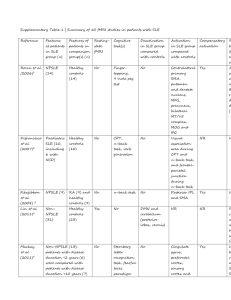

iTremble: A Case Report of Diffuse Peripheral Polyneuropathy secondary to Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Submitted to the Philippine College of Physicians Southern Mindanao Chapter Primary Author: Jose Paulo D. Pablo, RMT, MD First Year Resident Co-authors: Jamel Norden, MD, FPNA John Elmer Quilisadio, MD, FPCP, DPRA Department of Internal Medicine Davao Regional Medical Center Apokon, Tagum City ABSTRACT Synopsis Peripheral neuropathy are classified into those that primarily affect the cell body, myelin and the axon, such classification of peripheral neuropathies have distinct clinical and electrophysiologic features. In Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), about 2 to 27% of patients affected will develop a peripheral neuropathy, making the diagnosis a challenge. Clinical Presentation We report a case of 34 years old female initially presenting with numbness both upper and lower extremities which was described as an ascending tingling sensation starting on the fingertips and toes. This was then later followed with gait instability and involuntary writhing movement of the fingers and toes. During the course, patient developed a butterfly rash on the face. On examination, there’s noted athetoid-like movement of the distal fingers, with associated distal weakness of all extremities with loss of vibratory sense, proprioception and reflexes. EMG revealed severe, diffuse, predominantly axonal sensory polyneuropathy while the serology revealed an elevated ANA and dsDNA and a positive direct and indirect Coomb’s test. Diagnosis The patient fulfills the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics diagnostic criteria, which includes acute malar rash, non-scarring alopecia, and hemolytic anemia, and positive ANA and Anti dsDNA. Treatment and Outcome She initially received methylprednisolone pulse therapy (MPPT), then followed by cyclophosphamide infusions. She is maintaining Hydroxychloroquine, Mycophenolate mofetil, Vitamin D + Calcium, Ferrous sulfate and Venlafaxine. She is currently on the 6th cycle of cyclophosphamide infusion, noting disappearance of pseudo-athetosis and peripheral neuropathy, regained ability to walk unaided and resolution of facial rash. Significance and Recommendation The consideration of autoimmune disorders should always remain open in a patient presenting with signs of neuropathy. Diagnosis requires a thorough history and physical exam. Additional reports on similar cases can aid physicians in early identification of the disease. To our knowledge, there were no similar local case reports of patients with SLE initially presenting with polyneuropathy. INTRODUCTION Systemic lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune disease which organs and cells undergo damage initially mediated by tissue binding autoantibodies and immune complexes. It affects 20 to 150 per 100,000 women in the United States with 90% of patients seen are women of child bearing years; but people of all gender, ages and ethnic groups are susceptible to such a disease.1 The actual prevalence of SLE in the Philippines is still unknown. SLE may involve one or several organ systems, and overtime may manifest additional clinical findings. Systemic symptoms, particularly fatigue and myalgias/athralgias are present most of the time2. Approximately 85% of patients have either continuing active disease or one or more current flares of active disease annually, making permanent and complete remissions rare. However, a low-level disease activity on treatment such as low dose prednisone and/or hydroxychloroquine is achievable in 35% of patients. SLE demonstrates a 6% prevalence of peripheral neuropathy with 67% of the neuropathies attributable to SLE. The most common type of neuropathy was a sensory or sensorimotor axonal polyneuropathy3. To our knowledge, local data regarding rarity of presentation of peripheral neuropathy on SLE patients is still lacking. Case Presentation The patient’s condition started one year prior to admission, as an onset of diffuse joint pains to which the patient tolerated and sought no consult. Three months prior to admission, noted onset of bilateral upper extremity numbness described as tingling sensation over the fingertips. Two months prior to admission, there’s onset of lower extremity numbness, bilateral, starting distally the progressing proximally with associated gait instability. One month prior to admission, she noted new onset of athetoid like movement, bilateral, both upper and lower extremities. She sought consult at a private neurologist and was admitted for work up of polyneuropathy. Electromyography (EMG) was done noting absence of sensory responses for all nerves tested, right peroneal nerve compound motor action potential (CMAP) amplitude was low, left tibial nerve conduction velocity was slow, and early recruitment and abundance of myopathic muscle action potential on needle examination. The EMG impression revealed severe, diffuse and predominantly axonal and sensory polyneuropathy. At this point, the patient was given Venlafaxine for the polyneuropathy. During the course of the hospital stay, the patient developed a nonpruritic erythematous rash on her face distributed on the face forming a butterfly like pattern. Autoimmune diseases were entertained with a consideration of SLE. ANA and DsDNA titers were measured showing elevated results: 5.26 and >200 respectively. This is accompanied with a positive direct and indirect Coomb’s test and a negative CT scan of the cranium. In association with patient’s clinical manifestation, a diagnosis of diffuse peripheral polyneuropathy secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus was made. She was then referred to a rheumatologist for further management, after which methylprednisolone pulse therapy (MPPT) was administered. She was then scheduled cyclophosphamide (CYC) infusion and was discharged for the mean time with medications geared in controlling patient’s disease and pain (Prednisone, Calcium+Vitamin D, FeSO4 + Folic Acid, Venlafaxine). Three days after discharge, she followed up at the OPD, noting new onset fever and cough with exertional dyspnea. She was deferred for the scheduled cyclophosphamide indefinitely due to pneumonia. She was admitted for antibiotic coverage with Piperacillin+Tazobactam and Levofloxacin. Three days post antibiotic therapy, she was started on cyclophosphamide infusion and was discharged. She was advised for ophthalmology evaluation prior discharge in preparation for hydroxychloroquine treatment. She was advised to follow up every month for the next 6 months for CYC infusion, then quarterly for two years. Presently, a total of six cycles of cyclophosphamide infusion were already given. During the interim, no noted new oral ulcerations and rashes with improvement on patient’s neuropathic pain, gradually decreasing over time. She is now able to walk unaided, doing activities of daily living without interruption from pain, with complete resolution of pseudo athetosis of bilateral hands and feet. DISCUSSION Epidemiology Most patients with SLE are seen with their disease when they are between 15 to 64 years old. SLE also tends to be more severe in men compared to women. Late onset SLE (50> years old) is characterized to be more insidious onset, with a higher occurrence of serositis and pulmonary involvement and lower incidence of malar rash, photosensitivity, alopecia, Raynauds’ phenomenon, neuropsychiatric disease and nephritis4. Our case is a 34 year old female of Asian descent presenting with peripheral neuropathy and malar rash. Approach to the patient with considering peripheral neuropathy There are three main goals in approaching a patient with neuropathy: 1.) Identify the lesion, 2.) Identify the cause, and 3.) Determine the proper treatment. Localization of the lesion for our patient was done in a systematic manner. Clinical presentation such as presence of fasciculation, in the absence of Babinski sign isolates the patient’s lesion at the lower motor neuron. Loss of reflexes or hyporreflexia takes the lesion down to the spinal roots. Taking note of the character of weakness of the patient, which follows a glove or stocking distribution, the lesion is further isolated at the peripheral nerves. Absence of sensory sparing isolates the lesion only up to the peripheral nerves. Further investigation of the neuropathy, we find a typical pattern of symmetric distal sensory loss with distal weakness, which coincides with expected findings of patients with either idiopathic sensory polyneuropathy, metabolic disorders and systemic diseases. Knowing the pattern of neuropathy usually yields a positive diagnosis, 50% of the time. Further isolation of the problem at the level of the peripheral nerves can be further done by narrowing down the differential diagnosis. This can be done by using the flowchart presented in figure 1. In the case of the patient, diabetic neuropathy, mononeuropathy multiplex and myositis were entertained as differentials. Myositis was immediately ruled out on physical examination, noting no sensory sparing which is expected from myositis. To totally rule it out, EMG studies have to be done, and true enough the result of EMG is indicative of a diffuse polyneuropathy. This result of the EMG also rules out mononeuropathy multiplex, differentiating it from true polyneuropathy. Electrodiagnosis for this patient shows axonal degeneration. Chronicity of the disease was then reviewed, to which the patient belongs to the sub-acute phase. We were then pointed out to intoxications and systemic diseases, to which SLE is of special interest due to history of joint pains and presentation of non-scarring alopecia and facial rash with the presence of positive immunologic markers (ANA, anti dsDNA). Figure 1: Approach to the evaluation of a patient with neuropathy Treatment Therapeutic strategies should aim at reducing overall burden of systemic inflammation and achieving such requires (1) accurate assessment of disease activity and flares, (2) stratification of patients according to severity of target organ involvement, (3) use of safe and effective drugs to induce remission promptly and prevent flares, and (4) prevention and management of disease and treatmentrelated comorbidities.5 In general, patients with mild lupus manifestations are treated with anti-malarials or diseasemodifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), alone or in combination with low-dose oral glucocorticoids (GCs) which we also gave to our patient. Severe SLE with major organ involvement requires an initial period of intensive immuno-suppressive therapy (induction therapy) to control aberrant immunologic activity and halt tissue injury, followed by a longer period of less intensive and less toxic maintenance therapy, to consolidate remission and prevent flares. MPPT 1g once daily for three days was given as the induction treatment for our patient. Moreover, the following were given as maintenance medication for our patient: Prednisone which is a glucocorticoid that exerts its inhibitory effects on immune responses mediated by T and B cells, Mycophenolate mofetil which is a potent inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase that is indispensable for the denovo-synthesis of guanosine nucleotides, Hydroxychloroquine which is an antimalarial drug that is usually given as an adjuvant treatment for achieving remission in which the action is still poorly understood, and Cyclophosphamide infusions which is an alkylating agent that depletes lymphocytes and reduce production of autoantibodies Prognosis Patients with SLE experience poor quality of life which is only in part associated with disease activity and organ damage. Important contributors include fatigue, fibromyalgia, depression, and cognitive dysfunction.6,7 Physicians should regularly address these issues and engage symptomatic or remedial therapies as indicated. Those presenting with neurologic symptoms such as neuropathies are usually rare and usually manifests as the disease evolves. Immunosuppressive treatment is beneficial for SLE patients with neuropathy but is less likely to be effective those presenting with generalized sensory or sensorimotor polyneuropathy without evidence of vasculitis. Conclusion Work up and evaluation of a patient with neuropathy requires a thorough history and neurological examination. Knowing the pattern of neuropathic disorders can point to the direction of the diagnosis and should be considered at all times in the diagnosis of the neuropathy. Laboratories and ancillary procedures should be focused in identifying the primary medical condition. A multi-disciplinary team is warranted to holistically manage patients with this rare disease. REFERENCES 1. Teruel M , Alarcon-Riquelme ME: The genetic basis of systemic lupus erythematosus: What are the risk factors and what have we learned. J Autoimmun 74:161,2016. 2. M Petri et al: Arthritis Rheum 64:2677, 2012 3. Oomatia A, Fang H, Petri M, et al: Peripheral neuropathies in systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical features, disease associations, and immunologic characteristics evaluated over a twenty-five year study period. Arthritis Rheum 66(4):1000–1009, 2014 4. Boddaert J, Huong DL, Amoura Z, et al: Late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a personal series of 47 patients and pooled analysis of 714 cases in the literature. Medicine 83:348–359, 2004. 5. Bertsias GK, Salmon JE, Boumpas DT: Therapeutic opportunities in systemic lupus erythematosus: state of the art and prospects for the new decade. Ann Rheum Dis 69(9):1603–1611, 2010. 6. Schmeding A, Schneider M: Fatigue, health-related quality of life and other patientreported outcomes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 27(3):363–375, 2013. 7. Zhu TY, Tam LS, Lee VW, et al: Relationship between flare and health-related quality of life in patients 37(3):568–573, 2010. with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol