession; In the 13th century, English barons officially wrested absolute power from the king via the Magna Carta; soon thereafter a dynamic Parliament was formed, which is itself subdivided further, and has continued to evolve. The democratization of power, therefore, has been integral to the British way of life throughout the centuries. The colonists were no exception in wanting to actively participate in the governing of their own lives. 1 Consent was a sacred idea to colonists. From the Mayflower Compact all the way to the Declaration of Independence, the signing of one's name carried meaning. Those attempting to enact change made their mark or voiced their support knew they would be held accountable for their stance, for better or for worse. More importantly, it directly involved an actor in whatever resolution was being carried out. This is the foundation of colonial thought. Some of the earliest settlers of North America, the Puritans on the Mayflower, made an agreement to govern themselves, to “covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick” 2 toward their own ends. They signed it together, paying homage to both their deity and their 1 2 Dr. Silva, Lecture, 09/06/18 Mayflower Compact king, acknowledging their inferior place while determining to make their own rules for the colony. Examples of these home-brewed laws being enforced abound. Anne Hutchison of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was tried for blasphemy by her own community, where she was found guilty and banished. 3 In the relatively contemporary Maryland Toleration Act, penalties vary in severity and cause, as well as number of offense. One could be fined, whipped or executed, as the law describes, for either a practical offense or a spiritual one. 4 The document ends with the telling phrase “The freemen have assented,” 5 rather explicitly stating who approves of the Act. There is similar directness in another colony, where John Locke writes “...we, the lords and proprietors of [Carolina], have agreed to this following form of government...” 6. There is agreement to a certain form of government involving a plurality, some of which he describes in point 92: “All towns incorporate shall be governed by a mayor, twelve aldermen, and twenty-four of the common council.” 7 There is a trend toward the spreading of power, in all these cases, where more of those colonists affected by a law tend to be involved in its execution. This pursuit of the people's rule extends beyond legislation itself; it also refers to not-so-lawful action. During a particularly tumultuous time in Virginia, Nathaniel Bacon, whether sincere or not, attempted to characterize his coup as a legitimate grassroots response by referring to himself as a “Generall by Consent of the people.” 8 His concern for this language and for the justification of his moves is evidence that popular opinion was paramount – that the people could (and should) feel entitled to up-end established law, and with force. This yearning for engagement reached a crescendo after the French and Indian War, when the British augmented their revenue-generating impositions on the colonies. Breaking from the practice of 3 4 5 6 7 8 Anne Hutchinson Trial, page 3 Maryland Toleration Act, page 2 ibid Locke, Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, page 1 ibid Bacon, Declaration of Rebellion in Virginia, page 2 effective salutary neglect which had allowed for the continued mutually beneficial relationship between colonies and mainland, British Parliament set new limitations that incensed colonists. These acts were interpreted by colonists to be naked direct taxation for which they were not deriving benefits. The circulation of propaganda railing about “taxation without their consent” 9 shows the near-unanimity of colonist ire. In particular, the Stamp Act was considered egregious and unlawful (even by level-headed Benjamin Franklin: “...it has appeared to be the opinion of everyone that we could not be taxed in a Parliament where we were not represented” 10) on that very principle of being excluded. Some colonists allowed themselves to openly perpetrate violence and cause property damage in protest 11 while others petitioned King George III. 12 To be dismissed from one's own governance was the deepest offense, the persistent bellow that spurred the colonies to finally begin organizing resistance together. The Intolerable Acts that followed only solidified colonists' resolve to oppose rule without consent. 13 This supreme desire to be consulted was dependent on the idea that the individual matters. Settlements such as Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, and Pennsylvania were founded on principles of religious freedom. William Penn, founder of the last, himself declares “That no Person or Persons, inhabiting in this Province or Territories...shall be in any Case molested or prejudiced...because of his or their conscientious Persuasion or Practice, nor be compelled to frequent or maintain any religious Worship...contrary to their religious Persuasion.” 14 This laxity was especially important in a world reeling from religious warfare; the New World, initially devoid of institutions and persecution, was a peerless place for worshiping the deity of one's choice. Enumerated individual rights, including the one above [save for one very intentional exception 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dulany, American Colonists Respond to Stamp Act, page 3 Franklin, American Colonists Respond to Stamp Act, page 5 Oliver, American Colonists Respond to Stamp Act, page 10 The First Continental Congress, Petition to King George III First Continental Congress, Articles of Association, page 1 Penn, Charter of Privileges, page 1 against papists], can be attested to in the English Bill of Rights. Every time that influential document removes a power from the monarchy, it grants protection to the individual. Notably far-reaching rights are that to petition the king without retribution and the freedom of speech. 15 This encourages issues to be addressed rather than swept under the proverbial rug. These legal securities could be drawn out to shield against the tyranny of any government authority. As Alexander Hamilton counters when faced with the assertion that condemning the conduct of administrators will bring about the collapse of government, “How often it has happened that the Abuse of Power has been the primary Cause of these Evils, and that it was the Injustice and Oppression of these great Men, which has commonly brought them into Contempt with the People?” 16 Men are better able to defend against suffering wanton injustices from those in power, be they laymen or clergy. The Enlightenment played a major role in shifting the focus from the spiritual to more earthly concerns, as “[Enlightenment participants] tried to determine a system of universal laws that governed nature and the development of human societies.” 17 This approach required the use of science, of free and open inquiry allowed for by the protections above. It made room for the skepticism of old ways and the gall to design new ones. Enlightened thinkers strove to temper the endemic core principles of Popular Sovereignty and Individual Rights in a precarious bid against mistreatment to (eventually) form a republic that still stands for those very same principles. 15 The English Bill of Rights, page 2 NY Libel Trial of John Peter Zenger, page 1 17 Schaller et al, American Horizons, page 163 16