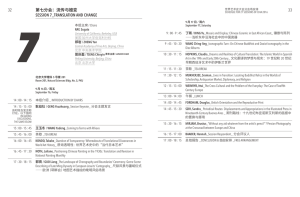

Journal homepage: www.jcimjournal.com/jim www.elsevier.com/locate/issn/20954964 Available also online at www.sciencedirect.com. Copyright © 2017, Journal of Integrative Medicine Editorial Office. E-edition published by Elsevier (Singapore) Pte Ltd. All rights reserved. ● Review A history of standardization in the English translation of traditional Chinese medicine terminology Xiao Ye1,2, Hong-xia Zhang3,4 1. College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou 310053, China 2. Confucius Institute, University of Coimbra, Coimbra 3004-530, Portugal 3. College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou 310053, China 4. Faculty of Education, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200062, China ABSTRACT In order to facilitate and propose further international standardization of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) terminology, this article applies methods of historiography, philology and descriptive study to divide the history of TCM into three phases, based on representative experts and social events; to illustrate different aspects of these experts and their translation principles and standards and to discuss associated factors and inherent problems. The authors find that the development of a terminology standard for TCM has generally progressed from early approaches that were ill-suited to the contemporary needs to culturally and professionally referenced approaches, from uncoordinated research to systematic studies, and from individual works to collaborative endeavors. The present international standards of TCM terminology have been attained through the work of numerous scholars and experts in the history of the field. The authors are optimistic that a more comprehensive and recognized standard will come out soon. Keywords: standardization; terminology; English translation; history; medicine, Chinese traditional Citation: Ye X, Zhang HX. A history of standardization in the English translation of traditional Chinese medicine terminology. J Integr Med. 2017; 15(5): 344–350. 1 Introduction In the last few decades, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has spread quickly in parts of the world that share English as a common language. It has been fully or partly accepted in many Western countries and more countries are considering its regulation and inclusion in the medical care system. However, TCM originates from China and its source language is Chinese and even ancient Chinese. TCM learners can easily find that a single TCM term may have many translations in common use, and the literature—including inappropriately translated ones. This causes confusion in academic study, clinical research, and all forms of communication. In order to solve this problem, linguists and medical experts working around the world, individually, and in groups, have sought to establish a standardized English version of the TCM terminology. This work has pursued for decades and some progress has been made. However, to date, there is no unanimously recognized international standard translation. A general illustration of this history may be helpful to contextualize the mistakes that we have made, the experiences that we have accumulated and the problems that we still must solve. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2095-4964(17)60357-1 Received March 27, 2017; accepted May 8, 2017. Correspondence: Hong-xia Zhang, Associate Prof.; E-mail: evezhanghx@sina.com September 2017, Vol. 15, No. 5 344 Journal of Integrative Medicine www.jcimjournal.com/jim 2 History review 2.1 1960s and 1970s The transfer of Chinese medicine across Western countries has been intermittent for hundreds of years. Some books of Chinese medicine were translated to or written in Western languages during this period, but according to the literature that has been found, it was not until the 1960s that some scholars noticed the lack of standardization in the translation of TCM terminology and tried to establish such a standard by themselves. 2.1.1 Manfred B. Porkert Manfred Porkert, born in 1933 in the Czech Republic, had received his Ph.D. degree in Chinese studies at the Paris Sorbonne in 1957. He is now an emeritus professor of Munich University, Germany. He praised Chinese medicine as a modern and future medicine, a mature science and a genuine life science.[1] He was perhaps the first author to cogently discuss terminology and the need for precision and consistency in the translation of TCM.[2] He endeavored to establish a standardized and practical terminology system of Chinese medicine by solely using Latin words. This was reflected in a number of papers, written in German, which were published between 1961 and 1965,[3] and also in many of his important works, such as The Theoretical Foundations of Chinese Medicine and The Essentials of Chinese Diagnostics, both of which were published in English in 1974. Although his standardized terminology system may be accurate in expressing the meanings, the terms he translated were very difficult to read, recognize, remember and popularize, because the contemporary use of Latin has been greatly different to the situation in the 17th century.[4] As a result, his books and terminology system were very difficult to understand; this difficulty extended to its application in teaching, research and communication, especially for Chinese practitioners. His terminology system was thus not adopted. 2.1.2 Joseph Needham Joseph Needham, born in 1900 in England, was a scientist, historian and sinologist. He was a member of British Royal Society and worked in the University of Cambridge. His greatest contribution to mankind is his study on the science and technology of China, which is mainly recorded in a series of monographs, called the Science and Civilization in China Series, published by Cambridge University Press since 1954. This work includes considerable attention to Chinese medical history. His other great work on Chinese medicine is Celestial Lancets: A History and Rationale of Acupuncture and Moxa, published in 1980. He also perceived the problem of translating TCM terms and discussed strategies toward its resolution. He did not agree with Manfred B. Porkert’s Journal of Integrative Medicine method and said, “He pursed a line rather different from that which we would still prefer to adopt. He has largely gone over direct[ly] to Latin.”[3] Instead, Needham tried to create a vocabulary based on semantic roots that would be well understood by Western readers, and invented many new terms based on Greek and Latin roots. Aside from this main strategy, he used a more flexible approach. For example, he opposed transliteration, but adopted it for some untranslatable terms, such as Tao, Yin, Yang and especially qi, which was previously translated as “energy”. He thought literal translation was inappropriate for expressing the message and prevented readers from understanding, but he used it when the semantic connotation was clear, such as the heart, liver, lung, spleen and kidney for respective terms in Chinese medicine.[5] His strategy of standardization had great impact on some future scholars and continued to be a frequent topic of discussion among experts and translators through the beginning of the 21st century. Though Manfred B. Porkert and Joseph Needham applied different strategies to the standardization of TCM terms, their approaches were largely confined to the use of Latin words or Latin and Greek roots, which was probably influenced by their traditional use in Western science and medicine. However, both of their strategies generated new and difficult words for modern readers. Moreover, over time, the familiarity with classical languages has faded, and fewer people can comfortably read and understand the words generated in these classically inspired translation systems. Although they failed to establish a standardized terminology system, these first efforts provided an invaluable experience and established a need for a standardized English translation of TCM terms. 2.2 1980s and 1990s In 1972, American president Richard Milhous Nixon visited China. During the trip, the use of acupuncture for pain control was reported in the New York Times, arousing a fever for learning TCM across the Western world. At the beginning, many Westerners went to Southeast Asia, China (Hong Kong and Taiwan) and Japan to learn acupuncture. After the Cultural Revolution in China (1966–1976), Westerners started to learn acupuncture directly in mainland China, and could obtain a World Health Organization (WHO) training certificate. With its rapid expansion, and widely ranging primary sources, to have one standard English version of TCM terminology seemed much more urgent and a few standards emerged, and were broadly adopted. In addition, scholars from China began to participate in this effort. 2.2.1 Ou Ming Though many Chinese-English dictionaries of Chinese medicine were published in this period in China, Ou Ming was perhaps the first Chinese author to comprehensively 345 September 2017, Vol. 15, No. 5 www.jcimjournal.com/jim discuss the principles and methods behind establishing a standardized English translation of TCM terms. He was born in 1924 in China and was a lifetime professor of TCM at Guangzhou University. From 1978 to 1986, he and his team compiled two dictionaries, namely ChineseEnglish Glossary of Common Terms in Traditional Chinese Medicine and Chinese-English Dictionary of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Meanwhile, he proposed a combined application of transliteration, free translation and semi-transliteration with semi-free translation for TCM terms. The sphere of their application was illustrated and examples were given.[6] He also discussed the English translation for many common and special terms through a series of papers. His exploration of the English translation of TCM terminology laid a solid foundation for future translation practice and standardization, becoming a source of translation practice of TCM in China. [7] However, his translation principles and methods were at a fundamental stage. His dictionaries did not attract attention from outside China and like other such dictionaries in China at that time, their influence was generally regional. 2.2.2 Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature by WHO With a view to achieving global agreement on a Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature, the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific sponsored four regional meetings in Manila, Tokyo, Hong Kong and Seoul, respectively, from 1982 to 1987. After basic agreement at the regional level, a scientific group tasked with adopting a Standard International Acupuncture Nomenclature was held in Geneva in October–November 1989. [8] With cooperative efforts from experts around the world, two editions of Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature were published, one in 1984 and another in 1993. Under full implementation by WHO, this international acupuncture standard spread widely and most of its standardized terms were adopted across the world. Undoubtedly, it contributed greatly to the transmission and communication of acupuncture in the world. However, this standard is limited to the names of channels and acupoints, which represent a very small fraction of the total TCM terminology. Moreover, the English words already used for some words in established practice were different from the new the standard, and in the years following the adoption of WHO standards, some renowned experts opposed its way of translating acupoints, the main part of the standard. 2.2.3 Xie Zhu-fan Xie Zhu-fan, born in 1924 in China, studied Western medicine at the beginning of his medical education, and Chinese medicine later. He is now the honorary director of the Institute of Combing Chinese and Western September 2017, Vol. 15, No. 5 Medicines in Beijing. In 1980, Xie compiled a ChineseEnglish Dictionary of TCM Vocabulary that was mainly used inside in the Peking University. Later in 1994, he compiled Chinese-English Classified Dictionary of TCM, based on the previous edition, though the English translation for some terms had been changed. A previous director of State Administration of TCM in China wished in the book’s preface that “… the English terms of this dictionary can be further improved through practice and gradually become a well-recognized English standard of TCM terminology.”[9] This implies his terminology system was approved by some government institutes. His most significant feature was his advocacy for the wide use of modern medical terms to translate TCM, as he thought it was more convenient for medical communication. At the same time, he opposed literal translation as he thought TCM terms should not be regarded as a combination of individual Chinese characters. His opinions aroused many debates with Nigel Wiseman in a series of papers. 2.2.4 Nigel Wiseman Nigel Wiseman, born in 1954 in the United Kingdom, is a well-known linguist and speaks many languages, including Spanish, German and Chinese. He holds a doctorate in Complementary Health from the University of Exeter. In 1981, he moved to Taiwan. He has taught English and subjects related to Chinese medicine at China Medical University and Chang Gung University in Taiwan. With respect to English translation of TCM terminology, he compiled a wildly used dictionary entitled A Practical Dictionary of Chinese Medicine, which was first published by Paradigm Publications in 1994 and later the second edition in 1998, as well as two editions in China. His dictionary covers a wide range of Chinese medicine and this terminology system has been adopted as the English standard by two of America’s largest publishers of Chinese medicine, namely Paradigm Publications and Blue Poppy Press. [10] He mainly advocated literal translation, used common language equivalents, opposed applying Western medical terms and Latin words except medicinal names, and coined some new words and terms from common English. Meanwhile, since 1993, he has published a series of papers in journals or on websites, including discussion of the importance of the translated language for Chinese medicine, the translation methodology and theory, the extralinguistic factors of TCM translation and debates with other experts of terminology translation. As the first most comprehensive, systemic and meticulous standardized terminology system, his dictionary and translation theory have attracted great attention and enjoyed wide application around the world, especially in English-speaking countries. However, his 346 Journal of Integrative Medicine www.jcimjournal.com/jim approaches to translation of terminology are disapproved of by some experts and his terminology system is not yet officially recognized as an international standard. 2.2.5 Li Zhao-guo Li Zhao-guo, born in 1961 in China, has a Master’s degree in applied linguistics and earned a Ph.D. in ancient Chinese culture and its translation from Shanghai University of TCM. He is the leading figure of TCM translation in China. Since 1991, he has published more than a hundred papers on the English translation of Chinese medicine in China. He has also published dozens of other works on TCM translation. In 1996, his Skills of English Translation of TCM was published by People’s Medical Publishing House, which is the first systemic theoretical work of TCM translation in China. In this book, he illustrated the translation principles and methods for the TCM terminology. He was influenced by Needham’s translation method and initially advocated new words being coined by Latin or Greek roots at the beginning, though that approach was quickly abandoned. He has published many Chinese-English dictionaries of TCM terminology as well. The earliest one was published by World Publishing Corporation in 1997, in which five principles of English translation of TCM terminology were put forward, namely to be natural, concise, nationally featured, back-translatable and prescriptive. He exerts great influence in the field of TCM translation in China and has played an important role in the establishment of many national and international standards of TCM terminology. The terminology system used in his dictionaries has not garnered much attention from the world outside of China, but it has served as a reference for future international standards. This is a period full of individual ideas and debates. At least twenty English dictionaries of TCM terminology were published by different authors in China, but none of them exerted wide influence within China, let alone internationally. Wiseman’s Dictionary was widely used in many countries, but it was still not recognized as an international standard, and debates over its suitability were voiced in the 21st century. Even the Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature, advocated by WHO, encountered great resistance in its method of translating many terms and acupoints. However, these dictionaries, the WHO acupuncture standard and translation theories paved a way to more mature standards of TCM terminology. 2.3 Proposed standards of the early 2000’s Chinese medicine has become more widely and deeply accepted and applied around the world in the 21st century. In 2002, the WHO published its strategy for traditional medicine, repeatedly citing “TCM” as an example. It also suggested 28 diseases, symptoms or conditions for which acupuncture has been proven—through controlled trials— Journal of Integrative Medicine to be an effective treatment.[11] Hence, more international organizations became interested in setting up a standard for TCM terminology. On the other hand, recognizing the importance of international standards and with powerful national politics, a booming economy and strong culture in China, the Chinese government was eager to join the debate. 2.3.1 English Translation of Common Terms in Traditional Chinese Medicine by State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Initiated in 2000, Xie Zhu-fan and his team undertook a research program on the standardization of English translation of TCM terminology, which was sponsored by the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine in China. Its achievements were first seen in Newly Compiled Chinese-English Classified Dictionary of TCM, published by Foreign Languages Press in 2002, and later in English Translation of Common Terms in Traditional Chinese Medicine, published by the China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine in 2004. The latter was an outcome of analysis and comparison of previous works based on scientific, accurate, practical and acceptable principles. [12] This dictionary was recommended for wide use in China and used as the reference material for international standards afterwards. 2.3.2 Chinese Terms in Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy by China National Committee for Terms in Sciences and Technologies In 2000, the Committee for Terms in TCM, as an offshoot of the China National Committee for Terms in Sciences and Technologies, was established. In the same year, the Committee undertook a research program on the Standardization of Fundamental Terms of TCM sponsored by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. It established many documents and regulations for the standardization of both Chinese and English TCM terms. After tremendous work, the major achievement was Chinese Terms in Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy published by Science Press in 2004. It proposed five translation principles, namely to be equivalent, concise, unanimous, back-translatable and prescriptive. It applied free translation in the first place, literal translation in the second and tried to limit transliteration. This standard was used as reference material for international standards afterwards. 2.3.3 WHO International Standard Terminologies on Traditional Medicine in the Western Pacific Region by WHO in the Western Pacific Region In 2004, recognizing that the main role of standards is for maintaining levels of quality, safety, reliability, efficiency and interchangeability, which are the most needed features in traditional medicine, WHO in the 347 September 2017, Vol. 15, No. 5 www.jcimjournal.com/jim Western Pacific Region (WHO-WPRO) initiated projects promoting the proper use of traditional medicine under the theme of “standardization with evidence-based approaches.” Among the various standards in traditional medicine, such as acupuncture point locations, information and clinical practice, the development of an international standard terminology was regarded as the very first step towards overall standardization of traditional medicine. It convened three meetings for developing international standard terminology on traditional medicine in Beijing, China in October 2004; Tokyo, Japan in June 2005; and Daegu, Republic of Korea in October 2005. These meetings yielded successful outcomes, as shown in the WHO International Standard Terminologies on Traditional Medicine in the Western Pacific Region, published online in 2007.[13] In this standard, the translation principles are accurate reflections of the original concept of Chinese terms, with no creation of new English words, avoidance of Pinyin (Romanized Chinese) and consistency with WHO’s Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature. The terminology standard was intended to be revised every 3 to 5 years. It implied a new step of international cooperation in the standardization of TCM terminology. 2.3.4 International Standard Chinese-English Basic Nomenclature of Chinese Medicine by World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies The World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies (WFCMS) is an international academic organization authorized by the State Council of China. Since its establishment in 2003, it had been devoted to the work of international standardization of Chinese medicine. It studied various materials all around the world and completed a draft in 2006. At the end of 2007, it announced its completion of International Standard Chinese-English Basic Nomenclature of Chinese Medicine, which was formally published in 2008 by the People’s Health Publishing House. This work was mainly sponsored by the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine in China. In the course of compiling this standard, WFCMS tried in many ways to comply with the terminology system proposed by the WHO-WPRO. More than 200 experts from 68 countries and regions took part in its deliberations. It was recommended for use to its 174 member organizations, from 55 countries, and would be revised every five years.[14] The principles governing this standard stipulated that translations were to be equivalent, concise, unanimous and prescriptive. Major publications in China have adopted this standard. In 2013, its second edition was announced, which included definitions for each term both in Chinese and English. Along the course of establishing terminology standards, hundreds of research papers concerning this topic were September 2017, Vol. 15, No. 5 published worldwide, especially in China. The topics cover a wide range from macroscopic to microscopic, such as the terminology translation guidelines, principles, problems and according strategies, reviews, methods, comparisons, comments, living examples, linguistic features and teaching.[15] They enriched the discussion of terminology standardization in TCM, but, as they represent the opinions of many different people applying different perspective and theories, they fail to arrive at consensus. With the participation of the Chinese government and international organizations, the work of standardization of TCM terminology has become more and more organized and cooperative among experts around the world. In 2008, WHO decided to develop the 11th International Classication of Diseases, in which traditional medicine would be included as a chapter. The major discussion in the traditional medicine section is Chinese medicine, and international terminology standards by WHO-WPRO and WFCMS were taken into great consideration.[16] In 2009, International Standardization Organization (ISO) established a new committee for the international standard of Chinese medicine. With regard to the terminology standard, the terminology system by WFCMS had officially been submitted to ISO/TC 249 in 2013.[17] Especially in 2016, the terminology standard of Chinese Materia Medica had been promoted by the ISO/ TC 249 to the stage of draft international standard.[18] 3 Discussion The above history review shows us that the standardization of English translation for TCM terminology is moving toward a more and more unanimous, international and open standard that could be revised about every five years. Its journey has progressed from early approaches that were ill-suited to the contemporary needs to culturally and professionally referenced approaches, from uncoordinated research to systematic studies, and from individual works to collaborative endeavors. We can also see that the successful establishment of such standards is closely related to the gradual acceptance of TCM in the world and the development of China’s international influence. If official organizations had participated earlier and worked together more cooperatively, some debates and repeated work could have been avoided, thus saving human resources, money and time. Though it is possible that a unanimous open standard may be agreed upon in the coming years, there are still some problems we must keep in mind. The first problem is to what extend such standards should be applied. There has been strong opposition to the standardization of TCM terminology by many well-known experts in Chinese medicine. For example, 348 Journal of Integrative Medicine www.jcimjournal.com/jim Benskey argued that any form of standardization betrays the multiple meanings inherent in most Chinese medical terms—a richness that has developed over 2 000 years of use by different scholars in different contexts. The rigid application of the principle of one to one correspondence in translating Chinese terms into English easily oversimplifies Chinese medial ideas. Because of the cultural and linguistic divide between China and the West, completely accurate translation is impossible; a multiplicity of terms creates a “terminological chaos” that actually benefits students as they learn to negotiate the depths of Chinese medical concepts.[19] Giovanni Maciocia believed the most important thing for clinical practitioners was not how to express the language of TCM, but was the clinical experience. The translation of TCM terminology should focus on the interpretation of the connotation in context rather than debates on the translation of literal terms. Different ways of translation could enrich the understanding of Chinese medicine. [20] Hence, even with such standards, we should not apply them blindly in every situation. One appropriate way may be that for publications and scientific research, it is compulsory to use standard translations; for classroom teaching, teachers should use standard terms at the most extend, but can also use alternative translations to enrich discussion with students; and for communication with patients, the use of language that the patient can understand is ideal. The second problem is in its lack of terminology of ancient literature of TCM. The terms included in the above standards would apply to those commonly used in contemporary practice. However, TCM has a history of thousands of years and a large amount of cultural wisdom, experience of disease prevention and treatment. Researches in herbs and formulas are still buried in this ancient literature, only a small proportion of which have been translated to English. The full connotation and expression of TCM terms are always evolving and changing, so a standard of modern TCM terminology is still not sufficient. This is exemplified in the chaos of many English versions of Huang Di Nei Jing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic). From 1925 to 2015, it has been translated, in part or entirely, into at least thirteen English versions, and new versions are still emerging.[21] The translation styles and word selection are all different due to translators’ different educational backgrounds, professions and goals. To this end, Paul U. Unschuld from Germany and Li Zhao-guo from China have done an important job, because they each compiled terminology dictionaries for the Huang Di Nei Jing. In the face of numerous ancient literature of TCM, this could be a small step. We hope that more of such dictionaries or standards can be put forward based on the significance of works or the period of Chinese history in which they were Journal of Integrative Medicine composed, reflecting cultural and linguistic context. The third problem is in its ignorance of a standard for single characters of TCM. Different from English letters, each Chinese character is very special, has its own shape, pronunciation and connotation. Understanding the multimeanings of each character would surely facilitate a better understanding of terms. It is significant in Chinese medicine that each character of its terminology could have very profound meanings. Some scholars once calculated the number and frequency of characters in the standards of WFCMS and WHO-WPRO respectively. They found in the former standard, there were 1 886 different characters used with a total character count of 16 821, among which 48 (2.54%) characters represented one third of the total characters used in the text, just 110 (5.83%) characters comprised one half the total character count and 223 (11.82%) represented two thirds of the total Chinese characters present in the document; in the latter standard, there were altogether 1 218 characters with a total character count of 6 131, among which 23 (1.89%) characters took up one third of the total count, 38 (3.11%) ones took up one half and 106 (8.70%) took up two thirds.[22] This clearly shows some characters occur more frequently in the terminology of Chinese medicine, which could be regarded as the core characters. We can easily find that such characters usually have heavy cultural coating and multiple meanings and can frequently be combined with other characters, which become difficult to translate, and the use of the same English term for each of these combinations would be insufficient. Nigel Wiseman may have made such a mistake when he defined one English term for each of the 638 Chinese characters in his dictionary and used the same English term for each occurrence of the character independent of its accompanying characters.[23] What we need is probably a standard that contains a standard English term for each meaning of a character and phrase examples where that character and meaning are provided. This could be very meaningful for further standards to be made in this field. 4 Conclusions Just as Isaac Newton said, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants,” the present achievement of international standards of TCM terminology is attained by endeavors of numerous scholars and experts across the history of this effort. Though several standards of TCM terminology still co-exist and there are still some inherent problems, we are optimistic that a more comprehensive and recognized standard will come out eventually with the broadening use of TCM around the world, the deeper integration of TCM with the Western medical system and the further participation of international organizations. 349 September 2017, Vol. 15, No. 5 www.jcimjournal.com/jim 5 Funding Sources This study was supported by funding from the Zhejiang Key Program of Humanities and Social Sciences for Colleges and Universities in 2014 (No. 2014QN050). 12 13 6 Conflicts of interest None declared. 14 REFERENCES 1 Fan YN. Transmission of Chinese medicine in the Germany. Shangdong Zhong Yi Yao Da Xue Xue Bao. 2014; 38(5): 459–462. Chinese. 2 Ergil MC. Considerations for the translation of traditional Chinese medicine into English. (2001) [2017-3-22]. http:// www.paradigm-pubs.com/sites/www.paradigm-pubs.com/ files/files/Tanslation.pdf. 3 Needham J, Gwei-Djen L, Porkert M. Problems of translation and modernisation of ancient Chinese technical terms. Ann Sci. 1975, 32(5): 491–502. 4 Niu CY. Thinking and method of traditional Chinese medicine translator in early period. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2003; 1(4): 309–311. Chinese. 5 Li ZG, Li D. Discussion on Needham’s translation thoughts on TCM. Shanghai Ke Ji Fan Yi. 1997; 2: 20–21. Chinese. 6 Ou M, Li YW. On English translation of TCM terminology. Shanghai Ke Ji Fan Yi. 1986; 4:18–22. Chinese. 7 Li ZG. A discussion of English translation of 1995 and 1997 Chinese National Standards of Traditional Chinese Medical Terminologies for Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2010; 8(11): 1090–1096. Chinese. 8 World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature. 2nd ed. (1993) [2017-03-22] http://apps.who.int/iris/ bitstream/10665/207716/1/9290611057_eng.pdf. 9 Xie ZF, Lou ZC, Huang XK. Classified dictionary of traditional Chinese medicine. Beijing: New World Press. 1994. 10 Lan FL. Comments on A practical dictionary of Chinese medicine by Wiseman. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2006; 26(2): 177–180. Chinese. 11 World Health Organization. Acupuncture: review and September 2017, Vol. 15, No. 5 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 350 analysis of reports on controlled clinical trials. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2003. Xie ZF. English translation of common terms in traditional Chinese medicine. Beijing: China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2004. World Health Organization. WHO international standard terminologies on traditional medicine in the Western Pacific Region. (2007) [2017-3-22] http://www.wpro.who.int/ publications/who_istrm_file.pdf?ua=1. Zhong Guo Zhong Yi Yao Bao. International standard Chinese-English basic nomenclature of Chinese medicine being completed. (2008-10-14) [2017-03-22]. http://www. wfcms.org/menuCon/contdetail.jsp?id=2383. Chinese. Du LX, Liu AJ, Chen ZF, Wu Q. The present sitituation and analysis of the translation of TCM terminology from 2000 to 2012. Zhong Yi Jiao Yu. 2015; 34(2): 6–11. Chinese. Li ZG. Issues on international standardization of traditional Chinese medical terminologies: from WHO/ICD-11 to ISO/ TC249. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2010; 8(10): 989–996. Chinese. World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies. WFCMS attends the 4th ISO/TC 249 full council. (2013-05-23) [2017-03-22]. http://www.wfcms.org/department/mainCon. jsp?departid=298&titleid=299&id=4868. China Net of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Decoction service for Chinese herbs will have ISO standard. (201605-05) [2017-03-22]. http://www.wfcms.org/department/ mainCon.jsp?departid=298&titleid=318&id=7011. Hui KK, Pritzker S. Terminology standardization in Chinese medicine: the perspective from UCLA center for East-West medicine. Chin J Inter Med. 2007; 13(1): 64–66. Buck C, Rose K, Felt R, Wiseman W, Maciocia G. On terminology & translation. J Chin Med. 2000; 63(6): 38–52. Ye X, Dong MH. A review on different English versions of an ancient classic of Chinese medicine: Huang Di Nei Jing. J Integr Med. 2017; 15(1): 11–18. Yang MS, SH, Jing Y, Zhu C. TCM terms translation and teaching mode based on single character study. Liaoning Zhong Yi Yao Da Xue Xue Bao. 2013; 15(8): 16–18. Chinese. Xie ZF, Liu GZ, Lu WB, Fang T, Zhang Q, Wang T, Wang K. Comments on Nigel Wiseman’s A Practical Dictionary of Chinese Medicine—on Wiseman’s literal translation. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2005; 25(10): 937– 940. Chinese with abstract in English. Journal of Integrative Medicine