International Mediation Effectiveness: Dispute Characteristics

advertisement

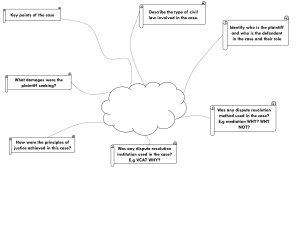

The Nature of the Dispute and the Effectiveness of International Mediation Author(s): Jacob Bercovitch and Jeffrey Langley Source: The Journal of Conflict Resolution , Dec., 1993, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Dec., 1993), pp. 670-691 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/174545 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Sage Publications, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Conflict Resolution This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Nature of the Dispute and the Effectiveness of International Mediation JACOB BERCOVITCH JEFFREY LANGLEY University of Canterbury The literature on mediation focuses largely on experimental laboratory studies or descrip tions of single cases. This article goes beyond such approaches by analyzing systematically h dispute characteristics affect mediation outcomes. A theoretical framework for studying m ation behavior is developed and its central variables are evaluated against the mediation patte of 97 international disputes in the postwar period. Using multivariate analysis and logline methods, the results indicate that dispute features such as fatalities, complexity, nature of issue, and duration of dispute are most predictive of mediation outcomes. The authors use th results to specify a causal model that explains the data and to consider how best to evaluate fit of alternative models of mediation to their data. M ediation is widely regarded as the most common form of third-part intervention in international disputes (Bercovitch 1984; Butterworth 197 Holsti 1987). It is a noncoercive and voluntary form of conflict manageme that is particularly suited to the reality of international relations, where sta and other actors guard their autonomy and independence quite jealousl Although mediation is becoming increasingly popular in all social contex there is still much about its performance and effectiveness that we do n understand. Clearly, mediation cannot be effective or successful in each a every dispute. Some disputes are amenable to mediation, but in others, t parties may have to use different means. In this article, we assess how t characteristics of a dispute affect the performance and effectiveness o international mediation. We do so by developing a mediation-events data AUTHORS' NOTE: This article was completed while the first author was the Lady Da Professor in International Relations at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. We are grateful to P Camevale, Allison Houston, Herb Kelman, Dean Pruitt, Pat Regan, and J. David Singer for t helpful comments. JOURNAL OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION, Vol. 37 No. 4, December 1993 670-691 ? 1993 Sage Publications, Inc. 670 This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Bercovitch, Langley /INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 671 and searching for a parsimonious, formal framework that can best interpret the relationship among the various factors we highlight. There is, to begin with, some disagreement on what precisely constitutes international mediation. Some studies (e.g., Northedge and Donelan 1971) define mediation rather narrowly. Narrow definitions of mediation are consistent with the attempt to capture the "essence" of mediation and to draw boundaries between mediation, conciliation, facilitation, good offices, shuttle diplomacy, and fact-finding. This seems a futile exercise. When intervening in an international dispute, a mediator may exhibit all or any combination of these behaviors. This is why we prefer to adopt a behavioral approach and define mediation broadly as "a process of conflict management where disputants seek the assistance of, or accept an offer of help from, an individ- ual, group, state or organization to settle their conflict or resolve their differences without resorting to physical force or invoking the authority of the law" (Bercovitch, Anagnoson, and Wille 1991, 8). Admittedly, this is a broad definition indeed, but we believe it to be a useful one because it draws attention to the basic components of mediation; namely, disputing parties, a mediator, and a specific conflict management context. A better understanding of international mediation can only come about from an approach that can analyze one or all of the salient variables and components that make up a mediation relationship. Undoubtedly, two of the most important components that make up this relationship are the nature and characteristics of the dispute. Whatever is meant by an international dispute, it is clear that some disputes can be mediated successfully, whereas others frustrate the efforts of many diverse mediators. We are mindful of the fact that we are focusing on a specific, albeit basic, component of mediation. We are nonetheless convinced that it would be interesting to examine, in a systematic fashion, the influence and impact that different disputes can have on the performance and effectiveness of international mediation. A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH This article must be seen as part of our efforts to place internat mediation within an empirical context and as a response to recent ca the analysis of mediation to employ more sophisticated multivariate niques (Bercovitch, Anagnoson, and Wille 1991). It makes use of an lished but recently expanded dataset (see Bercovitch 1986, 1989; Berco Anagnoson, and Wille 1991) to test the validity of earlier findi This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 672 JOURNAL OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION international mediation and to identify those dispute characteristics that the greatest impact on mediation outcomes. We present conceptually significant relationships and then use a loglinear model for multidimen analysis to ascertain the empirical validity of these relationships. Statistical analyses of mediation at the international level have been (Bercovitch 1986, 1989; Bercovitch, Anagnoson, and Wille 1991; Frei Holsti 1966; Levine 1971; Raymond and Kegley 1985). Of these, Raym and Kegley (1985) are the only scholars who have attempted a multiva analysis, but their findings relate only to the incidence of mediation r than to its effectiveness or outcomes. Here we take the pivotal aspec these works and place them within a conceptual framework that serves as basis for our inquiry and analysis. In searching for the antecedents of effective mediation, we note that m of the existing, and largely anecdotal or experimental, literature on int tional mediation places enormous emphasis on the mediator and his or attributes as the key to achieving a successful outcome (e.g., Brett, Dri and Shapiro 1986; Carnevale 1986; Young 1972). From this perspec mediation may often be regarded as an art or a skill that one possesse acquires. Successful mediation is thus presumed to be dependent on t efforts of gifted and able mediators. It is as if other factors cannot, or do impinge on a mediation relationship. The mediator is undoubtedly an im tant influence, but, we suggest, only one influence among others. We assume that mediation is an adaptive process; different mediator different things in different situations, and that its particular form i situation depends on who the parties are, what the dispute is all about who the mediator is. Figure 1, which we refer to as the contingency fr work of mediation, draws attention to four major clusters of indepen variables that determine mediation outcomes (cf. Wall and Lynn 1993) The contingency framework of mediation was developed by Bercovi Anagnoson, and Wille (1991). The framework builds on comparable (bu refined) models that can be found in Wall (1981) and Raymond and Ke (1985). In our framework, the outcome of mediation is assumed determined by both the context and the process of mediation. The contex any mediation may itself be divided into three clusters of variables: ( nature of the dispute, (b) the nature of the parties, and (c) the nature o mediator. The process dimension of the framework refers to actual me strategies and their impact on the outcome. The contingency framework is a useful analytical tool that can he scholars to organize the literature on mediation and practitioners to ev its policy implications. It also opens up before the researcher many ave This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Bercovitch, Langley/INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 673 Figure 1: A Contingency Model of Mediation of data collection and theory development. The particular avenue we will pursue here concerns the nature of the dispute in its many facets. DATA AND METHOD The first objective of this study was to build up a database on internat mediation. To this end, we have systematically scanned two major e data sources, Keesings Archives and the New York Times, since 1945 information on international disputes. In assembling our list of disput relied on the prior compilation of Small and Singer (1982), but lowere threshold of fatalities to 100 only. Thus we define an international dispu continuous clash between two or more states and involving at least 100 fat Our search yielded 97 international disputes from 1945-1990. For ea those disputes, we gathered information on opening and closing dates, is presence of allies or others, fatalities, and other contextual variables. O the most important variables we investigated concerned the means manner of dispute termination. Procedures of termination were divide violence, obsolescence, negotiation, mediation, and termination by reg or international organizations. We found that our 97 disputes had experie 364 separate mediation attempts (the real number of mediation attem much higher, but we could rely only on cases where mediation was rep to have taken place). Some disputes experienced no mediation at all, ot experienced one or two attempts, yet others experienced more than different mediation attempts. Those 364 mediation cases constitute our of analysis. This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 674 JOURNAL OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION TABLE 1 Mediation Outcomes Outcome N Valid % Offered only 76 Unsuccessful Cease fire 207 30 71.9 10.4 Partial settlement 34 11.8 Full settlement Total 364 17 5.9 100.0 Having identified o number of indicator mediators' status in t strategy in a and the used, etc.) to series of earlier Wille 1991; Berc conditions unde international predictive of inquiry characteristics. disput success further by First then, let us look at the outcomes of all these mediation attempts (we have omitted from our analysis cases where mediation was offered only; the focus of our inquiry is on mediation offered, accepted, and undertaken). Given the complexity and uncertainty that may characterize the term "outcome," we have decided to adopt a strictly behavioral approach (but see Frei 1976) and focus on the observed differences mediation has had on the parties' conflict behavior within a four-week period. Thus we look at mediation outcomes in terms of four possible dimensions: unsuccessful, cease fire, partly successful, and fully successful. For purposes of our analysis, we group together the last three dimensions into a "successful" category and contrast it with the other cases in the "unsuccessful" category. As we can see from Table 1, 71.9% of all mediation attempts were unsuccessful, that is, had no discernible impact on the subsequent behavior of the parties, whereas 29.1% of mediation cases did achieve some degree of success. How is the outcome of mediation affected by the nature of the dispute? Under what kinds of disputes is mediation more effective? We begin our analysis by identifying significant dispute variables and suggesting their possible impact on mediation outcomes. This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms lo Bercovitch, Langley /INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 675 THE NATURE AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DISPUTE It seems a truism to suggest that the nature of a dispute will significant impact on the success or failure of a mediation attempt and Pruitt (1989), in their excellent review of mediation research, that unfavorable dispute characteristics "are likely to defeat even adroit mediators" (p. 405). Similarly, Ott (1972) argues that "the su failure of mediation is largely determined by the nature of the dispu the characteristics and tactics of the mediator marginal at best" (p It would be useful to go beyond such general statements and d aspects of a dispute, code these systematically, and analyze their i the success and failure of mediation. This is what we propose to d section. We begin by reviewing three general aspects pertaining to th of the dispute that are generally thought to affect its course and These are (a) the intensity of the dispute, (b) the duration of the dispu time of intervention, and (c) the issues at the heart of the dispute. INTENSITY When discussing the impact of dispute intensity on the outcome international mediation, we are immediately confronted with two funda tal difficulties: definition and operationalization. Although intensity garded by everyone as an important dispute characteristic, there is a l clarity as to what precisely intensity signifies. Kressel and Pruitt (1989) conclude that high-intensity disputes ar likely to experience successful mediation. But, under the rubric of inten they include such diverse factors as the "severity of prior conflict," the of hostility," "levels of anger," and "intensity of feeling," as well a strength of "negative perceptions." They do not suggest how these ca defined, let alone operationalized. In their discussion of public-sector mediation, Kochan and Jick (1978) argue that "the intensity of the im will be negatively related to the effectiveness of the mediation pro (p. 213). But what they mean by "intensity" is not made explicit. Thi of definitional precision leads to considerable difficulty in operationa dispute intensity. To avoid this confusion, we will use one relatively indicator to test the hypothesis that mediation is less likely to succeed in intensity disputes. The most obvious and accessible measure of dispute intensity i number of fatalities in a dispute.1 We can logically expect a high le 1. Alternative measures of intensity, such as the overall duration of a dispute and th of fatalities per month, were also tested but proved to be unreliable indicators. This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 676 JOURNAL OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION intensity to be reflected in the number of fatalities incurred by both s Therefore, we postulate that high-fatality disputes will be less amenab mediation. We will examine this relationship below. DURATION OF THE DISPUTE AT THE TIME OF INTERVENTION A number of studies speak of a crucial moment in the life cycle of a di at which mediation will be most likely to succeed. Northedge and Don (1971), for example, note that "the position is more favorable when th exists a concatenation of circumstances which are already in operatio tending toward an improvement of the situation" (p. 308). Zartman (1 has suggested that a combination of "plateaus," "precipices," "deadloc and "deadlines" will produce moments of "ripeness" when the parties highly motivated to settle their disputes. The assumption here is that i waxing and waning of the complex social forces that make up an internat dispute, there are moments during which both parties will welcome m tion more openly. The exact nature of these moments is a matter of co erable speculation. Some theorists, such as Claude (1971) and Edmead (1971), have gested that mediation should be attempted early in the dispute, befo positions become fixed, attitudes harden, and an escalating cycle bec entrenched. Others, such as Ott (1972) and Pruitt (1981), suggest mediation will be more successful later, when conflict costs have be intolerable and both parties realize that they may lose too much by conti their dispute. We will examine below how the likelihood of succe mediation relates to the temporal dimension of a dispute. ISSUES It would seem logical that the issues at the heart of the dispute will quite influential in determining the outcome of mediation. This influence be divided into two areas: (a) the substantive nature of the issues at st and (b) their number and complexity. There is general agreement in literature that particular sorts of issues will lend themselves to mediation others will not. But there is disagreement as to exactly which issues ar most amenable to mediation. Ott (1972) has argued that mediation will be more successful in absence of vital national security interests, and he draws attention to particular difficulties faced when the question of territorial control involved (p. 616). Lall (1966) supports this view, noting that "when terr This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Bercovitch, Langley / INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 677 is at stake the party in possession tends to resist third party involvement" (p. 100). On the other hand, Northedge and Donelan (1971) highlight matters of national "honor" as being particularly problematic. Bercovitch (1984) and Hiltrop (1989) lend weight to this argument. In studies of labor mediation, they found that tangible issues, such as pay and employment conditions, were more amenable to mediation than disputes over intangible "matters of principle," such as union recognition. Kressel and Pruitt (1989) also conclude that "matters of principle" will defy mediation. To make sense of this somewhat confused picture, we coded the issues in dispute into "territory," "ideology," "security," "independence," "resources," and "other."2 The coding allowed for each dispute to have a primary, secondary, and peripheral issue. Here we will focus mostly on the primary issue in dispute. It is also possible to distinguish between tangible and intangible issues in dispute (Aubert 1963). Tangible issues pertain to concrete elements that can be measured in some way (e.g., money, territory, etc.). Intangible issues relate to parties' perceptions of needs or concerns with image, legitimacy, and presentation. Intangible issues usually reflect matters of beliefs and principles. As such they may be more difficult to discuss or mediate. Zubek et al. (1992) find strong evidence of an association between intangible issues and prolonged hostile behavior in community mediation. Does the same relationship hold for international disputes? Or are issues important only when combined with other variables (Vasquez 1983)? We turn now to the second aspect of the issues in dispute-complexity. Broadly speaking, the greater the complexity of the issues in dispute, the less likely that mediation will be successful. In his study on the process of mediation, Moore (1986) repeatedly draws attention to the influence that "the number and complexity of the issues involved" (p. 172) have on the outcome of mediation. This view is supported by several studies of mediator behavior (e.g., Bercovitch 1984; Fogg 1985; Kolb 1983), which suggest an inverse relationship between dispute complexity and effective mediation. Alternately, it may be just as plausible to hypothesize, as Lax and Sebenius (1986) or Raiffa (1982) do, that greater complexity creates greater opportu- nities for trade-offs, sequencing, and packaging, thus enhancing the chances of successful mediation. This relationship, too, should be examined empirically. 2. No disputes were coded as having resources as the primary issue, and it is difficult to say anything meaningful about "other," so both of these categories do not appear in the cross-tabulation of issue and outcome. This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 678 JOURNAL OF CONFLICTRESOLUTION ANALYZING RELATIONSHIPS: A MULTIVARIATE APPROACH QUALITATIVE DATA AND MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS Our discussion thus far identified a number of factors or variables wit significant impact on the success or failure of mediation. Traditionally impact is assessed using various bivariate models where the relations between each variable and mediation effectiveness is examined one at a ti We want to examine all these variables simultaneously, to examin interactions among them, and to assess their direct and indirect impa mediation effectiveness. To do so, we must employ a more sophisticated m of analysis that enables the simultaneous consideration of all the variable The dependent variable in this analysis, the success or failure mediation attempt, is inherently qualitative. Therefore, we must emp multivariate method that is appropriate for data of this type. The analys qualitative data has traditionally been limited to the use of two-dimen contingency tables. But the development of log-linear techniques in th twenty years means that this limitation no longer applies. Log-linear methodology enables the researcher to examine multidimens contingency tables containing qualitative (or categorical) data. Unfortunat this technique has hardly been used in the field of political science. T to developments built on the pioneering work of Goodman (1970, 19 1973), log-linear methodology has attained a much higher profile in chology, sociology, and psychometrics precisely because of the advant it offers in both theory and application over traditional multivariate techniq 3. Traditional multivariate techniques like analysis of variance (ANOVA) and m regression (MR) are designed and are strictly appropriate only for continuous or interv data. We reject the all too common practice of arbitrarily redefining qualitative variab continuous, and the resulting "measurement error, bias, and the loss of a significant am information" (King 1989, 4; see also King 1986). Log-linear techniques are in many analogous to ANOVA, but because they are specifically designed to deal with qualita categorical) data, they produce models that are more powerful and results that are more in terms of both statistical theory and the substantive hypotheses under investigation. This article employs general log-linear analysis to explore the goodness of fit of a nu of specific models to the data observed in our study. We also use logit models, a special t log-linear analysis, when our analysis is asymmetrical (i.e., when one variable has identified as the response, or dependent, variable). Both general log-linear models and models are based on maximum likelihood (ML) estimation techniques rather than least- procedures. For a discussion of the advantages of ML estimation and the potential of lik models of inference in political science research, see King (1989). Kennedy (1983, 229-34) has demonstrated that compared to ANOVA, MR or can analysis of variance (CVA) logit models tend to fit observed data better, can be more pow and are easier to interpret. A further advantage is that a number of useful follow-up proce are incorporated in log-linear analysis. For example, the X parameter estimates of the ef each interactive term within a model can be individually tested for statistical significan This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Bercovitch, Langley/INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 679 We use log-linear methods here for a number of reasons. First, the analysis remains qualitative and does not attribute meaning to arbitrarily assigned numerical values. Concepts in our study such as success and failure or the tangibility and intangibility of issues do not lend themselves to traditional multivariate techniques such as ANOVA and multiple regression, which rely on the assumption of continuous (or interval) levels of data measurement. Second, the strength and utility of the results and log-linear's model-building and hypothesis-testing orientation have considerable intuitive appeal. And finally, we employ this technique to demonstrate its potential in the field of mediation research. LOG-LINEAR METHODOLOGY The analysis presented here follows the methodology outlined by Ken (1983) in his excellent introductory text on log-linear analysis for beh research. It is also influenced by Agresti (1990), Christensen (1990), (1981), Haberman (1978a, 1978b), Knoke and Burke (1980), andMaras and Busk (1987). A brief, nontechnical explanation of the method w given here. In the usual two-dimensional contingency tables, the objective is to determine if one or both variables have an effect on the distribution of values in the other, or to establish that there is no such effect at all. Similarly, in multidimensional contingency table analysis, the main objective is to identify which variables are independent, which variables influence other variables, and, most importantly, which pairs or groups of variables have an interactive effect on others. Once we have established which variables will make up our multidimen- sional table, we propose to identify the interactive effects that have the strongest influence on the data (i.e., which relationships between variables are responsible for the observed distribution of the data within the cells of our table). More specifically, in this case, we want to know which relationships and interactions will influence whether a mediation case will fall into the success or failure category. We begin by combining those effects suggested in the literature as influential and positing a causal model. This model is then expressed in log-linear terms and tested for its ability to reproduce the observed cell frequencies (goodness-of-fit). Should the fit of the model be inadequate, we can then test the strength of individual, interactive effects in the model and suggest possible revisions to our multivariate hypothesis. In selecting the final model, we strive for (a) parsimony (a model that contains the fewest possible interactive effects for ease of interpretation) and (b) acceptable This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 680 JOURNAL OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION goodness-of-fit (a model that produces expected cell frequencies that fit observed data reasonably well). Three measures can be used to test the fit of general models and the imp of individual effects. First, the likelihood ratio chi-square statistic (L2) is u to test for the overall agreement between the expected cell frequenci generated by a model and the actual cell frequencies observed in the (Kennedy 1983, 89).4 A good-fitting model will have a relatively smal and is generally said to be adequate when the p value is greater than (Gilbert 1981, 68; Agresti 1990, 176).5 An ideal model would be one th surpassed this significance threshold and in which L2 was equal to the degr of freedom (Kennedy 1983, 222). Second, the L2 statistic, because of its additive properties, can be divi into component parts. As a result, the strength of an individual, interac effect can be found by calculating its component L2. The component L2 of effect is the difference in general goodness-of-fit that results from adding effect to a particular model.6 An important effect that improves consider the fit of the model will have a large component L2. Finally, the parameter estimates (X) for each effect can be analyzed relative size and statistical significance. Naturally, an important effect have a relatively large parameter estimate. 4. In some of the literature on log-linear methods, L2 is sometimes written as G2. For a explanation of the calculation of this statistic and its relationship to the more common Pe X2 statistic, see Agresti (1990), Kennedy (1983), and Marascuilo and Busk (1987). 5. Most researchers will be familiar with the Pearson chi-square statistic as a tes independence in two-dimensional contingency table analysis, where a significant X (p < . indicates disagreement between the data and the null hypothesis. However, when test general log-linear model, the opposite is the case. A nonsignificant L2 (p > .05) is the des result because this indicates agreement between the given model and the data. For ea understanding, we will say that a p value greater than .05 is "significant." This should n confused with the component L2, which can be interpreted as one would normally interpret t conventional 2 . 6. Determining the impact of each component term in a model is sometimes referred partitioning the chi-square. To calculate the component L2 of each effect, we assess the ch in the goodness-of-fit given by comparing a model containing the term in question wit identical model not containing that term. To ensure that we are testing only the contribution that specific term, we must "control" for all other possible influences; therefore, the term b tested should be removed (or added) to the model containing all terms of the same order three-way interaction term should be tested for its relative contribution to the full three interaction model. For example, the component L(ICF) is found by comparing the full thre interaction model with a model that is the same except for the absence of ICF: L2(ICF) = L2(F,IF,DF,CF,IDF,CDF) - L (F,IF,DF,CF,IDF,CDF,ICF) = 7.29 -.92 = 6.37 Thus the component L2 for ICF, as seen in Table 3, is 6.37. This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Bercovitch, Langley / INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 681 MODEL BUILDING AND TESTING The variables that are included in our analysis have been collapse the dichotomies shown in Table 2. The notation given is used as a k shorthand when discussing log-linear models. For example, (F) is the effect7 of fatalities, (FO) is a two-way interaction between fataliti outcome, and (IFO) is a three-way interaction between issues, fatalit outcome. In our review of the literature, we have identified a significant relationsh between low complexity (C) and successful outcome (0), and between lo fatalities (F) and successful outcome (O). So our first model includes th interactive effects (CO) and (FO). Furthermore, we posit links between tangible issues and low complexity (IC); tangible issues and low fataliti (IF); low complexity and early intervention (CD); low complexity and lo fatalities (CF); and early intervention and low fatalities (FD). Using thi notation, our initial model (Ml) of the dynamics of the dispute variables their impact on mediation outcome is written as follows:8 M1 = (IC,IF,CD,CF,FD,CO,FO). To help the reader interpret this somewhat unfamiliar notation model, M is represented diagrammatically in Figure 2. The arrangement of the variab in Figure 2 is important. Statistical analysis can establish only correlatio not causality. Therefore, when hypothesizing models and interpreting resu the decision about the direction and nature of causal relationships must guided by theory. If the interactive effects in model Ml are indeed influential, then the mo will predict cell frequencies that fit the observed data closely. However, log-linear test of the ability of this model to reproduce the cell frequen observed in the data yields an inadequate fit: L2(M1) = 35.31, df= 19, p .013. To revise Ml, we must assess the importance of each individual effect the model and attempt to identify other important effects that are missing the Ml model, we hypothesized a number of specific interactive effects, 7. Main effects are the independent, noninteractive effect of each variable (the independ marginal distribution). 8. The main effects of all variables are included in Ml but are not given separately in model notation. It is assumed that each variable continues to have an independent effect to som degree; therefore, all main effects are incorporated in general models. Our interest is determining which interactions are important above and beyond these independent effec therefore, only interactive effects will be given in the notation. The exception to this is the n model (in this case, the model of mutual independence, M0, in Table 4), which includes on main effects. This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 682 JOURNAL OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION TABLE 2 Variables and Categories for Log-Linear Analysis Parameter Notation Categories Outcome (O) (a) Success (b) Failure Fatalitiesa (F) (a) 100-1000 (b) 1000+ Issues (I) (a) Tangible (b) Intangible Complexity (C) (a) One or two issues (b) Three or more issues Duration at time of interventiona (D) (a) 0 to 12 months (b) 13 months or more a. Fatalities and duration are based on continuous data, but were in fact coded as categoric variables. Figure 2: Model M1 This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Bercovitch, Langley/INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 683 in doing so, we also hypothesized several null effects. For example, because little is known about the more complex interactions in international mediation, we hypothesized all three-way and four-way effects to be null. Because the fit of our initial model has proven to be inadequate, sound methodology compels us to test the significance of both hypothesized and null-hypothesized effects. To accurately test the impact of each effect, we must control for all other influences and deal with the model in a systematic fashion. Our initial model, M1, as shown in Figure 2, is arranged so that some variables temporally precede others. As we move from left to right in the model, we find variables that are at first responses, but then become explanatory influences on subsequent variables. To test the individual contribution of each effect, we move through the model in a stepwise fashion, testing the various explanation-response relationships in turn.9 The results of this exercise can be seen in Table 3.10 Table 3 clearly shows how partitioning the L2 into its components offers considerable insights into the relative strength of individual, interactive effects. It is important to remember that effects that do not achieve signifi- cance should not be completely discarded at this point; this process serves as a guide only." In this step-by-step, or rather effect-by-effect, analysis, we find support for all the effects in our initial model Ml except for the effect of complexity on duration (CD). But the CD effect does approach significance and still deserves further consideration. Tests of effects hypothesized to be null have revealed two significant, three-way interactions: the combined effect that the nature of the issue and the complexity of the dispute have on the level of fatalities (ICF); and the combined effect of complexity and the duration at the time of intervention on outcome (CDO). In light of this information, it would seem prudent to revise our initial model. A number of contending models are shown in Table 4. The first model- MO-is our null hypothesis. This is the model of mutual independence. It is included merely for purposes of comparison. The very poor fit of this model clearly demonstrates that the variables in the analysis are not independent of each other. Our Ml model shows considerable improvement, but, as noted earlier, the fit is not adequate. 9. This process is outlined in Kennedy (1983, 211-23). 10. Table 3 gives the component L2 for all hypothesized and null hypothesized effects when fitted to full logit models of the same order within their respective subtables. In logit models, the main effects of independent variables are not fitted, but the main effect of the dependent variable is fitted in all cases. 11. Because the terms in Table 3 are fitted to full-order interactive models, their effects may not be as pronounced as they may be when incorporated in more restricted models where fewer terms, and therefore less data, are used to estimate model parameters. This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 684 JOURNAL OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION TABLE 3 Component L2 for All Hypothesized and Null-Hypothesized Effects Component Effect Component L df p < 1 .00b'c (IC) 52.61 Effects fitted to (ICDD table (IF) 4.56 (DF) (CF) (ICF) (IDF) (CDF) (ICDF) 10.17 1 .0b'c Effects fitted to (I)a table Effects fitted to (ICFD) table (ID) (FD) (CD) (ICD) (IFD) (CFD) (ICFD) (IO) Effects fitted to (ICDFO) table (FO) (CO) (DO) (DFO) (CDO) (IDO) (ICO) (IFO) (CFO) 3.94 1 .05b'c 6.37 1 .02c 3.02 1 .23 1 .70 .92 1 .50 1 .30 1.21 .10 2.95 1 .01b 1 .10b 10.04 1.44 1 3.02 1 .30 .10 .17 1 .70 .92 1 .50 .06 1 .90 1 .01Ob, 10.58 1 .02 'c 5.83 .06 1 .90 1.90 1 .20 9.11 1 .01C .05 1 .15 1 .70 1.20 1 .30 .26 1 .70 .90 All higher-order interactions combined .61 5 99d a. The underlined variable denotes the dependent in the step-by-step analysis. b. Effects hypothesized in model M1. c. Statistically significant effects. d. All higher-order interactions (four-way and f model by L = .61, df= 5, p < .99, suggesting that nonexistent. As a result of our analysis of compon model: M2. This model incorporates t found to be influential. Also, a test of th new model suggests that it be retained 12. When incorporated in model M2, the CD effe This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Bercovitch, Langley/INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 685 TABLE 4 General Log-Linear Tests of Contending Models Model L2 df p< Mo (I, C, D, F, 0) 149.14 26 .000 M1 (IC, IF, CF, CD, DF, CO, FO) 35.31 19 .013 M2 (IC, IF, CF, CD, DF, CO, FO, ICF, CDO) 25.38 17 .087 M3 (IC, IF, CD, DF, CO, FO, ICF, CDO) 25.38 18 .115a a. The comparable Pearson X2 statistic gives an even better fit of 2 = 21.23, df= 18, show improved goodness-of-fit, and it surpasses our criteria for signif The ability of this model to reproduce the observed data appears to be ad A standard log-linear follow-up procedure, the examination of t parameter estimates generated by M2, was conducted.13 The effect o plexity on fatalities (CF) (which in Table 4 can be seen to be close t criteria for exclusion) has a particularly small parameter estimate th not reach significance: X(CF) = .006, Z = .05. In short, this effect i influential and makes virtually no contribution to the fit of the M2 m In model M3, we remove the questionable CF relationship and ob no change in L2. We do observe, however, that the significance of th improves and the overall fit of the model is improved by the increas number of degrees of freedom.14 Thus, as a result of this simple pr testing general models and examining individual component L2s and eter estimates, we have found a model that satisfies our criteria of par and predictive power. Finally, we use another measure to test the ability of the model to e the variance in the data across all the variables in the cluster. The measu a log-linear R2 statistic analogous to R2 in multiple regression. Whe calculated on the fit of model M3, we get R2 = .829.15 In other wor model accounts for nearly 83% of the variance in this cluster of var We will retain M3 as our model of the dynamics of the nature of the d and the outcome of international mediation. 13. For a comprehensive discussion of the interpretation of log-linear X parameter estimates, see Alba (1987). Here we compare only the relative size of Xs and perform standard Z tests of significance. 14. As noted earlier, as the L and the degrees of freedom of the model converge, the fit of the model can be said to improve (Kennedy 1983). 15. It should be noted that this measure is not directly equivalent to R in regression analysis. In essence, it gives a measure of the variance explained beyond that which can be accounted for in the null hypothesis. For a fuller description and discussion of this measure, see Christensen (1990, 150); Haberman (1978a, 17), and Kennedy (1983, 228). This log-linear R2 is calculated as follows: This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 686 JOURNAL OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION Model M3 is represented graphically in Figure 3. The coefficients on t interactions are the X parameter estimates generated by the model for effect. Parameter estimates are not multiplicative, as in traditional p analysis, because our data, and hence our method, are qualitative and do usually work in such equations. Thus we cannot multiply paths betwe variables to estimate the size of indirect causal effects (see Knoke and Bu 1980,45). Lambdas are, however, excellent indicators of the relative stren of interactive effects within the given model. All coefficients in Figure 3 are positive, indicating a correlation betw the first categories of the variables concerned [categories marked (a) in Tabl Thus we find a very strong correlation between tangible issues and lo complexity disputes. Clearly, disputes over tangible issues are usually sin issue disputes and as such lend themselves to compromise solutions. We also find a moderately strong correlation between tangible issues low fatalities. Independent of this, there is a further combination of complexity and tangible issue that correlates with low fatalities. Low c plexity also ties in with early intervention, which in turn is quite stron correlated with low fatalities. This is expressed as a two-way effect, for equally plausible that early intervention will keep fatalities low and t fatalities will tend to be low early in the dispute, which may act as an impe to intervene. Fatalities is one of the three direct influences on outcome that has b identified. There is a clear, positive relationship between low fatalities successful mediation outcomes. Other direct influences on outcome are interaction of low complexity and brief dispute duration, which correl 2 )L2(M0) - L2(Mi) L2(M0) Where L2(Mo) is the fit of the null-hypothesized model and L2(Mi) is the fit of the model of interest. Because the null hypothesis represents the total variability of the data (i.e., between the saturated model and the smallest possible interesting model, or null hypothesis), R gives us a measure of the amount of variation in the data that is explained by the model of interest. In this case, the null hypothesis is the mutual independence model. R2 for M3 is given below: R2( L2(M0)-L (M3) R (M0) 149.14- 25.38 149.14 = 829 This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Bercovitch, Langley/INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 687 Figure 3: The Nature of the Dispute and Mediation Outcome: A Causal Model NOTE: Coefficients given are lambda parameter estimates. Z-value tests of significance are given in parentheses. Significant at the 95% confidence level. with success and, independent of this, the positive impact of low complexity on successful outcome. Model M3 has shown its ability to explain much of the variance in the data across the cluster as a whole, but what of its ability to explain outcomes? When we apply the log-linear R2 equation to an analysis that explicitly posits outcome (O) as the dependent variable in combination with the effect of fatalities on outcome (FO), the effect of complexity on outcome (CO), and the effect of the interaction of complexity and duration on outcome (CDO), we get R2 = .656.16 Model M3 accounts for around 65% of the variance in outcome across the cluster of dispute variables. 16. The L2s for this equation were found by fitting the logit models given below to the ICDFO table. In this case, the null hypothesis is the model O, where outcome is independent and the model of interest includes those effects found to have an impact on outcome (O, FO, CO, CDO). Thus we have a measure of the amount of variance in outcome explained over and above that of the null hypothesis: This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 688 JOURNAL OF CONFLICTRESOLUTION The nature of the dispute is clearly a major determinant of mediat outcomes. A good deal of the variance in outcome is yet to be explained. is not surprising when we remember that, in this article, we considered o one of the clusters of variables that have been identified in our concep framework as affecting mediation outcome. CONCLUSIONS For too long we have assumed that mediation can alter the key el of a dispute without really studying how these key elements can mediation. Mediators in the personal, communal, or international operate within a specific context, a context that presents constraint as opportunities for a mediator. There is a reciprocal relationship b the context of mediation and its style and effectiveness. Each cont require its own "do's" and "don'ts." In other words, the contingent generic-application of mediation may be the key to its success. Here we have analyzed how the nature of the dispute, as one of t crucial contextual determinants, affects mediation outcomes. We h aggregated the nature of the dispute into concrete, empirical dimen issues, relationship, and interactions, and gathered data on issues, part conflict management behavior in 97 international disputes. In this s use our initial set of 364 mediation cases to determine which characteristics have an effect on mediation and how they affect it. We use log-linear analysis to examine the impact of significant v on mediation outcomes and the interactive effects among these v Our findings indicate the direct impact that fatalities and dispute com have on mediation outcomes and the interactive effects of fatalit dispute complexity with issues and timing of intervention. High f encourage further hostility and contentious behavior, and these dimin likelihood of mediation effectiveness (just as they diminish the ch an agreement in negotiations) (see Pruitt 1981). Dispute complexity in any event is associated with lengthy, protracted conflicts and R(O,FO,CO,CDO) L2() - L(O,FO,CO,CDO) L2(0) 42.79- 14.68 42.79 = .656 This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Bercovitch, Langley / INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 689 fatalities, also appears to be incompatible with successful mediation. Our results suggest that dispute duration also has a strong inverse relationship with successful mediation, but only when it combines with fatalities and complexity. These results are unsurprising in that they indicate that intensely hostile disputes, with many issues at stake and high fatalities, are not particularly amenable to mediation any more than they are to negotiation, adjudication, or even the intervention of an international organization. They do, however, offer a clear set of policy implications from the mediator's perspective. Mediators can enhance the likelihood of an agreement by reducing or repackaging the number of issues in dispute; focusing on tangible rather than intangible issues; initiating mediation once the disputants have had some time to sort out their conflict, but long before the level of hostility and fatalities get too high; and pursuing mediation strategies that can be adapted to the demands of different disputes. The results may not reveal anything startling, but it is better to have such information confirmed than to speculate about it. The kind of work we have described above draws attention to prior contextual conditions and their impact on conflict management in general and mediation in particular. It is futile to describe mediation or mediation behavior as if it were unrelated to these conditions. Just as mediation purports to change, affect, or influence these prior conditions, so too can these conditions change or affect mediation. There is a reciprocal relationship of influence in all aspects of conflict management. REFERENCES Agresti, A. 1990. Categorical data analysis. New York: Wiley. Alba, R. 1987. Interpreting the parameters of log-linear models. Sociological M Research 16:45-77. Aubert, V. 1963. Competition and dissensus: Two styles of conflict and conflict resolution. Journal of Conflict Resolution 7:26-42. Bercovitch, J. 1984. Social conflicts and thirdparties. Boulder, CO: Westview. . 1986. International mediation: A study of the incidence, strategies, and conditions of successful outcomes. Cooperation and Conflict 21:155-68. . 1989. International dispute mediation: A comparative empirical analysis. In Mediation research, edited by K. Kressel and D. G. Pruitt, 284-99. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Bercovitch, J., J. Anagnoson, and D. Wille. 1991. Some conceptual issues and empirical trends in the study of successful mediation in international relations. Journal of Peace Research 28:7-17. Bercovitch, J., and R. Wells. 1993. Evaluating mediation strategies: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Peace and Change 18:3-25. This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 690 JOURNAL OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION Brett, J., R. Drieghe, and D. Shapiro. 1986. Mediator style and mediation effectivene Negotiation Journal 2:277-86. Butterworth, R. 1976. Managing interstate conflict. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press Camevale, P. 1986. Strategic choice in mediation. Negotiation Journal 2:41-56. Christensen, R. 1990. Log-linear models. New York: Springer-Verlag. Claude, I. 1971. Swords into ploughshares. New York: Random House. Edmead, F. 1971. Analysis and prediction in international mediation. New York: UNITAR. Fogg, R. 1985. Dealing with conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution 29:330-58. Frei, D. 1976. Conditions affecting the effectiveness of international mediation. Peace Scie Society (International) Papers 26:67-84. Gilbert, G. N. 1981. Modelling society. London: George Allen and Unwin. Goodman, L. A. 1970. The multivariate analysis of qualitative data: Interactions among mult classifications. Journal of the American Statistical Association 65:226-56. .1971. The analysis of multidimensional contingency tables: Stepwise procedures and direct estimation methods for building models for multiple classifications. Technometri 13:33-61. . 1973. The analysis of multidimensional contingency tables where some variables are posterior to others: A modified path analysis approach. Biometrika 60:179-92. Haberman, S. J. 1978a. Analysis of qualitative data. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press. - 1978b. Analysis of qualitative data. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press. Hiltrop, J. 1989. Factors associated with successful labor mediation. In Mediation research, edited by K. Kressel and D. G. Pruitt, 241-62. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Holsti, K. 1966. Resolving international conflict: A taxonomy of behavior and some figures on procedures. Journal of Conflict Resolution 10:272-96. .1987. International politics: A framework for analysis. 5th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Kennedy, J. 1983. Analyzing qualitative data. New York: Praeger. King, G. 1986. How not to lie with statistics: Avoiding common mistakes in quantitative political science. American Journal of Political Science 30:666-87. . 1989. Unifying political methodology: The likelihood theory of statistical inference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Knoke, D., and P. Burke. 1980. Log-linear models. Sage University Paper series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, No. 07-020. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Kochan, T., and T. Jick. 1978. The public sector mediation process: A theory and empirical examination. Journal of Conflict Resolution 22:209-40. Kolb, D. 1983. Strategy and tactics of mediation. Human Relations 36:247-68. Kressel, K., and D. Pruitt. 1989. Conclusion: A research perspective on the mediation of social conflict. In Mediation research, edited by K. Kressel and D. G. Pruitt, 241-62. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Lall, A. 1966. Modern international negotiation: Principles and practice. New York: Columbia University Press. Lax, D., and J. Sebenius. 1986. The manager as negotiator. New York: Free Press. Levine, E. 1971. Mediation in international politics: A universe and some observations. Peace Science Society (International) Papers 28:23-44. Marascuilo, L., and P. Busk. 1987. Loglinear models: A way to study main effects and interactions for multidimensional contingency tables with categorical data. Journal of Counseling Psychology 34:443-55. Moore, C. 1986. The mediation process. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Bercovitch, Langley/INTERNATIONAL MEDIATION 691 Northedge, E, and M. Donelan. 1971. International disputes: The political aspects. London: Europa. Ott, M. 1972. Mediation as a method of conflict resolution: Two cases. International Organization 26:595-618. Pruitt, D. G. 1981. Negotiation behavior. New York: Academic Press. Raiffa, H. 1982. The art and science of negotiation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Raymond, G., and C. Kegley. 1985. Third party mediation and international norms: Atest of two models. Conflict Management and Peace Science 9:33-51. Small, M., and J. D. Singer. 1982. Resort to arms: International and civil wars, 1816-1980. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Vasquez, J. 1983. The tangibility of issues and global conflict: A test of Rosenau's issue area typology. Journal of Peace Research 20:179-92. Wall, J. 1981. Mediation: An analysis, review, and proposed research. Journal of Conflict Resolution 25:157-80. Wall, J., and A. Lynn. 1993. Mediation: A current review. Journal of Conflict Resolution 37:160-94. Young, 0. 1972. Intermediaries: Additional thoughts on third parties. Journal of Conflict Resolution 16:51-65. Zartman, I. W. 1985. Ripe for resolution. New York: Oxford University Press. Zubek, J. M., D. G. Pruitt, R. S. Peirce, N. B. McGillcuddy, and H. Syna. 1992. Disputant and mediator behavior affecting short term success in mediation. Journal of Conflict Resolution 36:546-72. This content downloaded from 220.248.60.237 on Sun, 09 May 2021 09:21:33 976 12:34:56 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms