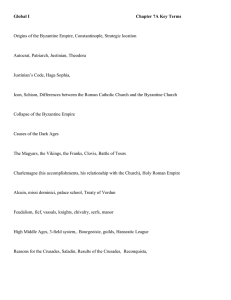

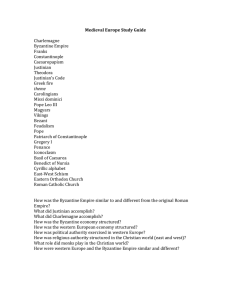

Plan... Introduction. Main part. 1. Byzantine history and its main stages. 2. The place of the church in Byzantine society. 3. Culture of Byzantium. Philosophy. Art. Literature. 4. Russia and Byzantium. Conclusion. Literature. Introduction. One of the most important centers of medieval art was Byzantium, a state that was formed in 395 on the site of the Eastern Roman Empire and existed until 1453. Byzantine art is an important stage in the development of medieval world and European artistic culture. The barbarian invasions did not affect Byzantium to the same extent as Western Europe. Ancient forms of life and economic structure have been preserved here, which have already disappeared in the West. Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Ephesus remained Hellenistic cities in their appearance. Until the 7th century, there was an ancient folk theater. The ancient tradition clearly manifested itself in art: in the center of attention of the Byzantine artist, as in antiquity, was the person embodied in the image of the Christian god and saints. In his image, the correct proportions of the figure, thin plastic forms, and precise drawing were preserved. The content of Byzantine art reflected the religious and philosophical views of the emerging medieval society. Passive contemplation, which, according to the philosophy of Eastern Christianity, opened the way to the knowledge of God and contained the highest harmony, was expressed in the motionless concentration of images. The insight and poetic perception inherited from antiquity were manifested in the disclosure of the finest shades of human feelings. In Byzantium, where the emperor combined secular and religious power, art, appealing to all subjects, played an important role in creating ethical ideals that unite religious, state and personal principles. Main part. 1. Byzantine history and its main stages. Byzantium is a state of 4-15 centuries, formed during the collapse of the Roman Empire, in its eastern part. The capital is Constantinople. Population Greeks, Syrians, Kont, Armenians, etc. The main language is Greek. 2 In the 4th - early 7th centuries, feudalism began to take shape in Byzantium (while maintaining slavery until the 7th century). The features of Byzantine feudalism include: the cities that survived in the early Middle Ages as centers of crafts and trade, a centralized state apparatus and tax system, the absence of class isolation of the ruling class, a developed vassal system, the fragility of trade and craft corporations, rural communities, and urban communes. Byzantium reached its greatest territorial expansion in the 6th century under Justinian, becoming a powerful Mediterranean power. The conquests of the 7th mid-9th centuries by the Arabs and Slavs reduced its territory mainly to part of the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor. The capture of Constantinople by the participants of the 4th crusade in 1204 led to the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the founding of the Latin Empire, and not on the territory conquered by the crusaders the Greek states - the Micaean, Trebizond empires, the Epirus state. The Byzantine Empire was restored by Michael VIII in 1261, the capture of Constantinople by Turkish troops in 1453 put an end to Byzantium. In the history of the Byzantine Empire, three periods are clearly outlined in accordance with its internal development and the role that this state played in the international life of the Middle Ages. The first period spans three and a half centuries from the 4th to the middle of the 7th century. In this era, Byzantium was the successor to the Roman Empire, outliving the slaveholding ancient order. The second period began in the middle of the 7th century and lasted until the early 13th century. Byzantium at this time became predominantly Greek, and in the 11-12 centuries. Greco-Slavic state. The socio-economic relations of this era are characterized by the predominance of the countryside in the life of society. The process of strengthening the already formed feudal institutions is under way. The last period in the history of Byzantium is associated with the Latin conquest and the fragmentation of the empire into separate states; it was marked by 3 an unequal struggle with the mighty Ottoman Empire, which ended tragically in the middle of the 15th century. 2. The place of the church in Byzantine society. A special look of social and cultural life in Byzantium was given by the peculiar features inherent in Eastern Christianity and the Byzantine Church. Significant differences have long been outlined between the Eastern Orthodox and Western Catholic churches. The final split took place after the conquest of Byzantium by the crusaders, when the Catholic Church tried to proclaim papal supremacy in the East, but met with strong resistance from both the Greek clergy 4 and the general population. In the centuries that followed, church divisions escalated into open enmity. In Byzantium, the church did not have the economic and administrative authoritarianism that developed in Western Europe. The Orthodox Church, both economically and politically to a greater extent than the Catholic, depended on the state, on imperial grants, and was more closely connected with the centralized state system. In the Byzantine Empire, Orthodox hierarchs did not claim supremacy over the powerful secular government. If in the West the Pope enjoyed indisputable moral authority and tremendous real power, in the East church councils stood above the patriarchs and only they were the creators of church canons, and they themselves were subject to secular authority. In Byzantium, the line between clergy and laity was not as sharp as in the West. In the West, the dominant doctrine was that a person's salvation depends on the activities of a special organization - the church, in whose hands is the assessment of the believer's merits and the remission of his sins. Eastern Christianity was distinguished by great individualism, assigned an important role in the salvation of a person to individual prayer, and through it allowed a mystical fusion with the Divine. Differences regarding church rituals were quite sharply marked between the eastern and western churches. These differences developed over the centuries and were not only the result of dogmatic disagreements, but a symbolic expression of church traditions, which were influenced by local customs adopted in the church ritual of a particular locality. Linguistic differences and territorial disunity exacerbated these differences. The Byzantine monastery as a special social group, unlike the Western European one, provided the monk with more freedom in choosing a way of life, a type of asceticism and an individual way of salvation, which did not exclude the economic and administrative dependence of the monasteries on the state. 5 3. Culture of Byzantium. Philosophy. Art. Literature. Since the crisis of the slave-owning society in Byzantium did not take the same forms as in the Western Roman Empire, this determined the preservation of ancient traditions in the development of Byzantine philosophy. During the Early Middle Ages in the IV-V centuries. Neoplatonism was widespread in Byzantium, representing a combination of Stoic, Epicurean and skeptical teachings with the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle. The most famous representatives of this trend were Proclus (410-485) and John Philopon, or Grammaticus (VI-VII centuries). Most of the neo-Platonists used it to establish Christianity. Some of them were followers of Aristotle. However, the use of Aristotle's system was carried out with the removal of the most progressive elements from it, which was especially 6 manifested in the views of the Grammar. In the late VI - early VII centuries. in Byzantium, the departure from slavery and the establishment of feudal relations were accompanied by mystical moods among the ruling classes. Maximus the Confessor (580-662) played an important role in the formulation of mystical teachings. The era of the Early Middle Ages became for Byzantium a time of struggle between various philosophical views and their adaptation to the interests of the nascent feudal society. Of great importance was the conflict between iconoclasts and icon-worshipers, which resulted in the religious movement in the 8th-9th centuries. One of the leaders of the icon-worshipers was John Damascene (c. 675 c. 754), the author of The Source of Knowledge. The first part of this work "Dialectics" - became the basis of all medieval scholasticism. The ceremonial restoration in 843 of the veneration of icons is celebrated by the Eastern Church. The beginning of the Middle Ages was the final stage in the literature of the slave society. Although during this period Christianity was established everywhere, ancient traditions were still strong in all areas of ideology, especially in poetry. Secular poets of that time retell ancient myths, use ancient principles of versification. At the same time, the ancient metric is also used by church poets. At the same time, poets pay tribute to the Gospel stories. Since no monuments of folklore have survived, then folk art and its features are judged by the church literature of that time. The church, trying to consolidate its victory over paganism, used folk beliefs, language and songs, that is, church poetry used the folk language. A poetic meter was formed, which received the name of a folk verse. The lyricist of this period was Roman the Sladkopevets, who wrote in a folk language, a size close to folk songs, his hymns became popular in the Orthodox Church. He is considered the greatest poetic gift of Byzantium. Epic songs about the struggle against external enemies appeared, glorifying the heroism of the defenders of their land. On their basis, a feudal poem about Digenis Akrit was later written. The struggle of the popular masses against feudal 7 exploitation was reflected in oral creativity. Fragments of the so-called animal epic have survived, the form of which the people used to satirically depict masters. Period VII-IX centuries. characterized by a sharp decline in the number of surviving literary monuments, as well as a weakening of the ancient tradition. The decline in written literary sources is explained not by the savagery of Byzantium, but by the acute class struggle that took place during the formation of feudalism and was accompanied by religious fanaticism. In connection with the final victory of Orthodoxy, practically only theological literature survived. She was represented by: Kosma Magomsky (VIII century) - one of the largest church singers, John Damascene, who also gained fame by the canons. The pillar of icon veneration was Theodore the Studite (759–826), the author of canons, hymns and epigrams from monastic life. By this time, the forms of religious works, including chants, had changed. The anthem was replaced by a canon, distinguished by mannerism, artificiality, But secular poetry did not stop either. Particularly important is the so-called "Miriobiblon" (Greek. Many books), consisting of a kind of annotations to 280 antique and early Byzantine works with commentary. "Miriobiblon" is a kind of encyclopedia with elements of a reader. The author of this collection was Patriarch Photius (c. 810 or c. 820-890). He combined the ministry of the church with the fruitful activity of an enlightened philanthropist, patron of sciences and arts, admirer and expert of ancient culture. Miriobiblon includes works on philosophy, theology, medicine, works by historians and romance novels, travel descriptions and oratory. The value of Photius' work grows immeasurably, since many of the now lost works of ancient authors have come down to us only from this work. Photius' criticism is considered the first example of literary criticism in the Middle Ages. This secular current of Byzantine literature distinguishes it from the entirely theological literature of the West. Folk art of this period was influenced by Slavic colonization. A number of proverbs and sayings firmly entered the life of the Byzantines from Slavic folklore. 8 The art of the Byzantine Empire was complex due to the historical peculiarities of the country's development. Various peoples inhabiting the empire played an important role in the formation and development of art. The idea of the sacred nature of the political organization of the state was reflected in the art of Byzantium and determined the overwhelming predominance of religious themes and the abstract nature of art. At the same time, the development of art was combined with the Greco-Roman artistic traditions, which were widely included as heritage in the culture of Byzantium. The highest flowering of Byzantine art occurred during the reign of Emperor Justinian (482 or 483-565), when the empire reached a size almost equal to the old Roman state. Under Justinian, Byzantine art acquired complete independence. Art reflected in its images the state and religious ideas, as well as the wealth of the Byzantine Empire. The peculiarity of the official art of Justinian's time is the display of palace life as a magnificent ceremony, theatrical and solemn cult. A cycle of mosaics was created in the Chalke palace in Constantinople, which depicts the military triumphs of the Byzantine commanders. Among the outstanding monuments of the middle of the 5th century. refers to the mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna. This is the tomb of the Byzantine princess, daughter of Emperor Theodosius. The tomb with a dome (belongs to the eastern type of structures) has massive forms, it has impenetrable walls, low corrugated vaults, which preserve the crypt twilight. At the same time, the walls of this tomb were decorated below with precious marble cladding of the most delicate shades. The upper part of the walls sparkles with mosaics with lush floral ornaments. Above the entrance to the tomb there is a mosaic made in light colors with the image of Christ in the image of a shepherd among sheep against the background of a landscape. In the center of the dome there is a symbolic cross, on the walls - the figures of the martyrs against a blue background stand out in clear silhouettes and look like the ancient teachers-philosophers. Thus, In the capital of Byzantium, Constantinople, an outstanding unified architectural ensemble took shape: the Hippodrome, the Great Palace with a floor 9 lined with mosaics, and the central building of the city - the temple of St. Sophia (built in 532-537). This is the main monument not only of this era, but of the entire Byzantine history. The hippodrome was not only a place for sports, but also the only place where the people could communicate with the rulers. The Temple of Sophia was built by the Asian Minor architects Anthimius of Thrall and Isidore of Miletus. Then the building was destroyed by fire and reerected on one of the hills of Constantinople. In shape, it is a domed basilica: the main artistic concept is revealed in the interior of the cathedral, which is a square hall in plan, crowned with a colossal dome, as if floating in the air. The diameter of the dome is 31.4 m. Gradually rising semi-domes adjoin this dome from both sides. The walls are faced with marble slabs of various colors and mosaics. The peculiarity of the decoration of the temple is the combination of splendor with a sense of the infinity of space. This temple surpasses all other buildings with its size and daring construction methods. The temple of Sophia also amazes with its artistic perfection - two types of early Christian architecture merged together domed and longitudinal. At the same time, this whole is diverse in meaning. The dome contains the heroic, cosmic significance of the likeness of the world, but at the same time it overshadows the meeting place of the community, that is, living people. It is believed that in no building of antiquity was the greatness of the world given in such a ratio with the human, as in Sofia. Along with the creation of large urban centers, local artistic traditions developed, thanks to which national characteristics were expressed. Architectural monuments were created in monasteries and villages of Syria, Asia Minor, Egypt. Simultaneously with the addition of the early Byzantine church, the style of wall painting was formed. Her favorite technique is mosaic, which has its origins in antiquity. Byzantine mosaicists enjoyed all the richness of the colorful spectrum. Their palette includes delicate blue, green and bright blue paints, pale lilac, pink and red in different shades. The mosaic achieves the greatest strength due to the fusion of color spots of smalt with a gold background. The Byzantines loved gold: 10 it mattered to them both as a symbol of wealth and luxury, and as the brightest of all colors. For Byzantium, secular art was rare. In the mosaics of the church of St. Vitali (San Vitale) in Ravenna, two scenes stand out: one depicts the Emperor Justinian and Bishop Maximian, accompanied by his retinue, and the other depicts Justinian's wife, Empress Theodora. Before us is a vivid gallery of images of courtiers - their portraits are expressive. And if the young emperor is somewhat idealized, then the secondary characters are, as it were, snatched out of life: the bishop has sparse bristly hair, the monk has a bony, sinewy face and the look of a fanatic, the courtier has a dull face swollen with fat. The portraits in the Ravenna mosaic are transformed into a solemn procession - in it the emperor joins the unearthly greatness. The emperor is in a central position. In a slight turn of his figure and the direction of his hands, a spiritual impulse is expressed in him and his companions - the figures do not step on the ground, but, as it were, float, float. The slim, overly elongated proportions of the figures contribute to this impression. The Byzantine master primarily strove to express the godlike character of the imperial power. A fresco known as the Nicene Angels has survived in Nicaea. Before us is the image of an angel - a half-god, half-man. The angels wear the heavy brocade robes of the imperial bodyguards. The figures are frozen, not very expressive, but the faces are filled with amazing charm. According to art critics, these mosaics with the recently uncovered mosaics of the Temple of Sophia in Constantinople are the most sublime of all known creations of early Byzantine painting. In their vitality, the Nicene Angels are not inferior to the best antique portraits: a gentle oval of the face, an open forehead, loose hair, large eyes, an elongated nose and small lips. All this is transformed into the image of spiritualized beauty. By the VII century. include the mosaics of the church of St. Demetrius in Soluni. Compared to the Nicene and Ravenna mosaics described above, they already represent a different artistic world. Although the faces retain portrait features, the whole composition seems to have frozen: all the figures are 11 motionless, not connected with each other, symmetrical - this is a young saint with huge, wide eyes, and both donors, and representatives of secular and spiritual authorities - the bishop, the prefect. The characters are devoid of lyrical enthusiasm, they are almost idols, objects of superstitious worship. Their figures resemble stone pillars - Byzantine art, as it were, returns to its very original stage. The contradictory nature of early Byzantine art, which was noted, paved the way for the emergence of iconoclasm - a socio-political and religious movement in Byzantium in the 8th-9th centuries, directed against the cult of icons. In art, the struggle was expressed in the denial of the legitimacy of sacred images, that is, icons, as well as in the destruction of the monuments of church art by the iconoclasts. In their works, the iconoclasts developed non-religious motives: in temple murals they depicted birds, animals among vegetation, architectural motives; in secular palace buildings, mosaic paintings glorified the victories of emperors or depicted court ceremonies. The victory of the icon-worshipers meant the defeat of artistic freedom of thought and the further subordination of art to the church. Fifty years of iconoclasm were deeply reflected in the life of Byzantine society. Only in 787 in Nicaea, and not in the capital, the Seventh Ecumenical Council gathered, at which the dogma of veneration of icons was formulated and proclaimed. An unsurpassed example of Byzantine monumental art of the middle of the 9th century. - mosaic of St. Sophia of Constantinople. The majestic, seated in a calm pose, the huge figure of Mary with a baby in her arms is the embodiment of sublime spirituality. The Archangel Gabriel standing next to him is striking in his resemblance to an angel, he is the embodiment of earthly and at the same time heavenly beauty. Early Byzantine monumental art was supplemented by monuments of applied art, that is, art of small forms. Thus, in Ravenna, this is the carving that adorned the capitals of the columns; Maximian's armchair with ivory reliefs, etc. Sculptures of the 5th-6th centuries have survived to this day. from ivory, which are called consular diptychs. They often depict circus scenes. 12 An excellent example of applied art is the Cypriot dish "The Betrothal of David", which combines features of the Byzantine monumental style with the classical ones. The building is distinguished by solemn calm and symmetry. In the center is the priest, on the left is David, on the right is his bride. The group is flanked by two graceful flutists, like shepherdesses in pastorals. The whole composition is perfectly inscribed in a round frame. Against the background of the group there is a portico; it not only supports the figured composition, but also highlights the central figure. As art historians note, antiquity did not know such a connection between figures and architecture. Miniatures of the Early Middle Ages, despite their adherence to antique designs, at the same time bears the stamp of abstract artistic images. Icon painting of the most ancient period testifies to the transition from individual antique portrait to symbolic depiction of saints. 4. Russia and Byzantium. One of the important characteristic features of Byzantine culture was its ability to influence young peoples who entered the historical arena at the beginning of the Middle Ages. It passed on to them the experience of previous generations, allowed them to join the most important achievements of the ancient world, made the process of world cultural development continuous. The honey agarics of Byzantium played a significant role in the choice of the direction of artistic creativity in ancient Russia. Cultural ties with Byzantium largely determined the cultural appearance of ancient Russian art. 13 For example, this influence is felt in urban planning and the construction of temples. This influence is especially felt in painting. For example, the picturesque decoration of the Church of St. Sophia generally follows Byzantine patterns. The authors of the mosaics and murals covering the vaults, walls, pillars from top to bottom were the Greeks, although there is no doubt that Russian craftsmen also took part in decorating the cathedral. From Byzantium, the fine arts of Kiev took not only picturesque decoration of churches, but also miniatures. The influence of Byzantium was especially great in icon painting. We can say that the art of icon painting in Russia came from Constantinople. Ancient Russia did not know this art. The highest flowering of icon painting in Russia is associated with the name of Theophanes the Greek, a native of Byzantium, who appeared in Novgorod, then worked in Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod. His paintings, frescoes and especially icons are considered to be masterpieces of medieval art. Conclusion. Talking about Byzantium as a powerful state that united many peoples and territories is, in many cases, easier, it is about Byzantine culture, reminiscent of a phantom. It exists and it does not exist: in every phenomenon of Byzantine culture we find Greco-Roman antiquity, Jewish, Arab, Persian and many other influences that make it difficult to distinguish a specific beginning in it, and sometimes simply obscure it. In addition, she did not have to go from becoming to flourishing, like many other cultures. It has no clear boundaries either in time or in space; it has repeatedly experienced periods of prosperity and decline. The course of Byzantine 14 cultural reality can be connected with all certainty only with the historical boundaries of the existence of the state and its brilliant capital, Constantinople. Literature... 1. Culture of Byzantium. - M .: Higher school, 1994. 2. Kazhdan A.P. Byzantine culture. - SPb.: Aleteya, 2000. 3. Uraltsova Z. V. Byzantine culture. - M .: Nauka, 1988. 4. Soviet encyclopedic reference book. - M .: Soviet encycl., 1981. 15