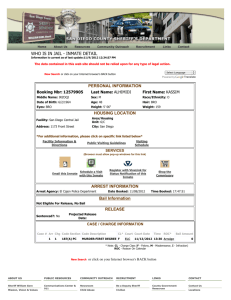

Management Audit of the County of Santa Clara Department of Correction Prepared for the Board of Supervisors of the County of Santa Clara September 22, 2020 Prepared by the Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division County Administration Building, East Wing, 10th Floor 70 West Hedding Street San Jose, CA 95110 (408) 299-6435 THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Board of Supervisors County Government Center, East Wing 70 West Hedding Street San Jose, California 95110-1770 (408) 299-6435 TDD 993-8272 Contract Auditor: Harvey M. Rose Associates, LLC E-mail: cheryl.solov@bos.sccgov.org September 22, 2020 Supervisor Dave Cortese, Chair Supervisor Cindy Chavez, Vice Chair Board of Supervisors’ Finance and Government Operations Committee 70 West Hedding Street San Jose, CA 95110 Dear Supervisors Cortese and Chavez: This Management Audit of the County of Santa Clara’s Department of Correction (DOC) was authorized by the Board of Supervisors, pursuant to the Board’s power of inquiry specified in Article III, Section 302(c) of the County of Santa Clara Charter. The Board added this audit after considering the annual County-wide audit risk assessment conducted by the Management Audit Division in accordance with Board policy. This audit was conducted in conformity with the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) Audit Standards. The purpose of the audit was to examine the operations, management practices, and finances of the DOC, and to identify opportunities to increase the Department’s efficiency, effectiveness and economy. This report includes seven findings and 15 recommendations. In the responses attached to this audit, the DOC and the Office of the Sheriff expressed agreement or partial agreement with all the recommendations. The Santa Clara County Supervisor Court expressed disagreement with one recommendation. Implementation of the recommendations would result in improvements, particularly improvements that would reduce various financial and operational risks, but we cannot readily quantify the value of such savings. For instance, implementation of the recommendations in this report would: Board of Supervisors: Mike Wasserman Cindy Chavez District 1 District 2 County Executive: Jeffrey V. Smith Dave Cortese District 3 Susan Ellenberg District 4 S. Joseph Simitian District 5 2-025 • Reduce the risk that inmates are released in error and therefore increase public safety; • Ensure that the DOC has the kitchen and laundry assets needed to meet its obligations under State law; • Bring practices in line with policy regarding inmate mail; • Improve the safety and security of DOC and Sheriff personnel by training more staff on the detection of contraband in inmate mail; • Enable the departments to avoid potential safety and security issues and related litigation costs by eliminating the opportunity for parties with their own interests to give money to inmates; • Reduce the risk that inmate property becomes lost and that inmates are not appropriately compensated for lost property; • Reduce recidivism by establishing a pilot vocational training program that bestows a more valuable, portable credential to inmates. The certificates earned in the DOC and Sheriff’s current program are only minimally beneficial to inmates seeking post-release employment. We would like to thank all of the staff and management of the Department of Correction and the Office of the Sheriff for their generous and patient assistance to us during this audit. Their cooperative assistance and helpful insights are greatly appreciated. In addition, we would like to thank the Court Services Division of the Santa Clara County Superior Court for assistance with a portion of this audit. Respectfully submitted, Cheryl Solov Board of Supervisors Management Audit Manager cc: Supervisor Mike Wasserman Supervisor Susan Ellenberg Supervisor S. Joseph Simitian Jeffery V. Smith, County Executive James R. Williams, County Counsel Project Staff: Gabe Cabrera Alice Hur Joshua Oehler Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Table of Contents This document is linked. Click on a section to view. Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 Section 1: Errant Inmate Release 13 Section 2: Developing and Funding a Fixed Assets Plan 17 Section 3: Returned Inmate Mail 23 Section 4: Detecting Contraband in Inmate Mail 29 Section 5: Payments to Inmates from Undisclosed Sources 35 Section 6: Lost Inmate Property 39 Section 7: Building a Better Vocational Training Program 47 Attachments A-I 53 Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 55 Attachment B: DOC List of Accomplishments 69 Attachment C: Minute Order-Redacted and Revised 71 Attachment D: Minute Order-Redacted 73 Attachment E: Other Jurisdictions 75 Attachment F: Request for TouchPay Data 77 Attachment G: Request for Information to Aramark 79 Attachment H: County Executive’s Response 81 Attachment I: Sheriff’s Response 85 Attachment J: Santa Clara County Superior Court’s Response 89 Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Executive Summary Section 1. Errant Inmate Release This section addresses the 2017 errant inmate release and recommends that the Department of Correction (DOC) urge the Santa Clara County Superior Court to modify its minute order form in the manner described in this section to reduce the likelihood of another errant release. Section 2. Developing and Funding a Fixed Assets Plan This section addresses the DOC’s aging kitchen and laundry equipment and recommends that the DOC develop a multi-year fixed assets plan based on the useful life and replacement costs of each asset and seek to fund it as soon as possible. Section 3. Returned Inmate Mail This section addresses the DOC’s policies around returned inmate causing inmate confusion and recommends that the DOC notify inmates with a receipt explaining the reasons for returned mail as well as clarify what constitutes “inappropriate” mail. Section 4. Detecting Contraband in Inmate Mail This section addresses the DOC’s policies around the detection of contraband in inmate mail and recommends that the DOC require its Custody Support Assistants to attend existing Sheriff Deputy trainings on contraband, evidence and the screening and distribution of mail, among other recommendations. Section 5. Payments to Inmates from Undisclosed Sources This section addresses fraternization between County inmates and staff and recommends that the DOC and Sheriff explicitly prohibit any of their staff from giving money to inmates through any means. Section 6. Lost Inmate Property This section addresses the DOC’s policies around lost inmate property and recommends that the DOC add one full-time equivalent (FTE) Office Specialist II to clean and manage the claim tracking logs in the jails and generate claims summary reports for the Sheriff, among other recommendations. Section 7. Building a Better Vocational Training Program This section addresses the DOC and Sheriff’s existing vocational training program for inmates and recommends that they contract with a different vendor or establish a one-year pilot registered apprenticeship program that bestows a more valuable credential to inmates. -1- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Introduction INTRODUCTION This Management Audit of the County of Santa Clara’s Department of Correction (DOC) was authorized by the Board of Supervisors, pursuant to the Board’s power of inquiry specified in Article III, Section 302(c) of the County of Santa Clara Charter. The Board added this audit after considering the annual County-wide audit risk assessment conducted by the Management Audit Division in accordance with Board policy. PURPOSE, SCOPE, AND OBJECTIVES The purpose of the audit was to examine the operations, management practices, and finances of the DOC, and to identify opportunities to increase the Department’s efficiency, effectiveness and economy. The functions of the DOC depend on whether the functions are considered administratively or budgetarily. Administratively, the DOC consists of four functions carried out by about 120.5 positions: Food Services, Inmate Laundry, Warehouse and Administrative Booking. The first three units provide food and laundry services to inmates, and order and maintain storage and supplies. The Administrative Booking unit handles booking of arrestees brought to jail, accepts payments for bail and for use in the jail commissary, and processes inmates for release. These functions are overseen by a Chief of Correction appointed by the Board, rather than the Sheriff. However, the DOC budget unit consists of an additional 244 staff who carry out 17 additional functions. Those functions are overseen by the Sheriff, not the DOC Chief. A memo from County Counsel to the Board’s Finance and Government Operations Committee in 2016 summarizes key historical events in the oversight of County correctional functions and is provided as Attachment A on page 55 of this audit report. A list of the DOC budget unit expenditures by cost center is shown Figure I.3 on page 8 of this Introduction. Although the focus of the audit was on the four functions reporting to the DOC Chief, the scope of this audit included the DOC functions as budgeted in the DOC budget unit (240), rather than just the four functions that administratively report to the DOC Chief. AUDIT TIMELINE Work on this audit began with an entrance conference with DOC management on January 17, 2018, and a draft report was issued to Office of the County Executive on October 15, 2019, and to the Sheriff on October 30, 2019. We also sent the draft report to the Office of the County Counsel on October 9, 2019, and a relevant section of the draft report to the Court Services Division of the Santa Clara County Superior Court on October 17, 2019. An exit conference was held with the County Executive’s Office on October 31, 2019, and with the Sheriff’s Office on December 18, 2019. During work on this audit the then Interim Chief of Correction retired and the Board appointed the County Executive in August 2018 to serve as Interim Chief. -3- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Introduction We also held an exit conference with Court Services on October 23, 2019 via telephone. Finally, County Counsel provided us with feedback on the draft report on January 12, 2020. A revised (final) report incorporating feedback from these exit conferences was issued to the County Executive, County Counsel, the Sheriff and Court Services on September 8, 2020. The audit’s main objectives were to answer the following questions: • • • Are internal controls governing financial aspects of DOC’s functions adequate to provide reasonable protections against waste, fraud and abuse? Are these functions designed and executed in a manner that supports the goals of the County jail, such as punishment, care, treatment and rehabilitation? Do these functions comply with local, state and federal regulations? Are there opportunities to increase the safety, economy, efficiency or effectiveness of operations? AUDIT METHODOLOGY We interviewed both management and line staff. Management interviewed included the then Interim Chief of Correction and the managers of all four jail units under the Department of Correction (Food Services, Inmate Laundry, Warehouse and Administrative Booking). We also interviewed the new Food Services Manager hired in July 2018. Line staff interviewed were as follows. Within Food Services, we interviewed DOC’s only Dietician on staff who works to ensure that inmate meals are nutritionally complete and acceptable in quantity and quality. Within Laundry Services, we interviewed Custody Support Assistants (CSAs) and Supervising CSAs with responsibility for the clean replacement of inmate clothing and bedding. Within Warehouse Operations, we interviewed Warehouse Materials Handlers and Storekeepers with responsibility for storage and stocking supplies. Within Administrative Booking, we interviewed Law Enforcement Records Specialists with responsibility for preparing confidential criminal justice records. We also interviewed CSAs and Supervising CSAs with responsibility for managing the inmate mail and property rooms, as well as the Correctional Industries Program, which provides trades work experience to inmates. As a part of fieldwork for this audit, we toured DOC’s kitchen and laundry facilities at Elmwood Correctional Complex, food and supply warehouses, the administrative booking unit, inmate property rooms at both Elmwood and the Main Jail Facility, and the Correctional Industries workshop. We also accompanied DOC staff on a laundry delivery run between the County’s two jail facilities, witnessed DOC staff fulfilling a facility maintenance request, and observed kitchen operations. We reviewed DOC’s current and prior year budgets, as well as actual costs. We reviewed contracts and memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with external entities. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -4- Introduction We reviewed the County’s Nutrition Standards adopted by the Board of Supervisors in 2012, and their impact on the custodial population, commissary sales and inmate requests for medical and religious diets. We also reviewed a sample of inmate grievances pertaining to DOC functions, as well as various inmate mail and property claims logs. We reviewed all relevant local laws and regulations regarding adult custody operations including the County Charter, and DOC’s policy and procedure manual, as well as relevant state and federal laws and regulations. COMPLIANCE WITH GENERALLY ACCEPTED GOVERNMENT AUDITING STANDARDS This management audit was conducted under the requirements of the Board of Supervisors Policy Number 3.35 as amended on May 25, 2010. That policy states that management audits are to be conducted under generally accepted government auditing standards (GAGAS) issued by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. We conducted this performance audit in accordance with GAGAS as set forth in the 2011 revision of the “Yellow Book” of the U.S. Government Accountability Office. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. In accordance with these auditing standards, we performed the following procedures: Audit Planning – This audit was selected by the Board of Supervisors using a risk assessment tool developed at the Board’s direction by the Management Audit Division. After audit selection by the Board, a detailed management audit work plan with an estimate of audit work hours was developed and provided to the Department. Entrance Conference - An entrance conference was held with DOC management to introduce the audit team, describe the audit program and scope of review, and to respond to questions. A letter of introduction from the Board, the audit work plan and a request for background information were also provided at the entrance conference. Pre-Audit Survey - Audit staff reviewed documentation and other materials to obtain an overall understanding of the Department’s operations, and to isolate audit areas that warranted more detailed assessments. Field Work - Field work activities were conducted after completion of the pre-audit survey, and included: (a) survey interviews of all levels of DOC and Sheriff staff; (b) tours and observations of various DOC operational areas and functions; (c) a review of departmental policies and procedures, as well as relevant state and federal laws and regulations (d) analyses of external contracts and MOUs, inmate grievances, commissary accounts, and other datasets provided by the Department. Draft Report – A draft report was provided to the County Executive and Sheriff on October 15, 2019 and October 30, 2019, respectively, to describe the audit progress and to share general information on our preliminary findings and conclusions. We also provided the draft report to County Counsel on October 9, 2019 for legal review and feedback. Finally, we provided only a relevant section of the draft report to the Superior Court’s Court Services Division on October 17, 2018 to review and comment. -5- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Introduction Exit Conference – An exit conference was held with the County Executive and the Sheriff on October 31, 2019 and December 18, 2019, respectively, to obtain views on the report findings, conclusions and recommendations, and to make fact-based corrections and clarifications as appropriate. We also held an exit conference with Court Services on October 23, 2019 via telephone. Finally, County Counsel provided us with feedback on January 12, 2020. Following these meetings, a revised draft was provided to the County Executive, County Counsel, the Sheriff and Court Services on September 8, 2020 for use in preparing their formal written responses. Final Report - A revised (final) report was prepared and issued on September 8, 2020. Written responses from the County Executive, Sheriff and Court Services are attached to the final report. BACKGROUND County Jails Management Figure I.1 below is intended to provide a brief timeline of County jails management based on our analysis of publicly available documents. For a more detailed history, we refer the reader again to County Counsel’s September 30, 2016 memorandum to Committee furnished as Attachment A on page 55 of this audit report. Figure I.1: Timeline of County Jails Management Source: Management Audit Division analysis of legal history. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -6- Introduction DOC Organization Figure I.2 below shows DOC’s organizational structure relative to the Board of Supervisors, the County Executive and the Sheriff. As mentioned earlier, the County’s Administration budgets several recurring Sheriff expenditures in the DOC’s budget because they relate to DOC operations. Under the grey-colored Sheriff’s box in Figure I.2, these expenditures are listed by “cost center”, which is how the Administration tracks expenses for budgeting and other purposes. Figure I.2: DOC Organizational Chart Source: Management Audit Division analysis of DOC’s organizational structure. FY 2018-19 Staffing Levels The FY 2018-19 adopted budget for the DOC included 364.5 Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) positions. Of these, only 120.5 FTE (33.1 percent) were in the DOC’s four Board-assigned functions, namely Food Services, Inmate Laundry, Warehouse and Administrative Booking. The rest of the positions (244.0 FTE, or 66.9 percent) were in the Sheriff’s Office, as detailed by cost center in Figure I.3 on page 8. -7- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Introduction Figure I.3: DOC Staffing by Cost Center Cost Center Description FTEs 3428 Food Services 74.0 3432 Administrative Booking 41.5 3438 Laundry 3.0 3449 Warehouses 2.0 Subtotal-DOC Functions 120.5 3400 Administration 10.0 3401 Budget Management & Cost Accounting 20.0 3405 Personnel 7.0 3406 Academy-Cadets (unfunded) 70.0 3407 Operational Standards & Inspection 1.0 3408 ADA Compliance Unit 1.0 3413 Information Systems 6.0 3424 Training 1.0 3426 Main Jail 42.0 3433 Inmate Screening 2.0 3435 Classification 7.0 3436 Elmwood 30.0 3437 Industries 5.0 3440 Operations 11.0 3446 Programs 25.0 3454 Grievance Unit 5.0 3455 Jail Transition Team 1.0 Subtotal-Sheriff FTEs in DOC’s Budget 244.0 Grand Total 364.5 FY 2018-19 Adopted Budget The FY 2018-19 adopted budget for the DOC included total expenditures of $111,827,710 which were offset by combined revenues and expenditure transfers of $3,994,874, resulting in net expenditures of $107,832,836, as shown in Figure I.4 on page 9. The FY 2019-20 adopted and FY 2020-21 initial recommended budgets were similar in costs and total budgeted staff. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -8- Introduction Figure I.4: DOC FY 2018-19 Adopted Budget FY 2018-19 Adopted Amount Expenditures Salaries & Benefits $42,558,988 Services & Supplies $69,268,722 Expenditures-Total $111,827,710 Expenditure Transfer $(187,342) Revenues $3,807,532 Revenues-Total $3,807,532 Revenues Net Cost $107,832,836 Source: FY 2018-19 Santa Clara County Adopted Budget. TOPICS REQUIRING ADDITIONAL REVIEW During the course of a management audit, certain issues may be identified and brought to the attention of the agency being audited and the Board of Supervisors, even though a specific finding is not included in the report due to insufficient information or time to complete the analysis, or other factors. Four such matters are described below. A fifth item regarding security cameras in the jails was provided confidentially to the Board due to security concerns. 1. Modified Diets - Both Medical and Religious - Should Be Monitored for Cost and Alternatives Pursuant to Article 12-Food of Adult Title 15 Regulations, inmates in local detention facilities must be served at least three meals per day. Some inmates must be served meals with medical dietary restrictions (e.g. no-salt-no-fat, no concentrated sweets, etc.) if prescribed by a doctor as part of treatment. Other inmates must be served meals with religious dietary restrictions as required by their religious denomination and approved by a facility chaplain. As shown in Figure I.5 on page 10, the number of medical and religious meals served by the DOC as a percentage of all meals served by the DOC has increased significantly since FY 2015-16, and reached a six-year high of 25.0 percent of all meals served in FY 2017-18. This is in part due to the effects of the Public Safety Realignment Act (2011) which transferred the management of certain low-level offenders, many of whom were older and sicker, from the state to local agencies. We bring this matter to the Board’s attention because medical and religious meals are costlier than regular meals and require more staff time to prepare. The DOC should monitor these meals closely with an eye for developing alternatives that mitigate their costs and preparation time. -9- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Introduction Figure I.5: Meal Types Over Time, FY 2015-16 Through FY 2017-18 FY 17-18 75% FY 16-17 16% 80% FY 15-16 14% 82% FY 14-15 12% 83% FY 12-13 13% 85% Regular Meals 7% 13% 85% FY 13-14 9% Medical Meals 12% 5% 4% 4% 3% Religious Meals Source: DOC Food Services. 2. DOC Food Services Did Not Evaluate Food Menus for Two Years in a Row (2016 & 2017) Food menus in local detention facilities must be evaluated for minimum nutritional and caloric requirements by a registered dietician at least annually (emphasis added), pursuant to Article 12-Food of Adult Title 15 Regulations. Ultimately, menus evaluations provide the rationale for either keeping or changing meals on food menus. DOC Food Services last evaluated menus in 2018, but did not do so in 2016 or 2017 citing as the reason “significant, ongoing workload increases in the Diet Office” such as its need to meet the above-noted increase in medical and religious diets.1 We believe that going forward DOC Food Services should prioritize the completion of menu evaluations above other duties to ensure that inmates receive the required nutrients and calories in their diets. 3. Tool Control for Operations Custody Support Assistants One of the job functions of Custody Support Assistants (CSAs) is to perform routine maintenance repairs within the correctional facilities. While larger repairs and work orders are fulfilled by the County’s Facilities and Fleet Department (FAF), and capital projects are completed by outside contractors, smaller maintenance jobs such as light-bulb changes are handled by on-site CSAs. The DOC’s Tool Control Policy establishes guidelines for maintaining control of maintenance tools used by these CSAs and other parties performing work within the jails. The policy includes instructions for inventorying tools, and tracking these items when they are in use. 1 DOC Food Services, FY 2018-19 Budget Request. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -10- Introduction While the DOC reported and provided evidence that outside contractors utilize - at minimum - a tracking sheet that lists all tools they have checked out on a particular date, CSAs do not use these tracking sheets for their minor repairs. When the Management Audit Division conducted an observation of the Main Jail, the on-duty CSAs did not check out their tools when performing a maintenance job, nor did they track these tools on the tracking sheet, or check the tools back in when the job was complete. This is a violation of the DOC’s Tool Control Policy, which requires “the use of tracking log sheets that will be developed and maintained by the facility or unit supervisor.” At minimum, these tracking logs should contain the following: • • • • • Date and time issued Item issued (description) Issuer Issued to whom (receiver) Date and time returned This noncompliance with the DOC’s Tool Control Policy poses a potentially serious safety and security risks. Poor tracking of tools can lead to lost items within areas of inmate traffic, which is where routine maintenance often occurs. These lost items could then be potentially used as inmate weapons or escape devices. For instance, in 2015, two inmates in a New York prison used contractors’ tools to escape from the facility. To mitigate these risks, we suggest that CSA Supervisors instruct all CSAs performing maintenance work to use a tool tracking sheet similar to the one used by contractors, and retain these tracking sheets by date to maintain a record of who last used these tools. 4. Inadequate Post Orders Post Orders are guidelines that discuss the duties and responsibilities of specific jobs within the DOC. Across the Department, there are functional areas such as Inmate Laundry that lack Post Orders entirely. Further, for the units that have them, the format and comprehensiveness of Post Orders vary widely from unit to unit. For example, while Main Jail has detailed Post Orders that contain post descriptions, staffing levels, and primary duties listed in the order that they should be completed, Post Orders for Elmwood’s Industries program is one paragraph long and outlines only general responsibilities. Post Orders are critical guiding documents that facilitate staff understanding of their roles and responsibilities. Without these Post Orders, it is possible that employees— particularly new hires—may overlook necessary procedures during their shifts. We suggest the DOC review all its existing Post Orders; prioritize Post Order development by unit; and draft these Post Orders according to a uniform template. DEPARTMENT ACCOMPLISHMENTS Audits typically focus on opportunities for improvements within an organization, program or function. To provide additional insight into the Department of Correction, we requested that the County Executive who is currently serving as Interim Chief of Correction to provide some of the Department’s noteworthy achievements. These are highlighted in Attachment B on page 69 of this report. -11- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Introduction RECOMMENDATION PRIORITIES The priority rankings shown for each recommendation in the audit report are consistent with the audit recommendation priority structure adopted by the Finance and Government Operations Committee of the Board of Supervisors, as follows: Priority 1: Recommendations that address issues of non-compliance with federal, State and local laws, regulations, ordinances and the County Charter; would result in increases or decreases in expenditures or revenues of $250,000 or more; or, suggest significant changes in federal, State or local policy through amendments to existing laws, regulations and policies. Priority 2: Recommendations that would result in increases or decreases in expenditures or revenues of less than $250,000; advocate changes in local policy through amendments to existing County ordinances and policies and procedures; or, would revise existing departmental or program policies and procedures for improved service delivery, increased operational efficiency, or greater program effectiveness. Priority 3: Recommendations that address program-related policies and procedures that would not have a significant impact on revenues and expenditures but would result in modest improvements in service delivery and operating efficiency. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -12- Section 1: Errant Inmate Release Section 1: Errant Inmate Release Background The Administrative Booking unit within the Department of Correction (DOC) is responsible for executing all court orders requiring action by the DOC, including releasing inmates upon completion of their sentences. Problem, Cause, and Adverse Effect On September 28, 2017, an inmate at the Elmwood Correctional Complex in Milpitas who had been sentenced to eight years in prison for robbery that day was mistakenly released from custody due to human error. A records clerk within DOC’s Administrative Booking unit misread the form (minute order) used by the Court Services Division of the Superior Court of California, County of Santa Clara to record the Court’s proceedings, as required by Government Code Section 69844. The form is designed for use in Santa Clara County only. It is pre-printed with all possible court orders. A checkbox designates the order issued by the judge in each case. In this instance, the records clerk misread the box labeled “committed” (to jail or prison), which was checked, as “released.” The checkboxes for “committed” and “released” are adjacent to each other on the form. According to Administrative Booking staff, the format of the form itself contributed to staff misunderstanding of the judge’s orders, ultimately resulting in the errant inmate release. Five days elapsed before this mistake was noticed by other booking staff, at which time investigators from the Sheriff’s Office began to search for the inmate. On October 5, 2017, the inmate was located and taken back into custody without incident. In addition to the expense of apprehending the inmate, such instances endanger the community as the inmate could flee or commit other crimes while free. Recommendations To reduce the likelihood of another errant release, the Administrative Booking unit issued a new directive on October 11, 2017, requiring records supervisors to review all court orders that are checked “released”. To reduce that likelihood even further, the Department of Correction should urge the Santa Clara County Superior Court to modify its minute order form in the manner described in this report section and as illustrated in Attachment C on page 71. Savings, Benefits, and Costs Implementation of this recommendation would have no fiscal impact upon the County’s General Fund, but it would reduce the risk that inmates are released in error and therefore, increase public safety However, Superior Court would have to incur unplanned expenditures for re-designing and re-printing the form, and re-training its staff and partner agencies, such as the District Attorney and Public Defender, on how to read it. -13- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 1: Errant Inmate Release FINDING On September 28, 2017, an inmate at the Elmwood Correctional Complex in Milpitas was mistakenly released from custody due to human error. Earlier that day the inmate was sentenced for two separate criminal cases. He was credited for time served in a stolen vehicle case, and sentenced to eight years in prison in an armed robbery case. A records clerk within DOC’s Administrative Booking unit misread the presiding judge’s order in the armed robbery case, interpreting the box labelled “committed” (to jail or prison), which was checked, as “released.” A total of five days elapsed before this mistake was noticed by other booking staff, at which time investigators from the Sheriff’s Office began to search for the suspect. On October 5, 2017, the suspect was located and taken back into custody without incident. New Policy Directive DOC’s Administrative Booking unit is responsible for processing and maintaining all booking records for each inmate. It is also responsible for executing all court orders requiring action by the DOC, including those were an inmate is sentenced to the California Department of Correction and Rehabilitation (CDCR). Prior to the errant release, booking staff independently processed court orders under general supervision. After the errant release, DOC issued a new directive requiring booking supervisors to review all CDCR court orders “which are sentence deemed served and ordered released.”2 To acknowledge their review, booking supervisors must place their unique identification number (or “B number”) on the court order. By doublechecking CDCR court orders in this manner, the likelihood of another errant release is significantly reduced. Minute Orders The minute order is the official record of the Court’s proceedings. It is required by law3 and generally includes the same basic information showing who was present at a given court hearing and what took place, and what findings and orders the court made. However, the format of the minute order form can vary between jurisdictions. For instance, the length of the form used by the Superior Court is a single page, while in other jurisdictions it is several pages long. The reason for the varying lengths of forms lies in whether the reasoning, detail and supporting law is included in the document. 2 3 Nunes, Dana, Law Enforcement Records (LER) Supervisor. Memorandum re: A.B. Procedure #901 CDCR Releases (LER Specialist review). 11 Oct. 2017. California Government Code. Section 69844. Added 1955, amended 1959. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -14- Section 1: Errant Inmate Release While the cause of the errant inmate release in this instance was human error, there was at least one major contributing factor. According to Administrative Booking staff, the format of the form itself contributed to the records clerk’s misunderstanding of the presiding judge’s orders. Attachment D on page 73 of this audit is a redacted copy of the actual form that was misread by the records clerk. As can be seen, the size of the font on the form is small and difficult to read. In addition, the form is extremely dense. For example, it contains: • • • • • 228 empty checkboxes that must checked as appropriate, 109 acronyms, 103 abbreviations, 88 blank spaces that must be filled in as appropriate, and 26 references to State law. However, the single biggest problem with the format of the form is that the checkbox labelled “committed” is adjacent to the checkbox labelled “released”, which increases the likelihood that booking staff will mistake a checked box for an unchecked box and visa-versa. Therefore, the Chief of the Department of Correction should urge the Santa Clara County Superior Court to modify its minute order form by adding a new checkbox to top of the form instructing its court clerks to check it only if they check the box labelled “released” at the bottom of the form, as shown in Attachment C on page 71. The proposed checkbox is colored red and is larger than the others. By modifying the form in this manner, the likelihood of an errant release by DOC’s Administrative Booking staff that process the form is further reduced. Booking unit staff also suggested adding a “Notes” section to the bottom of the page, as shown in Attachment C on page 71. Court Services staff reported that the Superior Court contracts with a private vendor to print the minute order form, and that it uses the form to record court proceedings at six of the Court’s eight locations in the County. The form itself is split into two halves. The lower half is printed by the vendor with all possible court orders. The upper half is intentionally left blank by the vendor until the Superior Court populates it with information specific to each case, such as the name of the defendant, case number, charges, etc. According to Court Services staff, modifying the minute order form in the manner described in this report and as illustrated in Attachment C on page 71 would require the Superior Court to incur unplanned expenditures for re-designing and re-printing the form and re-training its staff and partner agencies, such as the District Attorney and Public Defender, on how to read the new form. Staff could not estimate these costs. However, the Management Audit Division believes that whatever these costs are they should be measured against the County’s costs of re-apprehending inmates released in error. CONCLUSION The DOC’s Administrative Booking unit has taken steps toward reducing the risk of releasing inmates in error; it now requires booking supervisors to double-check all CDCR court orders which are sentence deemed served and ordered released. It is our belief that more steps should be taken to reduce that risk. -15- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 1: Errant Inmate Release RECOMMENDATIONS The Department of Correction should: 1.1 Urge the Santa Clara County Superior Court to modify its minute order form in the manner described in this report section and as illustrated in Attachment C on page 71. (Priority 1) SAVINGS, BENEFITS, AND COSTS Implementation of Recommendation 1.1 would have no fiscal impact upon the County’s General Fund, but reduce the risk that inmates are released in error. It would also increase public safety. However, Superior Court would have to incur unplanned expenditures for re-designing and re-printing the form and re-training its staff and partner agencies on how to read it. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -16- Section 2: Developing and Funding a Fixed Assets Plan Section 2: Developing and Funding a Fixed Assets Plan Background To meet inmate diet and clothing exchange requirements under State law, the Department of Correction (DOC) runs in-house kitchen and laundry facilities at Elmwood Correctional Complex in Milpitas, California. Problem, Cause, and Adverse Effect The DOC’s kitchen and laundry assets have reached or exceeded their estimated useful lives, and are prone to breakdowns which require expensive repairs. The average annual cost of these repairs over the past five years is $37,242 (kitchen) and $102,803 (laundry). According to DOC staff, equipment breakdowns also lead to other unplanned expenditures. For example, when dough mixers or dividers/ rounders are down for repairs, DOC Food Services cannot make its own bread and purchases bread from outside vendors. This purchased bread is more expensive and less healthy (because it contains more preservatives) than DOC’s in-house made bread. It is virtually impossible to quantify these and other unplanned costs because they are not separately tracked by the Department or clearly identified on invoices. Nevertheless, as illustrated by the bread example, properly functioning equipment is vital for the health and overall well-being of the County’s inmates. However, DOC has neither a fixed assets plan nor reserves for the maintenance, repair or replacement of its kitchen and laundry assets. Recommendations The Department of Correction should develop a multi-year fixed assets plan based on the useful life and replacement costs of each asset and seek to fund it as soon as possible. Savings, Benefits, and Costs We estimate that the Department would need to expend an estimated $3.8 million over the next five years to adequately fund the plan. This level of funding may not be immediately feasible but is essential for the Department to meet its obligations under State law. -17- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 2: Developing and Funding a Fixed Assets Plan FINDING Background All the DOC’s owned kitchen and laundry assets have reached or exceeded their estimated useful lives, and are fully depreciated, based on data obtained from the County’s SAP financial system on April 9, 2019.4 This includes: • • 111 assets originally valued at $3 million and capitalized in SAP as “General Equipment”, each item costing $5,000 or more (e.g. refrigerators, freezers, ranges, ovens, washers, dryers, etc.). 47 assets originally valued at about $75,000 and tracked (not capitalized) as “Low Value Expense Items”, each item costing from $1,000 to $4,999, such as computers, monitors, laptops, printers, etc. Using SAP data, we determined that the average age of these assets, on April 9, 2019, was 16 years. We also determined that heavy usage of these assets is routine, as the County’s jails operate all year round, and the Department is required to meet minimum standards regarding the frequency of inmate meals and the clean replacement of laundry, pursuant to Title 15 of the California Code of Regulations. Specifically: • • DOC Food Services must prepare at least three meals (including one hot meal) per inmate per day; and, DOC Laundry Services must launder and replace most standard-issue inmate clothing, bedding and linens on a weekly basis. Because of their old age and heavy usage, DOC’s kitchen and laundry equipment are prone to wearing out and breaking down. As such, DOC employs an Institutional Maintenance Engineer to maintain and repair them. However, some equipment is “specialty machines,” such as large-volume washers and dryers, which require special training to repair. These machines are repaired by contracted vendors. These repairs have cost the DOC approximately $700,000 over the last five years, or an average of $140,000 per year.5 Santa Clara County’s 2% Maintenance Funding Policy Does Not Cover Fixed Assets In 1998, the Board of Supervisors adopted a policy to set a level of funding for facilities maintenance based on the value of County-owned buildings. However, the policy does not cover equipment, according to staff of the County’s Facilities Department. Funds to pay the Institutional Maintenance Engineer and contracted vendor repairs are allocated to the DOC as part of the County’s annual budget process. The Department has no reserve funding available for the maintenance, repair or replacement of any of its equipment. 4 5 According to the County’s Fixed Asset Administrative Guide (pg. 8), the “estimated useful life” of an asset refers to “its expected economic useful life (in number of months or years) from the date placed in service to the projected retirement date”. This includes payments of $186,212 to Western State Design (vendor no. 1011224) and payments of $514,013 to R&R Refrigeration (vendor no. 1008523) from FY 2014-15 through FY 2018-19. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -18- Section 2: Developing and Funding a Fixed Assets Plan Best Practice According to the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA), best practices call for governments to develop capital asset maintenance and replacement plans: “GFOA recommends that local, state and provincial governments establish a system for assessing their assets and then appropriately plan and budget for any capital maintenance and replacement needs.”6 GFOA recommends developing a policy to require an assessment of the physical condition of each asset and establishing condition/functional performance standards to be maintained for each type of asset. GFOA also recommends using this condition assessment and related standards as a basis for a multi-year plan for asset maintenance and replacement. Having a plan would enable the Department to anticipate and fund its equipment needs, and to set aside funds that would be separate from the Board of Supervisors’ annual budget funding allocations. Because DOC’s kitchen and laundry assets are essential to the health and overall well-being of the County’s inmates, there is a critical need to ensure that these assets are adequately funded. As such, the Department should develop a multi-year plan based on the useful life and replacement costs of each asset. Funding a Fixed Asset Plan The acquisition value of the DOC’s existing kitchen and laundry equipment totaled approximately $3.1 million, and even though DOC’s Institutional Maintenance Engineer and contracted vendors have been able to prolong their use, their current book value is $0. We estimated annual expenditures to replace all the DOC’s kitchen and laundry assets within the next five years. These estimates are general, and do not include the results of an assessment of the physical condition of each asset. Nor do these estimates account for what assets are in the worst shape and should be replaced first. Estimated expenditures are based on original purchase prices, adjusted by the Consumer Price Index for inflation. These estimated expenditures, averaged over five years, are shown in Figure 2.1 on page 20. As can be seen, the Department needs a minimum of approximately $760,000 in annual set asides over the next five years. 6 GFOA Best Practice, Asset Maintenance and Replacement, March 2010. -19- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 2: Developing and Funding a Fixed Assets Plan Figure 2.1: Estimated Annual Expenditures Needed for Replacement of DOC’s Kitchen and Laundry Equipment, FY 2019-20 Through FY 2023-24 FY 2019-20 FY 2020-21 FY 2021-22 FY 2022-23 FY 2023-24 5-Year Total $480,882 $480,882 $480,882 $480,882 $480,882 $2,404,409 $22,674 $22,674 $22,674 $22,674 $22,674 $113,368 Subtotal $503,556 $503,556 $503,556 $503,556 $503,556 $2,517,778 General Equipment $254,915 $254,915 $254,915 $254,915 $254,915 $1,274,574 $1,301 $1,301 $1,301 $1,301 $1,301 $6,505 Subtotal $256,216 $256,216 $256,216 $256,216 $256,216 $1,281,079 Grand Total $759,771 $759,771 $759,771 $759,771 $759,771 $3,798,856 Kitchen General Equipment Low-Value Assets Laundry Low-Value Assets Source: Management Audit Division. In keeping with GFOA’s best practice, the Department should develop an equipment replacement plan and present it to the Board of Supervisors for approval. The County should set aside/reserve these future funds for the plan. We noted that DOC Food Services received $324,000 as part of its FY 2019-20 budget request of the Board to replace several kitchen assets, including but not limited reheating ovens, transport carts and a dough divider/rounder. This $324,000 should be subtracted from the plan’s first year costs. CONCLUSION The Department of Correction does not have a Board-approved equipment replacement plan, and has no reserves for the maintenance, repair or replacement of any of its fixed assets. All the DOC’s existing assets are outdated, and some are dilapidated, but there are no funds earmarked to replace them. To adequately meet its current and future equipment needs, the Department has to allocate an estimated $3.8 million over the next five years. This funding commitment may not be immediately feasible, but the Department should develop a plan and seek to fund it as soon as possible. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -20- Section 2: Developing and Funding a Fixed Assets Plan RECOMMENDATIONS The Department of Correction should: 2.1 Establish a policy to require an assessment of the physical condition of each kitchen and laundry asset. The condition assessment should occur annually, and the results of the assessment should be reported to the Chief of Correction. (Priority 3) 2.2 Develop and maintain a five-year fixed assets plan and present the plan to the Board of Supervisors for approval annually. The plan may be a separate document but should be integrated into the Department’s annual budget. (Priority 3) SAVINGS, BENEFITS, AND COSTS To the extent that the Department is able to set aside/reserve funds for the plan, the Department will ensure that its kitchen and laundry assets are safe, well maintained and modern. In turn this will ensure that the Department has the equipment needed to ensure it meets its obligations under State law. -21- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Section 3: Returned Inmate Mail Section 3: Returned Inmate Mail Background The Department has a publicly available set of rules for incoming mail addressed to inmates, which includes a list of items not allowed into the County’s jails. Custody Support Assistants (CSAs) assigned to the Mail Room are responsible for ensuring that these mail guidelines are met. Items that do not meet these criteria are recorded in a Returned Mail log and either returned to sender or placed with the inmate’s other stored property if there is no return address. Problem, Cause, and Adverse Effect The Department’s practices for returning inmate mail to sender do not align with the Department’s policy on inmate correspondence. According to the policy, “Inmates shall be notified when incoming or outgoing letters are rejected.” However, during a site visit of the mail room conducted for this audit, DOC staff reported they only notify inmates of opened mail returned to sender. If CSAs send back mail unopened, the inmate does not receive any written notification. This practice has generated confusion among inmates, who repeatly submit grievances asking why they are not receiving their mail, and extra work for Mail Room CSAs, who respond to these grievances. Within a sample of 83 mail-related grievances, we identified 13 (or 16 percent) of this nature. The Inmate Rulebook does not indicate notification exceptions for returned inmate mail. Additionally, both inmates and Mail Room CSAs seem to lack consistency and clarity on what constitutes prohibited “inappropriate” mail. The July 2018 revision of the Inmate Rulebook cites “sexually explicit or suggestive images and/or graphic nudity” in this regard, but our grievance sample suggested that some mail items potentially falling into these categories are allowed, while other items are returned to sender. If CSAs apply different standards of “appropriateness” to their mail review, this can lead to inmate perceptions of unfairness. Further, multiple studies show that family contact during incarceration reduces recidivism. Consequently, unnecessarily withholding mail minimizes beneficial family contact. Recommendations To mitigate inmate confusion and reduce the volume of inmate grievances concerning mail, the Department should notify inmates of all mail returned to sender, including unopened items, per its policy on inmate correspondence. Additionally, the two Supervising CSAs should work together to develop an annual training, with concrete examples, on what constitutes “inappropriate” mail to improve consistency. The guidelines from this training should be integrated into the Inmate Rulebook, staff policies, and the Department’s website. Savings, Benefits, and Costs Implementing these recommendations will give inmates a better understanding of when and why mail addressed to them is being returned. Further, the proposed training may help reduce instances of inmates not receiving family communications due to differences in what CSAs deem as “inappropriate.” While implementing both recommendations would take additional staff time, they would also likely reduce the staff time spent on responding to grievances on returned mail. -23- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 3: Returned Inmate Mail FINDING The Department7 describes guidelines for inmate mail on its website. Incoming inmate mail must include the inmate’s booking number and Personal File Number (PFN), and newspapers, magazines, periodicals, and books delivered to inmates must be mailed directly from the publisher. In addition to these rules, the website lists prohibited items that will not be accepted through mail service. Cardboard, hard bound books, flowers, and food items are examples of prohibited items. The Department has a Mail Room post, and Custody Support Assistants (CSAs) assigned to this post are responsible for sorting, examining, and labeling inmate mail with housing units for delivery. Any mail that does not follow department guidelines is returned to the sender. If there is no identifiable return address, the item—barring any illegal substances—is placed with the inmate’s other stored property that is collected when inmates are first housed. Mail Room CSAs input all returned mail and the reasons for return in a Returned Mail Log. Inmates are to be informed of returned mail per departmental policy on inmate correspondence, which states, “Inmates shall be notified when incoming or outgoing letters are rejected.” CSAs fill out a triplicate form that describes why the mail is being returned. One copy of the form is given to the sender; one is given to the inmate that the mail was addressed to; and DOC retains a copy. Department Policies Around Returned Mail Notices Causing Inmate Confusion The Department’s practices around returned mail do not align with its inmate correspondence policy. The Management Audit Division conducted a site visit of the Main Jail Mail Room and shadowed one of the Mail Room CSAs, who reported exceptions to inmate notifications for returned mail. While inmates are notified of returned mail that has been opened and examined, they do not receive a form discussing the reasons for returned unopened mail, such as when an envelope has stickers or suspicious markings. In these instances, only the sender receives notice of the reasons for return. It is unclear why the Department’s Mail Room CSAs have interpreted departmental policy to allow for exceptions for unopened mail, as there are no discussions of these exceptions in the facility’s post orders. This practice has resulted in inmates submitting multiple grievances around why they are not receiving their mail. In a sample of 83 grievances related to inmate mail, 13 grievances (16 percent) were inquiries on this matter.8 Multiple responses from CSAs explicitly stated that inmates were not informed of the returned items because the mail was left unopened. 7 8 “The “Department” refers to the Department of Correction. While inmate mail falls under the legal authority of the Sheriff’s Office, staff handling this responsibility are funded out of the Department of Correction’s budget. There were several grievances about inmates not receiving mail in addition to the 13 identified, but grievance responses from CSAs indicate that the facility never received incoming mail for these inmates. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -24- Section 3: Returned Inmate Mail One grievance response from CSAs stated that this policy is contained in the Inmate Rulebook, but the Inmate Rulebook only states, “In the event any item is withheld, you will be provided a receipt if the item is placed in your property.” The inmate orientation video for Main Jail, which is shown to inmates upon their arrival, also states that receipts will be given for withheld items. This provision does not speak to receipts for opened versus unopened mail, and could be interpreted to mean that all withheld mail will result in a notice explaining the reason for withholding. Aside from inmates being inadequately informed of the Department’s exceptions to its rules on returned mail notifications, the purpose of these exceptions is not clear. Whether mail is opened or unopened before it is returned to sender should not affect inmate notification according to the written policy. Not sending a notification for all returned items raises the likelihood that inmates will submit mail-related grievances later, in which case CSAs will have to respond to why the mail was returned anyway. This inefficiency could be avoided if the Department notified inmates of all returned mail, whether it has been opened or not, per its policy. The reasons for returned mail are currently recorded in the Returned Mail log, and it would take little additional effort for CSAs to fill out a triplicate notice with the same information. The existing form for opened mail only contains basic fields about the inmate, sender, and date received, and has checkboxes for the reasons for return (see Figure 3.1 below). Figure 3.1: Returned Mail Form While filling out these forms and delivering them for all returned mail would require some extra staff time, this time would likely be offset by the time saved from not having to respond to grievances on the reasons for returned mail. Further, this will ensure compliance with the department’s own policy. -25- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 3: Returned Inmate Mail Inconsistent Department Interpretations on “Inappropriate” Content in Inmate Mail One frequently cited reason for returned inmate mail is “inappropriate” content. The list of prohibited mail items on the Department’s website includes “[p]hotographs containing sexually explicit or suggestive images and/or graphic nudity.” Within the sample of 83 mail-related grievances referenced above, there were 15 grievances (18 percent) on the subject of mail returned for inappropriate content. The major issue with this mail guideline is that DOC’s CSA grievance responses indicate broad interpretations of the Department’s “inappropriateness” restriction. While several items were returned for nudity, per the rules on the Department’s website, other photographs were withheld for being “sexually suggestive,” despite the lack of nudity. Additional pieces of mail were returned for containing “suggestive” or “provocative” poses. And, in the most extreme case, an inmate did not receive photos of their newborn baby because the child was nude. Reviewing staff felt as though these baby photos would be inappropriate for a jail environment, which may house individuals charged with crimes against minors. However, from the publicly available guidelines on the Department’s website, as well as the rules contained within the Inmate Rulebook, it would be extremely difficult to ascertain that such photos would be denied without an insider understanding of jail operations. The wide range of reasons cited for “inappropriate content” has led to inmate perceptions of inconsistency and confusion over what is and is not allowed according to Department guidelines. One inmate grievance included an envelope with five items similar to their withheld mail that had been allowed by Mail Room CSAs. This sentiment of inconsistency was echoed in another grievance, which additionally asked for “a clearly defined and detailed guideline for what pictures can be received, and what is considered sexually explicit and/or suggestive.” The Department should internally clarify what constitutes prohibited “inappropriate” mail. In particular, images of family members should not be withheld unless absolutely necessary, given the numerous studies9 that demonstrate how family contact during incarceration reduces recidivism rates. Creating more defined guidelines would improve inmate perceptions of fairness and consistency in Mail Room practices, and exceptions such as the baby photo should be incorporated into these rules. These clarifications would reduce the likelihood that certain inmates will not receive mail simply because of the interpretation of “inappropriateness” held by the specific staff member reviewing their items. To achieve this consistency, the Department should more clearly define “inappropriate mail,” and incorporate it into the Department’s written policies. The Department should then issue an annual training, with concrete examples, to CSAs in order to ensure uniformity in Mail Room practices. The more detailed rules should also be added to the Inmate Rulebook and to publicly available lists of prohibited mail. 9 Studies by the Vera Institute and research published in Corrections Today all discuss the role of family and family contact in reducing recidivism. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -26- Section 3: Returned Inmate Mail CONCLUSION CSAs in the Mail Room determine whether incoming inmate mail meets the Department’s requirements. Items that do not meet these requirements are returned to sender. However, the Department’s practice of only notifying inmates of opened withheld mail and inconsistencies in returned “inappropriate” mail have led to inmate confusion and a substantial volume of grievances as a result. The Department should change its current practices on returned mail to align with departmental policy, and revise its policy around “inappropriate mail” to achieve greater consistency. The Department should ensure that all inmates and staff are informed of these changes. RECOMMENDATIONS The Department of Correction should: 3.1 Notify inmates with a receipt explaining the reasons for any returned mail, regardless of whether it is opened or unopened. Doing so would save the Department from answering grievances about reasons for withheld unopened mail. (Priority 3) 3.2 Clarify what constitutes “inappropriate” mail and create more detailed guidelines on this matter to be added to internal policies, the Inmate Rulebook, and publicly available lists of inmate mail rules. The CSA Supervisors should then conduct an annual training on these guidelines, with examples, to improve consistency in Mail Room practices. (Priority 3) SAVINGS, BENEFITS, AND COSTS Recommendations 3.1 and 3.2 would mitigate existing inmate confusion over why mail is being returned to sender; improve perceptions of fairness and consistency surrounding withheld mail; and reduce the volume of mail-related grievances. While implementing these recommendations may require some additional staff time and resources, the extra time and resource costs would at least be partially offset by the time saved in responding to inmate mail grievances. -27- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Section 4: Detecting Contraband in Inmate Mail Section 4: Detecting Contraband in Inmate Mail Background The sorting, searching, and labeling of inmate mail are functions funded through the Department of Correction’s (DOC) budget. Custody Support Assistants (CSAs) assigned to the Mail Rooms at the Main Jail and the Elmwood Correctional Complex examine inmate mail for contraband, and return to sender mail that does not fit Department requirements such as no padded envelopes or hard-bound books. If CSAs find contraband, they must immediately notify a sworn officer who handles the contraband using specific protocols. Problem, Cause, and Adverse Effect While the DOC has several safeguards against mail-smuggled contraband, such as a list of prohibited items, CSAs do not receive any specialized trainings on detecting contraband in mail. The DOC Policy Manual and post orders do not offer specific protocols for how to search for contraband. Further, existing policies do not discuss how CSAs can safely handle mail that might contain harmful contraband, despite state regulations that mandate employers to require “appropriate hand protection when employee’s hands are exposed to hazards.” This is consistent with an overall bare-bones training program for all CSAs, who receive minimal ongoing instruction after their initial orientation. However, for Mail Room CSAs, this lack of training is particularly problematic in that illicit substances may be smuggled into correctional facilities in sophisticated ways. For instance, employees at San Mateo County Jail identified letters addressed to inmates that had been dipped in methamphetamine. Without specialized training, Mail Room CSAs might miss critical indicators of contraband. Failure to detect these substances poses a safety risk to inmates and employees working in the custody facilities who could overdose on smuggled drugs. In 2017, four County inmates overdosed on a substance suspected to be Fentanyl, and were taken to Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, although how the drug was smuggled into the jails remains unclear. Recommendations Mail Room CSAs should attend existing Sheriff Deputy Academy trainings on contraband, evidence, and the screening and distribution of mail. In addition, they should be privy to portions of Sheriff’s Jail Intelligence Unit’s updates pertaining to new types of contraband and related safety precautions. Finally, policies and post orders should be revised to include safety protocols such as gloves for Mail Room CSAs. Savings, Benefits, and Costs CSA trainings and updates would require no additional personnel or programming since trainings are established courses and updates are existing activities. Revising post orders would take some additional time, but not enough to warrant new staff. The benefit of these recommendations is the reduced risk of drugs entering into County’s jail facilities. Potential savings include avoided Custody Health costs used to treat cases of drug overdose, litigation costs in the event an inmate dies of an overdose, and staff worker’s compensation claims stemming from possible exposure to contraband or hazards experienced responding to an incident. Implementing these recommendations will also better ensure departmental compliance with state regulations on employee safety. -29- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 4: Detecting Contraband in Inmate Mail FINDING Inmate mail is one of the more common avenues of smuggling contraband into correctional facilities. Jail and prison staff across the country have discovered illicit substances such as opiates, methamphetamine, and synthetic cannabinoids in letters and envelopes addressed to inmates. Within the DOC10, Mail Room CSAs are responsible for sorting, searching, and labeling all incoming inmate mail for delivery. This process involves examining mail items to ensure that they are compliant with the Department’s guidelines, and checking for contraband. Sheriff sworn staff who are responsible for handling and processing contraband are notified immediately on discovery of any such contraband. Mail Room CSAs take several measures to prevent mail-smuggled contraband from entering the jail. They remove and discard all stamps and sticky portions from envelopes and magazines, which may be used as vehicles for drugs (for instance, in the Pinellas County (Florida) Jail, Suboxone squares hidden behind stamps on inmateaddressed letters were sold to other inmates for $20 each).11 During the Management Audit Division’s site visit of the DOC’s Mail Rooms, we also observed a CSA holding all photographs and documents up to a light source in order to check for dark or opaque patches that may contain contraband. Further, the Department’s mail guidelines themselves have safeguards against contraband. For example, items having suspicious stains/markings or artwork done with crayons or marker—all of which may indicate drug-laced mail—must be returned to sender. The Department’s Returned Mail Log shows instances of mail being returned for stains, lipstick marks, and stickers, demonstrating that Mail Room CSAs are actively enforcing these policies. No Specialized Training or Documented Procedures and Protocols for Detecting and Protecting Against Mail-Smuggled Contraband While the Department has several precautions in place for preventing mail-smuggled contraband, CSAs assigned to the Mail Rooms do not receive any specialized training on how to detect drugs and other contraband in inmate mail. Department staff reported that their methods for identifying illicit substances mostly come from onthe-job learning. Although the Jail Intelligence Unit sometimes provides information on a one-off basis, there is no formal training in place for CSAs on the subject of contraband detection in mail. Department policies and Mail Room post orders offer little in the way of additional guidance, as these documents merely direct staff to “search mail for contraband” without specific procedures for doing so. 10 Staff funded from the DOC budget. 11 CorrectionsOne.com (20 Aug., 2013). Fla. inmate sold drugs hiding behind postage stamps. Retrieved from https://www.correctionsone.com/contraband/articles/6396212-Fla-inmate-sold-drugs-hiddenbehind-postage-stamps/. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -30- Section 4: Detecting Contraband in Inmate Mail This lack of training is problematic in that illicit substances may be smuggled into correctional facilities in sophisticated ways. For example, at San Mateo County Jail, correctional staff intercepted cards and letters that had been dipped in liquieified methamphetamine.12 In other cases, thick paper such as the kind used in greeting cards can be pulled apart, laced with drugs, and then glued back together with few visible signs of tampering.13 The lack of appropriate training or written guidelines on how to detect contraband in inmate mail raises the likelihood that Mail Room CSAs will miss critical indicators of contraband. To the extent that failure to appropriately detect contraband in mail occurs, it can result in safety hazards for inmates and responding custody staff and impose financial costs on the County. Inmates may overdose on drugs smuggled into the facility—some of which have dangerous and even life-threatening effects. For example, K-2, a synthetic cannabinoid, “can be up to 100 times as potent as the THC in cannabis,” and in 2016, New York City’s health department reported that the drug had resulted in 6,000 emergency room visits and two confirmed deaths in the city since 2015.14 This drug has been found in inmate mail in several jurisdictions, raising concerns that such a substance could enter into the County’s jail facilities and cause serious health issues for inmates. These concerns are amplified by the fact that inmates receiving drugs often sell or trade these substances to other inmates, broadening the radius of the health risk even further. If inmates overdose or suffer from side effects as a result of mail-smuggled contraband, it is ultimately the County that bears the cost. In 2017, four County inmates overdosed on a substance suspected to be Fentanyl, and were taken to Santa Clara Valley Medical Center.15 Based on analysis of 647 U.S. healthcare facilities, the average hospital cost of an overdose patient who was treated in the emergency room and released was $504, but the average increased to $11,731 for patients treated and admitted.16 Further, if a drug overdose results in an inmate’s death, this could result in additional costs in the form of negligence lawsuits to the County. To mitigate these risks as much as possible, it is critical that Mail Room CSAs are well-versed in methods for detecting contraband during their mail searches. This is especially true in the context of the Department receiving body scanners, which may increase the prevalence of mail-smuggled contraband as physically carrying illicit substances undetected becomes more difficult. 12 Daily Post. (28 Dec., 2017). 10 accused of trying to get drugs into jail through the mail. Retrieved from http://padailypost.com/2017/12/28/10-accused-of-trying-to-get-drugs-into-jail-through-the-mail/. 13 Leblanc, Matthew. (18 Jan., 2018). Scanner able to detect drugs hidden in mail sent to inmates. The Journal Gazette. Retrieved from http://www.journalgazette.net/news/local/20180118/scanner-ableto-detect-drugs-hidden-in-mail-sent-to-inmates. 14 Carroll, Linda. (13 Jul., 2016). Everything You Need to Know About K2, the Drug Linked to Mass Overdose. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/everythingyou-need-know-about-k2-drug-linked-mass-overdose-n608726. 15 While the Department did not confirm that the drug was transported into the facility via inmate mail, Department management has directed Mail Room staff to look out for the drug in their mail searches. Fentanyl has also been found in inmate mail in other jurisdictions. 16 LaPointe, Jacqueline. (7 Jan., 2019). Opioid Overdose Care Totals $1.94B in Annual Hospital Costs. Retrieved from https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/opioid-overdose-care-totals-1.94b-in-annualhospital-costs. -31- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 4: Detecting Contraband in Inmate Mail Training in the areas of contraband, evidence, and the screening and distribution of mail already exists within the Sheriff’s Office: Sheriff Deputy recruits take six hours of Academy classes on these topics. However, CSAs are not privy to these trainings. The same is true of updates and bulletins from the Jail Intelligence Unit, which possesses specialized knowledge on drugs and new mechanisms of smuggling them into correctional facilities. Mail Room CSAs are directly impacted by these areas, and should be allowed to attend these trainings and receive the Jail Intelligence Unit’s notices. In addition to not receiving training or having documented guidelines on detecting contraband, Mail Room CSAs are also not directed on how to safely handle potentially harmful substances coming through the mail. Post orders do not even instruct CSAs to wear gloves before examining incoming items, and one staff member reported that they did not receive a directive from Department management to wear gloves until 2017. The Department’s lack of direction on handling potentially hazardous substances in inmate mail does not align with California regulations on employee safety. General Industry Safety Orders, enforced by the State’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health, state: “Employers shall select, provide and require employees to use appropriate hand protection when employee’s hands are exposed to hazards such as those from skin absorption of harmful substances.”17 The lack of guidance in appropriate handling of inmate mail has potential consequences on staff safety. Several drugs, such as Fentanyl, can have severe health impacts such as respiratory depression even through inadvertent exposure. In Allen County, Indiana, 34 employees were treated for potential exposure to this substance, which the Sheriff’s Department asserted was likely smuggled through inmate mail.18 On this matter, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the following: “Responders who perform jobs where fentanyl or its analogues are reasonably anticipated to be present should receive special training in conducting an on-scene risk assessment related to fentanyl and its analogues and demonstrate an understanding of the following: • • • • • How to recognize the form and determine the quantity of the suspected fentanyl and other drugs. When to use PPE [personal protective equipment]; what PPE is necessary; how to properly put on, use, take off, properly dispose of, and maintain PPE; and the limitations of PPE. What the potential exposure routes are for fentanyl and its analogues. How to recognize the signs and symptoms of opioid exposure. When and how to seek medical help.”19 17 8 CCR § 3384. Retrieved from https://www.dir.ca.gov/title8/3384.html. 18 LeBlanc, Matthew. (21 Nov., 2017). Sheriff: Fentanyl believed to have sickened jail workers. The Journal Gazette. Retrieved from http://www.journalgazette.net/news/local/police-fire/20171121/ sheriff-inmates-could-face-charges-in-jail-opioid-incident. 19 The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2017). Preventing Occupational Exposure to Emergency Responders. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/fentanyl/risk.html. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -32- Section 4: Detecting Contraband in Inmate Mail Law enforcement officers are included in this category of “responders”, and while CSAs perform different functions, Mail Room CSAs are in a correctional context where they may be exposed to Fentanyl or other substances that bear similar health risks. Given these risks and CDC’s recommendations, staff should receive more substantive guidance on how to take appropriate precautions in the event that dangerous contraband is present in mail items. Defining these guidelines in writing will also reduce the probability of staff filing worker’s compensation claims stemming from exposure to these substances. CONCLUSION Inmate mail is a relatively common way of smuggling contraband into correctional facilities, and the Department should have robust controls for detecting substances that could impact the safety of inmates and jail staff. While the Department already takes some precautions, such as having a list of prohibited mail items, CSAs responsible for searching inmate mail do not receive specialized training or written procedures for detecting contraband in inmate mail. Further, Mail Room CSAs similarly lack direction on how to safely handle mail that may be laced with dangerous substances. In order to reduce the likelihood of inmate and staff health issues that can stem from undetected mail contraband, and the financial consequences that can result, the Department should ensure that its CSAs receive more substantive training and procedures on mail-smuggled contraband. RECOMMENDATIONS The Department of Correction should: 4.1 Require Custody Support Assistants to attend Sheriff Deputy Academy trainings on contraband, evidence, and the screening and distribution of mail. (Priority 3) 4.2 Copy Custody Support Assistants on portions of the Sheriff’s Jail Intelligence Unit’s pertaining to drug updates. (Priority 3) 4.3 Revise Mail Room policies and post orders to include safety protocols such as gloves for Custody Support Assistants. (Priority 3) SAVINGS, BENEFITS, AND COSTS Implementing Recommendation 4.1 would require no additional personnel or programming due to these trainings being established courses. Recommendation 4.2 would require no additional staff resources, as CSAs would simply be copied on portions of existing bulletins. And while Recommendation 4.3 would take some additional staff time and resources, it would not be enough to warrant additional staff. These recommendations will build a stronger knowledge base and skill set around mail-smuggled contraband for Mail Room CSAs, reducing the risk of drugs entering into County jail facilities through this avenue. This will increase both inmate and staff safety, and potential savings include avoided Custody Health costs used to treat cases of drug overdose, litigation costs in the event an inmate dies of an overdose, and staff worker’s compensation claims stemming from possible exposure to contraband. Further, implementing these recommendations will also better ensure compliance with California regulations on employee safety. -33- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Section 5: Payments to Inmates from Undisclosed Sources Section 5: Payments to Inmates from Undisclosed Sources Background The Sheriff assigns accounts to individual inmates, and money in these accounts may be used to buy commissary products, such as hygiene items and snacks. The Sheriff contracts with a private vendor, Aramark Correctional Services, LLC (Aramark), which subcontracts with TouchPay Payment Systems (TouchPay), to create and maintain these accounts. There are several ways for family and friends to deposit money into inmate accounts, including online, telephone, cashiering lobby kiosks, and mailing a money order or cashier’s check. The accounts are established electronically and all account transactions are recorded electronically. Problem, Cause, and Adverse Effect In 2015, dozens of local individuals in the bail industry were arrested and many were convicted of paying County inmates through these accounts. Inmates were paid to “direct” other inmates in the County jail to certain bail companies. Despite this history, neither DOC nor Sheriff’s Office policy prohibits this practice today. Bail bondsmen or others – including County correctional staff, other inmates or gang members – could give money to County inmates. In the course of this audit, we asked for records showing the amounts and identities of individuals who have given money to inmates, but the Sheriff’s Office prohibited release of this information. (We note that State law prohibits State prison staff from giving money to inmates in State prisons, but this law is not applicable to County jail facilities.) We contacted Aramark in an attempt to obtain deposit records, but received no response, despite a clear clause in the contract providing the County with the right to this data. To the extent that businesses, County correctional staff, other inmates, gang members or others with their own interests give money to inmates, this may create serious security risks for County correctional staff, inmates and the public. Recommendations The Board of Supervisors should require the DOC Chief to develop and implement a policy prohibiting any DOC or Sheriff’s Office staff from putting money into an inmate’s account. A DOC employee should regularly monitor all deposits into inmate money accounts for adherence to the policy, and those records should adhere to the County’s record keeping policies. Additionally, the DOC employee should analyze all deposits, by depositor, for suspicious activity, on a biannual basis. Any suspicious patterns should be investigated further and if any potential criminal activities are suspected those should be reported to the District Attorney’s Office. Savings, Benefits, and Costs Implementing these recommendations would enable the Department to avoid potential safety and security issues and related litigation costs by eliminating the opportunity for parties with their own interests to give money to inmates. There would be no material additional cost to the Department provided that it assigns an existing DOC employee to monitor the money accounts for policy violations. -35- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 5: Payments to Inmates from Undisclosed Sources FINDING In 2015, numerous individuals were arrested on suspicion of, and many were later convicted of, paying County inmates to ensure that other inmates only did business with certain local bail bond firms. Three years later, neither the DOC nor the Sheriff’s Office had placed any restrictions on who could pay a County inmate through a DOC-issued account. We asked the DOC for a list of deposits to inmate accounts by depositor for this audit. At about the same time, a news article was published that implied that County correctional staff had used these same DOC accounts to buy sexual or other favors from inmates. The Sheriff’s Office sent a memo to us dated July 26, 2018, in which it refused to provide the list of deposits. In its letter, the Sheriff’s Office referred to the news article, and disclosed that it had conducted a criminal investigation into the topic of the article. Despite criminal convictions and criminal investigations into the improper use of these accounts, there was still no DOC or Sheriff’s Office policy, or County Ordinance Code section, restricting payments to inmates to those provided by friends and family. The contract with Aramark included a clause allowing the County access to and the right to audit the data Aramark collected. We contacted Aramark several times in an effort to invoke this clause but received no response from this vendor. The fact that neither the account vendor, nor DOC officials, will disclose who has paid how much to which inmates, and there is no prohibition against staff or others paying County inmates, creates significant risks for inmates, County staff and the public. Anti-Fraternization Fraternization of all forms between correctional staff and inmates in other jurisdictions has led to many well-documented problems.20 These problems can “undermine the legitimacy of the officers’ professional expectations and include the physical or sexual abuse of inmates, bringing contraband into the prison, ignoring minor inmate violations, or ignoring inmates altogether.”21 As such, “correctional authorities have created and implemented anti-fraternization policies to regulate relations between correctional staff and inmates, both within and outside the correctional environment. These policies prohibit employees from engaging in relationships, romantic, financial, or otherwise, with current or former inmates and their families.”22 Attachment E on page 75 of this audit is a list of other jurisdictions with an anti-fraternization policy. 20 Blackburn, A.G., Fowler, S.K. , Mullings, J.L., & Marquart, J.W. “When Boundaries are Broken: Inmate Perceptions of Correctional Staff Boundary Violations”, Deviant Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2011. 21 Ibid. 22 Smith, B. V. & Loomis, M.C. “Anti-Fraternization Policies and their Utility in Preventing Staff Sexual Abuse in Custody”. American University, Washington College of Law, 2013. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -36- Section 5: Payments to Inmates from Undisclosed Sources Access to Inmate Money Account Records Denied Despite the risks associated with allowing anyone to pay inmates through accounts the County establishes, the Sheriff’s Office on behalf of the DOC refused to give the Management Audit Division access to any records of deposits into inmate money accounts. The Sheriff’s Office stated that it had already done an investigation into the money accounts and did not feel the Management Audit Division had any justification to follow up with our own audit of the records. Attachment F on page 77 is the Sheriff’s written response, in its entirety, to us. Once the Sheriff’s Office denied us access to the records, we sent a written request to Aramark’s Vice President (VP) of Finance on August 20, 2018, requesting the records of inmate money accounts. Attachment G on page 79 is our written request to Aramark’s VP of Finance for records. We called repeatedly to follow-up on our request but did not receive any return calls or information, despite the fact that there is a provision in the Aramark contract with the County that allows us to access those records for audit purposes. CONCLUSION The State of California has a law that prohibits correctional staff from giving money to inmates in State prisons, as do many other jurisdictions. Yet, in the County of Santa Clara, anyone can use a County-established account to pay an inmate. The Sheriff’s Office reports that it has conducted at least one criminal investigation into allegations that the County’s own correctional staff have paid inmates. Numerous bail bonds workers were convicted of paying inmates through these accounts in 2015. Allowing inmates to be paid by anyone, without regular monitoring for potentially illegal activity, increases the risk that inmates may harm each other, and increases the risk to correctional staff. It also increases the risk of an inmate escape, and thus may endanger the public. Given the risks associated with third parties paying inmates, and the Sheriff’s lack of transparency with respect to inmate money accounts, we recommend establishing controls and transparency over these payments. RECOMMENDATIONS The Department of Correction should: 5.1 Prevent fraternization between County inmates and correctional staff, immediately enact a policy that explicitly prohibits any DOC or Sheriff’s Office staff member from giving money to inmates through any means. (Priority 1) 5.2 Assign an existing DOC employee to regularly monitor and analyze all deposits into inmate money accounts for adherence to the policy and for suspicious patterns, that may be indicators of illegal activity. Report any findings of potential illegal activity conducted through the money accounts to the District Attorney’s Office. (Priority 1) -37- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 5: Payments to Inmates from Undisclosed Sources SAVINGS, BENEFITS, AND COSTS Implementing these recommendations would enable the Department to avoid potential safety and security issues and related litigation costs by eliminating the opportunity for correctional staff to give money to inmates and by monitoring the use of the money accounts as facilitation devices of illegal activity. There would be no additional cost to the Department provided that it assigns an existing DOC employee to monitor the money accounts for policy violations. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -38- Section 6: Lost Inmate Property Section 6: Lost Inmate Property Background The tracking, storage, and management of inmate property—including handling of lost inmate property—are functions of staff funded from the Department of Correction’s (DOC) budget. Civilian Custody Support Assistants (CSAs) examine lost property complaints and oversee the inmate property lost-and-found. If lost property cannot be located, CSAs also process lost property claims for reimbursement. According to Department records, claims payouts during calendar years 2017 and 2018 did not exceed $300 in either year, although these records may be incomplete due to poor claims tracking practices described herein. Problem, Cause, and Adverse Effect The DOC does not have a training or any other mechanism for informing inmates on how to submit claims, which raises the risk of inmates under-utilizing this process. Further, repeated reassignment of staff from the claims post during understaffed periods have resulted in poor claim tracking practices. Data entry issues such as blank property descriptions and discrepancies in how resolved versus pending claims are color-coded render questionable the DOC’s ability to review and address tracked claims in any systematic fashion. The DOC also does not generate summary reports for Sheriff’s Office administrators on lost items/paid claims, impeding the Department’s ability to analyze trends and implement measures to better prevent losses. Lastly, lost property claims are denied if an inmate signed for their property upon release; however, existing policies do not explicitly instruct releasing officers to tell inmates to look through all their property before signing the form. As such, inmates may sign the form without looking through their items, unaware that their signature precludes approval of lost property claims filed later. These issues all impact the ability of inmates to be compensated for property losses, which may be material for inmates who have limited personal assets. Recommendations The DOC should add the claims process to the Inmate Rulebook and make the claim form available in all housing units. The DOC should also add and fill one full-time equivalent (FTE) Office Specialist II to clean and manage the claim tracking logs at both Main Jail and Elmwood Correctional Facility, and to generate quarterly claims summary reports for Sheriff’s Office Administration. Finally, the DOC should expressly mandate in their written policies that releasing officers should instruct inmates to review all property before signing the release form, inmates should check off whether or not they have received each item they were booked with, and releasing officers should offer the claim form to inmates upon release. Savings, Benefits, and Costs Revising the Inmate Rulebook and the policy for releasing officers will not have any fiscal impact upon the DOC; however, adding one new Office Specialist II FTE for claims tracking will cost approximately $99,000 annually. This new position will also help generate the recommended quarterly claim summary reports. Implementing these recommendations will better allow inmates to be appropriately compensated for lost property, and provide additional oversight around property losses and the claims process. -39- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 6: Lost Inmate Property FINDING Inmate property is a function funded through the Department of Correction’s (DOC) budget.23 Civilian Custody Support Assistants (CSAs) assigned to this function are responsible for managing inmate property. For incoming inmates, CSAs enter property listed on an inmate’s pre-booking sheet into the DOC’s Inmate Personal Fund money/property-management system (IPF system); bag and label the inmate’s personal property and clothing; and store these items by Personal File Number (PFN) in designated storage areas. When inmates are released, the CSAs “release” the inmate’s property in the IPF system and collect all clothing and property belonging to the inmate. The releasing officer then gives these items to the inmate, and the inmate signs the back of their pre-booking sheet to acknowledge they have received their property. CSAs also handle lost property complaints by inmates. The CSAs oversee a lost and found, where these items are sometimes located. If an item cannot be found, inmates may submit a claim for reimbursement of their lost property. Before CSAs process these claims, they conduct final searches of the booking areas, property rooms, and the lost and found. They also check the inmate’s pre-booking sheet to verify that the inmate was, in fact, booked with the lost item. If all searches turn up negative and the inmate was booked with the item, then a CSA assigned to the property room opens a lost property claim. Effective July 2017, CSAs submit lost property claims to the Risk Management Department for payment. Risk Management staff advised us that they had not paid any claims to inmates since July 2017. Tracking logs maintained by CSAs show payouts during calendar years 2017 and 2018, although these records may be incomplete due to the Department’s poor claims tracking practices described below. These payouts did not exceed $300 in either year. No Central Mechanism to Inform Inmates of Claims Process There is no training or any other centralized mechanism for informing inmates on how to submit claims. CSAs reported that inmates largely learn about the claims process once their property is lost. For instance, CSAs may instruct inmates to submit a claim form as a response to a lost property grievance. However, this one-off, decentralized method of making inmates aware of the claims processes raises the risk that inmates will remain unaware of this option. A CSA or Sheriff Deputy might neglect to tell inmates about the claims process or fail to provide a copy of the form. In such a case, an inmate would have no way of knowing that they may submit a claim. This lack of awareness, in turn, prevents inmates from being appropriately compensated for their lost property. The Inmate Rulebook, which was last revised in July of 2018, only discusses submitting a general Inmate Request Form for instances of lost property, but does not cover claims in particular. The DOC should add a description of the claims process to the Inmate Rulebook, so that inmates have a readily available source to learn about lost property reimbursements. Copies of claim forms should also be placed in every housing unit, similar to grievance forms, so that inmates have visible and ready access. 23 All references to DOC or the Department hereafter refers to staff funded out of the DOC budget, even if the function falls under the legal jurisdiction of the Sheriff’s Office. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -40- Section 6: Lost Inmate Property Poor Claims Tracking Practices and No Reporting to Department Administration The claims post for CSAs is consistently deprioritized: there is only one post for claims at Main Jail, and nobody officially staffed on the claims post at the Elmwood facility. The DOC reported that whenever the functions generally staffed by CSAs are shorthanded, CSAs get pulled off the claims post first in order to fill needs elsewhere. This lack of attention to inmate claims has resulted in poor claims tracking with incomplete and inconsistent data entry. The DOC furnished the Management Audit Division with claims logs from both facilities. Main Jail has 22 claims in its 2018 log, and 96 claims in its 2017 log. We only received the 2018 log from Elmwood, which contains 81 claims.24 In logs for both facilities, it is difficult to discern which claims are closed and which are still pending, raising questions around the DOC’s ability to accurately track and process claims. Claims are not accompanied by a tracking number, and there is no data field that clearly denotes whether a claim has been resolved. Closed claims are supposed to be highlighted in a different color (orange in the Main Jail log and red in the Elmwood log), but there are multiple claims in both logs that have been seemingly resolved but not highlighted. For example, in the 2018 Main Jail log, there are three entries for which the property was found and a letter was sent to the inmate notifying them of the found item; however, these line items are not highlighted. Additionally, the 2018 Elmwood log contains 38 entries with dates ranging from November of 2014 to December of 2016. While a subset of these items may be backlogged claims (outstanding claims are transferred from one year to the next), the DOC reported that several claims had been erroneously inputted into the 2018 log by a new CSA. In addition, there is not enough staff to help clean the log. Between the inconsistent color-coding schemes and outdated claims that have accidentally been entered into current claims logs, the DOC does not track claims in a manner that is conducive to systematic review and processing. Missing or inconsistently entered information for line items further diminishes the utility of the claims logs. For instance, seven entries in the 2018 Elmwood log are missing descriptions of the lost property, and four of these seven items also have blank “Date of Claim” fields. In the 2017 Main Jail log, 21 of 25 entries (84 percent) associated with “found” items do not have dates inputted for when a letter was sent to the inmate notifying them that their property had been located. In the same log, 26 of 63 denied claims (41 percent) do not have explanations for why the claim was denied. These data entry gaps make it difficult to ascertain the nature of these claims and CSAs’ progress in processing them. Poor claims tracking practices also make it impossible for the Department to generate any sort of meaningful summary reports around metrics such as the number of claims filed, processed, paid, and denied, as well as trends around property losses. Indeed, CSAs do not report on claims to either DOC or Sheriff administration or any other parties outside the unit itself. This lack of reporting and oversight impedes the County’s ability to analyze trends and implement measures to better prevent inmate property losses and payouts. 24 The 2018 Elmwood log contains 257 items total. However, the Department reported that Elmwood also tracks lost and found items in this spreadsheet, and that claims can be distinguished from these lost and found entries by line items that have claim dates. In total, there are 81 entries with claim submission dates. -41- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 6: Lost Inmate Property As an example, DOC staff reported that items are often lost when inmates change housing units. Sheriff Deputies operating in the jails do not always wait to collect the inmate’s property before transporting the inmate, and so the inmate’s items remain at their original housing location. In several of these cases, inmate workers then discard the cell property that has been left behind, mistaking these bags for garbage. CSAs learn of these occurrences while reviewing claims, and including these descriptions in reports to DOC administration could result in adjusted policies, procedures, and trainings that prevent these instances of lost property from occurring in the future. Given the staffing issues around the claims post, the DOC should add and fill one new full-time equivalent (FTE) Office Specialist II position to help process claims and clean up the tracking logs at both jail facilities. Because processing claims is not a specialized function that requires extensive knowledge of correctional facilities, this role could be fulfilled by clerical staff with data entry skills. The ongoing cost of this position will be approximately $99,000 annually. Improving claims tracking would better ensure that inmate claims are being addressed in a consistent, systematic manner, and also facilitate reporting. With these improved claims logs, staff working on inmate claims should generate quarterly summary claims reports for DOC administration to review trends and identify areas of improvement that could help reduce the number of lost property complaints and filed claims. Denied Claims for Inmate Property Signed for Upon Release The claims logs—while incomplete—list “inmate signed for all property upon release” multiple times as a reason for claim denial. Departmental Policy 11.31 on Inmate Release states that, “The Release Officer will open the property bag and retrieve the green property release form and present the property to the inmate.” This officer must then ensure that the inmate signs the back of a copy of their pre-booking sheet acknowledging that they have received all their property (see Figure 6.1 below) Figure 6.1: Inmate Property Receipt Acknowledgment Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -42- Section 6: Lost Inmate Property It is then logical that CSAs processing claims would deny a claim if an inmate acknowledged, in writing, that he or she received their property upon release. In addition, Departmental Policy 11.37 on Inmate Property details the following procedure for handling inmate property at release: “If at the time of release, an inmate claims they are missing items of clothing or property, the Release Officer or Information Desk Officer/ CSA will: 1. Using the green Pre-Booking Information Sheet, verify that the missing property was received at the time of booking. 2. Contact the property room CSA, who will double-check all clothing and property storage areas for the inmate’s property. 3. Contact each facility and request a search for the inmate’s property.” These two policies imply that releasing officers would instruct inmates to look through their belongings, compare the items in their property bag to their green prebooking sheet, and notify them if anything is missing. However, this guidance is not explicitly outlined in either policy. In comparison, when discussing inmate property being released to designated parties besides the inmate, Departmental Policy 11.37 states, “After signing the property release, the person to whom the property is being released will open the inmate’s property bag and inventory its contents in front of the Information Desk Officer/CSA.” Based on the lack of explicit instructions to releasing officers, our observations and departmental anecdotes, it appears that releasing officers are not sufficiently instructing inmates to look through their belongings before inmates sign the release form. The DOC reported that inmates are required to sign this paperwork before leaving the facility regardless of any missing items. As such, inmates might sign the form as a matter of course without realizing that their signature precludes approval of lost property claims filed later. On a site visit of the Elmwood facility, the Management Audit Division observed a newly released inmate running back inside the facility’s lobby to report that they never received their property. This incident raises questions around whether inmates are aware of what exactly they are acknowledging when they sign the back of their pre-booking sheets. Without explicit instructions to releasing officers that they should instruct inmates to look through all their belongings prior to leaving the facility, there is a risk that inmates will sign the release form without actually confirming they have received all their items. DOC staff reported one case in which an inmate claimed that the releasing officer told her not to open her property bag until she was outside the facility gate. Consequently, by following these instructions, the inmate did not notice that she was missing a pair of earrings until after she had already signed the form and left the compound. Revising the DOC Policy Manual to expressly require releasing officers to instruct inmates to look through their property before signing the form would prevent cases like the one described above. -43- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 6: Lost Inmate Property Further, there is currently no avenue for an inmate to document, in writing, whether they are missing items from their property and clothing bags upon release. Inmates are expected to tell the releasing officer when they are missing property, and the releasing officer is supposed to contact the Property Room CSA to inform them of those lost items. However, if a releasing officer fails to communicate to the CSA that the soon-to-be-released inmate is missing items from his/her bag, no written record of this fact exists. To address this lack of documentation, the DOC should have inmates check off—in a different color—every item on their pre-booking sheet that they receive upon release. If there is no check next to the item, and the inmate files a claim later, the DOC should conduct a search for this property and process the claim even if the inmate has signed the acknowledgment form (see Figure 6.2 below for proposed documentation). The releasing officer should also offer claim forms to inmates upon their release, to facilitate speedier processing. Figure 6.2: Proposed Documentation of Missing Inmate Property The DOC should revise its release and property policies to include this modified process. Revising the process and policy in such a manner will create a more accurate representation of what the inmate did and did not possess upon release, and reduce instances in which a claim is inappropriately denied because the inmate was required to sign the acknowledgment form for release. CONCLUSION The DOC in collaboration with the Sheriff’s Office is responsible for tracking, storing, and managing inmate property, including investigating complaints of lost property. However, there is no centralized mechanism for instructing inmates on how to submit lost property claims, and claims tracking is inconsistent and incomplete due to repeated deprioritization of the claims post. This raises the risk of claims not being submitted at all due to a lack of awareness, or claims not being adequately addressed even when they have been submitted. Further, there is no reporting or oversight of the claims process, which prevents the DOC from analyzing ways in which it can reduce lost property incidents and claim payouts. Finally, the DOC denies claims when inmates have signed for their property upon release, but there are no accompanying policies to ensure inmates look through their bags and document missing items before signing the property release form. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -44- Section 6: Lost Inmate Property RECOMMENDATIONS The County of Santa Clara Department of Correction should: 6.1 Add the claims process to the Inmate Rulebook and make the claim form available in all housing units. (Priority 2) 6.2 Add and fill one full-time Office Specialist II to assist with processing and tracking claims at the County’s jail facilities. (Priority 2) 6.3 Prepare quarterly reports with claims summary statistics for Department administration to track the volume of inmate lost property, analyze any trends, and develop policies and practices that will reduce the amount of lost property. (Priority 3) 6.4 Revise its Policy Manual to explicitly state that releasing officers must instruct inmates to look through all property, physically inventory the items on their pre-booking sheet, document any missing items before signing the property release acknowledgment, and offer a claim form to released inmates. (Priority 3) SAVINGS, BENEFITS, AND COSTS Implementing Recommendations 6.1 and 6.4 will not have any fiscal impact upon the DOC. However, implementing Recommendation 6.2 - adding one clerical position - will cost approximately $99,000 annually. The new position could also help to generate the recommended quarterly claim summary reports, so there will not be additional costs associated with implementation of Recommendation 6.3. Implementing all of these recommendations will better allow inmates to be appropriately compensated for lost property. Revising the Inmate Rulebook will facilitate inmates becoming more aware of the claims process as an option for when their property is lost. Hiring additional staff will improve processing and tracking of claims, and help ensure that these claims are being addressed in a systematic, consistent fashion. Quarterly reporting will provide additional oversight around property losses and the claims process, and altering policies and procedures around inmate release will give inmates more opportunity to identify missing property before they sign the property release acknowledgment form. -45- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Section 7: Building a Better Vocational Training Program Section 7: Building a Better Vocational Training Program Background Pursuant to State (Title 15) Regulations, the County of Santa Clara has contracted with the Milpitas Unified School District (MUSD) since 1986 for the provision of Adult Education classes to inmates. This includes an Industries Program that provides inmates with vocational training in cabinet making, upholstery and welding. Problem, Cause, and Adverse Effect Although MUSD is not contractually obligated to provide instructors to the Industries program, it has historically done so; but since October 2016, the MUSD has been without instructors to teach inmates the skills necessary to confer degrees of aptitude (Certificates of Learning). Moreover, according to DOC staff, even when instructors were conferring them, Certificates of Learning were not industry-recognized credentials and therefore, were only minimally beneficial to inmates seeking postrelease employment. The Industries program continues to operate; but without instructors, it is no longer able to confer Certificates of Learning or produce and sell the same volume of goods and services to other County departments and nonprofits as it did previously. Consequently, sales revenue is down, but more importantly, the DOC has been missing out on an opportunity to reduce recidivism as research shows inmates with vocational training are less likely to recidivate and are more likely to find a job after release than their peers with no such training. Recommendations Since the Industries program has been without instructors for about three years, and the certificates earned in the program are only minimally beneficial to inmates seeking post-release employment, the DOC should contract with a different vendor to establish a one-year pilot vocational training program that ultimately bestows a more valuable, portable credential to inmates. Alternately, the DOC could establish a one-year pilot Registered Apprenticeship (RA) program to provide inmates with vocational training, and upon completion, a industry-recognized credential from the U.S. Department of Labor. Savings, Benefits, and Costs Implementing either recommendation would have fiscal impact upon the DOC, which is partly funded by the County’s General Fund. The size of that impact depends largely on whether the DOC creates the pilot program or contracts it out, as well as on the specific number of program participants. That impact is likely to be offset by increased sales revenue, and avoided re-incarceration costs as inmates who earn an industry recognized credential are more likely to find a job after release and are less likely to recidivate. -47- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 7: Building a Better Vocational Training Program FINDING The purpose of the County of Santa Clara Correctional Industries program is to train inmates “to work while providing high quality products and services to government and non­profit organizations...”25 Both of these goals have been hampered since October 2016 by the lack of MUSD instructors in the program. History of Instructors MUSD’s welding instructor separated from the program in June 2016. The remaining instructor who taught both cabinet making and upholstery separated from the program in October 2016. Since that time the program has been without instructors to teach cabinet making, upholstery and welding. According to MUSD, it has tried repeatedly to hire instructors for the program but all applicants to date have failed to meet its employment standards. Program Revenues and Costs Program costs are primarily personnel costs associated with Custody Support Assistants helping inmates to operate tools and equipment and Sheriff Deputies supervising inmates at work. These costs are offset by Public Safety Realignment (AB109) funds and the proceeds from the sale of the program’s goods and services. Even without instructors, the Industries program continues to produce items for sale, but at a reduced volume. As shown in Figure 7.1 below, sales revenue has been decreasing since FY 2015-16. Consequently, the net costs of the program have been higher in every year since FY 2015-16. Figure 7.1: Annual Program Revenues & Costs Fiscal Year Gross Costs AB109 Funds Sales Revenue Net Costs 2015-16 $841,903 ($422,717) ($261,187) $157,999 2016-17 $962,521 ($458,762) ($194,472) $309,287 2017-18 $908,650 ($495,882) ($149,608) $263,160 2018-19 $232,124 $189,804* ($147,708) $274,220 Source: Office of the Sheriff Administrative Division. * This represents a cost transfer to align AB109 funding with appropriate cost centers, according to the Administrative Division. 25 County of Santa Clara, Department of Corrections, Industry web page, published: 6/19/2014, retrieved on 7/26/2018 from https://www.sccgov.org/sites/doc/inmates/Pages/industries.aspx. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -48- Section 7: Building a Better Vocational Training Program MUSD Contract The County’s current agreement with Milpitas Unified School District relating to providing Adult Education classes to inmates is in an amount not to exceed $170,000 for the five-year period from July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2021. This is equates to $34,000 each fiscal year. Under this agreement, MUSD agrees to maintain an educational program for inmates which may, but is not required to, include a number of different components. One of these components is “[s]hort-term vocational programs with high employment potential”.26 The agreement does not address how many instructors (if any) will be provided to the Industries program. Therefore, MUSD is technically in compliance with the agreement, despite not providing any instructors to the program for the last three years. Vocational Training for Inmates Certificates of Learning When MUSD provided instructors to the Correctional Industries program, they were certified with a Career Technical Education (CTE) teaching credential. This allowed them to confer degrees of aptitude (Certificates of Learning) in the field of instruction. However, these certificates were not standardized and did not connote a known degree of aptitude. Their utility, therefore, was limited as it related to a potential employer’s understanding of the skill level a certificate holder has. The welding certificate explicitly states that the class participants “will demonstrate the skills and knowledge necessary to pass the American Welding Society (AWS) Certification Test.” While passing the AWS Certification Test is not required to get a job as a welder27 such a certification and its formal requirements are “transferable”28 and may make getting a job in the field more likely. The research literature on incustody apprenticeships shows that inmates with vocational training are less likely to recidivate and are more likely to find a job after release than their peers with no such training.29; 30 However, it is up to the inmates to pass the test and become certified once they are released. 26 MAE contract. 27 Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, Welders, Cutters, Soldiers, and Brazers, on the Internet at https://www.bls.gov/ooh/production/welderscutters-solderers-and-brazers.htm (visited August 07, 2018). 28 “Transferable” means that the skills learned to pass the test can be transferred from one job to another. This is because the successful test taker has performed satisfactorily to a standard that has national and international acceptance. 29 “Educational and Vocational Training in Prisons Reduces Recidivism, Improves Job Outlook”, Press Release (2013), the RAND Corporation. 30 “Nearly Half of Prisoners Lack Access to Vocational Training: Without These Opportunities, the Rate of Recidivism is Significantly Higher”, Huffington Post, March 10, 2017, Updated March 13, 2017. -49- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division Section 7: Building a Better Vocational Training Program A certificate in upholstery demonstrates similar basic skills in the trade but does not appear to lead to a transferable credential.31 An inmate who earns a certificate in cabinet making is able to understand the defining principles of “wood and allied materials, wood working equipment, and wood fabrication.” However, the certificate does not explicitly state that it will prepare the inmate who earns it to obtain one or more of “the five progressive credentials” in woodworking offered by the Woodwork Career Alliance of North America, for example. Registered Apprenticeships During fieldwork for this audit section, we learned that the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) administers the Registered Apprenticeship Program (RAP) to assist employers, also known as “sponsors”, to start and register an apprenticeship program. In its publication “A Quick-Start Toolkit: Building Registered Apprenticeship Programs” DOL details the steps and resources available to design a customized apprenticeship program. The apprenticeship program components include paid work, work-based learning, mentorship, educational and instructional component, and industryrecognized credential. The Management Audit Division reviewed the National Apprenticeship Act (1937) and its amendments (which enable RAP) with an eye for determining whether a sponsor can establish a program within a correctional facility, and found no prohibition against it. The following are other issues to consider. First, many apprenticeships take up to four years or more to complete. Given that AB 109 transferred the management of certain low-level offenders from the State to the county level, many inmates are now serving longer sentences locally and therefore, may have sufficient time in-custody to complete an apprenticeship. During its pilot of registered apprenticeships, DOC could use one or more of the national frameworks built by the Urban Institute (a nonprofit research organization) to fast-track the development of its apprenticeships. These frameworks are competency based rather than time based, meaning that abilities are emphasized over memorized knowledge and skills and are more important than the number of hours spent working on tasks. Finally, placing an apprenticeship program within a correctional facility is not entirely theoretical, there are such programs elsewhere in the country, and have shown some success.32 31 Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, Data for Occupations Not Covered in Detail, on the Internet at https://www.bls.gov/ooh/about/data-foroccupations-not-covered-in-detail.htm (visited August 02, 2018). 32 The Iowa and Indiana Department of Corrections have implemented these programs and the initial results are promising. From Source in Footnote 5. Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division -50- Section 7: Building a Better Vocational Training Program CONCLUSION The DOC’s Industries program is a valuable resource whose potential is not being fully realized. Since October 2016, there have been no instructors to teach inmates basic skills in cabinet making, upholstery and welding. While MUSD is not contractually obligated to provide instructors for the program, it has made efforts, albeit unsuccessful, to hire instructors. Nevertheless, the Certificates of Learning that inmates currently receive are less marketable than the industry recognized credential they would receive from an apprenticeship program. RECOMMENDATIONS The Department of Correction should: 7.1 Contract with a different vendor to establish a one-year pilot vocational training program that ultimately bestows a more valuable, portable credential to inmates. Alternately, the Department could establish a oneyear pilot registered apprenticeship program to provide inmates with vocational training, and upon completion, a industry-recognized credential from the U.S. Department of Labor. (Priority 1) SAVINGS, BENEFITS, AND COSTS Implementing either recommendation would have fiscal impact upon the DOC, which is partly funded by the County’s General Fund. The size of that impact depends largely on whether the DOC creates the pilot program or contracts it out, as well as on the specific number of program participants. That impact is likely to be offset by increased sales revenue, and avoided re-incarceration costs as inmates who earn an industry recognized credential are more likely to find a job after release and are less likely to recidivate. -51- Board of Supervisors Management Audit Division THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Attachments A-I -53- THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for 5.a Attachment A: MemorandumtoFGOC-LegallyPermissibleOptionsforJailStructure Packet Pg. 6 -55- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 7 -56- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 8 -57- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 9 -58- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 10 -59- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 11 -60- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 12 -61- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 13 -62- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 14 -63- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 15 -64- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 16 -65- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 17 -66- Attachment: County Counsel Memorandum regarding Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure (83368 : Legally Permissible Options for Attachment A: Memorandum to FGOC - Legally Permissible Options for Jail Structure 5.a Packet Pg. 18 -67- THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Attachment B: DOC List of Accomplishments Attachment B: DOC List of Accomplishments -69- Attachment B: DOC List of Accomplishments -70- Attachment C: Minute Order-Redacted and Revised Attachment C: Minute Order-Redacted and Revised -71- THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Attachment D: Minute Order-Redacted Attachment D: Minute Order-Redacted -73- THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Attachment E: Other Jurisdictions Attachment E: Other Jurisdictions Attachment 5.1 Sample List of Jurisdictions with Policies Prohibiting Fraternization between Correctional staff and Inmates States • California • Idaho • Indiana Counties • Contra Costa County, CA • Garfield County, CO • King County, WA • Los Angeles County, CA • Maricopa County, AZ -75- THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Attachment F: Request for TouchPay Data Attachment 5.2 Attachment F: Request for TouchPay Data County of Santa Clara Office of the Sheriff 55 West Younger Avenue San Jose, California 95110-1721 (408) 808-4900 Laurie Smith Sheriff July 26, 2018 To: Gabe Cabrera, Contract Senior Manager From: Juan Gallardo, Director of Sheriff’s Administrative Services Subject: Request for TouchPay Data On July 16, 2016 you requested “… data on all deposits for a given period of time showing names (i.e., depositors and inmates), dollar amounts, and dates” from inmate money account management services vendor TouchPay, Inc. On July 20, 2018 Fletcher Dobbs, PM II, on behalf of the Sheriff’s Office, responded that the Sheriff’s Office is unable to provide you with the data you requested. During telephone conversations which took place between the time of your request on July 16 and the Sheriff’s Office response on July 20, you explained that you were investigating information related to a number of recent press articles which describe text messaging between certain Sheriff’s Office staff, which included exchanges describing and questioning staff receiving favors from inmates in exchange for commissary items. Undersheriff Carl Neusel explained to you that immediately upon receiving allegations to which the article(s) allude, the Sheriff’s Office completed in depth criminal investigations into the allegations contained in the articles and that these investigations did not yield information which would support the allegations. Following the Sheriff’s Office message to you on July 20, you have inquired further about obtaining detailed TouchPay data related to deposits to inmate accounts. The Sheriff’s Office again asserts we are unable to provide you with the data you have requested and again inform you that detailed criminal investigations of these matters have been completed by the Sheriff’s Office. Thank you C: Carl Neusel, Undersheriff Rick Sung, Assistant Sheriff -77- THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Attachment 5.3 Attachment G: Request for Information to Aramark Attachment G: Request for Information to Aramark -79- THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Attachment H: County Executive's Response County of Santa Clara H: County Executive's Response Attachment Office of the County Executive County Government Center, East Wing 70 West Hedding Street, 11 th Floor San Jose, California 95110 (408) 299-5105 September 15, 2020 To: Gabe Cabrera, Contract Senior Manager Harvey M. Rose Associates, LLC From: Martha Wapenski, Deputy County Executive County of Santa Clara Re: Response to the Management Audit of the Department of Correction The Office of the County Executive has reviewed the Management Audit of the Department of Correction dated September 8, 2020 prepared by the Harvey M. Rose Accountancy Corporation. Our responses to the recommendations pertaining to the operations under the authority of County Executive and Interim Chief of Correction Jeffrey V. Smith are contained herein. We would like to thank the Harvey M. Rose staff for their consummate professionalism and effective communication throughout this audit. The recommendations and response pertaining to the operations under the authority of the Chief of Corrections are 1.1, 2.1, and 2.2. 1.1 Urge the Santa Clara County Superior Court to modify its minute order form in the manner described in this report section and as illustrated in attachment 1.2. Agree. The Office of the County Executive and the Office of the Sheriff are in agreement to meet with Superior Court representatives to discuss the audit details related to “reducing the risk of releasing inmates in error”, and explore the feasibility and possible steps needed to modify the minute order form. 2.1 Establish a policy to require an assessment of the physical condition of each kitchen and laundry asset. The condition assessment should occur annually, and the results of the assessment should be reported to the Chief of Correction. Board of Supervisors: Mike Wasserman, Cindy Chavez, Dave Cortese, Susan Ellenberg, S. Joseph Simitian County Executive: Jeffrey V. Smith -81- Attachment H: County Executive's Response September 15, 2020 –2– Page 2 of 3 Agree in concept. The Department of Correction agrees about the importance of conducting an annual (and more frequently) equipment assessment, and the need for an annual report to the Chief of Correction. While the recommendation calls for a policy, a procedural change to effectuate the recommendation has already been implemented, and is sufficient to provide the annual equipment assessment and subsequent report to the Chief of Correction. 2.2 Develop and maintain a five-year fixed assets plan and present the plan to the Board of Supervisors for approval annually. The plan may be a separate document but should be integrated into the Department’s annual budget. Agree in concept. The Department fully supports a multi-year fixed asset plan to replace kitchen and laundry equipment. Food Services began the development of the five-year fixed asset plan before the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated staff to re-focus on more immediate areas of the operation. As part of the implementation of this recommendation, the asset plan is on track for completion by the end of CY 2020. The department plans to continue the annual requests for replacement equipment as part of the annual budget process: • • • Food Services o In FY 19-20, as the management audit indicates, the Board approved $218,000 in onetime and $106,000 in ongoing funding for replacement equipment for Food Services. There was also $262,000 added in FY 16-17 for replacement equipment. o In FY 20-21, the Board approved $450,000 in replacement equipment for Food Services. Laundry o In FY 19-20, the Board approved $500,000 for the replacement of 3 industrial washers and 2 industrial dryers. In FY 15-16, the Board approved $712,000 for the replacement of 2 industrial washers and 2 industrial dryers. Equipment Repair o In the beginning of CY 2020, the department implemented a maintenance plan with an outside vendor to facilitate faster repairs and parts replacement to decrease the amount of downtime for the large meal preparation equipment. While the management audit recommendation calls for presenting a five-year fixed asset plan to the Board annually for approval, this memorandum provides an alternate approach that fits into the existing process for Board approval of equipment replacement purchases. When the equipment reaches end-of-life as indicated in the five-year fixed asset plan, the funding request would be provided to the County Executive as part of the -82- Attachment H: County Executive's Response September 15, 2020 –3– Page 3 of 3 annual budget submission process. Since budget submissions are provided to the Board for review, the equipment replacement requests would be included in that information. The funding approval process would then follow the same procedure as other budget submissions within the annual County Executive’s Recommended Budget. CC: Jeffrey V. Smith, County Executive Cheryl Solov, Contract Management Audit Manager -83- THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK Attachment I: Sheriff’s Response Attachment I: Sheriff’s Response County of Santa Clara Office of the Sheriff 55 West Younger Avenue San Jose, California 95110-1721 (408) 808-4400 _____________________________M E M O R A N D U M_____________________________ Laurie Smith Sheriff TO : Honorable Board of Supervisors FROM : Laurie Smith, Sheriff SUBJECT : DATE Management Audit of the Department of Corrections : September 18, 2020 ______________________________________________________________________________ I am in the receipt of the Management Audit of the County of Santa Clara Department of Corrections dated September 8, 2020, and I have reviewed the findings. The audit contains recommendations, which if adopted and appropriately funded by the County, would likely benefit the organization and the County as a whole. However, given the current fiscal crisis and structural budget deficit facing the County and our operations, as well as the competition for scarce resources to comply with the Consent Decrees, many of the recommendations in the audit are very low on any priority list for implementation. The responses to the recommendations were done in isolation of the audit and as such, agreement with a recommendation does not necessary indicate agreement with the auditor’s findings nor the reasoning or evidence used to support their recommendation. As mentioned above, many of the recommendations may be beneficial; however, I also have concerns regarding the costs and/or overhead associated with the recommendations. I do not believe in unnecessary bureaucracy in government, and I have serious concerns with expanding government operations beyond what is fiscally responsible or necessary for the effective operation of the office. This is particularly true in law enforcement, where we are required to provide a level of service regardless of the fiscal health of the economy. I am fully supportive of recommendations that improve the training, available technology, wellness, safety, and retention of Sheriff’s Office employees. I am equally supportive of recommendations that improve the day-to-day operations of the Sheriff’s Office and the critical services we provide. -85- AUDIT RECOMMENDATION -86- Agree – The Office of the Sheriff believes that this recommendation is already covered with the existing Inmate Rulebook and policy; however, we will reevaluate if additional clarity and training are appropriate. Agree – The Office of the Sheriff will review and evaluate how this recommendation could be implemented with existing staff and resources. The Office of the Sheriff is neutral on this recommendation and defers to the Office of the County Executive. The Office of the Sheriff is neutral on this recommendation and defers to the Office of the County Executive. Agree ‐ The Office of the County Executive and the Office of the Sheriff are in agreement to meet with Superior Court representatives to discuss the audit details related to “reducing the risk of releasing inmates in error”, and explore the feasibility and possible steps needed to modify the minute order form. RESPONSE Santa Clara County Office of the Sheriff – DOC Audit Response | Page 1 of 3 Notify inmates with a receipt explaining the reasons for any returned mail, regardless of whether it is 3.1 opened or unopened. Doing so would save the Department from answering grievances about reasons for withheld unopened mail. (Priority 3) Clarify what constitutes “inappropriate” mail and create more detailed guidelines on this matter to be added to internal policies, the Inmate Rulebook, and 3.2 publicly available lists of inmate mail rules. The CSA Supervisors should then conduct an annual training on these guidelines, with examples, to improve consistency in Mail Room practices. (Priority 3) Section 4. Detecting Contraband in Inmate Mail The Sheriff should: Section 3. Returned Inmate Mail The Sheriff should: 2.2 2.1 Establish a policy to require an assessment of the physical condition of each kitchen and laundry asset. The condition assessment should occur annually, and the results of the assessment should be reported to the Chief of Correction. (Priority 3) Develop and maintain a five‐year fixed assets plan and present the plan to the Board of Supervisors for approval annually. The plan may be a separate document, but should be integrated into the Department’s annual budget. (Priority 3) Section 2. Developing and Funding a Fixed Assets Plan The DOC should: 1.1 1.1 Urge the Santa Clara County Superior Court to modify its minute order form in the manner described in this report section and as illustrated in Attachment 1.2. (Priority 1) The Chief should: Section 1. Errant Inmate Release NO. Attachment I: Sheriff’s Response -87- 6.2 Agree – The Office of the Sheriff agrees that additional staffing could assist with processing and tracking claims. Agree – The Office of the Sheriff generally agrees with this recommendation and we are evaluating how to revise existing policy in coordination with County Counsel and Plaintiff’s Counsel for the Consent Decree. Agree ‐ The Office of the Sheriff supports this recommendation; however, the Office would require additional staffing to include a Detective Sergeant, Detective, and Crime Analyst, in order to proactively investigate and link inmate deposits and identify illegal or fraudulent activity. Sheriff’s Office Detectives are tasked with investigating such allegations and submit completed criminal investigations to the District Attorney’s Office for charging decisions. Agree ‐ The Office of the Sheriff has established policy prohibiting fraternization or the gift of money from any staff to an existing or former inmate, which we believe adequately covers this recommendation. Partially Agree – The Office of the Sheriff agrees with the recommendation and provides training currently; however, additional training can be realized without sending Custody Support Assistants to the academy for training. Partially Agree – Custody Support Assistants receive regular information on the latest safety precautions and appropriate handling and screening of substances pertaining to their job function. Agree – The Office of the Sheriff will review and evaluate if additional safety protocols are needed within established policy and post orders. Santa Clara County Office of the Sheriff – DOC Audit Response | Page 2 of 3 Add and fill one full‐time Office Specialist II to assist with processing and tracking claims at the County’s jail facilities. (Priority 2) Copy Custody Support Assistants on portions of the 4.2 Sheriff’s Jail Intelligence Unit’s pertaining to drug updates. (Priority 3) Revise Mail Room policies and post orders to include 4.3 safety protocols such as gloves for Custody Support Assistants. (Priority 3) Section 5. Payments to Inmates from Undisclosed Sources The Sheriff should: Prevent fraternization between County inmates and correctional staff, immediately enact a policy that 5.1 explicitly prohibits any DOC or Sheriff’s Office staff member from giving money to inmates through any means. (Priority 1) Assign an existing DOC employee to regularly monitor and analyze all deposits into inmate money accounts for adherence to the policy and for 5.2 suspicious patterns, that may be indicators of illegal activity. Report any findings of potential illegal activity conducted through the money accounts to the District Attorney’s Office. (Priority 1) Section 6. Lost Inmate Property The Sheriff should: Add the claims process to the Inmate Rulebook and make the claim form available in all housing units. 6.1 (Priority 2) 4.1 Require Custody Support Assistants to attend Sheriff Deputy Academy trainings on contraband, evidence, and the screening and distribution of mail. (Priority 3) Attachment I: Sheriff’s Response -88- Agree ‐ The Sheriff’s Office is currently working in collaboration with local community colleges to establish vocational programming where participants earn industry recognized certification or college credit that can transition to future employment opportunities. Partially Agree – The Office of the Sheriff generally agrees with this recommendation and we are evaluating how to revise existing policy in coordination with County Counsel and Plaintiff’s Counsel for the Consent Decree. Agree – The Office of the Sheriff tracks portions of this information today and the new Jail Management System will vastly improve and automate future reporting capabilities. Santa Clara County Office of the Sheriff – DOC Audit Response | Page 3 of 3 Prepare quarterly reports with claims summary statistics for Department administration to track the 6.3 volume of inmate lost property, analyze any trends, and develop policies and practices that will reduce the amount of lost property. (Priority 3) Revise its Policy Manual to explicitly state that releasing officers must instruct inmates to look through all property, physically inventory the items 6.4 on their pre‐booking sheet, document any missing items before signing the property release acknowledgment, and offer a claim form to released inmates. (Priority 3) Section 7. Building a Better Vocational Training Program The Sheriff should: Contract with a different vendor to establish a one‐ year pilot vocational training program that ultimately bestows a more valuable, portable credential to inmates. Alternately, the Department could establish 7.1 a one‐year pilot registered apprenticeship program to provide inmates with vocational training, and upon completion, an industry recognized credential from the U.S. Department of Labor (Priority 1). Attachment I: Sheriff’s Response Attachment J: Santa Clara County Superior Court’s Response Attachment J: Santa Clara County Superior Court’s Response -89- Attachment J: Santa Clara County Superior Court’s Response Dear Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors Corrections Audit team, the court respectfully disagrees with the recommendation that the Superior Court’s minute order templates be changed to add a checkbox at the top of the form, to be checked whenever the RELEASED box is checked at the bottom of the form, for the following reasons: 1) The minute order templates contain clear verbiage about COMMITTED and RELEASED in a font that is large enough to be easily seen, and with the orders spaced apart so as to be easily distinguished from each other. The nature of the Santa Clara County Department of Correction clerical error that precipitated this audit - not reading all of the orders on the minute order that paint the full picture of someone being committed to a term of incarceration rather than released- is not the kind of error that should warrant a change to the minute order templates. 2) The suggested change, to essentially re-state the same order, RELEASED, at the top of the minute order when checked at the bottom, would amount to the permanent addition of a checkmark that adds up to an enormous of ongoing extra work when one factors in making this change on every single minute order containing that order, which is usually numbered in the thousands of minute orders on an annual if not monthly basis. If the RELEASED box at the bottom of the minute order is checked, there should be no need to check the same box at the top of the minute order. If there was a requirement that a courtroom clerk check 2 boxes for the same thing, extra errors or confusion would result. -90- Attachment J: Santa Clara County Superior Court’s Response 3) The monetary costs associated with changing the templates, training staff, monitoring compliance with the change, and the above-noted human costs, are all important factors considering very serious budget and staffing concerns the court is facing due to the pandemic. The court appreciates the opportunity to respond, and remains committed to providing its justice partners with clear, concise, and easy to read orders. -91- THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK