CHILDREN, FAMILY & COMMUNITY

SEMESTER 1 EXAM NOTES

Nature of growth and development

Principles of development

Hereditary and Environmental:

… Physical characteristics are inherited; nutrition and learning are examples of environmental factors

… Predisposition to disease can be inherited, social responsibility, concern for others are examples of

environmental factors

Simple to complex:

… A child waves its arms before it grasps a toy

… Adolescents shift from using physical characteristics to describe themselves to using psychological

characteristics

Rate of growth and development varies:

… Developmental milestones are reached at different ages

… Elderly people cope differently with their decline in functioning

Critical periods:

… Establishing a strong emotional bond between a child and the primary caregiver is essential to the ability to

form relationships in later life

… When children leave home, parents develop new roles

Predictable sequence:

… Children sit before they walk

… Adults undergo social development as they learn to parent

Laying foundations with each stage and area of development:

… Emotional deprivation can lead to an infant not reaching their growth potential

… Isolation and loneliness in seniors can mean that they do not bother to look after their mental health

Cephalocaudal:

… Describes the progression of body control from the head to the lower parts of the body. For example, an

infant will achieve head, upper trunk and arm control before lower trunk and leg control.

Proximodistal:

… Describes progress from the central portions of the body (I.e. the spinal cord) to the distal or peripheral

parts. In this developmental progression, gross motor skills and competencies precede fine motor skills.

…

Domains of development

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT: is when the body changes in a physical manner. It can be the brain growing bigger,

the. head circumference increasing, the body getting heavier or longer, or the nails growing. It can be defined into

two categories – gross and fine motor

… Gross motor: is the development of larger skills and larger muscle movement such as walking, running,

skipping and jumping. These develop first

… Fine motor: is the development of smaller movements and more complicated skills. This can include

picking up small items with a pointer finger and thumb and how a pencil is held and coordinated. These

take longer to develop

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT: is how a person understands about the people around them and how to interact and

acceptable behaviour when interacting with others. It is also how a child observes others; talking to people, listening

to people and understanding when it is their turn to talk. It is about learning behaviours that are acceptable with

other people, what is discussed and what is not discussed.

EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT: is how a person feels. These emotions can be happiness, sadness, anger, love, hate,

fear or hope. A child learns about these emotions and how to express themselves, and what is appropriate and what

is not. For example, when a child is angry it is not acceptable to hit out at people. When you are happy, it is good to

smile and laugh; it can make you feel good.

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT: is how a child understands about the world. This is how thoughts come together but

it is influenced by the environment of the child and how the brain develops. An example of this can include where

milk comes from. Initially milk comes from their mothers’ breast or from a bottle. Then they learn that milk can

come from a shop and then that milk can come from a cow then milk can also come from goats and other animals, or

that there are variations, for example, soy milk.

SPIRTUAL/MORAL DEVELOPMENT: is how a person feels about themselves and their values. This can take a

while to develop and understand. It does not need to be a religious understanding but more of an awareness of what

they value in their life and what they want to achieve – their values. In the beginning this is shaped a great deal by

their environment and to what they are exposed. As their environment changes this influences this developmental

area – the experiences that they have, the consequences of their actions and how this has an impact on their life.

Piage’s Theory of Cognitive Development:

The sensorimotor stage is composed of six sub-stages and lasts from birth through 24 months. The six substages are

1. Reflexes: the first substage (first month of life) is the stage of reflex acts. The neonate responds to external

stimulation with innate reflex actions. For example, if you brush a baby’s mouth or cheek with your finger

it will suck reflexively.

2. Primary circular reactions: the second substage is the stage of primary circular reactions. The baby will

repeat pleasurable actions centered on its own body. For example, babies from 1 – 4 months old will wiggle

their fingers, kick their legs and suck their thumbs. These are not reflex actions. They are done intentionally

– for the sake of the pleasurable stimulation produced.

3. Secondary circular reactions: next comes the stage of secondary circular reactions. It typically lasts from

about 4 – 8 months. Now babies repeat pleasurable actions that involve objects as well as actions involving

their own bodies. An example of this is the infant who shakes the rattle for the pleasure of hearing the

sound that it produces.

4. Of reactions: the fourth substage (from 8 – 12 months) is the stage of coordinating secondary schemes.

Instead of simply prolonging interesting events, babies now show signs of an ability to use their acquired

knowledge to reach a goal. For example, the infant will not just shake the rattle, but will reach out and

knock to one side an object that stands in the way of it getting hold of the rattle.

5. Tertiary circular reactions: fifth comes the stage of tertiary circular reactions. These differ from

secondary circular reactions in that they are intentional adaptations to specific situations. The infant who

once explored an object by taking it apart now tries to put it back together. For example, it stacks the bricks

it took out of its wooden truck back again or it puts back the nesting cups – one inside the other.

6. Representational thought: Finally, in substage six there is the beginning of symbolic thought. This is

transitional to the pre operational stage of cognitive development. Babies can now form mental

representations of objects. This means that they have developed the ability to visualize things that are not

physically present. This is crucial to the acquisition of object permanence – the most fundamental

achievement of the whole sensorimotor stage of development

Object Permanence: The main development during the sensorimotor stage is the understanding that objects exist

and events occur in the world independently of one's own actions ('the object concept', or 'object permanence').

For example, if you place a toy under a blanket, the child who has achieved object permanence knows it is there and

can actively seek it. At the beginning of this stage the child behaves as if the toy had simply disappeared.

The attainment of object permanence generally signals the transition to the next stage of development

(preoperational).

The Preoperational Stage of Cognitive Development

The child's thinking during this stage is pre (before) operations. This means the child cannot use logic or transform,

combine or separate ideas the child's development consists of building experiences about the world through

adaptation and working towards the (concrete) stage when it can use logical thought. During the end of this stage

children can mentally represent events and objects (the semiotic function) and engage in symbolic play.

Centration is the tendency to focus on only one aspect of a situation at one time. When a child can focus on more

than one aspect of a situation at the same time, they have the ability to decenter.

During this stage children have difficulties thinking about more than one aspect of any situation at the same time;

and they have trouble decentering in social situation just as they do in non-social contexts.

EGOCENTRIC:

… Children’s' thoughts and communications are typically egocentric (i.e. about themselves). Egocentrism

refers to the child's inability to see a situation from another person's point of view.

… According to Piaget, the egocentric child assumes that other people see, hear, and feel exactly the same as

the child does.

PLAY:

… At the beginning of this stage you often find children engaging in parallel play. That is to say they often play

in the same room as other children, but they play next to others rather than with them.

… Each child is absorbed in its own private world and speech is egocentric. That is to say the main function of

speech at this stage is to externalize the child’s thinking rather than to communicate with others.

… As yet the child has not grasped the social function of either language or rules.

SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATION:

… The early preoperational period (ages 2-3) is marked by a dramatic increase in children’s use of the

symbolic function.

… This is the ability to make one thing - a word or an object - stand for something other than itself. Language

is perhaps the most obvious form of symbolism that young children display.

However, Piaget (1951) argues that language does not facilitate cognitive development, but merely reflects what the

child already knows and contributes little to new knowledge. He believed cognitive development promotes language

development, not vice versa.

PRETEND PLAY OR SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATION:

… Toddlers often pretend to be people they are not (e.g. superheroes, policeman), and may play these roles

with props that symbolize real life objects. Children may also invent an imaginary playmate.

… In symbolic play, young children advance upon their cognitions about people, objects and actions and in this

way construct increasingly sophisticated representations of the world' (Bornstein, 1996, p. 293).

… As the pre-operational stage develops egocentrism declines and children begin to enjoy the participation of

another child in their games and “let’s pretend” play becomes more important.

… For this to work there is going to be a need for some way of regulating each child’s relations with the other

and out of this need we see the beginnings of an orientation to others in terms of rules.

ANIMISM

… This is the belief that inanimate objects (such as toys and teddy bears) have human feelings and intentions.

By animism Piaget (1929) meant that for the pre-operational child the world of nature is alive, conscious

and has a purpose.

Piaget has identified four stages of animism:

1. Up to the ages 4 or 5 years, the child believes that almost everything is alive and has a purpose.

2. During the second stage (5-7 years) only objects that move have a purpose.

3. In the next stage (7-9 years), only objects that move spontaneously are thought to be alive.

4. In the last stage (9-12 years), the child understands that only plants and animals are alive.

ARTIFICIALISM:

… This is the belief that certain aspects of the environment are manufactured by people (e.g. clouds in the sky).

IRREVERSABILITY:

… This is the inability the reverse the direction of a sequence of events to their starting point.

Concrete Operational Stage

Piaget considered the concrete stage a major turning point in the child's cognitive development, because it marks the

beginning of logical or operational thought. The child is now mature enough to use logical thought or operations (i.e.

rules) but can only apply logic to physical objects (hence concrete operational).

Children gain the abilities of conservation (number, area, volume, orientation), reversibility, seriation, transitivity

and class inclusion However, although children can solve problems in a logical fashion, they are typically not able to

think abstractly or hypothetically.

CONSERVATION:

… Conservation is the understanding that something stays the same in

quantity even though its appearance changes. To be more technical

conservation is the ability to understand that redistributing material

does not affect its mass, number, volume or length.

CLASSIFICATION:

… Piaget also studied children's ability to classify objects – put them

together on the basis of their colour, shape etc.

… Classification is the ability to identify the properties of categories, to

relate categories or classes to one another, and to use categorical

information to solve problems.

… One component of classification skills is the ability to group objects according to some dimension that they

share. The other ability to is order subgroups hierarchically, so that each new grouping will include all

share. The other ability to is order subgroups hierarchically, so that each new grouping will include all

previous subgroups.

… For example, he found that children in the pre-operational stage had difficulty in understanding that a class

can include a number of sub-classes. For example, a child is shown four red flowers and two white ones

and is asked 'are there more red flowers or more flowers?'. A typical five-year-old would say 'more red

ones'.

SERIATION:

… The cognitive operation of seriation (logical order) involves the ability to mentally arrange items along a

quantifiable dimension, such as height or weight.

… Formal Operational Stage

… The formal operational stage begins at approximately age twelve and lasts into adulthood. As adolescents

enter this stage, they gain the ability to think in an abstract manner by manipulate ideas in their head,

without any dependence on concrete manipulation.

… He/she can do mathematical calculations, think creatively, use abstract reasoning, and imagine the outcome

of particular actions.

… An example of the distinction between concrete and formal operational stages is the answer to the question

“If Kelly is taller than Ali and Ali is taller than Jo, who is tallest?” This is an example of inferential

reasoning, which is the ability to think about things which the child has not actually experienced and to

draw conclusions from its thinking.

HYPOTHETICO DEDUCTIVE:

… Reasoning is the ability to think scientifically through generating predictions, or hypotheses, about the world

to answer questions. The individual will approach problems in a systematic and organised manner, rather

than through trial-and-error.

ABSTRACT THOUGHT:

… Concrete operations are carried out on things whereas formal operations are carried out on ideas. The

individual can think about hypothetical and abstract concepts they have yet to experience. Abstract thought

is important for planning regarding the future.

Theories of development

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs:

PSYCHOLOGICAL NEEDS: these are biological requirements for human survival, e.g. air, food, drink, shelter,

clothing, warmth, sex, sleep.

… If these needs are not satisfied the human body cannot function optimally. Maslow considered physiological

needs the most important as all the other needs become secondary until these needs are met.

SAFETY NEEDS: protection from elements,

security, order, law, stability, freedom from fear.

BELONGINGNESS AND LOVE NEEDS: after

physiological and safety needs have been

fulfilled, the third level of human needs is social

and involves feelings of belongingness. The need

for interpersonal relationships motivates

behaviour.

… Examples include friendship, intimacy,

trust, and acceptance, receiving and

giving affection and love. Affiliating,

being part of a group (family, friends,

work).

ESTEEM NEEDS: which Maslow classified into

two categories:

… esteem for oneself (dignity, achievement, mastery, independence)

… the desire for reputation or respect from others (e.g., status, prestige).

Maslow indicated that the need for respect or reputation is most important for children and adolescents and precedes

real self-esteem or dignity.

SELF-ACTUALIZATION: realizing personal potential, self-fulfilment, seeking personal growth and peak

experiences. A desire “to become everything one is capable of becoming”

Applying: The first priority of workers is their survival. It's hard for them to be motivated if their pay is unfair and

if their jobs are always in jeopardy. Generally, a person beginning their career will be very concerned with

physiological needs such as adequate wages and stable income and security needs such as benefits and a safe work

environment. We all want a good salary to meet the needs of our family and we want to work in a stable

environment. Once these basic needs are met, the employee will want his "belongingness" (or social) needs met. The

environment. Once these basic needs are met, the employee will want his "belongingness" (or social) needs met. The

level of social interaction an employee desires will vary based on whether the employee is an introvert or extrovert.

The key point is that employees desire to work in an environment where they are accepted in the organization and

have some interaction with others. This means effective interpersonal relations are necessary. Managers can create

an environment where staff cooperation is rewarded. This will encourage interpersonal effectiveness. With these

needs satisfied, an employee will want his higher-level needs of esteem and self-actualization met. Esteem needs are

tied to an employee’s image of himself and his desire for the respect and recognition of others. Even if an individual

does not want to move into management, he probably does not want to do the same exact work for 20 years. He may

want to be on a project team, complete a special task, learn other tasks or duties, or expand his duties in some

manner. Cross-training, job enrichment, and special assignments are popular methods for making work more

rewarding. Further, allowing employees to participate in decision making on operational matters is a powerful

method for meeting an employee’s esteem needs. Finally, symbols of accomplishment such as a meaningful job title,

job perks, awards, a nice office, business cards, work space, etc. are also important to an employee’s esteem. Finally,

while work assignments and rewards are important considerations to meeting employee esteem needs, workplace

fairness (equity) is also important. With self-actualization, the employee will be interested in growth and individual

development. He will also need to be skilled at what he does. He may want a challenging job, an opportunity to

complete further education, increased freedom from supervision, or autonomy to define his own processes for

meeting organizational objectives. At this highest level, managers focus on promoting an environment where an

employee can meet his own self-actualization needs.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological System:

MICROSYSTEM: The microsystem is the smallest and most

immediate environment in which the child lives. As such,

the microsystem comprises the daily home, school or daycare, peer group or community environment of the child.

Interactions within the microsystem typically involve

personal relationships with family members, classmates,

teachers and caregivers, in which influences go back and

forth. How these groups or individuals interact with the

child will affect how the child grows. Similarly, how the

child reacts to people in his microsystem will also influence

how they treat the child in return. More nurturing and more

supportive interactions and relationships will

understandably foster the child’s improved development.

Each child’s particular personality traits, such as temperament, which is influenced by unique genetic and biological

factors, ultimately have a hand in how he is treated by others.

MESOSYSTEM: The mesosystem encompasses the interaction of the different microsystems which the developing

child finds himself in. It is, in essence, a system of microsystems and as such, involves linkages between home and

school, between peer group and family, or between family and church. If a child’s parents are actively involved in

the friendships of their child, invite friends over to their house and spend time with them, then the child’s

development is affected positively through harmony and like-mindedness. However, if the child’s parents dislike

their child’s peers and openly criticize them, then the child experiences disequilibrium and conflicting emotions,

probably affecting his development negatively.

EXOSYSTEM: The exosystem pertains to the linkages that may exist between two or more settings, one of which

may not contain the developing child but affects him indirectly, nonetheless. Other people and places which the

child may not directly interact with but may still have an effect on the child, comprise the exosystem. Such places

and people may include the parents’ workplaces, the larger neighbourhood, and extended family members.

For example, a father who is continually passed up for promotion by an indifferent boss at the workplace may take it

out on his children and mistreat them at home.

MACROSYSTEM: The macrosystem is the largest and most distant collection of people and places to the child that

still exercises significant influence on the child. It is composed of the child’s cultural patterns and values,

specifically the child’s dominant beliefs and ideas, as well as political and economic systems. Children in war-torn

areas, for example, will experience a different kind of development than children in communities where peace

reigns.

CHRONOSYSTEM: The chronosystem adds the useful dimension of time, which demonstrates the influence of both

change and constancy in the child’s environment. The chronosystem may thus include a change in family structure,

address, parent’s employment status, in addition to immense society changes such as economic cycles and wars. For

example, a child who frequently bullies smaller children at school may portray the role of a terrified victim at home.

Due to these variations, adults concerned with the care of a particular child should pay close attention to behaviour

in different settings or contexts and to the quality and type of connections that exist between these contexts.

Interrelationships (impact, consequences, influences): every section in the Bronfenbrenner theory revolves

Interrelationships (impact, consequences, influences): every section in the Bronfenbrenner theory revolves

around the child, if one section is influenced there are high chances that one or more of another section will be

influenced too. For example, if a parent loses a job and can’t afford much the child environment will change

(exosystem), their relationship with parents will change because the parents’ attitude will change (microsystem), the

parent may not be able to afford extra-curricular sporting teams influencing the child (mesosystem).

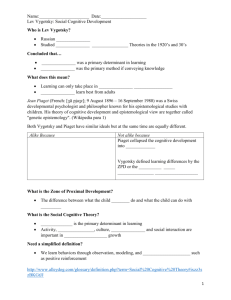

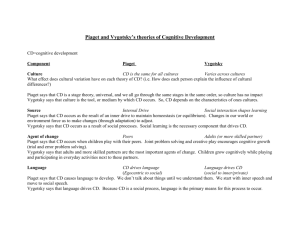

Vygotsky:

… Vygotsky has developed a sociocultural approach to cognitive development. He developed his theories at

around the same time as Jean Piaget was starting to develop his ideas (1920's and 30's), but he died at the

age of 38, and so his theories are incomplete - although some of his writings are still being translated from

Russian.

… No single principle (such as Piaget's equilibration) can account for development. Individual development

cannot be understood without reference to the social and cultural context within which it is embedded.

Higher mental processes in the individual have their origin in social processes.

Vygotsky's theory differs from that of Piaget in a number of important ways:

1: Vygotsky places more emphasis on culture affecting cognitive development.

… This contradicts Piaget's view of universal stages and content of development (Vygotsky does not refer to

stages in the way that Piaget does).

… Hence Vygotsky assumes cognitive development varies across cultures, whereas Piaget states cognitive

development is mostly universal across cultures.

2: Vygotsky places considerably more emphasis on social factors contributing to cognitive development.

… Vygotsky states cognitive development stems from social interactions from guided learning within the zone

of proximal development as children and their partner's co-construct knowledge. In contrast, Piaget

maintains that cognitive development stems largely from independent explorations in which children

construct knowledge of their own.

… For Vygotsky, the environment in which children grow up will influence how they think and what they think

about.

3: Vygotsky places more (and different) emphasis on the role of language in cognitive development.

… According to Piaget, language depends on thought for its development (i.e., thought comes before

language). For Vygotsky, thought and language are initially separate systems from the beginning of life,

merging at around three years of age, producing verbal thought (inner speech).

… For Vygotsky, cognitive development results from an internalization of language.

4: According to Vygotsky adults are an important source of cognitive development.

… Adults transmit their culture's tools of intellectual adaptation that children internalize. In contrast, Piaget

emphasizes the importance of peers as peer interaction promotes social perspective taking.

Effects of Culture: - Tools of intellectual adaptation

Like Piaget, Vygotsky claimed that infants are born with the basic materials/abilities for intellectual development Piaget focuses on motor reflexes and sensory abilities.

Lev Vygotsky refers to 'elementary mental functions' –

… Attention

… Sensation

… Perception

… Memory

… Eventually, through interaction within the sociocultural environment, these are developed into more

sophisticated and effective mental processes/strategies which he refers to as 'higher mental functions.'

sophisticated and effective mental processes/strategies which he refers to as 'higher mental functions.'

… For example, memory in young children this is limited by biological factors. However, culture determines

the type of memory strategy we develop. E.g., in our culture, we learn note-taking to aid memory, but in

pre-literate societies, other strategies must be developed, such as tying knots in a string to remember, or

carrying pebbles, or repetition of the names of ancestors until large numbers can be repeated.

… Vygotsky refers to tools of intellectual adaptation - these allow children to use the basic mental functions

more effectively/adaptively, and these are culturally determined (e.g., memory mnemonics, mind maps).

… Vygotsky, therefore, sees cognitive functions, even those carried out alone, as affected by the beliefs, values,

and tools of intellectual adaptation of the culture in which a person develops and therefore socio-culturally

determined. The tools of intellectual adaptation, therefore, vary from culture to culture - as in the memory

example.

Social Influences on Cognitive Development

… Like Piaget, Vygotsky believes that young children are curious and actively involved in their own learning

and the discovery and development of new understandings/schema. However, Vygotsky placed more

emphasis on social contributions to the process of development, whereas Piaget emphasized self-initiated

discovery.

… According to Vygotsky (1978), much important learning by the child occurs through social interaction with

a skillful tutor. The tutor may model behaviors and/or provide verbal instructions for the child. Vygotsky

refers to this as cooperative or collaborative dialogue. The child seeks to understand the actions or

instructions provided by the tutor (often the parent or teacher) then internalizes the information, using it to

guide or regulate their own performance.

… Shaffer (1996) gives the example of a young girl who is given her first jigsaw. Alone, she performs poorly

in attempting to solve the puzzle. The father then sits with her and describes or demonstrates some basic

strategies, such as finding all the corner/edge pieces and provides a couple of pieces for the child to put

together herself and offers encouragement when she does so.

… As the child becomes more competent, the father allows the child to work more independently. According to

Vygotsky, this type of social interaction involving cooperative or collaborative dialogue promotes cognitive

development.

… In order to gain an understanding of Vygotsky's theories on cognitive development, one must understand

two of the main principles of Vygotsky's work: the More Knowledgeable Other (MKO) and the Zone of

Proximal Development (ZPD).

More Knowledgeable Other

… The more knowledgeable other (MKO) is somewhat self-explanatory; it refers to someone who has a better

understanding or a higher ability level than the learner, with respect to a particular task, process, or

concept.

… Although the implication is that the MKO is a teacher or an older adult, this is not necessarily the case.

Many times, a child's peers or an adult's children may be the individuals with more knowledge or

experience.

… For example, who is more likely to know more about the newest teenage music groups, how to win at the

most recent PlayStation game, or how to correctly perform the newest dance craze - a child or their

parents?

… In fact, the MKO need not be a person at all. Some companies, to support employees in their learning

process, are now using electronic performance support systems.

… Electronic tutors have also been used in educational settings to facilitate and guide students through the

learning process. The key to MKOs is that they must have (or be programmed with) more knowledge about

the topic being learned than the learner does.

Zone of Proximal Development

… The concept of the More Knowledgeable Other is integrally related to the second important principle of

Vygotsky's work, the Zone of Proximal Development.

… This is an important concept that relates to the difference between what a child can achieve independently

… This is an important concept that relates to the difference between what a child can achieve independently

and what a child can achieve with guidance and encouragement from a skilled partner.

… For example, the child could not solve the jigsaw puzzle (in the example above) by itself and would have

taken a long time to do so (if at all), but was able to solve it following interaction with the father, and has

developed competence at this skill that will be applied to future jigsaws.

… Vygotsky (1978) sees the Zone of Proximal Development as the area where the most sensitive instruction or

guidance should be given - allowing the child to develop skills they will then use on their own - developing

higher mental functions.

… Vygotsky also views interaction with peers as an effective way of developing skills and strategies. He

suggests that teachers use cooperative learning exercises where less competent children develop with help

from more skillful peers - within the zone of proximal development.

Evidence for Vygotsky and the ZPD

… Freund (1990) conducted a study in which children had to decide which items of furniture should be placed

in particular areas of a dolls house.

… Some children were allowed to play with their mother in a similar situation before they attempted it alone

(zone of proximal development) while others were allowed to work on this by themselves (Piaget's

discovery learning).

… Freund found that those who had previously worked with their mother (ZPD) showed the greatest

improvement compared with their first attempt at the task. The conclusion being that guided learning

within the ZPD led to greater understanding/performance than working alone (discovery learning).

Vygotsky and Language

… Vygotsky believed that language develops from social interactions, for communication purposes. Vygotsky

viewed language as man’s greatest tool, a means for communicating with the outside world.

… According to Vygotsky (1962) language plays two critical roles in cognitive development:

… 1: It is the main means by which adults transmit information to children.

… 2: Language itself becomes a very powerful tool of intellectual adaptation.

… Vygotsky (1987) differentiates between three forms of language: social speech which is external

communication used to talk to others (typical from the age of two); private speech (typical from the age of

three) which is directed to the self and serves an intellectual function; and finally private speech goes

underground, diminishing in audibility as it takes on a self-regulating function and is transformed into silent

inner speech (typical from the age of seven).

… For Vygotsky, thought and language are initially separate systems from the beginning of life, merging at

around three years of age. At this point speech and thought become interdependent: thought becomes

verbal, speech becomes representational. When this happens, children's monologues internalized to become

inner speech. The internalization of language is important as it drives cognitive development.

… 'Inner speech is not the interior aspect of external speech - it is a function in itself. It still remains speech,

i.e., thought connected with words. But while in external speech thought is embodied in words, in inner

speech words dies as they bring forth thought. Inner speech is to a large extent thinking in pure meanings.'

… (Vygotsky, 1962: p. 149)

… Vygotsky (1987) was the first psychologist to document the importance of private speech. He considered

private speech as the transition point between social and inner speech, the moment in development where

language and thought unite to constitute verbal thinking.

… Thus, private speech, in Vygotsky's view, was the earliest manifestation of inner speech. Indeed, private

speech is more similar (in its form and function) to inner speech than social speech.

… Private speech is 'typically defined, in contrast to social speech, as speech addressed to the self (not to

others) for the purpose of self-regulation (rather than communication).'

… (Diaz, 1992, p.62)

… Unlike inner speech which is covert (i.e., hidden), private speech is overt. In contrast to Piaget’s (1959)

notion of private speech representing a developmental dead-end, Vygotsky (1934, 1987) viewed private

speech as:

… 'A revolution in development which is triggered when preverbal thought and preintellectual language come

together to create fundamentally new forms of mental functioning.'

… (Fernyhough & Fradley, 2005: p. 1).

… In addition to disagreeing on the functional significance of private speech, Vygotsky and Piaget also offered

opposing views on the developmental course of private speech and the environmental circumstances in

which it occurs most often (Berk & Garvin, 1984).

… Through private speech, children begin to collaborate with themselves in the same way a more

knowledgeable other (e.g., adults) collaborate with them in the achievement of a given function.

… Vygotsky sees "private speech" as a means for children to plan activities and strategies and therefore aid

their development. Private speech is the use of language for self-regulation of behavior. Language is,

therefore, an accelerator to thinking/understanding (Jerome Bruner also views language in this way).

Vygotsky believed that children who engaged in large amounts of private speech are more socially

competent than children who do not use it extensively.

… Vygotsky (1987) notes that private speech does not merely accompany a child’s activity but acts as a tool

used by the developing child to facilitate cognitive processes, such as overcoming task obstacles, enhancing

imagination, thinking, and conscious awareness.

… Children use private speech most often during intermediate difficulty tasks because they are attempting to

self-regulate by verbally planning and organizing their thoughts (Winsler et al., 2007).

… The frequency and content of private speech are then correlated with behavior or performance. For example,

private speech appears to be functionally related to cognitive performance: It appears at times of difficulty

with a task.

… For example, tasks related to executive function (Fernyhough & Fradley, 2005), problem-solving tasks

(Behrend et al., 1992), schoolwork in both language (Berk & Landau, 1993), and mathematics (Ostad &

Sorensen, 2007).

… Berk (1986) provided empirical support for the notion of private speech. She found that most private speech

exhibited by children serves to describe or guide the child's actions.

… Berk also discovered than child engaged in private speech more often when working alone on challenging

tasks and also when their teacher was not immediately available to help them. Furthermore, Berk also

found that private speech develops similarly in all children regardless of cultural background.

… Vygotsky (1987) proposed that private speech is a product of an individual’s social environment. This

hypothesis is supported by the fact that there exist high positive correlations between rates of social

interaction and private speech in children.

… Children raised in cognitively and linguistically stimulating environments (situations more frequently

observed in higher socioeconomic status families) start using and internalizing private speech faster than

children from less privileged backgrounds. Indeed, children raised in environments characterized by low

verbal and social exchanges exhibit delays in private speech development.

… Children’s’ use of private speech diminishes as they grow older and follows a curvilinear trend. This is due

to changes in ontogenetic development whereby children are able to internalize language (through inner

speech) in order to self-regulate their behavior (Vygotsky, 1987).

… For example, research has shown that children’s’ private speech usually peaks at 3–4 years of age, decreases

at 6–7 years of age, and gradually fades out to be mostly internalized by age 10 (Diaz, 1992).

… Vygotsky proposed that private speech diminishes and disappears with age not because it becomes

socialized, as Piaget suggested, but rather because it goes underground to constitute inner speech or verbal

thought” (Frauenglass & Diaz, 1985).

Classroom Applications

… A contemporary educational application of Vygotsky's theories is "reciprocal teaching," used to improve

students' ability to learn from text. In this method, teachers and students collaborate in learning and

practicing four key skills: summarizing, questioning, clarifying, and predicting. The teacher's role in the

process is reduced over time.

… Also, Vygotsky is relevant to instructional concepts such as "scaffolding" and "apprenticeship," in which a

teacher or more advanced peer helps to structure or arrange a task so that a novice can work on it

successfully.

successfully.

… Vygotsky's theories also feed into the current interest in collaborative learning, suggesting that group

members should have different levels of ability so more advanced peers can help less advanced members

operate within their ZPD.

Critical Evaluation

… Vygotsky's work has not received the same level of intense scrutiny that Piaget's has, partly due to the timeconsuming process of translating Vygotsky's work from Russian. Also, Vygotsky's sociocultural perspective

does not provide as many specific hypotheses to test as did Piaget's theory, making refutation difficult, if

not impossible.

… Perhaps the main criticism of Vygotsky's work concerns the assumption that it is relevant to all cultures.

Rogoff (1990) dismisses the idea that Vygotsky's ideas are culturally universal and instead states the

concept of scaffolding - which is heavily dependent on verbal instruction - may not be equally useful in all

cultures for all types of learning. Indeed, in some instances, observation and practice may be more effective

ways of learning certain skills.

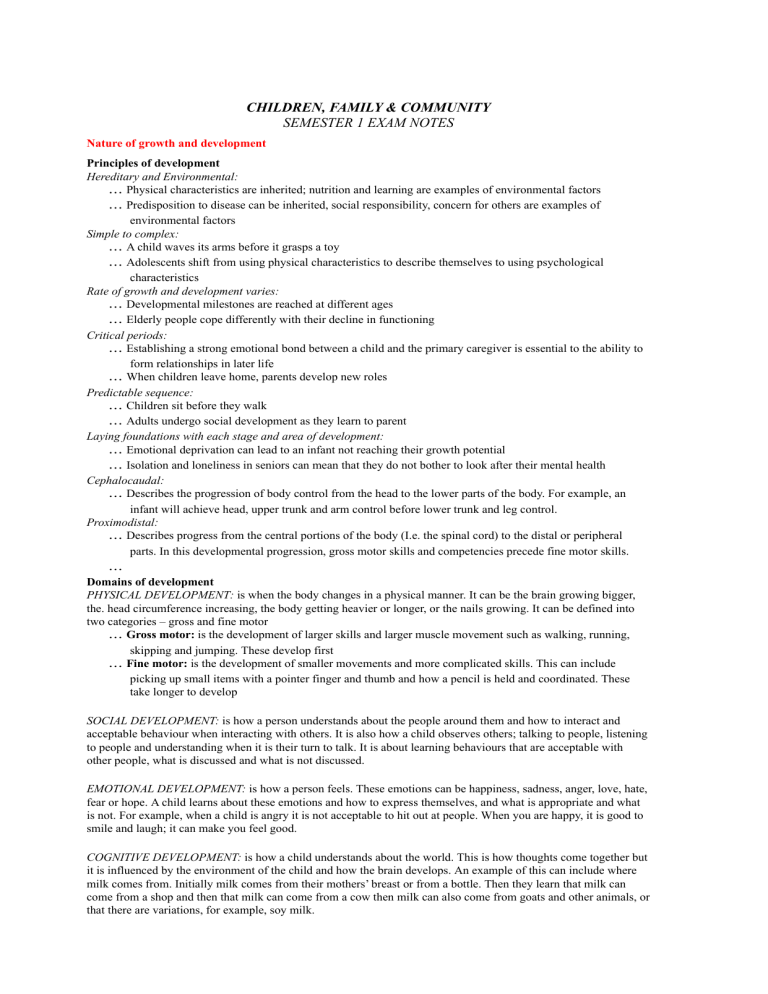

Erik Erikson:

… Erikson maintained that personality develops in a predetermined order through eight stages of psychosocial

development, from infancy to adulthood. During each stage, the person experiences a psychosocial crisis

which could have a positive or negative outcome for personality development.

… For Erikson (1958, 1963), these crises are of a psychosocial nature because they involve psychological

needs of the individual (i.e., psycho) conflicting with the needs of society (i.e., social).

… According to the theory, successful completion of each stage results in a healthy personality and the

acquisition of basic virtues. Basic virtues are characteristic strengths which the ego can use to resolve

subsequent crises.

… Failure to successfully complete a stage can result in a reduced ability to complete further stages and

therefore an unhealthier personality and sense of self. These stages, however, can be resolved successfully

at a later time.

Stage

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Psychosocial Crisis

Trust vs. Mistrust

Autonomy vs. Shame

Initiative vs. Guilt

Industry vs. Inferiority

Identity vs. Role Confusion

Intimacy vs. Isolation

Generativity vs. Stagnation

Ego Integrity vs. Despair

Basic Virtue

Hope

Will

Purpose

Competency

Fidelity

Love

Care

Wisdom

Age

0 - 1½

1½ - 3

3-5

5 - 12

12 - 18

18 - 40

40 - 65

65+

1. Trust vs. Mistrust

… Trust vs. mistrust is the first stage in Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial development. This stage begins

at birth continues to approximately 18 months of age. During this stage, the infant is uncertain about the

world in which they live and looks towards their primary caregiver for stability and consistency of care.

… If the care the infant receives is consistent, predictable and reliable, they will develop a sense of trust which

will carry with them to other relationships, and they will be able to feel secure even when threatened.

… If these needs are not consistently met, mistrust, suspicion, and anxiety may develop.

… If the care has been inconsistent, unpredictable and unreliable, then the infant may develop a sense of

mistrust, suspicion, and anxiety. In this situation the infant will not have confidence in the world around

them or in their abilities to influence events.

… Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of hope. By developing a sense of trust, the infant can have hope

that as new crises arise, there is a real possibility that other people will be there as a source of support.

Failing to acquire the virtue of hope will lead to the development of fear.

… This infant will carry the basic sense of mistrust with them to other relationships. It may result in anxiety,

heightened insecurities, and an over feeling of mistrust in the world around them.

… Consistent with Erikson's views on the importance of trust, research by Bowlby and Ainsworth has outlined

how the quality of the early experience of attachment can affect relationships with others in later life.

2. Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt

… Autonomy versus shame and doubt is the second stage of Erik Erikson's stages of psychosocial

development. This stage occurs between the ages of 18 months to approximately 3 years. According to

Erikson, children at this stage are focused on developing a sense of personal control over physical skills

and a sense of independence.

… Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of will. If children in this stage are encouraged and supported in

their increased independence, they become more confident and secure in their own ability to survive in the

world.

… If children are criticized, overly controlled, or not given the opportunity to assert themselves, they begin to

feel inadequate in their ability to survive, and may then become overly dependent upon others, lack selfesteem, and feel a sense of shame or doubt in their abilities.

What Happens During This Stage?

… The child is developing physically and becoming more mobile, and discovering that he or she has many

skills and abilities, such as putting on clothes and shoes, playing with toys, etc. Such skills illustrate the

child's growing sense of independence and autonomy.

… For example, during this stage children begin to assert their independence, by walking away from their

mother, picking which toy to play with, and making choices about what they like to wear, to eat, etc.

What Can Parents Do to Encourage a Sense of Control?

… Erikson states it is critical that parents allow their children to explore the limits of their abilities within an

encouraging environment which is tolerant of failure.

… For example, rather than put on a child's clothes a supportive parent should have the patience to allow the

child to try until they succeed or ask for assistance. So, the parents need to encourage the child to become

more independent while at the same time protecting the child so that constant failure is avoided.

… A delicate balance is required from the parent. They must try not to do everything for the child, but if the

child fails at a particular task they must not criticize the child for failures and accidents (particularly when

toilet training).

… The aim has to be “self-control without a loss of self-esteem” (Gross, 1992).

3. Initiative vs. Guilt

… Initiative versus guilt is the third stage of Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial development. During the

initiative versus guilt stage, children assert themselves more frequently.

… These are particularly lively, rapid-developing years in a child’s life. According to Bee (1992), it is a “time

of vigour of action and of behaviours that the parents may see as aggressive."

… During this period the primary feature involves the child regularly interacting with other children at school.

Central to this stage is play, as it provides children with the opportunity to explore their interpersonal skills

through initiating activities.

… Children begin to plan activities, make up games, and initiate activities with others. If given this

opportunity, children develop a sense of initiative and feel secure in their ability to lead others and make

decisions.

Children Playing

… Conversely, if this tendency is squelched, either through criticism or control, children develop a sense of

guilt. The child will often overstep the mark in his forcefulness, and the danger is that the parents will tend

to punish the child and restrict his initiatives too much.

… It is at this stage that the child will begin to ask many questions as his thirst for knowledge grows. If the

parents treat the child’s questions as trivial, a nuisance or embarrassing or other aspects of their behaviour

as threatening then the child may have feelings of guilt for “being a nuisance”.

… Too much guilt can make the child slow to interact with others and may inhibit their creativity. Some guilt

is, of course, necessary; otherwise the child would not know how to exercise self-control or have a

conscience.

… A healthy balance between initiative and guilt is important. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of

purpose, while failure results in a sense of guilt.

4. Industry vs. Inferiority

… Erikson's fourth psychosocial crisis, involving industry (competence) vs. inferiority occurs during childhood

between the ages of five and twelve.

… Children are at the stage where they will be learning to read and write, to do sums, to do things on their

own. Teachers begin to take an important role in the child’s life as they teach the child specific skills.

… It is at this stage that the child’s peer group will gain greater significance and will become a major source of

the child’s self-esteem. The child now feels the need to win approval by demonstrating specific

competencies that are valued by society and begin to develop a sense of pride in their accomplishments.

… If children are encouraged and reinforced for their initiative, they begin to feel industrious (competent) and

feel confident in their ability to achieve goals. If this initiative is not encouraged, if it is restricted by

parents or teacher, then the child begins to feel inferior, doubting his own abilities and therefore may not

reach his or her potential.

… If the child cannot develop the specific skill, they feel society is demanding (e.g., being athletic) then they

may develop a sense of inferiority.

… Some failure may be necessary so that the child can develop some modesty. Again, a balance between

competence and modesty is necessary. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of competence.

5. Identity vs. Role Confusion

… The fifth stage of Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial development is identity vs. role confusion, and it

occurs during adolescence, from about 12-18 years. During this stage, adolescents search for a sense of self

and personal identity, through an intense exploration of personal values, beliefs, and goals.

… During adolescence, the transition from childhood to adulthood is most important. Children are becoming

more independent, and begin to look at the future in terms of career, relationships, families, housing, etc.

The individual wants to belong to a society and fit in.

… The adolescent mind is essentially a mind or moratorium, a psychosocial stage between childhood and

adulthood, and between the morality learned by the child, and the ethics to be developed by the adult

(Erikson, 1963, p. 245)

… This is a major stage of development where the child has to learn the roles he will occupy as an adult. It is

during this stage that the adolescent will re-examine his identity and try to find out exactly who he or she is.

Erikson suggests that two identities are involved: the sexual and the occupational.

… According to Bee (1992), what should happen at the end of this stage is “a reintegrated sense of self, of what

one wants to do or be, and of one’s appropriate sex role”. During this stage the body image of the

adolescent changes.

… Erikson claims that the adolescent may feel uncomfortable about their body for a while until they can adapt

and “grow into” the changes. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of fidelity.

… Fidelity involves being able to commit one's self to others on the basis of accepting others, even when there

may be ideological differences.

… During this period, they explore possibilities and begin to form their own identity based upon the outcome

of their explorations. Failure to establish a sense of identity within society ("I don’t know what I want to be

when I grow up") can lead to role confusion. Role confusion involves the individual not being sure about

themselves or their place in society.

… In response to role confusion or identity crisis, an adolescent may begin to experiment with different

lifestyles (e.g., work, education or political activities).

… Also pressuring someone into an identity can result in rebellion in the form of establishing a negative

identity, and in addition to this feeling of unhappiness.

6. Intimacy vs. Isolation

… Intimacy versus isolation is the sixth stage of Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial development. This stage

takes place during young adulthood between the ages of approximately 18 to 40 yrs.

… During this period, the major conflict centres on forming intimate, loving relationships with other people.

… During this period, we begin to share ourselves more intimately with others. We explore relationships

leading toward longer-term commitments with someone other than a family member.

… Successful completion of this stage can result in happy relationships and a sense of commitment, safety, and

care within a relationship.

… Avoiding intimacy, fearing commitment and relationships can lead to isolation, loneliness, and sometimes

depression. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of love.

7. Generativity vs. Stagnation

… Generativity versus stagnation is the seventh of eight stages of Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial

development. This stage takes place during middle adulthood (ages 40 to 65 yrs.).

… Generativity refers to "making your mark" on the world through creating or nurturing things that will outlast

an individual.

… People experience a need to create or nurture things that will outlast them, often having mentees or creating

positive changes that will benefit other people.

… We give back to society through raising our children, being productive at work, and becoming involved in

community activities and organizations. Through generativity we develop a sense of being a part of the

community activities and organizations. Through generativity we develop a sense of being a part of the

bigger picture.

… Success leads to feelings of usefulness and accomplishment, while failure results in shallow involvement in

the world.

… By failing to find a way to contribute, we become stagnant and feel unproductive. These individuals may

feel disconnected or uninvolved with their community and with society as a whole. Success in this stage

will lead to the virtue of care.

8. Ego Integrity vs. Despair

… Ego integrity versus despair is the eighth and final stage of Erik Erikson’s stage theory of psychosocial

development. This stage begins at approximately age 65 and ends at death.

… It is during this time that we contemplate our accomplishments and can develop integrity if we see ourselves

as leading a successful life.

… Erikson described ego integrity as “the acceptance of one’s one and only life cycle as something that had to

be” (1950, p. 268) and later as “a sense of coherence and wholeness” (1982, p. 65).

… As we grow older (65+ yrs.) and become senior citizens, we tend to slow down our productivity and explore

life as a retired person.

… Erik Erikson believed if we see our lives as unproductive, feel guilty about our past, or feel that we did not

accomplish our life goals, we become dissatisfied with life and develop despair, often leading to depression

and hopelessness.

… Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of wisdom. Wisdom enables a person to look back on their life

with a sense of closure and completeness, and also accept death without fear.

… Wise people are not characterized by a continuous state of ego integrity, but they experience both ego

integrity and despair. Thus, late life is characterized by both integrity and despair as alternating states that

need to be balanced.

Critical Evaluation

… By extending the notion of personality development across the lifespan, Erikson outlines a more realistic

perspective of personality development (McAdams, 2001).

… Based on Erikson’s ideas, psychology has reconceptualized the way the later periods of life are viewed.

Middle and late adulthood are no longer viewed as irrelevant, because of Erikson, they are now considered

active and significant times of personal growth.

… Erikson’s theory has good face validity. Many people find that they can relate to his theories about various

stages of the life cycle through their own experiences.

… However, Erikson is rather vague about the causes of development. What kinds of experiences must people

have to successfully resolve various psychosocial conflicts and move from one stage to another? The theory

does not have a universal mechanism for crisis resolution.

Factors affecting development

Family Types and Structures in Contemporary Australian Society:

WHAT IS A FAMILY?

… A group consisting of two parents and their children living together as a unit

… A group of people who love, trust and care for each other – not always related by blood

ADOPTIVE FAMILY: Two parents who have adopted a child/children. Most common reason is if parents are unable

to conceive a child.

BLENDED/STEP FAMILY: a family consisting of a couple, the children they have had together, and their children

from previous relationships.

CHILDLESS FAMILY: a couple in a committed and caring relationship with no children. The couple may or may not

be married.

COMMUNAL FAMILY: a group of people who live together, share household duties but are not related by blood.

They don’t necessarily have to live together, they could be a sports team, close friend group etc.

EXTENDED FAMILY: comprises of a mother, father, children and relatives sharing a house or living in close

proximity to each other.

FOSTER FAMILY: these are families where a couple cares for a child that is not biologically their own.

NUCLEAR FAMILY: comprises of a mother, father and their children. The most common family structure.

SAME GENDER FAMILY: a couple of the same sex in a committed relationship with or without children.

SOLE PARENT FAMILY: a single parent family which comprises of a mother or father caring for a child or children.

The impact of change in family types and structures on the growth and development of individuals and

families:

Experiencing the death of a parent is traumatic at any age, but it's particularly harrowing for young children. With

the death of a parent, young children are deprived not only of the guidance and love that that parent would have

provided as the children grew up but also the sense of security that the parent's ongoing presence in the home would

have bestowed. More often than not, the child feels terribly vulnerable, especially when the death is accompanied by

a relocation of the family.

Because one of the two people the child counted on being with him and supporting him (in all aspects) until

adulthood is now gone, it's not at all unusual for the child to cling to the surviving parent. The child can easily

become quite concerned with this parent's health, afraid that, should the parent fail to take care of himself or herself,

the child will be without anyone to support him and be truly orphaned.

Although they may never fully go away, these feelings of vulnerability are often alleviated to some extent by the

grieving process, especially if the child's able to share this process with his surviving parent and siblings. In

situations where the surviving parent has great difficulty grieving the loss of his or her spouse and continuing to

function as a parent, it's not unusual for the child to try to step in and care for the parent. This role reversal, of

course, puts an undue and unfair burden on the child, while running the risk of stifling the child's ability to grieve

the loss. In families with many siblings, the oldest child may also try to care for and parent the younger children in

an attempt to lighten the load on the surviving parent.

Integrating the grief as you mature

The grief that accompanies the loss of a parent as a child (as opposed to such a loss as an adult) is made more

complex by the fact that the child has to integrate this loss into his life as part of growing up and becoming an adult.

As the child reaches different plateaus in his life and experiences the rites of passage that mark the transition from

childhood to adulthood (such as graduations, communion, bar mitzvah, getting a driver's license, and proms), he

does so without the parent. In the face of the parent's absence, more often than not, the event becomes another

opportunity to revisit the grief and another challenge to integrate it into the child's life.

The events that a child doesn't get to share with the lost parent don't stop with adulthood. As the child moves

through adulthood, several salient events are opportunities to revisit the grief. Chief among them are marriage

(especially for girls who've lost their dads and have to ask someone else to give them away during the ceremony)

and the births of grandchildren.

Reaching the age of your deceased parent

Perhaps the most salient milestone for a person who's lost a parent as a child is reaching the same age that the parent

was when she or he died. For many people who've experienced parental loss as a child, this birthday is the most

poignant they've ever experienced. It often touches off a whole new round of longing for and reminiscing over the

lost parent, but, more importantly, it also initiates intense soul-searching about the future.

The introspection that accompanies reaching the age of the deceased parent seems to be particularly true for people

who are the same gender as the parent who died. In this case, many reports genuine surprise that they've lived as

long as their deceased parents. Some report even doubting they'll live beyond the age at which the parent passed

away and feeling apprehension over their own imminent death. Even when this fear isn't present, they still wonder

about their futures and take the anniversary as an occasion for taking stock of their lives and questioning the

direction of the next stage of their lives.

Factors impacting on growth and development of individuals and families:

SOCIAL:

… the quality, type and extent of the social interactions in a child’s environments, impact on a child. The trust

between child and caregivers (Erikson) impact on how the child is able to social/interact with others and is

key to forming positive relationships with others. Parents and significant others modelling of values,

positive behaviours. Richness of socialization on language development.

… What happens when we are unable to form rich meaningful bonds with others?

… Social and emotional development and the formation of connections in the brain are assisted by the

formation of secure attachments to a nurturing carer. Stress results in high levels of steroid hormone called

cortisol, which effects metabolism and depresses the immune system, and when chronic, can even destroy

neurons associated with learning and memory. However, school age children who developed secure

attachments to their carers during infancy and early childhoods have been found to be more resilient when

forced with stress or trauma, and to display fewer problems in behavior.

CULTURAL:

… Culture refers to the ideas, beliefs and social behaviours of a group; customs refers to the usual behaviour;

and traditions refer to beliefs or behaviours passed from one generation to the next. Parenting involves

satisfying the needs, building relationships and promoting wellbeing of the dependent. When fulfilling

these roles, parents may be influenced by their culture, customs and traditions. Parents may be influenced

in their parenting practices due to culture as there are expected beliefs and behaviours they must follow in

order to be a member of the cultural group. For example, some cultures expect parents to follow

authoritarian parenting practices. Following the expectations means the family will be accepted in the

cultural community giving them a sense of belonging. Similarly, customs can influence parenting practices

as a family may follow the usual behaviours of their community, so the children learn the socially

acceptable rules and are comfortable following those. Parents would therefore set limits of behaviour that

are in keeping with customs. For example, it might be the custom to go to church every week and so the

parents will insist on this with their children. In some families, it can be customary for the extended family

to live in the same home and care for grandchildren which influences parenting as the grandparents take on

caring roles. Traditions can also play a part in parenting as they can impact on parenting roles taken. For

example, a father’s traditional responsibility was to provide financial support and discipline the child while

the mother raised the child and was responsible for domestic duties which is a clear impact on parenting.

Alternatively, parents who have immigrated may wish to retain ethnic traditions such as language and food

choices meaning they would follow parenting practices that promote these traditions.

ENVIRONMENTAL:

… Young children need a healthy physical environment in order to develop and thrive. It is vital for care givers

to provide suitable environments for children.

… Sufficient space

… Clean areas

… Appropriate health checks

… correct suitable supervision

… Our environment is changing – our family structure is changing due to major values of autonomy, intimacy,

aspiration and acceptance in our roles and this in turn impacts on our environments.

… Single parents are a more common family environment, with children living with their mother in 85% of

cases.

… As a result, mothers are employed outside the home and there has been a dramatic rise in center based child

care facilities (daycare centers).

… Strong supportive environments that richly promote learning, have a positive effect on stability of the child

but on their capacity to learn and succeed.

… Abusive and unsafe environments impact on all aspects of emotional development and formation of strong

relationships. The constant pressure of stress impacts on ability to remain at school and impacts on their

physical well-being.

… Environments that are located away from city resources can impact children on accessing services and

placing them at a disadvantage to other children. If a child has a disability and their environment is not

adequately set up to assist with their daily requirements this can impact on their learning and ability to

thrive.

ECONOMIC:

… Economic hardship can arise from drastic changes in circumstances – change from a nuclear family to a

single parent family. This can bring financial hardship and stress to all family members. The need for

government assistance (Centrelink for extra financial support can bring relief for an already stressed family.

… Lack of financial or economic security can impact on the delivery of basic needs including housing, food

(nutrition for school children can impact on concentration and learning ability and lack of nutrition can

impact on physical health or access to medical procedures including doctors and dentists)

POLITICAL:

… Political Government Parties and policies and laws can impact on families through their policies and

funding they provide for families.

… Government rebates, childcare options and laws for children.

… How the Government through their actions is able to protect and keep our communities safe.

… Extreme examples 1. The devastation of War and the impact of individuals and families in a country

… EXAMPLES

… Disability Act 1986

… Framework when working with people with disabilities, including respect, human worth, dignity, having the

same rights as others allowing people to realize their individual capacities for physical, emotional,

cognitive and spiritual development. Provides the right to access the type of accommodation and

…

…

…

…

…

…

employment that they believe is most appropriate and an environment free from neglect, abuse,

intimidation and exploitation

Children and Community Services Act 2004 (WA)

Provides protection for children

Includes mandatory reporting of abuse and neglect, ill treatment or is at risk of being ill-treated or exposed

or subjected to behavior that psychologically harms the child.

The paramount principle of the act is of the best interests of the child and endorses the importance of

involving children and young people in decision making (to the extent that their age and their maturity

enables) and to consult and seek the views of children on issues affecting their lives. Provides protective

options for children deemed to be at risk of maltreatment.

Policies promote growth and development by

Offering legal protection and safety to families and individual reducing conflict violence and abuse.

Children, Family and Community

Taking Action

Communicating and advocating

Primary & Secondary Sources:

PRIMARY SOURCES: People use original, first-hand accounts as building blocks to create stories from the past.

These accounts are called primary sources, because they are the first evidence of something happening, or being

thought or said.

Primary sources are created at the time of an event, or very soon after something has happened. These sources are

often rare or one-of-a-kind. However, some primary sources can also exist in many copies, if they were popular and

widely available at the time that they were created.

All of the following can be primary sources:

… Diaries

… Letters

… Photographs

… Art

… Maps

… Video and film

… Sound recordings

… Interviews

… Newspapers

… Magazines

… Published first-hand accounts, or stories

SECONDARY SOURCES: Second-hand, published accounts are called secondary sources. They are called secondary

sources because they are created after primary sources and they often use or talk about primary sources. Secondary

sources can give additional opinions (sometimes called bias) on a past event or on a primary source. Secondary

sources often have many copies, found in libraries, schools or homes.

All of the following can be secondary sources, if they tell of an event that happened a while ago:

… History textbooks

… Biographies

… Published stories

… Movies of historical events

… Art

… Music recordings

When Is a Primary Source Not a Primary Source?

… You may have noticed that some things are on both the lists of primary and secondary sources. This isn't a

mistake. The difference between a primary and secondary source is often determined by how they were

originally created and how you use them.

… Here's an example: a painting or a photograph is often considered a primary source, because paintings and

photographs can illustrate past events as they happened and people as they were at a particular time.

However, not all artworks and photographs are considered primary sources. Read on!

… C.W. Jeffery’s was a talented artist who painted many scenes from Canada's past. His paintings and

drawings show the War of 1812, the Rebellions of 1837-38 and many of Canada's explorers from the 1600s

and 1700s. But C.W. Jeffery’s lived from 1869-1951, so he never saw the subjects of these paintings!

Instead, he did a lot of research using primary sources to create his illustrations. Some people would argue

that his illustrations are not primary sources. Although they illustrate past events, they were created long

after the events they show, and they tell you more about C.W. Jeffery’s' own ideas and research.

… Other people would argue that C.W. Jeffery’s' paintings and drawings are primary sources. They would say

that his perspective, his bias, and the way he illustrated historical events are reflections of what he thought

and what he believed. If you use C.W. Jeffery’s' paintings to talk about him, or the world he lived in, then

they can also be primary sources.

Processes for meeting needs:

The functional, social, cultural and economic features of products, services or systems developed for

individuals and families to meet their needs

Functional factors

… What it does.

… The services it provides.

… Is it effective?

… How many rooms, size of building?

… Number of offices

Social factors

… Impact on the people of the community

… Internal issues – amongst the staff

… Sporting teams

… Family impacts

… Relates to people

… Are people satisfied with the service?

… Beliefs of the company, service

Financial Factors

… Money related issues

… Turn-over

… Advertising

… Support

… Profit/not for profit

… Funding

… Budgets

… Costs

Cultural factors

… Accepting of a variety of cultures

… Accommodating of other cultures e.g. allows kosher food

… Values

Environmental factors

… Impact on the environment e.g. chemicals to wash nappies

… Recycling

Managing and Collaborating

self-management skills to effectively use resources:

self-management skills to effectively use resources:

Self-management skills are those characteristics that help an employee to feel and be more productive in the

workplace. Such skills as problem solving, resisting stress, communicating clearly, managing time, strengthening

memory, and exercising often are all key examples of self-management skills.

1. Stress-Resistance

… The first and foremost skill of self-management refers to a personal ability to resist any stressful situations.

When you develop this self-management skill, you can avoid many mistakes that people usually make

when being stressed out.

… Because a stressful situation usually blocks our ability to think and make rational decisions, we can’t cope

even with the simplest tasks at the workplace, so our productivity goes down and we get frustrated. That’s

why you need to develop this ability in order to be a productive employee able to offer resistance to a

stressful situation.

2. Problem Solving

… The second self-management skill requires you to use your brain as a mechanism for making right

decisions. Even the hardest tasks and challenges can be efficiently handled if the mental process in your

head is always in progress. Problem solving requires you to operate facts and make right assumptions to

analyze the situation, review problems, and find effective solutions. Keeping your mind sober allows you to

take right decisions even in the toughest situations.

3. Communication

… The way how you can communicate information to others will determine your success. Communication is

one of the key self-management skills required for both personal development and career advancement.

… Being able to efficient communicate any information to other people means that you can share information

with the minimized possible distortion and in the fastest possible way. Productive employees always can

efficiently communicate with their colleagues and management because they comprehensively understand

the value of clearly and timely delivered information. So be sure you work on developing this skill for selfmanagement.

4. Time Management

… Producing expected results in a timely manner determines the success of our effort. Time management is an

extremely important self-management skill that makes an employee be more productive. There’s a great

variety of time management techniques that show you how to develop this skill for self-management. Just

use the web search to find plenty of them.

5. Memory

… An ability to memorize events, names, facts, etc., allows an employee to remember about everything he/she

needs to do daily tasks and duties. Among other self-management skills examples, committing to memory

requires your personal effort for developing your mind abilities. There’s a lot of techniques for improving

memory, so use the web search to find them.

6. Physical Activity

… Keeping your body in good shape is a critical self-management skill example. When you feel healthy and

have a robust nervous system, you can do more things and cope with many challenges. Physical activity

(like jogging, fitness, different sorts of sports, etc.) allows you to strengthen your body, keep your muscles

up, and be more productive.

Self-set goals: